Annie Besant

Annie Besant | |

|---|---|

Annie Besant | |

| Born | 1 October 1847 |

| Died | 20 September 1933 (aged 85) |

| Nationality | British |

| Known for | Theosophist, women's rights activist, writer and orator |

| Political party | Indian National Congress |

| Movement | Indian independence movement |

| Spouse |

Frank Besant

(m. 1867; div. 1873) |

| Children | Arthur, Mabel |

| Part of a series on |

| Theosophy |

|---|

|

Annie Besant, née Wood (1 October 1847 – 20 September 1933) was a British socialist, theosophist, women's rights activist, writer, orator, and supporter of both Irish and Indian self-rule.

In 1867, Annie, at age 20, married Frank Besant, a clergyman, and they had two children. However, Annie's increasingly anti-religious views led to their legal separation in 1873.[1] She then became a prominent speaker for the National Secular Society (NSS), as well as a writer, and a close friend of Charles Bradlaugh. In 1877 they were prosecuted for publishing a book by birth control campaigner Charles Knowlton. The scandal made them famous, and Bradlaugh was subsequently elected M.P. for Northampton in 1880.

Thereafter, she became involved with union actions, including the Bloody Sunday demonstration and the London matchgirls strike of 1888. She was a leading speaker for both the Fabian Society and the Marxist Social Democratic Federation (SDF). She was also elected to the London School Board for Tower Hamlets, topping the poll, even though few women were qualified to vote at that time.

In 1890 Besant met Helena Blavatsky, and over the next few years her interest in theosophy grew, whilst her interest in secular matters waned. She became a member of the Theosophical Society and a prominent lecturer on the subject. As part of her theosophy-related work, she travelled to India. In 1898 she helped establish the Central Hindu College, and in 1922 she helped establish the Hyderabad (Sind) National Collegiate Board in Mumbai, India.[2] In 1902, she established the first overseas Lodge of the International Order of Co-Freemasonry, Le Droit Humain. Over the next few years she established lodges in many parts of the British Empire. In 1907 she became president of the Theosophical Society, whose international headquarters were, by then, located in Adyar, Madras, (Chennai).

She also became involved in politics in India, joining the Indian National Congress. When World War I broke out in 1914, she helped launch the Home Rule League to campaign for democracy in India, and dominion status within the British Empire. This led to her election as president of the India National Congress, in late 1917. In the late 1920s, Besant travelled to the United States with her protégé and adopted son Jiddu Krishnamurti, who she claimed was the new Messiah and incarnation of Buddha. Krishnamurti rejected these claims in 1929.[1] After the war, she continued to campaign for Indian independence and for the causes of theosophy, until her death in 1933.

She started the central Hindu school in Benares as a chief means of achieving her objective.

Early life

Annie Wood was born in 1847 in London into a middle-class family of Irish origin. She was proud of her heritage and supported the cause of Irish self-rule throughout her adult life. Her father died when she was five years old, leaving the family almost penniless. Her mother supported the family by running a boarding house for boys at Harrow School. However, she was unable to support Annie and persuaded her friend Ellen Marryat to care for her. Marryat made sure that she had a good education. Annie was given a strong sense of duty to society and an equally strong sense of what independent women could achieve.[3] As a young woman, she was also able to travel widely in Europe. There she acquired a taste for Roman Catholic colour and ceremony that never left her.

In 1867, at age twenty, she married 26-year-old clergyman Frank Besant (1840–1917), younger brother of Walter Besant. He was an evangelical Anglican who seemed to share many of her concerns.[3] On the eve of her marriage, she had become more politicised through a visit to friends in Manchester, who brought her into contact with both English radicals and the Manchester Martyrs of the Irish Republican Fenian Brotherhood,[4] as well as with the conditions of the urban poor.

Soon Frank became vicar of Sibsey in Lincolnshire. Annie moved to Sibsey with her husband, and within a few years they had two children, Arthur and Mabel; however, the marriage was a disaster. As Annie wrote in her Autobiography, "we were an ill-matched pair".[5] The first conflict came over money and Annie's independence. Annie wrote short stories, books for children, and articles. As married women did not have the legal right to own property, Frank was able to collect all the money she earned. Politics further divided the couple. Annie began to support farm workers who were fighting to unionise and to win better conditions. Frank was a Tory and sided with the landlords and farmers. The tension came to a head when Annie refused to attend Communion. In 1873 she left him and returned to London. They were legally separated and Annie took her daughter with her.

Besant began to question her own faith. She turned to leading churchmen for advice, going to see Edward Bouverie Pusey, one of the leaders of the Oxford Movement within the Church of England. When she asked him to recommend books that would answer her questions, he told her she had read too many already.[6] Besant returned to Frank to make a last unsuccessful effort to repair the marriage. She finally left for London.

Birkbeck

In the late 1880s she studied at the Birkbeck Literary and Scientific Institution,[7] where her religious and political activities caused alarm. At one point the Institution's governors sought to withhold the publication of her exam results.[8]

Reformer and secularist

She fought for the causes she thought were right, starting with freedom of thought, women's rights, secularism, birth control, Fabian socialism and workers' rights. She was a leading member of the National Secular Society alongside Charles Bradlaugh and the South Place Ethical Society.[9]

Divorce was unthinkable for Frank, and was not really within the reach of even middle-class people. Annie was to remain Mrs Besant for the rest of her life. At first, she was able to keep contact with both children and to have Mabel live with her; she also got a small allowance from her husband.

Once free of Frank Besant and exposed to new currents of thought, she began to question not only her long-held religious beliefs but also the whole of conventional thinking. She began to write attacks on the churches and the way they controlled people's lives. In particular she attacked the status of the Church of England as a state-sponsored faith.

Soon she was earning a small weekly wage by writing a column for the National Reformer, the newspaper of the NSS. The NSS argued for a secular state and an end to the special status of Christianity, and allowed her to act as one of its public speakers. Public lectures were very popular entertainment in Victorian times. Besant was a brilliant speaker, and was soon in great demand. Using the railway, she criss-crossed the country, speaking on all of the most important issues of the day, always demanding improvement, reform and freedom.

For many years Besant was a friend of the National Secular Society's leader, Charles Bradlaugh. Bradlaugh, a former soldier, had long been separated from his wife; Besant lived with him and his daughters, and they worked together on many projects. He was an atheist and a republican; he was also trying to get elected as Member of Parliament (MP) for Northampton.

Besant and Bradlaugh became household names in 1877 when they published Fruits of Philosophy, a book by the American birth-control campaigner Charles Knowlton. It claimed that working-class families could never be happy until they were able to decide how many children they wanted. It also suggested ways to limit the size of their families.[10] The Knowlton book was highly controversial, and was vigorously opposed by the Church. Besant and Bradlaugh proclaimed in the National Reformer:

We intend to publish nothing we do not think we can morally defend. All that we publish we shall defend.[11]

The pair were arrested and put on trial for publishing the Knowlton book. They were found guilty, but released pending appeal. As well as great opposition, Besant and Bradlaugh also received a great deal of support in the Liberal press. Arguments raged back and forth in the letters and comment columns as well as in the courtroom. Besant was instrumental in founding the Malthusian League during the trial, which would go on to advocate for the abolition of penalties for the promotion of contraception.[12] For a time, it looked as though they would be sent to prison. The case was thrown out finally only on a technical point, the charges not having been properly drawn up.

The scandal cost Besant custody of her children. Her husband was able to persuade the court that she was unfit to look after them, and they were handed over to him permanently.

On 6 March 1881 she spoke at the opening of Leicester Secular Society's new Secular Hall in Humberstone Gate, Leicester. The other speakers were George Jacob Holyoake, Harriet Law and Charles Bradlaugh.[13]

Bradlaugh's political prospects were not damaged by the Knowlton scandal and he was elected to Parliament in 1881. Because of his atheism, he asked to be allowed to affirm rather than swear the oath of loyalty. When the possibility of affirmation was refused, Bradlaugh stated his willingness to take the oath. But this option was also challenged. Although many Christians were shocked by Bradlaugh, others (like the Liberal leader Gladstone) spoke up for freedom of belief. It took more than six years before the matter was completely resolved (in Bradlaugh's favour) after a series of by-elections and court appearances.

Meanwhile, Besant built close contacts with the Irish Home Rulers and supported them in her newspaper columns during what are considered crucial years, when the Irish nationalists were forming an alliance with Liberals and Radicals. Besant met the leaders of the Irish home rule movement. In particular, she got to know Michael Davitt, who wanted to mobilise the Irish peasantry through a Land War, a direct struggle against the landowners. She spoke and wrote in favour of Davitt and his Land League many times over the coming decades.

However, Bradlaugh's parliamentary work gradually alienated Besant. Women had no part in parliamentary politics. Besant was searching for a real political outlet, where her skills as a speaker, writer and organiser could do some real good.

Political activism

For Besant, politics, friendship and love were always closely intertwined. Her decision in favour of Socialism came about through a close relationship with George Bernard Shaw, a struggling young Irish author living in London, and a leading light of the Fabian Society. Annie was impressed by his work and grew very close to him too in the early 1880s. It was Besant who made the first move, by inviting Shaw to live with her. This he refused, but it was Shaw who sponsored Besant to join the Fabian Society. In its early days, the society was a gathering of people exploring spiritual, rather than political, alternatives to the capitalist system.[14] Besant began to write for the Fabians. This new commitment – and her relationship with Shaw – deepened the split between Besant and Bradlaugh, who was an individualist and opposed to Socialism of any sort. While he defended free speech at any cost, he was very cautious about encouraging working-class militancy.[15]

Unemployment was a central issue of the time, and in 1887 some of the London unemployed started to hold protests in Trafalgar Square. Besant agreed to appear as a speaker at a meeting on 13 November. The police tried to stop the assembly, fighting broke out, and troops were called. Many were hurt, one man died, and hundreds were arrested; Besant offered herself for arrest, an offer disregarded by the police.[16]

The events created a great sensation, and became known as Bloody Sunday. Besant was widely blamed – or credited – for it. She threw herself into organising legal aid for the jailed workers and support for their families.[17] Bradlaugh finally broke with her because he felt she should have asked his advice before going ahead with the meeting.

Another activity in this period was her involvement in the London matchgirls strike of 1888. She was drawn into this battle of the "New Unionism" by a young socialist, Herbert Burrows. He had made contact with workers at Bryant and May's match factory in Bow, London, who were mainly young women and were very poorly paid. They were also prey to industrial illnesses, like the bone-rotting Phossy jaw, which was caused by the chemicals used in match manufacture.[18] Some of the match workers asked for help from Burrows and Besant in setting up a union.

Besant met the women and set up a committee, which led the women into a strike for better pay and conditions, an action that won public support. Besant led demonstrations by "match-girls", who were cheered in the streets, and prominent churchmen wrote in their support. In just over a week they forced the firm to improve pay and conditions. Besant then helped them to set up a proper union and a social centre.

At the time, the matchstick industry was a very powerful lobby, since electric light was not yet widely available, and matches were an essential commodity; in 1872, lobbyists from the match industry had persuaded the British government to change its planned tax policy. Besant's campaign was the first time anyone had successfully challenged the match manufacturers on a major issue, and was seen as a landmark victory of the early years of British Socialism.

During 1884, Besant had developed a very close friendship with Edward Aveling, a young socialist teacher who lived in her house for a time. Aveling was a scholarly figure and it was he who first translated the important works of Marx into English. He eventually went to live with Eleanor Marx, daughter of Karl Marx. Aveling was a great influence on Besant's thinking and she supported his work, yet she moved towards the rival Fabians at that time. Aveling and Eleanor Marx had joined the Marxist Social Democratic Federation and then the Socialist League, a small Marxist splinter group which formed around the artist William Morris.

It seems that Morris played a large part in converting Besant to Marxism, but it was to the SDF, not his Socialist League, that she turned in 1888. She remained a member for a number of years and became one of its best speakers. She was still a member of the Fabian Society; neither she nor anyone else seemed to think the two movements incompatible at the time.

Soon after joining the Marxists, Besant was elected to the London School Board in 1888.[19] Women at that time were not able to take part in parliamentary politics, but had been brought into the local electorate in 1881.

Besant drove about with a red ribbon in her hair, speaking at meetings. "No more hungry children", her manifesto proclaimed. She combined her socialist principles with feminism: "I ask the electors to vote for me, and the non-electors to work for me because women are wanted on the Board and there are too few women candidates." Besant came out on top of the poll in Tower Hamlets, with over 15,000 votes. She wrote in the National Reformer: "Ten years ago, under a cruel law, Christian bigotry robbed me of my little child. Now the care of the 763,680 children of London is placed partly in my hands."[20]

Besant was also involved in the London dock strike of 1889, in which the dockers, who were employed by the day, were led by Ben Tillett in a struggle for the "Dockers' Tanner". Besant helped Tillett draw up the union's rules and played an important part in the meetings and agitation which built up the organisation. She spoke for the dockers at public meetings and on street corners. Like the match-girls, the dockers won public support for their struggle, and the strike was won.[21]

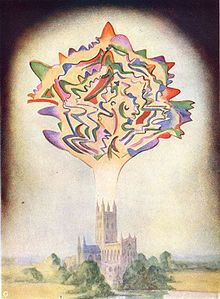

Theosophy

Besant was a prolific writer and a powerful orator.[22] In 1889, she was asked to write a review for the Pall Mall Gazette[23] on The Secret Doctrine, a book by H. P. Blavatsky. After reading it, she sought an interview with its author, meeting Blavatsky in Paris. In this way she was converted to Theosophy. Besant's intellectual journey had always involved a spiritual dimension, a quest for transformation of the whole person. As her interest in theosophy deepened, she allowed her membership of the Fabian Society to lapse (1890) and broke her links with the Marxists. In her Autobiography, Besant follows her chapter on "Socialism" with "Through Storm to Peace", the peace of Theosophy. In 1888, she described herself as "marching toward the Theosophy" that would be the "glory" of her life. Besant had found the economic side of life lacking a spiritual dimension, so she searched for a belief based on "Love". She found this in Theosophy, so she joined the Theosophical Society, a move that distanced her from Bradlaugh and other former activist co-workers.[24] When Blavatsky died in 1891, Besant was left as one of the leading figures in theosophy and in 1893 she represented it at the Chicago World Fair.[25]

In 1893, soon after becoming a member of the Theosophical Society she went to India for the first time.[26] After a dispute the American section split away into an independent organisation. The original society, then led by Henry Steel Olcott and Besant, is today based in Chennai, India, and is known as the Theosophical Society Adyar. Following the split Besant devoted much of her energy not only to the society, but also to India's freedom and progress. Besant Nagar, a neighbourhood near the Theosophical Society in Chennai, is named in her honour.

Co-freemasonry

Besant saw freemasonry, in particular Co-Freemasonry, as an extension of her interest in the rights of women and the greater brotherhood of man and saw co-freemasonry as a "movement which practised true brotherhood, in which women and men worked side by side for the perfecting of humanity. She immediately wanted to be admitted to this organisation", known now as the International Order of Freemasonry for Men and Women, "Le Droit Humain".

The link was made in 1902 by the theosophist Francesca Arundale, who accompanied Besant to Paris, along with six friends. "They were all initiated, passed and raised into the first three degrees and Annie returned to England, bearing a Charter and founded there the first Lodge of International Mixed Masonry, Le Droit Humain." Besant eventually became the Order's Most Puissant Grand Commander, and was a major influence in the international growth of the Order.[27]

President of Theosophical Society

Besant met fellow theosophist Charles Webster Leadbeater in London in April 1894. They became close co-workers in the theosophical movement and would remain so for the rest of their lives. Leadbeater claimed clairvoyance and reputedly helped Besant become clairvoyant herself in the following year. In a letter dated 25 August 1895 to Francisca Arundale, Leadbeater narrates how Besant became clairvoyant. Together they clairvoyantly investigated the universe, matter, thought-forms, and the history of mankind, and co-authored a book called Occult Chemistry.

In 1906 Leadbeater became the centre of controversy when it emerged that he had advised the practice of masturbation to some boys under his care and spiritual instruction. Leadbeater stated he had encouraged the practice to keep the boys celibate, which was considered a prerequisite for advancement on the spiritual path.[28] Because of the controversy, he offered to resign from the Theosophical Society in 1906, which was accepted. The next year Besant became president of the society and in 1908, with her express support, Leadbeater was readmitted to the society. Leadbeater went on to face accusations of improper relations with boys, but none of the accusations were ever proven and Besant never deserted him.[29]

Until Besant's presidency, the society had as one of its foci Theravada Buddhism and the island of Sri Lanka, where Henry Olcott did the majority of his useful work.[30] Under Besant's leadership there was more stress on the teachings of "The Aryavarta", as she called central India, as well as on esoteric Christianity.[31]

Besant set up a new school for boys, the Central Hindu College (CHC) at Banaras which was formed on underlying theosophical principles, and which counted many prominent theosophists in its staff and faculty. Its aim was to build a new leadership for India. The students spent 90 minutes a day in prayer and studied religious texts, but they also studied modern science. It took 3 years to raise the money for the CHC, most of which came from Indian princes.[32] In April 1911, Besant met Pandit Madan Mohan Malaviya and they decided to unite their forces and work for a common Hindu University at Banaras. Besant and fellow trustees of the Central Hindu College also agreed to Government of India's precondition that the college should become a part of the new University. The Banaras Hindu University started functioning from 1 October 1917 with the Central Hindu College as its first constituent college.

Blavatsky had stated in 1889 that the main purpose of establishing the society was to prepare humanity for the future reception of a "torch-bearer of Truth", an emissary of a hidden Spiritual Hierarchy that, according to theosophists, guides the evolution of mankind.[33] This was repeated by Besant as early as 1896; Besant came to believe in the imminent appearance of the "emissary", who was identified by theosophists as the so-called World Teacher.[34][35]

"World Teacher" project

In 1909, soon after Besant's assumption of the presidency, Leadbeater "discovered" fourteen-year-old Jiddu Krishnamurti (1895–1986), a South Indian boy who had been living, with his father and brother, on the grounds of the headquarters of the Theosophical Society at Adyar, and declared him the probable "vehicle" for the expected "World Teacher".[36] The "discovery" and its objective received widespread publicity and attracted worldwide following, mainly among theosophists. It also started years of upheaval, and contributed to splits in the Theosophical Society and doctrinal schisms in theosophy. Following the discovery, Jiddu Krishnamurti and his younger brother Nityananda ("Nitya") were placed under the care of theosophists and Krishnamurti was extensively groomed for his future mission as the new vehicle for the "World Teacher". Besant soon became the boys' legal guardian with the consent of their father, who was very poor and could not take care of them. However, his father later changed his mind and began a legal battle to regain the guardianship, against the will of the boys.[37] Early in their relationship, Krishnamurti and Besant had developed a very close bond and he considered her a surrogate mother – a role she happily accepted. (His biological mother had died when he was ten years old).[38]

In 1929, twenty years after his "discovery", Krishnamurti, who had grown disenchanted with the World Teacher Project, repudiated the role that many theosophists expected him to fulfil. He dissolved the Order of the Star in the East, an organisation founded to assist the World Teacher in his mission, and eventually left the Theosophical Society and theosophy at large.[39] He spent the rest of his life travelling the world as an unaffiliated speaker, becoming in the process widely known as an original, independent thinker on philosophical, psychological, and spiritual subjects. His love for Besant never waned, as also was the case with Besant's feelings towards him;[40] concerned for his wellbeing after he declared his independence, she had purchased 6 acres (2.4 ha) of land near the Theosophical Society estate which later became the headquarters of the Krishnamurti Foundation India .

Home Rule movement

Along with her theosophical activities, Besant continued to actively participate in political matters. She had joined the Indian National Congress. As the name suggested, this was originally a debating body, which met each year to consider resolutions on political issues. Mostly it demanded more of a say for middle-class Indians in British Indian government. It had not yet developed into a permanent mass movement with local organisation. About this time her co-worker Leadbeater moved to Sydney.

In 1914 World War I broke out, and Britain asked for the support of its Empire in the fight against Germany. Echoing an Irish nationalist slogan, Besant declared, "England's need is India's opportunity". As editor of the New India newspaper, she attacked the colonial government of India and called for clear and decisive moves towards self-rule. As with Ireland, the government refused to discuss any changes while the war lasted.

In 1916 Besant launched the All India Home Rule League along with Lokmanya Tilak, once again modelling demands for India on Irish nationalist practices. This was the first political party in India to have regime change as its main goal. Unlike the Congress itself, the League worked all year round. It built a structure of local branches, enabling it to mobilise demonstrations, public meetings and agitations. In June 1917 Besant was arrested and interned at a hill station, where she defiantly flew a red and green flag. The Congress and the Muslim League together threatened to launch protests if she were not set free; Besant's arrest had created a focus for protest.[41]

The government was forced to give way and to make vague but significant concessions. It was announced that the ultimate aim of British rule was Indian self-government, and moves in that direction were promised. Besant was freed in September 1917, welcomed by crowds all over India, and in December she took over as president of the Indian National Congress for a year.

After the war, a new leadership of the Indian National Congress emerged around Mohandas K. Gandhi – one of those who had written to demand Besant's release. He was a lawyer who had returned from leading Asians in a peaceful struggle against racism in South Africa. Jawaharlal Nehru, Gandhi's closest collaborator, had been educated by a theosophist tutor.

The new leadership was committed to action that was both militant and non-violent, but there were differences between them and Besant. Despite her past, she was not happy with their socialist leanings. Until the end of her life, however, she continued to campaign for India's independence, not only in India but also on speaking tours of Britain.[42] In her own version of Indian dress, she remained a striking presence on speakers' platforms. She produced a torrent of letters and articles demanding independence.

Later years and death

Besant tried as a person, theosophist, and president of the Theosophical Society, to accommodate Krishnamurti's views into her life, without success; she vowed to personally follow him in his new direction although she apparently had trouble understanding both his motives and his new message.[43] The two remained friends until the end of her life.

In 1931 she became ill in India.[44]

Besant died on 20 September 1933, at age 85, in Adyar, Madras Presidency, British India. Her body was cremated.[45][46]

She was survived by her daughter, Mabel. After her death, colleagues Jiddu Krishnamurti, Aldous Huxley, Guido Ferrando, and Rosalind Rajagopal, built the Happy Valley School in California, now renamed the Besant Hill School of Happy Valley in her honour.

Descendants

The subsequent family history became fragmented. A number of Besant's descendants have been traced in detail from her son Arthur Digby's side. Arthur Digby Besant (1869-1960) was President of the Institute of Actuaries, 1924-26. He wrote The Besant Pedigree (1930) and was director of the Theosophical bookstore in London. One of Arthur Digby's daughters was Sylvia Besant, who married Commander Clem Lewis in the 1920s. They had a daughter, Kathleen Mary, born in 1934, who was given away for adoption within three weeks of the birth and had the new name of Lavinia Pollock. Lavinia married Frank Castle in 1953 and raised a family of five of Besant's great-great-grandchildren – James, Richard, David, Fiona and Andrew Castle – the last and youngest sibling being a former British professional tennis player and now television presenter and personality.

Criticism of Christianity

| Author | Annie Besant |

|---|---|

| Series | The freethinker's text-book |

Publication date | 1876 |

| Preceded by | Part I. by Charles Bradlaugh[47] |

Original text | Christianity: Its Evidences, Its Origin, Its Morality, Its History at Project Gutenberg |

Besant opined that for centuries the leaders of Christian thought spoke of women as a necessary evil, and that the greatest saints of the Church were those who despised women the most, "Against the teachings of eternal torture, of the vicarious atonement, of the infallibility of the Bible, I leveled all the strength of my brain and tongue, and I exposed the history of the Christian Church with unsparing hand, its persecutions, its religious wars, its cruelties, its oppressions. (Annie Besant, An Autobiography Chapter VII)." In the section named "Its Evidences Unreliable" of her work "Christianity", Besant presents the case of why the Gospels are not authentic.

- 1876: "Christianity", The freethinker's text-book, Part II. (Issued by authority of the National Secular Society) ;

(D.) That before about A.D. 180 there is no trace of FOUR gospels among the Christians. ...As it is not pretended by any that there is any mention of four Gospels before the time of Irenaeus, excepting this "harmony". pleaded by some as dated about A.D. 170 and by others as between 170 and 180, it would be sheer waste of time and space to prove further a point admitted on all hands. This step of our argument is, then on solid and unassailable ground —That before about A.D. 180 there is no trace of FOUR gospels among the Christians. (E.) That, before that date, Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, are not selected as the four evangelists. This position necessarily follows from the preceding one [D.], since four evangelists could not be selected until four Gospels were recognised. Here, again, Dr. Giles supports the argument we are building up. He says : "Justin Martyr never once mentions by name the evangelists Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. This circumstance is of great importance ; for those who assert that our four canonical Gospels are contemporary records of our Saviour's ministry, ascribe them to Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, and to no other writers."[48][49]

Works

Besides being a prolific writer, Besant was a "practised stump orator" who gave sixty-six public lectures in one year. She also engaged in public debates.[22]

List of Works on Online Books [1]

List of Work on Open Library [2]

- The Political Status of Women (1874)[50]

- Christianity: Its Evidences, Its Origin, Its Morality, Its History (1876)

- The Law of Population (1877)

- My Path to Atheism (1878, 3rd ed 1885)

- Marriage, As It Was, As It Is, And As It Should Be: A Plea for Reform (1878)

- The Atheistic Platform: 12 Lectures One by Besant (1884)

- Autobiographical Sketches (1885)

- Why I Am a Socialist (1886)

- Why I Became a Theosophist (1889)

- The Seven Principles of Man (1892)

- Bhagavad Gita (translated as The Lord's Song) (1895)

- Karma (1895)

- In the Outer Court(1895)

- The Ancient Wisdom (1897)

- Dharma (1898)

- Thought Forms with C. W. Leadbeater (1901)

- The Religious Problem in India (1901)

- Thought Power: Its Control and Culture (1901)

- Esoteric Christianity (1905 2nd ed)

- A Study in Consciousness: A contribution to the science of psychology. (ca 1907, rpt 1918) [3]

- Occult Chemistry with C. W. Leadbeater (1908) [4]

- An Introduction to Yoga (1908) [5]

- Australian Lectures (1908)

- Annie Besant: An Autobiography (1908 2nd ed)

- The Religious Problem in India Lectures on Islam, Jainism, Sikhism, Theosophy (1909) [6]

- Man and His Bodies (1896, rpt 1911) [7]

- Elementary Lessons on Karma (1912)

- A Study in Karma (1912)

- Initiation: The Perfecting of Man (1912) [8]

- Man's Life in This and Other Worlds (1913) [9]

- Man: Whence, How and Whither with C. W. Leadbeater (1913) [10]

- The Doctrine of the Heart (1920) [11]

- The Future of Indian Politics 1922

- The Life and Teaching of Muhammad (1932) [12]

- Memory and Its Nature (1935) [13]

- Various writings regarding Helena Blavatsky (1889–1910) [14]

- Selection of Pamphlets as follows: [15]

- "Sin and Crime" (1885)

- "God's Views on Marriage" (1890)

- "A World Without God" (1885)

- "Life, Death, and Immortality" (1886)

- "Theosophy" (1925?)

- "The World and Its God" (1886)

- "Atheism and Its Bearing on Morals" (1887)

- "On Eternal Torture" (n.d.)

- "The Fruits of Christianity" (n.d.)

- "The Jesus of the Gospels and the Influence of Christianity" (n.d.)

- "The Gospel of Christianity and the Gospel of Freethought" (1883)

- "Sins of the Church: Threatenings and Slaughters" (n.d.)

- "For the Crown and Against the Nation" (1886)

- "Christian Progress" (1890)

- "Why I Do Not Believe in God" (1887)

- "The Myth of the Resurrection" (1886)

- "The Teachings of Christianity" (1887)

See also

- Annie Besant School Allahabad

- History of feminism

- Man: whence, how and whither

- Theosophy and Christianity

- Theosophy and science

References

- ^ a b "Annie Besant (1847–1933)" BBC UK Archive

- ^ "History and Development of the Board". Hyderabad (Sind) National Collegiate Board. Archived from the original on 24 September 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Anne Taylor, 'Besant, Annie (1847–1933)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2008 accessed 30 March 2015.

- ^ Annie Besant: An Autobiography, London, 1885, chapter 4.

- ^ Annie Besant: an Autobiography (Unwin, 1908), 81.

- ^ Annie Besant: An Autobiography, London, 1885, chapter 5.

- ^ "Notable Birkbeckians". Birkbeck, University of London. Retrieved 19 May 2017.

- ^ "The History of Birkbeck". Birkbeck, University of London. Archived from the original on 6 October 2006. Retrieved 26 November 2006.

- ^ MacKillop, I. D. (1986) The British Ethical Societies, Cambridge University Press (Accessed 13 May 2014).

- ^ Knowlton, Charles (October 1891) [1840]. Besant, Annie; Bradlaugh, Charles (eds.). Fruits of philosophy: a treatise on the population question. San Francisco: Reader's Library. OCLC 626706770. A publication about birth control. View original copy.

- ^ Annie Besant (1885). Autobiographical sketches. Freethought Publishing. p. 116. OL 26315876M.

- ^ F. D'arcy (November 1977). "The Malthusian League and resistance to birth control propaganda in late Victorian Britain". Population Studies. 31 (3): 429–448. doi:10.1080/00324728.1977.10412759. JSTOR 2173367.

- ^ Gimson 1932

- ^ Edward R. Pease, The History of the Fabian Society (E. P. Dutton, 1916, rpt Aware Journalism, 2014), 62.

- ^ Theresa Notare, A Revolution in Christian Morals: Lambeth 1930-Resolution #15. History and Reception (ProQuest, 2008), 188.

- ^ Sally Peters, Bernard Shaw: The Ascent of the Superman (Yale University, 1996), 94.

- ^ Kumar, Raj, Annie Besant's Rise to Power in Indian Politics, 1914–1917 (Concept Publishing, 1981), 36.

- ^ "White slavery in London" The Link, Issue no. 21 (via Tower Hamlets' Local History Library and Archives)

- ^ Edward R. Pease, The History of the Fabian Society (E. P. Dutton, 1916, rpt Aware Journalism, 2014), 179.

- ^ Jyoti Chandra, Annie Besant: from theosophy to nationalism (K.K. Publications, 2001), 17.

- ^ Margaret Cole, The Story of Fabian Socialism (Stanford University, 1961), 34.

- ^ a b Mark Bevir, The Making of British Socialism (Princeton University, 2011 ), 202.

- ^ Lutyens, Krishnamurti: The Years of Awakening, Avon/Discus. 1983. p 13

- ^ Annie Besant, Annie Besant: an Autobiography (Unwin 1908), 330, 338, 340, 344, 357.

- ^ Emmett A. Greenwalt, The Point Loma Community in California, 1897–1942: A Theosophical Experiment (University of California, 1955), 10.

- ^ Kumari Jayawardena, The White Woman's Other Burden (Routledge, 1995, 62.

- ^ The International Bulletin, 20 September 1933, The International Order of Co-Freemasonry, Le Droit Humain. "In a very short time, Sister Besant founded new lodges: three in London, three in the south of England, three in the North and North-West; she even organised one in Scotland. Travelling in 1904 with her sisters and brothers she met in the Netherlands, other brethren of a male obedience, who, being interested, collaborated in the further expansion of Le Droit Humain. Annie continued to work with such ardour that soon new lodges were formed Great Britain, South America, Canada, India, Ceylon, Australia and New Zealand. The lodges in all these countries were united under the name of the British Federation."

- ^ Charles Webster Leadbeater 1854–1934: A Biographical Study, by Gregory John Tillett, 2008.

- ^ Besant, Annie (2 June 1913). "Naranian v. Besant". [Letters to the Editor]. The Times (London). p. 7. ISSN 0140-0460.

- ^ Blavatsky and Olcott had become Buddhists in Sri Lanka, and promoted Buddhist revival on the subcontinent. See also: Maha Bodhi Society.

- ^ M. K. Singh, Encyclopaedia Of Indian War Of Independence (1857–1947) (Anmol Publications, 2009) 118.

- ^ Kumari Jayawardena, The White Woman's Other Burden (Routledge, 1995), 128.

- ^ Blavatsky, H. P. (1889). The Key to Theosophy. London: The Theosophical Publishing Company. pp. 306–307.

- ^ Lutyens, p. 12.

- ^ Wessinger, Catherine Lowman (1988). Annie Besant and Progressive Messianism, 1847–1933. Lewiston, New York: Edwin Mellen Press. ISBN 978-0-88946-523-7.

- ^ Lutyens, Mary (1975). Krishnamurti: The Years of Awakening. NewYork: Farrar Straus and Giroux. Hardcover. pp. 20–21. ISBN 0-374-18222-1.

- ^ Lutyens ch. 7.

- ^ Lutyens p. 5. Also in p. 31, Krishnamurti's letter to Besant dated 24 December 1909, and in p. 62, letter dated 5 January 1913.

- ^ Lutyens pp. 276–278, 285.

- ^ Lutyens, Mary (2003). The Life and Death of Krishnamurti. Bramdean: Krishnamurti Foundation Trust. p. 81. ISBN 0-900506-22-9.

- ^ Gopal, Madan (1990). K.S. Gautam (ed.). India through the ages. Publication Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. p. 192.

- ^ Jennifer S. Uglow, Maggy Hendry, The Northeastern Dictionary of Women's Biography (Northeastern University, 1999).

- ^ Lutyens pp. 236, 278–280.

- ^ "Mrs. Annie Besant, 84, Is Gravely Ill in India. Leader of Theosophists Says Work in This Life Is Done, but Promises to Return". The New York Times. Associated Press. 6 November 1931. Retrieved 14 February 2014.

Mrs. Annie Besant, 84-year-old Theosophist, is so ill, it was learned today, that she is unable to take nourishment.

- ^ "Annie Besant Cremated. Theosophist Leader's Body Put on Pyre on River Bank in India". The New York Times. 22 September 1933. Retrieved 14 February 2014.

- ^ "Dr. Annie Besant". Sydney Morning Herald. 22 September 1933. p. 12 – via Google News Archive.

- ^ Bradlaugh, Charles; Besant, Annie; Watts, Charles; National Secular Society (1876). The freethinker's text-book. Part I. C. Watts.

Part I., section I. & II. by Charles Bradlaugh (Image of Book cover at Google Books)

{{cite book}}: External link in|quote= - ^ Besant, Annie Wood (1893). Christianity: Its Evidences, Its Origin, Its Morality, Its History. R. Forder. p. 261.

(D.) That before about A.D. 180 there is no trace of FOUR gospels among the Christians. ...As it is not pretended by any that there is any mention of four Gospels before the time of Irenaeus, excepting this "harmony", pleaded by some as dated about A.D. 170 and by others as between 170 and 180, it would be sheer waste of time and space to prove further a point admitted on all hands. This step of our argument is, then on solid and unassailable ground —That before about A.D. 180 there is no trace of FOUR gospels among the Christians. (E.) That, before that date, Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, are not selected as the four evangelists. This position necessarily follows from the preceding one [D.], since four evangelists could not be selected until four Gospels were recognised. Here, again, Dr. Giles supports the argument we are building up. He says : "Justin Martyr never once mentions by name the evangelists Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. This circumstance is of great importance ; for those who assert that our four canonical Gospels are contemporary records of our Saviour's ministry, ascribe them to Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, and to no other writers." (Image of p. 261 at Google Books)

{{cite book}}: External link in|quote= - ^ Giles, John Allen (1854). "VIII. Justin Martyr". Christian Records: an historical enquiry concerning the age, authorship, and authenticity of the New Testament. p. 73.

1. Justin Martyr never once mentions by name the evangelists Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. This circumstance is of great importance ; for those who assert that our four canonical Gospels are contemporary records of our Saviour's ministry, ascribe them to Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, and to no other writers. ...Justin Martyr, it must be remembered, wrote in 150, and neither he nor any writer before him has alluded, in the most remote degree, to four specific Gospels bearing the names of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. (Image of p. 73 at google Books)

{{cite book}}: External link in|quote= - ^ The Political Status of Women (1874) was Besant's first public lecture. Carol Hanbery MacKay, Creative Negativity: Four Victorian Exemplars of the Female Quest (Stanford University, 2001), 116–117.

Further reading

- Briggs, Julia. A Woman of Passion: The Life of E. Nesbit. New Amsterdam Books, 2000, 68, 81-82, 92-96, 135-139

- Chandrasekhar, S. A Dirty, Filthy Book: The Writing of Charles Knowlton and Annie Besant on Reproductive Physiology and Birth Control and an Account of the Bradlaugh-Besant Trial. University of California Berkeley 1981

- Grover, Verinder and Ranjana Arora (eds.) Annie Besant: Great Women of Modern India – 1 : Published by Deep of Deep Publications, New Delhi, India, 1993

- Kumar, Raj, Annie Besant's Rise to Power in Indian Politics, 1914–1917. Concept Publishing, 1981

- Kumar, Raj Rameshwari Devi and Romila Pruthi. Annie Besant: Founder of Home Rule Movement, Pointer Publishers, 2003 ISBN 81-7132-321-9

- Manvell, Roger. The trial of Annie Besant and Charles Bradlaugh. Elek, London 1976

- Nethercot, Arthur H. The first five lives of Annie Besant Hart-Davis: London, 1961

- Nethercot, Arthur H. The last four lives of Annie Besant Hart-Davis: London (also University of Chicago Press 1963) ISBN 0-226-57317-6

- Taylor, Anne. Annie Besant: A Biography, Oxford University Press, 1991 (also US edition 1992) ISBN 0-19-211796-3

- Uglow, Jennifer S., Maggy Hendry, The Northeastern Dictionary of Women's Biography. Northeastern University, 1999

External links

- Works by Annie Besant at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Annie Besant at the Internet Archive

- Works by Annie Besant at Open Library

- Works by Annie Besant at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Annie Wood Besant: Orator, Activist, Mystic, Rhetorician By Susan Dobra

- Annie Besant's Quest for Truth: Christianity, Secularism, and New Age Thought

- Annie Besant's Multifaceted Personality. A Biographical Sketch

- Thought power, its control and culture Cornell University Library Historical Monographs Collection.

- The British Federation of the International Order of Co-Freemasonry, Le Droit Humain, founded by Annie Besant in 1902

- Annie Besant Biography at varanasi.org.in

- William Thomas Stead, “Character Sketch: October of Mrs. Annie Besant” 349-367 in Review of Reviews IV:22, October 1891.

- Newspaper clippings about Annie Besant in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

- 1847 births

- 1933 deaths

- People from Clapham

- Theosophy

- English Theosophists

- Esoteric Christianity

- British birth control activists

- English occult writers

- English non-fiction writers

- English spiritual writers

- English activists

- English socialists

- Presidents of the Indian National Congress

- English suffragists

- Feminist artists

- History of Chennai

- English women writers

- Alumni of Birkbeck, University of London

- Former Anglicans

- Former atheists and agnostics

- Feminism and spirituality

- Scouting and Guiding in India

- Recipients of the Silver Wolf Award

- Social Democratic Federation members

- Members of the Fabian Society

- Women of the Victorian era

- Members of the London School Board

- Victorian women writers

- Victorian writers

- Banaras Hindu University people

- English Freemasons

- Freemasons

- Founders of Indian schools and colleges

- English feminists

- Socialist feminists

- Women Indian independence activists

- British reformers

- 19th-century British women writers

- 19th-century British writers

- Indian women philanthropists

- Indian philanthropists

- 19th-century Indian politicians

- 20th-century Indian politicians

- 19th-century Indian women writers

- 19th-century Indian writers

- 20th-century Indian women writers

- 20th-century Indian writers

- 19th-century Indian women politicians

- 20th-century Indian women politicians

- Translators of the Bhagavad Gita

- People from Sibsey