Pan-Germanism: Difference between revisions

| Line 53: | Line 53: | ||

World war I became the first attempt to carry out the Pan-German ideology in practice, and the Pan-German movement argued forcefully for an expansionist imperialism providing the German people with [[lebensraum]].<ref name=Blamires>World fascism: a historical encyclopedia, Volume 1 Cyprian Blamires ABC-CLIO, 2006. pp. 499-501</ref> |

World war I became the first attempt to carry out the Pan-German ideology in practice, and the Pan-German movement argued forcefully for an expansionist imperialism providing the German people with [[lebensraum]].<ref name=Blamires>World fascism: a historical encyclopedia, Volume 1 Cyprian Blamires ABC-CLIO, 2006. pp. 499-501</ref> |

||

Following the defeat in [[World War I]], influence of German-speaking elites over [[Central Europe|Central]] and [[Eastern Europe]] was greatly limited. At the [[Treaty of Versailles]] Germany was substantially reduced in size. [[Austria-Hungary]] was split up. A Rump-Austria, which to a certain extent corresponded to the [[Austria-Hungary#Linguistic_distribution|German-speaking areas of Austria-Hungary]] (a complete split into language groups was impossible due to multi-lingual areas and language-exclaves) adopted the name "[[German Austria]]" ({{lang-de|Deutschösterreich}}) in hope for union with [[ |

Following the defeat in [[World War I]], influence of German-speaking elites over [[Central Europe|Central]] and [[Eastern Europe]] was greatly limited. At the [[Treaty of Versailles]] Germany was substantially reduced in size. [[Austria-Hungary]] was split up. A Rump-Austria, which to a certain extent corresponded to the [[Austria-Hungary#Linguistic_distribution|German-speaking areas of Austria-Hungary]] (a complete split into language groups was impossible due to multi-lingual areas and language-exclaves) adopted the name "[[German Austria]]" ({{lang-de|Deutschösterreich}}) in hope for union with [[Weimar_Republic|Germany]]. Union with Germany and the name German Austria was forbid by the [[Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye (1919)|Treaty of St Germain]] and had to be changed back to Austria. |

||

It was in the post-World War I period that [[Adolf Hitler]] under the influence of the [[Dolchstosslegende]], first took up Pan-German ideas in his [[Mein Kampf]].<ref name="Blamires"/> He met [[Heinrich Class]] in 1918, and Class provided Hitler with support for the 1923 [[Beer Hall Putsch]]. Hitler and his national socialists shared most of the basic Pan-German visions with the Pan-German league, but nonetheless differences in political style lead the two groups to open rivalry. The [[German Workers Party of Bohemia]] cut its ties to the Pan-German movement which was seen as being too dominated by the upper classes and joined forces with the [[German Workers Party]] lead by [[Anton Drexler]] which later became The [[National Socialist German Workers Party]], lead by Adolf Hitler.<ref name="Levy2">Antisemitism: a historical encyclopedia of prejudice and persecution, Volume 1 Richard S. Levy, 529-530, ABC-CLIO 2005</ref> The ''[[Heim ins Reich]]'' initiative ([[German language|German]]: literally ''Home into the Empire'', meaning ''Back to Reich'', see [[Reich]]) was a policy pursued by [[Nazi Germany]] which attempted to convince people of [[ethnic Germans|German descent]] living outside of [[Germany]] (such as [[Sudetenland]]) that they should strive to bring these regions "home" into a [[Kleindeutschland_and_Großdeutschland#Later_influence|Greater Germany]]. |

It was in the post-World War I period that [[Adolf Hitler]] under the influence of the [[Dolchstosslegende]], first took up Pan-German ideas in his [[Mein Kampf]].<ref name="Blamires"/> He met [[Heinrich Class]] in 1918, and Class provided Hitler with support for the 1923 [[Beer Hall Putsch]]. Hitler and his national socialists shared most of the basic Pan-German visions with the Pan-German league, but nonetheless differences in political style lead the two groups to open rivalry. The [[German Workers Party of Bohemia]] cut its ties to the Pan-German movement which was seen as being too dominated by the upper classes and joined forces with the [[German Workers Party]] lead by [[Anton Drexler]] which later became The [[National Socialist German Workers Party]], lead by Adolf Hitler.<ref name="Levy2">Antisemitism: a historical encyclopedia of prejudice and persecution, Volume 1 Richard S. Levy, 529-530, ABC-CLIO 2005</ref> The ''[[Heim ins Reich]]'' initiative ([[German language|German]]: literally ''Home into the Empire'', meaning ''Back to Reich'', see [[Reich]]) was a policy pursued by [[Nazi Germany]] which attempted to convince people of [[ethnic Germans|German descent]] living outside of [[Germany]] (such as [[Sudetenland]]) that they should strive to bring these regions "home" into a [[Kleindeutschland_and_Großdeutschland#Later_influence|Greater Germany]]. |

||

Revision as of 08:59, 13 October 2011

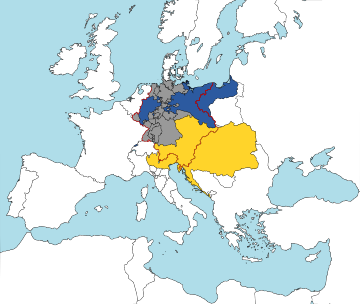

Pan-Germanism ([Pangermanismus or Alldeutsche Bewegung] Error: {{Lang-xx}}: text has italic markup (help)) is a pan-nationalist political idea. Pan-Germanists originally sought to unify the German-speaking populations of Europe in a single nation-state known as Großdeutschland (Greater Germany), where "German-speaking" was taken to include the Low German, Frisian and Dutch-speaking populations of the Low Countries, and sometimes also as synonymous with Germanic-speaking, to the inclusion of Scandinavia.

Pan-Germanism was highly influential in German politics in the 19th century and the first half of the 20th century. From the late 19th century, many Pan-Germanist thinkers, since 1891 organized in the Pan-German League, had adopted openly ethnocentric and racist ideologies, and ultimately gave rise to the Heim ins Reich policy pursued by Nazi Germany under Adolf Hitler from 1938, one of the primary factors leading to the outbreak of World War II.[1][2][3][4] As a result of the disaster of World War II, Pan-Germanism has been taboo as an ideology in the postwar period in both the Federal Republic of Germany and the German Democratic Republic, as well as the Republic of Austria, and even the reunification of Germany in 1990 was viewed with some suspicion. Pan-Germanism remains practically extinct as an ideology, at best limited to some fringe groups of Neo-Nazism in Germany and Austria.

Origins (before 1860)

Pan-Germanism's origins began with the birth of Romantic nationalism during the Napoleonic Wars, with Friedrich Ludwig Jahn and Ernst Moritz Arndt being early proponents. Germans, for the most part, had been a loose and disunited people since the Reformation, when the Holy Roman Empire was shattered into a patchwork of states following the end of the Thirty Year's War with the Peace of Westphalia.

Advocates of the Großdeutschland (Greater Germany) solution sought to unite all the German-speaking people in Europe, including the Germans of the Austrian Empire, while others also advocated the inclusion of the Scandinavians and the Dutch. Pan-Germanism was widespread among the revolutionaries of 1848, notably among Richard Wagner and the Brothers Grimm.[3] Writers such as Friedrich List and Paul Anton Lagarde argued for German hegemony in Central and Eastern Europe, where German domination in some areas had begun as early as the 9th century AD with the Ostsiedlung, germanic expansion into Slavic and Baltic lands. For the Pan-Germanists this movement was seen as a Drang Nach Osten, in which Germans would be naturally inclined to seek Lebensraum by moving eastwards to reunite with the German minorities there.

The Deutschlandlied ("Song of Germany"), written in 1841 by Hoffmann von Fallersleben, in its first stanza defines Deutschland as reaching " From the Meuse to the Memel / From the Adige to the Belt", i.e. as including East Prussia and South Tyrol.

The German question

By the 1860s the Kingdom of Prussia and the Austrian Empire were the two most powerful nations dominated by German-speaking elites. Both sought to expand their influence and territory. The Austrian Empire — like the Holy Roman Empire — was a multi-ethnic state, but German-speaking people there did not have an absolute numerical majority; the creation of the Austro-Hungarian Empire was one result of the growing nationalism of other ethnicities especially the Hungarians. Prussia under Otto von Bismarck would ride on the coat-tails of nationalism to unite all of modern-day Germany. With the Unification of Germany, the German Empire ("Second Reich") was created in 1871 following the proclamation of Wilhelm I as head of a union of German-speaking states, while disregarding millions of its non-German subjects who desired self-determination from German rule.

There was also a rejection of Roman Catholicism with the Away from Rome! movement calling for German speakers to identify with Lutheran or Old Catholic churches.[4]

German nationalism in Austria

After the Revolutions of 1848/49, in which the liberal nationalistic revolutionaries advocated the Greater German solution, the Austrian defeat in the Austro-Prussian War (1866) with the effect that Austria was practically edged out of Germany, and increasing ethnic conflicts in the multinational Habsburg Monarchy, a German national movement evolved in Austria. Led by the radical German nationalist and anti-semite Georg von Schönerer, organisations as the Pan-German Society demanded the link-up of all German-speaking territories of the Danube Monarchy to the German Empire, and decidedly rejected Austrian patriotism. Schönerer's völkisch and racist German nationalism was an inspiration to Hitler's ideology. In 1933, Austrian Nazis and the national-liberal Greater German People's Party formed an action group, fighting together against the Austrofascist regime which imposed a distinct Austrian national identity. With the "Anschluss" of Austria in 1938, the historic aim of Austria's German nationalists was achieved. After 1945, the German national camp was revived in the Federation of Independents and the Freedom Party of Austria.

Pan-German League

The Pan-German Movement was officially founded in 1891, when Ernst Hasse, a professor at the University of Leipzig and a member of the Reichstag, who organized the Pan-German League an ultra-nationalist[5] political interest organization which promoted imperialism, anti-semitism, and support for Ethnic German minorites in other countries.[6] The organization achieved great support among the educated middle and upper class, the organization promoted German nationalist consciousness, especially among Ethnic Germans outside Germany. In his three-volume work, Deutsche Politik (1905–07), Hasse called for German imperialist expansion in Europe. Similar expansionist policies were preached by Munich professor Karl Haushofer, Ewald Banse, and Hans Grimm, author of Volk ohne Raum and his brother Jacob who published a treaty about German "volksrecht". Georg Schönerer and Karl Hermann Wolf articulated Pan-Germanist sentiments in Austria-Hungary.[1]

The position of Pan-German league gradually evolved[clarification needed] into biological racism, with belief that Germans are "superior race", and Germans need protection from mixing with other races, particularly Jews. By 1912 in publication "If I were the Keiser", the Pan-German League's leading member Heinrich Class called on Germans to conquer Eastern territories inhabited by "inferior" Slavs, depopulate their territories and settle German colonists there.[6]

Pan-Germanism in Scandinavia

Pan-Germanic tendencies were also widespread among the Norwegian independence movement, notably proposed by Peter Andreas Munch, and Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson. Also prominent cultural personalities like Knut Hamsun and Henrik Ibsen expressed sympathy for the Pan-German idea.[3][7] Bjørnson, who wrote the lyrics for the Norwegian national anthem, proclaimed in 1901:

I'm a Pan-Germanist, I'm a Teuton, and my greatest dream is for the Northern Germans and the Western Germans to unite in a fellow Confederation.

— Bjørnson, [3]

Jacob Grimm adopted Munch's anti-Danish Pan-Germanism and argued that the entire Peninsula of Jutland had been populated by Germans in before the arrival of the Danes and that there it could justifiably be reclaimed by Germany, whereas the rest of Denmark should be incorporated into Sweden. This line of thinking was countered by Jens Jacob Asmussen Worsaae, an archaeologist who had excavated parts of Danevirke, who argued that there was no way of knowing the language of the earliest inhabitants of Danish territory, that Germans had more solid historical claims to large parts of France and England, and that Slavs by the same reasoning could annex parts of Eastern Germany. Regardless of the strength of Worsaae's arguments pan-Germanism spurred on the German nationalists of Schleswig and Holstein and lead to the First Schleswig War in 1848. Which likely in turn contributed to the fact that Pan-Germanism never caught on in Denmark as much as it did in Norway.[8]

1918 to 1945

World war I became the first attempt to carry out the Pan-German ideology in practice, and the Pan-German movement argued forcefully for an expansionist imperialism providing the German people with lebensraum.[9]

Following the defeat in World War I, influence of German-speaking elites over Central and Eastern Europe was greatly limited. At the Treaty of Versailles Germany was substantially reduced in size. Austria-Hungary was split up. A Rump-Austria, which to a certain extent corresponded to the German-speaking areas of Austria-Hungary (a complete split into language groups was impossible due to multi-lingual areas and language-exclaves) adopted the name "German Austria" (German: Deutschösterreich) in hope for union with Germany. Union with Germany and the name German Austria was forbid by the Treaty of St Germain and had to be changed back to Austria.

It was in the post-World War I period that Adolf Hitler under the influence of the Dolchstosslegende, first took up Pan-German ideas in his Mein Kampf.[9] He met Heinrich Class in 1918, and Class provided Hitler with support for the 1923 Beer Hall Putsch. Hitler and his national socialists shared most of the basic Pan-German visions with the Pan-German league, but nonetheless differences in political style lead the two groups to open rivalry. The German Workers Party of Bohemia cut its ties to the Pan-German movement which was seen as being too dominated by the upper classes and joined forces with the German Workers Party lead by Anton Drexler which later became The National Socialist German Workers Party, lead by Adolf Hitler.[10] The Heim ins Reich initiative (German: literally Home into the Empire, meaning Back to Reich, see Reich) was a policy pursued by Nazi Germany which attempted to convince people of German descent living outside of Germany (such as Sudetenland) that they should strive to bring these regions "home" into a Greater Germany.

History since 1945

World War II brought about the decline of Pan-Germanism, much as World War I had led to the demise of Pan-Slavism. Parts of Germany itself were devastated, and the country was divided, firstly into Soviet, French, American, and British zones and then into West Germany and East Germany. To add to the disaster, Germany suffered even larger territorial losses than it did in the First World War, with huge portions of eastern Germany directly annexed by the Soviet Union and Poland. The scale of the Germans' defeat was unprecedented. Nationalism and Pan-Germanism became almost taboo because they had been used so destructively by the Nazis. Indeed, the word "Volksdeutscher" in reference to ethnic Germans naturalized during World War II later developed into a mild epithet. However, reunification of Germany in 1990 revived the old debates.[11]

See also

References

- ^ a b http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/440618/Pan-Germanism

- ^ Origins and Political Character of Nazi Ideology Hajo Holborn Political Science Quarterly Vol. 79, No. 4 (Dec., 1964), p.550

- ^ a b c d http://www.dagbladet.no/2009/05/07/magasinet/litteratur/historie/5961478/

- ^ a b Mees, Bernard (2008). The Science of the Swastika. Central European University Press. ISBN 978-9639776180.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Eric J. Hobsbawm (1987). The age of empire, 1875-1914. Pantheon Books. p. 152. ISBN 9780394563190. Retrieved 22 March 2011.

- ^ a b Antisemitism: a historical encyclopedia of prejudice and persecution, Volume 1 Richard S. Levy, 528-529,ABC-CLIO 2005

- ^ http://www.nrk.no/programmer/tv_arkiv/drommen_om_norge/4439099.html

- ^ Rowly-Conwy, Peter. "THE CONCEPT OF PREHISTORY AND THE INVENTION OF THE TERMS 'PREHISTORIC' AND 'PREHISTORIAN': THE SCANDINAVIAN ORIGIN, 1833–1850". European Journal of Archaeology. 9 (1): 103–130.

- ^ a b World fascism: a historical encyclopedia, Volume 1 Cyprian Blamires ABC-CLIO, 2006. pp. 499-501

- ^ Antisemitism: a historical encyclopedia of prejudice and persecution, Volume 1 Richard S. Levy, 529-530, ABC-CLIO 2005

- ^ Zeilinger, Gerhard (16 June 2011). "Straches "neue" Heimat und der Boulevardsozialismus". Der Standard (in German). Retrieved 28 June 2011.

Further reading

- Jackisch, Barry Andrew. ‘Not a Large, but a Strong Right’: The Pan-German League, Radical Nationalism, and Rightist Party Politics in Weimar Germany, 1918-1939. Bell and Howell Information and Learning Company: Ann Arbor. 2000.

- Wertheimer, Mildred. The Pan-German League, 1890-1914. Columbia University Press: New York. 1924.

- Chickering, Roger. We Men Who Feel Most German: Cultural Study of the Pan-German League, 1886-1914. Harper Collins Publishers Ltd. 1984.