St. Augustine, Florida

St. Augustine

San Agustín (Spanish) | |

|---|---|

| City of St. Augustine | |

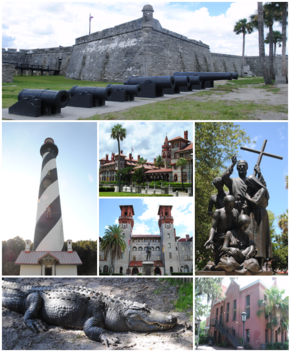

Top, left to right: Castillo de San Marcos, St. Augustine Light, Flagler College, Lightner Museum, statue near the Cathedral Basilica of St. Augustine, St. Augustine Alligator Farm Zoological Park, Old St. Johns County Jail | |

| Nickname(s): Ancient City, Old City | |

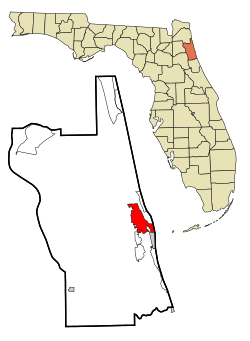

Location in St. Johns County and the U.S. state of Florida | |

| Coordinates: 29°53′41″N 81°18′52″W / 29.89472°N 81.31444°W[1] | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Florida |

| County | St. Johns |

| Established | September 8, 1565 |

| Founded by | Pedro Menéndez de Avilés |

| Named for | Saint Augustine of Hippo |

| Government | |

| • Type | Commissioner-Manager |

| • Mayor | Nancy Sikes-Kline |

| • Vice Mayor | Roxanne Horvath |

| • Commissioners | Barbara Blonder, Cynthia Garris, and Jim Springfield |

| • City Manager | David Birchim |

| • City Clerk | Darlene Galambos |

| Area | |

• City | 12.85 sq mi (33.29 km2) |

| • Land | 9.52 sq mi (24.66 km2) |

| • Water | 3.33 sq mi (8.63 km2) |

| Elevation | 0 ft (0 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• City | 14,329 |

| • Density | 1,504.99/sq mi (581.05/km2) |

| • Urban | 69,173 (US: 399th) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP code(s) | 32080, 32084, 32085, 32086, 32095, 32082, 32092 |

| Area code | 904 |

| FIPS code | 12-62500[4] |

| GNIS feature ID | 0308101[3] |

| Website | City of St. Augustine |

St. Augustine (/ˈɔːɡəstiːn/ AW-gə-steen; Template:Lang-es [san aɣusˈtin]) is a city in and the county seat of St. Johns County located 40 miles (64 km) south of downtown Jacksonville. The city is on the Atlantic coast of northeastern Florida. Founded in 1565 by Spanish explorers, it is the oldest continuously inhabited European-established settlement in what is now the contiguous United States.

St. Augustine was founded on September 8, 1565, by Spanish admiral Pedro Menéndez de Avilés, Florida's first governor. He named the settlement San Agustín, for his ships bearing settlers, troops, and supplies from Spain had first sighted land in Florida eleven days earlier on August 28, the feast day of St. Augustine.[5] The city served as the capital of Spanish Florida for over 200 years. It was designated as the capital of British East Florida when the colony was established in 1763; Great Britain returned Florida to Spain in 1783.

Spain ceded Florida to the United States in 1819, and St. Augustine was designated one of the two alternating capitals of the Florida Territory, the other being Pensacola, upon ratification of the Adams–Onís Treaty in 1821. The Florida National Guard made the city its headquarters that same year. The territorial government moved and made Tallahassee the permanent capital of Florida in 1824.[6]

St. Augustine is part of Florida's First Coast region and the Jacksonville metropolitan area. Since the late 19th century, St. Augustine's distinctive historical character has made the city a tourist attraction. Castillo de San Marcos, the city's 17th-century Spanish fort—constructed out of the sedimentary rock coquina—continues to attract tourists.[7]

History

Kingdom of Spain 1565–1763

Kingdom of Great Britain 1763–1784

New Spain 1784–1821

United States 1821–1861

Confederate States 1861–1862

United States 1862–present

Early exploration

The first European known to have explored the coasts of Florida was the Spanish explorer and governor of Puerto Rico, Juan Ponce de León, who likely ventured in 1513 as far north as the vicinity of the future St. Augustine, naming the peninsula he believed to be an island "La Florida" and claiming it for the Spanish crown.[8][9]

Founding by Pedro Menéndez de Avilés

Founded in 1565 by the Spanish conquistador Pedro Menéndez de Avilés, St. Augustine is the oldest continuously occupied settlement of European origin in the contiguous United States.[10][11] It is the second-oldest continuously inhabited city of European origin in a United States territory, after San Juan, Puerto Rico (founded in 1521).[12]

In 1560, King Philip II of Spain appointed Menéndez as Captain General, and his brother Bartolomé Menéndez as Admiral, of the Fleet of the Indies.[13] Thus Pedro Menéndez commanded the galleons of the great Armada de la Carrera, or Spanish Treasure Fleet, on their voyage from the Caribbean and Mexico to Spain, and determined the routes they followed.

In early 1564, he asked permission to go to Florida to search for La Concepcion, the galeon Capitana, or flagship, of the New Spain fleet commanded by his son, Admiral Juan Menéndez. The ship had been lost in September 1563 when a hurricane scattered the fleet as it was returning to Spain, at the latitude of Bermuda off the coast of South Carolina.[14] The crown repeatedly refused his request.

The crown eventually approached Menéndez to fit out an expedition to Florida[15] on the condition that he explore and settle the region as King Philip's adelantado, and eliminate the Huguenot French,[16] whom the Catholic Spanish considered to be dangerous heretics.[17]

Menéndez was in a race to reach Florida before the French captain Jean Ribault,[18] who was on a mission to secure Fort Caroline. On August 28, 1565, the feast day of St. Augustine of Hippo, Menéndez's crew finally sighted land; the Spaniards continued sailing northward along the coast from their landfall, investigating every inlet and plume of smoke along the shore. On September 4, they encountered four French vessels anchored at the mouth of a large river (the St. Johns), including Ribault's flagship, La Trinité. The two fleets met in a brief skirmish, but it was not decisive. Menéndez sailed southward and landed again on September 8, formally declared possession of the land in the name of Philip II, and officially founded the settlement he named San Agustín (Saint Augustine).[19][20] Father Francisco López de Mendoza Grajales, the chaplain of the expedition, celebrated the first Thanksgiving Mass on the grounds.[21][22][23] The formal Franciscan outpost, Mission Nombre de Dios, was founded at the landing point, perhaps the first mission in what would become the continental United States.[24]

The mission served nearby villages of the Mocama, a Timucua group, and was at the center of an important chiefdom in the late 16th and 17th century. The settlement was built in the former Timucua village of Seloy; this site was chosen for its strategic location facing the waterways of St. Augustine bay with their abundant resources, an eminently suitable site for water communications and defense.[25]

A French attack on St. Augustine was thwarted by a violent squall that ravaged the French naval forces. Taking advantage of this, Menéndez marched his troops overland to Fort Caroline on the St. Johns River, about 30 miles (50 km) north. The Spanish easily overwhelmed the lightly defended French garrison, which had been left with only a skeleton crew of 20 soldiers and about 100 others, killing most of the men and sparing about 60 women and children. The bodies of the victims were hung in trees with the inscription: "Hanged, not as Frenchmen, but as "Lutherans" (heretics)".[26][27] Menéndez renamed the fort San Mateo and marched back to St. Augustine, where he discovered that the shipwrecked survivors from the French ships had come ashore to the south of the settlement. A Spanish patrol encountered the remnants of the French force, and took them prisoner. Menéndez accepted their surrender, but then executed all of them except a few professing Catholics and some Protestant workers with useful skills, at what is now known as Matanzas Inlet (Matanzas is Spanish for "slaughters").[28] The site is very near the national monument Fort Matanzas, built in 1740–1742 by the Spanish.

Invasions by pirates and enemies of Spain

Succeeding governors of the province maintained a peaceful coexistence with the local Native Americans, allowing the isolated outpost of St. Augustine some stability for a few years. On May 28 and 29, 1586, soon after the Anglo-Spanish War began between England and Spain, the English privateer Sir Francis Drake sacked and burned St. Augustine.[29] The approach of his large fleet obliged Governor Pedro Menéndez Márquez and the townspeople to evacuate the settlement. When the English got ashore, they seized some artillery pieces and a royal strongbox containing gold ducats (which was the garrison payroll).[30] The killing of their sergeant major by the Spanish rearguard caused Drake to order the town razed to the ground.[31][32]

In 1609 and 1611, expeditions were sent out from St. Augustine against the English colony at Jamestown.[33] In the second half of the 17th century, groups of Indians from the colony of Carolina conducted raids into Florida and killed the Franciscan priests who served at the Catholic missions. Requests by successive governors of the province to strengthen the presidio's garrison and fortifications were ignored by the Spanish Crown which had other priorities in its vast empire. The charter of 1663 for the new Province of Carolina, issued by King Charles II of England, was revised in 1665, claiming lands as far southward as 29 degrees north latitude, about 65 miles south of the existing settlement at St. Augustine.[34][35][36]

The English buccaneer Robert Searle sacked St. Augustine in 1668, after capturing some Spanish supply vessels bound for the settlement and holding their crews at gun point while his men hid below decks. Searle was retaliating for the Spanish destruction of the settlement of New Providence in the Bahamas. Searle and his men killed sixty people and pillaged public storehouses, churches and houses.[37] This raid and the establishment of the English settlement at Charles Town spurred the Spanish Crown to finally acknowledge the vulnerability of St. Augustine to foreign incursions and strengthen the city's defenses. In 1669, Queen Regent Mariana ordered the Viceroy of New Spain to disburse funds for the construction of a permanent masonry fortress, which began in 1672.[38] Before the fortress was completed, French buccaneers Michel de Grammont and Nicolas Brigaut planned an ill-fated attack in 1686 which was foiled: their ships were run aground, Grammont and his crew were lost at sea, and Brigaut was captured ashore by Spanish soldiers.[39] The Castillo de San Marcos was completed in 1695, not long before an attack by James Moore's forces from Carolina in November, 1702. Failing to capture the fort after a siege of 58 days, the British set St. Augustine ablaze as they retreated.[40]

In 1738, the governor of Spanish Florida, Manuel de Montiano, ordered a settlement be constructed two miles north of St. Augustine for the growing Free Black community established by fugitive slaves who had escaped into Florida from the Thirteen Colonies. This new community, Fort Mose, would serve as a military outpost and buffer for St. Augustine, as the men accepted into Fort Mose had enlisted in the colonial militia and converted to Catholicism in exchange for their freedom.[41][42]

In 1740, however, St. Augustine was again besieged, this time by the governor of the British colony of Georgia, General James Oglethorpe, who was also unable to take the fort.[43]

Loyalist haven under British rule

The 1763 Treaty of Paris, signed after Great Britain's victory over France and Spain during the Seven Years' War, ceded Florida to Great Britain in exchange for the return of Havana and Manila. The vast majority of Spanish colonists in the region left Florida for Cuba, Florida became Great Britain's fourteenth and fifteenth North American colonies, and because of the political sympathies of its British inhabitants, St. Augustine became a Loyalist haven during the American Revolutionary War.[44]

After the mass exodus of St. Augustinians, Great Britain sought to repopulate its new colony. The London Board of Trade advertised 20,000-acre lots to any group that would settle in Florida within ten years, with one resident per 100 acres. Pioneers who were "energetic and of good character" were given 100 acres of land and 50 additional acres for each family member they brought. Under Governor James Grant, almost three million acres of land were granted in East Florida alone. Second stories were added to existing Spanish homes and new houses were built. Cattle ranching and plantation agriculture began to thrive.[45]

During the twenty-year period of British rule, Britain took command of both the Castillo de San Marcos (renamed Fort St. Mark) and of Fort Matanzas. They permanently stationed a small group of men at Fort Matanzas. Once war broke out, loyalist St. Augustine residents burned effigies of Patriots Samuel Adams and John Hancock in the plaza. Fort St. Mark became a training and supply base, as well as a prisoner-of-war camp where three signers of the Declaration of Independence and South Carolina's lieutenant governor Christopher Gadsden were held. Local militias composed of Florida, Georgia, and Carolina inhabitants formed the East Florida Rangers in 1776 and were reorganized to form the King's Rangers in 1779.[45] Spanish General Bernardo de Gálvez, harassed the British in West Florida and captured Pensacola. Fears that the Spanish would then move to capture St. Augustine, however, proved unfounded.[46]

The 1783 Treaty of Paris, which recognized the independence of the Thirteen Colonies as the United States, ceded Florida back to Spain and returned the Bahamas to Britain. As a result, some of the town's Spanish residents returned to St Augustine. Refugees from Dr. Andrew Turnbull's troubled colony in New Smyrna had fled to St. Augustine in 1777, made up the majority of the city's population during the period of British rule, and remained when the Spanish Crown took control again. This group was, and still is, referred to locally as "Menorcans", even though it also included settlers from Italy, Corsica and the Greek islands.[47][48]

Second Spanish period

During the Second Spanish period (1784–1821) of Florida, Spain was dealing with invasions of the Iberian peninsula by Napoleon's armies in the Peninsular War, and struggled to maintain a tenuous hold on its territories in the western hemisphere as revolution swept South America. The royal administration of Florida was neglected, as the province had long been regarded as an unprofitable backwater by the Crown. The United States, however, considered Florida vital to its political and military interests as it expanded its territory in North America, and maneuvered by sometimes clandestine means to acquire it.[49] On October 5, 1811, a hurricane hit St. Augustine that caused extensive damage to the city. The damage was further exacerbated by the economic situation of Spanish Florida.[50] The Adams–Onís Treaty, negotiated in 1819 and ratified in 1821, ceded Florida and St. Augustine, still its capital at the time, to the United States.[51]

Territory of Florida

According to the Adams–Onís Treaty, the United States acquired East Florida and absolved Spain of $5 million of debt. Spain renounced all claims to West Florida and the Oregon Country. Andrew Jackson returned to Florida in 1821, upon ratification of the treaty, and established a new territorial government. Americans from older plantation societies of Virginia, Georgia, and the Carolinas began to move to the area. West Florida was quickly consolidated with East and the new capital of Florida became Tallahassee, halfway between the old capitals of St. Augustine and Pensacola, in 1824.[52]

Once many Americans had begun to immigrate to the new territory, it became apparent that there would be continued skirmishes with local Creek and Miccosukee peoples and white settlers encroaching on their land. The United States government favored removal policies, but local indigenous groups in Florida refused to leave without fighting. The nineteenth century saw three Seminole Wars. In 1823, territorial governor William Duval and James Gadsden signed the Treaty of Moultrie Creek, forcing Seminoles onto a four million acre reservation in central Florida. The Second Seminole War (1835–1842) was the longest war of Indian removal and resulted when the United States government attempted to move the Seminole people from Central Florida to a Creek reservation west of the Mississippi River. As a result of the Seminole War, Seminole prisoners, including the prominent leader Osceola, were held captive in the Castillo de San Marcos, renamed Fort Marion after General Francis Marion, who fought in the American Revolution, in the 1830s.[52][53][54]

By 1840, the territory's population had reached 54,477 people. Half the population were enslaved Africans. Steamboats were popular on the Apalachicola and St. Johns Rivers, and there were several plans for railroad construction. The territory south of present-day Gainesville was sparsely populated by whites.[52]

In 1845 the Florida Territory was admitted into the Union as the State of Florida.[55]

Civil War

On January 7, 1861, only three days before Florida would secede and join the Confederacy, a group of 125 Florida militia marched on Fort Marion. The fort was guarded by a single sergeant, who surrendered the fort after being provided with a receipt. Gen. Robert E. Lee, who was commander of coastal defenses at the time, ordered that the fort's cannons be removed and sent to more strategic locations, such as Fernandina and the mouth of the St. Johns River.[56]

The town raised a Confederate militia unit, known as the Florida Independent Blues or the Saint Augustine Blues.[57] They were soon joined by the Milton Guard, another militia unit.[58]

In an effort to help blockade runners avoid capture, the Confederate government ordered all lighthouses to be extinguished. In St. Augustine, the customhouse officer, Paul Arnau, organized the "Coastal Guard", a group who worked to disable the lighthouses along Florida's east coast. They started by removing and hiding the lenses from the St. Augustine Light before moving south. After successfully dismantling the lighthouses at Cape Canaveral, Jupiter Inlet, and Key Biscayne, Arnau returned to St. Augustine. He would then serve as mayor from 1861 until early 1862, just before the Federals took over the city.[59]

The Confederate authorities remained in control of St. Augustine for fourteen months, although it was barely defended. The Union conducted a blockade of shipping. In 1862 Union troops gained control of St. Augustine and controlled it through the rest of the war. With the economy already suffering, many residents fled.[60][61]

Henry Flagler and the railroad

Henry Flagler, a co-founder with John D. Rockefeller of the Standard Oil Company, spent the winter of 1883 in St. Augustine and found the city charming, but considered its hotels and transportation systems inadequate.[62] He had the idea to make St. Augustine a winter resort for wealthy Americans from the north, and to bring them south he bought several short line railroads and combined these in 1885 to form the Florida East Coast Railway. He built a railroad bridge over the St. Johns River in 1888, opening up the Atlantic coast of Florida to development.[63][64]

Flagler finished construction in 1887 on two large ornate hotels in the city, the 450-room Hotel Ponce de Leon and the 250-room Hotel Alcazar. The next year, he purchased the Casa Monica Hotel (renaming it the Cordova Hotel) across the street from both the Alcazar and the Ponce de Leon. His chosen architectural firm, Carrère and Hastings, radically altered the appearance of St. Augustine with these hotels, giving it a skyline and beginning an architectural trend in the state characterized by the use of the Spanish Renaissance Revival and Moorish Revival styles. With the opening of the Ponce de Leon in 1888, St. Augustine became the winter resort of American high society for a few years.[65]

When Flagler's Florida East Coast Railroad was extended southward to Palm Beach and then Miami in the early 20th century, the wealthy stopped in St. Augustine en route to the southern resorts. Wealthy vacationers began to customarily spend their winters in South Florida, where the climate was warmer and freezes were rare. St. Augustine nevertheless still attracted tourists, and eventually became a destination for families traveling in automobiles as new highways were built and Americans took to the road for annual summer vacations. The tourist industry soon became the dominant sector of the local economy.[66]

Civil Rights Movement

In 1963, nearly a decade after the Supreme Court ruling in Brown v. Board of Education that segregation of schools was unconstitutional, African Americans were still trying to get St. Augustine to integrate the public schools in the city. They were also trying to integrate public accommodations, such as lunch counters,[67] and were met with arrests[68] and Ku Klux Klan violence.[69][70] Local students held protests throughout the city, including sit-ins at the local Woolworth's, picket lines, and marches through the downtown. These protests were often met with police violence. Homes of African Americans were firebombed,[71] black leaders were assaulted and threatened with death, and others were fired from their jobs.

In the spring of 1964, St. Augustine civil rights leader Robert Hayling[72] asked the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and its leader Martin Luther King Jr. for assistance.[73] From May until July 1964, King and Hayling, along with Hosea Williams, C. T. Vivian, Dorothy Cotton, Andrew Young and others, organized marches, sit-ins, pray-ins, wade-ins and other forms of protest in St. Augustine. Hundreds of black and white civil rights supporters were arrested,[74] and the jails were filled to capacity.[75] At the request of Hayling and King, civil rights supporters from elsewhere, including students, clergy, activists and well-known public figures, came to St. Augustine and were arrested together.[76][77][78]

St. Augustine was the only place in Florida where King was arrested; his arrest there occurred on June 11, 1964, on the steps of the Monson Motor Lodge's restaurant. The demonstrations came to a climax when a group of black and white protesters jumped into the hotel's segregated swimming pool. In response to the protest, James Brock, the manager of the hotel and the president of the Florida Hotel & Motel Association, poured muriatic acid into the pool to scare the protesters. Photographs of this, and of a policeman jumping into the pool to arrest the protesters, were broadcast around the world. One appeared on the front page of the Washington paper the day the senate went to vote on the passage of the landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964. It became the most famous photograph ever taken in St. Augustine.

The Ku Klux Klan and its supporters responded to these protests with violent attacks that were widely reported in national and international media.[79] Popular revulsion against the Klan and police violence in St. Augustine generated national sympathy for the black protesters and became a key factor in Congressional passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,[80] leading eventually to passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965,[81] both of which provided federal enforcement of constitutional rights.

St. Augustine's historically Black college, now Florida Memorial University, felt itself unwelcome in St. Augustine, and departed in 1968 for a new campus near Opa-locka in Dade County. It is currently located in the Opa-locka North neighborhood of Miami Gardens, next to St. Thomas University.[82]

Modern St. Augustine

In 1965, St. Augustine celebrated the 400th anniversary of its founding,[83] and jointly with the State of Florida, inaugurated a program to restore part of the colonial city. The Historic St. Augustine Preservation Board was formed to reconstruct more than thirty-six buildings to their historical appearance, which was completed within a few years. When the State of Florida abolished the Board in 1997, the City of St. Augustine assumed control of the reconstructed buildings, as well as other historic properties including the Government House. In 2010, the city transferred control of the historic buildings to UF Historic St. Augustine, Inc., a direct support organization of the University of Florida.

Cross and Sword was a 1965 play by American playwright Paul Green created to honor the 400th anniversary of the settlement of St. Augustine. It was Florida's official state play, having received the designation by the Florida Senate in 1973.[84] It was performed for ten weeks every summer in St. Augustine for more than 30 years, closing in 1996.[85] [86][87][88]

In 2015, St. Augustine celebrated the 450th anniversary of its founding with a four-day long festival and a visit from Felipe VI of Spain and Queen Letizia of Spain.[89]

On October 7, 2016 Hurricane Matthew caused widespread flooding in downtown St. Augustine.[90]

Geography and climate

St. Augustine is located at 29°53′41″N 81°18′52″W / 29.89472°N 81.31444°W (29.8946910, −81.3145170). According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 10.7 square miles (27.8 km2), 8.4 square miles (21.7 km2) of which is land and 2.4 square miles (6.1 km2) (21.99%) is water. Access to the Atlantic Ocean is via the St. Augustine Inlet of the Matanzas River.

St. Augustine has a humid subtropical climate (Cfa) typical of the Gulf and South Atlantic states. The low latitude and coastal location give the city a mostly warm and sunny climate. Unlike much of the contiguous United States, St. Augustine's driest time of year is winter. The hot and wet season extends from May through October, while the cool and dry season extends November through April.

In summer, average high temperatures are in the lower 90's F (32 C) and normal low temperatures are in the 70's F (20 - 22 C). The Bermuda High pumps in hot and unstable tropical air from the Bahamas and Gulf of Mexico, which help create the daily thundershowers that are typical in summer months. Intense but very brief downpours are common in summer in the city. Fall and spring are warm and sunny with highs from 74 °F to 87 °F and lows in the 50s to 70s.

In winter, St. Augustine has generally mild and sunny weather typical of the Florida peninsula. The coolest months are from December through February, with highs from 67 °F to 70 °F and lows from 47 °F to 51 °F. From November through April, St. Augustine often has long periods of rainless weather. April can see near drought conditions with brush fires and water restrictions in place. St. Augustine averages 4.6 frosts per year. The record low of 10 °F (−12 °C) happened on January 21, 1985. Hurricanes occasionally impact the region; however, like most areas prone to such storms, St. Augustine rarely suffers a direct hit by a major hurricane. The last direct hit by a major hurricane to the city was Hurricane Dora in 1964. Extensive flooding occurred in the downtown area of St. Augustine when Hurricane Matthew passed east of the city in October 2016.[91]

| Climate data for St. Augustine, Florida (St. Augustine Light), 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1973–2016 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 86 (30) |

87 (31) |

93 (34) |

95 (35) |

98 (37) |

101 (38) |

103 (39) |

101 (38) |

99 (37) |

94 (34) |

89 (32) |

86 (30) |

103 (39) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 80.0 (26.7) |

81.8 (27.7) |

84.9 (29.4) |

88.6 (31.4) |

93.3 (34.1) |

95.9 (35.5) |

97.6 (36.4) |

96.0 (35.6) |

92.8 (33.8) |

89.0 (31.7) |

84.2 (29.0) |

81.1 (27.3) |

98.5 (36.9) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 67.5 (19.7) |

69.7 (20.9) |

74.4 (23.6) |

79.8 (26.6) |

85.1 (29.5) |

88.6 (31.4) |

91.0 (32.8) |

89.9 (32.2) |

87.4 (30.8) |

81.8 (27.7) |

74.9 (23.8) |

68.9 (20.5) |

79.9 (26.6) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 57.6 (14.2) |

60.0 (15.6) |

64.5 (18.1) |

70.2 (21.2) |

76.3 (24.6) |

80.4 (26.9) |

82.4 (28.0) |

82.1 (27.8) |

80.3 (26.8) |

74.2 (23.4) |

66.2 (19.0) |

60.1 (15.6) |

71.2 (21.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 47.8 (8.8) |

50.2 (10.1) |

54.6 (12.6) |

60.6 (15.9) |

67.4 (19.7) |

72.3 (22.4) |

73.8 (23.2) |

74.2 (23.4) |

73.1 (22.8) |

66.5 (19.2) |

57.5 (14.2) |

51.3 (10.7) |

62.4 (16.9) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 28.1 (−2.2) |

32.1 (0.1) |

36.9 (2.7) |

44.6 (7.0) |

55.6 (13.1) |

64.8 (18.2) |

68.1 (20.1) |

68.6 (20.3) |

64.0 (17.8) |

49.0 (9.4) |

39.1 (3.9) |

31.4 (−0.3) |

25.6 (−3.6) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 10 (−12) |

21 (−6) |

23 (−5) |

34 (1) |

41 (5) |

52 (11) |

59 (15) |

61 (16) |

54 (12) |

36 (2) |

29 (−2) |

16 (−9) |

10 (−12) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 2.74 (70) |

2.69 (68) |

3.43 (87) |

2.93 (74) |

3.66 (93) |

6.27 (159) |

4.88 (124) |

7.18 (182) |

7.18 (182) |

4.37 (111) |

2.32 (59) |

2.99 (76) |

50.64 (1,286) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 9.4 | 7.8 | 8.6 | 6.8 | 7.2 | 12.3 | 11.6 | 15.0 | 13.5 | 9.1 | 8.1 | 8.4 | 117.8 |

| Source: NOAA (mean maxima/minima 1981–2010)[92][93] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1830 | 1,708 | — | |

| 1840 | 2,450 | 43.4% | |

| 1850 | 1,934 | −21.1% | |

| 1860 | 1,914 | −1.0% | |

| 1870 | 1,717 | −10.3% | |

| 1880 | 2,293 | 33.5% | |

| 1890 | 4,742 | 106.8% | |

| 1900 | 4,272 | −9.9% | |

| 1910 | 5,494 | 28.6% | |

| 1920 | 6,192 | 12.7% | |

| 1930 | 12,111 | 95.6% | |

| 1940 | 12,090 | −0.2% | |

| 1950 | 13,555 | 12.1% | |

| 1960 | 14,734 | 8.7% | |

| 1970 | 12,352 | −16.2% | |

| 1980 | 11,985 | −3.0% | |

| 1990 | 11,692 | −2.4% | |

| 2000 | 11,592 | −0.9% | |

| 2010 | 12,975 | 11.9% | |

| 2020 | 14,329 | 10.4% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[94] | |||

| Race | Pop 2010[95] | Pop 2020[96] | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White (NH) | 10,443 | 11,275 | 80.49% | 78.69% |

| Black or African American (NH) | 1,460 | 1,136 | 11.25% | 7.93% |

| Native American or Alaska Native (NH) | 46 | 40 | 0.35% | 0.28% |

| Asian (NH) | 155 | 246 | 1.19% | 1.72% |

| Pacific Islander or Native Hawaiian (NH) | 10 | 7 | 0.08% | 0.05% |

| Some other race (NH) | 19 | 53 | 0.15% | 0.37% |

| Two or more races/Multiracial (NH) | 186 | 523 | 1.43% | 3.65% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 656 | 1,049 | 5.06% | 7.32% |

| Total | 12,975 | 14,329 |

As of the 2020 United States census, there were 14,329 people, 5,828 households, and 3,072 families residing in the city.[97]

In 2020, 2.2% of the population were under 5 years old, 8.7% under 18 years old, and 25.5% were 65 years and over. 57.9% of the population were female.[98]

In 2020, the median value of owner-occupied housing units was $294,600. The median gross rent was $1,118. 91.2% of households had a computer and 83.0% of households had a broadband internet subscription.[98]

In 2020, 93.8% of the population 25 years and older had a high school degree or higher and 37.4% of that same population had a bachelor's degree or higher.[98]

In 2020, the median household income was $60,455. The per capita income was $33,060. 17.0% lived below the Poverty threshold.[98]

There were 1,230 veterans living in the city between 2016 and 2020, and 6.6% of the population were foreign born persons.[98]

As of the 2010 United States census, there were 12,975 people, 5,494 households, and 2,546 families residing in the city.[99]

Government and politics

St. Augustine is the county seat of St. Johns County, Florida.[100][101]

The city of St. Augustine operates under a city commission government, specifically the commissioner-manager form, with an elected mayor, vice mayor, and city commission. Additionally, the government includes a city manager, city attorney, city clerk, and various city boards.[102]

Transportation

Highways

Interstate 95 runs north–south.

Interstate 95 runs north–south. U.S. Route 1 runs north–south.

U.S. Route 1 runs north–south. State Road A1A runs north–south.

State Road A1A runs north–south. State Road 16 runs east–west

State Road 16 runs east–west State Road 207 runs northeast–southwest

State Road 207 runs northeast–southwest State Road 312 runs east–west

State Road 312 runs east–west

Buses

Bus service is operated by the Sunshine Bus Company, based in St. Augustine Beach.[103] Buses operate mainly between shopping centers across town, but a few go to Hastings and Jacksonville, where one can connect to JTA for additional service across Jacksonville.

Airport

St. Augustine has one public airport 4 miles (6.4 km) north of the downtown. It has three runways and two seaplane lanes.[104]

Rail

The Florida East Coast Railway runs through St. Augustine. Passenger service to the city ended in 1968. First Coast Commuter Rail is a project to establish commuter rail services between Jacksonville and St. Augustine.

Points of interest

First and second Spanish eras

- Avero House

- Castillo de San Marcos National Monument

- Fort Matanzas National Monument

- Fort Mose Historic State Park

- Nombre de Dios

- Gonzalez-Alvarez House

- Fountain of Youth Archaeological Park

- The Spanish Military Hospital Museum

- St. Francis Barracks

- Colonial Quarter

- Ximenez-Fatio House

- González-Jones House

- Llambias House

- Oldest Wooden Schoolhouse

- Tolomato Cemetery and Huguenot Cemetery

British era

Pre-Flagler era

Flagler era

- Ponce de Leon Hotel

- Casa Monica Hotel

- Hotel Alcazar

- Zorayda Castle

- Bridge of Lions

- Old St. Johns County Jail

- Ripley's Believe it or Not! Museum located in 1887 mansion of William Worden.

- St. Augustine Alligator Farm Zoological Park

Historic churches

- Grace United Methodist Church

- Cathedral Basilica of St. Augustine

- Memorial Presbyterian Church

- Trinity Church of St. Augustine

Lincolnville National Historic District – Civil Rights era

Other points of interest

- Anastasia State Park

- Florida School for the Deaf and Blind

- Great Cross

- St. Augustine Amphitheatre

- St. Augustine Aquarium

- St. Augustine Pirate & Treasure Museum

- Victory III, St. Augustine Scenic Cruise boat, since 1973

Culture

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (May 2023) |

Music

- The Wobbly Toms (2003), band

Education

Primary and secondary education in St. Augustine is overseen by the St. Johns County School District.

There are four zoned elementary schools with sections of the city limits in their attendance boundaries: John A. Crookshank (outside the city limits),[105] R. B. Hunt,[106] Ketterlinus,[107] and Osceola (outside the city limits).[108] There are two zoned middle schools (both outside the city limits): R. J. Murray Middle School,[109] and Sebastian Middle School.[110] There are no county high schools located within St. Augustine's current city limits, but St. Augustine High School is the designated senior high school for residentially-zoned land in St. Augustine.[111] Additionally Pedro Menendez High School, and St. Johns Technical High School are located in the vicinity.

The Florida School for the Deaf and Blind, a state-operated boarding school for deaf and blind students, was founded in the city in 1885.[112] The Catholic Diocese of St. Augustine operates the St. Joseph Academy, Florida's oldest Catholic high school, to the west of the city.[113]

There are several institutions of higher education in and around St. Augustine. Flagler College is a four-year liberal arts college founded in 1968. It is located in the former Ponce de Leon Hotel in downtown St. Augustine.[114] St. Johns River State College, a state college in the Florida College System, has its St. Augustine campus just west of the city. Also in the area are the University of North Florida, Jacksonville University, and Florida State College at Jacksonville in Jacksonville.[115]

The institution now known as Florida Memorial University was located in St. Augustine from 1918 to 1968, when it relocated to its present campus in Miami Gardens. Originally known as Florida Baptist Academy, then Florida Normal, and then Florida Memorial College, it was a historically black institution and had a wide impact on St. Augustine while it was located there. During World War II it was chosen as the site for training the first blacks in the U. S. Signal Corps. Among its faculty members was Zora Neale Hurston; a historic marker was placed in 2003 at the house at 791 West King Street where she lived while teaching at Florida Memorial[116] (and where she completed her autobiography Dust Tracks on a Road.)[117][118]

-

St. Augustine High School is not in the city limits, but is the zoned high school of St. Augustine

-

Ketterlinus Elementary School is one of two public elementary schools in the St. Augustine city limits.

-

Florida School for the Deaf and Blind is a statewide K-12 school for the deaf and blind in St. Augustine

Notable people

- Andrew Anderson, physician, St. Augustine mayor

- Jorge Biassou, Haitian revolutionary and black Spanish general

- Richard Boone, actor

- Albert Boyd, member of National Aviation Hall of Fame

- James Branch Cabell, novelist

- Doug Carn, jazz musician

- Cris Carpenter, major league baseball pitcher

- Ray Charles, pianist, singer, composer

- George J. F. Clarke, Surveyor General of Spanish East Florida

- Nicholas de Concepcion, escaped slave who became a Spanish privateer and pirate captain

- Earl Cunningham, artist

- Alexander Darnes, born a slave, became a well-known physician

- Edmund Jackson Davis, governor of Texas

- Kathleen Deagan, archaeologist

- Frederick Delius, composer

- Frederick Dent, general and brother-in-law of Ulysses Grant

- Audrey Nell Edwards, civil rights hero

- Henry Flagler, industrialist

- Willie Galimore, football star

- Michael Gannon, historian

- William H. Gray, U.S. congressman and president of the United Negro College Fund

- Martin Davis Hardin, Union General in the Civil War

- Robert Hayling, civil rights leader

- Martin Johnson Heade, artist

- Zora Neale Hurston, novelist and folklorist

- Willie Irvin, Philadelphia Eagles football player

- Stetson Kennedy, author and human rights activist

- Scott Lagasse, race car driver

- Scott Lagasse Jr., race car driver

- Jacob Lawrence, artist

- William W. Loring, Confederate general

- Albert Manucy, historian, author, Fulbright Scholar

- Howell W. Melton, United States district judge

- Prince Achille Murat, nephew of Napoleon Bonaparte

- Andrew Nagorski, journalist and author

- David Nolan, author and historian

- Osceola, Seminole War leader (held prisoner at Fort Marion, now Castillo de San Marcos)

- Verle A. Pope, state legislator

- Richard Henry Pratt, soldier and educator

- Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings, novelist

- Marcus Roberts, musician

- Gamble Rogers, folk singer

- John M. Schofield, Union general

- Edmund Kirby Smith, Confederate general

- Bill Snowden, race car driver

- Steve Spurrier, college/pro (American) football coach

- Felix Varela, Cuban national hero

- Augustin Verot, first Bishop of St. Augustine

- Patty Wagstaff, member of National Aviation Hall of Fame

- DeWitt Webb, physician, St. Augustine mayor, state representative

- David Levy Yulee, first Jewish U.S. Senator, Levy County and Yulee, Florida namesake

- Agustin V. Zamorano, pioneer printer and provisional governor of California

Sister cities

St. Augustine's sister cities are:[119]

Avilés, Spain

Avilés, Spain Cartagena, Colombia

Cartagena, Colombia Menorca, Spain

Menorca, Spain Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic

Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic

Gallery

-

Bell tower on northeast bastion of the Castillo de San Marcos

-

North bastions and wall of the Castillo, looking eastward toward Anastasia Island

-

Seawall south of the Castillo

-

The city gates of St. Augustine, built in 1808, part of the much older Cubo Line

-

The Government House. East wing of the building dates to the 18th-century structure built on original site of the colonial governor's residence.[120]

-

Facade of the Roman Catholic Cathedral of St. Augustine

-

Shrine of Our Lady of La Leche at Mission Nombre de Dios

-

Statue of Ponce de León

-

The former Hotel Alcazar now houses the Lightner Museum and City Hall

-

Flagler College, formerly the Ponce de Leon Hotel

-

Bridge of Lions, looking eastward to Anastasia Island

-

Tolomato Cemetery

See also

- Gálveztown (brig sloop) – ship which played a role in the Gulf Coast campaign of the American Revolutionary War under Bernardo de Gálvez, and its replica built recently in Spain anticipating the 450th anniversary of St. Augustine's founding (1565–2015).

- St. Augustine movement

References

- ^ "GNIS Detail – Saint Augustine". geonames.usgs.gov. Geographic Names Information System. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 31, 2021.

- ^ a b "US Board on Geographic Names". geonames.usgs.gov. United States Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Archived from the original on February 12, 2012. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". census.gov. United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ Hennesey, James J. (December 10, 1981). American Catholics: A History of the Roman Catholic Community in the United States: A History of the Roman Catholic Community in the United States. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-19-802036-3. Archived from the original on May 3, 2016. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ^ Montès, Christian (2014). American Capitals: A Historical Geography. University of Chicago Press. p. 132. ISBN 978-0-226-08051-2.

- ^ Staff (April 10, 2020). "Coquina | The rock that saved St. Augustine)". www.nps.gov. Archived from the original on March 4, 2021. Retrieved December 6, 2022.

- ^ Steigman, Jonathan D. (September 25, 2005). La Florida Del Inca and the Struggle for Social Equality in Colonial Spanish America. University of Alabama Press. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-8173-5257-8.

- ^ Lawson, Edward W. (June 1, 2008). The Discovery of Florida and Its Discoverer Juan Ponce de Leon (Reprint of 1946 ed.). Kessinger Publishing. pp. 29–32. ISBN 978-1-4367-0883-8.

- ^ "Florida: St. Augustine Town Plan Historic District". nps.gov. National Park Service. Archived from the original on April 30, 2015. Retrieved May 27, 2015.

- ^ "Not So Fast, Jamestown: St. Augustine Was Here First". NPR. Archived from the original on November 5, 2019. Retrieved November 5, 2019.

- ^ Thompson, Linda (May 30, 2014). Exploring The Territories of the United States. Britannica Digital Learning. p. 34. ISBN 978-1-62513-185-0.

- ^ Lowery, Woodbury (1911). The Spanish settlements within the present limits of the United States: Florida, 1562-1574. G.P. Putnam. p. 144.

- ^ Turner, Sam (July 18, 2015). "Menéndez anguishes in prison as son is lost at sea". Tallahassee Democrat. Archived from the original on January 31, 2016. Retrieved August 9, 2020.

- ^ Pickett, Margaret F.; Pickett, Dwayne W. (2011). The European Struggle to Settle North America: Colonizing Attempts by England, France and Spain, 1521–1608. McFarland. p. 84. ISBN 978-0-7864-6221-6.

- ^ Lowery 1911, p.100

- ^ Lowery 1911, p.105

- ^ Lyon, Eugene (1991). "Pedro Menéndez de Avilés". In Mormino, Gary (ed.). Spanish Pathways in Florida: 1492-1992/Los Caminos Espanoles En LA Florida 1492-1992 (in English and Spanish). Ann L Henderson (1st ed.). Pineapple Press Inc. p. 100. ISBN 978-1-56164-003-4. Retrieved November 20, 2012.

- ^ Eugene Lyon (May 1983). The Enterprise of Florida: Pedro Menendez de Aviles and the Spanish Conquest Of, 1565-1568. University Press of Florida. pp. 112–115. ISBN 978-0-8130-0777-9.

- ^ William S. Coker (1993). "The Missions of Florida, 1513-1763". The Spanish Missionary Heritage of the United States: Selected Papers and Commentaries from the November 1990 Quincentenary Symposium. United States Department of the Interior|National Park Service. p. 26.

- ^ Verne Elmo Chatelain (1941). The Defenses of Spanish Florida, 1565 to 1763. Carnegie Institution of Washington. p. 41.

- ^ Amy Turner Bushnell (1987). Situado and Sabana: Spain's Support System for the Presidio and Mission Provinces of Florida. University of Georgia Press. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-8203-1712-0.

- ^ Buescher, John B. (May 13, 2014). "America's First Mass". Catholicworldreport.com. Catholic World Report. Archived from the original on December 14, 2019. Retrieved August 10, 2020.

- ^ Herreros, Mauricio Spiritual Florida: A Guide to Retreat Centers and Religious Sites in Florida, p. 25

- ^ Deagan, Kathleen (2008). Historical Archaeology at the Fountain of Youth Park Site (PDF). pp. 1, 3, 11.

The site faces the confluence of the old St. Augustine inlet, the entrance to the Matanzas River to the south and the entrance to the Tolomato (or North River) to the north. Such a position offered not only a series of rich ecotones, but also an excellent site for water travel, communication and defense.

- ^ René Goulaine de Laudonnière (1853). L'histoire notable de la Floride: situèe es Indes Occidentales. P. Jannet. pp. 218–219. Retrieved November 22, 2012.

- ^ Francois Marie Arouet Voltaire (1773). Essais sur les Moeurs et l'esprit des Nations. p. 75.

- ^ Henderson, Richard R.; United States. National Park Service (March 1989). A Preliminary inventory of Spanish colonial resources associated with National Park Service units and national historic landmarks, 1987. United States Committee, International Council on Monuments and Sites, for the U.S. Dept. of the Interior, National Park Service. p. 87. ISBN 9780911697032. Retrieved November 20, 2012.

- ^ Tucker, Spencer (November 21, 2012). Almanac of American Military History. ABC-CLIO. p. 54. ISBN 978-1-59884-530-3. Archived from the original on February 26, 2017. Retrieved October 6, 2016.

- ^ Sugden, John (April 24, 2012). Sir Francis Drake. Random House. p. 198. ISBN 978-1-4481-2950-8. Archived from the original on February 26, 2017. Retrieved October 6, 2016.

- ^ Konstam, Angus (December 20, 2011). The Great Expedition: Sir Francis Drake on the Spanish Main 1585–86. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 109. ISBN 978-1-78096-233-7. Archived from the original on February 26, 2017. Retrieved October 6, 2016.

- ^ Raab, James W. (November 5, 2007). Spain, Britain and the American Revolution in Florida, 1763–1783. McFarland. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-7864-3213-4. Archived from the original on February 26, 2017. Retrieved October 6, 2016.

- ^ Gallay, Alan (June 11, 2015). Colonial Wars of North America, 1512–1763 (Routledge Revivals): An Encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. p. 326. ISBN 978-1-317-48718-0. Archived from the original on February 26, 2017. Retrieved October 6, 2016.

- ^ "Charter of Carolina – March 24, 1663". avalon.law.yale.edu. Lillian Goldman Law Library, Yale Law School. 2008. Archived from the original on February 7, 2009. Retrieved February 10, 2016.

- ^ "Charter of Carolina – June 30, 1665". Avalon Law. Lillian Goldman Law Library, Yale Law School. 2008. Archived from the original on January 24, 2009. Retrieved May 3, 2023.

- ^ Edgar, Walter B. (1998). South Carolina: A History. University of South Carolina Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-57003-255-4. Archived from the original on February 26, 2017. Retrieved October 6, 2016.

- ^ Latimer, Jon (June 1, 2009). Buccaneers of the Caribbean: How Piracy Forged an Empire. Harvard University Press. p. 198. ISBN 978-0-674-03403-7. Archived from the original on July 31, 2016. Retrieved October 6, 2016.

- ^ Raab, James W. (November 5, 2007). Spain, Britain and the American Revolution in Florida, 1763–1783. McFarland. pp. 10–11. ISBN 978-0-7864-3213-4. Archived from the original on February 27, 2017. Retrieved October 6, 2016.

- ^ Marley, David (2010). Pirates of the Americas. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781598842012. Retrieved September 12, 2017.

- ^ Edgar, Walter B. (1998). South Carolina: A History. University of South Carolina Press. p. 93. ISBN 978-1-57003-255-4. Archived from the original on February 27, 2017. Retrieved October 6, 2016.

- ^ "Fort Mose". Florida Museum. August 9, 2017. Retrieved May 21, 2021.

- ^ Landers, Jane (February 27, 2019). "What Catholic Church records tell us about America's earliest black history". The Conversation. Retrieved May 21, 2021.

- ^ Baine, Rodney E. (2000). "General James Oglethorpe and the Expedition Against St. Augustine". The Georgia Historical Quarterly. 84 (2 Summer). Georgia Historical Society: 198. JSTOR 40584271.

- ^ Griffin, Patricia C. (1991). Mullet on the Beach: The Minorcans of Florida, 1768–1788. St. Augustine Historical Society. p. 108. ISBN 978-0-8130-1074-8. Archived from the original on December 24, 2016. Retrieved October 6, 2016.

- ^ a b Augustine (2018). "The British Period (1763–1784): Castillo de San Marcos National Monument (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Archived from the original on June 16, 2019. Retrieved June 18, 2019.

- ^ "The British Period (1763–1784) – Fort Matanzas National Monument". U.S. National Park Service. Archived from the original on October 6, 2017. Retrieved June 18, 2019.

- ^ Landers, Jane G. (2000). Colonial Plantations and Economy in Florida. University Press of Florida. pp. 41–42. ISBN 978-0-8130-1772-3. Archived from the original on July 31, 2016. Retrieved October 6, 2016.

- ^ Griffin, Patricia C. (1991). Mullet on the Beach: The Menorcans of Florida, 1768–1788. St. Augustine Historical Society. pp. 14–21. ISBN 978-0-8130-1074-8.

- ^ Writers' Program (Fla.) (1940). Seeing Fernandina: A Guide to the City and Its Industries. Fernandina News Publishing Company. p. 23. Archived from the original on September 3, 2018. Retrieved May 3, 2013.

- ^ Johnson, Sherry (Summer 2005). "The St. Augustine Hurricane of 1811: Disaster and the Question of Political Unrest on the Florida Frontier". The Florida Historical Quarterly. 84 (1): 28, 41.

- ^ Crutchfield, James A.; Moutlon, Candy; Terry Del Bene (March 26, 2015). The Settlement of America: An Encyclopedia of Westward Expansion from Jamestown to the Closing of the Frontier. Routledge. p. 51. ISBN 978-1-317-45461-8. Archived from the original on February 26, 2017. Retrieved October 6, 2016.

- ^ a b c "Territorial Period – Florida Department of State". dos.myflorida.com. Archived from the original on March 5, 2019. Retrieved June 18, 2019.

- ^ "Seminole Incarceration". National Park Service. Retrieved May 16, 2022.

- ^ Wickman, Patricia Riles (2006). Osceola's Legacy. University of Alabama Press. pp. 101–102. ISBN 978-0-8173-5332-2.

- ^ Stathis, Stephen W. (January 2, 2014). Landmark Legislation 1774–2012: Major U.S. Acts and Treaties. SAGE Publications. p. 78. ISBN 978-1-4522-9229-8. Archived from the original on February 26, 2017. Retrieved October 6, 2016.

- ^ Omega, G. East (October 1952). "St. Augustine during the Civil War". The Florida Historical Quarterly. 31 (2): 75–76. Retrieved June 30, 2022.

- ^ Ethier, Eric (2011). The Big Book of Civil War Sites: From Fort Sumter to Appomattox, a Visitor's Guide to the History, Personalities, and Places of America's Battlefields. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 407. ISBN 978-0-7627-6632-1.

- ^ Bittle, George (October 1972). "Florida Prepares for War, 1860-1861" (PDF). The Florida Historical Quarterly. 51 (2): 144. Retrieved July 16, 2022.

- ^ Redd, Robert (2014). St. Augustine and the Civil War (e-book ed.). Charleston, SC: The History Press. p. 18. ISBN 9781625846570.

- ^ Mattick, Barbara E. (2003). "The Catholic Nuns of St. Augustine (1859–1869)". In Clayton, Bruce; Salmond, John A. (eds.). Lives Full of Struggle and Triumph: Southern Women, Their Institutions, and Their Communities. University Press of Florida. p. 117. ISBN 978-0-8130-3117-0. Archived from the original on February 27, 2017. Retrieved October 6, 2016.

- ^ Taylor, Paul (2001). Discovering the Civil War in Florida: A Reader and Guide. Pineapple Press Inc. p. 127. ISBN 978-1-56164-235-9. Archived from the original on July 31, 2016. Retrieved October 6, 2016.

- ^ Sidney Walter Martin (February 1, 2010). Florida's Flagler. University of Georgia Press. p. 130. ISBN 978-0-8203-3488-2. Archived from the original on February 26, 2017. Retrieved October 6, 2016.

- ^ Cox, Jim (February 24, 2016). Rails Across Dixie: A History of Passenger Trains in the American South. McFarland. p. 85. ISBN 978-0-7864-6175-2. Archived from the original on February 26, 2017. Retrieved October 6, 2016.

- ^ Manley, Walter W.; Brown, E. Canter; Rise, Eric W.; Florida Supreme Court Historical Society (1997). The Supreme Court of Florida and Its Predecessor Courts, 1821–1917. University Press of Florida. p. 263. ISBN 978-0-8130-1540-8. Archived from the original on February 26, 2017. Retrieved October 6, 2016.

- ^ Sidney Walter Martin (February 1, 2010). Florida's Flagler. University of Georgia Press. pp. 117–118. ISBN 978-0-8203-3488-2. Archived from the original on February 27, 2017. Retrieved October 6, 2016.

- ^ Tourism USA: Guidelines for Tourism Development : Appraising Tourism Potential, Planning for Tourism, Assessing Product and Market, Marketing Tourism, Visitor Services, Sources of Assistance. The University of Missouri. 1991. p. 87. Archived from the original on February 26, 2017. Retrieved July 7, 2016.

- ^ Bullock, Charles S. III; Rozell, Mark J. (March 15, 2012). The Oxford Handbook of Southern Politics. Oxford University Press. p. 160. ISBN 978-0-19-538194-8. Archived from the original on July 31, 2016. Retrieved August 12, 2017.

- ^ "The Crisis". The New Crisis. The Crisis Publishing Company, Inc.: 412 1963. ISSN 0011-1422. Archived from the original on July 31, 2016.

- ^ Ramdin, Ron (2004). Martin Luther King, Jr. Haus Publishing. p. 88. ISBN 978-1-904341-82-6. Archived from the original on July 31, 2016. Retrieved August 12, 2017.

- ^ Jackson, Thomas F. (July 17, 2013). From Civil Rights to Human Rights: Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Struggle for Economic Justice. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 190. ISBN 978-0-8122-0000-3. Archived from the original on July 31, 2016. Retrieved August 12, 2017.

- ^ "FBI Report of 1964-02-08". OCLC. Federal Bureau of Investigation. p. 3. Archived from the original on July 6, 2008.

(redacted) St. Augustine, Florida, advised that what appeared to be a Molotov cocktail was thrown at the back of his house at the above address causing a serious fire.

- ^ Kirk, John (June 6, 2014). Martin Luther King Jr. Routledge. pp. 103–104. ISBN 978-1-317-87650-2. Archived from the original on July 31, 2016. Retrieved August 12, 2017.

- ^ Webb, Clive (August 15, 2011). Rabble Rousers: The American Far Right in the Civil Rights Era. University of Georgia Press. p. 169. ISBN 978-0-8203-4229-0. Archived from the original on July 31, 2016. Retrieved August 12, 2017.

- ^ Singleton, Dorothy M. (March 18, 2014). Unsung Heroes of the Civil Rights Movement and Thereafter: Profiles of Lessons Learned. UPA. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-7618-6319-9. Archived from the original on July 31, 2016. Retrieved August 12, 2017.

- ^ Goodwyn, Larry (January 1965). "Anarchy in St. Augustine". Harpers.org. Harper's Magazine. Archived from the original on April 21, 2015.

Sheriff Davis was beginning to use harsh treatment against demonstrators who were in jail. He would herd both men and women into a chain link pen in the yard in a 99-degree sun; he kept them there all day. Water was insufficient and there was no latrine. At night the prisoners were crowded in small cells without room to lie down.

- ^ Vorspan, Albert; Saperstein, David (1998). Jewish Dimensions of Social Justice: Tough Moral Choices of Our Time. UAHC Press. pp. 204–205. ISBN 978-0-8074-0650-2. Retrieved August 12, 2017.

- ^ Haynes, Stephen (November 8, 2012). The Last Segregated Hour: The Memphis Kneel-Ins and the Campaign for Southern Church Desegregation. Oxford University Press. p. 44. ISBN 978-0-19-539505-1. Archived from the original on July 31, 2016. Retrieved August 12, 2017.

- ^ Branch, Taylor (April 16, 2007). Pillar of Fire: America in the King Years 1963–65. Simon and Schuster. p. 606. ISBN 978-1-4165-5870-5. Archived from the original on July 31, 2016. Retrieved August 12, 2017.

- ^ Curtis, Nancy C. (August 1, 1998). Black Heritage Sites: The South. The New Press. p. 99. ISBN 978-1-56584-433-9. Archived from the original on July 31, 2016. Retrieved August 12, 2017.

- ^ Pitre, Merline; Glasrud, Bruce A. (March 20, 2013). Southern Black Women in the Modern Civil Rights Movement. Texas A&M University Press. p. 43. ISBN 978-1-60344-999-1. Archived from the original on July 31, 2016. Retrieved August 12, 2017.

- ^ Goldfield, David (December 7, 2006). Encyclopedia of American Urban History. SAGE Publications. p. 201. ISBN 978-1-4522-6553-7. Archived from the original on July 31, 2016. Retrieved August 12, 2017.

- ^ Marcof, Bianca (July 6, 2021). "Florida Memorial University fights for its future". The Miami Times. Retrieved February 18, 2023.

- ^ History News. Vol. 20–21. American Association for State and Local History. 1965. p. 208. Archived from the original on February 26, 2017. Retrieved July 7, 2016.

- ^ Florida State Symbols - The State Play: Cross and Sword Archived June 7, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ de Yampert, Rick (August 21, 2008). "Amped at the amphitheatre". Daytona Beach News-Journal Online. Retrieved September 7, 2008. [dead link]

- ^ Reinink, Amy (August 22, 2008). "St. Augustine gets amped". Ocala Star Banner. Retrieved September 7, 2008.

- ^ St. Augustine Amphitheatre - Venue - Specs Archived 2008-12-19 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Rajtar, Steve; Kelly Goodman (2008). A Guide to Historic St. Augustine, Florida. The History Press. pp. 52–53. ISBN 978-1-59629-336-6.

- ^ Gardner, Sheldon (July 16, 2015). "King and queen of Spain to visit St. Augustine in September". The St. Augustine Record. Archived from the original on October 9, 2016. Retrieved October 8, 2016.

- ^ Martin, Jake (8 October 2016). "Hurricane Matthew: Surveying damage in St. Augustine the morning after". The St. Augustine Record. Archived from the original on 9 October 2016. Retrieved 8 October 2016.

- ^ Braun, Michael (October 8, 2016). "Hurricane Matthew floods St. Augustine beach areas". (Fort Myers) News-Press. Retrieved October 8, 2016.

- ^ "NOWData - NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 24, 2021.

- ^ "Summary of Monthly Normals 1991-2020". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 24, 2021.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "P2 HISPANIC OR LATINO, AND NOT HISPANIC OR LATINO BY RACE - 2010: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) - St. Augustine city, Florida". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "P2 HISPANIC OR LATINO, AND NOT HISPANIC OR LATINO BY RACE - 2020: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) - St. Augustine city, Florida". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "S1101 HOUSEHOLDS AND FAMILIES - 2020: St. Augustine city, Florida". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ a b c d e "QuickFacts: St. Augustine city, Florida". www.census.gov. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved November 7, 2022.

- ^ "S1101 HOUSEHOLDS AND FAMILIES - 2010: St. Augustine city, Florida". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "St. Johns County questions Jacksonville branding proposal | Jax Daily Record". Financial News & Daily Record - Jacksonville, Florida. November 6, 2018. Archived from the original on November 5, 2019. Retrieved November 5, 2019.

- ^ "Find a County". naco.org. National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on May 31, 2011. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ^ "City Commission | St. Augustine, FL". www.citystaug.com. Retrieved March 19, 2021.

- ^ "Public Transportation | St. Augustine Beach Florida". www.staugbch.com.

- ^ "SGJ – Northeast Florida Regional Airport – SkyVector". skyvector.com. Archived from the original on May 14, 2015. Retrieved June 17, 2014.

- ^ "St. Johns County School Attendance Zones John A. Crookshank Elementary School" (PDF). St. Johns County School District. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 2, 2022. Retrieved August 1, 2022. - See index of maps

- ^ "St. Johns County School Attendance Zones R. B. Hunt Elementary School" (PDF). St. Johns County School District. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 2, 2022. Retrieved August 1, 2022. - See index of maps

- ^ "St. Johns County School Attendance Zones Ketterlinus Elementary School" (PDF). St. Johns County School District. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 2, 2022. Retrieved August 1, 2022. - See index of maps

- ^ "St. Johns County School Attendance Zones Osceola Elementary School" (PDF). St. Johns County School District. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 2, 2022. Retrieved August 1, 2022. - See index of maps

- ^ "St. Johns County School Attendance Zones R. J. Murray Middle School" (PDF). St. Johns County School District. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 2, 2022. Retrieved August 1, 2022. - See index of maps

- ^ "St. Johns County School Attendance Zones Sebastian Middle School" (PDF). St. Johns County School District. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 2, 2022. Retrieved August 1, 2022. - See index of maps

- ^ "Zoning Map". City of St. Augustine. Retrieved August 1, 2022.

Compare with the St. Augustin HS zoning map: "2022 - 2023 St. Johns County School Attendance Zones St. Augustine High School" (PDF). St. Johns County School District. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 2, 2022. Retrieved August 1, 2022. - ^ "Florida School for the Deaf and the Blind". fsdb.k12.fl.us. Archived from the original on April 3, 2007. Retrieved March 27, 2007.

- ^ "School is Tradition". The Florida Times-Union/Shorelines. February 13, 2003. Archived from the original on October 8, 2012. Retrieved May 18, 2011.

- ^ Reiss, Sarah W. (2009). Insiders' Guide to Jacksonville, 3rd Edition. Globe Pequot. p. 184. ISBN 978-0-7627-5032-0. Retrieved May 10, 2011.

- ^ Reiss, Sarah W. (2009). Insiders' Guide to Jacksonville, 3rd Edition. Globe Pequot. pp. 184–187. ISBN 978-0-7627-5032-0. Retrieved May 18, 2011.

- ^ Jolly, Margaretta (December 4, 2013). Encyclopedia of Life Writing: Autobiographical and Biographical Forms. Routledge. p. 450. ISBN 978-1-136-78744-7. Archived from the original on June 3, 2016. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ^ Robert Wayne Croft (January 1, 2002). A Zora Neale Hurston Companion. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 37–38. ISBN 978-0-313-30707-2. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ^ Bloom, Harold (January 1, 2009). Zora Neale Hurston. Infobase Publishing. pp. 38–39. ISBN 978-1-4381-1553-5. Archived from the original on April 24, 2016. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ^ "Sister Cities". citystaug.com. City of St. Augustine. Retrieved January 26, 2021.

- ^ Kornwolf, James D. (2002). Architecture and Town Planning in Colonial North America. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 87. ISBN 978-0-8018-5986-1.

Further reading

- Abbad y Lasierra, Iñigo, "Relación del descubrimiento, conquista y población de las provincias y costas de la Florida" – "Relación de La Florida" (1785); edición de Juan José Nieto Callén y José María Sánchez Molledo.

- Colburn, David, Racial Change and Community Crisis: St. Augustine, Florida, 1877–1980 (1985), New York: Columbia University Press.

- Corbett, Theodore G. (1974). "Migration to a Spanish Imperial Frontier in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries: St. Augustine". The Hispanic American Historical Review. 54 (3): 414–430. doi:10.2307/2512931. JSTOR 2512931.

- Deagan, Kathleen, Fort Mose: Colonial America's Black Fortress of Freedom (1995), Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

- Fairbanks, George R. (George Rainsford), History and antiquities of St. Augustine, Florida (1881), Jacksonville, Florida, H. Drew.

- Gannon, Michael V., The Cross in the Sand: The Early Catholic Church in Florida 1513–1870 (1965), Gainesville: University Presses of Florida.

- Goldstein, Holly Markovitz, "St. Augustine's "Slave Market": A Visual History," Southern Spaces, 28 September 2012.

- Gordon, Elsbeth, Florida's Colonial Architectural Heritage, University Press of Florida, 2002; Heart and Soul of Florida: Sacred Sites and Historic Architecture, University Press of Florida, 2013

- Graham, Thomas, The Awakening of St. Augustine, (1978), St. Augustine Historical Society

- Hanna, A. J., A Prince in Their Midst, (1946), Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

- Harvey, Karen, America's First City, (1992), Lake Buena Vista, Florida: Tailored Tours Publications.

- Harvey, Karen, St. Augustine Enters the Twenty-first Century, (2010), Virginia Beach, VA: The Donning Company.

- Landers, Jane, Black Society in Spanish Florida (1999), Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

- Lardner, Ring, Gullible's Travels, (1925), New York: Scribner's.

- Lyon, Eugene, The Enterprise of Florida, (1976), Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

- Manucy, Albert, Menendez, (1983), St. Augustine Historical Society.

- Marley, David F. (2005), "United States: St. Augustine", Historic Cities of the Americas, vol. 2, Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO, p. 627+, ISBN 978-1-57607-027-7

- McCarthy, Kevin (editor), The Book Lover's Guide to Florida, (1992), Sarasota, Florida: Pineapple Press.

- Nolan, David, Fifty Feet in Paradise: The Booming of Florida, (1984), New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

- Nolan, David, The Houses of St. Augustine, (1995), Sarasota, Florida: Pineapple Press.

- Porter, Kenneth W., The Black Seminoles: History of a Freedom-Seeking People, (1996), Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

- Reynolds, Charles B. (Charles Bingham), Old Saint Augustine, a story of three centuries, (1893), St. Augustine, Florida E. H. Reynolds.

- Torchia, Robert W., Lost Colony: The Artists of St. Augustine, 1930–1950, (2001), St. Augustine: The Lightner Museum.

- Turner, Glennette Tilley, Fort Mose, (2010), New York: Abrams Books.

- United States Commission on Civil Rights, 1965. Law Enforcement: A Report on Equal Protection in the South. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office.

- Warren, Dan R., If It Takes All Summer: Martin Luther King, the KKK, and States' Rights in St. Augustine, 1964, (2008), Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press.

- Waterbury, Jean Parker (editor), The Oldest City, (1983), St. Augustine Historical Society.

External links

Government resources

Local news media

- The St. Augustine Record/staugustine.com, the city's daily print and online newspaper

- Historic City News, daily online news journal

- St. Augustine, Florida

- 1565 establishments in New Spain

- Cities in Florida

- Cities in the Jacksonville metropolitan area

- Cities in St. Johns County, Florida

- County seats in Florida

- Former colonial and territorial capitals in the United States

- Populated coastal places in Florida on the Atlantic Ocean

- Populated places established in 1565

- Spanish Florida

![The Government House. East wing of the building dates to the 18th-century structure built on original site of the colonial governor's residence.[120]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/11/St_Aug_Govt_House_Museum01.jpg/360px-St_Aug_Govt_House_Museum01.jpg)