Hakka Chinese

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2010) |

| Hakka | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

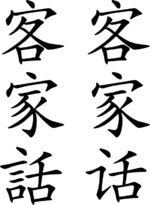

| Traditional Chinese | 客家話 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 客家话 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hakka | Hak-kâ-fa or Hak-kâ-va | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hakka | |

|---|---|

| 客家話 / 客家话 | |

| |

| Native to | People's Republic of China, Thailand, Malaysia, Taiwan, Japan (due to presence of Taiwanese community in Tokyo-Yokohama Metropolitan Area), Singapore, Philippines, Indonesia, Mauritius, Suriname, South Africa, India and other countries where Hakka Chinese migrants have settled. |

| Region | in China: Eastern Guangdong province; adjoining regions of Fujian and Jiangxi provinces |

Native speakers | 34 million |

| hanzi, romanization[1] | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | none (legislative bills have been proposed for it to be one of the 'national languages' in the Republic of China); one of the statutory languages for public transport announcements in the ROC [2]; ROC government sponsors Hakka language television station to preserve language |

| Regulated by | The Guangdong Provincial Education Department created an official romanisation of Meixian Hakka dialect in 1960, one of four languages receiving this status in Guangdong. It is called Kejiahua Pinyin Fang'an. |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | zh (Chinese) |

| ISO 639-2 | chi (B) zho (T) |

| ISO 639-3 | hak |

| |

Hakka or Kejia is one of the main subdivisions of the Chinese language spoken predominantly in southern China by the Hakka people and descendants in diaspora throughout East and Southeast Asia and around the world.

Due to its usage in scattered isolated regions where communication is limited to the local area, the Hakka language has developed numerous variants or dialects, spoken in Guangdong, Fujian, Jiangxi, Guangxi, Sichuan, Hunan, and Guizhou provinces, including Hainan island, Singapore and Taiwan. Hakka is not mutually intelligible with Mandarin, Wu, Minnan, and most of the significant spoken variants of the Chinese language.

There is a pronunciation difference between the Taiwanese Hakka dialect and the Guangdong Hakka dialect. Among the dialects of Hakka, the Moi-yen/Moi-yan (梅縣, Pinyin: Méixiàn) dialect of northeast Guangdong has been typically viewed as a prime example of the Hakka language, forming a sort of standard dialect.

The Guangdong Provincial Education Department created an official romanization of Moiyen in 1960, one of four languages receiving this status in Guangdong.

Etymology

The name of the Hakka people who are the predominant original native speakers of the language literally means "guest families" or "guest people": Hak 客 (Mandarin: kè) means "guest", and ka 家 (Mandarin: jiā) means "family". Amongst themselves, Hakka people variously called their language Hak-ka-fa (-va) 客家話, Hak-fa (-va), 客話, Tu-gong-dung-fa (-va) 土廣東話, literally, "Native Guangdong language," and Ngai-fa (-va) 話, "My/our language".

History

Early history

The Hakka people have their origins in several episodes of migration from northern China into southern China during periods of war and civil unrest.[2] The forebears of the Hakka came from present-day Henan and Shaanxi provinces, and brought with them features of Chinese languages spoken in those areas during that time. (Since then the speech in those regions has evolved into dialects of modern Mandarin.) Hakka is quite conservative, and is generally closer to Middle Chinese than other modern Chinese languages.[3] The presence of many archaic features occur in modern Hakka, including final consonants -p -t -k, as are found in other modern southern Chinese languages, but which have been lost in Mandarin. The distance between Hakka and the more well-known Cantonese may be compared to that between Portuguese and Spanish, whereas Mandarin might be compared to French — more distantly related, and with a quite different phonology.

Due to the migration of its speakers, the Hakka language may have been influenced by other language areas through which the Hakka-speaking forebears migrated. For instance, common vocabulary are found in Hakka, Min, and She (Hmong-Mien) languages.

Some people consider Hakka to have mixed with other languages, such as the language of the She people, throughout its development.

Linguistic development

A regular pattern of sound change can generally be detected in Hakka, as in most Chinese languages, of the derivation of lexemes from earlier forms of Chinese. Some examples:

- The lexeme represented by the characters 武 (war, martial arts) or 屋 (room, house), pronounced roughly mwio and uk in Early Middle Chinese is vu and vuk in Hakka respectively (Mandarin: wu).

- Lexemes corresponding with characters 人 and 日, among others, are pronounced with a ng consonant in Hakka (人:ngin, 日:ngit), and have a corresponding reading in Mandarin as an initial r- consonant.

- The consonant initial of the lexeme corresponding with the character 話 (word, speech; Mandarin hua) is pronounced f or v in Hakka (v does not properly exist as a distinct unit in many Chinese languages).

- The initial consonant of 學 hɔk usually corresponds with a h [h] approximant in Hakka and a voiceless alveo-palatal fricative (x [ɕ]) or velar fricative (h [x]) in Mandarin [citation needed].

Phonology

Moiyen

Dialect initials

There are no voiced plosives ([b] [d] [ɡ]) in Hakka, but it exhibits two sets of voiceless stops, an unaspirated set ([p] [t] [k]), and the other aspirated ([pʰ] tʰ] [kʰ]).

| Labial | Dental | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | /m/ ‹m› | /n/ ‹n› | /ɲ/ ‹ng(i)›* | /ŋ/ ‹ng›* | ||

| Plosive | plain | /p/ ‹b› | /t/ ‹d› | /k/ ‹g› | (ʔ) | |

| aspirated | /pʰ/ ‹p› | /tʰ/ ‹t› | /kʰ/ ‹k› | |||

| Affricate | plain | /ts/ ‹z›* | /tɕ/ ‹j(i)›* | |||

| aspirated | /tsʰ/ ‹c›* | /tɕʰ/ ‹q(i)›* | ||||

| Fricative | /f/ ‹f› | /s/ * | /ɕ/ ‹x(i)›* | /h/ ‹h› | ||

| Approximant | /ʋ/ ‹v› | /l/ ‹l› | /j/ ‹y› | |||

* When the initials [ts] <z>, [tsʰ] <c>, [s] <s>, and [ŋ] <ng>, are followed by a palatal medial [j] <i>, they become [tɕ] <j>, [tɕʰ] <q>, [ɕ] <x>, and [ɲ] <ng>, respectively.

Rimes

Moiyen Hakka has six vowels, [i ɨ ɛ a ə ɔ u], that are romanised as i, ê, a, e, o and u, respectively. The palatisation medial ([j]) is represented by i and the labialisation medial ([w]) is represented as u.

Moreover, Hakka rimes exhibits the final consonants found in Middle Chinese, namely [m, n, ŋ, p, t, k] which are romanised as m, n, ng, b, d, and g respectively in the official Moiyen romanisation.

| vowel | medial + vowel | -i | -u | -m | -n | -ŋ | -p | -t | -k | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Syllabics | m | ŋ | ||||||||

| a | ai | au | am | an | aŋ | ap | at | ak | ||

| ia | iai | iau | iam | ian | iaŋ | iap | iat | iak | ||

| ua | uai | uan | uaŋ | uat | uak | |||||

| ɛ | ɛu | ɛm | ɛn | ɛp | ɛt | |||||

| iɛ | iɛn | iɛt | ||||||||

| uɛ | uɛn | uɛt | ||||||||

| i | iu | im | in | ip | it | |||||

| ɔ | ɔi | ɔn | ɔŋ | ɔt | ɔk | |||||

| iɔ | iɔn | iɔŋ | iɔk | |||||||

| uɔ | uɔn | uɔŋ | uɔk | |||||||

| u | ui | un | uŋ | ut | uk | |||||

| iui | iun | iuŋ | iut | iuk | ||||||

| ɨ | əm | ən | əp | ət |

Tones

Moiyen has four tones, which are reduced to two before a final stop consonant. The Middle Chinese fully voiced initial characters became aspirated voiceless initial characters in Hakka. Before that happened, the four Middle Chinese 'tones', ping, shang, qu, ru, underwent a voicing split in the case of ping and ru, giving the dialect six tones in traditional accounts.

| Tone number | Tone name | Hanzi | Tone letters | number | English |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | yin ping | 陰平 | ˦ | 44 | high |

| 2 | yang ping | 陽平 | ˩ | 11 | low |

| 3 | shang | 上 | ˧˩ | 31 | low falling |

| 4 | qu | 去 | ˥˧ | 53 | high falling |

| 5 | yin ru | 陰入 | ˩ʔ | 1 | low checked |

| 6 | yang ru | 陽入 | ˥ʔ | 5 | high checked |

These so called yin-yang tonal splittings developed mainly as a consequence of the type of initial a Chinese character had during the Middle Chinese stage in the development of Chinese languages, with voiceless initial characters [p- t- k-] tending to become of the yin type, and the voiced initial characters [b- d- ɡ-] developing into the yang type. In modern Moiyen Hakka however, part of the Yin Ping tone characters have sonorant initials [m n ŋ l] originally from the Middle Chinese Shang tone characters and fully voiced Middle Chinese Qu tone characters, so the voiced/voiceless distinction should be taken only as a rule of thumb.

Hakka tone contours differs more as one moves away from Moiyen. For example the Yin Ping contour is ˧ (33) in Changting (长汀) and ˨˦ (24) in Sixian (四县), Taiwan.

Hakka Entering Tone

Hakka preserves all of the entering tones of Middle Chinese and it is split into two registers. The Meixian Hakka dialect often taken as the paradigm gives the following:

- 陰入 [ ˩ ] a low pitched checked tone

- 陽入 [ ˥ ] a high pitched checked tone

Middle Chinese entering tone syllables ending in [k] whose vowel clusters have become front high vowels like [i] and [ɛ] shifts to syllables with [t] finals in modern Hakka[4] as seen in the following table.

| Character | Guangyun Fanqie | Middle Chinese reconstruction[5] |

Hakka | Main meaning in English |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 職 | 之翼切 | tɕĭək | tsit˩ | vocation, profession |

| 力 | 林直切 | lĭək | lit˥ | strength, power |

| 食 | 乗力切 | dʑʰĭək | sit˥ | eat, consume |

| 色 | 所力切 | ʃĭək | sɛt˩ | colour, hue |

| 德 | 多則切 | tək | tɛt˩ | virtue |

| 刻 | 苦得切 | kʰək | kʰɛt˩ | carve, engrave, a moment |

| 北 | 博墨切 | pək | pɛt˩ | north |

| 國 | 古或切 | kuək | kʷɛt˩ | country, state |

Tone sandhi

For Moiyen Hakka, the yin ping and qu tone characters exhibit sandhi when the following character has a lower pitch. The pitch of the yin ping tone changes from ˦ (44) to ˧˥ (35) when sandhi occurs. Similarly, the qu tone changes from ˥˧ (53) to ˦ (55) under sandhi. These are shown in red in the following table.

| + ˦ Yin Ping | + ˩ Yang Ping | + ˧˩ Shang | + ˥˧ Qu | + ˩ʔ Yin Ru | + ˥ʔ YangRu | + Neutral | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ˦ Yin Ping + | ˦.˦ | ˧˥.˩ | ˧˥.˧˩ | ˧˥.˥˧ | ˧˥.˩ʔ | ˦.˥ʔ | ˧˥.˧ |

| ˥˧ Qu + | ˥˧.˦ | ˥.˩ | ˥.˧˩ | ˥.˥˧ | ˥.˩ʔ | ˥˧.˥ʔ | ˥.˧ |

The neutral tone occurs in some postfixes used in Hakka. It has a mid pitch.

Dialects

The Hakka language has as many regional dialects as there are counties with Hakka speakers in the majority. Some of these Hakka dialects are not mutually intelligible with each other. Surrounding Meixian are the counties of Pingyuan 平遠 (Hakka: Pin Yen), Dabu 大埔 (Hakka: Tai Pu), Jiaoling 蕉嶺 (Hakka: Jiao Liang), Xingning 興寧 (Hakka: Hin Nen), Wuhua 五華 (Hakka: Ng Fah), and Fengshun 豐順 (Hakka: Foong Soon). Each is said to have its own special phonological points of interest. For instance, the Xingning does not have rimes ending in [-m] or [-p]. These have merged into [-n] and [-t] ending rimes, respectively. Further away from Meixian, the Hong Kong dialect lacks the [-u-] medial, so whereas Moiyen pronounces the character 光 as [kwɔŋ˦], Hong Kong Hakka dialect pronounces it as [kɔŋ˧], which is similar to the Hakka spoken in neighbouring Shenzhen.

As much as endings and vowels are important, the tones also vary across the dialects of Hakka. The majority of Hakka dialects have six tones. However, there are dialects which have lost all of their Ru Sheng tones, and the characters originally of this tone class are distributed across the non-Ru tones. Such a dialect is Changting 長汀 which is situated in the Western Fujian province. Moreover, there is evidence of the retention of an earlier Hakka tone system in the dialects of Haifeng 海 豐 and Lufeng 陸 豐 situated on coastal south eastern Guangdong province. They contain a yin-yang splitting in the Qu tone, giving rise to seven tones in all (with yin-yang registers in Ping and Ru tones and a Shang tone).

In Taiwan, there are two main dialects: Sixian (Hakka: Siyen 四縣) and Haifeng (Hakka: Hoi Foong 海豐), alternatively known as Hailu (Hakka: Hoiluk 海陸). Hakka dialect speakers found on Taiwan originated from these two regions. Sixian (Hakka: Siyen 四縣) speakers come from Jiaying 嘉應 and surrounding Jiaoling, Pingyuan, Xingning, and Wuhua. Jiaying county later changed its name to Meixian. The Hoiliuk dialect contains postalveloar consonants ([ʃ], [ʒ], [tʃ], etc.), which are uncommon in other southern Chinese languages.

Wuhua Hakka Dialect

Wuhua (五華客家話) (Wuhua dialect owns all common characteristics of Hakka dialect basically, and beyond that, it has another four distinguished phonological features in initials, finals, and tones. However, all phonological characteristics are not consistent from place to place in Wuhua. . Roughly, in consequence, there should be a south-north separation in it.) is characterized by the pronunciation of many voiced Middle Chinese qu-sheng (4th Tone) syllables of Moiyen into the Shang-Sheng (3rd Tone), The Tone-Level of the Yang-Ping is a rising /13/ Instead of the Low-Level /11/ usually found in Moiyen, and Wuhua dialect related areas of Northern Bao'an and Eastern Dongguan, 2 sets of fricatives and affricates (z, c, s, zh, ch, sh, s / ts’ / s and “see note”), similar to Mandarin and The "y" rime found in The Yuebei Hakka group and Sichuan group, and Retroflexed Initials in 知 (Zhi Series) “Knowledge”, 曉 (Xiao Group) “Dawn”, part of 溪 (Xi) “Brook”., poor usage of medials in Grade III and closed rimes, Wuhua Dialect exhibits “latter-word” tone sandhi. Phonologically Wuhua exhibits A North-South separation while lexically it also exhibits a East and Middle Guangdong separation, showing relatedness to Inland and Coast-Side Hakka Dialects. “Lexically it shows east-west separation in Wuhua, which is quite different from the phonological point of view. And outwardly, lexicons in Wuhua show that Wuhua dialect is on the diglossia that separates east and middle Guangdong, and that distinguishes coast-side dialects from inland ones.” Wuhua dialect is transitional; no matter how we see it historically or geographically., Otherwise the Wuhua Hakka dialect is very similar to the Prestige Moiyen – MeiXian Hakka Dialect.

Wuhua can be found in Wuhua County, Jiexi County, Northern Bao'An (Formerly Xin'An, Presently called Shenzhen), Eastern Dongguan, In Yuebei or Northern Guangdong around Shaoguan, in Sichuan and Tonggu, Jiangxi, all of these places has the tonal characteristics of the Wuhua.

Like Wuhua, the Dabu and Xingning dialects of Moiyen – MeiXian have 2 sets of fricatives and affricates.

| Tone number | Hakka Tone name | Hanzi | IPA | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | yin ping | 陰平 | ˦ | high |

| 2 | yang ping | 陽平 | ˩˧ | low rising |

| 3 | shang | 上 | ˧˩ | low falling |

| 4 | qu | 去 | ˥˧ | high falling |

| 5 | yin ru | 陰入 | ˩ | extra low |

| 6 | yang ru | 陽入 | ˥ | extra high |

Wuhua rimes

Most rimes are the same with Moiyen, except for:

| Moiyen | Wuhua |

|---|---|

| uon | on |

| ian | an |

| ien | |

| ui | i |

| in | un |

| uan | has lost the "u" rime, example: "kan" |

| uai | |

| uon | |

| ien | en |

Vocabulary

Like other southern Chinese languages, Hakka retains single syllable words from earlier stages of Chinese; thus it can differentiate a large number of working syllables by tone and rime. This reduces the need for compounding or making words of more than one syllable. However, it is also similar to other Chinese languages in having words which are made from more than one syllable.

| Hakka hanzi | Mandarin hanzi | Prouncation | English | Pinyin |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 人 | [ŋin˩] | person | rén | |

| 碗 | [ʋɔn˦] | bowl | wǎn | |

| 狗 | [kɛu˦] | dog | gǒu | |

| 牛 | [ŋiu˩] | cow | niú | |

| 屋 | [ʋuk˩] | house | wū | |

| 嘴 | [tsɔi˥˧] | mouth | zuǐ | |

| 𠊎 | 我 | [ŋai˩] | me / I | wǒ |

| 佢 | 他/她 | [ki˩] | he / she | tā |

| Hakka hanzi | Prouncation | English |

|---|---|---|

| 日頭 | [ŋit˩ tʰɛu˩] | sun |

| 月光 | [ŋiɛt˥ kʷɔŋ˦] | moon |

| 屋下 | [ʋuk˩ kʰa˦] | home |

| 屋家 | ||

| 電話 | [tʰiɛn˥ ʋa˥˧] | telephone |

| 學堂 | [hɔk˥ tʰɔŋ˩] | school |

Hakka prefers the verb [kɔŋ˧˩] 講 when referring to speaking rather than the Mandarin shuō 說 (Hakka [sɔt˩]).

Hakka uses [sit˥] 食, like Cantonese [sɪk˨] for the verb "to eat" and 飲 [jɐm˧˥] (Hakka [jim˧˩]) for "to drink", unlike Mandarin which prefers chī 吃 (Hakka [kʰiɛt˩]) as "to eat" and hē 喝 (Hakka [hɔt˩]) as "to drink" where the meanings in Hakka are different, to stutter and to be thirsty respectively.

| Hanzi | IPA | English |

|---|---|---|

| 阿妹, 若姆去投墟轉來唔層? | [a˦ mɔi˥, ɲja˦ mi˦ hi˥ tʰju˩ hi˦ tsɔn˧˩ lɔi˩ m˦ tsʰɛn˩] | Has your mother returned from going to the market yet, child? |

| 其佬弟捉到隻蛘葉來搞. | [kja˦ lau˧˩ tʰai˦ tsuk˧ tau˧˩ tsak˩ jɔŋ˩ jap˥ lɔi˩ kau˧˩] | His younger brother caught a butterfly to play with. |

| 好冷阿, 水桶个水敢凝冰阿 | [hau˧˩ laŋ˦ ɔ˦, sui˧˩ tʰuŋ˧ kai˥˧ sui˧˩ kam˦ kʰɛn˩ pɛn˦ ɔ˦] | It's very cold, the water in the bucket has frozen over. |

Writing systems

Various dialects of Hakka have been written in a number of Latin orthographies, largely for religious purposes, since at least the mid-19th century.

Currently the single largest work in Hakka is the New Testament and Psalms (1993, 1138 pp., see [3]), although that is expected to be surpassed soon by the publication of the Old Testament. These works render Hakka in both romanization and Han characters (including ones unique to Hakka) and are based on the dialects of Taiwanese Hakka speakers. The work of Biblical translation is being performed by missionaries of the Presbyterian Church in Canada.

The popular Le Petit Prince has also been translated into Hakka (2000, indirectly from English), specifically the Miaoli dialect of Taiwan (itself a variant of the Sixian dialect). This also was dual-script, albeit using the Tongyong Pinyin scheme.

See also

References

Footnotes

- ^ Hakka was written in Chinese characters by missionaries around the turn of the 20th century.[1]

- ^ Hakka Migration

- ^ Language

- ^ http://www.sungwh.freeserve.co.uk/chinese/cjkvnum.htm

- ^ http://kanji-database.sourceforge.net/dict/sbgy/v5.html

Notations

- Branner, David Prager (2000). Problems in Comparative Chinese Dialectology — the Classification of Miin and Hakka. Trends in Linguistics series, no. 123. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. ISBN 31-101-5831-0.