Contemporary architecture

Top: Resorts World Sentosa by Michael Graves; Center left: One World Trade Center by David Childs; Center right: Makkah Royal Clock Tower by Mahmoud Bodo Rasch; Bottom: Beijing National Stadium by Herzog & de Meuron | |

| Years active | 2000–present |

|---|---|

| Location | International |

Contemporary architecture is the architecture of the 21st century. No single style is dominant.[1] Contemporary architects work in several different styles, from postmodernism, high-tech architecture and new references and interpretations of traditional architecture[2][3] to highly conceptual forms and designs, resembling sculpture on an enormous scale. Some of these styles and approaches make use of very advanced technology and modern building materials, such as tube structures which allow construction of buildings that are taller, lighter and stronger than those in the 20th century, while others prioritize the use of natural and ecological materials like stone, wood and lime.[4] One technology that is common to all forms of contemporary architecture is the use of new techniques of computer-aided design, which allow buildings to be designed and modeled on computers in three dimensions, and constructed with more precision and speed.

Contemporary buildings and styles vary greatly. Some feature concrete structures wrapped in glass or aluminium screens, very asymmetric facades, and cantilevered sections which hang over the street. Skyscrapers twist, or break into crystal-like facets. Facades are designed to shimmer or change color at different times of day.

Whereas the major monuments of modern architecture in the 20th century were mostly concentrated in the United States and western Europe, contemporary architecture is global; important new buildings have been built in China, Russia, Latin America, and particularly in Arab states of the Persian Gulf; the Burj Khalifa in Dubai was the tallest building in the world in 2019, and the Shanghai Tower in China was the second-tallest.

Additionally, in the late 20th century, New Classical Architecture, a traditionalist response to modernist architecture, emerged, continuing into the 21st century.[5] The 21st century saw the emergence of multiple organizations dedicated to the promotion of local and/or traditional architecture. Examples include the International Network for Traditional Building, Architecture & Urbanism (INTBAU),[6] the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art (ICAA),[7] the Driehaus Architecture Prize,[8] and the Complementary architecture movement. New traditional architects include Michael Graves, Léon Krier, Yasmeen Lari, Robert Stern and Abdel-Wahed El-Wakil.

Most of the landmarks of contemporary architecture are the works of a small group of architects who work on an international scale. Many were designed by architects already famous in the late 20th century, including Mario Botta, Frank Gehry, Jean Nouvel, Norman Foster, Ieoh Ming Pei and Renzo Piano, while others are the work of a new generation born during or after World War II, including Zaha Hadid, Santiago Calatrava, Daniel Libeskind, Jacques Herzog, Pierre de Meuron, Rem Koolhaas, and Shigeru Ban. Other projects are the work of collectives of several architects, such as UNStudio and SANAA, or large multinational agencies such as Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, with thirty associate architects and large teams of engineers and designers, and Gensler, with 5,000 employees in 16 countries.

Museums

[edit]-

The Quadracci Pavilion of the Milwaukee Art Museum in Milwaukee, Wisconsin by Santiago Calatrava (2001)

-

De Young Museum in San Francisco by Herzog & de Meuron (2005)

-

The Denver Art Museum in Denver Colorado, by Daniel Libeskind (2006)

-

New Museum of Contemporary Art in New York City, by SANAA (2007)

-

The Titanic Museum in Belfast, Northern Ireland, United Kingdom, by Eric Kuhne and Associates (2012)

-

Whitney Museum of Art in New York City by Renzo Piano (2015)

-

Ceiling of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art by Snøhetta (2016), covered with fiber-reinforced plastic

Some of the most striking and innovative works of contemporary architecture are art museums, which are often examples of sculptural architecture, and are the signature works of major architects. The Quadracci Pavilion of the Milwaukee Art Museum in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, was designed by Spanish architect Santiago Calatrava. Its structure includes a movable, wing-like brise soleil that opens up for a wingspan of 217 feet (66 m) during the day, folding over the tall, arched structure at night or during bad weather.[9]

The Walker Art Center in Minneapolis (2005), was designed by the Swiss architects Herzog and de Meuron, who designed the Tate Modern museum in London, and who won the Pritzker Architecture Prize, the most prestigious award in architecture, in 2001. It updates and provides a contrast to the austere earlier Modernist structure designed by Edward Larrabee Barnes by adding a five-story tower clad in panels of delicately sculpted gray aluminum, which change color with the changing light, connecting by a wide glass gallery leading to the older building. It also harmonizes with two stone churches opposite.[10]

The Polish-born American architect Daniel Libeskind (born 1946) is one of the most prolific of contemporary museum architects; He was an academic before he began designing buildings and was one of the early proponents of the architectural theory of Deconstructivism. The exterior of his Imperial War Museum North in Manchester, England (2002), has an exterior which resembles, depending upon the light and time of day, huge and broken pieces of earth or armor plates, and is said to symbolize the destruction of war. In 2006 Libeskind finished the Hamilton Building of the Denver Art Museum in Denver Colorado, composed of twenty sloping planes, none of them parallel or perpendicular, covered with 230,000 square feet of titanium panels. Inside, the walls of the galleries are all different, sloping and asymmetric.[11] Libeskind completed another striking museum, the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, Ontario, Canada (2007), also known as "The Crystal," a building whose form, resembles a shattered crystal.[12] Libeskind's museums have been both admired and attacked by critics. While admiring many features of the Denver Art Museum, The New York Times' architecture critic Nicolai Ouroussoff wrote that "In a building of canted walls and asymmetrical rooms—tortured geometries generated purely by formal considerations — it is virtually impossible to enjoy the art."[13]

The De Young Museum in San Francisco was designed by the Swiss architects Herzog & de Meuron. It opened in 2005, replacing an older structure that was badly damaged in an earthquake in 1989. The new museum was designed to blend with the park's natural landscape and resist strong earthquakes. The building can move up to three feet (91 centimeters) on ball-bearing sliding plates and viscous fluid dampers that absorb kinetic energy.

The Zentrum Paul Klee by Renzo Piano is an art museum near Bern, Switzerland, located next to an autoroute in the Swiss countryside. The museum blends into the landscape by taking three rolling hills made of steel and glass. One building houses the gallery (which is almost entirely underground to preserve the fragile drawings of Klee from the effects of sunlight). At the same time, the other two "hills" contain an education center and administrative offices.[14]

The Centre Pompidou-Metz, in Metz, France, (2010), a branch of the Centre Pompidou museum of modern art in Paris, was designed by Shigeru Ban, a Japanese architect who won the Pritzker Prize for Architecture in 2014. The roof is the most dramatic feature of the building; it is a 90 m (300 ft) wide hexagon with a surface area of 8,000 m2 (86,000 sq ft), composed of sixteen kilometers of glued laminated timber, that intersect to form hexagonal wooden units resembling the cane-work pattern of a Chinese hat. The roof's geometry is irregular, featuring curves and counter-curves over the entire building, particularly the three exhibition galleries. The entire wooden structure is covered with a white fiberglass membrane, and a coating of teflon protects from direct sunlight and allows light to pass through.

The Louis Vuitton Foundation by Frank Gehry (2014) is the gallery of contemporary art located adjacent to the Bois de Boulogne in Paris was opened in October 2014. Gehry described his architecture as inspired by the glass Grand Palais of the 1900 Paris Exposition and by the enormous glass greenhouses of the Jardin des Serres d'Auteuil near the park, built by Jean-Camille Formigé in 1894–95.[15] Gehry had to work within strict height and volume restrictions, which required any part of the building over two stories to be made of glass. The building is low because of the height limits, sited in an artificial lake with water cascading beneath the building. The interior gallery structures are covered in a white fiber-reinforced concrete called Ductal.[16] Similar in concept to Gehry's Walt Disney Concert Hall, the building is wrapped in curving glass panels resembling sails inflated by the wind. The glass "Sails" are made of 3,584 laminated glass panels, each one a different shape, specially curved for its place in the design.[17] Inside the sails is a cluster of two-story towers containing 11 galleries of different sizes, with flower garden terraces, and rooftop spaces for displays.[18]

The new Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City by Renzo Piano (2015) took a very different approach from the sculptural museums of Frank Gehry. The Whitney has an industrial-looking facade and blends into the neighborhood. Michael Kimmelman, the architecture critic of The New York Times called the building a "mishmash of styles" but noted its similarity to Piano's Centre Pompidou in Paris, in the way that it mixed with the public spaces around it. "Unlike so much big-name architecture," Kimmelman wrote, "it's not some weirdly shaped trophy building into which all the practical stuff of a working museum must be fitted."[19]

The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art is actually two buildings by different architects fit together; an earlier (1995) five-story postmodernist structure by the Swiss architect Mario Botta, to which has been joined a much larger ten-story white gallery by the Norwegian-based firm of Snøhetta (2016). The expanded building includes a green living wall of native plants in San Francisco; a free ground-floor gallery with 25-foot (7.6 m) tall glass walls that will place art on view to passersby and glass skylights that flood the upper floors of offices (though not the galleries) with light. The facades clad are with lightweight panels made of Fibre-Reinforced Plastic. The critical reaction to the building was mixed. Roberta Smith of The New York Times said the building set a new standard for museums and wrote: "The new building's rippling, sloping facade, rife with subtle curves and bulges, establishes a brilliant alternative to the straight-edged boxes of traditional modernism and the rebellion against them initiated by Frank Gehry, with his computer-inspired acrobatics."[20] On the other hand, the critic of The Guardian of London compared the facade of the building to "a gigantic meringue with a hint of Ikea."[21]

Concert halls

[edit]-

Auditorio de Tenerife, Canary Islands, Spain by Santiago Calatrava (2003)

-

Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles by Frank Gehry (2003)

-

Interior of the Walt Disney Concert Hall with organ facade designed by Frank Gehry (2003)

-

Interior of the Casa da Musica by Rem Koolhaas (2005)

-

Oslo Opera House by Snøhetta (2008)

-

Szczecin Philharmonic by Barozzi Veiga (2014)

-

Interior of the Philharmonie de Paris by Jean Nouvel (2015)

Santiago Calatrava designed the Auditorio de Tenerife he concert hall of Tenerife, the major city of the Canary Islands. with a shell-like wing of reinforced concrete. The shell touches the ground at only two points.[9]

The Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles (2003) is one of the major works by California architect Frank Gehry The exterior is stainless steel, formed like the sails of sailboats. The interior is in the Vineyard style, with the audience surrounding the stage. Gehry designed the dramatic array of pipes of the organ to complement the exterior style of the building.

The Casa da Musica in Porto, Portugal, by the Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas (2005) is unique among concert halls in having two walls made entirely of glass. Nicolai Ouroussoff, architecture critic from The New York Times, wrote "The building's chiseled concrete form, resting on a carpet of polished stone, suggests a bomb about to explode. He declared that in its originality it was one of the most important concert halls built in the last 100 years". ranking with the Walt Disney Concert Hall, in Los Angeles, and the Berliner Philharmonie.[22]

The interior of the Copenhagen Opera House by Henning Larsen (2005) has an oak floor and maple walls to enhance hat acoustics. The royal box of the Queen, usually placed in the back, is next to stage.

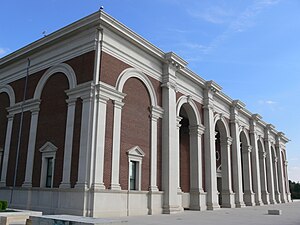

The Schermerhorn Symphony Center in Nashville, Tennessee, by David M. Schwarz & Earl Swensson (2006), is an example of Neo-Classical architecture, borrowed literally from Roman and Greek models. It complements another Nashville landmark, a full-scale replica of the Parthenon.

Three concert halls were awarded with the European Union Prize for Contemporary Architecture: the Oslo Opera House by Snøhetta (2008), the Harpa concert hall in Reykjavík by Henning Larsen Architects and Olafur Eliasson (2011) as well as the Szczecin Philharmonic by Barozzi Veiga (2014).

The Philharmonie de Paris by French architect Jean Nouvel opened in 2015. The concert hall is at La Villette, in a park at the edge of Paris devoted to museums, a music school and other cultural institutions, where its unusual shape blends with the late 20th-century modern architecture. The exterior of the building takes the form of glittering irregular cliff cut by horizontal fins which reveal a ramp leading upwards The exterior is clad in thousands of small pieces of aluminum in three different colors, from white to gray to black. A path leads up the ramp to the top of building to a terrace with a dramatic view of the peripheric highway around the city. view of the neighborhood. The hall, like the Disney Hall in Los Angeles, has Vineyard style seating, with the audience surrounding the main stage. The seating can be re-arranged in different styles depending upon the type of music performed.[23] When it opened, the architectural critic of the London Guardian compared it to a space ship that had crash-landed on the outskirts of the city.[24]

The Elbphilharmonie concert hall in Hamburg, Germany, by Herzog & de Meuron, which was inaugurated in January 2017, is the tallest inhabited building in the city, with a height of 110 meters (360 feet). The glass concert hall, which has 2100 seats in Vineyard style, is perched atop a former warehouse. One side of the concert hall building contains a hotel, while the structure on the other side above the concert hall contains forty five apartments. The concert hall in the middle is isolated from the sound of the other parts of the building by an "eggshell" of plaster and paper panels and insulation resembling feather pillows.[25]

Skyscrapers

[edit]-

30 St Mary Axe (or "The Gherkin") in London, by Norman Foster (2004)

-

The Abraj Al Bait a complex of seven skyscraper hotels in Mecca, Saudi Arabia (2011)

-

De Rotterdam in Rotterdam, Netherlands by Office for Metropolitan Architecture (2013)

-

Lakhta Center, in Saint Petersburg (2019)

The skyscraper (usually defined as a building over 40 stories high)[26] first appeared in Chicago in the 1890s, and was largely an American style in the mid 20th century, but in the 21st century skyscrapers were found in almost every large city on every continent. A new construction technology, the framed tube structure, was first developed in the United States in 1963 by structural engineer Fazlur Rahman Khan of Skimore, Owings and Merrill, which permitted the construction of super-tall buildings, which needed fewer interior walls, had more window space, and could better resist lateral forces, such as strong winds.[27]

The Burj Khalifa in Dubai, United Arab Emirates is the tallest structure in the world, standing at 829.8 m (2,722 ft).[28] Construction of the Burj Khalifa began in 2004, with the exterior completed 5 years later in 2009. The primary structure is reinforced concrete. Burj Khalifa was designed by Adrian Smith, then of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM). He also was lead architect on the Jin Mao Tower, Pearl River Tower, and Trump International Hotel & Tower.

Adrian Smith and his own firm are the architects for the building which, in 2020, meant to replace the Burj-Khalifa as the tallest building in the world. The Jeddah Tower in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, is planned to be 1,008 meters, or (3,307 ft) tall, which will make it the tallest building in the world, and the first building to be more than one kilometer in height. Construction began in 2013, and the project is scheduled to be completed in 2020.[29][needs update]

After the destruction of the twin towers of the World Trade Center in the September 11 terrorist attacks, a new trade center was designed, with the main tower designed by David Childs of SOM. One World Trade Center, opened in 2015, is 1,776 feet (541 m) tall, making it the tallest building in the western hemisphere.

In London, one of the most notable contemporary landmarks is 30 St Mary Axe, popularly known as "The Gherkin", designed by Norman Foster (2004). It replaced the London Millennium Tower – a much taller project that Foster earlier had proposed for the same site, which would have been the tallest building in Europe, but was so tall that it interfered with the flight pattern for Heathrow Airport. The steel framework of the Gherkin is integrated into the glass facade.[30]

The tallest building in Poland and in the European Union (as of 2023) is Varso in Warsaw, designed by Norman Foster. Completed in 2022, it is 310-meter (1,020-foot) tall.

The tallest building in Moscow is the Federation Tower, designed by the Russian architect Sergei Tchoban with Peter Schweger. Completed in 2017, with a height 373 meters, it surpassed Mercury City Tower, another skyscraper in Moscow, when it was built as the tallest building in Europe.

The tallest building in China as of 2015 is the Shanghai Tower by the U.S. architectural and design firm of Gensler. It is 632-meter (2,073-foot) tall, with 127 floors, making it in 2016 the second-tallest building in the world. It also features the fastest elevators, which reach a speed of 20.5 meters per second (67 feet per second; 74 kilometers per hour) .[31][32]

Most skyscrapers are designed to express modernity; the most notable exception is the Abraj Al Bait, a complex of seven skyscraper hotels build by the government of Saudi Arabia to house pilgrims coming the holy shrine of Mecca. The centerpiece of the group is the Makkah Palace Clock Tower Hotel, with a gothic revival tower; it was the fourth-tallest building in the world in 2016, 581.1 meters (1,906 feet) high.

Residential buildings

[edit]-

The Organic Försters Weinterrassen by Udo Heimermann (2000)

-

Celebration, Florida, USA, by Cooper Robertson (2000)

-

Gasometer, Vienna, by Coop Himmelb(l)au (2001)

-

Accordia, Cambridge, England - Alison Brooks (2003 - 2011)

-

Blue Condominium tower in New York City by Bernard Tschumi (2007)

A tendency in contemporary residential architecture, particularly in the rebuilding of older neighborhoods in large cities, is the luxury condominium tower, with very expensive apartments for sale designed by "starchitects", that is, internationally famous architects. These buildings frequently have little relationship with the architecture of their neighborhood, but stand like signature works of their architects.

Daniel Libeskind (born 1946), was born in Poland and studied, taught and practiced architecture in the United States. In 2016 he was professor of architecture at UCLA in Los Angeles, He is known as much for his writings as his architecture; he was a founder of the movement called Deconstructivism. Best known for his museums, he also constructed a notable complex of residential apartment buildings in Singapore (2011) and The Ascent at Roebling's Bridge a 22-story apartment building in Covington, Kentucky (2008). The name of the latter is taken from the Roebling Suspension Bridge nearby on the Ohio River, but the structure of the building of luxury condominiums is extremely contemporary, sloping upward like the bridge cables to a peak, with a sharp edge and leaning slightly outward as the building rises.

One cheerful feature of contemporary residential architecture is color; Bernard Tschumi uses colored ceramic tiles on facades as well as unusual forms to make his buildings stand out. One example is the Blue Condominium in New York City (2007).[33]

Another contemporary tendency is the conversion of industrial buildings into mixed residential communities. An example is the Gasometer in Vienna, a group of four massive brick gas production towers constructed at the end of the 19th century. They have been transformed into a mixed residential, office and commercial complex, completed between 1999 and 2001. Some residences are located inside the towers, and others are in new buildings attached to them. The upper floors are devoted to housing units the middle floors to offices, and the ground floors to entertainment and shopping malls. with sky bridges connecting the shopping mall levels. Each tower was built by a prominent architect the participants were Jean Nouvel, Coop Himmelblau, Manfred Wehldorn and Wilhelm Holzbauer. The historic exterior walls of the towers were preserved.[34]

The Isbjerget, Danish for "iceberg", in Aarhus, Denmark (2013), is a group of four buildings with 210 apartments, both rented and owned, for residents with a range of incomes, located on the waterfront of a former industrial port in Denmark. The complex was designed by the Danish firms CEBRA and JDS Architects, French architect Louis Paillard and the Dutch firm SeARCH, and was financed by the Danish pension fund. The buildings are designed so that all the units, even those in the back, have a view of sea. The design and color of the buildings is inspired by icebergs. The buildings are clad in white terrazzo and have balconies made of blue glass.

Religious architecture

[edit]-

Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels in Los Angeles, California, by Rafael Moneo (2002)

-

Chapel at Thomas Aquinas College by Duncan Stroik (2009)

-

St. Jude's Anglican Cathedral in Iqaluit, Canada (2012)

-

The Northern Lights Cathedral in Alta, Norway, by the Danish architects Schmidt, Hammer and Lassen (2013)

-

The central mosque of Cambridge, England, dubbed as Europe's first 'eco-mosque', by Marks Barfield Architects (2019)

Surprisingly few contemporary churches were built between 2000 and 2017. Church architects, with a few exceptions, rarely showed the same freedom of expression as architects of museums, concert halls and other large buildings.[35] The new cathedral for the City of Los Angeles California, was designed in a postmodern style by the Spanish architect Rafael Moneo.[36] The previous cathedral had been serious damaged by an earthquake in 1995; the new building was specially designed to resist similar shocks.

The Northern Lights Cathedral, by the Denmark-based international firm of Schmidt, Hammer and Lassen, is located in Alta, Norway, one of northernmost cities in the world.[37] Their other important works include the National Library of Denmark in Copenhagen.[38]

The Vrindavan Chandrodaya Mandir is a Hindu Temple in Vrindivan, in Uttar Pradesh state in India, which was under construction at the end of 2016. The architects are InGenious Studio Pvt. Ltd. of Gurgaon and Quintessence Design Studio of Noida, in India. The entrance is in the traditional Nagara style of Indian architecture, while the tower is contemporary, with a glass facade up to the 70th floor.[39] It is scheduled for completion in 2019. When completed, at 700 feet (210 meters) or 70 floors) it will be the tallest religious structure in the world.[40]

One of the most unusual contemporary churches is St. Jude's Anglican Cathedral in Iqaluit, the capital of Nunavut, the northernmost and least populous region of Canada. The church is built in the shape of an igloo, and serves the Inuktitut-speaking population of the region.

Another unusual contemporary church is the Cardboard Cathedral in Christchurch, New Zealand designed by Japanese architect Shigeru Ban. It replaced the city's main cathedral, damaged by the 2011 Christchurch earthquake. The cathedral, which seats seven hundred persons, rises 21 metres (69 ft) above the altar. Materials used include 60-centimetre (24 in)-diameter cardboard tubes, timber and steel.[41] The roof is of polycarbon,[42] with eight shipping containers forming the walls. "coated with waterproof polyurethane and flame retardants" with two-inch gaps between them so that light can filter inside.[43]

Stadiums

[edit]-

The Allianz Arena in Munich, Germany, by Herzog & de Meuron (2005)

-

Beijing National Stadium by Herzog & de Meuron (2008)

The Swiss architects Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron designed the Allianz Arena in Munich, Germany, completed in 2005. It seats 75,000 spectators. The structure is wrapped in 2,874 ETFE-foil air panels that are kept inflated with dry air; each panel can be independently illuminated red, white, or blue. When illuminated, the stadium is visible from the Austrian Alps, fifty miles (80 kilometers) away.[44]

Among the most prestigious projects and best-known projects in contemporary architecture are the stadiums for the Olympic Games, whose architects are chosen by highly publicized international competitions. The Beijing National Stadium, built for the 2008 Games and popularly known as the Bird's Nest because of its intricate exterior framework, was designed by the Swiss firm of Herzog & de Meuron, with Chinese architect Li Xinggang. It was designed to seat 91,000 spectators, and when constructed had a retractable roof, since removed. Like many contemporary buildings, it is actually two structures; a concrete bowl in which the spectators sit, surrounded at distance of fifty feet by a glass and steel framework. The exterior "Bird's nest" design was inspired by the pattern of Chinese ceramics. The stadium when completed was the largest enclosed space in the world, and was also the largest steel structure, with 26 kilometers of unwrapped steel.[45][46]

The National Stadium in Kaohsiung, Taiwan by Japanese architect Toyo Ito (2009), is the form of a dragon. Its other distinctive feature is the array of solar panels that cover almost all of the exterior, providing most of the energy needed by the complex.

Government buildings

[edit]-

London City Hall by Norman Foster (2002)

-

Parliament House, Valletta, Malta by Renzo Piano (2015)

-

The Port Authority Building (Havenhuis) in Antwerp, Belgium by Zaha Hadid (2016)

Government buildings, once almost universally serious and sober looking, usually in variations of the school of neoclassical architecture, began to appear in more sculptural and even whimsical forms. One of the most dramatic examples was the London City Hall by Norman Foster (2002), the headquarters of the Greater London Authority. The unusual egg-like building design was intended to reduce the amount of exposed wall and to save energy, though the results have not entirely met expectations.[47] One unusual feature is a helical stairway that spirals from the lobby up to the top of the building.

Some new government buildings, such as the Parliament House, Valletta, Malta by Renzo Piano (2015) created controversy because of the contrast between their style and the historic architecture around them.[48]

Most new government buildings attempt to express solidity and seriousness; an exception is the Port Authority (Havenhuis) in Antwerp, Belgium by Zaha Hadid (2016), where a ship-like structure of glass and steel on a white concrete perch seems to have landed atop the old port building constructed in 1922. The faceted glass structure also resembles a diamond, a symbol of Antwerp's role as the major market of diamonds in Europe. It was one of the last works of Hadid, who died in 2016.

University buildings

[edit]-

Sharp Centre for Design at Ontario College of Art and Design, by William Alsop (2004)

-

Rolex Learning Center at the École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne in Lausanne, Switzerland by SANAA (2010)

-

The "Siamese Towers" at the Pontifical Catholic University in Santiago, Chile by Alejandro Aravena (2013)

-

Dr Chau Chak Wing Building in Sydney, Australia by Frank Gehry (2014)

-

Blavatnik School of Government, Oxford University, UK, by Herzog & de Meuron (2015)

The Dr Chau Chak Wing Building is a Business School building of the University of Technology Sydney in Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, designed by Frank Gehry and completed in 2015. It is the first building in Australia designed by Gehry. The building's façade, made of 320,000 custom designed bricks, was described by one critic as the "squashed brown paper bag". Frank Gehry responded, "Maybe it's a brown paper bag, but it's flexible on the inside, there's a lot of room for changes or movement."[49]

The Siamese Twins Towers" at the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile in Santiago, Chile are by the Chilean architect Alejandro Aravena (born 1967), completed in 2013. Aravena was the winner of the 2016 Pritzker Architecture Prize.

Libraries

[edit]-

Interior of the Bibliotheca Alexandrina (2002)

-

Seattle Central Library by Rem Koolhaas (2006)

-

Interior of the Seattle Central Library by Rem Koolhaas (2006)

-

Library and Learning Center of the University of Vienna, by Zaha Hadid (2008)

-

Part of the interior of the Library of Birmingham

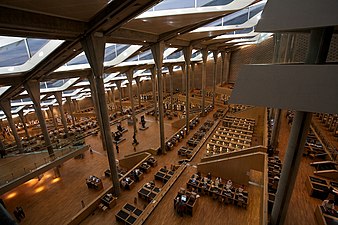

The Bibliotheca Alexandrina in Alexandria, Egypt, by the Norwegian firm of Snøhetta (2002), attempts to recreate, in modern form, the famous Alexandria Library of antiquity. The building, by the edge of the Mediterranean, has shelf space for eight million books,[50] and a main reading room covering 20,000 square metres (220,000 sq ft) on eleven cascading levels. plus galleries for expositions and a planetarium. The main reading room is covered by a 32-meter-high glass-panelled roof, tilted out toward the sea like a sundial, and measuring some 160 m in diameter. The walls are of gray Aswan granite, carved with characters from 120 different human scripts.

The Seattle Central Library by Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas (2006) features a glass and steel wrapping around a stack of platforms. One unusual feature is a ramp with continuous bookshelves spiraling upward four floors.

Malls and retail stores

[edit]-

The Gold Souk of the Dubai Mall (2008)

-

Prada Aoyama store, Tokyo, by Herzog & de Meuron (2003)

-

Louis Vuitton store, Ginza Namiki, Tokyo by Jun Aoki and Associates (2014)

The shopping malls are the elephants of commercial architecture, massive structures which combine retail stores, food outlets, and entertainment under a single roof. The largest in area (though not in retail space, since much of the mall is devoted to entertainment and public space) and perhaps most extravagant is the Dubai Mall in the United Arab Emirates, designed by DP Architects of Singapore and opened in (2008), which features, in addition to shops and restaurants, a gigantic walk-through aquarium and underwater zoo, plus a huge ice skating rink, and, just outside, the highest fountain and tallest building in the world.

In competition with shopping malls are downtown department stores and shops of individual designer brands. These buildings are traditionally designed to attract attention and to express the modernity of the products they sell. A notable example is the Selfridge's Department Store in Birmingham, England, a department store designed by the firm of Future Systems, founded in 1979 by Jan Kaplický (1937–2009). The department store exterior is composed of undulating concrete in convex and concave forms, entirely covered with gleaming blue and white ceramic tiles.[51]

Designer brand shops try make their logo visible and to set themselves apart from department stores. One notable example is the Louis Vuitton store in the Ginza district of Tokyo, with a new facade designed by Japanese studio of Jun Aoki and Associates with a patterned and perforated shell based on the brand's logo.[52]

Airports, railway stations and transport hubs

[edit]-

Interior of Terminal Four of Barajas Airport in Madrid, by Richard Rogers (2007)

-

Aerial view of Terminal Three of Beijing Capital International Airport (orange roof in center) by Norman Foster (2008)

-

Express train in the Transportation Center of Terminal Three of Beijing Capital International Airport (2008)

-

Berlin Hauptbahnhof, Berlin Germany, by Gerkan, Marg and Partners (2006)

-

Shenzhen Bao'an International Airport, China by Massimiliano Fuksas (2014)

-

Central atrium of Birmingham New Street railway station

-

The World Trade Center Transportation Hub in New York City, by Santiago Calatrava (2016)

-

Interior of the Oculus of the World Trade Center Transportation Hub by Santiago Calatrava (2016)

Beijing Capital International Airport has been one of the fast-growing airports in the world. The new Terminal Three was designed by Norman Foster to handle the increased number of passengers coming for the 2008 Beijing Olympics. The terminal is the second largest in the world, after the Dulles Airport terminal near Washington, DC, and in 2008 was the sixth largest building in the world. The flat-roofed building looks like part of the runway from above.

The World Trade Center Transportation Hub is a station constructed beneath fountain and plaza honoring the victims of the 2001 terrorist attacks in New York City, It was designed by Spanish architect Santiago Calatrava and opened in 2016. The above-ground structure, called the Oculus, has been compared to a bird about to take flight, and leads passengers down to the train station below the plaza. Michael Kimmelman, the architecture critic of The New York Times praised the soaring upward view inside the Oculus, but condemned what he called the buildings cost (the most expensive railroad station ever built) "scale, monotony of materials and color, preening formalism and disregard for the gritty urban fabric."[53]

Bridges

[edit]-

Gateshead Millennium Bridge, a tilt bridge for bicycles and pedestrians in Newcastle upon Tyne, England by WilkinsonEyre (2001)

-

Bridge Pavilion in Zaragoza, Spain by Zaha Hadid (2008)

Several of the most prominent contemporary architects, including Norman Foster, Santiago Calatrava, Zaha Hadid, have turned their attention to designing bridges. One of the most remarkable examples of contemporary architecture and engineering is the Millau Viaduct in southern France, designed by architect Norman Foster and structural engineer Michel Virlogeux. The Millau Viaduct crosses the valley of the River Tarn and is part of the A75-A71 autoroute axis from Paris to Béziers and Montpellier. It was formally inaugurated on 14 December 2004.[54] It is the tallest bridge in the world with one mast's summit at 343.0 metres (1,125 ft) above the base of the structure.[55][56]

The British-Iraqi architect Zaha Hadid constructed the Bridge Pavilion in Zaragoza. Spain for an international exposition there in 2008. The bridge, which also served as an exposition hall, is constructed of concrete reinforced with an external layer of fiberglass in different shades of gray. Since the event closed, the bridge has been used to host expositions and shows.

Some smaller new bridges also offer simple but very innovative designs. The Gateshead Millennium Bridge in Newcastle upon Tyne, England, (2004) designed by Michel Virlogeux, to enable pedestrians and cyclists to cross the Tyne River, tilts to one side to permit boats to pass beneath.

Eco-architecture

[edit]-

Primary school of Gando, Burkina Faso by Diébédo Francis Kéré (2001)

-

K2 sustainable apartments in Windsor, Victoria, Australia by DesignInc (2006) features passive solar design, recycled and sustainable materials, photovoltaic cells, wastewater treatment, rainwater collection and solar hot water

-

Ksar Tafilelt in Ghardaïa, Algeria (2006), which won the 1st prize for "best sustainable city" at the 2016 United Nations Climate Change Conference

-

The Passivhaus Goldsmith Street development in Norwich, England by Mikhail Riches (2019). Winner of the 2019 Stirling Prize.

A growing tendency in the 21st century is eco-architecture, also termed sustainable architecture; buildings with features which conserve heat and energy, and sometimes produce their own energy through solar cells and windmills, and use solar heat to generate solar hot water. They also may be built with their own wastewater treatment and sometimes rainwater harvesting Some buildings integrate gardens green walls and green roofs into their structures. Other features of eco-architecture include the use of wood and recycled materials. There are several green building certification programs, the best-known of which is the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design, or LEED rating, which measure the environmental impact of buildings.

Many urban skyscrapers such as 30 Saint Mary Axe in London use a double skin of glass to conserve energy. The double skin and curved shape of the building creates differences in air pressure which help keep the building cooler in summer and warmer in winter, reducing the need for air conditioning.[57]

BedZED, designed by British architect Bill Dunster, is an entire community of eighty-two homes in Hackbridge, near London, built according to eco-architecture principles. Houses face south to take advantage of sunlight and have triple-glazed windows for insulation, a significant portion of the energy comes from solar panels, rainwater is collected and reused, and automobiles are discouraged. BedZED successfully reduced electricity usage by 45 percent and hot water usage by 81 percent of the borough average in 2010, though a successful system for producing heat by burning wood chips proved elusive and difficult.[58]

The CaixaForum Madrid is a museum and cultural center in Paseo del Prado 36, Madrid, by the Swiss architects Herzog & de Meuron, built between 2001 and 2007, is an example of both green architecture and recycling. The main structure is an abandoned brick electric power station, with new floors constructed on top. The new floors are encased in oxidized cast iron, which has a rusty red color as the brick of the old power station below it. The building next to it features a green wall designed by French botanist Patrick Blanc. The red of the top floors contrast with the plants on the wall, while the green wall harmonizes with the botanical garden next door to the cultural center.[59]

Unusual materials are sometimes recycled for use in eco-architecture; they include denim from old blue jeans for insulation, and panels made from paper flakes, baked earth, flax, sisal, or coconut, and particularly fast-growing bamboo. Lumber and stone from demolished buildings are often reclaimed and reused for flooring, while hardware, windows and other details from older buildings are reused.

Topics in contemporary architecture

[edit]- Blobitecture

- Critical Regionalism

- Complementary architecture

- Computer aided design

- Conceptual architecture

- Digital architecture

- Digital morphogenesis

- Deconstructivism

- Futurist architecture

- High-tech architecture

- Industrial chic

- Modern architecture

- Neomodern architecture

- Neo-futurism

- New Classical Architecture

- New Urbanism

- Novelty architecture

- Postmodern architecture

- Sustainable architecture

- Vernacular architecture

See also

[edit]- European Union Prize for Contemporary Architecture, biennial prize by the European Union

- Driehaus Architecture Prize, sometimes nicknamed the anti-Pritzker, established in 2003

- Mathematics and architecture

- World Architecture Festival, annual awards for recently completed buildings

- World Architecture Survey, most important works since 1980 according to a survey of 52 architects and critics

References

[edit]- ^ Creating Your Architectural Style. Pelican Publishing. 15 September 2009. ISBN 978-1-4556-0309-1.

- ^ Urban, Florian (2017). The new tenement. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-315-40244-4. OCLC 1006381281.

- ^ Dickinson, Duo (2017). "Does the New Traditionalism Have A Point?". Common Edge. Retrieved 29 April 2021.

- ^ Wainwright, Oliver (4 March 2020). "The miracle new sustainable product that's revolutionising architecture – stone!". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 April 2021.

- ^ Boylan, Alexis L., ed. (2011). Thomas Kinkade: The Artist in the Mall. Durham [N.C.]: Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-4839-9. OCLC 658200776.

- ^ Crysler, Christopher Greig; Cairns, Stephen; Heynen, Hilde, eds. (2012). The SAGE handbook of architectural theory. Los Angeles: SAGE. ISBN 978-1-84860-039-3. OCLC 797835437.

- ^ Adam, Robert (Fall 2004). "INTBAU Shares ICA&CA's Mission" (PDF). The Forum. Institute of Classical Architecture & Art. Archived (PDF) from the original on Apr 17, 2023.

- ^ Haddad, Elie; Rifkind, David, eds. (2016). A Critical History of Contemporary Architecture: 1960-2010. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-315-26395-3. OCLC 973142750.

- ^ a b Taschen 2016, pp. 108–111.

- ^ Ouroussoff, Nicolai (15 April 2005). "An Expansion gives new life to an old box". The New York Times. p. 392. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ^ "Spotlight: Denver Art Museum" (PDF). Structure Magazine. November 2007. Archived (PDF) from the original on Mar 8, 2023.

- ^ Taschen 2016, p. 392.

- ^ Ouroussoff, Nicolai (12 October 2006). "A Razor-Sharp Profile Cuts Into a Mile-High Cityscape". The New York Times. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

- ^ "Site of Zentrum Paul Klee (English)". Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ^ Rowan Moore (19 October 2014), Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris review – everything and the bling from Frank Gehry The Guardian.

- ^ Paul Goldberger (September 2014), Gehry's Paris Coup Vanity Fair.

- ^ Judy Fayard (23 October 2014), The Louis Vuitton Foundation By the Numbers The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ Christopher Hawthorne (17 October 2014), Review: Gehry's Louis Vuitton Foundation museum is a triumph, but to what end? Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Kimmelman, Michael (19 April 2015). "A New Whitney". The New York Times. Retrieved 24 December 2016.

- ^ Smith, Roberta, "SFMoMA's Expansion Sets a New Standard for Museums", The New York Times, 13 May 2016,

- ^ "SFMOMA's new extension – a gigantic meringue with a hint of Ikea", The Guardian, 29 April 2016

- ^ Nicolai Ouroussoff, "A Vision of a Mobile Society Rolls Off the Assembly Line", The New York Times, 25 December 2005

- ^ France's New Music Temple

- ^ "Philharmonie de Paris - Jean Nouvel's spaceship crashes in France". TheGuardian.com. 15 January 2015. Retrieved 30 December 2016.

- ^ Fonseca-Wollheim, Corinna da (10 January 2017). "Finally, a Debut for the Elbphilharmonie Hall in Hamburg". The New York Times. Retrieved 11 January 2017.

- ^ "Skyscraper". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 25 October 2016.

- ^ Beedle, Lynn S.; Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat (1986). Advances in tall buildings. Van Nostrand Reinhold Company. p. 149. ISBN 978-0-442-21599-6.

- ^ "Burj Khalifa – The Skyscraper Center". Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat.

- ^ Roberts, Ben (13 August 2011). "Crown of the Kingdom". ConstructionWeekOnline. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ Worsley, Giles (28 April 2004). "Glory of the Gherkin". The Daily Telegraph. London.

- ^ "The world's fastest elevator". 6 October 2016.

- ^ "China unveils world's fastest elevator". CNN. 5 October 2016.

- ^ De Bure 2015, p. 208.

- ^ "The Architecture of the Gasometers". Wiener-gasometer.at. Archived from the original on 13 October 2014. Retrieved 16 July 2016.

- ^ "Contemporary Religious Architecture That Rethinks Traditional Spaces for Worship". ArchDaily. 26 June 2018. Retrieved 3 March 2020.

- ^ "CATHEDRAL OF OUR LADY OF THE ANGELS – Rafael Moneo Arquitecto". Retrieved 3 March 2020.

- ^ "The Northern Lights: what you need to know before you plan your trip". Spectator Life. 7 February 2020. Retrieved 3 March 2020.

- ^ "Det Kongelige Bibliotek - The Royal Library". www5.kb.dk. Retrieved 3 March 2020.

- ^ "InGenious Studio Private Limited". www.ingeniousstudio.in. Retrieved 3 March 2020.

- ^ Spaces, Betty Wood, The (22 November 2016). "Indian temple will be the world's tallest religious skyscraper". CNN. Retrieved 3 March 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mann, Charley (16 April 2012). "Work to start on cardboard cathedral". stuff.co.nz. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- ^ "Rain no dampener for New Zealand cardboard cathedral by architect Shigeru Ban". artdaily.org. 29 July 2013. Retrieved 30 July 2013.

- ^ McGuigan, Cathleen (25 February 2013). "Ban's Cardboard Cathedral Rises in Christchurch". Architectural Record. Retrieved 30 July 2013.

- ^ "Nuts and bolts". allianz-arena.de. Archived from the original on 2 August 2013. Retrieved 21 December 2016.

- ^ Filler, Martin, Makers of Modern Architecture, Volume 1, New York: The New York Review of Books, 2007, ISBN 978-1-59017-227-8, p. 226.

- ^ "designbuild network - Beijing National Stadium". Retrieved 19 December 2016.

- ^ Peter Macdiarmid/Getty Images (2 October 2008). "Public building CO2 footprints revealed". The Guardian. Retrieved 14 September 2015.

- ^ Squires, Nick (8 May 2010). "Maltese anger at plans to rebuild Valletta". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 31 August 2015.

- ^ Jonathan Pearlman (3 February 2015). "Frank Gehry unveils 'squashed brown paper bag' building in Sydney". The Telegraph. Telegraph Media Group Limited. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- ^ Planet, Lonely. "Bibliotheca Alexandrina - Lonely Planet". Lonely Planet. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

- ^ Taschen 2016, pp. 210–211.

- ^ "Louis Vuitton Matsuya Ginza Facade Renewal by Jun Aoki and Associates, ArchDaily, October 14, 2014". 14 October 2014. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- ^ "Santiago Calatrava's Transit Hub Is a Soaring Symbol of a Boondoggle", review by Michael Kimmelman, The New York Times, 2 March 2016

- ^ "Millau Viaduct – official website – Home". Leviaducdemillau.com. Archived from the original on 8 July 2013. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- ^ Bridge claims record, Sydney Morning Herald, January 2012

- ^ Spiegel Online (In German) 'Es ist noch nicht fertig'

- ^ Hopkins 2014, p. 210.

- ^ Kucharek, Jan-Carlos (23 July 2010). "Bedding in nicely: BedZed was the ultimate sustainability trailblazer. Nearly a decade on, it may be thriving but it remains an anomaly". BD Reviews: Sustainability (supplement to Building Design).

- ^ "Review of CaixaForum Madrid by Herzog and de Meuron in ArcSpace.com, March 31, 2008". Retrieved 10 January 2017.

Bibliography and Further reading

[edit]- Bony, Anne (2012). L'Architecture Moderne (in French). Larousse. ISBN 978-2-03-587641-6.

- Poisson, Michel (2009). 1000 Immeubles et monuments de Paris (in French). Parigramme. ISBN 978-2-84096-539-8.

- Taschen, Aurelia and Balthazar (2016). L'Architecture Moderne de A à Z (in French). Bibliotheca Universalis. ISBN 978-3-8365-5630-9.

- Prina, Francesca; Demaratini, Demartini (2006). Petite encyclopédie de l'architecture (in French). Solar. ISBN 2-263-04096-X.

- Hopkins, Owen (2014). Les styles en architecture- guide visuel (in French). Dunod. ISBN 978-2-10-070689-1.

- De Bure, Gilles (2015). Architecture contemporaine- le guide (in French). Flammarion. ISBN 978-2-08-134385-6.

External links

[edit]- Rndrd - a website documenting un-built 20th century architectural concept art

- ArchArticulate a website documenting architectural project

![Ksar Tafilelt [fr] in Ghardaïa, Algeria (2006), which won the 1st prize for "best sustainable city" at the 2016 United Nations Climate Change Conference](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/23/Ksar_Tafilelt.jpg/300px-Ksar_Tafilelt.jpg)