Celivarone

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

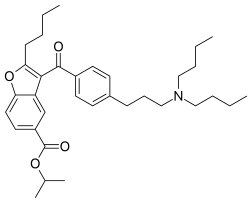

Isopropyl 2-butyl-3-{4-[3-(dibutylamino)propyl]benzoyl}-1-benzofuran-5-carboxylate

| |

| Other names

SSR149744C

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.211.855 |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C34H47NO4 | |

| Molar mass | 533.753 g·mol−1 |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Celivarone is an experimental drug being tested for use in pharmacological antiarrhythmic therapy.[1] Cardiac arrhythmia is any abnormality in the electrical activity of the heart. Arrhythmias range from mild to severe, sometimes causing symptoms like palpitations, dizziness, fainting, and even death.[2] They can manifest as slow (bradycardia) or fast (tachycardia) heart rate, and may have a regular or irregular rhythm.[2]

Molecular causes of cardiac arrhythmias

The causes of cardiac arrhythmias are numerous, from structural changes in the conduction system (the sinoatrial and atrioventricular nodes, or His-Purkinje system) and cardiac muscle,[2] to mutations in genes coding for ion channels of the heart. Movement of ions, particularly Na+, Ca2+ and K+, causes depolarizations of cell membranes in node cells, which are then transmitted to cardiac muscle cells to induce contraction. After depolarization, the ions are moved back to their original locations, leading to repolarization of the membrane and relaxation.[3] Disruptions in ion flow affect the heart’s ability to contract by altering the resting membrane potential, affecting the cell’s ability to conduct or transmit an action potential (AP), or by affecting the rate or force of contraction.[3]

The specific molecular changes involved in arrhythmias depend on the nature of the problem. Ion channel mutations can alter protein conformation, and so change the amount of current flowing through these channels. Due to changes in amino acids and binding domains, mutations may also affect the ability of these channels to respond to physiological changes in cardiac demand.[4] Mutations resulting in loss of function of K+ channels can result in delayed repolarization of the cardiac muscle cells. Similarly, gain of function of Na+ and Ca2+ channels results in delayed repolarization, and Ca2+ overload causing increased Ca2+ binding to cardiac troponin C, more actin-myosin interactions and causing an increased contractility, respectively.[3] Mutations cause many arrhythmic conditions, including atrial fibrillation (AF), atrial flutter (AFl), and ventricular fibrillation (V-Fib).[5][6][7] Arrhythmias can also be induced by altered activity of the vagus nerve and activation of β1 adrenergic receptors.[8]

Mechanism of action

Celivarone is a non-iodinated benzofuran derivative, structurally related to amiodarone, a drug commonly used to treat arrhythmias.[1] Celivarone has potential as an antiarrhythmic agent, attributable to its multifactorial mechanism of action; blocking Na+, L-type Ca2+ and many types of K+ channels (IKr, IKs, IKACh and IKv1.5), as well as inhibiting β1 receptors, all in dose-dependent manners.[1][9] The mechanisms by which celivarone modifies ion flow through these channels is unknown, but hearts demonstrate longer PQ intervals and decreased cell shortening, indicative of blocked L-type Ca2+ channels, depressed maximum current with each action potential with no change in the resting membrane potential, caused by blocked Na+ channels, and longer action potential duration due to K+ channel blocks.[1][10] Celivarone is therefore described as having class I, II, III, and IV antiarrhythmic properties.[1][10]

Indications for use

Celivarone displays some atrial selectivity, suggesting it may be most effective at targeting atrial arrhythmias like atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter.[1][9][10][11] These conditions are characterized by rapid atrial rates, 400–600 bpm for atrial fibrillation and 150–300 bpm for atrial flutter.[2] Studies have shown celivarone is capable of cardioversion, maintaining normal sinus cardiac rhythms[1][10] , being effective in hypokalemic, vasotonic, and stretch-induced atrial fibrillation, as well as ischemic and reperfusion ventricular fibrillation.[10] Since it affects multiple ion channels, it also shows promise in treating genetic forms of arrhythmia caused by several ion channel mutations.[1][10]

Future research

Celivarone may be an effective antihypertensive therapy, as it inhibits both angiotensin II and phenylephrine induced hypertension in dogs, despite having no affinity for these receptors.[1] Atrial fibrillation is especially common in hypertensive adults[2] so a single drug to combat both problems is desirable. The non-iodinated nature of celivarone means that the harmful side-effects on the thyroid commonly seen with amiodarone therapy are eliminated, making the drug an attractive alternative.[1][10] Higher oral bioavailability, shorter duration of action, and lower accumulation in body tissues are also benefits of celivarone.[1][10] Presently, two studies are underway to determine if the effects observed in the animal models are reproducible in a human population.[12][13]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Gautier, P; Guillemare, E; Djandjighian, L; Marion, A; Planchenault, J; Bernhart, C; Herbert, JM; Nisato, D (August 2004). "In vivo and in vitro Characterization of the Novel Antiarrhythmic Agent SSR149744C: Electrophysiological, Anti-adrenergic, and Anti-angiotensin II effects". Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology. 44 (2): 244–57. doi:10.1097/00005344-200408000-00015. PMID 15243307.

- ^ a b c d e Hoffman, BF (September 1966). "Physiological Basis of Cardiac Arrhythmias. II". Modern Concepts of Cardiovascular Disease. 35 (9): 107–10. PMID 5945668.

- ^ a b c Chapman, RA (January 1980). "Excitation-contraction Coupling in Cardiac Muscle". Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology. 35: 1–52. doi:10.1016/0079-6107(80)90002-4.

- ^ Keating, MT; Sanguinetti, MC (June 1996). "Pathophysiology of Ion Channel Mutations". Current Opinion in Genetics & Development. 6 (3): 326–333. doi:10.1016/S0959-437X(96)80010-4. PMID 8791523.

- ^ Wang, Q; Curran, ME; Splawski, I; Burn, TC; Millholland, JM; VanRaay, TJ; Shen, J; Timothy, KW; Vincent, GM; de Jager, T; Schwartz, PJ; Towbin, JA; Moss, AJ; Atkinson, DL; Landes, GM; Connors, TD; Keating, MT (January 1996). "Positional Cloning of a Novel Potassium Channel Gene: KVLQT1 Mutations Cause Cardiac Arrhythmias". Nature Genetics. 12 (1): 17–23. doi:10.1038/ng0196-17. PMID 8528244.

- ^ Abbott, GW; Sesti, F; Splawski, I; Buck, ME; Lehmann, MH; Timothy, KW; Keating, MT; Goldstein, SAN (April 1999). "MiRP1 Forms IKr Potassium Channels with hERG and Is Associated with Cardiac Arrhythmia". Cell. 97 (2): 175–187. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80728-X. PMID 10219239.

- ^ Priori, SG; Napolitano, C; Tiso, N; Memmi, M; Vignati, G; Bloise, R; Sorrentino, V; Danieli, GA (16 January 2001). "Mutations in the Cardiac Ryanodine Receptor Gene (hRyR2) Underlie Catecholaminergic Polymorphic Ventricular Tachycardia". Circulation. 103 (2): 196–200. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.103.2.196. PMID 11208676.

- ^ Abildskov, JA (August 1991). "The Sympathetic Imbalance Hypothesis of QT Interval Prolongation". Journal of Cardiovascular Electrophysiology. 2 (4): 355–359. doi:10.1111/j.1540-8167.1991.tb01332.x.

- ^ a b Kowey, PR; Aliot, EM; Cappucci, A; Connolly, SJ; Crijns, HJ; Hohnloser, SH; Kulakowski, P; Roy, D; Radzik, D; Singh, BN (2007). "Placebo-controlled, Double-blind Dose-ranging Study of the Efficacy and Safety of SSR149744C in Patients with Recent Atrial Fibrillation/Flutter [abstract]". Heart Rhythm. 4 (Suppl): S72. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2007.03.018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Gautier, P; Serre, M; Cosnier-Pucheu, S; Djandjighian, L; Roccon, A; Herbert, JM; Nisato, D (February 2005). "In vivo and in vitro Antiarrhythmic Effects of SSR149744C in Animal Models of Atrial Fibrillation and Ventricular Arrhythmias". Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology. 45 (2): 125–135. doi:10.1097/01.fjc.0000151899.03379.76. PMID 15654261.

- ^ Cosnier-pucheu, S; Roccon, A; Rizzoli, G; Gayraud, R; Guiraudou, P; Briand, D; Roque, C; Gautier, P; Herbert, JM; Nisato, D (June 2003). "301 SSR149744, a New Antiarrhythmic Drug, Prevents Experimental Induced Atrial Fibrillation". European Journal of Heart Failure Supplements. 2 (1): 53–54. doi:10.1016/S1567-4215(03)90164-0.

- ^ "Double Blind Placebo Controlled Dose Ranging Study of the Efficacy and Safety of SSR149744C 300 or 600 mg for the Conversion of Atrial Fibrillation/Flutter (CORYFEE)". ClinicalTrials.gov. Retrieved 6 January 2016.

- ^ "Dose Ranging Study of Celivarone with Amiodarone as Calibrator for the Prevention of Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator (ICD) Interventions or Death (ALPHEE)". ClinicalTrials.gov. Retrieved 6 January 2016.