Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe | |

|---|---|

Goethe in 1828, by Joseph Karl Stieler | |

| Born | Johann Wolfgang Goethe 28 August 1749 Frankfurt, Holy Roman Empire |

| Died | 22 March 1832 (aged 82) Weimar, Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach |

| Occupation | Poet, novelist, playwright, natural philosopher, statesman |

| Language | German |

| Education | |

| Genres |

|

| Literary movement | |

| Years active | From 1770 |

| Notable works | |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 5, including 4 who died young and August von Goethe |

| Parents | |

| Relatives |

|

| Signature | |

| |

| Chancellor of the Exchequer of Duchy of Saxe-Weimar | |

| In office 1782–1784 | |

| Superintendent of the ducal library and Chief Adviser of Saxe-Weimar (from 1775) | |

| Commissioner of the War, Mines and Highways Commissions of Saxe-Weimar (from 1779) | |

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe[a] (28 August 1749 – 22 March 1832) was a German polymath, who is widely regarded as the greatest and most influential writer in the German language. His work has had a profound and wide-ranging influence on Western literary, political, and philosophical thought from the late 18th century to the present day.[3][4] A poet, playwright, novelist, scientist, statesman, theatre director, and critic,[3] his works include plays, poetry and aesthetic criticism, as well as treatises on botany, anatomy, and color.

Goethe took up residence in Weimar in November 1775 following the success of his first novel, The Sorrows of Young Werther (1774), and joined a thriving intellectual and cultural environment under the patronage of Duchess Anna Amalia that had already included Abel Seyler's theatre company and Christoph Martin Wieland, and that formed the basis of Weimar Classicism. He was ennobled by the Duke of Saxe-Weimar, Karl August, in 1782. Goethe was an early participant in the Sturm und Drang literary movement. During his first ten years in Weimar, Goethe became a member of the Duke's privy council (1776–1785), sat on the war and highway commissions, oversaw the reopening of silver mines in nearby Ilmenau, and implemented a series of administrative reforms at the University of Jena. He also contributed to the planning of Weimar's botanical park and the rebuilding of its Ducal Palace.[5][b]

Goethe's first major scientific work, the Metamorphosis of Plants, was published after he returned from a 1788 tour of Italy. In 1791 he was made managing director of the theatre at Weimar, and in 1794 he began a friendship with the dramatist, historian, and philosopher Friedrich Schiller, whose plays he premiered until Schiller's death in 1805. During this period Goethe published his second novel, Wilhelm Meister's Apprenticeship; the verse epic Hermann and Dorothea, and, in 1808, the first part of his most celebrated drama, Faust. His conversations and various shared undertakings throughout the 1790s with Schiller, Johann Gottlieb Fichte, Johann Gottfried Herder, Alexander von Humboldt,[6] Wilhelm von Humboldt, and August and Friedrich Schlegel have come to be collectively termed Weimar Classicism.

The German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer named Wilhelm Meister's Apprenticeship one of the four greatest novels ever written,[7][c] while the American philosopher and essayist Ralph Waldo Emerson selected Goethe as one of six "representative men" in his work of the same name (along with Plato, Emanuel Swedenborg, Montaigne, Napoleon, and Shakespeare). Goethe's comments and observations form the basis of several biographical works, notably Johann Peter Eckermann's Conversations with Goethe (1836). His poems were set to music by many composers including Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, Berlioz, Liszt, Wagner, and Mahler.

Life

[edit]Early life

[edit]

Goethe's grandfather, Friedrich Georg Goethe (1657–1730) moved from Thuringia in 1687 and changed the spelling of his surname (from Göthe to Goethe). In Frankfurt, he first worked as a tailor, then opened a tavern. His son and grandchildren subsequently lived on the fortune he earned. Friedrich Georg Goethe was married twice, his first marriage was to Anna Elisabeth Lutz (1667–1700), the daughter of a burgher Sebastian Lutz (died 1701), with whom he had five children, including Hermann Jakob Goethe (1697–1761), after the death of his first wife in 1705 he married Cornelia Schellhorn, née Walther (1668–1754), widow of the innkeeper Johannes Schellhorn (died 1704), with whom he had four more children, including Johann Caspar Goethe, father of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe.

Goethe's father, Johann Caspar Goethe (1710–1782), lived with his family in a large house (today the Goethe House) in Frankfurt, then a free imperial city of the Holy Roman Empire. Though he had studied law in Leipzig and had been appointed Imperial Councillor, Johann Caspar Goethe was not involved in the city's official affairs.[8] Johann Caspar married Goethe's mother, Catharina Elisabeth Textor (1731–1808), in Frankfurt on 20 August 1748, when he was 38 and she was 17.[9] All their children, with the exception of Johann Wolfgang and his sister Cornelia Friederica Christiana (1750–1777), died at an early age.

The young Goethe received from his father and private tutors lessons in subjects common at the time, especially languages (Latin, Greek, Biblical Hebrew (briefly),[10] French, Italian, and English). Goethe also received lessons in dancing, riding, and fencing. Johann Caspar, feeling frustrated in his own ambitions, was determined that his children should have every advantage he had missed.[8]

Although Goethe's great passion was drawing, he quickly became interested in literature; Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock (1724–1803) and Homer were among his early favorites.[11] He also had a devotion to the theater, and was greatly fascinated by the puppet shows that were annually arranged by occupying French Soldiers at his home and which later became a recurrent theme in his literary work Wilhelm Meister's Apprenticeship.

He also took great pleasure in reading works on history and religion. Of this period he wrote:

I had from childhood the singular habit of always learning by heart the beginnings of books, and the divisions of a work, first of the five books of Moses, and then of the Aeneid and Ovid's Metamorphoses. ... If an ever active imagination, of which that tale may bear witness, led me hither and thither, if the medley of fable and history, mythology and religion, threatened to bewilder me, I readily fled to those oriental regions, and plunged into the first books of Moses, and there, amid the scattered shepherd tribes, found myself at once in the greatest solitude and the greatest society.[12]

Goethe also became acquainted with Frankfurt actors. Valerian Tornius wrote: Goethe – Leben, Wirken und Schaffen.[13] In early literary attempts Goethe showed an infatuation with Gretchen, who would later reappear in his Faust, and the adventures with whom he would describe concisely in Dichtung und Wahrheit.[14] He adored Caritas Meixner (1750–1773), a wealthy Worms merchant's daughter and friend of his sister, who would later marry the merchant G. F. Schuler.[15]

Legal career

[edit]

Goethe studied law at Leipzig University from 1765 to 1768. He detested learning age-old judicial rules by heart, preferring instead to attend the lessons of the university professor and poet Christian Fürchtegott Gellert. In Leipzig, Goethe fell in love with Anna Katharina Schönkopf, the daughter of a craftsman and innkeeper, writing cheerful verses about her in the Rococo genre. In 1770, he released anonymously his first collection of poems, Annette. His uncritical admiration for many contemporary poets evaporated as he developed an interest in Gotthold Ephraim Lessing and Christoph Martin Wieland. By this time, Goethe had already written a great deal, but he discarded nearly all of these works except for the comedy Die Mitschuldigen. The inn Auerbachs Keller and its legend of Johann Georg Faust's 1525 barrel ride impressed him so much that Auerbachs Keller became the only real place in his closet drama Faust Part One. Given that he was making little progress in his formal studies, Goethe was forced to return to Frankfurt at the end of August 1768.

Back in Frankfurt, Goethe became severely ill. During the year and a half that followed, marked by several relapses, relations with his father worsened. During convalescence, Goethe was nursed by his mother and sister. In April 1770, Goethe left Frankfurt in order to finish his studies, this time at the University of Strasbourg.

In Alsace, Goethe blossomed. No other landscape was to be described by him as affectionately as the warm, wide Rhineland. In Strasbourg, Goethe met Johann Gottfried Herder. The two became close friends, and crucially to Goethe's intellectual development, Herder kindled his interest in William Shakespeare, Ossian and in the notion of Volkspoesie (folk poetry). On 14 October 1772 Goethe hosted a gathering in his parents home in honour of the first German "Shakespeare Day". His first acquaintance with Shakespeare's works is described as his personal awakening in the field of literature.[16]

On a trip to the village of Sessenheim in October 1770, Goethe fell in love with Friederike Brion,[17][18] but the tryst ended in August 1771.[19] Several of Goethe's poems, like "Willkommen und Abschied", "Sesenheimer Lieder" and "Heidenröslein", date to this period.

At the end of August 1771, Goethe acquired the academic degree of the Licentiate in Law from Strasbourg and was able to establish a small legal practice in Frankfurt. Although in his academic work he had given voice to an ambition to make jurisprudence progressively more humane, his inexperience led him to proceed too vigorously in his first cases, for which he was reprimanded and lost further clientele. Within a few months, this put an early end to his law career. Around this time, Goethe became acquainted with the court of Darmstadt, where his inventiveness was praised. It was from that world that there came Johann Georg Schlosser (who later became Goethe's brother-in-law) and Johann Heinrich Merck. Goethe also pursued literary plans again; this time, his father did not object, and even helped. Goethe obtained a copy of the biography of a noble highwayman from the German Peasants' War. In a couple of weeks the biography was reworked into a colourful drama titled Götz von Berlichingen, and the work struck a chord among Goethe's contemporaries.

Since Goethe could not subsist on his income as one of the editors of a literary periodical (published by Schlosser and Merck), in May 1772 he once more took up the practice of law, this time at Wetzlar. In 1774 he wrote the book which would bring him worldwide fame, The Sorrows of Young Werther. The broad shape of the work's plot is largely based on what Goethe experienced during his time at Wetzlar with Charlotte Buff (1753–1828)[20] and her fiancé, Johann Christian Kestner (1741–1800),[20] as well as the suicide of the Goethes' friend Karl Wilhelm Jerusalem (1747–1772). In the latter case, Goethe made a desperate passion of what was in reality a hearty and relaxed friendship.[21] Despite the immense success of Werther, it did not bring Goethe much financial gain since the protection later afforded by copyright laws at that time virtually did not exist. (In later years Goethe would counter this problem by periodically authorizing "new, revised" editions of his Complete Works.)[22]

Early years in Weimar

[edit]

In 1775, on the strength of his fame as the author of The Sorrows of Young Werther, Goethe was invited to the court of Karl August, Duke of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach, who later became Grand Duke in 1815. The Duke's mother, Duchess Anna Amalia, had been the long-time regent on behalf of her son until 1775 and was one of the most important patrons of the arts in her day, making her court into a centre of the arts. Her court had hosted the renowned theatre company of Abel Seyler until a 1774 fire had destroyed Schloss Weimar. Karl August came of age when he turned eighteen in 1775, although his mother continued to be a major presence at the court. So it was that Goethe took up residence in Weimar, where he remained for the rest of his life[23] and where, over the course of many years, he held a succession of offices, including superintendent of the ducal library.[24] He was, moreover, the Duke's friend and chief adviser.[25][26]

In 1776, Goethe formed a close relationship with Charlotte von Stein, a married woman seven years older than him. The intimate bond with her lasted for ten years, after which Goethe abruptly left for Italy without giving his companion any notice. She was emotionally distraught at the time, but they were eventually reconciled.[27]

Aside from his official duties, Goethe was also a friend and confidant to Duke Karl August and participated in the activities of the court. For Goethe, his first ten years at Weimar could well be described as a garnering of a degree and range of experiences which perhaps could have been achieved in no other way. In 1779, Goethe took on the War Commission of the Grand Duchy of Saxe-Weimar, in addition to the Mines and Highways commissions. In 1782, when the Duchy's chancellor of the Exchequer left his office, Goethe agreed to act in his place and did so for two and a half years; this post virtually made him prime minister and the principal representative of the Duchy.[3] Goethe was ennobled in 1782 (this being indicated by the "von" in his name). In that same year, Goethe moved into what was his primary residence in Weimar for the next 50 years.[28]

As head of the Saxe-Weimar War Commission, Goethe participated in the recruitment of mercenaries into the Prussian and British military during the American Revolution. The author Daniel Wilson claims that Goethe engaged in negotiating the forced sale of vagabonds, criminals, and political dissidents as part of these activities.[29]

Italy

[edit]

Goethe's journey to the Italian peninsula and Sicily from 1786 to 1788 was of great significance in his aesthetic and philosophical development. His father had made a similar journey, and his example was a major motivating factor for Goethe to make the trip. More importantly, however, the work of Johann Joachim Winckelmann had provoked a general renewed interest in the classical art of ancient Greece and Rome. Thus Goethe's journey had something of the nature of a pilgrimage to it. During the course of his trip Goethe met and befriended the artists Angelica Kauffman and Johann Heinrich Wilhelm Tischbein, as well as encountering such notable characters as Lady Hamilton and Alessandro Cagliostro.

He also journeyed to Sicily during this time, and wrote that "To have seen Italy without having seen Sicily is to not have seen Italy at all, for Sicily is the clue to everything."[30] While in Southern Italy and Sicily, Goethe encountered, for the first time genuine Greek (as opposed to Roman) architecture, and was quite startled by its relative simplicity. Winckelmann had not recognized the distinctness of the two styles.

Goethe's diaries of this period form the basis of the non-fiction Italian Journey. Italian Journey only covers the first year of Goethe's visit. The remaining year is largely undocumented, aside from the fact that he spent much of it in Venice. This "gap in the record" has been the source of much speculation over the years.

In the decades which immediately followed its publication in 1816, Italian Journey inspired countless German youths to follow Goethe's example. This is pictured, somewhat satirically, in George Eliot's Middlemarch.[citation needed]

Weimar

[edit]

In late 1792, Goethe took part in the Battle of Valmy against revolutionary France, assisting Duke Karl August of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach during the failed invasion of France. Again during the Siege of Mainz, he assisted Karl August as a military observer. His written account of these events can be found within his Complete Works.

In 1794, Friedrich Schiller wrote to Goethe offering friendship; they had previously had only a mutually wary relationship ever since first becoming acquainted in 1788. This collaborative friendship lasted until Schiller's death in 1805.

In 1806, Goethe was living in Weimar with his mistress Christiane Vulpius, the sister of Christian A. Vulpius and daughter of archivist Johann Friedrich Vulpius (1725–1786), and their son August von Goethe. On 13 October, Napoleon's army invaded the town. The French "spoon guards", the least disciplined soldiers, occupied Goethe's house:

The 'spoon guards' had broken in, they had drunk wine, made a great uproar and called for the master of the house. Goethe's secretary Riemer reports: 'Although already undressed and wearing only his wide nightgown... he descended the stairs towards them and inquired what they wanted from him.... His dignified figure, commanding respect, and his spiritual mien seemed to impress even them.' But it was not to last long. Late at night they burst into his bedroom with drawn bayonets. Goethe was petrified, Christiane raised a lot of noise and even tangled with them, other people who had taken refuge in Goethe's house rushed in, and so the marauders eventually withdrew again. It was Christiane who commanded and organized the defense of the house on the Frauenplan. The barricading of the kitchen and the cellar against the wild pillaging soldiery was her work. Goethe noted in his diary: "Fires, rapine, a frightful night... Preservation of the house through steadfastness and luck." The luck was Goethe's, the steadfastness was displayed by Christiane.[31]

Days afterward, on 19 October 1806, Goethe legitimized their 18-year relationship by marrying Christiane in a quiet marriage service at the Jakobskirche in Weimar. They had already had several children together by this time, including their son, Julius August Walter von Goethe (1789–1830), whose wife, Ottilie von Pogwisch (1796–1872), cared for the elder Goethe until his death in 1832. August and Ottilie had three children: Walther, Freiherr von Goethe (1818–1885), Wolfgang, Freiherr von Goethe (1820–1883) and Alma von Goethe (1827–1844). Christiane von Goethe died in 1816. Johann reflected, "There is nothing more charming to see than a mother with her child in her arms, and there is nothing more venerable than a mother among a number of her children."[32]

Later life

[edit]After 1793, Goethe devoted his endeavours primarily to literature. In 1812, he travelled to Teplice and Vienna both times meeting his admirer Ludwig van Beethoven, who had set music to Egmont two years prior in 1810. By 1820, Goethe was on amiable terms with Kaspar Maria von Sternberg.

In 1821, having recovered from a near fatal heart illness, the 72-year-old Goethe fell in love with Ulrike von Levetzow, 17 at the time.[33] In 1823, he wanted to marry her, but because of the opposition of her mother, he never proposed. Their last meeting in Carlsbad on 5 September 1823 inspired his poem "Marienbad Elegy" which he considered one of his finest works.[34][35] During that time he also developed a deep emotional bond with the Polish pianist Maria Szymanowska, 33 at the time, and she separated from her husband.[36]

In 1821 Goethe's friend Carl Friedrich Zelter introduced him to the 12-year-old Felix Mendelssohn. Goethe, now in his seventies, was greatly impressed by the child, leading to perhaps the earliest confirmed comparison to Mozart in the following conversation between Goethe and Zelter:

"Musical prodigies ... are probably no longer so rare; but what this little man can do in extemporizing and playing at sight borders the miraculous, and I could not have believed it possible at so early an age." "And yet you heard Mozart in his seventh year at Frankfurt?" said Zelter. "Yes", answered Goethe, "... but what your pupil already accomplishes, bears the same relation to the Mozart of that time that the cultivated talk of a grown-up person bears to the prattle of a child."[37]

Mendelssohn was invited to meet Goethe on several later occasions,[38] and set a number of Goethe's poems to music. His other compositions inspired by Goethe include the overture Calm Sea and Prosperous Voyage (Op. 27, 1828), and the cantata Die erste Walpurgisnacht (The First Walpurgis Night, Op. 60, 1832).[39]

Heinrich Heine, on his hiking tour through Germany (the trip immortalised in his work Die Harzreise) was granted an audience with Goethe in 1824 in Weimar.[40] Heine had been a great admirer of Goethe's in his early youth, sending him some of his earlier works with praising cover notes.[41] The meeting is said to be of a strikingly unsuccessful nature, with Heine completely omitting the meeting in the Harzreise, and speaking flippantly of it in much later life.[42]

Death

[edit]

In 1832, Goethe died in Weimar of apparent heart failure. He is buried in the Ducal Vault at Weimar's Historical Cemetery.

Last words

[edit]The last words of Goethe usually abridged as Mehr Licht!, that is, "more light!", although the original claimed last words quote was longer.

The earliest known account was of Karl Wilhelm Müller's, which gives all of his last words:[43] "Macht doch den zweiten Fensterladen in der Stube auch auf, damit mehr Licht hereinkomme." ("Open the second shutter in the living room so that more light comes in.")

According to his doctor Carl Vogel, his last words were, Mehr Licht! (More light!), but this is disputed as Vogel was not in the room at the moment Goethe died, something he himself says in his account:[44] "[...] "More light" is said to have been the last words of the man, who always hated darkness in every respect, as I had left the dying room for a moment. [...]"

Thomas Carlyle, in his letter to John Carlyle (2 July 1832) records that he had learned the version Macht die Fensterladen auf, damit ich mehr Licht bekomme! ("Open the shutters so I can get more light!") from Sarah Austin:[45] "[...] Mrs. Austin wrote lately that Goethe's last words were, Macht die Fensterladen auf, damit ich mehr Licht bekomme! Glorious man! Happy man! I never think of him but with reverence and pride. [...]" John Ruskin, in his Præterita, narrates a memory of him from his diary record of 25 October 1874 that Carlyle "[...] had been quoting the last words of Goethe, 'Open the window, let us have more light' (this about an hour before painless death, his eyes failing him)."[46]

Even though the context was different, these words, especially the abridged version, which turned into a dictum, usually used as a mean to illustrate the pro-Enlightenment worldview of Goethe.

Aftermath of his death

[edit]The first production of Richard Wagner's opera Lohengrin took place in Weimar in 1850. The conductor was Franz Liszt, who chose the date 28 August in honour of Goethe, who was born on 28 August 1749.[47]

Descendants

[edit]Goethe had five children with Christiane Vulpius. Only their eldest son, August, survived into adulthood. One child was stillborn, while the others died early. Through his son August and daughter-in-law Ottilie, Johann had three grandchildren: Walther, Wolfgang and Alma. Alma died of typhoid fever during the outbreak in Vienna, at age 16. Walther and Wolfgang neither married nor had any children. Walther's gravestone states: "With him ends Goethe's dynasty, the name will last forever," marking the end of Goethe's personal bloodline. While he has no direct descendants, his siblings do.

Literary work

[edit]

Overview

[edit]The most important of Goethe's works produced before he went to Weimar were Götz von Berlichingen (1773), a tragedy that was the first work to bring him recognition, and the novel The Sorrows of Young Werther (German: Die Leiden des jungen Werthers) (1774), which gained him enormous fame as a writer in the Sturm und Drang period which marked the early phase of Romanticism. Indeed, Werther is often considered to be the "spark" which ignited the movement, and can arguably be called the world's first "best-seller". During the years at Weimar before he met Schiller in 1794, he began Wilhelm Meister's Apprenticeship[48] and wrote the dramas Iphigenie auf Tauris (Iphigenia in Tauris),[49] Egmont,[50] and Torquato Tasso[51] and the fable Reineke Fuchs.[52]

To the period of his friendship with Schiller belong the conception of Wilhelm Meister's Journeyman Years (the continuation of Wilhelm Meister's Apprenticeship), the idyll of Hermann and Dorothea, the Roman Elegies and the verse drama The Natural Daughter.[53] In the last period, between Schiller's death, in 1805, and his own, appeared Faust Part One (1808), Elective Affinities (1809), the West-Eastern Diwan (an 1819 collection of poems in the Persian style, influenced by the work of Hafez), his autobiographical Aus meinem Leben: Dichtung und Wahrheit (From My Life: Poetry and Truth, published between 1811 and 1833) which covers his early life and ends with his departure for Weimar, his Italian Journey (1816–17), and a series of treatises on art. Faust, Part Two was completed before his 1832 death and published posthumously later that year. His writings were immediately influential in literary and artistic circles.[53]

Goethe was fascinated by Kalidasa's Abhijñānaśākuntalam, which was one of the first works of Sanskrit literature that became known in Europe, after being translated from English to German.[54]

Details of selected works

[edit]The short epistolary novel Die Leiden des jungen Werthers, or The Sorrows of Young Werther, published in 1774, recounts an unhappy romantic infatuation that ends in suicide. Goethe admitted that he "shot his hero to save himself", a reference to Goethe's near-suicidal obsession for a young woman, a passion he quelled through writing. The novel remains in print in dozens of languages and its influence is undeniable; its central hero, an obsessive figure driven to despair and destruction by his unrequited love for the young Lotte, has become a pervasive literary archetype. The fact that Werther ends with the protagonist's suicide and funeral—a funeral which "no clergyman attended"—made the book deeply controversial upon its (anonymous) publication, for it appeared to condone and glorify suicide. Suicide is considered sinful by Christian doctrine, suicides were denied Christian burial with the bodies often mutilated. The suicide's property was often confiscated by the Church.[55]

Goethe explained his use of Werther in his autobiography. He said he "turned reality into poetry but his friends thought poetry should be turned into reality and the poem imitated". He was against this reading of poetry.[56] Epistolary novels were common during this time, letter-writing being a primary mode of communication. What set Goethe's book apart from other such novels was its expression of unbridled longing for a joy beyond possibility, its sense of defiant rebellion against authority, and of principal importance, its total subjectivity: qualities that trailblazed the Romantic movement.

The next work, his epic closet drama Faust, was completed in stages. The first part was published in 1808 and created a sensation. Goethe finished Faust Part Two in the year of his death, and the work was published posthumously. Goethe's original draft of a Faust play, which probably dates from 1773 to 1774, and is now known as the Urfaust, was also published after his death.[57]

The first operatic version of Goethe's Faust, by Louis Spohr, appeared in 1814. The work subsequently inspired operas and oratorios by Schumann, Berlioz, Gounod, Boito, Busoni and Schnittke, as well as symphonic works by Liszt, Wagner and Mahler. Faust became the ur-myth of many figures in the 19th century. Later, a facet of its plot, i.e., of selling one's soul to the devil for power over the physical world, took on increasing literary importance and became a view of the victory of technology and of industrialism, along with its dubious human expenses. In 1919, the world premiere complete production of Faust was staged at the Goetheanum.

Goethe's poetic work served as a model for an entire movement in German poetry termed Innerlichkeit ("introversion") and represented by, for example, Heine. Goethe's words inspired a number of compositions by, among others, Mozart, Beethoven (who idolised Goethe),[58] Schubert, Berlioz and Wolf. Perhaps the single most influential piece is "Mignon's Song" which opens with one of the most famous lines in German poetry, an allusion to Italy: "Kennst du das Land, wo die Zitronen blühn?" ("Do you know the land where the lemon trees bloom?").

He is also widely quoted. Epigrams such as "Against criticism a man can neither protest nor defend himself; he must act in spite of it, and then it will gradually yield to him", "Divide and rule, a sound motto; unite and lead, a better one", and "Enjoy when you can, and endure when you must", are still in usage or are often paraphrased. Lines from Faust, such as "Das also war des Pudels Kern", "Das ist der Weisheit letzter Schluss", or "Grau ist alle Theorie" have entered everyday German usage.

Some well-known quotations are often incorrectly attributed to Goethe. These include Hippocrates' "Art is long, life is short", which is echoed in Goethe's Faust and Wilhelm Meister's Apprenticeship.

Scientific work

[edit]As to what I have done as a poet,... I take no pride in it... But that in my century I am the only person who knows the truth in the difficult science of colours—of that, I say, I am not a little proud, and here I have a consciousness of a superiority to many.

— Johann Eckermann, Conversations with Goethe

Although his literary work has attracted the most interest, Goethe was also keenly involved in studies of natural science.[59] He wrote several works on morphology and colour theory. In the 1790s, he undertook Galvanic experiments and studied anatomical issues together with Alexander von Humboldt.[6] He also had the largest private collection of minerals in all of Europe. By the time of his death, in order to gain a comprehensive view in geology, he had collected 17,800 rock samples.

His focus on morphology and what was later called homology influenced 19th-century naturalists, although his ideas of transformation were about the continuous metamorphosis of living things and did not relate to contemporary ideas of "transformisme" or transmutation of species. Homology, or as Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire called it "analogie", was used by Charles Darwin as strong evidence of common descent and of laws of variation.[60] Goethe's studies (notably with an elephant's skull lent to him by Samuel Thomas von Soemmerring) led him to independently discover the human intermaxillary bone, also known as "Goethe's bone", in 1784, which Broussonet (1779) and Vicq d'Azyr (1780) had (using different methods) identified several years earlier.[61] While not the only one in his time to question the prevailing view that this bone did not exist in humans, Goethe, who believed ancient anatomists had known about this bone, was the first to prove its existence in all mammals. The elephant's skull that led Goethe to this discovery, and was subsequently named the Goethean Elephant, still exists and is displayed in the Ottoneum in Kassel, Germany.

During his Italian journey, Goethe formulated a theory of plant metamorphosis in which the archetypal form of the plant is to be found in the leaf – he writes, "from top to bottom a plant is all leaf, united so inseparably with the future bud that one cannot be imagined without the other".[62] In 1790, he published his Metamorphosis of Plants.[63][64] As one of the many precursors in the history of evolutionary thought, Goethe wrote in Story of My Botanical Studies (1831):

The ever-changing display of plant forms, which I have followed for so many years, awakens increasingly within me the notion: The plant forms which surround us were not all created at some given point in time and then locked into the given form, they have been given... a felicitous mobility and plasticity that allows them to grow and adapt themselves to many different conditions in many different places.[65]

Goethe's botanical theories were partly based on his gardening in Weimar.[66]

Goethe also popularized the Goethe barometer using a principle established by Torricelli. According to Hegel, "Goethe has occupied himself a good deal with meteorology; barometer readings interested him particularly... What he says is important: the main thing is that he gives a comparative table of barometric readings during the whole month of December 1822, at Weimar, Jena, London, Boston, Vienna, Töpel... He claims to deduce from it that the barometric level varies in the same proportion not only in each zone but that it has the same variation, too, at different altitudes above sea-level".[67]

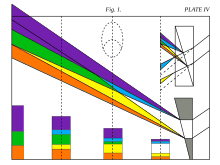

In 1810, Goethe published his Theory of Colours, which he considered his most important work. In it, he contentiously characterized colour as arising from the dynamic interplay of light and darkness through the mediation of a turbid medium.[68] In 1816, Schopenhauer went on to develop his own theory in On Vision and Colours based on the observations supplied in Goethe's book. After being translated into English by Charles Eastlake in 1840, his theory became widely adopted by the art world, most notably J. M. W. Turner.[69] Goethe's work also inspired the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein, to write his Remarks on Colour. Goethe was vehemently opposed to Newton's analytic treatment of colour, engaging instead in compiling a comprehensive rational description of a wide variety of colour phenomena. Although the accuracy of Goethe's observations does not admit a great deal of criticism, his aesthetic approach did not lend itself to the demands of analytic and mathematical analysis used ubiquitously in modern Science. Goethe was, however, the first to systematically study the physiological effects of colour, and his observations on the effect of opposed colours led him to a symmetric arrangement of his colour wheel, "for the colours diametrically opposed to each other ... are those which reciprocally evoke each other in the eye."[70] In this, he anticipated Ewald Hering's opponent colour theory (1872).[71]

Goethe outlines his method in the essay The experiment as mediator between subject and object (1772).[72] In the Kurschner edition of Goethe's works, the science editor, Rudolf Steiner, presents Goethe's approach to science as phenomenological. Steiner elaborated on that in the books The Theory of Knowledge Implicit in Goethe's World-Conception[73] and Goethe's World View,[74] in which he characterizes intuition as the instrument by which one grasps Goethe's biological archetype—The Typus.

Novalis, himself a geologist and mining engineer, expressed the opinion that Goethe was the first physicist of his time and "epoch-making in the history of physics", writing that Goethe's studies of light, of the metamorphosis of plants and of insects were indications and proofs "that the perfect educational lecture belongs in the artist's sphere of work"; and that Goethe would be surpassed "but only in the way in which the ancients can be surpassed, in inner content and force, in variety and depth—as an artist actually not, or only very little, for his rightness and intensity are perhaps already more exemplary than it would seem".[75]

Eroticism

[edit]Many of Goethe's works, especially Faust, the Roman Elegies, and the Venetian Epigrams, depict erotic passions and acts. For instance, in Faust, the first use of Faust's power after signing a contract with the Devil is to seduce a teenage girl. Some of the Venetian Epigrams were held back from publication due to their sexual content. Goethe clearly saw human sexuality as a topic worthy of poetic and artistic depiction, an idea that was uncommon in a time when the private nature of sexuality was rigorously normative.[76]

In a conversation on 7 April 1830 Goethe stated that pederasty is an "aberration" that easily leads to "animal, roughly material" behavior. He continued, "Pederasty is as old as humanity itself, and one can therefore say, that it resides in nature, even if it proceeds against nature....What culture has won from nature will not be surrendered or given up at any price."[77] In one epigram, which are often facetious and satirical, he wrote: "I love boys as well, but girls are even dearer to me. If I tire of her as a girl, she'll serve as a boy for me as well".[78]

Religion and politics

[edit]Goethe was a freethinker who believed that one could be inwardly Christian without following any of the Christian churches, many of whose central teachings he firmly opposed, sharply distinguishing between Christ and the tenets of Christian theology, and criticizing its history as a "hodgepodge of mistakes and violence".[79][80] His own descriptions of his relationship to the Christian faith and even to the Church varied widely and have been interpreted even more widely, so that while Goethe's secretary Eckermann portrayed him as enthusiastic about Christianity, Jesus, Martin Luther, and the Protestant Reformation, even calling Christianity the "ultimate religion",[81] on one occasion Goethe described himself as "not anti-Christian, nor un-Christian, but most decidedly non-Christian,"[82] and in his Venetian Epigram 66, Goethe listed the symbol of the cross among the four things that he most disliked.[83] According to Nietzsche, Goethe had "a kind of almost joyous and trusting fatalism" that has "faith that only in the totality everything redeems itself and appears good and justified."[84]

Born into a Lutheran family, Goethe's early faith was shaken by news of such events as the 1755 Lisbon earthquake and the Seven Years' War. A year before his death, in a letter to Sulpiz Boisserée, Goethe wrote that he had the feeling that all his life he had been aspiring to qualify as one of the Hypsistarians, an ancient sect of the Black Sea region who, in his understanding, sought to reverence, as being close to the Godhead, what came to their knowledge of the best and most perfect.[85] Goethe's unorthodox religious beliefs led him to be called "the great heathen" and provoked distrust among the authorities of his time, who opposed the creation of a Goethe monument on account of his offensive religious creed.[86] August Wilhelm Schlegel considered Goethe "a heathen who converted to Islam."[86]

Goethe showed interest in other religions, including Islam, although Karic suggests that attempts to claim Goethe for any religion "is a pointless, Sysiphean task".[87] At age 23, Goethe wrote a poem about a river, originally part of a dramatic dialogue, which he published as a separate work called Mahomets Gesang ("Muhammad's Song").[88][89] The poem's depiction of nature and forces within it is consonant with his Sturm und Drang years.[90] In 1819, he published his West–östlicher Divan to ignite a poetic dialogue between East and West.[91]

Politically, Goethe described himself as a "moderate liberal".[92][93][94] He was critical of the radicalism of Bentham and expressed sympathy for the liberalism of François Guizot.[95] At the time of the French Revolution, he thought the enthusiasm of the students and professors to be a perversion of their energy and remained skeptical of the ability of the masses to govern.[96] Goethe sympathized with the American Revolution and later wrote a poem in which he declared "America, you're better off than our continent, the old."[97][98] He did not join in the anti-Napoleonic mood of 1812, and he distrusted the strident nationalism which started to be expressed.[99] The medievalism of the Heidelberg Romantics was also repellent to Goethe's eighteenth-century ideal of a supra-national culture.[100]

Goethe was a Freemason, joining the lodge Amalia in Weimar in 1780, and frequently alluded to Masonic themes of universal brotherhood in his work.[101] He was also attracted to the Illuminati, a Bavarian secret society founded on 1 May 1776.[102][101]

Although often requested to write poems arousing nationalist passions, Goethe would always decline. In old age, he explained why this was so to Eckermann:

How could I write songs of hatred when I felt no hate? And, between ourselves, I never hated the French, although I thanked God when we were rid of them. How could I, to whom the only significant things are civilization [Kultur] and barbarism, hate a nation which is among the most cultivated in the world, and to which I owe a great part of my own culture? In any case this business of hatred between nations is a curious thing. You will always find it more powerful and barbarous on the lowest levels of civilization. But there exists a level at which it wholly disappears, and where one stands, so to speak, above the nations, and feels the weal or woe of a neighboring people as though it were one's own.[103]

Influence

[edit]

In a letter written to Leopold Casper in 1932, Einstein wrote that he admired Goethe as 'a poet without peer, and as one of the smartest and wisest men of all time'. He goes on to say, 'even his scholarly ideas deserve to be held in high esteem, and his faults are those of any great man'.

Goethe had a breadth of influence on the nineteenth century which in many respects has woven itself into the fabric of ideas which have now become widespread. He produced volumes of poetry, essays, criticism, a theory of colours and early work on evolution and linguistics. He was fascinated by mineralogy, and the mineral goethite (iron oxide) is named after him.[104] His non-fiction writings, most of which are philosophic and aphoristic in nature, spurred the development of many thinkers, including Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel,[105] Arthur Schopenhauer,[106] Søren Kierkegaard,[107] Friedrich Nietzsche,[108] Ernst Cassirer,[109] and Carl Jung.[110] Along with Schiller, he was one of the leading figures of Weimar Classicism. Schopenhauer cited Goethe's novel Wilhelm Meister's Apprenticeship as one of the four greatest novels ever written, along with Tristram Shandy, La Nouvelle Héloïse and Don Quixote.[7] Nietzsche wrote, "Four pairs it was that did not deny themselves to my sacrifice: Epicurus and Montaigne, Goethe and Spinoza, Plato and Rousseau, Pascal and Schopenhauer. With these I must come to terms when I have long wandered alone; they may call me right and wrong; to them will I listen when in the process they call each other right and wrong."[111]

Goethe embodied many of the contending strands in art over the next century: his work could be lushly emotional, and rigorously formal, brief and epigrammatic, and epic. He would argue that Classicism was the means of controlling art, and that Romanticism was a sickness, even as he penned poetry rich in memorable images, and rewrote the formal rules of German poetry. His poetry was set to music by almost every major Austrian and German composer from Mozart to Mahler, and his influence would spread to French drama and opera as well. Beethoven declared that a "Faust" Symphony would be the greatest thing for art. Liszt and Mahler both created symphonies in whole or in large part inspired by this seminal work, which would give the 19th century one of its most paradigmatic figures: Doctor Faustus.

The Faust tragedy/drama, often called Das Drama der Deutschen (the drama of the Germans), written in two parts published decades apart, would stand as his most characteristic and famous artistic creation. Followers of the twentieth-century esotericist Rudolf Steiner built a theatre named the Goetheanum after him—where festival performances of Faust are still performed.

Goethe was also a cultural force. During his first meeting with Napoleon in 1808, the latter famously remarked: "Vous êtes un homme (You are a man)!"[112] The two discussed politics, the writings of Voltaire, and Goethe's Sorrows of Young Werther, which Napoleon had read seven times and ranked among his favorites.[113][114] Goethe came away from the meeting deeply impressed with Napoleon's enlightened intellect and his efforts to build an alternative to the corrupt old regime.[113][115] Goethe always spoke of Napoleon with the greatest respect, confessing that "nothing higher and more pleasing could have happened to me in all my life" than to have met Napoleon in person.[116]

Germaine de Staël, in De l'Allemagne (1813), presented German Classicism and Romanticism as a potential source of spiritual authority for Europe, and identified Goethe as a living classic.[117] She praised Goethe as possessing "the chief characteristics of the German genius" and uniting "all that distinguishes the German mind."[117] Staël's portrayal helped elevate Goethe over his more famous German contemporaries and transformed him into a European cultural hero.[117] Goethe met with her and her partner Benjamin Constant, with whom he shared a mutual admiration.[118]

In Victorian England, Goethe's great disciple was Thomas Carlyle, who wrote the essays "Faustus" (1822), "Goethe's Helena" (1828), "Goethe" (1828), "Goethe's Works" (1832), "Goethe's Portrait" (1832), and "Death of Goethe" (1832) which introduced Goethe to English readers; translated Wilhelm Meister's Apprenticeship (1824) and Travels (1826), "Faust's Curse" (1830), "The Tale" (1832), "Novelle" (1832) and "Symbolum" at a time when few read German; and with whom Goethe corresponded.[119][120] Goethe exerted a profound influence on George Eliot, whose partner George Henry Lewes wrote a Life of Goethe (dedicated to Carlyle).[121][122] Eliot presented Goethe as "eminently the man who helps us to rise to a lofty point of observation" and praised his "large tolerance", which "quietly follows the stream of fact and of life" without passing moral judgments.[121] Matthew Arnold found in Goethe the "Physician of the Iron Age" and "the clearest, the largest, the most helpful thinker of modern times" with a "large, liberal view of life".[123]

It was to a considerable degree due to Goethe's reputation that the city of Weimar was chosen in 1919 as the venue for the national assembly, convened to draft a new constitution for what would become known as Germany's Weimar Republic. Goethe became a key reference for Thomas Mann in his speeches and essays defending the republic.[124] He emphasized Goethe's "cultural and self-developing individualism", humanism, and cosmopolitanism.[124]

The Federal Republic of Germany's cultural institution, the Goethe-Institut, is named after him, and promotes the study of German abroad and fosters knowledge about Germany by providing information on its culture, society and politics.

The literary estate of Goethe in the Goethe and Schiller Archives was inscribed on UNESCO's Memory of the World Register in 2001 in recognition of its historical significance.[125]

Goethe's influence was dramatic because he understood that there was a transition in European sensibilities, an increasing focus on sense, the indescribable, and the emotional. This is not to say that he was emotionalistic or excessive; on the contrary, he lauded personal restraint and felt that excess was a disease: "There is nothing worse than imagination without taste". Goethe praised Francis Bacon for his advocacy of science based on experiment and his forceful revolution in thought as one of the greatest strides forward in modern science.[126] However, he was critical of Bacon's inductive method and approach based on pure classification.[127] He said in Scientific Studies:

We conceive of the individual animal as a small world, existing for its own sake, by its own means. Every creature is its own reason to be. All its parts have a direct effect on one another, a relationship to one another, thereby constantly renewing the circle of life; thus we are justified in considering every animal physiologically perfect. Viewed from within, no part of the animal is a useless or arbitrary product of the formative impulse (as so often thought). Externally, some parts may seem useless because the inner coherence of the animal nature has given them this form without regard to outer circumstance. Thus...[not] the question, What are they for? but rather, Where do they come from?[128]

Goethe's scientific and aesthetic ideas have much in common with Denis Diderot, whose work he translated and studied.[129][130] Both Diderot and Goethe exhibited a repugnance towards the mathematical interpretation of nature; both perceived the universe as dynamic and in constant flux; both saw "art and science as compatible disciplines linked by common imaginative processes"; and both grasped "the unconscious impulses underlying mental creation in all forms."[129][130] Goethe's Naturanschauer is in many ways a sequel to Diderot's interprète de la nature.[130]

His views make him, along with Adam Smith, Thomas Jefferson, and Ludwig van Beethoven, a figure in two worlds: on the one hand, devoted to the sense of taste, order, and finely crafted detail, which is the hallmark of the artistic sense of the Age of Reason and the neo-classical period of architecture; on the other, seeking a personal, intuitive, and personalized form of expression and society, firmly supporting the idea of self-regulating and organic systems. George Henry Lewes celebrated Goethe's revolutionary understanding of the organism.[129]

Thinkers such as Ralph Waldo Emerson would take up many similar ideas in the 1800s. Goethe's ideas on evolution would frame the question that Darwin and Wallace would approach within the scientific paradigm. The Serbian inventor and electrical engineer Nikola Tesla was heavily influenced by Goethe's Faust, his favorite poem, and had actually memorized the entire text. It was while reciting a certain verse that he was struck with the epiphany that would lead to the idea of the rotating magnetic field and ultimately, alternating current.[131]

The public university in the city of Frankfurt am Main was named after Goethe, the Goethe University.

Books related to Goethe

[edit]- Biermann, Berthold (ed.).Goethe's World: As Seen in Letters and Memoirs.

- Boyle, Nicholas. Goethe: The Poet and the Age (2 vols.).

- Brandes, Georg. Wolfgang Goethe. New York: Crown Publishers, 1936.

- Eckermann, Johann Peter. Conversations with Goethe.

- Eissler, Kurt R.. Goethe: A Psychoanalytic Study.

- Friedenthal, Richard. Goethe: His Life and Times.

- Goethe-Wörterbuch (Goethe Dictionary, abbreviated GWb). Stuttgart. Kohlhammer Verlag; ISBN 978-3-17-019121-1

- Hammer, Carl Jr.Goethe and Rousseau: Resonances of their Mind.

- Holm-Hadulla, Rainer Matthias. Goethe's Path to Creativity: A Psycho-Biography of the Eminent Politician, Scientist and Poet, New York: Routledge, 2019. ISBN 9780429459535

- Lewes, George Henry. The Life of Goethe.

- Ludwig, Emil. Goethe: The History of a Man.

- Mann, Thomas. Lotte in Weimar: The Beloved Returns.

- Nicholls, Angus. Goethe's Concept of the Daemonic: After the Ancients.

- Pagel, Louis. Doctor Faustus of the Popular Legend: Marlowe, the Puppet-Play, Goethe, and Lenau: Treated Historically and Critically: a Parallel between Goethe and Schiller: an Historic Outline of German Literature. 1883.

- Reed, T. J.. Goethe.

- Schweitzer, Albert. Goethe: Four Studies.

- Unseld, Siegfried. Goethe and his Publishers.

- Wilkinson, E. M. and L. A. Willoughby. Goethe Poet and Thinker.

- Williams, John. The Life of Goethe. A Critical Biography.

Works

[edit]See also

[edit]- Young Goethe in Love (2010)

- Dora Stock – her encounters with the 16-year-old Goethe.

- Goethe Basin, a large crater on the planet Mercury

- Johann-Wolfgang-von-Goethe-Gymnasium

- W. H. Murray – author of misattributed quotation "Until one is committed ..."

- "Nature", essay often mis-attributed to Goethe

- Goethe University

Awards named after him

Notes

[edit]- ^ Pronounced /ˈɡɜːrtə/ GUR-tə, also US: /ˈɡʌtə, ˈɡeɪtə, -ti/ GUT-ə, GAY-tə, -ee;[1][2] German: [ˈjoːhan ˈvɔlfɡaŋ fɔn ˈɡøːtə] .[2]

- ^ In 1998, both of these sites, together with nine others, were designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site under the name Classical Weimar.[5]

- ^ The others Schopenhauer named were Tristram Shandy, La Nouvelle Héloïse, and Don Quixote.[7]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ "Goethe". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster.

- ^ a b Wells, John (2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Pearson Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0.

- ^ a b c Nicholas Boyle, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe at the Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ "Johann Wolfgang von Goethe — Biography". knarf.english.upenn.edu. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ a b "Classical Weimar UNESCO Justification". Justification for UNESCO Heritage Cites. UNESCO. Archived from the original on 29 July 2022. Retrieved 7 June 2012.

- ^ a b Daum, Andreas W. (March 2019). "Social Relations, Shared Practices, and Emotions: Alexander von Humboldt's Excursion into Literary Classicism and the Challenges to Science around 1800". The Journal of Modern History. 91 (1). University of Chicago: 1–37. doi:10.1086/701757. S2CID 151051482. Archived from the original on 17 April 2021. Retrieved 19 February 2021.

- ^ a b c Schopenhauer, Arthur (January 2004). "The Art of Literature". The Essays of Arthur Schopenahuer. Archived from the original on 4 May 2015. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- ^ a b Herman Grimm: Goethe. Vorlesungen gehalten an der Königlichen Universität zu Berlin. Vol. 1. J.G. Cotta'sche Buchhandlung Nachfolger, Stuttgart / Berlin 1923, p. 36

- ^ Catharina was the daughter of Johann Wolfgang Textor (1693–1771), sheriff (Schultheiß) of Frankfurt, and of Anna Margaretha Lindheimer (1711–1783).

- ^ Kruse, Joseph A. (2018). "Poetisch-religiöse Vorratskammer – Die Hebräische Bibel bei Goethe und Heine". In Anna-Dorothea Ludewig; Steffen Höhne (eds.). Goethe und die Juden – die Juden und Goethe (in German). Walter de Gruyter. p. 71. ISBN 9783110530421.

- ^ Oehler, R 1932, "Buch und Bibliotheken unter der Perspektive Goethe – Goethe's attitude toward books and libraries", The Library Quarterly, 2, pp. 232–249

- ^ Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von. The Autobiography of Goethe: Truth and Poetry, From My Own Life, Volume 1 (1897), translated by John Oxenford, pp. 114, 129

- ^ Ludwig-Röhrscheid-Verlag, Bonn 1949, p. 26

- ^ Emil Ludwig: Goethe – Geschichte eines Menschen. Vol. 1. Ernst-Rowohlt-Verlag, Berlin 1926, pp. 17–18

- ^ Karl Goedeke: Goethes Leben. Cotta / Kröner, Stuttgart around 1883, pp. 16–17.

- ^ "Originally speech of Goethe to the Shakespeare's Day by University Duisburg". Uni-duisburg-essen.de. Archived from the original on 12 February 2013. Retrieved 17 July 2014.

- ^ Herman Grimm: Goethe. Vorlesungen gehalten an der Königlichen Universität zu Berlin. Vol. 1. J. G. Cotta'sche Buchhandlung Nachfolger, Stuttgart / Berlin 1923, p. 81

- ^ Karl Robert Mandelkow, Bodo Morawe: Goethes Briefe. 2. edition. Vol. 1: Briefe der Jahre 1764–1786. Christian Wegner, Hamburg 1968, p. 571

- ^ Valerian Tornius: Goethe – Leben, Wirken und Schaffen. Ludwig-Röhrscheid-Verlag, Bonn 1949, p. 60

- ^ a b Mandelkow, Karl Robert (1962). Goethes Briefe. Vol. 1: Briefe der Jahre 1764–1786. Christian Wegner Verlag. p. 589

- ^ Mandelkow, Karl Robert (1962). Goethes Briefe. Vol. 1: Briefe der Jahre 1764–1786. Christian Wegner Verlag. pp. 590–592

- ^ See Goethe and his Publishers.

- ^ Robertson, John George (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 12 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 183.

- ^ Gosnell, Charles F., and Géza Schütz. 1932. "Goethe the Librarian." Library Quarterly 2 (January): 367–374.

- ^ Hume Brown, Peter (1920). Life of Goethe. pp. 224–225.

- ^ "Goethe und Carl August – Freundschaft und Politik" Archived 9 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine by Gerhard Müller, in Th. Seemann (ed.): Anna Amalia, Carl August und das Ereignis Weimar. Jahrbuch der Klassik Stiftung Weimar 2007. Göttingen: Wallstein Verlag, pp. 132–164 (in German)

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 25 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 871.

- ^ "The Goethe Residence". Klassik Siftung Weimar. Archived from the original on 29 July 2022. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- ^ Craig, Gordon A.; Wilson, W. Daniel. "The Goethe Case | W. Daniel Wilson". The New York Review of Books 2022. ISSN 0028-7504. Archived from the original on 22 July 2022. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- ^ Desmond, Will D. (2020). Hegel's Antiquity. Oxford University Press. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-19-257574-6.

- ^ Safranski, Rüdiger (1990). Schopenhauer and the Wild Years of Philosophy. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-79275-3.

- ^ Chamberlain, Alexander (1896). The Child and Childhood in Folk Thought: (The Child in Primitive Culture), p. 385. MacMillan. ISBN 9781421987484.

- ^ Gersdorff, Dagmar von [in German] (2005). Goethes späte Liebe (in German). Insel Verlag. ISBN 978-3-458-19265-7.

- ^ "Ulrika von Levetzowová". hamelika.cz (in Czech). Archived from the original on 18 October 2022. Retrieved 22 March 2022.

- ^ The encounter is described in Stefan Zweig's 1927 book, Decisive Moments in History

- ^ Briscoe, J. R. (Ed.). (2004). New Historical Anthology of Music by Women (Vol. 1). Indiana University Press. pp. 126–127.

- ^ Todd 2003, p. 89.

- ^ Mercer-Taylor 2000, pp. 41–42, 93.

- ^ Todd 2003, pp. 188–190, 269–270.

- ^ Spencer, Hanna (1982). Heinrich Heine. MA: Boston: Twayne Publishers. p. 34. Retrieved 3 June 2024.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Müller, Karl Wilhelm (1832). Goethe's letzte literarische Thätigkeit, Verhältniss zum Ausland und Scheiden nach dem Mittheilungen seiner freunde. Jena: Friedrich Frommann. p. 29. ISBN 978-3-598-50924-7. Retrieved 12 July 2024.

- ^ Vogel, Carl (1833). "Die letzte Krankheit Goethe's beschrieben und nebst einigen andern Bemerkungen über denselben". Journal der Practischen Heilkunde. LXXVI (II): 17.

[...] "Mehr Licht" sollen, während ich das Sterbezimmer auf einen Moment verlassen hatte, die letzten Worte des Mannes gewesen seyn, dem Finsterniss in jeder Beziehung stets verhasst war. [...]

Christoph Wilhelm Hufeland in his postscript commented: "He ended with the words: "More light" —He has now received it.— We want to be told this as an obituary, to encourage and revive us." Hufeland, C. W. (1833). "Nachschrift". Journal der Practischen Heilkunde. LXXVI (II): 32.Er endete mit den Worten: "Mehr Licht" —Ihm ist es nun geworden.— Wir wollen es uns gesagt seyn lassen, als Nachruf, zur Ermunterung und Belebung.

- ^ Froude, James Anthony (1882). Thomas Carlyle: a History of the First Forty Years of His Life, 1795-1835 — In Two Volumes (Vol. II). New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 241.

- ^ Ruskin, John (1888). Præterita: Outlines of Scenes and Thoughts, Perhaps Worth of Memory, in My Past Life (Vol. II). New York: John Wiley & Sons. p. 428. Retrieved 12 July 2024.

- ^ Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians, 5th ed., 1954[page needed]

- ^ Ludwig, Emil (1928) Goethe: The History of a Man 1749–1833, Schiller and Wilhelm Meister Translated by Ethel Colburn Mayne, New York: G.P. Putnum's Sons.

- ^ Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1966). Iphigenia in Tauris. Manchester University Press. p. 15.

- ^ Sharpe, Lesley (July 1982). "Schiller and Goethe's 'Egmont'". The Modern Language Review. 77 (3): 629–645. doi:10.2307/3728071. JSTOR 3728071. Archived from the original on 18 July 2021. Retrieved 18 July 2021.

- ^ Lamport, Francis John. 1990. German Classical Drama: Theatre, Humanity and Nation, 1750–1870. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-36270-9. p. 90.

- ^ "Johann Wolfgang von Goethe: Return to Weimar and the French Revolution (1788–94)". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 18 July 2021. Retrieved 18 July 2021.

- ^ a b See, generally Schiller, F. (1877). Correspondence between Schiller and Goethe, from 1794 to 1805 (Vol. 1). G. Bell.

- ^ Baumer, Rachel Van M.; Brandon, James R. (1993) [1981]. Sanskrit Drama in Performance. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 9. ISBN 978-81-208-0772-3.

- ^ "The Stigma of Suicide – A history". Pips Project. Archived from the original on 6 October 2007. See also: "Ophelia's Burial". Archived from the original on 25 June 2010. Retrieved 4 August 2007.

- ^ Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von (1848). "The Auto-Biography of Goethe. Truth and Poetry: From My Own Life". Translated by John Oxenford. London: Henry G. Bohn. p. [page needed] – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Goethe's Plays, by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, translated into English with introductions by Charles E. Passage, Publisher Benn Limited, 1980, ISBN 978-0-510-00087-5, 978-0-510-00087-5

- ^ Wigmore, Richard (2 July 2012). "A meeting of genius: Beethoven and Goethe, July 1812". Gramophone. Haymarket. Archived from the original on 21 December 2019. Retrieved 6 July 2012.

- ^ "Johann Wolfgang von Goethe". The Nature Institute. Archived from the original on 8 October 2020. Retrieved 28 August 2008.

- ^ Darwin, C.R. (1859). On the origin of species by means of natural selection, or the preservation of favoured races in the struggle for life (1st ed.). John Murray. Archived from the original on 7 April 2022. Retrieved 9 February 2007.

- ^ K. Barteczko; M. Jacob (1999). "A re-evaluation of the premaxillary bone in humans". Anatomy and Embryology. 207 (6): 417–437. doi:10.1007/s00429-003-0366-x. PMID 14760532. S2CID 13069026.

- ^ Goethe, J.W. Italian Journey. Robert R Heitner. Suhrkamp ed., vol. 6.

- ^ Versuch die Metamorphose der Pflanzen zu Erklären. Library of Congress. Archived from the original on 3 January 2018. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ^ Magnus, Rudolf; Schmid, Gunther (2004). Metamorphosis of Plants. Kessinger. ISBN 978-1-4179-4984-7. Retrieved 28 August 2008.

- ^ Frank Teichmann (tr. Jon McAlice) "The Emergence of the Idea of Evolution in the Time of Goethe" Archived 23 April 2013 at the Wayback Machine first published in Interdisciplinary Aspects of Evolution, Urachhaus (1989)

- ^ Balzer, Georg (1966). Goethe als Gartenfreund. München: F. Bruckmann KG.

- ^ Hegel, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich; Miller, Arnold V. (2004). Hegel's Philosophy of Nature: Being Part Two of the Encyclopedia of the Philosophical Sciences (1830), Translated from Nicolin and Pöggeler's Edition (1959), and from the Zusätze in Michelet's Text (1847). Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-927267-9. Archived from the original on 4 April 2023. Retrieved 8 January 2023.

- ^ Aristotle wrote that colour is a mixture of light and dark, since white light is always seen as somewhat darkened when it is seen as a colour. (Aristotle, On Sense and its Objects, III, 439b, 20 ff.: "White and black may be juxtaposed in such a way that by the minuteness of the division of its parts each is invisible while their product is visible, and thus colour may be produced.") See Aristotle; Ross, George Robert Thomson (1906). Aristotle De sensu and De memoria; text and translation, with introduction and commentary. Robarts – University of Toronto. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Bockemuhl, M. (1991). Turner. Taschen, Koln. ISBN 978-3-8228-6325-1.

- ^ Goethe, Johann (1810). Theory of Colours, paragraph No. 50. Archived from the original on 16 December 2021. Retrieved 16 November 2014.

- ^ "Goethe's Color Theory". Archived from the original on 16 September 2008. Retrieved 28 August 2008.

- ^ "The Experiment as Mediator between Subject and Object". Archived from the original on 10 November 2011. Retrieved 26 June 2014.

- ^ "The Theory of Knowledge Implicit in Goethe's World Conception". 1979. Retrieved 28 August 2008.

- ^ "Goethe's World View". Retrieved 28 August 2008.

- ^ 'Goethe's Message of Beauty in Our Twentieth Century World', (Friedrich) Frederick Hiebel, RSCP California. ISBN 978-0-916786-37-3

- ^ Outing Goethe and His Age; edited by Alice A. Kuzniar.[page needed]

- ^ Goethe, Johann Wolfgang (1976). Gedenkausgabe der Werke, Briefe und Gespräche. Zürich : Artemis Verl. p. 686. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- ^ Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von (1884). Zarncke, Friedrich (ed.). Notizbuch von der schlesischen Reise im Jahre 1790 zur Begrüssing der deutsch-romanischen Section der XXXVII Versammlung deutscher Philologen und Schulmänner in Dessau am 1. October 1884. Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel. p. 15. Archived from the original on 13 October 2023. Retrieved 22 September 2023.

- ^ The phrase Goethe uses is "Mischmasch von Irrtum und Gewalt", in his "Zahme Xenien" IX, Goethes Gedichte in Zeitlicher Folge, Insel Verlag 1982 ISBN 978-3-458-14013-9, p. 1121

- ^ Arnold Bergsträsser, "Goethe's View of Christ", Modern Philology, vol. 46, no. 3 (February 1949), pp. 172–202; Martin Tetz, "Mischmasch von Irrtum und Gewalt. Zu Goethes Vers auf die Kirchengeschichte", Zeitschrift für Theologie und Kirche, 88 (1991) pp. 339–363

- ^ Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von; Eckermann, Johann Peter; Soret, Frédéric Jacob (1850). Conversations of Goethe with Eckermann and Soret, Vol. II, pp. 423–424. Retrieved 17 July 2014.

- ^ Boyle 1992, 353[incomplete short citation]

- ^ Thompson, James (1895). Venetian Epigrams. Retrieved 17 July 2014. Venetian Epigrams, 66, ["Wenige sind mir jedoch wie Gift und Schlange zuwider; Viere: Rauch des Tabacks, Wanzen und Knoblauch und †."]. The cross symbol he drew has been variously understood as meaning Christianity, Christ, or death.

- ^ Friedrich Nietzsche, The Will to Power, § 95

- ^ Letter to Boisserée dated 22 March 1831 quoted in Peter Boerner, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe 1832/1982: A Biographical Essay. Bonn: Inter Nationes, 1981 p. 82

- ^ a b Krimmer, Elisabeth; Simpson, Patricia Anne (2013). Religion, Reason, and Culture in the Age of Goethe. Boydell & Brewer. p. 99.

- ^ Karic, Enes, "Goethe, His Era, and Islam". p. 100. Retrieved 14 December 2022.

- ^ "Mahomets Gesang". The LiederNet Archive. Archived from the original on 24 September 2022. Retrieved 15 November 2022.

- ^ Jolle, Jonas (2004). The River and its Metaphors: Goethe's "Mahoments Gesang".

- ^ Jolle, Jonas (2004). "The River and its Metaphors: Goethe's "Mahomets Gesang"". MLN. 119 (3): 431–450. doi:10.1353/mln.2004.0111. ISSN 1080-6598. S2CID 161893614.

- ^ Dallmayr, F. (2002). Dialogue Among Civilizations. NY: Macmillan Palgrave. p. 152.

- ^ Eckermann, Johann Peter (1901). Conversations with Goethe. M.W. Dunne. p. 320.

'Dumont,' returned Goethe, 'is a moderate liberal, just as all rational people are and ought to be, and as I myself am.'

- ^ Selth, Jefferson P. (1997). Firm Heart and Capacious Mind: The Life and Friends of Etienne Dumont. University Press of America. pp. 132–133.

- ^ Mommsen, Katharina (2014). Goethe and the Poets of Arabia. Boydell & Brewer. p. 70.

- ^ Peter Eckermann, Johann (1901). Conversations with Goethe. M.W. Dunne. pp. 317–319.

- ^ McCabe, Joseph. 'Goethe: The Man and His Character'. p. 343

- ^ Unseld 1996, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Gemünden, Gerd (1998). Framed Visions: Popular Culture, Americanization, and the Contemporary German and Austrian Imagination. University of Michigan Press. pp. 18–19.

- ^ Unseld 1996, p. 212.

- ^ Richards, David B. (1979). Goethe's Search for the Muse: Translation and Creativity. John Benjamins Publishing. p. 83.

- ^ a b Beachy, Robert (2000). "Recasting Cosmopolitanism: German Freemasonry and Regional Identity in the Early Nineteenth Century". Eighteenth-Century Studies. 33 (2): 266–274. doi:10.1353/ecs.2000.0002. JSTOR 30053687. S2CID 162003813.

- ^ Schüttler, Hermann (1991). Die Mitglieder des Illuminatenordens, 1776–1787/93. Munich: Ars Una. pp. 48–49, 62–63, 71, 82. ISBN 978-3-89391-018-2.

- ^ Will Durant (1967). The Story of Civilization Volume 10: Rousseau and Revolution. Simon&Schuster. p. 607.

- ^ "Goethite Mineral Data". webmineral.com. Archived from the original on 15 August 2018. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ Dahlin, Bo (22 June 2017). Rudolf Steiner: The Relevance of Waldorf Education. Springer. p. 45. ISBN 978-3-319-58907-7.

It is known —but seldom paid much attention to— that Goethe's natural studies had some influence on Hegel's philosophy.

- ^ Rockmore, Tom (3 May 2016). German Idealism as Constructivism. University of Chicago Press. p. 131. ISBN 978-0-226-34990-9.

Goethe's view attracted interest at the time; someone else influenced by Goethe is Schopenhauer.

- ^ Assiter, Alison (29 April 2015). Kierkegaard, Eve and Metaphors of Birth. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 126. ISBN 978-1-78348-326-6.

Carl Linnaeus, the botanist, physician, and zoologist, who laid the foundation for modern biological naming, was a major influence on Goethe. The latter, a well-known influence on Kierkegaard, writes of Linnaeus, [...]

- ^ Murphy, Tim (18 October 2001). Nietzsche, Metaphor, Religion. SUNY Press. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-7914-5087-1.

No one would deny that Goethe influenced Nietzsche, but it is important to understand that relationship in very specific terms.

- ^ Luft, Sebastian (2015). The Space of Culture: Towards a Neo-Kantian Philosophy of Culture (Cohen, Natorp, and Cassirer). Oxford University Press. p. 124. ISBN 978-0-19-873884-8.

Goethe influenced Cassirer in a crucial aspect of his philosophy of the symbolic.

- ^ Bishop, Paul (13 July 2020). Reading Goethe at Midlife: Ancient Wisdom, German Classicism, and Jung. Chiron Publications. p. 198. ISBN 978-1-63051-860-8.

Goethe's influence on Jung was profound and far-reaching.

- ^ Nietzsche, Friedrich: The Portable Nietzsche. (New York: The Viking Press, 1954)

- ^ Friedenthal, Richard (2010). Goethe: His Life & Times. Transaction Publishers. p. 389.

- ^ a b Broers, Michael (2014). Europe Under Napoleon. I.B. Tauris. p. 4.

- ^ Swales, Martin (1987). Goethe: The Sorrows of Young Werther. CUP Archive. p. 100.

- ^ Merseburger, Peter (2013). Mythos Weimar: Zwischen Geist und Macht. Pantheon. pp. 132–133.

- ^ Ferber, Michael (2008). A Companion to European Romanticism. John Wiley & Sons. p. 450.

- ^ a b c Gillespie, Gerald Ernest Paul; Engel, Manfred (2008). Romantic Prose Fiction. John Benjamins Publishing. p. 44.

- ^ Wood, Dennis (2002). Benjamin Constant: A Biography. Routledge. p. 185.

- ^ Sorensen, David R. (2004). "Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von". In Cumming, Mark (ed.). The Carlyle Encyclopedia. Madison and Teaneck, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. p. 200. ISBN 9780838637920.

- ^ Tennyson, G. B. (1973). "The Carlyles". In Clubbe, John (ed.). Victorian Prose: A Guide to Research. New York: The Modern Language Association of America. p. 65. ISBN 9780873522502.

- ^ a b Röder-Bolton, Gerlinde (1998). George Eliot and Goethe: An Elective Affinity. Rodopi. pp. 3–8.

- ^ Wagner, Albert Malte (1939). "Goethe, Carlyle, Nietzsche and the German Middle Class". Monatshefte für Deutschen Unterricht. 31 (4): 162. JSTOR 30169550. Archived from the original on 18 June 2022. Retrieved 18 June 2022.

- ^ Connell, W.F. (2002). The Educational Thought and Influence of Matthew Arnold. Routledge. p. 34.

- ^ a b Mundt, Hannelore (2004). Understanding Thomas Mann. Univ of South Carolina Press. pp. 110–111.

- ^ "The literary estate of Goethe in the Goethe and Schiller Archives". UNESCO Memory of the World Programme. Archived from the original on 29 September 2017. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- ^ Richter, Simon J. (2007). Goethe Yearbook 14. Harvard University Press. pp. 113–114.

- ^ Amrine, F.R.; Zucker, Francis J. (2012). Goethe and the Sciences: A Reappraisal. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 232.

- ^ Scientific Studies, Suhrkamp ed., vol. 12, p. 121; trans. Douglas Miller

- ^ a b c Roach, Joseph R. (1993). The Player's Passion: Studies in the Science of Acting. University of Michigan Press. pp. 165–166.

- ^ a b c Fellows, Otis Edward (1981). Diderot Studies. Librairie Droz. pp. 392–394.

- ^ Seifer, Marc J. (1998). Wizard: The Life and Times of Nikola Tesla: Biography of a Genius. Citadel Press. pp. 22, 308. ISBN 978-0-8065-1960-9. Archived from the original on 4 April 2023. Retrieved 8 January 2023.

Sources

[edit]- Mercer-Taylor, Peter (2000). The Life of Mendelssohn. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-63972-9.

- Todd, R. Larry (2003). Mendelssohn – A Life in Music. Oxford, England; New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-511043-2.

- Unseld, Siegfried (1996). Goethe and His Publishers. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226841908.

Further reading

[edit]- Bell Matthew. 1994. Goethe's Naturalistic Anthropology : Man and Other Plants. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Browning, Oscar (1879). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. X (9th ed.).

- Calder, Angus (1983), '"Scott & Goethe: Romanticism and Classicism", in Hearn, Sheila G. (ed.), Cencrastus No. 13, Summer 1983, pp. 25–28, ISSN 0264-0856

- Von Gronicka, André. 1968. The Russian Image of Goethe. Volume 1 Goethe in Russian Literature of the First Half of the Nineteenth Century. Philadelphia Pa: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Von Gronicka, Andrè. 1985 The Russian Image of Goethe. Volume 2 Goethe in Russian Literature of the Second Half of the Nineteenth Century. Philadelphia Pa: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Hatfield Henry Caraway. 1963. Goethe: A Critical Introduction. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Jane K. n.d. Goethe's Allegories of Identity. Philadelphia Pa: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Maertz Gregory. 2017. Literature and the Cult of Personality: Essays on Goethe and His Influence. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Robertson, John George; Phillips, Walter Alison (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 12 (11th ed.). pp. 182–189.

- Robertson, Ritchie. 2016. Goethe: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Santayana, George (1910). "Goethe's Faust". Harvard Studies in Comparative Literature, Volume 1: Three Philosophical Poets: Lucretius, Dante, and Goethe, Critical Edition. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. pp. 139–202. Retrieved 22 September 2022.

- Viëtor, Karl 1950. Bayard Quincy Morgan, trans. Goethe the Thinker. Cambridge Mass: Harvard University Press.

External links

[edit]This article's use of external links may not follow Wikipedia's policies or guidelines. (March 2024) |

- Goethe on In Our Time at the BBC

- "Goethe and the Science of the Enlightenment" In Our Time, BBC Radio 4 discussion with Nicholas Boyle and Simon Schaffer (10 February 2000).

- "Works by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe". Zeno.org (in German).

- At the Linda Hall Library, Goethe's:

- Works by and about Johann Wolfgang von Goethe in University Library JCS Frankfurt am Main: Digital Collections Judaica

- Goethe in English at Poems Found in Translation

- Poems of Goethe set to music, lieder.net

- Goethe Quotes: New English translations and German originals

Electronic editions

[edit]- Works by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe at Faded Page (Canada)

- Free scores of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe's texts in the Choral Public Domain Library (ChoralWiki)

- Works by or about Johann Wolfgang von Goethe at the Internet Archive

- Works by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Works by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe in eBook form at Standard Ebooks

- Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

- 1749 births

- 1832 deaths

- 18th-century German educators

- 18th-century essayists

- 18th-century German civil servants

- 18th-century German dramatists and playwrights

- 18th-century German male writers

- 18th-century German novelists

- 18th-century German philosophers

- 18th-century German poets

- 18th-century historians

- 18th-century travel writers

- 19th-century German educators

- 19th-century German essayists

- German male essayists

- 19th-century German civil servants

- 19th-century German diplomats

- 19th-century German dramatists and playwrights

- 19th-century German male writers

- 19th-century German non-fiction writers

- 19th-century German novelists

- 19th-century German philosophers

- 19th-century German poets

- 19th-century historians

- 19th-century travel writers

- Color scientists

- Enlightenment philosophers

- Epic poets

- Epigrammatists

- Fabulists

- Freethought writers

- German autobiographers

- German bibliophiles

- German diplomats

- German ethicists

- German Freemasons

- 18th-century German historians

- German librarians

- German male dramatists and playwrights

- German male non-fiction writers

- German male novelists

- German male poets

- German travel writers

- German untitled nobility

- Leipzig University alumni

- Literacy and society theorists

- Literary theorists

- Members of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences

- Members of the Göttingen Academy of Sciences and Humanities

- Natural philosophers

- Pantheists

- People from Weimar

- German philosophers of art

- German philosophers of culture

- German philosophers of education

- German philosophers of history

- German philosophers of language

- Philosophers of linguistics

- Philosophers of literature

- German philosophers of science

- Philosophers of sexuality

- Philosophers of social science

- Philosophy writers

- German political philosophers

- Scientists from Weimar

- Romantic poets

- Sturm und Drang

- Theorists on Western civilization

- University of Strasbourg alumni

- Writers about activism and social change

- Writers from Frankfurt

- Writers from Weimar

- 19th-century German historians

- Mythopoeic writers

- German people of Turkish descent