Mughal Empire: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by 59.94.198.158 (talk) to last version by Balthazarduju |

correct of the word "mughal" in urdu script. |

||

| Line 45: | Line 45: | ||

|currency = [[Rupee]] |

|currency = [[Rupee]] |

||

}} |

}} |

||

The '''Mughal Empire''' ({{PerB|سلطنت مغولی هند}}) ([[Urdu]]:''' |

The '''Mughal Empire''' ({{PerB|سلطنت مغولی هند}}) ([[Urdu]]:'''مغل سلطنت''', self-designation '''''Gurkānī''''', '''گوركانى'''), was an important imperial power in the [[India]]n Subcontinent from the early sixteenth to the mid-nineteenth centuries. At the height of its power, around 1700, it controlled most of the subcontinent and parts of what is now [[Afghanistan]]. Its population at that time has been estimated as between 100 and 150 million, over a territory of over 3 million square km.<ref>John F Richards, [http://www.amazon.com/dp/0521566037/ The Mughal Empire], Vol I.5 of the New Cambridge History of India, Cambridge University Press, 1996</ref> Following 1720 it declined rapidly. Its decline has been variously explained as caused by wars of succession, agrarian crises fueling local revolts, and the growth of religious intolerance. The last [[Emperor]], whose rule was restricted to the city of [[Delhi]], was imprisoned and exiled by the [[British Empire|British]] after the [[Indian Rebellion of 1857]]. |

||

The classic period of the Empire starts with the accession of [[Akbar]] in 1556 and ends with the death of [[Aurangzeb]] in 1707. During this period, the Empire was marked by a strongly centralized administration connecting the different regions of India. All the significant monuments of the Mughals, their most visible legacy, date to this period. |

The classic period of the Empire starts with the accession of [[Akbar]] in 1556 and ends with the death of [[Aurangzeb]] in 1707. During this period, the Empire was marked by a strongly centralized administration connecting the different regions of India. All the significant monuments of the Mughals, their most visible legacy, date to this period. |

||

Revision as of 14:47, 23 July 2007

Mughal Empire گوركانى | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1526–1857 | |||||||||

| Mughal Empire at its greatest extent in 1700 Mughal Empire at its greatest extent in 1700 | |||||||||

| Capital | Agra, Delhi | ||||||||

| Common languages | Persian, Chagatai | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

| List of Mughal emperors | |||||||||

• 1526-1530 | Babur | ||||||||

• 1530–1539 and after restoration 1555–1556 | Humayun | ||||||||

• 1556–1605 | Akbar | ||||||||

• 1605–1627 | Jahangir | ||||||||

• 1628–1658 | Shah Jahan | ||||||||

• 1659–1707 | Aurangzeb | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

| April 21 1526 | |||||||||

• Ended | September 21 1857 | ||||||||

| Area | |||||||||

| 3,000,000 km2 (1,200,000 sq mi) | |||||||||

| Population | |||||||||

• 1700 | 150,000,000 | ||||||||

| Currency | Rupee | ||||||||

| |||||||||

The Mughal Empire (Template:PerB) (Urdu:مغل سلطنت, self-designation Gurkānī, گوركانى), was an important imperial power in the Indian Subcontinent from the early sixteenth to the mid-nineteenth centuries. At the height of its power, around 1700, it controlled most of the subcontinent and parts of what is now Afghanistan. Its population at that time has been estimated as between 100 and 150 million, over a territory of over 3 million square km.[1] Following 1720 it declined rapidly. Its decline has been variously explained as caused by wars of succession, agrarian crises fueling local revolts, and the growth of religious intolerance. The last Emperor, whose rule was restricted to the city of Delhi, was imprisoned and exiled by the British after the Indian Rebellion of 1857.

The classic period of the Empire starts with the accession of Akbar in 1556 and ends with the death of Aurangzeb in 1707. During this period, the Empire was marked by a strongly centralized administration connecting the different regions of India. All the significant monuments of the Mughals, their most visible legacy, date to this period.

Early history

Mughal is the Persian word for Mongol and was generally used to refer to the central Asian nomads who claimed descent from the Mongol warriors of Genghis Khan. The foundation for empire was established around 1504 by the Timurid prince Babur, when he took control of Kabul and eastern regions of Khorasan controlling the fertile Sind region and the lower valley of the Indus River. In 1526, Babur defeated the last of the Delhi Sultans, Ibrahim Shah Lodi, at the First Battle of Panipat. These early military successes of the Mughals in India, achieved by an army much smaller than its opponents, have been attributed to their cohesion, mobility, and horse-mounted archers.

Babur's son Humayun succeeded him in 1530 but suffered major reversals at the hands of the Pashtun Sher Shah Suri and effectively lost most of the fledgling empire before it could grow beyond a minor regional state. From 1540 onwards, Humayun became a ruler in exile, reaching the Court of Persian Safavid ruler in 1542 while his forces still controlled some fortresses and small regions. But when the Afghans fell into disarray with the death of Sher Shah Suri, Humayun returned with a mixed army, raised more troops and managed to reconquer Delhi in 1555.

His son Akbar was an infant when Humayun decided to cross the rough terrain of Makran with his wife, and so was left behind to keep him from the rigors of the long journey. Since he did not go to Persia with his parents, he was eventually transported from the fortress in the Sind where he was born to be raised for a time by his uncle Askari in the rugged country of Afghanistan. There he became an excellent outdoorsman, horseman, hunter and learned the arts of the warrior.

After the resurgent Humayan conquered the central plateau about Delhi, he was killed a few months later in an accident, leaving an unsettled realm still involved in war. Akbar (1556 to 1605) succeeded his father on 14 February 1556, while in the midst of a war against Sikandar Shah Suri for the reclamation of the Mughal throne. Hence he was thrust onto the throne and soon recorded his first victory at the age of 13 or 14, and the rump remnant began to grow, then it grew considerably, so that he became called Akbar, as he was a wise ruler, set fair but steep taxes, he investigated the production in a certain area and the inhabitants were taxed accordingly 1/3 of the agricultural produce. He also set up an efficient bureaucracy and was tolerant of religious differences which softened the resistance by the conquered.

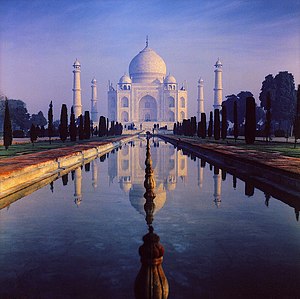

Jahangir, the son of Mughal Emperor Akbar and Rajput princess Mariam-uz-Zamani, ruled the empire from 1605–1627. In October 1627, Shah Jahan, the son of Mughal Emperor Jahangir and Rajput princess Manmati, succeeded to the throne, where he inherited a vast and rich empire in India; and at mid-century this was perhaps the greatest empire in the world. Shah Jahan commissioned the famous Taj Mahal (1630–1653) in Agra as a tomb for his wife Mumtaz Mahal, who died giving birth to their 14th child. By 1700 the empire reached its peak with major parts of present day India, except for the North eastern states and small areas in the south and most of Afganistan under its domain, under the leadership of Aurengzeb Alamgir. Aurengzeb was the last of the powerful Mughal kings. He was a pious Muslim and ended all the extravagance and non-Islamic routines of the court. After his death, the Mughal Empire fell apart very quickly.

Religion

After the invasion of Persia by the Mongol Empire, a regional Turko-Persio-Mongol dynasty formed. Just as eastern Mongol dynasties intermarried with locals and adopted the local religion of Buddhism and Chinese culture, this group adopted the local religion of Islam and Persian culture. The first Mughal King Babur, established Mughal dynasty in India. Upon invading India, the Mughals intermarried with local royalty once again, creating a dynasty of combined Turko-Persian, Indian and Mongol background.

The language of the court was Persian although most of the subjects of the Empire were Hindu. The dynasty remained unstable until the reign of Akbar, who was of liberal disposition and intimately acquainted, since birth, with the mores and traditions of India. Under Akbar's rule, the court abolished the jizya (the poll-tax on non-Muslims) and abandoned use of the lunar Muslim calendar in favor of a solar calendar more useful for agriculture. One of Akbar's most unusual ideas regarding religion was Din-i-Ilahi ("Faith-of-God" in English), which was an eclectic mix of Hinduism, versions of Sufi Islam, Zoroastrianism, Jainism and Christianity. It was proclaimed the state religion until his death. These actions however met with stiff opposition from the Muslim clergy, especially by the Sufi Shaykh Alf Sani Ahmad Sirhindi. The Mughal emperor Akbar is remembered as tolerant, at least by the standards of the day: only one major massacre was recorded during his long reign (1556–1605), when he ordered most of the captured inhabitants of a fort be slain on February 24, 1568, after the battle for Chitor. Akbar's acceptance of other religions and toleration of their public worship, his abolition of poll-tax on non-Muslims, and his interest in other faiths bespeak an attitude of considerable religious tolerance, which, in the minds of his orthodox Muslim opponents, was tantamount to apostasy. Its high points were the formal declaration of his own infallibility in all matters of religious doctrine, his promulgation of a new creed, and his adoption of Hindu and Zoroastrian festivals and practices.

Religious orthodoxy would only play a truly important role during the reign of Aurangzeb Ālamgīr, a devout Muslim and the strongest military commander of the Mughal line; this last of the Great Mughals retracted the liberal policies of his forbears. Although under Aurangzeb, the empire extended to its largest, his rule was thus less popular with the Hindu Rajputs upon whom he depended, and with the rise to military power of the Sikhs, may have been the prime factor in the downfall of the Mughals.

Political economy

The Mughals used the mansabdar system to generate land revenue. The emperor would grant revenue rights to a mansabdar in exchange for promises of soldiers in wartime. The greater the size of the land the emperor granted, the greater the number of soldiers the mansabdar had to promise. The mansab was both revocable and non-hereditary; this gave the center a fairly large degree of control over the mansabdars.

| Mughal Emperors | ||||||||||||

| Emperor | Name | Reign start | Reign end | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Babur | Zahiruddin Mohammed | 1526 | 1530 | |||||||||

| Humayun | Nasiruddin Mohammed | 1530 | 1540 | |||||||||

| Interregnum * | - | 1540 | 1555 | |||||||||

| Humayun | Nasiruddin Mohammed | 1555 | 1556 | |||||||||

| Akbar | Jalaluddin Mohammed | 1556 | 1605 | |||||||||

| Jahangir | Nuruddin Mohammed | 1605 | 1627 | |||||||||

| Shah Jahan | Shihabuddin Mohammed | 1627 | 1658 | |||||||||

| Aurangzeb | Muhiuddin Mohammed | 1658 | 1707 | |||||||||

| Shah Alam I | Muazzam Bahadur | 1707 | 1712 | |||||||||

* Afghan Rule (Sher Shah Suri and his descendants)

Establishment and reign of Babur

In the early 16th century, Muslim armies consisting of Mongol, Turkic, Persian, and Afghan warriors invaded India under the leadership of the Timurid prince Zahir-ud-Din-Muhammad Babur. Babur was the great-grandson of Central Asian conqueror Timur-e Lang (Timur the Lame, from which the Western name Tamerlane is derived), who had invaded India in 1398 before retiring to Samarkand. Timur himself claimed descent from the Mongol ruler, Genghis Khan. Babur was driven from Samarkand by the Uzbeks and initially established his rule in Kabul in 1504. Later, taking advantage of internal discontent in the Delhi sultanate under Ibrahim Lodi, and following an invitation from Daulat Khan Lodhi (governor of Punjab) and Alam Khan (uncle of the Sultan), Babur invaded India in 1526.

Babur, a seasoned military commander, entered India in 1526 with his well-trained veteran army of 12,000 to meet the sultan's huge but unwieldy and disunited force of more than 100,000 men. Babur defeated the Lodhi sultan decisively at the First Battle of Panipat. Employing firearms, gun carts, movable artillery, superior cavalry tactics, and the highly regarded Mughal composite bow, a weapon even more powerful than the English longbow of the same period, Babur achieved a resounding victory and the Sultan was killed. A year later (1527) he decisively defeated, at the Battle of Khanwa, a Rajput confederacy led by Rana Sanga of Chittor. A third major battle was fought in 1529 when, at the battle of Gogra, Babur routed the joint forces of Afghans and the sultan of Bengal. Babur died in 1530 at Agra before he could consolidate his military gains. During his short five-year reign, Babur took considerable interest in erecting buildings, though few have survived. He left behind as his chief legacy a set of descendants who would fulfill his dream of establishing an empire in the Indian subcontinent.

Successors

| History of South Asia |

|---|

|

|

| History of Greater Iran |

|---|

Babur's will to Humayun

According to the document available in the State Library of Bhopal, Babur left the following will to Humayun:[citation needed]

"My son take note of the following: do not harbour religious prejudice in your heart. You should dispense justice while taking note of the people's religious sensitivities, and rites. Avoid slaughtering cows in order that you could gain a place in the heart of natives. This will take you nearer to the people.

"Do not demolish or damage places of worship of any faith and dispense full justice to all to ensure peace in the country. Islam can better be preached by the sword of love and affection, rather than the sword of tyranny and persecution. Avoid the differences between the Shias and Sunnis. Look at the various characteristics of your people just as characteristics of various seasons."

Humayun

When Babur died, his son Humayun (1530–56) inherited a difficult task. He was pressed from all sides by a reassertion of Afghan claims to the Delhi throne and by disputes over his own succession. Driven into Sindh by the armies of Sher Shah Suri, in 1540 he fled to Persia, where he spent nearly ten years as an embarrassed guest of the Safavid court of Shah Tahmasp. During Sher Shah's reign, an imperial unification and administrative framework were established; this would be further developed by Akbar later in the century. In addition the tomb of Sher Shah Suri is an architectural masterpiece that was to have a profound impact on the evolution of Indo-Islamic funerary architecture. In 1545, Humayun gained a foothold in Kabul with Safavid assistance and reasserted his Indian claims, a task facilitated by the weakening of Afghan power in the area after the death of Sher Shah Suri in May 1545. He took control of Delhi in 1555, but died within six months of his return, from a fall down the steps of his library. His tomb at Delhi represents an outstanding landmark in the development and refinement of the Mughal style. It was designed in 1564, eight years after his death, as a mark of devotion by his widow, Hamida Banu Begum.

Akbar

Humayun's untimely death in 1556 left the task of conquest and imperial consolidation to his thirteen-year-old son, Jalal-ud-Din Akbar (r.1556–1605). Following a decisive military victory at the Second Battle of Panipat in 1556, the regent Bairam Khan pursued a vigorous policy of expansion on Akbar's behalf. As soon as Akbar came of age, he began to free himself from the influences of overbearing ministers, court factions, and harem intrigues, and demonstrated his own capacity for judgment and leadership. A workaholic who seldom slept more than three hours a night, he personally oversaw the implementation of his administrative policies, which were to form the backbone of the Mughal Empire for more than 200 years. He continued to conquer, annex, and consolidate a far-flung territory bounded by Kabul in the northwest, Kashmir in the north, Bengal in the east, and beyond the Narmada River in central India.

Akbar built a walled capital called Fatehpur Sikri (Fatehpur means "town of victory") near Agra, starting in 1571. Palaces for each of Akbar's senior queens, a huge artificial lake, and sumptuous water-filled courtyards were built there. However, the city was soon abandoned and the capital was moved to Lahore in 1585. The reason may have been that the water supply in Fatehpur Sikri was insufficient or of poor quality; or, as some historians believe, that Akbar had to attend to the northwest areas of his empire and therefore moved his capital northwest. In 1599, Akbar shifted his capital back to Agra from where he reigned until his death.

Akbar adopted two distinct but effective approaches in administering a large territory and incorporating various ethnic groups into the service of his realm. In 1580 he obtained local revenue statistics for the previous decade in order to understand details of productivity and price fluctuation of different crops. Aided by Todar Mal, a Hindu scholar, Akbar issued a revenue schedule that optimised the revenue needs of the state with the ability of the peasantry to pay. Revenue demands, fixed according to local conventions of cultivation and quality of soil, ranged from one-third to one-half of the crop and were paid in cash. Akbar relied heavily on land-holding zamindars to act as revenue-collectors. They used their considerable local knowledge and influence to collect revenue and to transfer it to the treasury, keeping a portion in return for services rendered. Within his administrative system, the warrior aristocracy (mansabdars) held ranks (mansabs) expressed in numbers of troops, and indicating pay, armed contingents, and obligations. The warrior aristocracy was generally paid from revenues of nonhereditary and transferable jagirs (revenue villages).

An astute ruler who genuinely appreciated the challenges of administering so vast an empire, Akbar introduced a policy of reconciliation and assimilation of Hindus (including Jodhabai, later renamed Mariam-uz-Zamani <citation needed> Begum, the Hindu Rajput mother of his son and heir, Jahangir), who represented the majority of the population. He recruited and rewarded Hindu chiefs with the highest ranks in government; encouraged intermarriages between Mughal and Rajput aristocracy; allowed new temples to be built; personally participated in celebrating Hindu festivals such as Deepavali, or Diwali, the festival of lights; and abolished the jizya (poll tax) imposed on non-Muslims. Akbar came up with his own theory of "rulership as a divine illumination," enshrined in his new religion Din-i-Ilahi (Divine Faith), incorporating the principle of acceptance of all religions and sects. He encouraged widow re-marriage, discouraged child marriage, outlawed the practice of sati <citation needed>, and persuaded Delhi merchants to set up special market days for women, who otherwise were secluded at home.

By the end of Akbar's reign, the Mughal Empire extended throughout north India even south of the Narmada river. Notable exceptions were Gondwana in central India, which paid tribute to the Mughals, Assam in the northeast, and large parts of the Deccan. The area south of the Godavari river remained entirely out of the ambit of the Mughals. In 1600, Akbar's Mughal empire had a revenue of £17.5 million. By comparison, in 1800, the entire treasury of Great Britain totalled £16 million.

Akbar's empire supported vibrant intellectual and cultural life. The large imperial library included books in Hindi, Persian, Greek, Kashmiri, English, and Arabic, such as the Shahnameh, Bhagavata Purana and the Bible. Akbar regularly sponsored debates and dialogues among religious and intellectual figures with differing views, and he welcomed Jesuit missionaries from Goa to his court. Akbar directed the creation of the Hamzanama, an artistic masterpiece that included 1400 large paintings. Architecture flourished during the reign of Humayun's son Akbar. One of the first major building projects was the construction of a huge fort at Agra. The massive sandstone ramparts of the Red Fort are another impressive achievement. The most ambitious architectural exercise of Akbar, and one of the most glorious examples of Indo-Islamic architecture, was the creation of an entirely new capital city at Fatehpur Sikri.

Jahangir

After the death of Akbar in 1605, his son, Prince Salim, ascended the throne and assumed the title of Jahangir, "Seizer of the World". He was assisted in his artistic attempts by his able wife, Nur Jahan. The Mausoleum of Akbar at Sikandra, outside Agra, represents a major turning point in Mughal history, as the sandstone compositions of Akbar were adapted by his successors into opulent marble masterpieces. Jahangir is the central figure in the development of the Mughal garden. The most famous of his gardens is the Shalimar Bagh on the banks of Dal Lake in Kashmir.

Mughal rule under Jahangir (1605–27) and Shah Jahan (1628–58) was noted for political stability, brisk economic activity, beautiful paintings, and monumental buildings. Jahangir married a Persian princess whom he renamed Nur Jahan (Light of the World), who emerged as the most powerful individual in the court besides the emperor. As a result, Persian poets, artists, scholars, and officers — including her own family members — lured by the Mughal court's brilliance and luxury, found asylum in India. The number of unproductive officers mushroomed, as did corruption, while the excessive Persian representation upset the delicate balance of impartiality at the court. Jahangir liked Hindu festivals but promoted mass conversion to Islam; he persecuted the followers of Jainism and even executed Guru Arjun Dev, the fifth saint-teacher of the Sikhs in 1606 for refusing to make changes to the Guru Granth Sahib (the Sikh holy book).[citation needed] The execution was not entirely for religious reasons; Guru Arjun Dev supported Prince Khusro, another contestant to the Mughul throne in the civil war that developed after Akbar's death. Nur Jahan's abortive efforts to secure the throne for the prince of her choice led Shah Jahan to rebel against Jahangir in 1622. In that same year, the Persians took over Kandahar in southern Afghanistan, an event that struck a serious blow to Mughal prestige. Jahangir also had the Tuzak-i-Jahangiri composed as a record of his reign.

Shah Jahan

The Taj Mahal is the most famous monument built by the Mughals. It was built by Prince Khurram who ascended the throne in 1628 as Emperor Shah Jahan. Between 1636 and 1646, Shah Jahan sent Mughal armies to conquer the Deccan and the lands to the northwest of the empire, beyond the Khyber Pass. Even though they aptly demonstrated Mughal military strength, these campaigns drained the imperial treasury. As the state became a huge military machine, causing the nobles and their contingents to multiply almost fourfold, the demands for revenue from the peasantry were greatly increased. Political unification and maintenance of law and order over wide areas encouraged the emergence of large centers of commerce and crafts — such as Lahore, Delhi, Agra, and Ahmadabad — linked by roads and waterways to distant places and ports.

However, Shah Jahan's reign is remembered more for monumental architectural achievements than anything else. The single most important architectural change was the use of marble instead of sandstone. He demolished the austere sandstone structures of Akbar in the Red Fort and replaced them with marble buildings such as the Diwan-i-Am (hall of public audience) , the Diwan-i-Khas (hall of private audience), and the Moti Masjid (Pearl Mosque). The tomb of Itmiad-ud-Daula, the grandfather of his queen, Mumtaz Mahal, was also constructed on the opposite bank of the Jamuna or Yamuna. In 1638 he began to lay out the city of Shahjahanabad beside the Jamuna river further North in Delhi. The Red Fort at Delhi represents the pinnacle of centuries of experience in the construction of palace-forts. Outside the fort, he built the Jama Masjid, the largest mosque in India. However, it is for the Taj Mahal, which he built as a memorial to his beloved wife, Mumtaz Mahal, that he is most often remembered..

Shah Jahan's extravagant architectural indulgence had a heavy price. The peasants had been impoverished by heavy taxes and by the time his son Aurangzeb ascended the throne, the empire was in a state of insolvency. As a result, opportunities for grand architectural projects were severely limited. This is most easily seen at the Bibi-ki-Maqbara, the tomb of Aurangzeb's wife, built in 1678. Though the design was inspired by the Taj Mahal, it is half its size, the proportions compressed and the detail clumsily executed.

The Taj Mahal thus symbolizes both Mughal artistic achievement and excessive financial expenditures at a time when resources were shrinking. The economic positions of peasants and artisans did not improve because the administration failed to produce any lasting change in the existing social structure. There was no incentive for the revenue officials, whose concerns were primarily personal or familial gain, to generate resources independent of what was received from the Hindu zamindars and village leaders, who, due to self-interest and local dominance, did not hand over the entirety of the tax revenues to the imperial treasury. In their ever-greater dependence on land revenue, the Mughals unwittingly nurtured forces that eventually led to the break-up of their empire.

The Reign of Aurangzeb and the Decline of the Empire

The last of the great Mughals was Aurangzeb Alamgir. During his fifty-year reign, the empire reached its greatest physical size (the Bijapur and Golconda Sultanates which had been reduced to vassaldom by Shah Jahan were formally annexed), but also showed unmistakable signs of decline. The bureaucracy had grown corrupt; the huge army used outdated weaponry and tactics. Aurangzeb restored Mughal military dominance and expanded power southward, at least for a while. Aurangzeb was involved in a series of protracted wars: against the Pathans in Afghanistan, the sultans of Bijapur and Golkonda in the Deccan, against the Rajputs of Rajasthan, Malwa, and Bundelkhand, the Marathas in Maharashtra and the Ahoms in Assam. Peasant uprisings and revolts by local leaders became all too common, as did the conniving of the nobles to preserve their own status at the expense of a steadily weakening empire. From the early 1700s the campaigns of the Sikhs of Punjab under leaders such as Banda Bahadur, inspired by the martial teachings of their last Guru, Guru Gobind Singh, also posed a considerable threat to Mughal rule in Northern India.

The increasing association of Aurangzebs government with Islam further drove a wedge between the ruler and his Hindu subjects. Aurangzeb's policies towards his Hindu subjects was harsh, and intended to force them to convert. Temples were despoiled and the harsh "jiziya" tax (which non Muslims had to pay) was re-introduced. In this clime, contenders for the Mughal throne were many, and the reigns of Aurangzeb's successors were short-lived and filled with strife. The Mughal Empire experienced dramatic reverses as regional nawabs or governors broke away and founded independent kingdoms such as the Marathas in the south and the Sikhs in the north. In the war of 27 years from 1681 to 1707, the Mughals suffered several heavy defeats at the hands of the Marathas in the south. as well as this in the early 1700s the Sikhs of the north became increasingly militant in an attempt to fight the oppressive Mughal rule. They had to make peace with the Maratha armies, and Persian and Afghan armies invaded Delhi, carrying away many treasures, including the Peacock Throne in 1739.

The decline of the Mughal Empire has been studied under several different theories. Some historians such as Irfan Habib have described the decline of the Mughal Empire in terms of class struggle.[2] Habib proposed that excessive taxation and repression of peasants created a discontented class that either rebelled itself or supported rebellions by other classes and states. On the other hand, Athar Ali proposed a theory of a "jagirdari crisis." According to this theory, the influx of a large number of new Deccan nobles into the Mughal nobility during the reign of Aurangzeb created a shortage of agricultural crown land meant to be alloted, and destroyed the crown lands altogether.[3] The classical theory of Aurangzeb's Islamicism and Mughal decline continues to find a new life in the research of S. R. Sharma. Other theories put weight on the devious role played by the Saeed brothers in destabilizing the Mughal throne and auctioning the agricultural crown lands for revenue extraction.

The lesser mughals

- Bahadur Shah I (Shah Alam I), b. October 14, 1643 at Burhanpur, ruler 1707–12, d. February 1712 in Lahore.

- Jahandar Shah, b. 1664, ruler 1712–13, d. February 11, 1713 in Delhi.

- Furrukhsiyar, b. 1683, r. 1713–19, d. 1719 at Delhi.

- Rafi Ul-Darjat, ruler 1719, d. 1719 in Delhi.

- Rafi Ud-Daulat (Shah Jahan II), ruler 1719, d. 1719 in Delhi.

- Nikusiyar, ruler 1719, d. 1719 in Delhi.

- Mohammed Ibrahim, ruler 1720, d. 1720 in Delhi.

- Mohammed Shah, b. 1702, ruler 1719–48, d. April 26, 1748 in Delhi.

- Ahmad Shah Bahadur, b. 1725, ruler 1748–54, d. January 1775 in Delhi.

- Alamgir II, b. 1699, ruler 1754–59, d. 1759.

- Shah Jahan III, ruler 1760

- Shah Alam II, b. 1728, ruler 1759–1806, d. 1806.

- Akbar Shah II, b. 1760, ruler 1806–37, d. 1837.

- Bahadur Shah II aka Bahadur Shah Zafar, b. 1775 in Delhi, ruler from 1837–57, d. 1862 in exile in Rangoon, Burma.

Present-day descendants

A few descendants of the last Mughal Emperor, Bahadur Shah Zafar, are known to be living in Delhi, Kolkata (previously called Calcutta), and Hyderabad. Some of the direct descendants still identify themselves with the clan name Temur and with one of its four major branches: Shokohane-Temur (Shokoh), Shahane-Temur (Shah), Bakshane-Temur (Baksh) and Salatine-Temur (Sultan). Some direct descendants of the Mughals carry the surname of Mirza and Baig and are found predominantly in Pakistan particularly in Multan. There is some controversy surrounding the use of these surnames by imposters masquerading as descendants today. However, good genealogical records exist for most families in the subcontinent and are often consulted for establishing the authenticity of their claims.

Mughal influence on the subcontinent

The main mughal contribution to the south Asia was their unique architecture. Many monuments were built during the mughal era including the Taj Mahal. The first Mughal emperor Babur wrote in the Bāburnāma:

Hindustan is a place of little charm. There is no beauty in its people, no graceful social intercourse, no poetic talent or understanding, no etiquette, nobility or manliness. The arts and crafts have no harmony or symmetry. There are no good horses, meat, grapes, melons or other fruit. There is no ice, cold water, good food or bread in the markets. There are no baths and no madrasas. There are no candles, torches or candlesticks"[4].

Fortunately his successors, with fewer memories of the Central Asian homeland he pined for, took a less jaundiced view of Indian culture, and became more or less naturalised, absorbing many Indian traits and customs along the way. The Mughal period would see a more fruitful blending of Indian, Iranian and Central Asian artistic, intellectual and literary traditions than any other in Indian history. The Mughals had taste for the fine things in life - for beautifully designed artifacts and the enjoyment and appreciation of cultural activities. The Mughals borrowed as much as they gave - both the Hindu and Muslim traditions of India were huge influences on their interpretation of culture and court style. Nevertheless, they introduced many notable changes to Indian society and culture, including:

- Centralised government which brought together many smaller kingdoms

- Persian art and culture amalgamated with native Indian art and culture

- Started new trade routes to Arab and Turk lands, Islam was at its very high

- Mughali cuisine

- Urdu and spoken Hindi languages were formed for common Muslims and Hindus respectively

- A new style of architecture

- Landscape gardening

The remarkable flowering of art and architecture under the Mughals is due to several factors. The empire itself provided a secure framework within which artistic genius could flourish, and it commanded wealth and resources unparalleled in Indian history. The Mughal rulers themselves were extraordinary patrons of art, whose intellectual calibre and cultural outlook was expressed in the most refined taste.

Alternate meanings

- The alternate spelling of the empire, Mogul, is the source of the modern word mogul. In popular news jargon, this word denotes a successful business magnate who has built for himself a vast (and often monopolistic) empire in one or more specific industries. The usage is a reference to the expansive and wealthy empire built by the Mughal kings. Rupert Murdoch, for example, is a called a news mogul.

See also

- List of Mughal emperors

- Mughal era (part of the History of South Asia series)

- Muslim conquest in the Indian subcontinent

- List of wars in the Muslim world

- Turco-Persian/Turco-Mongol

- List of the Muslim Empires

- Islamic architecture

- Mughal painting

- Timurid dynasty

References

- ^ John F Richards, The Mughal Empire, Vol I.5 of the New Cambridge History of India, Cambridge University Press, 1996

- ^ Irfan Habib, The Agrarian System of Mughal India (Revised edition, Oxford University Press India, 2001) 317–51.

- ^ M. Athar Ali, The Mughal nobility under Aurangzeb. Revised ed. (Delhi: Oxford University Press. 1997) 11.

- ^ The Baburnama Ed. & Trans. Wheeler M. Thackston (New York) 2002 p. 352

External links

- Mughal India an interactive experience from the British Museum

- The Mughal Empire from BBC

- Mughal Empire

- The Great Mughals

- Gardens of the Mughal Empire

- Indo-Iranian Socio-Cultural Relations at Past, Present and Future, by M.Reza Pourjafar, Ali

- A. Taghvaee, in Web Journal on Cultural Patrimony (Fabio Maniscalco ed.), vol. 1, January–June 2006

- Adrian Fletcher's Paradoxplace — PHOTOS — Great Mughal Emperors of India

This article may be in need of reorganization to comply with Wikipedia's layout guidelines. (February 2007) |