Hawaiian Kingdom

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2017) |

Hawaiian Kingdom Aupuni Mōʻī o Hawaiʻi | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1893–1895: Government-in-exile | |||||||||||||

Motto:

| |||||||||||||

Anthem:

| |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Capital | |||||||||||||

| Common languages | Hawaiian, English | ||||||||||||

| Religion | Church of Hawaii | ||||||||||||

| Government | Absolute monarchy (until 1840) Constitutional monarchy (from 1840) | ||||||||||||

| Monarch | |||||||||||||

• 1795–1819 (first) | Kamehameha I | ||||||||||||

• 1891–1893 (last) | Liliʻuokalani | ||||||||||||

| Kuhina Nui | |||||||||||||

• 1819–1832 (first) | Kaʻahumanu | ||||||||||||

• 1863–1864 (last) | Kekūanāoʻa | ||||||||||||

| Legislature | Legislature | ||||||||||||

| House of Nobles | |||||||||||||

| House of Representatives | |||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||

• Inception | May, 1795 | ||||||||||||

| March/April 1810[10] | |||||||||||||

| October 8, 1840 | |||||||||||||

| February 25 – July 31, 1843 | |||||||||||||

| November 28, 1843 | |||||||||||||

| January 17, 1893 | |||||||||||||

• Abdication of Queen Liliʻuokalani | January 24, 1895 | ||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||

• 1780 | 400,000 – 800,000 | ||||||||||||

• 1800 | 250,000 | ||||||||||||

• 1832 | 130,313 | ||||||||||||

• 1890 | 89,990 | ||||||||||||

| Currency | |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||||

| Part of a series on the |

| Hawaiian sovereignty movement |

|---|

|

| Main issues |

| Governments |

| Historical conflicts |

| Modern events |

| Parties and organizations |

| Documents and ideas |

| Books |

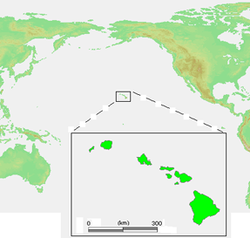

The Hawaiian Kingdom, or Kingdom of Hawaiʻi, originated in 1795, when the warrior chief Kamehameha the Great, of the independent island of Hawaiʻi, conquered the independent islands of Oʻahu, Maui, Molokaʻi, and Lānaʻi and unified them under one government. In 1810, the whole Hawaiian archipelago became unified when Kauaʻi and Niʻihau joined the Hawaiian Kingdom voluntarily. Two major dynastic families ruled the kingdom: the House of Kamehameha and the House of Kalākaua.

The kingdom won recognition from major European powers. The United States became its chief trading partner and watched over it to prevent some other power (such as Britain or Japan) from threatening to seize control. Hawaiʻi was forced to adopt a new constitution in 1887 when King Kalākaua was threatened with violence by the Honolulu Rifles, an anti-monarchist militia, to sign it. Queen Liliʻuokalani, who succeeded Kalākaua in 1891, tried to abrogate the 1887 constitution and promulgate a new constitution but was overthrown in 1893, largely at the hands of the Committee of Safety, a group of residents consisting of Hawaiian subjects and foreign nationals of American, British, and German descent, many of whom had been educated in the US, had lived there for a time, and identified strongly as American.[12] Hawaiʻi became a republic until the US annexed it by the Newlands Resolution, a joint resolution, which was passed on July 4, 1898 by the US Congress and created the Territory of Hawaii. United States Public Law 103-150 adopted in 1993, (informally known as the Apology Resolution), acknowledged that "the overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii occurred with the active participation of agents and citizens of the United States" and also "that the Native Hawaiian people never directly relinquished to the United States their claims to their inherent sovereignty as a people over their national lands, either through the Kingdom of Hawaii or through a plebiscite or referendum." [13]

Origins

In ancient Hawaiʻi, society was divided into multiple classes. At the top of the class system was the aliʻi class[14] with each island ruled by a separate aliʻi nui.[15] All of these rulers were believed to come from a hereditary line descended from the first Polynesian, Papa, who would become the earth mother goddess of the Hawaiian religion.[16] Captain James Cook became the first European to encounter the Hawaiian Islands, on his third voyage (1776–1780) in the Pacific. He was killed at Kealakekua Bay on the island of Hawaiʻi in 1779 in a dispute over the taking of a longboat. Three years later the Island of Hawaiʻi was passed[by whom?] to Kalaniʻōpuʻu's son, Kīwalaʻō, while religious authority was passed to the ruler's nephew, Kamehameha.

The warrior chief who became Kamehameha the Great conducted a series of battles, lasting 15 years. He established the Hawaiian Kingdom in 1795 with the help of western weapons and advisors, such as John Young and Isaac Davis.[17] Although successful in attacking both Oʻahu and Maui, he [who?] failed to secure a victory in Kauaʻi, his effort hampered by a storm and a plague that decimated his army. Eventually, Kauaʻi's chief swore allegiance to Kamehameha (1810). The unification ended the ancient Hawaiian society, transforming it into an independent constitutional monarchy crafted in the traditions and manner of European monarchs. The Kingdom of Hawaiʻi thus became an early example of the establishment of monarchies in Polynesian societies as contacts with Europeans increased.[18][19] Similar political developments occurred (for example) in Tahiti, Tonga, and New Zealand.

Kamehameha dynasty (1795–1874)

From 1810 to 1893 two major dynastic families ruled the Hawaiian Kingdom: the House of Kamehameha (to 1874) and the Kalākaua Dynasty (1874–1893). Five members of the Kamehameha family led the government, each styled as Kamehameha, until 1872. Lunalilo (r. 1873–1874) was also a member of the House of Kamehameha through his mother. Liholiho (Kamehameha II, r. 1819–1824) and Kauikeaouli (Kamehameha III, r. 1825–1854) were direct sons of Kamehameha the Great.

During Liholiho's and Kauikeaouli's reigns, the primary wife of Kamehameha the Great, Queen Kaʻahumanu, ruled as Queen Regent and Kuhina Nui, or Prime Minister.

Economic, social, and cultural transformation

| Part of a series on the |

| History of Hawaii |

|---|

| Topics |

Economic and demographic factors in the 19th century reshaped the islands. Their consolidation into one unified political entity led to international trade. Under Kamehameha (1795–1819), sandalwood was exported to China. That led to the introduction of money and trade throughout the islands.

Following Kamehameha's death the succession was overseen by his principal wife, Kaʻahumanu, who was designated as regent over the new king, Liholiho, who was a minor.

Queen Kaʻahumanu eliminated various prohibitions (kapu) governing women's behavior. They included men and women eating together and women eating bananas. She also overturned the old religion as the Christian missionaries arrived in the islands. A major contribution of the missionaries was to develop a written Hawaiian language. That led to very high levels of literacy in Hawaiʻi, above 90 percent in the latter half of the 19th century. The development of writing aided in the consolidation of government. Written constitutions enumerating the power and duties of the King were developed.

In 1848, the Great Māhele was promulgated by King Kamehameha III.[20] It instituted formal property rights to the land and followed the customary control of the land prior to this declaration. Ninety-eight percent of the land was assigned to the aliʻi, chiefs or nobles. Two percent went to the commoners. No land could be sold, only transferred to lineal descendant land manager. For the natives, contact with the outer world represented demographic disaster, as a series of unfamiliar diseases such as smallpox decimated the natives. The Hawaiian population of natives fell from approximately 128,000 in 1778[21] to 71,000 in 1853 and kept declining to 24,000 in 1920. Most lived in remote villages.[22]

American missionaries converted most of the natives to Christianity. The missionaries and their children became a powerful elite into the mid-19th century. They provided the chief advisors and cabinet members of the kings and dominated the professional and merchant class in the cities.[23]

The elites promoted the sugar industry in order to modernize Hawaiʻi's economy. American capital set up a series of plantations after 1850.[24] Few natives were willing to work on the sugar plantations and so recruiters fanned out across Asia and Europe. As a result, between 1850 and 1900 some 200,000 contract laborers from China, Japan, the Philippines, Portugal and elsewhere came to Hawaiʻi under fixed term contracts (typically for five years). Most returned home on schedule, but large numbers stayed permanently. By 1908 about 180,000 Japanese workers had arrived. No more were allowed in, but 54,000 remained permanently.[25]

Military

The Hawaiian army and navy developed from the warriors of Kona under Kamehameha I, who unified Hawaiʻi in 1810. The army and navy used both traditional canoes and uniforms including helmets made of natural materials and loincloths (called the Malo) as well as western technology like artillery cannons, muskets, and European ships.[citation needed] European advisors were captured, treated well and became Hawaiian citizens.[clarification needed] When Kamehameha died in 1819 he left his son Liholiho a large arsenal with tens of thousands of soldiers and many warships. This helped put down the revolt at Kuamoʻo later in 1819 and Humehume's rebellion on Kauaʻi in 1824.

During the Kamehameha dynasty the population in Hawaiʻi was ravaged by epidemics following the arrival of outsiders. The military shrank with the population, so by the end of the Dynasty there was no Hawaiian navy and only an army, consisting of several hundred troops. After a French invasion that sacked Honolulu in 1849, Kamehameha III sought defense treaties with the United States and Britain. During the outbreak of the Crimean War in Europe, Kamehameha III declared Hawaiʻi a neutral state.[26] The United States government put strong pressure on Kamehameha IV to trade exclusively with the United States, even threatening to annex the islands. To counterbalance this situation Kamehameha IV and Kamehameha V pushed for alliances with other foreign powers, especially Great Britain. Hawaiʻi claimed uninhabited islands in the Pacific, including the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, many of which came into conflict with American claims.

Following the Kamehameha dynasty the royal guards were disbanded under Lunalilo after a barracks revolt in September 1873. A small army was restored under King Kalākaua but failed to stop the 1887 Rebellion by the Missionary Party. In 1891, Queen Liliʻuokalani came to power. The elections of 1892 were followed with petitions and requests from her administration to change the constitution of 1887. The US maintained a policy of keeping at least one cruiser in Hawaiʻi at all times. On January 17, 1893, Liliʻuokalani, believing the US military would intervene if she changed the constitution, waited for the USS Boston to leave port. Once it was known that Liliʻuokalani was revising the constitution, the Boston was recalled and assisted the Missionary Party in her overthrow. Following the overthrow and the establishment of the Provisional Government of Hawaii, the Kingdom's military was disarmed and disbanded. One hundred years later, in 1993, the U.S. Congress passed the Apology Resolution, admitting wrongdoing and issuing a belated apology.

French Incident (1839)

Under the rule of Queen Kaʻahumanu, the powerful, newly converted Protestant widow of Kamehameha the Great, Catholicism was illegal in Hawaiʻi, and in 1831 French Catholic priests were forcibly deported by chiefs loyal to her. Native Hawaiian converts to Catholicism claimed to have been imprisoned, beaten and tortured after the expulsion of the priests.[27] Resistance toward the French Catholic missionaries remained the same under the reign of her successor, the Kuhina Nui Kaʻahumanu II.

In 1839 Captain Laplace of the French frigate Artémise sailed to Hawaiʻi under orders to:

- Destroy the malevolent impression which you find established to the detriment of the French name; to rectify the erroneous opinion which has been created as to the power of France; and to make it well understood that it would be to the advantage of the chiefs of those islands of the Ocean to conduct themselves in such a manner as not to incur the wrath of France. You will exact, if necessary with all the force that is yours to use, complete reparation for the wrongs which have been committed, and you will not quit those places until you have left in all minds a solid and lasting impression.

Under the threat of war, King Kamehameha III signed the Edict of Toleration on July 17, 1839 and paid the $20,000 in compensation for the deportation of the priests and the incarceration and torture of converts, agreeing to Laplace's demands. The kingdom proclaimed:

- That the Catholic worship be declared free, throughout all the dominions subject to the King of the Sandwich Islands; the members of this religious faith shall enjoy in them the privileges granted to Protestants.

The Roman Catholic Diocese of Honolulu returned unpersecuted and as reparation Kamehameha III donated land for them to build a church upon.

Paulet Affair (1843)

An even more serious threat occurred on February 13, 1843. Lord George Paulet of the Royal Navy warship HMS Carysfort, entered Honolulu Harbor and demanded that King Kamehameha III cede the islands to the British Crown.[28] Under the guns of the frigate, Kamehameha III surrendered to Paulet on February 25, writing to his people:

"Where are you, chiefs, people, and commons from my ancestors, and people from foreign lands?

Hear ye! I make known to you that I am in perplexity by reason of difficulties into which I have been brought without cause, therefore I have given away the life of our land. Hear ye! but my rule over you, my people, and your privileges will continue, for I have hope that the life of the land will be restored when my conduct is justified.

Done at Honolulu, Oahu, this 25th day of February, 1843.

Kamehameha III

Kekauluohi"[29]

Gerrit P. Judd, a missionary who had become the minister of finance for the Kingdom, secretly arranged for J.F.B. Marshall to be sent to the United States, France and Britain, to protest Paulet's actions.[30] Marshall, a commercial agent of Ladd & Co., conveyed the Kingdom's complaint to the vice consul of Britain in Tepec. Rear Admiral Richard Darton Thomas, Paulet's commanding officer, arrived at Honolulu harbor on July 26, 1843 on HMS Dublin from Valparaíso, Chile. Admiral Thomas apologized to Kamehameha III for Paulet's actions, and restored Hawaiian sovereignty on July 31, 1843. In his restoration speech, Kamehameha III declared that "Ua Mau ke Ea o ka ʻĀina i ka Pono" (The life of the land is perpetuated in righteousness), the motto of the future State of Hawaii. The day was celebrated as Lā Hoʻihoʻi Ea (Sovereignty Restoration Day).

French invasion (1849)

In August 1849, French admiral Louis Tromelin arrived in Honolulu Harbor with the La Poursuivante and Gassendi. De Tromelin made ten demands to King Kamehameha III on August 22, mainly demanding that full religious rights be given to Catholics, (a decade earlier, during the French Incident the ban on Catholicism had been lifted, but Catholics still enjoyed only partial religious rights). On August 25 the demands had not been met. After a second warning was made to the civilians, French troops overwhelmed the skeleton force and captured Honolulu Fort, spiked the coastal guns and destroyed all other weapons they found (mainly muskets and ammunition). They raided government buildings and general property in Honolulu, causing damage that amounted to $100,000. After the raids the invasion force withdrew to the fort. De Tromelin eventually recalled his men and left Hawaiʻi on September 5.

Foreign relations

Anticipating foreign encroachment on Hawaiian territory, King Kamehameha III dispatched a delegation to the United States and Europe to secure the recognition of Hawaiian independence. Timoteo Haʻalilio, William Richards and Sir George Simpson were commissioned as joint ministers plenipotentiary on April 8, 1842. Simpson left for Great Britain while Haʻalilio and Richards to the United States on July 8, 1842. The Hawaiian delegation secured the assurance of US president John Tyler on December 19, 1842 of Hawaiian independence and then met Simpson in Europe to secure formal recognition by the United Kingdom and France. On March 17, 1843, King Louis-Philippe of France recognized Hawaiian independence at the urging of King Leopold I of Belgium. On April 1, 1843, Lord Aberdeen, on behalf of Queen Victoria, assured the Hawaiian delegation, "Her Majesty's Government was willing and had determined to recognize the independence of the Sandwich Islands under their present sovereign."

Anglo-Franco Proclamation

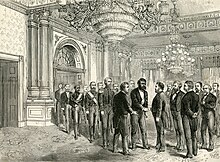

On November 28, 1843, at the Court of London, the British and French governments formally recognized Hawaiian independence. The "Anglo-Franco Proclamation", a joint declaration by France and Britain, signed by King Louis-Philippe and Queen Victoria, assured the Hawaiian delegation:

Her Majesty the Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and His Majesty the King of the French, taking into consideration the existence in the Sandwich Islands (Hawaiian Islands) of a government capable of providing for the regularity of its relations with foreign nations, have thought it right to engage, reciprocally, to consider the Sandwich Islands as an Independent State, and never to take possession, neither directly or under the title of Protectorate, or under any other form, of any part of the territory of which they are composed.

The undersigned, Her Majesty's Principal Secretary of State of Foreign Affairs, and the Ambassador Extraordinary of His Majesty the King of the French, at the Court of London, being furnished with the necessary powers, hereby declare, in consequence, that their said Majesties take reciprocally that engagement.

In witness whereof the undersigned have signed the present declaration, and have affixed thereto the seal of their arms.

Done in duplicate at London, the 28th day of November, in the year of our Lord, 1843.

" 'ABERDEEN. [L.S.]

" 'ST. AULAIRE. [L.S.],[31]

Hawaiʻi was the first non-European indigenous state whose independence was recognised by the major powers.[32] The United States declined to join with France and the United Kingdom in this statement. Even though President John Tyler had verbally recognized Hawaiian independence, it was not until 1849 that the United States did formally.[31]

November 28, Lā Kūʻokoʻa (Independence Day), became a national holiday to celebrate the recognition of Hawaiʻi's independence. The Hawaiian Kingdom entered into treaties with most major countries and established over 90 legations and consulates.[32]

Princes and chiefs who were eligible to be rulers

In 1839, King Kamehameha III created the Chief's Children's School (Royal School) and selected of the 16 highest ranking aliʻi to be eligible to rule and befitted them with the highest education and proper etiquette. They were required to board under the direction of Amos Starr Cooke and his wife. The princes and chiefs eligible to be rulers were: Moses Kekūāiwa, Alexander Liholiho, Lot Kamehameha, Victoria Kamāmalu, Emma Rooke, William Lunalilo, David Kalākaua, Lydia Kamakaʻeha, Bernice Pauahi, Elizabeth Kekaʻaniau, Jane Loeau, Abigail Maheha, Peter Young Kaeo, James Kaliokalani, John Pitt Kīnaʻu and Mary Paʻaʻāina, officially declared by King Kamehameha III in 1844.[1]

Succession crisis and monarchial elections

Dynastic rule by the Kamehameha family ended in 1872 with the death of Kamehameha V. Upon his deathbed, he summoned High Chiefess Bernice Pauahi Bishop to declare his intentions of making her heir to the throne. Bernice refused the crown, and Kamehameha V died without naming an heir.

The refusal of Bishop to take the crown forced the legislature of the kingdom to elect a new monarch. From 1872 to 1873, several relatives of the Kamehameha line were nominated. In a ceremonial popular vote and a unanimous legislative vote, William C. Lunalilo, grandnephew of Kamehameha I, became Hawaiʻi's first of two elected monarchs but reigned only from 1873 to 1874 because of his early death due to tuberculosis at the age of 39.

Kalākaua dynasty

Like his predecessor, Lunalilo failed to name an heir to the throne. Once again, the legislature of the Hawaiian Kingdom needed an election to fill the royal vacancy. Queen Emma, widow of Kamehameha IV, was nominated along with David Kalākaua. The 1874 election was a nasty political campaign in which both candidates resorted to mudslinging and innuendo. David Kalākaua became the second elected King of Hawaiʻi but without the ceremonial popular vote of Lunalilo. The choice of the legislature was controversial, and U.S. and British troops were called upon to suppress rioting by Queen Emma's supporters, the Emmaites.

Kalākaua officially proclaimed his sister, Liliʻuokalani, would succeed to the throne upon his death. Hoping to avoid uncertainty in the monarchy's future, Kalākaua had named a line of succession in his will, so that after Liliʻuokalani the throne should succeed to Princess Victoria Kaʻiulani, then to Queen Consort Kapiʻolani, followed by her sister, Princess Poʻomaikelani, then Prince David Laʻamea Kawānanakoa and last was Prince Jonah Kūhiō Kalanianaʻole.[33] Although, the will was not an official line of succession or a proper proclamation according to kingdom law. There were also protests about nominating lower ranking aliʻi after Kaʻiulani who were not eligible to the throne while there were still high ranking aliʻi who were eligible,[34] such as High Chiefess Elizabeth Kekaʻaniau.[35] However, it was now the royal prerogative of Queen Liliʻuokalani and she officially proclaimed her niece Princess Kaʻiulani as heir to the throne.[36] She then later proposed a new constitution adding Prince David Kawānanakoa and Prince Jonah Kūhiō Kalanianaʻole, according to the wishes of Kalākaua, but it was never approved or ratified by the legislature.[citation needed]

Kalākaua's prime minister Walter M. Gibson indulged the expenses of Kalākaua and attempted a Polynesian confederation sending the "homemade battleship" Kaimiloa to Samoa in 1887. It resulted in suspicions from the German Navy and embarrassment for the conduct of the crew.[37]

Bayonet Constitution

In 1887, a constitution was drafted by Lorrin A. Thurston, Minister of Interior under King Kalākaua. The constitution was proclaimed by the king after a meeting of 3,000 residents including an armed militia demanded he sign it or be deposed. The document created a constitutional monarchy like the one that existed in United Kingdom, stripping the King of most of his personal authority and empowering the legislature and establishing cabinet government. It has since become widely known as the "Bayonet Constitution" because of the threat of force used to gain Kalākaua's cooperation.

The 1887 constitution empowered the citizenry to elect members of the House of Nobles (who had previously been appointed by the King). It increased the value of property a citizen must own to be eligible to vote above the previous Constitution of 1864 and denied voting rights to Asians who comprised a large proportion of the population (a few Japanese and some Chinese had previously become naturalized and now lost voting rights they had previously enjoyed). This guaranteed a voting monopoly to wealthy native Hawaiians and Europeans. The Bayonet Constitution continued allowing the monarch to appoint cabinet ministers, but stripped him of the power to dismiss them without approval from the Legislature.

Liliʻuokalani's Constitution

In 1891, Kalākaua died and his sister Liliʻuokalani assumed the throne. She came to power during an economic crisis precipitated in part by the McKinley Tariff. By rescinding the Reciprocity Treaty of 1875, the new tariff eliminated the previous advantage Hawaiian exporters enjoyed in trade to U.S. markets. Many Hawaiian businesses and citizens were feeling the pressures of the loss of revenue, so Liliʻuokalani proposed a lottery and opium licensing to bring in additional revenue for the government. Her ministers and closest friends tried to dissuade her from pursuing the bills, and these controversial proposals were used against her in the looming constitutional crisis.

Liliʻuokalani wanted to restore power to the monarch by abrogating the 1887 Constitution. The queen launched a campaign resulting in a petition to proclaim a new Constitution. Many citizens and residents who in 1887 had forced Kalākaua to sign the "Bayonet Constitution" became alarmed when three of her recently appointed cabinet members informed them that the queen was planning to unilaterally proclaim her new Constitution.[38] Some cabinet ministers were reported to have feared for their safety after upsetting the queen by not supporting her plans.[39]

Overthrow

In 1893, local businessmen and politicians, composed of six non-native Hawaiian Kingdom subjects, five American nationals, one British national, and one German national,[41] all of whom were living and doing business in Hawaiʻi, overthrew the queen, her cabinet and her marshal, and took over the government of the Hawaiian Kingdom.

Historians suggest that businessmen were in favor of overthrow and annexation to the U.S. in order to benefit from more favorable trade conditions with its main export market.[42][43][44][45] The McKinley Tariff of 1890 eliminated the previously highly favorable trade terms for Hawaiʻi's sugar exports, a main component of the economy.

United States Government Minister John L. Stevens summoned a company of uniformed U.S. Marines from the USS Boston and two companies of U.S. sailors to land on the Kingdom and take up positions at the U.S. Legation, Consulate, and Arion Hall on the afternoon of January 16, 1893. This deployment was at the request of the Committee of Safety, which claimed an "imminent threat to American lives and property." Stevens was accused of ordering the landing on his own authority and inappropriately using his discretion. Historian William Russ concluded that "the injunction to prevent fighting of any kind made it impossible for the monarchy to protect itself."[46]: 350

1895 rebellion

On July 17, 1893, Sanford B. Dole and his committee took control of the government and declared itself the Provisional Government of Hawaii "to rule until annexation by the United States" and lobbied the United States for it.[46]: 90 Dole was president of both the Provisional Government and the later Republic of Hawaii. During this time, members of the former government lobbied in Washington D.C. for the United States to restore the Hawaiian Kingdom. President Grover Cleveland considered the overthrow to have been an illegal act of war; he refused to consider annexation of the islands and initially worked to restore the queen to her throne. Between December 14, 1893 and January 11, 1894 a standoff occurred between the United States, Japan, and the United Kingdom against the Provisional Government to pressure them into returning the Queen known as the Black Week. This incident drove home the message that President Cleveland wanted Queen Liliʻuokalani's return to power, and so on July 4, 1894 the Republic of Hawaii was requested to wait for President Cleveland's second term to finish. As lobbying continued in Washington during 1894, the royalist faction was secretly amassing an army of 600 strong led by former Captain of the Guard Samuel Nowlein. In 1895 they attempted a counter-rebellion, and Liliʻuokalani was arrested when a weapons cache was found on the palace grounds. She was tried by a military tribunal of the Republic, convicted of treason, and placed under permanent house arrest in her own home.

On January 24, 1895 while under house arrest Liliʻuokalani was forced to sign a five-page declaration as "Liliuokalani Dominis" in which she formally abdicated the throne in return for the release and commutation of the death sentences of her jailed supporters, including Minister Joseph Nāwahī, Prince Kawānanakoa, Robert Wilcox, and Prince Jonah Kūhiō:

Before ascending the throne, for fourteen years, or since the date of my proclamation as heir apparent, my official title had been simply Liliuokalani. Thus I was proclaimed both Princess Royal and Queen. Thus it is recorded in the archives of the government to this day. The Provisional Government nor any other had enacted any change in my name. All my official acts, as well as my private letters, were issued over the signature of Liliuokalani. But when my jailers required me to sign ("Liliuokalani Dominis,") I did as they commanded. Their motive in this as in other actions was plainly to humiliate me before my people and before the world. I saw in a moment, what they did not, that, even were I not complying under the most severe and exacting duress, by this demand they had overreached themselves. There is not, and never was, within the range of my knowledge, any such a person as Liliuokalani Dominis.

— Queen Liliuokalani, "Hawaii's Story By Hawaii's Queen"[47]

Territorial extent

The Kingdom came about in 1795 in the aftermath of the Battle of Nuʻuanu with the conquest of Maui, Molokaʻi and Oʻahu. Kamehameha I had conquered Maui and Molokaʻi five years prior in the Battle of Kepaniwai, but they were abandoned when Kamehameha's Big Island possession was under threat and later reconquered by the aged King Kahekili II of Maui. His domain comprised six of the major islands of the Hawaiian chain, and with Kaumualiʻi's peaceful surrender, Kauaʻi and Niʻihau were added to his territories. Kamehameha II assumed de facto control of Kauaʻi and Niʻihau when he kidnapped Kaumualiʻi, ending his vassal rule over the islands.

In 1822, Queen Kaʻahumanu and her husband King Kaumualiʻi traveled with Captain William Sumner to find Nīhoa, as her generation had only known the island through songs and myths. Later, King Kamehameha IV sailed there to officially annex the island. Kamehameha IV and Kalākaua would later claim other islands in the Hawaiian Archipelago, including Pearl and Hermes Atoll, Necker Island, Laysan, Lisianski Island, Ocean (Kure) Atoll, Midway Atoll, French Frigate Shoals, Maro Reef and Gardner Pinnacles, as well as Palmyra Atoll, Johnston Atoll and Jarvis Island.[citation needed] Several of these islands had previously been claimed by the United States under the Guano Islands Act of 1856. The Stewart Islands, or Sikaiana Atoll, near the Solomon Islands, were ceded to Hawaiʻi in 1856 by its residents, but the cession was never formalized by the Hawaiian government.

Royal estates

Early in its history, the Hawaiian Kingdom was governed from several locations including coastal towns on the islands of Hawaiʻi and Maui (Lāhainā). It wasn't until the reign of Kamehameha III that a capital was established in Honolulu on the Island of Oʻahu.

By the time Kamehameha V was king, he saw the need to build a royal palace fitting of the Hawaiian Kingdom's new found prosperity and standing with the royals of other nations. He commissioned the building of the palace at Aliʻiōlani Hale. He died before it was completed. Today, the palace houses the Supreme Court of the State of Hawaiʻi.

David Kalākaua shared the dream of Kamehameha V to build a palace, and eagerly desired the trappings of European royalty. He commissioned the construction of ʻIolani Palace. In later years, the palace would become his sister's makeshift prison under guard by the forces of the Republic of Hawaii, the site of the official raising of the U.S. flag during annexation, and then territorial governor's and legislature's offices. It is now a museum.

Palaces and royal grounds

See also

- Cabinet of the Hawaiian Kingdom

- Hawaiian sovereignty movement

- Hawaii–Tahiti relations

- Legal status of Hawaii

- List of bilateral treaties signed by the Hawaiian Kingdom

- List of missionaries to Hawaii

- Privy Council of the Hawaiian Kingdom

- Supreme Court of Hawaii

- United States federal recognition of Native Hawaiians

References

- ^ Kanahele, George S. (1995). "Kamehameha's First Capital". Waikiki, 100 B.C. to 1900 A.D.: An Untold Story. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 90–102. ISBN 978-0-8248-1790-9.

- ^ FAP-30 (Honoapiilani Highway) Realignment, Puamana to Honokowai, Lahaina District, Maui County: Environmental Impact Statement. 1991. p. 14.

- ^ Trudy Ring; Noelle Watson; Paul Schellinger (November 5, 2013). The Americas: International Dictionary of Historic Places. Routledge. p. 315. ISBN 978-1-134-25930-4.

- ^ Patrick Vinton Kirch; Thérèse I. Babineau (1996). Legacy of the landscape: an illustrated guide to Hawaiian archaeological sites. University of Hawaii Press. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-8248-1816-6.

- ^ Patricia Schultz (2007). 1,000 Places to See in the USA and Canada Before You Die. Workman Pub. p. 932. ISBN 978-0-7611-4738-1.

- ^ Bryan Fryklund (January 4, 2011). Hawaii: The Big Island. Hunter Publishing, Inc. p. 81. ISBN 978-1-58843-637-5.

- ^ Benjamin F. Shearer (2004). The Uniting States: Alabama to Kentucky. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 296. ISBN 978-0-313-33105-3.

- ^ Roman Adrian Cybriwsky (May 23, 2013). Capital Cities around the World: An Encyclopedia of Geography, History, and Culture: An Encyclopedia of Geography, History, and Culture. ABC-CLIO. p. 352. ISBN 978-1-61069-248-9.

- ^ Engineering Magazine. Engineering Magazine Company. 1892. p. 286.

- ^ Kuykendall, Ralph Simpson (1965) [1938]. The Hawaiian Kingdom 1778–1854, Foundation and Transformation. Vol. 1. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. p. 51. ISBN 0-87022-431-X.

- ^ Spencer, Thomas P. (1895). Kaua Kuloko 1895. Honolulu: Papapai Mahu Press Publishing Company. OCLC 19662315.

- ^ Schulz, Joy (2017). Hawaiian by Birth: Missionary Children, Bicultural Identity, and U.S. Colonialism in the Pacific. University of Nebraska Press. pp. 1–238. ISBN 0803285892.

- ^ https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Public_Law_103-150

- ^ George Hu'eu Kanahele (January 1, 1993). K_ Kanaka, Stand Tall: A Search for Hawaiian Values. University of Hawaii Press. p. 399. ISBN 978-0-8248-1500-4.

- ^ E.S. Craighill Handy; Davis (December 21, 2012). Ancient Hawaiian Civilization: A Series of Lectures Delivered at THE KAMEHAMEHA SCHOOLS. Tuttle Publishing. p. 77. ISBN 978-1-4629-0438-9.

- ^ Frederick B. Wichman (January 2003). N_ Pua Aliì O Kauaì: Ruling Chiefs of Kauaì. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-2638-3.

- ^ Lawrence, Mary S. (1912). Old Time Hawaiians and Their Works. Gin and Company. p. 127. ISBN 978-1-146-32462-5.

- ^

Quanchi, Max; Adams, Ron, eds. (1993). Culture Contact in the Pacific: Essays on Contact, Encounter and Response. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521422840. Retrieved July 4, 2020.

The emergence of 'Polynesian kingdoms' during the early years of European contact in Tahiti and Hawaii has conventionally been attributed to European influence and manipulation [...].

- ^

Campbell, Ian C. (1989). "Polynesia: European settlement and the later kingdoms". A History of the Pacific Islands. UQP paperbacks. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 83. ISBN 9780520069015. Retrieved July 4, 2020.

The establishment of the Polynesian kingdoms was the culmination of pre-European stresses in island society, in conjunction with the needs and opportunities presented by contact with Europeans. Political centralization satisfied individual ambitions but also simplified the developing relationship with Europeans, both visitors and settlers.

- ^ Van Dyke, Jon (2008). Who Owns the Crown Lands of Hawaiʻi?. University of Hawaiʻi Press. pp. 30–44. ISBN 978-0824832117.

- ^ Tom Dye; Eric Komori (1992). Pre-censal Population History of Hawai'i (PDF). NA. p. 3.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Ronald T. Takaki (1984). Pau Hana: Plantation Life and Labor in Hawaii, 1835–1920. p. 22.

- ^ Harold W. Bradley, The American frontier in Hawaii: the pioneers, 1789–1843 (Stanford university press, 1942).

- ^ Julia Flynn Siler, Lost Kingdom: Hawaii's Last Queen, the Sugar Kings and America's First Imperial Adventure (2012).

- ^ Edward D. Beechert (1985). Working in Hawaii: A Labor History. University of Hawaii Press. p. 146. ISBN 978-0-8248-0890-7.

- ^ "Hawaiian Territory". Hawaiian Kingdom. Retrieved October 5, 2013.

- ^ "Kamehameha III issues the Edict of Toleration, June 17, 1839 -- Tiki Central". Tiki Central.

- ^ "The US Navy and Hawaii-A Historical Summary".

- ^ James F. B. Marshall (1883). "An unpublished chapter of Hawaiian History". Harper's magazine. Vol. 67. pp. 511–520.

- ^ "Lā Kūʻokoʻa: Events Leading to Independence Day, November 28, 1843". The Polynesian. Vol. XXI, no. 3. November 2000. Retrieved February 22, 2010.

- ^ a b "503-517".

- ^ a b David Keanu Sai (November 28, 2006). "Hawaiian Independence Day". Hawaiian Kingdom Independence web site. Retrieved February 22, 2010.

- ^ "Daily Alta California 18 March 1891 — California Digital Newspaper Collection". cdnc.ucr.edu. Retrieved July 30, 2019.

- ^ Humanities, National Endowment for the (March 31, 1891). "The Hawaiian gazette. (Honolulu [Oahu, Hawaii]) 1865-1918, March 31, 1891, Image 2". p. 2. ISSN 2157-1392. Retrieved July 30, 2019.

- ^ "Nuhou 3 February 1874 — Papakilo Database". www.papakilodatabase.com. Retrieved July 30, 2019.

- ^ Humanities, National Endowment for the (March 24, 1891). "The Hawaiian gazette. (Honolulu [Oahu, Hawaii]) 1865-1918, March 24, 1891, Image 5". p. 4. ISSN 2157-1392. Retrieved July 30, 2019.

- ^ McBride, Spencer. "Mormon Beginnings in Samoa: Kimo Belio, Samuela Manoa and Walter Murray Gibson". Brigham Young University. Retrieved May 24, 2020.

- ^ Hawaii's Story by Hawaii's Queen, Appendix A "The three ministers left Mr. Parker to try to dissuade me from my purpose; and in the meantime they all (Peterson, Cornwell, and Colburn) went to the government building to inform Thurston and his part of the stand I took."

- ^ Morgan Report, p804-805 "Every one knows how quickly Colburn and Peterson, when they could escape from the palace, called for help from Thurston and others, and how afraid Colburn was to go back to the palace."

- ^ "U.S. Navy History site".

- ^ "Blount Report – Page 588".

- ^ Kinzer, Stephen. (2006). Overthrow: America's Century of Regime Change from Hawaii to Iraq.

- ^ Stevens, Sylvester K. (1968) American Expansion in Hawaii, 1842–1898. New York: Russell & Russell. (p. 228)

- ^ Dougherty, Michael. (1992). To Steal a Kingdom: Probing Hawaiian History. (p. 167-168)

- ^ La Croix, Sumner and Christopher Grandy. (March 1997). "The Political Instability of Reciprocal Trade and the Overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom" in The Journal of Economic History 57:161–189.

- ^ a b Russ, William Adam (1992) [1959]. The Hawaiian Revolution (1893–94). Susquehanna University Press. ISBN 978-0-945636-43-4.

- ^ Liliuokalani 1898, p. 275.

Bibliography

- Liliuokalani (1898). Hawaii's Story by Hawaii's Queen, Liliuokalani. Boston: Lee and Shepard. ISBN 978-0-548-22265-2. OCLC 2387226 – via HathiTrust.

Further reading

- Beechert, Edward D. Working in Hawaii: A Labor History. University of Hawaii Press, 1985.

- Bradley, Harold W. The American Frontier in Hawaii: The Pioneers, 1789–1843. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1942.

- Daws, Gavan (1968). Shoal of Time: A History of the Hawaiian Islands. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0-8248-0324-8.

- Greenlee, John Wyatt. "Eight Islands on Four Maps: The Cartographic Renegotiation of Hawai'i, 1876-1959." Cartographica 50, 2 (2015), 119–140. online

- Haley, James L. Captive Paradise: A History of Hawaii (St. Martin's Press, 2014).

- Kuykendall, Ralph Simpson, and Arthur Grove Day. Hawaii: A History, from Polynesian Kingdom to American State. New York: Prentice Hall, 1961.

- Kuykendall, Ralph Simpson (1965) [1938]. Hawaiian Kingdom 1778–1854, foundation and transformation. Vol. Volume 1. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0-87022-431-X.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - Kuykendall, Ralph Simpson (1953). Hawaiian Kingdom 1854–1874, twenty critical years. Vol. Volume 2. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-87022-432-4.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - Kuykendall, Ralph Simpson (1967). Hawaiian Kingdom 1874–1893, the Kalakaua Dynasty. Vol. Volume 3. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-87022-433-1.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help)

- Kuykendall, Ralph Simpson (1965) [1938]. Hawaiian Kingdom 1778–1854, foundation and transformation. Vol. Volume 1. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0-87022-431-X.

- Siler, Julia Flynn. Lost Kingdom: Hawaii's Last Queen, the Sugar Kings and America's First Imperial Adventure (2012).

- Silva, Noenoe K. The Power of the Steel-Tipped Pen: Reconstructing Native Hawaiian Intellectual History. Durham, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2017.

- Sumida, Stephen H. And the View from the Shore: Literary Traditions of Hawai'i. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2015.

- Tregaskis, Richard. The warrior king: Hawaii's Kamehameha the Great (1973).

- Wilson, Rob. "Exporting Christian Transcendentalism, Importing Hawaiian Sugar: The Trans-Americanization of Hawai'i." American Literature 72#.3 (2000): 521–552. online

- Wyndette, Olive. Islands of Destiny: A History of Hawaii (1968).

External links

- Henry Soszynski. "Index to Hawaiian Kingdom Genealogy". web page on "Rootsweb". Retrieved February 16, 2010.

- Monarchy in Hawaii Part 1

- Monarchy in Hawaii Part 2

- Kingdom of Hawaii at DCStamps

- Hawaiian Kingdom

- Pre-statehood history of Hawaii

- Former countries in Oceania

- Former countries of the United States

- Former monarchies of Oceania

- States and territories established in 1795

- States and territories disestablished in 1893

- Former kingdoms

- Christian states

- Island countries

- 1795 establishments in Hawaii

- 1893 disestablishments in Hawaii

- 19th century in Hawaii