Russians

Russian: Русские | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Total population | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 134 million[1] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

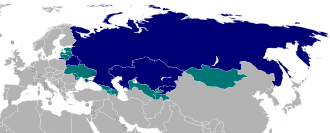

| Regions with significant populations | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Diaspora | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 7,170,000 (2018) including Crimea[3] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3,644,529 (2016)[4] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3,500,000 (including Russian Jews and Russian Germans) 1,213,000 (excluding ethnic German repatriates)[5][6] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3,072,756 (2009) (including Russian Jews and Russian Germans)[7] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 938,500 (2011) (including Russian Jews)[8] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 809,530 (2019)[9] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 785,084 (2009)[10] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 622,445 (2016) (Russian ancestry, excluding Russian Germans)[11] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Languages | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Russian | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Predominantly (Russian Orthodox Church) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Related ethnic groups | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other East Slavs (Belarusians, Ukrainians and Rusyns),[43] Eastern South Slavs (Bulgarians, Serbs, Macedonians, and Montenegrins) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Russians (Russian: русские) are an East Slavic ethnic group native to Eastern Europe, who share a common Russian ancestry, culture, and history. Russian, the most spoken Slavic language, is the shared mother tongue of the Russians; and Orthodox Christianity is their historical religion since the 11th century. They are the largest Slavic nation, as well as the largest European nation.

The Russians were formed from East Slavic tribes, and their cultural ancestry is based in Kievan Rus'. The Russian word for the Russians is derived from the people of Rus' and the territory of Rus'. The Russians share many historical and cultural traits with other European peoples, and especially with other East Slavic ethnic groups, specifically Belarusians and Ukrainians.

Of the total 258 million speakers of Russian in the world,[44] roughly 134 million of them are ethnic Russians.[45] The vast majority of Russians live in native Russia, but notable minorities are scattered throughout other post-Soviet states such as Belarus, Kazakhstan, Moldova, Ukraine and the Baltic states. A large Russian diaspora (sometimes including Russian-speaking non-Russians), estimated at over 20-30 million people, has developed all over the world, with notable numbers in the United States, Germany, Brazil, and Canada.

Ethnonym

The standard way to refer to citizens of Russia is "Russians" in English.[46] There are two Russian words which are commonly translated into English as "Russians". One is "русские" (russkiye), which most often means "ethnic Russians". Another is "россияне" (rossiyane), which means "Russian citizens", regardless of ethnicity.[47]

The name of the Russians derives from the Rus' people. It is not clear from whom the in West called Rus' people descended.[48] The most prevalent theory in Germanic-speaking countries is, that the name Rus', like the Finnish name for Sweden (Ruotsi), is derived from an Old Norse term for "the men who row" (rods-) as rowing was the main method of navigating the rivers of Eastern Europe. It could be associated to the Swedish coastal area of Roslagen (Rus-law) or Roden, as it was known in earlier times.[49][50] The name Rus' would have the same origin as the Finnish and Estonian names for Sweden: Ruotsi and Rootsi.[51] Although Russian history and culture is shaped also by Germanic people such as the Vikings, there are also theories that Rus' is of a non-Germanic origin. According to the historian Lydia Groth, Roslagen in IX—XII centuries was unsuitable for life, as it was under water at a depth of 6–7 meters. Furthermore, the name Roslagen was first documented only in 1493.[52][53] According to other theories the name Rus' is derived from Proto-Slavic *roud-s-ь ( from *rъd-/*roud-/*rуd- root), connected with red color (of hair)[54] or from Indo-Iranian (ruxs/roxs — «light-colored», «bright»).[55] There are also other lingual links to more southern peoples in Eurasia like the city Ruse in Bulgaria or the Elbrus in the Russian Caucasus. The word Rus' is also connected to the river Ros in Ukraine.

Until the 1917 revolution, Russian authorities never specifically called the people "Russians", referring to them instead as "Great Russians," a part of "Russians" (all the East Slavs).

History

Ancient history

There are indications that today's Russia is the original home of the Russian ethnic group and various Slavic tribes.[56] The modern Russians were formed i.a. from two groups of East Slavic tribes: Northern and Southern. These tribes included the Krivichs, Ilmen Slavs, Radimichs, Vyatiches and Severians. Genetic studies show that Russians are closest to Belarusians, Ukrainians, Poles, and other Slavs.[43] Some ethnographers, like Zelenin, affirm that Russians overall are more similar to Belarusians and to Ukrainians than southern Russians are to northern Russians. Russians in some parts northwestern Russia share moderate genetic similarities with Baltic Finnic peoples,[43][57] who lived in modern northwestern-central Russia, and were partly assimilated by East Slavs as they migrated northeastwards. The territory of Russia has been inhabited since 2nd Millennium BCE by Indo-European, Ural-Altaic, and various other peoples; however, not much is known about them.[58] Slavic people are native to the western part of Russia.[59] Outside archaeological remains, little is known about the predecessors to Russians in general prior to 859 AD, when the Primary Chronicle starts its records.[60] By 600 AD, the Slavs are believed to have split linguistically into southern, western, and eastern branches.

The eastern branch settled between the Southern Bug and the Dnieper rivers in present-day Ukraine; from the 1st century AD through almost the turn of the millennium, they spread peacefully northward to the Baltic region, forming the Dregovich, Radimich and Vyatich Slavic tribes on the Baltic substratum. They developed some changed language features, such as vowel reduction. Later, both Belarusians and South Russians emerged from this ethnic linguistic ground or family.[61]

From the 6th century onward, another group of Slavs moved from Pomerania to the northeast of the Baltic Sea, where they encountered the Varangians of the Rus' Khaganate and established the important regional center of Novgorod. The same Slavic ethnic population also settled the present-day Tver Oblast and the region of Beloozero. With the Uralic substratum, they formed the tribes of the Krivichs and of the Ilmen Slavs.

Medieval history

The traditional start-date of specifically Russian history is the establishment of the Rus' state in the north in 862 ruled by Vikings.[62] Staraya Ladoga and Novgorod became the first major cities of the new union of immigrants from Scandinavia with the Slavs and Finno-Ugrians. In 882 Prince Oleg of Novgorod seized Kiev, thereby uniting the northern and southern lands of the Eastern Slavs under one authority. The state adopted Christianity from the Byzantine Empire in 988, beginning the synthesis of Byzantine and Slavic cultures that defined Orthodox Slavic culture for the next millennium. Kievan Rus' ultimately disintegrated as a state because of in-fighting between members of the princely family that ruled it collectively.

After the 13th century, Moscow became a political and cultural center. Moscow has become a center for the unification of Russian lands. By the end of the 15th century, Moscow united the northeastern and northwestern Russian principalities, in 1480 finally overthrew the Mongol yoke. The territories of the Grand Duchy of Moscow became the Tsardom of Russia in 1547.

Modern history

In 1721 Tsar Peter the Great renamed his state as the Russian Empire, hoping to associate it with historical and cultural achievements of ancient Rus' – in contrast to his policies oriented towards Western Europe. The state now extended from the eastern borders of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth to the Pacific Ocean, and became a great power; and one of the most powerful states in Europe after the victory over Napoleon. Peasant revolts were common, and all were fiercely suppressed. The Emperor Alexander II abolished Russian serfdom in 1861, but the peasants fared poorly and revolutionary pressures grew. In the following decades, reform efforts such as the Stolypin reforms of 1906–1914, the constitution of 1906, and the State Duma (1906–1917) attempted to open and liberalize the economy and political system, but the Emperors refused to relinquish autocratic rule and resisted sharing their power.

A combination of economic breakdown, war-weariness, and discontent with the autocratic system of government triggered revolution in Russia in 1917. The overthrow of the monarchy initially brought into office a coalition of liberals and moderate socialists, but their failed policies led to seizure of power by the communist Bolsheviks on 25 October 1917 (7 November New Style). In 1922, Soviet Russia, along with Soviet Ukraine, Soviet Belarus, and the Transcaucasian SFSR signed the Treaty on the Creation of the USSR, officially merging all four republics to form the Soviet Union as a country. Between 1922 and 1991 the history of Russia became essentially the history of the Soviet Union, effectively an ideologically-based state roughly conterminous with the Russian Empire before the 1918 Treaty of Brest-Litovsk. From its first years, government in the Soviet Union-based itself on the one-party rule of the Communists, as the Bolsheviks called themselves, beginning in March 1918. The approach to the building of socialism, however, varied over different periods in Soviet history: from the mixed economy and diverse society and culture of the 1920s through the command economy and repressions of the Joseph Stalin era to the "era of stagnation" from the 1960s to the 1980s. During this period, Soviet Union won the World War II, becoming a superpower opposing Western countries in the Cold War. The USSR was successful in the space program, launching the first man into space.

By the mid-1980s, with the weaknesses of Soviet economic and political structures becoming acute, Mikhail Gorbachev embarked on major reforms, which eventually led to the overthrowal of the communist party and the breakup of the USSR, leaving Russia again on its own and marking the start of the history of post-Soviet Russia. The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic renamed itself as the Russian Federation and became one of the several successors to the Soviet Union.

Geographic distribution

Ethnic Russians historically migrated throughout the area of former Russian Empire and Soviet Union, sometimes encouraged to re-settle in borderlands by the Tsarist and later Soviet government.[63] On some occasions, ethnic Russian communities, such as Lipovans who settled in the Danube delta or Doukhobors in Canada, emigrated as religious dissidents fleeing the central authority.

After the Russian Revolution and Russian Civil War starting in 1917, many Russians were forced to leave their homeland fleeing the Bolshevik regime, and millions became refugees. Many white émigrés were participants in the White movement, although the term is broadly applied to anyone who may have left the country due to the change in regime.

After the Dissolution of the Soviet Union an estimated 25 million Russians began living outside of the Russian Federation, most of them in the former Soviet Republics. In Ukraine (about 8 million), Kazakhstan (about 3.8 million), Belarus (about 785,000), Latvia (about 520,000) with the most Russian settlement out of the Baltic States which includes Lithuania and Estonia, Uzbekistan (about 650,000) and Kyrgyzstan (about 419,000). In Moldova, the Transnistria region (where 30.4% of the population is Russian) broke away from government control amid fears the country would soon reunite with Romania.

There are also small Russian communities in the Balkans, including Lipovans in the Danube delta,[64] Central European nations such as Germany and Poland, as well Russians settled in China, Japan, South Korea, Mexico, Brazil, Argentina and Australia. These communities may identify themselves either as Russians or citizens of these countries, or both, to varying degrees.

Significant numbers of Russians emigrated to Canada, Australia and the United States. Brighton Beach, Brooklyn and South Beach, Staten Island in New York City is an example of a large community of recent Russian and Russian Jewish immigrants. Other examples are Sunny Isles Beach, a northern suburb of Miami, and in West Hollywood of the Los Angeles area.

After the Russian Revolution in 1917, many Russians who were identified with the White army moved to China — most of them settling in Harbin and Shanghai.[65] By the 1930s, Harbin had 100,000 Russians. Many of these Russians had to move back to the Soviet Union after World War II. Today, a large group of people in northern China can still speak Russian as a second language. And Russians (eluosizu) are one of the 56 ethnic groups officially recognized by the People's Republic of China (as the Russ); there are approximately 15,600 Russian Chinese living mostly in northern Xinjiang, and also in Inner Mongolia and Heilongjiang.

Language

Russian (русский язык, tr. russkiy yazyk) is the most spoken native language in Europe, the most geographically widespread language of Eurasia, as well as the most widely spoken Slavic language in the world.[66] It belongs to the Indo-European language family, and is one of the living members of the East Slavic languages.

Russian is the second-most used language on the Internet after English,[67] one of two official languages aboard the International Space Station,[68] and is one of the six official languages of the United Nations.[69]

Culture

Literature

Russian literature is considered to be among the most influential and developed in the world, with some of the most famous literary works belonging to it.[70] Russia's literary history dates back to the 10th century; in the 18th century its development was boosted by the works of Mikhail Lomonosov and Denis Fonvizin, and by the early 19th century a modern native tradition had emerged, producing some of the greatest writers of all time. This period and the Golden Age of Russian Poetry began with Alexander Pushkin, considered to be the founder of modern Russian literature and often described as the "Russian Shakespeare" or the "Russian Goethe".[71] It continued in the 19th century with the poetry of Mikhail Lermontov and Nikolay Nekrasov, dramas of Aleksandr Ostrovsky and Anton Chekhov, and the prose of Nikolai Gogol, Ivan Turgenev, Leo Tolstoy, Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin, Ivan Goncharov, Aleksey Pisemsky and Nikolai Leskov. Tolstoy and Dostoevsky in particular were titanic figures, to the point that many literary critics have described one or the other as the greatest novelist ever.[72][73]

By the 1880s Russian literature had begun to change. The age of the great novelists was over and short fiction and poetry became the dominant genres of Russian literature for the next several decades, which later became known as the Silver Age of Russian Poetry. Previously dominated by realism, Russian literature came under strong influence of symbolism in the years between 1893 and 1914. Leading writers of this age include Valery Bryusov, Andrei Bely, Vyacheslav Ivanov, Aleksandr Blok, Nikolay Gumilev, Dmitry Merezhkovsky, Fyodor Sologub, Anna Akhmatova, Osip Mandelstam, Marina Tsvetaeva, Leonid Andreyev, Ivan Bunin, and Maxim Gorky.

Following the Russian Revolution of 1917 and the ensuing civil war, Russian cultural life was left in chaos. Some prominent writers, like Ivan Bunin and Vladimir Nabokov left the country, while a new generation of talented writers joined together in different organizations with the aim of creating a new and distinctive working-class culture appropriate for the new state, the Soviet Union. Throughout the 1920s writers enjoyed broad tolerance. In the 1930s censorship over literature was tightened in line with Joseph Stalin's policy of socialist realism. After his death the restrictions on literature were eased, and by the 1970s and 1980s, writers were increasingly ignoring official guidelines. The leading authors of the Soviet era included Yevgeny Zamiatin, Isaac Babel, Vladimir Mayakovsky, Ilf and Petrov, Yury Olesha, Mikhail Bulgakov, Boris Pasternak, Mikhail Sholokhov, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, Yevgeny Yevtushenko, and Andrey Voznesensky.

The Soviet era was also the golden age of Russian science fiction, that was initially inspired by western authors and enthusiastically developed with the success of Soviet space program. Authors like Arkady and Boris Strugatsky, Kir Bulychev, Ivan Yefremov, Alexander Belyaev enjoyed mainstream popularity at the time. An important theme of Russian literature has always been the Russian soul.

| Pushkin (1799–1837) |

Gogol (1809–1852) |

Turgenev (1818–1883) |

Dostoevsky (1821–1881) |

Tolstoy (1828–1910) |

Chekhov (1860–1904) |

Bulgakov (1891–1940) |

Akhmatova (1889–1966) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

File:Bułhakow.jpg |

|

Philosophy

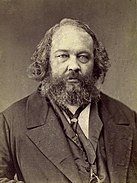

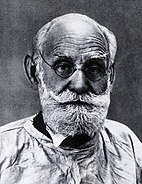

Some Russian writers, like Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky, are known also as philosophers, while many more authors are known primarily for their philosophical works. Russian philosophy blossomed since the 19th century, when it was defined initially by the opposition of Westernizers, advocating Russia's following the Western political and economical models, and Slavophiles, insisting on developing Russia as a unique civilization. The latter group includes Nikolai Danilevsky and Konstantin Leontiev, the early founders of Eurasianism.

In its further developments, Russian philosophy was always marked by a deep connection to literature and interest in creativity, society, politics and nationalism; cosmos and religion were other primary subjects. Notable philosophers of the late 19th and early 20th centuries include Vladimir Solovyov, Sergei Bulgakov, Pavel Florensky, Nikolai Berdyaev, Vladimir Lossky and Vladimir Vernadsky. In the 20th century Russian philosophy became dominated by Marxism.

| Bakunin (1814–1876) |

Kropotkin (1842–1921) |

Solovyov (1853–1900) |

Shestov (1866–1938) |

Berdyaev (1874–1948) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

Science

At the start of the 18th century the reforms of Peter the Great (the founder of Russian Academy of Sciences and Saint Petersburg State University) and the work of such champions as polymath Mikhail Lomonosov (the founder of Moscow State University) gave a great boost for development of science, engineering and innovation in Russia. In the 19th and 20th centuries Russia produced a large number of great scientists and inventors.

Nikolai Lobachevsky, a Copernicus of Geometry, developed the non-Euclidean geometry. Dmitry Mendeleev invented the Periodic table, the main framework of the modern chemistry. Nikolay Benardos introduced the arc welding, further developed by Nikolay Slavyanov, Konstantin Khrenov and other Russian engineers. Gleb Kotelnikov invented the knapsack parachute, while Evgeniy Chertovsky introduced the pressure suit. Pavel Yablochkov and Alexander Lodygin were great pioneers of electrical engineering and inventors of early electric lamps.

Alexander Popov was among the inventors of radio, while Nikolai Basov and Alexander Prokhorov were co-inventors of lasers and masers. Igor Tamm, Andrei Sakharov and Lev Artsimovich developed the idea of tokamak for controlled nuclear fusion and created its first prototype, which finally led to the modern ITER project. Many famous Russian scientists and inventors were émigrés, like Igor Sikorsky and Vladimir Zworykin, and many foreign ones worked in Russia for a long time, like Leonard Euler and Alfred Nobel.

The greatest Russian successes are in the field of space technology and space exploration. Konstantin Tsiolkovsky was the father of theoretical astronautics.[74] His works had inspired leading Soviet rocket engineers such as Sergei Korolev, Valentin Glushko, and many others that contributed to the success of the Soviet space program at early stages of the Space Race and beyond.

In 1957 the first Earth-orbiting artificial satellite, Sputnik 1, was launched; in 1961 on 12 April the first human trip into space was successfully made by Yury Gagarin; and many other Soviet and Russian space exploration records ensued, including the first spacewalk performed by Alexei Leonov, the first space exploration rover Lunokhod-1 and the first space station Salyut 1. Nowadays Russia is the largest satellite launcher[75][76] and the only provider of transport for space tourism services until May 2020.

Other technologies, where Russia historically leads, include nuclear technology, aircraft production and arms industry. The creation of the first nuclear power plant along with the first nuclear reactors for submarines and surface ships was directed by Igor Kurchatov. NS Lenin was the world's first nuclear-powered surface ship as well as the first nuclear-powered civilian vessel, and NS Arktika became the first surface ship to reach the North Pole.

A number of prominent Soviet aerospace engineers, inspired by the theoretical works of Nikolai Zhukovsky, supervised the creation of many dozens of models of military and civilian aircraft and founded a number of KBs (Construction Bureaus) that now constitute the bulk of Russian United Aircraft Corporation. Famous Russian airplanes include the first supersonic passenger jet Tupolev Tu-144 by Alexei Tupolev, MiG fighter aircraft series by Artem Mikoyan and Mikhail Gurevich, and Su series by Pavel Sukhoi and his followers. MiG-15 is the world's most produced jet aircraft in history, while MiG-21 is most produced supersonic aircraft. During World War II era Bereznyak-Isayev BI-1 was introduced as the first rocket-powered fighter aircraft, and Ilyushin Il-2 bomber became the most produced military aircraft in history. Polikarpov Po-2 Kukuruznik is the world's most produced biplane, and Mil Mi-8 is the most produced helicopter.

Famous Russian battle tanks include T-34, the best tank design of World War II,[77] and further tanks of T-series, including T-54/55, the most produced tank in history,[78] first fully gas turbine tank T-80 and the most modern Russian tank T-90. The AK-47 and AK-74 by Mikhail Kalashnikov constitute the most widely used type of assault rifle throughout the world – so much so that more AK-type rifles have been produced than all other assault rifles combined.[79][80] With these and other weapons Russia for a long time has been among the world's top suppliers of arms.

| Lomonosov

(1711–1765) |

Lobachevsky

(1792–1856) |

Mendeleev

(1837–1906) |

Mechnikov

(1845–1916) |

Pavlov

(1849–1936) |

Kovalevskaya

(1850–1891) |

Korolyov

(1907–1966) |

Sakharov

(1921–1989) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

File:Сергей Павлович Королёв (портрет).jpg |

|

Music

Music in 19th-century Russia was defined by the tension between classical composer Mikhail Glinka along with other members of The Mighty Handful, and the Russian Musical Society led by composers Anton and Nikolay Rubinstein. The later tradition of Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, one of the greatest composers of the Romantic era, was continued into the 20th century by Sergei Rachmaninoff, who was one of the last great champions of the Romantic style of European classical music.[81][82] World-renowned composers of the 20th century include Alexander Scriabin, Igor Stravinsky, Sergei Prokofiev, Dmitri Shostakovich and Alfred Schnittke.

Russian conservatories have turned out generations of famous soloists. Among the best known are violinists Jascha Heifetz, David Oistrakh, Leonid Kogan, Gidon Kremer, and Maxim Vengerov; cellists Mstislav Rostropovich, Natalia Gutman; pianists Vladimir Horowitz, Sviatoslav Richter, Emil Gilels, Vladimir Sofronitsky and Evgeny Kissin; and vocalists Fyodor Shalyapin, Mark Reizen, Elena Obraztsova, Tamara Sinyavskaya, Nina Dorliak, Galina Vishnevskaya, Anna Netrebko and Dmitry Hvorostovsky.[83]

| Glinka (1804–1857) |

Mussorgsky (1839–1881) |

Tchaikovsky (1840–1893) |

Rimsky-Korsakov (1844–1908) |

Rachmaninoff (1873–1943) |

Stravinsky (1882–1971) |

Shostakovich (1906–1975) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Since the late Soviet times Russia has experienced another wave of Western cultural influence, which led to the development of many previously unknown phenomena in the Russian culture. The most vivid example, perhaps, is the Russian rock music, which takes its roots both in the Western rock and roll and heavy metal, and in traditions of the Russian bards of Soviet era, like Vladimir Vysotsky and Bulat Okudzhava. At the same time Russian pop music developed from what was known in the Soviet times as estrada into full-fledged industry.

Cinema

Russian and later Soviet cinema was a hotbed of invention, resulting in world-renowned films such as The Battleship Potemkin. Soviet-era filmmakers, most notably Sergei Eisenstein and Andrei Tarkovsky, would become some of the world's most innovative and influential directors. Lev Kuleshov developed the Soviet montage theory; and Dziga Vertov's "film-eye" theory had a huge impact on the development of documentary film making and cinema realism. Many Soviet socialist realism films were artistically successful, including Chapaev, The Cranes Are Flying, and Ballad of a Soldier.

The 1960s and 1970s saw a greater variety of artistic styles in Soviet cinema. Eldar Ryazanov's and Leonid Gaidai's comedies of that time were immensely popular, with many of the catch phrases still in use today. In 1961–68 Sergey Bondarchuk directed an Oscar-winning film adaptation of Leo Tolstoy's epic War and Peace, which was the most expensive film made in the Soviet Union.[84] In 1969, Vladimir Motyl's White Sun of the Desert was released, a very popular film in a genre of ostern; the film is traditionally watched by cosmonauts before any trip into space.[85] In 2002, Russian Ark was the first feature film ever to be shot in a single take. Today, Russian cinema industry continues to expand and receive international recognition.

Architecture

Russian architecture began with the woodcraft buildings of ancient Slavs. Some characteristics taken from the Slavic pagan temples are the exterior galleries and the plurality of towers. Since the Christianization of Kievan Rus', for several centuries Russian architecture was influenced predominantly by the Byzantine architecture, until the Fall of Constantinople. Apart from fortifications (kremlins), the main stone buildings of ancient Rus' were Orthodox churches, with their many domes, often gilded or brightly painted.

Aristotle Fioravanti and other Italian architects brought Renaissance trends into Russia. The 16th century saw the development of unique tent-like churches culminating in Saint Basil's Cathedral. By that time the onion dome design was also fully developed. In the 17th century, the "fiery style" of ornamentation flourished in Moscow and Yaroslavl, gradually paving the way for the Naryshkin baroque of the 1690s. After the reforms of Peter the Great led to Russia absorbing Western culture; the change of the architectural styles in the country generally followed that of Western Europe.

The 18th-century taste for Rococo architecture led to the splendid works of Bartolomeo Rastrelli and his followers. During the reign of Catherine the Great and her grandson Alexander I, the city of Saint Petersburg was transformed into an outdoor museum of Neoclassical architecture. The second half of the 19th century was dominated by the Byzantine and Russian Revival style (this corresponds to Gothic Revival in Western Europe).

Prevalent styles of the 20th century were the Art Nouveau (Fyodor Shekhtel), Constructivism (Moisei Ginzburg and Victor Vesnin), and Socialist Classicism (Boris Iofan). After Stalin's death; a new Soviet leader, Nikita Khrushchev, condemned the "excesses" of the former architectural styles, and in the late Soviet era the architecture of the country was dominated by plain functionalism. After the end of the Soviet Union the situation improved. Many churches demolished in the Soviet times were rebuilt, and this process continues along with the restoration of various historical buildings destroyed in World War II. As for the original architecture, there is no more any common style in modern Russia, though International style has a great influence.

Religion

Russia's largest religion is Christianity—It has the world's largest Orthodox population.[86][87] As of a different sociological surveys on religious adherence; between 41% to over 80% of the total population of Russia adhere to the Russian Orthodox Church.[88][89][90]

Non-religious Russians may associate themselves with the Orthodox faith for cultural reasons. Some Russian people are Old Believers: a relatively small schismatic group of the Russian Orthodoxy that rejected the liturgical reforms introduced in the 17th century. Other schisms from Orthodoxy include Doukhobors which in the 18th century rejected secular government, the Russian Orthodox priests, icons, all church ritual, the Bible as the supreme source of divine revelation and the divinity of Jesus, and later emigrated into Canada. An even earlier sect were Molokans which formed in 1550 and rejected Czar's divine right to rule, icons, the Trinity as outlined by the Nicene Creed, Orthodox fasts, military service, and practices including water baptism.

Other world religions have negligible representation among ethnic Russians. The largest of these groups are Islam with over 100,000 followers from national minorities,[91] and Baptists with over 85,000 Russian adherents.[92] Others are mostly Pentecostals, Evangelicals, Seventh-day Adventists, Lutherans and Jehovah's Witnesses.

Since the fall of the Soviet Union various new religious movements have sprung up and gathered a following among ethnic Russians. The most prominent of these are Rodnovery, the revival of the Slavic native religion also common to other Slavic nations,[93] Another movement, very small in comparison to other new religions, is Vissarionism, a syncretic group with an Orthodox Christian background.

Sports

Football is one of the most popular sports in Russia. The Soviet national team became the first European Champions by winning Euro 1960; and reached the finals of Euro 1988. In 1956 and 1988, the Soviet Union won gold at the Olympic football tournament. Russian clubs CSKA Moscow and Zenit Saint Petersburg won the UEFA Cup in 2005 and 2008. The Russian national football team reached the semi-finals of Euro 2008. Russia was the host nation for the 2018 FIFA World Cup, the first football world cup ever held in Eastern Europe.

Ice hockey is very popular in Russia; and it won the 1993, 2008, 2009, 2012, and the 2014 IIHF World Championships. Bandy is another traditionally popular ice sport in the country. The Soviet Union won all the Bandy World Championships for men between 1957 and 1979,[95] and some thereafter too. The Russian national basketball team won the EuroBasket 2007; and the Russian basketball club PBC CSKA Moscow won the Euroleague in 2006 and 2008. Formula One is also becoming increasingly popular in Russia.

Historically, Russian athletes have been one of the most successful contenders in the Olympic Games;[96] ranking third in an all-time Olympic Games medal count. Larisa Latynina holds the record for the most gold Olympic medals won by a woman. Olympic gold medalist Alexander Popov is widely considered the greatest sprint swimmer in history.[97] Russia is the leading nation in rhythmic gymnastics; and Russian synchronized swimming is the best in the world.[98] Figure skating is another popular sport in Russia, especially pair skating and ice dancing. Russia has produced a number of famous tennis players. Chess is also a widely popular pastime. The 1980 Summer Olympic Games were held in Moscow, and the 2014 Winter Olympics and the 2014 Winter Paralympics were hosted in Sochi.

See also

Notelist

References

- ^ "Russian". Joshua Project. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- ^ "Russian in Russia". Joshua Project. Retrieved 11 August 2020.

- ^ http://www.ukrstat.gov.ua/

- ^ "Численность населения Республики Казахстан по отдельным этносам на начало 2016 года". stat.gov.kz.

- ^ https://www.destatis.de/DE/Publikationen/Thematisch/Bevoelkerung/MigrationIntegration/AuslaendBevoelkerung2010200177004.pdf

- ^ "Regarding Upcoming Conference on Status of Russian Language Abroad". Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Archived from the original on 23 December 2015. Retrieved 24 June 2014.

- ^ "American FactFinder – Results". Data Access and Dissemination Systems (DADS). Archived from the original on 12 February 2020. Retrieved 19 September 2016.

- ^ http://jppi.org.il/uploads/Jewish_Demographic_Policies.pdf

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 14 November 2018. Retrieved 18 January 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ http://www.belstat.gov.by/upload-belstat/upload-belstat-pdf/perepis_2009/5.8-0.pdf

- ^ "Census Profile, 2016 Census". statcan.gc.ca.

- ^ http://data1.csb.gov.lv/pxweb/en/iedz/iedz__iedzrakst/IRG070.px/table/tableViewLayout1/?rxid=d8284c56-0641-451c-8b70-b6297b58f464

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 27 December 2018. Retrieved 18 January 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Maria Stella Ferreira Levy. O papel da migração internacional na evolução da população brasileira (1872 to 1972). inRevista de Saúde Pública, volume supl, June 1974.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 11 June 2019. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ https://www.ellitoral.com/index.php/diarios/2018/02/25/informaciongeneral/INFO-02.html

- ^ "Moldovan Population Census from 2014". Moldovan National Bureau of Statistics.

- ^ a b "La communauté russe en France est "éclectique"".

- ^ "communauté russe en France" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 April 2019. Retrieved 19 January 2019.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 19 January 2019. Retrieved 19 January 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Gyventojų pagal tautybę dalis, palyginti su bendru nuolatinių gyventojų skaičiumi". osp.stat.gov.lt. Retrieved 13 August 2017.

- ^ "2006 census".

- ^ "The State Statistical Committee of the Republic of Azerbaijan". azstat.org. Archived from the original on 7 January 2012.

- ^ http://pxnet2.stat.fi/PXWeb/pxweb/fi/StatFin/StatFin__vrm__vaerak/statfin_vaerak_pxt_11rv.px/table/tableViewLayout1/?rxid=726cd24d-d0f1-416a-8eec-7ce9b82fd5a4

- ^ "Australian Bureau of Statistics". Abs.gov.au. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- ^ "МИД России | 12/02/2009 | Интервью Посла России в Турции В.Е.Ивановского, опубликованное в журнале "Консул" № 4 /19/, декабрь 2009 года". Mid.ru. Archived from the original on 2 January 2016. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- ^ "Immigrant and Emigrant Populations by Country of Origin and Destination". Migration Policy Institute. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

- ^ Informatii utile | Agentia Nationala pentru Intreprinderi Mici si Mijlocii (2002 census) (in Romanian)

- ^ "(number of foreigners in the Czech Republic)" (PDF) (in Czech). 31 December 2016. Retrieved 6 October 2017.

- ^ http://www.demoscope.ru/weekly/2013/0559/barom02.php

- ^ "출입국·외국인정책 통계월보". 출입국·외국인정책 본부 이민정보과.

- ^ The source is not Russian but Russian Koreans.

- ^ http://census.ge/files/results/english/17_Total%20population%20by%20regions%20and%20ethnicity.xls

- ^ Vukovich, Gabriella (2018). Mikrocenzus 2016 – 12. Nemzetiségi adatok [2016 microcensus – 12. Ethnic data] (PDF) (in Hungarian). Budapest. ISBN 978-963-235-542-9. Retrieved 9 January 2019.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Utrikes födda efter födelseland, kön och år". www.scb.se. Statistiska Centralbyrån. Retrieved 25 May 2017.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "(2000 census)". Stats.gov.cn. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- ^ "(2002 census)". Nsi.bg. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- ^ "(2002 census)" (PDF). Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- ^ "rcnk.gr". April 2020.[dead link]

- ^ "Statistics Denmark 2019 K4: Russian". Statistics Denmark.

- ^ "Census ethnic group profiles: Russian". Stats NZ. 2013.

- ^ "POPULATION CENSUS 2001 VOL4". 2004.

- ^ a b c Balanovsky, Oleg; Rootsi, Siiri; Pshenichnov, Andrey; Kivisild, Toomas; Churnosov, Michail; Evseeva, Irina; Pocheshkhova, Elvira; Boldyreva, Margarita; Yankovsky, Nikolay; Balanovska, Elena; Villems, Richard (January 2008). "Two sources of the Russian patrilineal heritage in their Eurasian context". American Journal of Human Genetics. 82 (1): 236–50. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.09.019. PMC 2253976. PMID 18179905.

- ^ "Russian". Ethnologue. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- ^ "Russian". Joshua Project. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- ^ "Definition of Russian". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 21 September 2016.

- ^ "РУССКИЕ И РОССИЯНЕ". pravoslavie.ru. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- ^ Quiles, Carlos (17 April 2019). "The cradle of Russians, an obvious Finno-Volgaic genetic hotspot". Indo-European.eu. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- ^ Blöndal, Sigfús (16 April 2007). The Varangians of Byzantium. Cambridge University Press. p. 1. ISBN 9780521035521. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- ^ The Ru|||ssian Primary Chronicle: Laurentian Text, Translated by O. P. Sherbowitz-Wetzor ISBN 0-910956-34-0

- ^ "Online Etymology Dictionary". etymonline.com.

- ^ "Топонимические следы руссов-славян в Рослагене : Доисторическая история славян : Александр Козинский". kozinsky.ru. Archived from the original on 14 August 2019. Retrieved 14 August 2019.

- ^ "Руслаген". поисковая система. Archived from the original on 14 August 2019. Retrieved 14 August 2019.

- ^ Максимович К.А. (2006). "Происхождение этнонима Русь в свете исторической лингвистики и древнейших письменных источников". КАNIEKION. Юбилейный сборник в честь 60-летия профессора Игоря Сергеевича Чичурова. М.: ПЕТГУ: сс.14–56.

- ^ Седов В.В. Древнерусская народность. Русы

- ^ Streitberg, Bopp, Wilhelm, Franz (1917). Slavisch-Litauisch, Albanisch. Brückner, A., Streitberg, Wilhelm. Strassburg: Karl J. Trübner. p. 42. ISBN 978-3-11-144680-6. OCLC 811390127.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Новости NEWSru.com :: Ученые завершили масштабное исследование генофонда русского народа (Фотороботы)". Newsru.com. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- ^ "Russia – History". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 28 August 2018.

- ^ Kunstmann, Heinrich. (1996). Die Slaven : ihr Name, ihre Wanderung nach Europa und die Anfänge der russischen Geschichte in historisch-onomastischer Sicht. Steiner. p. 214. ISBN 3515068163. OCLC 231684405.

- ^ The Primary Chronicle is a history of the Ancient Rus' from around 850 to 1110, originally compiled in Kiev about 1113.

- ^ Pivtorak. Formation and dialectal differenciaton of the Old Rus language. 1988

- ^ "Повесть временных лет".

- ^ Russians left behind in Central Asia. BBC News. 23 November 2005.

- ^ "Saving the souls of Russia's exiled Lipovans". The Daily Telegraph. 9 April 2013.

- ^ "The Ghosts of Russia That Haunt Shanghai". The New York Times. 21 September 1999.

- ^ "Russian language". University of Toronto. Archived from the original on 6 January 2007. Retrieved 27 December 2007.

- ^ Matthias Gelbmann (19 March 2013). "Russian is now the second most used language on the web". W3Techs. Q-Success. Retrieved 17 June 2013.

- ^ "JAXA | My Long Mission in Space". global.jaxa.jp.

- ^ Poser, Bill (5 May 2004). "The languages of the UN". Itre.cis.upenn.edu. Retrieved 29 October 2010.

- ^ Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia 2007. Russian Literature. Archived from the original on 20 August 2009. Retrieved 7 January 2008.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Kelly, C (2001). Russian Literature: A Very Short Introduction (Very Short Introductions) (Paperback). Oxford Paperbacks. ISBN 0-19-280144-9.

- ^ "Russian literature; Leo Tolstoy". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 11 April 2008.

- ^ Otto Friedrich (6 September 1971). "Freaking-Out with Fyodor". Time Magazine. Retrieved 10 April 2008.

- ^ "American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics – Home Page". Aiaa.org. Archived from the original on 4 January 2012. Retrieved 2 January 2010.

- ^ Russian space program in 2009: plans and reality

- ^ "Premium content". The Economist. 19 August 2009. Retrieved 2 January 2010.

- ^ George Parada (n.d.), "Panzerkampfwagen T-34(r)" at Achtung Panzer! website, retrieved on 17 November 2008.

- ^ Halberstadt, Hans Inside the Great Tanks The Crowood Press Ltd. Wiltshire, England 1997 94–96 ISBN 1-86126-270-1

"The T-54/T-55 series is the hands down, all-time most popular tank in history." - ^ Poyer, Joe. The AK-47 and AK-74 Kalashnikov Rifles and Their Variations. North Cape Publications. 2004.

- ^ "Weaponomics: The Economics of Small Arms" (PDF).

- ^ Norris, Gregory; ed. Stanley, Sadie (1980). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, 2nd edition. London: Macmillan. p. 707. ISBN 0-333-23111-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Norris, Gregory; ed. Stanley, Sadie (1980). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, 2nd edition. London: Macmillan. p. 707. ISBN 978-0-333-23111-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Russia::Music". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 5 October 2009.

- ^ Birgit Beumers. A History of Russian Cinema. Berg Publishers (2009). ISBN 978-1-84520-215-6. p. 143.

- ^ "White Sun of the Desert". Film Society of Lincoln Center. Archived from the original on 5 September 2008. Retrieved 18 January 2008.

- ^ "Religious Belief and National Belonging in Central and Eastern Europe". Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project. 10 May 2017.

- ^ "Orthodox Christianity in the 21st Century". Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project. 10 November 2017.

- ^ There is no official census of religion in Russia, and estimates are based on surveys only. In August 2012, ARENA determined that about 46.8% of Russians are Christians (including Orthodox, Catholic, Protestant, and non-denominational), which is slightly less than an absolute 50%+ majority. However, later that year the Levada Center Archived 31 December 2012 at the Wayback Machine determined that 76% of Russians are Christians, and in June 2013 the Public Opinion Foundation determined that 65% of Russians are Christians. These findings are in line with Pew's 2010 survey, which determined that 73.3% of Russians are Christians, with VTSIOM Archived 29 September 2020 at the Wayback Machine's 2010 survey (~77% Christian), and with Ipsos MORI Archived 17 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine's 2011 survey (69%).

- ^ Верю — не верю. "Ogonek", № 34 (5243), 27 August 2012. Retrieved 24 September 2012.

- ^ "Archived copy" Опубликована подробная сравнительная статистика религиозности в России и Польше (in Russian). Archived from the original on 2 December 2015. Retrieved 6 January 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Арена". Archived from the original on 2 December 2013. Retrieved 21 July 2013.

- ^ "statistics". Adherents.com. Archived from the original on 10 August 2018. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- ^ Victor Shnirelman. "Christians! Go home": A Revival of Neo-Paganism between the Baltic Sea and Transcaucasia Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Journal of Contemporary Religion, Vol. 17, No. 2, 2002.

- ^ Kurt Badenhausen (8 March 2016). "How Maria Sharapova Earned $285 Million During Her Tennis Career". Forbes. Retrieved 15 February 2020.

- ^ Ralph Hickok (18 February 2013). "Bandy". Hickoksports.com. Archived from the original on 23 February 2002. Retrieved 4 May 2013.

- ^ Jenifer Parks (2016). The Olympic Games, the Soviet Sports Bureaucracy, and the Cold War: Red Sport, Red Tape. Lexington Books. pp. 178–179. ISBN 978-1-4985-4119-0.

- ^ John Grasso; Bill Mallon; Jeroen Heijmans (2015). Historical Dictionary of the Olympic Movement. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 36. ISBN 978-1-4422-4860-1.

- ^ "Russian mastery in synchronized swimming yields double gold". USA TODAY.

External links

Media related to Russians at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Russians at Wikimedia Commons- (in Russian) 4.1. Population by nationality

- (in Russian) "People and Cultures: Russians" book published by Russian Academy of Sciences

- Pre-Revolutionary photos of women in Russian folk dress