I Ching

The I Ching | |

| Author | Fu Xi (trad.) |

|---|---|

| Publication place | China |

| Media type | Book |

| I Ching | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 易經 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 易经 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Yìjīng | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "Classic of Changes" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 역경 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hiragana | えききょう | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Template:ChineseText The I Ching (/ˈiː ˈdʒɪŋ/;[1] Chinese: 易經; pinyin: Yìjīng), also known as the Classic of Changes or Book of Changes in English, is an ancient divination text and the oldest of the Chinese classics. The I Ching was originally a divination manual in the Western Zhou period, but over the course of the Warring States period and early imperial period was transformed into a cosmological text with a series of philosophical commentaries known as the "Ten Wings."[2] After becoming part of the Five Classics in the 2nd century BC, the I Ching was the subject of scholarly commentary and the basis for divination practice for centuries across the Far East, and eventually took on an influential role in Western understanding of Eastern thought.

The I Ching uses a type of divination called cleromancy, which produces apparently random numbers. Six random numbers are turned into a hexagram, which can then be looked up in the I Ching book, arranged in an order known as the King Wen sequence. The interpretation of the readings found in the I Ching is the matter of centuries of debate, and many commentators have used the book symbolically, often to provide guidance for moral decision-making as informed by Confucianism. The hexagrams themselves have often acquired cosmological significance and paralleled with many other traditional names for the processes of change such as yin and yang and Wu Xing.

The I Ching is an influential text that is read throughout the world. Several sovereign states have employed I Ching hexagrams in their flags, and the text has provided inspiration to the worlds of religion, psychoanalysis, business, literature, and art.

The divination text: Zhou yi

The text of the I Ching has its origins in a Western Zhou divination text called the Changes of Zhou or Zhou yi (Chinese: 周易; pinyin: Zhōuyì).[3] The Zhou yi, which may be grounded in even older Shang dynasty analysis of oracle bones, contains references to events as early as the 11th century BC.[4] Based on a comparison of the language of the Zhou yi with dated bronze inscriptions, Edward Shaughnessy has concluded that the text was assembled in approximately its current form in the early decades of the reign of King Xuan of Zhou, i.e. the last quarter of the 9th century BC.[5] Recently discovered bamboo and wooden slips show that the Zhou yi was used throughout all levels of Chinese society in its current form by 300 BC, but still contained small variations as late as the Warring States period.[6] It is possible that other divination systems existed at this time; the Rites of Zhou name two other such systems, the Lianshan and the Guizang.[7]

Name and origins

The name Zhou yi means a book of "changes" (Chinese: 易; pinyin: Yì) used during the Zhou dynasty. The "changes" involved have been interpreted as the transformations of hexagrams, of their lines, or of the numbers obtained from the divination.[8] Feng Youlan proposed that the word for "changes" could also mean "easy", as in a form of divination easier than the oracle bones, but there is little evidence for this. There is also an ancient folk etymology that sees the character for "changes" as containing the sun and moon, the cycle of the day. Modern Sinologists believe the character to be derived either from an image of the sun emerging from clouds, or from the content of a vessel being changed into another.[9]

The Zhou yi is attributed to the legendary world ruler Fu Xi. According to the canonical Great Commentary, Fu Xi, who lived around 2800 BC, observed the patterns of the world and created the eight trigrams (Chinese: 八卦; pinyin: bāguà), "in order to become thoroughly conversant with the numinous and bright and to classify the myriad things." The Zhou yi itself does not contain this legend and indeed says nothing about its own origins.[10] The Rites of Zhou, however, confirms that the hexagrams of the Zhou yi were derived from an initial set of eight trigrams.[11] During the Han dynasty there were various opinions about the historical relationship between the trigrams and the hexagrams.[12] Eventually, a consensus formed around 2nd century AD scholar Ma Rong's attribution of the text to the joint work of Fu Xi, King Wen of Zhou, the Duke of Zhou, and Confucius, but this traditional attribution is no longer generally accepted.[13]

Structure

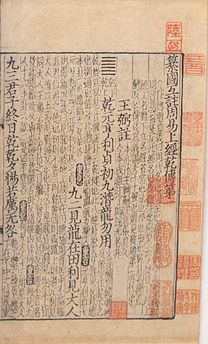

The basic unit of the Zhou yi is the hexagram (卦 guà), a figure composed of six stacked horizontal lines (爻 yáo). Each line is either broken or unbroken. The received text of the Zhou yi contains all 64 possible hexagrams, along with the hexagram's name (卦名 guàmíng), a short hexagram statement (彖 tuàn),[note 1] and six line statements (爻辭 yáocí).[note 2] The statements were used to determine the results of divination, but the reasons for having two different methods of reading the hexagram are not known, and it is not known why hexagram statements would be read over line statements or vice versa.[14] The book opens with the first hexagram statement, yuán hēng lì zhēn (元亨利貞). These four words, translated by James Legge as "originating and penetrating, advantageous and firm," are often repeated in the hexagram statements and were already considered an important part of I Ching interpretation in the 6th century BC.[15]

The names of the hexagrams are usually words that appear in their respective line statements, but in five cases (2, 9, 26, 61, and 63) an unrelated character of unclear purpose. The hexagram names could have been chosen arbitrarily from the line statements,[16] but it is also possible that the line statements were derived from the hexagram names.[17] The line statements, which make up most of the book, are exceedingly cryptic. Each line begins with a word indicating the line number, "base, 2, 3, 4, 5, top", and either the number 6 for a broken line, or the number 9 for a whole line. Hexagrams 1 and 2 have an extra line statement, named yong.[18] Following the line number, the line statements may fall into the categories of oracle, indication, prognostic or observation; each statement usually has two or three of these elements, and sometimes one or none.[19] Some line statements also contain poetry or references to historical events.[20]

Usage

Archaeological evidence shows that Zhou dynasty divination was grounded in cleromancy, the production of seemingly random numbers to determine divine intent.[21] The Zhou yi provided a guide to cleromancy that used the stalks of the yarrow plant, but it is not known how the yarrow stalks became numbers, or how specific lines were chosen from the line readings.[22] In the hexagrams, broken lines were used as shorthand for the numbers 6 (六) and 8 (八), and solid lines were shorthand for values of 7 (七) and 9 (九). The Great Commentary contains a late classic description of a process where various numerological operations are performed on a bundle of 50 stalks, leaving remainders of 6 to 9.[23] Like the Zhou yi itself, yarrow stalk divination dates to the Western Zhou period.[24]

The Zuo zhuan and Guoyu contain the oldest descriptions of divination using the Zhou yi. The two histories, considered generally reliable today, describe more than twenty successful divinations conducted by professional soothsayers for royal families between 671 BC and 487 BC. The method of divination is not explained, and none of the stories employ predetermined commentaries, patterns, or interpretations. Only the hexagrams and line statements are used.[25] By the 300s BC, the authority of the Zhou yi was also cited for rhetorical purposes, without relation to any stated divination.[26] The Zuo zhuan does not contain records of private individuals, but Qin dynasty records found at Shuihudi show that the hexagrams were privately consulted to answer questions such as business, health, children, and determining lucky days.[27]

In the Zuo zhuan stories, individual lines of hexagrams are denoted by using the genitive particle zhi, followed by the name of another hexagram where that specific line had another form. In later years, the word zhi was interpreted as a verb meaning "moving to", an apparent indication that hexagrams could be transformed into other hexagrams. However, there are no instances of "changeable lines" in the Zuo Zhuan. In all 12 out of 12 line divinations quoted, the original hexagrams are used to produce the oracle.[28]

The classic: I Ching

In 136 BC, Emperor Wu of Han named the Zhou yi "the first among the classics", dubbing it the Classic of Changes or I Ching. Emperor Wu's placement of the I Ching among the Five Classics was informed by a broad span of cultural influences that included Confucianism, Daoism, Legalism, yin-yang cosmology, and Wu Xing physical theory.[29] While the Zhou yi does not contain any cosmological analogies, the I Ching was read as a microcosm of the universe that offered complex, symbolic correspondences.[30] This edition of the text was literally set in stone, as one of the Xiping Stone Classics.[31] The canonized I Ching became the standard text for over two thousand years, until alternate versions of the Zhou yi and related texts were discovered in the 20th century.[32]

Ten Wings

Part of the canonization of the Zhou yi bound it to a set of ten commentaries called the Ten Wings. The Ten Wings are of a much later provenance than the Zhou yi, and are the production of a different society. The Zhou yi was written in Early Old Chinese, while the Ten Wings were written in a predecessor to Middle Chinese.[33] The specific origins of the Ten Wings are still a complete mystery to academics.[34] Regardless of their historical relation to the text, the philosophical depth of the Ten Wings made the I Ching a perfect fit to Han period Confucian scholarship.[35] The inclusion of the Ten Wings reflects a widespread recognition in ancient China, found in the Zuo zhuan and other pre-Han texts, that the I Ching was a rich moral and symbolic document useful for more than professional divination.[36]

Arguably the most important of the Ten Wings is the Great Commentary (Dazhuan) or Xi ci, which dates to roughly 300 BC.[note 3] The Great Commentary describes the I Ching as a microcosm of the universe and a symbolic description of the processes of change. By partaking in the spiritual experience of the I Ching, the Great Commentary states, the individual can understand the deeper patterns of the universe.[23] Among other subjects, it explains how the eight trigrams proceeded from the eternal oneness of the universe through three bifurcations.[37] The other Wings provide different perspectives on essentially the same viewpoint, giving ancient, cosmic authority to the I Ching.[38] For example, the Wen yan (文言) provides a moral interpretation that parallels the first two hexagrams, 乾 (qián) and 坤 (kūn), with Heaven and Earth.[39] Throughout the Ten Wings, there are passages that seem to purposefully increase the ambiguity of the base text, pointing to a recognition of multiple layers of symbolism.[40]

The Great Commentary associates knowledge of the I Ching with the ability to "delight in Heaven and understand fate;" the sage who reads it will see cosmological patterns and not despair in mere material difficulties.[41] The Japanese word for "metaphysics", keijijōgaku (形而上学; pinyin: xíng ér shàng xué) is derived from a statement found in the Great Commentary that "what is above form [xíng ér shàng] is called Dao; what is under form is called a tool".[42] The word has also been borrowed into Korean and re-borrowed back into Chinese.

The Ten Wings were traditionally attributed to Confucius, possibly based on a misreading of the Records of the Grand Historian.[43] While there is little evidence for this, the association of the I Ching with Confucius gave weight to the text and was taken as an article of faith throughout the Han and Tang dynasties.[44] The I Ching was not included in the burning of the Confucian classics, and textual evidence strongly suggests that Confucius did not consider the Zhou yi a "classic". An ancient commentary on the Zhou yi found at Mawangdui portrays Confucius as endorsing it as a source of wisdom first and an imperfect divination text second.[45]

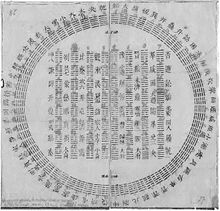

Hexagrams

In the canonical I Ching, the hexagrams are arranged in an order dubbed the King Wen sequence after King Wen of Zhou, who founded the Zhou dynasty and supposedly reformed the method of interpretation. The sequence generally pair hexagrams with their upside-down equivalents, although in eight cases hexagrams are paired with their inversion.[46] Another order, found at Mawangdui in 1973, arranges the hexagrams into eight groups sharing the same upper trigram. But the oldest known manuscript, found in 1987 and now held by the Shanghai Library, was almost certainly arranged in the King Wen sequence, and it has even been proposed that a pottery paddle from the Western Zhou period contains four hexagrams in the King Wen sequence.[47] Whichever of these arrangements is older, it is not evident that the order of the hexagrams was of interest to the original authors of the Zhou yi. The assignment of numbers, binary or decimal, to specific hexagrams is a modern invention.[48]

The following table numbers the hexagrams in King Wen order.

| 1 乾 (qián) |

2 坤 (kūn) |

3 屯 (zhūn) |

4 蒙 (méng) |

5 需 (xū) |

6 訟 (sòng) |

7 師 (shī) |

8 比 (bǐ) |

| 9 小畜 (xiǎo chù) |

10 履 (lǚ) |

11 泰 (tài) |

12 否 (pǐ) |

13 同人 (tóng rén) |

14 大有 (dà yǒu) |

15 謙 (qiān) |

16 豫 (yù) |

| 17 隨 (suí) |

18 蠱 (gŭ) |

19 臨 (lín) |

20 觀 (guān) |

21 噬嗑 (shì kè) |

22 賁 (bì) |

23 剝 (bō) |

24 復 (fù) |

| 25 無妄 (wú wàng) |

26 大畜 (dà chù) |

27 頤 (yí) |

28 大過 (dà guò) |

29 坎 (kǎn) |

30 離 (lí) |

31 咸 (xián) |

32 恆 (héng) |

| 33 遯 (dùn) |

34 大壯 (dà zhuàng) |

35 晉 (jìn) |

36 明夷 (míng yí) |

37 家人 (jiā rén) |

38 睽 (kuí) |

39 蹇 (jiǎn) |

40 解 (xiè) |

| 41 損 (sǔn) |

42 益 (yì) |

43 夬 (guài) |

44 姤 (gòu) |

45 萃 (cuì) |

46 升 (shēng) |

47 困 (kùn) |

48 井 (jǐng) |

| 49 革 (gé) |

50 鼎 (dǐng) |

51 震 (zhèn) |

52 艮 (gèn) |

53 漸 (jiàn) |

54 歸妹 (guī mèi) |

55 豐 (fēng) |

56 旅 (lǚ) |

| 57 巽 (xùn) |

58 兌 (duì) |

59 渙 (huàn) |

60 節 (jié) |

61 中孚 (zhōng fú) |

62 小過 (xiǎo guò) |

63 既濟 (jì jì) |

64 未濟 (wèi jì) |

Interpretation

Han and Six Dynasties

During the Han dynasty, I Ching interpretation divided into two schools, originating in a dispute over minor differences between older and newer editions of the received text.[49] New Text criticism, more egalitarian and eclectic, sought to find symbolic and numerological parallels between the natural world and the hexagrams. Their commentaries provided the basis of the School of Images and Numbers. Old Text criticism, more scholarly and hierarchical, focused on the moral content of the text, providing the basis for the School of Meanings and Principles.[50] The New Text scholars distributed alternate versions of the text and freely integrated non-canonical commentaries into their work, as well as propagating alternate systems of divination such as the Taixuanjing.[51] Most of this early commentary, such as the image and number work of Jing Fang, Yu Fan and Xun Shuang, is no longer extant.[52] Only short excerpts survive, from a Tang dynasty text called Zhou yi jijie.[53]

With the fall of the Han, I Ching scholarship was no longer organized into systematic schools. The most influential writer of this period was Wang Bi, who discarded the numerology of Han commentators and integrated the philosophy of the Ten Wings directly into the central text of the I Ching, creating such a persuasive narrative that Han commentators were no longer considered significant. A century later Han Kangbo added commentaries on the Ten Wings to Wang Bi's book, creating a text called the Zhouyi zhu. The principal rival interpretation was a practical text on divination by the soothsayer Guan Lu.[54]

Tang and Song dynasties

At the beginning of the Tang dynasty, Kong Yingda was tasked with creating a canonical edition of the I Ching. Choosing the third-century Zhouyi zhu as the official commentary, he added to it a subcommentary drawing out the subtler levels of Wang Bi's explanations. The resulting work, the Zhouyi zhengi, became the standard edition of the I Ching through the Song dynasty[55], in which there were two main approaches to I Ching studies. One was the yili xue (義理學, "principle study") approach, which was based on literalistic and moralistic principles. The other approach, taken by Shao Yong, was the xiangshu xue (象數學, "image-number study") approach, which was based on the much more iconographic and cosmological principles of the School of Naturalists.

By the 11th century, the I Ching was being read as a work of intricate philosophy, as a jumping-off point for examining great metaphysical questions and ethical issues.[56] Cheng Yi, patriarch of the Neo-Confucian Cheng-Zhu school, read the I Ching as a guide to moral perfection.[57]

The binary arrangement of hexagrams is associated with the famous Chinese scholar and philosopher Shao Yong in the 11th century.[58] He displayed it in two different formats, a circle, and a rectangular block. He clearly understood the sequence represented a logical progression of values and developed a method for arranging the hexagrams which can be interpreted as the sequence 0 to 63, as represented in binary, with yin as 0, yang as 1 and the least significant bit on top. The ordering has also been interpreted as the lexicographical order on sextuples of elements chosen from a two-element set.[59]

Neo-Confucian

Zhu Xi rejected both of the Han dynasty lines of commentary on the I Ching, proposing that the text was a work of divination, not philosophy. However, he still considered it useful for understanding the moral practices of the ancients, called "rectification of the mind" in the Great Learning. Zhu Xi's reconstruction of I Ching yarrow stalk divination, based in part on the Great Commentary account, became the standard form and is still in use today.[60]

As China entered the early modern period, the I Ching took on renewed relevance in both Confucian and Daoist study. The Kangxi Emperor was especially fond of the I Ching and ordered new interpretations of it.[61]

Korean and Japanese

In 1557, the Korean Yi Hwang produced one of the most influential I Ching studies of the early modern era, claiming that the spirit was a principle (li) and not a material force (qi). Hwang accused the Neo-Confucian school of having misread Zhu Xi. His critique proved influential not only in Korea but also in Japan.[62] Other than this contribution, the I Ching was not central to the development of Korean Confucianism, and by the 19th century, I Ching studies were integrated into the silhak reform movement. [63]

In medieval Japan, secret teachings on the I Ching were publicized by Rinzai Zen master Kokan Shiren and the Shintoist Yoshida Kanetomo.[64] I Ching studies in Japan took on new importance in the Edo period, during which over 1,000 books were published on the subject by over 400 authors. The majority of these books were serious works of philology, reconstructing ancient usages and commentaries for practical purposes. A sizable minority focused on numerology, symbolism, and divination.[65] During this time, over 150 editions of earlier Chinese commentaries were reprinted in Japan, including several texts that had become lost in China.[66] In the early Edo period, writers such as Itō Jinsai, Kumazawa Banzan, and Nakae Toju ranked the I Ching the greatest of the Confucian classics.[67] Many writers attempted to use the I Ching to explain Western science in a Japanese framework. One writer, Shizuki Tadao, even attempted to employ Newtonian mechanics and the Copernican principle within an I Ching cosmology.[68] This line of argument was later taken up in China by Zhang Zhidong.[69]

Early European

Leibniz, who was corresponding with Jesuits in China, wrote the first European commentary on the I Ching in 1703, arguing that it proved the universality of binary numbers and theism, since the broken lines, the "0" or "nothingness", cannot become solid lines, the "1" or "oneness", without the intervention of God.[70] This was criticized by Hegel, who proclaimed that binary system and Chinese characters were "empty forms" that could not articulate spoken words with the clarity of the Western alphabet.[71] In their discussion, I Ching hexagrams and Chinese characters were conflated into a single foreign idea, sparking a dialogue on Western philosophical questions such as universality and the nature of communication. In the 20th century, Jacques Derrida identified Hegel's argument as logocentric, but accepted without question Hegel's premise that the Chinese language cannot express philosophical ideas.[72]

Modern

After the Xinhai Revolution, the I Ching lost its canonical status in China, but it maintained cultural influence as China's most ancient text. Borrowing back from Leibniz, Chinese writers offered parallels between the I Ching and subjects such as linear algebra and logic in computer science, aiming to demonstrate that ancient Chinese cosmology had anticipated Western discoveries.[73] The psychologist Carl Jung took interest in the possible universal nature of the imagery of the I Ching, and he introduced an influential German translation by Richard Wilhelm by discussing his theories of archetypes and synchronicity.[74]

The modern period also brought a new level of skepticism and rigor to I Ching scholarship. Li Jingchi spent several decades producing a new interpretation of the text, which was published posthumously in 1978. Gao Heng, an expert in pre-Qin China, reinvestigated its use as a Zhou dynasty oracle. Edward Shaughnessy proposed a new dating for the various strata of the text.[75]

Divination

The I Ching remains a widely used divination text today. One quite common form is yarrow stalk divination, as described in China's most ancient histories, in the 300 BC Great Commentary, and later in the Huainanzi and the Lunheng. From the Great Commentary's description, the Neo-Confucian Zhu Xi reconstructed a method of yarrow stalk divination that is still used throughout the Far East. In the modern period, Gao Heng attempted his own reconstruction, which varies from Zhu Xi in places.[76]

Another divination method, employing coins, became widely used in the Tang dynasty and is still used today. In the modern period, alternative methods such as specialized dice and cartomancy have also appeared.[77]

Influence

The I Ching has influenced countless Chinese philosophers, artists and even businesspeople throughout history. In more recent times, several Western artists and thinkers have used it in fields as diverse as psychoanalysis, music, film, drama, dance, eschatology, and fiction writing.

Use in national flags

The Flag of South Korea contains the Taiji symbol, or tàijítú, (yin and yang in dynamic balance, called taegeuk in Korean), representing the origin of all things in the universe. The taegeuk is surrounded by four of the eight trigrams, starting from top left and going clockwise: Heaven, Water, Earth, Fire. In addition, the Republic of Korea Air Force aircraft roundel incorporates the Taiji in conjunction with the trigrams representing Heaven.

The flag of the Empire of Vietnam used the Li (Fire) trigram and was known as cờ quẻ Ly (Li trigram flag) because the trigram represents South. Its successor the Republic of Vietnam connected the middle lines, turning it into the Qián (Heaven) trigram. (see Flag of the Republic of Vietnam).

Translations

| Part of a series on |

| Taoism |

|---|

|

The I Ching has been translated into Western languages dozens of times, the most influential edition being the 1950 German translation of Richard Wilhelm.[78] The earliest complete published I Ching translation in a Western language was a Latin translation done in the 1730s by Jesuit missionary Jean-Baptiste Régis that was published in Germany in the 1830s.[79] Although Thomas McClatchie and James Legge had both translated the text in the 19th century, the text gained significant traction during the counterculture of the 1960s, with the translations of Wilhelm and John Blofeld attracting particular interest.[80] Richard Rutt's 1996 translation incorporated much of the new archaeological and philological discoveries of the 20th century, and it is considered the most accurate available in English. Gregory Whincup's 1986 translation also attempts to reconstruct Zhou period readings and is arguably easier to read.[81]

The following list encapsulates the most notable English translations.

- Blofeld, John (1965). The Book of Changes: A New Translation of the Ancient Chinese I Ching. New York: E. P. Dutton.

- Cleary, Thomas (2003). I ching : the book of change. Boston: Shambhala. ISBN 1-59030-015-7.

- A translation of Cheng Yi's influential Song period commentary

- Cornelius, J. Edward and Cornelius, Marlene (1998). Yî King: A Beastly Book of Changes, Red Flame: A Thelemic Research Journal, Issue 5.

- Contains commentary by Aleister Crowley

- Legge, James (1882). The Sacred Books of China, Part II: The Yî King.

- Lynn, Richard John (1994). The classic of changes. New York, NY: Columbia Univ. Press. ISBN 0-231-08294-0.

- Translation of Wang Bi's influential 3rd century commentary

- McClatchie, Thomas (1876). A Translation of the Confucian Yi-king. Shanghai: American Presbyterian Mission Press.

- Pearson, Margaret (2011). The Original I Ching: An Authentic Translation of the Book of Changes. Rutland, VT: Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8048-4181-8.

- A feminist translation, lacking the yin-yang cosmology of most Chinese commentaries

- Ritsema, Rudolf (1994). I Ching : the classic Chinese oracle of change : the divinatory texts with concordance. Ascona: Eranos Foundation. ISBN 1-85230-536-3.

- Rutt, Richard (1996). The book of changes (Zhouyi): a Bronze Age document. Richmond: Curzon. ISBN 0-7007-0467-1.

- Shaughnessy, Edward L. (1996). I Ching : the Classic of Changes. New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN 0-345-36243-8.

- First English translation of the Mawangdui texts (c. 200 BC)

- Whincup, Gregory (1986). Rediscovering the I Ching. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-19667-9.

- Wilhelm, Richard and Baynes, Cary (1967). The I Ching or Book of Changes, With foreword by Carl Jung. 3rd. ed., Bollingen Series XIX. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press (1st ed. 1950).

See also

- Ba gua

- Da Liu Ren

- Feng Shui

- Lingqijing

- Lo Shu Square

- Qi Men Dun Jia

- T'ai chi ch'uan

- Yellow River Map

- Yin and yang

Notes

- ^ The word tuan (彖) refers to a four-legged animal similar to a pig. It is not known why this word was used, and it is possible that it is a homonym for an unknown word. The modern word for a hexagram statement is guàcí (卦辭). (Rutt 1996, pp. 122–3) harv error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFRutt1996 (help)

- ^ Referred to as yao (繇) in the Zuo zhuan. (Nielsen 2003, pp. 24, 290)

- ^ The received text was rearranged by Zhu Xi. (Nielsen 2003, p. 258)

References

- Citations

- ^ "I Ching". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ^ Kern (2010), p. 17.

- ^ Marshall 2001, pp. 3–7; Smith 2012, p. 22; Nelson 2011, p. 377; Hon 2005, p. 2; Shaughnessy 1983, p. 105; Raphals 2013, p. 337; Nylan 2001, p. 220.

- ^ Marshall 2001, p. 50-66.

- ^ Shaughnessy 1983, p. 219; Rutt 1996, pp. 32–33 sfnm error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFRutt1996 (help); Smith 2012, p. 22; Knechtges 2014, p. 1885.

- ^ Shaughnessy 2014, passim; Smith 2012, p. 22.

- ^ Rutt 1996, p. 26-7 sfnm error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFRutt1996 (help); Redmond & Hon 2014, pp. 106–9; Shchutskii 1979, p. 98.

- ^ Knechtges 2014, p. 1877.

- ^ Shaughnessy 1983, p. 106; Marshall 2001, p. 12-5; Schuessler 2007, p. 566; Nylan 2001, pp. 229–230.

- ^ Redmond & Hon 2014, pp. 54–5.

- ^ Shaughnessy 2014, p. 144.

- ^ Nielsen 2003, p. 7.

- ^ Nielsen 2003, p. 249; Shchutskii 1979, p. 133.

- ^ Rutt 1996, pp. 122–5. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFRutt1996 (help)

- ^ Rutt 1996, pp. 126, 187–8 sfnm error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFRutt1996 (help); Shchutskii 1979, pp. 65–6.

- ^ Rutt 1996, p. 118 sfnm error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFRutt1996 (help); Shaughnessy 1983, p. 123.

- ^ Knechtges 2014, p. 1879.

- ^ Rutt 1996, pp. 129–30. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFRutt1996 (help)

- ^ Rutt 1996, p. 131. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFRutt1996 (help)

- ^ Knechtges 2014, pp. 1880–1.

- ^ Shaughnessy 2014, p. 14.

- ^ Smith 2012, p. 39.

- ^ a b Smith 2008, p. 27.

- ^ Raphals 2013, p. 129.

- ^ Rutt 1996, p. 173. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFRutt1996 (help)

- ^ Smith 2012, p. 43; Raphals 2013, p. 336.

- ^ Raphals 2013, pp. 203–212.

- ^ Shaughnessy 1983, p. 97; Rutt 1996, p. 154-5 sfnm error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFRutt1996 (help); Smith 2008, p. 26.

- ^ Smith 2008, p. 31-2.

- ^ Raphals 2013, p. 337.

- ^ Knechtges 2014, p. 1889.

- ^ Shaughnessy 2014, passim; Smith 2008, pp. 48–50.

- ^ Rutt 1996, p. 39. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFRutt1996 (help)

- ^ Shaughnessy 2014, p. 284.

- ^ Smith 2012, p. 48.

- ^ Nylan 2001, p. 229.

- ^ Nielsen 2003, p. 260.

- ^ Smith 2008, p. 48.

- ^ Knechtges 2014, p. 1882.

- ^ Nylan 2001, p. 221.

- ^ Nylan 2001, pp. 248–9.

- ^ Yuasa 2008, p. 51.

- ^ Peterson 1982, p. 73.

- ^ Smith 2008, p. 27; Nielsen 2003, pp. 138, 211.

- ^ Shchutskii 1979, p. 213; Smith 2012, p. 46.

- ^ Smith 2008, p. 37.

- ^ Shaughnessy 2014, pp. 52–3, 16–7.

- ^ Rutt 1996, pp. 114–8. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFRutt1996 (help)

- ^ Smith 2008, p. 58; Nylan 2001, p. 45.

- ^ Smith 2012, p. 76-8.

- ^ Smith 2008, pp. 76–9; Knechtges 2014, p. 1889.

- ^ Smith 2008, pp. 57, 67, 84–6.

- ^ Knechtges 2014, p. 1891.

- ^ Smith 2008, pp. 89–90, 98; Hon 2005, pp. 29–30; Knechtges 2014, p. 1890.

- ^ Hon 2005, pp. 29–33; Knechtges 2014, p. 1891.

- ^ Hon 2005, p. 144.

- ^ Smith 2008, p. 128.

- ^ Wang, Robin R.;Yinyang (Yin-yang); Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- ^ Ryan, James A. (January 1996). "Leibniz' Binary System and Shao Yong's "Yijing"". Philosophy East and West. 46 (1). University of Hawaii Press: 59–90. doi:10.2307/1399337. JSTOR 1399337.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Adler 2002, pp. v–xi; Smith 2008, p. 229.

- ^ Smith 2008, p. 177.

- ^ Ng 2000b, pp. 55–6.

- ^ Ng 2000b, p. 65.

- ^ Ng 2000a, p. 7, 15.

- ^ Ng 2000a, pp. 22–25.

- ^ Ng 2000a, pp. 28–9.

- ^ Ng 2000a, pp. 38–9.

- ^ Ng 2000a, pp. 143–5.

- ^ Smith 2008, p. 197.

- ^ Nelson 2011, p. 379; Smith 2008, p. 204.

- ^ Nelson 2011, p. 381.

- ^ Nelson 2011, p. 383.

- ^ Smith 2008, p. 205.

- ^ Smith 2008, p. 212.

- ^ Knechtges 2014, pp. 1884–5.

- ^ Smith 2008, p. 27; Raphals 2013, p. 167.

- ^ Redmond & Hon 2014, pp. 257.

- ^ Shaughnessy 2014, p. 1.

- ^ Shaughnessy (1993), p. 225.

- ^ Smith 2012, pp. 198–9.

- ^ Redmond & Hon 2014, pp. 241–3.

- Works cited

- Adler, Joseph A. (2002). Introduction to the study of the classic of change (I-hsüeh ch'i-meng). Provo, Utah: Global Scholarly Publications. ISBN 1-59267-334-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hon, Tze-ki 韓子奇 (2005). The Yijing and Chinese Politics: classical commentary and literati activism in the northern Song Period, 960 - 1127. Albany: State Univ. of New York Press. ISBN 0-7914-6311-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Loewe, Michael; Shaughnessy, Edward (1999). The Cambridge history of ancient China: from the origins of civilization to 221 B.C. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press. ISBN 0-521-47030-7.

- Kern, Martin (2010). "Early Chinese literature, Beginnings through Western Han". In Owen, Stephen (ed.). The Cambridge History of Chinese Literature, Volume 1: To 1375. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–115. ISBN 978-0-521-11677-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Knechtges, David R. (2014). "Yi jing 易經 (Classic of changes)". In Knechtges, David R.; Chang, Taiping (eds.). Ancient and Early Medieval Chinese Literature: A Reference Guide. Vol. 3. Leiden: Brill Academic Pub. pp. 1877–1896. ISBN 978-90-04-27216-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Nelson, Eric S. (2011). "The Yijing and Philosophy: From Leibniz to Derrida". Journal of Chinese Philosophy. 38 (3): 377–396. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6253.2011.01661.x.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Nielsen, Bent (2003). A Companion to Yi Jing Numerology and Cosmology : Chinese studies of images and numbers from Han (202 BCE - 220 BCE) to Song (960 - 1279 CE). London: RoutledgeCurzon. ISBN 0700716084.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ng, Wai-ming 吳偉明 (2000a). The I Ching in Tokugawa Thought and Culture. Honolulu, HI: Association for Asian Studies and University of Hawai'i Press. ISBN 0-8248-2242-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ng, Wai-ming (2000b). "The I Ching in Late-Choson Thought". Korean Studies. 24 (1): 53–68. doi:10.1353/ks.2000.0013.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|authormask=ignored (|author-mask=suggested) (help) - Nylan, Michael (2001). The Five "Confucian" Classics. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0300130333.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Peterson, Willard J. (1982). "Making Connections: 'Commentary on the Attached Verbalizations' of the Book of Change". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. 42: 67–116.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Raphals, Lisa (2013). Divination and Prediction in Early China and Ancient Greece. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press. ISBN 1-107-01075-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Redmond, Geoffrey; Hon, Tze-Ki (2014). Teaching the I Ching. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-976681-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Rutt, Richard (1996). The Book of Changes (Zhouyi): a Bronze Age Document. Richmond: Curzon. ISBN 0-7007-0467-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Shchutskii, Julian (1979). Researches on the I Ching. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press. ISBN 0-691-09939-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Schuessler, Axel (2007). ABC etymological dictionary of old Chinese. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press. ISBN 1-4356-6587-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Shaughnessy, Edward (1983). The composition of the Zhouyi (Thesis). Stanford University.

{{cite thesis}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Shaughnessy, Edward (1993). "I Ching 易經 (Chou I 周易)". In Loewe, Michael (ed.). Early Chinese Texts: A Bibliographical Guide. Society for the Study of Early China & Institute for East Asian Studies, University of California, Berkeley. pp. 216–228. ISBN 1-55729-043-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|authormask=ignored (|author-mask=suggested) (help) - Shaughnessy, Edward (2014). Unearthing the Changes: Recently Discovered Manuscripts of the Yi Jing (I Ching) and Related Texts. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-53330-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|authormask=ignored (|author-mask=suggested) (help) - Smith, Richard J. (2008). Fathoming the Cosmos and Ordering the World: the Yijing (I ching, or classic of changes) and its evolution in China. Charlottesville, Va.: University of Virginia Press. ISBN 0-8139-2705-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Smith, Richard J. (2012). The I Ching: a biography. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-14509-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|authormask=ignored (|author-mask=suggested) (help) - Yuasa, Yasuo (2008). Overcoming Modernity: synchronicity and image-thinking. Albany: State University of New York Press. ISBN 1-4356-5870-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

External links

- Yi Jing at the Chinese Text Project

- Template:Dmoz

- General bibliography (multilingual) of Western works on the Yijing