Gender pay gap

| Part of a series on |

| Discrimination |

|---|

|

The gender pay gap or gender wage gap is the average difference between the remuneration for men and women who are working. Women are generally found to be paid less than men. There are two distinct numbers regarding the pay gap: non-adjusted versus adjusted pay gap. The latter typically takes into account differences in hours worked, occupations chosen, education and job experience.[1] In the United States, for example, the non-adjusted average woman's annual salary is 79–83% of the average man's salary, compared to 95–99% for the adjusted average salary.[2][3][4]

The reasons for the gap link to legal, social and economic factors.[5] These include having children (motherhood penalty vs. fatherhood bonus), parental leave, gender discrimination and gender norms. Additionally, the consequences of the gender pay gap surpass individual grievances, leading to reduced economic output, lower pensions for women, and fewer learning opportunities.

The gender pay gap can be a problem from a public policy perspective in developing countries because it reduces economic output and means that women are more likely to be dependent upon welfare payments, especially in old age.[6][7][8]

Historical perspective

In the United States, women's pay has increased relative to men since the 1960s. According to US census data, women's median earnings in 1963 were 56% of men's.[10] In 2016, women's median earnings had increased to 79% of men's.[10] Analysis from the Institute for Women’s Policy Research published in 2017 predicted that average pay would reach parity in 2059.[11]

According to a 2021 study on historical gender wage ratios, women in Southern Europe earned approximately half that of unskilled men between 1300 and 1800. In Northern and Western Europe, the ratio was far higher but it declined over the period 1500–1800.[12]

A 2005 meta-analysis by Doris Weichselbaumer and Rudolf Winter-Ebmer of more than 260 published pay gap studies for over 60 countries found that, from the 1960s to the 1990s, raw (aka non-adjusted) wage differentials worldwide have fallen substantially from around 65% to 30%. The bulk of this decline, was due to better labor market endowments of women (i.e. better education, training, and work attachment).[13]

Another meta-analysis of 41 empirical studies on the wage gap performed in 1998 found a similar time trend in estimated pay gaps, a decrease of roughly 1% per year.[14]

A 2011 study by the British CMI concluded that if pay growth continues for female executives at current rates, the gap between the earnings of female and male executives would not be closed until 2109.[15]

Calculation

The non-adjusted gender pay gap or gender wage gap is typically the median or mean average difference between the remuneration for all working men and women in the sample chosen. It is usually represented as either a percentage or a ratio of the "difference between average gross hourly [or annual] earnings of male and female employees as % of male gross earnings".[16]

Some countries use only the full-time working population for the calculation of national gender gaps.[17][18] Others are based on a sample from the entire working population of a country (including part-time workers), in which case the full-time equivalent (FTE) is used to obtain the remuneration for an equal amount of paid hours worked.[16][19][20][21][22][23][18]

Non-governmental organizations apply the calculation to various samples. Some share how the calculation was performed and on which data set.[17] The gender pay gap can, for example, be measured by ethnicity,[24] by city,[25] by job,[26] or within a single organization.[27][28][29]

Adjusting for different causes

Comparing salary "within, rather than across" data sets helps to focus on a specific factor, by controlling for other factors. For example, to eliminate the role of horizontal and vertical segregation in the gender pay gap, salary can be compared by gender within a specific job function. To eliminate transnational differences in the job market, measurements can focus on a single geographic area instead.[26]

Causes

The non-adjusted gender pay gap is not itself a measure of discrimination. Rather, it combines differences in the average pay of women and men to serve as a barometer of comparison. Differences in pay are caused by occupational segregation (with more men in higher paid industries and women in lower paid industries), vertical segregation (fewer women in senior, and hence better paying positions), ineffective equal pay legislation, women's overall paid working hours, and barriers to entry into the labor market (such as education level and single parenting rate).[30]

Some variables that help explain the non-adjusted gender pay gap include economic activity, working time, and job tenure.[30] Gender-specific factors, including gender differences in qualifications and discrimination, overall wage structure, and the differences in remuneration across industry sectors all influence the gender pay gap.[31]

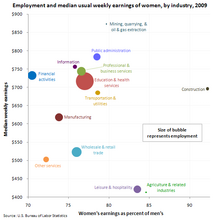

Industry sector

Occupational segregation[34] or horizontal segregation[35] refers to disparity in pay associated with occupational earnings.

A 2022 research study, conducted by Folbre et al., illustrates how the concentration of women in care occupations contributes significantly to the gender pay gap.[36] Their findings show that, while both women and men are affected by the care services wage penalties, women in these occupations face greater tribulations considering they are more likely to be employed in care services.[36] In Jacobs (1995), Boyd et al. refer to the horizontal division of labor as "high-tech" (predominantly men) versus "high-touch" (predominantly women) with high tech being more financially rewarding.[37] Men are more likely to be in relatively high-paying, dangerous industries such as mining, construction, or manufacturing and to be represented by a union.[38] Women, in contrast, are more likely to be in clerical jobs and to work in the service industry.[38]

A study of the US labor force in the 1990s suggested that gender differences in occupation, industry and union status explain an estimated 53% of the wage gap.[38] A 2017 study in the American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics found that the growing importance of the services sector has played a role in reducing the gender gap in pay and hours.[39] In 1998, adjusting for both differences in human capital and in industry, occupation, and unionism increases the size of American women's average earnings from 80% of American men's to 91%.[40]

A 2017 study by the US National Science Foundation's annual census revealed pay gaps in different areas of science: there is a much larger proportion of men in higher-paying fields such as mathematics and computer science, the two highest-paying scientific fields. Men accounted for about 75% of doctoral degrees in those fields (a proportion that has barely changed since 2007), and expected to earn $113,000 compared with $99,000 for women. In the social sciences the difference between men and women with PhD's was significantly smaller, with men earning ~$66,000, compared with $62,000 for women. However, in some fields women earn more: women in chemistry earn ~$85,000, about $5,000 more than their male colleagues.[41]

A Morningstar analysis[42] of senior executive pay data revealed that senior executive women earned 84.6 cents for every dollar earned by male executives in 2019.[43] Women also remained outnumbered in the C-Suite 7 to 1.[43]

Racial and gendered discrimination

Women experience the gender pay gap differently than one another, as do their wages. Women will earn more or less than another woman because of their race and/or ethnicity. According to the Joint Economic Committee, women of color are at a greater disadvantage than white women because they are more likely to hold jobs that "offer fewer hours and more likely to work part time involuntarily." [10][44] However, "women of every racial and ethnic group earn less than men of the same group."[45] It is also important to note that women of a certain race are more similar in numbers than across races. For example, a Black woman earns around 90% of what a Black man does, yet a Black woman only makes 68% of what a white man does.[45]

A 2015 meta-analysis of studies of experimental simulations of employment found that "men were preferred for male-dominated jobs (i.e., gender-role congruity bias), whereas no strong preference for either gender was found for female-dominated or integrated jobs".[46] However, a meta-analysis of real-life correspondence experiments found that "men applying for strongly female-stereotyped jobs need to make between twice to three times as many applications as do women to receive a positive response for these jobs" and "women applying to male-dominated jobs face lower levels of discrimination in comparison to men applying to female-dominated jobs."[47] A 2018 systematic review of almost all correspondence experiments since 2005 found that most studies found that the evidence for gender discrimination "is very mixed", and that the amount of gender discrimination varies by occupation, though two studies found "a significant penalty for being pregnant or being a mother".[48] A 2018 audit study found that high-achieving men are called back more frequently by employers than equally high-achieving women (at a rate of nearly 2-to-1).[49]

In a 2016 interview, Harvard Economist Claudia Goldin argued that overt discrimination by employers was no longer a significant cause of the gender pay gap, and that the cause is instead more subtle cultural expectations which are a legacy of historical discrimination. According to Goldin, these expectations cause women, on average, to prioritize temporal flexibility, take different risks, and avoid situations of expected discrimination. She advocated educational reforms to address the remaining gender pay gap rather than mandates on business, arguing that the latter is simply too difficult to implement given the demands of the current business environment.[50]

A series of four studies from 2019 found that "even if these careers do not pay less, people assume that men will be less interested in any career that is majority female" and that this has "the potential to create a self-fulfilling prophecy in that people are also less interested in promoting pay raises in female-dominated caregiving careers ... yet if more men were to enter these occupations, the salaries in these fields might also rise".[51]

A 2021 study in Sweden on affirmative action found that "even though people’s attitudes tend to be quite negative when women are favored, they are even more negative when preferential treatment based on gender is offered to men".[52]

Parenthood and the Motherhood Penalty

Studies have shown that an increasing share of the gender pay gap over time is due to children.[53][54] The phenomenon of lower wages due to childbearing has been termed the motherhood penalty. In short, the motherhood penalty depicts the greater disadvantage mothers face as far as earning less wages than a childless woman.[10][55] According to a study conducted by the Joint Economic Committee, in 2014 mothers were shown to earn 3% less than childless women and 15% less than childless men.[56] Although it is true that the gender pay gap has narrowed, this phenomenon is essentially only significant for childless men and women.[55] Further, studies have shown that the motherhood penalty has been unwavering, rather than declining like the gender pay gap.[55]

The contribution of the motherhood penalty to the disparity in earnings between genders differs between countries; in Southern Europe, mothers earn more than childless women, in Nordic companies, mothers earn slightly less, in Continental Europe and Anglo-Saxon European countries, the difference is larger, and in Eastern Europe, a large part of the pay gap is due to motherhood.[57]

Traditionally, mothers leave the workforce temporarily to take care of their children. The length of parental leave of mothers affect the gender pay, shorter parental leave may lead women to leave the workplace, longer parental leaves can result in reduced wages of mothers, moderate leaves allow mothers to balance career and motherhood.[57]: 2 The availability of childcare can reduces the motherhood penalty as well as increasing workplace participation by mothers.[57]: 2

Women tend to take lower paying jobs because they are more likely to have more flexible timings compared to higher-paying jobs. Since women are more likely to work fewer hours than men, they have less experience,[58] which will cause women to be behind in the work force. Mothers are more likely to work part-time.[57]: 3

A 2019 study conducted in Germany found that women with children are discriminated against in the job market, whereas men with children are not.[59] In contrast, a 2020 study in the Netherlands found little evidence for discrimination against women in hiring based on their parental status.[60]

Another explanation of such gender pay gap is the distribution of housework. Couples who raise a child tend to designate the mother to do the larger share of housework and take on the main responsibility of childcare, and as a result, women tend to have less time available for wage-earning. This reinforces the pay gap between males and females in the labor market, and now people are trapped in this self-reinforcing cycle.[61]

Maternity leave in the United States

The United States maternity leave policy states that employees who have worked the necessary allotted hours are allowed a total of 12 weeks away from work, unpaid. However, these benefits are only regulated to employers who have more than 50 employees.[62] Smaller businesses or companies with less than 50 people are not required to provide leave for new mothers. While the 12 weeks are intended to be used after a mother gives birth or newly adopts, the time can also be used up if there are complications with the pregnancy that require them to miss work.[62] The 12 week unpaid policy in the U.S. is being expanded upon in a few states across the country. For example, New Jersey is now offering new mothers and their families the option to enroll in programs that allow them compensation while away from their job.[63] Now, mothers have a way secure income despite not working.

The National Bureau of Economic Research has found that in Denmark most of the wage-gap gender inequality was because of children. The researchers found that the arrival of children creates a long run earnings gap of around 20 percent for women, while men remain unaffected. The researchers also found that the amount of child-related gender inequality has increased significantly over time, from approximately 40 percent in 1980, to 80 percent in 2013.[64]

The introduction of a child to some American families results in 43% of new mothers in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) to face major career changes, varying from abandoning the workforce entirely to exchanging their careers in STEM for part-time work, or a career in another field.[65] While this is true for new mothers, some studies show that both new mothers and fathers report being affected by “flexibility stigma” in the workplace.[66] Flexibility stigma can be defined as the consequences imposed on workers for attempting to balance the responsibilities of their careers and families.[67] It has also been found that career-people of the STEM field with young children face more "work-family" conflict, as the demands of the rigorous STEM field and those of their young children overlap.[68]

Gender norms

Another social factor, which is related to the aforementioned one, is the socialization of individuals to adopt specific gender roles.[69][70] Job choices influenced by socialization are often slotted in to "demand-side" decisions in frameworks of wage discrimination,[71] rather than a result of extant labor market discrimination influencing job choice.[72] Men that are in non-traditional job roles or jobs that are primarily seen as a women-focused jobs, such as nursing, have high enough job satisfaction that motivates the men to continue in these job fields despite criticism they may receive.[73]

According to a 1998 study, in the eyes of some employees, women in middle management are perceived to lack the courage, leadership, and drive that male managers appear to have,[74] despite female middle managers achieving results on par with their male counterparts in terms of successful projects and achieving results for their employing companies.[74][failed verification] These perceptions, along with the factors previously described in the article, contribute to the difficulty of women to ascend to the executive ranks when compared to men in similar positions.[75]

Societal ideas of gender roles stem somewhat from media influences.[76] Media portrays ideals of gender-specific roles off of which gender stereotypes are built.[77] These stereotypes then translate to what types of work men and women can or should do.[76] In this way, gender plays a mediating role in work discrimination, and women find themselves in positions that do not allow for the same advancements as males.[76]

Some research suggests that women are more likely to volunteer for tasks that are less likely to help earn promotions, and that they are more likely to be asked to volunteer and more likely to say yes to such requests.[78]

Technology and automation

Automation is expected to affect male and female employment differently, as the overall labor market is heavily gendered. A paper published in 2019 by the International Monetary Fund predicted that women are significantly more likely to be displaced by automation than male workers. The researchers found that female workers performed more routine tasks in their jobs than men, which are vulnerable to automation. They estimated that “26 million female jobs in 30 countries (28 OECD member countries, Cyprus, and Singapore) are at a high risk of being displaced by technology (i.e., facing higher than 70 percent likelihood of being automated)” over the next two decades.[79]

Overwork

Claudia Goldin found that the gender pay gap is largely caused by women having children, and that other causes for the pay gap include discrimination and "greedy work".[80] "Greedy work" has been defined as jobs which pay a large premium for overwork (significantly more than 40 hours per week) and round-the-clock availability (eg. managerial, finance, law, and consulting jobs.).[80] Women who work in those jobs get paid the same as men, though very few women (and fewer mothers) choose overwork jobs, often because it is incompatible with child raising.[80] Golden's research suggests that the best solution for overwork is that employees need to start demanding more predictabiliy and flexibility, and companies need to realize that more work can be shared and that highly skilled employees are more interchangeable than employers are accustomed to believing.[80]

Consequences

The gender pay gap can be a problem from a public policy perspective because it reduces economic output and means that women are more likely to be dependent upon welfare payments, especially in old age.[6][7][8]

For economic activity

A 2009 report for the Australian Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs argued that in addition to fairness and equity there are also strong economic imperatives for addressing the gender wage gap. The researchers estimated that a decrease in the gender wage gap from 17% to 16% would increase GDP per capita by approximately $260, mostly from an increase in the hours females would work. Ignoring opposing factors as hours females work increase, eliminating the whole gender wage gap from 17% could be worth around $93 billion or 8.5% of GDP. The researchers estimated the causes of the wage gap as follows, lack of work experience was 7%, lack of formal training was 5%, occupational segregation was 25%, working at smaller firms was 3%, and being female represented the remaining 60%.[81]

An October 2012 study by the American Association of University Women found that over the course of 47 years, an American woman with a college degree will make about $1.2 million less than a man with the same education.[82] Therefore, closing the pay gap by raising women's wages would have a stimulus effect that would grow the United States economy by at least 3% to 4%.[83][84]

Using data from 2019, the Institute for Women’s Policy Research reported in May 2021 that if women in the American labor force received pay comparable with their male counterparts, poverty for women in the labor force would be reduced by over 40 percent on average. High poverty rates among working single mothers would fall from 27.7 percent to 16.7 percent. Moreover, they found that equal pay for women in the labor force would increase their annual earnings from $41,402 to $48,326—an increase of 541 billion dollars in overall wage income in the United States economy—equivalent to 2.8 percent of the GDP in 2019.[85]

For women's pensions

Considering women make less than men overall, they are also less likely to be eligible to participate in pension plans.[10] This is because pensions plans are generally calculated based on one's salary per year.[10] Further, this would require women to be employed in jobs that offer retirement plans, which they are less likely to be a part of than men.[10] The European Commission argues that the pay gap has significant effects on pensions. Since women's lifetime earnings are on average 17.5% (as of 2008) lower than men's, they have lower pensions. As a result, elderly women are more likely to face poverty: 22% of women aged 65 and over are at risk of poverty compared to 16% of men.[86]

For education and debt

Analysis conducted by the World Bank and available in the 2019 World Development Report on The Changing Nature of Work[87] connects earnings with skill accumulation, suggesting that women also accumulate less human capital (skills and knowledge) at work and through their careers. The report shows that the payoffs to work experience is lower for women across the world as compared to men. For example, in Venezuela, for each additional year of work, men's wages increase on average by 2.2 percent, compared to only 1.5 percent for women. In Denmark, by contrast, the payoffs to an additional year of work experience are the same for both men and women, at 5 percent on average. To address these differences, the report argues that governments could seek to remove limitations on the type or nature of work available to women and eliminate rules that limit women's property rights. Parental leave, nursing breaks, and the possibility for flexible or part-time schedules are also identified as potential factors limiting women's learning in the workplace.

For domestic violence

Economists predict that partners with higher wages have greater bargaining power within their household dynamics.[88] The gender pay gap thus may put women at a disadvantage to their male partners. Moreover, research has found that the fewer resources women have available to them, the less likely they are to leave an abusive relationship.[89] Other economic models have expanded upon this idea, demonstrating that when pursuing divorce is too costly, the threat of domestic violence may act as a potential method to shift bargaining advantages within a household.[90] Researchers have further established an explicit relation between domestic violence and labor market conditions, finding that the decline in the wage gap from 1990 to 2003 explained a nine percent decrease in domestic violence rates.[91] The estimated costs of domestic violence due to medical care and declines in productivity may be as much as $9.3 billion.[92] Women tend to be affected by this more than men, and in addition, exposure to domestic abuse has negative implications not only for adults, but also for children in proximity to the abuse. At least 50 percent of the variability in lifetime earnings can be attributed to early childhood experience, and adults from households with documented abuse and neglect have lower levels of education, as well as economic earnings and assets.[93]

Economic theories

In 2023 economist Claudia Goldin won the Nobel Economics Prize for her work on understanding the gender pay gap. She found that the gender pay gap is largely caused by women having children,[94][95] and that other causes for the pay gap include discrimination and "greedy work" (jobs which pay a large premium for working significantly more than 40 hours per week and round-the-clock availability.)[96]

Neoclassical models

In certain neoclassical models, discrimination by employers can be inefficient; excluding or limiting employment of a specific group will raise the wages of groups not facing discrimination. Other firms could then gain a competitive advantage by hiring more workers from the group facing discrimination. As a result, in the long run discrimination would not occur. However, this view depends on strong assumptions about the labor market and the production functions of the firms attempting to discriminate.[97] Firms which discriminate on the basis of real or perceived customer or employee preferences would also not necessarily see discrimination disappear in the long run even under stylized models.[98]

Monopsony explanation

In monopsony theory, which describes situations where there is only one buyer (in this case, a "buyer" for labor), wage discrimination can be explained by variations in labor mobility constraints between workers. Ransom and Oaxaca (2005) show that women appear to be less pay sensitive than men, and therefore employers take advantage of this and discriminate in their pay for women workers.[99]

Policy measures

Anti-discrimination legislation

According to the 2008 edition of the Employment Outlook report by the OECD, almost all OECD countries have established laws to combat discrimination on grounds of gender. Examples of this are the Equal Pay Act of 1963 and Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.[100] Legal prohibition of discriminatory behavior, however, can only be effective if it is enforced. The OECD points out that:

herein lies a major problem: in all OECD countries, enforcement essentially relies on the victims' willingness to assert their claims. But many people are not even aware of their legal rights regarding discrimination in the workplace. And even if they are, proving a discrimination claim is intrinsically difficult for the claimant and legal action in courts is a costly process, whose benefits down the road are often small and uncertain. All this discourages victims from lodging complaints.[101]

Moreover, although many OECD countries have put in place specialized anti-discrimination agencies, only in a few of them are these agencies effectively empowered, in the absence of individual complaints, to investigate companies, take actions against employers suspected of operating discriminatory practices, and sanction them when they find evidence of discrimination.[101][102]

In 2003, the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) found that women in the United States, on average, earned 80% of what men earned in 2000 and workplace discrimination may be one contributing factor. In light of these findings, GAO examined the enforcement of anti-discrimination laws in the private and public sectors. In a 2008 report, GAO focused on the enforcement and outreach efforts of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) and the Department of Labor (Labor). GAO found that EEOC does not fully monitor gender pay enforcement efforts and that Labor does not monitor enforcement trends and performance outcomes regarding gender pay or other specific areas of discrimination. GAO came to the conclusion that "federal agencies should better monitor their performance in enforcing anti-discrimination laws."[103][104]

In 2016, the EEOC proposed a rule to submit more information on employee wages by gender to better monitor and combat gender discrimination.[105] In 2018, Iceland enacted legislation to reduce the country's pay gap.[106]

Awareness campaigns

Civil society groups organize awareness campaigns that include activities such as Equal Pay Day or the equal pay for equal work movement to increase the public attention received by the gender pay gap. For the same reason, various groups publish regular reports on the current state of gender pay differences. An example is the Global Gender Gap Report.

Job flexibility

The growth of the "gig" economy generates worker flexibility that, some have speculated, will favor women.[107] However, the analysis of earnings among more than one million Uber drivers in the United States surprisingly showed that the gender pay gap between drivers is about 7% in favor of men. Uber's algorithm does not distinguish the gender of its workers, but men get more income because they choose better when and in which areas to work, and cancel and accept trips in a more lucrative way. Finally, men drive 2.2% faster than women, which also allows them to increase their income per unit of time.[107][108][109] The study concludes the "gig" economy can perpetuate the gender pay gap even in the absence of discrimination.[107][108][109]

In 2020, researchers from Stanford University used data from more than one million Uber drivers to show that, despite female drivers earning 7% less than male drivers, this difference was "entirely attributed to three factors: experience on the platform (...), preferences and constraints over where to work (...), and preferences for driving speed"; they noted that their results " suggest that there is no reason to expect the "gig" economy to close gender differences. Even in the absence of discrimination and in flexible labor markets, women's relatively high opportunity cost of non-paid-work time and gender-based differences in preferences and constraints can sustain a gender pay gap."[110][111][undue weight? – discuss]

By country

This is a plot of non-adjusted pay gaps (median earnings of full-time employees) according to the OECD.

0.12 0.20 0.25 | 0.30 0.35 0.40 | 0.45 0.50 0.55 | 0.60 0.65 0.70 | 0.75 0.80 0.90 |

Moreover, the World Economic Forum provides data from 2015 that evaluates the gender pay gap in 145 countries. Their evaluations take into account economic participation and opportunity, educational attainment, health and survival, and political empowerment scores.[114]

Australia

In Australia, the Workplace Gender and Equality Agency (WGEA), an Australian Government statutory agency, publishes data from non-public sector Australian organizations. There is a pay gap across all industries.[115] The gender pay gap is calculated on the average weekly ordinary time earnings for full-time employees published by the Australian Bureau of Statistics. The gender pay gap excludes part-time earnings, casual earnings, and increased hourly rates for overtime.[116]

Australia has a persistent gender pay gap. Between 1990 and 2020, the gender pay gap remained within a range of between 13 and 19%.[117] In November 2020, the Australian gender pay gap was 13.4%.[117]

Ian Watson of Macquarie University examined the gender pay gap among full-time managers in Australia over the period 2001–2008, and found that between 65 and 90% of this earnings differential could not be explained by a large range of demographic and labor market variables. In fact, a "major part of the earnings gap is simply due to women managers being female". Watson also notes that despite the "characteristics of male and female managers being remarkably similar, their earnings are very different, suggesting that discrimination plays an important role in this outcome".[118] A 2009 report to the Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs also found that "simply being a woman is the major contributing factor to the gap in Australia, accounting for 60 per cent of the difference between women's and men's earnings, a finding which reflects other Australian research in this area". The second most important factor in explaining the pay gap was industrial segregation.[81] A report by the World Bank also found that women in Australia who worked part-time jobs and were married came from households which had a gendered distribution of labor, possessed high job satisfaction, and hence were not motivated to increase their working hours.[119]

Brazil

This section may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: needs tweaking for tone, flow. (May 2018) |

The Global Gender Gap Report ranks Brazil at 95 out of 144 countries on pay equality for like jobs.[120] Brazil has a score of 0.684, which is a little below 2017's global index. In 2017, Brazil was one of the 6 countries that fully closed their gaps on both the Health and Survival and Educational Attainment sub-indexes. However, Brazil saw a setback in the progress towards gender parity this year, with its overall gender gap standing at its widest point since 2011. This is due to an exponential growth of Brazil's Political Empowerment gender gap, which measures the ratio of females in the parliament and at a ministerial level, that is too large to be counterbalanced by a range of modest improvements across the country's Economic Participation and Opportunity sub-index.[121]

According to the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics, or IBGE, women in Brazil study more, work more and earn less than men. On average, combining paid work, household chores and caring for people, women work three hours a week more than men. In fact, the average women will work 54.4 hours a week, and the average man will only work 51.4 hours per week. Despite that, even with a higher educational level, women earn, on average, less than men do. Although the difference between men's and women's earnings has declined in recent years, in 2016 women still received the equivalent of 76.5% of men's earnings. One of the factors that may explain this difference is that only 37.8% of management positions in 2016 were held by women. According to IBGE, occupational segregation and the wage discrimination of women in the labor market also have an important role in the wage difference between men and women.[122] According to data from the Continuous National Household Sample Survey, done by IBGE on the fourth quarter of 2017, 24.3% of the 40.2 million Brazilian workers had completed college, but this proportion was of 14.6% among employed men. As reported by the same survey, women who work earn 24.4% less, on average, than men. It also cited that 6.0% of working men were employers, while the proportion of women employers was only 3.3%. The survey also pointed out that 92.3% of domestic workers, a job culturally known as "feminine" and that pays low wages, are women. While high paying occupations like civil construction employed 13% of the employed men and only 0.5% of the employed women.[123] Other reason that might explain the gender wage gap in Brazil are the very strict labor regulations that increase informal hiring. In Brazil, under law, female workers may opt to take 6 months of maternity leave that must be fully paid by the employer. Many researches are concerned with this regulations. They question if these regulations may actually force workers into informal jobs, where they will have no rights at all. In fact, women who work on informal jobs earn only 50% of the average women in formal jobs. Between men the difference is less radical: men working on informal jobs earn 60% of the average men in formal jobs.[124]

Canada

A study of wages among Canadian supply chain managers found that women make an average of $14,296 a year less than men.[125] Similarly, a study in the healthcare sector found that women health managers earn 12% less than men at the middle-level and 20% less at the senior level, after adjusting statistically for age, education and other characteristics.[126] The research further suggests that as skilled professionals move up the management pipeline, they are less likely to be female.[125][126] Women in Canada are also more likely to be found in low-wage work compared to men. There remains the question of why such a trend seems to resonate throughout the developed world. One identified societal factor that has been identified is the influx of women of colour and immigrants into the workforce. These groups both tend to be subject to lower paying jobs from a statistical perspective.[127] Each province and territory in Canada has a quasi-constitutional human rights code which prohibits discrimination based on sex. Several also have laws specifically prohibiting public sector and private sector employers from paying men and women differing amounts for substantially similar work. Verbatim, the Alberta Human Rights Act states in regards to equal pay, "Where employees of both sexes perform the same or substantially similar work for an employer in an establishment the employer shall pay the employees at the same rate of pay."[128] However, pay equity policies do not adequately address gender bias and the tendency for women to be clustered into jobs and sectors that pay less than men despite similarity in skills, qualifications, working conditions and levels of responsibility.[129]

China

Using the gaps between men and women in economic participation and opportunity, educational attainment, health and survival, and political empowerment, The Global Gender Gap Report 2018 ranks China's gender gap at 110 out of 145 countries.[130] As an upper middle income country, as classified by the World Bank, China is the "third-least improved country in the world" on the gender gap. The health and survival sub-index is the lowest within the countries listed; this sub-index takes into account the gender differences of life expectancy and sex ratio at birth (the ratio of male to female children to depict the preferences of sons in accordance with China's One Child Policy).[131]: 4, 26 In particular, Jayoung Yoon, a researcher, claims the women's employment rate is decreasing. However, several of the contributing factors might be expected to increase women's participation. Yoon's contributing factors include: the traditional gender roles; the lack of childcare services provided by the state; the obstacle of child rearing; and the highly educated, unmarried women termed "leftover women" by the state. The term "leftover women" produces anxieties for women to rush marriage, delaying employment. In alignment with the traditional gender roles, the "Women Return to the Home" movement by the government encouraged women to leave their jobs to alleviate the men's unemployment rate.[132]

Dominican Republic

Dominican women, who are 52.2% of the labor force, earns an average of 20,479 Dominican pesos, 2.6% more than Dominican men's average income of 19,961 pesos.[133] The Global Gender Gap ranking, found by compiling economic participation and opportunity, educational attainment, health and survival, and political empowerment scores, in 2009 it was 67th out of 134 countries representing 90% of the globe, and its ranking has dropped to 86th out of 145 countries in 2015. More women are in ministerial offices, improving the political empowerment score, but women are not receiving equal pay for similar jobs, preserving the low economic participation and opportunity scores.[131]: 15–17, 23 [134]

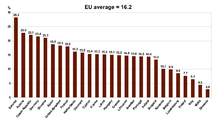

European Union

At EU level, the gender pay gap is defined as the relative difference in the average gross hourly earnings of women and men within the economy as a whole. Eurostat found a persisting gender pay gap of 17.5% on average in the 27 EU Member States in 2008.[citation needed] There were considerable differences between the Member States, with the non-adjusted pay gap ranging from less than 10% in Italy, Slovenia, Malta, Romania, Belgium, Portugal, and Poland to more than 20% in Slovakia, the Netherlands, Czech Republic, Cyprus, Germany, United Kingdom, and Greece and more than 25% in Estonia and Austria.[135] However, taking into account the hours worked in Finland, men there only earned 0.4% more in net income than women.[136][137]

A recent survey of international employment law firms showed that gender pay gap reporting is not a common policy internationally. Despite such laws on a national level being few and far between, there are calls for regulation on an EU level. A recent (as of December 2015) resolution of the European Parliament urged the Commission to table legislation closing the pay gap. A proposal that is substantively the same as the UK plan was passed by 344 votes to 156 in the European Parliament.[138]

The European Commission has stated that the undervaluation of female work is one of the main contributors to the persisting gender pay gap.[139] They add that explanations of the pay gap goes beyond discrimination, and that other factors contributes in upholding the gap: factors such as work-life balance, the issue of women in leadership and the glass ceiling, and sectoral segregation, which has to do with the overrepresentation of women in low-paying sectors.[140]

Finland

On average, between 1995 and 2005, women in Finland earned 28.4% less in non-adjusted salaries than men.[136] Taking into account the high progressive tax rate in Finland, the net income difference was 22.7%.[136] Adjusted for the amount of hours worked (and not including unpaid national military service hours), these wage differences are reduced to approximately 5.7% (non taxed) and 0.4% (tax-adjusted).[136]

The difference in the amount of hours worked is largely attributed to social factors; for example, women in Finland spend considerably more time on domestic work instead.[136] Other considerable factors are increased pay rates for overtime and evening/night-time work, of which men in Finland, on average, work more.[136] When comparing people with the same job title, women in public sector positions earn approximately 99% of their male counterparts, while those in the private sector only earn 95%.[141] Public sector positions are generally more rigidly defined, allowing for less negotiation in individual wages and overtime/evening/night-time work.

As of 2018 Finland is ranked fourth and has fully closed gender gap on Educational Attainment and have closed more than 82% of its overall gender gap.[142]

Germany

Women earn 22–23% less than men, according to the Federal Statistical Office of Germany. The revised gender pay gap was 6–8% in the years 2006–2013.[143] The Cologne Institute for Economic Research adjusted the wage gap to less than 2%. They reduced the gender pay gap from 25% to 11% by taking in account the work hours, education and the period of employment. The difference in revenue was reduced furthermore if women had not paused their job for more than 18 months due to motherhood.[144][145]

The most significant factors associated with the remaining gender pay gap are part-time work, education and occupational segregation (less women in leading positions and in fields like STEM).[146]

In 2017, Germany passed the Transparency in Wage Structures Act, which requires larger employers to publish information about gender pay gaps and gives employees the right to information about their salary in comparison to members of the opposite gender.

Luxembourg

In Luxembourg, the total gender income gap represents 32.5%.[147] The gender pay gap of full-time workers regarding monthly gross wages has narrowed over the past few years. According to the data from OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development) the gender pay gap dropped over 10% between 2002 and 2015.[148] The gap is also dependent on the age group. Females between the ages of 25–34 years are getting higher wages than males in this time period. One of the reasons for that is that they have a higher level of education during this age. From the age of 35 years males earn higher salaries than females.[149]

The current extent of gender pay gap refers to different factors such as varying working hours and diverse participation in the labor market.[150] More females (30.4%) than males (4.6%) are working part-time,[151] due to this fact the overall working hours for females are lowered.[147] The labor force participation represents 60.3% for females and 76% for males, because most women will take advantage of the maternity leave.[151] Males participate more often in higher paid jobs, for instance in executive positions (93.7%), what affects the scale of the gender pay gap as well.[147]

There is also a gender gap in vocational degree (12%) and apprentice training (3.4%) in Luxembourg.[152]

Netherlands

In the Netherlands, recent numbers from the CBS (Central Bureau voor statistieken; English: Central Bureau of Statistics) claim that the pay gap is getting smaller. Adjusted for occupation level, education level, experience level, and 17 other variables the difference in earnings in businesses has fallen from 9% (2008) to 7% (2014) and in government from 7% (2008) to 5% (2014). Without adjustments the gap is for businesses 20% (2014) and government 10% (2014). Young women earn more than men up until the age of 30, this is mostly due to a higher level of education. Women in the Netherlands, up until the age of 30, have a higher educational level on average than men; after this age men have on average a higher educational degree. The chance can also be caused by women getting pregnant and start taking part-time jobs so they can care for the children.[153]

India

For the year 2013, the gender pay gap in India was estimated to be 24.81%.[154] Further, while analyzing the level of female participation in the economy, a report slots India as one of the bottom 10 countries on its list. Thus, in addition to unequal pay, there is also unequal representation, because while women constitute almost half the Indian population (about 48% of the total), their representation in the work force amounts to only about one-fourth of the total.[155]

Japan

Jayoung Yoon analyzes Japan's culture of the traditional male breadwinner model, where the husband works outside of the house while the wife is the caretaker. Despite these traditional gender roles for women, Japan's government aims to enhance the economy by improving the labor policies for mothers with Abenomics, an economy revitalization strategy. Yoon believes Abenomics represents a desire to remedy the effects of an aging population rather than a desire to promote gender equality. Evidence for the conclusion is the finding that women are entering the workforce in contingent positions for a secondary income and a company need of part-time workers based on mechanizing, outsourcing and subcontracting. Therefore, Yoon states that women's participation rates do not seem to be influenced by government policies but by companies' necessities.[132] The Global Gender Gap Report 2015 said that Japan's economic participation and opportunity ranking (106th), 145th being the broadest gender gap, dropped from 2014 "due to lower wage equality for similar work and fewer female legislators, senior officials and managers".[131]: 25–27

Jordan

From a total of 145 states, the World Economic Forum calculates Jordan's gender gap ranking for 2015 as 140th through economic participation and opportunity, educational attainment, health and survival, and political empowerment evaluations. Jordan is the "world's second-least improved country" for the overall gender gap.[131]: 25–27 The ranking dropped from 93rd in 2006.[134]: 9 In contradiction to Jordan's provisions within its constitution and being signatory to multiple conventions for improving the gender pay gap, there is no legislation aimed at gender equality in the workforce.[156] According to The Global Gender Gap Report 2015, Jordan had a score of 0.61; 1.00 being equality, on pay equality for like jobs.[131]: 25, 222

Korea

As stated by Jayoung Yoon, South Korea's female employment rate has increased since the 1997 Asian financial crisis as a result of women 25 to 34 years old leaving the workforce later to become pregnant and women 45 to 49 years old returning to the workforce. Mothers are more likely to continue working after child rearing on account of the availability of affordable childcare services provided for mothers previously in the workforce or the difficulty to be rehired after taking time off to raise their children.[132] The World Economic Forum found that, in 2015, South Korea had a score of 0.55, 1.00 being equality, for pay equality for like jobs. From a total of 145 countries, South Korea had a gender gap ranking of 115th (the lower the ranking, the narrower the gender gap). On the other hand, political empowerment dropped to half of the percentage of women in the government in 2014.[131]: 26, 228

In 2018, the gender wage gap in South Korea is of 34.6% and women earned about 65.4% of what men did on average, according to OECD data.[157] With regards to monthly earnings, including part-time jobs, the gender gap can be explained primarily by the fact that women work few hours than men, but occupation and industry segregation also pay an important role.[158] Korea is considered to have the worst wage gap among the industrialized countries.[159] This gap is often overlooked.[160] In addition, as many women leave the workplace once married or pregnant, the gender gap in pension entitlements is affected too, which in turn impacts the poverty level.[161]

North Korea, on the other hand, is one of few countries where women earn more than men. The disparity is due to women's greater participation in the shadow economy of North Korea.[162]

New Zealand

Although recent studies have shown that the gender wage gap in New Zealand has diminished in the last two decades, the gap continues to affect many women today. According to StatsNZ, the wage gap was measured to be 9.4 percent in September 2017. Back in 1998, it was measured to be approximately 16.3 percent. There are several different factors that affect New Zealand's wage gap. However, researchers claim that 80 percent of these factors cannot be elucidated, which often causes difficulty in understanding the gap.[163]

In order to calculate the gap, New Zealand makes use of several different methods. The official gap is calculated by Statistics New Zealand. They use the difference between men and women's hourly revenue. On the other hand, the State Services Commission examine the average income of men and women for their calculation.[163] Over the years, the OECD has and continues to track New Zealand's, along with 34 other countries', gender wage gap. In fact, the overall goal of the OECD is to fix the wage gap so that gender no longer plays a significant role in an individual's income.[164] Although it has been a gradual change, New Zealand is one of the countries that has seen notable progress and researchers have predicted that it will continue to do so.

Russia

A wage gap exists in Russia (after 1991, but also before) and statistical analysis shows that most of it cannot be explained by lower qualifications of women compared to men. On the other hand, occupational segregation by gender and labor market discrimination seem to account for a large share of it.[165][166][167][168][169][170]

The October Revolution (1917) and the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, have shaped the developments in the gender wage gap. These two main turning points in the Russian history frame the analysis of Russia's gender pay gap found in the economic literature. Consequently, the pay gap study can be examined for two periods: the wage gap in Soviet Russia (1917–1991) and the wage gap in the transition and post-transition (after 1991).

Singapore

According to Jayoung Yoon, Singapore's aging population and low fertility rates are resulting in more women joining the labor force in response to the government's desire to improve the economy. The government provides tax relief to mothers in the workforce to encourage them to continue working. Yoon states that "as female employment increases, the gender gap in employment rates...narrows down" in Singapore.[132] The Global Gender Gap Report 2015 ranks Singapore's gender gap at 54th out of 145 states globally based on the economic participation and opportunity, the educational attainment, the health and survival, and the political empowerment sub-indexes (a lower rank means a smaller gender gap). The gender gap narrowed from 2014's ranking of 59. In the Asia and Pacific region, Singapore has evolved the most in the economic participation and opportunity sub-index, yet it is lower than the region's means in educational attainment and political empowerment.[131]: 25–27

United Kingdom

As of April 2022 the average gender pay gap is 8.3%,[171] although men get paid less than women for part-time work.[172][173] The gap varies considerably from −4.4% (women employed part-time without overtime out earn men) to 26% (for UK women employed full-time aged 50 – 59).[172] In 2012 the pay gap officially dropped below 10% for full-time workers.[174][175] The median pay, the point at which half of people earn more and half earn less, is 17.9% less for employed women than for employed men.[176]

The most significant factors associated with the gender pay gap are full-time/part-time work, education, the size of the firm a person is employed in, and occupational segregation (women are under-represented in managerial and high-paying professional occupations).[177] In part-time roles women out-earn men by 4.4% in 2018[176] (6.5% in 2015, 5.5% in 2014).[178] Women workers qualified to GCSE or A level standard, experienced a smaller pay gap in 2018. (Those qualified to degree level have seen little change).[176] A 2015 study compiled by the Press Association based on data from the Office for National Statistics revealed that women in their 20s were out-earning men in their 20s by an average of £1,111, showing a reversal of trends. However, the same study showed that men in their 30s out-earned women in their 30s by an average of £8,775. The study did not attempt to explain the causes of the gender gap.[179][needs update]

In October 2014, the UK Equality Act 2010 was augmented with regulations which require Employment Tribunals to order an employer (except an existing micro-business or a new business) to carry out an equal pay audit where the employer is found to have breached equal pay law.[180] The then prime minister David Cameron announced plans to require large firms to disclose data on the gender pay gap among staff.[181] Since April 2018, employers with over 250 employees are legally required to publish data relating to pay inequalities. Data published includes the pay and bonus figures between men and women, and includes data from April 2017.[182][183]

A BBC analysis of the figures after the deadline expired showed that more than three-quarters of UK companies pay men more on average than women.[184] Employment barrister Harini Iyengar advocates more flexible working and greater paternity leave to achieve economic and cultural change.[185]

United States

In the US, women's average annual salary has been estimated as 78%[186] to 82%[187] of that of men's average salary. Beyond overt discrimination, multiple studies explain the gender pay gap in terms of women's higher participation in part-time work and long-term absences from the labor market due to care responsibilities, among other factors.[188][189][190]

The extent to which discrimination plays a role in explaining gender wage disparities is somewhat difficult to quantify. A 2010 research review by the majority staff of the United States Congress Joint Economic Committee reported that studies have consistently found unexplained pay differences even after controlling for measurable factors that are assumed to influence earnings – suggestive of unknown/non-measurable contributing factors of which gender discrimination may be one.[191] Other studies have found direct evidence of discrimination – for example, more jobs went to women when the applicant's sex was unknown during the hiring process.[191]

See also

- Economic inequality

- Feminization of poverty

- Gender inequality

- Gender pension gap

- Glass ceiling

- Global Gender Gap Report

- Income inequality metrics

- International inequality

- Lowell Mill Girls

- Material feminism

- For other wage gaps

References

- ^ "Gender Pay Gap". www.genderequality.ie. Archived from the original on 2021-04-25.

- ^ "2023 Gender Pay Gap Report (GPGR)". Payscale - Salary Comparison, Salary Survey, Search Wages. 2023-03-13. Retrieved 2023-04-20.

- ^ "Progress on the Gender Pay Gap: 2019 - Glassdoor". Glassdoor Economic Research. 2019-03-27. Retrieved 2021-03-09.

- ^ The Simple Truth About The Gender Wage Gap (Report). 1310 L St. NW, Suite 1000 Washington, DC 20005. Spring 2018. Archived from the original on 2017-02-24. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

{{cite report}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Eurostat (8 March 2017). "Only 1 manager out of 3 in the EU is a woman... earning on average almost a quarter less than a man" (PDF) (Press release).

- ^ a b Bandara, Amarakoon (3 April 2015). "The Economic Cost of Gender Gaps in Effective Labor: Africa's Missing Growth Reserve". Feminist Economics. 21 (2): 162–186. doi:10.1080/13545701.2014.986153. ISSN 1354-5701. S2CID 154698810.

- ^ a b Klasen, Stephan (5 October 2018). "The Impact of Gender Inequality on Economic Performance in Developing Countries". Annual Review of Resource Economics. 10 (1): 279–298. doi:10.1146/annurev-resource-100517-023429. ISSN 1941-1340. S2CID 158819118.

- ^ a b Mandel, Hadas; Shalev, Michael (1 June 2009). "How Welfare States Shape the Gender Pay Gap: A Theoretical and Comparative Analysis". Social Forces. 87 (4): 1873–1911. doi:10.1353/sof.0.0187. ISSN 0037-7732. S2CID 20802566.

- ^ "Women's earnings as a percentage of men's, 1979-2005". United States Department of Labor. 3 October 2006. Retrieved 16 February 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g Maloney, Carolyn B. (April 2016). "Gender Pay Inequity: Consequences for Women, Families and the Economy" (PDF). Joint Economic Committee.

- ^ Pham, Xuan; Fitzpatrick, Laura; Wagner, Richard (2018-01-01). "The US gender pay gap: the way forward". International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy. 38 (9/10): 907–920. doi:10.1108/IJSSP-01-2018-0002. ISSN 0144-333X. S2CID 150122314.

- ^ Pleijt, Alexandra de; Zanden, Jan Luiten van (2021). "Two worlds of female labour: gender wage inequality in western Europe, 1300–1800†". The Economic History Review. 74 (3): 611–638. doi:10.1111/ehr.13045. ISSN 1468-0289.

- ^ Weichselbaumer, Doris; Winter-Ebmer, Rudolf (2005). "A Meta-Analysis on the International Gender Wage Gap" (PDF). Journal of Economic Surveys. 19 (3): 479–511. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.318.9241. doi:10.1111/j.0950-0804.2005.00256.x. S2CID 88508221.

- ^ Stanley, T. D.; Jarrell, Stephen B. (1998). "Gender Wage Discrimination Bias? A Meta-Regression Analysis". The Journal of Human Resources. 33 (4): 947–973. doi:10.2307/146404. JSTOR 146404.

- ^ Goodley, Simon (2011-08-31). "Women executives could wait 98 years for equal pay, says report". The Guardian. London. Retrieved August 31, 2011.

While the salaries of female executives are increasing faster than those of their male counterparts, it will take until 2109 to close the gap if pay grows at current rates, the Chartered Management Institute reveals.

- ^ a b "Gender pay gap statistics - Statistics Explained". ec.europa.eu. Eurostat.

- ^ a b Kochhar, Rakesh (11 December 2013). "How Pew Research measured the gender pay gap". Pew Research Center.

- ^ a b "Australia's Gender Pay Gap Statistics". Australian Government Workplace Gender Equality Statistics. 20 February 2020.

- ^ Workplace Gender Equality Agency (7 November 2013). "What is the gender pay gap? - The Workplace Gender Equality Agency". wgea.gov.au. Australian Government. Archived from the original on 31 October 2015. Retrieved 7 February 2019.

- ^ "The Gender Pay Gap Explained" (PDF). gov.uk. Retrieved 7 February 2019.

- ^ "Breaking down the gender wage gap" (PDF). dol.gov. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 July 2018. Retrieved 7 February 2019.

- ^ Bureau, US Census. "Income and Poverty in the United States: 2016". www.census.gov.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ Wilkinson, Kate; Mwiti, Lee, eds. (27 September 2017). "Do South African women earn 27% less than men?". Africa Check.

- ^ Hegeswisch, Ariane; Williams-Baron, Emma (7 March 2018). "The Gender Wage Gap: 2017 Earnings Differences by Race and Ethnicity". Institute for Women's Policy Research. Archived from the original on 5 August 2018.

- ^ Sheth, Sonam; Hoff, Madison; Ward, Marguerite; Tyson, Taylor (15 March 2022). "These 8 charts show the glaring gap between men's and women's salaries in the US". Business Insider.

- ^ a b McCandless, David; Quick, Miriam; Smith, Stephanie; Thomas, Philippa; Bergamaschi, Fabio. "Gender Pay Gap". Information is Beautiful.

- ^ Suddath, Claire (2018-03-29). "New Numbers Show the Gender Pay Gap Is Real". Bloomberg.com. Retrieved 2020-09-26.

- ^ Titcomb, James (26 March 2018). "Google reveals UK gender pay gap of 17pc". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 2022-01-12 – via www.telegraph.co.uk.

- ^ "Microsoft publishes gender pay data for UK". Microsoft News Centre UK. Microsoft. 29 March 2018.

- ^ a b Leythienne, Denis; Ronkowski, Piotr (2018). A decomposition of the unadjusted gender pay gap using Structure of Earnings Survey data (PDF) (Statistical Working Paper). Population and social conditions. European Union. doi:10.2785/796328. ISBN 978-92-79-86877-1.

- ^ Blau, Francine D.; Kahn, Lawrence M. (November 2000). "Gender Differences in Pay". Journal of Economic Perspectives. 14 (4): 75–100. doi:10.1257/jep.14.4.75. S2CID 55685704.

- ^ "Women's earnings and employment by industry, 2009". United States Department of Labor. 16 February 2011. Retrieved 16 February 2020.

- ^ "Women in the Labor Force: A Databook" (PDF). United States Department of Labor. December 2010. Retrieved 16 February 2020.

- ^ Blackburn, Robert M.; Jarman, Jennifer (1997). "Social Research Update 16: Occupational Gender Segregation". sru.soc.surrey.ac.uk. Department of Sociology, University of Surrey. Retrieved 2019-01-16.

- ^ Eurofound (8 February 2017). "Segregation | Eurofound". www.eurofound.europa.eu. Retrieved 2019-01-16.

- ^ a b Folbre, Nancy; Gautham, Leila; Smith, Kristin (2022-04-25). "Gender Inequality, Bargaining, and Pay in Care Services in the United States". ILR Review. 76: 86–111. doi:10.1177/00197939221091157. ISSN 0019-7939. S2CID 253880358.

- ^ Gender inequality at work. Jacobs, Jerry A., 1955-. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications. 1995. ISBN 978-0803956964. OCLC 31013096.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b c Blau, Francine D.; Kahn, Lawrence M. (2007). "The Gender Pay Gap: Have Women Gone as Far as They Can?" (PDF). Academy of Management Perspectives. 21 (1): 7–23. doi:10.5465/AMP.2007.24286161. S2CID 152531847.

- ^ Rachel, Ngai, L.; Barbara, Petrongolo (2017). "Gender Gaps and the Rise of the Service Economy" (PDF). American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics. 9 (4): 1–44. doi:10.1257/mac.20150253. ISSN 1945-7707. S2CID 13478654.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Blau, Francine (2015). "Gender, Economics of". International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences. International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences (Second Edition). Elsevier. pp. 757–763. doi:10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.71051-8. ISBN 9780080970875.

- ^ Woolston, Chris (2019-01-22). "Scientists' salary data highlight US$18,000 gender pay gap". Nature. 565 (7740): 527. doi:10.1038/d41586-019-00220-y. PMID 30670866.

- ^ Cook, Jackie (February 22, 2021). "What Will it Take to Close the Gender Pay Gap for Good?". Morningstar.com. Retrieved 2021-02-24.

- ^ a b Thorbecke, Catherine (February 17, 2021). "Gender pay gap persists even at executive level, new study finds". ABC News. Retrieved 2021-02-23.

- ^ "Women of Color and the Gender Wage Gap". Center for American Progress. 14 April 2015. Retrieved 2022-10-10.

- ^ a b Misra, Joya; Murray-Close, Marta (November 1, 2014). "The Gender Wage Gap in the United States and Cross Nationally: The Gender Wage Gap in the United States and Cross Nationally". Sociology Compass. 8 (11): 1281–1295. doi:10.1111/soc4.12213.

- ^ Koch, Amanda J.; D'Mello, Susan D.; Sackett, Paul R. (2015). "A meta-analysis of gender stereotypes and bias in experimental simulations of employment decision making". Journal of Applied Psychology. 100 (1): 128–161. doi:10.1037/a0036734. ISSN 1939-1854. PMID 24865576.

- ^ Rich, Judith (October 2014). "What Do Field Experiments of Discrimination in Markets Tell Us? A Meta Analysis of Studies Conducted since 2000" (Discussion paper). IZA. Retrieved 2021-06-20.

- ^ Baert, Stijn (2018). "Hiring Discrimination: An Overview of (Almost) All Correspondence Experiments Since 2005". In S. Michael Gaddis (ed.). Audit Studies: Behind the Scenes with Theory, Method, and Nuance (PDF). Methodos Series. Cham: Springer International Publishing. pp. 63–77. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-71153-9_3. ISBN 978-3-319-71153-9. S2CID 126102523. Retrieved 2021-06-20.

- ^ Quadlin, Natasha (2018). "The Mark of a Woman's Record: Gender and Academic Performance in Hiring". American Sociological Review. 83 (2): 331–360. doi:10.1177/0003122418762291. S2CID 148955615.

- ^ Dubner, Stephen J.; Rosalsky, Greg (7 January 2016). "The True Story of the Gender Pay Gap (Ep. 232)". Freakonomics (Podcast). Retrieved 2019-03-10.

- ^ Block, Katharina; Croft, Alyssa; De Souza, Lucy; Schmader, Toni (2019-07-01). "Do people care if men don't care about caring? The asymmetry in support for changing gender roles". Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 83: 112–131. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2019.03.013. ISSN 0022-1031. S2CID 156010832. Retrieved 2021-06-27.

- ^ Sinclair, Samantha; Carlsson, Rickard (2021). "Reactions to affirmative action policies in hiring: Effects of framing and beneficiary gender". Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy. 21: 660–678. doi:10.1111/asap.12236. ISSN 1530-2415. S2CID 233795104.

- ^ Bütikofer, Aline; Jensen, Sissel; Salvanes, Kjell G. (2018). "The role of parenthood on the gender gap among top earners". European Economic Review. 109: 103–123. doi:10.1016/j.euroecorev.2018.05.008. hdl:11250/2497041. S2CID 54929106.

- ^ Kleven, Henrik; Landais, Camille; Søgaard, Jakob Egholt (January 2018). "Children and Gender Inequality: Evidence from Denmark". NBER Working Paper No. 24219. Working Paper Series. doi:10.3386/w24219.

- ^ a b c Misra, Joya; Strader, Eiko (2013). "GENDER PAY EQUITY IN ADVANCED COUNTRIES: THE ROLE OF PARENTHOOD AND POLICIES". Journal of International Affairs. 67 (1): 27–41. ISSN 0022-197X.

- ^ Maloney, Carolyn B. (April 2016). "Gender Pay Inequity: Consequences for Women, Families and the Economy" (PDF). Joint Economic Committee.

- ^ a b c d Bishu, Sebawit G.; Alkadry, Mohamad G. (2017). "A Systematic Review of the Gender Pay Gap and Factors That Predict It". Administration & Society. 49 (1): 8. doi:10.1177/0095399716636928. ISSN 0095-3997. S2CID 147452746.

- ^ "Analysis | Here are the facts behind that '79 cent' pay gap factoid". Washington Post.

- ^ Hipp, Lena (2019). "Do Hiring Practices Penalize Women and Benefit Men for Having Children? Experimental Evidence from Germany". European Sociological Review. 36 (2): 250–264. doi:10.1093/esr/jcz056. hdl:10419/205802.

- ^ Mari, Gabriele; Luijkx, Ruud (2020-01-25). "Gender, parenthood, and hiring intentions in sex-typical jobs: Insights from a survey experiment". Research in Social Stratification and Mobility. 65: 100464. doi:10.1016/j.rssm.2019.100464. ISSN 0276-5624.

- ^ Goldin, Claudia; Mitchell, Joshua (February 2017). "The New Life Cycle of Women's Employment: Disappearing Humps, Sagging Middles, Expanding Tops" (PDF). Journal of Economic Perspectives. 31 (1): 161–182. doi:10.1257/jep.31.1.161. ISSN 0895-3309. S2CID 157933907.

- ^ a b "Family and Medical Leave (FMLA) | U.S. Department of Labor". www.dol.gov. Retrieved 2021-10-25.

- ^ "Division of Temporary Disability and Family Leave Insurance | Maternity Coverage". www.myleavebenefits.nj.gov. Retrieved 2021-11-16.

- ^ https://www.nber.org/papers/w24219. DOI: 10.3386/w24219

- ^ Cech, Erin A.; Blair-Loy, Mary (2019-03-05). "The changing career trajectories of new parents in STEM". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 116 (10): 4182–4187. Bibcode:2019PNAS..116.4182C. doi:10.1073/pnas.1810862116. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 6410805. PMID 30782835.

- ^ Cech, Erin A.; Blair-Loy, Mary (2014-02-01). "Consequences of Flexibility Stigma Among Academic Scientists and Engineers". Work and Occupations. 41 (1): 86–110. doi:10.1177/0730888413515497. hdl:1911/75558. ISSN 0730-8884. S2CID 145478835.

- ^ Ferdous, Tahrima; Ali, Muhammad; French, Erica (2020-07-21). "Impact of Flexibility Stigma on Outcomes: Role of Flexible Work Practices Usage (Scimago Q1)". Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources. doi:10.1111/1744-7941.12275. S2CID 225195555.

- ^ Fox, Mary Frank; Fonseca, Carolyn; Bao, Jinghui (2011-10-01). "Work and family conflict in academic science: Patterns and predictors among women and men in research universities". Social Studies of Science. 41 (5): 715–735. doi:10.1177/0306312711417730. ISSN 0306-3127. PMID 22164721. S2CID 1034251.

- ^ Mooney Marin, Margaret; Fan, Pi-Ling (1997). "The Gender Gap in Earnings at Career Entry". American Sociological Review. 62 (4): 589–591. doi:10.2307/2657428. JSTOR 2657428.

- ^ Jacobs, Jerry (1989). Revolving Doors: Sex Segregation and Women's Careers. Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804714891.

- ^ Reskin, Barbara (1993). "Sex Segregation in the Workplace". Annual Review of Sociology. 19: 241–270. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.19.1.241. JSTOR 2083388.

- ^ Macpherson, David A.; Hirsch, Barry T. (1995). "Wages and Gender Composition: Why do Women's Jobs Pay Less?". Journal of Labor Economics. 13 (3): 426–471. doi:10.1086/298381. JSTOR 2535151. S2CID 18614879.

- ^ Ruth Simpson (2006). "Men in non-traditional occupations: Career entry, career orientation and experience of role strain". Human Resource Management International Digest. 14 (3). CiteSeerX 10.1.1.426.5021. doi:10.1108/hrmid.2006.04414cad.007.

- ^ a b Martell, Richard F.; et al. (1998). "Sex Stereotyping In The Executive Suite: 'Much Ado About Something'". Journal of Social Behavior & Personality. 13 (1): 127–138.

- ^ Frankforter, Steven A. (1996). "The Progression Of Women Beyond The Glass Ceiling". Journal of Social Behavior & Personality. 11 (5): 121–132.

- ^ a b c Tharenou, Phyllis (2012-10-07). "The Work of Feminists is Not Yet Done: The Gender Pay Gap—a Stubborn Anachronism". Sex Roles. 68 (3–4): 198–206. doi:10.1007/s11199-012-0221-8. ISSN 0360-0025. S2CID 144449088.

- ^ Bryant, Molly (2012). "Gender Pay Gap". Iowa State University Digital Repository.

- ^ "Why Women Volunteer for Tasks That Don't Lead to Promotions". Harvard Business Review. 2018-07-16. Retrieved 2018-07-23.

- ^ IMF, “Is Technology Widening the Gender Gap? Automation and the Future of Female Employment?"

- ^ a b c d Miller, Claire Cain (2019-04-26). "Women Did Everything Right. Then Work Got 'Greedy.' - How America's obsession with long hours has widened the gender gap". New York Times.

- ^ a b National Centre for Social and Economic Modelling (2009), "The impact of a sustained gender wage gap on the economy" (PDF), Report to the Office for Women, Department of Families, Community Services, Housing and Indigenous Affairs: v–vi, archived from the original (PDF) on December 1, 2010

- ^ "Women in their 20s earn more than men of same age, study finds". American Association of University Women.

- ^ Laura Bassett (October 24, 2012) "Closing The Gender Wage Gap Would Create 'Huge' Economic Stimulus, Economists Say" Huffington Post

- ^ Christianne Corbett; Catherine Hill (October 2012). "Graduating to a Pay Gap: The Earnings of Women and Men One Year after College Graduation" (PDF). Washington, DC: American Association of University Women.

- ^ https://iwpr.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Economic-Impact-of-Equal-Pay-by-State_FINAL.pdf

- ^ European Commission (March 4, 2011). "Closing the gender pay gap". Archived from the original on March 6, 2011.

- ^ "World Bank World Development Report 2019: The Changing Nature of Work" (PDF).

- ^ Chiappori, Pierre-André (1997). "Introducing Household Production in Collective Models of Labor Supply". Journal of Political Economy. 105: 191–209. doi:10.1086/262071. S2CID 154329447.

- ^ Gelles, Richard J. (1976). "Abused Wives: Why do They Stay". Journal of Marriage and Family. 38 (4): 659–668. doi:10.2307/350685. JSTOR 350685.

- ^ Lundberg, Shelly; Pollak, Robert A. (1993). "Separate Spheres Bargaining and the Marriage Market". Journal of Political Economy. 101 (6): 988–1010. doi:10.1086/261912. JSTOR 2138569. S2CID 154525602.

- ^ Aizer, Anna. 2010. "The Gender Wage Gap and Domestic Violence." American Economic Review, 100 (4): 1847-59.

- ^ "The Economic Cost of Intimate Partner Violence, Sexual Assault, and Stalking - IWPR". 14 August 2017.

- ^ Currie, J.; Widom, C. S. (2010). "Long-Term Consequences of Child Abuse and Neglect on Adult Economic Well-Being". Child Maltreatment. 15 (2): 111–120. doi:10.1177/1077559509355316. PMC 3571659. PMID 20425881.

- ^ Inman, Phillip (2023-10-09). "Claudia Goldin wins Nobel economics prize for work on gender pay gap". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2023-10-11.

- ^ "Nobel economics prize awarded to Claudia Goldin for work on women's pay". BBC News. 2023-10-09. Retrieved 2023-10-11.

- ^ Ahlander, Johan; Johnson, Simon (2023-10-09). "Claudia Goldin wins Nobel economics prize for work on gender gap". Reuters. Retrieved 2023-10-11.

She has attributed the gap to factors ranging from outright discrimination to phenomena such as "greedy work", a term she coined for jobs that pay disproportionately more per hour when someone works longer or has less control over those hours, effectively penalising women who need to seek flexible labour.

- ^ Becker, Gary (1993). "Nobel Lecture: The Economic Way of Looking at Behavior". Journal of Political Economy. 101 (3): 387–389. doi:10.1086/261880. JSTOR 2138769. S2CID 15060650.

- ^ Cain, Glen G. (1986). "The Economic Analysis of Labor Market Discrimination: A Survey". In Ashenfelter, Orley; Laynard, R. (eds.). Handbook of Labor Economics: Volume I. Elsevier. pp. 710–712. ISBN 9780444534521.

- ^ Ransom, Michael; Oaxaca, Ronald L. (January 2005). "Intrafirm Mobility and Sex Differences in Pay" (PDF). Industrial and Labor Relations Review. 58 (2): 219–237. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.224.3070. doi:10.1177/001979390505800203. hdl:10419/20633. JSTOR 30038574. S2CID 153480792.

- ^ Tharenou, Phyllis (7 October 2012). "The Work of Feminists is Not Yet Done: The Gender Pay Gap—a Stubborn Anachronism". Sex Roles. 68 (3–4): 198–206. doi:10.1007/s11199-012-0221-8. S2CID 144449088.

- ^ a b OECD. OECD Employment Outlook – 2008 Edition Summary in English. OECD, Paris, 2008, p. 3–4.

- ^ OECD. OECD Employment Outlook. Chapter 3: The Price of Prejudice: Labour Market Discrimination on the Grounds of Gender and Ethnicity. OECD, Paris, 2008.

- ^ U.S. Government Accountability Office. Women's Earnings: Federal Agencies Should Better Monitor Their Performance in Enforcing Anti-Discrimination Laws. Retrieved on April 1, 2011.

- ^ U.S. Government Accountability Office. Report Women's Earnings: Federal Agencies Should Better Monitor Their Performance in Enforcing Anti-Discrimination Laws.

- ^ "Statement of Jocelyn Frye". www.eeoc.gov. Retrieved 2018-07-01.

- ^ "New Law In Iceland Aims At Reducing Country's Gender Pay Gap". NPR.org. Retrieved 2018-07-01.

- ^ a b c "The Gender Earnings Gap in the Gig Economy: Evidence from over a Million Rideshare Drivers" (PDF). Stanford University. January 2018. Retrieved 8 March 2018.

- ^ a b "Earning more is never a simple choice for women". Financial Times. 6 March 2018. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ^ a b "Pay Disparity Between Men and Women Even Exists in the Gig Economy". Fortune. 6 February 2018. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ^ Rosalsky, Greg. "What Can Uber Teach Us About the Gender Pay Gap? (Ep. 317)". Freakonomics. Retrieved 2021-06-28.

- ^ Cook, Cody; Diamond, Rebecca; Hall, Jonathan V; List, John A; Oyer, Paul. "The Gender Earnings Gap in the Gig Economy: Evidence from over a Million Rideshare Drivers" (PDF): 72.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ OECD Employment Outlook 2021, OECD, 2021, doi:10.1787/5a700c4b-en, ISBN 9789264708723, S2CID 243542731

- ^ "State of the World's Mothers 2007" (PDF). Save the Children. p. 57. Retrieved 16 February 2020.

- ^ Schwab, Klaus; et al. (2015). "The Global Gender Gap Report 2015" (PDF). World Economic Forum. pp. 8–9. Retrieved 29 September 2016.

- ^ "WGEA Data Explorer". WGEA Data Explorer.

- ^ "Frequently asked questions about pay equity". Department of Commerce. Archived from the original on April 22, 2011. Retrieved May 6, 2011.

- ^ a b "Australia's Gender Pay Gap Statistics 2021". 2021.

- ^ Watson, Ian (2010). "Decomposing the Gender Pay Gap in the Australian Managerial Labour Market" (PDF). Australian Journal of Labour Economics. 13 (1). Macquarie University: 49–79. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 6, 2011.

- ^ "Gender Differences in Employment and Why They Matter". World Development Report 2012. The World Bank. 2011-09-12. pp. 198–253. doi:10.1596/9780821388105_ch5. ISBN 9780821388105.

- ^ Derocher, John. "Student". Global Gender Gap Report 2018. World Economic Forum. Retrieved December 5, 2019.

- ^ "The Global Gender Gap Report 2017". World Economic Forum. Retrieved 2018-07-01.

- ^ Manhaes, Gisele Flores Caldas. "IBGE - Agência de Notícias". IBGE - Agência de Notícias (in Portuguese). Retrieved 2018-04-12.

- ^ Rodrigues, Joao Carlos de Melo Miranda. "IBGE - Agência de Notícias". IBGE - Agência de Notícias (in Portuguese). Retrieved 2018-04-12.