Moldova: Difference between revisions

Undid revision 548478120 by 89.206.227.99 (talk) rvv |

|||

| Line 133: | Line 133: | ||

In August 1939, the [[Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact]] and its secret additional protocol were signed, by which [[Nazi Germany]] recognized Bessarabia as being within the [[Soviet sphere of influence]], which led the latter to actively revive its claim to the region.<ref name="Olson 1994 483">{{cite book|last=Olson|first=James|title=An Ethnohistorical Dictionary of the Russian and Soviet Empires|year=1994|page=483}}</ref> On June 28, 1940, the Soviet Union, with the acknowledgement of Nazi Germany, issued an ultimatum to Romania requesting the cession of Bessarabia and northern Bukovina, [[Soviet occupation of Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina|with which Romania complied the following day]]. Soon after, the [[Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic]] (Moldavian SSR) was established,<ref name="Olson 1994 483"/> comprising about 70% of Bessarabia, and 50% of the now-disbanded Moldavian ASSR. |

In August 1939, the [[Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact]] and its secret additional protocol were signed, by which [[Nazi Germany]] recognized Bessarabia as being within the [[Soviet sphere of influence]], which led the latter to actively revive its claim to the region.<ref name="Olson 1994 483">{{cite book|last=Olson|first=James|title=An Ethnohistorical Dictionary of the Russian and Soviet Empires|year=1994|page=483}}</ref> On June 28, 1940, the Soviet Union, with the acknowledgement of Nazi Germany, issued an ultimatum to Romania requesting the cession of Bessarabia and northern Bukovina, [[Soviet occupation of Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina|with which Romania complied the following day]]. Soon after, the [[Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic]] (Moldavian SSR) was established,<ref name="Olson 1994 483"/> comprising about 70% of Bessarabia, and 50% of the now-disbanded Moldavian ASSR. |

||

As part of the 1941 [[Operation Barbarossa|Axis invasion of the Soviet Union]], Romania seized the territories of Bessarabia, northern Bukovina, and [[Transnistria (World War II)|Transnistria]]. Romanian forces, working with the Germans, deported or exterminated about 300,000 Jews, including 147,000 from Bessarabia and Bukovina (of the latter, approximately 90,000 perished).<ref>[http://www.presidency.ro/static/ordine/RAPORT_FINAL_CPADCR.pdf Tismăneanu Report], page 748-749</ref> The Soviet Army re-captured the region in February–August 1944, and re-established the Moldavian SSR. Between the end of the [[Jassy–Kishinev Offensive (August 1944)|Jassy-Kishinev Offensive]] in August 1944 and the end of the war in May 1945, 256,800 inhabitants of the Moldavian SSR were drafted into the Soviet Army. 40,592 of them perished.<ref name="history"> |

|||

{{cite book|title=Istoria Republicii Moldova: din cele mai vechi timpuri pină în zilele noastre|trans_title=History of the Republic of Moldova: From Ancient Times to Our Days|editor=Asociaţia Oamenilor de știinţă din Moldova. H. Milescu-Spătaru.|edition=2nd|year=2002|publisher=Elan Poligraf|location=Chișinău|language=ro|isbn=9975-9719-5-4|pages=239–244}}</ref> |

|||

====Soviet era==== |

====Soviet era==== |

||

Revision as of 16:05, 3 April 2013

Republic of Moldova Republica Moldova | |

|---|---|

| Anthem: Limba Noastră Our Language | |

Location of Moldova (green) and Transnistria (light green) on the European continent. | |

| Capital and largest city | |

| Official languages | Moldovan (Romanian)a |

| Recognised regional languages | |

| Ethnic groups (2004) |

|

| Demonym(s) | Moldovan Moldavian |

| Government | Parliamentary republic |

| Nicolae Timofti | |

• Acting Prime Minister | Vlad Filat |

| Marian Lupu | |

| Legislature | Parliament |

| Independence | |

| 23 June 1990 | |

| 27 August 1991c | |

• Constitution adopted | 29 July 1994 |

| Area | |

• Total | 33,846 km2 (13,068 sq mi) (138th) |

• Water (%) | 1.4 |

| Population | |

• 2012 estimate | 3,559,500[1] (132nd) |

• 2004 census | 3,383,332[2] (excluding Transnistria) 3,938,679[3] (including Transnistria) |

• Density | 121.9/km2 (315.7/sq mi) (93rd) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2012 estimate |

• Total | $12.558 billion[4] |

• Per capita | $3,534[4] |

| GDP (nominal) | 2012 estimate |

• Total | $7.589 billion[4] |

• Per capita | $2,136[4] |

| Gini (2011) | 38.0 medium inequality |

| HDI (2013) | medium (113th) |

| Currency | Moldovan leu (MDL) |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

• Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| Drives on | right |

| Calling code | +373 |

| ISO 3166 code | MD |

| Internet TLD | .md |

| |

Moldova /mɔːlˈdoʊvə/ ,[6][7] officially the Republic of Moldova (Moldovan/Template:Lang-ro pronounced [reˈpublika molˈdova]) is a landlocked[8] nation in Eastern Europe located between Romania to the west and Ukraine to the north, east, and south. The capital city is Chișinău. It declared itself an independent state with the same boundaries as the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic in 1991 as part of the dissolution of the Soviet Union. On July 29, 1994, the new constitution of Moldova was adopted. A strip of Moldova's internationally recognized territory on the east bank of the river Dniester has been under the de facto control of the breakaway government of Transnistria since 1990.

The nation is a parliamentary republic with a president as head of state and a prime minister as head of government. Moldova is a member state of the United Nations, Council of Europe, WTO, OSCE, GUAM, CIS, BSEC and other international organizations. Moldova currently aspires to join the European Union,[9] and has implemented the first three-year Action Plan within the framework of the European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP).[10]

Etymology

The name "Moldova" is derived from the Moldova River; the valley of this river was a political center when the Principality of Moldavia was founded in 1359.[11] The origin of the name of the river is not clear. There is an account (a legend) of prince Dragoș naming the river after hunting an aurochs: after the chase, his exhausted hound Molda drowned in the river. According to Dimitrie Cantemir and Grigore Ureche, the dog's name was given to the river and extended to the Principality.[12]

History

Prehistory

During the Neolithic stone age era, Moldova's territory was the center of the large Cucuteni-Trypillian culture that stretched east beyond the Dniester River in Ukraine, and west up to and beyond the Carpathian Mountains in Romania. The inhabitants of this civilization, which lasted roughly from 5500 to 2750 BC, practiced agriculture, raised livestock, hunted, and made intricately designed pottery.[13]

Antiquity and Middle Ages

In antiquity, Moldova's territory was inhabited by Dacian tribes. Between the 1st and 7th centuries AD, the south was intermittently under the Roman, then Byzantine Empires. Due to its strategic location on a route between Asia and Europe, the territory of modern Moldova was invaded many times in late antiquity and early Middle Ages, including by Goths, Huns, Avars, Bulgarians, Magyars, Pechenegs, Cumans, Mongols and Tatars.

The Principality of Moldavia, established in 1359, was bounded by the Carpathian mountains in the west, Dniester river in the east, and Danube and Black Sea in the south. Its territory comprised the present-day territory of the Republic of Moldova, the eastern eight of the 41 counties of Romania, and the Chernivtsi oblast and Budjak region of Ukraine. Like the present-day republic and Romania's north-eastern region, it was known to the locals as Moldova. Moldavia was invaded repeatedly by Crimean Tatars and, since the 15th century, by the Turks. In 1538, the principality became a tributary to the Ottoman Empire, but it retained internal and partial external autonomy.[14]

Modern history

Russian Empire

In accordance with the Treaty of Bucharest of 1812 and despite numerous protests by Moldavian nobles on behalf of their autonomous status, the Ottoman Empire (of which Moldavia was a vassal) ceded to the Russian Empire the eastern half of the territory of the Principality of Moldavia along with Khotyn and old Bessarabia (modern Budjak).

The new Russian province was called "Oblast of Moldavia and Bessarabia", and initially enjoyed a large degree of autonomy. After 1828 this autonomy was progressively restricted and in 1871 the Oblast was transformed into the Bessarabia Governorate, in a process of state-imposed assimilation, "Russification". As part of this process, the Tsarist administration in Bessarabia gradually removed the Romanian language from official and religious use.[15] The western part of Moldavia (which is a part of present-day Romania) remained an autonomous principality, and in 1859, united with Wallachia to form the Kingdom of Romania.

The Treaty of Paris (1856) returned three counties of Bessarabia — Cahul, Bolgrad and Ismail — to Moldavia, but in the Treaty of Berlin (1878), the Kingdom of Romania agreed to return them to the Russian Empire. Over the 19th century, the Russian authorities encouraged colonization of the south of the region by Romanians,[16] Ukrainians, Lipovans, Cossacks, Bulgarians,[17] Germans,[18] Gagauzes, and allowed the settlement of more Jews,[19] to replace the large Nogai Tatar population expelled in the 1770s and 1780s, during Russo-Turkish Wars;[20] the Moldovan proportion of the population decreased from around 86% in 1816[21], in the aftermath of the Muslim expulsion, to around 52% in 1905.[22] During this time there were anti-Semitic riots, leading to an exodus of thousands of Jews to the United States of America.[23]

Greater Romania

World War I brought in a rise in political and cultural (ethnic) awareness among the inhabitants of the region, as 300,000 Bessarabians were drafted into the Russian Army formed in 1917; within bigger units several "Moldavian Soldiers' Committees" were formed. Following the Russian Revolution of 1917, a Bessarabian parliament, Sfatul Ţării, was elected in October–November 1917 and opened on December 3 [O.S. November 21] 1917. The Sfatul Ţării proclaimed the Moldavian Democratic Republic (December 15 [O.S. December 2] 1917) within a federal Russian state, and formed a government (December 21 [O.S. December 8] 1917).

Bessarabia proclaimed independence from Russia on February 6 [O.S. January 24] 1918 and requested the assistance of the French army present in Romania (general Henri Berthelot) and of the Romanian army, which had occupied the region in early January.[24] On April 9 [O.S. March 27] 1918, the Sfatul Ţării decided with 86 votes for, 3 against and 36 abstaining, to unite with the Kingdom of Romania. The union was conditional upon fulfillment of the agrarian reform, autonomy, and respect for universal human rights.[25] A part of the interim Parliament agreed to drop these conditions after Bukovina and Transylvania also joined the Kingdom of Romania, although historians note that they lacked the quorum to do so.[26][27][28][29][30]

This union was recognized by the principal Allied Powers in the 1920 Treaty of Paris, which however was not ratified by all of its signatories.[31][32] Some major powers, such as the United States and the newly communist Russia, did not recognize Romanian rule over Bessarabia, the latter considering it an occupation of Russian territory.[33]

In May 1919, the Bessarabian Soviet Socialist Republic was proclaimed as a government in exile. After the failure of the Tatarbunary Uprising in 1924, the Moldavian Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (Moldavian ASSR) was formed.

In August 1939, the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact and its secret additional protocol were signed, by which Nazi Germany recognized Bessarabia as being within the Soviet sphere of influence, which led the latter to actively revive its claim to the region.[34] On June 28, 1940, the Soviet Union, with the acknowledgement of Nazi Germany, issued an ultimatum to Romania requesting the cession of Bessarabia and northern Bukovina, with which Romania complied the following day. Soon after, the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic (Moldavian SSR) was established,[34] comprising about 70% of Bessarabia, and 50% of the now-disbanded Moldavian ASSR.

Soviet era

During the Stalinist periods 1940–1941 and 1944–1953, deportations of locals to the northern Urals, to Siberia, and northern Kazakhstan occurred regularly, with the largest ones on 12–13 June 1941, and 5–6 July 1949, accounting from MSSR alone for 18,392[35] and 35,796 deportees respectively.[36] Other forms of Soviet persecution of the population included 32,433 political arrests, followed by Gulag or (in 8,360 cases) execution.

In 1946, as a result of a severe drought and excessive delivery quota obligations and requisitions imposed by the Soviet government, the southwestern part of the USSR suffered from a major famine.[37] In 1946–1947, at least 216,000 deaths and about 350,000 cases of dystrophy were accounted by historians in the Moldavian SSR alone.[36] Similar events occurred in 1930s in the Moldavian ASSR.[36] In 1944–53, there were several anti-Soviet resistance groups in Moldova; however the NKVD and later MGB managed to eventually arrest, execute or deport their members.[36]

In the postwar period, the Soviet government arranged migration of workforce (mostly Russians, Belarusians, and Ukrainians), into the new Soviet republic, especially into urbanized areas, partly to compensate for the demographic loss caused by the war and the emigration of 1940 and 1944.[38] In the 1970s and 1980s, the Moldavian SSR received substantial allocations from the budget of the USSR to develop industrial and scientific facilities and housing. In 1971, the Council of Ministers of the USSR adopted a decision "About the measures for further development of the city of Kishinev" (modern Chișinău), that allotted more than one billion Soviet rubles from the USSR budget for building projects,[39] subsequent decisions also directed substantial funding and brought qualified specialists from other parts of the USSR to develop Moldova's industry.[citation needed]

The Soviet government conducted a campaign to promote a Moldovan ethnic identity distinct from that of the Romanians, based on a theory developed during the existence of the Moldavian ASSR. Official Soviet policy asserted that the language spoken by Moldovans was distinct from the Romanian language (see Moldovenism). To distinguish the two, during the Soviet period, Moldovan was written in the Cyrillic alphabet, in contrast [citation needed] with Romanian, which since 1860 had been written in the Latin alphabet.

After the death of Stalin, political persecutions changed in character from mass to individual. All independent organizations were severely reprimanded, with the National Patriotic Front leaders being sentenced in 1972 to long prison terms. The Commission for the Study of the Communist Dictatorship in Moldova is assessing the activity of the communist totalitarian regime.

In the 1980s, political conditions created by the glasnost and perestroika, a Democratic Movement of Moldova was formed, which in 1989 became known as the nationalist Popular Front of Moldova (FPM).[40][41] Along with several other Soviet republics, from 1988 onwards, Moldova started to move towards independence. On August 27, 1989, the FPM organized a mass demonstration in Chișinău that became known as the Grand National Assembly. The assembly pressured the authorities of the Moldavian SSR to adopt a language law on August 31, 1989 that proclaimed the Moldovan language written in the Latin script to be the state language of the MSSR. Its identity with the Romanian language was also established.[40][42] The year 1989 that had seen Communist Party increasingly pummeled, was also marked by November riots.[43][44]

Independence

The first democratic elections for the local parliament were held in February and March 1990. Mircea Snegur was elected as Speaker of the Parliament, and Mircea Druc as Prime Minister. On June 23, 1990, the Parliament adopted the Declaration of Sovereignty of the "Soviet Socialist Republic Moldova", which, among other things, stipulated the supremacy of Moldovan laws over those of the Soviet Union.[40] After the failure of the 1991 Soviet coup d'état attempt, on August 27, 1991, Moldova declared its independence, Romania being the first state to recognize its independence.

On December 21 of the same year, Moldova, along with most of the other Soviet republics, signed the constitutive act that formed the post-Soviet Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS). Moldova received official recognition on December 25. On December 26, 1991 the Soviet Union ceased to exist. Declaring itself a neutral state, it did not join the military branch of the CIS. Three months later, on March 2, 1992, the country gained formal recognition as an independent state at the United Nations. In 1994, Moldova became a member of NATO's Partnership for Peace program and also a member of the Council of Europe on June 29, 1995.[40]

In the region east of the Dniester river, Transnistria, which includes a large proportion of predominantly russophone East Slavs of Ukrainian (28%) and Russian (26%) descent (altogether 54% as of 1989), while Moldovans (40%) have been the largest ethnic group, and where the headquarters and many units of the Soviet 14th Guards Army were stationed, an independent Pridnestrovian Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic was proclaimed on August 16, 1990, with its capital in Tiraspol.[40] The motives behind this move were fear of the rise of nationalism in Moldova and the country's expected reunification with Romania upon secession from the USSR. In the winter of 1991–1992 clashes occurred between Transnistrian forces, supported by elements of the 14th Army, and the Moldovan police. Between March 2 and July 26, 1992, the conflict escalated into a military engagement.

On January 2, 1992, Moldova introduced a market economy, liberalizing prices, which resulted in rapid inflation. From 1992 to 2001, the young country suffered a serious economic crisis, leaving most of the population below the poverty line. In 1993, a national currency, the Moldovan leu, was introduced to replace the temporary cupon. The economy of Moldova began to change in 2001; and until 2008 the country saw a steady annual growth of between 5% and 10%. The early 2000s also saw a considerable growth of emigration of Moldovans looking for work (mostly illegally) in Russia (especially the Moscow region), Italy, Portugal, Spain, Greece, Cyprus, Turkey, and other countries; remittances from Moldovans abroad account for almost 38% of Moldova's GDP, the second-highest percentage in the world.[45]

In the 1994 parliamentary elections, the Democratic Agrarian Party gained a majority of the seats, setting a turning point in Moldovan politics. With the nationalist Popular Front now in a parliamentary minority, new measures aiming to moderate the ethnic tensions in the country could be adopted. Plans for a union with Romania were abandoned,[40] and the new Constitution gave autonomy to the breakaway Transnistria and Gagauzia. On December 23, 1994, the Parliament of Moldova adopted a "Law on the Special Legal Status of Gagauzia", and in 1995 the latter was constituted.

After winning the 1996 presidential elections, on January 15, 1997, Petru Lucinschi, the former First Secretary of the Moldavian Communist Party in 1989–91, became the country's second president (1997–2001), succeeding Mircea Snegur (1991–1996). In 2000, the Constitution was amended, transforming Moldova into a parliamentary republic, with the president being chosen through indirect election rather than direct popular vote.

Winning 49.9% of the vote, the Party of Communists of the Republic of Moldova (reinstituted in 1993 after being outlawed in 1991), gained 71 of the 101 MPs, and on April 4, 2001, elected Vladimir Voronin as the country's third president (re-elected in 2005). The country became the first post-Soviet state where a non-reformed Communist Party returned to power.[40] New governments were formed by Vasile Tarlev (April 19, 2001 – March 31, 2008), and Zinaida Greceanîi (March 31, 2008 – September 14, 2009). In 2001–2003 relations between Moldova and Russia improved, but then temporarily deteriorated in 2003–2006, in the wake of the failure of the Kozak memorandum, culminating in the 2006 wine exports crisis. The Party of Communists of the Republic of Moldova managed to stay in power for eight years. The fragmentation of the liberal (aka the democrats) helped consolidate its power. The decline of the party started in 2009 after Marian Lupu joined the Democratic Party and thus attracted many of the Moldovans supporting the Communists.[46]

In the April 2009 parliamentary elections, the Communist Party won 49.48% of the votes, followed by the Liberal Party with 13.14% of the votes, the Liberal Democratic Party with 12.43%, and the Alliance "Moldova Noastră" with 9.77%. The controversial results of this election sparked civil unrest[47][48][49]

In August 2009, four Moldovan parties – Liberal Democratic Party, Liberal Party, Democratic Party, and Our Moldova Alliance – agreed to create a governing coalition that pushed the Communist party into opposition. On August 28, 2009, this coalition chose a new parliament speaker (Mihai Ghimpu) in a vote that was boycotted by Communist legislators. Vladimir Voronin, who had been President of Moldova since 2001, eventually resigned on September 11, 2009, but the Parliament failed to elect a new president. The acting president Mihai Ghimpu instituted the Commission for constitutional reform in Moldova to adopt a new version of the Constitution of Moldova. After the constitutional referendum aimed to approve the reform failed in September 2010,[50] the parliament was dissolved again and a new parliamentary election was scheduled for 28 November 2010.[51] On December 30, 2010, Marian Lupu was elected as the Speaker of the Parliament.[52] In accordance with the Constitution, he will be serving as the Acting President of Republic of Moldova.

Government and politics

Moldova is a unitary parliamentary representative democratic republic. The 1994 Constitution of Moldova sets the framework for the government of the country. A parliamentary majority of at least two thirds is required to amend the Constitution of Moldova, which cannot be revised in time of war or national emergency. Amendments to the Constitution affecting the state's sovereignty, independence, or unity can only be made after a majority of voters support the proposal in a referendum. Furthermore, no revision can be made to limit the fundamental rights of people enumerated in the Constitution.[53]

The country's central legislative body is the unicameral Moldovan Parliament (Parlament), which has 101 seats, and whose members are elected by popular vote on party lists every four years.

The head of state is the President of Moldova, who is elected by the Moldovan Parliament, requiring the support of three fifths of the deputies (at least 61 votes). The president of Moldova has been elected by the parliament since 2001, a change designed to decrease executive authority in favor of the legislature. The president appoints a prime minister who functions as the head of government, and who in turn assembles a cabinet, both subject to parliamentary approval.

The 1994 constitution also establishes an independent Constitutional Court, composed of six judges (two appointed by the President, two by Parliament, and two by the Supreme Council of Magistrature), serving six-year terms, during which they are irremovable and not subordinate to any power. The Court is invested with the power of judicial review over all acts of the parliament, over presidential decrees, and over international treaties, signed by the country.[53]

Foreign relations

After achieving independence from the Soviet Union, Moldova established relations with other European countries. A course for European Union integration and neutrality define the country's foreign policy guidelines. In 1995 the country was admitted to the Council of Europe. In addition to its participation in NATO's Partnership for Peace program, Moldova is also a member state of the United Nations, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), the North Atlantic Cooperation Council, the World Trade Organization, the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, the Francophonie and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development.

In 2005, Moldova and the EU established an action plan that sought to improve the collaboration between the two neighboring structures. At the end of 2005 EUBAM, the European Union Border Assistance Mission to Moldova and Ukraine, was established at the joint request of the presidents of Moldova and Ukraine. EUBAM assists the Moldovan and Ukrainian governments in approximating their border and customs procedures to EU standards, and offers support in both countries' fight against cross-border crime.

After the 1990–1992 War of Transnistria, Moldova sought a peaceful resolution to the conflict in the Transnistria region by working with Romania, Ukraine, and Russia, calling for international mediation, and co-operating with the OSCE and UN fact-finding and observer missions. The foreign minister of Moldova, Andrei Stratan, repeatedly stated that the Russian troops stationed in the breakaway region were there against the will of the Moldovan government and called on them to leave "completely and unconditionally."[54] In 2012, the death of Vadim Pisari raised tensions with Russia and revived a decades-old debate over security in Moldova.[55]

In September 2010, the European Parliament approved a grant of €90 million to Moldova.[56] The money will supplement $570 million in International Monetary Fund loans,[57] World Bank and other bilateral support already granted to Moldova. In April 2010, Romania offered to Moldova development aid worth of €100 million while the number of scholarships for Moldovan students will double to 5,000.[58] According to a lending agreement signed in February 2010, Poland will provide US$15 million and will support Moldova in its European integration efforts.[59] The first joint meeting of the Governments of Romania and Moldova, held in March 2012, concluded with several bilateral agreements in various fields.[60][61] The European orientation “has been the policy of Moldova in recent years and this is the policy that must continue,” Nicolae Timofti told lawmakers before his election.”[62]

Military

The Moldovan armed forces consist of the Ground Forces and Air and Air Defense Forces. Moldova has accepted all relevant arms control obligations of the former Soviet Union. On October 30, 1992, Moldova ratified the Treaty on Conventional Armed Forces in Europe, which establishes comprehensive limits on key categories of conventional military equipment and provides for the destruction of weapons in excess of those limits. The country acceded to the provisions of the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty in October 1994 in Washington, D.C. It does not have nuclear, biological, or chemical weapons. Moldova joined the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation's Partnership for Peace on March 16, 1994.

Moldova is committed to a number of international and regional control of arms regulations such as the UN Firearms Protocol, Stability Pact Regional Implementation Plan, the UN Programme of Action (PoA) and the OSCE Documents on Stockpiles of Conventional Ammunition.

Human rights

According to Amnesty International, "Torture and other ill-treatment in police detention remained widespread; the state failed to carry out prompt and impartial investigations and police officers sometimes evaded penalties. Political dissidents from Ilaşcu Group were released from arbitrary detention only after an order of the European Court of Human Rights.[63] In 2009, when Moldova experienced its most serious civil unrest in a decade, several civilians like Valeriu Boboc were killed by police and many more injured.[64] According to Human Rights Report of the United States Department of State, released in April 2011, "In contrast to the previous year, there were no reports of killings by security forces. During the year reports of government exercising undue influence over the media substantially decreased." But "Transnistrian authorities continued to harass independent media and opposition lawmakers; restrict freedom of association, movement, and religion; and discriminate against Romanian speakers."[65] Moldova "has made “noteworthy progress” on religious freedom since the era of the Soviet Union, but it can still take further steps to foster diversity," said the UN Special Rapporteur on freedom of religion or belief Heiner Bielefeldt, in Chișinău, in September 2011.[66]

Administrative divisions

Moldova is divided into thirty-two districts (raioane, singular raion), three municipalities and two autonomous regions (Gagauzia and Transnistria).[67] The final status of Transnistria is disputed, as the central government does not control that territory. The cities of Comrat and Tiraspol, the administrative seats of the two autonomous territories also have municipality status. Moldova has 65 cities (towns), including the five with municipality status, and 917 communes. Some other 699 villages are too small to have a separate administration, and are administratively part of either cities (40 of them) or communes (659). This makes for a total of 1,681 localities of Moldova, all but two of which are inhabited.

Largest cities in Moldova

Source: Moldovan Census (2004); Note: 1. World Gazetteer. Moldova: largest cities 2004. 2. Pridnestrovie.net 2004 Census 2004. 3. National Bureau of Statistics of Moldova | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Pop. | Rank | Pop. | ||||||

Chișinău  Tiraspol |

1 | Chișinău | 644,204 | 11 | Comrat | 20,113 |  Bălți  Bender | ||

| 2 | Tiraspol | 129,500 | 12 | Strășeni | 18,376 | ||||

| 3 | Bălți | 102,457 | 13 | Durlești | 17,210 | ||||

| 4 | Bender | 91,000 | 14 | Ceadîr-Lunga | 16,605 | ||||

| 5 | Rîbnița | 46,000 | 15 | Căușeni | 15,939 | ||||

| 6 | Ungheni | 30,804 | 16 | Codru | 15,934 | ||||

| 7 | Cahul | 30,018 | 17 | Edineț | 15,520 | ||||

| 8 | Soroca | 22,196 | 18 | Drochia | 13,150 | ||||

| 9 | Orhei | 21,065 | 19 | Ialoveni | 12,515 | ||||

| 10 | Dubăsari | 25,700 | 20 | Hîncești | 12,491 | ||||

Geography

Moldova lies between latitudes 45° and 49° N, and mostly between meridians 26° and 30° E (a small area lies east of 30°).The total land area is 33,851 km2

The largest part of the nation lies between two rivers, the Dniester and the Prut. The western border of Moldova is formed by the Prut river, which joins the Danube before flowing into the Black Sea. Moldova has access to the Danube for only about 480 m (1,575 ft), and Giurgiulești is the only Moldovan port on the Danube. In the east, the Dniester is the main river, flowing through the country from north to south, receiving the waters of Răut, Bâc, Ichel, Botna. Ialpug flows into one of the Danube limans, while Cogâlnic into the Black Sea chain of limans.

The country is landlocked, even though it is very close to the Black Sea. While most of the country is hilly, elevations never exceed 430 m (1,411 ft) — the highest point being the Bălănești Hill. Moldova's hills are part of the Moldavian Plateau, which geologically originate from the Carpathian Mountains. Its subdivisions in Moldova include Dniester Hills (Northern Moldavian Hills and Dniester Ridge), Moldavian Plain (Middle Prut Valley and Bălţi Steppe), and Central Moldavian Plateau (Ciuluc-Soloneţ Hills, Cornești Hills (Codri Massive; "Codri" meaning "forests"), Lower Dniester Hills, Lower Prut Valley, and Tigheci Hills). In the south, the country has a small flatland, the Bugeac Plain. The territory of Moldova east of the river Dniester is split between parts of the Podolian Plateau, and parts of the Eurasian Steppe.

The country's main cities are the capital Chișinău, in the center of the country, Tiraspol (in the eastern region of Transnistria), Bălţi (in the north) and Bender (in the south-east). Comrat is the administrative center of Gagauzia.

Climate

Moldova's proximity to the Black Sea gives it a mild and sunny climate.[68]

Moldova's climate is moderately continental: The summers are warm and long, with temperatures averaging about 20 °C (68 °F), and the winters are relatively mild and dry, with January temperatures averaging −4 °C (25 °F). Annual rainfall, which ranges from around 600 mm (24 in) in the north to 400 mm (16 in) in the south, can vary greatly; long dry spells are not unusual. The heaviest rainfall occurs in early summer and again in October; heavy showers and thunderstorms are common. Because of the irregular terrain, heavy summer rains often cause erosion and river silting.

The highest temperature ever recorded in Moldova was 41.5 °C (106.7 °F) on July 21, 2007 in Camenca.[69] The lowest temperature ever recorded was −35.5 °C (−31.9 °F) on January 20, 1963 in Brătușeni, Edineţ county.[70]

Economy

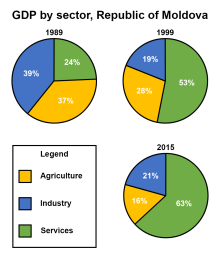

Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, the relative weight of the service sector in the economy of Moldova started to grow and began to dominate the GDP (now about 63,5%), as a result of decrease in industry and agriculture. The main economic indicators contracted dramatically.

Energy

Moldova imports all of its supplies of petroleum, coal, and natural gas, largely from Russia. Moldova is a partner country of the EU INOGATE energy programme, which has four key topics: enhancing energy security, convergence of member state energy markets on the basis of EU internal energy market principles, supporting sustainable energy development, and attracting investment for energy projects of common and regional interest.[71]

Economic reforms

After the breakup of the Soviet Union in 1991, energy shortages contributed to sharp production declines. As part of an ambitious economic liberalization effort, Moldova introduced a convertible currency, liberalized all prices, stopped issuing preferential credits to state enterprises, backed steady land privatization, removed export controls, and liberalized interest rates. The government entered into agreements with the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund to promote growth.

Recent trends indicate that the Communist government intends to reverse some of these policies, and recollectivise land while placing more restrictions on private business. The economy returned to positive growth, of 2.1% in 2000 and 6.1% in 2001. Growth remained strong in 2007 (6%), in part because of the reforms and because of starting from a small base. The economy remains vulnerable to higher fuel prices, poor agricultural weather, and the skepticism of foreign investors.[citation needed]

Following the regional financial crisis in 1998, Moldova has made significant progress towards achieving and retaining macroeconomic and financial stabilization. It has, furthermore, implemented many structural and institutional reforms that are indispensable for the efficient functioning of a market economy. These efforts have helped maintain macroeconomic and financial stability under difficult external circumstances, enabled the resumption of economic growth and contributed to establishing an environment conducive to the economy's further growth and development in the medium term.[citation needed]

Despite these efforts and recent resumption of economic growth, Moldova ranks low in terms of commonly used living standards and human development indicators in comparison with other transition economies. Although the economy experienced a constant economic growth after 2000: with 2.1%, 6.1%, 7.8% and 6.3% between 2000 and 2003 (with a forecast of 8% in 2004), one can observe that these latest developments hardly reach the level of 1994, with almost 40% of the GDP registered in 1990. Thus, during the last decade little has been done to reduce the country's vulnerability. After a severe economic decline, social and economic challenges, energy uprooted dependencies, Moldova continues to occupy one of the last places among European countries in income per capita.[citation needed]

In 2005, according to the Human Development Report, the registered GDP per capita was US$ 2,100 PPP, which was 4.5 times lower than the world average at the time (US $ 9,543). Moreover, GDP per capita was under the average of its statistical region (US $ 9,527 PPP). In 2005, about 20.8% of the population were under the absolute poverty line and registered an income lower than US $ 2.15 (PPP) per day. Moldova is classified as medium in human development and is at the 111th spot in the list of 177 countries. The value of the Human Development Index (0.708) is below the world average. Moldova remains the poorest country in Europe in terms of official (i.e., excluding the black and grey economy) per capita which currently stands at $3,400 [72] The GDP(PPP) in 2011 constituted $12.15 billion.[73]

Wine industry

Moldova is known for its wines. For many years viticulture and winemaking in Moldova were the general occupation of the population. Evidence of this is present in historical memorials and documents, folklore, and the Moldovan spoken language.

The country has a well established wine industry. It has a vineyard area of 147,000 hectares (360,000 acres), of which 102,500 ha (253,000 acres) are used for commercial production. Most of the country's wine production is made for export. Many families have their own recipes and strands of grapes that have been passed down through the generations.

According to a 2011 WHO report, Moldova consumed the highest amount of alcohol per capita in the world in 2005.[74]

Agriculture

Moldova's rich soil and temperate continental climate (with warm summers and mild winters) have made the country one of the most productive agricultural regions since ancient times, and a major supplier of agricultural products in southeastern Europe. In agriculture, the economic reform started with the land cadastre reform.

Tourism

Tourism focuses on the country's natural landscapes and its history. Wine tours are offered to tourists across the country. Vineyards/cellars include Cricova, Purcari, Ciumai, Romanesti, Cojușna, Milestii Mici.

Transport

The main means of transportation in Moldova are railroads 1,138 km (707 mi) and a highway system (12,730 km (7,910 mi)* overall, including 10,937 km (6,796 mi)* of paved surfaces). The sole international air gateway of Moldova is the Chișinău International Airport. The Giurgiulești terminal on the Danube is compatible with small seagoing vessels. Shipping on the lower Prut and Nistru rivers plays only a modest role in the country's transportation system.

Telecommunications

The first million of mobile telephone users was registered in September 2005. The number of mobile telephone users in Moldova increased by 47.3% in the first quarter of 2008 against the last year and exceeded 2.89 million.[75]

In September 2009, Moldova was the first country in the world to launch high-definition voice services (HD voice) for mobile phones, and the first country in Europe to launch 14.4 Mbit/s mobile broadband at a national scale, with over 40% population coverage.[76]

As of 2010[update] there are around 1,295,000 Internet users in Moldova with overall Internet penetration of 35.9%.[77]

On 6 June 2012, the Government approved the licensing of 4G / LTE for mobile operators.[78]

Demographics

Cultural and ethnic composition

The last reference data is that of the 2004 Moldovan Census[2] (areas controlled by the central government), and the 2004 Census in Transnistria (areas controlled by the breakaway authorities, including Transnistria, Bender/Tighina, and four neighboring communes):

| Self-identification | Moldovan census |

% Core Moldova |

Transnistrian census |

% Transnistria + Bender |

Total | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MoldovansA | 2,564,849 | 75.81% | 177,382 | 31.94% | 2,742,231 | 69.62% |

| Ukrainians | 282,406 | 8.35% | 160,069 | 28.82% | 442,475 | 11.23% |

| Russians | 201,218 | 5.95% | 168,678 | 30.37% | 369,896 | 9.39% |

| Gagauz | 147,500 | 4.36% | 4,096 | 0.74% | 151,596 | 3.85% |

| RomaniansA | 73,276 | 2.17% | 253 | 0.05% | 73,529 | 1.87% |

| Bulgarians | 65,662 | 1.94% | 13,858 | 2.50% | 79,520 | 2.02% |

| Romani | 12,271 | 0.36% | 507 | 0.09% | 12,778 | 0.32% |

| Poles | 2,383 | 0.07% | 1,791 | 0.32% | 4,174 | 0.11% |

| Others / undeclared | 30,159 | 0.89% | 27,454 | 4.94% | 57,613 | 1.46% |

| TOTAL | 3,383,332 | 100% | 555,347 | 100% | 3,938,679 | 100% |

A There is an ongoing controversy whether Romanians and Moldovans are the same ethnic group, namely whether Moldovans' self-identification constitutes an ethnic group distinct and apart from Romanians or a subset. There were also numerous allegations that the ethnic affiliation numbers were rigged, 7 out of 10 observer groups of the Council of Europe reported a significant number of cases when census-takers recommended respondents to declare themselves Moldovans rather than Romanians. Complicating the interpretation of the results, 18.8% of respondents that identified themselves as Moldovans declared Romanian to be their native language.[79]

Languages

The Constitution of 1994 states that the national language of the Republic of Moldova is Moldovan, and its writing is based on the Latin alphabet.[80] The 1991 Declaration of Independence names the official language Romanian.[81][82] The 1989 State Language Law speaks of a Moldovan-Romanian linguistic identity.

There is a controversy over the name of the main ethnicity of the Republic of Moldova. During 2003–2009, the Communist government adopted a national political conception which states that one of the priorities of the national politics of the Republic of Moldova is the insurance of the existence of the Moldovan language.[83][84] Scholars agree that Moldovan and Romanian are the same language, with the glottonym "Moldovan" used in certain political contexts.[85]

Russian is provided with the status of a "language of interethnic communication" (alongside the official language), and in practice remains widely used on all levels of the society and the state. The above-mentioned national political conception also states that Russian-Moldovan bilingualism is characteristic for Moldova.[84]

As of the 2004 census, the country has significant Russian (6%) and Ukrainian (8.4%) populations. 50% of ethnic Ukrainians, 27% of Gagauz, 35% of Bulgarians, and 54% of smaller ethnic groups speak Russian as their first language. In total, there are 541,000 people (or 16% of the population) in Moldova who use Russian as their first language, including 130,000 ethnic Moldovans. On the other hand, 47,000 members of ethnic minorities use Romanian as their first language.

Gagauz and Ukrainian have significant regional speaker populations and are granted official status together with Russian in Gagauzia and Transnistria respectively.

| Population of Moldova | Moldovan (Romanian) | Russian | Ukrainian | Gagauz | Bulgarian | Other languages or undeclared |

| by native language | 2,588,355 76.51% |

380,796 11.26% |

186,394 5.51% |

137,774 4.07% |

54,401 1.61% |

35,612 1.04% |

| by language of first use | 2,543,354 75.17% |

540,990 15.99% |

130,114 3.85% |

104,890 3.10% |

38,565 1.14% |

25,419 0.75% |

From 1996, the Republic, also being Romance-speaking, is a full member of Francophonia. Therefore the French language occupies the principal place among the foreign languages. In 2009/10 it was taught to 52% of schoolchildren as the first foreign language and to 7% as the second. It is followed by English having 48% and 6% respectively, and German, which was taught to 3% altogether.[86]

Religion

For the 2004 census, Orthodox Christians, who make up 93.3% of Moldova's population, were not required to declare the particular of the two main churches they belong to. The Moldovan Orthodox Church, autonomous and subordinated to the Russian Orthodox Church, and the Orthodox Church of Bessarabia, autonomous and subordinated to the Romanian Orthodox Church, both claim to be the national church of the country. 1.9% of the population is Protestant, 0.9% belongs to other religions, 1.0% is non-religious, 0.4% is atheist, and 2.2% did not answer the religion question at the census.

Education

There are 16 state and 15[87] private institutions of higher education in Moldova, with a total of 126,100 students, including 104,300 in the state institutions and 21,700 in the private ones. The number of students per 10,000 inhabitants in Moldova has been constantly growing since the collapse of the Soviet Union, reaching 217 in 2000–2001, and 351 in 2005–2006.

The National Library of Moldova was founded in 1832. The Moldova State University and the Academy of Sciences of Moldova, the main scientific organizations of Moldova, were established in 1946.

Crime

The CIA World Factbook lists widespread crime and underground economic activity among major crime issues in Moldova.[8]

Health

The average birth rate is at 1.5 children per woman.[88] Public expenditure on health was 4.2% of the GDP and private expenditure on health 3.2%.[88] There are about 264 physicians per 100,000 people.[88] Health expenditure was 138 US$ (PPP) per capita in 2004.[88]

Since the breakup of the Soviet Union, the country has seen a decrease in spending on health care and, as a result, the tuberculosis incidence rate in the country has grown.[89] Because of this, Moldova is struggling with one of the highest incidence rates of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in the world.[90]

Emigration

Emigration is a mass phenomenon in Moldova and has a major impact on the country's demographics and economy. The Moldovan Intelligence and Security Service has estimated that 600,000 to one million Moldovan citizens (almost 25% of the population) are working abroad.[91]

Culture

Located geographically at the crossroads of Latin, Slavic and other cultures, Moldova has enriched its own culture adopting and maintaining some of the traditions of its neighbors and of other influence sources.

The country's cultural heritage was marked by numerous churches and monasteries built by the Moldavian ruler Stephen the Great in the 15th century, by the works of the later renaissance Metropolitans Varlaam and Dosoftei, and those of scholars such as Grigore Ureche, Miron Costin, Nicolae Milescu, Dimitrie Cantemir,[92] Ion Neculce. In the 19th century, Moldavians from the territories of the medieval Principality of Moldavia, then split between Austria, Russia, and an Ottoman-vassal Moldavia (after 1859, Romania), made a significant contribution to the formation of the modern Romanian culture. Among these were many Bessarabians, such as Alexandru Donici, Alexandru Hâjdeu, Bogdan Petriceicu Hasdeu, Constantin Stamati, Constantin Stamati-Ciurea, Costache Negruzzi, Alecu Russo, Constantin Stere.

Mihai Eminescu, a late Romantic poet, and Ion Creangă, a writer, are the most influential Romanian language artists, considered national writers both in Romania and Moldova.[93]

The largest ethnic group is a speaker of Romanian and share the Romanian culture. Their culture has been also influenced (through Eastern Orthodoxy) by the Byzantine culture.[citation needed]

The country has also important minority ethnic communities. Gagauz, 4.4% of the population, are Christian Turkic people. Greeks, Armenians, Poles, Ukrainians, although not numerous, were present since as early as 17th century, and had left cultural marks. The 19th century saw the arrival of many more Ukrainians from Podolia and Galicia, as well as new communities, such as Lipovans, Bulgarians and Bessarabian Germans.

In the second part of the 20th century, Moldova saw a massive Soviet immigration, which brought with it many elements of Soviet culture.

Popular media

In October 1939, Radio Basarabia, a local station of the Romanian Radio Broadcasting Company, was the first radio station opened in Chișinău. Television in Moldova was introduced in April 1958, within the framework of Soviet television. Through cable, Moldovan viewers can receive a large number of Russian channels, a few Romanian channels, and several Russian language versions of international channels in addition to several local channels. One Russian and two local channels are aired.

Food and beverage

Moldovan cuisine is similar to neighboring Romania, and has been influenced by elements of Russian, Turkish, and Ukrainian cuisine. Main dishes include beef, pork, potatoes, cabbage, and a variety of cereals. Popular alcoholic beverages are divin (Moldovan brandy), beer, and local wine.

Total recorded adult alcohol consumption is approximately evenly split between spirits, beer and wine; and the average annual adult per capita consumption, in terms of pure alcohol, in 2003–2005, was 18.2 litres, the highest in the world.[94]

Music

Among Moldova's most prominent composers are Gavriil Musicescu, ștefan Neaga and Eugen Doga.

In the field of popular music, Moldova has produced the band O-Zone, who came to prominence in 2003, with their hit song "Dragostea Din Tei." Moldova has been participating in the Eurovision Song Contest since 2005. Another popular band from Moldova is ska rock band that represented the country in the 2005 Eurovision Song Contest, finishing 6th.

In May 2007, Natalia Barbu represented Moldova in Eurovision Song Contest 2007 with her entry "Fight", in Finland, Helsinki. Natalia squeezed into the final by a very small margin. Her rock song was aggressive in nature and performance. She took 10th place with 109 points. Then Zdob și Zdub again represented Moldova in the 2011 Eurovision Song Contest, finishing 12th. Dan Bălan, another popular artist, released the album Chica Bomb in 2010.

The band SunStroke Project with Olia Tira represented the country in the 2010 Eurovision Song Contest with their hit song "Run Away". Their performance gained international notoriety as an internet meme due to the pelvic thrusting and dancing of Sergey Stepanov, the band saxophonist. He has been fittingly dubbed "Epic Sax Guy".

Among most prominent classical musicians in Moldova are Mark Pester, a distinguished violinist, conductor and the first professor of the State Conservatory. Mark Pester was a student of the famous violin teacher Leopold Auer at the St. Petersburg Conservatory. As a conductor, he staged the first operas in Moldova and performed with the greatest soloists including Sergei Rachmaninov. Other prominent classical musicians in Moldova are Maria Biesu, one of the leading world's sopranos and the winner of the Japan International Competition; pianist Mark Zeltser, winner of the USSR National Competition, Margueritte Long Competition in Paris and Busoni Competition in Bolzano, Italy. Another outstanding pianist is Oleg Maisenberg, the winner of the Schubert International Competition in Vienna.

Holidays

Most retail businesses close on New Year's Day and Independence Day, but remain open on all other holidays.

Sport

Trânta (a form of wrestling) is the national sport in Moldova. Association football is the most popular sport in Moldova.[citation needed]

Rugby union is popular as well. Registered players have doubled, and almost 10,000 spectators turn up at every European Nations Cup match.[citation needed] The most prestigious cycling race is the Moldova President's Cup, which was first run in 2004.

In the 2012 Summer Olympics, Cristina Iovu won the Bronze Medal in the Women's Weightlifting Competition (Women's weight class 48–53 kg).[95]

See also

References

- ^ "Preliminary number of resident population in the Republic of Moldova as of January 1, 2012" (Press release). National Bureau of Statistics of Moldova. February 8, 2012. Retrieved February 18, 2012.

- ^ a b Template:Ro icon National Bureau of Statistics of Moldova

- ^ Template:Ru icon 2004 census in Transnistria

- ^ a b c d "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects". World Economic Outlook Database. International Monetary Fund. October 2012. Retrieved January 22, 2013.

- ^ "Human Development Report 2011" (PDF). United Nations. 2011. Retrieved 20 January 2012.

- ^ Dictionary Reference: Moldova: /mɔːlˈdoʊvə/

- ^ The Free Dictionary: Moldova: /mɒlˈdoʊvə/, /mɔːlˈdoʊvə/

- ^ a b "Moldova". CIA World Factbook.

- ^ "Moldova will prove that it can and has chances to become EU member,". Moldpress News Agency. June 19, 2007. Archived from the original on 2008-04-30.

- ^ "Moldova-EU Action Plan Approved by European Commission". moldova.org. December 14, 2004. Retrieved July 2, 2007.

- ^ History, Official site of Republic of Moldova

- ^ Where did the name Moldova come from?

- ^ Constantinescu, Bogdan; Bugoi, Roxana; Pantos, Emmanuel; Popovici, Dragomir (2007). "Phase and chemical composition analysis of pigments used in Cucuteni Neolithic painted ceramics" (PDF). Documenta Praehistorica. XXXIV. Ljubljana: Department of Archaeology, Faculty of Arts, University of Ljubljana: 281–288. ISSN 1408-967X. OCLC 41553667. Retrieved 25 October 2012.

- ^ "Moldova". Library of Congress Country Studies

- ^ Bessarabia by Charles Upson Clark, 1927, chapter 10: "Naturally, this system resulted not in acquisition of Russian by the Moldavians, but in their almost complete illiteracy in any language."

- ^ Vasile Baican, "Human settlements in Moldavia represented on «the Russian map» between 1828-1829", Scientific Annals of "Alexandru Ioan Cuza" University of Iasi - Geography series, 54, 2008, p. 65.

- ^ Bessarabia by Charles Upson Clark, 1927, chapter 8: "Today, the Bulgarians form one of the most solid elements in Southern Bessarabia, numbering (with the Gagauzes, i.e., Turkish-speaking Christians also from the Dobrudja) nearly 150,000. Colonization brought in numerous Great Russian peasants, and the Russian bureaucracy imported Russian office-holders and professional men; according to the Romanian estimate of 1920, there were about Great Russians were about 75,000 in number (2.9%), and the Lipovans and Cossacks 59,000 (2.2%); the Little Russians (Ukrainians) came to 254,000 (9.6%). That, plus about 10,000 Poles, brings the total number of Slavs to 545,000 in a population of 2,631,000, or about one-fifth"

- ^ The Germans from Bessarabia

- ^ The Jewish minority was more numerous in the past (228,620 Jews in Bessarabia in 1897, or 11.8% of the population). [1].

- ^ Mennonite-Nogai Economic Relations, 1825–1860

- ^ Ion Nistor, Istoria Bassarabiei, Cernăuţi, 1921

- ^ Template:De icon Flavius Solomon, Die Republik Moldau und ihre Minderheiten (Länderlexikon), in: Ethnodoc-Datenbank für Minderheitenforschung in Südostosteuropa, p. 52

- ^ Moldova

- ^ Template:Fr icon Anthony Babel: La Bessarabie (Bessarabia), Félix Alcan, Genève, Switzerland, 1931

- ^ King, Charles (2000). "From Principality to Province". The Moldovans: Romania, Russia, and the politics of culture. Hoover Press. pp. 33–35. ISBN 0-8179-9792-X. Retrieved 2010-10-31.

- ^ Template:Ro icon PRM.md, "Sfatul Ţării ... proclaimed the Moldavian Democratic Republic"

- ^ Charles Upson Clark (1927). "24:The Decay of Russian Setiment". Bessarabia: Russia and Romania on the Black Sea – View Across Dniester From Hotin Castle. New York: Dodd, Mead & Company. Retrieved 2010-10-31.

- ^ Ion Pelivan (Chronology)

- ^ Petre Cazacu (Moldova, pp. 240–245).

- ^ Cristina Petrescu, "Contrasting/Conflicting Identities:Bessarabians, Romanians, Moldovans" in Nation-Building and Contested Identities, Polirom, 2001, pg. 156

- ^ Malbone W. Graham (1944). "The Legal Status of the Bukovina and Bessarabia". The American Journal of International Law. 38 (4). American Society of International Law: 667–673. doi:10.2307/2192802. JSTOR 2192802.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Mitrasca, Marcel (2002). "Introduction". Moldova: a Romanian province under Russian rule: diplomatic history from the archives of the great powers. Algora Publishing. p. 13. ISBN 1-892941-86-4. Retrieved 2010-10-31.

- ^ Wayne S. Vucinich, Bessarabia In: Collier's Encyclopedia (Crowell Collier and MacMillan Inc., 1967) vol. 4, p. 103

- ^ a b Olson, James (1994). An Ethnohistorical Dictionary of the Russian and Soviet Empires. p. 483.

- ^ Note: Further 11,844 were deported on 12–13 June 1941 from other Romanian territories occupied by the USSR a year earlier.

- ^ a b c d Template:Ro icon Tismăneanu Report, pages 747 and 752

- ^ Michael Ellman, The 1947 Soviet Famine and the Entitlement Approach to Famines Cambridge Journal of Economics 24 (2000): 603–630.

- ^ Pal Kolsto, National Integration and Violent Conflict in Post-Soviet Societies: The Cases of Estonia and Moldova, Rowman & Littlefield, 2002, ISBN 0-7425-1888-4, pg. 202

- ^ "Architecture of Chișinău". on Kishinev.info. Retrieved 2008-10-12.

- ^ a b c d e f g Template:Ro Horia C. Matei, "State lumii. Enciclopedie de istorie." Meronia, București, 2006, p. 292-294

- ^ "Romanian Nationalism in the Republic of Moldova" by Andrei Panici, American University in Bulgaria, 2002; pages 40 and 41

- ^ Legea cu privire la functionarea limbilor vorbite pe teritoriul RSS Moldovenesti Nr.3465-XI din 01.09.89 Vestile nr.9/217, 1989[dead link] (Law regarding the usage of languages spoken on the territory of the Republic of Moldova): "Moldavian SSR supports the desire of the Moldovans that live across the borders of the Republic, and considering the existing linguistic Moldo-Romanian identity — of the Romanians that live on the territory of the USSR, of doing their studies and satisfying their cultural needs in their native language."

- ^ "[[Ion Costaș]]: 7 APRILIE 2009 NE AMINTEșTE DE 10 NOIEMBRIE 1989" (in Romanian). Basarabia Literară .ro. 28 February 2010. Retrieved 21 March 2012.

{{cite web}}: URL–wikilink conflict (help) - ^ "[[Igor Cașu]], Chișinău 7 noiembrie 1989: "Jos dictatura comunistă!"" (in Romanian). Radio Free Europe. 7 November 2009. Retrieved 21 March 2012.

{{cite web}}: URL–wikilink conflict (help) - ^ "Moldova: Information Campaign to Increase the Efficiency of Remittance Flows". International Organization for Migration. 10 December 2008.

- ^ Marandici, Ion, The Factors Leading to the Electoral Success, Consolidation and Decline of the Moldovan Communists' Party During the Transition Period (April 23, 2010). Presented at the Midwestern Political Science Association Convention from April 2010. Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1809029

- ^ SevenTimes.ro: "Supporting actions for Moldova's riot", 08 April 2009

- ^ "The protest initiative group: LDPM is the guilty one for the devastations in the Chișinău downtown[dead link]", April 08, 2009

- ^ "EU flags flying on the Presidency and Parliament, to calm the masses", June 02, 2009

- ^ Reuters, Moldovan referendum appears to flop on low turnout

- ^ "Moldova going to third election in two years". BBC News. 28 September 2010. Retrieved 30 September 2010.

- ^ "Marian Lupu elected Head of Parliament". allmoldova. 30 November 2010. Retrieved 27 October 2011.

- ^ a b The Constitution of the Republic of Moldova, 2000. Retrieved 31-10-2010.

- ^ "Moldova Calls On Russian Troops To Leave Transdniestr".[dead link]

- ^ The New York Times, Shooting at Checkpoint Raises Tensions in a Disputed Region Claimed by Moldova

- ^ EU to grant €90 million to crisis-hit Moldova

- ^ "Moldova to get $570 million in IMF loans | Ex-Soviet States | RIA Novosti". En.rian.ru. 2010-01-30. Retrieved 2012-11-25.

- ^ Romania, Moldova to Boost Relations

- ^ Poland will support Moldova in its European integration efforts

- ^ First meeting of Romania and Rep. of Moldova Governments, concluded with initialling of several bilateral agreements[dead link]

- ^ Joint meeting of the Government of Romania and Government of the Republic of Moldova

- ^ Washington Post, Moldova elects pro-European judge Timofti as president, ending 3 years of political deadlock[dead link]

- ^ Ilascu and Others vs. Moldova and Russia

- ^ Bureau of Diplomatic Security, Moldova 2011 Crime and Safety Report

- ^ United States Department of State, 2010 Human Rights Report: Moldova

- ^ Moldova: UN human rights expert calls for more fostering of religious diversity

- ^ "Autorităţi publice locale". Government of Moldova. Retrieved 12 October 2010.

- ^ Moldova's Climate

- ^ Camenca temperature

- ^ Bratuseni temperature

- ^ "INOGATE website".

- ^ web|url=http://www.indexmundi.com/moldova/gdp_per_capita_(ppp).html

- ^ web|url=http://www.indexmundi.com/moldova/gdp_(purchasing_power_parity).html

- ^ "Global Status Report on Alcohol and Health 2011, Appendix III" (PDF). World Health Organization. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- ^ Template:Ro icon R. Moldova are deja peste două milioane de utilizatori ai serviciilor de telefonie mobilă – Agenţia Naţionala pentru Reglementare în Comunicaţii Electronice și Tehnologia Informaţiei (ANRCETI)

- ^ Katie Allen (31 December 2009). "Orange launches HD mobile phone service". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 September 2010.

- ^ International Telecommunication Union – BDT

- ^ UNIMEDIA (6 June 2013). "the Government approved the licensing of 4G / LTE for mobile operators". UNIMEDIA. Retrieved 10 March 2013.

- ^ Protsyk, Oleh (1 January 2007). "Nation-building in Moldova". Nation and Nationalism. Political and Historical Studies (PDF). Andrzej Marcin Suszycki, Ireneusz Pawel Karolewski. Oficyna Wydawnicza Atut Wrocawskie Wydawn. Oswiatowe. ISBN 978-83-7432-261-4.

- ^ "Article 13, line 1 – of Constitution of Republic of Moldova".

- ^ Template:Ro Declaraţia de independenţa a Republicii Moldova, Moldova Suverană

- ^ A Field Guide to the Main Languages of Europe – Spot that language and how to tell them apart[dead link], on the website of the European Commission

- ^ The law regarding approval of the National Political Conception of the Republic of Moldova stipulates that "The conception is rooted in the historically established truth and confirmed by the common literary treasure: Moldovan nation and Romanian nation use a common literary form "which is based on the live spring of the popular talk from Moldova" — a reality which impregnates the national Moldovan language with a specific peculiar pronunciation, a certain well known and appreciated charm. Having the common origin; common basic lexical vocabulary, the national Moldovan language and national Romanian language keep each their lingvonim/glotonim as the identification sign of each nation: Moldovan and Romanian.'"

- ^ a b Template:Ro icon "Concepţia politicii naţionale a Republicii Moldova" Moldovan Parliament

- ^ "Marian Lupu: Româna și moldoveneasca sunt aceeași limbă". Realitatea .NET. Retrieved 2009-10-07.

- ^ Moldavie.fr – Portail francophone de la Moldavie: Le français, première langue étrangère enseignée en Moldavie Template:Fr icon

- ^ Moldovanu-Batrinac, Viorelia (18 December 2006). "Bologna Process Template for National Reports: 2005–2007 (Moldova)" (PDF). Bologna Process website. European Higher Education Area. p. 3. Retrieved July 2, 2010.

- ^ a b c d "Human Development Report 2009 – Moldova". Hdrstats.undp.org. Retrieved 2009-10-07.

- ^ "Pulitzer Center Reporting on MDR-TB in Moldova".

- ^ "Tuberculosis,Former Soviet Nations, China Face High MDR-TB Prevalence".

- ^ Understanding Migration, Emigration from Moldova

- ^ Prince Dimitrie Cantemir was one of the most important figures of Moldavian culture of the 18th century. He wrote the first geographical, ethnographic and economic description of the country. Template:La icon Descriptio Moldaviae, (Berlin, 1714), at Latin Wikisource

- ^ Biography of Mihai Eminescu at poemhunter.com

Mihai Eminescu at creatingculturalcapitals.eu

Moldova at refugeesinpa.org

2000: Year of Eminescu at Central Europe Review

Moldova at explore.theculturetrip.com - ^ WHO Global Alcohol Report, Republic of Moldova

- ^ "Moldova Olympic Team Medals | London Olympics - Yahoo! Sports". Sports.yahoo.com. 2011-04-20. Retrieved 2012-11-25.

External links

- Official website

- "Moldova". The World Factbook (2024 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency.

- Moldova, Republic of from UCB Libraries GovPubs.

- Template:Dmoz

- Moldova profile from the BBC News.

Wikimedia Atlas of Moldova

Wikimedia Atlas of Moldova Geographic data related to Moldova at OpenStreetMap

Geographic data related to Moldova at OpenStreetMap- Key Development Forecasts for Moldova from International Futures.

- Moldova

- Countries in Europe

- Member states of La Francophonie

- Member states of the Commonwealth of Independent States

- Landlocked countries

- Republics

- Romanian-speaking countries and territories

- Russian-speaking countries and territories

- States and territories established in 1991

- Ukrainian-speaking countries and territories

- Areas of traditional spread of Ukrainians and Ukrainian language

- Member states of the United Nations