Schindler's List: Difference between revisions

Denisarona (talk | contribs) m Reverted edits by 108.234.225.38 (talk) to last version by O.Koslowski |

|||

| Line 31: | Line 31: | ||

==Plot== |

==Plot== |

||

This story is a piece of shit with all the weiny jews those pieces of shliffen if only they luived as me one day they would feal real pain |

|||

--Sincierly hitler |

|||

In 1939, the Germans move [[History of the Jews in Poland|Polish Jews]] to the [[Kraków Ghetto]] as [[World War II]] begins. [[Oskar Schindler]] ([[Liam Neeson]]), an ethnic German businessman from [[Moravia]], arrives in the city hoping to make a fortune as a war profiteer. Schindler, a member of the [[Nazi Party]], lavishes bribes upon [[Wehrmacht]] and [[Schutzstaffel|SS]] officials. Sponsored by the military, Schindler acquires a factory for the production of army mess kits. Not knowing much about how to run such an enterprise, he gains a collaborator, [[Itzhak Stern]] ([[Ben Kingsley]]), an official of Krakow's ''[[Judenrat]]'' (Jewish Council) who has contacts with the Jewish business community and the [[black market]]ers inside the ghetto. The Jewish businessmen lend Schindler money in return for a share of products produced. Opening the factory, Schindler pleases the Nazis and enjoys newfound wealth and status as "Herr Direktor", while Stern handles administration. Schindler hires Jewish Poles instead of Catholic Poles because they cost less. Workers in Schindler's factory are allowed outside the ghetto, and Stern ensures that as many people as possible are deemed "essential" to the German war effort, saving them from being transported to concentration camps or killed. |

In 1939, the Germans move [[History of the Jews in Poland|Polish Jews]] to the [[Kraków Ghetto]] as [[World War II]] begins. [[Oskar Schindler]] ([[Liam Neeson]]), an ethnic German businessman from [[Moravia]], arrives in the city hoping to make a fortune as a war profiteer. Schindler, a member of the [[Nazi Party]], lavishes bribes upon [[Wehrmacht]] and [[Schutzstaffel|SS]] officials. Sponsored by the military, Schindler acquires a factory for the production of army mess kits. Not knowing much about how to run such an enterprise, he gains a collaborator, [[Itzhak Stern]] ([[Ben Kingsley]]), an official of Krakow's ''[[Judenrat]]'' (Jewish Council) who has contacts with the Jewish business community and the [[black market]]ers inside the ghetto. The Jewish businessmen lend Schindler money in return for a share of products produced. Opening the factory, Schindler pleases the Nazis and enjoys newfound wealth and status as "Herr Direktor", while Stern handles administration. Schindler hires Jewish Poles instead of Catholic Poles because they cost less. Workers in Schindler's factory are allowed outside the ghetto, and Stern ensures that as many people as possible are deemed "essential" to the German war effort, saving them from being transported to concentration camps or killed. |

||

Revision as of 18:59, 10 May 2013

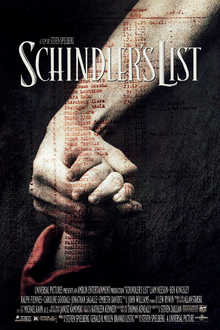

| Schindler's List | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Steven Spielberg |

| Screenplay by | Steven Zaillian |

| Produced by | Steven Spielberg Gerald R. Molen Branko Lustig |

| Starring | Liam Neeson Ben Kingsley Ralph Fiennes Caroline Goodall Jonathan Sagall Embeth Davidtz |

| Cinematography | Janusz Kamiński |

| Edited by | Michael Kahn |

| Music by | John Williams |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Universal Pictures |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 195 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Languages | English German Hebrew Polish French |

| Budget | $22 million[1] |

| Box office | $321,306,305 |

Schindler's List is a 1993 American epic drama film directed and co-produced by Steven Spielberg and scripted by Steven Zaillian. It is based on the novel Schindler's Ark by Thomas Keneally, an Australian novelist. The film tells the story of Oskar Schindler, a German businessman who saved the lives of more than a thousand mostly Polish-Jewish refugees during the Holocaust by employing them in his factories. It stars Liam Neeson as Schindler, Ralph Fiennes as Schutzstaffel (SS)-officer Amon Göth, and Ben Kingsley as Schindler's Jewish accountant Itzhak Stern. John Williams composed the score.

Ideas for a film about the Schindlerjuden were proposed as early as 1963. Poldek Pfefferberg, one of the Schindlerjuden, made it his life's mission to tell the story of Schindler. When executive Sid Sheinberg sent a review of Schindler's Ark to Spielberg, the director was fascinated by the book. He eventually expressed enough interest for Universal Pictures to buy the rights to the novel. However, he was unsure about his own maturity about making a film about the Holocaust. Spielberg tried to pass on the projects to several other directors before finally deciding to direct the film himself after hearing of the various Holocaust denials.

Filming took place in Poland over the course of 72 days, in Kraków. Spielberg shot the film like a documentary, and decided not to use storyboards while shooting Schindler's List. Cinematographer Janusz Kamiński wanted to give a timeless sense to the film. Production designer Allan Starski made the sets darker or lighter than the people in the scenes, so they would not blend. The costumes had to be distinguished from skin tones or colors being used for the sets. In composing the score to Schindler's List, Williams hired violinist Itzhak Perlman to perform the film's main theme.

Schindler's List premiered on 30 November 1993 in Washington, D.C. and it was released on 15 December 1993 in the United States. Regarded as one of the greatest films ever made, it was a box office success and recipient of seven Academy Awards, including Best Picture, Best Director, and Best Original Score, as well as numerous other awards (seven BAFTAs, three Golden Globes). In 2007, the American Film Institute ranked the film 8th on its list of the 100 best American films of all time (up one position from its 9th place listing on the 1998 list).

Plot

This story is a piece of shit with all the weiny jews those pieces of shliffen if only they luived as me one day they would feal real pain --Sincierly hitler

In 1939, the Germans move Polish Jews to the Kraków Ghetto as World War II begins. Oskar Schindler (Liam Neeson), an ethnic German businessman from Moravia, arrives in the city hoping to make a fortune as a war profiteer. Schindler, a member of the Nazi Party, lavishes bribes upon Wehrmacht and SS officials. Sponsored by the military, Schindler acquires a factory for the production of army mess kits. Not knowing much about how to run such an enterprise, he gains a collaborator, Itzhak Stern (Ben Kingsley), an official of Krakow's Judenrat (Jewish Council) who has contacts with the Jewish business community and the black marketers inside the ghetto. The Jewish businessmen lend Schindler money in return for a share of products produced. Opening the factory, Schindler pleases the Nazis and enjoys newfound wealth and status as "Herr Direktor", while Stern handles administration. Schindler hires Jewish Poles instead of Catholic Poles because they cost less. Workers in Schindler's factory are allowed outside the ghetto, and Stern ensures that as many people as possible are deemed "essential" to the German war effort, saving them from being transported to concentration camps or killed.

SS-Lieutenant (Untersturmführer) Amon Goeth (Ralph Fiennes) arrives in Kraków to oversee construction of the Płaszów concentration camp. Once the camp is completed, he orders the liquidation of the ghetto and Operation Reinhard in Kraków begins, with hundreds of troops emptying the cramped rooms and arbitrarily murdering anyone who is uncooperative, elderly or infirm. Schindler watches the massacre and is profoundly affected. He nevertheless is careful to befriend Goeth and, through Stern's attention to bribery, Schindler continues enjoying SS support. Schindler bribes Goeth into allowing him to build a sub-camp for his workers, so that he can keep his factory running smoothly and protect them. As time passes, Schindler tries to save as many lives as he can. As the war shifts, Goeth is ordered to ship the remaining Jews to the Auschwitz concentration camp.

Schindler prepares to leave Kraków with his fortune. He finds himself unable to do so, however, and prevails upon Goeth to allow him to keep his workers so he can move them to a factory in his old home of Zwittau-Brinnlitz, away from the Final Solution. Goeth charges a massive bribe for each worker. Schindler and Stern assemble a list of workers to be kept off the trains to Auschwitz.

"Schindler's List" comprises these "skilled" inmates, and for many of those in Płaszów, being included means the difference between life and death. Almost all of the people on Schindler's list arrive safely at the new site. The train carrying the women is accidentally redirected to Auschwitz. Schindler bribes the camp commander, Rudolf Höß, with a cache of diamonds in exchange for releasing the women to Brinnlitz. Once the women arrive, Schindler institutes firm controls on the SS guards assigned to the factory, forbidding them to enter the production areas. He encourages the Jews to observe the Sabbath. To keep his workers alive, he spends much of his fortune bribing Nazi officials and buying shells from other companies; he never produces working shells during the seven months his factory operates. He runs out of money just as the Wehrmacht surrenders, ending the war in Europe.

8 May 1945, the workers and Germans listen to British Prime Minister Winston Churchill's speech of the Unconditional Surrender of Germany to the Allies. As a Nazi Party member and a self-described "profiteer of slave labour", in 1945, Schindler must flee the advancing Red Army. Although the SS guards have been ordered to kill the Jews, Schindler persuades them to return to their families as men, not murderers. In the aftermath, he packs a car in the night and bids farewell to his workers. They give him a letter explaining he is not a criminal to them, together with a ring secretly made from a worker's gold dental bridge and engraved with a Talmudic quotation, "Whoever saves one life saves the world entire". Schindler is touched but deeply ashamed as he leaves, feeling he could have done more to save lives, such as selling his car and Golden Party Badge.

The Schindler Jews are awakened by sunlight the next morning. A Soviet dragoon announces that they have been liberated by the Red Army. The Jews walk to a nearby town in search of food.

After a few scenes depicting post-war events such as the execution of Amon Goeth and a summary of what happened to Schindler in his later years, the Jews are shown walking to the nearby town. The black-and-white frame changes to one in colour of present-day Schindler Jews at Schindler's grave site in Jerusalem, where he wanted to be interred.[2] A procession of now-elderly Jews who worked in Schindler's factory set stones on his grave—a traditional Jewish custom denoting gratitude to the deceased. The actors portraying the major characters walk with them. Ben Kingsley is accompanied by the widow of Itzhak Stern, who died in 1969. A title card reveals that at the time of the film's release, there were fewer than 4,000 Jews left alive in Poland, but more than 6,000 descendants of the Schindler Jews throughout the world. In the final scene, Liam Neeson places a pair of roses on the grave and stands over it.

Cast

Main

- Liam Neeson as Oskar Schindler, a German Nazi businessman who saves the lives of over 1,100 Jews by employing them in his factory.

- Ben Kingsley as Itzhak Stern, Schindler's accountant and business partner.

- Ralph Fiennes as Amon Goeth, an SS officer assigned to build and run the Płaszów concentration camp, and is befriended by Schindler, though he grows steadily suspicious of Schindler's true aims as the film progresses. He is sadistic and psychopathic, frequently murdering his prisoners for fun.

- Embeth Davidtz as Helen Hirsch, a young Jewish woman works as Goeth's housekeeper. She is attractive in his eyes.

- Caroline Goodall as Emilie Schindler, Schindler's wife.

- Jonathan Sagall as Poldek Pfefferberg, a young man who survived with his wife and provides goods to Schindler from the black market.

Secondary

- Mark Ivanir as Marcel Goldberg.

- Andrzej Seweryn as Julian Scherner.

- Jerzy Nowak as Investor.

- Norbert Weisser as Albert Hujar.

- Anna Mucha as Danka Dresner.

- Hans-Michael Rehberg as Rudolf Höss

- Daniel Del Ponte as Josef Mengele, the doctor in Auschwitz

Production

Development

Poldek Pfefferberg was one of the Schindlerjuden, and made it his life's mission to tell the story of his savior. Pfefferberg attempted to produce a biopic of Oskar Schindler with MGM in 1963,[3] with Howard Koch writing,[4] but the deal fell through. In 1982, Thomas Keneally published Schindler's Ark, which he wrote after he met Pfefferberg. MCA president Sid Sheinberg sent director Steven Spielberg a New York Times review of the book. Spielberg was astounded by the story of Oskar Schindler, jokingly asking if it was true. Spielberg "was drawn to the paradoxical nature of [Schindler]... It was about a Nazi saving Jews... What would drive a man like this to suddenly take everything he had earned and put it all in the service of saving these lives?" Spielberg expressed enough interest for Universal Pictures to buy the rights to the novel, and in early 1983 Spielberg met with Pfefferberg. Pfefferberg asked Spielberg, "Please, when are you starting?" Spielberg replied, "Ten years from now."[3] (In the end credits of the film, Pfefferberg is credited as an adviser, under the name "Leopold Page.")

Spielberg was unsure of his own maturity in making a film about the Holocaust, and the project remained "on [his] guilty conscience". Spielberg tried to pass the project to director Roman Polanski, who turned it down. Polanski's mother was killed at Auschwitz,[5] and he had lived in and survived the Kraków Ghetto. Polanski eventually directed his own Holocaust drama, The Pianist, in 2002. Spielberg also offered the film to Sydney Pollack,[4] and Martin Scorsese, who was attached to direct Schindler's List in 1988. However, Spielberg was unsure of letting Scorsese direct the film, as "I'd given away a chance to do something for my children and family about the Holocaust." Spielberg offered him the chance to direct the 1991 remake of Cape Fear instead.[4] Billy Wilder expressed interest in directing the film "as a memorial to most of [his] family, who went to Auschwitz."

Spielberg finally decided to direct the film after hearing of the various Holocaust deniers.[3] With the rise of neo-Nazism after the fall of the Berlin Wall, he worried that people were too accepting of intolerance, as they were in the 1930s. In addition, Spielberg was becoming more involved with his Jewish heritage while raising his children.[6] Sid Sheinberg greenlit the film on one condition: that Spielberg make Jurassic Park first. Spielberg later said, "He knew that once I had directed Schindler I wouldn't be able to do Jurassic Park."[4]

In 1983, Thomas Keneally was hired to adapt his book, and he turned in a 220-page script. Keneally focused on Schindler's numerous relationships, and admitted he did not compress the story enough. Spielberg hired Kurt Luedtke, who had adapted the screenplay of Out of Africa, to write the next draft. Luedtke gave up almost four years later, as he found Schindler's change of heart too unbelievable. During his time as director, Scorsese hired Steven Zaillian to write the script. When he was handed back the project, Spielberg found Zaillian's 115-page draft too short, and asked him to extend it to 195 pages. Spielberg wanted to focus on the Jews in the story. He extended the ghetto liquidation sequence, as he "felt very strongly that the sequence had to be almost unwatchable." He wanted Schindler's transition to be gradual and ambiguous, and not "some kind of explosive catharsis that would turn this into The Great Escape."[4]

Casting

Liam Neeson auditioned as Oskar Schindler early in the casting process and was cast in December 1992, after Spielberg saw him perform in Anna Christie on Broadway.[4] Warren Beatty participated in a script reading, but Spielberg was concerned that he could not disguise his accent and that he would bring "movie star baggage".[7] Kevin Costner and Mel Gibson expressed interest in portraying Schindler.[4] Neeson felt "[Schindler] enjoyed fookin' [sic] with the Nazis. In Keneally's book it says he was regarded as a kind of a buffoon by them... if the Nazis were New Yorkers, he was from Arkansas. They don't quite take him seriously, and he used that to full effect."[8] To prepare for the role, Neeson was sent tapes of Time Warner CEO Steve Ross, who had a charisma that Spielberg compared to Schindler's.[9]

Ralph Fiennes was cast as Amon Goeth after Spielberg viewed his performances in A Dangerous Man: Lawrence After Arabia and Emily Brontë's Wuthering Heights. Spielberg said of Fiennes' audition that "I saw sexual evil. It is all about subtlety: there were moments of kindness that would move across his eyes and then instantly run cold." Fiennes put on 28 lbs to play the role. He watched historic newsreels and talked to Holocaust survivors who knew Amon Göth. In portraying him, Fiennes said "I got close to his pain. Inside him is a fractured, miserable human being. I feel split about him, sorry for him. He's like some dirty, battered doll I was given and that I came to feel peculiarly attached to." Fiennes looked so much like Amon Göth in costume that when Mila Pfefferberg, a survivor of the events, met him she trembled with fear.[10]

Overall, there are 126 speaking parts in the film. Thirty thousand extras were hired during filming. Spielberg cast children of the Schindlerjuden for key Hebrew-speaking roles and hired Catholic Poles for the survivors.[4] Often, German actors playing the SS would come to Spielberg and say, "Thank you for letting me resolve my [family] secrets by playing in your movie."[7] Halfway during the shoot, Spielberg conceived the epilogue where 128 Schindlerjuden pay their respects to Schindler's grave in Jerusalem. The producers scrambled to find the people portrayed in the film.[4]

Filming

Shooting for Schindler's List began on March 1, 1993 in Kraków, Poland, and continued for seventy-one days.[3] The crew shot at the real life locations, though the Płaszów camp had to be reconstructed in a pit adjacent to the original site, due to post-war changes to the original camp. The crew was forbidden to enter Auschwitz, so they shot at a replica outside the camp.[9] The Polish locals welcomed the filmmakers. There were some antisemitic incidents; anti-Semitic symbols scrawled on local billboards near shooting locations.[4] An elderly woman mistook Fiennes for a Nazi and told him "the Germans were charming people. They didn't kill anybody who didn't deserve it",[10] while Kingsley nearly entered a brawl with an elderly German-speaking businessman who insulted Israeli actor Michael Schneider.[11] Nonetheless, Spielberg stated that at Passover, "all the German actors showed up. They put on yarmulkes and opened up Haggadas, and the Israeli actors moved right next to them and began explaining it to them. And this family of actors sat around and race and culture were just left behind."[11]

"I was hit in the face with my personal life. My upbringing. My Jewishness. The stories my grandparents told me about the Shoah. And Jewish life came pouring back into my heart. I cried all the time."

Steven Spielberg on his emotional state during the shoot[5]

Shooting Schindler's List was deeply emotional for Spielberg, the subject matter forcing him to confront elements of his childhood, such as the antisemitism he faced. He was furious with himself when he did not "cry buckets" while visiting Auschwitz, and was one of many crew members who did not look on during shooting of the scene where aging Jews are forced to run naked while being selected by Nazi doctors to go to Auschwitz.[9] Several actresses broke down when filming the shower scene, including one who was born in a concentration camp.[7] Kate Capshaw and Spielberg's five children accompanied Spielberg on set, and he later thanked his wife "for rescuing me ninety-two days in a row...when things just got too unbearable." Spielberg's parents and his rabbi visited him on set. Robin Williams called Spielberg every two weeks to cheer him up with various jokes,[3] because there was very little humor on set. Spielberg also ordered various episodes of Seinfeld on VHS to watch in his hotel room after shooting each day.[7] Coincidentally, Jerry Seinfeld's watching of Schindler's List in a theater became the plot of a later Seinfeld episode. Spielberg forewent a salary for the film, calling it "blood money", and believed the film would flop.[3]

Spielberg used German and Polish language in scenes to recreate the feeling of being present in the past, and used English to emphasize dramatic points. The director was interested in making the film entirely in German and Polish, but decided "there's too much safety in reading. It would have been an excuse to take their eyes off the screen and watch something else."[7]

Cinematography

Spielberg decided not to plan the film with storyboards, and to shoot the film like a documentary, looking to the documentaries The Twisted Cross (1956)[12] and Shoah (1985) for inspiration. Forty percent of the film was shot with handheld cameras,[13] and the modest budget of $25 million meant the film was shot quickly over seventy-two days. Spielberg felt that this gave the film "a spontaneity, an edge, and it also serves the subject." Spielberg said that he "got rid of the crane, got rid of the Steadicam, got rid of the zoom lenses, [and] got rid of everything that for me might be considered a safety net."[9] Such a style made Spielberg feel like an artist, as he limited his tools for a film he felt didn't have to be commercially successful.[6] This matured Spielberg, who felt that in the past he had always been paying tribute to directors such as Cecil B. DeMille or David Lean.[11] On this film, his shooting style was purely his own. He proudly noted that in this film, there were no crane shots.[4]

The decision to shoot the film mainly in black and white lent to the documentary-style of cinematography, which cinematographer Janusz Kamiński compared to German Expressionism and Italian neorealism.[9] Kamiński said that he wanted to give a timeless sense to the film, so the audience would "not have a sense of when it was made."[9] Spielberg was following suit with "[v]irtually everything I've seen on the Holocaust... which have largely been stark, black and white images."[14] Universal chairman Tom Pollock asked Spielberg to shoot the film in a color negative, to allow color VHS copies of the film to be sold, but Spielberg did not want "to beautify events."[9] Black and white did present challenges to the color-familiar crew. Allan Starski, the production designer, had to make the sets darker or lighter than the people in the scenes, so they would not blend. The costumes had to be distinguished from skin tones or colors being used for the sets.[14]

Music

John Williams composed the score for Schindler's List. The composer was amazed by the film, and felt it would be too challenging. He said to Spielberg, "You need a better composer than I am for this film." Spielberg responded, "I know. But they're all dead!"[15] Williams played the main theme on piano, and following Spielberg's suggestion, he hired Itzhak Perlman to perform it on the violin.

In an interview with Perlman on Schindler's List, he said: "I couldn't believe how authentic he [John Williams] got everything to sound, and I said, 'John, where did it come from?' and he said, 'Well I had some practice with Fiddler on the Roof and so on, and everything just came very naturally' and that's the way it sounds."

Interviewer: "When you were first approached to play for Schindler's List, did you give it a second thought, did you agree at once, or did you say 'I'm not sure I want to play for movie music'?

Perlman: "No, that never occurred to me, because in that particular case the subject of the movie was so important to me, and I felt that I could contribute simply by just knowing the history, and feeling the history, and indirectly actually being a victim of that history."[16]

In the scene where the ghetto is being liquidated by the Nazis, the folk song Oyfn Pripetshik (or Afn Pripetshek) (Template:Lang-yi)" is sung by a children's choir. The song was often sung by Spielberg's grandmother, Becky, to her grandchildren.[17] The clarinet solos heard in the film were recorded by Klezmer virtuoso Giora Feidman. Williams won an Academy Award for Best Original Score for Schindler's List, his fifth win.

Symbols

Girl in red

While the film is shot primarily in black-and-white, red is used to distinguish a little girl in a coat (portrayed by Oliwia Dabrowska). Later in the film, the girl appears to be one of the dead Jewish people, recognizable only by the red coat she is still wearing. Although it was unintentional, this character is coincidentally very similar to Roma Ligocka, who was known in the Kraków Ghetto for her red coat. Ligocka, unlike her fictional counterpart, survived the Holocaust. After the film was released, she wrote and published her own story, The Girl in the Red Coat: A Memoir (2002, in translation).[18] The scene, however, was constructed on the memories of Zelig Burkhut, survivor of Plaszow (and other work camps). When interviewed by Spielberg before the film was made, Burkhut told of a young girl wearing a pink coat, no older than four, who was shot by a Nazi officer right before his eyes. When being interviewed by The Courier-Mail, he said "it is something that stays with you forever."

According to Andy Patrizio of IGN, the girl in the red coat is used to indicate that Schindler has changed: "Spielberg put a twist on her [Ligocka's] story, turning her into one more pile on the cart of corpses to be incinerated. The look on Schindler's face is unmistakable. Minutes earlier, he saw the ash and soot of burning corpses piling up on his car as just an annoyance."[19] Andre Caron wondered whether it was done "to symbolize innocence, hope or the red blood of the Jewish people being sacrificed in the horror of the Holocaust?"[20] Spielberg himself has explained that he only followed the novel, and his interpretation was that

- "America and Russia and England all knew about the Holocaust when it was happening, and yet we did nothing about it. We didn't assign any of our forces to stopping the march toward death, the inexorable march toward death. It was a large bloodstain, primary red color on everyone's radar, but no one did anything about it. And that's why I wanted to bring the color red in."[21]

Although she has no speaking part, the little girl is noted on the Internet Movie Database as the "Red Genia".[citation needed] Her portrayer was Oliwia Dabrowska, 3 years old at the time of filming. Spielberg asked Dabrowska to not watch the film until she was 18 years of age, but she watched it at 11 years, and she said she was "horrified."[22] As a university student she said she was proud of the role she played in the film.[22]

Candles

The beginning features a family observing the Shabbat. Spielberg said, "to start the film with the candles being lit...would be a rich bookend, to start the film with a normal Shabbat service before the juggernaut against the Jews begins." When the color fades out in the film's opening moments, it gives way to a film in which smoke comes to symbolize bodies being burnt at Auschwitz. Only at the end do the images of candle fire regain their warmth when Schindler allows his workers to hold Shabbat services. For Spielberg, they represented "just a glint of color, and a glimmer of hope."[4]

Release

The film opened in New York, Los Angeles and Toronto on December 15, 1993. The film grossed $96.1 million in the United States and over $321.2 million worldwide.[23] In Germany, over 5.8 million admission tickets were sold.

Schindler's List made its US network television premiere on NBC in February 1997. The film was shown without commercials, and fully sponsored by Ford Motor Company. It gained the highest Nielsen rating (to that date) for any film since NBC's broadcast of Jurassic Park (also directed by Spielberg) in May 1995.[24] (For further information on the telecast, see the "Controversies" section below.)

The film was released to DVD on 9 March 2004. The DVD was available in widescreen and fullscreen editions, both being a double-sided disc with the feature film beginning on side A and continuing on side B, along with the special features, which include a documentary introduced by Steven Spielberg. Also released for both formats was a limited edition gift set. The laserdisc gift set was a limited one, with only 10,000 copies manufactured. Besides the DVD, the set included the film's soundtrack, the original novel, and an exclusive photo booklet.[25] Similar to the Laserdisc set, the DVD gift set included the widescreen version of the film, the original novel, the film's soundtrack on CD, a senitype, and a photo booklet titled Schindler's List: Images of the Steven Spielberg Film, all housed in a plexiglass case.[26] The set has since been discontinued.[27]

The film was released on Blu-ray Disc on March 5, 2013 as part of the film's 20th anniversary.[28]

The film is aired on public television in Israel every year on Holocaust Memorial Day, unedited, uncensored and without commercial breaks.[citation needed]

Following the success of the film, Spielberg founded the Survivors of the Shoah Visual History Foundation, a non-profit organisation with the goal of providing an archive for the filmed testimony of as many survivors of the Holocaust as possible, to save their stories. He continues to finance that work.[23] Spielberg used the money from the film to finance several related documentaries, including The Lost Children of Berlin (1996), Anne Frank Remembered (1995), and The Last Days (1998).[23]

Reception

Schindler's List received widespread acclaim from critics. Reviewing Schindler’s List for The New York Review of Books, the leading British critic John Gross wrote: “Suppose the Disney organization announced that it was planning a film about the Holocaust. Spielberg’s films up until now have mostly been fairy tales or adventure stories, or a mixture of both, so I can’t pretend, then, that I approached the film without apprehension. My fears were altogether misplaced. Spielberg shows a firm moral and emotional grasp of his material. The film is an outstanding achievement.”[29] However, film critic Robert Philip Kolker, in his book A Cinema of Loneliness, attacked the film's portrayal of Goeth as "too unrelievedly brutal. He is a psychopath, and psychopathology is too easy a way to dismiss Nazism and its adherents. [...] Ideological elements are so distorted by dreams of power, authority, and manufactured hatred and convictions of necessity, that the majority of a culture gets caught up in the act of killing the demonised other. There were psychotic Germans, to be sure; but Nazism cannot be reduced simply to psychosis. There are scenes in Schindler's List of German officers in a hysterical frenzy of killing that are, perhaps, more accurate than Goeth's unrelenting murderousness, but also bring with them the old Hollywood representations of Nazis as sophisticated gangsters."[30]

Schindler's List was highly received by many of Spielberg's peers. Filmmaker Billy Wilder reportedly wrote a long letter of appreciation to Spielberg in which he proclaimed, "They couldn't have gotten a better man. This movie is absolutely perfection."[31] Roman Polanski, who had turned down Spielberg's offer to direct the film, later commented, "I certainly wouldn't have done as good a job as Spielberg because I couldn't have been as objective as he was." Polanski has also cited Schindler's List as an influence on his 1995 film Death and the Maiden.[32] The success of Schindler's List persuaded filmmaker Stanley Kubrick to abandon his own Holocaust project, Aryan Papers, which would have been about a Jewish boy who survives the war, along with his aunt, by sneaking through Poland while pretending to be a Catholic.[33] Convinced that no film could truly capture the horror of the Holocaust, scriptwriter Frederic Raphael has recalled that Kubrick commented on Schindler's List, "Think that's about the Holocaust? That was about success, wasn't it? The Holocaust is about 6 million people who get killed. Schindler's List is about 600 who don't."[33]

French New Wave filmmaker, Jean-Luc Godard, accused Spielberg of using the film to make a profit of tragedy while Schindler's wife, Emilie Schindler, lived in poverty in Argentina.[34] Author Thomas Keneally has disputed claims that Emilie Schindler was never paid for her contributions to the film, "not least because I had recently sent Emilie a check myself."[35] Filmmaker Michael Haneke also criticized the sequence in the film in which Schindler's women are accidentally sent off to Auschwitz and herded into showers: "There's a scene in that film when we don't know if there's gas or water coming out in the showers in the camp. You can only do something like that with a naive audience like in the United States. It's not an appropriate use of the form. Spielberg meant well – but it was dumb."[36] However, according to one of Schindler's women, Etka Liebgold, this incident is based on fact.[37]

The film was attacked by filmmaker and professor Claude Lanzmann, director of the 9-hour Holocaust documentary Shoah, who called Schindler's List a "kitschy melodrama", and a "deformation" of historical truth. Lanzmann was especially critical of Spielberg for viewing the Holocaust through the eyes of a German. Believing his own film to be the definitive account of the Holocaust, Lanzmann complained, "I sincerely thought that there was a time before Shoah, and a time after Shoah, and that after Shoah certain things could no longer be done. Spielberg did them anyway."[38] Spielberg angrily responded to Lanzmann's criticisms, accusing him of wanting to be "the only voice in the definite account of the Holocaust." He added, "It amazed me that there could be any hurt feelings in an effort to reflect the truth."[39] Hungarian Jewish author Imre Kertész, a Holocaust survivor, also criticized Spielberg for falsifying the experience of the Holocaust in Schindler's List and for showing it as something that is foreign to the human nature and impossible to recur. He also dismissed the film itself, saying "it is obvious that the American Spielberg, who incidentally wasn't even born until after the war, has and can have no idea of the authentic reality of a Nazi concentration camp... I regard as kitsch any representation of the Holocaust that is incapable of understanding or unwilling to understand the organic connection between our own deformed mode of life (whether in the private sphere or on the level of "civilisation" as such) and the very possibility of the Holocaust."[40]

In 2004, the Library of Congress deemed the film "culturally significant" and selected it for preservation in the National Film Registry.[41] Schindler's List featured on a number of other "best of" lists, including the Time magazine's Top Hundred as selected by critics Richard Corliss and Richard Schickel, Time Out magazine's 100 Greatest Films Centenary Poll conducted in 1995, and Leonard Maltin's "100 Must See Movies of the Century". In addition, the Vatican named Schindler's List among the top 45 films ever made.[42] The readers of the German film magazine, Cinema, voted Schindler's List the #1 best movie of all time in 2000.[43] In 2002, a Channel 4 poll named Schindler's List the ninth greatest film of all time,[44] and it ranked fourth in the 2005 war films poll.[45]

Awards

Schindler's List won seven Oscars at the 66th Academy Awards, including Best Picture and Best Director. It was the first black and white film since The Apartment to win the Oscar for Best Picture. Liam Neeson and Ralph Fiennes were nominated for Best Actor and Best Supporting Actor respectively, but did not win.[46] At the British Academy awards, the film won Best Film, the David Lean Award for Direction, Best Supporting Actor (Ralph Fiennes), Cinematography, Editing and Score.[23] Schindler's List won Golden Globes for Best Motion Picture (Drama), Best Director and Best Screenplay, with John Williams awarded the Grammy for the film's musical score.[23]

Academy Award

| Award[47] | Person | |

| Awarded: | ||

| Best Picture | Steven Spielberg Gerald R. Molen Branko Lustig | |

| Best Director | Steven Spielberg | |

| Best Adapted Screenplay | Steven Zaillian | |

| Best Cinematography | Janusz Kamiński | |

| Best Art Direction | Ewa Braun Allan Starski | |

| Best Film Editing | Michael Kahn | |

| Best Original Score | John Williams | |

| Nominated: | ||

| Best Actor | Liam Neeson | |

| Best Supporting Actor | Ralph Fiennes | |

| Best Costume Design | Anna Biedrzycka Sheppard | |

| Best Sound | Andy Nelson Steve Pederson Scott Millan Ron Judkins | |

| Best Makeup | Christina Smith Matthew Mungle Judy Alexander Cory | |

Golden Globe Award

Won

Nominated

American Film Institute recognition

- 1998 AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies—#9[48]

- 2003 AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes and Villains:

- Oskar Schindler—#13 Hero

- Amon Göth—#15 Villain

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Movie Quotes:

- "The list is an absolute good. The list is life." – Nominated[49]

- 2006 AFI's 100 Years...100 Cheers—#3

- 2007 AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition)—#8

- 2008 AFI's 10 Top 10—#3 Epic film

Controversies

This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2012) |

According to Slovak filmmaker Juraj Herz, the scene in which a group of women confuse an actual shower with a gas chamber is taken directly, shot by shot, from his Zastihla mě noc (Night Caught Up with Me, 1986). Herz says he wanted to sue, but was unable to come up with the money to fund the effort.[50]

For the 1997 American television showing of the film, at Spielberg's insistence it aired unedited and nearly uncensored, although the sex scene was mildly edited by removing nearly all of the "thrusting". The film was preceded by a recorded introduction by Spielberg himself, explaining why the film was being aired nearly unedited. The telecast was the first ever to receive a TV-M (now TV-MA) rating under the TV Parental Guidelines that had been established at the beginning of that year.[citation needed] Senator Tom Coburn, then an Oklahoma congressman, said that in airing the film, NBC had brought television "to an all-time low, with full-frontal nudity, violence and profanity", adding that airing the film was an insult to "decent-minded individuals everywhere".[51] Under fire from fellow Republicans as well as from Democrats, Coburn apologized for his criticism, saying: "My intentions were good, but I've obviously made an error in judgment in how I've gone about saying what I wanted to say." He said he hadn't reversed his opinion on airing the film, but said it ought to have been aired later at night when there aren't "large numbers of children watching without parental supervision".[52] The film was subsequently rebroadcast a year later on select PBS stations, once again airing unedited and without Spielberg's prologue.

Controversy arose in Germany for the film's television premiere on Pro 7. Heavy protests ensued after the station intended to televise the film separated by two commercial breaks. As a compromise, the broadcast finally included one break, consisting of a short news update and selected commercials (no alcohol and no hygiene products).[why?][53] Since then, subsequent broadcasts in German television did not include commercial breaks.

In the Philippines chief censor Henrietta Mendez ordered three cuts of Schindler's List, due to its scenes that displayed female nudity and sexual intercourse, before it could be shown. As a result of these proposed cuts Steven Spielberg pulled the film from screening in the Philippines. As a result of Mendez's actions, Philippine senators demanded the abolition of the Philippine censors board. Senate justice committee chairman Raul Roco stated "such narrow-mindedness precisely shows the dangers of censorship." Mendez argued that "the sex act is sacred and beautiful and should be done in the privacy of the bedroom."[54]

The song "Yerushalayim Shel Zahav" ("Jerusalem of Gold") is featured in the film's soundtrack and plays during a key moment near the end of the film. This caused some controversy in Israel when the film was released because the song was written in 1967 and is widely known in Israel as a pop–folk song. The song was therefore edited out of the Israeli release of the film and replaced by the song "Eli, Eli", which was written by the Jewish Hungarian poet Hannah Szenes in World War II and is more appropriate for the time period and subject matter of the film.

See also

References

- ^ "Schindler's List". Boxofficemojo. Retrieved 2012-11-28.

- ^ "The Oscar Schindler". The Holocaust FAQ. Auschwitz.dk. Retrieved 10 October 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f McBride, Joseph (1997). Steven Spielberg. Faber and Faber. pp. 424–27. ISBN 0-571-19177-0.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Thompson, Anne (1994-01-21). "Making History". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 2007-08-08.

- ^ a b McBride, Joseph (1997). Steven Spielberg. Faber and Faber. pp. 414–16. ISBN 0-571-19177-0.

- ^ a b Face to Face. BBC Two. 1994-01-31.

- ^ a b c d e Susan Royal. "An Interview with Steven Spielberg". Inside Film Magazine Online. Retrieved 2008-10-29.

- ^ "Oskar Winner". Entertainment Weekly. 1994-01-21. Retrieved 2007-08-08.

- ^ a b c d e f g McBride, Joseph (1997). Steven Spielberg. Faber and Faber. pp. 429–33. ISBN 0-571-19177-0.

- ^ a b Richard Corliss (1994-02-21). "The Man Behind the Monster". TIME. Retrieved 2007-08-08.

- ^ a b c David Ansen (20 December 1993). "Spielberg's obsession". Vol. 122, no. 25. Newsweek. pp. 112–16.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Steven Spielberg (2006-11-04). The Culture Show (TV). BBC2.

- ^ Schindler's List DVD insert

- ^ a b "Behind The Scenes: Production Notes". Official site. Retrieved 2007-08-08.

- ^ "The man behind the music of 'Star Wars'". NBC. May 6, 2005. Retrieved December 27, 2011.

- ^ "John Williams, Itzhak Perlman - Schindler's List". YouTube. "KlezmorimI". Retrieved 1/8/12.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Susan Goldman Rubin (2001). Steven Spielberg. Harry N. Abrams, Inc. pp. 73–74. ISBN 0-8109-4492-8.

- ^ "The Girl in the Red Coat: A Memoir - Roma Ligocka - Google Boeken". Books.google.com. Retrieved 2012-11-28.

- ^ Andy Patrizio (2004-03-10). "Schindler's List". IGN. Retrieved 2007-08-09.

- ^ Andre Caron. "Spielberg's Fiery Lights". Senses of Cinema. Archived from the original on 2007-08-28. Retrieved 2007-08-09.

- ^ David Anker (director), Steven Spielberg (2005-04-05). Imaginary Witness: Hollywood and the Holocaust. AMC.

{{cite AV media}}:|format=requires|url=(help) - ^ a b Doty, Meriah. "‘Red coat girl’ from ‘Schindler’s List’: I was ‘horrified’." Yahoo! Movies. Monday March 4, 2013. Retrieved on March 11, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e Freer, Ian (2001). The Complete Steven Spielberg. Virgin Books. pp. 220–237. ISBN 0-7535-0556-8.

- ^ "TELEVISION: 'Schindler's' Showing". Los Angeles Times. February 25, 1997. Retrieved 2 February 2012.

- ^ "Schindler's List (1993)—Laserdisc details". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 2009-01-16.

- ^ "Schindler's List—Collector's Gift Set DVD". Film Freak Central. Retrieved 2009-01-16.

- ^ "Schindler's List (1993)". Amazon.com. Retrieved 2009-01-16.

- ^ "Universal Pictures Announces 100th Anniversary Plans". ComingSoon.net. Retrieved 2012-11-28.

- ^ John Gross (February 3, 1994). "Hollywood and the Holocaust". The New York Review of Books. Retrieved 13 September 2010.

- ^ Robert Philip Kolker. A Cinema of Loneliness: Penn, Stone, Kubrick, Scorsese, Spielberg, Altman. Third Edition. p. 320.

- ^ "Steven Spielberg: A Biography - Joseph McBride - Google Books". Books.google.com. Retrieved 2012-11-28.

- ^ "Roman Polanski: Interviews - Roman Polanski, Paul Cronin, Roman Polanski - Google Books". Books.google.com. Retrieved 2012-11-28.

- ^ a b A. Goldmann (August 25, 2005). "Stanley Kubrick's Unrealized Vision". Jewish Journal.com. Retrieved February 5, 2012.

- ^ Bill Gibron (April 21, 2007). "Short Cuts — Forgotten Gems: In Praise of Love". Pop Matters. Retrieved April 28, 2007.

- ^ "Searching for Schindler: A memoir - Thomas Keneally - Google Books". Books.google.com. Retrieved 2012-11-28.

- ^ "Michael Haneke discusses 'The White Ribbon' with Time Out Film - Time Out London". Timeout.com. 2009-11-14. Retrieved 2012-11-28.

- ^ "Auschwitz, the Schindler women and Oskar Schindler". Oskarschindler.dk. Retrieved 2012-11-28.

- ^ Lanzmann, Claude (February 2004). "Schindler's List is an impossible story". University College Utrecht. Retrieved February 5, 2012.

- ^ "Steven Spielberg: A Biography - Joseph McBride - Google Books". Books.google.com. Retrieved 2012-11-28.

- ^ "Holocaust Reflections". Englishillinois.edu. Retrieved 2012-11-28.

- ^ "National Film Registry, List of Films 2004". National Film Registry. Retrieved 2007-10-28.

- ^ "The Vatican Film List — Ten Years Later". Decent Films. Retrieved 2007-10-28.

- ^ Cinema.de 100 Magische Filmmomente: Die besten Filme aller Zeiten

- ^ "100 Greatest Films". Channel 4. 2008-04-08. Retrieved 2008-04-08.

- ^ "100 Greatest War Films". Channel 4. Retrieved 2008-04-08.

- ^ "Schindler's List—Awards and Nominations". Yahoo! Movies. Retrieved 2007-08-08.

- ^ "The 66th Academy Awards (1994) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. Retrieved 2011-08-04.

- ^ Hoberman, J (October 26, 2004). "Still a Contender". The Village Voice. Retrieved February 21, 2009.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "100 Greatest Screen Quotes" (PDF). Afi.com. Retrieved 2012-11-28.

- ^ Ivana Kosulicova (2002-01-07). "Drowning the bad times". Kinoeye. Retrieved 2007-08-08.

- ^ Reason. "The Minority Leader". Reason. Retrieved 2007-08-08.

- ^ "After rebuke, congressman apologizes for 'Schindler's List' remarks". CNN. Associated Press. 1997-02-26. Archived from the original on 2007-10-11. Retrieved 2007-08-08.

- ^ "Article, February 21, 1997 (German)". Berliner Zeitung. 1997-02-21. Retrieved 2010-01-21.

- ^ "Schindler's List in Philippines". Retrieved 15 September 2010.

External links

- Schindler's List at IMDb

- Schindler's List at Rotten Tomatoes

- Schindler's List at Metacritic

- Schindler's List at the TCM Movie Database

- Schindler's List at AllMovie

- The Shoah Foundation, founded by Steven Spielberg to videotape and preserve the testimonies of Holocaust survivors and witnesses.

- Aerial Evidence for Schindler’s List—Through the Lens of History—Yad Vashem

- Schindler's List (film) bibliography via UC Berkeley

- Voices on Antisemitism Interview with Ralph Fiennes from the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum

- Voices on Antisemitism Interview with Sir Ben Kingsley from the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum

- Schindler's List: Myth, movie, and memory, The Village Voice; Mar 29, 1994

- 1993 films

- 1990s drama films

- Amblin Entertainment films

- American biographical films

- American films

- American war drama films

- Films based on biographies

- Best Drama Picture Golden Globe winners

- Best Picture Academy Award winners

- Black-and-white films

- English-language films

- Epic films

- Films based on actual events

- Films based on works by Australian writers

- Films directed by Steven Spielberg

- Films set in Germany

- Films set in Kraków

- Films set in Poland

- Films set in the 1930s

- Films set in the 1940s

- Films shot in Israel

- Films shot in Poland

- Films shot in Kraków

- Films whose art director won the Best Art Direction Academy Award

- Films whose cinematographer won the Best Cinematography Academy Award

- Films whose director won the Best Director Academy Award

- Films whose director won the Best Director Golden Globe

- Films whose editor won the Best Film Editing Academy Award

- Films whose writer won the Best Adapted Screenplay Academy Award

- Best Original Music Score Academy Award winners

- German-language films

- Holocaust films

- Films about Jews and Judaism

- Polish-language films

- United States National Film Registry films

- Universal Pictures films

- War epic films

- 1990s war films

- Films produced by Steven Spielberg

- Screenplays by Steven Zaillian