Midland American English

Midland American English is, historically, a regional dialect or super-dialect of American English,[2] and, phonologically, a related set of English varieties in transition, geographically lying between the traditional Northern and Southern United States.[3] Its exact regional boundaries and defining features are somewhat debated among linguists due to definitional difficulties and local pronunciations undergoing rapid changes since the mid-twentieth century. These general characteristics of the Midland accent are firmly established: fronting of the /oʊ/, /aʊ/, and /ʌ/ vowels occurs towards the center or even front of the mouth;[4] the cot–caught merger is neither fully completed nor fully absent; and short-a tensing evidently occurs strongest before nasal consonants.[5]

The currently-documented core of the Midland dialect region spans from central Ohio at its eastern extreme to southeastern Nebraska and Oklahoma City at its western extreme. Certain areas outside of this core also clearly demonstrate the Midland accent, including Charleston, South Carolina;[6] the Texan cities of Abilene, Austin, and Corpus Christi; and central and southern Florida.[7]

The North Midland accent arguably falls under the umbrella of General American, however, South Midland pronunciation demonstrates more of the character of a Southern accent, with a variably "glideless" /aɪ/ vowel (reminiscent of the Southern U.S. accent, but only appearing before sonorant consonants) and an extremely fronted /oʊ/ vowel.[8] Early twentieth-century boundaries established for the Midland dialect region are being reduced or revised, since several previous sub-regions of Midland speech have since developed their own distinct dialects. Pennsylvania, the original home state of the Midland dialect, is one such area, having now formed such unique dialects as Philadelphia and Pittsburgh English.[9]

History

The dialect region labeled "Midland" was first defined by Hans Kurath (A Word Geography of the Eastern United States, 1949) as being spoken in an area centered on central Pennsylvania and expanding westward to include most of Pennsylvania and some westernmost parts of the Appalachian Mountains. Kurath and McDavid (The Pronunciation of English in the Atlantic States, 1961) later divided this region into two discrete subdivisions: the "North Midland" beginning north of the Ohio River valley area and extending westward into central Indiana, central Illinois, Iowa, and northern Missouri, as well as parts of Nebraska and northern Kansas ; and the "South Midland", which extends south of the Ohio River and expands westward to include Kentucky, Southern Indiana, Southern Illinois, southern Missouri, Arkansas, southern Kansas, and Oklahoma, west of the Mississippi river.

Labov, Ash, and Boberg (The Atlas of North American English, 2006), based solely on phonology and phonetics (i.e. accent), defined the Midland area as a buffer zone between the Inland North and the South; this area essentially coincides with Kurath and McDavid's North Midland, the "South Midland" being now considered as largely part, or the northern fringe, of the South. Indeed, while the lexical and grammatical isoglosses follow the Appalachian Mountains, the accent boundary follows the Ohio River.

Original and former Midland

According to the 2006 Atlas of North American English (ANAE),

The Midland was first defined [by] Kurath (1949) as a narrow stretch of the Atlantic eastern seaboard, extending westward through Pennsylvania (except for the northern tier of counties) and expanding broadly southward to include the Appalachian region of West Virginia, eastern Kentucky, and eastern Tennessee. This definition of the Midland is based on a broad base of lexical evidence which in turn reflects the settlement history of the region[....] The Appalachian areas, assigned to the Midland by Kurath, [now] show a heavy concentration of the chain shifts that define the South. In this respect, the Appalachian region is more southern than the areas that Kurath defined as the South. Kurath's Midland areas [in some locations] are therefore incorporated into the South in the ANAE definition.[10]

The ANAE, therefore, considers much Appalachian English to now fall under Southern American rather than Midland American English. In fact, Southern Appalachia is the strongest area in the country to show the Southern Vowel Shift, which begins with the gliding /aɪ/ vowel losing its glide quality, making words like pie sound something like pa, and lice something like lass. This shift in Appalachian English further produces a pronunciation quality often called the Southern "drawl." Other previous areas of the Midland accent have also deviated in other directions:

the original Midland was related to Philadelphia and its surrounding region, along with Pittsburgh and Western Pennsylvania. [However, the ANAE] will discuss the rapid changes that have taken place in the vowel system of Philadelphia since the second half of the twentieth century. These involve changes in the split short-a system and a re-orientation of the front vowels away from the Southern Shift towards the Northern pattern that lowers the short front vowels. The Pittsburgh dialect appears to have developed its characteristic glide deletion of /aw/ recently (Johnstone et al. 2002), leading to directions of change quite different from those of the surrounding region.[11]

In other words, the Midland dialect region originated in the state of Pennsylvania; however, many Midland varieties of English in Pennsylvania have since evolved in the last several decades, developing their own accents that are now notably distinct from the rest of the Midland, namely: Mid-Atlantic American English (including Philadelphia English) as well as Western Pennsylvania English, centered on Pittsburgh. For example, while most of the Midland consistently shows a transitional state of the cot–caught merger, the modern Philadelphia accent strongly resists the merger; contrarily, the Western Pennsylvania accent has now completed the merger. Additionally, the city of Philadelphia has its own unique short-a split, in which words like madder and matter, or plan it and planet, are not homophones, as they typically are in the rest of the Midland (and in fact the whole United States). In Pittsburgh, the gliding vowel /aʊ/ loses its glide in a variety of common words, for instance, making downtown sound something like dahntahn.

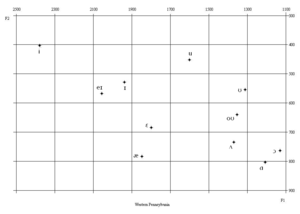

Western Pennsylvania

The dialect of western and much of central Pennsylvania is, for many purposes, an eastern extension of the South Midland;[13] it is spoken also in Youngstown, Ohio, ten miles west of the state line, as well as Clarksburg, West Virginia. Like the Midland proper, the Western Pennsylvania accent features fronting of /oʊ/ and /aʊ/, as well as positive anymore. The chief distinguishing feature of Western Pennsylvania as a whole is that the cot–caught merger is largely complete here (it is most fully complete in Pittsburgh), whereas it is still in progress in most of the Midland. The merger has also spread from Western Pennsylvania into adjacent West Virginia, historically in the South Midland dialect region.

The city of Pittsburgh is considered to have an accent or even dialect of its own, often lightheartedly known as "Pittsburghese". This region is additionally characterized by a sound change that is unique in North America: the monophthongization of /aʊ/ to [aː]. This is the source of the stereotypical Pittsburgh pronunciation of downtown as "dahntahn". Pittsburgh also features an unusually low allophone of /ʌ/ (as in cut); it approaches [ɑ] (/ɑ/ itself having moved out of the way and become a rounded vowel in its merger with /ɔ/).

Erie, Pennsylvania was described as being in the Northern dialect region in the first half of the 20th century. However, unlike other cities in the North, Erie underwent the caught–cot merger and not the Northern Cities Vowel Shift, and now Erie has at least as much in common linguistically with the rest of Western Pennsylvania as with the North. For this reason, Erie has been described as the only major city to change its affiliation from the North to the Midland.

Overview

Phonology

- Midland speech is firmly rhotic (or fully r-pronouncing), like most of North America.

- The cot–caught merger is consistently in a transitional phase throughout most of the Midland region, showing neither a full presence nor absence of the merger. This involves a vowel merger of the "short o" /ɑ/ (as in cot or stock) and 'aw' /ɔ/ (as in caught or stalk) phonemes.

- A well-known phonological difference between the Midland and the North is that the word on contains the phoneme /ɔ/ (as in caught) rather than /ɑ/ (as in cot). For this reason, one of the names for the boundary between the dialects of the Midland and the North is the "on line".

Phonetics

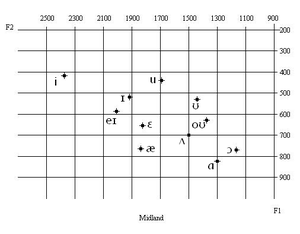

The North Midland and South Midland are both characterized by:[14]

- advanced fronting of /oʊ/: the phoneme /oʊ/ (as in boat) is fronter than in many other American accents, particularly those of the North; the phoneme is frequently realized as a diphthong with a central nucleus, approximating [ɵʊ].

- advanced fronting of /aʊ/: the diphthong /aʊ/ (as in mouth) has a fronter nucleus than /aɪ/, approaching [æʊ].

Grammar

- A common feature of the greater Midland area is so-called "positive anymore": It is possible to use the adverb anymore with the meaning "nowadays" in sentences without negative polarity, such as Air travel is inconvenient anymore.

- Many speakers use the construction need + past participle, as in the car needs washed, where speakers of other dialects would say needs to be washed or needs washing.

North Midland

The North Midland region stretches from east to west across central and southern Ohio, central Indiana, central Illinois, Iowa, and northern Missouri, as well as Nebraska and northern Kansas where it begins to blend into the West. Major cities of this dialect area include Kansas City, Omaha, St. Louis, Columbus, Ohio, Cincinnati, and Indianapolis.

In addition to the fronting of the diphthongs /oʊ/ and /aʊ/, the North Midland exhibits the following distinctive features:[15]

- advanced fronting of /ʌ/: among younger speakers, the "wedge" /ʌ/ (as in strut) is shifting strongly to the front.

- /oʊ/ less fronted than elsewhere in Midland

- the word "blinds": window shades or window shutters. While blinds usually refers to window shades, in Appalachia and the greater Midland dialect, it can also refer to window shutters.

The /æ/ phoneme (as in cat) shows most commonly a so-called "continuous" distribution: /æ/ is raised and tensed toward [eə] before nasal consonants and remains low [æ] before voiceless stop consonants, and other allophones of /æ/ occupy a continuum of varying degrees of height between those two extremes.

An increasing number of speakers from central Ohio realize the TRAP vowel /æ/ as open front [a].[16]

South Midland

The South Midland dialect region follows the Ohio River in a generally southwesterly direction, moving across from Kentucky, Southern Indiana, and Southern Illinois to southern Missouri, Arkansas, southern Kansas, and Oklahoma, west of the Mississippi river. Although historically more closely related to the North Midland speech, this region shows dialectal features that are now more similar to the rest of the South than the Midland, most noticeably the second person plural pronoun "you-all" or "y'all."

The South Midland accent can also show a "glideless" /aɪ/ vowel, reminiscent of the Southern accent of the United States; however, ANAE shows that this /aɪ/ deletion appears in the Midland only before sonorant consonants: /m/, /n/, /l/, /r/. For example, fire may be pronounced something like fahr or even far.

Unlike the coastal South, the South Midland has always been a rhotic dialect, pronouncing /r/ wherever it has historically occurred. Southern Indiana is the northernmost extent of the South Midland region, forming what dialectologists refer to as the "Hoosier Apex" of the South Midland; the accent is locally known there as the "Hoosier Twang" where Interstate 64 is usually referred to as Sixty-For or U.S. 41 is casually referred to as Forty-One. The South Midland dialect has also been called "Hill Southern", "Inland Southern", "Mountain Southern".[17] The Appalachian dialect is sometimes included.

The phonology of the South Midland is discussed in greater detail in Southern American English.

Texas

Rather than a proper Southern accent, many cities in Texas can be better described as having a South Midland accent, as they lack of the "true" Southern accent's /aɪ/ deletion and the oft-accompanying Southern Vowel Shift. Texan cities classifiable as such specifically include Abilene, Austin, Corpus Christi, and El Paso. Austin, in particular, has been reported in some speakers to show the South Midland (but not the Southern) variant of /aɪ/ deletion mentioned above.[18]

Charleston

Today, the city of Charleston, South Carolina clearly has all the defining features of a mainstream Midland accent. The vowels /oʊ/ and /uː/ are extremely fronted, and yet not so not before /l/.[19] Also, the older, more traditional Charleston accent was extremely "non-Southern" in sound (as well as being highly unique), spoken throughout the South Carolina and Georgia Lowcountry, but it mostly faded out of existence in the first half of twentieth century.[20]

Cincinnati

Cincinnati, Ohio has a phonological pattern quite distinct from the surrounding area (Boberg and Strassel 2000).

The traditional Cincinnati short-a system is unique in the Midland. While there is no evidence for a phonemic split, the phonetic conditioning of short-a in conservative Cincinnati speech is similar to and originates from that of New York City, with the raising environments including nasals (m, n, ŋ), voiceless fricatives (f, soft th, sh, s), and voiced stops (b, d, g). Weaker forms of this pattern are shown by speakers from nearby Dayton and Springfield. Boberg and Strassel (2000) reported that Cincinnati's traditional short-a system was giving way among younger speakers to a nasal system similar to those found elsewhere in the Midland and the West.

St. Louis Corridor

St. Louis, Missouri is historically one among several (North) Midland cities, but it has developed some unique features of its own distinguishing it from the rest of the Midland. The area around St. Louis has been in dialectal transition throughout most of the 1900s until the present moment. The eldest generation of the area may exhibit a rapidly-declining merger of the phonemes /ɔr/ (as in for) and /ɑr/ (as in far), while leaving distinct /or/ (as in four), thus being one of the few American accents to still resist the horse-hoarse merger while also displaying the card-cord merger. This merger has led to jokes referring to "I farty-far".[21] Also, some St. Louis speakers, again usually the oldest ones, have /eɪ/ instead of more typical /ɛ/ before /ʒ/—thus measure is pronounced /ˈmeɪʒ.ɚ/—and wash (as well as Washington) gains an /r/, becoming [wɔɻʃ] ("warsh").

Since the mid-1900s (namely, in speakers born from the 1920s to 1940s), however, a newer accent arose in a dialect "corridor" essentially following historic U.S. Route 66 in Illinois (now Interstate 55 in Illinois) from Chicago southwest to St. Louis. Speakers of this modern "St. Louis Corridor"—including St. Louis and Springfield, Illinois—have gradually developed more features of the Inland North dialect, best recognized today as the Chicago accent. This twentieth-century St. Louis accent's separating quality from the rest of the Midland is its strong resistance to the cot–caught merger and the most advanced development of the Northern Cities Vowel Shift (NCS).[22] In the twentieth century, Greater St. Louis therefore became a mix of Midland accents and Inland Northern (Chicago-like) accents.

Even more complicated, however, there is evidence that these Northern sound changes are reversing for the younger generations of speakers in the St. Louis area, who are re-embracing purely Midland-like accent features, though only at a regional level and therefore not including the aforementioned traditional features of the eldest generation. According to a UPenn study, the St. Louis Corridor's one-generation period of embracing the NCS was followed by the next generation's "retreat of NCS features from Route 66 and a slight increase of NCS off of Route 66", in turn followed by the most recent generations' decreasing evidence of the NCS until it disappears altogether among the youngest speakers.[23] Thus, due to harboring two different dialects in the same geographic space, the "Corridor appears simultaneously as a single dialect area and two separate dialect areas".[24]

See also

References

- ^ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:277)

- ^ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:5, 263)

- ^ Labov, William; Ash, Sharon; Boberg, Charles (1997). "Dialects of the United States." A National Map of The Regional Dialects of American English. University of Pennsylvania.

- ^ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:137, 263, 266)

- ^ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:182)

- ^ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:259)

- ^ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:107, 139)

- ^ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:105, 135)

- ^ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:135)

- ^ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:182)

- ^ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:135)

- ^ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:263)

- ^ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:268)

- ^ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:255–258 and 262–265)

- ^ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:262–268)

- ^ Thomas (2004:308)

- ^ "SOUTHERN ENGLISH, also Southern American English and Southern". Encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2015-06-01.

- ^ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:126)

- ^ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:259)

- ^ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:259)

- ^ Wolfram & Ward (2006:128)

- ^ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:61)

- ^ Friedman, Lauren (2015). A Convergence of Dialects in the St. Louis Corridor. Volume 21. Issue 2. Selected Papers from New Ways of Analyzing Variation(NWAV). 43. Article 8. University of Pennsylvania.

- ^ "Northern Cities Panel". 43rd NWAV. School of Literature's, Cultures, and Linguistics. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Bibliography

- Labov, William; Ash, Sharon; Boberg, Charles (2006). The Atlas of North American English. Berlin: Mouton-de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-016746-8.

- Thomas, Erik R. (2004), "Rural Southern White Accents", in Schneider, Edgar W.; Burridge, Kate; Kortmann, Bernd; Mesthrie, Rajend; Upton, Clive (eds.), A Handbook of Varieties of English, vol. 1: Phonology, Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 300–324, ISBN 3-11-017532-0