Kabul

Kabul

کابل Caubul, Cabul, Cabool | |

|---|---|

City | |

| Country | |

| Province | Kabul |

| No. of districts | 18 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Muhammad Yunus Nawandish |

| Area | |

| • City | 275 km2 (106 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 425 km2 (164 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 1,791 m (5,876 ft) |

| Population (2012) | |

| • Metro | 3,289,000 |

| • Demonym | Kabuli |

| [1] | |

| Time zone | UTC+4:30 (Afghanistan Standard Time) |

Kabul (Kābul) (/[invalid input: 'icon']ˈkɑːbəl/, /ˈkɑːbuːl/; Pashto: کابل Kābəl, IPA: [kɑˈbəl]; Persian: کابل Kābol, IPA: [kɒːˈbol]),[2] also spelled Cabool, Caubul, Kabol, or Cabul, mostly in historical contexts, is the capital and largest city of Afghanistan. It is also the capital of Kabul Province, located in the eastern section of Afghanistan. According to a 2012 estimate, the population of the city is 3,289,000.[1] Kabul is the 64th largest[3] and the 5th fastest growing city in the world.[4]

The city serves as the nation's cultural and learning centre, situated 1,791 metres (5,876 ft) above sea level in a narrow valley, wedged between the Hindu Kush mountains along the Kabul River. It is linked with Kandahar, Herat and Mazar-e Sharif via the circular Highway 1 that stretches across Afghanistan. It is also the start of the main road to Jalalabad and further to Peshawar in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. The Kabul International Airport is located about 16 kilometres (9.9 mi) from the center of the city, next to the Wazir Akbar Khan neighborhood. Bagram Airfield is about 25 miles (40 km) northeast of Kabul.[5]

Kabul's main products include fresh and dried fruit, nuts, beverages, Afghan rugs, leather and sheep skin products, furniture, antique replicas, and domestic clothes. The wars since 1978 have limited the city's economic productivity but after the establishment of the Karzai administration in late 2001 some progress has been made.

Kabul is over 3,500 years old; many empires have long fought over the valley for its strategic location along the trade routes of South and Central Asia. It made up the eastern end of the Median Empire before becoming part of the Achaemenid Empire. In 331 BC, Alexander the Great defeated the Achaemenids and the area became part of the Seleucid Empire followed by the Maurya Empire. By the 1st century AD it became the capital of the Kushan Empire. It was later controlled by the Kabul Shahis, Saffarids, Ghaznavids, Ghurids, and others.[6]

Between 1504 and 1526 AD, it served as the capital of Babur, founder of the Mughal Empire. It remained under the rule of the Mughal Sultans as the western capital until 1738 when Nader Shah and his Afsharid forces conquered the Mughal Empire.[7] After the death of Nader Shah Afsharid in 1747, the city fell to Ahmad Shah Durrani, who added it to his new Afghan Empire.[8] In 1776, Timur Shah Durrani made it the capital of the modern state of Afghanistan. It was invaded several times by neighboring British-Indian forces during the Anglo-Afghan wars in the 19th century. After the outbreak of the Third Anglo-Afghan War in 1919, the city was air raided by the Royal Air Force of British India.[9][10]

Since the Marxist revolution in 1978, the city has been a target of Pakistan-backed militant groups such as the mujahideen, Taliban, Haqqani network, Hezbi Islami, and others. While the Afghan government tries to rebuild the war-torn city, insurgents have continued to stage major attacks not only against the Afghan government and NATO-led forces but also against foreign diplomats and Afghan civilians.[11]

History

Antiquity

The word "Kubhā" is mentioned in Rigveda and the Avesta and appears to refer to the Kabul River.[12] The Rigveda praises it as an ideal city, a vision of paradise set in the mountains.[13] The area in which the Kabul valley sits was ruled by the Medes before falling to the Achaemenids. There is a reference to a settlement called Kabura by the rulers of the Achaemenid Empire,[citation needed] which may be the basis for the future use of the name Kabura (Κάβουρα) by Ptolemy.[12] It became a centre of Zoroastrianism followed by Buddhism and Hinduism.[citation needed] Alexander the Great explored the Kabul valley after his conquest of the Achaemenid Empire in 330 BC but no record has been made of Kabul, which may have been only a small town and not worth writing about.[6] The region became part of the Seleucid Empire but was later gifted to the Indian Maurya Empire.

"Alexander took these away from the Aryans and established settlements of his own, but Seleucus Nicator gave them to Sandrocottus (Chandragupta), upon terms of intermarriage and of receiving in exchange 500 elephants."[6]

— Strabo, 64 BC–24 AD

| History of Afghanistan |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

The Greco-Bactrians captured Kabul from the Mauryans in the early 2nd century BC, then lost the city to their subordinates in the Indo-Greek Kingdom around the mid-2nd century BC. Indo-Scythians expelled the Indo-Greeks by the mid 1st century BC, but lost the city to the Kushan Empire about 100 years later.[14]

Some historians ascribe Kabul the Sanskrit name of Kamboja (Kamboj).[15][16] It is mentioned as Kophes or Kophene in some classical writings. Hsuan Tsang refers to the name as Kaofu[17] in the 7th century AD, which is the appellation of one of the five tribes of the Yuezhi who had migrated from across the Hindu Kush into the Kabul valley around the beginning of the Christian era.[18] It was conquered by Kushan Emperor Kujula Kadphises in about 45 AD and remained Kushan territory until at least the 3rd century AD.[19][20] The Kushans were Indo-European-speaking Tocharians from the Tarim Basin.[21]

Around 230 AD, the Kushans were defeated by the Sassanid Empire and replaced by Sassanid vassals known as the Indo-Sassanids. During the Sassanian period, the city was referred to as "Kapul" in Pahlavi scripts.[12] In 420 AD the Indo-Sassanids were driven out of Afghanistan by the Xionite tribe known as the Kidarites, who were then replaced in the 460s by the Hephthalites. It became part of the surviving Turk Shahi Kingdom of Kapisa, also known as Kabul-Shahan.[22] According to Táríkhu-l Hind by Al-Biruni, Kabul was governed by princes of Turkic lineage whose rule lasted for about 60 generations.

"Kábul was formerly governed by princes of Turk lineage. It is said that they were originally from Tibet. The first of them was named Barhtigín, * * * * and the kingdom continued with his children for sixty generations. * * * * * The last of them was a Katormán, and his minister was Kalar, a Bráhman. This minister was favoured by fortune, and he found in the earth treasures which augmented his power. Fortune at the same time turned her back upon his master. The Katormán's thoughts and actions were evil, so that many complaints reached the minister, who loaded him with chains, and imprisoned him for his correction. In the end the minister yielded to the temptation of becoming sole master, and he had wealth sufficient to remove all obstacles. So he established himself on the throne. After him reigned the Bráhman(s) Samand, then Kamlúa, then Bhím, then Jaipál, then Anandpál, then Narda-janpál, who was killed in A.H. 412. His son, Bhímpál, succeeded him, after the lapse of five years, and under him the sovereignty of Hind became extinct, and no descendant remained to light a fire on the hearth. These princes, notwithstanding the extent of their dominions, were endowed with excellent qualities, faithful to their engagements, and gracious towards their inferiors..."[22]

— Abu Rayhan Biruni, 978-1048 AD

The Kabul rulers built a long defensive wall around the city to protect it from enemy raids. This historical wall has survived until today.

Islamization and Mongol invasion

The Islamic conquest reached modern-day Afghanistan in 642 AD, at a time when Kabul was independent.[23] A number of failed expeditions were made to Islamize the region. In one of them, Abdur Rahman bin Samana arrived to Kabul from Zaranj in the late 7th century and managed to convert 12,000 local inhabitants to Islam before abandoning the city. Muslims were a minority until Ya'qub bin Laith as-Saffar of Zaranj conquered Kabul in 870 and established the first Islamic dynasty in the region. It was reported that the rulers of Kabul were Muslims with non-Muslims living close by.

"Kábul has a castle celebrated for its strength, accessible only by one road. In it there are Musulmáns, and it has a town, in which are infidels from Hind."[24]

— Istahkrí, 921 AD

Over the centuries to come, the city was successively controlled by the Samanids, Ghaznavids, Ghurids, and Khiljis. In the 13th century the Mongol horde passed through and caused massive destruction in the area. Report of a massacre in the close by Bamiyan is recorded around this period, where the entire population of the valley was annihilated by the Mongol troops as a revenge for the death of Genghis Khan's grandson. During the Mongol invasion, many natives of Afghanistan fled to India where some established dynasties in Delhi.

Following the era of the Khilji dynasty in 1333, the famous Moroccan scholar Ibn Battuta was visiting Kabul and wrote:

"We travelled on to Kabul, formerly a vast town, the site of which is now occupied by a village inhabited by a tribe of Persians called Afghans. They hold mountains and defiles and possess considerable strength, and are mostly highwaymen. Their principle mountain is called Kuh Sulayman."[25]

— Ibn Battuta, 1304–1369 AD

Timurid and Mughal era

In the 14th century, Kabul became a major trading centre under the kingdom of Timur (Tamerlane). In 1504, the city fell to Babur from the north and made into his headquarters, which became one of the principal cities of his later Mughal Empire. In 1525, Babur described Kabulistan in his memoirs by writing that:

"In the country of Kābul there are many and various tribes. Its valleys and plains are inhabited by Tūrks, Aimāks, and Arabs. In the city and the greater part of the villages, the population consists of Tājiks (called "Sarts" by Babur). Many other of the villages and districts are occupied by Pashāis, Parāchis, Tājiks, Berekis, and Afghans. In the hill-country to the west, reside the Hazāras and Nukderis. Among the Hazāra and Nukderi tribes, there are some who speak the Moghul language. In the hill-country to the north-east lies Kaferistān, such as Kattor and Gebrek. To the south is Afghanistān... There are eleven or twelve different languages spoken in Kābul: Arabic, Persian, Tūrki, Moghuli, Hindi, Afghani, Pashāi, Parāchi, Geberi, Bereki, and Lamghāni..."[26]

— Baburnama, 1525

Mirza Muhammad Haidar Dughlat, a poet from Hindustan who visited at the time wrote: "Dine and drink in Kabul: it is mountain, desert, city, river and all else." It was from here that Babur began his 1526 conquest of Hindustan, which was ruled by the Afghan Lodi dynasty and began east of the Indus River in what is present-day Pakistan. Babur loved Kabul due to the fact that he lived in it for 20 years and the people were loyal to him, including its weather that he was used to. His wish to be buried in Kabul was finally granted. The inscription on his tomb contains penned Persian words which state: اگرفردوس روی زمین است همین است و همین است و همین است (If there is a paradise on earth, it is this, it is this, it is this!)[27]

Durrani Empire and Western influence

Nader Shah Afshar invaded and occupied the city briefly in 1738 but was assassinated nine years later. Ahmad Shah Durrani, commander of 4,000 Abdali Afghans, asserted Pashtun rule in 1747 and further expanded his new Afghan Empire. His ascension to power marked the beginning of Afghanistan. His son Timur Shah Durrani, after inheriting power, transferred the capital of Afghanistan from Kandahar to Kabul in 1776,[7] and used Peshawar in what is today Pakistan as the winter capital. Timur Shah died in 1793 and was succeeded by his son Zaman Shah Durrani. Kabul's first visitor from Europe was Englishman George Foster, who described 18th-century Kabul as "the best and cleanest city in Asia".[13]

In 1826, the kingdom was claimed by Dost Mohammad Khan but in 1839 Shujah Shah Durrani was re-installed with the help of British India during the First Anglo-Afghan War. An 1841 local uprising resulted in the loss of the British mission and the subsequent death of 16,500 British-led Indian forces, which included soldiers and camp followers while retreating from Kabul to Jalalabad. In 1842 the British returned, plundering Bala Hissar in revenge before fleeing back to British India (now Pakistan). Akbar Khan took to the throne from 1842 to 1845 who was followed by Dost Mohammad Khan.

The British-led Indian forces invaded in 1878 as Kabul was under Sher Ali Khan's rule, but the British residents were again massacred. The British returned in 1879 under General Roberts, partially destroying Bala Hissar before retreating to British India. Amir Abdur Rahman Khan was left in control of the country.

In the early 20th century King Amanullah Khan rose to power. His reforms included electricity for the city and schooling for girls. He drove a Rolls-Royce, and lived in the famous Darul Aman Palace. In 1919, after the Third Anglo-Afghan War, Amanullah announced Afghanistan's independence from foreign affairs at Eidgah Mosque. In 1929 King Ammanullah left Kabul due to a local uprising orchestrated by Habibullah Kalakani. After nine months rule, Kalakani was imprisoned and executed by King Nader Khan. Three years later, in 1933, the new king was assassinated by a Hazara student Abdul Khaliq during an award ceremony inside a school in Kabul. The throne was left to his 19-year-old son, Zahir Shah, who became the long lasting King of Afghanistan.

During this period between the two World Wars, France and Germany worked to help develop the country in both the technical and educational spheres. Both countries maintained high schools and lycees in the capital and provided an education for the children of elite families.[28] Kabul University opened in 1932 and soon was linked to both European and American universities, as well as universities in other Muslim countries in the field of Islamic studies.[29] By the 1960s the majority of instructors at the university had degrees from Western universities.[29]

When Zahir Shah took power in 1933 Kabul had the only 6 miles of rail in the country, few internal telegraph or phone lines and few roads. He turned to the Japanese, Germans and Italians for help developing a modern network of communications and roads.[30] A radio tower built by the Germans in 1937 in Kabul allowed instant communication with outlying villages.[31] A national bank and state cartels were organized to allow for economic modernization.[32] Textile mills, power plants and carpet and furniture factories were also built in Kabul, providing much needed manufacturing and infrastructure.[32]

In 1955, the Soviet Union forwarded $100 million in credit to Afghanistan, which financed public transportation, airports, a cement factory, mechanized bakery, a five-lane highway from Kabul to the Soviet border and dams.[33]

In the 1960s, Kabul developed a cosmopolitan mood. The first Marks & Spencer store in Central Asia was built there. Kabul Zoo was inaugurated in 1967, which was maintained with the help of visiting German zoologists. Many foreigners began flocking to Kabul with the increase in global air travels around that time. The nation's tourism industry was starting to pick up rapidly for the first time. Kabul experimented with liberalization, dropping laws requiring women to wear the burka, restrictions on speech and assembly loosened which led to student politics in the capital.[34] Socialist, Maoist and liberal factions demonstrated daily in Kabul while more traditional Islamic leaders spoke out against the failure to aid the Afghan countryside.[34]

In 1969 a religious uprising at the Pul-e Khishti Mosque protested the Soviet Union's increasing influence over Afghan politics and religion. This protest ended in the arrest of many of its organizers, including Mawlana Faizani, a popular Islamic scholar. In the early 1970s Radio Kabul began to broadcast in other languages besides Pashto which helped to unify those minorities that often felt marginalized. However, this was put to a stop after Daoud Khan's revolution in 1973.[35]

In July 1973, while King Zahir Shah was visiting Europe, his cousin Daoud Khan who served as Prime Minister took over as leader in Kabul. This was supported by the People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA), a pro-Soviet political party. Daoud named himself President and planned to institute reforms.[36] By 1975, the young Ahmad Shah Massoud and his followers initiated an uprising in Panjshir but were forced to flee to neighboring Pakistan where they received recruitment from Pakistani Prime Minister Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto to create unrest in Afghanistan with the help of Pakistan's ISI spy agency.[37] Bhutto paved the way for the April 1978 Saur Revolution in Kabul by making Daoud spread his armed forces to the countryside. "To launch this plan, Bhutto recruited and trained a group of Afghans in the Bala-Hesar of Peshawar, in Pakistan's North-west Frontier Province. Among these young men were Massoud, Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, and other members of Jawanan-e Musulman. Massoud's mission to Bhutto was to create unrest in northern Afghanistan. It served Massoud's interests, which were apparently opposition to the Soviets and independence for Afghanistan. Later, after Massoud and Hekmatyar had a terrible falling-out over Massoud's opposition to terrorist tactics and methods, Massoud overthrew from Jawanan-e Musulman. He joined Rabani's newly created Afghan political party, Jamiat-i-Islami, in exile in Pakistan."[38]

Kabul's people describe the period before the April 1978 Revolution as sort of a golden age. All the different ethnic groups of Afghanistan lived together harmoniously and thought of themselves first and foremost as Afghans. They intermarried and mixed socially.[13] In the later years of his leadership, Daoud began to shift favour from the Soviet Union to Islamic nations, expressing admiration for their wealth from oil and expecting economic aid from them to quickly surpass that of the Soviet Union.[39] The slow speed of reforms however frustrated both the Western educated elite and the Russian-trained army officers.[40]

Soviet invasion and rise of mujahideen

On April 28, 1978, President Daoud and his family along with many of his supporters were assassinated in Kabul. Pro-Soviet PDPA under Hafizullah Amin seized power and slowly began to institute reforms.[40] Private businesses were nationalized in the Soviet manner.[41] Education was modified into the Soviet model, with lessons focusing on teaching Russian, Leninism-Marxism and learning of other countries belonging to the Soviet bloc.[41] Foreign-backed rebel groups and army deserters took up arms in the name of Islam.[41]

In February 1979, U.S. Ambassador Adolph Dubs was murdered after Afghan security forces burst in on his kidnappers. In neighboring Pakistan, President Zulfiqar Bhutto was executed in April 1979. In September 1979 Afghan President Nur Muhammad Taraki was assassinated by a team of Soviet Spetsnaz inside the Tajbeg Palace in Kabul.[42] On December 24, 1979, the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan and Kabul was heavily occupied by Soviet Armed Forces. Following this invasion, Pakistani President Zia-ul-Haq chaired a meeting in Islamabad and was told by several cabinet members to refrain from interfering in Afghanistan.[43] Zia-ul-Haq, fearing that the Soviets may be advancing into Pakistan, particularly Balochistan, made no secret about his intentions of aiding the mujahideen rebel groups. During this meeting, Director-General of the ISI Akhtar Abdur Rahman advocated for the idea of covert operation in Afghanistan by arming the Islamic extremists.[43] General Rahman was heard loudly saying: "Kabul must burn! Kabul must burn!",[44] and mastered the idea of proxy war in Afghanistan.[43] President Zia-ul-Haq authorised this operation under General Rahman, and it was later merged with Operation Cyclone, a programme funded by the United States.

The Soviets turned the city of Kabul into their command centre during the 10-year conflict between pro-Soviet Afghan government and the Mujahideen rebels, who were funded by the United States and Saudi Arabia. Kabul remained relatively calm during that period as fighting was mostly in the countryside and in other major cities. In April 1988, the Geneva Accords were signed between Afghanistan and Pakistan, with the United States and the Soviet Union serving as guarantors. In August 1988, President Zia-ul-Haq, General Rahman and other top Pakistani officials, including U.S. Ambassador Arnold Lewis Raphel, were killed in a mysterious plane crash in neighboring Pakistan. The American Embassy in Kabul closed in January 1989.

Civil war and Taliban regime

"The Mujahideen continued to fight against the government of Najibullah, the Soviet puppet president who had replaced Babrak Karmal in 1986. Najibullah had proposed cease fires during those years, but the rebels said they would not negotiate with puppets - and they gained ground strategically until the Soviets admitted defeat and left."[38] After the fall of Najibullah's Democratic Republic of Afghanistan in April 1992, leaders of the different mujahideen factions were unable to form a government so they resorted to fighting.

Pakistan supplied Hezbi Islami forces of Hekmatyar, Iran supported the Shi'a Hezbe Wahdat forces of Abdul Ali Mazari, and Saudi Arabia backed Abdul Rasul Sayyaf. "Pakistan's Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif held hotly contested meetings with the ISI chief, his other ministers, and the Mujahideen in Peshawar and the Hezbi Islami faction, headed by Hekmatyar, who was deeply loyal to the Pakistani military dictatorship. Hekmatyar's troops started firing mortats into Kabul. Najibullah took refuge in the UN compound after being stopped by General Dostum's forces from boarding a United Nations airplane at the Kabul airport. On April 24, the Afghan army and the Mujahideen took Kabul peacefully, and throughout the city the various factions staked out zones of control."[45]

The 1992 Peshawar Accords created the Islamic State of Afghanistan and appointed Burhanuddin Rabbani, an ethnic Tajik, as head of a transitional government to be followed by general elections.[46] Another ethnic Tajik, Ahmad Shah Massoud, became Defense Minister and the Pashtun Gulbuddin Hekmatyar as Prime Minister. After the interim period expired, Rabbani, founder and leader of Jamiat-e Islami, which is connected to Pakistan's Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam, refused to step down and a full scale civil war began. Amin Saikal explains that under Benazir Bhutto and Nawaz Sharif "Pakistan was keen to gear up for a breakthrough in Central Asia. ... Islamabad could not possibly expect the new Islamic government leaders ... to subordinate their own nationalist objectives in order to help Pakistan realize its regional ambitions. ... Had it not been for the ISI's logistic support and supply of a large number of rockets, Hekmatyar's forces would not have been able to target and destroy half of Kabul."[47]

In December 1992, the last of the 86 city trolley buses in Kabul came to a halt because of the conflict. A system of 800 public buses continued to provide transportation services to the city. By 1993 electricity and water in the city was completely out. Initially the factions in the city aligned to fight off Hekmatyar but diplomacy inside the capital quickly broke down.[48] Saudi Arabia and Iran also guided Afghan factions.[47]

Additionally to the bombardment campaign conducted by Hekmatyar and Dostum, tension between the Shi'a Hazara forces of Abdul Ali Mazari and the Wahabi Ittihad-i Islami of Abdul Rasul Sayyaf soon escalated into a second violent conflict. The fighting between the two factions quickly took on aspects of "ethnic cleansing".[49] According to Human Rights Watch, numerous Iranian agents were assisting Hezbe Wahdat, as "Iran was attempting to maximize Wahdat's military power and influence in the new government".[46][47][50] Saudi agents "were trying to strengthen the Wahhabi Abdul Rasul Sayyaf and his Ittihad-i Islami faction to the same end".[46][47] A publication with the George Washington University describes "Outside forces saw instability in Afghanistan as an opportunity to press their own security and political agendas."[51] Human Rights Watch writes that "Rare ceasefires, usually negotiated by representatives of Ahmad Shah Massoud, Sibghatullah Mojaddedi or Burhanuddin Rabbani (the interim government), or officials from the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), commonly collapsed within days."[46]

In January 1994, Dostum joined an alliance with Hekmatyar and conducted the worst bombardment of Kabul during that period, but were eventually repelled by forces of Ahmad Shah Massoud.[47] In late 1994, bombardment of the capital came to a temporary halt.[52][53][54] These forces took steps to restore law and order. Courts started to work again, convicting individuals inside government troops who had committed crimes.[55] Massoud tried to initiate a nationwide political process with the goal of national consolidation and democratic elections, also inviting the Pashtun nationalist Taliban from southern Afghanistan to join the process but the idea was rejected by them.[56]

The Taliban started shelling Kabul in early 1995 but were repelled at first by forces of Ahmad Shah Massoud.[53] (see video) Amnesty International, referring to the Taliban offensive, wrote in a 1995 report that "This is the first time in several months that Kabul civilians have become the targets of rocket attacks and shelling aimed at residential areas in the city."[53] The Taliban's early victories in 1994 were followed by a series of defeats that resulted in heavy losses.[57] Pakistan provided strong support to the Taliban.[47][58] Many described the Taliban as developing into a proxy force for Pakistan's regional interests.[47]

On September 26, 1996, as the Taliban with military support by Pakistan and financial support by Saudi Arabia prepared for another major offensive, Massoud ordered a full retreat from Kabul and fled north.[59] The Taliban seized Kabul on September 27, 1996, and established the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan. The Taliban publicly lynched former president Najibullah and his brother to death, this made many Afghans angry. The Taliban also imposed on Afghans their political and judicial interpretation of Islam issuing edicts especially targeting women.[60] The Physicians for Human Rights (PHR) analyze:

"To PHR’s knowledge, no other regime in the world has methodically and violently forced half of its population into virtual house arrest, prohibiting them on pain of physical punishment."[60]

The Taliban, without any real court or hearing, conducted amputations against common thieves. Taliban hit-squads from the infamous "Ministry for Promotion of Virtue and Prevention of Vice" watched the streets conducting arbitrary brutal and public beatings of people.[60]

Massoud and his former enemy Dostum later formed the Northern Alliance against the Pakistani-backed Taliban who were violating human rights on a mass scale. The National Geographic concluded that "The only thing standing in the way of future Taliban massacres is Ahmad Shah Massoud."[61] Many at first welcomed the Taliban but later began to realize that they were another Pakistani-created force determined to turn Afghans into slaves and ultimately end Afghanistan.

Pakistani President Pervez Musharraf – then as Chief of Army Staff – was responsible for sending large number of Pakistanis to fight alongside the Taliban.[56][58][61][62] According to regional expert Ahmed Rashid, "between 1994 and 1999, an estimated 80,000 to 100,000 Pakistanis trained and fought in Afghanistan" on the side of the Taliban.[63] During that period many Afghan women were being kidnapped and then sold to Arab or Pakistani men.[64] The al-Qaeda of Osama Bin Laden and Ayman al-Zawahiri became a state within the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, with Bin Laden controlling Kabul and the eastern city of Jalalabad.[65] In the meantime, Taliban supreme leader Mohammed Omar stayed in Kandahar and has never been to Kabul.

NATO presence and the Karzai administration

In October 2001, US-led forces provided air support to the Northern Alliance (United Front) forces during Operation Enduring Freedom. The Taliban began abandoning Kabul while the United Front was heading to take control of the government. In December 2001, the Karzai administration under President Hamid Karzai officially took over the government.

In early 2002, a NATO-led International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) was deployed in the city and from there they spread to other parts of the country. The war-torn city began to see some positive development as millions of ex-pats returned to the country. The city's population has grown from about 500,000 in 2001 to 3 million by 2007. Many foreign embassies re-opened, including the U.S. Embassy. Afghan government institutions were also renovated. Since 2008 the Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF) are in charge of security in the city.

While the city is being developed, it is the scene of occasional deadly suicide bombings and explosions carried out by the Haqqani network, Taliban's Quetta Shura, Hezbi Islami, al-Qaeda, and other anti-government elements who are claimed to be supported and guided by Pakistan.[66][67][68][69] For example, in September 2011, heavily armed Taliban insurgents wearing suicide vests struck the U.S. Embassy and NATO headquarters.[70][71] In the December 2011 Ashura bombing over 70 civilians were killed and over 160 injured.[11][72][73] Many other similar attacks took place after the 2008 ISAF hand-over of security to Afghan security forces. Some of the targets were the Kabul International Airport, Serena Hotel, Kabul City Center, Inter-Continental Hotel, UN guest house, the Presidential Palace, Ministry of the Interior, Ministry of Justice, Indian Embassy, Afghan National Police stations, supermarkets, residence of Burhanuddin Rabbani, guest house of Asadullah Khalid, and other top Afghan officials.

According to Transparency International, the government of Afghanistan is the third most-corrupt in the world.[74] Many decision makers in Kabul are not only poorly educated but negatively influenced by neighboring Iran and Pakistan.[75][76][77][78][79][80][81] Experts believe that the poor decisions of Afghan politicians contribute to the unrest in the region. This also prevents foreign investment in Afghanistan, especially by Western countries. When five American soldiers burned several copies of Quran at nearby Bagram Airfield in 2012, politicians in Kabul showed their personal anger in the media. Ordinary Afghans may have taken cues from their leaders and taken more offense at the incident than they otherwise might have. As the Afghan government rushes into taking over security responsibility from NATO the security situation in the country is deteriorating. In 2012, it forced the United States to hand over control of the Parwan Detention Facility where thousands of militants are held. The United States had favored a gradual transition of the facility until 2014.

Climate

Kabul has a semi-arid climate (Köppen climate classification BSk) with precipitation concentrated in the winter (almost exclusively falling as snow) and spring months. Temperatures are relatively cool compared to much of Southwest Asia, mainly due to the high elevation of the city. Summer has very low humidity, providing relief from the heat. Autumn features warm afternoons and sharply cooler evenings. Winters are cold, with a January daily average of −2.3 °C (27.9 °F). Spring is the wettest time of the year, though temperatures are generally amiable. Sunny conditions dominate year-round. The annual mean temperature is 12.1 °C (53.8 °F).

| Climate data for Kabul (1956–1983) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 18.8 (65.8) |

18.4 (65.1) |

26.7 (80.1) |

28.7 (83.7) |

33.5 (92.3) |

36.8 (98.2) |

37.7 (99.9) |

37.3 (99.1) |

35.1 (95.2) |

31.6 (88.9) |

24.4 (75.9) |

20.4 (68.7) |

37.7 (99.9) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 4.5 (40.1) |

5.5 (41.9) |

12.5 (54.5) |

19.2 (66.6) |

24.4 (75.9) |

30.2 (86.4) |

32.1 (89.8) |

32.0 (89.6) |

28.5 (83.3) |

22.4 (72.3) |

15.0 (59.0) |

8.3 (46.9) |

19.6 (67.3) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −2.3 (27.9) |

−0.7 (30.7) |

6.3 (43.3) |

12.8 (55.0) |

17.3 (63.1) |

22.8 (73.0) |

25.0 (77.0) |

24.1 (75.4) |

19.7 (67.5) |

13.1 (55.6) |

5.9 (42.6) |

0.6 (33.1) |

12.1 (53.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −7.1 (19.2) |

−5.7 (21.7) |

0.7 (33.3) |

6.0 (42.8) |

8.8 (47.8) |

12.4 (54.3) |

15.3 (59.5) |

14.3 (57.7) |

9.4 (48.9) |

3.9 (39.0) |

−1.2 (29.8) |

−4.7 (23.5) |

4.3 (39.7) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −25.5 (−13.9) |

−24.8 (−12.6) |

−12.6 (9.3) |

−2.1 (28.2) |

0.4 (32.7) |

3.1 (37.6) |

7.5 (45.5) |

6.0 (42.8) |

1.0 (33.8) |

−3.0 (26.6) |

−9.4 (15.1) |

−18.9 (−2.0) |

−25.5 (−13.9) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 34.3 (1.35) |

60.1 (2.37) |

67.9 (2.67) |

71.9 (2.83) |

23.4 (0.92) |

1.0 (0.04) |

6.2 (0.24) |

1.6 (0.06) |

1.7 (0.07) |

3.7 (0.15) |

18.6 (0.73) |

21.6 (0.85) |

312.0 (12.28) |

| Average rainy days | 2 | 3 | 10 | 11 | 8 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 48 |

| Average snowy days | 7 | 6 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 20 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 68 | 70 | 65 | 61 | 48 | 36 | 37 | 38 | 39 | 42 | 52 | 63 | 52 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 177.2 | 178.6 | 204.5 | 232.5 | 310.3 | 353.4 | 356.8 | 339.7 | 303.9 | 282.6 | 253.2 | 182.4 | 3,175.1 |

| Source: NOAA[82] | |||||||||||||

Administration

The Mayor of the city is selected by the President of Afghanistan, who engages in planning and environmental work. The police belong to the Afghan Ministry of Interior and are arranged by city districts. The Chief of Police is selected by the Minister of Interior and is responsible for law enforcement and security of the city. Muhammad Yunus Nawandish was appointed as Mayor of Kabul by the President of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan in January, 2010, and governs a City of an estimated five million in population. Since taking office, the Mayor has initiated an aggressive program of municipal improvements in streets, parks, greenery, revenue collection, environmental control, and solid waste management.

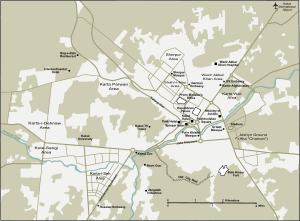

Neighborhoods

The city of Kabul is one of the 15 districts of Kabul Province, which is further divided into 18 city districts or sectors. Each city district covers several neighbourhoods. The number of districts or sectors in Kabul increased from 11 to 18 in 2005.

Below are some of Kabul's neighbourhoods listed:

This list is incomplete and may be incorrect. You can help by expanding it.

This list might also have issues with phonetically reading from Persian to English. Please discuss this matter on the discussion page and improve

North

Northeast

East

- Ahmad Shah Baba Maina (under development)

- Char Qala

- Karte Naw

- Tape Maranjan

- Rahman Baba Maina (under development)

Southeast

South

Southwest

West

North-west

Unspecified If you know where it is located (north, south etc.) please fix this

- Kharabat, Kabul

- Mirwais Nika Maina (under development)

- Murad Khane

- Tania, Kabul

Demographics

The population of Kabul has fluctuated since the early 1980s to the present period. It was believed to be around 500,000 in 2001 but then many Afghan expats began returning from Pakistan and Iran where they had taken refuge from the decades of wars.[83] According to a 2012 official estimate, the total population of the city was 3,289,000.[1] The World Factbook estimated in 2009 that Kabul's population was little over 3.5 million[84]

The population of the city reflects the general multi-ethnic, multi-cultural, and multi-lingual characteristics of Afghanistan. There is no official government report on the exact ethnic make-over. According to a 2003 report in the National Geographic, the population of the city consisted of 45% Tajiks, 25% Hazaras, 25% Pashtuns, 2% Uzbeks, 1% Baloch, 1% Turkmen, and 1% Hindu.[85] Dari (Afghan Persian) and Pashto are the most widely used languages in the city,[86] although Afghan Persian serves as the lingua franca.

Nearly all the people of Kabul are Muslim, which includes the majority Sunnis and minority Shias. A small number of Sikhs, Hindus, and Christians are also found in the city.

Transport

Kabul International Airport, located 25 kilometres (16 mi) from the centre of Kabul, is the country's main airport. It is a hub to Ariana Afghan Airlines, the national airlines carrier of Afghanistan, as well as private airlines such as Kam Air, Pamir Airways, and Safi Airways. Regional airlines such as Turkish Airlines, Gulf Air, Indian Airlines, Pakistan International Airlines (PIA), Iranian Airlines, and others also make frequent stops at Kabul International Airport. A new international terminal was built by the government of Japan and began operation since 2008, which is the first of three terminals to be opened so far. The other two will open once air traffic to the city increases. Passengers coming from most foreign nations use mostly Dubai for flights to Kabul. Kabul Airport also has a military terminal and a section of airport is used by the United States armed forces and the Afghan National Air Force. NATO also uses the Kabul Airport, but most military traffic is based at Bagram Airfield, situated north of Kabul. The Afghan Border Police and the Afghan National Police are in charge of the airport security.

Kabul has no train service yet but the government plans to build rail lines to connect the city with Mazar-i-Sharif in the north and Jalalabad-Torkham in the east. It also plans to build a metro rail in the future.

Long distance road journeys are made by private Mercedes-Benz coach buses or various types of vans, trucks and cars. Although a nation wide bus service is available from Kabul, flying is safer, especially for foreigners. The city's public bus service (Milli Bus / "National Bus") was established in the 1960s to take commuters on daily routes to many destinations. The service currently has about 800 buses, but it is gradually expanding and upgrading the fleet. The Kabul bus system has recently discovered a new source of revenue in whole-bus advertising from MTN similar to "bus wrap" advertising on public transit in more developed nations. There is also an express bus that runs from the city centre to Kabul International Airport for Safi Airways passengers. There are also white and yellow older model Toyota Corolla taxicabs just about every where in the city.

Private vehicles are on the rise in Kabul, with Toyota, Nissan, and other dealerships in the city. People are buying new cars as the roads and highways are being improved. Most drivers in Kabul prefer owning a Toyota Corolla, one of Afghanistan's most popular cars. It has been reported that up to 90% of cars in Kabul are Corollas.[87][88] With the exception of motorcycles, many vehicles in the city operate on LPG. Gas stations are mainly private-owned and the fuel comes from Pakistan, Iran and Kazakhstan. Bicycles on the road are a common sight in the city.

Economy

There are approximately 16 licensed banks in Kabul: including Da Afghanistan Bank, Afghanistan International Bank, Kabul Bank, Azizi Bank, Pashtany Bank, Afghan United Bank, Standard Chartered Bank, Punjab National Bank, Habib Bank and others. Western Union offices are also found in many locations throughout the city.

About 4 miles (6 km) from downtown Kabul, in Bagrami, a 22-acre (9 ha) wide industrial complex has completed with modern facilities, which will allow companies to operate businesses there. The park has professional management for the daily maintenance of public roads, internal streets, common areas, parking areas, 24 hours perimeter security, access control for vehicles and persons.[89] A number of factories operate there, including the $25 million Coca-Cola bottling plant and the Omaid Bahar juice factory.

A number of indoor shopping centers have opened in the last decade. This includes the Kabul City Center, which also serves as a 4-star holel (Safi Landmark Hotel). The Aga Khan Development Network (AKDN) opened a 5-star Serena Hotel in the same year, while the landmark Inter-Continental has been refurbished. The AKDN was also involved in the restoration work of the Bagh-e Babur (Babur Gardens). Another 5-star Marriott Hotel is under construction next to the U.S. Embassy.

Communications

GSM/GPRS mobile phone services in the city are provided by Afghan Wireless, Etisalat, Roshan and MTN. In November 2006, the Afghan Ministry of Communications signed a $64.5 million US dollar deal with ZTE on the establishment of a countrywide fibre optical cable network to help improve telephone, internet, television and radio broadcast services not just in Kabul but throughout the country.[90] Internet cafes were introduced in 2002 and has been expanding throughout the country. As of 2012, 3G services are also available.

The city has many local-language radio and television stations, including in Pashto and Dari (Persian). The Afghan government has become increasingly intolerant of foreign channels and the un-Islamic culture they bring, and has threatened to ban some.

There are a number of post offices throughout the city. Package delivery services like FedEx, TNT N.V., and DHL are also available.

Education

Public and private schools in the city have reopened since 2002 after they were shut down or destroyed during fighting in the 1980s to the late 1990s. Boys and girls are strongly encouraged to attend school under the Karzai administration but many more schools are needed not only in Kabul but throughout the country. The Afghan Ministry of Education has plans to build more schools in the coming years so that education is provided to all citizens of the country. The most well known high schools in Kabul include:

- Habibia High School, a British-Afghan school founded in 1903 by King Habibullah Khan.

- Lycée Esteqlal, a Franco-Afghan school founded in 1922.

- Amani High School, a German-Afghan school for boys founded in 1924.

- Aisha-i-Durani School, a German-Afghan school for girls.

- Rahman Baba High School, an American-Afghan school for boys.

The city's colleges and universities were renovated after 2002. Some of them have been developed recently, while others have existed since the early 1900s.

Universities in Kabul

- American University of Afghanistan

- Kabul University

- Kabul Medical University

- Polytechnical University of Kabul (Kabul Polytechnic)

- Higher Education Institute of Karwan

- Kaboora Institute of Higher Education

- Rana Institute of Higher Education

- Bakhtar Institute of Higher Education

- Kardan University

- Dawat University

- National Military Academy of Afghanistan

Places of interest

The old part of Kabul is filled with bazaars nestled along its narrow, crooked streets. Cultural sites include: the National Museum of Afghanistan, notably displaying an impressive statue of Surya excavated at Khair Khana, the ruined Darul Aman Palace, the tomb of Mughal Emperor Babur at Bagh-e Babur, and Chehlstoon Park, the Minar-i-Istiqlal (Column of Independence) built in 1919 after the Third Afghan War, the mausoleum of Timur Shah Durrani, and the imposing Id Gah Mosque (founded 1893). Bala Hissar is a fort destroyed by the British in 1879, in retaliation for the death of their envoy, now restored as a military college. The Minaret of Chakari, destroyed in 1998, had Buddhist swastika and both Mahayana and Theravada qualities.

Other places of interest include Kabul City Center, which is Kabul's first shopping mall, the shops around Flower Street and Chicken Street, Wazir Akbar Khan district, Kabul Golf Club, Kabul Zoo, Abdul Rahman Mosque, Shah-Do Shamshira and other famous mosques, the National Gallery of Afghanistan, the National Archives of Afghanistan, Afghan Royal Family Mausoleum, the OMAR Mine Museum, Bibi Mahro Hill, Kabul Cemetery, and Paghman Gardens.

Tappe-i-Maranjan is a nearby hill where Buddhist statues and Graeco-Bactrian coins from the 2nd century BC have been found. Outside the city proper is a citadel and the royal palace. Paghman and Jalalabad are interesting valleys north and east of the city.

- Airports

- Kabul International Airport

- Bagram Airfield (located about 26 miles north from the city center)

- Sports complexes

- Kabul National Cricket Stadium (under construction)

- Ghazi Stadium

- Olympic Committee Gymnasium

- Parks

- Bagh-e Babur (Gardens of Babur)

- Baghi Bala Park

- Zarnegar Park

- Shar-e Naw Park

- Bagh-e Zanana

- Chaman-e-Hozori

- Bibi Mahro Park

- Lake Qargha

- Mosques

- Mausoleums

- Mausoleum of Timur Shah Durrani

- Mausoleum of Abdur Rahman Khan

- Mausoleum of Zahir Shah and Nadir Shah

- Mausoleum of Jamal-al-Din al-Afghani

- Museums

- National Museum of Afghanistan

- National Archives of Afghanistan

- National Gallery of Afghanistan

- Negaristani Milli

- Hotels

- Marriott (slated to be running by 2013)

- Serena Hotel (5 star)

- Inter-Continental

- Safi Landmark Hotel[91]

- Golden Star Hotel[92]

- Heetal Plaza Hotel[93]

- Hospitals

- French Medical Institute for Children

- Indira Gandhi Childrens Hospital

- Jamhuriat Hospital

- Sardar Mohammad Daud Khan Hospital [94]

- Jinnah Hospital (under construction)

- Wazir Akbar Khan Hospital

- Malalai Maternity Hospital

- Maywand Hospital

- Afshar Hospital

Development projects

In late 2007 the government announced that all the residential houses situated on mountains would be removed within a year so that trees and other plants can be grown on the hills. The plan calls for a greener city and to provide residents with a more suitable place to live, on a flat surface. Once implemented it will provide water supply and electricity to each house. All the city roads will also be paved under the plan, which is to solve transportation problems.[95]

The Afghan capital Kabul, symbolizing the spirits of all Afghans and international cooperation, sets at the heart of this highly resourceful region, with great potential to turn into a business hub for all. After 2002, the new geo-political dynamics and its subsequent business opportunities, rapid urban population growth and emergence of high unemployment, triggered the planning of urban extension towards the immediate north of Kabul, in the form of a new city.

In 2006, Engineer Mohammad Yousef Pashtun the then Minister of Urban Development got the approval from President Hamid Karzai to establish an Independent Board for the Development of Kabul New City. The Board brings together key stakeholders, including relevant government agencies, as well as representation from private sector and urban specialists and economists, with cooperation from the government of Japan and French Private sector, the board prepared a master plan for the city in the context of Greater Kabul. The master plan and its implementation strategy for 2025 were endorsed by the Afghan Cabinet in early 2009. Soon, as a top priority, the initiative turned into one of the biggest commercially viable national development project of the country, expected to be led by the private sector.[96] A number of high rise buildings are being planned and constructed across Kabul, as part of the attempt to modernize the city.[97]

An initial concept design called the City of Light Development, envisioned by Dr. Hisham N. Ashkouri, for the development and the implementation of a privately based investment enterprise has been proposed for multi-function commercial, historic and cultural development within the limits of the Old City of Kabul, along the southern side of the Kabul River and along Jade Meywand Avenue,[98] revitalizing some of the most commercial and historic districts in the City. Also incorporated in the design is a new complex for the National Museum of Afghanistan. A Memorandum of understanding has been signed between Dr. Ashkouri and Said Tayeb Jawad to undertake the project and to develop it for actual implementation over the next 20 years. Dr. Ashkouri has also presented the plan to President Karzai and has received a letter of support from the president and the Minister of Urban Development.

The Mayor of Kabul Muhammad Yunus Nawandish has brought many municipal reform efforts by the U.S. Agency for International Development’s “Kabul City Initiative” project, the World Bank, Japanese Government JICA and other International Donors to build municipal capacity, improve service delivery and infrastructure, and increase municipal revenue for a cleaner and greener Kabul. The city's major Projects include a Kabul cable car, connecting the city to Shirdarwaza mountain, a tunnel though mountains close to Kabul university to reduce traffic jams, building more flyovers in the city with the city's first fly-over being built with the help of Turkey; in addition to providing more trucks and lorries for the municipality.

NGOs

Numerous non-governmental organizations (NGOs), both national and international, are based in Kabul, conducting various activities to assist development in Afghanistan and provide humanitarian relief to the many victims which 30 years of war have produced.

Afghanistan Information Management Services (AIMS) provides software development, capacity development, information management, and project management services to the Afghan Government and other NGOs, thereby supporting their on-the-ground activities.

The We Are the Future (WAF) Center is a child care centre whose aim is to give children a chance to live their childhoods and develop a sense of hope. The centre is managed under the direction of the mayor's office and the international NGO. Glocal Forum serves as the fundraiser, program planner and coordinator for the WAF centre. Launched in 2004, the program is the result of a strategic partnership between the Glocal Forum, the Quincy Jones Listen Up Foundation and Mr. Hani Masri, with the support of the World Bank, UN agencies and major companies.

Sister cities

See also

- List of cities in Afghanistan

- City of Light Development

- Radio Kabul

- Kabul Express

- 2002 Hindu Kush earthquakes

References and footnotes

- ^ a b c Afghanistan Statistical Yearbook 2012/13 (PDF), Central Statistics Office Afghanistan

- ^ See National Review, November 20, 2002, Merriam-Webster: Kabul

- ^ "Largest cities in the world and their mayors - 1 to 150". City Mayors. 2012-05-17. Retrieved 2012-08-17.

- ^ "World's fastest growing urban areas (1)". City Mayors. 2012-05-17. Retrieved 2012-08-17.

- ^ Rocket Attack on U.S. Base in Afghanistan Kills 2 Troops, Wounds 6 Americans

- ^ a b c Nancy Hatch Dupree / Aḥmad ʻAlī Kuhzād (1972). "An Historical Guide to Kabul – The Story of Kabul". American International School of Kabul. Retrieved 2010-09-18.

- ^ a b "Kabul". Online Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2010-09-18.

- ^ Louis Dupree, Nancy Hatch Dupree; et al. "Last Afghan empire". Online Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2010-09-18.

{{cite web}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ "The Road to Kabul: British armies in Afghanistan, 1839-1919". National Army Museum. Retrieved 2012-02-14.

- ^ "Afghanistan 1919-1928: Sources in the India Office Records". British Library. Retrieved 2012-02-14.

1919 (May), outbreak of Third Anglo-Afghan War. British bomb Kabul and Jalalabad;

- ^ a b Baktash, Hashmat; Rodriguez, Alex (December 7, 2008). "Two Afghanistan bombings aimed at Shiites kill at least 59 people". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved December 9, 2011.

- ^ a b c Nancy Hatch Dupree / Aḥmad ʻAlī Kuhzād (1972). "An Historical Guide to Kabul – The Name". American International School of Kabul. Retrieved 2010-09-18.

- ^ a b c "Kabul: City of lost glories". BBC News. November 12, 2001. Retrieved 2010-09-18.

- ^ Houtsma, Martijn Theodoor (1987). E.J. Brill's first encyclopaedia of Islam, 1913-1936. Vol. 2. BRILL. p. 159. ISBN 90-04-08265-4, 9789004082656. Retrieved 2010-08-23.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Levi, P. (1993). Pre-Aryan and pre-Dravidian in India. Asian Educational Services. p. 184. ISBN 81-206-0772-4, 9788120607729. Retrieved 2010-09-18.

...they apply to a population of the north-western frontier of India designated by the nickname of "shaved heads," and specially to the Kamboja of the country of Kabul.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Watson, John Forbes (2007). The people of India: a series of photographic illustrations, with descriptive letterpress, of the races and tribes of Hindustan. Vol. 1. Pagoda Tree Press. p. 276. ISBN 1-904289-44-4, 9781904289449. Retrieved 2010-09-18.

The Sanskrit name of Cabul is Kamboj, and a slight transition of sound renders this name so similar to Kumboh.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Mookerji, Radhakumud (1966). Chandragupta Maurya and his times (4 ed.). Motilal Banarsidass Publ. p. 263. ISBN 81-208-0405-8, 9788120804050. Retrieved 2010-09-18.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "A.—The Hindu Kings of Kábul (p.2)". Sir H. M. Elliot. London: Packard Humanities Institute. 1867–1877. Retrieved 2010-09-18.

- ^ Hill, John E. 2004. The Peoples of the West from the Weilue 魏略 by Yu Huan 魚豢: A Third Century Chinese Account Composed between 239 and 265 AD. Draft annotated English translation... Link

- ^ Hill (2004), pp. 29, 352-352.

- ^ A. D. H. Bivar, KUSHAN DYNASTY, in Encyclopaedia Iranica, 2010

- ^ a b "A.—The Hindu Kings of Kábul". Sir H. M. Elliot. London: Packard Humanities Institute. 1867–1877. Retrieved 2010-09-18.

- ^ Wilson, Horace Hayman (1998). Ariana antiqua: a descriptive account of the antiquities and coins of. Asian Educational Services. p. 452. ISBN 81-206-1189-6, 9788120611894. Retrieved 2010-09-18.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "A.—The Hindu Kings of Kábul (p.3)". Sir H. M. Elliot. London: Packard Humanities Institute. 1867–1877. Retrieved 2010-09-18.

- ^ Ibn Battuta (2004). Travels in Asia and Africa, 1325-1354 (reprint, illustrated ed.). Routledge. p. 416. ISBN 0-415-34473-5, 9780415344739. Retrieved 2010-09-10.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Zahir ud-Din Mohammad Babur (1525). "Events Of The Year 910". Memoirs of Babur. Packard Humanities Institute. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ^ Agrawal, Ashvini (1983-12-01). Studies in Mughal History. Motilal Banarsidass Publisher. ISBN 81-208-2326-5.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Anthony Hyman, "Nationalism in Afghanistan" in International Journal of Middle East Studies, 34:2 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002) 305.

- ^ a b Hyman, 305.

- ^ Nick Cullather, "Damming Afghanistan: Modernization in a Buffer State" in The Journal of American History 89:2 (Indiana: Organization of American Historians, 2002) 518.

- ^ Cullather, 518.

- ^ a b Cullather, 519.

- ^ Cullather, 530.

- ^ a b Cullather, 534.

- ^ Hyman, "Nationalism in Afghanistan", 307.

- ^ John E. Haynes, "Keeping Cool About Kabul" in World Affairs, 145:4 (Washington, D.C.: Heldref Publications, 1983), 371.

- ^ "Ahmad Shah Masoud". Encyclopædia Britannica,. Retrieved 2013-01-08.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ a b Bowersox, Gary W. (2004). The Gem Hunter: The Adventures of an American in Afghanistan. GeoVision, Inc.,. p. 100. ISBN 0-9747-3231-1. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); More than one of|pages=and|page=specified (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Haynes, "Keeping Cool About Kabul", 371.

- ^ a b Haynes, 372.

- ^ a b c Haynes, 373.

- ^ "Nur Muhammad Taraki". Notable Names Database.

- ^ a b c Yousaf, PA, Brigadier General (retired) Mohammad (1991). Silent soldier: the man behind the Afghan jehad General Akhtar Abdur Rahman. Karachi, Sindh: Jang Publishers, 1991. pp. 106 pages.

- ^ Kakar, Hassan M. (1997). Afghanistan: The Soviet Invasion and the Afghan Response, 1979-1982. University of California Press. p. 291. ISBN 0-5202-0893-5. Retrieved 2013-01-08.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); More than one of|pages=and|page=specified (help) - ^ Bowersox (p.192)

- ^ a b c d "Blood-Stained Hands, Past Atrocities in Kabul and Afghanistan's Legacy of Impunity". Human Rights Watch.

During most of the period discussed in this report, the sovereignty of Afghanistan was vested formally in "The Islamic State of Afghanistan," an entity created in April 1992, after the fall of the Soviet-backed Najibullah government... With the exception of Hekmatyar's Hezb-e Islami, all of the parties listed above were ostensibly unified under this government in April 1992 (but as described below, Wahdat later changed sides, in late 1992, and allied with Hezb-e Islami)... Hekmatyar's Hezb-e Islami, for its part, refused to recognize the government for most of the period discussed in this report and launched attacks against government forces and Kabul generally. (Mazari's Wahdat forces joined in these efforts in late 1992.)

- ^ a b c d e f g Amin Saikal. Modern Afghanistan: A History of Struggle and Survival (2006 1st ed.). I.B. Tauris & Co Ltd., London New York. p. 352. ISBN 1-85043-437-9.

- ^ Nazif M Shahrani, "War, Factionalism and the State in Afghanistan" in American Anthropologist 104:3 (Arlington, Virginia: American Anthropological Association, 2008), 719.

- ^ Sidky, "War, Changing Patterns of Warfare, State Collapse, and Transnational Violence in Afghanistan: 1978–2001", 870.

- ^ GUTMAN, Roy (2008): How We Missed the Story: Osama Bin Laden, the Taliban and the Hijacking of Afghanistan, Endowment of the United States Institute of Peace, 1st ed., Washington D.C.

- ^ "The September 11 Sourcebooks Volume VII: The Taliban File". George Washington University. 2003.

- ^ "Casting Shadows: War Crimes and Crimes against Humanity: 1978-2001" (PDF). Afghanistan Justice Project. 2005.

- ^ a b c Amnesty International. "DOCUMENT – AFGHANISTAN: FURTHER INFORMATION ON FEAR FOR SAFETY AND NEW CONCERN: DELIBERATE AND ARBITRARY KILLINGS: CIVILIANS IN KABUL." 16 November 1995 Accessed at: http://www.amnesty.org/en/library/asset/ASA11/015/1995/en/6d874caa-eb2a-11dd-92ac-295bdf97101f/asa110151995en.html

- ^ "Afghanistan: escalation of indiscriminate shelling in Kabul". International Committee of the Red Cross. 1995.

- ^ BBC Newsnight 1995 on YouTube

- ^ a b Marcela Grad. Massoud: An Intimate Portrait of the Legendary Afghan Leader (March 1, 2009 ed.). Webster University Press. p. 310.

- ^ "II. BACKGROUND". Human Rights Watch.

- ^ a b "Documents Detail Years of Pakistani Support for Taliban, Extremists". George Washington University. 2007.

- ^ Coll, Ghost Wars (New York: Penguin, 2005), 14.

- ^ a b c "The Taliban's War on Women. A Health and Human Rights Crisis in Afghanistan" (PDF). Physicians for Human Rights. 1998.

- ^ a b David Keane (Director); Aaron Bowden, Terrence Henry (Writers) (2007). Inside the Taliban. United States: National Geographic.

- ^ "History Commons". History Commons. 2010.

- ^ Maley, William (2009). The Afghanistan wars. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 288. ISBN 978-0-230-21313-5.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Lifting The Veil On Taliban Sex Slavery". Time. February 10, 2002. Retrieved 2013-01-10.

- ^ "BOOK REVIEW: The inside track on Afghan wars by Khaled Ahmed". Daily Times. 2008.

- ^ "U.S. blames Pakistan agency in Kabul attack". Reuters. September 22, 2011. Retrieved September 22, 2011.

- ^ "U.S. links Pakistan to group it blames for Kabul attack". Reuters. September 17, 2011. Retrieved September 21, 2011.

- ^ "Clinton Presses Pakistan to Help Fight Haqqani Insurgent Group". Fox News. September 18, 2011. Retrieved September 21, 2011.

- ^ "Pakistan condemns US comments about spy agency". Associated Press. September 23, 2011. Retrieved September 23, 2011.

- ^ RUBIN, ALISSA (nytimes.com). "U.S. Embassy and NATO Headquarters Attacked in Kabul". nytimes.com.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Holehouse, Matthew (13 Sept 2011). "Kabul US embassy attack: September 13 as it happened". London: telegraph.co.uk.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "At least 55 killed in Kabul suicide bombing". The Hindu. Chennai, India. December 7, 2008. Retrieved December 9, 2011.

- ^ "Photos of the Day: Dec. 8". The Wall Street Journal. December 7, 2008. Retrieved December 9, 2011.

- ^ "Corruption Perceptions Index 2010 Results". Transparency International. 2010. Retrieved February 27, 2011.

- ^ "WikiLeaks: Afghan MPs and religious scholars 'on Iran payroll'". United Kingdom: Guardian. 2 December 2010. Retrieved 2013-01-10.

- ^ "Afghans Worry About Iran's Growing Influence". Voice of America. November 27, 2012. Retrieved 2013-01-10.

Afghanistan is under the siege of Iranian influence. Nowadays we have six pro-Iranian TV channels, 21 radio stations, and a large number of publications that appear in Kabul that are pro-Iranian.

- ^ "Iran's cash to Kabul worries US". BBC News. 20 October 2010. Retrieved 2013-01-10.

The US has voiced concern about Iran's "negative influence" on Afghanistan, after Afghan President Hamid Karzai admitted receiving cash from Tehran.

- ^ "Pakistani, Afghan, and Iranian Factors of Influence on the Central Asian Region". Carnegie Council. August 17, 2009. Retrieved 2013-10-10.

- ^ "What Money Won't Buy". The New York Times. October 26, 2010. Retrieved 2013-01-10.

- ^ "Iran intensifies efforts to influence policy in Afghanistan". The Washington Post. January 4, 2012. Retrieved 2013-01-10.

- ^ "The Iranian Influence in Afghanistan". PBS. August 9, 2010. Retrieved 2013-01-10.

- ^ "Kabul Climate Normals 1956-1983". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved March 30, 2013.

- ^ Urban Development In Kabul: An Overview Of Challenges And Strategies by Dr. Annette Ittig

- ^ https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/af.html

- ^ "2003 National Geographic Population Map" (PDF). Thomas Gouttierre, Center For Afghanistan Studies, University of Nebraska at Omaha; Matthew S. Baker, Stratfor. National Geographic Society. November 2003. Retrieved 2010-06-27.

- ^ Cole, Juan (2006-05-30). "Kabul under Curfew after Anti-US, anti-Karzai Riots". San Francisco Bay Area Indymedia. Retrieved 2007-11-27.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Nakamura, David (2010-08-27). "In Afghanistan, a car for the masses". The Washington Post.

- ^ Australian Broadcasting Corporation, Dodgy cars clogging Kabul's roads

- ^ Afghanistan Industrial Parks Development Authority...Kabul (Bagrami)

- ^ Pajhwok Afghan News – Ministry signs contract with Chinese company

- ^ "Landmark Hotels and Suites". Lmhotelgroup.com. Retrieved 2012-08-17.

- ^ "車を高く売るためにこれだけは知ってほしいポイント!". Goldenstarkabul.com. Retrieved 2012-08-17.

- ^ "Heetal Group of companies". Heetal.com. Retrieved 2010-06-27.

- ^ http://www.nytimes.com/2011/05/22/world/asia/22afghanistan.html

- ^ Pajhwok Afghan News, Kabul beautification plan announced (December 17, 2007)

- ^ "Welcome to our Official Website". DCDA. Retrieved 2012-08-17.

- ^ "Onyx Construction Company". Onyx.af. Retrieved 2012-08-17.

- ^ Kabul – City of Light Project...link

Further reading

- Canadian Press (October 14, 2007). "Afghanistan Struggles to Preserve Rich Past Despite Ongoing War". Canadian Press.

- Tang, Alisa (Associated Press) (January 21, 2008). "Kabul's Old City Getting Face Lift". The Boston Globe.

- Hill, John E. (2009). Through the Jade Gate to Rome: A Study of the Silk Routes during the Later Han Dynasty, 1st to 2nd Centuries CE. BookSurge, Charleston, South Carolina. ISBN 978-1-4392-2134-1.

External links

- Images of Kabul on Panoramio

- Map of Kabul City from Afghanistan Information Management Services

- Historical Photos of Kabul

- Afghanistan 1923 - The story and photo albums of Wilhelm Rieck (at the moment only in German - English will follow.)

- People of Kabul - report by Radio France Internationale in English