Sudanese civil war (2023–present): Difference between revisions

expanded, see talk Tag: Reverted |

FuzzyMagma (talk | contribs) Undid revision 1153718566 by Tobby72 (talk) what talk page are you talking about? last consensus is not to include the word allegation or refuted, see Talk:2023 Sudan conflict#Wagner... and Talk:2023 Sudan conflict/Archive 1#Sock puppets - Extended confirmed protection |

||

| Line 30: | Line 30: | ||

*[[Humanitarian crisis of the 2023 Sudan conflict|Humanitarian crisis]] |

*[[Humanitarian crisis of the 2023 Sudan conflict|Humanitarian crisis]] |

||

| combatants_header = |

| combatants_header = |

||

| combatant1 = {{flagicon image|Emblem of the Rapid Support Forces.png|border=}} [[Rapid Support Forces]]<br/>'''Supported by:'''<br/>{{flagicon image|Flag_of_The_Libyan_National_Army_(Variant).svg}} [[Libyan National Army]]{{efn|alleged, but denied by [[Khalifa Haftar]]<ref name=for1>{{cite news |last1=Faucon |first1=Benoit |last2=Said |first2=Summer |last3=Malsin |first3=Jared |title=Libyan Militia and Egypt's Military Back Opposite Sides in Sudan Conflict |url=https://www.wsj.com/articles/libyan-militia-and-egypts-military-back-opposite-sides-in-sudan-conflict-87206c3b |access-date=19 April 2023 |work=The Wall Street Journal |date=19 April 2023 |quote="Mr. Haftar, who is backed by Russia and the United Arab Emirates, sent at least one shipment of ammunition on Monday (17 April) from Libya to Sudan to replenish supplies for Gen. Dagalo," the people familiar with the matter said.|archive-date=19 April 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230419190701/https://www.wsj.com/articles/libyan-militia-and-egypts-military-back-opposite-sides-in-sudan-conflict-87206c3b |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="libya-ahram"/>}}<br/> {{ |

| combatant1 = {{flagicon image|Emblem of the Rapid Support Forces.png|border=}} [[Rapid Support Forces]]<br/>'''Supported by:'''<br/>{{flagicon image|Flag_of_The_Libyan_National_Army_(Variant).svg}} [[Libyan National Army]]{{efn|alleged, but denied by [[Khalifa Haftar]]<ref name=for1>{{cite news |last1=Faucon |first1=Benoit |last2=Said |first2=Summer |last3=Malsin |first3=Jared |title=Libyan Militia and Egypt's Military Back Opposite Sides in Sudan Conflict |url=https://www.wsj.com/articles/libyan-militia-and-egypts-military-back-opposite-sides-in-sudan-conflict-87206c3b |access-date=19 April 2023 |work=The Wall Street Journal |date=19 April 2023 |quote="Mr. Haftar, who is backed by Russia and the United Arab Emirates, sent at least one shipment of ammunition on Monday (17 April) from Libya to Sudan to replenish supplies for Gen. Dagalo," the people familiar with the matter said.|archive-date=19 April 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230419190701/https://www.wsj.com/articles/libyan-militia-and-egypts-military-back-opposite-sides-in-sudan-conflict-87206c3b |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="libya-ahram"/>}}<br/> {{RUS}} ([[Wagner Group]])<ref>{{Cite web |title=Exclusive: Evidence emerges of Russia's Wagner arming militia leader battling Sudan's army |url=https://www.cnn.com/2023/04/20/africa/wagner-sudan-russia-libya-intl/index.html |access-date=2023-05-06 |website=CNN |language=en |archive-date=6 May 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230506135638/https://www.cnn.com/2023/04/20/africa/wagner-sudan-russia-libya-intl/index.html |url-status=live }}</ref> |

||

| combatant2 = <!-- DO NOT ADD EGYPT UNDER "SUPPORTED BY:" TITLE. EGYPT IS A DIRECT BELLIGERENT. -->{{flagicon image|Insignia of the Sudanese Armed Forces.svg|border=}} [[Sudanese Armed Forces]]<br/>'''Supported by:'''<br/>{{flag|Egypt}}{{efn|alleged, but denied by Egypt<ref>{{cite news |last1=Faucon |first1=Benoit |last2=Said |first2=Summer |last3=Malsin |first3=Jared |title=Libyan Militia and Egypt’s Military Back Opposite Sides in Sudan Conflict |url=https://www.wsj.com/articles/libyan-militia-and-egypts-military-back-opposite-sides-in-sudan-conflict-87206c3b |access-date=27 April 2023 |publisher=The Wall Street Journal |date=19 April 2023 |quote=Egypt...sent jet fighters just before the fighting started and additional pilots soon after to support Gen. Burhan |archive-date=19 April 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230419190701/https://www.wsj.com/articles/libyan-militia-and-egypts-military-back-opposite-sides-in-sudan-conflict-87206c3b |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name=egy1/><ref name=egy2/>}} |

| combatant2 = <!-- DO NOT ADD EGYPT UNDER "SUPPORTED BY:" TITLE. EGYPT IS A DIRECT BELLIGERENT. -->{{flagicon image|Insignia of the Sudanese Armed Forces.svg|border=}} [[Sudanese Armed Forces]]<br/>'''Supported by:'''<br/>{{flag|Egypt}}{{efn|alleged, but denied by Egypt<ref>{{cite news |last1=Faucon |first1=Benoit |last2=Said |first2=Summer |last3=Malsin |first3=Jared |title=Libyan Militia and Egypt’s Military Back Opposite Sides in Sudan Conflict |url=https://www.wsj.com/articles/libyan-militia-and-egypts-military-back-opposite-sides-in-sudan-conflict-87206c3b |access-date=27 April 2023 |publisher=The Wall Street Journal |date=19 April 2023 |quote=Egypt...sent jet fighters just before the fighting started and additional pilots soon after to support Gen. Burhan |archive-date=19 April 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230419190701/https://www.wsj.com/articles/libyan-militia-and-egypts-military-back-opposite-sides-in-sudan-conflict-87206c3b |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name=egy1/><ref name=egy2/>}} |

||

| combatant3 = |

| combatant3 = |

||

Revision as of 23:02, 7 May 2023

This article documents a current armed conflict. Information may change rapidly as the event progresses, and initial news reports may be unreliable. The latest updates to this article may not reflect the most current information. (April 2023) |

| 2023 Sudan conflict | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

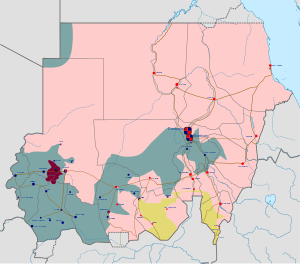

Military situation as of 14 August 2024 Controlled by the Sudanese Armed Forces

Controlled by the Rapid Support Forces

(For a more detailed map of the current military situation, see here) | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

Supported by: |

Supported by: | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| 70,000–150,000[9] | 110,000–120,000[9] | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| Unknown | 200 Egyptian servicemen captured | ||||||||

| At least 559 killed[10] and 4,000 injured[11] | |||||||||

An armed conflict between rival factions of the military government of Sudan began on 15 April 2023. It started when clashes broke out in western Sudan, in the capital city of Khartoum, and in the Darfur region. As of 25 April, at least 559 people have been killed[10] and more than 4,000 others had been injured.[11]

The fighting began with attacks by the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) on key government sites. Airstrikes, artillery, and gunfire were reported across Sudan including in Khartoum. As of 23 April 2023[update], both the RSF leader Mohamed Hamdan "Hemedti" Dagalo and Sudan's de facto leader and army chief Abdel Fattah al-Burhan claimed control of several key government sites, including the general military headquarters, the Presidential Palace, Khartoum International Airport, Burhan's official residence, and the SNBC headquarters.[12][13][14][15] The conflict between the two generals has led Sudan to the brink of renewed civil war,[16] and it has been referred to as a "burgeoning civil war".[17]

Background

The history of conflicts in Sudan has consisted of foreign invasions and resistance, ethnic tensions, religious disputes, and competition over resources.[18][19] In its modern history, two civil wars between the central government and the southern regions killed 1.5 million people, and a continuing conflict in the western region of Darfur has displaced two million people and killed more than 200,000 people.[20] Since independence in 1956, Sudan has had more than fifteen military coups[21] and it has also been ruled by the military for the majority of the republic's existence, with only brief periods of democratic civilian parliamentary rule.[22]

Political context

Former president and military strongman Omar al-Bashir presided over the War in Darfur, a region in the west of the country, and oversaw state-sponsored violence in the region of Darfur, leading to charges of war crimes and genocide.[23] Approximately 300,000 people were killed and 2.7 million forcibly displaced in the early part of the Darfur conflict; the intensity of the violence later declined.[24] Key figures in the Darfur conflict included Hemedti, a warlord[17] who commanded the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) which evolved from the janjaweed, a collection of Arab militias drawn from camel-trading tribes active in Darfur and portions of Chad.[25]

Al-Bashir relied upon the janjaweed and RSF to crush uprisings by ethnic Africans in the Nuba Mountains and Darfur.[25][26] The RSF perpetrated mass killings, mass rapes, pillage, torture, and destruction of villages and were accused of committing ethnic cleansing against the Fur, Masalit, and Zaghawa.[26] Key leaders in the RSF have been indicted by the International Criminal Court (ICC) of genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity,[27] although Hemedti was not personally implicated in the 2003–2004 atrocities.[24] Bashir formalized the militias in 2013, creating the RSF as a paramilitary organization and giving its commanders formal military ranks;[17] Hemedti was given the rank of lieutenant general.[28] In 2017, a new Sudanese law gave the RSF the status of an "independent security force".[26] Under the patronage of al-Bashir, Hemedti became wealthy and powerful, acquiring gold mines in Darfur.[27][28] Bashir sent RSF forces to quash a 2013 uprising in South Darfur and also deployed RSF units to fight in Yemen and Libya.[17] During this time, the RSF also developed a working relationship with the Russian private military outfit Wagner Group.[29] These developments ensured that RSF forces grew into the tens of thousands, including thousands of armed pickup trucks, which regularly patrolled the streets of Khartoum.[29] The Bashir regime allowed the RSF and other armed groups to proliferate to prevent threats to its security from within the armed forces, a practice known as "coup-proofing".[30]

In December 2018, protests against al-Bashir's regime began, the first phase of the Sudanese Revolution. Eight months of sustained civil disobedience were met with violent repression.[31] In April 2019, the military (including the RSF) ousted al-Bashir in a coup d'état, ending his three decades of rule; the army established a Transitional Military Council, a junta.[31][27][28] Bashir was imprisoned in Khartoum; he was not turned over to the ICC, which had issued warrants for al-Bashir's arrest on charges of war crimes.[32] Protests calling for civilian rule continued; in June 2019, the RSF perpetrated the Khartoum massacre, in which more than a hundred demonstrators were slain[31][28][17] and dozens were raped.[17] Hemedti denied orchestrating the attack.[28]

In August 2019, after international pressure and mediation by the African Union and Ethiopia, the military agreed to share power in an interim joint civilian-military unity government (the Transitional Sovereignty Council), headed by a civilian Prime Minister, Abdalla Hamdok, with elections to take place in 2023.[23][31] However, in October 2021, the military seized power in a coup led by Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) leader Abdel Fattah al-Burhan and RSF leader Dagalo. The Transitional Sovereignty Council was reconstituted as a military junta led by Al-Burhan, monopolizing power[33] and halting Sudan's brief transition to democracy.[32]

Tensions between the RSF and the Sudanese junta began to escalate in February 2023, as the RSF began to recruit members from across Sudan. A brief military buildup in Khartoum was succeeded by an agreement for de-escalation, with the RSF withdrawing its forces from the Khartoum area.[34] The junta later agreed to hand over authority to a civilian-led government,[35] but it was delayed due to renewed tensions between generals Burhan and Dagalo, who serve as chairman and deputy chairman of the Transitional Sovereignty Council, respectively.[32][36] Chief among their political disputes is the integration of the RSF into the military:[32][37] the RSF insisted on a ten-year timetable for its integration into the regular army, while the army demanded integration within two years.[12] Other contested issues included the status given to RSF officers in the future hierarchy, and whether RSF forces should be under the command of the army chief – rather than Sudan's commander-in-chief – who is currently al-Burhan.[38] They have also clashed over authority over sectors of Sudan's economy that are controlled by the two factions. As a sign of their rift, Dagalo expressed regret over the October 2021 coup.[33]

Prelude

On 11 April 2023, RSF forces deployed near the city of Merowe and in Khartoum.[39] Government forces ordered them to leave, but they refused. This led to clashes when RSF forces took control of the Soba military base south of Khartoum.[39] On 13 April, RSF forces began their mobilization, raising fears of a potential rebellion against the junta. The SAF declared the mobilization illegal.[40]

Timeline

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (May 2023) |

Casualties

As of 25 April, at least 559 people had been killed[10] and more than 4,000 others had been injured,[11] according to the World Health Organization (WHO) and Sudan's Federal Health Ministry. The Sudan Doctors Syndicate said at least 436 civilians had been killed and 2,175 others injured.[41] The United Nations Children's Fund said that at least nine children had been killed and 50 others had been injured in the fighting.[42] On 6 May, Save the Children UK said that at least 190 children had been killed in the conflict.[43] Doctors on the ground warned that stated figures do not include all casualties as many people could not reach hospitals due to difficulties in movement.[44] A spokesperson for the Sudanese Red Crescent was also quoted as saying that the number of casualties "was not small".[45]

By location

During initial clashes in El-Obeid and Khartoum at least three civilians were killed and dozens injured.[46] A statement by the Sudan Doctors' Committee said two civilians were killed at Khartoum airport and another man was shot to death in the state of North Kordofan.[30] Those killed at the airport were believed to be on board a passenger plane that was hit by a shell.[47] Many bodies were seen lying on the streets of Khartoum, particularly around the defence ministry and airport, but could not be retrieved given the intensity of the fighting.[48][49] A student was shot and killed at the University of Khartoum.[50] A 6-year-old child died after the RSF shelled a hospital[51] while an ambulance driver was reported to be among those injured.[52] Asia Abdelmajid, one of Sudan’s most prominent actresses, was killed in a crossfire in Khartoum Bahri.[53]

At least twenty five civilians were killed and 26 injured during clashes in North Darfur, and an additional three civilians were killed by a rocket-propelled grenade, with a woman also being injured by a bullet.[54] A representative of Médecins Sans Frontières said at least 279 wounded people were admitted to the only functioning hospital in the state capital al-Fashir, of whom 44 died.[55] In Foro Baranga in West Darfur, tens were reportedly killed and hundreds injured.[56] In Nyala, in South Darfur, 8 civilians were killed during the ongoing clashes.[57] Nearly 200 people died in ethnic clashes in Geneina, West Darfur.[58]

Foreign casualties

According to a Syrian diplomat, fifteen Syrian citizens had been killed in Sudan.[59] An Indian national working in Khartoum died after being hit by a stray bullet on 15 April.[60] Two Americans were also killed, including a professor working in the University of Khartoum who was stabbed to death while evacuating.[61][62] A two-year-old girl from Turkey was killed while her parents were injured after their house was struck by a rocket on 18 April.[63] The SAF claimed that the Egyptian assistant military attaché was killed by RSF fire while driving his car in Khartoum, which was refuted by the Egyptian ambassador.[64]

Two Greek nationals who were trapped in a church on 15 April suffered leg injuries in a crossfire when they tried to leave.[65][66] A Filipino migrant worker[67] and an Indonesian student at a school in Khartoum were injured by stray bullets.[68] On 17 April, the European Union Ambassador to Sudan, Aidan O'Hara of Ireland, was assaulted by unidentified "armed men wearing military fatigues" in his home and suffered minor injuries but was able to resume working on 19 April.[69][49] On 23 April, a French evacuation convoy was shot at, leaving one injured.[70] The French government later confirmed the casualty to be one of its soldiers.[71] An employee of the Egyptian embassy was shot and injured during an evacuation mission.[72][73]

Casualties among humanitarian workers

In Kabkabiya, three employees of the World Food Programme (WFP) were killed after being caught in the crossfire at a military base. Two other staff members were seriously injured.[46] On 18 April, the EU's top humanitarian aid officer in Sudan, Wim Fransen of Belgium, was shot in Khartoum and suffered serious injuries.[74] On 21 April, the International Organization for Migration (IOM) reported that one of its local employees was killed in a crossfire while travelling with his family near El-Obeid.[75]

Foreign involvement

Libya

On 18 April, a SAF general claimed that two unnamed neighboring countries were trying to provide aid to the RSF.[76] According to The Wall Street Journal, Libyan warlord Khalifa Haftar, who is backed by the United Arab Emirates and the Russian paramilitary Wagner Group, dispatched at least one plane to fly military supplies to the RSF.[1][when?] The Observer reported that Haftar assisted in preparing the RSF for months before the conflict broke out.[77] The Libyan National Army, which is commanded by Haftar, denied providing support to any warring groups in Sudan and said it was ready to play a mediating role.[78]

Wagner Group

Prior to the conflict, the UAE and the Wagner Group have been involved in business deals with the RSF.[79][80] According to CNN, Wagner supplied surface-to-air missiles to the RSF, picking up the items from Syria and delivering some of them by plane to Haftar-controlled bases in Libya to be then delivered to the RSF, while dropping other items directly to RSF positions in northwestern Sudan.[81] American officials also said that Wagner was offering to supply additional weapons to RSF from its existing stocks in the Central African Republic.[82] Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov defended the possible involvement of the Wagner Group, saying that Sudan had the right to use its services.[83] The head of the Wagner Group, Yevgeny Prigozhin, denied supporting the RSF, saying that the company has not had a presence in Sudan for more than two years.[84] In addition, the RSF denied allegations that Wagner Group was supporting them, instead stating that the SAF was seeking such support.[85] Sudan's army chief, Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, stated that "So far, there has been no confirmation about the Wagner Group's support for the RSF."[2] The RSF has consistently denied the presence of Wagner on its territory.[86][87]

Egypt

On 16 April, the RSF claimed that its troops in Port Sudan had been attacked by foreign aircraft and issued a warning against any foreign interference.[5] According to former CIA analyst Cameron Hudson, Egyptian fighter jets are a part of these bombing campaigns against the RSF, and Egyptian special forces units have been deployed and are providing intelligence and tactical support to SAF.[6] The Wall Street Journal said that Egypt had sent fighter jets and pilots to support the Sudanese military.[1] On 17 April, satellite imagery obtained by The War Zone revealed that one Egyptian Air Force MiG-29M2 fighter jet had been destroyed and two others had been heavily damaged or destroyed at Merowe Airbase. A Sudanese Air Force Guizhou JL-9 was among the destroyed aircraft.[88] After initial confusion, the RSF accepted the explanation that Egyptian equipment and supporting personnel were conducting exercises with the Sudanese military prior to the outbreak of hostilities.[12]

Egyptian POWs

On 15 April, RSF forces claimed, via Twitter, to have taken several Egyptian troops prisoner near Merowe,[89][90] as well as a military plane carrying markings of the Egyptian Air Force.[91] Initially, no official explanation was given for the Egyptian soldiers' presence, while Egypt and Sudan have had military cooperation due to diplomatic tensions with Ethiopia.[92] Later on, the Egyptian Armed Forces stated that around 200 of its soldiers were in Sudan to conduct exercises with the Sudanese military.[12] Around that time, the SAF reportedly encircled RSF forces in Merowe airbase. As a result, the Egyptian Armed Forces announced that it was following the situation as a precaution for the safety of its personnel.[45][93] The RSF later stated that it would cooperate in repatriating the soldiers to Egypt.[91] On 19 April, the RSF stated that it had moved the soldiers to Khartoum and would hand them over when the "appropriate opportunity" arose.[94] 177 of the captured Egyptian troops were released and flown back to Egypt aboard three Egyptian military planes that took off from Khartoum airport later in the day. The remaining 27 soldiers, who were from the Egyptian Air Force, were sheltered at the Egyptian embassy to be evacuated once the situation improved.[95][96]

Ethiopia

On 19 April, the Sudanese newspaper Al-Sudani reported that the SAF had repelled an invasion by the Ethiopian Armed Forces in the disputed Al Fushqa District. The report alleged that the Ethiopian Army had carried out an attack with tanks, armored vehicles, and infantry and that the SAF had inflicted heavy losses on Ethiopian personnel and equipment. It said that the SAF was monitoring "unusual activity among the Ethiopian forces" since the start of hostilities with the RSF and that Ethiopian forces were carrying out intensive reconnaissance and surveillance operations along the border.[97] Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed denied that clashes had occurred, blaming agitators for the reports.[98][99]

Evacuation of foreign nationals

The outbreak of violence has led foreign governments to monitor the situation in Sudan and move towards the evacuation and repatriation of its nationals. Among some countries with a number of expatriates in Sudan are Egypt, which has more than 10,000 citizens in the country,[100] and the United States, which has more than 16,000 citizens, most of whom are dual nationals.[101] Efforts at extraction were hampered by the fighting within the capital Khartoum, particularly in and around the airport. This has forced evacuations to be undertaken by road via Port Sudan on the Red Sea, which lies about 650 km (400 miles) northeast of Khartoum.[102] from where they were airlifted or ferried directly to their home countries or to third ones. Other evacuations were undertaken through overland border crossings or airlifts from diplomatic missions and other designated locations with direct involvement of the militaries of some home countries. Some major transit hubs used during the evacuation include the port of Jeddah in Saudi Arabia and Djibouti, which hosts military bases of the United States, China, Japan, France, and other European countries.[103]

Humanitarian impact

The humanitarian crisis following the fighting was further exacerbated by the violence occurring during a period of high temperatures, drought and it being the latter part of the fasting month of Ramadan. Most residents were unable to venture outside of their homes to obtain food and supplies for fear of getting caught in the crossfire. A doctors' group said that hospitals remained understaffed and were running low on supplies as wounded people streamed in.[104] The World Health Organization recorded around 26 attacks on healthcare facilities, some of which resulted in casualties among medical workers and civilians.[105] The Sudanese Doctors' Union said more than two-thirds of hospitals in conflict areas were out of service with 32 forcibly evacuated by soldiers or caught in the crossfire.[106] The United Nations reported that shortages of basic goods, such as food, water, medicines and fuel have become "extremely acute".[107] The delivery of badly-needed remittances from overseas migrant workers was also halted after Western Union announced it was closing all operations in Sudan until further notice.[108] The World Food Programme said that more than $13 million worth of food aid destined for Sudan had been looted since the fighting broke out.[109]

Refugees

The United Nations said on 2 May that the fighting in Sudan had produced around 334,000 internally displaced persons, while more than 100,000 had fled the country altogether.[105] The International Organization for Migration estimated that around 70% of IDPs came from the Darfur region.[110] The UN projected that the total number of refugees fleeing Sudan could reach more than 800,000 people.[111]

Peace efforts

On 16 April, representatives from the SAF and the RSF agreed to a proposal by the United Nations to pause fighting between 16:00 and 19:00 local time (CAT).[112] The SAF announced that it approved a UN proposal to open a safe passage for urgent humanitarian cases for three hours every day starting from 16:00 local time, and stated that it reserved the right to react if the RSF "commit[ted] any violations".[113] Gunfire and explosives continued to be heard during the ceasefire, drawing condemnation from Special Representative Volker Perthes.[114]

On 17 April, the governments of Kenya, South Sudan, and Djibouti expressed their willingness to send their presidents to Sudan to act as mediators. Khartoum Airport was closed due to fighting, making arrival by air difficult.[115]

On 18 April, RSF commander Dagalo said the paramilitary force agreed to a day-long armistice to allow the safe passage of civilians, including those wounded. In a tweet, he said that the decision was reached following a conversation with US Secretary of State Antony Blinken "and outreach by other friendly nations".[116] The SAF initially said it was unaware of any coordination with mediators or the international community regarding a truce and claimed the RSF was planning to use this time to cover up for a "crushing defeat".[117] An army general later confirmed that the SAF had agreed to a 24-hour ceasefire to start at 18:00 local time (16:00 UTC). After the start of the promised ceasefire, gunfire and shelling continued to be heard in the center of Khartoum.[118] The SAF and the RSF issued statements accusing each other of failing to respect the ceasefire. The SAF's high command said it would continue operations to secure the capital and other regions.[119]

On 19 April, both the SAF and the RSF said that they had agreed to another 24-hour ceasefire starting at 18:00 local time (16:00 GMT).[120] Heavy fighting continued between the two sides after the ceasefire had supposedly begun.[121]

On 21 April, the RSF said it would observe a 72-hour ceasefire which would come into effect at 6:00 (4:00 GMT) that day, the beginning of the Islamic holiday of Eid ul-Fitr. There was no immediate word from the SAF on whether it would reciprocate.[122] Despite the SAF agreeing to a three-day truce later that afternoon, fighting continued throughout the day in Khartoum and other conflict zones.[123][124] A new 72-hour ceasefire agreement was announced on 24 April,[125] but fighting continued again.[126]

On 26 April, the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) proposed a 72-hour extension of the ceasefire, while South Sudan offered to host mediation efforts. The SAF said it supported the plan and would send an envoy to the South Sudanese capital Juba, to participate in the talks.[127] The RSF announced its support for the extended ceasefire on 27 April.[128] Fighting continued after the start of the extended ceasefire.[129]

On 30 April, the RSF announced that the ceasefire was to be further extended by 72 hours,[130] to which the SAF later agreed.[131] Fighting continued during this ceasefire.[132]

On 1 May, United Nations Special Envoy to Sudan Volker Perthes announced that the SAF and the RSF had agreed to send representatives for negotiations mediated by the UN, but did not give a date or venue for the talks.[133]

On 2 May, South Sudan's Foreign Ministry said that the SAF and the RSF had agreed "in principle" to a weeklong ceasefire to start from 4 May,[134] only for it to break down again.[135] The Sudanese resistance committees stated that the proposed negotiations between the SAF and the RSF ignored "the only one affected by this war, the Sudanese people", and that the negotiations were aimed at the SAF and RSF "gain[ing] popular and political support".[136]

On 6 May, delegates from the SAF and the RSF met directly for the first time in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia for what was described by the Saudis and the United States as "pre-negotiation talks".[137][138] Jonathan Hutson of the Satellite Sentinel Project stated that a broad range of Sudanese civil society, "political parties, resistance committees, women's organisations, trade unions and human rights defenders", objected to both Burhan and Hemedti, seeing them as illegitimate leaders and insisted on participating in peace negotiations. The civil society activists called for paramilitary forces to be merged into the SAF under civilian authority.[136]

Disinformation

On 14 April, the official SAF page published a video it said was of operations carried out by the Sudanese Air Force against the RSF. Al Jazeera's monitoring and verification unit claimed the video was fabricated using footage from the video game Arma 3 that was published on TikTok in March 2023. The unit also claimed the video showing Sudanese army commander Abdel Fattah al-Burhan inspecting the Armoured Corps was from before the fighting. A video reportedly of Sudanese helicopters flying over Khartoum to participate in operations by the SAF against the RSF, which also circulated on social media, turned out to be from November 2022.[139]

Two photos widely circulated on social media that depicted a burning bridge reported as Bahri bridge and a bombed building allegedly in Khartoum, were both revealed to be from the Russian invasion of Ukraine.[140]

In April, a video supposedly showing the RSF in control of the Khartoum International Airport on 15 April circulated on social media. The fact-checking website Lead Stories found that the video appeared online three months prior to the conflict.[141]

Reactions

Domestic

Military

![]() Rapid Support Forces: In an interview with Al Jazeera, Hemedti, commander of the RSF, accused Abdel Fattah al-Burhan of forcing the RSF to begin confrontations and accused SAF commanders of scheming to bring deposed leader Omar al-Bashir back to power.[45] On Twitter, Dagalo called for the international community to intervene against Burhan, claiming that the RSF was fighting against radical militants.[142]

Rapid Support Forces: In an interview with Al Jazeera, Hemedti, commander of the RSF, accused Abdel Fattah al-Burhan of forcing the RSF to begin confrontations and accused SAF commanders of scheming to bring deposed leader Omar al-Bashir back to power.[45] On Twitter, Dagalo called for the international community to intervene against Burhan, claiming that the RSF was fighting against radical militants.[142]

![]() Sudanese Armed Forces: The SAF accused the RSF of seditious conspiracy against the state and said that the RSF would be dissolved without discussion. It labeled Dagalo a criminal and issued a wanted notice for him. The SAF stated it would conduct sweeps for Rapid Support Forces and urged civilians to stay inside. The Sudanese Armed Forces' media representative told Al Jazeera that retired veterans had joined the SAF's fight against the RSF.

Sudanese Armed Forces: The SAF accused the RSF of seditious conspiracy against the state and said that the RSF would be dissolved without discussion. It labeled Dagalo a criminal and issued a wanted notice for him. The SAF stated it would conduct sweeps for Rapid Support Forces and urged civilians to stay inside. The Sudanese Armed Forces' media representative told Al Jazeera that retired veterans had joined the SAF's fight against the RSF.

Civilian

Former Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok publicly appealed to both al-Burhan and Dagalo to cease fighting.[143]

On 18 April, el-Wasig el-Bereir of the National Umma Party was in communication with the SAF and the RSF to get them to stop fighting immediately,[144] while el-Fateh Hussein of the Khartoum resistance committees called for the fighting to stop immediately, stating that the resistance committees had long called for the SAF to "return to their barracks" and for the RSF to be dissolved.[144]

Sudanese resistance committees coordinated medical support networks, sprayed anti-war messages on walls, and encouraged local communities to avoid siding with either the RSF or the SAF. Hamid Murtada, a member of the resistance committees, described the resistance committees as having "an important role in raising awareness to their constituencies and in supporting initiatives that [would] end the war immediately".[145]

On 22 and 23 April, protests against the conflict were held by residents in Khartoum Bahri, Arbaji, and Damazin.[146]

International

On 19 April, diplomatic missions in Sudan, which included those of Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, South Korea, Spain, Switzerland, Sweden, the United Kingdom, the United States, and the European Union, issued a joint statement calling for fighting parties to observe their obligations under international law, specifically urging them to "protect civilians, diplomats and humanitarian actors," avoid further escalations and initiate talks to "resolve outstanding issues."[147]

Countries

- Algeria called for "joint and urgent action to avoid further escalation and put an end to the fighting".[148]

- Canada closed its embassy in Khartoum until further notice and advised its nationals to avoid all travel to Sudan.[149]

- Chad closed its land border with Sudan.[12] Defence Minister Daoud Yaya Brahim expressed concern that the interception of Sudanese soldiers within Chadian territory on 17 April could spill over into Darfur.[150]

- China said that it was "closely following the latest developments" and called on both sides to end the fighting "as soon as possible" and prevent any escalation of tensions.[151][152]

- Egypt's President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi and South Sudan's President Salva Kiir, both of whom lead two of Sudan's neighboring countries, offered to mediate between the warring sides.[153] Egypt also closed its border with Sudan.[154]

- Eritrea's President Isaias Afwerki publicly criticized both the SAF and the RSF for hijacking the Sudanese Revolution and for their conduct in the conflict, calling for the existence of only one army in Sudan. While he said that the country's borders were open to those affected by the fighting, he insisted that no refugee camps would be established in Eritrea.[155]

- Ethiopia and Kenya both urged restraint in light of the situation.[156] Kenya had also announced they would evacuate their citizens, but the fighting in Sudan has delayed those plans.[157]

- India's Prime Minister Narendra Modi chaired a high-level meeting on 21 April to discuss the situation in Sudan and prepare measures for the security and evacuation of its citizens there.[158][159]

- Israel proposed hosting Generals Burhan and Dagalo for ceasefire talks, saying one of its senior officials was doing progress in mediating between the two.[160]

- Malaysia's Ministry of Foreign Affairs condemned the violence and called for meaningful dialogue between all parties involved in the conflict.[161] Foreign Minister Zambry Abdul Kadir revealed that the ministry had activated a "Sudan Operation" and a special team to ensure their safety and welfare.[162]

- Norway has advised its citizens to avoid any travel to Sudan.[163]

- Pakistan's Ministry of Foreign Affairs stated that it was closely monitoring the security situation in Sudan and contacting the thousand-member Pakistani population in Khartoum to ensure their safety.[164][165]

- Portugal's President Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa announced Sunday in a press conference with Brazil's President Lula da Silva that Portugal would work with Brazil to begin a "rapid withdrawal" of both Portuguese and Brazilian nationals.[166]

- Saudi Arabia’s foreign minister Prince Faisal bin Farhan Al Saud made two phone calls on 16 April with Generals Burhan and Dagalo calling for an end to the violence and the resumption of the transition to a civilian-led government in Sudan.[167]

- South Africa announced that it would begin evacuating South African citizens from Sudan on 24 April. President Cyril Ramaphosa also said that South Africa would assist neighboring countries with the return of their citizens as well.[168]

- Spain's Foreign Minister José Manuel Albares said that its government supports efforts to restore peace to Sudan and continue its democratic transition.[169]

- Sweden's Prime Minister Ulf Kristersson said the government will evacuate its embassy staff and their families from Sudan as soon as an available situation appears.[170]

- Tanzania said it was planning to evacuate its 210 citizens from Sudan. Foreign Minister Stergomena Tax told parliament that the government was communicating with the Tanzanian embassy in Khartoum for updates and coordinating with neighboring countries and bodies such as the African Union and the United Nations.[171]

- Turkey's President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan held separate phone calls with Generals Burhan and Dagalo calling on both sides to end the conflict and return to negotiations.[172]

- United Kingdom Foreign Secretary James Cleverly cut short a visit to New Zealand and cancelled a succeeding trip to Samoa to focus on monitoring the situation in Sudan.[173]

- United States Secretary of State Antony Blinken called for de-escalation and peace talks.[174] He reiterated demands for a ceasefire in separate phone calls with Generals Burhan and Dagalo[175] and called an attack on a US diplomatic convoy in Darfur on 17 April as "reckless, irresponsible and unsafe". President Joe Biden ordered an additional deployment of troops to its base in Djibouti to assist in the evacuation of American citizens from Sudan.[176] On 4 May, he issued an executive order authorizing sanctions for those deemed responsible for destabilizing the country, undermining the democratic transition and communicating human rights abuses.[177]

- In his Sunday message from Vatican City on 23 April, Pope Francis called the situation in Sudan grave and called for dialogue between the warring factions.[178]

Organizations

- The African Union called for a political solution to the crisis. The body's Peace and Security Council said that it "strongly rejects any external interference that could complicate the situation in Sudan" after an emergency meeting.[13][179] It also announced that the head of the African Union Commission, Moussa Faki, was planning to "immediately" go on a ceasefire mission to Sudan.[180]

- The Arab League called for an immediate end to the violence in Sudan and offered to mediate between the country's warring sides in a statement issued following an emergency meeting in Cairo.[181]

- The European Union's foreign policy chief Josep Borrell confirmed EU staff were all accounted for and called for an immediate end to the violence.[182] He also called the attack on its Ambassador Aidan O'Hara in Khartoum a gross violation of the Vienna Convention.[183] EU spokeswoman Nabila Massrali told AFP news agency the EU delegation had not been evacuated from Khartoum following the attack.[69]

- The Intergovernmental Authority on Development, an East African trade bloc, held an emergency meeting on the situation in Sudan and said it plans to send Kenyan President William Ruto, South Sudanese President Salva Kiir and Djiboutian President Ismail Omar Guelleh to Khartoum as soon as possible to reconcile the conflicting groups.[154]

- United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres called for an immediate cessation of all hostilities[184] and condemned the killing of several World Food Programme employees in Sudan, describing the deaths as "appalling".[185] He also expressed concern that the conflict in Sudan could escalate into a disastrous regional conflict.[186]

Notes

References

- ^ a b c Faucon, Benoit; Said, Summer; Malsin, Jared (19 April 2023). "Libyan Militia and Egypt's Military Back Opposite Sides in Sudan Conflict". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 19 April 2023. Retrieved 19 April 2023.

"Mr. Haftar, who is backed by Russia and the United Arab Emirates, sent at least one shipment of ammunition on Monday (17 April) from Libya to Sudan to replenish supplies for Gen. Dagalo," the people familiar with the matter said.

- ^ a b "Sudan's army chief says Haftar denies supporting RSF; no confirmation on Wagner Group's involvement". Al-Ahram. 22 April 2023. Archived from the original on 25 April 2023. Retrieved 25 April 2023.

- ^ "Exclusive: Evidence emerges of Russia's Wagner arming militia leader battling Sudan's army". CNN. Archived from the original on 6 May 2023. Retrieved 6 May 2023.

- ^ Faucon, Benoit; Said, Summer; Malsin, Jared (19 April 2023). "Libyan Militia and Egypt's Military Back Opposite Sides in Sudan Conflict". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 19 April 2023. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

Egypt...sent jet fighters just before the fighting started and additional pilots soon after to support Gen. Burhan

- ^ a b الدعم السريع: نتعرض لهجوم من طيران أجنبي في بورتسودان [Rapid Support: We are under attack from foreign aircraft in Port Sudan] (in Arabic). Al Arabiya. 16 April 2023. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 18 April 2023.

- ^ a b Rickett, Oscar (18 April 2023). "Sudan and a decade-long path to turmoil". Middle East Eye. Archived from the original on 18 April 2023. Retrieved 18 April 2023.

The Egyptians are already heavily involved," Cameron Hudson, a former CIA analyst, told MEE. "They are actively in the fight. There are Egyptian fighter jets that are part of these bombing campaigns. Egyptian special forces units have been deployed and the Egyptians are providing intelligence and tactical support to the SAF.

- ^ Sudan: Deadly Sudan Army-RSF Clashes Spark Human Tragedy, Widespread Looting in Darfur Archived 19 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine, 17 April 2023

- ^ Salih, Zeinab (16 April 2023). "Sudan fighting rages for second day despite UN-proposed ceasefire". Archived from the original on 16 April 2023.

- ^ a b "Sudan: Stalemates rule out one-man victory". DW. 19 April 2023. Archived from the original on 19 April 2023. Retrieved 19 April 2023.

- ^ a b c "Sudan ceasefire eases fighting as army denies rumors about deposed dictator Omar al-Bashir's whereabouts". CBS News. Archived from the original on 26 April 2023. Retrieved 26 April 2023.

- ^ a b c "No sign Sudan warring parties ready to 'seriously negotiate': UN". Aljazeera. 26 April 2023. Archived from the original on 26 April 2023. Retrieved 26 April 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Salih, Zeinab Mohammed; Igunza, Emmanuel (15 April 2023). "Sudan: Army and RSF battle over key sites, leaving 56 civilians dead". BBC News. British Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 15 April 2023. Retrieved 15 April 2023.

- ^ a b "At least 25 killed, 183 injured in ongoing clashes across Sudan as paramilitary group claims control of presidential palace". CNN. 15 April 2023. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 15 April 2023.

- ^ Mullany, Gerry (15 April 2023). "Sudan Erupts in Chaos: Who Is Battling for Control and Why It Matters". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 15 April 2023. Retrieved 15 April 2023.

- ^ Akinwotu, Emmanuel (15 April 2023). "Gunfire and explosions erupt across Sudan's capital as military rivals clash". Lagos, Nigeria: NPR. Archived from the original on 15 April 2023. Retrieved 15 April 2023.

- ^ Barbaro, Michael; Zadie, Mooj; Ploeg, Luke Vander; Toeniskoetter, Clare; Wilson, Mary; Novetsky, Rikki; Badejo, Anita; Georges, Marc; Powell, Dan (24 April 2023). "How Two Generals Led Sudan to the Brink of Civil War". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 25 April 2023. Retrieved 25 April 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f Fulton, Adam; Holmes, Oliver (25 April 2023). "Sudan conflict: why is there fighting and what is at stake in the region?". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 3 May 2023. Retrieved 26 April 2023.

- ^ Sawant, Ankush B. (1998). "Ethnic Conflict in Sudan in Historical Perspective". International Studies. 35 (3): 343–363. doi:10.1177/0020881798035003006. ISSN 0020-8817. S2CID 154750436. Archived from the original on 16 April 2023. Retrieved 17 April 2023.

- ^ Fluehr-Lobban, Carolyn (1990). "Islamization in Sudan: A Critical Assessment". Middle East Journal. 44 (4): 610–623. ISSN 0026-3141. JSTOR 4328193. Archived from the original on 27 February 2023. Retrieved 15 April 2023.

- ^ "Sudan: The basics". BBC News. 17 April 2023. Archived from the original on 15 April 2023. Retrieved 17 April 2023.

- ^ Fabricius, Peter (31 July 2020). "Sudan, a coup laboratory". Institute for Security Studies. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 17 April 2023.

- ^ Biajo, Nabeel (22 October 2022). "Military Rule No Longer Viable in Sudan: Analyst". VOA Africa. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 17 April 2023.

- ^ a b Abdelaziz, Khalid; Eltahir, Nafisa; Eltahir, Nafisa (15 April 2023). MacSwan, Angus (ed.). "Sudan's army chief, paramilitary head ready to de-escalate tensions, mediators say". Reuters. Archived from the original on 15 April 2023. Retrieved 15 April 2023.

- ^ a b Magdy, Samy; Krauss, Joseph (20 May 2019). "Sudanese general's path to power ran through Darfur". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 26 April 2023. Retrieved 3 May 2023.

- ^ a b Who is 'Hemedti', general behind Sudan's feared RSF force? Archived 27 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine, Al Jazeera (April 16, 2023).

- ^ a b c Harriet Barber, 'Men with no mercy’: The vicious history of Sudan's Rapid Support Forces Archived 26 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine, Telegraph (April 25, 2023).

- ^ a b c Factbox: Who are Sudan's Rapid Support Forces? Archived 14 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine, Reuters (April 15, 2023).

- ^ a b c d e Michael Georgy, How Sudan's Hemedti carved his route to power Archived 24 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine, Reuters (April 15, 2023)

- ^ a b Elbagir, Nima; Qiblawi, Tamara (15 April 2023). "How paramilitary group leader Dagalo has consolidated power in Sudan". CNN. Archived from the original on 16 April 2023. Retrieved 16 April 2023.

- ^ a b Uras, Umut; Gadzo, Mersiha; Siddiqui, Usaid. "Sudan updates: Explosions, shooting rock Khartoum". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 15 April 2023. Retrieved 15 April 2023.

- ^ a b c d Sudan timeline: From the fall of Bashir to street-fighting in Khartoum Archived 23 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine, Middle East Eye (18 April 2023).

- ^ a b c d Jack Jeffrey & Samy Magdt, Deal to restore democratic transition in Sudan delayed again Archived 16 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine, Associated Press (April 7, 2023).

- ^ a b Olewe, Dickens (20 February 2023). "Mohamed 'Hemeti' Dagalo: Top Sudan military figure says coup was a mistake". BBC News. Archived from the original on 22 March 2023. Retrieved 22 March 2023.

- ^ "Stopping Sudan's Descent into Full-Blown Civil War". International Crisis Group. 20 April 2023. Archived from the original on 23 April 2023. Retrieved 22 April 2023.

- ^ "Egypt calls for maximum restraint in Sudan amid military clashes". Middle East Monitor. 15 April 2023. Archived from the original on 15 April 2023. Retrieved 16 April 2023.

- ^ Walsh, Declan (15 April 2023). "Gunfire and Blasts Rock Sudan's Capital as Factions Vie for Control". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 15 April 2023. Retrieved 15 April 2023.

- ^ "Sudan unrest: How did we get here?". Middle East Eye. 15 April 2023. Archived from the original on 15 April 2023. Retrieved 16 April 2023.

- ^ "At least 56 killed, hundreds injured in clashes across Sudan as paramilitary group claims control of presidential palace". CNN. 16 April 2023. Archived from the original on 16 April 2023. Retrieved 16 April 2023.

- ^ a b Sudan: clashes around the presidential palace, there are fears of a coup attempt in Khartoum – video Archived 15 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine, 15 April 2023.

- ^ "Fears in Sudan as army and paramilitary force face off". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 14 April 2023. Retrieved 15 April 2023.

- ^ "At least 436 civilians killed: Sudan Doctors Syndicate". Aljazeera. 1 May 2023. Archived from the original on 1 May 2023. Retrieved 2 May 2023.

- ^ "Nine children killed in Sudan fighting – Unicef". www.bbc.com. 20 April 2023. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 20 April 2023.

- ^ "Sudan fighting in its 23rd day: A list of key events". Al Jazeera. 7 May 2023. Retrieved 7 May 2023.

- ^ "Nearly 100 people dead across Sudan". Al Jazeera. 17 April 2023. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 17 April 2023.

- ^ a b c لحظة بلحظة.. اشتباكات بين الجيش السوداني والدعم السريع. Al Jazeera (in Arabic). Archived from the original on 15 April 2023. Retrieved 15 April 2023.

- ^ a b السودان.. اشتباكات عنيفة بين الجيش وقوات الدعم السريع (لحظة بلحظة). Al Jazeera (in Arabic). Archived from the original on 15 April 2023. Retrieved 16 April 2023.

- ^ "Two dead after shell hits plane on Khartoum runway – reports". BBC News. Archived from the original on 19 April 2023. Retrieved 18 April 2023.

- ^ "UN envoy says 185 people killed, 1,800 wounded". Aljazeera. 18 April 2023. Archived from the original on 18 April 2023. Retrieved 18 April 2023.

- ^ a b "Residents flee Khartoum as battles rage for fifth day". BBC News. 19 April 2023. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 19 April 2023.

- ^ "Student shot and buried in Sudan university campus". BBC News. 18 April 2023. Archived from the original on 19 April 2023. Retrieved 18 April 2023.

- ^ "Students trapped, hospitals shelled and diplomats assaulted as Sudan fighting intensifies". CNN. 18 April 2023. Archived from the original on 18 April 2023. Retrieved 18 April 2023.

- ^ "Sudan fighting: 39 hospitals 'bombed out of service'". BBC News. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 19 April 2023.

- ^ "Sudan crisis: Actress Asia Abdelmajid killed in Khartoum cross-fire". BBC News. Archived from the original on 5 May 2023. Retrieved 5 May 2023.

- ^ "مراسل العربية: مقتل شخصين وإصابة 26 آخرين من المدنيين في الخرطوم بحري #العربية_عاجل". Archived from the original on 15 April 2023. Retrieved 15 April 2023.

- ^ "North Darfur hospital overwhelmed with wounded". BBC News. 21 April 2023. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 21 April 2023.

- ^ "سقوط قتلى وجرحي جراء اشتباكات بين الجيش والدعم السريع بالفاشر". موقع دارفور٢٤ الاخباري (in Arabic). 15 April 2023. Archived from the original on 15 April 2023. Retrieved 16 April 2023.

- ^ "Sudan group: Dozens killed in fighting between army, paramilitary". CBS News. Archived from the original on 15 April 2023. Retrieved 16 April 2023.

- ^ "Could an old tribal foe undercut Sudan's Hemedti?". Aljazeera. Archived from the original on 3 May 2023. Retrieved 3 May 2023.

- ^ "Diplomat Says 15 Syrians Killed Amid Clashes in Sudan". Asharq Al-Awsat. 27 April 2023. Archived from the original on 4 May 2023. Retrieved 4 May 2023.

- ^ "Dozens killed as fighting between Sudan military rivals enters a second day". CNN. 16 April 2023. Archived from the original on 16 April 2023. Retrieved 16 April 2023.

- ^ "US confirms second American death in Sudan, seeks extended cease-fire". Arab News. 26 April 2023. Archived from the original on 26 April 2023. Retrieved 26 April 2023.

- ^ Kolinovsky, Sarah (27 April 2023). "2nd American dies amid violence in Sudan, White House official says". ABC News. Archived from the original on 3 May 2023. Retrieved 3 May 2023.

- ^ "Turkish toddler killed in ongoing clashes in Sudan". www.aa.com. 18 April 2023. Archived from the original on 20 April 2023. Retrieved 20 April 2023.

- ^ "Egypt denies killing of assistant military attaché by RSF fire". Al Jazeera. 24 April 2023. Archived from the original on 25 April 2023. Retrieved 25 April 2023.

- ^ "Trapped in a church in Sudan with no food or water". BBC News. 19 April 2023. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 19 April 2023.

- ^ "Σουδάν: Δραματική κατάσταση για τους Έλληνες εγκλωβισμένους και τραυματίες – Χωρίς προμήθειες, ιατρική περίθαλψη και ρεύμα" [Sudan: Dramatic situation for Greeks stranded and injured – No supplies, medical care and electricity]. www.ethnos.gr (in Greek). 18 April 2023. Archived from the original on 20 April 2023. Retrieved 22 April 2023.

- ^ "Filipino injured in Sudan clashes; 80 requesting to be rescued: DFA". news.abs-cbn.com. 20 April 2023. Archived from the original on 20 April 2023. Retrieved 20 April 2023.

- ^ "1 WNI Terluka Kena Peluru Nyasar saat Terjebak Perang Saudara di Sudan" [1 Indonesian Citizen Injured by Stray Bullets while Trapped in Civil War in Sudan]. www.cnnindonesia.com (in Indonesian). 18 April 2023. Archived from the original on 18 April 2023. Retrieved 22 April 2023.

- ^ a b "Sudan fighting: EU ambassador assaulted in Khartoum home". BBC News. 17 April 2023. Archived from the original on 18 April 2023. Retrieved 17 April 2023.

- ^ "Sudan fighting: Special forces airlift US diplomats from Sudan". BBC News. 23 April 2023. Archived from the original on 23 April 2023. Retrieved 23 April 2023.

- ^ "France evacuated 538 people, Macron says". Al Jazeera. 25 April 2023. Archived from the original on 25 April 2023. Retrieved 25 April 2023.

- ^ "Foreign powers rescue nationals while Sudanese must fend for themselves". CNN. 23 April 2023. Archived from the original on 23 April 2023. Retrieved 24 April 2023.

- ^ إصابة أحد أعضاء السفارة المصرية بالخرطوم بطلق ناري (in Arabic). Al-Ittihad. 23 April 2023. Archived from the original on 23 April 2023. Retrieved 24 April 2023.

- ^ Gridneff, Matina Stevis; Walsh, Declan (18 April 2023). "The E.U.'s top humanitarian aid officer in Sudan was shot in Khartoum". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 18 April 2023. Retrieved 19 April 2023.

- ^ "Humanitarian worker killed in Sudan crossfire, IOM says". Reuters. 21 April 2023. Archived from the original on 21 April 2023. Retrieved 21 April 2023.

- ^ "Sudanese Army agrees to 24-hour ceasefire". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 18 April 2023. Retrieved 18 April 2023.

- ^ Burke, Jason; Salih, Zeinab Mohammed (23 April 2023). "Libyan warlord could plunge Sudan into a drawn-out 'nightmare' conflict". The Observer. Archived from the original on 25 April 2023. Retrieved 25 April 2023.

- ^ "Libya denies involvement in Sudan fighting". BBC News. BBC. 20 April 2023. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 20 April 2023.

- ^ Craze, Joshua (17 April 2023). "Gunshots in Khartoum". New Left Review. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 19 April 2023.

- ^ Dewaal, Alex (19 April 2023). "Sudan's New War and Prospects for Peace". Reinventing peace. Archived from the original on 21 April 2023. Retrieved 21 April 2023.

- ^ Elbagir, Nima; Mezzofiore, Gianluca; Qiblawi, Tamara (20 April 2023). "Exclusive: Evidence emerges of Russia's Wagner arming militia leader battling Sudan's army". CNN. Archived from the original on 20 April 2023. Retrieved 20 April 2023.

The Russian mercenary group Wagner has been supplying Sudan's Rapid Support Forces (RSF) with missiles to aid their fight against the country's army, Sudanese and regional diplomatic sources have told CNN. The sources said the surface-to-air missiles have significantly buttressed RSF paramilitary fighters and their leader Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo

- ^ Schmitt, Eric; Wong, Edward (23 April 2023). "United States Says Wagner Has Quietly Picked Sides in Sudan". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 24 April 2023. Retrieved 25 April 2023.

Yevgeny Prigozhin, the founder of the notorious private military company Wagner, has offered weapons to the paramilitaries fighting for control of Sudan, according to American officials.

- ^ "Russia's Lavrov: Sudan has the right to use Wagner Group". Aljazeera. Aljazeera. 26 April 2023. Archived from the original on 25 April 2023. Retrieved 26 April 2023.

- ^ "Russia's Wagner denies involvement in Sudan crisis". BBC. 19 April 2023. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 19 April 2023.

- ^ "On behalf of the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) we would like to address the recent article published by CNN. In these times of information warfare and fake news, we stand as the steadfast defenders of truth, justice, and the will of the Sudanese people". Twitter. 21 April 2023. Archived from the original on 21 April 2023. Retrieved 22 April 2023.

- ^ "Russia's Lavrov pledges support on lifting UN sanctions, defends Wagner on Sudan visit". France 24. 9 February 2023. Archived from the original on 25 February 2023. Retrieved 16 April 2023.

- ^ Mohammed Amin (18 January 2023). "Hemeti's CAR coup boast sheds light on Sudanese role in conflict next door". Middle East Eye. Archived from the original on 30 March 2023. Retrieved 16 April 2023.

- ^ Tack, Sim; Rogoway, Tyler (17 April 2023). "Egyptian MiG-29s Destroyed In Sudan". The War Zone. Archived from the original on 18 April 2023. Retrieved 18 April 2023.

- ^ "Sudan's RSF says it's ready to cooperate over Egyptian troops". Reuters. 15 April 2023. Archived from the original on 15 April 2023. Retrieved 16 April 2023.

- ^ "Sudan paramilitary group says it has seized presidential palace and Khartoum airport amid clashes with army – live". The Guardian. 15 April 2023. Archived from the original on 19 April 2023.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 18 April 2023 suggested (help) - ^ a b "Egyptian soldiers captured in Sudan to be returned, says RSF". Aljazeera. 16 April 2023. Archived from the original on 16 April 2023. Retrieved 16 April 2023.

- ^ "Sudan's paramilitary shares video they claim shows 'surrendered' Egyptian troops". al-Arabiya. 15 April 2023. Archived from the original on 15 April 2023. Retrieved 15 April 2023.

- ^ @AlArabiya_Brk (15 April 2023). "مراسل العربية: الجيش السوداني يطوق مطار مروي العسكري" [Al-Arabiya correspondent: The Sudanese army encircled the Merowe military airport] (Tweet) (in Arabic) – via Twitter.

- ^ "Egyptian soldiers in Sudan moved from airbase – RSF". BBC. 19 April 2023. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 19 April 2023.

- ^ "Egyptian air force personnel remain in Khartoum: Sudanese army corrects earlier statement". Aljazeera. 20 April 2023. Archived from the original on 20 April 2023. Retrieved 20 April 2023.

- ^ "Egyptian army says soldiers stuck in Sudan back home or at embassy". Reuters. 20 April 2023. Archived from the original on 20 April 2023. Retrieved 21 April 2023.

- ^ "عاجل (السُّوداني): الجيش يوقف غزواً إثيوبياً على الفشقة الصغرى ويُكبِّدهم خسائر فادحة في الأرواح والعتاد". Al Sudani. 19 April 2023. Archived from the original on 19 April 2023. Retrieved 20 April 2023.

Ethiopian forces carried out an invasion and attack on Al-Fashqa, reinforced by tanks, armored vehicles, and large crowds of infantry. Immediately, the armed forces units dealt with them with their various long-range fire systems, causing them heavy losses in personnel and equipment

- ^ "Ethiopian PM denies reports of clashes with Sudan forces". BBC. 20 April 2023. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 21 April 2023.

- ^ "PM Abiy Ahmed warns parties working to incite war between Ethiopia, Sudan, refutes reports of Ethiopian forces incursion into Sudanese border". Addis Standard. 20 April 2023. Archived from the original on 20 April 2023. Retrieved 22 April 2023.

- ^ "Foreigners evacuated as factions battle in Sudan's Khartoum". Al Jazeera. 23 April 2023. Archived from the original on 24 April 2023. Retrieved 23 April 2023.

- ^ Hansler, Jennifer; Atwood, Kylie; Britzky, Haley; Liebermann, Oren (23 April 2023). "US has evacuated American diplomatic personnel from Sudan". CNN. Archived from the original on 24 April 2023. Retrieved 24 April 2023.

- ^ "Which countries have evacuated nationals from Sudan?". Al Jazeera. 23 April 2023. Archived from the original on 21 April 2023. Retrieved 24 April 2023.

- ^ "How the crisis in Sudan accentuated the strategic importance of Djibouti". Observer Research Foundation. 25 April 2023. Archived from the original on 26 April 2023. Retrieved 26 April 2023.

- ^ Dahir, Abdi Latif (17 April 2023). "As New Wave of Violence Hits Sudan's Capital, Civilians Feel the Strain". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 17 April 2023.

- ^ a b "Sudan crisis: Civilians facing 'catastrophe' as 100,000 flee fighting - UN". BBC. 2 May 2023. Archived from the original on 2 May 2023. Retrieved 2 May 2023.

- ^ "More than 60% of hospitals out of service". Aljazeera. 22 April 2023. Archived from the original on 20 April 2023. Retrieved 23 April 2023.

- ^ Uras, Umut (25 April 2023). "Supply shortages becoming 'extremely acute' – UN". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 25 April 2023. Retrieved 25 April 2023.

- ^ "Sudan residents face cash shortage as sources dry up". Al Jazeera. 28 April 2023. Archived from the original on 28 April 2023. Retrieved 28 April 2023.

- ^ "President Biden authorises sanctions against Sudan". BBC. 4 May 2023. Archived from the original on 5 May 2023. Retrieved 5 May 2023.

- ^ "Clashes rock Sudan ceasefire as UN official seeks aid protection". Al Jazeera. 3 May 2023. Archived from the original on 3 May 2023. Retrieved 3 May 2023.

- ^ "More than 800,000 people may flee Sudan: UN". Al Jazeera. 1 May 2023. Archived from the original on 1 May 2023. Retrieved 1 May 2023.

- ^ "Sudanese army and RSF back 'urgent humanitarian ceasefire'". BBC News. Archived from the original on 15 April 2023. Retrieved 16 April 2023.

- ^ "Sudan approves passage for urgent humanitarian cases". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 16 April 2023. Retrieved 16 April 2023.

- ^ "UN envoy to Sudan 'disappointed' by ceasefire violations". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 17 April 2023.

- ^ "Sudan fighting: RSF and army clash in Khartoum for third day". BBC News. 16 April 2023. Archived from the original on 16 April 2023. Retrieved 17 April 2023.

- ^ "RSF leader agrees to 24-hour armistice". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 18 April 2023. Retrieved 18 April 2023.

- ^ "Sudan's army denies knowledge of ceasefire". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 18 April 2023. Retrieved 18 April 2023.

- ^ "Gunfire, shelling in Khartoum despite truce: Resident". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 18 April 2023. Retrieved 19 April 2023.

- ^ "Fighting continues in Sudan hours after ceasefire was to begin". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 19 April 2023. Retrieved 19 April 2023.

- ^ "Army agrees to 24-hour ceasefire". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 19 April 2023. Retrieved 20 April 2023.

- ^ "Thousands flee as new ceasefire attempt fails in Sudan". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 20 April 2023. Retrieved 20 April 2023.

- ^ "Sudan's RSF announces 72-hour ceasefire amid Khartoum fighting". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 21 April 2023. Retrieved 21 April 2023.

- ^ Osman, Mohamed; Booty, Natasha (21 April 2023). "Sudan fighting: Muted Eid as ceasefire broken". BBC News. Archived from the original on 21 April 2023. Retrieved 21 April 2023.

- ^ "Sudan's army says it agrees to three-day truce starting Friday". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 21 April 2023. Retrieved 22 April 2023.

- ^ Hansler, Jennifer; Judd, Donald (24 April 2023). "3-day Sudan ceasefire announced by US Secretary of State". CNN. Archived from the original on 24 April 2023. Retrieved 24 April 2023.

- ^ Siddiqui, Usaid (25 April 2023). "Sporadic gunfire in Khartoum despite new truce". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 25 April 2023. Retrieved 25 April 2023.

- ^ "Sudan army chief backs ceasefire extension as skirmishes continue". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 27 April 2023. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

- ^ "Sudan's army and RSF say ceasefire extended but fighting goes on". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 28 April 2023. Retrieved 28 April 2023.

- ^ "Fighting rages despite ceasefire announcement". Al Jazeera. 28 April 2023. Archived from the original on 28 April 2023. Retrieved 28 April 2023.

- ^ "Humanitarian truce extended: RSF". Aljazeera. 30 April 2023. Archived from the original on 30 April 2023. Retrieved 30 April 2023.

- ^ "Sudan army says it agreed to extend truce with RSF". Aljazeera. 30 April 2023. Archived from the original on 30 April 2023. Retrieved 30 April 2023.

- ^ "Gun battles rage in central Khartoum despite announced truce". Aljazeera. 30 April 2023. Archived from the original on 30 April 2023. Retrieved 1 May 2023.

- ^ "Rivals agree to send representatives to UN negotiations: AJ correspondent". Aljazeera. 2 May 2023. Archived from the original on 1 May 2023. Retrieved 2 May 2023.

- ^ "Sudan rivals agree 'in principle' to a week's truce". BBC. 2 May 2023. Archived from the original on 2 May 2023. Retrieved 2 May 2023.

- ^ "Fighting continues in Khartoum with a ceasefire broken by both sides". TVP. 4 May 2023. Archived from the original on 5 May 2023. Retrieved 5 May 2023.

- ^ a b "Sudan activists 'reject both warlords, call for participation in peace talks'". Radio Dabanga. 7 May 2023. Wikidata Q118203275. Archived from the original on 7 May 2023.

- ^ "Rival Sudan factions meet in Saudi Arabia as pressure mounts". Aljazeera. 6 May 2023. Archived from the original on 6 May 2023. Retrieved 6 May 2023.

- ^ "Sudan's warring military factions to meet face-to-face for first time since conflict began". CNN. Archived from the original on 6 May 2023. Retrieved 6 May 2023.

- ^ "wahdat altahaquq bialjazirat mubashir takshif haqiqat maqatie fidyu nasharaha aljaysh alsuwdaniu wawasayil 'iielam (fidyu)" وحدة التحقق بالجزيرة مباشر تكشف حقيقة مقاطع فيديو نشرها الجيش السوداني ووسائل إعلام (فيديو) [The Al-Jazeera Mubasher Verification Unit reveals the truth about video clips published by the Sudanese army and media (video)]. Al Jazeera (in Arabic). Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 17 April 2023.

- ^ PesaCheck (19 April 2023). "PARTLY FALSE: Two of these photos are not from the April 2023 Sudan unrest". Medium. Archived from the original on 23 April 2023. Retrieved 21 April 2023.

- ^ Malashenko, Uliana (27 April 2023). "Fact Check: Video Does NOT Show 'Sudan Rapid Support Force' In Control Of 'Khartoum International Airport And Military Base' On April 15, 2023". Lead Stories. Retrieved 4 May 2023.

- ^ "RSF head calls for international community to intervene". BBC News. Archived from the original on 15 April 2023. Retrieved 17 April 2023.

- ^ Magdy, Samy; Gambrell, Jon (16 April 2023). "Sudan's army and rival force battle, killing at least 56". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 15 April 2023. Retrieved 16 April 2023.

- ^ a b "Sudan analyst says SAF chance of victory is higher, but fears return of former regime". Radio Dabanga. 18 April 2023. Wikidata Q117787667. Archived from the original on 18 April 2023.

- ^ Mat Nashed (22 April 2023). "Sudan 'resistance' activists mobilise as crisis escalates". Al Jazeera English. Wikidata Q117832530. Archived from the original on 23 April 2023.

- ^ "Fighting leads to internet cuts, Sudanese protests against the war". Radio Dabanga. 24 April 2023. Archived from the original on 25 April 2023. Retrieved 25 April 2023.

- ^ "Diplomatic missions call for ceasefire". Al Jazeera. 19 April 2023. Archived from the original on 19 April 2023. Retrieved 19 April 2023.

- ^ "Situation in Sudan: President of the Republic sends messages to UN SG, AU President and IGAD Executive Secretary". Algeria Press Service. 18 April 2023. Archived from the original on 18 April 2023. Retrieved 18 April 2023.

- ^ Canada, Global Affairs (16 November 2012). "Travel advice and advisories for Sudan". Travel.gc.ca. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 18 April 2023.

- ^ "Sudanese soldiers stopped, disarmed by Chad's army". Al Jazeera. 19 April 2023. Archived from the original on 19 April 2023. Retrieved 20 April 2023.

- ^ "China, highly concerned about Sudan situation, calls for ceasefire". Reuters. Reuters. 16 April 2023. Archived from the original on 18 April 2023. Retrieved 18 April 2023.

- ^ "Foreign Ministry Spokesperson's Remarks on the Armed Clashes in Sudan". az.china-embassy.gov.cn. Archived from the original on 25 April 2023. Retrieved 24 April 2023.

- ^ "Egypt and South Sudan offer to mediate between Sudanese sides". Aljazeera. 16 April 2023. Archived from the original on 16 April 2023. Retrieved 16 April 2023.

- ^ a b "Fierce fighting continues in Sudan after brief humanitarian pause". Aljazeera. 17 April 2023. Archived from the original on 16 April 2023. Retrieved 17 April 2023.

- ^ Bekit, Teklemariam (1 May 2023). "Sudan should only have one army - Eritrea's president". BBC. Archived from the original on 2 May 2023. Retrieved 1 May 2023.

- ^ Abdelaziz, Khalid; Eltahir, Nafisa; Eltahir, Nafisa (15 April 2023). "Sudan clashes kill at least 25 in power struggle between army, paramilitaries". Reuters. Archived from the original on 15 April 2023. Retrieved 17 April 2023.

- ^ "Germany cancels evacuation mission in Sudan – report". BBC. 19 April 2023. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 19 April 2023.

- ^ "PM Modi chairs meet on Sudan crisis, asks officials to prepare evacuation plans for stranded Indians". India Today. 21 April 2023. Archived from the original on 22 April 2023. Retrieved 21 April 2023.

- ^ "Make plans to get Sudan Indians home: PM Modi". Times Of India. 22 April 2023. Archived from the original on 22 April 2023. Retrieved 22 April 2023.

- ^ "Israel proposes hosting Sudan rivals for ceasefire talks". Al Jazeera. 24 April 2023. Archived from the original on 25 April 2023. Retrieved 25 April 2023.

- ^ "Malaysia condemns Armed Forces-RSF hostilities in Sudan, says Wisma Putra". The Star. Archived from the original on 16 April 2023. Retrieved 16 April 2023.

- ^ "Sudan conflict: Wisma Putra doing its best to bring home stranded Malaysians, says Zambry". The Star. 18 April 2023. Archived from the original on 18 April 2023. Retrieved 18 April 2023.

- ^ sh.januzi (18 April 2023). "Norway Warns Its Citizens to Avoid Travel to Sudan". SchengenVisaInfo.com. Archived from the original on 19 April 2023. Retrieved 19 April 2023.

- ^ "Pakistan closely monitoring security situation in Sudan: FO". 15 April 2023. Archived from the original on 19 April 2023. Retrieved 18 April 2023.

- ^ "Pakistan says trying to ensure safety of its nationals in Sudan following coup attempt". 15 April 2023. Archived from the original on 15 April 2023. Retrieved 18 April 2023.

- ^ "Portugal: Trying to help Brazilians trapped in Sudan, hopes for EU assistance". 23 April 2023. Archived from the original on 25 April 2023. Retrieved 24 April 2023.

- ^ "Saudi FM urges halt to military escalation in Sudan in calls with Burhan, RSF leader". 16 April 2023. Archived from the original on 21 April 2023. Retrieved 21 April 2023.

- ^ "South Africa Says Evacuating Citizens from Sudan". Archived from the original on 25 April 2023. Retrieved 24 April 2023.

- ^ "Albares asegura que España no abandonará Sudán pese a la evacuación y trabajará para el regreso de la paz" [Albares ensures that Spain will not abandon Sudan despite the evacuation and will work towards the return of peace]. Europa Press (in Spanish). Madrid. 25 April 2023. Archived from the original on 25 April 2023. Retrieved 25 April 2023.

- ^ "Sweden to evacuate embassy staff from Sudan when possible". Al Jazeera. 21 April 2023. Archived from the original on 21 April 2023. Retrieved 21 April 2023.

- ^ Famau, Aboubakar (19 April 2023). "Tanzania plans to evacuate students from Sudan". BBC News. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 19 April 2023.

- ^ "Turkey calls both sides to end fighting and return to negotiations". Al Jazeera. 20 April 2023. Archived from the original on 20 April 2023. Retrieved 20 April 2023.

- ^ "Britain's top diplomat James Cleverly skips part of Pacific tour to focus on Sudan". The Guardian. 21 April 2023. Archived from the original on 21 April 2023. Retrieved 21 April 2023.

- ^ "US Secretary of State Blinken calls for immediate end to violence in Sudan". Reuters. 15 April 2023. Archived from the original on 15 April 2023. Retrieved 16 April 2023.

- ^ "Blinken Speaks To Sudan Generals, Calls For Ceasefire". Barron's. 17 April 2023. Archived from the original on 19 April 2023. Retrieved 18 April 2023.

- ^ "US deploys more troops to Djibouti for possible Sudan evacuation". Al Jazeera. 20 April 2023. Archived from the original on 21 April 2023. Retrieved 21 April 2023.

- ^ "Biden authorizes future sanctions tied to conflict in Sudan". CNN. 4 May 2023. Archived from the original on 6 May 2023. Retrieved 5 May 2023.

- ^ "Pope Francis urges dialogue over 'grave' situation". Al Jazeera. 23 April 2023. Archived from the original on 23 April 2023. Retrieved 23 April 2023.

- ^ Kodjo, Tchioffo. "Communiqué Adopted by the Peace and Security Council (PSC) of the African Union (AU) at its 1149th meeting, held on 16 April 2023, on Briefing on the situation in Sudan. -African Union – Peace and Security Department". African Union, Peace and Security Department. Archived from the original on 16 April 2023. Retrieved 16 April 2023.

- ^ "African Union chief heading to Sudan". BBC. 17 April 2023. Archived from the original on 15 April 2023. Retrieved 17 April 2023.

- ^ "Arab League calls for an end to 'armed clashes' in Sudan". Aljazeera. 17 April 2023. Archived from the original on 16 April 2023. Retrieved 17 April 2023.

- ^ "EU's Borrell calls on all forces in Sudan to stop violence, says EU staff safe". Reuters. 15 April 2023. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 16 April 2023.

- ^ "EU envoy to Sudan assaulted, says EU foreign policy chief". Al Jazeera. 17 April 2023. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 18 April 2023.

- ^ "UN chief and officials condemn fighting between Sudanese forces | UN News". news.un.org. 15 April 2023. Archived from the original on 15 April 2023. Retrieved 17 April 2023.

- ^ "Death of WFP workers 'appalling' says UN chief". Al Jazeera. 17 April 2023. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 17 April 2023.

- ^ Abdelaziz, Khalid; Lewis, Aidan (24 April 2023). "US says Sudan factions agree to ceasefire as foreigners evacuated". Reuters. Archived from the original on 24 April 2023. Retrieved 24 April 2023.