California High-Speed Rail

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

| California High-Speed Rail | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

San Joaquin River Viaduct under construction in 2019 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Overview | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Owner | California High-Speed Rail Authority | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

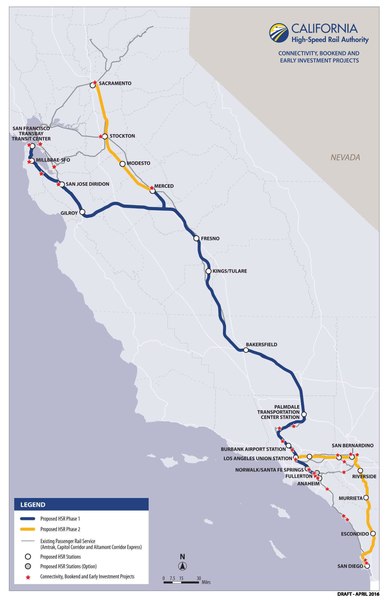

| Area served | Phase 1 Initial Operating Segment (now under construction): San Joaquin Valley Phase 1 future extensions: north to San Francisco Bay Area south to Greater Los Angeles Phase 2 future extensions: north to Sacramento, California south to San Diego, California | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Locale | California, United States | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Transit type | High-speed rail | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Number of stations | 4 (Phase 1 Initial Operating Segment) 21 (entire completed system) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chief executive | Brian P. Kelly | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Website | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Operation | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Operation will start | 2029 (Initial Operating Segment) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Operator(s) | DB International USA | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Technical | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| System length | c. 171 mi (275 km) (central leg) c. 520 mi (840 km) (Phase 1) c. 800 mi (1,300 km) (proposed including Phase 2)[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| No. of tracks | 2 (4 in stations) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8+1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrification | 25 kV 60 Hz AC overhead line[2][3] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Top speed | 220 mph (350 km/h) maximum 110 mph (180 km/h) San Francisco–Gilroy[4] & Los Angeles–Anaheim[5] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

California High-Speed Rail (also known as CAHSR or CHSR) is a publicly funded high-speed rail system currently under construction in California in the United States. Planning for the project began in 1996, when the California Legislature and Governor Pete Wilson established the California High-Speed Rail Authority, tasking it with creating a plan for the system and presenting it to the voters of the state for approval. In 2008, voters approved Proposition 1A, which authorized bonds to begin implementation, established a route connecting all the major population centers of the state, and set other requirements.

In the major metropolitan areas in the north and south of the state the HSR trains will operate in a "blended system" (sharing upgraded tracks, power, train control, and stations with local commuter rail). The first of the pure HSR segments, the Initial Operating Segment (IOS), is planned to begin operations in the Central Valley in 2029. Extending the IOS to connect to the north and south metropolitan segments is dependent on future funding, so their timing is uncertain.

Maximum train speeds will be about 220 miles per hour (350 km/h) in the dedicated HSR segments, and about 110 miles per hour (180 km/h) in the blended segments. Once the full Phase 1 system opens, the non-stop trains will have a maximum trip time of 2 hours and 40 minutes between San Francisco and Los Angeles, which are about 350 miles (560 km) apart by air.

The high-speed rail system is anticipated to provide environmental benefits (reducing pollution and carbon emissions), traffic benefits (reducing vehicular traffic and air travel congestion), and economic benefits (especially in the Central Valley). The implementation of the project has been controversial, due to its selected route, construction delays, cost over-runs, delays in land acquisition, and a lack of funding to finish the entire system.

Current status and plans

Phase 1 runs from San Francisco to Los Angeles and Anaheim, and is being implemented in sections. In the Central Valley the Authority is in the process of constructing a self-sustaining Initial Operating Segment (IOS) running from Merced to Bakersfield – a distance of about 171 miles (280 km). This segment will connect to other transit systems for passenger transfers. The Authority indicates the IOS will go into service before 2030. "Bookend" investments are also being made in the Bay Area and Southern California upgrading existing infrastructure to be able to support eventual HSR service.

After completing the IOS, the Authority plans to advance construction on the Merced-San Jose segment, linking the Central Valley to the tracks of the Caltrain System. This will allow HSR trainsets to run from San Francisco to Bakersfield. Funding for construction of this segment has yet to be secured.

Phase 1 must be operational before Phase 2. Phase 2 will extend the HSR system north to Sacramento and south to San Diego. These extensions are still in the preliminary planning stages.

The California High-Speed Rail Peer Review Group has noted a number of concerns about the progress of the project, including issues acquiring property in the Central Valley, delays due to lawsuits, an early lack of requisite management experience, and weak legislative oversight. Inflation has also become a major concern due to the disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and the War in Ukraine (2022).[6]

The project will require legislative action, so the issues raised by the Peer Review Group and the project consultant (KPMG) will help the legislature select from the Board's proposed plans or other alternatives.

2022 Business Plan

The 2022 Business Plan includes information regarding the project's status, goals, and activities. In order to make an effective, self-supporting Initial Operating Segment, and due to financial constraints, the Authority is focusing on five actions:

- Adding the additional 52 miles to create a 171-mile (275 km) HSR-operable segment between Merced and Bakersfield. Advanced design contracts have been awarded for both extensions, and work on route acquisition and construction will be performed as funding becomes available. The Merced station will provide a transfer point to the Altamont Corridor Express (ACE) and San Joaquins (Amtrak) rail routes to Sacramento and the Bay Area (San Francisco and Oakland) as well as local buses. The Bakersfield station will have a transfer to Thruway Bus Service for travel to Southern California.

- Procuring a Track and Systems contract for the initial 119 miles of right-of-way. When track and systems work along the initial 119 miles is completed, there will be a two-year period of testing HSR trainsets, trackage, and control systems while construction proceeds on the Merced and Bakersfield extensions. The Authority plans to restructure and re-issue the Track and Systems procurement in 2023.[7]

- Completing environmental review approvals for the entire 500-mile (800 km) Phase 1 system by the end of 2024, so that all segments in Phase 1 will be ready to be constructed when funding becomes available. The routes from San Francisco to Palmdale and from Burbank to Los Angeles have been approved. Palmdale to Burbank is expected to be approved in 2023, and Los Angeles to Anaheim in 2024.[8]

- Continuing to advance "bookend" investments. In Northern California, these include electrification of Caltrain and grade separations between San Francisco and San Jose. The Authority will also be working with Union Pacific Railroad to extend electrification to Gilroy. In Southern California, these include phase A of Link Union Station, which through-tracks LA Union Station, and other improvements such as early grade separations in the Burbank-to-Los Angeles shared corridor and the Rosecrans-Marquardt grade separation. These investments provide immediate benefits in the San Francisco and Los Angeles areas, while also readying those transit systems for eventual shared use by HSR trainsets.

- Opening the Initial Operating Segment to public use before 2030. The contracted Early Train Operator (ETO) selected to run the system is DB E.C.O. North America Inc. The IOS will run from Merced to Bakersfield and have five stations (Merced, Madera, Fresno, Kings/Tulare, and Bakersfield).

Also, a major addition to the development and operation plan is a new emphasis on risk analysis and risk mitigation (with these now integrated into the formal authorization process), and contingency reserves are being increased. Revenue and expense projections indicate that constructing an operable 171-mile (275 km) segment is feasible.

A preview of the 2023 Project Update Report indicates it will include:

- A new funding strategy.

- An updated program baseline budget and schedule.

- Design of the IOS extensions and the Merced and Bakersfield stations.

- Completing the remaining Phase 1 environmental clearances.

- New ridership and revenue forecasts presented by the Early Train Operator (DB E.C.O. North America Inc.).

- Updated capital costs to complete Phase 1.

Financial status

As of September 2022, the Authority's plans indicated[9]: 59 $23.4 billion in identified funding through 2030, with a budget of $17.9 billion for Central Valley construction (about 119 miles (192 km)), design work for the Merced and Bakersfield extensions, the "bookend" projects now underway in the northern and southern metropolitan areas, completing the environmental clearances needed for all of Phase 1, and $4.6 to $6.0 billion for double-trackage and trainsets for the IOS.[9] As of November 2022, there is an additional $8 billion in funding sought via grants from the federal government for:

- Construction and land acquisition to advance the extension south to Bakersfield,

- Purchase of the trainsets needed for the Initial Operating Segment operations,

- Design of the Merced and Bakersfield extensions,

- Construction of the initial four HSR stations, and

- Double-tracking the initial 119 miles.[10]

Per the 2022 Business Plan, the expected new funding will be budgeted to:

- "Deliver an electrified two-track initial operating segment connecting Merced, Fresno and Bakersfield as soon as possible.

- Invest statewide to advance engineering and design work as every project section is environmentally cleared.

- Leverage new federal and state funds for targeted statewide investments.

- Develop a funding strategy to extend high-speed rail beyond the Central Valley and to the Bay Area as soon as possible."[11]: 3

Cost estimates to complete the entire Phase 1 system[9]: 79 range from a low-estimate of $76.7 billion, to a mid-estimate of $92-94 billion, to a high-estimate of $113 billion. (A major unknown is the cost of tunneling, which will not be known until exploratory field studies are done.) It is expected that new figures will be provided in the 2023 Project Update Report in March 2023.

Construction status

Three separate construction packages are underway, which together include a total of 119 miles of guideway and 93 structures. As of September 2022, 48.6 miles of guideway are complete, 38.4 are underway, and 32 remain to be started; of concrete structures, 33 are complete, 35 are underway, and 25 remain to be started.[12]: 8

The groundbreaking ceremony for CAHSR was held on January 6, 2015 (in Fresno, California) in CP1.

- CP1 comprises 32 miles (51 km) from Avenue 17 north of Madera to East American Avenue south of Fresno. It includes 12 grade separations, two viaducts, one tunnel, a major river crossing over the San Joaquin River, and the realignment of State Route 99. The contractor is the joint venture of Tutor-Perini/Zachry/Parsons.[13] The design-build contract was signed August 16, 2013. Construction is forecast to be completed by Dec. 31, 2025.[14]: 13

- CP2-3 comprises 65 miles (105 km) from East American Avenue south of Fresno to 1 mile (1.6 km) north of the Tulare / Kern County border. It includes approximately 36 grade separations, viaducts, underpasses, and overpasses. The contractor is the joint venture of Dragados USA/Flatiron Construction.[15] The design-build contract was signed June 10, 2015. Construction is forecast to be completed by Mar. 21, 2026.[16]: 22

- CP4 comprises 22 miles (35 km) adjoining the end of CP2-3 to the intersection of Poplar / Madera Avenue northwest of Shafter. It includes at-grade embankments, retained-fill over-crossings, viaducts, aerial sections of the high-speed rail alignment, and the relocation of four miles of existing Burlington Northern Santa Fe (BNSF) tracks. The contractor is California Rail Builders, a joint venture of Ferrovial-Agroman West, LLC and Griffith Company.[17] The design-build contract was signed February 29, 2016. Construction is forecast to be completed by Mar. 21, 2023.[18]: 31

For the Bakersfield and Merced extensions (52 additional miles (84 km)), advanced design work, right-of-way mapping, and identification of utility relocation work is underway. For the Heavy Maintenance Facility (HMF), the planning and approval process is proceeding.[19]: 42

Route and stations

The project aims to connect California's major metropolitan areas together, and link to their local commuter systems. It will be built in two major phases. Phase 1 connects San Francisco and the Bay Area through the San Joaquin Valley (the southern part of the Central Valley) to Anaheim in the Greater Los Angeles area, a distance of about 500 miles (800 km). Phase 2 extends the north end of the Central Valley section up to Sacramento, and extends the Los Angeles section in the south through the Inland Empire down to San Diego at the bottom of the state, for a total system length of about 800 miles (1,290 km).

The number of stations on the completed system was limited by Proposition 1A to 24. Not all station locations have been decided. At the start of operations along the Initial Operating Segment there will be 5 stations.

Route time/speed requirements

Proposition 1A[20] also set the maximum nonstop travel times between certain destinations on the system:

- San Francisco–San Jose: 30 minutes; this would require about 100 miles per hour (160 km/h)

- San Jose–Los Angeles: 2 hours, 10 minutes; this would require about 200 miles per hour (320 km/h)

- San Francisco–Los Angeles Union Station: 2 hours, 40 minutes

- San Diego–Los Angeles: 1 hour, 20 minutes

- Inland Empire–Los Angeles: 30 minutes

- Sacramento–Los Angeles: 2 hours, 20 minutes

In addition, the achievable operating headway between successive trains must be less than 5 minutes.[20]

Trains (rolling stock)

Acquisition

In January 2015, the Authority issued a request for proposal (RFP) for complete trainsets. The proposals received will be reviewed so that acceptable bidders can be selected, and then requests for bids will be sent out.

In February 2015, ten companies formally expressed interest in producing trainsets for the system: Alstom, AnsaldoBreda (now Hitachi Rail Italy), Bombardier Transportation, CSR, Hyundai Rotem, Kawasaki Rail Car, Siemens, Sun Group U.S.A. partnered with CNR Tangshan, and Talgo. CSR merged with CNR in June 2015 to form CRRC Corporation, bringing the number of companies down to eight.[21] Bombardier Transportation completed its merge with Alstom by January 2021.[22]

Due to company acquisitions and mergers, the number of companies now qualified for the tender is seven. The qualified companies are Alstom, Siemens Mobility, Talgo, Hitachi Rail Italy, CRRC, Hyundai Rotem, and Kawasaki Rail Car.

An additional factor for the selection of a model is the Buy America regulation. The Federal Railroad Administration granted a waiver for two prototypes to be manufactured off-shore. The remaining trainsets would need to be built according to the rules.[23] This requirement was mentioned as a significant reason that Chinese manufacturers dropped out of the Brightline West (then known as XpressWest) project with similar technical trainset specifications.[24]

Included in a May 2022 grant request to the Biden administration is a request for funds to purchase six HSR trainsets.[25] It is estimated that for the entire Phase 1 system up to 95 trainsets might be required.[26]

Station-sharing issue

The CAHSR trains will use a different standard than Caltrain for their floor height above the rails. The CAHSR trains have a floor height of 50.5 in (128 cm) above the rails, which is significantly higher than the 22 in (56 cm) floors of Caltrain's commuter trainsets. To resolve this issue, Caltrain is procuring new Stadler KISS EMUs that have doors at both heights.[3][27] Each station provides either one platform height or the other. Only a few of the stations will service both trainsets. Thus, in the Bay Area most of the stations on the line will be used exclusively by Caltrain.

HSR passenger line operations

Request for Qualifications

In April 2017, the CHSRA announced it had received five responses to its request for qualifications for the contract to assist with the development and management of the initial phase of the high-speed line and be the initial operator.[28][29]

- China HSR ETO Consortium: China Railway International, Beijing Railway Administration, China Railway Eryuan Engineering Group, China Railway Corporation

- DB International US: DB International USA, Deutsche Bahn, Alternate Concepts, HDR

- FS First Rail Group: Ferrovie dello Stato Italiane, FirstGroup, Trenitalia, Rete Ferroviaria Italiana, Centostazioni, Italferr, McKinsey & Company

- Renfe: Renfe Operadora, Globalvia Inversiones, Administrador de Infraestructuras Ferroviarias

- Stagecoach Group: Stagecoach Group, Coach USA

Selected Early Train Operator

In October 2017, the California High-Speed Rail Authority announced that DB E.C.O. North America Inc (formerly known as DB Engineering & Consulting USA Inc.) had been chosen as the Early Train Operator for initial operations.[30] This decision came after a Request for Qualifications was put out by the Authority looking for well established groups able to provide operational guidance for the future system once opened.

Services provided by DB International US are:

- Project Management

- Ridership and passenger revenue forecasts

- Preferred revenue collection systems

- Rolling stock fleet size and interior layout

- Service planning and scheduling

- O&M cost forecasting

- Station design & operations

- Optimization of life cycle costs

- Procurements

- Fare integration and Interoperability

- Safety and security

- Operations control/dispatching responsibilities

- Maximizing system revenues

- Marketing and branding

History

This project already has a long history. Topics included in the main History page (the link shown above) include the early history (before 2015), discussion of HSR alternatives, legislation, financing, construction, and legal challenges.

Legislative

In 1996, the California High-Speed Rail Authority (CHSRA) was established to begin formal planning in preparation for a ballot measure in 1998 or 2000.[31][32]

In 2008, California voters approved Proposition 1A to construct the initial segment of the high-speed rail network, and issued $9 billion in bonds to begin its construction.[33] It also set certain requirements for the project:[34]

- Established the basic route linking the major population centers

- Minimum 200 miles per hour (320 km/h) where conditions permit

- Maximum of 24 stations on the system

- Maximum travel times between certain points

- Financially self-sustaining (operation and maintenance costs fully covered by revenue)

The proposition also authorized an additional $950 million for improvements on local commuter systems, which will serve as feeder systems to the high-speed rail system.

In June 2014, state legislators and Governor Jerry Brown agreed to apportion the state's annual cap and trade funds so that 25% goes to high-speed rail as an ongoing source of funds.[35]

Legal

In 2014, the CHSRA was challenged on its compliance with its statutory obligations under Proposition 1A (John Tos, Aaron Fukuda, and the Kings County Board of Supervisors v. California High-Speed Rail Authority). In November 2021 a circuit court ruled against the plaintiffs, and effectively ended this litigation.[36]

On December 15, 2014, the federal Surface Transportation Board determined (using well-understood preemption rules) that its approval of the HSR project in August "categorically preexempts" lawsuits filed under the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA). This determination is still being tested in the California courts in a similar case, Friends of Eel River v. North Coast Railroad Authority.[37][needs update]

In February 2022, Hollywood Burbank Airport sued the Authority over its approval of the draft EIR for that section of the high-speed railway.[38]

Economic and environmental impacts

In addition to the direct reduction in travel times the HSR project will produce, there are other anticipated benefits, both general to the state, to the regions the train will pass through, and to the areas immediately around the train stations.

Initial Operating Segment projections

The 2022 Business Plan[39]: 25 listed these estimated benefits which will come from the Initial Operating Segment (Merced to Bakersfield):

- Travel time will be significantly shorted, and travel will be more reliable. Car travel time is 2.5 hrs. one-way. The Amtrak San Joaquin takes 3 hrs. at best, but there are only 7 round-trips each day, and intervening freight service makes service unreliable. CAHSR is estimated to reduce travel time by up to 100 minutes, and 18 reliable round-trips are anticipated each day.

- With better transit inside the Central Valley, transit to the Bay Area and Sacramento as well as Southern California will improve significantly.

- Rail passenger trips over the same route are projected to nearly double, from 4.8 million annual riders to 8.8 million riders.

- Annual vehicle miles traveled will be reduced by 284 million, reducing road congestion.

- Greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions will be reduced by 50.6 thousand metric tons, equivalent to emissions from 10,874 passenger vehicles driven for one year.

- An additional $117.2 million in passenger revenues.

- More than 200,000 job-years due to the line's operation and community effects.

Cumulative economic impact estimates

The 2021 Economic Impact Factsheet estimated that as of June 2021, the statewide economic benefits of the project included 64,400–70,500 job-years of employment, $4.8–$5.2 billion in labor employment, and $12.7–13.7 billion in economic output, and that as of February 2022, 699 small businesses were involved in the project.[40]

Carbon emissions calulator

According to a 2022 Carbon Footprint Calculator on the Authority website,[41] the environmental benefits of the system include CO2e/GHG emissions savings per passenger round-trip of:

- 142 pounds on the Merced-Bakersfield Initial Operating Segment

- 349 pounds for San Francisco-Los Angeles

- 303 pounds for San Jose-Burbank

- 389 pounds for San Francisco-Anaheim

- 337 pounds for San Francisco-Burbank

The Authority estimates that by 2040, the system could carry 50 million riders per year, and that at full operation, the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions will be equivalent to removing 400,000 vehicles off the road.[42]

Regional benefits

In its 67-page ruling in May 2015, the federal Surface Transportation Board noted: "The current transportation system in the San Joaquin Valley region has not kept pace with the increase in population, economic activity, and tourism. ... The interstate highway system, commercial airports, and conventional passenger rail systems serving the intercity market are operating at or near capacity and would require large public investments for maintenance and expansion to meet existing demand and future growth over the next 25 years or beyond."[43] Thus, the Board sees the HSR system as providing valuable benefits to the region's transportation needs.

The San Joaquin Valley is also one of the poorest areas of the state. For example, the unemployment rate near the end of 2014 in Fresno County was 2.2% higher than the statewide average.[44] And, of the five poorest metro areas in the country, three are in the Central Valley.[45] The HSR system has the potential to significantly improve this region and its economy. A large January 2015 report to the CHSRA examined this issue.[46]

In addition to jobs and income levels in general, the presence of HSR is expected to benefit the growth in the cities around the HSR stations. It is anticipated that this will help increase population density in those cities and reduce "development sprawl" out into surrounding farmlands.[47]

Negatively-affected local communities

There have also been some reported negative impacts from the project's land acquisitions and constructions. Thus far, in the Phase 1 construction the project displaced or adversely affected immigrants (Mexican, Cambodian, and Japanese), homeless outreach organizations, homeless shelters, firefighters, nonprofits working with welfare recipients, thrift stores, and disadvantaged communities such as Wasco.[48][49]

Peer review, public opinion, and criticism

There are two types of review and criticism noted here: the legally established "peer review" process that the California legislature established for an independent check on the Authority's planning and implementation efforts,[50] and public criticisms by groups, individuals, public agencies, and elected officials.

At the February 2015 conference Bold Bets: California on the Move?, hosted by The Atlantic magazine and Siemens, Dan Richard, the chair of the Authority, warned that not all issues facing the HSR system had been resolved.[51]

Peer Review Group

The California Legislature established the California High-Speed Rail Peer Review Group to provide independent analysis of the Authority's planning and implementation efforts. Their documents are submitted to the Legislature as needed.

The April 1, 2022 report[52] noted a number of positive factors:

- Improved prospects for federal funding with the Biden Administration.

- Disruptions and impacts caused by COVID-19, the war in Ukraine, and inflation are all noted but being dealt with.

- Significant progress has been made on the necessary environmental clearances.

- Greater attention is being given to local transit connectivity and local economic impacts.

- Major improvements have been made to project management and risk mitigation.

However, there were also a number of significant concerns noted:

- The total level of uncertainty has likely increased due to effects of COVID-19 and inflation.

- Prior experience with cost increases and scheduling delays raises some uncertainties about future performance. Cost increases have been over 86%, average delays have been 118%, only 90% of ordinary real estate parcel needed have been acquired, only 63% of railroad parcels have been acquired, and only 65% of utility parcels have been acquired.

- Some of the cost estimates presented were out of date, but expected to be updated in the 2023 Project Update Report.

- Major components of the project (representing over half its cost) have no bidding or contract management experience. Thus, estimates for these are clearly suspect.

- There are critical issues regarding management and legal issues with other agencies for the operation of the system which remain unresolved. (There are a number of these listed, as well as unknown long term impacts of COVID-19 on ridership and inflation.)

- Adequate legislative oversight is lacking.

- Per the report, "[O]verall project funding remains inadequate and unstable making effective management extremely difficult. In addition, the Authority has no clear guidance from the Legislature on the next steps in the project."

- "Even with a realistic share of new Federal funding, the project cannot get outside the Central Valley without added state or local funding from sources not yet identified."

Professional studies

Study #1. Eric Eidlin, an employee of the Federal Transit Administration (Region 9, San Francisco), wrote a study in 2015 funded by the German Marshall Fund of the United States comparing the structural differences of two HSR European systems and their historical development with California's HSR system.[53] He also focused on the issue of station siting, design, use, and impact on the surrounding community. From this, he developed ten recommendations for CAHSRA. Among these are:

- Develop bold, long-term visions for the HSR corridors and stations.

- Where possible, site HSR stations in central city locations.

- In rural areas, emphasize train speed; in urban areas, emphasize transit connectivity.

- Plan for and encourage the non-transit roles of the HSR stations.

Eidlin's study also notes that in California there has been debate on the disadvantages of the proposed blended service in the urban areas of San Francisco and Los Angeles, including reduced speeds, more operating restraints, and complicated track-sharing agreements. There are some inherent advantages in blended systems that have not received much attention: shorter transfer distances for passengers, and reduced impacts on the neighborhoods. Blended systems are in use in Europe.[54]

Study #2. A 202-page study by A. Loukaitou-Sideris, D. Peters, and W. Wei of the Mineta Transportation Institute at San Jose State University in 2015 compared examples of "blended systems" in Spain and Germany where conventional and high-speed rail (HSR) services either used the same tracks over a portion of track or at a specific station.[55] The study found that blended systems were cheaper to build, required less space, and provided easy transfers between different modes of transportation, but resulted in lower system capacity (due to greater separation distances required when combining HSR and conventional traffic), were often not possible to properly implement in urban areas due to the additional land area requirements for passing sidings, resulted in additional challenges in operations, and caused frequent delays.[56]

Think tank studies

Right-wing think tanks such as the Reason Foundation,[57] the Howard Jarvis Taxpayers Association, and Citizens Against Government Waste published a study which they named the "Due Diligence Report" (2008) critiquing the project.[58] In 2013, the Reason Foundation published an "Updated Due Diligence Report" (2013).[59] Key elements of the updated critique include:

- operating train speed higher than any existing HSR system at the time

- unrealistic ridership projections

- increasing costs

- no clear funding plan

- incorrect assumptions regarding HSR alternatives

- increasing fare projections

This 2013 critique was based on the 2012 Business Plan. Although the 2012 Business Plan has been superseded by the 2022 Business Plan, the critique does include the Blended System approach using commuter tracks in SF and LA.

James Fallows in The Atlantic magazine summarized public criticism thus, "It will cost too much, take too long, use up too much land, go to the wrong places, and in the end won't be fast or convenient enough to do that much good anyway."[60]

Public opinion

In March 2016 the Public Policy Institute of California (PPIC) Statewide Survey indicated that 52% of Californians support the project, while 63% of Californians think the project is either "very important" or "somewhat important" for California's economy and quality of life. Support varies by location (with the San Francisco Bay Area the highest at 63%, and lowest in Orange/San Diego at 47%), by race (Asians 66%, Latinos 58%, Whites 44%, and Blacks 42%), by age (declining sharply with increasing age), and by political orientation (Democrats 59%, independents 47%, and Republicans 29%).[61] Dan Richard, chair of the Authority, said in an interview with James Fallows that he believes approval levels will increase when people can start seeing progress, and trains start running.[51]

In April 2022 UC Berkeley's Institute of Government Studies released a survey of registered voters that found 56% supported continuing the high-speed rail project even if "its operations only extend from Bakersfield to Merced in the Central Valley by the year 2030 and to the Bay Area by the year 2033."[62] Approval continued to vary by political affiliation with 73% of Democrats backing the project versus 25% of Republicans.

Las Vegas HSR project

Brightline West (formerly Desert Xpress and XpressWest) is a project that since 2007 has been planning to build a high-speed rail line between Southern California and Las Vegas, Nevada, part of the "Southwest Rail Network" they hope to create. The rail line would begin in Las Vegas and cross the Mojave Desert stopping 5 miles (8.0 km) outside of Victorville, California and eventually terminating in Palmdale, California (where it would connect with CAHSR and Metrolink). This route would total about 230 miles (370 km). A second branch into Rancho Cucamonga (in the Inland Empire) is also planned.

In 2012, Lisa Marie Alley, speaking for CAHSRA, said that there have been ongoing discussions concerning allowing the trains to use CAHSRA lines to go further into the Los Angeles area, although no commitments have been made as yet. While many approvals have been obtained for the rail line from Victorville to Las Vegas, the section from Palmdale to Victorville has none as yet.[63]

In October 2021, Brightline signed an MOU (Memorandum of Understanding) with California State Transportation Agency (CalSTA), the California Department of Transportation (Caltrans), and the California High-Speed Rail Authority (CAHRSA). "The MOU sets the framework regarding the use of 48 miles within Interstate 15 to be used for Brightline West to connect its planned Victor Valley station and a newly planned station in Rancho Cucamonga." (The Rancho Cucamonga station links to both Metrolink and the Ontario Airport.) This planned HSR extension will bring Brightline West down towards Ontario in the Inland Empire, providing a second branch of their line into Southern California.[64] Brightline has agreed to purchase a 5 acre parcel for their HSR service adjacent to the planned multimodal upgrade to the existing station.[65]

As of November 2022, a start date for construction of Brightline West had yet to be announced.

Further reading

The Authority's documents

The Authority's Business Plan is updated every even year (since 2008). It must be submitted to the Legislature by May 1. It describes the project's goals, financing, and development plans.

The Authority's Update Report is produced every odd year (since 2015). It must be submitted to the Legislature by March 1. The report gives a program-wide summary, as well as information for each project section, in order to clearly describe the project's status.

The Authority's Newsroom provides frequent news releases concerning all aspects of the project.

The Authority's Info Center provides factsheets, regional newsletters, maps, and video simulations of route "fly-overs".

Other documents

The California Peer Review Group produces independent analysis of the project for the state legislature. Its documents are available on its website.

In 2014-2015, James Fallows wrote a series of 17 articles for The Atlantic about the HSR system. The series covered many aspects of the system, criticisms of it, and responses to those criticisms.

References

- ^ California High-Speed Rail Authority. "Implementation Plan" (PDF). pp. 23, 25. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 10, 2008. Retrieved July 17, 2008.

- ^ "TECHNICAL MEMORANDUM: Traction Power 2x25kV Autotransformer Feed Type Electrification System & System Voltages" (PDF). HSR.CA.gov. CHSRA. Retrieved November 3, 2016.

- ^ a b "KISS Double-Decker Electric Multiple Unit EMU for Peninsula Corridor Joint Powers Board (CALTRAIN), California, USA" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 6, 2016. Retrieved October 16, 2016.

- ^ "HSR Q+A: Blended System & Passing Tracks with Boris Lipkin". California High-Speed Rail Authority. 2020. Archived from the original on December 12, 2021. Retrieved October 12, 2020.

- ^ "ES.0 Executive Summary: ES.1 Supplemental Alternatives Analysis Report Results" (PDF). Hsr.ca.gov. Retrieved January 14, 2016.

- ^ Peer Review Group's 2022 report to the state legislature

- ^ https://hsr.ca.gov/2022/10/26/news-release-california-high-speed-rail-authority-to-restructure-track-and-systems-procurement/

- ^ CAHSRA. "Revised Draft Business Plan 2022" (PDF). p. 43.

- ^ a b c "California High-Speed Rail 2022 Business Plan". California High-Speed Rail Authority. September 2022. Retrieved November 6, 2022.

- ^ https://hsr.ca.gov/2022/10/11/news-release-california-high-speed-rail-applies-for-millions-in-new-federal-funds-to-advance-construction-toward-bakersfield/

- ^ https://hsr.ca.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/2022-Business-Plan-FINAL-A11Y.pdf

- ^ https://hsr.ca.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/CVSR-2211-2209-Data-FINAL-V0-A11Y.pdf

- ^ https://www.buildhsr.com/construction_packages/package_1.aspx

- ^ https://hsr.ca.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/CVSR-2211-2209-Data-FINAL-V0-A11Y.pdf

- ^ https://www.buildhsr.com/construction_packages/package_2_3.aspx

- ^ https://hsr.ca.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/CVSR-2211-2209-Data-FINAL-V0-A11Y.pdf

- ^ https://www.buildhsr.com/construction_packages/package_4.aspx

- ^ https://hsr.ca.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/CVSR-2211-2209-Data-FINAL-V0-A11Y.pdf

- ^ https://hsr.ca.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/CVSR-2211-2209-Data-FINAL-V0-A11Y.pdf

- ^ a b "Official Voter Information Guide – Proposition 1A" (PDF). California State Legislature. 2008. Retrieved March 22, 2018.

- ^ "Expressions of Interest Received : HSR 14-30: Request for Expressions of Interest for Tier III Trainsets" (PDF). Hsr.ca.gov. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 2, 2019. Retrieved October 4, 2018.

- ^ "Alstom completes Bombardier Transportation takeover". International Railway Journal. January 29, 2021. Retrieved February 11, 2021.

- ^ "In California's high-speed train efforts, worldwide manufacturers jockey for position". The Fresno Bee. December 27, 2014. Retrieved February 18, 2015.

- ^ "XpressWest, seeking to build U.S. high-speed rail, ends deal with China group". Reuters.com. June 9, 2016.

- ^ https://hsr.ca.gov/2022/05/24/news-release-california-high-speed-rail-authority-pursues-first-major-award-of-new-federal-infrastructure-funds/

- ^ "California High-Speed Rail Blog » HSR Trainset Bids Could Create New Domestic Industry". Cahsrblog.com. February 23, 2015. Archived from the original on February 25, 2015. Retrieved January 14, 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "Rail News - New Caltrain trainsets, Sound Transit rail cars arrive. For Railroad Career Professionals". Progressive Railroading. Retrieved November 29, 2022.

- ^ Operators from five countries interested in California high speed rail contract Railway Gazette International April 6, 2017

- ^ International consortia bid to become California high speed rail early operator Archived April 7, 2017, at the Wayback Machine Global Rail News April 6, 2017

- ^ DB consortium selected for California high speed rail consultancy contract Railway Gazette International October 9, 2017

- ^ "SB 1420 Senate Bill – Chaptered". ca.gov. Retrieved January 14, 2016.

- ^ "California High-Speed Rail Authority". Hsr.ca.gov. Retrieved January 14, 2016.

- ^ "California Proposition 1A, High-Speed Rail Act (2008)". ballotpedia.org. Retrieved January 14, 2016.

- ^ "AB 3034". State of California. Retrieved August 2, 2017.

- ^ "Cap-and-Trade Revenue: Likely Much Higher Than Governor's Budget Assumes". ca.gov. Retrieved January 14, 2016.

- ^ this litigation

- ^ Sheehan, Tim (June 2, 2015). "Farm Bureaus jump into Supreme Court high-speed rail case". The Fresno Bee.

- ^ https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2022-02-25/hollywood-burbank-airport-files-an-environmental-lawsuit-against-california-bullet-train

- ^ https://hsr.ca.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/2022-Business-Plan-FINAL-A11Y.pdf

- ^ The Economic Impact of California High-Speed Rail (PDF) (Report). California High-Speed Rail Authority. 2022. Retrieved November 4, 2022.

- ^ CAHSRA. "Carbon Footprint Calculator".

- ^ CASHRA. "2022 Business Plan".

- ^ Juliet Williams (June 14, 2013). "Key green light for California high-speed rail". Bakersfield.com. Associated Press. Retrieved January 14, 2016.

- ^ "California High Speed Rail Blog » HSR: A Pathway Out of Poverty". Cahsrblog.com. December 17, 2014. Archived from the original on May 24, 2015. Retrieved January 14, 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "California High Speed Rail Blog » The End of the Beginning". Cahsrblog.com. January 6, 2015. Archived from the original on January 9, 2015. Retrieved January 14, 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "California High-Speed Rail and the Central Valley Economy : January 2015" (PDF). Hsr.ca.gov. Retrieved January 14, 2016.

- ^ "High-speed rail and infill: A great marriage for California". sacbee. Retrieved January 14, 2016.

- ^ RALPH VARTABEDIAN (October 29, 2021). "Bullet train leaves a trail of grief among the disadvantaged of the San Joaquin Valley". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved November 11, 2021.

up and down the San Joaquin Valley, the bullet train is hitting hard at people who are already struggling to survive tough economic conditions in one of the poorest regions in the nation

- ^ "Valadao sends letter to High-Speed Rail Authority in defense of Wasco". The Bakersfield Californian. April 8, 2021. Retrieved November 16, 2021.

The construction of the rail has disrupted businesses and homes, worsened air quality, and the abandoned Wasco Farm Labor Housing complex has posed serious health and safety risks

- ^ Official website: California High-Speed Rail Peer Review Group

- ^ a b "Bold Bets: California on the Move?". The Atlantic. February 25, 2015.

Video of event

- ^ California High-Speed Rail Peer Review Group. "April 2022 Report" (PDF).

- ^ Eidlin, Eric (June 2015). "Making the Most of High-Speed Rail in California: Lessons from France and Germany".

- ^ "Blended Service". Midwesthsr.org. June 7, 2013. Retrieved October 4, 2018.

- ^ "Promoting Intermodal Connectivity at California's High-Speed Rail Stations" (PDF). Hsr.ca.gov. November 8, 2017. Retrieved January 14, 2021.

- ^ "Promoting Intermodal Connectivity at California's High-Speed Rail Stations" (PDF). Hsr.ca.gov. November 8, 2017. p. 2. Retrieved January 14, 2021.

- ^ Stewart, James B. (June 14, 2012). "How Broccoli Landed on Supreme Court Menu". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 28, 2022.

- ^ "The California High Speed Rail Proposal: A Due Diligence Report" (PDF). Hsr.ca.gov. Retrieved January 14, 2016.

- ^ "An Updated Due Diligence Report" (PDF). Hsr.ca.gov. Retrieved January 14, 2016.

- ^ Fallows, James (July 11, 2014). "California High-Speed Rail – the Critics' Case". The Atlantic.

- ^ "Californians & Their Government" (PDF). Ppic.org. p. 20. Retrieved October 4, 2018.

- ^ Mark DiCamillo (2022). Release #2022-08: Voters offer a wide range of issues they’d like the state to address (Report). UC Berkeley Institute of Governmental Studies. Retrieved November 4, 2022.

- ^ Makien, Julie (September 17, 2015). "A high-speed rail from L.A. to Las Vegas? China says it's partnering with U.S. to build". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 6, 2012. Retrieved September 19, 2015.

- ^ https://www.gobrightline.com/press-room/brightline-west-track-rancho-cucamonga

- ^ https://www.sbsun.com/2022/10/27/rancho-cucamonga-sbcta-approve-sale-of-5-acres-for-high-speed-rail-station/

External links

- Wikipedia articles needing copy edit from July 2022

- California High-Speed Rail

- Deutsche Bahn

- Electric railways in California

- High-speed railway lines in the United States

- Passenger rail transportation in California

- Proposed railway lines in California

- 25 kV AC railway electrification

- 2029 in rail transport

- Megaprojects

- High-speed railway lines under construction

- Transportation buildings and structures in Madera County, California

- Buildings and structures under construction in the United States

- High-speed trains of the United States

- Rail junctions in the United States