Marshall Islands

Republic of the Marshall Islands Aolepān Aorōkin M̧ajeļ | |

|---|---|

| Motto: "Jepilpilin ke ejukaan" "Accomplishment through joint effort" | |

| Anthem: "Forever Marshall Islands! (English)" | |

| |

| Status | Associated State |

| Capital and largest city | Majuro[1] |

| Official languages | |

| Ethnic groups (2006) |

|

| Demonym(s) | Marshallese |

| Government | Unitary parliamentary republic |

| Hilda Heine | |

| Legislature | Nitijela |

| Independence | |

• Self-government | 1979 |

| October 21, 1986 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 181.43 km2 (70.05 sq mi) (213th) |

• Water (%) | n/a (negligible) |

| Population | |

• 2009 estimate | 72,191[2] (205th) |

• 2011 census | 53,158 |

• Density | 293.0/km2 (758.9/sq mi) (28th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2001 estimate |

• Total | $115 million (220th) |

• Per capita | $2,900a (195th) |

| Currency | United States dollar (USD) |

| Time zone | UTC+12 (MHT) |

| Date format | MM/DD/YYYY |

| Drives on | right |

| Calling code | +692 |

| ISO 3166 code | MH |

| Internet TLD | .mh |

| |

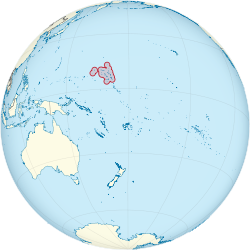

The Marshall Islands, officially the Republic of the Marshall Islands (Template:Lang-mh),[note 1] is an island country located near the equator in the Pacific Ocean, slightly west of the International Date Line. Geographically, the country is part of the larger island group of Micronesia. The country's population of 53,158 people (at the 2011 Census) is spread out over 29 coral atolls,[2] comprising 1,156 individual islands and islets. The islands share maritime boundaries with the Federated States of Micronesia to the west, Wake Island to the north,[note 2] Kiribati to the south-east, and Nauru to the south. About 27,797 of the islanders (at the 2011 Census) live on Majuro, which contains the capital.[2]

Micronesian colonists gradually settled the Marshall Islands during the 2nd millennium BC, with inter-island navigation made possible using traditional stick charts. Islands in the archipelago were first explored by Europeans in the 1520s, with Spanish explorer Alonso de Salazar sighting an atoll in August 1526. Other expeditions by Spanish and English ships followed. The islands derive their name from British explorer John Marshall, who visited in 1788. The islands were historically known by the inhabitants as "jolet jen Anij" (Gifts from God).[3]

The European powers recognized Spanish sovereignty over the islands in 1874. They had been part of the Spanish East Indies formally since 1528. Later, Spain sold the islands to the German Empire in 1884, and they became part of German New Guinea in 1885. In World War I the Empire of Japan occupied the Marshall Islands, which in 1919 the League of Nations combined with other former German territories to form the South Pacific Mandate. In World War II, the United States conquered the islands in the Gilbert and Marshall Islands campaign. Along with other Pacific Islands, the Marshall Islands were then consolidated into the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands governed by the US. Self-government was achieved in 1979, and full sovereignty in 1986, under a Compact of Free Association with the United States. Marshall Islands has been a United Nations member state since 1991.

Politically, the Marshall Islands is a presidential republic in free association with the United States, with the US providing defense, subsidies, and access to U.S. based agencies such as the FCC and the USPS. With few natural resources, the islands' wealth is based on a service economy, as well as some fishing and agriculture; aid from the United States represents a large percentage of the islands' gross domestic product. The country uses the United States dollar as its currency.

The majority of the citizens of the Marshall Islands are of Marshallese descent, though there are small numbers of immigrants from the United States, China, Philippines and other Pacific islands. The two official languages are Marshallese, which is a member of the Malayo-Polynesian languages, and English. Almost the entire population of the islands practises some religion, with three-quarters of the country either following the United Church of Christ – Congregational in the Marshall Islands (UCCCMI) or the Assemblies of God.

History

Micronesians settled the Marshall Islands in the 2nd millennium BC, but there are no historical or oral records of that period. Over time, the Marshall Island people learned to navigate over long ocean distances by canoe using traditional stick charts.[4]

Spanish colony

Spanish explorer Alonso de Salazar was the first European to see the islands in 1526, commanding the ship Santa Maria de la Victoria, the only surviving vessel of the Loaísa Expedition. On August 21, he sighted an island (probably Taongi) at 14°N that he named "San Bartolome".[5]

On September 21, 1529, Álvaro de Saavedra Cerón commanded the Spanish ship Florida, on his second attempt to recross the Pacific from the Maluku Islands. He stood off a group of islands from which local inhabitants hurled stones at his ship. These islands, which he named "Los Pintados", may have been Ujelang. On October 1, he found another group of islands where he went ashore for eight days, exchanged gifts with the local inhabitants and took on water. These islands, which he named "Los Jardines", may have been Enewetak or Bikini Atoll.[6][7]

The Spanish ship San Pedro and two other vessels in an expedition commanded by Miguel López de Legazpi discovered an island on January 9, 1530, possibly Mejit, at 10°N, which they named "Los Barbudos". The Spaniards went ashore and traded with the local inhabitants. On January 10, the Spaniards sighted another island that they named "Placeres", perhaps Ailuk; ten leagues away, they sighted another island that they called "Pajares" (perhaps Jemo). On January 12, they sighted another island at 10°N that they called "Corrales" (possibly Wotho). On January 15, the Spaniards sighted another low island, perhaps Ujelang, at 10°N, where they described the people on "Barbudos".[8][9] After that, ships including the San Jeronimo, Los Reyes and Todos los Santos also visited the islands in different years.

The islanders had no immunity to European diseases and many died as a result of contact with the Spanish.[10]

Other European contact

Captain John Charles Marshall and Thomas Gilbert visited the islands in 1788. The islands were named for Marshall on Western charts, although the natives have historically named their home "jolet jen Anij" (Gifts from God).[3] Around 1820, Russian explorer Adam Johann von Krusenstern and the French explorer Louis Isidore Duperrey named the islands after John Marshall, and drew maps of the islands. The designation was repeated later on British maps.[citation needed] In 1824 the crew of the American whaler Globe mutinied and some of the crew put ashore on Mulgrave Island. One year later, the American schooner Dolphin arrived and picked up two boys, the last survivors of a massacre by the natives due to their brutal treatment of the women.[11]: 2

A number of vessels visiting the islands were attacked and their crews killed. In 1834, Captain DonSette and his crew were killed. Similarly, in 1845 the schooner Naiad punished a native for stealing with such violence that the natives attacked the ship. Later that year a whaler's boat crew were killed. In 1852 the San Francisco-based ships Glencoe and Sea Nymph were attacked and everyone aboard except for one crew member were killed. The violence was usually attributed as a response to the ill treatment of the natives in response to petty theft, which was a common practice. In 1857, two missionaries successfully settled on Ebon, living among the natives through at least 1870.[11]: 3

The international community in 1874 recognized the Spanish Empire's claim of sovereignty over the islands as part of the Spanish East Indies.

German protectorate

Although the Spanish Empire had a residual claim on the Marshalls in 1874, when she began asserting her sovereignty over the Carolines, she made no effort to prevent the German Empire from gaining a foothold there. Britain also raised no objection to a German protectorate over the Marshalls in exchange for German recognition of Britain's rights in the Gilbert and Ellice Islands.[12] On October 13, 1885, SMS Nautilus under Captain Rötger brought German emissaries to Jaluit. They signed a treaty with Kabua, whom the Germans had earlier recognized as "King of the Ralik Islands," on October 15.

Subsequently, seven other chiefs on seven other islands signed a treaty in German and Marshallese and a final copy witnessed by Rötger on November 1 was sent to the German Foreign Office.[13] The Germans erected a sign declaring a "Imperial German Protectorate" at Jaluit. It has been speculated that the crisis over the Carolines with Spain, which almost provoked a war, was in fact "a feint to cover the acquisition of the Marshall Islands", which went almost unnoticed at the time, despite the islands being the largest source of copra in Micronesia.[14] Spain sold the islands to Germany in 1884 through papal mediation.

A German trading company, the Jaluit Gesellschaft, administered the islands from 1887 until 1905. They conscripted the islanders as laborers and mistreated them.[10] After the German–Spanish Treaty of 1899, in which Germany acquired the Carolines, Palau, and the Marianas from Spain, Germany placed all of its Micronesian islands, including the Marshalls, under the governor of German New Guinea.

Catholic missionary Father A. Erdland, from the Sacred Heart Jesu Society based in Hiltrup, Germany, lived on Jaluit from around 1904 to 1914. He was very interested in the islands and conducted considerable research on the Marshallese culture and language. He published a 376-page monograph on the islands in 1914. Father H. Linckens, another missionary from the Sacred Heart of Jesu Society visited the Marshall Islands in 1904 and 1911 for several weeks. He published a small work in 1912 about the Catholic mission activities and the people of the Marshall Islands.[15]

Japanese mandate

Under German control, and even before then, Japanese traders and fishermen from time to time visited the Marshall Islands, although contact with the islanders was irregular. After the Meiji Restoration (1868), the Japanese government adopted a policy of turning the Japanese Empire into a great economic and military power in East Asia.

In 1914, Japan joined the Entente during World War I and captured various German Empire colonies, including several in Micronesia. On September 29, 1914, Japanese troops occupied the Enewetak Atoll, and on September 30, 1914, the Jaluit Atoll, the administrative centre of the Marshall Islands.[16] After the war, on June 28, 1919, Germany signed (under protest) the Treaty of Versailles. It renounced all of its Pacific possessions,[17] including the Marshall Islands. On December 17, 1920, the Council of the League of Nations approved the South Pacific Mandate for Japan to take over all former German colonies in the Pacific Ocean located north of the Equator.[16] The Administrative Centre of the Marshall Islands archipelago remained Jaluit.

The German Empire had primarily economic interests in Micronesia. The Japanese interests were in land. Despite the Marshalls' small area and few resources, the absorption of the territory by Japan would to some extent alleviate Japan's problem of an increasing population with a diminishing amount of available land to house it.[18] During its years of colonial rule, Japan moved more than 1,000 Japanese to the Marshall Islands although they never outnumbered the indigenous peoples as they did in the Mariana Islands and Palau.

The Japanese enlarged administration and appointed local leaders, which weakened the authority of local traditional leaders. Japan also tried to change the social organization in the islands from matrilineality to the Japanese patriarchal system, but with no success.[18] Moreover, during the 1930s, one third of all land up to the high water level was declared the property of the Japanese government. Before Japan banned foreign traders on the archipelago, the activities of Catholic and Protestant missionaries were allowed.[18]

Indigenous people were educated in Japanese schools, and studied the Japanese language and Japanese culture. This policy was the government strategy not only in the Marshall Islands, but on all the other mandated territories in Micronesia. On March 27, 1933, Japan handed in its notice at the League of Nations,[19][clarification needed] but continued to manage the islands, and in the late 1930s began building air bases on several atolls. The Marshall Islands were in an important geographic position, being the easternmost point in Japan's defensive ring at the beginning of World War II.[18][20]

World War II

In the months before the attack on Pearl Harbor, Kwajalein Atoll was the administrative center of the Japanese 6th Fleet Forces Service, whose task was the defense of the Marshall Islands.[21]

In World War II, the United States, during the Gilbert and Marshall Islands campaign, invaded and occupied the islands in 1944, destroying or isolating the Japanese garrisons. In just one month in 1944, Americans captured Kwajalein Atoll, Majuro and Enewetak, and, in the next two months, the rest of the Marshall Islands, except for Wotje, Mili, Maloelap and Jaluit.

The battle in the Marshall Islands caused irreparable damage, especially on Japanese bases. During the American bombing, the islands' population suffered from lack of food and various injuries. U.S. attacks started in mid-1943, and caused half the Japanese garrison of 5,100 people in the Mili Atoll to die from hunger by August 1945.[22]

Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands

Following capture and occupation by the United States during World War II, the Marshall Islands, along with several other island groups located in Micronesia, passed formally to the United States under United Nations auspices in 1947 as part of the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands established pursuant to Security Council Resolution 21.

Nuclear testing during the Cold War

From 1946 to 1958, the early years of the Cold War, the United States tested 67 nuclear weapons at its Pacific Proving Grounds located in the Marshall Islands,[23] including the largest atmospheric nuclear test ever conducted by the U.S., code named Castle Bravo.[24] "The bombs had a total yield of 108,496 kilotons, over 7,200 times more powerful than the atomic weapons used during World War II."[25] With the 1952 test of the first U.S. hydrogen bomb, code named "Ivy Mike," the island of Elugelab in the Enewetak atoll was destroyed. In 1956, the United States Atomic Energy Commission regarded the Marshall Islands as "by far the most contaminated place in the world."[26]

Nuclear claims between the U.S. and the Marshall Islands are ongoing, and health effects from these nuclear tests linger.[24] Project 4.1 was a medical study conducted by the United States of those residents of the Bikini Atoll exposed to radioactive fallout. From 1956 to August 1998, at least $759 million was paid to the Marshallese Islanders in compensation for their exposure to U.S. nuclear weapon testing.[27]

Independence

In 1979, the Government of the Marshall Islands was officially established and the country became self-governing.

In 1986, the Compact of Free Association with the United States entered into force, granting the Republic of the Marshall Islands (RMI) its sovereignty. The Compact provided for aid and U.S. defense of the islands in exchange for continued U.S. military use of the missile testing range at Kwajalein Atoll. The independence procedure was formally completed under international law in 1990, when the UN officially ended the Trusteeship status pursuant to Security Council Resolution 683.

Climate change

In 2008, extreme waves and high tides caused widespread flooding in the capital city of Majuro and other urban centres, 3 feet (0.91 m) above sea level. On Christmas morning in 2008, the government declared a state of emergency.[28] In 2013, heavy waves once again breached the city walls of Majuro.

In 2013, the northern atolls of the Marshall Islands experienced drought. The drought left 6,000 people surviving on less than 1 litre (0.22 imp gal; 0.26 US gal) of water per day. This resulted in the failure of food crops and the spread of diseases such as diarrhea, pink eye, and influenza. These emergencies resulted in the United States President declaring an emergency in the islands. This declaration activated support from US government agencies under the Republic's "free association" status with the United States, which provides humanitarian and other vital support.[29]

Following the 2013 emergencies, the Minister of Foreign Affairs Tony de Brum was encouraged by the Obama administration in the United States to turn the crises into an opportunity to promote action against climate change. De Brum demanded new commitment and international leadership to stave off further climate disasters from battering his country and other similarly vulnerable countries. In September 2013, the Marshall Islands hosted the 44th Pacific Islands Forum summit. De Brum proposed a Majuro Declaration for Climate Leadership to galvanize concrete action on climate change.[30]

Government

The government of the Marshall Islands operates under a mixed parliamentary-presidential system as set forth in its Constitution.[31] Elections are held every four years in universal suffrage (for all citizens above 18), with each of the twenty-four constituencies (see below) electing one or more representatives (senators) to the lower house of RMI's unicameral legislature, the Nitijela. (Majuro, the capital atoll, elects five senators.) The President, who is head of state as well as head of government, is elected by the 33 senators of the Nitijela. Four of the five Marshallese presidents who have been elected since the Constitution was adopted in 1979 have been traditional paramount chiefs.[32]

Legislative power lies with the Nitijela. The upper house of Parliament, called the Council of Iroij, is an advisory body comprising twelve tribal chiefs. The executive branch consists of the President and the Presidential Cabinet, which consists of ten ministers appointed by the President with the approval of the Nitijela. The twenty-four electoral districts into which the country is divided correspond to the inhabited islands and atolls. There are currently four political parties in the Marshall Islands: Aelon̄ Kein Ad (AKA), United People's Party (UPP), Kien Eo Am (KEA) and United Democratic Party (UDP). Rule is shared by the AKA and the UDP. The following senators are in the legislative body:

- Ailinglaplap Atoll – Christopher Loeak (AKA), Ruben R. Zackhras (UDP)

- Ailuk Atoll – Maynard Alfred (UDP)

- Arno Atoll – Nidel Lorak (UDP), Jiba B. Kabua (AKA)

- Aur Atoll – Hilda C. Heine (AKA)

- Ebon Atoll – John M. Silk (UDP)

- Enewetak Atoll – Jack J. Ading (KEA)

- Jabat Island – Kessai H. Note (UDP)

- Jaluit Atoll – Rien J. Morris (UDP), Alvin T. Jacklick (KEA)

- Kili Island – Vice Speaker Tomaki Juda (UDP)

- Kwajalein Atoll – Michael Kabua (AKA), Tony A. deBrum (AKA), Jeban Riklon (AKA)

- Lae Atoll – Thomas Heine (AKA)

- Lib Island – Jerakoj Jerry Bejang (AKA)

- Likiep Atoll – Speaker Donald F. Capelle (UDP)

- Majuro Atoll – Phillip H. Muller (AKA), David Kramer (KEA), Brenson S. Wase (KEA), Anthony Muller (KEA), Jurelang Zedkaia (KEA)

- Maloelap Atoll – Michael Konelios (UDP)

- Mejit Island – Dennis Momotaro (AKA)

- Mili Atoll – Wilbur Heine (AKA)

- Namdrik Atoll – Mattlan Zackhras (UDP)

- Namu Atoll – Tony Aiseia (AKA)

- Rongelap Atoll – Kenneth A. Kedi (IND)

- Ujae Atoll – Caious Lucky (AKA)

- Utirik Atoll – Hiroshi V. Yamamura (AKA)

- Wotho Atoll – David Kabua (AKA)

- Wotje Atoll – Litokwa Tomeing (UPP)

Foreign affairs and defense

The Compact of Free Association with the United States gives the U.S. sole responsibility for international defense of the Marshall Islands. It allows islanders to live and work in the United States and establishes economic and technical aid programs.

The Marshall Islands was admitted to the United Nations based on the Security Council's recommendation on August 9, 1991, in Resolution 704 and the General Assembly's approval on September 17, 1991, in Resolution 46/3.[33] In international politics within the United Nations, the Marshall Islands has often voted consistently with the United States with respect to General Assembly resolutions.[34]

On 28 April 2015, the Iranian navy seized the Marshall Island-flagged MV Maersk Tigris near the Strait of Hormuz. The ship had been chartered by Germany's Rickmers Ship Management, which stated that the ship contained no special cargo and no military weapons. The ship was reported to be under the control of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard according to the Pentagon. Tensions escallated in the region due to the intensifying of Saudi-led coalition attacks in Yemen. The Pentagon reported that the destroyer USS Farragut and a maritime reconnaissance aircraft were dispatched upon receiving a distress call from the ship Tigris and it was also reported that all 34 crew members were detained. US defense officials have said that they would review U.S. defense obligations to the Government of the Marshall Islands in the wake of recent events and also condemned the shots fired at the bridge as "inappropriate". It was reported in May 2015 that Tehran would release the ship after it paid a penalty.[35][36]

Geography

The islands are located about halfway between Hawaii and Australia,[3] north of Nauru and Kiribati, east of the Federated States of Micronesia, and south of the U.S. territory of Wake Island, to which it lays claim.[37] The atolls and islands form two groups: the Ratak (sunrise) and the Ralik (sunset). The two island chains lie approximately parallel to one another, running northwest to southeast, comprising about 750,000 square miles (1,900,000 km2) of ocean but only about 70 square miles (180 km2) of land mass.[3] Each includes 15 to 18 islands and atolls.[11] The country consists of a total of 29 atolls and five isolated islands.[37]

Twenty-four of the atolls and islands are inhabited. The uninhabited atolls are:

- Ailinginae Atoll

- Bikar (Bikaar) Atoll

- Bikini Atoll

- Bokak Atoll

- Erikub Atoll

- Jemo Island

- Nadikdik Atoll

- Rongerik Atoll

- Toke Atoll

- Ujelang Atoll

The average altitude above sea level for the entire country is 7 feet (2.1 m).[37]

Shark sanctuary

In October 2011, the government declared that an area covering nearly 2,000,000 square kilometres (772,000 sq mi) of ocean shall be reserved as a shark sanctuary. This is the world's largest shark sanctuary, extending the worldwide ocean area in which sharks are protected from 2,700,000 to 4,600,000 square kilometres (1,042,000 to 1,776,000 sq mi). In protected waters, all shark fishing is banned and all by-catch must be released. However, some have questioned the ability of the Marshall Islands to enforce this zone.[38]

Territorial claim on Wake Island

The Marshall Islands also lays claim to Wake Island.[39] While Wake has been administered by the United States since 1899, the Marshallese government refers to it by the name Enen-kio.

Climate

The climate is hot and humid, with a wet season from May to November. Many Pacific typhoons begin as tropical storms in the Marshall Islands region, and grow stronger as they move west toward the Mariana Islands and the Philippines.

Due to its very low elevation, the Marshall Islands are threatened by the potential effects of sea level rise.[40][41] According to the president of Nauru, the Marshall Islands are the most endangered nation in the world due to flooding from climate change.[42]

Population has outstripped the supply of freshwater, usually from rainfall. The northern atolls get 50 inches (1,300 mm) of rainfall annually; the southern atolls about twice that. The threat of drought is commonplace throughout the island chains.[43]

Economy

The islands have few natural resources, and their imports far exceed exports.

Labour

In 2007, the Marshall Islands joined the International Labour Organization, which means its labour laws will comply with international benchmarks. This may impact business conditions in the islands.[44]

Taxation

The income tax has two brackets, with rates of 8% and 12%.[45] The corporate tax is 3% of revenue.[45]

Foreign assistance

United States government assistance is the mainstay of the economy. Under terms of the Amended Compact of Free Association, the U.S. is committed to provide US$57.7 million per year in assistance to the Marshall Islands (RMI) through 2013, and then US$62.7 million through 2023, at which time a trust fund, made up of U.S. and RMI contributions, will begin perpetual annual payouts.[46]

The United States Army maintains the Ronald Reagan Ballistic Missile Defense Test Site on Kwajalein Atoll. Marshallese land owners receive rent for the base.

Agriculture

Agricultural production is concentrated on small farms.[citation needed] The most important commercial crops are coconuts, tomatoes, melons, and breadfruit.[citation needed]

Industry

Small-scale industry is limited to handicrafts, fish processing, and copra.

Fishing

Fishing has been critical to the economy of this island nation since its settlement.

In 1999, a private company built a tuna loining plant with more than 400 employees, mostly women. But the plant closed in 2005 after a failed attempt to convert it to produce tuna steaks, a process that requires half as many employees. Operating costs exceeded revenue, and the plant's owners tried to partner with the government to prevent closure. But government officials personally interested in an economic stake in the plant refused to help. After the plant closed, it was taken over by the government, which had been the guarantor of a $2 million loan to the business.[citation needed]

Energy

On September 15, 2007, Witon Barry (of the Tobolar Copra processing plant in the Marshall Islands capital of Majuro) said power authorities, private companies, and entrepreneurs had been experimenting with coconut oil as alternative to diesel fuel for vehicles, power generators, and ships. Coconut trees abound in the Pacific's tropical islands. Copra, the meat of the coconut, yields coconut oil (1 liter for every 6 to 10 coconuts).[47] In 2009, a 57 kW solar power plant was installed, the largest in the Pacific at the time, including New Zealand.[48] It is estimated that 330 kW of solar and 450 kW of wind power would be required to make the College of the Marshall Islands energy self-sufficient.[49] Marshalls Energy Company (MEC), a government entity, provides the islands with electricity. In 2008, 420 solar home systems of 200 Wp each were installed on Ailinglaplap Atoll, sufficient for limited electricity use.[50]

Demographics

Historical population figures are unknown. In 1862, the population was estimated at about 10,000.[11] In 1960, the entire population was about 15,000. In July 2011, the number of island residents was estimated to number about 72,191.[2] Over two-thirds of the population live in the capital, Majuro and Ebeye, the secondary urban center, located in Kwajalein Atoll. This excludes many who have relocated elsewhere, primarily to the United States. The Compact of Free Association allows them to freely relocate to the United States and obtain work there.[51] A large concentration of about 4,300 Marshall Islanders have relocated to Springdale, Arkansas, the largest population concentration of natives outside their island home.[52]

Most of the residents are Marshallese, who are of Micronesian origin and migrated from Asia several thousand years ago. A minority of Marshallese have some recent Asian ancestry, mainly Japanese. About one-half of the nation's population lives on Majuro, the capital, and Ebeye, a densely populated island.[53][54][55][56] The outer islands are sparsely populated due to lack of employment opportunities and economic development. Life on the outer atolls is generally traditional.

The official language of the Marshall Islands is Marshallese, but it is common to speak the English language.[57]

Religion

Major religious groups in the Republic of the Marshall Islands include the United Church of Christ (formerly Congregational), with 51.5% of the population; the Assemblies of God, 24.2%; the Roman Catholic Church, 8.4%;[58] and The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Mormons), 8.3%.[58] Also represented are Bukot Nan Jesus (also known as Assembly of God Part Two), 2.2%; Baptist, 1.0%; Seventh-day Adventists, 0.9%; Full Gospel, 0.7%; and the Baha'i Faith, 0.6%.[58] Persons without any religious affiliation account for a very small percentage of the population.[58] There is also a small community of Ahmadiyya Muslims based in Majuro, with the first mosque opening in the capital in September 2012.[59]

Education

The Ministry of Education (Marshall Islands) operates the state schools in the Marshall Islands.[60] There are two tertiary institutions operating in the Marshall Islands, the College of the Marshall Islands[61] and the University of the South Pacific.

Transportation

The Marshall Islands are served by the Marshall Islands International Airport in Majuro, the Bucholz Army Airfield in Kwajalein, and other small airports and airstrips.[62]

In 2005, Aloha Airlines canceled its flight services to the Marshall Islands.

Media

The Marshall Islands have several AM and FM radio stations.

- AM: V7AB 1098 • 1557[citation needed]

- FM: V7AB 97.9 • V7AA 104.1 (formerly 96.3)[citation needed]

- AFRTS: AM 1224 (NPR) • 99.9 (Country) • 101.1 (Active Rock) • 102.1 (Hot AC)[citation needed]

Culture

Although the ancient skills are now in decline, the Marshallese were once able navigators, using the stars and stick-and-shell charts.

See also

- Outline of the Marshall Islands

- Index of Marshall Islands-related articles

- Visa policy of the Marshall Islands

- List of island countries

- The Plutonium Files

Notes

- ^ Pronunciations:

* English: Republic of the Marshall Islands /ˈmɑːrʃəl ˈaɪləndz/

* Marshallese: Aolepān Aorōkin M̧ajeļ ([Lua error in Module:IPAc2-mh at line 186: 'icon' contains unsupported characters: co.]) - ^ Wake Island is claimed as a territory of the Marshall Islands, but is also claimed as an unorganized, unincorporated territory of the United States, with de facto control vested in the Office of Insular Affairs.

References

- ^ The largest cities in Marshall Islands, ranked by population. population.mongabay.com. Retrieved on May 25, 2012.

- ^ a b c d "Marshall Islands Geography". CIA World Factbook.

- ^ a b c d "Republic of the Marshall Islands". Pacific RISA. Retrieved November 1, 2015.

- ^ The History of Mankind by Professor Friedrich Ratzel, Book II, Section A, The Races of Oceania page 165, picture of a stick chart from the Marshall Islands. MacMillan and Co., published 1896.

- ^ Sharp, pp. 11–3

- ^ Wright 1951: 109–10

- ^ Sharp, pp. 19–23

- ^ Filipiniana Book Guild 1965: 46–8, 91, 240

- ^ Sharp, pp. 36–9

- ^ a b Minahan, James (2010). The Complete Guide to National Symbols and Emblems. Santa Barbara, California: Greenwood Press. p. 106. ISBN 9780313344978. Retrieved November 1, 2015.

- ^ a b c d Beardslee, L. A. (1870). Marshall Group. North Pacific Islands. Washington DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 33. Retrieved November 1, 2015.

- ^ Hezel, Francis X. The First Taint of Civilization: A History of the Caroline and Marshall Islands in Pre-colonial Days, 1521–1885 University of Hawaii Press, 1994. pp. 304–06.

- ^ Dirk H. R. Spennemann, Marshall Islands History Sources No. 18: Treaty of friendship between the Marshallese chiefs and the German Empire (1885). marshall.csu.edu.au

- ^ Hezel, Francis X. (2003) Strangers in Their Own Land: A Century of Colonial Rule in the Caroline and Marshall Islands, University of Hawaii Press, pp. 45–46, ISBN 0824828046.

- ^ Spennemann, Dirk (1989). "Population control measures in traditional Marshallese Culture: a review of 19th century European observations". Digital Micronesia-An Electronic Library & Archive. Institute of Land, Water and Society, Charles Sturt University, Albury New South Wales, Australia. Retrieved November 1, 2015.

- ^ a b "Marshall Islands. Geographic Background" (PDF). enenkio.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 3, 2009.

- ^ Full text (German) , Artikel 119

- ^ a b c d "Marshall Islands". Pacific Institute of Advanced Studies in Development and Governance (PIAS-DG), University of the South Pacific, Suva, Fiji. Archived from the original on May 13, 2011. Retrieved June 11, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ according to the rules of the league (article 1, section 3), the egression became effective exactly two years later: pdf

- ^ "History". Marshall Islands Visitors Authority. Archived from the original on March 21, 2009. Retrieved June 11, 2010.

- ^ "Marshall Islands". World Statesmen. Retrieved June 11, 2010.

- ^ Dirk H.R. Spennemann. "Mili Island, Mili Atoll: a brief overview of its WWII sites". Retrieved June 11, 2010.

- ^ "Nuclear Weapons Test Map", Public Broadcasting Service

- ^ a b "Islanders Want The Truth About Bikini Nuclear Test". Japanfocus.org. Retrieved July 4, 2010.

- ^ "Intro".

- ^ Stephanie Cooke (2009). In Mortal Hands: A Cautionary History of the Nuclear Age, Black Inc., p. 168, ISBN 978-1-59691-617-3.

- ^ "50 Facts About Nuclear Weapons". Brookings Institution. July 19, 2011. Archived from the original on July 19, 2011.

- ^ "Marshall atolls declare emergency ", BBC News, December 25, 2008.

- ^ President Obama Signs a Disaster Declaration for the Republic of the Marshall Islands | The White House. Whitehouse.gov (June 14, 2013). Retrieved on September 11, 2013.

- ^ NEWS: Marshall Islands call for "New wave of climate leadership" at upcoming Pacific Islands Forum Climate & Development Knowledge Network. Downloaded July 31, 2013.

- ^ "Constitution of the Marshall Islands". Paclii.org. Archived from the original on January 2, 2011. Retrieved October 25, 2015.

- ^ Giff Johnson (November 25, 2010). "Huge funeral recognizes late Majuro chief". Marianas Variety News & Views. Archived from the original on July 14, 2011. Retrieved November 28, 2010.

- ^ United Nations General Assembly Resolution 46/3, Admission of the Republic of the Marshall Islands to Membership in the United Nations, adopted 17 September 1991.

- ^ General Assembly – Overall Votes – Comparison with U.S. vote lists the Marshall Islands as the country with the second highest incidence of votes. Micronesia has always been in the top two.

- ^ Armin Rosen (April 29, 2015). "Marshall Islands ship seized by Iran - Business Insider". Business Insider.

- ^ "Iran to release cargo vessel after it pays fine - Business Insider". Business Insider. May 6, 2015.

- ^ a b c "Geography".

- ^ "Vast shark sanctuary created in Pacific". BBC News. October 3, 2011. Retrieved November 25, 2011.

- ^ "Wake Island". The World Factbook (2024 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency.

- ^ Julia Pyper, ClimateWire. "Storm Surges, Rising Seas Could Doom Pacific Islands This Century". Scientific American.

- ^ "The Marshall Islands Are Disappearing". The New York Times. December 2, 2015.

- ^ Stephen, Marcus (November 14, 2011). "A sinking feeling: why is the president of the tiny Pacific island nation of Nauru so concerned about climate change?". New York Times Upfront. Retrieved February 9, 2015.

- ^ Peter Meligard (December 28, 2015). "Perishing oO Thirst In A Pacific Paradise". Huffington Post. Retrieved December 28, 2015.

- ^ "Republic of the Marshall Islands becomes 181st ILO member State". Ilo.org. July 6, 2007. Archived from the original on July 24, 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Official Homepage of the NITIJELA (PARLIAMENT)". NITIJELA (PARLIAMENT) of the Republic of the Marshall Islands. July 2, 2014.

- ^ "COMPACT OF FREE ASSOCIATION AMENDMENTS ACT OF 2003" (PDF). Public Law 108–188, 108th Congress. December 17, 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 26, 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Pacific Islands look to coconut power to fuel future growth". afp.google.com. September 13, 2007. Archived from the original on January 13, 2008. Retrieved October 25, 2015.

- ^ College of the Marshall Islands. (PDF) . reidtechnology.co.nz. June 2009

- ^ College of the Marshall Islands: Reiher Returns from Japan Solar Training Program with New Ideas. Yokwe.net. Retrieved on September 11, 2013.

- ^ "Republic of the Marshall Islands". Rep5.eu. Archived from the original on May 10, 2013. Retrieved October 25, 2015.

- ^ Gwynne, S.C. (October 5, 2012). "Paradise With an Asterisk". Outside Magazine. Retrieved August 9, 2013.

- ^ Schulte, Bret (July 4, 2012). "For Pacific Islanders, Hopes and Troubles in Arkansas". New York TImes.

- ^ David Vine (2006). "The Impoverishment of Displacement: Models for Documenting Human Rights Abuses and the People of Diego Garcia" (PDF). Human Rights Brief. 13 (2): 21–24.

- ^ David Vine (January 7, 2004) Exile in the Indian Ocean: Documenting the Injuries of Involuntary Displacement. Ralph Bunche Institute for International Studies. Web.gc.cuny.edu. Retrieved on September 11, 2013.

- ^ David Vine (2006). Empire's Footprint: Expulsion and the United States Military Base on Diego Garcia. ProQuest. p. 268. ISBN 978-0-542-85100-1.

- ^ David Vine (2011). Island of Shame: The Secret History of the U.S. Military Base on Diego Garcia (New in Paper). Princeton University Press. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-691-14983-7.

- ^ "Marshall Islands Travel". Wwp.greenwichmeantime.com. March 11, 2010. Retrieved July 4, 2010.

- ^ a b c d International Religious Freedom Report 2009: Marshall Islands. United States Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor (September 14, 2007). This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ First Mosque opens up in Marshall Islands by Radio New Zealand International, September 21, 2012

- ^ Education. Office of the President, Republic of the Marshall Islands. rmigovernment.org. Retrieved on May 25, 2012.

- ^ College of the Marshall Islands (CMI). Cmi.edu. Retrieved on September 11, 2013.

- ^ "Republic of the Marshall Islands - Amata Kabua International Airport". Republic of the Marshall Islands Ports Authority.

Bibliography

- Sharp, Andrew (1960). Early Spanish Discoveries in the Pacific.

Further reading

- Barker, H. M. (2004). Bravo for the Marshallese: Regaining Control in a Post-nuclear, Post-colonial World. Belmont, California: Thomson/Wadsworth.

- Rudiak-Gould, P. (2009). Surviving Paradise: One Year on a Disappearing Island. New York: Union Square Press.

- Niedenthal, J. (2001). For the Good of Mankind: A History of the People of Bikini and Their Islands. Majuro, Marshall Islands: Bravo Publishers.

- Carucci, L. M. (1997). Nuclear Nativity: Rituals of Renewal and Empowerment in the Marshall Islands. DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press.

- Hein, J. R., F. L. Wong, and D. L. Mosier (2007). Bathymetry of the Republic of the Marshall Islands and Vicinity [Miscellaneous Field Studies; Map-MF-2324]. Reston, VA: U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Geological Survey.

- Woodard, Colin (2000). Ocean's End: Travels Through Endangered Seas. New York: Basic Books. (Contains extended account of sea-level rise threat and the legacy of U.S. Atomic testing.)

External links

Government

- Embassy of the Republic of the Marshall Islands Washington, DC official government site

- Chief of State and Cabinet Members

General information

- "Marshall Islands". The World Factbook (2024 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency.

- Country Profile from New Internationalist

- Marshall Islands from UCB Libraries GovPubs

- Template:Dmoz

- Marshall Islands from the BBC News

Wikimedia Atlas of the Marshall Islands

Wikimedia Atlas of the Marshall Islands

News media

- Marshall Islands Journal Weekly independent national newspaper[citation needed]

Other

- Digital Micronesia – Marshalls by Dirk HR Spennemann, Associate Professor in Cultural Heritage Management

- Plants & Environments of the Marshall Islands Book turned website by Dr. Mark Merlin of the University of Hawaii

- Atomic Testing Information

- Pictures of victims of U.S. nuclear testing in the Marshall Islands on Nuclear Files.org

- "Kenner hearing: Marshall Islands-flagged rig in Gulf oil spill was reviewed in February"

- NOAA's National Weather Service – Marshall Islands

- Canoes of the Marshall Islands

- Alele Museum - Museum of the Marshall Islands

- WUTMI - Women United Together Marshall Islands

- Marshall Islands

- Countries in Oceania

- Archipelagoes of the Pacific Ocean

- English-speaking countries and territories

- Former German colonies

- Former Japanese colonies

- Associated states of the United States

- Island countries

- World War II sites

- Liberal democracies

- Micronesia

- Republics

- States and territories established in 1986

- Member states of the United Nations

- World Digital Library related

- Small Island Developing States