Israelites

This article uses texts from within a religion or faith system without referring to secondary sources that critically analyze them. (December 2010) |

| Part of a series on |

| Jews and Judaism |

|---|

According to the Bible the Israelites were a Hebrew-speaking people of the Ancient Near East who inhabited the Land of Canaan (the modern day Israel, western Jordan, southern Lebanon and Palestinian Territories) during the monarchic period (11th to 7th centuries BCE).

The word "Israelite" derives from the Biblical Hebrew ישראל (Standard: Yisraʾel; Tiberian: Yiśrāʾēl; ISO 259-3: Yiśraˀel). The ethnonym is attested as early as the 13th century BCE in an Egyptian inscription. The Hebrew Bible etymologizes the name as from yisra "to prevail over" or "to struggle/wrestle with", and el, "God, the divine".[1][2] The eponymous biblical patriarch of the Israelites is Jacob, who wrestled with a "man" who was not expressly called an angel of God, but who gave him a blessing from God, and renamed him "Israel" because he had "power with God". (Genesis 32:24–32)

The biblical term "Israelites" (or the Twelve Tribes or Children of Israel) means both a people (the descendants of the patriarch Jacob/Israel, and the historical population of the kingdom of Israel), and followers of the God of Israel and Mosaic law.[3] In Modern Hebrew usage, an Israelite is, broadly speaking, a lay member of the Jewish faith, as opposed to the priestly orders of Kohanim and Levites.

The name Hebrews is sometimes used synonymously with "Israelites". For the post-exilic period, beginning in the 5th century BCE, the remnants of the Israelites came to be referred to as Jews, named for the kingdom of Judah. This change is explicit in the Book of Esther (4th century BCE).[4] It replaced the title children of Israel.[5]

Although most literary references to them are located in the Hebrew Bible, there is also abundant non-biblical archaeological and historical evidence of ancient Israel and Judah.

Terminology

Prior to a meeting with rival brother, Esau; the biblical patriarch Jacob wrestles an angel on the shores of the Jabbok & is given the name 'Israel'. [1][2] Throughout the rest of the Torah, Jacob is referred to at times as both Jacob and Israel, depending on which aspect of his character the text means to convey.

In modern Hebrew, B'nei Yisrael ("Children of Israel") can denote the Jewish people at any time in history; it is typically used to emphasize Jewish religious identity. From the period of the Mishna (but probably used before that period) the term Yisrael ("an Israel") acquired an additional narrower meaning of Jews of legitimate birth other than Levites and Aaronite priests (kohanim). In modern Hebrew this contrasts with the term Yisraeli, a citizen of the modern State of Israel, regardless of religion or ethnicity (English "Israeli").

The Greek term Jew historically refers to a member of the tribe of Judah, which formed the nucleus of the kingdom of Judah. The term Hebrew, perhaps related to the name of the Habiru nomads, has Eber as an eponymous biblical patriarch. It is used synonymously with "Israelites", or as an ethnolinguistic term of the historical speakers of the Hebrew language in general.

Biblical Israelites

| Tribes of Israel |

|---|

|

The following is a summary of pages 18-20 of Stephen L. Wylen's "The Jews in the Time of Jesus: An Introduction"[6]

- Pentateuch

The Torah traces the Israelites to the patriarch Jacob, grandson of Abraham, who was renamed Israel after a mysterious incident in which he wrestles all night with an angel. Jacob's twelve sons (in order), Reuben, Simeon, Levi, Judah, Dan, Naphtali, Gad, Asher, Issachar, Zebulun, Joseph and Benjamin, become the ancestors of twelve tribes, with the exception of Joseph, whose two sons Mannasseh and Ephraim become tribal eponyms.

Jacob and his sons are forced by famine to go down into Egypt. When they arrive they and their families are 70 in number, but within four generations they have increased to 600,000 men of fighting age, and the Pharaoh of Egypt, alarmed, first enslaves them and then orders the death of all male Hebrew children. The God of Israel reveals his name to Moses, a Hebrew of the line of Levi; Moses leads the Israelites out of bondage and into the desert, where God gives them their laws and the Israelites agree to become his people. Nevertheless, the Israelites lack complete faith in God, and the generation which left Egypt is not permitted to enter the Promised Land.

- Former Prophets

Following the death of the generation of Moses a new generation, led by Joshua, enters Canaan and takes possession of the land in accordance with the curse placed upon Canaan by Noah. Yet even now the Israelites lack strength in God in the face of the peoples of the land, and periods of weakness and backsliding alternate with periods of resilience under a succession of Judges. Eventually the Israelites ask for a king, and God gives them Saul. David, the youngest (divinely favoured) son of Jesse of Bethlehem would succeed Saul. Under David the Israelites establish the kingdom of God, and under David's son Solomon they build the Temple where God takes his earthly dwelling among them. Yet Solomon sins by allowing his foreign wives to worship their own gods, and so on his death the kingdom is divided in two.

The kings of the northern kingdom of Israel are uniformly bad, permitting the worship of other gods and failing to enforce the worship of God alone, and so God eventually allows them to be conquered and dispersed among the peoples of the earth; in their place strangers settle the northern land. In Judah some kings are good and enforce the worship of God alone, but many are bad and permit other gods, even in the Temple itself, and at length God allows the Judah to fall to her enemies, the people taken into captivity in Babylon, the land left empty and desolate, and the Temple itself destroyed.

- Ezra-Nehemiah-Chronicles

Yet despite these events God does not forget his people, but sends Cyrus, king of Persia as his messiah to deliver them from bondage. The Israelites are allowed to return to Judah and Benjamin, the Temple is rebuilt, the priestly orders restored, and the service of sacrifice resumed. Through the offices of the sage Ezra Israel is constituted as a holy community, holding itself apart from all other peoples, bound by the Law.

Tribes and peoples

This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2011) |

Although most traditional interpretations of Jewish history view the Israelites as the ancestors of both the Kingdom of Israel and that of Judah, which arose only after David's rule, and Hebrews as an alternative name for them, the text makes a distinction between groups labeled Hebrews, Judahites, and Israelites. Israelites consistently refers to Saul's forces. It also is used to refer to the supporters of the rebellions against David's reign, in contrast to his supporters. Judahites consistently refers to David's supporters during the rebellions against his rule, in contrast to the rebels. Hebrews is consistently used to designate a group distinct from both Israelites and Judahites, and who sometimes take the side of the Philistines against Israel and Judah. It is weakly associated with Jonathan initially, and then more strongly with David's band of outlaws. However, this labeling appears to be only for convenient grouping, since there are several textual examples that clarify that the Hebrews are of the same people as the Israelites: I Samuel 13:3-4, I Samuel 13:19-20, and I Samuel 14:11-12.

Hasmonean conversions

This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2010) |

After the Persian conquest of Babylon in 539 Judah (Hebrew: יְהוּדָה Yehuda) remained a province of the Persian empire. This continued into the following Hellenistic period, when Yehud was a province sometimes of Ptolemaic Egypt and sometimes of Seleucid Syria, but in the early part of the 2nd century BCE a revolt against the Seleucids led to the establishment of an independent Jewish kingdom under the Hasmonean dynasty. The Hasmoneans adopted a deliberate policy of imitating and reconstituting the Davidic kingdom, and as part of this forcibly converted to Judaism their neighbours in the Land of Israel. The new Israelites included Nabatean groups such as the Zabadeans and Itureans, the peoples of the former Philistine cities, the people of Galilee, and the Moabites, Ammonites and Edomites.

"Israelites" in modern Judaism

In the Hellenistic and early Roman periods (i.e., around the time of Christ), and despite the exclusivism championed by the Book of Ezra, Judaism became a proselytising religion. As proselytised (and conquered) groups were assimilated into the Israelite lineage the old tribal divisions fell into disuse, and the major divisions within Judaism thus became:

- Kohanim (descended from the lineage of Aaron, the first High Priest in the time of Moses)

- Levites (other descendants of Levi)

- Israelites

This threefold division of the Jewish people persists to this day. To avoid confusion with the broader use of the term Israelite or the modern term Israeli, a member of the Israelite, as opposed to Levite or Aaronite, lineage is usually referred to as a Yisrael (an Israel) and not a Yisraeli (which could mean Israelite in the broader sense or in modern Hebrew, an Israeli).

Modern groups descendant from the Israelites

This section may contain material not related to the topic of the article. (May 2011) |

Jews

Jews (Hebrew: יְהוּדִים, Yehudim), also known as the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group originating in the Israelites or Hebrews of the Ancient Near East. Converts to Judaism have been absorbed into the Jewish people throughout the millennia. There are distinct ethnic divisions among Jews, most of which are primarily the result of geographic branching from an originating Israelite population, and subsequent independent evolutions. According to the Books of Chronicles chapter 9 line 2, the Jews who took part in The Return to Zion (whom modern Jews are originated from) are stated to be from the Tribe of Judah (alongside the Tribe of Simeon that were absorbed into it), the Tribe of Benjamin, the Tribe of Levi (Levites and Priests) and also from the tribes of Ephraim and Manasseh (which some biblical scholars consider to be a referring name describing the remaining population of the Northern Kingdom of Israel from all ten tribes who were not exiled during the ten tribes exile; they had stayed to live in their homes and later joined the Israelites of the Kingdom of Judah at the time of King Hezekiah, and formed the Jews of the Babylonian Exile era).

Ashkenazi Jews

Ashkenaz is the Hebrew word for "Germany". There are several populations which have lived in Germany at some point in the past 1,000 years and fall under the umbrella term for the group. There is evidence that Jews had settled in Germany since the Roman Era; they were probably merchants who followed the Roman Legions during their conquests. Some Ashkenazi Jews are the descendants of Jews who migrated into northern France and Germany around 800–1000 CE, and were later sent into Eastern Europe. Many Ashkenazic Jews are also Sephardic in origin as a result of diaspora from the Spanish Inquisition. In this sense "Ashkenazi" refers to religious practice, appropriated over time, rather than to a strict ethno-geographic division.

Arthur Koestler claimed in his book "The Thirteenth Tribe" (1976) that Ashkenazi Jews are descendants of central European Khazars who converted into Judaism during the 8th century. Koestler argued that by proving Ashkenazi Jews to have no connection with the biblical Jews, European anti-Semitism would lose all basis. In 2006, a study by Doron Behar and Karl Skorecki of the Technion and Ramban Medical Center in Haifa, Israel demonstrated that: 1) the vast majority of Ashkenazi Jews have some Middle Eastern ancestry;[7] 2) Ashkenazi Jews share a common ancestry with other Jewish groups of European origin;[8] and 3) only 5%-8% of the European Ashkenazi Jews (according to recent studies) were found to have originated in non-Jewish European populations.[9] Dr. David Goldstein, a Duke University geneticist and and director of the Duke Center for Human Genome Variation, has noted that the Technion and Ramban team confirmed that genetic drift played a major role in shaping Ashkenazi mitochondrial DNA, therefore mtDNA studies fail to draw a statistically significant linkage between modern Jews and Middle Eastern populations, however, this differs from the patrilineal case, where Dr. Goldstein said there is no question of a Middle Eastern origin.[7]

Sephardic Jews

Sephardim are Jews whose ancestors lived in Spain or Portugal, where they lived for possibly as much as two millennia before being expelled in 1492 by the Catholic Monarchs (see Alhambra decree); they subsequently migrated to North Africa Maghreb and Ottoman Empire (both at the time considered safe havens for Jews). In the Ottoman Empire the Sephardim mostly settled in the European portion of the Empire, and mainly in the major cities such as: Istanbul, Selânik and Bursa. Selânik, which is today known as Thessaloniki and found in modern-day Greece, had a large and flourishing Sephardic community as was the community of Maltese Jews in Malta. Others settled in Italy, the Netherlands and Latin America. A large population of Sephardic refugees who fled via the Netherlands as Marranos eventually settled in Hamburg and Altona Germany in the early 16th century, eventually appropriating Ashkenazic Jewish rituals into their religious practice (see above). One famous figure from the Sephardic Ashkenazic population is Glückel of Hameln. Others among those who settled in the Netherlands, were some who would again relocate to the United States, establishing the country's first organized community of Jews and erecting the United States' first synagogue. Other Sephardim remained in Spain and Portugal as anusim (forced converts to Catholicism), which would also be the fate for those who had migrated to Spanish and Portuguese ruled Latin America.

Mizrachi Jews

Mizrahim are Jews descended from the Jewish communities of the Middle East, North Africa, Central Asia and the Caucasus. The term Mizrahi is used in Israel in the language of politics, media and some social scientists for Jews from the Arab world and adjacent, primarily Muslim-majority countries. This includes Iraqi Jews, Syrian Jews, Lebanese Jews, Maghreb Jews , Yemenite Jews, Persian Jews, Afghan Jews, Bukharian Jews, Kurdish Jews, Mountain Jews, Georgian Jews and Ethiopian Jews.

Yemenite Jews

Temanim are Jews living in Yemen whose geographic and social isolation from the rest of the Jewish community allowed them to develop a liturgy and set of practices that are significantly distinct from those of other Oriental Jewish groups; they themselves comprise three distinctly different groups, though the distinction is one of religious law and liturgy rather than of ethnicity.

Karaite Jews

Karaim are Jews living mostly in Egypt, Iraq, Crimea and Israel. They are distinguished by the form of Judaism they observe. Rabbinic Jews of varying ethnicities have affiliated with the Karaite community throughout the millennia. As such, Karaite Jews are less a Jewish ethnic division, than they are members of a particular branch of Judaism. Karaite Judaism recognizes the Tanakh as the single religious authority of the Jewish people. Linguistic principles and contextual exegesis are used in arriving at the correct meaning of the Torah. Karaite Jews strive to adhere to the plain or most obvious understanding of the text when interpreting the Tanakh. By contrast, Rabbinical Judaism regards an Oral Law (codified and recorded in the Mishnah and Talmuds) as being equally binding on Jews, and mandated by God. In Rabbinical Judaism, the Oral Law forms the basis of religion, morality, and Jewish life. Karaite Jews rely on the use of sound reasoning and the application of linguistic tools to determine the correct meaning of the Tanakh; while Rabbinical Judaism looks toward the Oral law codified in the Talmud, to provide the Jewish community with an accurate understanding of the Hebrew Scriptures.

There are approximately 50,000 adherents of Karaite Judaism, most of whom live in Israel, but exact numbers are not known, as most Karaites have not participated in any religious censuses. The differences between Karaite and Rabbinic Judaism go back more than a thousand years. Rabbinical Judaism originates from the Pharisees of the Second Temple period. Karaite Judaism may have its origins in the Sadducees of the same era. Unlike the Sadducees who recognized only the Torah as binding, Karaite Jews hold the entire Hebrew Bible to be a religious authority. As such, the vast majority of Karaites believe in the resurrection of the dead.[10] Karaite Jews are widely regarded as being halachically Jewish by the Orthodox Rabbinate. Similarly, members of the rabbinic community are considered to be Jews by the Moetzet Hakhamim, if they are patrilineally Jewish. [citation needed]

Anusim

During the Jewish diaspora, Jews who lived in Christian Europe were usually attacked by the local population and were portrayed by many Anti-semites motives, many of them were forced to convert to Christianity by the local population or by the religious leadership, and were called by Jews: "Anusim" ('forced-ones'), they continued practicing Judaism in secret, while living outside as ordinary Christians. The most known case of "Anusim" was the one of the Jews of Spain and Jews of Portugal (although "Anusim" were also in other European countries). On the Muslim countries, many Jews were forced to convert to Islam by force over the years since the rise of the Islamic religion, and the most known case of those conversion was the case of Mashhad Jews, that lived as ordinary Muslims in Persia but kept practicing Judaism, and eventually made an Aliyah and returned being Jewish in Israel. Many Anusim's descendants left Judaism over the years. On December 2008, genetic test showed that 19.8% of the Iberian Peninsula are originated from the Anusim.[11]

Samaritans

The Samaritans, who were once a comparatively large group but are now a very small ethnic and religious group of not more than about 700 people[12] who live in Israel and the West Bank, regard themselves as descendants of the tribes of Ephraim (named by them as Aphrime) and Manasseh (named by them as Manatch). Samaritans adhere to a version of the Torah, known as the Samaritan Pentateuch, which differs in some respects from the Masoretic text, sometimes in important ways, and less so from the Septuagint.

Samaritans do not regard the Tanakh as an accurate or truthful history, and regard only Moses as a prophet. They have their own version of Hebrew and their own script for writing Hebrew, which, is descended directly from the Paleo-Hebrew alphabet, unlike the Jewish script for writing Hebrew which is a stylized form of the Aramaic alphabet the Jews adopted during their captivity in Babylonia.

The Samaritans consider themselves Bnei Yisrael ("Children of Israel" or "Israelites"), but do not regard themselves to be Yehudim (Jews). They view this term "Jews" as a designation for followers of Judaism, which they assert is a related but altered and amended religion brought back by the exiled Israelite returnees which is not the true religion of the ancient Israelites, which according to them, Samaritanism is.

Judaism regards the Samaritans as descendants of the northern tribesmen whom the Assyrians settled in the territory they conquered from the kingdom of Israel. Since one of those tribes was the Cutheans, this is the name used for the Samaritans in the Talmud. Both the Bible and external sources such as Josephus record intermarriage between Jews and Samaritans in the Hellenistic period.

Modern DNA evidence has proven both most of the world's Jews and the Samaritans have a common ancestral lineage to the Israelites, largely on the paternal lines in both cases. Maternally, both Jews and Samaritans have very low rates of intermarriage with local host (for Jews, local populations in their host diaspora regions)[13] or alien (for Samaritans, foreigners resettled in their midst in attempts by ruling foreign elites to obliterate national identities) populations.[14] Both populations' DNA results indicate the groups having had a high percentage of marriage within their respective communities; in contrast to a low percentage of interfaith marriages.

Palestinians

Many genetic surveys have proven that, at least paternally, most of the various Jewish ethnic divisions and the Palestinians – and in some cases other Levantines – are genetically closer to each other than the Palestinians or European Jews to non-Jewish Europeans.[15]

One DNA study by Nebel found genetic evidence in support of historical records that "part, or perhaps the majority" of Muslim Palestinians descend from "local inhabitants, mainly Christians and Jews, who had converted after the Islamic conquest in the seventh century AD".[16] They also found substantial genetic overlap between Muslim Palestinians and Ashkenazi and Sephardic Jews, though with some significant differences that might be explainable by the geographical isolation of the Jews or by immigration of Arab tribes in the first millennium.[16]

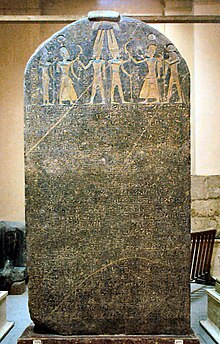

Historical Israelites

The name Israel first appears c. 1209 BCE, at the end of the Late Bronze Age and the very beginning of the period archaeologists and historians call Iron Age I, in an inscription of the Egyptian pharaoh Merneptah. The inscription is very brief and says simply: "Israel is laid waste and his seed is not". The hieroglyph accompanying the name "Israel" indicates that it refers to a people, most probably located in the highlands of Samaria.[17]

Over the next two hundred years (the period of Iron Age I) the number of highland villages increased from 25 to over 300[18] and the settled population doubled to 40,000.[19] There is general agreement that the majority of the population living in these villages was of Canaanite origin.[18] By the 10th century BCE a rudimentary state had emerged in the north-central highlands,[20] and in the 9th century this became a kingdom. The kingdom was sometimes called Israel by its neighbours, but more frequently it was known as the "House (or Land) of Omri."[21] Settlement in the southern highlands was minimal from the 12th through the 10th centuries, but a state began to emerge there in the 9th century,[22] and from 850 onwards a series of inscriptions are evidence of a kingdom which its neighbours refer to as the "House of David."[23]

See also

- Bible

- Gentile

- Half Jewish

- House of Israel (Ghana)

- Israeli Jews

- Israelis

- Kingdom of Israel (united monarchy)

- Noahides

- Shavei Israel

- Tribal allotments of Israel

- Kaifeng Jews

References and notes

- ^ a b Scherman, Rabbi Nosson (editor), The Chumash, The Artscroll Series, Mesorah Publications, LTD, 2006, pages 176–77

- ^ a b Kaplan, Aryeh, "Jewish Meditation", Schocken Books, New York, 1985, page 125

- ^ Watson E. Mills, Roger Aubrey Bullard (eds), Israelite, in "Mercer dictionary of the Bible", p.420

- ^ The people and the faith of the Bible by André Chouraqui, Univ of Massachusetts Press, 1975, p. 43 [1]

- ^ Settings of silver: an introduction to Judaism Stephen M. Wylen, Paulist Press, 2000, ISBN 0-8091-3960-X, p. 59

- ^ The Jews in the time of Jesus: an introduction page 18 Stephen M. Wylen, Paulist Press, 1996, 215 pages

- ^ a b Wade, Nicholas (January 14, 2006). "New Light on Origins of Ashkenazi in Europe". The New York Times.

- ^ Wade, Nicholas (June 9, 2010). "Studies Show Jews' Genetic Similarity". The New York Times.

- ^ http://www.jogg.info/11/coffman.htm

- ^ http://www.karaite-korner.org/karaite_faq.shtml

- ^ http://www.cell.com/AJHG/fulltext/S0002-9297(08)00592-2

- ^ as of 2006

- ^ "Y Chromosome Bears Witness to Story of the Jewish Diaspora". New York Times. 2000.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Template:PDFlink, Hum Mutat 24:248–260, 2004.

- ^ Nebel et al. 2000, Almut Nebel, Ariella Oppenheim, "High-resolution Y chromosome haplotypes of Israeli and Palestinian Arabs reveal geographic substructure and substantial overlap with haplotypes of Jews." Human Genetics 107(6) (December 2000): 630-641

- ^ a b Nebel et al., "High-resolution Y chromosome haplotypes of Israeli and Palestinian Arabs reveal geographic substructure and substantial overlap with haplotypes of Jews." Human Genetics Vol. 107, No. 6, (December 2000), pp. 630–641

- ^ Grabbe 2008, p.75

- ^ a b McNutt 1999, p. 47. Cite error: The named reference "mcnutt47" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ McNutt 1999, p. 70.

- ^ Joffe pp.440 ff.

- ^ Davies, 1992, pp.63-64.

- ^ Joffe p.448-9.

- ^ Joffe p.450.

Bibliography

- Albertz, Rainer (1994) [Vanderhoek & Ruprecht 1992]. A History of Israelite Religion, Volume I: From the Beginnings to the End of the Monarchy. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664227197.

- Albertz, Rainer (1994) [Vanderhoek & Ruprecht 1992]. A History of Israelite Religion, Volume II: From the Exile to the Maccabees. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664227203.

- Albertz, Rainer (2003a). Israel in Exile: The History and Literature of the Sixth Century B.C.E. Society of Biblical Literature. ISBN 9781589830554.

- Albertz, Rainer; Becking, Bob, eds. (2003b). Yahwism After the Exile: Perspectives on Israelite Religion in the Persian Era. Koninklijke Van Gorcum. ISBN 9789023238805.

{{cite book}}:|first2=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Becking, Bob. "Law as Expression of Religion (Ezra 7–10)".{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Amit, Yaira, et al., eds. (2006). Essays on Ancient Israel in its Near Eastern Context: A Tribute to Nadav Na'aman. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 9781575061283.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Davies, Philip R. "The Origin of Biblical Israel".{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Avery-Peck, Alan, et al., eds. (2003). The Blackwell Companion to Judaism. Blackwell. ISBN 9781577180593.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Murphy, Frederick J. R. "Second Temple Judaism".{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Barstad, Hans M. (2008). History and the Hebrew Bible. Mohr Siebeck. ISBN 9783161498091.

- Becking, Bob, ed. (2001). Only One God? Monotheism in Ancient Israel and the Veneration of the Goddess Asherah. Sheffield Academic Press. ISBN 9781841271996.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Dijkstra, Meindert. "El the God of Israel, Israel the People of YHWH: On the Origins of Ancient Israelite Yahwism".{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) Dijkstra, Meindert. "I Have Blessed You by Yahweh of Samaria and His Asherah: Texts with Religious Elements from the Soil Archive of Ancient Israel".{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Becking, Bob; Korpel, Marjo Christina Annette, eds. (1999). The Crisis of Israelite Religion: Transformation of Religious Tradition in Exilic and Post-Exilic Times. Brill. ISBN 9789004114968.

{{cite book}}:|first2=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Niehr, Herbert. Religio-Historical Aspects of the Early Post-Exilic Period. - Bedford, Peter Ross (2001). Temple Restoration in Early Achaemenid Judah. Brill. ISBN 9789004115095.

- Ben-Sasson, H.H. (1976). A History of the Jewish People. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674397312.

- Blenkinsopp, Joseph (1988). Ezra-Nehemiah: A Commentary. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780664221867.

- Blenkinsopp, Joseph; Lipschits, Oded, eds. (2003). Judah and the Judeans in the Neo-Babylonian Period. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 9781575060736.

{{cite book}}:|first2=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Blenkinsopp, Joseph. "Bethel in the Neo-Babylonian Period".{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) Lemaire, Andre. "Nabonidus in Arabia and Judea During the Neo-Babylonian Period".{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Blenkinsopp, Joseph (2009). Judaism, the First Phase: The Place of Ezra and Nehemiah in the Origins of Judaism. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802864505.

- Brett, Mark G. (2002). Ethnicity and the Bible. Brill. ISBN 9780391041264. Edelman, Diana. "Ethnicity and Early Israel".

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Bright, John (2000). A History of Israel. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664220686.

- Coogan, Michael D., ed. (1998). The Oxford History of the Biblical World. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195139372.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Stager, Lawrence E. "Forging an Identity: The Emergence of Ancient Israel".{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Coogan, Michael D. (2009). A Brief Introduction to the Old Testament. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195332728.

- Coote, Robert B.; Whitelam, Keith W. (1986). "The Emergence of Israel: Social Transformation and State Formation Following the Decline in Late Bronze Age Trade". Semeia (37): 107–47.

- Davies, Philip R. (1992). In Search of Ancient Israel. Sheffield. ISBN 9781850757375.

- Davies, Philip R. (2009). "The Origin of Biblical Israel". Journal of Hebrew Scriptures. 9 (47).

- Day, John (2002). Yahweh and the Gods and Goddesses of Canaan. Sheffield Academic Press. ISBN 9780826468307.

- Dever, William (2001). What Did the Biblical Writers Know, and When Did They Know It?. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802821263.

- Dever, William (2003). Who Were the Early Israelites and Where Did They Come From?. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802809759.

- Dever, William (2005). Did God Have a Wife?: Archaeology and Folk Religion in Ancient Israel. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802828521.

- Dunn, James D.G; Rogerson, John William, eds. (2003). Eerdmans commentary on the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802837110.

{{cite book}}:|first2=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Rogerson, John William. "Deuteronomy".{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Edelman, Diana, ed. (1995). The Triumph of Elohim: From Yahwisms to Judaisms. Kok Pharos. ISBN 9789039001240.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Finkelstein, Neil Asher; Silberman (2001). The Bible Unearthed. ISBN 9780743223386.

- Finkelstein, Israel; Mazar, Amihay; Schmidt, Brian B. (2007). The Quest for the Historical Israel. Society of Biblical Literature. ISBN 9781589832770. Mazar, Amihay. "The Divided Monarchy: Comments on Some Archaeological Issues".

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Gnuse, Robert Karl (1997). No Other Gods: Emergent Monotheism in Israel. Sheffield Academic Press. ISBN 9781850756576.

- Golden, Jonathan Michael (2004a). Ancient Canaan and Israel: An Introduction. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195379853.

- Golden, Jonathan Michael (2004b). Ancient Canaan and Israel: New Perspectives. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781576078976.

- Goodison, Lucy; Morris, Christine (1998). Goddesses in Early Israelite Religion in Ancient Goddesses: The Myths and the Evidence. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 9789004104105.

- Grabbe, Lester L. (2004). A History of the Jews and Judaism in the Second Temple Period. T&T Clark International. ISBN 9780567043528.

- Grabbe, Lester L., ed. (2008). Israel in Transition: From Late Bronze II to Iron IIa (c. 1250–850 B.C.E.). T&T Clark International. ISBN 9780567027269.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Greifenhagen, F.V (2002). Egypt on the Pentateuch's ideological map. Sheffield Academic Press. ISBN 9780826462114.

- Joffe, Alexander H. (2006). The Rise of Secondary States in the Iron Age Levant. University of Arizona Press.

- Killebrew, Ann E. (2005). Biblical Peoples and Ethnicity: An Archaeological Study of Egyptians, Canaanites, and Early Israel, 1300–1100 B.C.E. Society of Biblical Literature. ISBN 9781589830974.

- King, Philip J.; Stager, Lawrence E. (2001). Life in Biblical Israel. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 0664221483.

- Kuhrt, Amélie (1995). The Ancient Near East c. 3000–330 BC. Routledge. ISBN 9780415167635.

- Lemche, Niels Peter (1998). The Israelites in History and Tradition. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664227272.

- Levy, Thomas E. (1998). The Archaeology of Society in the Holy Land. Continuum International Publishing. ISBN 9780826469960. LaBianca, Øystein S.; Younker, Randall W. "The Kingdoms of Ammon, Moab and Edom: The Archaeology of Society in Late Bronze/Iron Age Transjordan (c. 1400–500 CE)".

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Lipschits, Oded (2005). The Fall and Rise of Jerusalem. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 9781575060958.

- Lipschits, Oded, et al., eds. (2006). Judah and the Judeans in the Fourth Century B.C.E. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 9781575061306.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Kottsieper, Ingo. "And They Did Not Care to Speak Yehudit".{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) Lipschits, Oded; Vanderhooft, David. "Yehud Stamp Impressions in the Fourth Century B.C.E.".{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Markoe, Glenn (2000). Phoenicians. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520226142.

- Mays, James Luther, et al., eds. (1995). Old Testament Interpretation. T&T Clarke. ISBN 9780567292896.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Miller, J. Maxwell. "The Middle East and Archaeology".{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - McNutt, Paula (1999). Reconstructing the Society of Ancient Israel. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664222659.

- Merrill, Eugene H. (1995). "The Late Bronze/Early Iron Age Transition and the Emergence of Israel". Bibliotheca Sacra. 152 (606): 145–62.

- Middlemas, Jill Anne (2005). The Troubles of Templeless Judah. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199283866.

- Miller, James Maxwell; Hayes, John Haralson (1986). A History of Ancient Israel and Judah. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 066421262X.

- Miller, Robert D. (2005). Chieftains of the Highland Clans: A History of Israel in the 12th and 11th Centuries B.C. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802809889.

- Nodet, Étienne (1999) [Editions du Cerf 1997]. A Search for the Origins of Judaism: From Joshua to the Mishnah. Sheffield Academic Press. ISBN 9781850754459.

- Pitkänen, Pekka (2004). "Ethnicity, Assimilation and the Israelite Settlement" (PDF). Tyndale Bulletin. 55 (2): 161–82.

- Silberman, Neil Asher; Small, David B., eds. (1997). The Archaeology of Israel: Constructing the Past, Interpreting the Present. Sheffield Academic Press. ISBN 9781850756507.

{{cite book}}:|first2=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Hesse, Brian; Wapnish, Paula. "Can Pig Remains Be Used for Ethnic Diagnosis in the Ancient Near East?".{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Smith, Mark S. (2001). Untold Stories: The Bible and Ugaritic Studies in the Twentieth Century. Hendrickson Publishers.

- Smith, Mark S.; Miller, Patrick D. (2002) [Harper & Row 1990]. The Early History of God. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802839725.

- Soggin, Michael J. (1998). An Introduction to the History of Israel and Judah. Paideia. ISBN 9780334027881.

- Thompson, Thomas L. (1992). Early History of the Israelite People. Brill. ISBN 9789004094833.

- Van der Toorn, Karel (1996). Family Religion in Babylonia, Syria, and Israel. Brill. ISBN 9789004104105.

- Van der Toorn, Karel; Becking, Bob; Van der Horst, Pieter Willem (1999). Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible (2d ed.). Koninklijke Brill. ISBN 9789004111196.

- Vaughn, Andrew G.; Killebrew, Ann E., eds. (1992). Jerusalem in Bible and Archaeology: The First Temple Period. Sheffield. ISBN 9781589830660.

{{cite book}}:|first2=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Cahill, Jane M. "Jerusalem at the Time of the United Monarchy".{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) Lehman, Gunnar. "The United Monarchy in the Countryside".{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Wylen, Stephen M. (1996). The Jews in the Time of Jesus: An Introduction. Paulist Press. ISBN 9780809136100.

- Zevit, Ziony (2001). The Religions of Ancient Israel: A Synthesis of Parallactic Approaches. Continuum. ISBN 9780826463395.