MERS-related coronavirus: Difference between revisions

→Therapeutics: add ref |

→Therapeutics: add ref |

||

| Line 152: | Line 152: | ||

There are no known treatments but future medicines are expected from [[DPP4 inhibitors]] inhibitors which are available |

There are no known treatments but future medicines are expected from [[DPP4 inhibitors]] inhibitors which are available |

||

<ref>{{cite journal|last=Tripp|first=Ralph|title=Therapeutic Considerations for Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus|journal=Journal of Antivirals & Antiretrovirals|date=Aug 27, 2013|volume=5|doi=10.4172/jaa.1000e109|url=http://www.omicsonline.org/therapeutic-considerations-for-middle-east-respiratory-syndrome-coronavirus-jaa.1000e109.pdf|issn=1948-5964}}</ref>. SARS Virus Treatments Could Hold the Key for Treatment of MERS-CoV Outbreak<ref>{{cite web|title=SARS Virus Treatments Could Hold the Key for Treatment of MERS-CoV Outbreak|url=http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2013/09/130913085711.htm|publisher=Science Daily|accessdate=19 November 2013}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last=Momattin|first=Hisham|coauthors=Mohammed, Khurram; Zumla, Alimuddin; Memish, Ziad A.; Al-Tawfiq, Jaffar A.|title=Therapeutic Options for Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) – possible lessons from a systematic review of SARS-CoV therapy|journal=International Journal of Infectious Diseases|year=2013|month=October|volume=17|issue=10|pages=e792–e798|doi=10.1016/j.ijid.2013.07.002}}</ref> |

<ref>{{cite journal|last=Tripp|first=Ralph|title=Therapeutic Considerations for Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus|journal=Journal of Antivirals & Antiretrovirals|date=Aug 27, 2013|volume=5|doi=10.4172/jaa.1000e109|url=http://www.omicsonline.org/therapeutic-considerations-for-middle-east-respiratory-syndrome-coronavirus-jaa.1000e109.pdf|issn=1948-5964}}</ref>. SARS Virus Treatments Could Hold the Key for Treatment of MERS-CoV Outbreak<ref>{{cite web|title=SARS Virus Treatments Could Hold the Key for Treatment of MERS-CoV Outbreak|url=http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2013/09/130913085711.htm|publisher=Science Daily|accessdate=19 November 2013}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last=Momattin|first=Hisham|coauthors=Mohammed, Khurram; Zumla, Alimuddin; Memish, Ziad A.; Al-Tawfiq, Jaffar A.|title=Therapeutic Options for Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) – possible lessons from a systematic review of SARS-CoV therapy|journal=International Journal of Infectious Diseases|year=2013|month=October|volume=17|issue=10|pages=e792–e798|doi=10.1016/j.ijid.2013.07.002}}</ref>. [[IFNβ]] and [[Ribavirin]] combination do affect MERS-coV replication<ref>{{cite journal|last=Coleman|first=Christopher M.|coauthors=Frieman, Matthew B.; Racaniello, Vincent|title=Emergence of the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus|journal=PLoS Pathogens|date=5 September 2013|volume=9|issue=9|pages=e1003595|doi=10.1371/journal.ppat.1003595}}</ref>. |

||

==Prevention== |

==Prevention== |

||

Revision as of 07:50, 19 November 2013

| MERS-CoV | |

|---|---|

| |

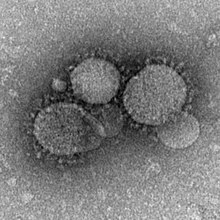

| MERS-CoV particles as seen by negative stain electron microscopy. Virions contain characteristic club-like projections emanating from the viral membrane. | |

| Virus classification | |

| Group: | Group IV ((+)ssRNA)

|

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Subfamily: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | MERS-CoV

|

The Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV)[1], also termed EMC/2012 (HCoV-EMC/2012), is a Betacoronavirus, a novel coronavirus (nCoV) first reported on 24 September 2012 on ProMED-mail[2] by Egyptian virologist Dr. Ali Mohamed Zaki in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. As of 31 October 2013[update], the World Health Organisation confirmed that 149 people have contracted MERS worldwide, of which 63 have died.[3]

Signs and symptoms

Early reports[4] compared the virus to severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), and it has been referred to as Saudi Arabia's SARS-like virus.[5] Symptoms of MERS-CoV infection include renal failure and severe acute pneumonia, which often result in a fatal outcome. The first patient had a "7-day history of fever, cough, expectoration, and shortness of breath."[4] MERS has an estimated incubation period of 12 days.[6]

Virology

The virus MERS-CoV belongs to the genus Betacoronavirus,[7] as does SARS-CoV.[8]

Origin

Dr. Ali Mohamed Zaki isolated and identified a previously unknown coronavirus from the lungs of a 60-year-old male patient with acute pneumonia and acute renal failure.[4][9][10] Dr. Zaki then posted his findings on ProMed-mail.[2][9] MERS-CoV is the sixth new type of coronavirus like SARS (but still distinct from it and from the common-cold coronavirus). Until 23 May 2013, MERS-CoV had frequently been referred to as a SARS-like virus,[11] or simply the novel coronavirus, and colloquially on messageboards as "Saudi SARS" (e.g. The Guardian and Yahoo in the UK, CNN in the U.S., and Toronto and Ottawa media in Canada).

It is not certain whether the infections are the result of a single zoonotic event with subsequent human-to-human transmission, or if the multiple geographic sites of infection represent multiple zoonotic events from a common unknown source. However, a study by Ziad Memish of Riyadh University and colleagues suggests that the virus arose sometime between July 2007 and June 2012, with perhaps as many as 7 separate zoonotic transmissions. Among animal reservoirs, CoV has a large genetic diversity yet the samples from patients suggest a similar genome, and therefore common source, though the data are limited. It has been determined through molecular clock analysis, that viruses from the EMC/2012 and England/Qatar/2012 date to early 2011 suggesting that these cases are descended from a single zoonotic event. It would appear the MERS-CoV has been circulating in the human population for greater than one year without detection and suggests independent transmission from an unknown source.[12][13]

Tropism

In humans, the virus has a strong tropism for nonciliated bronchial epithelial cells, and it has been shown to effectively evade innate immune responses and antagonize interferon (IFN) production in these cells. This tropism is unique in that most respiratory viruses target ciliated cells.[14][15]

Due to the clinical similarity between MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV, it was proposed that they may use the same cellular receptor; the exopeptidase, angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2).[16] However, it was later discovered that neutralization of ACE2 by recombinant antibodies does not prevent MERS-CoV infection.[17] Further research identified dipeptyl peptidase 4 (DPP4; also known as CD26) as a functional cellular receptor for MERS-CoV.[15] Unlike other known coronavirus receptors, the enzymatic activity of DPP4 is not required for infection. As would be expected, the amino acid sequence of DPP4 is highly conserved across species and is expressed in the human bronchial epithelium and kidneys.[15][18]

Transmission

On 13 February 2013, WHO stated "the risk of sustained person-to-person transmission appears to be very low."[19] The cells MERS-CoV infects in the lungs only account for 20% of respiratory epithelial cells, so a large number of virions are likely needed to be inhaled to cause infection.[18]

There are four groupings of the coronaviruses: alpha, beta, gamma and delta. Bat coronaviruses are the gene pool for Group 1 or Alphacoronaviruses and Group 2 or Betacoronaviruses. Avian coronaviruses are the gene pool for Group 3 or Gammacoronaviruses and Deltacoronaviruses. To date, no known routine contact exists between humans and bats. There is speculation that an intermediate host is responsible for the sudden appearance of the virus in the human population.[20][21] The European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC), an independent agency of the European Union (EU)[22] established in 2005 to strengthen Europe's defence against infectious diseases, is monitoring MERS-CoV.[23]

As of 29 May 2013[update], the World Health Organization is now warning that the MERS-CoV virus is a "threat to entire world."[24] However, Dr. Anthony Fauci of the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland stated that as of now MERS-CoV "does not spread in a sustained person to person way at all." Dr. Fauci stated that there is potential danger in that it is possible for the virus to mutate into a strain that does transmit from person to person.[25]

Natural reservoir

In September 2012, Ron Fouchier speculated that the virus might have an animal origin originating in bats.[26][27] Sequencing and subsequent analysis indicated that the novel coronavirus shared high sequence homology with both bat[28] and porcine coronaviruses, the highest of which were bat coronaviruses HKU4 and HKU5 (about 94% similarity; carried by the genus Pipistrellus).[7][29] An article published in the Emerging Infectious Disease Journal in March 2013 identified bat coronaviruses carried by the genus Pipistrellus that differed from MERS-CoV by as little as 1.8%. There are several species of Pipistrellus in the Arabian Peninsula. The high potential for use of cave-derived water and bat guano strongly suggests that they may be the pre-crossover zoonotic reservoir. A zoonosis is an infectious disease that is transmitted between species. In the same study it was shown that MERS-CoV was capable of infecting bat and porcine cell lines in addition to human cells. This property would indicate a low barrier for transmission between hosts.[17][29][30]

On 22 July 2013, the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) announced that "currently there is no strong evidence to suggest that camels are a source of infection for human cases of MERS." [31] Several victims have been known to have had contact with camels, including visibly ill camels, however.[32]

On 9 August 2013, a report in the Lancet showed that 50 of 50 (100%) blood serum from Omani camels and 15 of 105 (14%) from Spanish camels had protein-specific antibodies against MERS-CoV spike. Blood serum from European sheep, goats, cattle, and other camelids had no such antibodies.[33] Countries like Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates produce and consume large amounts of camel meat and there's a possibility that African or Australian bats harbor the virus which then camels carried to the Middle East.[34]

As of 31 October 2013[update], there is no agreement on which amimal is the reservoir.[3]

Taxonomy

MERS-CoV is more closely related to the bat coronaviruses HKU4 and HKU5 (lineage 2C) than it is to SARS-CoV (lineage 2B) (2, 9), sharing more than 90% sequence identity with their closest relationships, bat coronaviruses HKU4 and HKU5 and therefore considered to belong to the same species by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV).

- Mnemonic:

- Taxon identifier:

- Scientific name: Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus[1]

- Common name: MERS-CoV

- Synonym: Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus

- Other names:

- novel coronavirus (nCoV)

- London1_novel CoV 2012[35]

- Human Coronavirus-Erasmus Medical Center (HCoV-EMC)

- Rank:

- Lineage:

- › Viruses

- › ssRNA viruses

- › Group: IV; positive-sense, single-stranded RNA viruses

- › Order: Nidovirales

- › Family: Coronaviridae

- › Subfamily: Coronavirinae

- › Genus: Betacoronavirus[7]

- › Species: Betacoronavirus 1 (commonly called Human coronavirus OC43), Human coronavirus HKU1, Murine coronavirus, Pipistrellus bat coronavirus HKU5, Rousettus bat coronavirus HKU9, Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus, Tylonycteris bat coronavirus HKU4, MERS-CoV

- › Genus: Betacoronavirus[7]

- › Subfamily: Coronavirinae

- › Family: Coronaviridae

- › Order: Nidovirales

- › Group: IV; positive-sense, single-stranded RNA viruses

- › ssRNA viruses

Strains:

- Isolate:

- Isolate:

- NCBI

Diagnosis

Several highly sensitive, confirmatory real-time RT-PCR assays exist for rapid identification of MERS-CoV from patient-derived samples (such as bronchoalveolar lavage or sputum): upE (targets elements upstream of the E gene) and 1A (targets the ORF1a gene). In addition, hemi-nested sequencing amplicons targeting RdRp (present in all coronaviruses) and N gene (specific to MERS-CoV) fragments can be generated for confirmation via sequencing. Reports of potential polymorphisms in the N gene between isolates highlight the necessity for sequence-based characterization. Protocols for biologically safe immunofluorescence assays (IFA) have also been developed; however, antibodies against betacoronaviruses are known to cross-react within the genus. This effectively limits their use to confirmatory applications.[37] Although MERS-CoV has been shown to antagonize endogenous IFN production, treatment with exogenous types I and IIIIFN (IFN-α and IFN-λ, respectively) have effectively reduced viral replication in vitro.[14][38]

Therapeutics

There are no known treatments but future medicines are expected from DPP4 inhibitors inhibitors which are available [39]. SARS Virus Treatments Could Hold the Key for Treatment of MERS-CoV Outbreak[40][41]. IFNβ and Ribavirin combination do affect MERS-coV replication[42].

Prevention

It is believed that the existing SARS research may provide a useful template for developing vaccines and therapeutics against a MERS-CoV infection.[43][44] Vaccine candidates based on the spike protein have been created by Novavax and Greffex, Inc, and are currently awaiting clinical trials.[45][46] For now, annual influenza vaccinations and 5-year pneumococcal vaccinations are given to reduce or weaken the severity of MERS-CoV infection.

Epidemiology

| MERS cases and deaths, April 2012 – present | ||||

| Country or Region | Cases | Deaths | Fatality (%) | |

| Oman[3] | 1 | 0 | 0% | |

| France | 2 | 1 | 50% | |

| Italy | 1 | 0 | 0% | |

| Jordan | 2 | 2 | 100% | |

| Qatar | 5 | 3 | 60% | |

| Saudi Arabia | 114 | 47 | 41% | |

| Spain[47] | 1 | 0 | 0% | |

| Tunisia | 3 | 1 | 33% | |

| UAE | 6 | 2 | 33% | |

| UK | 3 | 2 | 67% | |

| Total | 136 | 58 | 43% | |

| Source: CDC[48] | ||||

On 21 February 2013, WHO stated that there had been 13 laboratory-confirmed cases, 6 cases (4 fatal) from Saudi Arabia, 2 cases (both fatal) from Jordan, 2 cases from Qatar, and 3 from the UK.[49] Most infections with human coronaviruses are mild and associated with common colds. Some animal and human coronaviruses, like MERS-CoV, may cause severe and sometimes fatal infections in humans. MERS-CoV does not have many of the grave characteristics of SARS-CoV (severe acute respiratory syndrome) which caused fatal epidemics in southern China, Hong Kong and Canada in 2002 and 2003.[4][50] Fortunately, global surveillance of potential epidemics and preparation has improved since and because of the SARS epidemic.[51][notes 1] In November 2012, Dr. Zaki sent a virus sample to confirm his findings to EMC virologist Ron Fouchier, a leading coronavirus researcher at the Erasmus Medical Center in Rotterdam.[52] The second laboratory-proven case was in London confirmed by the UK Health Protection Agency (HPA).[28][53] The HPA named the virus the London1_novel CoV 2012.[35] On 8 November 2012 in an article published in the New England Journal of Medicine, Dr. Zaki and co-authors from the Erasmus Medical Center, published more details, including a scientific name, Human Coronavirus-Erasmus Medical Center (HCoV-EMC) which was then used in scientific literature.[4] In the article, they noted four respiratory human coronaviruses (HCoV) known to be endemic: 229E, OC43, NL63, and HKU1.[4] In May 2013, the Coronavirus Study Group of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses adopted the official designation, the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV),[1] which was adopted by the World Health Organization to "provide uniformity and facilitate communication about the disease"[54] to replace the unscientific designations Novel coronavirus 2012 or simply 'novel coronavirus' which were consistently used by WHO since 2012.[55]

10 of the 22 people who died and 22 of 44 cases reported were in Saudi Arabia and over 80% were male.[56] This gender disparity is thought to be because most women in Saudi Arabia wear veils that cover the mouth and nose, decreasing their chances of being exposed to the virus.[57] As of 19 June 2013, MERS has infected at least 60 people with cases reported in Jordan, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Tunisia, Germany, the United Kingdom (UK), France and Italy.[58] The death toll had risen to 38.[57] Saudi officials have expressed great concern that when the Hajj, or pilgrimage to Mecca, occurs this Autumn, millions of Muslims from around the world may potentially be exposed to the virus from being in crowded streets around the Kaaba.[59]

Jordan

In April 2012, six hospital workers were diagnosed with acute respiratory failure of unknown origin. Of the six, two died. All the cases were reported to the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). After Dr. Zaki isolated the nCoV strain, a trace back was done. Epidemiologists discovered the Jordan cases. Using stored laboratory samples for all six, it was found that samples from the two patients who had died tested positive for nCoV.[6][60]

Oman

On 31 October 2013, the WHO confirmed that one person in Oman has MERS.[3] The WHO said "the patient in Oman is a 68-year-old man from Al Dahkliya region who became ill" on October 26, 2013.[3]

Saudi Arabia

The first known case of a previously unknown coronavirus, was identified in a 60-year-old Saudi Arabian man with acute pneumonia who died of renal failure in June 2012.[4][5][61] As of 12 May 2013, two more deaths have been reported in the al-Ahsa region of Saudi Arabia. In the latest cluster of infections, 15 cases had been confirmed, and nine of those patients had died.[62] Ten of the 22 people who died and 22 of 44 cases reported were in Saudi Arabia.[56] An unconfirmed case in another Saudi citizen, for which no clinical information was available, was also reported around this time. On 22 September 2012, the Saudi Ministry of Health (MOH) announced that the two cases involving Saudi citizens, caused by what they termed a “rare pattern of coronavirus,” had both proven fatal.

Two of the Saudi Arabia cases were from the same family and from that family at least one additional person presented similar symptoms but tested negative for the novel coronavirus.[63]

In March 2013, the Saudi Arabia Ministry of Health reported the death of a 39-year-old man, the 15th case and 9th death reported to WHO.[26] On 2 May 2013, the Saudi Ministry of Health announced five people died and two other people were in critical condition with confirmed cases of a SARS-like virus.[64] The delays in obtaining data and absence of basic information (which would usefully include: sex, age, other medical conditions and smoking status) have been noted and decried by Dr. Margaret Chan and in Pro-Med comments on numerous briefings. At the annual meeting of the world’s health ministers, Dr. Chan, director-general of the World Health Organization, said the virus was now her “greatest concern.”[65]

On 28 May 2013, the Saudi Ministry of Health reported five more cases of MERS-CoV. The cases have been "recorded among citizens in the Eastern Region, ranging in age from 73 to 85 years, but they have all chronic diseases." With this announcement, the unofficial global case count reached 49 while the death toll stands at 24 according to the CDC.[66] As of 26 June, 34 deaths have been recorded in the kingdom.[59]

On 1 August 2013, the World Health Organization announced three new MERS-CoV cases in that Saudi Arabia, all of them in women, two of whom were healthcare workers. "With the three new cases, Saudi Arabia's posted MERS tally increases to 74 cases with 39 deaths. The cases raise the WHO's MERS count to 94 cases and 46 deaths."[67]

On 31 October 2013, the WHO announced that three paitents in Saudia Arabia died of MERS.[3] The patients were one woman and two men and "all had underlying medical conditions but all reported having had no contact with animals before falling ill".[3]

Hajj

Due to fears of the MERS virus, attendance in the hajj is lower than last year.[68][69]the Saudi government asked "elderly and chronically ill Muslims to avoid the hajj this year" and have restricted the number of people allowed “to perform the pilgrimage”.[70][71][72] Saudi Health Minister Abdullah Al-Rabia said "that authorities had so far detected no cases among the pilgrims" of MERS.[68] However, the Spainish government, in November 2013, reported a woman in Spain, who had recently travelled to Saudi Arabia, for the Islamic pilgrimage, Hajj, contracted the disease and investigators from the World Health Organization are investigating.[47]

United Kingdom

In February 2013, the first UK case of the novel coronavirus was confirmed in Manchester in an elderly man who had recently visited the Middle East and Pakistan; it was the 10th case globally.[73] The man's son whom he visited in hospital in Birmingham was immuno-suppressed because of a brain tumour contracted the virus, providing the first clear evidence for person-to-person transmission.[19][74] He died on 19 February 2013.[75][76]

The second patient was a 49 year old Qatari man who had visited Saudi Arabia before falling ill and being flown privately by air ambulance from Doha to London on 11 September where he was admitted to St Mary's Hospital and later being transferred to St Thomas's Hospital.[77] As a result of Dr Zaki's post on Pro-MED the novel coronavirus was quickly identified.[78][79] He was treated for respiratory disease and, like the first patient in Saudi Arabia, died of renal failure in October 2012. In early October 2012, the Qatari patient residing in the United Kingdom died as well.[9][7][78][79][80]

A further patient who had been in Guys and St Thomas hospital in the UK since September 2012 after visiting the Middle East died on the 28th June 2013. "Guys and St Thomas can confirm that the patient with severe respiratory illness due to novel coronavirus (MERS-COV) sadly died on Friday 28th June, after his condition deteriorated despite every effort and full supportive treatment" Spokesman of Guys and St Thomas.[81]

France

On 7 May 2013, one case was confirmed in Nord departement of France, the man had previously travelled to Dubai, United Arab Emirates.[82] On 12 May 2013, a case of contamination from human to human, a man previously hospitalized in the same room as the first patient, was confirmed by French Ministry of Social Affairs and Health.[83]

France reported its first death from the MERS near the end of May.[84] On 28 May 2013, a report by the Associated Press said a French patient died of the novel coronavirus related to SARS.[85] Fifty percent of those infected have died.[85]

Tunisia

On 20 May 2013, the novel coronavirus reached Tunisia killing one man and infecting two of his relatives. Tunisia is the eighth country to be affected by MERS-CoV, along with Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, the United Kingdom, France, Germany, and the United Arab Emirates.[86]

Italy

On 31 May 2013, the Italian health ministry announced its first case of MERS-CoV in a 45 year-old man who had traveled to Jordan. The patient is being currently treated in a hospital in Tuscany and his condition was reported as not life threatening.[87][88]

Spain

On 1 November 2013, a women who had recently travelled to Saudi Arabia, for the Islamic pilgrimage, Hajj, contracted the disease. She is stated to be in stable condition and investigators from the World Health Organization, are investigating who she came in contact with.[47]

History

Collaborative efforts were used in the identification of MERS-CoV.[28] Dr. Zaki isolated and identified a previously unknown coronavirus from the lungs of a 60-year-old Saudi Arabian man with pneumonia and acute renal failure.[4][9]

He used a broad-spectrum "pan-coronavirus" RT-PCR method and got a positive result. On 15 September 2012, Dr. Zaki's findings were posted on ProMed-mail,[2] the Program for Monitoring Emerging Diseases, a public health on-line forum.[9][11]

The UK Health Protection Agency (HPA) confirmed the diagnosis of severe respiratory illness associated with a new type of coronavirus in a second patient, a 49-year-old Qatari man who had recently been flown into the UK. He died from an acute, serious respiratory illness in a London hospital.[28][53] In September 2012, the United Kingdom's Health Protection Agency (HPA) named it the London1_novel CoV 2012 and produced the virus' preliminary phylogenetic tree, the genetic sequence of the virus[35] based on the virus's RNA obtained from the Qatari case.[5][89] On 25 September 2012, the World Health Organization (WHO) announced that it is "engaged in further characterizing the novel coronavirus" and that it has "immediately alerted all its Member States about the virus and has been leading the coordination and providing guidance to health authorities and technical health agencies."[90] The Erasmus Medical Center in Rotterdam "tested, sequenced and identified" a sample provided to EMC virologist Ron Fouchier by Ali Mohamed Zaki in November 2012.[52]

In September 2012 Ron Fouchier speculated that the virus might have originated in bats.[36] On 8 November 2012 in an article published in the New England Journal of Medicine, Dr. Zaki and co-authors from the Erasmus Medical Center, published more details, including a tentative name, Human Coronavirus-Erasmus Medical Center (HCoV-EMC), the virus’s genetic makeup, and closest relatives (including SARs).[4]

In May 2013, the Coronavirus Study Group of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses adopted the official designation, the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV),[1] which was adopted by the World Health Organization to "provide uniformity and facilitate communication about the disease."[91] Prior to the designation, WHO had used the non-specific designation 'Novel coronavirus 2012' or simply 'the novel coronavirus'.[55]

Fouchier and his team of researchers successfully sequenced the whole genome of the new coronavirus naming the viral strain Human Coronavirus-Erasmus Medical Center (hCoV-EMC) after their research center. They published its genomic sequence in the GenBank (accession code: JX869059) in the fall of 2012.[28]

Saudi officials had not given permission to Dr. Zaki to send a sample of the virus to Fouchier and they were angered when Fouchier claimed the patent on the full genetic sequence[92] of the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus.[92]

The editor of The Economist observed, "Concern over security must not slow urgent work. Studying a deadly virus is risky. Not studying it is riskier."[92] Dr. Zaki was fired from his job as a result of sharing his findings.[93][94][95][96]

Real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) was used to test for distinguishing features of a number of known coronaviruses (such as OC43, 229R, NL63, and SARS-CoV), as well as for RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp), a gene conserved in all coronaviruses known to infect humans. While the screens for known coronaviruses were all negative, the RdRp screen was positive.[28]

At their annual meeting of the World Health Assembly in May 2013, WHO chief Margaret Chan declared that intellectual property, or patents on strains of new virus, should not impede nations from protecting their citizens by limiting scientific investigations. Deputy Health Minister Ziad Memish raised concerns that scientists who held the patent for the MERS-CoV virus would not allow other scientists to use patented material and were therefore delaying the development of diagnostic tests.[56] Erasmus MC responded that the patent application did not restrict public health research into MERS coronavirus,[97] and that the virus and diagnostic tests were shipped—free of charge—to all that requested such reagents.

See also

Notes

- ^ As noted in the article published in The Economist on 20 April 2013, ProMED is an online reporting programme at the International Society for Infectious Diseases are part of improved surveillance systems that "use a range of sources to provide quick information on emerging threats" that were not available at the time of SARS outbreak (in 2003), H5N1 bird flu (in 2005) and H1N1 swine flu (in 2009).

References

- ^ a b c d De Groot RJ; et al. (15 May 2013). "Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV): Announcement of the Coronavirus Study Group". Journal of Virology. doi:10.1128/JVI.01244-13.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ a b c "See Also". ProMED-mail. 2012-09-20. Retrieved 2013-05-31.

- ^ a b c d e f g Kate Kelland (31 October 2013). "WHO confirms four more cases of Middle East virus". Reuters. Retrieved 31 October 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Ali Mohamed Zaki; Sander van Boheemen; Theo M. Bestebroer; Albert D.M.E. Osterhaus; Ron A.M. Fouchier (8 November 2012). "Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia" (PDF). New England Journal of Medicine. 367: 1814. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1211721. Cite error: The named reference "zaki8nov2012" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b c Doucleef, Michaeleen (26 September 2012). "Scientists Go Deep On Genes Of SARS-Like Virus". Associated Press. Retrieved 27 September 2012.

- ^ a b Guery, B.; Poissy, J.; El Mansouf, L.; Séjourné, C.; Ettahar, N.; Lemaire, X.; Vuotto, F.; Goffard, A.; Behillil, S.; Enouf, V.; Caro, V.; Mailles, A.; Che, D.; Manuguerra, J. C.; Mathieu, D.; Fontanet, A.; van der Werf, S. (2013). "Clinical features and viral diagnosis of two cases of infection with Middle East Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus: a report of nosocomial transmission". Lancet. Elsevier Ltd: S0140-6736(13)60982–4. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60982-4. PMID 23727167.

- ^ a b c d e f Bermingham, A.; Chand, MA.; Brown, CS.; Aarons, E.; Tong, C.; Langrish, C.; Hoschler, K.; Brown, K.; Galiano, M. (27 September 2012). "Severe respiratory illness caused by a novel coronavirus, in a patient transferred to the United Kingdom from the Middle East, September 2012" (PDF). Euro Surveillance. 17 (40): 20290. PMID 23078800.

- ^ Cell Host Response to Infection with Novel Human Coronavirus EMC Predicts Potential Antivirals and Important Differences with SARS Coronavirus (Report). American Society for Microbiology.

- ^ a b c d e Falco, Miriam (24 September 2012). "New SARS-like virus poses medical mystery". CNN. Retrieved 27 September 2012.

- ^ Dziadosz, Alexander (13 May 2013). "The doctor who discovered a new SARS-like virus says it will probably trigger an epidemic at some point, but not necessarily in its current form". Reuters. Retrieved 25 May 2013.

- ^ a b Saey, Tina Hesman (27 February 2013). "Scientists race to understand deadly new virus: SARS-like infection causes severe illness, but may not spread quickly". Science News. Vol. 183, no. 6. p. 5.

- ^ "Full-Genome Deep Sequencing and Phylogenetic Analysis of Novel Human Betacoronavirus - Vol. 19 No. 5 - May 2013 - CDC". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2013-05-19. Retrieved 2013-06-01.

- ^ Lau SK, Lee P, Tsang AK, Yip CC, Tse H, Lee RA, Molecular epidemiology of human coronavirus OC43 reveals evolution of different genotypes over time and recent emergence of a novel genotype due to natural recombination. J Virol. 2011;85:11325–37. DOIExtract

- ^ a b Kindler, E.; Jónsdóttir, H. R.; Muth, D.; Hamming, O. J.; Hartmann, R.; Rodriguez, R.; Geffers, R.; Fouchier, R. A.; Drosten, C. (2013). "Efficient Replication of the Novel Human Betacoronavirus EMC on Primary Human Epithelium Highlights Its Zoonotic Potential". MBio. 4 (1): e00611–12. doi:10.1128/mBio.00611-12. PMC 3573664. PMID 23422412.

- ^ a b c Raj, V. S.; Mou, H.; Smits, S. L.; Dekkers, D. H.; Müller, M. A.; Dijkman, R.; Muth, D.; Demmers, J. A.; Zaki, A. (2013). "Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 is a functional receptor for the emerging human coronavirus-EMC". Nature. 495 (7440): 251–4. doi:10.1038/nature12005. PMID 23486063.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Jia, HP; Look, DC; Shi, L; Hickey; Pewe, L; Netland, J; Farzan, M; Wohlford-Lenane, C; Perlman, S (2005-12-xx). "ACE2 Receptor Expression and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Infection Depend on Differentiation of Human Airway Epithelia". Journal of Virology. 79 (23). ncbi.nlm.nih.gov: 14614–14621. doi:10.1128/JVI.79.23.14614-14621.2005. PMC 1287568. PMID 16282461.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|irst4=ignored (help) - ^ a b Müller, MA.; Raj, VS.; Muth, D.; Meyer, B.; Kallies, S.; Smits, SL.; Wollny, R.; Bestebroer, TM.; Specht, S. (11 December 2012). "Human coronavirus EMC does not require the SARS-coronavirus receptor and maintains broad replicative capability in mammalian cell lines". MBio. 3 (6): e00515–12. doi:10.1128/mBio.00515-12. PMC 3520110. PMID 23232719.

- ^ a b "Receptor for new coronavirus found". nature.com. 2013-03-13. Retrieved 2013-03-18.

- ^ a b WHO: Novel coronavirus infection – update (13 February 2013) (accessed 13 February 2013)

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1128/JVI.01244-13, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1128/JVI.01244-13instead. - ^ "Coronavirus Diversity, Phylogeny and Interspecies Jumping". Ebm.sagepub.com. 2008-06-26. Retrieved 2013-06-01.

- ^ "ECDC mission statement". Ecdc.europa.eu. Retrieved 2013-05-31.

- ^ "Rapid Risk Assessment: Severe respiratory disease associated with a novel coronavirus" (PDF). European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. 19 February 2013.

- ^ "WHO calls Middle Eastern virus, MERS, 'threat to the entire world' as death toll rises to 27". Daily Mail. 29 May 2013. Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- ^ "Fauci: New Virus Not Yet a 'threat to the world' (video)". Washington Times. 2012-08-31. Retrieved 2013-05-31.

- ^ a b c Abedine, Saad (13 March 2013). "Death toll from new SARS-like virus climbs to 9". CNN. Retrieved 2013-03-13.

- ^ Doucleff, Michaeleen (28 September 2012). "Holy Bat Virus! Genome Hints At Origin Of SARS-Like Virus". NPR. Retrieved 29 September 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f Lu, Guangwen; Liu, Di (2012). "SARS-like virus in the Middle East: A truly bat-related coronavirus causing human diseases" (PDF). Protein & Cell. 3 (11): 803. doi:10.1007/s13238-012-2811-1.

- ^ a b c "New Coronavirus Has Many Potential Hosts, Could Pass from Animals to Humans Repeatedly". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 13 December 2012.

- ^ a b Augustina Annan; Heather J. Baldwin; Victor Max Corman (March 2013). "Human Betacoronavirus 2c EMC/2012–related Viruses in Bats, Ghana and Europe". Emerging Infectious Disease journal - CDC. 19 (3). Retrieved 20 March 2013.

- ^ Roos, R. (22 July 2013). "OIE downplays camels as possible MERS-CoV source". CIDRAP News. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- ^ Donald G. McNeil Jr (September 11, 2013)Camels Linked to Spread of Fatal Virus The New York Times

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70164-6, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70164-6instead. - ^ "Camels May Transmit New Middle Eastern Virus". 8 August 2013. Retrieved 8 August 2013.

- ^ a b c Roos, Robert (25 September 2013). UK agency picks name for new coronavirus isolate (Report). University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN: Center for Infectious Disease Research & Policy (CIDRAP). Cite error: The named reference "UKHPA" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b Doucleff, Michaeleen (28 September 2012). "Holy Bat Virus! Genome Hints At Origin Of SARS-Like Virus". NPR. Retrieved 29 September 2012.

- ^ Corman, V. M.; Müller, M. A.; Costabel, U.; Timm, J.; Binger, T.; Meyer, B.; Kreher, P.; Lattwein, E.; Eschbach-Bludau, M. (2012). "Assays for laboratory confirmation of novel human coronavirus (hCoV-EMC) infections". Eurosurveillance. 17 (49): 20334. PMID 23231891.

- ^ "Novel coronavirus well-adapted to humans, susceptible to immunotherapy". eurekalert.org. 2013-02-19. Retrieved 2013-02-19.

- ^ Tripp, Ralph (Aug 27, 2013). "Therapeutic Considerations for Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus" (PDF). Journal of Antivirals & Antiretrovirals. 5. doi:10.4172/jaa.1000e109. ISSN 1948-5964.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "SARS Virus Treatments Could Hold the Key for Treatment of MERS-CoV Outbreak". Science Daily. Retrieved 19 November 2013.

- ^ Momattin, Hisham (2013). "Therapeutic Options for Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) – possible lessons from a systematic review of SARS-CoV therapy". International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 17 (10): e792–e798. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2013.07.002.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Coleman, Christopher M. (5 September 2013). "Emergence of the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus". PLoS Pathogens. 9 (9): e1003595. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1003595.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "Development of SARS Vaccines and Therapeutics Is Still Needed". medscape.com. 2013. Retrieved 2013-05-29.

- ^ Butler D. SARS veterans tackle coronavirus. Nature490(7418),20 (2012).

- ^ Parrish, R. (7 June 2013). "Novavax creates MERS-CoV vaccine candidate". Vaccine News. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

- ^ Price, J. R. (26 June 2013). "Greffex Does It Again". Business Wire. Retrieved 27 June 2013.

- ^ a b c Branswell, Helen (7 November 2013). "Spain reports its first MERS case; woman travelled to Saudi Arabia for Hajj". Vancouver Sun. Retrieved 12 November 2013.

- ^ "MERS Frequently Asked Questions and Answers". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Retrieved 22 September 2013.

- ^ Wappes, J. (21 February 2013). "WHO confirms 13th novel coronavirus case". CIDRAP. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ Saey, Tina Hesman (27 February 2013). "Scientists race to understand deadly new virus: SARS-like infection causes severe illness, but may not spread quickly". Vol. 183, no. 6. Science News. p. 5.

- ^ "An ounce of prevention: As new viruses emerge in China and the Middle East, the world is poorly prepared for a global pandemic". Bangkok and New York: The Economist. 20 April 2013.

- ^ a b Heilprin, John (23 May 2013). The Associated Press (AP) (ed.). "WHO: Probe into deadly coronavirus delayed by sample dispute". Geneva: CTV. Cite error: The named reference "sampledisputeCTV23May2013" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b Acute respiratory illness associated with a new virus identified in the UK (Report). Health Protection Agency (HPA). 23 September 2012. Cite error: The named reference "UK23sept2012" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Novel coronavirus infection - update (Middle East respiratory syndrome- coronavirus) (Report). World Health Organization. May 2013.

- ^ a b Global Alert and Response (GAR): Novel coronavirus infection - update (Report). WHO. 23 November 2012.

- ^ a b Khazan, O. (21 June 2013). "Face Veils and the Saudi Arabian Plague". The Atlantic. Retrieved 25 June 2013.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1306742, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1056/NEJMoa1306742instead. - ^ a b Garrett, L.; Builder, M. (28 June 2013). "The Middle East Plague Goes Global". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 29 June 2013.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC).http://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications/Publications/20121207-Novel-coronavirus-rapid-risk-assessment.pdf

- ^ Sander van Boheemena; Miranda de Graafa; Chris Lauberb; Theo M. Bestebroera; V. Stalin Raja; Ali Moh Zakic; Albert D. M. E. Osterhausa; Bart L. Haagmansa; Alexander E. Gorbalenyabd; Eric J. Snijderb; Ron A. M. Fouchiera (20 November 2012). "Genomic Characterization of a Newly Discovered Coronavirus Associated with Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome in Humans". American Society for Microbiology.

- ^ McDowall, Angus (Sun May 12, 2013 8:44am EDT). "Two more people die of novel coronavirus in Saudi Arabia". Reuters. Retrieved 12 May 2013.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Novel coronavirus infection - update World Health Organization 23 November 2012

- ^ "Saudia Arabia: 7 Cases of SARS-like Virus Seen". Associated Press. 3 May 2013. p. 4.

- ^ New Tools to Hunt New Viruses May 27, 2013 NYT

- ^ Roos, Robert (May 28, 2013). "Saudi Arabia reports 5 more MERS-CoV cases". CIDRAP News.

- ^ Roos, Robert (August 1, 2013). "Saudi Arabia announces three new MERS cases". CIDRAP News.

- ^ a b "Two million Muslim pilgrims begin annual hajj". AFP. 13 October 2013. Retrieved 17 October 2013.

- ^ "Muslim pilgrims urged to heal rifts at hajj zenith". AFP. 14 October 2013. Retrieved 17 October 2013.

- ^ "MERS virus claims three more lives in Saudi Arabia". AFP via Yahoo. September 7, 2013 8:42 PM. Retrieved 8 September 2013.

Authorities have urged the elderly and chronically ill Muslims to avoid the hajj this year and have cut back on the numbers of people they will allow to perform the pilgrimage.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Katz , Andrew (16 October 2013). "As the Hajj Unfolds in Saudi Arabia, A Deep Look Inside the Battle Against MERS". Time Magazine. Retrieved 17 October 2013.

- ^ Edwards, Anna (PUBLISHED:07:46 EST, 11 October 2013; UPDATED:09:02 EST, 11 October 2013). "Hajj pilgrimage could cause deadly Mers virus outbreak as millions gather for Islamic event where camels are slaughtered… a possible cause of the disease". Mail newspaper. Retrieved 17 October 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ WHO: Novel coronavirus infection –update (11 February 2013) (accessed 13 February 2013)

- ^ James Gallagher (13 February 2013). "Coronavirus: Signs the new Sars-like virus can spread between people". BBC News. Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- ^ Kelland, Kate (19 February 2013). "Britain dies after contracting new SARS-like virus". Reuters. Retrieved 19 February 2013.

- ^ Hodgekiss, Anna (19 February 2013). "Sars-like virus claims first UK victim after man, 39, dies at a Birmingham hospital". The Daily Mail. Retrieved 19 February 2013.

- ^ http://www.promedmail.org/direct.php?id=20120923.1305982

- ^ a b Nebehay, Stephanie (26 September 2012). "WHO issues guidance on new virus, gears up for haj". Reuters. Retrieved 27 September 2012.

- ^ a b Scientists race to understand deadly new virus March 23, 2013; Vol.183 #6 Science News

- ^

Al-Ahdal, MN.; Al-Qahtani, AA.; Rubino, S. (2012). "Coronavirus respiratory illness in Saudi Arabia". J Infect Dev Ctries. 6 (10): 692–4. doi:10.3855/jidc.3084. PMID 23103889.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Press Association (4 July 2013). "Britain records new death from MERS virus". Huffington Post. Retrieved 18 July 2013.

- ^ The Ministry of Social Affairs and Health in France has informed WHO of one confirmed case with infection of the novel coronavirus May 8, 2013 WHO.int

- ^ Nouveau coronavirus - Point de situation : Un nouveau cas d’infection confirmé May 12, 2013 social-sante.gouv.fr

- ^ Savary, Pierre. "First coronavirus sufferer in France dies in hospital | Reuters". Uk.reuters.com. Retrieved 2013-05-31.

- ^ a b "New SARS-Linked Virus Kills Man in France". Associated Press in the Express. Associated Press. 29 May 2013.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Roos, R. (20 May 2013). "Coronavirus cases, deaths reported in Tunisia, Saudi Arabia". Center for Infectious Disease Research & Policy (CIDRAP). Retrieved 22 May 2013.

- ^ . Reuters http://www.reuters.com/article/2013/05/31/us-coronavirus-italy-idUSBRE94U15M20130531. Retrieved 2013-06-01.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help); Unknown parameter|itle=ignored (help) - ^ "CIDRAP Italy resident has MERS after trip to Jordan". Cidrap.umn.edu. Retrieved 2013-06-01.

- ^ "How threatening is the new coronavirus?". BBC. 24 September 2012. Retrieved 27 September 2012.

- ^ "Novel coronavirus infection". World Health Organization. 25 September 2012. Retrieved 27 September 2012.

- ^ "Novel coronavirus update—new virus to be called MERS-CoV". World Health Organization. 16 May 2013.

- ^ a b c "Pandemic preparedness: Coming, ready or not". The Economist. 20 April 2013. Cite error: The named reference "Economist20apr2013" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ "Egyptian Virologist Who Discovered New SARS-Like Virus Fears Its Spread". Mpelembe. 13 May 2013. Retrieved 25 May 2013.

- ^ Ian Sample; Mark Smith (15 March 2013). "Coronavirus victim's widow tells of grief as scientists scramble for treatment". The Guardian. Retrieved 25 May 2013.

- ^ Sample, Ian (15 March 2013). "Coronavirus: Is this the next pandemic?". The Guardian. Retrieved 25 May 2 13.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Yang, Jennifer (21 October 2012). "How medical sleuths stopped a deadly new SARS-like virus in its tracks". Toronto Star. Retrieved 25 May 2013.

- ^ "Erasmus MC: no restrictions for public health research into MERS coronavirus" (Press release). Rotterdam: Erasmus MC. 24 May 2013.

External links