European debt crisis: Difference between revisions

added "citation needed" + A call on user "194.210.226.97": the burden is on you to provide a source. |

m Changed "borrower" of [foreign] capital to "importer" as not all capital is borrowed (equity, FDI, asset disposals etc.) |

||

| Line 53: | Line 53: | ||

</ref> |

</ref> |

||

Germany's positive balance of payments (trade surplus) has increased as a percentage of GDP since 1999, while the negative balance of payments (trade deficits) of Italy, France and Spain have worsened. Greece's imports-to-exports ratio has gotten better between 2010 and 2011;<ref name="Elstat Trade">{{cite web |url=http://www.statistics.gr/portal/page/portal/ESYE/BUCKET/A0902/PressReleases/A0902_SFC02_DT_MM_10_2011_01_E_EN.pdf |title=COMMERCIAL TRANSACTIONS OF GREECE (Estimations) : October 2011 |date=9 December 2011 |work=[[Hellenic Statistical Authority]] |publisher=www.statistics.gr |accessdate=8 December 2011}}</ref> in the period November 2010 to October 2011 its imports dropped by 12.3% while its exports grew by 15.2% (40.7% to non-EU countries in comparison to October 2010).<ref name="Elstat Trade" /> It is a mathematical identity (a rule that must hold true by definition) that a country with a trade deficit must be a net |

Germany's positive balance of payments (trade surplus) has increased as a percentage of GDP since 1999, while the negative balance of payments (trade deficits) of Italy, France and Spain have worsened. Greece's imports-to-exports ratio has gotten better between 2010 and 2011;<ref name="Elstat Trade">{{cite web |url=http://www.statistics.gr/portal/page/portal/ESYE/BUCKET/A0902/PressReleases/A0902_SFC02_DT_MM_10_2011_01_E_EN.pdf |title=COMMERCIAL TRANSACTIONS OF GREECE (Estimations) : October 2011 |date=9 December 2011 |work=[[Hellenic Statistical Authority]] |publisher=www.statistics.gr |accessdate=8 December 2011}}</ref> in the period November 2010 to October 2011 its imports dropped by 12.3% while its exports grew by 15.2% (40.7% to non-EU countries in comparison to October 2010).<ref name="Elstat Trade" /> It is a mathematical identity (a rule that must hold true by definition) that a country with a trade deficit must be a net importer of capital to fund the deficit.<ref>[http://www.nytimes.com/2011/04/23/business/global/23charts.html?_r=1&smid=tw-nytimesbusiness&seid=auto NYT-Floyd Norris-Euro Benefits Germany More Than Others in Zone-April 2011 ]</ref> |

||

===Monetary policy inflexibility=== |

===Monetary policy inflexibility=== |

||

Revision as of 08:01, 20 January 2012

This article may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. (January 2012) |

| Part of a series on the |

| Great Recession |

|---|

| Timeline |

From late 2009, fears of a sovereign debt crisis developed among investors concerning rising government debt levels across the globe together with a wave of downgrading of government debt of certain European states. Concerns intensified early 2010 and thereafter[3][4] making it difficult or impossible for Greece, Ireland and Portugal to re-finance their debts. On 9 May 2010, Europe's Finance Ministers approved a rescue package worth €750 billion aimed at ensuring financial stability across Europe by creating the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF).[5] In October 2011 eurozone leaders agreed on another package of measures designed to prevent the collapse of member economies. This included an agreement with banks to accept a 50% write-off of Greek debt owed to private creditors,[6][7] increasing the EFSF to about €1 trillion, and requiring European banks to achieve 9% capitalisation.[8] To restore confidence in Europe, EU leaders also suggested to create a common fiscal union across the eurozone with strict and enforceable rules embedded in the EU treaties.[9][10]

While the sovereign debt increases have been most pronounced in only a few eurozone countries, they have become a perceived problem for the area as a whole.[11] Nevertheless, the European currency has remained stable.[12] As of mid-November 2011 it was trading even slightly higher against the Euro bloc's major trading partners than at the beginning of the crisis.[13][14] The three most affected countries, Greece, Ireland and Portugal, collectively account for six percent of eurozone's gross domestic product (GDP).[15]

Causes

The European sovereign debt crisis has been created by a combination of complex factors such as: the globalization of finance; easy credit conditions during the 2002-2008 period that encouraged high-risk lending and borrowing practices; international trade imbalances; real-estate bubbles that have since burst; slow growth economic conditions 2008 and after; fiscal policy choices related to government revenues and expenses; and approaches used by nations to bailout troubled banking industries and private bondholders, assuming private debt burdens or socializing losses.[16][17]

One narrative describing the causes of the crisis begins with the significant increase in savings available for investment during the 2000-2007 period. During this time, the global pool of fixed income securities increased from approximately $36 trillion in 2000 to $70 trillion by 2007. This "Giant Pool of Money" increased as savings from high-growth developing nations entered global capital markets. Investors searching for higher yields than those offered by U.S. Treasury bonds sought alternatives globally.[18] The temptation offered by this readily available savings overwhelmed the policy and regulatory control mechanisms in country after country as global fixed income investors searched for yield, generating bubble after bubble across the globe. While these bubbles have burst causing asset prices (e.g., housing and commercial property) to decline, the liabilities owed to global investors remain at full price, generating questions regarding the solvency of governments and their banking systems.[17]

How each European country involved in this crisis borrowed and invested the money varies. For example, Ireland's banks lent the money to property developers, generating a massive property bubble. When the bubble burst, Ireland's government and taxpayers assumed private debts. In Greece, the government increased its commitments to public workers in the form of extremely generous pay and pension benefits. Iceland's banking system grew enormously, creating debts to global investors ("external debts") several times larger than its national GDP.[17]

The interconnection in the global financial system means that if one nation defaults on its sovereign debt or enters into recession that places some of the external private debt at risk as well, the banking systems of creditor nations face losses. For example, in October 2011 Italian borrowers owed French banks $366 billion (net). Should Italy be unable to finance itself, the French banking system and economy could come under significant pressure, which in turn would affect France's creditors and so on. This is referred to as financial contagion.[19][20] Further creating interconnection is the concept of debt protection. Financial institutions enter into contracts called credit default swaps (CDS) that result in payment or receipt of funds should default occur on a particular debt instrument or security, such as a government bond. Since multiple CDS can be purchased on the same security, the value of money changing hands can be many times larger than the amount of debt itself. It is unclear what exposure each country's banking system has to CDS, which creates another type of uncertainty.[21]

Some politicians, notably Angela Merkel, have sought to attribute some of the blame for the crisis to hedge funds and other speculators stating that "institutions bailed out with public funds are exploiting the budget crisis in Greece and elsewhere".[22][23][24][25][26] Although some financial institutions clearly profited from the growing Greek government debt in the short run,[27] there was a long lead up to the crisis.

Rising government debt levels

In 1992 members of the European Union signed the Maastricht Treaty, under which they pledged to limit their deficit spending and debt levels. However, a number of EU member states, including Greece and Italy, were able to circumvent these rules and mask their deficit and debt levels through the use of complex currency and credit derivatives structures.[28][29] The structures were designed by prominent U.S. investment banks, who received substantial fees in return for their services and who took on little credit risk themselves thanks to special legal protections for derivatives counterparties.[28]

A number of "appalled economists" have condemned the popular notion in the media that rising debt levels of European countries were caused by excess government spending. According to their analysis increased debt levels are due to the large bailout packages provided to the financial sector during the late-2000s financial crisis, and the global economic slowdown thereafter. The average fiscal deficit in the euro area in 2007 was only 0.6% before it grew to 7% during the financial crisis. In the same period the average government debt rose from 66% to 84% of GDP. The authors also stressed that fiscal deficits in the euro area were stable or even shrinking since the early 1990s.[30]

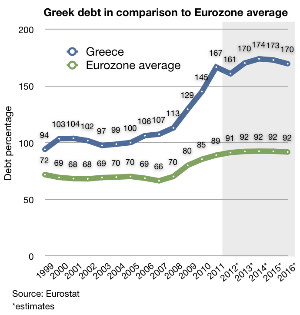

Either way, high debt levels alone may not explain the crisis. According to The Economist Intelligence Unit, the position of the euro area looked "no worse and in some respects, rather better than that of the US or the UK." The budget deficit for the euro area as a whole (see graph) is much lower and the euro area's government debt/GDP ratio of 86% in 2010 was about the same level as that of the US. Moreover, private-sector indebtedness across the euro area is markedly lower than in the highly leveraged Anglo-Saxon economies.[31]

Trade imbalances

Commentators such as Financial Times journalist Martin Wolf have asserted the root cause of the crisis is imbalances on the balance of payments. He notes that in the run to the crises from 1999–2007, Germany had a considerably better public debt and fiscal deficit relative to GDP than some of the worse affected Eurozone members like Spain and Ireland. Whereas in the same period, all the worse affected major countries (Portugal, Ireland, Italy and Spain) had a far worse balance of payments position than Germany.[32]

Germany's positive balance of payments (trade surplus) has increased as a percentage of GDP since 1999, while the negative balance of payments (trade deficits) of Italy, France and Spain have worsened. Greece's imports-to-exports ratio has gotten better between 2010 and 2011;[33] in the period November 2010 to October 2011 its imports dropped by 12.3% while its exports grew by 15.2% (40.7% to non-EU countries in comparison to October 2010).[33] It is a mathematical identity (a rule that must hold true by definition) that a country with a trade deficit must be a net importer of capital to fund the deficit.[34]

Monetary policy inflexibility

Since Eurozone countries are not able to conduct their own monetary policy, they have a higher default risk than countries that can. For example, the British government can "print money" to pay creditors to reduce the risk of default, while Eurozone countries like France cannot. In addition, when a country "prints money" it devalues its currency relative to its trading partners, which makes its exports cheaper, thereby increasing GDP and tax revenue while reducing its trade deficit.[35] For example, by the end of 2011 anyone who has lent money to Britain has suffered an approximate 30% cut in the repayment value of the debt following a 25% fall in the rate of exchange and 5% rise in inflation.[36]

Loss of confidence

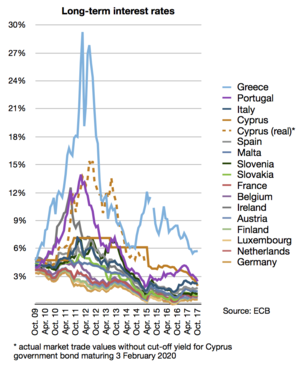

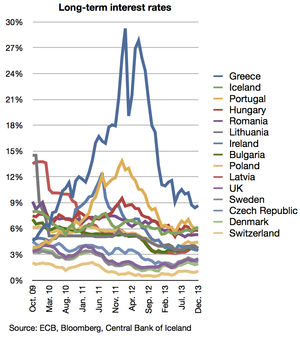

Prior to development of the crisis it was assumed by both regulators and banks that sovereign debt from the Euro zone was safe. Banks had substantial holdings of bonds from weaker economies such as Greece which offered a small premium and seemingly were equally sound. As the crisis developed it became obvious that Greek, and possibly other countries', bonds offered substantially more risk. Contributing to lack of information about the risk of European sovereign debt was conflict of interest by banks that were earning substantial sums underwriting the bonds.[37] The loss of confidence is marked by rising sovereign CDS prices, indicating market expectations about countries' creditworthiness (see graph).

Furthermore, investors have doubts about the possibilities of policy makers to quickly contain the crisis. Since countries that use the Euro as their currency have fewer monetary policy choices (e.g., they cannot print money in their own currencies to pay debt holders), certain solutions require multi-national cooperation. Further, the European Central Bank has an inflation control mandate but not an employment mandate, as opposed to the U.S. Federal Reserve, which has a dual mandate. According to the Economist, the crisis "is as much political as economic" and the result of the fact that the euro area is not supported by the institutional paraphernalia (and mutual bonds of solidarity) of a state.[31]

- Rating agency views

S&P placed its long-term sovereign ratings on 15 members of the European Economic and Monetary Union (EMU or eurozone) on "CreditWatch" with negative implications on December 5, 2011. S&P wrote this was due to "systemic stresses from five interrelated factors: 1) Tightening credit conditions across the eurozone; 2) Markedly higher risk premiums on a growing number of eurozone sovereigns including some that are currently rated 'AAA'; 3) Continuing disagreements among European policy makers on how to tackle the immediate market confidence crisis and, longer term, how to ensure greater economic, financial, and fiscal convergence among eurozone members; 4) High levels of government and household indebtedness across a large area of the eurozone; and 5) The rising risk of economic recession in the eurozone as a whole in 2012. Currently, we expect output to decline next year in countries such as Spain, Portugal and Greece, but we now assign a 40% probability of a fall in output for the eurozone as a whole."[38]

Evolution of the crisis

In the first weeks of 2010, there was renewed anxiety about excessive national debt. Frightened investors demanded higher interest rates from several governments with higher debt levels or deficits. This in turn makes it difficult for governments to finance further budget deficits and service existing high debt levels. Elected officials have focused on austerity measures (e.g., higher taxes and lower expenses) contributing to social unrest and significant debate among economists, many of whom advocate greater deficits when economies are struggling. Especially in countries where government budget deficits and sovereign debts have increased sharply, a crisis of confidence has emerged with the widening of bond yield spreads and risk insurance on CDS between these countries and other EU member states, most importantly Germany.[39][40] By the end of 2011, Germany was estimated to have made more than €9 billion out of the crisis as investors flock to safer but near zero interest rate bunds.[41] While Switzerland equally benefited from lower interest rates the crisis also harmed its exporting sector due to a substantial influx of foreign capital and the resulting rise of the Swiss Franc. In September 2011 the Swiss National Bank surprised currency traders by pledging that "it will no longer tolerate a euro-franc exchange rate below the minimum rate of 1.20 francs", effectively weakening the Swiss franc.This is the biggest Swiss intervention since 1978.[42]

Greece

In the early-mid 2000s, Greece's economy was strong and the government took advantage by running a large deficit, partly due to high defense spending amid historic enmity to Turkey. As the world economy cooled in the late 2000s, Greece was hit especially hard because its main industries—shipping and tourism—were especially sensitive to changes in the business cycle. As a result, the country's debt began to pile up rapidly. In early 2010, as concerns about Greece's national debt grew, policy makers suggested that emergency bailouts might be necessary. EU politicians in Brussels have long turned a blind eye and gave Greece a fairly clean bill of health, even as the reality of economics suggested the Euro was in danger.

On 23 April 2010, the Greek government requested that the EU/IMF bailout package (made of relatively high-interest loans) be activated.[43] The IMF had said it was "prepared to move expeditiously on this request". The initial size of the loan package was €45 billion ($61 billion) and its first installment covered €8.5 billion of Greek bonds that became due for repayment.[44]

On 27 April 2010, Standard & Poor's slashed Greece's sovereign debt rating to BB+ or "junk" status amid fears of default.[45][46] The yield of the Greek two-year bond reached 15.3% in the secondary market.[47] Standard & Poor's estimates that, in the event of default, investors would lose 30–50% of their money.[45] Stock markets worldwide and the Euro currency declined in response to this announcement.[48]

On 1 May 2010, a series of austerity measures was proposed.[49] The proposal helped persuade Germany, the last remaining holdout, to sign on to a larger, €110 billion EU/IMF loan package over three years for Greece (retaining a relatively high interest of 5% for the main part of the loans, provided by the EU).[50] On 5 May 2010, a national strike was held in opposition to the planned spending cuts and tax increases. Protest on that date was widespread and turned violent in Athens, killing three people.[50]

On 2 May 2010, the Eurozone countries and the International Monetary Fund agreed to a €110 billion loan for Greece, conditional on the implementation of harsh austerity measures. The Greek bail-out was followed by a €85 billion rescue package for Ireland in November, a €78 billion bail-out for Portugal in May 2011, then continuing efforts to meet the continuing crisis in Greece and other countries. Nevertheless, credit rating agencies downgraded Greek governmental bonds to junk status. This was followed by an announcement of the ECB on 3 May that it will still accept as collateral all outstanding and new debt instruments issued or guaranteed by the Greek government, regardless of the nation's credit rating.[51]

The November 2010 revisions of 2009 deficit and debt levels made accomplishment of the 2010 targets even harder, and indications signal a recession harsher than originally feared.[52]

Japan, Italy and Belgium's creditors are mainly domestic institutions, but Greece and Portugal have a higher percent of their debt in the hands of foreign creditors, which is seen by certain analysts as more difficult to sustain. Greece, Portugal, and Spain have a 'credibility problem', because they lack the ability to repay adequately due to their low growth rate, high deficit, less FDI, etc.[53]

In May 2011, Greek public debt gained prominence as a matter of concern.[54] The Greek people generally reject the austerity measures, and have expressed their dissatisfaction through angry street protests. In late June 2011, Greece's government proposed additional spending cuts worth €28 billion (£25bn) over five years. The next 12 billion euros from the Eurozone bail-out package will be released when the proposal is passed, without which Greece would have had to default on loan repayments due in mid-July.[55]

On 13 June 2011, Standard and Poor's downgraded Greece's sovereign debt rating to CCC, the lowest in the world, following the findings of a bilateral EU-IMF audit which called for further austerity measures.[56] After the major political parties failed to reach consensus on the necessary measures to qualify for a further bailout package, and amidst riots and a general strike, Prime Minister George Papandreou proposed a re-shuffled cabinet, and asked for a vote of confidence in the parliament.[57][58] The crisis sent ripples around the world, with major stock exchanges exhibiting losses.[59]

Greece’s first adjustment plan was launched in March 2010 with €80 billion in support from the European governments and €30 billion from the IMF. This adjustment program hoped to reestablish the access to private capital markets by 2012. However it was soon found that this process would take longer than expected. In July 2011 there was a new package instilled in which an extra €109 billion in support of Greece which included a large privatization effort. Some believe that this will cause more debt for Greece. With this new package it is projected that there will be a 3.8% decline in 2011 but a .6% growth in 2012, following with a 3.5% increase in 2013, where it will eventually plateau in 2015 at 6.4%.[citation needed]

Some experts argue the best option for Greece and the rest of the EU should be to engineer an “orderly default” on Greece’s public debt which would allow Athens to withdraw simultaneously from the eurozone and reintroduce its national currency the drachma at a debased rate.[60][61] Economists who favor this approach to solve the Greek debt crisis typically argue that a delay in organising an orderly default would wind up hurting EU lenders and neighboring European countries even more.[62]

At an extraordinary summit on 21 July 2011 in Brussels the euro area leaders agreed to lower the interest rates of EU loans to Greece to 3.5%.[63] In the early hours of 27 October 2011, Eurozone leaders and the IMF came to an agreement with banks to accept a 50% write-off of (some part of) Greek debt,[6][7][64] the equivalent of €100 billion.[6] The aim of the haircut is to reduce Greece's debt to 120% of GDP by 2020.[6][65][66]

On 7 December 2011, the new interim national union government led by Lucas Papademos submitted its plans for the 2012 budget, promising to cut its deficit from 9% of GDP 2011 to 5.4% in 2012, mostly due to a write-off of debt held by banks. Excluding interest payments, Greece even expects a primary surplus in 2012 of 1.1%.[67]

Ireland

The Irish sovereign debt crisis was not based on government over-spending, but from the state guaranteeing the six main Irish-based banks who had financed a property bubble. On 29 September 2008 the Finance Minister Brian Lenihan, Jnr issued a one-year guarantee to the banks' depositors and bond-holders. He renewed it for another year in September 2009 soon after the launch of the National Asset Management Agency (NAMA), a body designed to remove bad loans from the six banks.

Irish banks had lost an estimated 100 billion euros, much of it related to defaulted loans to property developers and homeowners made in the midst of the property bubble, which burst around 2007. Ireland could have guaranteed bank deposits and let private bondholders who had invested in the banks face losses, but instead borrowed money from the ECB to pay these bondholders, shifting the losses and debt to its taxpayers. NAMA purchased over 80 billion euros in bad loans from the banks as the mechanism for this transfer. The economy collapsed during 2008. Unemployment rose from 4% in 2006 to 14% by 2010, while the federal budget went from a surplus in 2007 to a deficit of 32% GDP in 2010, the highest in the history of the euro zone, despite draconian austerity measures.[17][68]

The December 2008 hidden loans controversy within Anglo Irish Bank had led to the resignations of three executives, including chief executive Seán FitzPatrick. A mysterious "Golden Circle" of ten businessmen are being investigated over shares they purchased in Anglo Irish Bank, using loans from the bank, in 2008. The Anglo Irish Bank Corporation Act 2009 was passed to nationalise Anglo Irish Bank was voted through Dáil Éireann and passed through Seanad Éireann without a vote on 20 January 2009.[69] President Mary McAleese then signed the bill at Áras an Uachtaráin the following day, confirming the bank's nationalisation.[70]

In April 2010, following a marked increase in Irish 2-year bond yields, Ireland's NTMA state debt agency said that it had "no major refinancing obligations" in 2010. Its requirement for €20 billion in 2010 was matched by a €23 billion cash balance, and it remarked: "We're very comfortably circumstanced".[71] On 18 May the NTMA tested the market and sold a €1.5 billion issue that was three times oversubscribed.[72]

By September 2010 the banks could not raise finance and the bank guarantee was renewed for a third year. This had a negative impact on Irish government bonds, government help for the banks rose to 32% of GDP, and so the government started negotiations with the EU, the IMF and three nations: the United Kingdom, Denmark and Sweden, resulting in a €67.5 billion "bailout" agreement of 29 November 2010[73][74] Together with additional €17.5 billion coming from Ireland's own reserves and pensions, the government received €85 billion[75], of which €34 billion were used to support the country's ailing financial sector.[76] In return the government agreed to reduce its budget deficit to below three percent by 2015.[76] In February the government lost the ensuing Irish general election, 2011. In April 2011, despite all the measures taken, Moody's downgraded the banks' debt to junk status.[77]

In July 2011 European leaders agreed to cut the interest rate the Ireland is paying on its EU/IMF bailout loan from around 6% to between 3.5% and 4% and to double the loan time to 15 years. The move is expected to save the country between 600-700 million euros per year.[78] On 14 September 2011, in a move to further ease Ireland's difficult financial situation, the European Commission announced to cut the interest rate on its €22.5 billion loan coming from the European Financial Stability Mechanism, down to 2.59 per cent – which is the interest rate the EU itself pays to borrow from financial markets.[79]

The Euro Plus Monitor report from November 2011 attests to Ireland's vast progress in dealing with its financial crisis, expecting the country to stand on its own feet again and finance itself without any external support from the second half of 2012 onwards.[80] According to the Centre for Economics and Business Research Ireland's export-led recovery "will gradually pull its economy out of its trough". As a result of the improved economic outlook, the cost of 10-year government bonds, which has already fallen substantially since mid July 2011 (see the graph "Long-term Interest Rates"), is expected to fall further to 4 per cent by 2015.[81]

Portugal

A report released in January 2011 by the Diário de Notícias[82] and published in Portugal by Gradiva, demonstrated that in the period between the Carnation Revolution in 1974 and 2010, the democratic Portuguese Republic governments have encouraged over-expenditure and investment bubbles through unclear public-private partnerships and funding of numerous ineffective and unnecessary external consultancy and advisory of committees and firms. This allowed considerable slippage in state-managed public works and inflated top management and head officer bonuses and wages. Persistent and lasting recruitment policies boosted the number of redundant public servants. Risky credit, public debt creation, and European structural and cohesion funds were mismanaged across almost four decades. The Prime Minister Sócrates's cabinet was not able to forecast or prevent this in 2005, and later it was incapable of doing anything to improve the situation when the country was on the verge of bankruptcy by 2011.[83]

Robert Fishman, in the New York Times article "Portugal's Unnecessary Bailout", points out that Portugal fell victim to successive waves of speculation by pressure from bond traders, rating agencies and speculators.[84] In the first quarter of 2010, before markets pressure, Portugal had one of the best rates of economic recovery in the EU. From the perspective of Portugal's industrial orders, exports, entrepreneurial innovation and high-school achievement, the country matched or even surpassed its neighbors in Western Europe.[84]

On 16 May 2011 the Eurozone leaders officially approved a €78 billion bailout package for Portugal, which became the third Eurozone country, after Ireland and Greece, to receive emergency funds. The bailout loan will be equally split between the European Financial Stabilisation Mechanism, the European Financial Stability Facility, and the International Monetary Fund.[85] According to the Portuguese finance minister, the average interest rate on the bailout loan is expected to be 5.1 percent.[86] As part of the deal, the country agreed to cut its budget deficit from 9.8 percent of GDP in 2010 to 5.9 percent in 2011, 4.5 percent in 2012 and 3 percent in 2013.[87] The Portuguese government also agreed to eliminate its golden share in Portugal Telecom to pave the way for privatization.[88][89]. In 2012, all public servants had already seen an average wage cut of 20% relative to their 2010 baseline, with cuts reaching 25% for those earning more than 1,500 Euro. This lead to a flee of specialized technicians and top officials from the public service, with many looking for better positions in the private sector or in other European countries.[citation needed]

On 6 July 2011 the ratings agency Moody's had cut Portugal's credit rating to junk status, Moody's also launched speculation that Portugal may follow Greece in requesting a second bailout.[90]

In December 2011 it was reported that Portugal's estimated budget deficit of 4.5 percent in 2011 will be substantially lower than expected, due to a one-off transfer of pension funds. This way the country will meet its 2012 target already a year earlier.[87] Despite the fact that the economy is expected to contract by 3 percent in 2011 the IMF expects the country to be able to return to medium and long-term debt sovereign markets by late 2013.[91].

Possible spread to other countries

One of the central concerns prior to the bailout was that the crisis could spread to several other countries. The crisis has reduced confidence in other European economies. According to the UK Financial Policy Committee "Market concerns remain over fiscal positions in a number of euro area countries and the potential for contagion to banking systems."[92] Besides Ireland, with a government deficit in 2010 of 32.4% of GDP, and Portugal at 9.1%, other countries such as Spain with 9.2% are also at risk.[93]

Financing needs for the eurozone in 2010 come to a total of €1.6 trillion, while the US is expected to issue US$1.7 trillion more Treasury securities in this period,[94] and Japan has ¥213 trillion of government bonds to roll over.[95] According to British economist and historian Niall Ferguson similarities between the U.S. and Greece should not be dismissed.[96]

For 2010, the OECD forecasts $16 trillion will be raised in government bonds among its 30 member countries. Greece has been the notable example of an industrialised country that has faced difficulties in the markets because of rising debt levels. Even countries such as the US, Germany and the UK, have had fraught moments as investors shunned bond auctions due to concerns about public finances and the economy.[97]

Belgium

In 2010, Belgium's public debt was 100% of its GDP – the third highest in the eurozone after Greece and Italy[98] and there were doubts about the financial stability of the banks,[99] following the country's major financial crisis in 2008-2009. After inconclusive elections in June 2010, by November 2011[100] the country still had only a caretaker government as parties from the two main language groups in the country (Flemish and Walloon) were unable to reach agreement on how to form a majority government.[98] In November 2010 financial analysts forecast that Belgium would be the next country to be hit by the financial crisis as Belgium's borrowing costs rose.[99]

However the government deficit of 5% was relatively modest and Belgian government 10-year bond yields in November 2010 of 3.7% were still below those of Ireland (9.2%), Portugal (7%) and Spain (5.2%).[99] Furthermore, thanks to Belgium's high personal savings rate, the Belgian Government financed the deficit from mainly domestic savings, making it less prone to fluctuations of international credit markets.[101] Nevertheless on 25 November 2011, Belgium's long-term sovereign credit rating was downgraded from AA+ to AA by Standard and Poor[102] and 10-year bond yields reached 5.66%.[100] Shortly after Belgian negotiating parties reached an agreement to form a new government. The deal includes spending cuts and tax rises worth about €11 billion, which should bring the budget deficit down to 2.8% of GDP by 2012, and to balance the books in 2015.[103] Following the announcement Belgium 10-year bond yields fell sharply to 4.6%.[104]

France

France's public debt in 2010 was approximately U.S. $2.1 trillion and 83% GDP, with a 2010 budget deficit of 7% GDP.[105] By 16 November 2011, France's bond yield spreads vs. Germany had widened 450% since July, 2011.[106] France's C.D.S. contract value rose 300% in the same period.[107] On 1 December 2011, France's bond yield had retreated and the country successfully auctioned €4.3 billion worth of 10 year bonds at an average yield of 3.18 percent, well below the perceived critical level of 7 percent.[108]

Italy

Italy's deficit of 4.6 percent of GDP in 2010 was similar to Germany’s at 4.3 percent and less than that of the U.K. and France. Italy even has a surplus in its primary budget, which excludes debt interest payments. However, its debt has increased to almost 120 percent of GDP (U.S. $2.4 trillion in 2010) and economic growth was lower than the EU average for over a decade.[109] This has led investors to view Italian bonds more and more as a risky asset.[110] On the other hand, the public debt of Italy has a longer maturity and a big share of it is held domestically. Overall this makes the country more resilient to financial shocks, ranking better than France and Belgium.[111] About 300 billion euros of Italy's 1.9 trillion euro debt matures (is due) in 2012, so it must go to the capital markets for significant refinancing in the near-term.[112]

On 15 July and 14 September 2011, Italy's government passed austerity measures meant to save €124 billion.[113][114] Nonetheless, by 8 November 2011 the Italian bond yield was 6.74 percent for 10-year bonds, climbing above the 7 percent level where the country is thought to lose access to financial markets.[115] On 11 November 2011, Italian 10-year borrowing costs fell sharply from 7.5 to 6.7 percent after Italian legislature approved further austerity measures and the formation of an emergency government to replace that of Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi.[116] The measures include a pledge to raise €15 billion from real-estate sales over the next three years, a two-year increase in the retirement age to 67 by 2026, opening up closed professions within 12 months and a gradual reduction in government ownership of local services.[110] The interim government expected to put the new laws into practice is led by former European Union Competition Commissioner Mario Monti.[110]

Spain

Spain has a comparatively low debt among advanced economies and it does not face a risk of default.[117] The country's public debt relative to GDP in 2010 was only 60%, more than 20 points less than Germany, France or the US, and more than 60 points less than Italy, Ireland or Greece.[118][119] Like Italy, Spain has most of its debt controlled internally, and both countries are in a better fiscal situation than Greece and Portugal, making a default unlikely unless the situation gets far more severe.[120] As one of the largest eurozone economies the condition of Spain's economy is of particular concern to international observers, and faced pressure from the United States, the IMF, other European countries and the European Commission to cut its deficit more aggressively.[121][122] Spain's public debt was approximately U.S. $820 billion in 2010, roughly the level of Greece, Portugal, and Ireland combined.[123]

Rumors raised by speculators about a Spanish bail-out were dismissed by Spanish Prime Minister José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero as "complete insanity" and "intolerable".[124] Nevertheless, shortly after the announcement of the EU's new "emergency fund" for eurozone countries in early May 2010, Spain had to announce new austerity measures designed to further reduce the country's budget deficit, in order to signal financial markets that it was safe to invest in the country.[125] The Spanish government had hoped to avoid such deep cuts, but weak economic growth as well as domestic and international pressure forced the government to expand on cuts already announced in January.

Spain succeeded in trimming its deficit from 11.2% of GDP in 2009 to 9.2% in 2010[126] and around 6% in 2011.[127] However, due to the European crisis and over spending by regional governments, the real deficit in 2011 overshoot 2% relative to the initial 6% budget estimate[127], in fact reaching 8%. To build up additional trust in the financial markets, the government amended the Spanish Constitution in 2011 to require a balanced budget at both the national and regional level by 2020. The amendment states that public debt can not exceed 60% of GDP, though exceptions would be made in case of a natural catastrophe, economic recession or other emergencies.[128][129] The new conservative Spanish government led by Mariano Rajoy aims to cut the deficit further to 4.4 percent in 2012 and 3 percent in 2013.[130]

United Kingdom

According to the Financial Policy Committee "Any associated disruption to bank funding markets could spill over to UK banks."[92] Bank of England governor Mervyn King declared that the UK is very much at risk from a domino-fall of defaults and called on banks to build up more capital when financial conditions allowed. This is because the UK has the highest gross foreign debt of any European country (€7.3 trillion; €117,580 per person) due in large part to its highly leveraged financial industry, which is closely connected with both the United States and the Eurozone.[131]

Solutions

EU emergency measures

European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF)

On 9 May 2010, the 27 EU member states agreed to create the European Financial Stability Facility, a legal instrument[132] aiming at preserving financial stability in Europe by providing financial assistance to eurozone states in difficulty. The EFSF can issue bonds or other debt instruments on the market with the support of the German Debt Management Office to raise the funds needed to provide loans to eurozone countries in financial troubles, recapitalize banks or buy sovereign debt.[133] Emissions of bonds are backed by guarantees given by the euro area member states in proportion to their share in the paid-up capital of the European Central Bank. The €440 billion lending capacity of the Facility is jointly and severally guaranteed by the Eurozone countries' governments and may be combined with loans up to €60 billion from the European Financial Stabilisation Mechanism (reliant on funds raised by the European Commission using the EU budget as collateral) and up to €250 billion from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to obtain a financial safety net up to €750 billion.[134]

On November 29, 2011 the member state finance ministers agreed to expand the EFSF by creating certificates that could guarantee up to 30% of new issues from troubled euro-area governments and to create investment vehicles that would boost the EFSF’s firepower to intervene in primary and secondary bond markets.[135]

- Reception by financial markets

Stocks surged worldwide after the EU announced the EFSF's creation. The Facility eased fears that the Greek debt crisis would spread,[136] and this led to some stocks rising to the highest level in a year or more.[137] The Euro made its biggest gain in 18 months,[138] before falling to a new four-year low a week later.[139] Shortly after the euro rose again as hedge funds and other short-term traders unwound short positions and carry trades in the currency.[140] Commodity prices also rose following the announcement.[141] The dollar Libor held at a nine-month high.[142] Default swaps also fell.[143] The VIX closed down a record almost 30%, after a record weekly rise the preceding week that prompted the bailout.[144] The agreement is interpreted to allow the ECB to start buying government debt from the secondary market which is expected to reduce bond yields.[145] As a result Greek bond yields fell sharply from over 10% to just over 5%.[146] Asian bonds yields also fell with the EU bailout.[147])

- Usage of EFSF funds

The EFSF only raises funds after an aid request is made by a country.[148] As of end of December 2011, it has been activated two times. In November 2010, it financed €17.7 billion of the total €67.5 billion rescue package for Ireland (the rest was loaned from individual European countries, the European Commission and the IMF). In May 2011 it contributed one third of the €78 billion package for Portugal. In the future, it is planned to also shift the loan for Greece to the EFSF, which according to EU diplomats would amount to about €80 billion. This leaves the EFSF with €250 billion or an equivalent of €750 billion in leveraged firepower.[149] According to German newspaper Sueddeutsche, this is more than enough to finance the debt rollovers of all flagging European countries until end of 2012, in case necessary.[149]

The EFSF is set to expire in 2013, running one year parallel to the permanent €500 billion rescue funding program called European Stability Mechanism (ESM), which will start operating as soon as Member States representing 90% of the capital commitments have ratified it. This is expected to be in July 2012.[150][151]

European Financial Stabilisation Mechanism (EFSM)

On 5 January 2011, the European Union created the European Financial Stabilisation Mechanism (EFSM), an emergency funding programme reliant upon funds raised on the financial markets and guaranteed by the European Commission using the budget of the European Union as collateral.[152] It runs under the supervision of the Commission[153] and aims at preserving financial stability in Europe by providing financial assistance to EU member states in economic difficulty.[154] The Commission fund, backed by all 27 European Union members, has the authority to raise up to €60 billion[155] and is rated AAA by Fitch, Moody's and Standard & Poor's.[156][157]

Under the EFSM, the EU successfully placed in the capital markets a €5 billion issue of bonds as part of the financial support package agreed for Ireland, at a borrowing cost for the EFSM of 2.59%.[158]

Like the EFSF also the EFSM will be replaced by the permanent rescue funding programme ESM, which is due to be launched in July 2012.[150]

Brussels agreement and aftermath

On 26 October 2011, leaders of the 17 Eurozone countries met in Brussels and agreed on a 50% write-off of Greek sovereign debt held by banks, a fourfold increase (to about €1 trillion) in bail-out funds held under the European Financial Stability Facility, an increased mandatory level of 9% for bank capitalisation within the EU and a set of commitments from Italy to take measures to reduce its national debt. Also pledged was €35 billion in "credit enhancement" to mitigate losses likely to be suffered by European banks. José Manuel Barroso characterised the package as a set of "exceptional measures for exceptional times".[8][159]

The package's acceptance was put into doubt on 31 October when Greek Prime Minister George Papandreou announced that a referendum would be held so that the Greek people would have the final say on the bailout, upsetting financial markets.[160] On 3 November 2011 the promised Greek referendum on the bailout package was withdrawn by Prime Minister Papandreou.

In late 2011, Landon Thomas in the New York Times noted that some, at least, European banks were maintaining high dividend payout rates and none were getting capital injections from their governments even while being required to improve capital ratios. Thomas quoted Richard Koo, an economist based in Japan, an expert on that country's banking crisis, and specialist in balance sheet recessions, as saying:

I do not think Europeans understand the implications of a systemic banking crisis.... When all banks are forced to raise capital at the same time, the result is going to be even weaker banks and an even longer recession — if not depression.... Government intervention should be the first resort, not the last resort.

Beyond equity issuance and debt-to-equity conversion, then, one analyst "said that as banks find it more difficult to raise funds, they will move faster to cut down on loans and unload lagging assets" as they work to improve capital ratios. This latter contraction of balance sheets "could lead to a depression”, the analyst said.[161] Reduced lending was a circumstance already at the time being seen in a "deepen[ing] crisis" in commodities trade finance in western Europe.[162]

ECB interventions

The European Central Bank (ECB) has taken a series of measures aimed at reducing volatility in the financial markets and at improving liquidity:[163]

- First, it began open market operations buying government and private debt securities in May 2010, reaching €211.5 billion by end of 2011,[164] though it simultaneously absorbed the same amount of liquidity to prevent a rise in inflation.[165] According to Rabobank economist Elwin de Groot, there is a “natural limit” of €300 billion the ECB can sterilize.[166]

- Second, it announced two 3-month and one 6-month full allotment of Long Term Refinancing Operations (LTRO's).

- Thirdly, it reactivated the dollar swap lines[167] with Federal Reserve support.[168]

Subsequently, the member banks of the European System of Central Banks started buying government debt.[169]

The ECB has also changed its policy regarding the necessary credit rating for loan deposits. On 3 May 2010 the ECB announced it will accept as collateral all outstanding and new debt instruments issued or guaranteed by the Greek government, regardless of the nation's credit rating. The moved took some pressure of Greek government bonds, which had just been downgraded to junk status, making it difficult for the government to raise money on capital markets.[51]

Resignations

In September, 2011, Jürgen Stark became the second German after Axel A. Weber to resign from the ECB Governing Council in 2011. Weber, the former Deutsche Bundesbank president, was once thought to be a likely successor to Jean-Claude Trichet as bank president. He and Stark were both thought to have resigned due to "unhappiness with the ECB’s bond purchases, which critics say erode the bank’s independence". Stark was "probably the most hawkish" member of the council when he resigned. Weber was replaced by his Bundesbank successor Jens Weidmann and "[l]eaders in Berlin plan to push for a German successor to Stark as well, news reports said".[170]

Concerted action of several central banks

On 30 November 2011 the European Central Bank, the U.S. Federal Reserve Federal Reserve, the central banks of Canada, Japan, Britain and the Swiss National Bank provided global financial markets with additional liquidity to ward off the debt crisis and to support the real economy. The central banks agreed to lower the cost of dollar Currency swaps by 50 basis points to come into effect on 5 December 2011. They also agreed to provide each other with abundant liquidity to make sure that commercial banks stay liquid in other currencies.[171]

On 21 December 2011, the ECB started the biggest infusion of credit into the European banking system in the euro's 13 year history. It loaned €489 billion to 523 banks for an exceptionally long period of three years at a rate of just one percent.[172] This way the ECB tries to make sure that banks have enough cash to pay off €200 billion of their own maturing debts in the first three months of 2012, and at the same time keep operating and loaning to businesses so that a credit crunch does not choke off economic growth. It also hopes that banks use some of the money to buy government bonds, effectively easing the debt crisis.[173]

On 13 January, 2012, Standard & Poor’s downgraded France and Austria from AAA rating, lowered Spain, Italy (and five other[174]) euro members further, and maintained the top credit rating for Germany and the Netherlands. Commentator David Marsh saw this as a "'winner takes all' polarization" which made resolution more difficult within the economic and monetary union.[175] S&P followed quickly also with a downgrade of the EFSF from AAA to AA+.[174]

Reform and recovery

Slow GDP growth rates correspond to slower growth in tax revenues and higher safety net spending, increasing deficits and debt levels. Fareed Zakaria described the factors slowing growth in the Euro zone, writing in November 2011: "Europe's core problem [is] a lack of growth...Italy's economy has not grown for an entire decade. No debt restructuring will work if it stays stagnant for another decade...The fact is that Western economies - with high wages, generous middle-class subsidies and complex regulations and taxes - have become sclerotic. Now they face pressures from three fronts: demography (an aging population), technology (which has allowed companies to do much more with fewer people) and globalization (which has allowed manufacturing and services to locate across the world)." He advocated lower wages and steps to bring in more foreign capital investment.[176]

- Progress

On 15 November 2011 the Lisbon Council published the Euro Plus Monitor 2011. According to the report most critical eurozone member countries are in the process of rapid reforms. The authors note that "Many of those countries most in need to adjust [...] are now making the greatest progress towards restoring their fiscal balance and external competitiveness". Greece, Ireland and Spain are among the top five reformers and Portugal is ranked seventh among 17 countries included in the report.[177]

Proposed long-term solutions

European fiscal union and revision of the Lisbon Treaty

Angel Ubide from the Peterson Institute for International Economics suggested that long term stability in the eurozone requires a common fiscal policy rather than controls on portfolio investment.[178] In exchange for cheaper funding from the EU, Greece and other countries, in addition to having already lost control over monetary policy and foreign exchange policy since the euro came into being, would therefore also lose control over domestic fiscal policy. Strong European Commission "oversight in the fields of taxation and budgetary policy and the enforcement mechanisms that go with it could further infringe upon the sovereignty of eurozone member states".[179] Think-tanks such as the World Pensions Council have argued that a profound revision of the Lisbon Treaty would be unavoidable if Germany were to succeed in imposing its economic views, as stringent orthodoxy across the budgetary, fiscal and regulatory fronts would necessarily go beyond the treaty in its current form, thus further reducing the individual prerogatives of national governments.[180][181]

In March 2011 a new reform of the Stability and Growth Pact was initiated, aiming at straightening the rules by adopting an automatic procedure for imposing of penalties in case of breaches of either the deficit or the debt rules.[182][183] Germany had pressured other member states to adopt a balanced budget law to achieve a clear cap on new debt, strict budgetary discipline and balanced budgets. Debt breaks applied across the eurozone would imply much tighter fiscal discipline than the bloc’s existing rules requiring deficits of less than 3 per cent of GDP.[184]

By the end of 2011, Germany, France and some other smaller EU countries went a step further and vowed to create a fiscal union across the eurozone with strict and enforceable fiscal rules and automatic penalties embedded in the EU treaties.[9][10] German chancellor Angela Merkel also insisted that the European commission and the European court of justice must play an "important role" in ensuring that countries meet their obligations.[9]

On 9 December 2011 at the European Council meeting, all 17 members of the euro zone and six countries that aspire to join agreed on a new intergovernmental treaty to put strict caps on government spending and borrowing, with penalties for those countries who violate the limits.[185] All other non-eurozone countries except Great Britain are also prepared to join in, subject to parliamentary vote.[150] Originally EU leaders planned to change existing EU treaties but this was blocked by British prime minister David Cameron, who demanded that the City of London be excluded from future financial regulations, including the proposed EU financial transaction tax.[186][186] By the end of the day, 26 countries had agreed to the plan, leaving the United Kingdom as the only country not willing to join.[187] Cameron subsequently conceded that his action had failed to secure any safeguards for the UK.[188]

Britain's refusal to be part of the Franco-German fiscal compact to safeguard the Eurozone constituted a de facto refusal (PM David Cameron vetoed the project) to engage in any radical revision of the Lisbon Treaty at the expense of British sovereignty: centrist analysts such as John Rentoul of The Independent (a generally Europhile newspaper) concluded that "Any Prime Minister would have done as Cameron did".[189]

Eurobonds

On 21 November 2011, the European Commission suggested that eurobonds issued jointly by the 17 euro nations would be an effective way to tackle the financial crisis. Using the term "stability bonds", Jose Manuel Barroso insisted that any such plan would have to be matched by tight fiscal surveillance and economic policy coordination as an essential counterpart so as to avoid moral hazard and ensure sustainable public finances.[190][191]

Germany remains opposed to take over the debt and interest risk of states that have run excessive budget deficits and borrowed excessively over the past years. The German government sees no point in making borrowing easier for states who have problems borrowing so much that they go into debt crisis. Germany says that Eurobonds, jointly issued and underwritten by all 17 members of the currency bloc, could substantially raise the country's liabilities in a debt crisis.

However, a growing field of investors and economists say it would be the best way of solving a debt crisis.[192]

Guy Verhofstadt, leader of the liberal ALDE group in the European parliament suggested following a proposal made by the "five wise economists" from the German Council of Economic Experts, on the creation of a European collective redemption fund. It would mutualise eurozone debt above 60%, combining it with a bold debt reduction scheme for countries not on life support from the EFSF.[192]

The introduction of eurobonds matched by tight financial and budgetary coordination may well require changes in EU treaties.[192]

European Stability Mechanism (ESM)

The European Stability Mechanism (ESM) is a permanent rescue funding programme to succeed the temporary European Financial Stability Facility and European Financial Stabilisation Mechanism in July 2012.[150]

On 16 December 2010 the European Council agreed a two line amendment to the EU Lisbon Treaty to allow for a permanent bail-out mechanism to be established[193] including stronger sanctions. In March 2011, the European Parliament approved the treaty amendment after receiving assurances that the European Commission, rather than EU states, would play 'a central role' in running the ESM.[194][195] According to this treaty, the ESM will be an intergovernmental organisation under public international law and will be located in Luxembourg.[196][197]

Such a mechanism serves as a "financial firewall." Instead of a default by one country rippling through the entire interconnected financial system, the firewall mechanism can ensure that downstream nations and banking systems are protected by guaranteeing some or all of their obligations. Then the single default can be managed while limiting financial contagion.

Address current account imbalances

Regardless of the corrective measures chosen to solve the current predicament, as long as cross border capital flows remain unregulated in the Euro Area,[198] current account imbalances are likely to continue. A country that runs a large current account or trade deficit (i.e., it imports more than it exports) must ultimately be a net importer of capital; this is a mathematical identity called the balance of payments. In other words, a country that imports more than it exports must either decrease its savings reserves or borrow to pay for those imports. Conversely, Germany's large trade surplus (net export position) means that it must either increase its savings reserves or be a net exporter of capital, lending money to other countries to allow them to buy German goods.[199]

The 2009 trade deficits for Italy, Spain, Greece, and Portugal were estimated to be $42.96 billion, $75.31bn and $35.97bn, and $25.6bn respectively, while Germany's trade surplus was $188.6bn.[200] A similar imbalance exists in the U.S., which runs a large trade deficit (net import position) and therefore is a net borrower of capital from abroad. Ben Bernanke warned of the risks of such imbalances in 2005, arguing that a "savings glut" in one country with a trade surplus can drive capital into other countries with trade deficits, artificially lowering interest rates and creating asset bubbles.[201][202][203]

A country with a large trade surplus would generally see the value of its currency appreciate relative to other currencies, which would reduce the imbalance as the relative price of its exports increases. This currency appreciation occurs as the importing country sells its currency to buy the exporting country's currency used to purchase the goods. Alternatively, trade imbalances can be reduced if a country encouraged domestic saving by restricting or penalizing the flow of capital across borders, or by raising interest rates, although this benefit is likely offset by slowing down the economy and increasing government interest payments.[204]

Either way, many of the countries involved in the crisis are on the Euro, so devaluation, individual interest rates and capital controls are not available. The only solution left to raise a country's level of saving is to reduce budget deficits and to change consumption and savings habits. For example, if a country's citizens saved more instead of consuming imports, this would reduce its trade deficit.[204] It has therefore been suggested that countries with large trade deficits (e.g. Greece) consume less and improve their exporting industries. On the other hand, export driven countries with large trade surplus, such as Germany, Austria and the Netherlands would need to shift their economies more towards domestic services and increase wages to support domestic consumption.[32][205]

European Monetary Fund

On 20 October 2011, the Austrian Institute of Economic Research published an article that suggests to transform the EFSF into a European Monetary Fund (EMF), which could provide governments with fixed interest rate Eurobonds at a rate slightly below medium-term economic growth (in nominal terms). These bonds would not be tradable but could be held by investors with the EMF and liquidated at any time. Given the backing of the entire eurozone countries and the ECB "the EMU would achieve a similarly strong position vis-a-vis financial investors as the US where the Fed backs government bonds to an unlimited extent." To ensure fiscal discipline despite the lack of market pressure, the EMF would operate according to strict rules, providing funds only to countries that meet agreed on fiscal and macroeconomic criteria. Governments that lack sound financial policies would be forced to rely on traditional (national) governmental bonds with less favorable market rates.[206]

Since investors would finance governments directly, banks were also no longer able to unduly benefit from intermediary rents by borrowing from the ECB at low rates and investing in government bonds at high rates. Econometric analysis suggests that a stable long-term interest rate of three percent in all eurozone countries would lead to higher nominal GDP growth rates and substantially lower sovereign debt levels by 2015, compared to the baseline scenario with market based interest levels.[206]

Speculation of the breakup of the Eurozone

Economists, mostly from outside Europe, and associated with Modern Monetary Theory and other post-Keynesian schools condemned the design of the Euro currency system from the beginning because it ceded national monetary and economic sovereignty but lacked a central fiscal authority - saying that faced with economic problems, "Without such an institution, EMU would prevent effective action by individual countries and put nothing in its place."[207][208] Some non-Keynesian economists, such as Luca A. Ricci of the IMF, contend the Eurozone does not fulfill the necessary criteria for an optimum currency area, though it is moving in that direction.[177][209]

As the debt crisis expanded beyond Greece, these economists continued to advocate, albeit more forcefully, the disbandment of the Eurozone. If this is not immediately feasible, they recommended that Greece and the other debtor nations unilaterally leave the Eurozone, default on their debts, regain their fiscal sovereignty, and re-adopt national currencies.[210][211]

Bloomberg suggested in June 2011 that, if the Greek and Irish bailouts should fail, an alternative would be for Germany to leave the eurozone in order to save the currency through depreciation[212] instead of austerity. The likely substantial fall in the Euro against a newly reconstituted Deutsche Mark would give a "huge boost" to its members' competitiveness.[213] Also The Wall Street Journal conjectured that Germany could return to the Deutsche Mark,[214] or create another currency union[215] with the Netherlands, Austria, Finland, Luxembourg and other European countries such as Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland and the Baltics.[216] A monetary union of the mentioned current account surplus countries would create the world's largest creditor bloc that is bigger than China[217] or Japan. The former president of the German Industries, Hans-Olaf Henkel suggested that "southern countries" could retain their competitiveness through a greater tolerance for inflation and corresponding regular devaluations, once they are freed of the "straitjacket of Germanic stability phobia".[218] The Wall Street Journal added that without the German-led bloc a residual euro would have the flexibility to keep interest rates low[219] and engage in quantitative easing or fiscal stimulus in support of a job-targeting economic policy[220] instead of inflation targeting in the current configuration.

German Chancellor Angela Merkel and French President Nicolas Sarkozy have, however, on numerous occasions publicly said that they would not allow the Eurozone to disintegrate and have linked the survival of the Euro with that of the entire European Union.[221][222] In September 2011, EU commissioner Joaquín Almunia shared this view, saying that expelling weaker countries from the euro was not an option: "Those who think that this hypothesis is possible just do not understand our process of integration".[223] Furthermore, also former ECB president Jean-Claude Trichet denounced the possibility of a return of the deutsche mark and defended the price stability of the euro.[224]

Some think-tanks such as the World Pensions Council have argued that a profound revision of the Lisbon Treaty would be unavoidable if Germany were to succeed in imposing its economic views, as stringent orthodoxy across the budgetary, fiscal and regulatory fronts would necessarily go beyond the treaty in its current form, thus further reducing the individual prerogatives of national governments.[180][181]

On 26 December 2011, Jim Rogers in an interview with the BBC responded to the assertion that the euro was responsible for the crisis saying, "No, absolutely not. It's not the euro. The world needs the euro or something like it to compete with the US dollar... The eurozone as a whole is not a big debtor nation. The eurozone has some debtor problems, some debtor nations, debtor states, but it's not a big, big problem. The euro is good for the world. It needs to work."[225]

Controversies

Breaking of the EU treaties

- No bail-out clause

The Maastricht Treaty of EU contains juridical language which appears to rule out intra-EU bailouts. First, the “no bail-out” clause (Article 125 TFEU) ensures that the responsibility for repaying public debt remains national and prevents risk premiums caused by unsound fiscal policies from spilling over to partner countries. The clause thus encourages prudent fiscal policies at the national level.

The European Central Bank purchase of distressed country bonds can be viewed to break the prohibition of monetary financing of budget deficits (Article 123 TFEU). The creation of further leverage in EFSF with access to ECB lending would also appear to break this Article.

The Articles 125 and 123 were meant to create disincentive for EU member states to run excessive deficits and state debt, and prevent the moral hazard of over-spend and lending in good times. They were also meant to protect the taxpayers of the other more prudent member states. By issuing bail out aid guaranteed by the prudent Eurozone taxpayers to rule-breaking Eurozone countries such as Greece, the EU and Eurozone countries encourage moral hazard also in the future.[226] While the no bail-out clause remains in place, the "no bail-out doctrine" seems to be a thing of the past.[227]

- Convergence criteria

The EU treaties contain so called convergence criteria. Concerning government finance the states have agreed that the annual government budget deficit should not exceed 3% of the gross domestic product (GDP) and that the gross government debt to GDP should not exceed 60% of the GDP. For Eurozone members there is the Stability and Growth Pact which contains the same requirements for budget deficit and debt limitation but with a much stricter regime. Nevertheless the main crisis states Greece and Italy (status November 2011) have exceeded these criteria excessively over a long period of time.

Actors fueling the crisis

Credit rating agencies

The international U.S. based credit rating agencies – Moody's, Standard & Poor's and Fitch – which have already been under fire during the housing bubble[228][229] and the Icelandic crisis[230][231] - have also played a central[232] and controversial role[233] in the current European bond market crisis.[234] On the one hand, the agencies have been accused of giving overly generous ratings due to conflicts of interest.[235] On the other hand, ratings agencies have a tendency to act conservatively, and to take some time to adjust when a firm or country is in trouble.[236] In the case of Greece, the market responded to the crisis before the downgrades, with Greek bonds trading at junk levels several weeks before the ratings agencies began to describe them as such.[232]

European policy makers have criticized ratings agencies for acting in political manner, accusing the Big Three of bias towards European assets and fueling speculation.[237] Particularly Moody's decision to downgrade Portugal's foreign debt to the category Ba2 "junk" has infuriated officials from the EU and Portugal alike.[237] State owned utility and infrastructure companies like ANA – Aeroportos de Portugal, Energias de Portugal, Redes Energéticas Nacionais, and Brisa – Auto-estradas de Portugal were also downgraded despite claims to having solid financial profiles and significant foreign revenue.[238][239][240][241] France has shown its anger at its downgrade as well. French central bank chief Christian Noyer criticized the decision of Standard & Poor's to lower the rating of France but not that of the United Kingdom, which "has more deficits, as much debt, more inflation, less growth than us". Similar comments were made by high ranking politicians in Germany. Michael Fuchs, deputy leader of the leading Christian Democrats, said: "Standard and Poor's must stop playing politics. Why doesn't it act on the highly indebted United States or highly indebted Britain?", adding that the latter's collective private and public sector debts are the largest in Europe. He further added: "If the agency downgrades France, it should also downgrade Britain in order to be consistent."[242]

Credit rating agencies were also accused of bullying politicians by systematically downgrading eurozone countries just before important European Council meetings. As one EU source put it: "It is interesting to look at the downgradings and the timings of the downgradings ... It is strange that we have so many downgrades in the weeks of summits."[243]

- Regulatory reliance on credit ratings

Think-tanks such as the World Pensions Council have argued that European powers such as France and Germany pushed dogmatically and naïvely for the adoption of the Basel II recommendations, adopted in 2005, transposed in European Union law through the Capital Requirements Directive (CRD), effective since 2008. In essence, they forced European banks, and, more importantly, the European Central Bank itself e.g. when gauging the solvency of EU-based financial institutions, to rely more than ever on the standardized assessments of credit risk marketed by two private US agencies- Moody’s and S&P, thus using public policy and ultimately taxpayers’ money to strengthen an anti-competitive duopolistic industry. Ironically, European governments have abdicated most of their regulatory authority in favor of a non-European, highly deregulated, private cartel… [244]

- Counter measures

Due to the failures of the ratings agencies, European regulators obtained new powers to supervise ratings agencies.[233] With the creation of the European Supervisory Authority in January 2011 the EU set up a whole range of new financial regulatory institutions,[245] including the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA),[246] which became the EU’s single credit-ratings firm regulator.[247] Credit-ratings companies have to comply with the new standards or be denied operation on EU territory, says ESMA Chief Steven Maijoor.[248]

Germany's foreign minister Guido Westerwelle has called for an "independent" European rating agency, which could avoid the conflicts of interest that he claimed US-based agencies faced.[232][249] European leaders are reportedly studying the possibility of setting up a European ratings agency in order that the private U.S.-based ratings agencies have less influence on developments in European financial markets in the future.[250][251] According to German consultant company Roland Berger, setting up a new ratings agency would cost €300 million and could be operating by 2014.[252]

But attempts to regulate more strictly credit rating agencies in the wake of the European sovereign debt crisis have been rather unsuccessful. Some European financial law and regulation experts have argued that the hastily drafted, unevenly transposed in national law, and poorly enforced EU rule on rating agencies (Règlement CE n° 1060/2009) has had little effect on the way financial analysts and economists interpret data or on the potential for conflicts of interests created by the complex contractual arrangements between credit rating agencies and their clients"[253]

Media

There has been considerable controversy about the role of the English-language press in the regard to the bond market crisis.[254][255]

Greek Prime Minister Papandreou is quoted as saying that there was no question of Greece leaving the euro and suggested that the crisis was politically as well as financially motivated. "This is an attack on the eurozone by certain other interests, political or financial".[256] The Spanish Prime Minister José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero has also suggested that the recent financial market crisis in Europe is an attempt to undermine the euro.[257][258] He ordered the Centro Nacional de Inteligencia intelligence service (National Intelligence Center, CNI in Spanish) to investigate the role of the "Anglo-Saxon media" in fomenting the crisis.[259][260][261][262][263][264][265] No results have so far been reported from this investigation.

Other commentators believe that the euro is under attack so that countries, such as the U.K. and the U.S., can continue to fund their large external deficits and large government deficits,[266] and to avoid the collapse of the US dollar.[267][268][269] The U.S. and U.K. do not have large domestic savings pools to draw on and therefore are dependent on external savings e.g. from China.[270][271] This is not the case in the eurozone which is self funding.[272][273]

Speculators

Both the Spanish and Greek Prime Ministers have accused financial speculators and hedge funds of worsening the crisis by short selling euros.[274][275] German chancellor Merkel has stated that "institutions bailed out with public funds are exploiting the budget crisis in Greece and elsewhere."[276]

According to The Wall Street Journal several hedge-funds managers launched "large bearish bets" against the euro in early 2010.[277] On February 8, the boutique research and brokerage firm Monness, Crespi, Hardt & Co. hosted an exclusive "idea dinner" at a private townhouse in Manhattan, where a small group of hedge-fund managers from SAC Capital Advisors LP, Soros Fund Management LLC, Green Light Capital Inc., Brigade Capital Management LLC and others argued that the euro was likely to fall to parity with the US dollar and were of the opinion that Greek government bonds represented the weakest link of the euro and that Greek contagion could soon spread to infect all sovereign debt in the world. Three days later the euro was hit with a wave of selling, triggering a decline that brought the currency below $1.36.[277] There was no suggestion by regulators that there was any collusion or other improper action.[277] On 8 June, exactly four months after the dinner, the Euro hit a four year low at $1.19 before it started to rise again.[278] Traders estimate that bets for and against the euro account for a huge part of the daily three trillion dollar global currency market.[277]

The role of Goldman Sachs[279] in Greek bond yield increases is also under scrutiny.[280] It is not yet clear to what extent this bank has been involved in the unfolding of the crisis or if they have made a profit as a result of the sell-off on the Greek government debt market.

In response to accusations that speculators were worsening the problem, some markets banned naked short selling for a few months.[281]

Doubts about effectiveness of non-Keynesian policies

There has been some criticism over the austerity measures implemented by most European nations to counter this debt crisis. Some argue that an abrupt return to "non-Keynesian" financial policies is not a viable solution and predict the deflationary policies now being imposed on countries such as Greece and Italy might prolong and deepen their recessions.[282] Nouriel Roubini said the new credit available to the heavily indebted countries did not equate to an immediate revival of economic fortunes: "While money is available now on the table, all this money is conditional on all these countries doing fiscal adjustment and structural reform."[283] Robert Skidelsky wrote that it was excessive lending by banks, not deficit spending that created this crisis. Government's mounting debts are a response to the economic downturn as spending rises and tax revenues fall, not its cause.[284]

Apart from arguments over whether or not austerity, rather than increased or frozen spending, is a macroeconomic solution,[285] union leaders have also argued that the working population is being unjustly held responsible for the economic mismanagement errors of economists, investors, and bankers. Over 23 million EU workers have become unemployed as a consequence of the global economic crisis of 2007–2010, while thousands of bankers across the EU have become millionaires despite collapse or nationalization (ultimately paid for by taxpayers) of institutions they worked for during the crisis, a fact that has led many to call for additional regulation of the banking sector across not only Europe, but the entire world.[286]

Odious debt

Some protesters, commentators such as Libération correspondent Jean Quatremer and the Liège based NGO Committee for the Abolition of the Third World Debt (CADTM) allege that the debt should be characterized as odious debt.[287] The Greek documentary Debtocracy examines whether the recent Siemens scandal and uncommercial ECB loans which were conditional on the purchase of military aircraft and submarines are evidence that the loans amount to odious debt and that an audit would result in invalidation of a large amount of the debt.

National statistics

In 1992, members of the European Union signed an agreement known as the Maastricht Treaty, under which they pledged to limit their deficit spending and debt levels. However, a number of EU member states, including Greece and Italy, were able to circumvent these rules and mask their deficit and debt levels through the use of complex currency and credit derivatives structures.[28][29] The structures were designed by prominent U.S. investment banks, who received substantial fees in return for their services and who took on little credit risk themselves thanks to special legal protections for derivatives counterparties.[28] Financial reforms within the U.S. since the financial crisis have only served to reinforce special protections for derivatives—including greater access to government guarantees—while minimizing disclosure to broader financial markets.[288]

The revision of Greece’s 2009 budget deficit from a forecast of "6–8% of GDP" to 12.7% by the new Pasok Government in late 2009 (a number which, after reclassification of expenses under IMF/EU supervision was further raised to 15.4% in 2010) has been cited as one of the issues that ignited the Greek debt crisis.