Language: Difference between revisions

change hat note |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{About| |

{{About|Human language in general|other uses|Language (disambiguation)}} |

||

{{multiple image |

{{multiple image |

||

<!-- Essential parameters --> |

<!-- Essential parameters --> |

||

Revision as of 15:09, 14 August 2012

The Tower of Babel symbolises the division of mankind by a multitude of tongues provided through divine intervention.

Language is either the specifically human capacity for acquiring and using complex systems of communication, or a specific instance of such a system of complex communication. The scientific study of language in any of its senses is called linguistics.

The approximately 6,000 - 7,000 languages currently spoken are the most salient examples, but natural languages can also be based on visual rather than auditory stimuli, for example in sign languages and written language. Codes and other kinds of artificially constructed communication systems such as those used for computer programming can also be called languages. A language in this sense is a system of signs for encoding and decoding information. The English word derives ultimately from Latin lingua, "language, tongue", via Old French.[1] When used as a general concept, "language" may refer to the cognitive faculty that enables humans to learn and use systems of complex communication, or to describe the set of rules that makes up these systems, or the set of utterances that can be produced from those rules.

Language as a communication system is unique to humans, because it consists of complex system of rules relating symbols to their meanings, resulting in an indefinite number of possible new utterances from a finite number of elements. This structure affords a much wider range of expressions than any known system of animal communication. Language is thought to have originated when early hominids first started cooperating, adapting earlier systems of communication based on expressive signs to include a theory of other minds and shared intentionality. This development is thought to have coincided with an increase in brain volume, and many linguists see the structures of language as having evolved to serve specific communicative functions. Language is processed in many different locations in the human brain, but especially in Broca’s and Wernicke’s areas. Humans acquire language through social interaction in early childhood, and children generally speak fluently when they are around three years old. The use of language is deeply entrenched in human culture and, in addition to its strictly communicative uses, it also has many social and cultural uses, such as signifying group identity, social stratification, as well as for social grooming and entertainment.

All languages rely on the process of semiosis to relate a sign with a particular meaning. Oral and sign languages contain a phonological system that governs how symbols are used to form sequences known as words or morphemes, and a syntactic system that governs how words and morphemes are used to form phrases and utterances. Languages evolve and diversify over time, and the history of their evolution can be reconstructed by comparing modern languages to determine which traits their ancestral languages must have had for the later stages to have occurred. A group of languages that descend from a common ancestor is known as a language family. The languages that are most spoken in the world today belong to the Indo-European family, which includes languages such as English, Spanish, Portuguese, Russian and Hindi; the Sino-Tibetan languages, which include Mandarin Chinese, Cantonese and many others; Semitic languages, which include Arabic, Amharic and Hebrew; and the Bantu languages, which include Swahili, Zulu,[2] Shona and hundreds of other languages spoken throughout Africa. The general consensus is that there are between 6000[2] and 7000 languages currently spoken, and that between 50-90% of those will have become extinct by the year 2100.[3]

Definitions

The word "language" has at least two basic meanings: language as a general concept, and "a language" (a specific linguistic system, e.g. "French"). Ferdinand de Saussure first explicitly formulated the distinction, using the French word langage for language as a concept, and langue as the specific instance of language.[4]

When speaking of language as a general concept, some different definitions can be used that stress different aspects of the phenomenon.[5] These definitions also entail different approaches and understandings of language, and they inform different and often incompatible schools of linguistic theory.[6]

Mental faculty, organ or instinct

One definition sees language primarily as the mental faculty that allows humans to undertake linguistic behaviour: to learn languages and produce and understand utterances. This definition stresses the universality of language to all humans and the biological basis of the human capacity for language as a unique development of the human brain.[7][8] This view often understands language to be largely innate, for example as in Chomsky's theory of Universal Grammar, Jerry Fodor’s extreme innatist theory. These kinds of definitions are often applied by studies of language within a cognitive science framework and in neurolinguistics.

Formal symbolic system

Another definition sees language as a formal system of signs governed by grammatical rules of combination to communicate meaning. This definition stresses the fact that human languages can be described as closed structural systems consisting of rules that relate particular signs to particular meanings. This structuralist view of language was first introduced by Ferdinand de Saussure[9], and his structuralism remains foundational for most approaches to language today. Some proponents of this view of language have advocated a formal approach to studying the structures of language, privileging the formulation of underlying abstract rules that can be understood to generate observable linguistic structures. The main proponent of such a theory is Noam Chomsky, who defines language as a particular set of sentences that can be generated from a particular set of rules.[10] The structuralist viewpoint is commonly used in formal logic, semiotics, and in formal and structural theories of grammar, the most commonly used theoretical frameworks in linguistic description. In the philosophy of language these views are associated with philosophers such as Bertrand Russell, early Wittgenstein, Alfred Tarski and Gottlob Frege.[citation needed]

Tool for communication

Yet another definition sees language as a system of communication that enables humans to cooperate. This definition stresses the social functions of language and the fact that humans use it to express themselves and to manipulate objects in their environment. Functional theories of grammar explain grammatical structures by their communicative functions, and understands the grammatical structures of language to be the result of an adaptive process by which grammar was "tailored" to serve communicative needs of its users. This view of language is associated with the study of language in pragmatic, cognitive and interactional frameworks, as well as in socio-linguistics and linguistic anthropology. Functionalist theories tend to study grammar as a dynamic phenomenon, as structures that are always in the process of changing as they are employed by their speakers. This view leads to the study of linguistic typology being of importance, as it can be shown that processes of grammaticalization tend to follow trajectories that are partly dependent on typology. In the philosophy of language these views are often associated with Wittgenstein’s later works and with ordinary language philosophers such as G. E. Moore, Paul Grice, John Searle and J. L. Austin.

What makes human language unique

Human language is unique in comparison to other forms of communication, such as those used by non-human animals.

Communication systems used by other animals such as bees or non-human primates are closed systems, that consist of a closed number of possible things that can be communicated. Human language is open-ended, meaning that it allows humans to produce an infinite set of utterances from a finite set of elements. This we can do because human language is based on a dual code, where a finite number of meaningless elements (e.g. sounds, letters or gestures) can be combined to form units of meaning (words and sentences).[11] Furthermore the symbols and grammatical rules of any particular language are largely arbitrary, meaning that the system can only be acquired through social interaction.[12] The known systems of communication used by animals, on the other hand, can only express a finite number of utterances that are mostly genetically transmitted.[13]

Human languages also differ from animal communication systems in that they employ grammatical and semantic categories such as noun and verb, or present and past, to express exceedingly complex meanings.[14] Human language is also unique in having the property of recursivity; this is the way in which, for example, a noun phrase to contain another noun phrase (as in "the chimpanzee's lips") or a clause to contain a clause (as in "I think that it's raining").[15]. Human language is also the only known natural communication system that is modality independent, meaning that it can be used not only for communication through one channel or media, but through several - for example spoken language uses the auditive modality, whereas sign languages and writing use the visual modality and braille writing uses the tactile modality.

With regards to the meaning that it may convey and the cognitive operations that it builds on, human language is also unique in being able to refer to abstract concepts and to imagined or hypothetical events, as well as events that took place in the past or may happen in the future. This ability to refer to events that are not at the same time or place as the speech event is called "displacement", and while some animal communication systems can use displacement the degree to which it is used in human language is also considered unique.[11]

Origin

Theories about the origin of language can be divided according to their basic assumptions. Some theories are based on the idea that language is so complex that one can not imagine it simply appearing from nothing in its final form, but that it must have evolved from earlier pre-linguistic systems among our pre-human ancestors. These theories can be called continuity-based theories. The opposite viewpoint is that language is such a unique human trait that it cannot be compared to anything found among non-humans and that it must therefore have appeared fairly suddenly in the transition from pre-hominids to early man. These theories can be defined as discontinuity-based. Similarly, some theories see language mostly as an innate faculty that is largely genetically encoded, while others see it as a system that is largely cultural, that is learned through social interaction.[16] Currently the only prominent proponent of a discontinuity-based theory of human language origins is Noam Chomsky. Chomsky proposes that 'some random mutation took place, maybe after some strange cosmic ray shower, and it reorganized the brain, implanting a language organ in an otherwise primate brain'. While cautioning against taking this story too literally, Chomsky insists that 'it may be closer to reality than many other fairy tales that are told about evolutionary processes, including language'.[17] Continuity-based theories are currently held by a majority of scholars, but they vary in how they envision this development. Those who see language as being mostly innate, for example Steven Pinker[18], hold the precedents to be animal cognition, whereas those who see language as a socially learned tool of communication, such as Michael Tomasello[19], see it as having developed from animal communication, either primate gestural or vocal communication. Other continuity-based models see language as having developed from music, a view already espoused by Rousseau, Herder, Humboldt and Charles Darwin. A prominent proponent of this view today is Steven Mithen.[20]

Because the emergence of language is located in the early prehistory of man, the relevant developments have left no direct historical traces and no comparable processes can be observed today. Theories that stress continuity often look at animals to see if, for example, primates display any traits that can be seen as analogous to what pre-human language must have been like. Alternatively, early human fossils can be inspected to look for traces of physical adaptation to language use or for traces of pre-linguistic forms of symbolic behaviour.[21]

It is mostly undisputed that pre-human australopithecines did not have communication systems significantly different from those found in great apes in general, but scholarly opinions vary as to the developments since the appearance of Homo some 2.5 million years ago. Some scholars assume the development of primitive language-like systems (proto-language) as early as Homo habilis, while others place the development of primitive symbolic communication only with Homo erectus (1.8 million years ago) or Homo heidelbergensis (0.6 million years ago) and the development of language proper with Homo sapiens sapiens with the Upper Paleolithic revolution less than 100,000 years ago.[22][23]

The study of language

The study of language, linguistics, has been developing into a science since the first grammatical descriptions of particular languages in India more than 2000 years ago. Today linguistics is a science that concerns itself with all aspects relating to language, examining it from all of the theoretical viewpoints described above.[24]

Subdisciplines

The academic study of language is conducted within many different disciplinary areas and from different theoretical angles, all of which inform modern approaches to linguistics.: For example, Descriptive linguistics examines the grammar of single languages so that people can learn them and linguists can compare them; theoretical linguistics develops theories of how best to conceptualize and define the nature of language, based on data from the various extant human languages; sociolinguistics studies how languages are used for social purposes informing in turn the study of the social functions of language and grammatical description; neurolinguistics studies how language is processed in the human brain, and allows the experimental testing of theories; computational linguistics builds on thoretical and descriptive linguistics to construct computational models of language often aimed at processing natural language, or at testing linguistic hypotheses; and historical linguistics relies on grammatical and lexical descriptions of languages to trace their individual histories and reconstruct trees of language families by using the comparative method.[citation needed]

Early history

The formal study of language began in India with Pāṇini, the 5th century BC grammarian who formulated 3,959 rules of Sanskrit morphology.[citation needed] In the 18th century, the first use of the comparative method by William Jones sparked the rise of comparative linguistics.[25] The scientific study of language was broadened from Indo-European to language in general by Wilhelm von Humboldt. Early in the 20th century, Ferdinand de Saussure introduced the idea of language as a static system of interconnected units, defined through the oppositions between them.[9] By introducing a distinction between diachronic to synchronic analyses of language, he laid the foundation of the modern discipline of linguistics. Saussure also introduced several basic dimensions of linguistic analysis that are still foundational in many contemporary linguistic theories, such as the distinctions between syntagm and paradigm, and the Langue- parole distinction, distinguishing language as an abstract system (language), from language as a concrete manifestation of this system (parole).[26]

Contemporary linguistics

In the 1960s Noam Chomsky formulated the generative theory of language. According to this theory the most basic form of language is a set of syntactic rules that are universal for all humans and which underlies the grammars of all human languages. This set of rules is called Universal Grammar, and for Chomsky describing it is the primary objective of the discipline of linguistics. For this reason the grammars of individual languages are only of importance to linguistics, in so far as they allow us to discern the universal underlying rules from which the observable linguistic variability is generated.[27]

In opposition to the formal theories of the generative school functional theories of language propose that since language is fundamentally a tool, it is reasonable to assume that its structures are best analyzed and understood with reference to the functions they carry out. Functional theories of grammar differs from formal theories of grammar, in that the latter seeks to define the different elements of language and describe the way they relate to each other as systems of formal rules or operations, whereas the former defines the functions performed by language and then relates these functions to the linguistic elements that carry them out.[28] The framework of Cognitive linguistics interprets language in terms of the concepts, sometimes universal, sometimes specific to a particular language, which underlie its forms.[29] Cognitive linguistics is primarily concerned with how the mind creates meaning through language

Physiological and neural architecture of language and speech

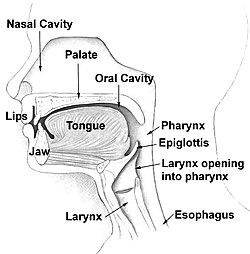

Speaking is the default modality for language in all cultures. The production of spoken language depends on sophisticated capacities for controlling the lips, tongue and other components of the vocal apparatus, the ability to acoustically decode speech sounds, and the neurological apparatus required for acquiring and producing language.[30] The study of the genetic bases for human language is in its incipient state, and the only gene that has been positively implied in language production is FOXP2, which, if affected by mutations, may cause a kind of congenital language disorder.[31]

Brain and language

The brain is the coordinating center of all linguistic activity: It controls both the production of linguistic cognition and of meaning and the mechanics of speech production. Nonetheless our knowledge of the neurological bases for language is quite limited, though it has advanced considerably with the use of modern imaging techniques. The discipline of linguistics dedicated to studying the neurological aspects of language is called neurolinguistics.[32]

Early work in neurolinguistics involved the study of language in people with brain lesions, to see how lesions in specific areas affect language and speech. In this way it was neuroscientists in the 19th century discovered that two areas in the brain are crucially implicated in language processing: Wernicke's area located in the posterior section of the superior temporal gyrus in the dominant cerebral hemisphere. People with a lesion in this area of the brain develop Receptive aphasia, a condition in which there is a major impairment of language comprehension, while speech or retains a natural-sounding rhythm and a relatively normal syntax. The other area is Broca's area located in the posterior inferior frontal gyrus of the dominant hemisphere. People with a lesion to this area develop expressive aphasia, meaning that they know "what they want to say, they just cannot get it out."[33] They are typically able to understand what is being said to them, but unable to fluently speak. Other symptoms that may be present in Broca's aphasia include problems with fluency, articulation, word-finding, word repetition, and producing and comprehending complex grammatical sentences, both orally and in writing.[34] They also exhibit agrammatical speech production and show inability to use syntactic information to determine the meaning of sentences.[35] Both Broca's and Wenicke's aphasia also affect the use of sign language, in analogous ways to how they affect speech, with Broca's aphasia causing signers to sign slowly and with incorrect grammar, whereas a signer with Wernicke's aphasia will sign fluently, but make little sense to others and have difficulties comprehending others' signs. This shows that the impairment is specific to the ability to use language, and not to the physiology used for speech production.[36]

With technological advances in the late 20th century, neurolinguists have also adopted non-invasive techniques such as functional magnetic resonance imaging and electrophysiology to study language processing in individuals without impairments.[32]

Anatomy of speech

Spoken language relies on our physical ability to produce sound, which is technically movement of air creating an frequency capable of moving the human ear drum. This ability depends on the physiology of the human speech organs. These organs consist of the lungs, the voice box (larynx) and the upper vocal tract - the throat, the mouth and the nose. By controlling the different parts of the speech apparatus the airstream can be manipulated to produce different speech sounds.[37]

The sound of speech can be analyzed into a combination of segmental and suprasegmental elements. The segmental elements are those that follow each other in sequences, and which are usually represented by distinct letters in the roman script. In actual free flowing speech, there are no clear boundaries between one segment and the next, nor usually are there any audible pauses between words. Segments therefore are distinguished by their distinct sounds which are a result of their different articulations. Segments are vowels and consonants. Suprasegmental phenomena encompass such elements as phonation type, voice timbre and prosody or intonation all of which can affect multiple segments.[38]

Consonants and vowel segments combine to form syllables, which in turn combine to form utterances, these can be distinguished phonetically as the space between two inhalations. Acoustically these different segments are characterized by different formant structures, which are visible in a spectrogram of the recorded soundwave (See illustration of Spectrogram of the formant structures of three English vowels). [38][39]

Vowels are those sound that have no audible friction caused by the narrowing or obstruction of some part of the upper vocal tract. They vary in quality according to the degree of lip aperture and the placement of the tongue within the oral cavity.[40] Vowels are called close when the lips are relatively closed such as in the pronunciation of the vowel [i] (English "ee"), or open when the lips are relatively open such as in the vowel [a] (English "ah"). If the tongue is located towards the back of the mouth the quality changes creating vowels such as [u] (English "oo"). And the quality also changes in accordance with whether the lips are rounded as opposed to unrounded, creating distinctions such as that between [i] (unrounded front vowel such as English "ee") and [y] (rounded front vowel such as German "ü").[41]

Consonants are those sounds that have audible friction or closure at some point within the upper vocal tract. Consonants sounds vary by place of articulation, characterizing the place within the vocal tract in which the airflow is obstructed - commonly at the lips, teeth, alveolar ridge, palate, velum, ubula or glottis. Each place of articulation produces a different set of consonant sounds, which are further distinguished by manner of articulation - the kind of friction that is occurring - whether full closure in which case the consonant is called a "stop" or an "occlusive", of different degrees of aperture creating fricatives, and approximants. Consonants can also be either "voiced" or "unvoiced", depending on whether the vocal cords are in set vibration by the airflow during the production of the sound. The difference of voicing is what separates English [s] in "bus" (unvoiced sibilant) from [z] in "buzz" (voiced sibilant).[42]

Some speech sounds, both vowels and consonants, are characterized by letting airflow out through the nasal cavity, and these are called nasals or nasalized sounds. Other sounds are defined by the way the tongue moves within the mouth such as the l-sounds (called laterals, because the airflows along both sides of the tongue), and the r-sounds (called rhotics) that are characterized by the way in which the tongue positions itself relative to the airstream. [39]

By using the human speech organs, humans are able to produce hundreds of distinct sounds, some appear with very high frequencies in the world's languages whereas others are much more frequent in certain language families, or language areas, or even specific to a single language.[43]

Structure

When described as a system of symbolic communication, language is traditionally seen as consisting of three parts: signs, meanings and a code connecting signs with their meanings. The study of the process of semiosis, how signs and meanings are combined, used and interpreted is called semiotics. Signs can be composed of sounds, gestures, letters or symbols, depending on whether the language is spoken, signed or written, and they can be combined into complex signs such as words and phrases. When used in communication a sign is encoded and transmitted by a sender through a channel to a receiver who decodes it.[citation needed]

Some of the properties that define human language as opposed to other communication systems are: the arbitrariness of the linguistic sign, meaning that there is no predictable connection between a linguistic sign and its meaning; the duality of the linguistic system, meaning that linguistic structures are built by combining elements into larger structures that can be seen as layered, e.g. how sounds build words and words build phrases; the discreteness of the elements of language, meaning that the elements out of which linguistic signs are constructed are discrete units, e.g. sounds and words, that can be distinguished from each other and rearranged in different patterns; and the productivity of the linguistic system, meaning that the finite number of linguistic elements can be combined into a theoretically infinite number of combinations.[44]

The rules under which signs can be combined to form words and phrases are called syntax or grammar. The meaning that is connected to individual signs, morphemes, words, phrases and texts is called semantics.[citation needed] The division of language into separate but connected systems of sign and meaning goes back to the first linguistic studies of de Saussure and is now used in almost all branches of linguistics.[45]

Semantics

Languages express meaning by relating a sign form to a meaning, its content. Sign forms must be something that can be perceived, for example in sounds, images or gestures, and they come to be related to a specific meaning through the establishment of a social convention. Because the basic relation of meaning for most linguistic signs is based on social convention, linguistic signs can be considered arbitrary, in the sense that the convention is established socially and historically, rather than by means of a natural relation between a specific sign form and its meaning.

Thus languages must have a vocabulary of signs related to specific meaning—the English sign "dog" denotes, for example, a member of the species Canis familiaris. In a language, the array of arbitrary signs connected to specific meanings is called the lexicon, and a single sign connected to a meaning is called a lexeme. Not all meanings in a language are represented by single words - often semantic concepts are embedded in the morphology or syntax of the language in the form of grammatical categories. All languages contain the semantic structure of predication— a structure that predicates a property, state or action. Traditionally semantics has been understood as the study of how speakers and interpreters assign truth values to statements, so that meaning is understood as the process by which a predicate can be said to be true or false about an entity, e.g. "[x [is y]]" or "[x [does y]]." Recently, this model of semantics has been complemented with more dynamic models of meaning that incorporate shared knowledge about the context in which a sign is interpreted into the production of meaning. Such models of meaning are explored in the field of pragmatics.[46]

Sounds and symbols

The ways in which spoken languages use sounds or signs to construct meaning is studied in phonology.[47] The study of how humans produce and perceive vocal sounds is called phonetics.[48] In spoken language meaning is constructed when sounds become part of a system in which some sounds can contribute to expressing meaning and others do not. In any given language only a limited number of the many distinct sounds that can be created by the human vocal apparatus contribute to constructing meaning.[49]

Sounds as part of a linguistic system are called phonemes.[50] Phonemes are abstract units of sound, defined as the smallest units in a language that can serve to distinguish between the meaning of a pair minimally different words, a so called minimal pair. In English for example the words /bat/ [bat] and /pat/ [pʰat] form a minimal in which the distinction between /b/ and /p/ differentiates the two words as having different meanings. But each language contrasts sounds in different ways, so that for example in languages without a that do not distinguish between voiced and unvoiced consonants the sounds [p] and [b] would be considered a single phoneme and consequently the two pronunciations would have the same meaning. Similarly the English language doesn't distinguish phonemically between aspirated and non-aspirated pronunciations of consonants as many other languages do; the unaspirated /p/ in /spin/ [spin] and the aspirated /p/ in /pin/ [pʰin] are considered to be merely different ways of pronouncing the same phoneme (such variants of a single phoneme are called allophones), where as in Mandarin Chinese the same difference in pronunciation distinguishes between the words [pʰá] "crouch" and [pá] "eight" (the accent above the á means that the vowel is pronounced with a high tone).[51]

All oral languages have phonemes of at least two different categories: vowels and consonants that can be combined into forming syllables.[38] Apart from segments such as consonants and vowels, some languages also use sound in other ways to convey meaning. Many languages, for example, use stress, pitch, duration and tone to distinguish meaning. Because these phenomena operate outside of the level of single segments they are called suprasegmental.[52] Some languages have only a few phonemes, for example Rotokas and Pirahã language with 11 and 10 phonemes respectively, to languages like Taa which may have as many as 141 phonemes.[51] In sign languages phonemes (formerly called cheremes) can be the basic elements of gestures such as hand shape, orientation, location, and motion.

Writing systems represent the sounds of human speech using visual symbols. The Latin alphabet (and those on which it is based or that have been derived from it) is based on the representation of single sounds, so that words are constructed from letters that generally denote a single consonant or vowel in the structure of the word. In syllabic scripts, such as the Inuktitut syllabary, each sign represents a whole syllable. In logographic scripts each sign represents an entire word.[53] Because all languages have a very large number of words, no purely logographic scripts are known to exist. In order to represent the sounds of the world’s languages in writing, linguists have developed an International Phonetic Alphabet, designed to represent all of the discrete sounds that are known to contribute to meaning in human languages.[54]

Grammar

Grammar is the study of how meaningful elements (morphemes) within a language can be combined into utterances. Morphemes can either be free or bound. If they are free to be moved around within an utterance, they are usually called words, and if they are bound to other words or morphemes, they are called affixes. The way in which meaningful elements can be combined within a language is governed by rules. The rules obtaining for the internal structure of words are called morphology. The rules of the internal structure of phrases and sentences are called syntax.[55]

Grammatical categories

Grammar can be described as a system of categories, and a set of rules that determine how categories combine to form different aspects of meaning.[56]

Languages differ widely in whether categories are encoded through the use of categories or lexical units. However, several categories are so common as to be nearly universal. Such universal categories include the encoding of the grammatical relations of participants and predicates by grammatically distinguishing between their relations to a predicate, the encoding of temporal and spatial relations on predicates, and a system of grammatical person governing reference to and distinction between speakers and addressees and those about whom they are speaking.[57]

Word classes

Languages organize their parts of speech into classes according to their functions and positions relative to other parts. All languages, for instance, make a basic distinction between a group of words that prototypically denote things and concepts and a group of words that prototypically denote actions and events. The first group, which includes English words such as "dog" and "song," are usually called nouns. The second, which includes "run" and "sing," are called verbs. Other common categories or are adjectives, words that describe properties or qualities of nouns such as "red" or "big". Word classes can be "open", if new words can continuously be added to the class, or relatively "closed", if there is a fixed number of words in a class. In English the class of pronouns is closed, whereas the class of adjectives is open, since infinite numbers of adjectives can be constructed from verbs (e.g. "saddened") or nouns (e.g. with the -like suffix "noun-like"). In other languages such as Korean the situation is the opposite and new pronouns can be constructed, whereas the number of adjectives is fixed.[58]

The word classes also carry out differing functions in grammar. Prototypically verbs are used to construct predicates, while nouns are used as arguments of predicates. In a sentence such as "Sally runs," the predicate is "runs," because it is the word that predicates a specific state about its argument "Sally." Some verbs such as "curse" can take two arguments, e.g. "Sally cursed John." A predicate that can only take a single argument is called intransitive, while a predicate that can take two arguments is called transitive.[citation needed]

Many other word classes exist in different languages, such as conjunctions that serve to join two sentences and articles that introduces a noun, interjections such as "Agh!" or "wow!", ideophones that mimic the sound of some event. Somne languages have positionals, that describe the spatial position of an event or entity. Many languages have classifiers, that identify countable nouns as belonging to a particular type or having a particular shape. For instance, in Mandarin Chinese, the general noun classifier for humans is ge (個), and it is used for counting humans, whatever they are called:

- 3-ge xuesheng (三個學生) lit. "3 human-classifier of student" — 3 students

And for trees, it would be:

- 3-ke shu (三棵樹) lit. "3 tree-classifier of tree" — 3 trees;

Morphology

Many languages use the different process to change or elaborate on the meaning of words by adding or modifying the form of the words. In linguistics, the study of the internal structure of words, and the processes by which words are formed is called morphology. In some languages words are built of several meaningful units called morphemes, for instance the English word "unexpected" can be analyzed as being composed of the three morphemes "un-", "expect" and "-ed".[59]

Morphemes can be classified according to whether they are roots to which other bound morphemes called affixes are added, and bound morphemes can be classified according to their position in relation to the root: prefixes precede the root, suffixes follow the root and infixes are inserted in the middle of a root. Affixes serve to modify or elaborate the meaning of the root. Some languages change the meaning of words by changing the phonological structure of a word, for example the English word "run" which in the past tense is "ran", this process is called ablaut. Furthermore morphology distinguishes between the process of inflection which modifies or elaborates on a word, and the process of derivation which creates a new word from an existing one. In English the verb sing "sing" has the inflectional forms "singing" and "sung" which are both verbs, and the derivational form "singer" which is a noun derived from the verb with the agentive suffix "-er".[60][61]

Languages differ widely in how much they rely on morphology - some languages, traditionally called polysynthetic languages, make extensive use of morphology, so that they express the equivalent of an entire English sentence in a single word. For example the Greenlandic word oqaatiginerluppaa "(he/she) speaks badly about him/her" which consists of the root oqaa and six suffixes.[62]

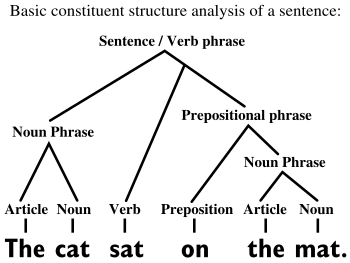

Syntax

Another way in which languages can convey meaning is through the order of words within a sentence. The grammatical rules for sentence structure and the ways in which sentence structure contribute to meaning is called syntax. In English the two sentences "the slaves were cursing the master" and "the master was cursing the slaves" mean different things because the role of grammatical subject is encoded by the noun being in front of the verb and the role of object is encoded by the noun appearing after the verb. But in Latin both Dominus servos vituperabat and Servos vituperabat dominus mean "the master was cursing the slaves", because servos "slaves" is in the accusative case showing that they are the grammatical object of the sentence and dominus "master" is in the nominative case showing that he is the subject. Latin uses morphology to express the distinction between subject and opbject, whereas English uses word order. Another example of how syntactic rules contribute to meaning is the rule of inverse word order in questions which exists in many languages. This rule is the reason that in English, when the phrase "John is talking to Lucy" is turned into a question it becomes "Who is John talking to?" and not "John is talking to who?" (unless one places special emphasis on who in which case the latter does occur).[63]

Syntax also includes the rules for how complex sentences are structured by grouping words together in units, called phrases, that can occupy different places in a larger syntactic structure. Sentences can be described as consisting of phrases connected in a tree structure, connecting the phrases to each other at different levels. To the right is a graphic representation of the syntactic analysis of the English sentence "the cat sat on the mat". The sentence is analysed as being constituted by a noun phrase, a verb and a prepositional phrase; the prepositional phrase is further divided into a preposition and a noun phrase; and the noun phrases consist of an article and a noun. The reason sentences can be seen as composed of phrases is because each phrase would be moved around as a single element if syntactic operations are carried out. For example "the cat" is one phrase and "on the mat" is another because they would be treated as single units if we decided to emphasize the location by moving forward the prepositional phrase: "[And] on the mat, the cat sat". [64] There are numerous competing theories for describing syntactic structures, based on different assumptions about what language is and how it should be described, and each of them would analyze a sentence such as this in a different manner.

Social contexts of use and transmission

While all humans have the ability to learn a language they only do so if they grow up in an environment in which language exists and is used by others. Language is therefore dependent on communities of speakers in which children learn language from their elders and peers, and themselves transmit language to their own children. Languages are used by those who speak them to communicate, and to solve a plethora of social tasks. Many aspects of language use can be seen to be adapted specifically to these purposes.[65] Due to the way in which language is transmitted between generations and within communities, language perpetually changes, diversifying into new languages or converging due to language contact. The process is similar to the process of evolution, where the process of descent with modification leads to the formation of a phylogenetic tree.[66] However languages differ from a biological organisms in that they readily incorporate elements from other languages through the process of diffusion, as speakers of different languages come into contact. Humans also frequently speak more than one language, acquiring their first language or languages as children, or learning new languages as they grow up. Because of the increased language contact in the globalizing world many small languages are becoming endangered as their speakers shift to other languages that afford the possibility to participate in larger and more influential speech communities.[67]

Usage and meaning

The semantic study of meaning assumes that meaning is located in a relation between sign and meaning, firmly established through social convention. But semantics does not study the way in which social conventions are made and affect language. However, when studying the way in which words and signs are used, it is often the case that words have different meanings depending on the social context of use. And signs also change their meaning over time, as the conventions governing their usage gradually change. The study of how the meaning of linguistic expressions change depending on context is called pragmatics. Pragmatics is concerned with the ways in which language use is patterned and how these patterns contribute to meaning.[68] For example in all languages linguistic expressions can be used not just to transmit information, but to perform actions. Certain actions are made only through language, but nonetheless have tangible effects. For example the act of 'naming', which creates a new name for some entity, or the act of 'pronouncing someone man and wife' which creates a social contract of marriage. These types of acts are called speech acts, although they can of course also be carried out through writing or signing.[69] Also many times the form of the linguistic expression does not correspond to the meaning that it actually has in a social context. For example, if at a dinner table a person asks "can you reach the salt?", that is in fact not a question about the length of the interlocutors arms, but a request to pass the salt across the table. This meaning is implied by the context in which it is spoken, these kinds of effects of meaning are called conversational implicatures. These social rules for the ways in which certain ways of using language are considered appropriate in certain situations, and how to understand utterances in relation to their context, vary between communities, and learning them is a large part of acquiring communicative competence in a language.

Language acquisition

All healthy, normally-developing human beings learn to use language. Children acquire the language or languages used around them – whichever languages they receive sufficient exposure to during childhood. The development is essentially the same for children acquiring sign or oral languages.[70] This learning process is referred to as first-language acquisition, since unlike many other kinds of learning it requires no direct teaching or specialized study. In The Descent of Man, naturalist Charles Darwin called this process, "an instinctive tendency to acquire an art."[8]

First language acquisition proceeds in a fairly regular sequence, though there is a wide degree of variation in the timing of particular stages among normally-developing infants. From birth, newborns respond more readily to human speech than to other sounds. Around one month of age, babies appear to be able to distinguish between different speech sounds. Around six months of age, a child will begin babbling, producing the speech sounds or handshapes of the languages used around them. Words appear around the age of 12 to 18 months; the average vocabulary of an eighteen-month old child is around 50 words. A child's first utterances are holophrases (literally "whole-sentences"), utterances that use just one word to communicate some idea. Several months after a child begins producing words, she or he will produce two-word utterances, and within a few more months begin to produce telegraphic speech, short sentences that are less grammatically complex than adult speech, but that do show regular syntactic structure. From roughly the age of three to five years, a child's ability to speak or sign is refined to the point that it resembles adult language.[71]

Language and culture

Languages, understood as the particular set of speech norms of a particular community, are also a part of the larger culture of the community that speak them. Humans use language as a way of signalling identity with one cultural group and difference from others. Even among speakers of one language several different ways of using the language exist, and each is used to signal affiliation with particular subgroups within a larger culture. Linguists and anthropologists, particularly sociolinguists, ethnolinguists and linguistic anthropologists have specialized in studying how ways of speaking vary between speech communities.[citation needed]

Identity

A community's way of using language is a part of the community's culture, just as other shared practices are; it is a way of displaying group identity. Ways of speaking function not only to facilitate communication, but also to identify the social position of the speaker. Linguists use the term varieties, a term that encompasses geographically or socioculturally defined dialects as well as the jargons or styles of subcultures, to refer to the different ways of speaking a language. Linguistic anthropologists and sociologists of language define communicative style as the ways that language is used and understood within a particular culture.[72]

Social status

Languages do not differ only in pronunciation, vocabulary or grammar, but also through having different "cultures of speaking". Some cultures for example have elaborate systems of "social deixis", systems of signalling social distance through linguistic means.[73] In English, social deixis is shown mostly though distinguishing between addressing some people by first name and others by surname, but also in titles such as "Mrs.", "boy", "Doctor" or "Your Honor", but in other languages such systems may be highly complex and codified in the entire grammar and vocabulary of the language. For instance, in several languages of east Asia, such as Thai, Burmese and Javanese, different words are used according to whether a speaker is addressing someone of higher or lower rank than oneself in a ranking system with animals and children ranking the lowest and gods and members of royalty as the highest.[73]

Writing, literacy and technology

The use of writing has made language even more useful to humans, because it can be used to store and transfer much large amounts of complex information than through oral communication. The invention of the first writing systems is roughly contemporary with the beginning of the Bronze Age in the late Neolithic of the late 4th millennium BC. The Sumerian archaic cuneiform script and the Egyptian hieroglyphs are generally considered the earliest writing systems, both emerging out of their ancestral proto-literate symbol systems from 3400–3200 BC with earliest coherent texts from about 2600 BC. It is generally agreed that Sumerian writing was an independent invention; however, it is debated whether Egyptian writing was developed completely independently of Sumerian, or was a case of cultural diffusion. A similar debate exists for the Chinese script, which developed around 1200 BC. The pre-Columbian Mesoamerican writing systems (including among others Olmec and Maya scripts) are generally believed to have had independent origins.

Language change

Languages change as speakers adopt or invent new ways of speaking and pass them on to other members of their speech community.[74] Language change may be motivated by "language internal" factors, such as changes in pronunciation motivated by certain sounds being difficult to distinguish auditively or to produce, or because of certain patterns of change that cause certain rare types of constructions to drift towards more common types.[75] Other causes of language change are social, such as when certain certain pronunciations become emblematic of membership of certain groups, such as social classes, or with ideologies, and therefore are adopted by those who wish to identify with those groups or ideas.[76]

Language contact

One important source of language change is Language contact. Language contact occurs when speakers of two or more languages or varieties interact on a regular basis.[77]

Multilingualism has likely been common throughout much of human history, and today most people in the world are multilingual.[78] In present-day areas such as Sub-Saharan Africa, where there is much variation in language over short distances, it is usual for anyone who has dealings outside their own town or village to know two or more languages.

When speakers of different languages interact closely, it is typical for their languages to influence each other. Language contact can occur at language borders, between adstratum languages, or as the result of migration, with an intrusive language acting as either a superstratum or a substratum.

Language contact occurs in a variety of phenomena, including language convergence, borrowing, and relexification. The most common products are pidgins, creoles, code-switching, and mixed languages.[79][80]

Linguistic diversity

As of 2009, SIL Ethnologue catalogued 6909 living human languages.[81] A "living language" is simply one which is in wide use as a primary form of communication by a specific group of living people. The exact number of known living languages varies from 5,000 to 10,000, depending on the precision of one's definition of "language", and in particular on how one defines the distinction between languages and dialects.

Languages and dialects

There is no clear distinction between a language and a dialect, notwithstanding a famous aphorism attributed to linguist Max Weinreich that "a language is a dialect with an army and navy".[82] For example, national boundaries frequently override linguistic difference in determining whether two linguistic varieties are languages or dialects. Cantonese and Mandarin are for example often classified as "dialects" of Chinese, even though they are more different from each other than Danish is from Norwegian. Before the Yugoslavian civilwar, Serbo-Croatian was considered a single language with two dialects, but now Croatian and Serbian are considered different languages, and employ different writing systems. In other words, the distinction may hinge on political considerations as much as on cultural differences, distinctive writing systems, or degree of mutual intelligibility.[83]

Language endangerment

An language endangerment happens when a language is at risk of falling out of use as its speakers die out or shift to speaking another language. Language loss occurs when the language has no more native speakers, and becomes a "dead language". If eventually no one speaks the language at all, it becomes an "extinct language". While languages have always gone extinct throughout human history, they are currently disappearing at an accelerated rate due to the processes of globalization and neo-colonialism, where the economically powerful languages dominate other languages.[3] The more commonly spoken languages dominate the less commonly spoken languages and therefore, the less commonly spoken languages eventually disappear from populations. The total number of languages in the world is not known. Estimates vary depending on many factors. The general consensus is that there are between 6000[2] and 7000 languages currently spoken, and that between 50-90% of those will have become extinct by the year 2100.[3] The top 20 languages spoken by more than 50 million speakers each, are spoken by 50% of the world's population, whereas many of the other languages are spoken by small communities, most of them with less than 10,000 speakers.[3]

UNESCO operates with five levels of language endangerment: "safe", "vulnerable" (not spoken by children outside the home), "definitely endangered" (children not speaking), "severely endangered" (only spoken by the oldest generations), "critically endangered" (spoken by few members of the oldest generation, often semi-speakers). There is a general consensus that the loss of languages harms the cultural diversity of the world. Many projects are under way aimed at preventing or slowing this loss by revitalizing endangered languages and promoting education and literacy in minority languages. Across the world many countries have enacted specific legislation aimed at protecting and stabilizing the language of indigenous speech communities. A minority of linguists have argued that language loss is a natural process that should not be counteracted, and that documenting endangered languages for posterity is sufficient.[84]

Classification

Languages can be classified on the basis of several different principles:

- paying attention to the historical evolution of languages results in a genetic classification of languages—which is based on genetic relatedness of languages,

- paying attention to the internal structure of languages (grammar) results in a typological classification of languages—which is based on similarity of one or more components of the language's grammar across languages,

- and respecting geographical closeness and contacts between language-speaking communities results in areal groupings of languages.

Language families

The world's languages have been grouped into families of languages that are believed to have common ancestors. Some of the major families are the Indo-European languages, the Afro-Asiatic languages, the Austronesian languages, and the Sino-Tibetan languages.[85]

Typology: Universals and Diversity

An example of a typological classification is the classification of languages on the basis of the basic order of the verb, the subject and the object in a sentence into several types: SVO, SOV, VSO, and so on, languages. (English, for instance, belongs to the SVO language type).[86]

The shared features of languages of one type (= from one typological class) may have arisen completely independently. Their cooccurence might be due to the universal laws governing the structure of natural languages—language universals.[87] Alternatively they might be a result of language evolving convergent solutions to the recurring communicative problems that humans use language to solve.[88]

Diffusion and language areas

The following language groupings can serve as some linguistically significant examples of areal linguistic units, or sprachbunds: Balkan linguistic union, or the bigger group of European languages; Caucasian languages; East Asian languages. Although the members of each group are not closely genetically related, there is a reason for them to share similar features, namely: their speakers have been in contact for a long time within a common community and the languages converged in the course of the history. These are called "areal features".[89]

One should be careful about the underlying classification principle for groups of languages which have apparently a geographical name: besides areal linguistic units, the taxa of the genetic classification (language families) are often given names which themselves or parts of which refer to geographical areas.[90]

Kinds of Language

Natural languages

Human languages are usually referred to as natural languages, and the science of studying them falls under the purview of linguistics. Languages live, die, move from place to place, and change with time. Any language that ceases to change or develop is categorized as a dead language. Conversely, any language that is in a continuous state of change is known as a living language or modern language.[citation needed]

Making a principled distinction between one language and another is sometimes nearly impossible.[91] For instance, there are a few dialects of German similar to some dialects of Dutch. The transition between languages within the same language family is sometimes gradual (see dialect continuum).[citation needed]

Some like to make parallels with biology, where it is not possible to make a well-defined distinction between one species and the next. In either case, the ultimate difficulty may stem from the interactions between languages and populations. (See Dialect or August Schleicher for a longer discussion.)[citation needed]

The concepts of Ausbausprache, Abstandsprache and Dachsprache are used to make finer distinctions about the degrees of difference between languages or dialects.[citation needed]

A sign language is a language which, instead of acoustically conveyed sound patterns, uses visually transmitted sign patterns (manual communication, body language) to convey meaning—simultaneously combining hand shapes, orientation and movement of the hands, arms or body, and facial expressions to fluidly express a speaker's thoughts. Hundreds of sign languages are in use around the world and are at the cores of local Deaf cultures.[citation needed]

Artificial languages

An artificial language is a language the phonology, grammar, and/or vocabulary of which have been consciously devised or modified by an individual or group, instead of having evolved naturally. There are many possible reasons to construct a language: to ease human communication (see international auxiliary language and code); to add depth to a work of fiction or an associated constructed world; for linguistic experimentation; for artistic creation; and for language games.

The expression "planned language" is sometimes used to mean international auxiliary languages and other languages designed for actual use in human communication. Some prefer it to the term "artificial" which may have pejorative connotations in some languages. Outside the Esperanto community, the term language planning means the prescriptions given to a natural language to standardize it; in this regard, even "natural languages" may be artificial in some respects. Prescriptive grammars, which date to ancient times for classical languages such as Latin, Sanskrit, and Chinese are rule-based codifications of natural languages, such codifications being a middle ground between naive natural selection and development of language and its explicit construction.

Mathematics, Logics and computer science use artificial entities called formal languages (including programming languages and markup languages, and some that are more theoretical in nature). These often take the form of character strings, produced by a combination of formal grammar and semantics of arbitrary complexity.

A programming language is a formal language endowed with semantics that can be utilized to control the behavior of a machine, particularly a computer, to perform specific tasks. Programming languages are defined using syntactic and semantic rules, to determine structure and meaning respectively.

Programming languages are employed to facilitate communication about the task of organizing and manipulating information, and to express algorithms precisely. Some authors[who?] restrict the term "programming language" to those languages that can express all possible algorithms; sometimes the term "computer language" is applied to artificial languages that are more limited.[citation needed]

Animal communication

The term "animal languages" is often used for non-human systems of communication. Linguists and semioticians do not consider these to be true "language", but describe them as animal communication on the basis on non-symbolic sign systems,[92] because the interaction between animals in such communication is fundamentally different in its underlying principles from human language. According to this approach, since animals aren't born with the ability to reason, the term "culture", when applied to animal communities, is understood to refer to something qualitatively different than in human communities. Language, communication and culture are more complex amongst humans. A dog may successfully communicate an aggressive emotional state with a growl, which may or may not cause another dog to keep away or back off. Similarly, when a human screams in fear, it may or may not alert other humans of impending danger. Both of these examples communicate, but both are not what would generally be called language.

In several publicized instances, non-human animals have been taught to understand certain features of human language. Karl von Frisch received the Nobel Prize in 1973 for his proof of the sign communication and its variants of the bees.[93] Chimpanzees, gorillas, and orangutans have been taught hand signs based on American Sign Language. The African Grey Parrot, Alex, which possessed the ability to mimic human speech with a high degree of accuracy, is suspected of having had sufficient intelligence to comprehend some of the speech it mimicked. Though animals can be taught to understand parts of human language, they are unable to develop a language.

While proponents of animal communication systems have debated levels of semantics, these systems have not been found to have anything approaching human language syntax.[94]

See also

- Lists

- Category:Lists of languages

- Ethnologue - list of languages, locations, population and genetic affiliation

- Outline of linguistics

- List of language regulators

- Lists of languages

- List of official languages

- Problem of religious language

Notes

- ^ "language". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (3rd ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. 1992.

- ^ a b c Moseley (2010)

- ^ a b c d Austin & Sallabank (2011)

- ^ Lyons (1981:2)

- ^ Lyons (1981:1–8)

- ^ Trask (2007:129–31)

- ^ Hauser & Fitch (2003)

- ^ a b Pinker (1994)

- ^ a b Saussure & Harris (1983)

- ^ Chomsky (1957)

- ^ a b Trask (1999:1–5)

- ^ Trask (1999:9)

- ^ Tomasello (2008)

- ^ Deacon (1997)

- ^ Hauser, Chomsky & Fitch (2002)

- ^ Ulbaek (1998)

- ^ Chomsky (2000:4)

- ^ Pinker (1994)

- ^ Tomasello (2008)

- ^ Fitch (2010:466–507)

- ^ Fitch (2010:250–92)

- ^ Foley (1997:70-74)

- ^ Fitch (2010:292–3)

- ^ Newmeyer (2005)

- ^ Bloomfield 1914, p. 310

- ^ Clarke (1990:143–144)

- ^ Foley (1997:82–83)

- ^ Nichols (1984) "Functional grammar analyzes grammatical structure, as do formal and structural grammar; but it also analyzes the entire communicative situation: the purpose of the speech event, its participants, its discourse context. Functionalists maintain that the communicative situation motivates, constrains, explains, or otherwise determines grammatical structure, and that a structural or formal approaches not merely limited to an artificially restricted data base, but is inadequate ven as a structurala ccount. Functional grammar, then, differs from formala nd structural grammar in that it purports not to model but to explain; and the explanation is grounded in the communicative situation."

- ^ Croft & Cruse (2004:1)

- ^ Trask (1999:11–14, 105–113)

- ^ Fisher, Simon E.; Lai, Cecilia S.L.; Monaco, Anthony P. (2003). "Deciphering the Genetic Basis of Speech and Language Disorders". Annual Review of Neuroscience. 26: 57–80. doi:10.1146/annurev.neuro.26.041002.131144.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ a b Lesser (1989:205–6)

- ^ Trask (1999:105–7)

- ^ N. F. Dronkers, O. Plaisant, M. T. Iba-Zizen, and E. A. Cabanis (2007). "Paul Broca's Historic Cases: High Resolution MR Imaging of the Brains of Leborgne and Lelong". Brain. 130 (Pt 5): 1432–1441. doi:10.1093/brain/awm042. PMID 17405763.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ David Caplan (2006). "Why is Broca's Area Involved in Syntax?". Cortex. 42 (4): 469–471. doi:10.1016/S0010-9452(08)70379-4. PMID 16881251.

- ^ Trask (1999:108)

- ^ MacMahon (1989:2)

- ^ a b c MacMahon (1989:3)

- ^ a b International Phonetic Association (1999:3–8)

- ^ MacMahon (1989:3)

- ^ MacMahon (1989:11–15)

- ^ MacMahon (1989:6–11)

- ^ Ladefoged & Maddieson (1996)

- ^ Lyons (1981:17–24)

- ^ Lyons (1981:218–24)

- ^ Levinson (1983)

- ^ Goldsmith (1995)

- ^ International Phonetic Association (1999)

- ^ Ladefoged & Maddieson (1996)

- ^ International Phonetic Association (1999:27)

- ^ a b Trask (2007:214)

- ^ International Phonetic Association (1999:4)

- ^ Trask (2007:326)

- ^ Trask (2007:123)

- ^ Lyons (1981:103)

- ^ Allerton (1989)

- ^ Payne (1997)

- ^ Trask (2007:208)

- ^ Aronoff & Fudeman (2011:1–2)

- ^ Bauer (2003)

- ^ Haspelmath (2002)

- ^ Rischel, Jørgen. Grønlandsk sprog.[1] Den Store Danske Encyklopædi Vol. 8, Gyldendal

- ^ Trask (2007:179)

- ^ Trask (2007:218–19)

- ^ Evans & Levinson (2009)

- ^ Campbell (2004)

- ^ Austin & Sallabank (2011)

- ^ Levinson (1983:5–35)

- ^ Levinson (1983:226–78)

- ^ Bonvillian, John D. (December 1983). "Developmental milestones: Sign language acquisition and motor development". Child Development. 54 (6): 1435–1445.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthor=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ O'Grady, William; Cho, Sook Whan (2001). "First language acquisition". Contemporary Linguistics: An Introduction (fourth ed.). Boston: Bedford St. Martin's.

- ^ Clancy, Patricia. (1986) "The acquisition of communicative style in Japanese." In B. Schieffelin and E. Ochs (eds) Language Socialization across Cultures. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ a b Foley (1997:311–28)

- ^ Aitchison (2001)

- ^ Labov (1994)

- ^ Labov (2001)

- ^ Thomason (2001:1)

- ^ http://www.cal.org/resources/Digest/digestglobal.html A Global Perspective on Bilingualism and Bilingual Education (1999), G. Richard Tucker, Carnegie Mellon University

- ^ Thomason & Kaufman (1988); Thomason (2001)

- ^ Matras & Bakker (2003)

- ^ "Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Fifteenth edition". Retrieved 28 June 2007, ISBN 1-55671-159-X

- ^ Rickerson, E.M. "What's the difference between dialect and language?". The Five Minute Linguist. College of Charleston. Retrieved 17 July 2011.

- ^ Lyons (1981:26)

- ^ Ladefoged (1992)

- ^ Katzner (1999); Comrie (2009); Brown & Ogilvie (2008)

- ^ Nichols (1992);Comrie (1989)

- ^ Greenberg (1966)

- ^ Evans & Levinson (2009)

- ^ Campbell (2002)

- ^ Aikhenvald (2001)

- ^ "Language". The New Encyclopædia Britannica: MACROPÆDIA. Vol. 22. Encyclopædia Britannica,Inc. 2005. pp. 548 2b.

- ^ Cobley, P. 2010. Routledge Companion to Semiotics. London.

- ^ Frisch, K. v. 1953. 'Sprache' oder 'Kommunikation' der Bienen? Psychologische Rundschau 4.

- ^ Sebeok, T. A. 1996. Signs, bridges, origins. In: Trabant, Jürgen (ed.), Origins of Language. Budapest: Collegium Budapest, 89–115.

References

- Aikhenvald, Alexandra (2001). "Introduction". In Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald; R. M. W. Dixon (eds.). Areal diffusion and genetic inheritance: problems in comparative linguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 1–26.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Aitchison, Jean (2001). Language Change: Progress or Decay? (3rd (1st edition 1981) ed.). Cambridge, New York, Melbourne: Cambridge University Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Allerton, D. J. (1989). "Language as Form and Pattern: Grammar and its Categories". An Encyclopedia of Language. London:NewYork: Routledge.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|editorfirst=ignored (|editor-first=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|editorlast=ignored (|editor-last=suggested) (help) - Aronoff, Mark; Fudeman, Kirsten (2011). What is Morphology. John Wiley & Sons.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Austin, Peter K; Sallabank, Julia (2011). "Introduction". In Austin, Peter K; Sallabank, Julia (eds.). Cambridge Handbook of Endangered Languages. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-88215-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bauer, Laurie (2003). Introducing linguistic morphology (2nd ed.). Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press. ISBN 0-87840-343-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bloomfield, Leonard (1914). An introduction to the study of language. New York: Henry Holt and Company.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Brown, Keith; Ogilvie, Sarah, eds. (2008). Concise Encyclopedia of Languages of the World. Elsevier Science. ISBN 0080877745.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Campbell, Lyle (2002). "Areal linguistics". In Bernard Comrie, Neil J. Smelser and Paul B. Balte (ed.). International Encyclopedia of Social and Behavioral Sciences. Oxford: Pergamon. pp. 729–33.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Campbell, Lyle (2004). Historical Linguistics: an Introduction (2nd ed.). Edinburgh and Cambridge, MA: Edinburgh University Press and MIT Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Chomsky, Noam (1957). Syntactic Structures. The Hague: Mouton.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Chomsky, Noam (2000). The Architecture of Language. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Clarke, David S. (1990). Sources of semiotic: readings with commentary from antiquity to the present. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Comrie, Bernard (1989). Language universals and linguistic typology: Syntax and morphology (2nd ed.). Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 0-226-11433-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Comrie, Bernard, ed. (2009). The World's Major Languages. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-35339-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Croft, William; Cruse, D. Alan (2004). Cognitive Linguistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Crystal, David (1997). The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Deacon, Terrence (1997). The Symbolic Species: The Co-evolution of Language and the Brain. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-31754-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Evans, Nicholas; Levinson, Stephen C. (2009). "The myth of language universals: Language diversity and its importance for cognitive science". 32 (5). Behavioral and Brain Sciences: 429–492.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Fitch, W. Tecumseh (2010). The Evolution of Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Foley, William A. (1997). Anthropological Linguistics: An Introduction. Blackwell.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Goldsmith, John A (1995). "Phonological Theory". In John A. Goldsmith (ed.). The Handbook of Phonological Theory. Blackwell Handbooks in Linguistics. Blackwell Publishers. ISBN 1-4051-5768-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Greenberg, Joseph (1966). Language Universals: With Special Reference to Feature Hierarchies. The Hague: Mouton & Co.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Haspelmath, Martin (2002). Understanding morphology. London: Arnold, Oxford University Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) (pbk)}} - Hauser, Marc D.; Chomsky, Noam; Fitch, W. Tecumseh (2002). "The Faculty of Language: What Is It, Who Has It, and How Did It Evolve?". Science 22. 298 (5598): 1569–1579.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hauser, Marc D.; Fitch, W. Tecumseh (2003). "What are the uniquely human components of the language faculty?". In M.H. Christiansen and S. Kirby (ed.). Language Evolution: The States of the Art. Oxford University Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - International Phonetic Association (1999). Handbook of the International Phonetic Association: A guide to the use of the International Phonetic Alphabet. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-65236-7 (hb); ISBN 0-521-63751-1 (pb).

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Katzner, K (1999). The Languages of the World. New York: Routledge.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Labov, William (1994). Principles of Linguistic Change vol.I Internal Factors. Blackwell.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Labov, William (2001). Principles of Linguistic Change vol.II Social Factors. Blackwell.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ladefoged, Peter (1992). "Another view of endangered languages". Language. 68 (4): 809–11.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ladefoged, Ian; Maddieson (1996). The sounds of the world's languages. Oxford: Blackwell. pp. 329–330. ISBN 0-631-19815-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lesser, Ruth (1989). "Language in the Brain: Neurolinguistics". An Encyclopedia of Language. London:NewYork: Routledge.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|editorfirst=ignored (|editor-first=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|editorlast=ignored (|editor-last=suggested) (help) - Levinson, Stephen C. (1983). Pragmatics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lyons, John (1981). Language and Linguistics. ISBN 0-521-29775-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Text "publisher\Cambridge University Press" ignored (help) - MacMahon, M.K.C. (1989). "Language as available sound:Phonetics". An Encyclopedia of Language. London:NewYork: Routledge.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|editorfirst=ignored (|editor-first=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|editorlast=ignored (|editor-last=suggested) (help) - Matras, Yaron; Bakker, Peter, eds. (2003). The Mixed Language Debate: Theoretical and Empirical Advances. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-017776-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Moseley, Christopher, ed. (2010). Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger, 3rd edition. Paris: UNESCO Publishing.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Newmeyer, Frederick J. (2005). The History of Linguistics. Linguistic Society of America. ISBN 0-415-11553-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Nichols, Johanna (1992). Linguistic diversity in space and time. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-58057-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Nichols, Johanna (1984). "Functional Theories of Grammar". Annual Review of Anthropology. 13.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Text "97-117" ignored (help) - Payne, Thomas Edward (1997). Describing morphosyntax: a guide for field linguists. Cambridge University Press. pp. 238–241.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Pinker, Steven (1994). The Language Instinct: How the Mind Creates Language. Perennial.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Saussure, Ferdinand de; Harris, Roy, Translator (1983) [1913]. Bally, Charles; Sechehaye, Albert (eds.). Course in General Linguistics. La Salle, Illinois: Open Court. ISBN 0-8126-9023-0.

{{cite book}}:|first2=has generic name (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Swadesh, Morris (1934). "The phonemic principle". Language. 10 (2): 117–129. doi:10.2307/409603. JSTOR 409603.

- Tomasello, Michael (2008). Origin of Human Communication. MIT Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Thomason, Sarah G.; Kaufman, Terrence (1988). Language Contact, Creolization and Genetic Linguistics. University of California Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Thomason, Sarah G. (2001). Language Contact - An Introduction. Edinburgh University Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Trask, Robert Lawrence (1999). Language: The Basics (2nd ed.). Psychology Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Trask, Robert Lawrence (2007). Stockwell, Peter (ed.). Language and Linugistics: The Key Concepts (2nd ed.). Routledge.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ulbaek, Ib (1998). "The Origin of Language and Cognition". In J. R. Hurford & C. Knight (ed.). Approaches to the evolution of language. Cambridge University Press. pp. 30–43.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Further reading

- Polinsky, Maria; Comrie, Bernard; Matthews, Stephen (2003). The atlas of languages: the origin and development of languages throughout the world. New York: Facts on File. ISBN 0-8160-5123-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links