John C. Calhoun: Difference between revisions

→Nullification: See talk page. |

|||

| Line 149: | Line 149: | ||

Calhoun had begun to oppose increases in protective tariffs, as they generally benefitted Northerners more than Southerners. While Vice President in the Adams administration, Jackson's supporters devised a high tariff legislation that placed duties on imports that were also made in New England. Calhoun had been assured that the northeastern interests would reject the [[Tariff of 1828]], exposing pro-Adams New England congressmen to charges that they selfishly opposed legislation popular among [[Jacksonian democracy|Jacksonian Democrats]] in the west and Mid-Atlantic States. The southern legislators miscalculated and the so-called "Tariff of Abominations" passed. Frustrated, Calhoun returned to his South Carolina plantation to write "[[South Carolina Exposition and Protest]]," an essay rejecting the centralization philosophy.{{sfn|Bartlett|1994}} The dispute led to the Nullification Crisis. |

Calhoun had begun to oppose increases in protective tariffs, as they generally benefitted Northerners more than Southerners. While Vice President in the Adams administration, Jackson's supporters devised a high tariff legislation that placed duties on imports that were also made in New England. Calhoun had been assured that the northeastern interests would reject the [[Tariff of 1828]], exposing pro-Adams New England congressmen to charges that they selfishly opposed legislation popular among [[Jacksonian democracy|Jacksonian Democrats]] in the west and Mid-Atlantic States. The southern legislators miscalculated and the so-called "Tariff of Abominations" passed. Frustrated, Calhoun returned to his South Carolina plantation to write "[[South Carolina Exposition and Protest]]," an essay rejecting the centralization philosophy.{{sfn|Bartlett|1994}} The dispute led to the Nullification Crisis. |

||

Calhoun supported the idea of nullification through a [[concurrent majority]]. Nullification is a legal theory that a state has the right to nullify, or invalidate, any federal law which that state has deemed unconstitutional. In Calhoun's words, it is "the right of a State to interpose, in the last resort, in order to arrest an unconstitutional act of the General Government, within its limits."<ref>"Report Prepared for the Committee on Federal Relations of the Legislature of South Carolina, at its Session in November, 1831", in ''The Works of John C. Calhoun'', Vol. VI. p. 96. Crallé, R.K. ed. (1888) D. Appleton.</ref> Nullification can be traced back to arguments by Jefferson and Madison in writing the [[Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions]] of 1798 against the [[Alien and Sedition Acts]]. Madison expressed the hope that the states would declare the acts unconstitutional, while Jefferson explicitly endorsed nullification.<ref>[http://billofrightsinstitute.org/founding-documents/primary-source-documents/virginia-and-kentucky-resolutions/ Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions (1798)] ''Bill of Rights Institute.'' Retrieved January 6, 2016.</ref> Calhoun |

Calhoun supported the idea of nullification through a [[concurrent majority]]. Nullification is a legal theory that a state has the right to nullify, or invalidate, any federal law which that state has deemed unconstitutional. In Calhoun's words, it is "the right of a State to interpose, in the last resort, in order to arrest an unconstitutional act of the General Government, within its limits."<ref>"Report Prepared for the Committee on Federal Relations of the Legislature of South Carolina, at its Session in November, 1831", in ''The Works of John C. Calhoun'', Vol. VI. p. 96. Crallé, R.K. ed. (1888) D. Appleton.</ref> Nullification can be traced back to arguments by Jefferson and Madison in writing the [[Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions]] of 1798 against the [[Alien and Sedition Acts]]. Madison expressed the hope that the states would declare the acts unconstitutional, while Jefferson explicitly endorsed nullification.<ref>[http://billofrightsinstitute.org/founding-documents/primary-source-documents/virginia-and-kentucky-resolutions/ Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions (1798)] ''Bill of Rights Institute.'' Retrieved January 6, 2016.</ref> Calhoun openly argued for a state's right to secede from the Union, as a last resort, in order to protect its liberty and sovereignty. Madison rebuked supporters of nullification, stating that no state had the right to nullify federal law.{{sfn|Rutland|1997|pp= 248–249}} |

||

In his 1828 essay "South Carolina Exposition and Protest", Calhoun argued that a state could veto any federal law that went beyond the enumerated powers and encroached upon the residual powers of the State.{{sfn|Calhoun |1992| pp= 348–49}} President Jackson, meanwhile, generally supported states' rights, but was strongly against nullification and secession. At the 1830 [[Jefferson-Jackson Day|Jefferson Day]] dinner at Jesse Brown's Indian Queen Hotel, Jackson proposed a toast and proclaimed, "Our federal Union, it must be preserved." Calhoun replied, "the Union, next to our liberty, the most dear."{{sfn|Niven |1993| p= 173}} |

In his 1828 essay "South Carolina Exposition and Protest", Calhoun argued that a state could veto any federal law that went beyond the enumerated powers and encroached upon the residual powers of the State.{{sfn|Calhoun |1992| pp= 348–49}} President Jackson, meanwhile, generally supported states' rights, but was strongly against nullification and secession. At the 1830 [[Jefferson-Jackson Day|Jefferson Day]] dinner at Jesse Brown's Indian Queen Hotel, Jackson proposed a toast and proclaimed, "Our federal Union, it must be preserved." Calhoun replied, "the Union, next to our liberty, the most dear."{{sfn|Niven |1993| p= 173}} |

||

Revision as of 23:38, 22 June 2016

John C. Calhoun | |

|---|---|

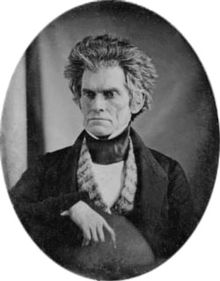

Calhoun by George Peter Alexander Healy | |

| 7th Vice President of the United States | |

| In office March 4, 1825 – December 28, 1832 | |

| President | |

| Preceded by | Daniel D. Tompkins |

| Succeeded by | Martin Van Buren |

| 16th United States Secretary of State | |

| In office April 1, 1844 – March 10, 1845 | |

| President | |

| Preceded by | Abel P. Upshur |

| Succeeded by | James Buchanan |

| 10th United States Secretary of War | |

| In office December 8, 1817 – March 4, 1825 | |

| President | James Monroe |

| Preceded by | William H. Crawford |

| Succeeded by | James Barbour |

| United States Senator from South Carolina | |

| In office November 26, 1845 – March 31, 1850 | |

| Preceded by | Daniel Elliott Huger |

| Succeeded by | Franklin H. Elmore |

| In office December 29, 1832 – March 4, 1843 | |

| Preceded by | Robert Y. Hayne |

| Succeeded by | Daniel Elliott Huger |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from South Carolina's 6th district | |

| In office March 4, 1811 – November 3, 1817 | |

| Preceded by | Joseph Calhoun |

| Succeeded by | Eldred Simkins |

| Personal details | |

| Born | John Caldwell Calhoun March 18, 1782 Abbeville, South Carolina, United States |

| Died | March 31, 1850 (aged 68) Washington, D.C., United States |

| Resting place | St. Philip's Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic (1839–1850) |

| Other political affiliations |

|

| Spouse | Floride Calhoun |

| Children | 10 |

| Parent(s) | Patrick Calhoun and Martha Caldwell |

| Alma mater | |

| Signature | |

John C. Calhoun (/kælˈhuːn/;[1] March 18, 1782 – March 31, 1850) was an American statesman and political theorist from South Carolina, who is best remembered for his strong defense of slavery and for advancing the concept of minority rights in politics, which he did in the context of defending Southern values from perceived Northern threats. He began his political career as a nationalist, modernizer, and proponent of a strong national government and protective tariffs. By the late 1820s, his views reversed and he became a leading proponent of states' rights, limited government, nullification, and opposition to high tariffs—he saw Northern acceptance of these policies as the only way to keep the South in the Union. His beliefs and warnings heavily influenced the South's secession from the Union in 1860–61.

Calhoun began his political career with election to the House of Representatives. As a prominent leader of the war hawk faction, Calhoun strongly supported the War of 1812 to defend American honor against Britain. He then served as Secretary of War under President James Monroe, and in his position reorganized and modernized the War Department. In the 1824 presidential election, he was the overwhelming choice of the electoral college for Vice President of the United States. He served under John Quincy Adams and continued under Andrew Jackson, who defeated Adams in 1828.

Calhoun had a difficult relationship with Jackson primarily because of the Nullification Crisis and the Petticoat Affair. In contrast with his previous nationalism, Calhoun vigorously supported South Carolina's right to nullify Federal tariff legislation which he believed unfairly favored the North, putting him into conflict with unionists such as Jackson. In 1832 he resigned as vice president, and entered the Senate. He sought the Democratic nomination for the presidency in 1844, but lost to surprise nominee James K. Polk. He served as Secretary of State under John Tyler from 1844 to 1845. He then returned to the Senate, where he opposed the Mexican–American War, the Wilmot Proviso, and the Compromise of 1850 before his death in 1850. Calhoun often served as a virtual party-independent who variously aligned as needed with Democrats and Whigs.

Yet Calhoun was known as the "cast-iron man" for his ideological rigidity.[2][3] His concept of republicanism emphasized approval of slavery and minority rights, as particularly embodied by the Southern states—he owned "dozens of slaves in Fort Hill, South Carolina".[4] To protect minority rights against majority rule, he called for a concurrent majority whereby the minority could sometimes block proposals that it felt infringed on their liberties. To this end, Calhoun supported states' rights and nullification, through which states could declare null and void federal laws that they viewed as unconstitutional. Calhoun was one of the "Great Triumvirate" or the "Immortal Trio" of Congressional leaders, along with his Congressional colleagues Daniel Webster and Henry Clay. In 1957, a Senate Committee selected Calhoun as one of the five greatest U.S. Senators of all time.[5]

Early life

John Caldwell Calhoun was born in Abbeville District, South Carolina on March 18, 1782, the fourth child of Patrick Calhoun (1727–1796) and his wife Martha Caldwell. His father had joined the Scotch-Irish immigration from County Donegal to the backcountry of South Carolina.[6] Patrick Calhoun belonged to the Calhoun clan in the tight-knit Scots-Irish community on the Southern frontier. He was known as an Indian fighter and an ambitious surveyor, farmer, planter and politician. As a Presbyterian, he stood opposed to the Anglican elite based in Charleston. He was a Patriot in the American Revolution, and opposed ratification of the federal Constitution on grounds of states' rights and personal liberties. These opinions helped shape his son's attitudes regarding these issues.[7]

Young Calhoun showed scholastic talent, and although schools were scarce on the Carolina frontier, he was enrolled briefly in an academy in Georgia, which soon closed. He continued his studies privately. However, when his father died, his brothers were away starting business careers so 14 year old Calhoun took over management of the family farm and five other farms. For four years he simultaneously kept up his reading and his hunting and fishing. The family decided he should continue his education, so he resumed study of Latin, Greek, history, and mathematics under a local tutor.

With financing from his brothers, he went to Yale College in Connecticut in 1802. For the first time he encountered serious, advanced, well-organized intellectual dialogue that could shape his mind. Yale was dominated by President Timothy Dwight, a Federalist who became his mentor. Dwight's brilliance entranced (and sometimes repelled) Calhoun. Biographer John Niven says:

- Calhoun admired Dwight's extemporaneous sermons, his seemingly encyclopedic knowledge, and his awesome mastery of the classics, of the tenets of Calvinism, and of metaphysics. No one, he thought, could explicate the language of John Locke with such clarity."[8]

Dwight repeatedly denounced Jeffersonian democracy, and Calhoun challenged him in class. Dwight could not shake Calhoun's commitment to republicanism. "Young man," retorted Dwight, "your talents are of a high order and might justify you for any station, but I deeply regret that you do not love sound principles better than sophistry – you seem to possess a most unfortunate bias for error."[9] Dwight also expounded on the strategy of secession from the Union as a legitimate solution for New England's disagreements with the national government.[10][11]

Calhoun made friends easily, read widely, and was a noted member of the debating society of Brothers in Unity. He graduated as valedictorian in 1804. He studied law at the nation's only real law school, Tapping Reeve Law School in Litchfield, Connecticut, where he worked with Tapping Reeve and James Gould. He was admitted to the South Carolina bar in 1807.[12] Biographer Margaret Coit argues that:

- every principle of secession or states' rights which Calhoun ever voiced can be traced right back to the thinking of intellectual New England ... Not the South, not slavery, but Yale College and Litchfield Law School made Calhoun a nullifier ... Dwight, Reeve, and Gould could not convince the young patriot from South Carolina as to the desirability of secession, but they left no doubts in his mind as to its legality.[13]

Marriage, family, and religion

In January 1811, Calhoun married Floride Bonneau Colhoun, a first cousin once removed.[14] She was the daughter of wealthy United States Senator and lawyer John E. Colhoun, a leader of Charleston high society. The couple had ten children over eighteen years; three died in infancy: Andrew Pickens Calhoun, Floride Pure Calhoun, Jane Calhoun, Anna Maria Calhoun, Elizabeth Calhoun, Patrick Calhoun, John Caldwell Calhoun, Jr., Martha Cornelia Calhoun, James Edward Calhoun, and William Lowndes Calhoun.[15] Calhoun's fourth child, Anna Maria, married Thomas Green Clemson, founder of Clemson University in South Carolina.[16]

While her husband was Vice President in the Jackson administration, Floride Calhoun was a central figure in the Petticoat Affair, in which she humiliated key allies of President Andrew Jackson. Mrs. Calhoun was an active Episcopalian and Calhoun sometimes accompanied her to church.[15][17] However, he was also a founding member of All Souls Unitarian Church in Washington, D.C.[18] He rarely mentioned religion; a Presbyterian in his early life, historians believe he was closest to the informal Unitarianism typified by Thomas Jefferson. In a letter he wrote to his daughter Anna Maria, Calhoun provided a clue to his religious thought: "Do our best, our duty for our country, and leave the rest to Providence."[19] In John C. Calhoun: American Portrait, Calhoun biographer Margaret Coit says he was raised Calvinist, briefly affiliated with Unitarianism, and for most of his life remained somewhere between the two. Before he died, he was touched by the Second Great Awakening, a Protestant revival movement during the late 1700s and early 1800s.[20] Historian Merrill Peterson describes Calhoun, "Intensely serious and severe, he could never write a love poem, though he often tried, because every line began with 'whereas' ..."[21]

House of Representatives

War of 1812

With a base among the Irish (or Scotch Irish), Calhoun won election to the House of Representatives in 1810. He immediately became a leader of the War Hawks, along with Speaker Henry Clay of Kentucky and South Carolina congressmen William Lowndes and Langdon Cheves. Brushing aside the vehement objections of anti-war New Englanders, they demanded war against Britain to preserve American honor and republican values.[22] In the spring of 1812, Calhoun became the acting chairman of the Committee on Foreign Affairs.[23] On June 3, 1812, Calhoun's committee called for a declaration of war in ringing phrases, denouncing Britain's "lust for power," "unbounded tyranny," and "mad ambition." Historian James Roark says, "These were fighting words in a war that was in large measure about insult and honor."[24] The United States declared war on Britain on June 18, thus inaugurating the War of 1812. The opening phase involved multiple disasters for American arms, as well as a financial crisis when the Treasury could barely pay the bills. The conflict caused economic hardship for the Americans, as the Royal Navy blockaded the ports and cut off imports, exports and the coastal trade. Several attempted invasions of Canada were fiascos, but the U.S. in 1813 did seize control of Lake Erie and brake the power of hostile Indians in battles such as the Battle of the Thames in Canada in 1813 and the Battle of Horseshoe Bend in Alabama in 1814.[25]

Calhoun labored to raise troops, provide funds, speed logistics, rescue the currency, and regulate commerce to aid the war effort. One colleague hailed him as, "the young Hercules who carried the war on his shoulders."[26] Disasters on the battlefield made him double his legislative efforts to overcome the obstructionism of John Randolph of Roanoke, Daniel Webster, and other opponents of the war. In December 1814, with the armies of Napoleon Bonaparte apparently defeated, and the British invasion of New York thwarted, British and American diplomats signed the Treaty of Ghent. It called for a return to the borders of 1812 with no gains or losses. Before the treaty reached the Senate for ratification, and even before news of its signing reached New Orleans, a massive British invasion force was utterly defeated in January 1815 at the Battle of New Orleans, making a national hero of General Andrew Jackson. Americans celebrated what they called a "second war of independence" against Britain, and an "Era of Good Feelings" began. Calhoun, however, realized how badly prepared the nation had been in 1812.[27]

Postwar planning

The mismanagement of the Army during the war distressed Calhoun, and he resolved to strengthen and centralize the War Department.[28] The militia had proven itself quite unreliable during the war and Calhoun saw the need for a permanent and professional military force. Historian Ulrich B. Phillips has traced Calhoun's complex plans to permanently strengthen the nation's military capabilities. In 1816 he called for building an effective navy, including steam frigates, as well as a standing army of adequate size. The British blockade of the coast had underscored the necessity of rapid means of internal transportation; Calhoun proposed a system of "great permanent roads." The blockade had cut off the import of manufactured items, so he emphasized the need to encourage more domestic manufacture, fully realizing that industry was based in the Northeast. The dependence of the old financial system on import duties was devastated when the blockade cut off imports. Calhoun called for a system of internal taxation which would pay for a future war, without reliance on tariffs. The expiration for the charter of the First Bank of the United States had also distressed the Treasury, so to reinvigorate and modernize the economy Calhoun called for a new national bank. A new bank was chartered as the Second Bank of the United States by President James Madison in 1816. Throughout his proposals, Calhoun emphasized a national footing and downplayed sectionalism and states rights. Phillips says that at this stage of Calhoun's career, "The word nation was often on his lips, and his conviction was to enhance national unity which he identified with national power."[29]

Rhetorical style

Regarding his career in the House of Representatives, an observer commented that Calhoun was "the most elegant speaker that sits in the House ... His gestures are easy and graceful, his manner forcible, and language elegant; but above all, he confines himself closely to the subject, which he always understands, and enlightens everyone within hearing."[30]

His talent for public speaking required systematic self-discipline and practice. A later critic noted the sharp contrast between his hesitant conversations and his fluent speaking styles, adding that Calhoun "had so carefully cultivated his naturally poor voice as to make his utterance clear, full, and distinct in speaking and while not at all musical it yet fell pleasantly on the ear".[31] Calhoun was "a high-strung man of ultra intellectual cast".[32] As such, Calhoun was not known for charisma. He was often seen as harsh and aggressive with other representatives.[33][34] But he was a brilliant intellectual orator and strong organizer. Historian Russell Kirk says, "That zeal which flared like Greek fire in Randolph burned in Calhoun, too; but it was contained in the Cast-iron Man as in a furnace, and Calhoun's passion glowed out only through his eyes. No man was more stately, more reserved."[35]

Secretary of War and Postwar Nationalism

In 1817, President James Monroe appointed Calhoun Secretary of War. He took office on December 8 and served until 1825. Calhoun continued his role as a leading nationalist during the "Era of Good Feelings". He proposed an elaborate program of national reforms to the infrastructure that would speed economic modernization. His first priority was an effective navy, including steam frigates, and in the second place a standing army of adequate size; and as further preparation for emergency "great permanent roads", "a certain encouragement" to manufactures, and a system of internal taxation which would not be subject to collapse by a war-time shrinkage of maritime trade like customs duties. He spoke for a national bank, for internal improvements (such as harbors, canals and river navigation) and a protective tariff that would help the industrial Northeast and, especially, pay for the expensive new infrastructure.[36]

After the war ended in 1815 the "Old Republicans" in Congress, with their Jeffersonian ideology for economy in the federal government, sought to reduce the operations and finances of the War Department. In 1817, the deplorable state of the War Department led four men to decline offers to accept the Secretary of War position before Calhoun finally assumed the role. His political rivalry with William H. Crawford, the Secretary of the Treasury, over the pursuit of the presidency in the 1824 election complicated Calhoun's tenure as War Secretary. In addition, Calhoun opposed the invasion of Florida launched in 1818 by General Jackson during the First Seminole War, which was done without direct authorization from Calhoun or President Monroe.[37] The United States annexed Florida from Spain in 1819 through the Adams-Onis Treaty. The subsequent peace meant that a large army, such as that preferred by Calhoun, was no longer necessary, and in 1821 significant cutbacks were made.[38]

As secretary, Calhoun had responsibility for management of Indian affairs. He promoted a plan, adopted by Monroe in 1825, to preserve the sovereignty of Eastern Indians by relocating them to western reservations they could control without interference from state governments.[39] In over seven years Calhoun supervised the negotiation and ratification of 40 treaties with Indian tribes.[40] A reform-minded modernizer, he attempted to institute centralization and efficiency in the Indian department, but Congress either failed to respond to his reforms or responded with hostility. Calhoun's frustration with congressional inaction, political rivalries, and ideological differences spurred him to create the Bureau of Indian Affairs in 1824.[41]

Vice Presidency

1824 and 1828 elections

Calhoun was initially a candidate for President of the United States in the election of 1824. After failing to win the endorsement of the South Carolina legislature, he decided to be a candidate for Vice President.[23][42] The Electoral College elected Calhoun vice president by a landslide. However, no presidential candidate received a majority in the Electoral College and the election was ultimately resolved by the House of Representatives, where John Quincy Adams was declared the winner over Crawford, Clay, and Jackson, who in the election had led Adams in both popular vote and electoral vote. After Clay, the Speaker of the House, was appointed Secretary of State by Adams, Jackson's supporters denounced what they considered a "corrupt bargain" between Adams and Clay to give Adams the presidency in exchange for Clay receiving the office of Secretary of State. Calhoun also expressed some concerns, which caused friction between him and Adams.[19]

Disillusioned with Adams' high tariff policies and increased centralization, Calhoun wrote to Jackson on June 4, 1826, informing him that he would support Jackson's second campaign for the presidency in 1828. The two were never particularly close friends. Calhoun never fully trusted Jackson, a frontiersman and popular war hero, but hoped that his election would bring some reprieve from Adams's anti-states' rights policies.[23] Jackson selected Calhoun as his running mate, and together they defeated Adams and his running mate Richard Rush. Calhoun thus became the second of two vice presidents to serve under two different presidents, the other being George Clinton, who served as Vice President from 1805 to 1812 under Thomas Jefferson and James Madison.[43]

However, Calhoun's service under Jackson also proved contentious due largely to the Nullification Crisis and the Petticoat Affair.[23]

Nullification

Calhoun had begun to oppose increases in protective tariffs, as they generally benefitted Northerners more than Southerners. While Vice President in the Adams administration, Jackson's supporters devised a high tariff legislation that placed duties on imports that were also made in New England. Calhoun had been assured that the northeastern interests would reject the Tariff of 1828, exposing pro-Adams New England congressmen to charges that they selfishly opposed legislation popular among Jacksonian Democrats in the west and Mid-Atlantic States. The southern legislators miscalculated and the so-called "Tariff of Abominations" passed. Frustrated, Calhoun returned to his South Carolina plantation to write "South Carolina Exposition and Protest," an essay rejecting the centralization philosophy.[44] The dispute led to the Nullification Crisis.

Calhoun supported the idea of nullification through a concurrent majority. Nullification is a legal theory that a state has the right to nullify, or invalidate, any federal law which that state has deemed unconstitutional. In Calhoun's words, it is "the right of a State to interpose, in the last resort, in order to arrest an unconstitutional act of the General Government, within its limits."[45] Nullification can be traced back to arguments by Jefferson and Madison in writing the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions of 1798 against the Alien and Sedition Acts. Madison expressed the hope that the states would declare the acts unconstitutional, while Jefferson explicitly endorsed nullification.[46] Calhoun openly argued for a state's right to secede from the Union, as a last resort, in order to protect its liberty and sovereignty. Madison rebuked supporters of nullification, stating that no state had the right to nullify federal law.[47]

In his 1828 essay "South Carolina Exposition and Protest", Calhoun argued that a state could veto any federal law that went beyond the enumerated powers and encroached upon the residual powers of the State.[48] President Jackson, meanwhile, generally supported states' rights, but was strongly against nullification and secession. At the 1830 Jefferson Day dinner at Jesse Brown's Indian Queen Hotel, Jackson proposed a toast and proclaimed, "Our federal Union, it must be preserved." Calhoun replied, "the Union, next to our liberty, the most dear."[49]

In May 1830, Jackson discovered that Calhoun had asked President Monroe to censure then-General Jackson for his invasion of Spanish Florida in 1818 while Calhoun was serving as Secretary of War. Jackson had invaded Florida during the First Seminole War without explicit public authorization from Calhoun or Monroe. Calhoun's and Jackson's relationship deteriorated further.[37] By February 1831, the break between Calhoun and Jackson was final. Responding to inaccurate press reports about the feud, Calhoun had published letters between him and Jackson detailing the conflict in the United States Telegraph.[23] Jackson and Calhoun began an angry correspondence which lasted until Jackson stopped it in July.[23]

Jackson sent U.S. Navy warships to Charleston harbor, and threatened to hang Calhoun or any man who worked to support nullification or secession.[50] Tensions eased after both sides agreed to the Compromise Tariff of 1833, which was proposed by Henry Clay, now a Whig senator, to change the tariff law in a manner which satisfied Calhoun, who by then was in the Senate. On the same day, Congress passed the Force Bill, which empowered the President of the United States to use military force to ensure state compliance with Federal law. South Carolina then nullified the Force Bill.[51] In Calhoun's speech on the Force Bill, delivered on February 5, 1833, no longer as vice president, he strongly endorsed nullification, at one point saying:

Why, then, confer on the President the extensive and unlimited powers provided in this bill? Why authorize him to use military force to arrest the civil process of the State? But one answer can be given: That, in a contest between the State and the General Government, if the resistance be limited on both sides to the civil process, the State, by its inherent sovereignty, standing upon its reserved powers, will prove too powerful in such a controversy, and must triumph over the Federal Government, sustained by its delegated and unlimited authority; and in this answer we have an acknowledgment of the truth of those great principles for which the State has so firmly and nobly contended.[52]

Petticoat Affair

The Petticoat Affair ended friendly relations between Calhoun and Jackson. Floride Calhoun organized Cabinet wives (hence the term "petticoats") against Peggy Eaton, wife of Secretary of War John Eaton, and refused to associate with her. They alleged that John and Peggy Eaton had engaged in an adulterous affair while she was still legally married to her first husband, and that her recent behavior was unladylike. The allegations of scandal created an intolerable situation for Jackson.[53]

Jackson sided with the Eatons. He and his wife Rachel Donelson had undergone similar political attacks stemming from their marriage in 1791, which occurred despite the fact that, unknown to them, Rachel's previous husband had failed to finalize their divorce. He saw attacks on Eaton stemming ultimately from the political opposition of Calhoun, who had failed to silence his wife's criticisms.[15] At the suggestion of Secretary of State Martin Van Buren, who had sided with the Eatons, Jackson replaced all but one of his Cabinet members, thereby limiting Calhoun's influence. Van Buren began the process by resigning as Secretary of State, facilitating Jackson's removal of others. Van Buren thereby grew in favor with Jackson, while the rift between the President and Calhoun was widened.[54] Later, in 1832, Calhoun cast a tie-breaking vote against Van Buren's confirmation as Minister to Great Britain in a failed attempt to end his political career.[23]

Resignation

As tensions over nullification escalated, South Carolina Senator Robert Hayne was considered less capable than Calhoun to lead the Senate debates. So in late 1832 Hayne resigned to become governor. On December 28, Calhoun resigned as vice president to become a senator, with a voice in the debates.[55] Van Buren had already been elected as Jackson's new vice president, meaning that Calhoun had less than 3 months left on his term anyway. Calhoun was the first of two vice presidents to resign, the second being Spiro Agnew in 1973.[56]

First term in the U.S. Senate

When Calhoun took his seat in the Senate on December 29, 1832, his chances of becoming President were considered scarce due to his involvement in the Nullification Crisis.[23] After implementation of the Compromise Tariff of 1833, which helped solve the Nullification Crisis, the Nullifier Party, along with other anti-Jackson politicians, formed a coalition known as the Whig Party. Calhoun sometimes affiliated with the Whigs, but chose to remain a virtual independent due to the Whig promotion of federally subsidized "internal improvements" and a national bank. Many Southern politicians opposed these as benefiting Northern industrial interests. By 1837 Calhoun generally had realigned himself with most of the Democrats' policies.[57]

To restore his national stature, Calhoun cooperated with Jackson's chosen successor, Van Buren, who became president in 1837. Democrats were very hostile to national banks, and the country's bankers had joined the Whig Party. The Democratic replacement, meant to help combat the Panic of 1837, was the "Independent Treasury" system, which Calhoun supported and which went into effect.[58] Calhoun, like Jackson and Van Buren, attacked finance capitalism, which he saw as the common enemy of the Northern laborer, the Southern planter, and every small farmer. Despite being opposed to the concept of political parties, he worked to unite these groups in the Democratic Party, and to dedicate that party to states' rights and agricultural interests as barriers against encroachment by government and big business.[44] Calhoun resigned from the Senate on March 4, 1843, four years before the expiration of his term, and returned to Fort Hill to prepare an attempt to win the Democratic nomination for the 1844 presidential election.[59] However, he gained little support, and decided to quit. Former Tennessee Governor and House Speaker James K. Polk, a strong Jacksonian, eventually won the nomination and the general election, in which he defeated Clay.[60]

Secretary of State

Appointment and Oregon Boundary Dispute

When Whig president William Henry Harrison died in 1841 after a month in office, Vice President John Tyler succeeded him. Tyler was a former Democrat who was expelled from the Whig Party after vetoing bills passed by the Whig congressional majority to reestablish a national bank and raise tariffs.[61] He named Calhoun Secretary of State on April 10, 1844, following the death of Abel P. Upshur in the USS Princeton disaster. A major crisis emerged from the persistent Oregon boundary dispute between Great Britain and the United States, due to an increasing number of American migrants. The territory included most of present-day British Columbia, Washington, Oregon, and Idaho. American expansionists used the slogan "54-40 or fight" in reference to the Northern boundary coordinates of the Oregon territory. The parties compromised, ending the war threat, by splitting the area down the middle at the 49th parallel, with the British acquiring British Columbia and the Americans accepting Washington and Oregon. Calhoun, along with President Polk and Secretary of State James Buchanan, continued work on the treaty while he was a senator, and it was ratified by a vote of 41-14 on June 18, 1846.[62]

Texas

Tyler and Calhoun were eager to annex the independent Republic of Texas, which wanted to join the Union. Texas was slave country and anti-slavery elements in the North denounced annexation as a plot to enlarge the "Slave Power". When the Senate could not muster a two-thirds vote to pass a treaty of annexation with Texas, Calhoun devised a joint resolution of the Houses of Congress, which secured the simple majority required, and Texas joined the Union. Mexico had warned repeatedly that it would go to war if Texas joined the Union. In response to the United States presence in Texas, the Mexican–American War broke out in 1846.[44]

Second term in the Senate

Calhoun was reelected to the Senate in 1845 following the resignation of Daniel Elliott Huger, and opposed the Mexican–American War. He believed, among other things, that it would distort the national character by bringing non-white persons into the country.[23] (See The Evils of War and Political Parties.) He ultimately chose to abstain from voting on the war measure.[63] Calhoun also vigorously opposed the Wilmot Proviso, an 1846 proposal by Pennsylvania Representative David Wilmot to ban slavery in all newly acquired territories.[64] The House of Representatives, through its Northern majority, passed the provision several times. However, the Senate, where non-slave and slave states had more equal representation, never passed the measure.[64] Calhoun supported Whig candidate and slaveholder Zachary Taylor for president in 1848 over Democratic candidate Lewis Cass, a Northerner who favored popular sovereignty to determine a new state's slaveholding status.[65]

Rejection of the Compromise of 1850

The Compromise of 1850, devised by Clay and Stephen Douglas, a first-term Democratic senator from Illinois, was designed to solve the controversy over the status of slavery in the vast new territories acquired from Mexico. Calhoun, weeks from death and too feeble to speak, wrote a blistering attack on the compromise that would become most likely his most famous speech. On March 4, a friend, Senator James Mason of Virginia, read the remarks.[66] Calhoun affirmed the right of the South to leave the Union in response to Northern subjugation. He warned that the day "the balance between the two sections" was destroyed would be a day not far removed from disunion, anarchy, and civil war. Calhoun queried how the Union might be preserved in light of subjugation by the "stronger" party against the "weaker" one. He maintained that the responsibility of solving the question lay entirely on the North—as the stronger section, to allow the Southern minority an equal share in governance and to cease the agitation. He added, "If you who represent the stronger portion, cannot agree to settle them on the broad principle of justice and duty, say so; and let the States we both represent agree to separate and part in peace. If you are unwilling we should part in peace, tell us so; and we shall know what to do, when you reduce the question to submission or resistance."[59]

Calhoun died soon afterwards, and although the compromise measures did eventually pass, Calhoun's ideas about states' rights attracted increasing attention across the South. Historian William Barney argues that Calhoun's ideas proved "appealing to Southerners concerned with preserving slavery ... Southern radicals known as 'fire-eaters' pushed the doctrine of states rights to its logical extreme by whole upholding the constitutional right of the state to secede."[67]

Death and burial

Calhoun died at the Old Brick Capitol boarding house in Washington, D.C., on March 31, 1850, of tuberculosis, at the age of 68. He was interred at the St. Philip's Churchyard in Charleston, South Carolina. During the Civil War, a group of Calhoun's friends were concerned about the possible desecration of his grave by Federal troops and, during the night, removed his coffin to a hiding place under the stairs of the church. The next night, his coffin was buried in an unmarked grave near the church, where it remained until 1871, when it was again exhumed and returned to its original place.[68]

Calhoun's widow, Floride, died on July 25, 1866, and was buried in St. Paul's Episcopal Church Cemetery in Pendleton, South Carolina, near their children, but apart from her husband.[15]

Political philosophy

Agrarian republicanism

Historian Lee H. Cheek, Jr., distinguishes between two strands of American republicanism:

- the puritan tradition, based in New England; and

- the agrarian or South Atlantic tradition, which Cheek argues was espoused by Calhoun.

While the New England tradition stressed a politically centralized enforcement of moral and religious norms to secure civic virtue, the South Atlantic tradition relied on a decentralized moral and religious order based on the idea of subsidiarity (or localism). Cheek maintains the "Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions" (1798), written by Jefferson and Madison, were the cornerstone of Calhoun's republicanism. Calhoun emphasized the primacy of subsidiarity—holding that popular rule is best expressed in local communities that are nearly autonomous while serving as units of a larger society.[69]

Slavery

Calhoun led the pro-slavery faction in the Senate, opposing both abolitionism and attempts such as the Wilmot Proviso to limit the expansion of slavery into the western territories.[70] He was a major advocate of the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law, which required the cooperation of local law enforcement officials in free states to return escaped slaves.[44]

Calhoun's father, Patrick Calhoun, helped shape his son's political views. He was a staunch slaveholder who taught his son that social standing depended not merely on a commitment to the ideal of popular self-government but also on the ownership of a substantial number of slaves. Flourishing in a world in which slaveholding was a hallmark of civilization, Calhoun saw little reason to question its morality as an adult. He believed that the spread of slavery into the back country of his own state improved public morals by ridding the countryside of the shiftless poor whites who had once held the region back.[71] He further believed that slavery instilled in the remaining whites a code of honor that blunted the disruptive potential of private gain and fostered the civic-mindedness that lay near the core of the republican creed. From such a standpoint, the expansion of slavery into the backcountry decreased the likelihood for social conflict and postponed the declension when money would become the only measure of self-worth, as had happened in New England. Calhoun was thus firmly convinced that slavery was the key to the success of the American dream.[72]

Whereas other Southern politicians had excused slavery as a "necessary evil", in a famous speech on the Senate floor on February 6, 1837, Calhoun asserted that slavery was a "positive good".[73] He rooted this claim on two grounds: white supremacy and paternalism. All societies, Calhoun claimed, are ruled by an elite group which enjoys the fruits of the labor of a less-exceptional group. Senator William Rives of Virginia earlier had referred to slavery as an evil that might become a "lesser evil" in some circumstances. Calhoun believed that conceded too much to the abolitionists:[74]

- I take higher ground. I hold that in the present state of civilization, where two races of different origin, and distinguished by color, and other physical differences, as well as intellectual, are brought together, the relation now existing in the slaveholding States between the two, is, instead of an evil, a good—a positive good ... I may say with truth, that in few countries so much is left to the share of the laborer, and so little exacted from him, or where there is more kind attention paid to him in sickness or infirmities of age. Compare his condition with the tenants of the poor houses in the more civilized portions of Europe—look at the sick, and the old and infirm slave, on one hand, in the midst of his family and friends, under the kind superintending care of his master and mistress, and compare it with the forlorn and wretched condition of the pauper in the poorhouse ... I hold then, that there never has yet existed a wealthy and civilized society in which one portion of the community did not, in point of fact, live on the labor of the other.[75]

Calhoun rejected the belief of Southern leaders such as Henry Clay that all Americans could agree on the "opinion and feeling" that slavery was wrong, although they might disagree on the most practicable way to respond to that great wrong. Calhoun's constitutional ideas acted as a viable conservative alternative to Northern appeals to democracy, majority rule, and natural rights.[76]

In addition to providing the intellectual justification of slavery, Calhoun played a central role in devising the South's overall political strategy. Phillips explains how:

Organization and strategy were widely demanded in Southern defense, and Calhoun came to be regarded as the main source of plans, arguments, and inspiration. His devices were manifold: to suppress agitation, to praise the slaveholding system; to promote Southern prosperity and expansion; to procure a Western alliance; to frame a fresh plan of government by concurrent majorities; to form a Southern bloc; to warn the North of the dangers of Southern desperation; to appeal for Northern magnanimity as indispensable for the saving of the Union.[55]

The evils of war and political parties

Calhoun was consistently opposed to the War with Mexico from the outset, arguing that an enlarged military effort would only feed the alarming and growing lust of the public for empire regardless of its constitutional dangers, bloat executive powers and patronage, and saddle the republic with a soaring debt that would disrupt finances and encourage speculation. Calhoun feared, moreover, that Southern slave owners would be shut out of any conquered Mexican territories, as nearly happened with the Wilmot Proviso. He argued that the war would detrimentally lead to the annexation of all of Mexico, which would bring in Mexicans, deficient in moral and intellectual terms. He said, in a speech on January 4, 1848:

We make a great mistake, sir, when we suppose that all people are capable of self-government. We are anxious to force free government on all; and I see that it has been urged in a very respectable quarter, that it is the mission of this country to spread civil and religious liberty over all the world, and especially over this continent. It is a great mistake. None but people advanced to a very high state of moral and intellectual improvement are capable, in a civilized state, of maintaining free government; and amongst those who are so purified, very few, indeed, have had the good fortune of forming a constitution capable of endurance.[77]

Anti-slavery Northerners denounced the war as a Southern conspiracy to expand slavery; Calhoun in turn perceived a connivance of Yankees to destroy the South. By 1847 he decided the Union was threatened by a totally corrupt party system. He believed that in their lust for office, patronage and spoils, politicians in the North pandered to the anti-slavery vote, especially during presidential campaigns, and politicians in the slave states sacrificed Southern rights in an effort to placate the Northern wings of their parties. Thus, the essential first step in any successful assertion of Southern rights had to be the jettisoning of all party ties. In 1848–49, Calhoun tried to give substance to his call for Southern unity. He was the driving force behind the drafting and publication of the "Address of the Southern Delegates in Congress, to Their Constituents."[78] It alleged Northern violations of the constitutional rights of the South, then warned southern voters to expect forced emancipation of slaves in the near future, followed by their complete subjugation by an unholy alliance of unprincipled Northerners and blacks, and a South forever reduced to "disorder, anarchy, poverty, misery, and wretchedness." Only the immediate and unflinching unity of Southern whites could prevent such a disaster. Such unity would either bring the North to its senses or lay the foundation for an independent South. But the spirit of union was still strong in the region and fewer than 40% of the southern congressmen signed the address, and only one Whig.[44]

Many Southerners believed his warnings and read every political news story from the North as further evidence of the planned destruction of the southern way of life. The climax came a decade after Calhoun's death with the election of Republican Abraham Lincoln in 1860, which led immediately to the secession of South Carolina, followed by six other Southern states. They formed the new Confederate States, which, in accord with Calhoun's theory, did not have any political parties.[79]

Concurrent majority

Calhoun's basic concern for protecting the diversity of minority interests is expressed in his chief contribution to political science—the idea of a concurrent majority across different groups as distinguished from a numerical majority.[80] According to the principle of a numerical majority, the will of the more numerous citizens should always rule, regardless of the burdens on the minority. Such a principle tends toward a consolidation of power in which the interests of the absolute majority always prevail over those of the minority. Calhoun believed that the great achievement of the American constitution was in checking the tyranny of a numerical majority through institutional procedures that required a concurrent majority, such that each important interest in the community must consent to the actions of government. To secure a concurrent majority, those interests that have a numerical majority must compromise with the interests that are in the minority. A concurrent majority requires a unanimous consent of all the major interests in a community, which is the only sure way of preventing tyranny of the majority. This idea supported Calhoun's doctrine of interposition or nullification, in which the state governments could refuse to enforce or comply with a policy of the Federal government that threatened the vital interests of the states.[81]

Historian Richard Hofstadter (1948, 2011) emphasizes that Calhoun's conception of minority was very different from the minorities of a century later:

Not in the slightest was [Calhoun] concerned with minority rights as they are chiefly of interest to the modern liberal mind – the rights of dissenters to express unorthodox opinions, of the individual conscience against the State, least of all of ethnic minorities. At bottom he was not interested in any minority that was not a propertied minority. The concurrent majority itself was a device without relevance to the protection of dissent, designed to protect a vested interest of considerable power ... it was minority privileges rather than [minority] rights that he really proposed to protect.[82]

Unlike Jefferson, Calhoun rejected attempts at economic, social, or political leveling, claiming that true equality could not be achieved if all classes were given equal rights and responsibilities. Rather, to ensure true prosperity, it was necessary for a stronger group to provide protection and care for the weaker one.[83] This meant that the two groups should not be equal before the law. For Calhoun, "protection" (order) was more important than freedom. Individual rights were something to be earned, not something bestowed by nature or God.[83] Calhoun was concerned with protecting the interests of the Southern States (which he identified with the interests of their slaveholding elites) as a distinct and beleaguered minority among the members of the federal Union. However his idea of a concurrent majority as a protection for minority rights has garnered a super-regional application in American political thought.[84][85]

Disquisition on Government

The Disquisition on Government is a 100-page abstract treatise of Calhoun's definitive and comprehensive ideas on government; he worked on it intermittently for six years until its 1849 completion.[86] It systematically presents his arguments that a numerical majority in any government will typically impose a despotism over a minority unless some way is devised to secure the assent of all classes, sections, and interests and, similarly, that innate human depravity would debase government in a democracy.[87]

Calhoun offered the concurrent majority as the key to achieving consensus, a formula by which a minority interest had the option to nullify objectionable legislation passed by a majority interest. The consensus would be effected by this tactic of nullification, a veto that would suspend the law within the boundaries of the state.[88][89]

Veto power was linked to the right of secession, which portended anarchy and social chaos. Constituencies would call for compromise to prevent this outcome.[90] With a concurrent majority in place, the U.S. Constitution as interpreted by the Federal Judiciary would no longer exert collective authority over the various states. According to the (Supremacy Clause) located in Article 6, laws made by the federal government are the "supreme law of the land" only when they are made "in pursuance" of the U.S. Constitution. The mechanisms for his system are convincing if one shares Calhoun's conviction that a functioning concurrent majority never leads to stalemate in the legislature; rather, talented statesmen, practiced in the arts of conciliation and compromise would pursue "the common good",[91] however explosive the issue. His formula promised to produce laws satisfactory to all interests. The ultimate goal of these mechanisms were to facilitate the authentic will of the white populace. Calhoun explicitly rejected the founding principles of equality in the Declaration of Independence, denying that humanity is born free and equal in shared human nature and basic needs. He regarded this precept as "the most false and dangerous of all political errors".[92] States could constitutionally take action to free themselves from an overweening government, but slaves as individuals or interest groups could not do so. Calhoun's stance assumed that with the establishment of a concurrent majority, interest groups would influence their own representatives sufficiently to have a voice in public affairs; the representatives would perform strictly as high-minded public servants. Under this scenario, the political leadership would improve and persist, corruption and demagoguery would subside, and the interests of the people would be honored. [93] This introduces the second theme in the Disquisition, and a counterpoint to his concept of the concurrent majority—political corruption.

Calhoun considered the concurrent majority essential to provide structural restraints to egocentric governance, as he believed, "a vast majority of mankind is entirely biased by motives of self-interest and that by this interest must be governed".[94] This innate selfishness, which he viewed as axiomatic, would inevitably emerge when government revenue became available to political parties for distribution as patronage. Politicians and bureaucrats would succumb to the lure of government lucre accumulated through taxation, tariff duties and public land sales. Even a diminishment of massive revenue effected through nullification by the permanent minority would not eliminate these temptations. A robust national defense – acknowledged by all interests as essential to national security—would require significant military expenditures. These funds alone would be sufficient to entice political leaders into abandoning the interests of their constituents in favor of serving personal and party interests.[95] Calhoun predicted that electioneering, political conspiracies, and outright fraud would be employed to mislead and distract a gullible public; inevitably, perfidious demagogues would come to rule the political scene. A decline in authority among the principal statesmen would follow, and, ultimately, the eclipse of the concurrent majority.[96]

Calhoun contended that however confused and misled the masses were by political opportunists, any efforts to impose majority rule upon a minority would be thwarted by a minority veto.[97] What Calhoun fails to explain, according to American historian William W. Freehling, is how a compromise would be achieved in the aftermath of a minority veto, when the ubiquitous demagogues betray their constituencies and abandon the concurrent majority altogether. Calhoun's two key concepts – the maintenance of the concurrent majority by high-minded statesmen on the one hand; and the inevitable rise of demagogues who undermine consensus on the other – are never reconciled or resolved in the Disquisition.[96]

South Carolina and other Southern states, in the three decades preceding the Civil War, provided legislatures in which the vested interests of land and slaves dominated in the upper houses, while the popular will of the numerical majority prevailed in the lower houses. There was little opportunity for demagogues to establish themselves in this political milieu – the democratic component among the people was too weak to sustain a plebeian politician. The conservative statesmen – the slaveholding gentry – retained control over the political apparatus.[98][99] Freehling described the state's political system of the era thus:

[T]he apportionment of [state] legislative seats gave the small majority of low country aristocrats control of the senate and a disproportionate influence in the house. Political power in South Carolina was uniquely concentrated in a legislature of large property holders who set state policy and selected the men to administer it. The characteristics of South Carolina politics cemented the control of upper class planters. Elections to the state legislature – the one control the masses could exert over the government – were often uncontested and rarely allowed the "plebeian" a clear choice between two parties or policies ...[98]

The Disquisition was published shortly after his death, as was another book, Discourse on the Constitution and Government of the United States.[100]

John C. Calhoun on the "concurrent majority" from his Disquisition (1850)

- "If the whole community had the same interests, so that the interests of each and every portion would be so affected by the action of the government, that the laws which oppressed or impoverished one portion, would necessarily oppress and impoverish all others – or the reverse – then the right of suffrage, of itself, would be all-sufficient to counteract the tendency of the government to oppression and abuse of its powers. ... But such is not the case. On the contrary, nothing is more difficult than to equalize the action of the government, in reference to the various and diversified interests of the community; and nothing more easy than to pervert its powers into instruments to aggrandize and enrich one or more interests by oppressing and impoverishing the others; and this too, under the operation of laws, couched in general terms – and which, on their face, appear fair and equal. ... Such being the case, it necessarily results, that the right of suffrage, by placing the control of the government in the community must ... lead to conflict among its different interests – each striving to obtain possession of its powers, as the means of protecting itself against the others – or of advancing its respective interests, regardless of the interests of others. For this purpose, a struggle will take place between the various interests to obtain a majority, in order to control the government. If no one interest be strong enough, of itself, to obtain it, a combination will be formed. ... [and] the community will be divided into two great parties – a major and minor – between which there will be incessant struggles on the one side to retain, and on the other to obtain the majority – and, thereby, the control of the government and the advantages it confers."[101]

State Sovereignty and the "Calhoun Doctrine"

In the 1840s three interpretations of the Constitutional powers of Congress to deal with slavery in territories emerged: the "free-soil doctrine", the "Calhoun doctrine", and "popular sovereignty". The Free Soilers said Congress had the power to outlaw slavery in the territories. The popular sovereignty position said the voters living there should decide. The Calhoun doctrine said Congress could never outlaw slavery in the territories.[102]

In what historian Robert R. Russell calls the "Calhoun Doctrine", Calhoun argued that the Federal Government's role in the territories was only that of the trustee or agent of the several sovereign states: it was obliged not to discriminate among the states and hence was incapable of forbidding the bringing into any territory of anything that was legal property in any state. Calhoun argued that citizens from every state had the right to take their property to any territory. Congress, he asserted, had no authority to place restrictions on slavery in the territories.[103] As Constitutional historian Hermann von Holst noted, "Calhoun's doctrine made it a solemn constitutional duty of the United States government and of the American people to act as if the existence or non-existence of slavery in the Territories did not concern them in the least."[104] The Calhoun Doctrine was vehemently opposed by the Free Soil forces, which merged into the new Republican Party around 1854.[105] Chief Justice Roger B. Taney based his decision in the 1857 Supreme Court case Dred Scott v. Sandford, in which he ruled that the federal government could not prohibit slavery in any of the territories, upon Calhoun's arguments.[106]

John Quincy Adams concluded in 1821 that "Calhoun is a man of fair and candid mind, of honorable principles, of clear and quick understanding, of cool self-possession, of enlarged philosophical views, and of ardent patriotism. He is above all sectional and factious prejudices more than any other statesman of this Union with whom I have ever acted."[107] Historian Charles Wiltse noted Calhoun's evolution, "Though he is known today primarily for his sectionalism, Calhoun was the last of the great political leaders of his time to take a sectional position—later than Daniel Webster, later than Henry Clay, later than Adams himself."[108]

Film and television

The 1997 film Amistad depicts the controversy and legal battle surrounding the status of slaves who in 1839 rebelled against their transporters on La Amistad slave ship. Calhoun is portrayed in the film by Arliss Howard.[109]

Legacy

Calhoun is often remembered for his defense of minority rights by use of the "concurrent majority".[110][111] He is also noted and criticized for his strong defense of slavery. His views played an enormous role in influencing Southern secessionist leaders.[83]

Lake Calhoun, a lake of the Chain of Lakes in Minneapolis, was named after Calhoun by surveyors sent by Calhoun as Secretary of War to map the area around Fort Snelling in 1817.[112]

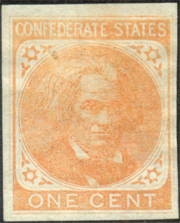

The Confederate government honored Calhoun on a one-cent postage stamp, which was printed in 1862 but was never officially released.[113]

Calhoun is the namesake of John C. Calhoun Community College in Decatur, Alabama. Calhoun was also honored by his alma mater, Yale University, which named one of its undergraduate residential colleges "Calhoun College". A sculpture of Calhoun appears on the exterior of Harkness Tower, a prominent campus landmark. The Clemson University campus in South Carolina occupies the site of Calhoun's Fort Hill plantation, which he bequeathed to his wife and daughter. They sold it and its 50 slaves to a relative. They received $15,000 for the 1,100 acres (450 ha) and $29,000 for the slaves (they were valued at about $600 apiece). When that owner died, Thomas Green Clemson foreclosed the mortgage. He later bequeathed the property to the state for use as an agricultural college to be named after him.[114]

Many different places, streets and schools were named after Calhoun, as may be seen on the above list. The "Immortal Trio" were memorialized with streets in Uptown New Orleans. Calhoun Landing, on the Santee-Cooper River in Santee, South Carolina, was named after him. In 1887, a monument to Calhoun was erected in Marion Square in Charleston. However, it was not well-liked by the residents and was replaced in 1896 by a different monument still in existence.[115] The USS John C. Calhoun, in commission from 1963 to 1994, was a Fleet Ballistic Missile nuclear submarine.[116]

In the wake of a racially-motivated Charleston church shooting in South Carolina in 2015, there emerged a movement to remove monuments dedicated to prominent pro-slavery and Confederate States figures. In June, the monument to Calhoun in Charleston was found vandalized, with spray-painted references to Calhoun's attitudes towards blacks and slavery.[117]

In July a group of Yale students requested in a petition that Yale rename the Calhoun College, one of the University's twelve residential colleges.[118] According to an April 2016 article in the New York Times, Yale President Peter Salovey announced that "despite decades of vigorous alumni and student protests," Calhoun's name will remain on a Yale residential dormitory.[119] In the article Calhoun was described as the United States' "most egregious racist" and "an avowed white supremacist."[119] Salovey explained as he announced the contentious decision—that it is preferable for Yale students to live in Calhoun's "shadow" so they will be "better prepared to rise to the challenges of the present and the future." He claimed that if they removed Calhoun's name, it would "obscure" his "legacy of slavery rather than addressing it."[119]

References

- ^ "Calhoun, John C." Oxford Dictionaries. Retrieved May 29, 2016.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Coit 1950, pp. 70–71.

- ^ Miller 1996, pp. 115–116.

- ^ Ford 1988, pp. 405–424.

- ^ "The 'Famous Five'". US Senate. March 12, 1959. Retrieved June 4, 2016.

- ^ Coit 1950, p. 3.

- ^ Wiltse 1944, pp. 15–24.

- ^ Niven 1993, p. 20.

- ^ Capers 1960, pp. 1–2.

- ^ Calhoun & Post 1995, p. xii.

- ^ Douglas 2009, p. 368.

- ^ Wiltse 1944, pp. 25–39.

- ^ Coit 1950, p. 42.

- ^ Her branch of the family spelled the surname differently from his. See A. S. Salley, The Calhoun Family of South Carolina.Columbia. 1906. p. 19. The name appears in various records as "Colhoon", "Cohoon", "Calhoun", "Cahoun", "Cohoun", "Calhoon", and "Colhoun". Ibid., pp. 1, 2, 5, 6, 18, 19. In Scotland it is spelt "Colquhoun". Ellen R. Johnson, Colquhoun/Calhoun and Their Ancestral Homelands (Heritage Books, 1993), passim.

- ^ a b c d "Floride Bonneau Colhoun Calhoun". Clemson University. Retrieved March 17, 2016.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Anna Maria Calhoun Clemson Clemson University. Retrieved May 14, 2016.

- ^ Wilson (2003) p. 254

- ^ "All Souls History and Archives". All Souls Church Unitarian. Retrieved May 30, 2016.

- ^ a b Roesch, James Rutledge. (August 25, 2015). "John C. Calhoun and "State's Rights"". The Abbeville Review. Retrieved April 26, 2016.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Calhoun 2003, pp. 254–255.

- ^ Peterson 1988, p. 27.

- ^ Perkins 1961, p. 359.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "John C. Calhoun, 7th Vice President (1825–1832)". United States Senate. Retrieved May 7, 2016.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Ellis 2009, pp. 75–76.

- ^ Stagg 2012.

- ^ Walters 1945.

- ^ Langguth 2006, pp. 375, 387.

- ^ Wiltse 1944, pp. 103–105.

- ^ Phillips 1929, 3:412-14.

- ^ Jewett 1908, p. 143.

- ^ Meigs 1917, Vol. 1, p. 221.

- ^ Meigs 1917, Vol. 2, p. 8.

- ^ Peterson 1988, pp. 280, 408.

- ^ Hofstadter 2011, p. 96.

- ^ Kirk 2001, p. 168.

- ^ Preyer 1959.

- ^ a b Long, Thomas, Jr. "Jackson vs. Calhoun—Part 2". The Ohio State University. Retrieved January 22, 2016.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Fitzgerald 1996.

- ^ Satz 1974, pp. 2–7.

- ^ Prucha 1997, p. 155.

- ^ Belko 2004, pp. 170–197.

- ^ Hogan, Margaret A. John Quincy Adams: Campaigns and Elections Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Retrieved January 3, 2016.

- ^ Vice President of the United States (President of the Senate): The Individuals United States Senate. Retrieved May 1, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e Bartlett 1994.

- ^ "Report Prepared for the Committee on Federal Relations of the Legislature of South Carolina, at its Session in November, 1831", in The Works of John C. Calhoun, Vol. VI. p. 96. Crallé, R.K. ed. (1888) D. Appleton.

- ^ Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions (1798) Bill of Rights Institute. Retrieved January 6, 2016.

- ^ Rutland 1997, pp. 248–249.

- ^ Calhoun 1992, pp. 348–49.

- ^ Niven 1993, p. 173.

- ^ Daniel Walker Howe, What hath God wrought: the transformation of America, 1815-1848 (Oxford University Press, 2007) pp 405-6

- ^ Howe, What hath God wrought: the transformation of America, 1815-1848 (2007) pp 406-10

- ^ John C Calhoun: Against the Force Bill. University of Missouri. Retrieved May 17, 2016.

- ^ Marszalek 2000, p. 84.

- ^ Marszalek 2000, p. 121.

- ^ a b Phillips 1929.

- ^ "Calhoun resigns vice presidency". A&E Television. Retrieved December 26, 2011.

- ^ Ashworth 1995, p. 203.

- ^ Martin Van Buren-The independent treasury. Advameg, Inc. Retrieved April 13, 2016.

- ^ a b John C. Calhoun Clemson University. Retrieved January 9, 2016.

- ^ James K. Polk: Campaigns and Elections: The Campaign and Election of 1844. University of Virginia Miller Center. Retrieved May 4, 2016.

- ^ "John Tyler: Domestic Affairs". University of Virginia Miller Center. Retrieved June 2, 2016.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ The Oregon Territory, 1846 United States Department of State. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- ^ Mexican War GlobalSecurity.org. Retrieved December 29, 2015.

- ^ a b "Wilmot Proviso". U.S. History.com. Retrieved April 1, 2016.

- ^ John C Calhoun: A Secessionist (Letter from Anna E. Carroll, to Edward Everett.) July 13, 1861. The New York Times. Retrieved May 1, 2016.

- ^ Today in History: March 18, 1782 (John C. Calhoun) Library of Congress. Retrieved March 27, 2016.

- ^ Barney 2011, p. 304.

- ^ Calhoun's Moving Grave Charleston Footprints. January 7, 2014. Retrieved March 17, 2016.

- ^ Cheek 2004, p. 8.

- ^ "Wilmot Proviso". Net Industries. Retrieved June 6, 2016.

- ^ Bartlett 1994, p. 218.

- ^ Bartlett 1994, p. 228.

- ^ Wilson, Clyde. (June 26, 2014). "John C. Calhoun and Slavery as a "Positive Good:" What he Said". Abbeville Institute. Retrieved June 6, 2016.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Bartlett 1994, p. 227.

- ^ Calhoun 1837, p. 34. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFCalhoun1837 (help)

- ^ Ford 1988.

- ^ Calhoun 1999, p. 68.

- ^ Durham 2008, p. 104.

- ^ Michael Perman (2012). The Southern Political Tradition. LSU Press. p. 11.

- ^ Ford 1994, pp. 19–58.

- ^ Kirk, Russell. (March 17, 2015). "John C. Calhoun Vindicated". The Abbeville Institute. Retrieved May 18, 2016.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Hofstadter 2011, p. 90–91.

- ^ a b c "John C. Calhoun: He started the Civil War". Historynet. June 12, 2006. Retrieved May 1, 2016.

- ^ Baskin 1969.

- ^ Kateb 1969.

- ^ Bartlett 1994, pp. 351–55.

- ^ Freehling 1965, pp. 25–42.

- ^ Coit 1950, pp. 150–151.

- ^ Krannawitter 2008, p. 171.

- ^ Krannawitter 2008, p. 174.

- ^ Coit 1950, p. 147.

- ^ Krannawitter 2008, pp. 166–167.

- ^ Krannawitter 2008, pp. 170–171.

- ^ Coit 1950, p. 149.

- ^ Freehling 1965, pp. 221–222.

- ^ a b Freehling 1965, p. 223.

- ^ Freehling 1965, p. 222.

- ^ a b Freehling 1965, pp. 225–226.

- ^ Varon 2008, pp. 91–92.

- ^ Calhoun 1851.

- ^ Polin & Polin 2006, p. 380.

- ^ Fehrenbacher 1981, pp. 64–65.

- ^ Russell 1966.

- ^ von Holst, Hermann E. (1883) John C. Calhoun. Houghton Mifflin and Company. p. 312

- ^ Foner 1995, p. 178.

- ^ Brophy 1990.

- ^ Adams 1848, V, p. 361.

- ^ Wiltse 1944, p. 234.

- ^ "Stephen Spielberg's "Amistad" (1997)". University of Missouri-Kansas City. Retrieved June 18, 2016.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Kuic 1983, p. 482.

- ^ "The decision-making process in this country resembles John Calhoun's 'concurrent majority': A large number of groups both within and outside the government must, in practice, approve any major policy." Jewell, Malcolm E. (2015) Senatorial Politics and Foreign Policy.University Press of Kentucky. p 2.

- ^ Brueggemann, Gary. Perspective on the Namesake of Lake Calhoun Star Tribune. Retrieved May 15, 2016.

- ^ Kaufmann, Patricia A. Calhoun Legacy American Stamp Dealer. Retrieved May 1, 2016.

- ^ Fort Hill History Clemson University. Retrieved May 5, 2016.

- ^ "Marion Square". National Park Service. Retrieved June 20, 2016.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ USS John C. Calhoun (SSBN 630) Navysite. Retrieved May 15, 2016.

- ^ John C. Calhoun statue vandalized in downtown Charleston WHNS. June 23, 2015. Retrieved May 11, 2016.

- ^ "To the Yale Administration", Yale students, 2015, retrieved April 30, 2016

- ^ a b c Glenmore, Glenda Elizabeth (April 30, 2016), "At Yale, a Right That Doesn't Outweigh a Wrong", New York Times, New Haven

Sources

- Ashworth, John (1995). Slavery, Capitalism, and Politics in the Antebellum Republic: Volume 1, Commerce and Compromise, 1820–1850. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-47487-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Barney, William L. (2011). The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Civil War. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-978201-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bartlett, Irving (1994). John C. Calhoun: A Biography. W. W. Norton, Incorporated. ISBN 978-0-393-33286-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Baskin, Darryl (1969). "The Pluralist Vision of John C. Calhoun". Polity. 2 (1): 49–65. doi:10.2307/3234088. JSTOR 3234088.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Belko, William S. (2004). "John C. Calhoun and the Creation of the Bureau of Indian Affairs: An Essay on Political Rivalry, Ideology, and Policymaking in the Early Republic". South Carolina Historical Magazine. Vol. 105, no. 3. South Carolina Historical Society. pp. 170–197.

{{cite magazine}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Brophy, Alfred L. (1990). "Let Us Go Back and Stand upon the Constitution: Federal-State Relations in Scott v. Sandford". Columbia Law Review. 90 (1): 192–225. doi:10.2307/1122839. ISSN 0010-1958.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Capers, Gerald M. (1960). John C. Calhoun, Opportunist: A Reappraisal. University of Florida Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) online edition - Cheek, H. Lee (2004). Calhoun and Popular Rule: The Political Theory of the Disquisition and Discourse. University of Missouri Press. ISBN 978-0-8262-1548-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Coit, Margaret L. (1950). John C. Calhoun: American Portrait. Houghton, Mifflin. ISBN 0-87797-185-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Douglas, Bradburn (2009). The Citizenship Revolution: Politics and the Creation of the American Union, 1774–1804. University of Virginia Press. ISBN 978-0-8139-3031-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Durham, David I. (2008). A Southern Moderate in Radical Times: Henry Washington Hilliard, 1808–1892. LSU Press. ISBN 978-0-8071-3422-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ellis, James H. (2009). A Ruinous and Unhappy War: New England and the War of 1812. Algora Publishing. ISBN 978-0-87586-691-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Fehrenbacher, Don Edward (1981). Slavery, Law, and Politics: The Dred Scott Case in Historical Perspective. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-502883-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Fitzgerald, Michael S. (1996). "Rejecting Calhoun's Expansible Army Plan: the Army Reduction Act of 1821". War in History. 3 (2): 161–185. doi:10.1177/096834459600300202.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Foner, Eric (June 1, 1995). Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men: The Ideology of the Republican Party before the Civil War: With a new Introductory Essay. OUP USA. ISBN 978-0-19-509497-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ford, Lacy K., Jr (1988). "Republican Ideology in a Slave Society: The Political Economy of John C. Calhoun". Journal of Southern History. 54. JSTOR 2208996.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Ford, Lacy K., Jr (1994). "Inventing the Concurrent Majority: Madison, Calhoun, and the Problem of Majoritarianism in American Political Thought". The Journal of Southern History. 60 (1): 19–58. JSTOR 2210719.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Freehling, William W. (1965). "Spoilsmen and Interests in the Thought and Career of John C. Calhoun". Journal of American History. 52: 25–42. JSTOR 1901122.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hofstadter, Richard (2011). "John C. Calhoun: The Marx of the Master Class". The American Political Tradition: And the Men Who Made it. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. pp. 87–118. ISBN 978-0-307-80966-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Jewett, James C. (1908). "The United States Congress of 1817 and Some of its Celebrities". The William and Mary Quarterly. 17 (2): 139. doi:10.2307/1916057. ISSN 0043-5597.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kateb, George (1969). "The Majority Principle: Calhoun and His Antecedents". Political Science Quarterly. 84 (4): 583–605. doi:10.2307/2147126. JSTOR 2147126.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kirk, Russell (2001). The Conservative Mind: From Burke to Eliot. Regnery Pub. ISBN 978-0-89526-171-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Krannawitter, Thomas L. (2008). Vindicating Lincoln: Defending the Politics of Our Greatest President. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 0-7425-5972-6.