Ibuprofen: Difference between revisions

Racemate |

Reverted good faith edits by Jü; We have agreed that displaying both enantiomers is unnecessary (WP:CHEMSTYLE). (TW) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{drugbox | |

{{drugbox | |

||

| IUPAC_name = (''RS'')-2-(4-isobutylphenyl)propanoic acid |

| IUPAC_name = (''RS'')-2-(4-isobutylphenyl)propanoic acid |

||

| image = Ibuprofen- |

| image = Ibuprofen-racemic-2D-skeletal.png |

||

| CAS_number = 15687-27-1 |

| CAS_number = 15687-27-1 |

||

| ChemSpiderID = 3544 |

| ChemSpiderID = 3544 |

||

Revision as of 22:00, 16 August 2009

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Oral, rectal, topical, and intravenous |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 49–73% |

| Protein binding | 99% |

| Metabolism | Hepatic (CYP2C9) |

| Elimination half-life | 1.8–2 hours |

| Excretion | Renal |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.036.152 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C13H18O2 |

| Molar mass | 206.28 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 76 °C (169 °F) |

| |

Ibuprofen (INN) (Template:Pron-en or Template:Pron-en; from the now outdated nomenclature iso-butyl-propanoic-phenolic acid) is a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) originally marketed as Brufen, and since then under various other trademarks (see tradenames section), most notably Nurofen, Advil and Motrin. It is used for relief of symptoms of arthritis, primary dysmenorrhea, fever, and as an analgesic, especially where there is an inflammatory component. Ibuprofen is known to have an antiplatelet effect, though it is relatively mild and short-lived when compared with that of aspirin or other better-known antiplatelet drugs. Ibuprofen is a core medicine in the World Health Organization's "Essential Drugs List", which is a list of minimum medical needs for a basic health care system.[2]

History

Ibuprofen was derived from propionic acid by the research arm of Boots Group during the 1960s.[3] It was discovered by Stewart Adams, with colleagues John Nicholson, Andrew RM Dunlop, Jeffery Bruce Wilson & Colin Burrows and was patented in 1961. The drug was launched as a treatment for rheumatoid arthritis in the United Kingdom in 1969, and in the United States in 1974. Famously, it is recorded that Dr. Adams initially tested his drug on a hangover. He was subsequently awarded an OBE in 1987. Boots was awarded the Queen's Award For Technical Achievement for the development of the drug in 1987.[4]

Typical administration

Low doses of ibuprofen (200 mg, and sometimes 400 mg) are available over the counter (OTC) in most countries. Ibuprofen has a dose-dependent duration of action of approximately 4–8 hours, which is longer than suggested by its short half-life. The recommended dose varies with body mass and indication. Generally, the oral dose is 200–400 mg (5–10 mg/kg in children) every 4–6 hours, adding up to a usual daily dose of 800–1200 mg. 1200 mg is considered the maximum daily dose for over-the-counter use, though under medical direction, a maximum daily dose of 3200 mg may sometimes be used in increments of 600–800 mg.

Unlike aspirin, which breaks down in solution, ibuprofen is stable, and thus ibuprofen can be available in topical gel form which is absorbed through the skin, and can be used for sports injuries, with less risk of gastrointestinal problems.[5]

Off-label and investigational use

Ibuprofen is sometimes used for the treatment of acne, because of its anti-inflammatory properties,[6] and has been sold in Japan in topical form for adult acne.[7]

As with other NSAIDs, ibuprofen may be useful in the treatment of severe orthostatic hypotension (low blood pressure when standing up).[8]

In some studies, ibuprofen showed superior results compared to a placebo in the prophylaxis of Alzheimer's disease, when given in low doses over a long time.[9] Further studies are needed to confirm the results before ibuprofen can be recommended for this indication.

Ibuprofen has been associated with a lower risk of Parkinson's disease, and may delay or prevent it. Aspirin, other NSAIDs, and paracetamol had no effect on the risk for Parkinson's.[10] Further research is warranted before recommending ibuprofen for this use.

Ibuprofen lysine

In Europe, Australia, and New Zealand, ibuprofen lysine (the lysine salt of ibuprofen, sometimes called "ibuprofen lysinate" even though the lysine is in cationic form) is licensed for treatment of the same conditions as ibuprofen. The lysine salt increases water solubility, allowing the medication to be administered intravenously.[11] Ibuprofen lysine has been shown to have a more rapid onset of action compared to acid ibuprofen.[12]

Ibuprofen lysine is indicated for closure of a patent ductus arteriosus in premature infants weighing between 500 and 1500 grams, who are no more than 32 weeks gestational age when usual medical management (e.g., fluid restriction, diuretics, respiratory support, etc.) is ineffective.[11] With regard to this indication, ibuprofen lysine is an effective alternative to intravenous indomethacin and may be advantageous in terms of renal function.[13]

Mechanism of action

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs such as ibuprofen work by inhibiting the enzyme cyclooxygenase (COX), which converts arachidonic acid to prostaglandin H2 (PGH2). PGH2, in turn, is converted by other enzymes to several other prostaglandins (which are mediators of pain, inflammation, and fever) and to thromboxane A2 (which stimulates platelet aggregation, leading to the formation of blood clots).

Like aspirin, indometacin, and most other NSAIDs, ibuprofen is considered a non-selective COX inhibitor—that is, it inhibits two isoforms of cyclooxygenase, COX-1 and COX-2. The analgesic, antipyretic, and anti-inflammatory activity of NSAIDs appears to be achieved mainly through inhibition of COX-2, whereas inhibition of COX-1 would be responsible for unwanted effects on platelet aggregation and the gastrointestinal tract.[14] However, the role of the individual COX isoforms in the analgesic, anti-inflammatory, and gastric damage effects of NSAIDs is uncertain and different compounds cause different degrees of analgesia and gastric damage.[15]

Adverse effects

Ibuprofen appears to have the lowest incidence of gastrointestinal adverse drug reactions (ADRs) of all the non-selective NSAIDs. However, this only holds true at lower doses of ibuprofen, so over-the-counter preparations of ibuprofen are generally labeled to advise a maximum daily dose of 1,200 mg.[citation needed]

Common adverse effects include: nausea, dyspepsia, gastrointestinal ulceration/bleeding, raised liver enzymes, diarrhea, epistaxis, headache, dizziness, priapism, rash, salt and fluid retention, and hypertension.[16]

Infrequent adverse effects include: oesophageal ulceration, heart failure, hyperkalaemia, renal impairment, confusion, and bronchospasm.[16]

Photosensitivity

As with other NSAIDs, ibuprofen has been reported to be a photosensitising agent.[17][18] However, this only rarely occurs with ibuprofen and it is considered to be a very weak photosensitising agent when compared with other members of the 2-arylpropionic acid class. This is because the ibuprofen molecule contains only a single phenyl moiety and no bond conjugation, resulting in a very weak chromophore system and a very weak absorption spectrum which does not reach into the solar spectrum.

Cardiovascular risk

Along with several other NSAIDs, ibuprofen has been implicated in elevating the risk of myocardial infarction, particularly among those chronically using high doses.[19]

Risks in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)

Ibuprofen should not be used regularly in individuals with inflammatory bowel disease due to its ability to cause gastric bleeding and form ulceration in the gastric lining. Pain relievers such as paracetemol/acetaminophen or drugs containing codeine (which slows down bowel activity) are safer methods than ibuprofen for pain relief in IBD. Ibuprofen is also known to cause worsening of IBD during times of a flare-up, thus should be avoided completely.

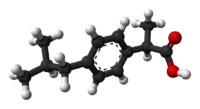

Stereochemistry

Ibuprofen, like other 2-arylpropionate derivatives (including ketoprofen, flurbiprofen, naproxen, etc), contains a stereocenter in the α-position of the propionate moiety. As such, there are two possible enantiomers of ibuprofen, with the potential for different biological effects and metabolism for each enantiomer.

Indeed it was found that (S)-(+)-ibuprofen (dexibuprofen) was the active form both in vitro and in vivo.

It was logical, then, that there was the potential for improving the selectivity and potency of ibuprofen formulations by marketing ibuprofen as a single-enantiomer product (as occurs with naproxen, another NSAID).

Further in vivo testing, however, revealed the existence of an isomerase (2-arylpropionyl-CoA epimerase) which converted (R)-ibuprofen to the active (S)-enantiomer.[20][21][22] Thus, due to the expense and futility that might be involved in making a pure enantiomer, most ibuprofen formulations currently marketed are racemic mixtures.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Water solubility

Ibuprofen is only very slightly soluble in water, less than 1 mg of ibuprofen dissolves in 1 ml water (< 1 mg/mL).[23]

Human toxicology

Ibuprofen overdose has become common since it was licensed for over-the-counter use. There are many overdose experiences reported in the medical literature, although the frequency of life-threatening complications from ibuprofen overdose is low.[24] Human response in cases of overdose ranges from absence of symptoms to fatal outcome in spite of intensive care treatment. Most symptoms are an excess of the pharmacological action of ibuprofen and include abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, drowsiness, dizziness, headache, tinnitus, and nystagmus. Rarely more severe symptoms such as gastrointestinal bleeding, seizures, metabolic acidosis, hyperkalaemia, hypotension, bradycardia, tachycardia, atrial fibrillation, coma, hepatic dysfunction, acute renal failure, cyanosis, respiratory depression, and cardiac arrest have been reported.[25] The severity of symptoms varies with the ingested dose and the time elapsed; however, individual sensitivity also plays an important role. Generally, the symptoms observed with an overdose of ibuprofen are similar to the symptoms caused by overdoses of other NSAIDs.

There is little correlation between severity of symptoms and measured ibuprofen plasma levels. Toxic effects are unlikely at doses below 100 mg/kg but can be severe above 400 mg/kg;[26] however, large doses do not indicate that the clinical course is likely to be lethal.[27] It is not possible to determine a precise lethal dose, as this may vary with age, weight, and concomitant diseases of the individual patient.

Therapy is largely symptomatic. In cases presenting early, gastric decontamination is recommended. This is achieved using activated charcoal; charcoal absorbs the drug before it can enter the systemic circulation. Gastric lavage is now rarely used, but can be considered if the amount ingested is potentially life threatening and it can be performed within 60 minutes of ingestion. Emesis is not recommended.[28] The majority of ibuprofen ingestions produce only mild effects and the management of overdose is straightforward. Standard measures to maintain normal urine output should be instituted and renal function monitored.[26] Since ibuprofen has acidic properties and is also excreted in the urine, forced alkaline diuresis is theoretically beneficial. However, due to the fact ibuprofen is highly protein bound in the blood, there is minimal renal excretion of unchanged drug. Forced alkaline diuresis is therefore of limited benefit.[29] Symptomatic therapy for hypotension, GI bleeding, acidosis, and renal toxicity may be indicated. Occasionally, close monitoring in an intensive care unit for several days is necessary. If a patient survives the acute intoxication, he/she will usually experience no late sequelae.

Availability

Ibuprofen was made available under prescription in the United Kingdom in 1969, and in the United States in 1974. In the years since, the good tolerability profile along with extensive experience in the population, as well as in so-called Phase IV trials (post-approval studies), has resulted in the availability of small packages of ibuprofen over the counter in pharmacies worldwide, as well as in supermarkets and other general retailers.

North America

In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration approved ibuprofen for over the counter use in 1984.

In Canada doses of 200 mg and 400 mg are available over the counter, with 600 mg being reserved as a prescription form that is a benefit under most Canadian prescription drug insurance plans. The 800 mg form is not available. Mexico's doses go up to 800 mg per pill.

In 2009, the first injectable formulation of ibuprofen was approved in the United States, under the trade name Caldolor. Ibuprofen thus became the only pain and fever reliever available in the country for parenteral use.[30]

Europe

For some time, there has been a limit on the amount that can be bought over the counter in a single transaction in the UK. Behind the counter in pharmacies this is one pack of 96 × 200 mg or 400 mg, the latter being far less common for over the counter sales. In UK non-pharmacy outlets only 200 mg tablets are allowed and they are restricted to a maximum pack of 16 tablets.

In Germany, 600 mg and 800 mg per pill packages have to be prescribed, whereas 400 mg is available over the counter in pharmacies.

In other countries, higher dosages of 600 mg are available.

In Italy and the Netherlands, 200 mg and 400 mg pills are available with no prescription.

Tradenames

See also

- Aspirin

- Diclofenac

- Naproxen

- Paracetamol (acetaminophen)

References

- ^ "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved 22 Oct 2023.

- ^ "WHO Model List of Essential Medicines" (PDF). World Health Organization. 2005. Retrieved 2006-03-12.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Adams SS (1992). "The propionic acids: a personal perspective". J Clin Pharmacol. 32 (4): 317–23. PMID 1569234.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Dr Stewart Adams: 'I tested ibuprofen on my hangover' - Telegraph". Retrieved 2008-01-20.

- ^ http://www.medicine.ox.ac.uk/bandolier/booth/painpag/topical/topkin.html

- ^ RC, Wong (1984). "Oral ibuprofen and tetracycline for the treatment of acne vulgaris". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/adis/inp/2006/00000001/00001530/art00048;jsessionid=1ghdlu0vup2pl.alice

- ^ Zawada E (1982). "Renal consequences of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs". Postgrad Med. 71 (5): 223–30. PMID 7041104.

- ^ Townsend KP, Praticò D (2005). "Novel therapeutic opportunities for Alzheimer's disease: focus on nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs". FASEB J. 19 (12): 1592–601. doi:10.1096/fj.04-3620rev. PMID 16195368. Retrieved 2008-12-08.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Chen H, Jacobs E, Schwarzschild M, McCullough M, Calle E, Thun M, Ascherio A (2005). "Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug use and the risk for Parkinson's disease". Ann Neurol. 58 (6): 963–7. doi:10.1002/ana.20682. PMID 16240369.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Ovation Pharmaceuticals. "Neoprofen (ibuprofen lysine) injection". Package insert. [1]

- ^ Geisslinger G, Dietzel K, Bezler H, Nuernberg B, Brune K (1989). "Therapeutically relevant differences in the pharmacokinetical and pharmaceutical behavior of ibuprofen lysinate as compared with ibuprofen acid". Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther Toxicol. 27 (7): 324–8. PMID 2777420.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Su PH, Chen JY, Su CM, Huang TC, Lee HS (2003). "Comparison of ibuprofen and indomethacin therapy for patent ductus arteriosus in preterm infants". Pediatr Int. 45 (6): 665–70. doi:10.1111/j.1442-200X.2003.01797.x. PMID 14651538.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Rao P, Knaus EE (2008). "Evolution of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs): cyclooxygenase (COX) inhibition and beyond". J Pharm Pharm Sci. 11 (2): 81s–110s. PMID 19203472.

- ^ Kakuta H, Zheng X, Oda H; et al. (2008). "Cyclooxygenase-1-selective inhibitors are attractive candidates for analgesics that do not cause gastric damage. design and in vitro/in vivo evaluation of a benzamide-type cyclooxygenase-1 selective inhibitor". J. Med. Chem. 51 (8): 2400–11. doi:10.1021/jm701191z. PMID 18363350.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Rossi S, ed. (2004). Australian Medicines Handbook (2004 ed.). Australian Medicines Handbook. ISBN 0-9578521-4-2. OCLC 224121065.

- ^ Bergner T, Przybilla B. Photosensitization caused by ibuprofen. J Am Acad Dermatol 1992;26(1):114-6. PMID 1531054

- ^ Thomson Healthcare. USP DI Advice for the Patient: Anti-inflammatory Drugs, Nonsteroidal (Systemic) [monograph on the internet]. Bethesda (MD): U.S. National Library of Medicine; c2006 [updated 2006 Jul 28; cited 2006 Aug 5]. Available from: http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/druginfo/uspdi/202743.html

- ^ Hippisley-Cox J, Coupland C (2005). "Risk of myocardial infarction in patients taking cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors or conventional non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: population based nested case-control analysis". BMJ. 330 (7504): 1366. doi:10.1136/bmj.330.7504.1366. PMID 15947398.

- ^ Chen CS, Shieh WR, Lu PH, Harriman S, Chen CY (1991). "Metabolic stereoisomeric inversion of ibuprofen in mammals". Biochim Biophys Acta. 1078 (3): 411–7. PMID 1859831.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Tracy TS, Hall SD (1992). "Metabolic inversion of (R)-ibuprofen. Epimerization and hydrolysis of ibuprofenyl-coenzyme A". Drug Metab Dispos. 20 (2): 322–7. PMID 1352228.

- ^ Reichel C, Brugger R, Bang H, Geisslinger G, Brune K (1997). "Molecular cloning and expression of a 2-arylpropionyl-coenzyme A epimerase: a key enzyme in the inversion metabolism of ibuprofen". Mol Pharmacol. 51 (4): 576–82. PMID 9106621.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Free full text - ^ Motrin (Ibuprofen) drug description - FDA approved labeling for prescription drugs and medications at RxList

- ^ McElwee NE, Veltri JC, Bradford DC, Rollins DE. (1990). "A prospective, population-based study of acute ibuprofen overdose: complications are rare and routine serum levels not warranted". Ann Emerg Med. 19 (6): 657–62. doi:10.1016/S0196-0644(05)82471-0. PMID 2188537.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Vale JA, Meredith TJ. (1986). "Acute poisoning due to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Clinical features and management". Med Toxicol. 1 (1): 12–31. PMID 3537613.

- ^ a b Volans G, Hartley V, McCrea S, Monaghan J. (2003). "Non-opioid analgesic poisoning". Clinical Medicine. 3 (2): 119–23. doi:10.1007/s10238-003-0014-z. PMID 12737366.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Seifert SA, Bronstein AC, McGuire T (2000). "Massive ibuprofen ingestion with survival". J. Toxicol. Clin. Toxicol. 38 (1): 55–7. doi:10.1081/CLT-100100917. PMID 10696926.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Position paper: Ipecac syrup". J. Toxicol. Clin. Toxicol. 42 (2): 133–43. 2004. PMID 15214617.

- ^ Hall AH, Smolinske SC, Conrad FL; et al. (1986). "Ibuprofen overdose: 126 cases". Annals of emergency medicine. 15 (11): 1308–13. doi:10.1016/S0196-0644(86)80617-5. PMID 3777588.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "FDA Approves Caldolor: Cumberland Pharmaceuticals Announces FDA Approval of Caldolor" (Press release). Drugs.com. June 11, 2009. Retrieved 2009-06-13.