DDT: Difference between revisions

←Replaced content with 'haha daniels gayyyyyyy' Tag: possible vandalism |

ClueBot NG (talk | contribs) m Reverting possible vandalism by MaxFear69 to version by Discospinster. False positive? Report it. Thanks, ClueBot NG. (1896528) (Bot) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Use mdy dates|date=April 2014}} |

|||

haha daniels gayyyyyyy |

|||

{{other uses}} |

|||

{{multiple issues| |

|||

{{globalize|date=January 2014}} |

|||

{{medref|date=January 2014}} |

|||

}} |

|||

{{Chembox |

|||

| Verifiedfields = changed |

|||

| Watchedfields = changed |

|||

| verifiedrevid = 456348813 |

|||

| Name = DDT |

|||

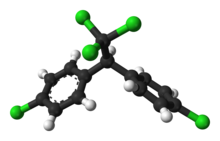

| ImageFile = p,p'-dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane.svg |

|||

| ImageSize = 200px |

|||

| ImageFile1 = DDT-from-xtal-3D-balls.png |

|||

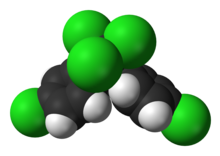

| ImageFile2 = DDT-from-xtal-3D-vdW.png |

|||

| ImageName = Chemical structure of DDT |

|||

| IUPACName = 1,1,1-Trichloro-2,2-bis(4-chlorophenyl)ethane |

|||

| Section1 = |

|||

{{Chembox Identifiers |

|||

| PubChem = 3036 |

|||

| UNII_Ref = {{fdacite|correct|FDA}} |

|||

| UNII = CIW5S16655 |

|||

| KEGG_Ref = {{keggcite|correct|kegg}} |

|||

| KEGG = D07367 |

|||

| InChI = 1/C14H9Cl5/c15-11-5-1-9(2-6-11)13(14(17,18)19)10-3-7-12(16)8-4-10/h1-8,13H |

|||

| InChIKey = YVGGHNCTFXOJCH-UHFFFAOYAJ |

|||

| ChEMBL_Ref = {{ebicite|changed|EBI}} |

|||

| ChEMBL = 416898 |

|||

| StdInChI_Ref = {{stdinchicite|correct|chemspider}} |

|||

| StdInChI = 1S/C14H9Cl5/c15-11-5-1-9(2-6-11)13(14(17,18)19)10-3-7-12(16)8-4-10/h1-8,13H |

|||

| StdInChIKey_Ref = {{stdinchicite|correct|chemspider}} |

|||

| StdInChIKey = YVGGHNCTFXOJCH-UHFFFAOYSA-N |

|||

| CASNo = 50-29-3 |

|||

| CASNo_Ref = {{cascite|correct|CAS}} |

|||

| ATCCode_prefix = P03 |

|||

| ATCCode_suffix = AB01 |

|||

| ATC_Supplemental = {{ATCvet|P53|AB01}} |

|||

| ChemSpiderID_Ref = {{chemspidercite|correct|chemspider}} |

|||

| ChemSpiderID=2928 |

|||

| ChEBI_Ref = {{ebicite|correct|EBI}} |

|||

| ChEBI = 16130 |

|||

| SMILES = Clc1ccc(cc1)C(c2ccc(Cl)cc2)C(Cl)(Cl)Cl |

|||

}} |

|||

|Section2 = |

|||

{{Chembox Properties |

|||

| C=14|H=9|Cl=5 |

|||

| Density = 0.99 g/cm³<ref name="ATSDRc5"/> |

|||

| MeltingPtC = 108.5 |

|||

| BoilingPtC = 260 |

|||

| Boiling_notes = (decomposes) |

|||

}} |

|||

|Section7 = |

|||

{{Chembox Hazards |

|||

| EUClass = {{Hazchem T}} {{Hazchem N}} |

|||

| EUIndex = |

|||

| MainHazards = Toxic, dangerous to the environment |

|||

| MainHazards = |

|||

| NFPA-H = 2 |

|||

| NFPA-F = 2 |

|||

| NFPA-R = 0 |

|||

| NFPA-S = |

|||

| RPhrases={{R25}} {{R40}} {{R48/25}} {{R50/53}} |

|||

| SPhrases={{(S1/2)}} {{S22}} {{S36/37}} {{S45}} {{S60}} {{S61}} |

|||

| LD50=113 mg/kg (rat) |

|||

}} |

|||

}} |

|||

'''DDT''' ("'''dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane'''") is a colorless, [[Crystallinity|crystalline]], tasteless and almost odorless [[organochloride]] known for its [[Insecticide|insecticidal]] properties. DDT has been formulated in almost every conceivable form, including [[solution]]s in [[xylene]] or [[petroleum]] [[Distillation|distillates]], [[Emulsion|emulsifiable]] [[concentrate]]s, water-[[wettable powder]]s, granules, [[aerosol]]s, [[Smoke bomb|smoke candles]] and charges for vaporisers and lotions.<ref name=EHC83>{{EHC-ref | id = 83 | name = DDT and Its Derivatives: Environmental Aspects | date = 1989 | isbn = 92-4-154283-7 }}</ref> |

|||

First synthesized in 1874, DDT's insecticidal action was discovered by the Swiss chemist [[Paul Hermann Müller]] in 1939. It was then used in the second half of [[World War II]] to control [[malaria]] and [[typhus]] among civilians and troops. After the war, DDT was made available for use as an agricultural insecticide and its production and use duly increased.<ref name=EHC009>{{EHC-ref | id = 009 | name = DDT and its derivatives | date = 1979 | isbn = 92-4-154069-9 }}</ref> Müller was awarded the [[Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine]] "for his discovery of the high efficiency of DDT as a contact poison against several arthropods" in 1948.<ref name=nobel>[http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/medicine/laureates/1948/ NobelPrize.org: The Nobel Prize in Physiology of Medicine 1948], accessed July 26, 2007.</ref> However, widespread agricultural use accelerated resistance among insect populations, in many cases reversing early successes against malaria-carrying mosquitos. |

|||

In 1962, the book ''[[Silent Spring]]'' by American biologist [[Rachel Carson]] was published. It catalogued the environmental impacts of indiscriminate DDT [[Aerial application|spraying]] in the United States and questioned the logic of releasing large amounts of chemicals into the environment without a sufficient understanding of their effects on [[ecology]] or human health. The book demonstrated that DDT and other pesticides had been shown to cause [[cancer]] and that their agricultural use was a threat to wildlife, particularly birds. Its publication was a seminal event for the [[Environmentalism|environmental movement]] and resulted in a large public outcry that eventually led, in 1972, to a ban on the agricultural use of DDT in the United States.<ref name="Lear"/> A worldwide ban on its agricultural use was later formalised under the [[Stockholm Convention]], but its limited use in [[Vector (epidemiology)|disease vector]] [[Vector control|control]] continues to this day and remains controversial,<ref name="Larson">{{cite journal |last=Larson |first=Kim |date=December 1, 2007 |title=Bad Blood |journal=On Earth |issue=Winter 2008 |url=http://www.onearth.org/article/bad-blood? |accessdate=June 5, 2008}}</ref><ref name=moyers>{{cite web |last=Moyers |first=Bill |author-link=Bill Moyers |title=Rachel Carson and DDT |date=September 21, 2007 |url=http://www.pbs.org/moyers/journal/09212007/profile2.html |accessdate=March 5, 2011 }}</ref> because of its initial effectiveness in reducing deaths due to malaria, as well as the [[drug resistance|pesticide resistance]] among mosquito populations it engenders after several years of use. |

|||

Along with the passage of the [[Endangered Species Act]], the US ban on DDT is cited by scientists as a major factor in the comeback of the [[bald eagle]] (the [[national bird of the United States]]) and the [[peregrine falcon]] from near-[[extinction]] in the [[contiguous United States]].<ref name="pmid17588911">{{cite journal | author = Stokstad E | title = Species conservation. Can the bald eagle still soar after it is delisted? | journal = Science | volume = 316 | issue = 5832 | pages = 1689–90 | date = June 2007 | pmid = 17588911 | doi = 10.1126/science.316.5832.1689 | url = http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/summary/316/5832/1689 }}</ref><ref name="test">[http://mdc.mo.gov/sites/default/files/resources/2010/04/4068_1693.pdf Missouri Animals of Conservation Concern], p. 30</ref> |

|||

==Properties and chemistry== |

|||

DDT is similar in structure to the insecticide [[methoxychlor]] and the [[acaricide]] [[dicofol]]. Being highly [[hydrophobic]], it is nearly [[Solubility|insoluble]] in [[Water (molecule)|water]] but has good solubility in most [[Organic chemistry|organic]] [[solvent]]s, [[fat]]s and [[Oil (liquid)|oils]]. DDT does not occur naturally, but is produced by the reaction of [[trichloroethanal|chloral]] ({{chem|CCl|3|CHO}}) with [[chlorobenzene]] ({{chem|C|6|H|5|Cl}}) in the presence of [[sulfuric acid]] as a [[catalyst]]. Trade names that DDT has been marketed under include Anofex ([[Novartis#History|Geigy Chemical Corp.]]), Cezarex, Chlorophenothane, Clofenotane, Dicophane, Dinocide, Gesarol ([[Syngenta|Syngenta Corp.]]), Guesapon, Guesarol, Gyron ([[Novartis#History|Ciba-Geigy Corp.]]), Ixodex, Neocid ([[Reckitt Benckiser|Reckitt & Colman Ltd]]), Neocidol (Ciba-Geigy Corp.) and Zerdane.<ref name=EHC009/> |

|||

===Isomers and related compounds=== |

|||

[[File:o,p'-dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane.svg|thumb|''o,p' ''-DDT, a minor component in commercial DDT.]] |

|||

Commercial DDT is a mixture of several closely–related compounds. The major component (77%) is the ''[[Arene substitution patterns|p]]'',''p' '' [[isomer]] which is pictured at the top of this article. The ''o'',''p' '' isomer (pictured to the right) is also present in significant amounts (15%). [[Dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene]] (DDE) and [[dichlorodiphenyldichloroethane]] (DDD) make up the balance. DDE and DDD are also the major [[metabolite]]s and breakdown products in the environment.<ref name=EHC009/> The term "'''total DDT'''" is often used to refer to the sum of all DDT related compounds (''p,p'-''DDT, ''o,p'-''DDT, DDE, and DDD) in a sample. |

|||

===Production and use statistics=== |

|||

From 1950 to 1980, DDT was extensively used in [[agriculture]] – more than 40,000 [[tonnes]] were used each year worldwide<ref name="Geisz">{{cite journal | author = Geisz HN, Dickhut RM, Cochran MA, Fraser WR, Ducklow HW | title = Melting glaciers: a probable source of DDT to the Antarctic marine ecosystem | journal = Environ. Sci. Technol. | volume = 42 | issue = 11 | pages = 3958–62 | year = 2008 | month = June | pmid = 18589951 | doi = 10.1021/es702919n }}</ref> – and it has been estimated that a total of 1.8 million tonnes have been produced globally since the 1940s.<ref name="ATSDRc5">[http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/toxprofiles/tp.asp?id=81&tid=20 ''Toxicological Profile: for DDT, DDE, and DDE.''] [[Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry]], September 2002.</ref> In the U.S., where it was manufactured by some 15 companies including Monsanto,<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.organicconsumers.org/corp/tokaronwar120902.cfm |title=Agribusiness, Biotechnology and War |publisher=Organicconsumers.org}}</ref> [[Novartis|Ciba]],<ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.al.com/news/mobileregister/index.ssf?/base/news/1215162908145190.xml&coll=3|title=McIntosh residents file suit against Ciba|last=DAVID|first=DAVID|date=July 4, 2008|accessdate=July 7, 2008|archiveurl = http://www.webcitation.org/5uKxNtMeS |archivedate = November 18, 2010|deadurl=no}}</ref> [[Montrose Chemical Corporation of California|Montrose Chemical Company]], Pennwalt<ref name="Oregon DEQ 2009">[http://www.deq.state.or.us/lq/ECSI/ecsidetail.asp?seqnbr=398 Environmental Cleanup Site Information Database for Arkema (former Pennwalt) facility], Oregon DEQ, April 2009.</ref> and [[Velsicol Chemical Corporation]],<ref>{{cite news |url=http://www.themorningsun.com/stories/012708/loc_tests.shtml| title=Tests shed light on how pCBSA got into St. Louis water |last=Horvath |first=Rosemary |date=January 27, 2008 |newspaper=Morning Sun |location=Michigan, United States |publisher=[[Journal Register Company]] |accessdate=May 16, 2008 |archiveurl=http://web.archive.org/web/20080705170443/http://www.themorningsun.com/stories/012708/loc_tests.shtml |archivedate=July 5, 2008 }}</ref> production peaked in 1963 at 82,000 tonnes per year.<ref name=EHC009/> More than 600,000 tonnes (1.35 billion lbs) were applied in the U.S. before the 1972 ban. Usage peaked in 1959 at about 36,000 tonnes.<ref name="EPA1975">[http://www.epa.gov/pesticides/factsheets/chemicals/ddt-brief-history-status.htm DDT Regulatory History: A Brief Survey (to 1975)], U.S. EPA, July 1975.</ref> |

|||

In 2009, 3314 tonnes were produced for the control of malaria and [[visceral leishmaniasis]], hence it still qualifies as a [[High Production Volume Chemical]]. India is the only country still manufacturing DDT, with China having ceased production in 2007.<ref name=EG.3>Report of the Third Expert Group Meeting on DDT, UNEP/POPS/DDT-EG.3/3, Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants, November 12, 2010. Available [http://chm.pops.int/Programmes/DDT/Meetings/DDTEG32010/tabid/1108/mctl/ViewDetails/EventModID/1421/EventID/116/xmid/4037/language/en-US/Default.aspx here].</ref> India is the largest consumer.<ref name="DDTBP.1/2">{{cite web|url=http://www.pops.int/documents/ddt/Global%20status%20of%20DDT%20SSC%2020Oct08.pdf|title=Global status of DDT and its alternatives for use in vector control to prevent disease|last=van den Berg|first=Henk|author2=Secretariat of the [[Stockholm Convention]]|date=October 23, 2008|publisher=[[Stockholm Convention]]/[[United Nations Environment Programme]]|accessdate=November 22, 2008|archiveurl = http://www.webcitation.org/5uKxOub8a |archivedate = November 18, 2010|deadurl=no}}</ref> |

|||

===Mechanism of insecticide action=== |

|||

In insects it opens [[Sodium channel|sodium ion channels]] in [[neuron]]s, causing them to fire spontaneously, which leads to spasms and eventual death. Insects with certain [[mutation]]s in their sodium channel [[gene]] are resistant to DDT and other similar insecticides. DDT resistance is also conferred by up-regulation of genes expressing [[cytochrome P450]] in some insect species,<ref>{{cite journal | author = Denholm I, Devine GJ, Williamson MS | title = Evolutionary genetics. Insecticide resistance on the move | journal = Science | volume = 297 | issue = 5590 | pages = 2222–3 | year = 2002 | pmid = 12351778 | doi = 10.1126/science.1077266 }}</ref> as greater quantities of some enzymes of this group accelerate metabolism of the toxin into inactive metabolites—in essence, these enzymes are natural antidotes to the poison. |

|||

In humans, however, it may affect health through [[genotoxicity]] or [[Endocrine disruptor|endocrine disruption]] (see [[#Effects on human health|Effects on human health]] below). |

|||

==History== |

|||

[[File:DDT Powder.jpg|thumb|right|Commercial product concentrate containing 50% DDT, circa 1960s]] |

|||

[[File:DDTDichlordiphényltrichloréthane7.JPG|thumb|right|Commercial product (Powder box, 50 g) containing 10% DDT; Néocide. [[Novartis|Ciba]] [[Geigy]] DDT; ''"Destroys parasites such as fleas, lice, ants, bedbugs, cockroaches, flies, etc.. Néocide Sprinkle caches of vermin and the places where there are insects and their places of passage. Leave the powder in place as long as possible." "Destroy the parasites of man and his dwelling". "Death is not instantaneous, it follows inevitably sooner or later." "French manufacturing"; "harmless to humans and warm-blooded animals" "sure and lasting effect. Odorless."'']] |

|||

DDT was first synthesized in 1874 by [[Othmar Zeidler]] under the supervision of [[Adolf von Baeyer]].<ref name=EHC009/><ref name="augustin">{{cite book |last=Augustin |first=Frank |title=Zur Geschichte des Insektizids Dichlordiphenyltrichloräthan (DDT) unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Leistung des Chemikers Paul Müller (1899–1965) |year=1993 |publisher=Medizinische Fakultät der Universität Leipzig |location=Leipzig |pages=1–77}}</ref><!--Augustin claims that Baeyer synthesized it already in 1872--> It was further described in 1929 in a dissertation by W. Bausch and in two subsequent publications in 1930.<ref>{{cite journal | author = Brand K, Bausch W | title = Über Verbindungen der Tetraaryl-butanreihe. 10. Mitteilung. Über die Reduktion organischer Halogenverbindungen und Über Verbindungen der Tetraaryl-butanreihe | journal = Journal für Praktische Chemie | volume = 127 | pages = 219 | year = 1930 | pmid = | pmc = | doi = 10.1002/prac.19301270114 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | author = Brand K, Horn O, Bausch W | title = Die elektrochemische Darstellung von 1,1,4,4-p,p′,p″,p‴-Tetraphenetyl-butin-2 und von 1,1,4,4-p,p′,p″,p‴-Tetra(chlorphenyl)-butin-2. 11. Mitteilung. Über die Reduktion organischer Halogenverbindungen und Verbindungen der Tetraarylbutanreihe | journal = Journal für Praktische Chemie | volume = 127 | pages = 240 | year = 1930 | pmid = | pmc = | doi = 10.1002/prac.19301270115 }}</ref> The insecticide properties of "multiple chlorinated aliphatic or fat-aromatic alcohols with at least one trichloromethane group" were described in a patent in 1934 by Wolfgang von Leuthold.<ref>Wolfgang von Leuthold, Schädlingsbekämpfung. DRP Nr 673246, April 27, 1934</ref> DDT's insecticidal properties were not, however, discovered until 1939 by the [[Swiss (people)|Swiss]] scientist [[Paul Hermann Müller]], who was awarded the 1948 [[Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine]] for his efforts.<ref name=nobel/> |

|||

===Use in the 1940s and 1950s=== |

|||

DDT is the best-known of several [[chlorine]]-containing pesticides used in the 1940s and 1950s. With [[pyrethrum]] in short supply, DDT was used extensively during [[World War II]] by the [[Allies of World War II|Allies]] to control the insect [[Vector (epidemiology)|vectors]] of [[typhus]] – nearly eliminating the disease in many parts of [[Europe]]. In the [[Pacific Ocean|South Pacific]], it was sprayed aerially for malaria and dengue fever control with spectacular effects. While DDT's chemical and insecticidal properties were important factors in these victories, advances in application equipment coupled with a high degree of organization and sufficient manpower were also crucial to the success of these programs.<ref name="Dunlap">{{cite book |last=Dunlap |first=Thomas R. |title=DDT: Scientists, Citizens, and Public Policy |publisher=Princeton University Press |location=New Jersey |year=1981 |isbn=978-0-691-04680-8}}</ref> In 1945, it was made available to farmers as an agricultural insecticide,<ref name=EHC009/> and it played a minor role in the final elimination of malaria in Europe and [[North America]].<ref name="Larson"/> By the time DDT was introduced in the U.S., the disease had already been brought under control by a variety of other means.<ref name="OreskesErik M. Conway2010">{{cite book |last1=Oreskes |first1=Naomi |authorlink1=Naomi Oreskes |last2=Erik M. Conway |first2=Erik M |title=[[Merchants of Doubt]]: How a Handful of Scientists Obscured the Truth on Issues from Tobacco Smoke to Global Warming |edition=First |year=2010 |publisher=Bloomsbury Press |location=San Francisco, CA |isbn=978-1-59691-610-4}}</ref> One [[Centers for Disease Control|CDC]] physician involved in the United States' DDT spraying campaign said of the effort that "we kicked a dying dog."<ref>Shah, Sonia [http://www.thenation.com/doc/20060417/shah “Don’t Blame Environmentalists for Malaria,”] The Nation. April 2006.</ref> |

|||

In 1955, the [[World Health Organization]] commenced a program to eradicate malaria worldwide, relying largely on DDT. The program was initially highly successful, eliminating the disease in "[[Taiwan]], much of the [[Caribbean]], the [[Balkans]], parts of northern Africa, the northern region of Australia, and a large swath of the South Pacific"<ref name="Gladwell">{{cite news |last=Gladwell |first=Malcolm |author-link=Malcolm Gladwell |title=The Mosquito Killer |newspaper=The New Yorker |date=July 2, 2001 |url=http://www.gladwell.com/2001/2001_07_02_a_ddt.htm}}</ref> and dramatically reducing mortality in [[Sri Lanka]] and India.<ref name=Gordon/> However widespread agricultural use led to resistant insect populations. In many areas, early victories partially or completely reversed and, in some cases, rates of transmission even increased.<ref name="pmid7278974">{{cite journal | author = Chapin G, Wasserstrom R | title = Agricultural production and malaria resurgence in Central America and India | journal = Nature | volume = 293 | issue = 5829 | pages = 181–5 | year = 1981 | pmid = 7278974 | doi = 10.1038/293181a0 }}</ref> The program was successful in eliminating malaria only in areas with "high socio-economic status, well-organized healthcare systems, and relatively less intensive or seasonal malaria transmission".<ref name="AmJTrop">{{cite journal | author = Sadasivaiah S, Tozan Y, Breman JG | title = Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) for Indoor Residual Spraying in Africa: How Can It Be Used for Malaria Control? | journal = Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. | volume = 77 | issue = Suppl 6 | pages = 249–263 | date = December 1, 2007 | pmid = 18165500 | url = http://www.ajtmh.org/cgi/content/full/77/6_Suppl/249 }}</ref> |

|||

DDT was less effective in tropical regions due to the continuous life cycle of mosquitoes and poor infrastructure. It was not applied at all in [[sub-Saharan Africa]] due to these perceived difficulties. Mortality rates in that area never declined to the same dramatic extent, and now constitute the bulk of malarial deaths worldwide, especially following the disease's resurgence as a result of resistance to drug treatments and the spread of the deadly malarial variant caused by ''[[Plasmodium falciparum]]'' {{Citation needed|date=June 2014}} . The goal of eradication was abandoned in 1969, and attention was focused on controlling and treating the disease. Spraying programs (especially using DDT) were curtailed due to concerns over safety and environmental effects, as well as problems in administrative, managerial and financial implementation, but mostly because mosquitoes were developing resistance to DDT.<ref name="pmid7278974"/> Efforts shifted from spraying to the use of [[Mosquito net|bednets]] impregnated with insecticides and other interventions.<ref name="AmJTrop"/><ref name="pmid16125595">{{cite journal | author = Rogan WJ, Chen A | title = Health risks and benefits of bis(4-chlorophenyl)-1,1,1-trichloroethane (DDT) | journal = Lancet | volume = 366 | issue = 9487 | pages = 763–73 | year = 2005 | pmid = 16125595 | doi = 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67182-6 }}</ref> |

|||

===U.S. ban=== |

|||

As early as the 1940s, scientists in the U.S. had begun expressing concern over possible hazards associated with DDT, and in the 1950s the government began tightening some of the regulations governing its use.<ref name=EPA1975/> However, these early events received little attention, and it was not until 1957, when the ''[[New York Times]]'' reported an unsuccessful struggle to restrict DDT use in [[Nassau County, New York]], that the issue came to the attention of the popular naturalist-author, [[Rachel Carson]]. [[William Shawn]], editor of ''[[The New Yorker]]'', urged her to write a piece on the subject, which developed into her famous book ''[[Silent Spring]]'', published in 1962. The book argued that [[pesticide]]s, including DDT, were poisoning both wildlife and the environment and were also endangering human health.<ref name="Lear">Lear, Linda (1997). ''Rachel Carson: Witness for Nature.'' New York: Henry Hoyten.</ref> |

|||

''Silent Spring'' was a best seller, and public reaction to it launched the modern [[environmentalism|environmental movement]] in the United States. The year after it appeared, [[John F. Kennedy|President Kennedy]] ordered his Science Advisory Committee to investigate Carson's claims. The report the committee issued "add[ed] up to a fairly thorough-going vindication of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring thesis," in the words of the journal ''[[Science (journal)|Science]]'',<ref name="pmid17810673">{{cite journal | author = Greenberg DS | title = Pesticides: White House Advisory Body Issues Report Recommending Steps to Reduce Hazard to Public | journal = Science | volume = 140 | issue = 3569 | pages = 878–9 | date = May 1963 | pmid = 17810673 | doi = 10.1126/science.140.3569.878 | url = http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=17810673 }} cited in {{cite journal |last=Graham Jr. |first=Frank |title=Nature's Protector and Provocateur |journal=Audubon Magazine |url=http://audubonmagazine.org/books/editorchoice0709.html}} {{dead link|date=November 2010}}</ref> and recommended a phaseout of "persistent toxic pesticides".<ref name="Michaels2008">{{cite book |last=Michaels |first=David |title=[[Doubt is Their Product]]: How Industry's Assault on Science Threatens Your Health|publisher=Oxford University Press|location=New York|year=2008|isbn=978-0-19-530067-3}}</ref> DDT became a prime target of the growing anti-chemical and anti-pesticide movements, and in 1967 a group of scientists and lawyers founded the [[Environmental Defense|Environmental Defense Fund]] (EDF) with the specific goal of winning a ban on DDT. [[Victor Yannacone]], Charles Wurster, [[Art Cooley]] and others associated with inception of EDF had all witnessed bird kills or declines in bird populations and suspected that DDT was the cause. In their campaign against the chemical, EDF petitioned the government for a ban and filed a series of lawsuits.<ref>{{cite news |title=Sue the Bastards |url=http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,910111-2,00.html |publisher=[[TIME]] |date=October 18, 1971 |archiveurl=http://www.webcitation.org/5uKxR0D6f |archivedate=November 18, 2010 |deadurl=no}}</ref> Around this time, [[toxicologist]] [[David Peakall]] was measuring [[Dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene|DDE]] levels in the eggs of [[peregrine falcons]] and [[California condor]]s and finding that increased levels corresponded with thinner shells. |

|||

In response to an EDF suit, the U.S. District Court of Appeals in 1971 ordered the [[United States Environmental Protection Agency|EPA]] to begin the de-registration procedure for DDT. After an initial six-month review process, [[William Ruckelshaus]], the Agency's first [[Administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency|Administrator]] rejected an immediate suspension of DDT's registration, citing studies from the EPA's internal staff stating that DDT was not an imminent danger to human health and wildlife.<ref name=EPA1975/> However, the findings of these staff members were criticized, as they were performed mostly by [[economic entomologist]]s inherited from the [[United States Department of Agriculture]], who many environmentalists felt were biased towards agribusiness and tended to minimize concerns about human health and wildlife. The decision not to ban thus created public controversy.<ref name=Dunlap/> |

|||

The EPA then held seven months of hearings in 1971–1972, with scientists giving evidence both for and against the use of DDT. In the summer of 1972, Ruckelshaus announced the cancellation of most uses of DDT – an exemption allowed for public health uses under some conditions.<ref name=EPA1975/> Immediately after the cancellation was announced, both EDF and the DDT manufacturers filed suit against the EPA, with the industry seeking to overturn the ban, and EDF seeking a comprehensive ban. The cases were consolidated, and in 1973 the [[U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia]] ruled that the EPA had acted properly in banning DDT.<ref name=EPA1975/> |

|||

The U.S. DDT ban took place amidst a growing public mistrust of industry, with the [[Surgeon General of the United States|Surgeon General]] issuing a report on the negative effects of [[smoking]] [[tobacco]] in 1964, the [[Cuyahoga River]] catching fire in 1969, the fiasco surrounding the use of [[diethylstilbestrol]] (DES), and the well-publicized decline in the [[bald eagle]] population.<ref name=Michaels2008/> |

|||

Some uses of DDT continued under the public health exemption. For example, in June 1979, the California Department of Health Services was permitted to use DDT to suppress flea vectors of [[bubonic plague]].<ref name="urlAEI – Short Publications – The Rise, Fall, Rise, and Imminent Fall of DDT">{{cite web |url=http://www.aei.org/outlook/27063 |title=AEI – Short Publications – The Rise, Fall, Rise, and Imminent Fall of DDT |archiveurl = http://www.webcitation.org/5uKxRwUwH |archivedate = November 18, 2010|deadurl=no}}</ref> DDT also continued to be produced in the US for foreign markets until as late as 1985, when over 300 tons were exported.<ref name="ATSDRc5"/> |

|||

===Restrictions on usage=== |

|||

In the 1970s and 1980s, agricultural use was banned in most developed countries, beginning with [[Hungary]] in 1968<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.fvm.hu/main.php?folderID=1564&articleID=6169&ctag=articlelist&iid=1&part=2 |title=Selected passages from the history of the Hungarian plant protection administration on the 50th anniversary of establishing the county plant protection stations}}</ref> then in [[Norway]] and [[Sweden]] in 1970, [[Germany]] and the United States in 1972, but not in the [[United Kingdom]] until 1984. Vector control use has not been banned, but it has been largely replaced by less persistent alternative insecticides. |

|||

The [[Stockholm Convention]], which took effect in 2004, outlawed several [[persistent organic pollutant]]s, and restricted DDT use to [[vector control]]. The Convention has been ratified by more than 170 countries and is endorsed by most environmental groups. Recognizing that total elimination in many malaria-prone countries is currently unfeasible because there are few affordable or effective alternatives, public health use is exempt from the ban pending acceptable alternatives. Malaria Foundation International states, "The outcome of the treaty is arguably better than the status quo going into the negotiations. For the first time, there is now an insecticide which is restricted to vector control only, meaning that the selection of resistant mosquitoes will be slower than before."<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.malaria.org/DDTpage.html |title=MFI second page |publisher=Malaria Foundation International |accessdate=March 15, 2006 |archiveurl=http://www.webcitation.org/5uKxTLPxl |archivedate=November 18, 2010 |deadurl=no}}</ref> |

|||

Despite the worldwide ban, agricultural use continues in India,<ref>{{cite news |title=Concern over excessive DDT use in Jiribam fields |agency=The Imphal Free Press |date=May 5, 2008 |url=http://www.kanglaonline.com/index.php?template=headline&newsid=42015&typeid=1 |accessdate=May 5, 2008 |archiveurl= http://web.archive.org/web/20081206120016/http://www.kanglaonline.com/index.php?template=headline&newsid=42015&typeid=1 |archivedate=December 6, 2008}}</ref> North Korea, and possibly elsewhere.<ref name="DDTBP.1/2"/> |

|||

Today, about 3,000 to 4,000 [[tonnes]] of DDT are produced each year for disease [[vector control]].<ref name=EG.3/> DDT is applied to the inside walls of homes to kill or repel mosquitoes. This intervention, called [[indoor residual spraying]] (IRS), greatly reduces environmental damage. It also reduces the incidence of DDT resistance.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.malaria.org/DDTcosts.html |title=Is DDT still effective and needed in malaria control? |publisher=Malaria Foundation International |accessdate=March 15, 2006 |archiveurl=http://www.webcitation.org/5uKxTzvxt |archivedate=November 18, 2010 |deadurl=no}}</ref> For comparison, treating {{convert|40|ha|acre}} of cotton during a typical U.S. growing season requires the same amount of chemical as roughly 1,700 homes.<ref name="Roberts 1997">{{cite journal | author = Roberts DR, Laughlin LL, Hsheih P, Legters LJ | title = DDT, global strategies, and a malaria control crisis in South America | journal = Emerging Infectious Diseases | volume = 3 | issue = 3 | pages = 295–302 | date = July–September 1997 | pmid = 9284373 | pmc = 2627649 | doi = 10.3201/eid0303.970305 | url = http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/eid/vol3no3/roberts.htm }}</ref> |

|||

==Environmental impact== |

|||

[[File:DDT to DDD and DDE.svg|thumb|upright=1.8|Degradation of DDT to form DDE (by elimination of HCl, left) and DDD (by reductive dechlorination, right)]] |

|||

DDT is a [[persistent organic pollutant]] that is readily adsorbed to [[soil]]s and [[sediment]]s, which can act both as sinks and as long-term sources of exposure contributing to terrestrial organisms.<ref name=EHC83/> Depending on conditions, its soil [[half life]] can range from 22 days to 30 years. Routes of loss and degradation include runoff, volatilization, [[photolysis]] and [[aerobic organism|aerobic]] and [[Anaerobic digestion|anaerobic]] [[biodegradation]]. Due to [[hydrophobic]] properties, in [[aquatic ecosystem]]s DDT and its metabolites are absorbed by aquatic organisms and adsorbed on suspended particles, leaving little DDT dissolved in the water itself. Its breakdown products and metabolites, DDE and DDD, are also highly persistent and have similar chemical and physical properties.<ref name="ATSDRc5"/> DDT and its breakdown products are transported from warmer regions of the world to the [[Arctic]] by the phenomenon of [[global distillation]], where they then accumulate in the region's [[food web]].<ref>{{cite journal |title=The Grasshopper Effect and Tracking Hazardous Air Pollutants |journal=The Science and the Environment Bulletin |publisher=Environment Canada |issue=May/June 1998 |url=http://www.ec.gc.ca/science/sandemay/PrintVersion/print2_e.html}}{{dead link|date=November 2009}}</ref> |

|||

Because of its [[Lipophilicity|lipophilic]] properties, DDT has a high potential to [[bioaccumulate]], especially in [[predatory birds]].<ref>{{cite book |title=Introduction to Ecotoxicology |publisher=Blackwell Science |year=1999 |isbn=0-632-03852-7 |page=68 |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=X-ik73-vnXAC&pg=PA68 | last1=Connell | first = D. |author2=et al. }}</ref> DDT, DDE, and DDD [[biomagnification|magnify]] through the [[food chain]], with [[apex predator]]s such as [[raptor birds]] concentrating more chemicals than other animals in the same environment. They are very lipophilic and are stored mainly in body [[fat]]. DDT and DDE are very resistant to metabolism; in humans, their half-lives are 6 and up to 10 years, respectively. In the United States, these chemicals were detected in almost all human blood samples tested by the [[Centers for Disease Control]] in 2005, though their levels have sharply declined since most uses were banned in the US.<ref name="PineRiver">{{cite journal | author = Eskenazi B, Chevrier J, Rosas LG, Anderson HA, Bornman MS, Bouwman H, Chen A, Cohn BA, de Jager C, Henshel DS, Leipzig F, Leipzig JS, Lorenz EC, Snedeker SM, Stapleton D | title = The Pine River statement: human health consequences of DDT use | journal = [[Environmental Health Perspectives|Environ. Health Perspect.]] | volume = 117 | issue = 9 | pages = 1359–67 | year = 2009 | pmid = 19750098 | pmc = 2737010 | doi = 10.1289/ehp.11748 }}</ref> Estimated dietary intake has also declined,<ref name="PineRiver"/> although FDA food tests commonly detect it.<ref>USDA, ''Pesticide Data Program Annual Summary Calendar Year 2005'', November 2006.</ref> |

|||

Marine macroalgae ([[seaweed]]) help [[Bioremediation|reduce]] soil toxicity by up to 80% within six weeks.<ref>{{cite journal |doi=10.1002/jctb.1032 |last1 = Kantachote |first1=D |year=2004 |last2=Naidu |first2=R |last3=Williams |first3=B |last4=McClure |first4=N |last5=Megharaj |first5=M |last6=Singleton |first6=I |title=Bioremediation of DDT-contaminated soil: enhancement by seaweed addition |journal=Journal of Chemical Technology & Biotechnology |volume=79 |issue=6 |pages=632–8 }}</ref> |

|||

===Effects on wildlife and eggshell thinning=== |

|||

DDT is toxic to a wide range of living organisms, including marine animals such as [[crayfish]], [[daphnia|daphnids]], [[shrimp|sea shrimp]] and many species of [[fish]]. It is less toxic to mammals, but may be moderately toxic to some [[amphibian]] species, especially in the [[larvae|larval]] stage {{Citation needed|date=June 2014}} . DDT, through its metabolite DDE ([[dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene]]), caused eggshell thinning and resulted in severe population declines in multiple North American and European [[bird of prey]] species.<ref name="Vos">{{cite journal | author = Vos JG, Dybing E, Greim HA, Ladefoged O, Lambré C, Tarazona JV, Brandt I, Vethaak AD | title = Health effects of endocrine-disrupting chemicals on wildlife, with special reference to the European situation | journal = Crit Rev Toxicol | volume = 30 | issue = 1 | pages = 71–133 | year = 2000 | pmid = 10680769 | doi = 10.1080/10408440091159176 }}</ref> Eggshell thinning lowers the reproductive rate of certain bird species by causing egg breakage and embryo deaths. DDE related eggshell thinning is considered a major reason for the decline of the [[bald eagle]],<ref name="pmid17588911"/> [[brown pelican]],<ref>"Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; 12-Month Petition Finding and Proposed Rule To Remove the Brown Pelican (Pelecanus occidentalis) From the Federal List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife; Proposed Rule," Fish and Wildlife Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, February 20, 2008. {{Federal Register|73|9407}}</ref> [[peregrine falcon]], and [[osprey]].<ref name="ATSDRc5"/> However, different groups of birds vary greatly in their sensitivity to these chemicals.<ref name=EHC83/> [[Birds of prey]], [[waterfowl]], and [[passerine|song birds]] are more susceptible to [[eggshell]] thinning than [[chicken]]s and [[Galliformes|related species]], and DDE appears to be more potent than DDT.<ref name="ATSDRc5"/> Even in 2010, more than forty years after the U.S. ban, [[California condor]]s which feed on sea lions at [[Big Sur]] which in turn feed in the Palos Verdes Shelf area of the [[Montrose_Chemical_Corporation_of_California|Montrose Chemical]] [[Superfund]] site seemed to be having continued thin-shell problems. Scientists with the [[Ventana Wildlife Society]] and others are intensifying studies and remediations of the condors' problems.<ref>Moir, John, [http://www.nytimes.com/2010/11/16/science/16condors.html?hpw "New Hurdle for California Condors May Be DDT From Years Ago"], ''The New York Times'', November 15, 2010. Retrieved November 15, 2010.</ref> |

|||

The biological thinning mechanism is not entirely known, but there is strong evidence that p,p'-DDE inhibits [[calcium ATPase]] in the [[Biological membrane|membrane]] of the shell gland and reduces the transport of [[calcium carbonate]] from [[blood]] into the eggshell gland. This results in a dose-dependent thickness reduction.<ref name="ATSDRc5"/><ref>{{cite book | last1 = Walker | first1 = C.H. |author2=et al. |title=Principles of ecotoxicology |publisher=CRC/Taylor & Francis |location=Boca Raton, FL |year=2006 |isbn=978-0-8493-3635-5 |edition=3rd}}</ref><ref name="Guillette, 2006">{{cite web |last=Guillette |first=Louis J., Jr. |year=2006 |url=http://www.ehponline.org/members/2005/8045/8045.pdf |format=PDF |title=Endocrine Disrupting Contaminants |accessdate=February 2, 2007 |archiveurl=http://www.webcitation.org/5uKxWWYm0 |archivedate=November 18, 2010 |deadurl=no}}</ref><ref name="Lundholm, 1997">{{cite journal | author = Lundholm CD | title = DDE-induced eggshell thinning in birds | journal = Comp Biochem Physiol C Pharmacol Toxicol Endocrinol | volume = 118 | issue = 2 | pages = 113–28 | year = 1997 | pmid = 9490182 | doi = 10.1016/S0742-8413(97)00105-9 }}</ref> There is also evidence that o,p'-DDT disrupts female reproductive tract development, impairing eggshell quality later.<ref name="pmid17022422">{{cite journal | author = Holm L, Blomqvist A, Brandt I, Brunström B, Ridderstråle Y, Berg C | title = Embryonic exposure to o,p'-DDT causes eggshell thinning and altered shell gland carbonic anhydrase expression in the domestic hen | journal = Environ. Toxicol. Chem. | volume = 25 | issue = 10 | pages = 2787–93 | date = October 2006 | pmid = 17022422 | doi = 10.1897/05-619R.1 }}</ref> Multiple mechanisms may be at work, or different mechanisms may operate in different species.<ref name="ATSDRc5"/> Some studies show that although DDE levels have fallen dramatically, eggshell thickness remains 10–12 percent thinner than before DDT was first used.<ref>[http://www.fws.gov/contaminants/examples/AlaskaPeregrine.cfm Contaminants and Birds. Monitoring Contaminants in Arctic and American Peregrine Falcons in Alaska], U.S. Fish & Wildlife service, Division of Environmental Quality, Skip Ambrose, Northern Alaska Field Office, Fairbanks, Alaska</ref> |

|||

==Effects on human health== |

|||

[[File:DDT WWII soldier.jpg|thumb|A US soldier is demonstrating DDT hand-spraying equipment. DDT was used to control the spread of [[typhus]]-carrying [[lice]].]] |

|||

Potential mechanisms of action on humans are genotoxicity and endocrine disruption. DDT can be directly [[Genotoxicity|genotoxic]],<ref name="Cohn07">{{cite journal | author = Cohn BA, Wolff MS, Cirillo PM, Sholtz RI | title = DDT and breast cancer in young women: new data on the significance of age at exposure | journal = Environ. Health Perspect. | volume = 115 | issue = 10 | pages = 1406–14 | date = October 2007 | pmid = 17938728 | pmc = 2022666 | doi = 10.1289/ehp.10260 }}</ref> but may also induce [[enzyme]]s to produce other genotoxic intermediates and [[DNA adduct]]s.<ref name=Cohn07/> It is an endocrine disruptor. The DDT metabolite [[Dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene|DDE]] acts as an [[antiandrogen]], but not as an [[estrogen]]. p,p'-DDT, DDT's main component, has little or no androgenic or estrogenic activity.<ref name=Cohn07/> The minor component o,p'-DDT has weak estrogenic activity. |

|||

===Acute toxicity=== |

|||

DDT is classified as "moderately toxic" by the United States [[National Toxicology Program]] (NTP)<ref>[http://pesticideinfo.org/Detail_Chemical.jsp?Rec_Id=PC33482 Pesticideinfo.org]</ref> and "moderately hazardous" by the [[World Health Organization]] (WHO), based on the rat oral {{LD50}} of 113 mg/kg.<ref name = "zvgfrt"> |

|||

World Health Organization, [http://www.who.int/ipcs/publications/pesticides_hazard_rev_3.pdf ''The WHO Recommended Classification of Pesticides by Hazard''], 2005.</ref> DDT has on rare occasions been administered orally as a treatment for [[barbiturate]] poisoning.<ref><!--not about toxicity?:-->{{cite journal | author = Rappolt RT | title = Use of oral DDT in three human barbiturate intoxications: hepatic enzyme induction by reciprocal detoxicants | journal = Clin Toxicol | volume = 6 | issue = 2 | pages = 147–51 | year = 1973 | pmid = 4715198 | doi = 10.3109/15563657308990512 }}</ref> |

|||

===Chronic toxicity=== |

|||

====Diabetes==== |

|||

DDT and DDE have been linked to [[diabetes]]. A number of studies from the US, Canada, and Sweden have found that the prevalence of the disease in a population increases with serum DDT or DDE levels.<ref>{{cite journal | author = Jones OA, Maguire ML, Griffin JL | title = Environmental pollution and diabetes: a neglected association | journal = Lancet | volume = 371 | issue = 9609 | pages = 287–8 | date = January 26, 2008 | pmid = 18294985 | doi = 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60147-6 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | author = Turyk M, Anderson H, Knobeloch L, Imm P, Persky V | title = Organochlorine Exposure and Incidence of Diabetes in a Cohort of Great Lakes Sport Fish Consumers | journal = Environ. Health Perspect. | volume = 117 | issue = 7 | pages = 1076–1082 | date = March 6, 2009 | pmid = 19654916 | pmc = 2717133 | doi = 10.1289/ehp.0800281 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | author = Codru N, Schymura MJ, Negoita S, Rej R, Carpenter DO | title = Diabetes in Relation to Serum Levels of Polychlorinated Biphenyls and Chlorinated Pesticides in Adult Native Americans | journal = Environ. Health Perspect. | volume = 115 | issue = 10 | pages = 1442–7 | year = 2007 | pmid = 17938733 | pmc = 2022671 | doi = 10.1289/ehp.10315 | author4 = Akwesasne Task Force on Environment | last6 = Carpenter | archivedate = November 18, 2010 | last3 = Negoita | archiveurl = http://www.webcitation.org/5uKxaOQ37 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | author = Cox S, Niskar AS, Narayan KM, Marcus M | title = Prevalence of Self-Reported Diabetes and Exposure to Organochlorine Pesticides among Mexican Americans: Hispanic Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1982–1984 | journal = Environ. Health Perspect | volume = 115 | issue = 12 | pages = 1747–52 | year = 2007 | pmid = 18087594 | pmc = 2137130 | doi = 10.1289/ehp.10258 }}</ref><ref name="pmid19654916">{{cite journal | author = Turyk M, Anderson H, Knobeloch L, Imm P, Persky V | title = Organochlorine exposure and incidence of diabetes in a cohort of Great Lakes sport fish consumers | journal = Environ. Health Perspect. | volume = 117 | issue = 7 | pages = 1076–82 | date = July 2009 | pmid = 19654916 | pmc = 2717133 | doi = 10.1289/ehp.0800281 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | author = Philibert A, Schwartz H, Mergler D | title = An Exploratory Study of Diabetes in a First Nation Community with Respect to Serum Concentrations of p,p'-DDE and PCBs and Fish Consumption | journal = Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health | volume = 6 | issue = 12 | pages = 3179–89 | date = December 11, 2009 | pmid = 20049255 | pmc = 2800343 | doi = 10.3390/ijerph6123179 | url = http://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/6/12/3179 | archiveurl = http://www.webcitation.org/5uKxcpvRO | deadurl = no | archivedate = November 18, 2010 }}</ref> |

|||

====Developmental toxicity==== |

|||

DDT and DDE, like other organochlorines, have been shown to have [[estrogen|xenoestrogenic]] activity, meaning they are chemically similar enough to estrogens to trigger hormonal responses in animals. This [[endocrine disruptor|endocrine disrupting]] activity has been observed in [[mouse|mice]] and [[rat]] toxicological studies, and available [[epidemiological]] evidence indicates that these effects may be occurring in humans as a result of DDT exposure. The US [[United States Environmental Protection Agency|Environmental Protection Agency]] states that DDT exposure damages the reproductive system and reduces reproductive success. These effects may cause developmental and reproductive toxicity: |

|||

* A review article in ''[[The Lancet]]'' states, "research has shown that exposure to DDT at amounts that would be needed in malaria control might cause preterm birth and early weaning ... toxicological evidence shows [[endocrine disruptor|endocrine-disrupting]] properties; human data also indicate possible disruption in semen quality, menstruation, gestational length, and duration of lactation."<ref name="pmid16125595"/> |

|||

* Human epidemiological studies suggest that exposure is a risk factor for premature birth and low birth weight, and may harm a mother's ability to [[lactation|breast feed]].<ref name="Rogan&Ragan">{{cite journal | author = Rogan WJ, Ragan NB | title = Evidence of effects of environmental chemicals on the endocrine system in children | journal = Pediatrics | volume = 112 | issue = 1 Pt 2 | pages = 247–52 | year = 2003 | pmid = 12837917 | doi = 10.1542/peds.112.1.S1.247 | url = http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=12837917 }}</ref> Some 21st-century researchers argue that these effects may increase infant deaths, offsetting any anti-malarial benefits.<ref>{{cite journal | author = Chen A, Rogan WJ | title = Nonmalarial infant deaths and DDT use for malaria control | journal = Emerging Infect. Dis. | volume = 9 | issue = 8 | pages = 960–4 | year = 2003 | pmid = 12967494 | pmc = 3020610 | doi = 10.3201/eid0908.030082 | url = http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/EID/vol9no8/03-0082.htm }}<br />{{cite journal | author = Roberts D, Curtis C, Tren R, Sharp B, Shiff C, Bate R | title = Malaria control and public health | journal = Emerging Infect. Dis. | volume = 10 | issue = 6 | pages = 1170–1; author reply 1171–2 | year = 2004 | pmid = 15224677 | pmc = 3323159 | doi = 10.3201/eid1006.030787 | url = http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/eid/vol10no6/03-0787_03-1116.htm }}<!-- Includes author reply --></ref> A 2008 study, however, failed to confirm the association between exposure and difficulty breastfeeding.<ref>{{cite journal | author = Cupul-Uicab LA, Gladen BC, Hernández-Avila M, Weber JP, Longnecker MP | title = DDE, a Degradation Product of DDT, and Duration of Lactation in a Highly Exposed Area of Mexico | journal = Environ. Health Perspect. | volume = 116 | issue = 2 | pages = 179–183 | year = 2008 | pmid = 18288315 | pmc = 2235222 | doi = 10.1289/ehp.10550 }}</ref> |

|||

* Several recent studies demonstrate a link between ''in utero'' exposure to DDT or DDE and developmental neurotoxicity in humans. For example, a 2006 [[University of California, Berkeley]] study suggests that children exposed while in the womb have a greater chance of development problems,<ref>{{cite news| url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/health/5145450.stm|title=DDT 'link' to slow child progress| publisher = BBC| accessdate=July 5, 2006 |date=July 5, 2006 |work=BBC News}}</ref> and other studies have found that even low levels of DDT or DDE in [[umbilical cord]] serum at birth are associated with decreased attention at infancy<ref>{{cite journal | author = Sagiv SK, Nugent JK, Brazelton TB, Choi AL, Tolbert PE, Altshul LM, Korrick SA | title = Prenatal organochlorine exposure and measures of behavior in infancy using the Neonatal Behavioral Assessment Scale (NBAS) | journal = Environ. Health Perspect. | volume = 116 | issue = 5 | pages = 666–73 | date = May 2008 | pmid = 18470320 | pmc = 2367684 | doi = 10.1289/ehp.10553 | url = http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2367684/ }}</ref> and decreased cognitive skills at 4 years of age.<ref>{{cite journal | author = Ribas-Fitó N, Torrent M, Carrizo D, Muñoz-Ortiz L, Júlvez J, Grimalt JO, Sunyer J | title = In utero exposure to background concentrations of DDT and cognitive functioning among preschoolers | journal = Am. J. Epidemiol. | volume = 164 | issue = 10 | pages = 955–62 | year = 2006 | pmid = 16968864 | doi = 10.1093/aje/kwj299 }}</ref> Similarly, Mexican researchers have linked first trimester DDE exposure to [[psychomotor retardation|retarded psychomotor development]].<ref>{{cite journal | author = Torres-Sánchez L, Rothenberg SJ, Schnaas L, Cebrián ME, Osorio E, Del Carmen Hernández M, García-Hernández RM, Del Rio-Garcia C, Wolff MS, López-Carrillo L | title = In utero p, p'-DDE exposure and infant neurodevelopment: a perinatal cohort in Mexico | journal = Environ. Health Perspect. | volume = 115 | issue = 3 | pages = 435–9 | year = 2007 | pmid = 17431495 | pmc = 1849908 | doi = 10.1289/ehp.9566 }}</ref> |

|||

* Other studies document decreases in semen quality among men with high exposures (generally from IRS).<ref name="pmid20053623">{{cite journal | author = Jurewicz J, Hanke W, Radwan M, Bonde JP | title = Environmental factors and semen quality | journal = Int J Occup Med Environ Health | volume = 22 | issue = 4 | pages = 1–25 | date = January 2010 | pmid = 20053623 | doi = 10.2478/v10001-009-0036-1 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | author = Aneck-Hahn NH, Schulenburg GW, Bornman MS, Farias P, de Jager C | title = Impaired semen quality associated with environmental DDT exposure in young men living in a malaria area in the Limpopo Province, South Africa | journal = J. Androl. | volume = 28 | issue = 3 | pages = 423–34 | year = 2007 | pmid = 17192596 | doi = 10.2164/jandrol.106.001701 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | author = De Jager C, Farias P, Barraza-Villarreal A, Avila MH, Ayotte P, Dewailly E, Dombrowski C, Rousseau F, Sanchez VD, Bailey JL | title = Reduced seminal parameters associated with environmental DDT exposure and p,p'-DDE concentrations in men in Chiapas, Mexico: a cross-sectional study | journal = J. Androl. | volume = 27 | issue = 1 | pages = 16–27 | year = 2006 | pmid = 16400073 | doi = 10.2164/jandrol.05121 }}</ref> |

|||

* Studies generally find that high blood DDT or DDE levels do not increase time to pregnancy (TTP.)<ref name="pmid19092487">{{cite journal | author = Harley KG, Marks AR, Bradman A, Barr DB, Eskenazi B | title = DDT Exposure, Work in Agriculture, and Time to Pregnancy Among Farmworkers in California | journal = J. Occup. Environ. Med. | volume = 50 | issue = 12 | pages = 1335–42 | date = December 2008 | pmid = 19092487 | pmc = 2684791 | doi = 10.1097/JOM.0b013e31818f684d | url = http://meta.wkhealth.com/pt/pt-core/template-journal/lwwgateway/media/landingpage.htm?an=00043764-200812000-00003 | archiveurl = http://www.webcitation.org/5uKxdeKko | deadurl = no | archivedate = November 18, 2010 }}</ref> There is some evidence that the daughters of highly exposed women may have more difficulty getting pregnant (i.e. increased TTP).<ref>{{cite journal | author = Cohn BA, Cirillo PM, Wolff MS, Schwingl PJ, Cohen RD, Sholtz RI, Ferrara A, Christianson RE, van den Berg BJ, Siiteri PK | title = DDT and DDE exposure in mothers and time to pregnancy in daughters | journal = Lancet | volume = 361 | issue = 9376 | pages = 2205–6 | year = 2003 | pmid = 12842376 | doi = 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13776-2 }}</ref> |

|||

* DDT is associated with early pregnancy loss, a type of [[miscarriage]]. A prospective cohort study of Chinese textile workers found "a positive, monotonic, exposure-response association between preconception serum total DDT and the risk of subsequent early pregnancy losses."<ref>{{cite journal | author = Venners SA, Korrick S, Xu X, Chen C, Guang W, Huang A, Altshul L, Perry M, Fu L, Wang X | title = Preconception serum DDT and pregnancy loss: a prospective study using a biomarker of pregnancy | journal = Am. J. Epidemiol. | volume = 162 | issue = 8 | pages = 709–16 | year = 2005 | pmid = 16120699 | doi = 10.1093/aje/kwi275 }}</ref> The median serum DDE level of study group was lower than that typically observed in women living in homes sprayed with DDT.<ref>{{cite journal | author = Longnecker MP | title = Invited Commentary: Why DDT matters now | journal = Am. J. Epidemiol. | volume = 162 | issue = 8 | pages = 726–8 | year = 2005 | pmid = 16120697 | doi = 10.1093/aje/kwi277 }}</ref> |

|||

* A Japanese study of [[congenital hypothyroidism]] concluded that ''in utero'' DDT exposure may affect [[thyroid]] [[hormone]] levels and "play an important role in the incidence and/or causation of [[cretinism]]."<ref name="pmid17307219">{{cite journal | author = Nagayama J, Kohno H, Kunisue T, Kataoka K, Shimomura H, Tanabe S, Konishi S | title = Concentrations of organochlorine pollutants in mothers who gave birth to neonates with congenital hypothyroidism | journal = Chemosphere | volume = 68 | issue = 5 | pages = 972–6 | year = 2007 | pmid = 17307219 | doi = 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2007.01.010 | url = http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0045-6535(07)00040-9 }}</ref> Other studies have also found that DDT or DDE interfere with proper thyroid function.<ref name="pmid17933884">{{cite journal | author = Alvarez-Pedrerol M, Ribas-Fitó N, Torrent M, Carrizo D, Grimalt JO, Sunyer J | title = Effects of PCBs, p,p'-DDT, p,p'-DDE, HCB and {beta}-HCH on thyroid function in preschoolers | journal = Occup Environ Med | volume = 65 | issue = 7 | pages = 452–7 | date = October 2007 | pmid = 17933884 | doi = 10.1136/oem.2007.032763 }}</ref><ref name="pmid18560538">{{cite journal | author = Schell LM, Gallo MV, Denham M, Ravenscroft J, DeCaprio AP, Carpenter DO | title = Relationship of Thyroid Hormone Levels to Levels of Polychlorinated Biphenyls, Lead, p, p'- DDE, and Other Toxicants in Akwesasne Mohawk Youth | journal = [[Environ Health Perspect]] | volume = 116 | issue = 6 | pages = 806–13 | date = June 2008 | pmid = 18560538 | pmc = 2430238 | doi = 10.1289/ehp.10490 }}</ref> |

|||

====Other==== |

|||

Occupational exposure in agriculture and malaria control has been linked to neurological problems (for example, [[Parkinson's disease]])<ref>{{cite journal | author = van Wendel de Joode B, Wesseling C, Kromhout H, Monge P, García M, Mergler D | title = Chronic nervous-system effects of long-term occupational exposure to DDT | journal = Lancet | volume = 357 | issue = 9261 | pages = 1014–6 | year = 2001 | pmid = 11293598 | doi = 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04249-5 }}</ref> and [[asthma]].<ref>Anthony J Brown, [http://www.sciam.com/article.cfm?alias=pesticide-exposure-tied-t&chanId=sa003&modsrc=reuters Pesticide Exposure Linked to Asthma], Scientific American, September 17, 2007.</ref> |

|||

A 2014 study in ''JAMA Neurology'' reported that DDT levels were elevated 3.8 fold in Alzheimer's disease patients compared with healthy controls.<ref>Gallagher, James [http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-25913568 "DDT:Pesticide linked to Alzheimer's"] BBC News 1/27/14,</ref> |

|||

===Carcinogenicity=== |

|||

In 2002, the Centers for Disease Control reported that "Overall, in spite of some positive associations for some cancers within certain subgroups of people, there is no clear evidence that exposure to DDT/DDE causes cancer in humans."<ref name="ATSDRc5"/> The NTP classifies it as "reasonably anticipated to be a carcinogen," the [[International Agency for Research on Cancer]] classifies it as a "possible" human carcinogen, and the EPA classifies DDT, DDE, and DDD as class B2 "probable" [[carcinogen]]s. These evaluations are based mainly on the results of animal studies.<ref name="ATSDRc5"/><ref name="pmid16125595"/> |

|||

More recent evidence from [[Epidemiology|epidemiological]] studies indicates that DDT causes cancers [[Liver cancer|of the liver]],<ref name="pmid16125595"/><ref name="PineRiver"/> [[Pancreatic cancer|pancreas]]<ref name="pmid16125595"/><ref name="PineRiver"/> and [[Breast cancer|breast]].<ref name="PineRiver"/> There is mixed evidence that it contributes to [[leukemia]],<ref name="PineRiver"/> [[lymphoma]]<ref name="PineRiver"/><ref>{{cite journal | author = Spinelli JJ, Ng CH, Weber JP, Connors JM, Gascoyne RD, Lai AS, Brooks-Wilson AR, Le ND, Berry BR, Gallagher RP | title = Organochlorines and risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma | journal = Int. J. Cancer | volume = 121 | issue = 12 | pages = 2767–75 | date = December 15, 2007 | pmid = 17722095 | doi = 10.1002/ijc.23005 | display-authors = 9 }}</ref> and [[testicular cancer]].<ref name="pmid16125595"/><ref name="PineRiver"/><ref>{{cite journal | author = McGlynn KA, Quraishi SM, Graubard BI, Weber JP, Rubertone MV, Erickson RL | title = Persistent Organochlorine Pesticides and Risk of Testicular Germ Cell Tumors | journal = Journal of the National Cancer Institute | volume = 100 | issue = 9 | pages = 663–71 | date = April 29, 2008 | pmid = 18445826 | doi = 10.1093/jnci/djn101 | url = http://jnci.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/content/abstract/djn101v1 }}</ref> Other epidemiological studies suggest that DDT/DDE does not cause [[multiple myeloma]],<ref name="pmid16125595"/> or cancers [[Prostate cancer|of the prostate]],<ref name="pmid16125595"/> [[Endometrial cancer|endometrium]],<ref name="pmid16125595"/><ref name="PineRiver"/> [[Colorectal cancer|rectum]],<ref name="pmid16125595"/><ref name="PineRiver"/> [[Lung cancer|lung]],<ref name="PineRiver"/> [[bladder cancer|bladder]],<ref name="PineRiver"/> or [[Stomach cancer|stomach]].<ref name="PineRiver"/> |

|||

====Breast cancer==== |

|||

The question of whether DDT or DDE are [[Risk factors for breast cancer|risk factors in breast cancer]] has been repeatedly studied. While individual studies conflict, the most recent reviews of all the evidence conclude that pre-puberty exposure increases the risk of subsequent breast cancer.<ref name="PineRiver"/><ref name="pmid18557596">{{cite journal | author = Clapp RW, Jacobs MM, Loechler EL | title = Environmental and occupational causes of cancer: new evidence 2005–2007 | journal = Rev Environ Health | volume = 23 | issue = 1 | pages = 1–37 | year = 2008 | pmid = 18557596 | pmc = 2791455 | doi = 10.1515/REVEH.2008.23.1.1 }}</ref> Until recently, almost all studies measured DDT or DDE blood levels at the time of breast cancer diagnosis or after. This study design has been criticized, since the levels at diagnosis do not necessarily correspond to levels when the cancer started.<ref name="pmid18629310">{{cite journal | author = Verner MA, Charbonneau M, López-Carrillo L, Haddad S | title = Physiologically based pharmacokinetic modeling of persistent organic pollutants for lifetime exposure assessment: a new tool in breast cancer epidemiologic studies | journal = Environ. Health Perspect. | volume = 116 | issue = 7 | pages = 886–92 | date = July 2008 | pmid = 18629310 | pmc = 2453156 | doi = 10.1289/ehp.10917 }}</ref> Taken as a whole such studies "do not support the hypothesis that exposure to DDT is an important risk factor for breast cancer."<ref name=Cohn07/> The studies of this design have been extensively reviewed.<ref name="pmid16125595"/><ref>{{cite journal | author = Brody JG, Moysich KB, Humblet O, Attfield KR, Beehler GP, Rudel RA | title = Environmental pollutants and breast cancer: epidemiologic studies | journal = Cancer | volume = 109 | issue = 12 Suppl | pages = 2667–711 | date = June 2007 | pmid = 17503436 | doi = 10.1002/cncr.22655 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | author = López-Cervantes M, Torres-Sánchez L, Tobías A, López-Carrillo L | title = Dichlorodiphenyldichloroethane burden and breast cancer risk: a meta-analysis of the epidemiologic evidence | journal = Environ. Health Perspect. | volume = 112 | issue = 2 | pages = 207–14 | date = February 2004 | pmid = 14754575 | pmc = 1241830 | doi = 10.1289/ehp.6492 }}</ref> |

|||

In contrast, a study published in 2007 strongly associated early exposure (the ''p,p'-'' isomer) and breast cancer later in life. Unlike previous studies, this [[prospective cohort study]] collected blood samples from young mothers in the 1960s while DDT was still in use, and their breast cancer status was then monitored over the years. In addition to suggesting that the ''p,p'-'' isomer is the more significant risk factor, the study also suggests that the timing of exposure is critical. For the subset of women born more than 14 years before agricultural use, there was no association between DDT and breast cancer. However, for younger women – exposed earlier in life – the third who were exposed most to ''p,p'-''DDT had a fivefold increase in breast cancer incidence over the least exposed third, after correcting for the protective effect of ''o,p'-''DDT.<ref name=Cohn07/><ref>{{cite news | first = Douglas | last = Fischer |title=Exposure to DDT is linked to cancer |url=http://www.contracostatimes.com/health/ci_6524706?nclick_check=1 |publisher=Contra Costa Times |date=August 8, 2007 |archiveurl=http://www.webcitation.org/5uKxfh59f |archivedate=November 18, 2010|deadurl=no}}</ref><ref name=cone2007>{{cite news |

|||

| first = Marla | last = Cone |title=Study finds DDT, breast cancer link |url=http://articles.latimes.com/2007/sep/30/nation/na-ddt30 |newspaper=[[Los Angeles Times]] |date=September 30, 2007}}</ref> These results are supported by animal studies.<ref name="PineRiver"/> |

|||

==Use against malaria== |

|||

[[Malaria]] remains a major public health challenge in many countries. 2008 WHO estimates were 243 million cases, and 863,000 deaths. About 89% of these deaths occur in [[Africa]], and mostly to children under the age of 5.<ref name="wmr09">2009 WHO [http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2009/9789241563901_eng.pdf World Malaria Report 2009]</ref> DDT is one of many tools that public health officials use to fight the disease. Its use in this context has been called everything from a "miracle weapon [that is] like [[Kryptonite]] to the mosquitoes,"<ref name=salon/> to "toxic colonialism."<ref>{{cite journal | last = Paull | first = John |title=Toxic Colonialism |journal=New Scientist |issue=2628 |page=25 |date=November 3, 2007 |url=http://www.newscientist.com/article/mg19626280.400-toxic-colonialism.html/}}</ref> |

|||

Before DDT, eliminating mosquito breeding grounds by drainage or poisoning with [[Paris green]] or [[pyrethrum]] was sometimes successful in fighting malaria. In parts of the world with rising living standards, the elimination of malaria was often a collateral benefit of the introduction of window screens and improved sanitation.<ref name="Gladwell"/> Today, a variety of usually simultaneous interventions is the norm. These include [[antimalarial drugs]] to prevent or treat infection; improvements in public health infrastructure to quickly diagnose, sequester, and treat infected individuals; [[mosquito net|bednets]] and other methods intended to keep mosquitoes from biting humans; and [[vector control]] strategies<ref name=wmr09/> such as [[larvacide|larvaciding]] with insecticides, ecological controls such as draining mosquito breeding grounds or introducing fish to eat larvae, and [[indoor residual spraying]] (IRS) with insecticides, possibly including DDT. IRS involves the treatment of all interior walls and ceilings with insecticides, and is particularly effective against mosquitoes, since many species rest on an indoor wall before or after feeding. DDT is one of 12 WHO–approved IRS insecticides. How much of a role DDT should play in this mix of strategies is still controversial.<ref>Yakob, L., Dunning, R. & Yan, G. Indoor residual spray and insecticide-treated bednets for malaria control: theoretical synergisms and antagonisms. [http://rsif.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/early/2010/11/11/rsif.2010.0537.short?rss=1 JRS Interface] {{doi|10.1098/rsif.2010.0537}}</ref> |

|||

WHO's anti-malaria campaign of the 1950s and 1960s relied heavily on DDT and the results were promising, though temporary. Experts tie the resurgence of malaria to multiple factors, including poor leadership, management and funding of malaria control programs; poverty; civil unrest; and increased [[irrigation]]. The evolution of resistance to first-generation drugs (e.g. [[chloroquine]]) and to insecticides exacerbated the situation.<ref name="DDTBP.1/2"/><ref>{{cite journal | author = Feachem RG, Sabot OJ | title = Global malaria control in the 21st century: a historic but fleeting opportunity | journal = JAMA | volume = 297 | issue = 20 | pages = 2281–4 | year = 2007 | pmid = 17519417 | doi = 10.1001/jama.297.20.2281 }}</ref> Resistance was largely fueled by often unrestricted agricultural use. Resistance and the harm both to humans and the environment led many governments to restrict or curtail the use of DDT in vector control as well as agriculture.<ref name="pmid7278974"/> In 2006 the WHO reversed a longstanding policy against DDT by recommending that it be used as an indoor pesticide in regions where malaria is a major problem.<ref>{{cite news |url=http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2006/09/15/AR2006091501012.html |title=WHO Urges Use of DDT in Africa |date=September 16, 2006 |newspaper=Washington Post}}</ref> |

|||

Once the mainstay of anti-malaria campaigns, as of 2008 only 12 countries used DDT, including India and some southern African states,<ref name=wmr09/> though the number is expected to rise.<ref name="DDTBP.1/2"/> |

|||

===Initial effectiveness of DDT against malaria=== |

|||

When it was first introduced in World War II, DDT was very effective in reducing malaria [[morbidity]] and [[mortality rate|mortality]].<ref name=Dunlap/> The WHO's anti-malaria campaign, which consisted mostly of spraying DDT, was initially very successful as well. For example, in [[Sri Lanka]], the program reduced cases from about one million per year before spraying to just 18 in 1963<ref>{{cite book |title=The Coming Plague |publisher=Virago Press |year=1994 |isbn=1-86049-211-8 |page=51 | last = Garrett | first = Laurie }}</ref><ref>[http://www.nytimes.com/2010/12/28/health/28global.html Malaria: A Disease Close to Eradication Grows, Aided by Political Tumult in Sri Lanka], Donald G. McNeil Jr, ''The New York Times'', December 27, 2010.</ref> and 29 in 1964. Thereafter the program was halted to save money and malaria rebounded to 600,000 cases in 1968 and the first quarter of 1969. The country resumed DDT vector control but the mosquitoes had evolved resistance in the interim, presumably because of continued agricultural use. The program switched to [[malathion]], which though more expensive, proved effective.<ref name="Gordon">{{cite book|last=Harrison|first=Gordon A|title=Mosquitoes, Malaria, and Man: A History of the Hostilities Since 1880|publisher=Dutton|year=1978|isbn=978-0-525-16025-0}}</ref> |

|||

Today, DDT remains on the WHO's list of insecticides recommended for IRS. Since the appointment of [[Arata Kochi]] as head of its anti-malaria division, WHO's policy has shifted from recommending IRS only in areas of seasonal or episodic transmission of malaria, to also advocating it in areas of continuous, intense transmission.<ref> |

|||

[http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2006/pr50/en/index.html WHO |WHO gives indoor use of DDT a clean bill of health for controlling malaria]</ref> The WHO has reaffirmed its commitment to eventually phasing out DDT, aiming "to achieve a 30% cut in the application of DDT world-wide by 2014 and its total phase-out by the early 2020s if not sooner" while simultaneously combating malaria. The WHO plans to implement alternatives to DDT to achieve this goal.<ref>[http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2009/malaria_ddt_20090506/en/index.html Countries move toward more sustainable ways to roll back malaria]</ref> |

|||

South Africa is one country that continues to use DDT under WHO guidelines. In 1996, the country switched to alternative insecticides and malaria incidence increased dramatically. Returning to DDT and introducing new drugs brought malaria back under control.<ref>{{cite journal | author = Yamey G | title = Roll Back Malaria: a failing global health campaign | journal = BMJ | volume = 328 | issue = 7448 | pages = 1086–1087 | date = May 8, 2004 | pmid = 15130956 | pmc = 406307 | doi = 10.1136/bmj.328.7448.1086 }}</ref> According to DDT advocate Donald Roberts, malaria cases increased in [[South America]] after countries in that continent stopped using DDT. Research data shows a significantly strong negative relationship between DDT residual house sprayings and malaria rates. In a research from 1993 to 1995, Ecuador increased its use of DDT and resulted in a 61% reduction in malaria rates, while each of the other countries that gradually decreased its DDT use had large increase in malaria rates.<ref name="Roberts 1997"/> |

|||

===Mosquito resistance=== |

|||

Resistance has greatly reduced DDT's effectiveness. WHO guidelines require that absence of resistance must be confirmed before using the chemical.<ref name="IRS-WHO"> |

|||

[http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2006/WHO_HTM_MAL_2006.1112_eng.pdf Indoor Residual Spraying: Use of Indoor Residual Spraying for Scaling Up Global Malaria Control and Elimination.] World Health Organization, 2006.</ref> Resistance is largely due to agricultural use, in much greater quantities than required for disease prevention. According to one study that attempted to quantify the lives saved by banning agricultural use and thereby slowing the spread of resistance, "it can be estimated that at current rates each kilo of insecticide added to the environment will generate 105 new cases of malaria."<ref name="pmid7278974"/> |

|||

Resistance was noted early in spray campaigns. Paul Russell, a former head of the [[Allies of World War II|Allied]] Anti-Malaria campaign, observed in 1956 that "resistance has appeared after six or seven years."<ref name="Gladwell"/> DDT has lost much of its effectiveness in Sri Lanka, [[Pakistan]], [[Turkey]] and [[Central America]], and it has largely been replaced by [[organophosphate]] or [[carbamate]] insecticides, ''e.g.'' malathion or [[bendiocarb]].<ref name="Curtis">C.F. Curtis, [http://ipmworld.umn.edu/chapters/curtiscf.htm Control of Malaria Vectors in Africa and Asia]</ref> |

|||

In many parts of [[India]], DDT has also largely lost its effectiveness.<ref>{{cite journal | author = Sharma VP | title = Current scenario of malaria in India | journal = Parassitologia | volume = 41 | issue = 1–3 | pages = 349–53 | year = 1999 | pmid = 10697882 }}</ref> Agricultural uses were banned in 1989 and its anti-malarial use has been declining. Urban use has halted completely.<ref>{{cite journal |title=No Future in DDT: A case study of India |last=Agarwal |first=Ravi |journal=Pesticide Safety News |date=May 2001}}</ref> Nevertheless, DDT is still manufactured and used,<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.unce.unr.edu/publications/files/nr/2003/SP0316.pdf |title=DDT and DDE: Sources of Exposure and How to Avoid Them| first1 = Art | last1 = Fisher | first2 = Mark | last2 = Walker | first3 = Pam | last3 = Powell |format=PDF |accessdate=December 2, 2010}}</ref> and one study had concluded that "DDT is still a viable insecticide in indoor residual spraying owing to its effectivity in well supervised spray operation and high excito-repellency factor."<ref name="mrc">{{cite journal | author = Sharma SN, Shukla RP, Raghavendra K, Subbarao SK | title = Impact of DDT spraying on malaria transmission in Bareilly District, Uttar Pradesh, India | journal = J Vector Borne Dis | volume = 42 | issue = 2 | pages = 54–60 | date = June 2005 | pmid = 16161701 }}</ref> |

|||

Studies of malaria-vector mosquitoes in [[KwaZulu-Natal Province]], [[South Africa]] found susceptibility to 4% DDT (the WHO susceptibility standard), in 63% of the samples, compared to the average of 86.5% in the same species caught in the open. The authors concluded that "Finding DDT resistance in the vector ''An. arabiensis'', close to the area where we previously reported pyrethroid-resistance in the vector ''An. funestus'' Giles, indicates an urgent need to develop a strategy of insecticide resistance management for the malaria control programmes of southern Africa."<ref name="Hargreaves">{{cite journal | author = Hargreaves K, Hunt RH, Brooke BD, Mthembu J, Weeto MM, Awolola TS, Coetzee M | title = Anopheles arabiensis and An. quadriannulatus resistance to DDT in South Africa | journal = Med. Vet. Entomol. | volume = 17 | issue = 4 | pages = 417–22 | year = 2003 | pmid = 14651656 | doi = 10.1111/j.1365-2915.2003.00460.x }}</ref> |

|||

DDT can still be effective against resistant mosquitoes,<ref name=PLoS1/> and the avoidance of DDT-sprayed walls by mosquitoes is an additional benefit of the chemical.<ref name="mrc"/> For example, a 2007 study reported that resistant mosquitoes avoided treated huts. The researchers argued that DDT was the best pesticide for use in IRS (even though it did not afford the most protection from mosquitoes out of the three test chemicals) because the others pesticides worked primarily by killing or irritating mosquitoes – encouraging the development of resistance to these agents.<ref name="PLoS1">{{cite journal | author = Grieco JP, Achee NL, Chareonviriyaphap T, Suwonkerd W, Chauhan K, Sardelis MR, Roberts DR | title = A new classification system for the actions of IRS chemicals traditionally used for malaria control | journal = PLoS ONE | volume = 2 | issue = 1 | pages = e716 | year = 2007 | pmid = 17684562 | pmc = 1934935 | doi = 10.1371/journal.pone.0000716 | editor1-last = Krishna | editor1-first = Sanjeev }}</ref> Others argue that the avoidance behavior slows the eradication of the disease.<ref name="Musawenkosi"/> Unlike other insecticides such as pyrethroids, DDT requires long exposure to accumulate a lethal dose; however its irritant property shortens contact periods. "For these reasons, when comparisons have been made, better malaria control has generally been achieved with pyrethroids than with DDT."<ref name="Curtis"/> In India, with its outdoor sleeping habits and frequent night duties, "the excito-repellent effect of DDT, often reported useful in other countries, actually promotes outdoor transmission."<ref>{{cite journal |title=DDT: The fallen angel | first=V. P. |last=Sharma |journal=Current Science |volume=85 |pages=1532–7 |issue=11 |date=December 2003 |url=http://www.ias.ac.in/currsci/dec102003/1532.pdf |format=PDF}}</ref> Genomic studies in the model genetic organism ''Drosophila melanogaster'' have revealed that high level DDT resistance is polygenic, involving multiple resistance mechanisms.<ref>{{cite journal | author = Pedra JH, McIntyre LM, Scharf ME, Pittendrigh BR | title = Genome-wide transcription profile of field- and laboratory-selected dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT)-resistant Drosophila | journal = Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. | volume = 101 | issue = 18 | pages = 7034–9 | date = May 2004 | pmid = 15118106 | pmc = 406461 | doi = 10.1073/pnas.0400580101 | url = http://www.pnas.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=15118106 }}</ref> |

|||

===Residents' concerns=== |

|||

{{main|Indoor residual spraying#Residents's opposition to IRS}} |

|||

For IRS to be effective, at least 80% of homes and barns in an area must be sprayed.<ref name="IRS-WHO"/> Lower coverage rates can jeopardize program effectiveness. Many residents resist DDT spraying, objecting to the lingering smell, stains on walls, and may exacerbate problems with other insect pests.<ref name="Curtis"/><ref name="Musawenkosi">{{cite journal | author = Mabaso ML, Sharp B, Lengeler C | title = Historical review of malarial control in southern African with emphasis on the use of indoor residual house-spraying | journal = Trop. Med. Int. Health | volume = 9 | issue = 8 | pages = 846–56 | year = 2004 | pmid = 15303988 | doi = 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2004.01263.x }}</ref><ref name="Thurow">[http://www.mindfully.org/Health/Malaria-New-Strain.htm In Malaria War, South Africa Turns To Pesticide Long Banned in the West], Roger Thurow, [[Wall Street Journal]], July 26, 2001</ref> [[Pyrethroid]] insecticides (e.g. [[deltamethrin]] and [[lambda-cyhalothrin]]) can overcome some of these issues, increasing participation.<ref name="Curtis"/> |

|||

===Human exposure=== |

|||