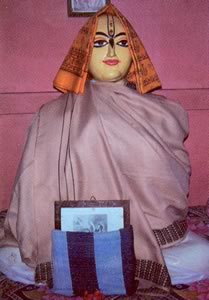

Haridasa Thakur

Namacharya Haridasa Thakur | |

|---|---|

| |

| Personal | |

| Born | 1450[1] |

| Died | Puri, India |

| Religion | Hinduism |

| Sect | Gaudiya Vaishnavism |

| Other names | Mama Thakur Yavana Haridas |

| Religious career | |

| Based in | Mayapur and Puri India |

| Predecessor | Advaita Acharya |

| Successor | Chaitanya Mahaprabhu |

| Ordination | Vaishnava-Diksa |

| Part of a series on |

| Vaishnavism |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on | |

| Hindu philosophy | |

|---|---|

| |

| Orthodox | |

|

|

|

| Heterodox | |

|

|

|

Haridasa Thakur (IAST: Haridāsa Ṭhākura, born 1451 or 1450[1]) was a Vaishnava saint known for playing a part in the initial propagation of Gaudiya Vaishnavism. He is considered to be a known convert of Chaitanya Mahaprabhu, along with Rupa Goswami and Sanatana Goswami. His story of integrity and faith in the face of adversity is told in the Chaitanya Charitamrita (Antya lila).[2] It is believed that Chaitanya Mahaprabhu himself designated Haridasa as nāmācarya, meaning the 'teacher of the Name'.[3] Haridasa Thakura was a devotee of the deity Krishna, and is regarded to have practised the chant of his veneration, the Hare Krishna mantra, 300,000 times daily.[4]

Background

[edit]Haridasa Thakur was a Vaishnava convert from Islam and is now venerated as a Hindu saint. From the beginning of Chaitanya's 16th-century bhakti movement in Bengal, Haridasa and other born Muslims, as well as those of various other faiths, joined together to spread love of God. This openness received a boost from Bhaktivinoda Thakur's vision in the late 19th century and was institutionalized by Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati in his Gaudiya Math in the 20th century.[5] A disciple of Bhaktisiddhanta, Srila A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, is the founder of the International Society for Krishna Consciousness, that celebrates festivals memory of Haridasa Thakura in India and worldwide.[5]

One of the early records of the period by Isana Nagara, (c. 1564), author of the Advaita-prakasa, describes the contemporary condition of the Hindus under 'Ala-ud-din Hussain Shah (1493–1519):

The wicked mlecchas pollute the religion of the Hindus every day. They break the images of the gods into pieces and throw away the articles of worship. They throw into fire Bhagavata Purana and other holy scriptures. They forcibly take away a conch shell and bell of the brahmanas, and lick the sandal paints of their bodies. They urinate like dogs on the sacred Tulasi plant and deliberately pass feces in the Hindu temples. They would throw water from their mouths on the Hindus engaged in worship, and harass the Hindu saints as if they were so many lunatics let large.

Sources

[edit]According to Murari Gupta's Krishna chaitanya charitamrita, mlecchas (a word used for those who do not follow the four regulative principles) are the objects of Lords saving mercy, and as is the case of Haridasa shows, it produces even a great saint. While in contrast to this, another biographer, Kavi Karnapura, in his Krishna Chaitanya Chartamritam Maha-vakyam, written in Sanskrit in 1542, makes no explicit references to Islam, and when referring to the famed saint Haridasa, the author does not speak of his parentage. The earliest biography however, Chaitanya Bhagavata, would avoid use of the word 'mleccha', but would use 'yavana' some fifty times and it appears that the author himself knows more about Islam than an average Hindu will do. While some contend that Haridasa was born of Muslim parents and instead was brought up by them, Chaitanya Bhagavata suggests that apostasy from Islam was a capital offense in Bengal at the time and local qazi became aware of the conversion of Haridasa and brought him before the district governor, also a Muslim. Haridasa defends himself on the basis that there is only one God with many names. In this scene and speech Vaishnava convert Haridasa Thakur refuses to recite from a Muslim scripture, and was therefore sentenced, beaten and left for dead in the river. He however recovered instantly, convincing many he was a pir, a mystical person. As a result, according to the author of Chaitanya Bhagavata, qazi was removed from the office. Some suggest that the episode illustrates, that it was the pressure of communal prestige rather than desire of the governor to instill the law, that resulted in the punishment of Haridasa, when he was caned on the marketplaces. In contrast with it, even if Hussain Shah was depicted as a destructive ruler in Orissa, author attests that many yavanas were devoted to Chaitanya, and would weep over Chaitanya and confess their faith in him.[9]

The elements of the historiographies of Chaitanya Mahaprabhu, Chaitanya Charitamrta and Chaitanya Bhagavata contain main points illustrating the religious bigotry of the Muslims and the consequent persecution of the Hindus, Vaishnavas at the period. Both books retell a famous episode in the life of Chaitanya. He had introduced the public worship in the form of public kirtana and this enraged the local Muslim ruler. To prevent the recurrences of public kirtana the qazi patrolled the streets of Nadiya with a party. After organizing a large civil march, Chaitanya discussed with qazi the situation, who appears in more chastened mood. Author of Chaitanya Charitamrita attributes the change in the quazi's attitude to a miracle. In Chaitanya Chariamrita however it appears describes an overriding order by a superior of qazi to respect sankirtan Chaitanya, that was issued by the Hussain Shah himself, who was impressed with the popularity of the saint.[7] Ishana in chapter 7 of his Advaita-prakasa introduces Haridasa, being originally a Muslim, Haridasa is such an anomalous figure that his presence in the community seems to require explanation. Although Chaitanya himself insisted that anyone who is devoted to Krishna automatically becomes a brahmana, there were only very few non-brahmana, who played a role of leadership in the young group of Gaudiya Vaishnava movement. Ishana uses a reference from Bhagavata Purana (S.Bhag 10.13-14) to support high place of Haridasa in Gaudiya Vaishnavism, and to illustrate spiritual power of his guru, Advaita, to elevate him to such a position.[10]

Early life

[edit]Haridasa was born in the village of Buron (Budana),[1] in what is today the Satkhira District of Khulna Division, Bangladesh. Haridasa was 35 years older than Chaitanya Mahaprabhu and his prayers along with prayers of Advaita Acharya were the reason for Chaitanya Mahaprabhu descent.[11] Ishana Nagara in his book Advaita Prakasha, explains in length that Haridasa Thakur was a follower of Advaita Acharya and also his close friend, he was raised in a Muslim family and then converted to Vaishnavism as a young man. Advaita Acharya indicates that becoming a Vaishnava, regardless of one's background, removes all past conditioning.[12]

When Haridasa Thakura was a young devotee of the Lord, he was allured by the incarnation of Maya-devi, but Haridasa passed the test because of his unalloyed devotion to Lord Krishna.[13] He also believed to have stayed and chanted in a cave with a notorious snake, however, seemed unaffected by all of this. He did not even seem to be aware of the snake's presence.[4]

Haridasa first became associated with Advaita Acharya. Haricarana Dasa, the biographer of Advaita Acharya says that all the demigods in heaven heard prayers of Advaita and reveal themselves to him, therefore when Advaita saw Haridasa, he could recognize that he was Brahma incarnate and named him Hari-dasa (literary meaning servant of God). He instructs Haridasa to recite Krishna's names and assures him that Krishna will always show mercy to Haridasa. The close relationship between the two and the fact that Advaita was feeding a Muslim, became a subject of malicious gossip. This apparent anomaly created a stir in the local brahmana community. Others couldn't understand why a ascetic was disregarding a convention of staying away from Muslims. The fact that community was disturbed is reflected in both Chaitanya Charitamrita and in Chaitanya Bhagavata. Haricarana Dasa, according to historical records, confirms that while Advaita was from the higher ranks of Bengali brahmana community, he ignored the facts about Haridasa's background, impressed with the young man's devotion. While others became upset with Advaita's attention to Haridasa, and threatened to excommunicate Advaita, Advaita tells Haridasa to pay no attention to 'those petty people'.

Legend says that one morning, Advaita schedules a fire ceremony, agnihotra. When preparations for this ritual is about to begin, there is no fire to be found in the whole town. The ceremony is thus stranded and couldn't proceed. Advaita points out to all local brahmana priests that if priests are true to their religious teachings, there must be fire, and tells them to approach Haridasa with dried grass in their hands. When Haridasa kindles the grasses by his potency, he also, according to this record, manifests his four-faced Brahma-like form. While Agni, the deity of Vedas responsible for fire, should have been under the control of the brahmanas, it's only the Muslim born Haridasa who ignites the fires, by the power of his devotion, 'the purity those born brahmana have lost'.[14]

Teachings

[edit]

According to the philosophy of the holy name given by Haridasa Thakura, if you are on the platform of namabhasa (early or reflective stage of the pure chanting), it gives the chanter liberation, moksa.[15] Whereas pure chanting gives prema, or 'Love of God'.

An episode from Chaitanya Charitamrita illustrates different side of the life of Haridasa Thakura, and does not allude to the trial of the Haridasa by the Muslim ruler, but gives details of a sakta brahmana, who would hire a harlot to try (unsuccessfully) to seduce the celibate saint. In this story the avenging instruments of divine justice are none other than the agents of the Muslim king, who eventually punishes Ramachandra Khan.(CC Antya. 3.98-163)[16]

Haridasa Thakur was chanting mantra consisting of the names Hare, Krishna and Rama. Hare Krishna mantra appears originally in the Kali-Saṇṭāraṇa Upaniṣad:

Hare Krishna Hare Krishna

Krishna Krishna Hare Hare

Hare Rama Hare Rama

Rama Rama Hare Hare

It is often referred to as the "Maha Mantra" (great mantra) by practitioners.

Following the footsteps of Haridasa Thakur in 1966, A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada established ISKCON (the International Society for Krishna Consciousness), a branch of the Brahma-Madhva-Gaudiya Vaishnava sampradaya, and introduced the Hare Krishna mantra to the West, described as: "an easy yet sublime way of liberation in the Age of Kali."

Preaching of Hare Krishna chanting

[edit]He was asked to join forces with Nityananda who was older than Chaitanya by some eight years, and he believed to infuse into the movement a great passion. Haridasa and Nityananda are known for conversion of two notorious scoundrels, Jagai and Madhai, of Navadvipa into the new faith.[17] They are considered important lieutenants in the campaign for spreading the sankirtana movement, chanting of the holy names: Brahma, in the form of Haridasa Thakura, and later, Balarama as Nityananda.[18]

Other associates of Chaitanya called Haridas

[edit]Different associates of Chaitanya with this name include:

- 1. Haridasa Pandita (also known as Sri Raghu Gopala and as Sri Rasa-manjari), a disciple of Sri Ananta Acaryam. He is according to Tarapada Mukherjee is of a later generation.[19][20] The fact that he is mentioned in the verses derived from Chaitanya Charitamrita, Adi 8 as a listener rather than participants in lila distinguishes them from contemporaries like that of Rupa and the others mentioned who were direct associates of Chaitanya. However according to Krishnadasa Kaviraja, the book which was read in the meetings of the first generation of Chaitanya followers in Vrindavan was the Bhagavata Purana itself and not Chaitanya's life story.[21]

- 2. Chhota Haridas who accompanied Chaitanya on the journey to South India. It is believed that Chaitanya forsook the company of Chhota-Haridas because of an incident, that was against strict principles of a detached saint.[22]

Identity

[edit]

Haridasa Thakur in Gaudiya Vaishnavism is believed to be a combined incarnation of Brahma Mahatapa, the son of Richika Muni and Prahlada. The respected Murari Gupta has written in his Chaitanya Charitamrita that this sage's son picked a tulasi leaf and offered it to Krishna without having washed it first. His father then cursed him to become a mleccha in his next life. He was thus born as Haridasa, a great devotee. (Gaura-ganoddesha-dipika 93-95)[23]

Nabadwip-dhama-mahatmya by Bhaktivinoda Thakur has written the following account of how Brahma became Haridasa Thakur:

In Dvapara Yuga, Nandanandana Sri Krishna was herding the cows through Vraja Dham in the company of his cowherd boyfriends when Brahma decided to test the Lord out of a desire to see his majestic form and opulences. He stole both Krishna's cows and calves, as well as his friends and hid them for a year in the caves of Sumeru Mountain. But a year later, when Brahma returned to Vraja, he was astonished to see that Krishna was still there with both his friends and cattle. Brahma immediately understood his error and began to regret his rash action. He fell down at Krishna's feet and begged him for forgiveness; Krishna responded by mercifully revealing his divine opulence. He who appears in the Dvapara Yuga as Nandanandana Sri Krishna, descends again in the Kali Yuga as Gauranga, taking on the mood and bodily luster of Radharani in order to display the most magnanimous pastimes. Brahma was afraid that he might commit the same offense during Gaura's incarnation so he went to Antardvipa, the central island of Nabadwip, and began to meditate. The Lord was able to understand his mind and so came to him in the form of Gauranga and said, "During my incarnation as Gaura, you will be born in a family of mlecchas and will preach the glories of the Holy Name and bring auspiciousness to all the living beings.

From the above it is understood that he was an incarnation of the secondary creator Brahma. It is said that in order to overcome his pride, he asked for a birth in a lowly family. Similar description is found in Advaita-vilasa.[23]

Last years

[edit]Last years Haridasa has spent in Jagannatha Puri as a close associate of Chaitanya Mahaprabhu. One time Caitanya Mahaprabhu took Haridasa Thakura within the flower garden, and in a very secluded place He showed him his residence. He asked Haridasa to remain there and chant the Hare Krishna mantra, and said that He would come there to meet him every day. “Remain here peacefully and look at the cakra on top of the temple and offer obeisances. As for as your prasadam is concerned, I shall arrange to have it sent here”.[24] Although Haridasa was not allowed to visit the temple because of the custom, Chaitanya promised to come and see him daily. To the belief of Gaudiya Vaishnavas this indicates that Haridasa Thakura was so advanced in spiritual life that although he was considered unfit to enter the temple of Jagannatha, he's being visited by the lord every day. Prabhupada however on a number of occasions states that one should not imitate the behavior of Haridasa Thakura. He says the spiritual master gives different orders to different disciples:[25]

Death (Disappearance)

[edit]He reasons ill who tells that Vaishnavas die

When thou art living still in Sound!

The Vaishnavas die to live & living try

To spread the holy name around!

Verse by Bhaktivinoda Thakura on the tomb of Haridasa Thakura at Puri, India, published in Swami Prabhupada's Narada Bhakti Sutra, (3.50, purport).

It is believed that Haridasa was buried on the ocean shore by Chaitanya himself.[26] Dr. A. N. Chatterjee makes a point in his doctoral thesis entitled "Chaitanya's impact on medieval Indian society" that death of Haridasa Thakura is one of the most important incidents which deserve mention when dealing with the last few years of Chaitanya Mahaprabhus life.[22] Haridasa dies after most of other Gaudiya Vaishnavas depart home from Puri, he collapses one day while singing Krishnas name. He is then placing a foot of Chaitanya Mahaprabhu on his chest and dies crying out "Sri Krishna Chaitanya".[27]

Even when mahatmas, great souls, do appear in human society, they are often not appreciated or understood. Illustrating Gaudiya Vaishnava perspective on it Prabhupada writes:

Sometimes devotees are personally attacked with violence. Lord Jesus Christ was crucified, Haridasa Thakura was caned in twenty-two marketplaces, and Lord Chaitanya's principal assistant, Nityananda, was violently attacked by Jagai and Madhai.... Although a sadhu is not inimical toward anyone, the world is so ungrateful that even a sadhu has many enemies.

— [SB 3.25.21, purport]

However, if one gets the association of a such mahatma and is receptive to his blessings, it is believed that one will infallibly be benefited.[28]

Books

[edit]Chaudhuri, J. (1960). Mahaprabhu-Haridasam: The Mahaprabhu-Haridasam; a new Sanskrit drama on the life of Haridasa, one of the greatest devotees of Sri Krishna Chaitanya Mahaprabhu of Bengal.

Further information

[edit]For more details of his life story see Chaitanya Bhagavata In this text Haridasa's tribulations are given in detail.[29]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Rebecca Manring (2005). Reconstructing tradition: Advaita Ācārya and Gauḍīya Vaiṣṇavism at the cusp of the twentieth century. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 177. ISBN 978-0-231-12954-1.

- ^ Dimock, E.C. Jr (1963). "Doctrine and Practice among the Vaishnavas of Bengal". History of Religions. 3 (1): 106–127. doi:10.1086/462474. JSTOR 1062079. S2CID 162027021.

- ^ H.D. Goswami. "For Whom Does Hinduism Speak?". Archived from the original on 17 May 2008. Retrieved 2 June 2008.

- ^ a b Suman N. Bhat (2007). Biographies of Saints of the Masses. Sura Books. p. 18. ISBN 978-81-7478-630-2.

- ^ a b Sherbow, P.H. (2004). "AC Bhaktivedanta Swami's Preaching In The Context Of Gaudiya Vaishnavism". The Hare Krishna Movement: The Postcharismatic Fate of a Religious Transplant: 139.

- ^ Isana Encyclopaedia of Historiography ISBN 81-261-2305-2

- ^ a b M.M. Rahman. (2006). Encyclopaedia of Historiography. Anmol Publications Pvt Ltd. pp. 140–141. ISBN 978-81-261-2305-6.

- ^ The State and Society in Northern India, 1206-1526 p.33 Anil Chandra Banerjee, 1892 Chapter Page 1 The Theocratic State

- ^ Parasher-Sen, Aloka (2004). Subordinate and marginal groups in early India. Oxford [Oxfordshire]: Oxford University Press. pp. 412–415. ISBN 978-0-19-566542-0.

- ^ Rebecca Manring (2005). Reconstructing tradition: Advaita Ācārya and Gauḍīya Vaiṣṇavism at the cusp of the twentieth century. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 168. ISBN 978-0-231-12954-1.

- ^ Rosen, S.J. (2004). "Who Is Shri Chaitanya Mahaprabhu?". The Hare Krishna Movement: The Postcharismatic Fate of a Religious Transplant. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-12256-6. Retrieved 2 June 2008.

- ^ Pechilis, Karen (2004). The graceful guru: Hindu female gurus in India and the United States. Oxford [Oxfordshire]: Oxford University Press. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-19-514538-0.

- ^ Bhaktivedanta Swami, A. C. (1972). Bhagavad-gita As It Is Archived 13 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine, second edition. Los Angeles: Bhaktivedanta Book Trust p.136.

- ^ Rebecca Manring (2005). Reconstructing tradition: Advaita Ācārya and Gauḍīya Vaiṣṇavism at the cusp of the twentieth century. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 61–63. ISBN 978-0-231-12954-1.

- ^ Dasa, R.S. (2000). "Restoring the Authority of the GBC'". ISKCON Communications Journal. 8 (1). Archived from the original on 4 May 2007. Retrieved 2 June 2008.

- ^ Parasher-Sen, Aloka (2004). Subordinate and marginal groups in early India. Oxford [Oxfordshire]: Oxford University Press. p. 422. ISBN 978-0-19-566542-0.

- ^ Chakravarti, R. (1977). "Gaudiya Vaishnavism in Bengal". Journal of Indian Philosophy. 5 (1): 107–149. doi:10.1007/BF02431707. S2CID 189836264.

- ^ Rebecca Manring (2005). Reconstructing tradition: Advaita Ācārya and Gauḍīya Vaiṣṇavism at the cusp of the twentieth century. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 94. ISBN 978-0-231-12954-1.

- ^ Mukherjee, Tarapada. 'ChaitanyacaritAmritamahAkAvya', Caturanga, May 1985 (Calcutta), 57-70.

- ^ Mukherjee, Tarapada. 'Chaitanyacaritamriter racanakal evam vrajer gaudiyasampradaya', Sahitya Parishad Patrika, 87.1, 1987 (Calcutta), 1-39.

- ^ Brzezinski, J.K. (1990). "The Authenticity of the" Caitanyacaritamrtamahakavya". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. 53 (3): 469–490. doi:10.1017/s0041977x00151365. JSTOR 618120. S2CID 163362900.

- ^ a b A. N. Chatterjee (1984). Srikṛṣṇa Caitanya: A Historical Study on Gauḍiya Vaiṣṇavism. ISBN 9780836413212. Retrieved 3 June 2008.p. 27

- ^ a b B.V. Tirtha (2001). Chaitanya: His Life and Associates. Mandala Publishing. ISBN 978-1-886069-28-2.

- ^ Chaitanya Charitamrita (Madhya-lila 11.195)

- ^ Goswami, Satsvarupa Dasa. "Tachycardia--Part 10". www.sdgonline.org. Retrieved 7 July 2008.

- ^ Stewart, T.K. (1991). "When Biographical Narratives Disagree: the Death of Krishna Chaitanya". Numen. 38 (2): 231–260. doi:10.1163/156852791X00141. JSTOR 3269835.

- ^ Rebecca Manring (2005). Reconstructing tradition: Advaita Ācārya and Gauḍīya Vaiṣṇavism at the cusp of the twentieth century. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 185. ISBN 978-0-231-12954-1.

- ^ Narada-Bhakti-Sutra Archived 30 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine: The Secrets of Transcendental Love, A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada (Author), Satsvarupa Dasa Goswami (Author) ISBN 0-89213-273-6 p. 96

- ^ Stewart, Tony K. "Chaitanya Bhagavata". banglapedia. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

External links

[edit]- "Haridasa Thakura". www.stephen-knapp.com. Retrieved 2 June 2008.

- Kaunteya Das. "Tulasi at Home". namahata.org. Archived from the original on 27 May 2008. Retrieved 2 June 2008.

- "Haridas Thakur". ISKCON video presentations. Archived from the original on 14 February 2016. Retrieved 2 June 2008.

- "Parishad: Srila Haridasa Thakur". Sep 25, 2007. KUALA LUMPUR. 25 September 2007. Retrieved 2 June 2008.

- Swami, R. "The departure of Haridas Thakura". www.btswami.com. Archived from the original on 2 November 2005. Retrieved 2 June 2008.

- "Haridas". www.dharmakshetra.com. Archived from the original on 5 September 2008. Retrieved 2 June 2008.

- "Premadhavani - Words of Love". btg.krishna.com. Archived from the original on 26 November 2007. Retrieved 2 June 2008.

- "Puri Orissa". www.vegetarian-restaurants.net. Archived from the original on 9 March 2008. Retrieved 2 June 2008.

- 1450s births

- 16th-century Hindu religious leaders

- Converts to Hinduism from Sunni Islam

- Devotees of Krishna

- Devotees of Jagannath

- Kirtan performers

- Medieval Hindu religious leaders

- Spiritual teachers

- Gaudiya religious leaders

- Indian former Sunni Muslims

- Indian Vaishnavites

- Vaishnava saints

- Scholars from Odisha

- Converts to Hinduism from Islam