Pisco sour

| IBA official cocktail | |

|---|---|

Peruvian pisco sour | |

| Type | Cocktail |

| Base spirit | |

| Served | Straight up: chilled, without ice |

| Standard garnish | Angostura bitters (1 dash) |

| Standard drinkware | |

| IBA specified ingredients† |

|

| Preparation | Vigorously shake contents in a cocktail shaker with ice cubes, then strain into a glass and garnish with bitters.[1] |

| Commonly served | All day |

| † Pisco sour recipe at International Bartenders Association | |

A pisco sour is an Peruvian alcoholic cocktail of that is typical of Peruvian cuisine as well as the national drink of Peru. The drink's name comes from pisco, which is its base liquor, and the cocktail term sour, about sour citrus juice and sweetener components. The Peruvian pisco sour uses Peruvian pisco as the base liquor and adds freshly squeezed lemon juice, simple syrup, ice, egg white, and Angostura bitters. The Chilean version is similar, but uses Chilean pisco and Pica lime, and excludes the bitters and egg white. Other variants of the cocktail include those created with fruits like pineapple or plants such as coca leaves.

Although the preparation of pisco-based mixed beverages possibly dates back to the 1700s, historians and drink experts agree that the cocktail as it is known today was invented in the early 1920s in Lima, the capital of Peru, by the American bartender Victor Vaughen Morris.[2] Morris left the United States in 1903 to work in Cerro de Pasco, a city in central Peru. In 1916, he opened Morris' Bar in Lima, and his saloon quickly became a popular spot for the Peruvian upper class and English-speaking foreigners. The oldest known mentions of the pisco sour are found in newspaper and magazine advertisements, dating to the early 1920s, for Morris and his bar published in Peru and Chile. The pisco sour underwent several changes until Mario Bruiget, a Peruvian bartender working at Morris' Bar, created the modern Peruvian recipe for the cocktail in the latter part of the 1920s by adding Angostura bitters and egg whites to the mix.

Cocktail connoisseurs consider the pisco sour a South American classic.[A] Chile and Peru both claim the pisco sour as their national drink, and each asserts ownership of the cocktail's base liquor—pisco;[B] consequently, the pisco sour has become a significant and oft-debated topic of Latin American popular culture. Media sources and celebrities commenting on the dispute often express their preference for one cocktail version over the other, sometimes just to cause controversy. Some pisco producers have noted that the controversy helps promote interest in the drink. The two kinds of pisco and the two variations in the style of preparing the pisco sour are distinct in both production and taste. Peru celebrates a yearly public holiday in honor of the cocktail on the first Saturday of February.

Name

The term sour refers to mixed drinks containing a base liquor (bourbon or some other whiskey), lemon or lime juice, and a sweetener.[6] Pisco refers to the base liquor used in the cocktail. The word as applied to the alcoholic beverage comes from the Peruvian port of Pisco. In the book Latin America and the Caribbean, historian Olwyn Blouet and political geographer Brian Blouet describe the development of vineyards in early Colonial Peru and how in the second half of the sixteenth century a market for the liquor formed owing to the demand from growing mining settlements in the Andes. Subsequent demand for a stronger drink caused Pisco and the nearby city of Ica to establish distilleries "to make wine into brandy",[7] and the product received the name of the port from where it was distilled and exported.[8][9]

History

Background

The first grapevines were brought to Peru shortly after its conquest by Spain in the 16th century. Spanish chroniclers from the time note the first winemaking in South America took place in the hacienda Marcahuasi of Cuzco.[10] The largest and most prominent vineyards of the 16th and 17th century Americas were established in the Ica valley of south-central Peru.[11][12] In the 1540s, Bartolomé de Terrazas and Francisco de Carabantes planted vineyards in Peru.[13] Carabantes also established vineyards in Ica, where Spaniards from Andalucia and Extremadura introduced grapevines into Chile.[13][14]

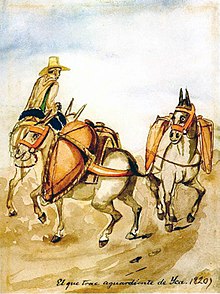

Already in the 16th century, Spanish settlers in Chile and Peru began producing aguardiente[14][15] distilled from fermented grapes.[16] Since at least 1764, Peruvian aguardiente was called "pisco" after its port of shipping;[11][12] the usage of the name "pisco" for aguardiente then spread to Chile.[C] The right to produce and market pisco, still made in Peru and Chile, is the subject of ongoing disputes between the two countries.[17]

According to historian Luciano Revoredo, the preparation of pisco with lemon dates as far back as the 18th century. He bases his claim on a source found in the Mercurio Peruano which details the prohibition of aguardiente in Lima's Plaza de toros de Acho, the oldest bullring in the Americas. At this time, the drink was named Punche (Punch), and was sold by slaves. Revoredo further argues this drink served as the predecessor of the Californian pisco punch, invented by Duncan Nicol in the Bank Exchange Bar of San Francisco, California.[18] According to a 1921 news clip from the West Coast Leader, an English-language newspaper from Peru, a saloon in San Francisco's Barbary Coast red-light district was known for its Pisco sours during "the old pre-Volstead days".[19] Culinary expert Duggan McDonnell considers that this attributes the popularity (not origin) of a pisco cocktail in San Francisco dating as far back as before the 1906 earthquake that destroyed the Barbary Coast.[19] A recipe for a pisco-based punch, including egg whites, was found by researcher Nico Vera in the 1903 Peruvian cookbook Manual de Cocina a la Criolla; consequently, McDonnell considers that "[i]t is entirely possible that the 'Cocktail' that came to be the pisco sour ... had been prepared for a reasonable time in Lima before being included in a cookbook."[20]

Origin

The pisco sour originated in Lima, Peru.[2] It was created by bartender Victor Vaughen Morris, an American from a respected Mormon family of Welsh ancestry, who moved to Peru in 1904 to work in a railway company in Cerro de Pasco.[21][22] Americans emigrated to the bustling Andean mining hub of Cerro de Pasco, then the second-largest city in Peru, for work in the business ventures established by the tycoon Alfred W. McCune.[22] Morris, who worked as a floral shop manager in Salt Lake City, joined McCune's project to construct what was then the highest-altitude railway in the world and ease the city's export of its precious metals.[22] During celebrations for the railway's completion in July 1904, Morris, tasked with overseeing the festivities, recalled first mixing pisco in a cocktail beverage after the nearly 5,000 American and Peruvian attendees (including local celebrities and dignitaries) consumed all of the available whiskey.[22]

Morris relocated to the Peruvian capital, Lima, with his Peruvian wife and three children in 1915. A year later, he opened a saloon—Morris' Bar—which became popular with both the Peruvian upper class and English-speaking foreigners.[21][22][23] Morris, who often experimented with new drinks, developed the pisco sour as a variant of the whiskey sour.[1] Chilean historian Gonzalo Vial Correa also attributes the pisco sour's invention to Gringo Morris from the Peruvian Morris Bar, but with the minor difference of naming him William Morris.[24]

Some discrepancy exists on the exact date when Morris created the popular cocktail. Mixologist Dale DeGroff asserts the drink was invented in 1915,[25] but other sources argue this happened in the 1920s.[26] The Chilean web newspaper El Mercurio Online specifically contends historians attribute the year of the drink's invention as 1922, adding that "one night Morris surprised his friends with a new drink he called pisco sour, a formula which mixes the Peruvian pisco with the American sour" (in Spanish: "Una noche Morris sorprendió a sus amigos con una nueva bebida a la que llamó pisco sour, una fórmula que funde lo peruano del pisco con el 'sour' estadounidense.").[27]

The pisco sour's initial recipe was that of a simple cocktail.[28] According to Peruvian researcher Guillermo Toro-Lira, "it is assumed that it was a crude mix of pisco with lime juice and sugar, as was the whiskey sour of those days."[29] As the cocktail's recipe continued to evolve, the bar's registry shows that customers commented on the continuously improving taste of the drink.[29] The modern Peruvian version of the recipe was developed by Mario Bruiget, a Peruvian from Chincha Alta who worked under the apprenticeship of Morris starting on July 16, 1924. Bruiget's recipe added the Angostura bitters and egg whites to the mix.[21] Journalist Erica Duecy writes that Bruiget's innovation added "a silky texture and frothy head" to the cocktail.[28]

Morris used advertisements to promote his bar and invention. The oldest known mention of the pisco sour appears in the September 1920 edition of the Peruvian magazine Hogar.[30] Another old advertisement appears in the April 22, 1921, edition of the Peruvian magazine Mundial. In the magazine, not only is the pisco sour described as a white-colored beverage but its invention is attributed to "Mister Morris."[31] Later, in 1924, with the aid of Morris' friend Nelson Rounsevell, the bar advertised its locale and invention in Valparaíso, Chile. The advertisement featured in the Valparaíso newspaper South Pacific Mail, owned by Rounsevell.[29] By 1927, Morris' Bar had attained widespread notability for its cocktails, particularly the pisco sour. Brad Thomas Parsons writes that "the registry at the Morris Bar was filled with high praise from visitors who raved about the signature drink."[21][32]

Notable attendees of Morris' Bar included the writers Abraham Valdelomar and José María Eguren, the adventurers Richard Halliburton and Dean Ivan Lamb, the anthropologist Alfred Kroeber, and the businessmen Elmer Faucett and José Lindley.[22][33] In his memoir, Lamb recalls his experience with the pisco sour in Morris' Bar, commenting that it "tasted like a pleasant soft drink" and that he felt disoriented after drinking a second one despite a bartender's stern objection that "one was usually sufficient."[22]

Spread

Over time, competition from nearby bars and Victor Morris' deteriorating health led to the decline and fall of his enterprise. Due to his worsening constitution, Morris delegated most of the bartending to his employees. Adding to the problem, nearby competitors, such as the Hotel Bolívar and the Hotel Lima Country Club, housed bars that took clientele away from Morris' Bar. Moreover, Toro-Lira discovered that Morris accused four of his former bartenders of intellectual property theft after they left to work in one of these competing establishments.[29] In 1929, Morris declared voluntary bankruptcy and closed his saloon. A few months later, on June 11, Victor Vaughen Morris died of cirrhosis.[21][29]

Historian Luis Alberto Sánchez writes that, after Morris closed his bar, some of his bartenders left to work in other locales.[21] Bruiget began working as a bartender for the nearby Grand Hotel Maury, where he continued to serve his pisco sour recipe. His success with the drink led local Limean oral tradition to associate the Hotel Maury as the original home of the pisco sour.[21] Sánchez, who in his youth also frequented Morris' Bar, writes in his memoir that two of Morris' other apprentices, Leonidas Cisneros Arteta and Augusto Rodríguez, opened their own bars.[34]

As other former apprentices of Morris found work elsewhere, they also spread the pisco sour recipe.[31] Since at least 1927, pisco sours started being sold in Chile, most notably at the Club de la Unión, a high-class gentlemen's club in downtown Santiago.[35] During the 1930s, the drink made its way into California, reaching bars as far north as the city of San Francisco.[1] Restaurateur Victor Jules Bergeron, Jr., remembers serving pisco sours at the original Trader Vic's tiki bar in Oakland, in 1934, to a traveler who had read about the cocktail in Life magazine.[36] By at least the late 1960s, the cocktail also found its way to New York.[37]

Beatriz Jiménez, a journalist from the Spanish newspaper El Mundo, indicates that back in Peru, the luxury hotels of Lima adopted the pisco sour as their own in the 1940s.[38] An oil bonanza attracted foreign attention to Peru during the 1940s and 1950s. In his 1943 guidebook promoting "inter-American understanding" during the Second World War, explorer Earl Parker Hanson writes that pisco and "the famous pisco sour" were favored by foreigners residing in Peru.[39] Among the foreign visitors to Lima were renowned Hollywood actors who were fascinated by the pisco sour.[27][40] Jiménez recollected oral traditions claiming an inebriated Ava Gardner had to be carried away by John Wayne after drinking too many pisco sours. Ernest Hemingway and Orson Welles are said to have been big fans of what they described as "that Peruvian drink."[38] In his autobiography, actor Ray Milland recalls drinking the cocktail in Lima's Government Palace during the Bustamante presidency of the 1940s, first finding it "a most intriguing drink" and then, after delivering a "brilliant dedication speech" whose success he partly attributed to the cocktail, charmingly referred to it as "the lovely pisco sour."[41]

In 1969, Sánchez wrote that the Hotel Maury still served the "authentic" Pisco sour from Morris' Bar.[34] Pan American World Airways included the pisco sour in a drinking tips section for the 1978 edition of its Encyclopedia of Travel guidebook, warning travelers to Peru that "[t]he pisco sour looks innocent, but is potent."[42] Bolivian journalist Ted Córdova Claure wrote, in 1984, that the Hotel Bolívar stood as a monument to the decadence of the Peruvian oligarchy (in Spanish: "Este hotel es un monumento a la decadencia de la oligarquía peruana."). He noted the locale as being the traditional home of the pisco sour and recommended it as one of the best hotels in Lima.[43] Nowadays, the Hotel Bolivar continues to offer the cocktail in its "El Bolivarcito" bar,[44] while the Country Club Lima Hotel offers the drink in its "English Bar" saloon.[45]

Preparation and variants

The pisco sour has three different methods of preparation. The Peruvian pisco sour cocktail is made by mixing Peruvian pisco with Key lime juice, simple syrup, egg white, Angostura bitters (for garnish), and ice cubes.[1] The Chilean pisco sour cocktail is made by mixing Chilean Pisco with limón de Pica juice, powdered sugar, and ice cubes.[46] Daniel Joelson, a food writer, and critic, contends that the major difference between both pisco sour versions "is that Peruvians generally include egg whites, while Chileans do not."[47] The version from the International Bartenders Association, which lists the pisco sour among its "New Era Drinks," is similar to the Peruvian version, but with the difference that it uses lemon juice, instead of lime juice, and does not distinguish between the two different types of pisco.[48]

Considerable differences exist in the pisco used in the cocktails. According to food and wine expert Mark Spivak, the difference is in how both beverages are produced; whereas "Chilean pisco is mass-produced," the Peruvian version "is made in small batches."[49] Cocktail historian Andrew Bohrer focuses his comparison on taste, claiming that "[i]n Peru, pisco is made in a pot still, distilled to proof, and un-aged; it is very similar to grappa. In Chile, pisco is made in a column still and aged in wood; it is similar to a very light cognac."[50] Chilean oenologist Patricio Tapia adds that while Chilean pisco producers usually mix vine stocks, Peruvian producers have specific pisco types that use the aromatic qualities of vines such as Yellow Muscat and Italia. Tapia concludes this is why Peruvian pisco bottles denote their vintage year and the Chilean versions do not.[51]

Variations of the pisco sour exist in Peru, Bolivia, and Chile. There are adaptations of the cocktail in Peru using fruits such as maracuya (commonly known as passion fruit), aguaymanto, and apples, or traditional ingredients such as the coca leaf.[52] Lima's Hotel Bolivar serves a larger version of the cocktail, named pisco sour catedral, invented for hurried guests arriving from the nearby Catholic cathedral.[53] In Chile, variants include the ají Sour (with a spicy green chili), mango sour (with mango juice), and sour de campo (with ginger and honey). In Bolivia, the Yunqueño variant (from its Yungas region) replaces the lime with orange juice.[54]

Cocktails similar to the pisco sour exist in Chile and Peru. The Chilean piscola is made by mixing pisco with cola.[46] The Algarrobina cocktail, popular in northern Peru, is made from pisco, condensed milk, and sap from the Peruvian algarroba tree.[55] Other Peruvian pisco-based cocktails include the chilcano (made with pisco and ginger ale) and the capitán (made with pisco and vermouth).[42] Another similar cocktail, from the United States, is the Californian pisco punch, originally made with Peruvian pisco, pineapples, and lemon.[56]

Popularity

Duggan McDonnell describes the pisco sour as "Latin America's most elegant cocktail, frothy, balanced, bright yet rich," adding that "Barkeeps throughout Northern California will attest that they have shaken many a Pisco sour. It is the egg white cocktail of choice and an absolutely beloved one by most."[57] Australian journalist Kate Schneider writes that the pisco sour "has become so famous that there is an International Pisco Sour Day celebration on the first Saturday in February every year, as well as a Facebook page with more than 600,000 likes."[58] According to Chilean entrepreneur Rolando Hinrichs Oyarce, owner of a restaurant-bar in Spain, "The pisco sour is highly international, just like Cebiche, and so they are not too unknown" (Spanish: "El pisco sour es bastante internacional, al igual que el cebiche, por lo tanto no son tan desconocidos").[59] In 2003, Peru created the "Día Nacional del Pisco Sour" (National Pisco Sour Day), an official government holiday celebrated on the first Saturday of February.[60][E] During the 2008 APEC Economic Leaders' Meeting, Peru promoted its pisco sour with widespread acceptance. The cocktail was reportedly the preferred drink of the attendees, mostly leaders, businessmen, and delegates.[63]

Origin dispute

Victor Vaughen Morris is considered by most historians to be the inventor of the pisco sour cocktail.[28] Nonetheless, the cocktail's traditional origin story is complicated with findings that suggest otherwise. Based on the recipe from the 1903 Peruvian cookbook Manual de Cocina a la Criolla, researcher Nico Vera considers that "the origin of the Pisco Sour may be a traditional creole cocktail made in Lima over 100 years ago."[64] Based on the clipping from the 1921 West Coast Leader news article, McDonnell considers it possible that the pisco sour may have actually originated in San Francisco, considering additionally that during this time the city experienced a "burst of cocktail creativity," the whiskey sour cocktail "was plentiful and ubiquitous," and "the fact that Pisco was heralded as a special spirit" in the city.[19]

In defense of Morris, journalist Rick Vecchio considers that "even if there was something very similar and pre-existing" to Morris' pisco cocktail, it should not be doubted that he "was the first to serve, promote and perfect what today is known as the Pisco Sour."[64] McDonnell also considers that, regardless of its exact origin, the pisco sour "belongs to Peru."[20] According to culture writer Saxon Baird, a bust in honor of Morris stands in Lima's Santiago de Surco district "as a testament to Morris' contribution to modern Peruvian culture and the country he called home for more than half his life."[22]

Despite this, an ongoing dispute exists between Chile and Peru over the origin of the pisco sour.[65] In Chile, a local story developed in the 1980s attributing the invention of the pisco sour to Elliot Stubb, an English steward from a sailing ship named Sunshine. Chilean folklorist and historian Oreste Plath contributed to the legend's propagation by writing that, according to the Peruvian newspaper El Comercio de Iquique, in 1872, after obtaining leave to disembark, Stubb opened a bar in the then-Peruvian port of Iquique and invented the pisco sour while experimenting with drinks.[29][66][F] Nevertheless, researcher Toro-Lira argues that the story was refuted after it was discovered El Comercio de Iquique was actually referring to the invention of the whiskey sour.[29] The story of Elliot Stubb and his alleged invention of the whiskey sour in Iquique is also found in a 1962 publication by the University of Cuyo, Argentina. An excerpt from the newspaper's story has Elliot Stubb stating, "From now on ... this shall be my drink of battle, my favorite drink, and it shall be named Whisky Sour" (in Spanish: "En adelante dijo Elliot — éste será mi trago de batalla, — mi trago favorito —, y se llamará Whisky Sour.").[67]

Some pisco producers have expressed that the ongoing controversy between Chile and Peru helps promote interest in the liquor and its geographical indication dispute.[68]

American celebrity chef Anthony Bourdain drew attention to the cocktail when, in an episode of his Travel Channel program No Reservations, he drank a pisco sour in Valparaíso, Chile, and said: "that's good, but ... next time, I'll have a beer." The broadcaster Radio Programas del Perú reported that Jorge López Sotomayor, the episode's Chilean producer and Bourdain's travel partner in Chile, said Bourdain found the pisco sour he drank in Valparaíso boring and not worth the effort (in Spanish: "A mí me dijo que el pisco sour lo encontró aburrido y que no valía la pena."). Lopez added that Bourdain had recently arrived from Peru, where he drank several pisco sours which he thought tasted better than the Chilean version.[69]

In 2010, Mexican singer-songwriter Aleks Syntek humorously posted on Twitter that the pisco sour is Chilean and, after receiving critical responses to his statement, apologized and mentioned he was only joking.[70] Mexican television host and comedian Adal Ramones also joked about pisco sour, about the 2009 Chile–Peru espionage scandal, on November 17, 2009. Ramones, a fan of Peruvian Pisco, when asked about the espionage, asked what Chileans were spying on in Peru, suggesting it might be how to make a pisco sour (in Spanish: "¿Qué quieren espiar los chilenos? ¿Cómo hacer pisco sour?").[71] In 2017, when told pisco sour was "totally Chilean" by an interviewer at a Chilean radio station, British musician Ed Sheeran commented that he preferred the Peruvian pisco sour.[72]

See also

Explanatory notes

- ^ Despite the pisco sour being predominantly emblematic along the Pacific coast of Peru and Chile, Casey calls it a "classic South American drink" and Bovis says it is "a hallmark South American cocktail."[3][4]

- ^ Peru considers that the name "pisco" should be of exclusive geographical indication to the aguardiente produced in designated regions within its territory.[5] Chile also has designated regions of pisco production within its territory, but claims exclusivity of the liquor under the name "Pisco Chile."[5]

- ^ In colonial Chile the word "pisco" was mostly used by the lower social strata and is rarely found in the upper class speech of the epoch.[14]

- ^ The image reads: "Have You Registered in Morris' Bar LIMA? You will find the names and addresses of many of your friends in this register. It is at the free disposition of all English-speaking persons who reside in or who pass through Lima. MORRIS' BAR at CALLE BOZA, 836, LIMA, Peru, has been noted for many years for its "pisco sours" and its reputation for "Legitimate Liquors." The Bar Register has become a veritable "Who's Who" among West Coast travellers and many friends have been located through the information within its pages."

- ^ The "Día Nacional del Pisco Sour" holiday was initially set for celebration on February 8.[60] However, after the Chilean Pisco industry set its non-government sponsored "Día de la Piscola" (Piscola Day) also for celebration on February 8,[61][62] Peru responded by changing its pisco sour holiday to its current date.[60]

- ^ Iquique was later occupied by Chile during the War of the Pacific and annexed by that country in 1883.

Citations

- ^ a b c d Kosmas & Zaric 2010, p. 115.

- ^ a b See:

- DeGroff 2008, Pisco Sour

- Duecy 2013, Pisco Sour

- Kosmas & Zaric 2010, p. 115

- Parsons 2011, p. 143

- Roque 2013, Pisco Sour

- ^ Casey 2009, p. 89.

- ^ Bovis 2012, Pisco Sour.

- ^ a b Acosta González, Martín (22 May 2012). "Qué países reconocen el pisco como peruano y cuáles como chileno". El Comercio (in Spanish). Empresa Editora El Comercio. Archived from the original on 27 March 2017. Retrieved 5 October 2015.

- ^ Regan 2003, p. 159.

- ^ Blouet & Blouet 2009, p. 318.

- ^ "Pisco". Diccionario de la Lengua Española (in Spanish) (Vigésima Segunda Edición ed.). Archived from the original on 4 July 2015. Retrieved 3 July 2015.

- ^ "Pisco". Concise Oxford Dictionary. WordReference.com. Archived from the original on 5 July 2015. Retrieved 3 July 2015.

- ^ Franco 1991, p. 20.

- ^ a b Harrel, Courtney (2009). "Pisco Por La Razón o La Fuerza" (in Spanish). School for International Training. pp. 14–15. Archived from the original on 2017-02-02. Retrieved 2012-04-01.

- ^ a b Lacoste, Pablo (2004). "La vid y el vino en América del Sur: El desplazamiento de los polos vitivinícolas (siglos XVI al XX)" [The vine and wine in South America: The shifting of the winemaking poles (XVI to XX)]. Universum (in Spanish). 19 (2): 62–93. doi:10.4067/S0718-23762004000200005.

- ^ a b Pozo 2004, pp. 24–34.

- ^ a b c Cortés Olivares, Hernán F (2005). "El origen, producción y comercio del pisco chileno, 1546–1931" [The origin, production and trade of Chilean pisco, 1546–1931]. Universum (in Spanish). 20 (2): 42–81. doi:10.4067/S0718-23762005000200005.

- ^ Huertas Vallejos, Lorenzo (2004). "Historia de la producción de vinos y piscos en el Perú" [History of the production of wine and pisco in Peru]. Universum (in Spanish). 19 (2): 44–61. doi:10.4067/S0718-23762004000200004.

- ^ "Aguardiente". Diccionario de la Lengua Española (in Spanish) (Vigésima Segunda Edición ed.). Archived from the original on 5 July 2015. Retrieved 3 July 2015.

- ^ Foley 2011, p. "Pisco Porton Brandy Recipes".

- ^ Pilar Lazo Rivera, Carmen del (2009). "Pisco Sour del Perú" (PDF) (in Spanish). Pediatraperu.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 3 July 2015.

- ^ a b c McDonnell 2015, p. 171.

- ^ a b McDonnell 2015, p. 172.

- ^ a b c d e f g Perich, Tatiana (5 February 2015). "Les Presentamos a Mario Bruiget, el Peruano Coinventor del pisco sour". El Comercio (in Spanish). Empresa Editora El Comercio. Archived from the original on 3 July 2015. Retrieved 2 July 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Baird, Saxon (1 March 2018). "How a Mining Boom Led a Mormon Florist to Invent the Pisco Sour". Atlas Obscura. Archived from the original on 16 January 2021. Retrieved 18 June 2021.

- ^ Karydes, Megy (11 December 2009). "Celebrate The Peruvian Cocktail On World Pisco Sour Day, Feb 7". Forbes. Archived from the original on 4 July 2015. Retrieved 3 July 2015.

- ^ Vial Correa 1981, p. 352.

- ^ DeGroff 2008, Pisco Sour.

- ^ See:

- Kosmas & Zaric 2010, p. 115

- Parsons 2011, p. 143

- ^ a b "Peruanos Celebran el "Día del Pisco Sour" con Degustaciones y Fiestas" (in Spanish). Emol.com. Agence France-Presse. 5 February 2011. Archived from the original on 2 July 2015. Retrieved 3 July 2015.

- ^ a b c Duecy 2013, Pisco Sour.

- ^ a b c d e f g Toro-Lira, Guillermo L. (11 December 2009). "Clarifying the Legends from the History of the pisco sour". Piscopunch.com. Archived from the original on 21 February 2015. Retrieved 2 July 2015. (A re-print and modern version of the article; archived from the original on 20 June 2021)

- ^ Jiménez Morato 2012, Julio Ramon Ribeyro: Pisco Sour.

- ^ a b Coloma Porcari, César (2005). "La Verdadera Historia del Pisco Sour". Revista Cultural de Lima (in Spanish). pp. 72–73. Archived from the original on 13 July 2015. Retrieved 3 July 2015.

- ^ Parsons 2011, p. 143.

- ^ Toro-Lira, Guillermo L. (25 April 2020). "Análisis del registro de firmas del Morris' Bar (1916–1929)" (in Spanish). Piscopunch.com. Archived from the original on 5 February 2021. Retrieved 20 June 2021.

- ^ a b Sánchez 1969, p. 249.

- ^ Toro-Lira, Guillermo L. (6 February 2009). "La vida y pasiones de Víctor V. Morris, creador del Pisco Sour – 2nda parte" (in Spanish). Piscopunch.com. Archived from the original on 16 May 2021. Retrieved 16 May 2021.

- ^ Bergeron 1972, p. 398.

- ^ Regan 2003, p. 317.

- ^ a b Jiménez, Beatriz (6 February 2011). "La Fiesta del Pisco Sour". El Mundo (in Spanish). Spain. Archived from the original on 3 July 2015. Retrieved 2 July 2015.

- ^ Hanson 1943, p. 34.

- ^ Slater, Julia (9 February 2010). "Peru Toasts Pisco Boom on Annual Cocktail Day". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 26 September 2017. Retrieved 2 July 2015.

- ^ Milland 1974, p. 207.

- ^ a b Pan American World Airways, Inc. 1978, p. 862.

- ^ Córdova Claure, Ted (1984). "La Calcutización de las Ciudades Latinoamericanas" (PDF). Nueva Sociedad (in Spanish) (72): 49–56. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-07-06. Retrieved 2012-03-14.

- ^ "El Bolivarcito". GranHotelBolivar.com. Archived from the original on 8 July 2015. Retrieved 2 July 2015.

- ^ "English Bar". HotelCountry.com. 2013. Archived from the original on 3 July 2015. Retrieved 2 July 2015.

- ^ a b Castillo-Feliú 2000, p. 79.

- ^ Joelson, Daniel (Winter 2004). "The Pisco Wars". Gastronomica: The Journal of Food and Culture. 4 (1): 6–8. doi:10.1525/gfc.2004.4.1.1.

- ^ "New Era Drinks". IBA-World.com. International Bartenders Association. Archived from the original on 28 October 2015. Retrieved 28 October 2015.

- ^ Spivak, Mark. "Pour – Pisco Fever". PalmBeachIllustrated.com. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 3 July 2015.

- ^ Bohrer 2012, Friendship Test.

- ^ "Entrevista: Patricio Tapia – Periodista Chileno Especializado en Vinos" (in Spanish). PiscoSour.com. 2012. Archived from the original on 12 December 2013. Retrieved 3 July 2015.

- ^ "Recetas" (in Spanish). PiscoSour.com. 2012. Archived from the original on 2012-08-26. Retrieved 2012-12-03.

- ^ "Pisco sour catedral y el Gran Hotel Bolívar" (in Spanish). Elpisco.es. 9 February 0521. Archived from the original on 2021-06-24. Retrieved 2021-06-22.

- ^ Baez Kijac 2003, p. 35.

- ^ Albala 2011, p. 266.

- ^ See:

- Kosmas & Zaric 2010, p. 116

- Sandham 2012, p. 251

- ^ McDonnell 2015, p. 170.

- ^ Schneider, Kate (March 27, 2012). "Kate Schneider Appreciates the Bitter Side of Life with South American Drink Pisco Sour". News.com.au. Archived from the original on 23 June 2015. Retrieved 2 July 2015.

- ^ Alías, Marina (April 9, 2006). "Sours chilenos irrumpen en barrio mítico de Madrid". El Mercurio, Revista del Domingo (in Spanish). Santiago.

- ^ a b c "Chile Celebra Hoy el Día de la Piscola". El Comercio (in Spanish). Empresa Editora El Comercio. 8 February 2011. Archived from the original on 3 July 2015. Retrieved 3 July 2015.

- ^ Ruiz, Carlos (8 February 2011). "Hoy es el Día de la Piscola: Chilenos Celebran Uno de dus Tragos Típicos" (in Spanish). ElObservatodo.cl. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 3 July 2015.

- ^ Castro, Felipe (8 February 2011). "Día de la Piscola: A Tomar Combinados" (in Spanish). LaNacion.cl. Archived from the original on 4 July 2015. Retrieved 3 July 2015.

- ^ "APEC visitors enjoyed Peruvian pisco sour". Andina.com. 24 November 2008. Archived from the original on 3 July 2015. Retrieved 2 July 2015.

- ^ a b Vecchio, Rick (23 January 2014). "Beguiling History of the Pisco Sour, With a Twist". Peruvian Times. Andean Air Mail & Peruvian Times. Archived from the original on 14 June 2021. Retrieved 18 June 2021.

- ^ Sandham 2012, p. 251.

- ^ Plath 1981, p. 106.

- ^ "Nuevo 'round' en la larga pelea de Perú y Chile por el pisco". CNN en Español (in Spanish). CNN. 30 May 2017. Archived from the original on 15 May 2021. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- ^ "Chef Anthony Bourdain: Pisco Sour Chileno es Aburrido y No Vale la Pena". Radio Programas del Perú (in Spanish). Grupo RPP. 18 July 2009. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 2 July 2015.

- ^ "Alex Syntek Dice Que el pisco sour y La Tigresa del Oriente Son Chilenos". Radio Programas del Perú (in Spanish). Grupo RPP. 19 November 2010. Archived from the original on 24 November 2010. Retrieved 2 July 2015.

- ^ "Adal Ramones: "¿Qué Quieren Espiar los Chilenos? ¿Cómo Hacer Pisco Sour?"". El Comercio (in Spanish). Empresa Editora El Comercio. 17 November 2009. Archived from the original on 3 July 2015. Retrieved 2 July 2015.

- ^ "Ed Sheeran cree que el pisco peruano es mejor que el chileno… ¿y tú?". CNN en Español (in Spanish). CNN. 19 May 2017. Archived from the original on 15 May 2021. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

General and cited references

- Albala, Ken, ed. (2011). Food Cultures of the World Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-37627-6.

- Baez Kijac, Maria (2003). The South American Table. Boston, Massachusetts: The Harvard Common Press. ISBN 1-55832-248-5.

- Bergeron, Victor Jules (1972). Trader Vic's Bartenders Guide. New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc. ISBN 978-0385068055.

- Blouet, Brian; Blouet, Olwyn (2009). Latin America and the Caribbean. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-38773-3.

- Bohrer, Andrew (2012). The Best Shots You've Never Tried. Avon, Massachusetts: Adams Media. ISBN 978-1-4405-3879-7.

- Bovis, Natalie (2012). Edible Cocktails. New York: F+W Media, Inc. ISBN 978-1-4405-3368-6.

- Casey, Kathy (2009). Sips and Apps. San Francisco, California: Chronicle Books LLC. ISBN 978-0-8118-7823-4.

- Castillo-Feliú, Guillermo I. (2000). Culture and Customs of Chile. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-313-30783-0.

- DeGroff, Dale (2008). The Essential Cocktail: The Art of Mixing Perfect Drinks. New York: Random House Digital. ISBN 978-0-307-40573-9.

- Duecy, Erica (2013). Storied Sips: Evocative Cocktails for Everyday Escapes. New York: Random House LLC. ISBN 978-0-375-42622-3.

- Facultad de Filosofía y Letras (1962). Anales del Instituto de Lingüística, Volúmenes 8–9. Mendoza, Argentina: Universidad Nacional de Cuyo.

- Foley, Ray (2011). The Ultimate Little Cocktail Book. Naperville, Illinois: Sourcebooks, Inc. ISBN 978-1-4022-5410-9.

- Franco, César (1991). Celebración del Pisco. Lima: Centro de Estudios para el Desarrollo y la Participación.

- Hanson, Earl Parker (1943). The New World Guides to the Latin American Republics. New York: Duell, Sloan and Pearce.

- Jiménez Morato, Antonio (2012). Mezclados y Agitados (in Spanish). Barcelona: Debolsillo. ISBN 978-84-9032-356-4.

- Kosmas, Jason; Zaric, Dushan (2010). Speakeasy. New York: Random House Digital. ISBN 978-1-58008-253-2.

- McDonnell, Duggan (2015). Drinking the Devil's Acre: A Love Letter from San Francisco and her Cocktails. San Francisco, CA: Chronicle Books LLC. ISBN 978-1-4521-4062-9.

- Milland, Ray (1974). Wide-Eyed in Babylon. New York: Morrow. ISBN 0-688-00257-9.

- Pan American World Airways, Inc. (1978). Pan Am's World Guide: The Encyclopedia of Travel. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 9780070484184.

- Parsons, Brad Thomas (2011). Bitters. New York: Random House Digital. ISBN 978-1-60774-072-8.

- Plath, Oreste (1981). Folklore Lingüístico Chileno: Paremiología (in Spanish). Santiago, Chile: Editorial Nascimento. ISBN 956-258-052-0.

- Pozo, José del (2004). Historia del Vino Chileno (in Spanish). Santiago: Editorial Universitaria. ISBN 956-11-1735-5.

- Regan, Gary (2003). The Joy of Mixology, The Consummate Guide to the Bartender's Craft. New York: Clarkson Potter. ISBN 0-609-60884-3.

- Roque, Raquel (2013). Cocina Latina: El sabor del Mundo Latino (in Spanish). New York: C.A. Press. ISBN 978-1-101-55290-2.

- Sánchez, Luis Alberto (1969). Testimonio Personal: Memorias de un Peruano del Siglo XX (in Spanish). Lima: Mosca Azul Editores.

- Sandham, Tom (2012). World's Best Cocktails. Lions Bay, Canada: Fair Winds Press. ISBN 978-1-59233-527-5.

- Vial Correa, Gonzalo (1981). Historia de Chile, 1891–1973: La Dictadura de Ibáñez, 1925–1931 (in Spanish). Santiago: Editorial Santillana del Pacífico. ISBN 956-12-1201-3.

External links

- Piscosour.com – Website about pisco sour.

- Liquor.com – Detailed pisco sour preparation guide.

- Food Network – Video preparation of a pisco sour version.