Hydroxycarbamide

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Droxia, Hydrea, Siklos, others |

| Other names | Hydroxyurea (USAN US) |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682004 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Metabolism | Liver (to CO2 and urea) |

| Elimination half-life | 2–4 hours |

| Excretion | Kidney and lungs |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| NIAID ChemDB | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.004.384 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

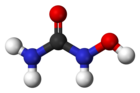

| Formula | CH4N2O2 |

| Molar mass | 76.055 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 133 to 136 °C (271 to 277 °F) |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Hydroxycarbamide, also known as hydroxyurea, is a medication used in sickle-cell disease, essential thrombocythemia, chronic myelogenous leukemia, polycythemia vera, and cervical cancer.[4][5] In sickle-cell disease it increases fetal hemoglobin and decreases the number of attacks.[4] It is taken by mouth.[4]

Common side effects include bone marrow suppression, fevers, loss of appetite, psychiatric problems, shortness of breath, and headaches.[4][5] There is also concern that it increases the risk of later cancers.[4] Use during pregnancy is typically harmful to the fetus.[4] Hydroxycarbamide is in the antineoplastic family of medications. It is believed to work by blocking the making of DNA.[4]

Hydroxycarbamide was approved for medical use in the United States in 1967.[4] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[6] Hydroxycarbamide is available as a generic medication.[4]

Medical uses

[edit]Hydroxycarbamide is used for the following indications:

- Myeloproliferative disease (primarily essential thrombocythemia and polycythemia vera). It has been found to be superior to anagrelide for the control of ET.[7]

- Sickle-cell disease[8] (increases production of fetal hemoglobin that then interferes with the hemoglobin polymerisation as well as by reducing white blood cells that contribute to the general inflammatory state in sickle cell patients.)

- Second line treatment for psoriasis[9] (slows down the rapid division of skin cells)

- Systemic mastocytosis with associated hematological neoplasm(SM-AHN) [10] (The utility in treating SM-AHN with hydroxycarbamide stems from its myelosuppressive activity, it does not however exhibit any selective anti-mast cell activity)

- Chronic myelogenous leukemia (largely replaced by imatinib, but still in use for its cost-effectiveness)[11]

Side effects

[edit]Reported side effects are: neurological reactions (e.g., headache, dizziness, drowsiness, disorientation, hallucinations, and convulsions), nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, mucositis, anorexia, stomatitis, bone marrow toxicity (dose-limiting toxicity; may take 7–21 days to recover after the drug has been discontinued), megaloblastic anemia, thrombocytopenia, bleeding, hemorrhage, gastrointestinal ulceration and perforation, immunosuppression, leukopenia, alopecia (hair loss), skin rashes (e.g., maculopapular rash), erythema, pruritus, vesication or irritation of the skin and mucous membranes, pulmonary edema, abnormal liver enzymes, creatinine and blood urea nitrogen.[12]

Due to its negative effect on the bone marrow, regular monitoring of the full blood count is vital, as well as early response to possible infections. In addition, renal function, uric acid and electrolytes, as well as liver enzymes, are commonly checked.[13] Moreover, because of this, its use in people with leukopenia, thrombocytopenia or severe anemia is contraindicated.[14]

Hydroxycarbamide has been used primarily for the treatment of myeloproliferative diseases, which has an inherent risk of transforming to acute myeloid leukemia. There has been a longstanding concern that hydroxycarbamide itself carries a leukemia risk, but large studies have shown that the risk is either absent or very small. Nevertheless, it has been a barrier for its wider use in patients with sickle-cell disease.[15]

Mechanism of action

[edit]Hydroxycarbamide decreases the production of deoxyribonucleotides[16] via inhibition of the enzyme ribonucleotide reductase by scavenging tyrosyl free radicals as they are involved in the reduction of nucleoside diphosphates (NDPs).[15] Additionally, hydroxycarbamide causes production of reactive oxygen species in cells, leading to disassembly of replicative DNA polymerase enzymes and arresting DNA replication.[17]

In the treatment of sickle-cell disease, hydroxycarbamide increases the concentration of fetal hemoglobin. The precise mechanism of action is not yet clear, but it appears that hydroxycarbamide increases nitric oxide levels, causing soluble guanylyl cyclase activation with a resultant rise in cyclic GMP, and the activation of gamma globin gene expression and subsequent gamma chain synthesis necessary for fetal hemoglobin (HbF) production (which does not polymerize and deform red blood cells like the mutated HbS, responsible for sickle cell disease). Adult red cells containing more than 1% HbF are termed F cells. These cells are progeny of a small pool of immature committed erythroid precursors (BFU-e) that retain the ability to produce HbF. Hydroxyurea also suppresses the production of granulocytes in the bone marrow which has a mild immunosuppressive effect particularly at vascular sites where sickle cells have occluded blood flow.[15][18]

Natural occurrence

[edit]Hydroxyurea has been reported as endogenous in human blood plasma at concentrations of approximately 30 to 200 ng/ml.[19]

Chemistry

[edit]| Hazards | |

|---|---|

| Occupational safety and health (OHS/OSH): | |

Main hazards

|

Mutagen – Reproductive toxicity |

| GHS labelling: | |

| |

| Danger | |

| H340, H361 | |

| P201, P202, P281, P308+P313, P405, P501 | |

Hydroxyurea has been prepared in many different ways since its initial synthesis in 1869.[20] The original synthesis by Dresler and Stein was based around the reaction of hydroxylamine hydrochloride and potassium cyanate.[20] Hydroxyurea lay dormant for more than fifty years until it was studied as part of an investigation into the toxicity of protein metabolites.[21] Due to its chemical properties hydroxyurea was explored as an antisickling agent in the treatment of hematological conditions.

One common mechanism for synthesizing hydroxyurea is by the reaction of calcium cyanate with hydroxylamine nitrate in absolute ethanol and by the reaction of a cyanate salt and hydroxylamine hydrochloride in aqueous solution.[22] Hydroxyurea has also been prepared by converting a quaternary ammonium anion exchange resin from the chloride form to the cyanate form with sodium cyanate and reacting the resin in the cyanate form with hydroxylamine hydrochloride. This method of hydroxyurea synthesis was patented by Hussain et al. (2015).[23]

Pharmacology

[edit]Hydroxyurea is a monohydroxyl-substituted urea (hydroxycarbamate) antimetabolite. Similar to other antimetabolite anti-cancer drugs, it acts by disrupting the DNA replication process of dividing cancer cells in the body. Hydroxyurea selectively inhibits ribonucleoside diphosphate reductase, an enzyme required to convert ribonucleoside diphosphates into deoxyribonucleoside diphosphates, thereby preventing cells from leaving the G1/S phase of the cell cycle. This agent also exhibits radiosensitizing activity by maintaining cells in the radiation-sensitive G1 phase and interfering with DNA repair.[24]

Biochemical research has explored its role as a DNA replication inhibitor[25] which causes deoxyribonucleotide depletion and results in DNA double strand breaks near replication forks (see DNA repair). Repair of DNA damaged by chemicals or irradiation is also inhibited by hydroxyurea, offering potential synergy between hydroxyurea and radiation or alkylating agents.[26]

Hydroxyurea has many pharmacological applications under the Medical Subject Headings classification system:[24]

- Antineoplastic agents – Substances that inhibit or prevent the proliferation of neoplasms.

- Antisickling agents – Agents used to prevent or reverse the pathological events leading to sickling of erythrocytes in sickle cell conditions.

- Nucleic acid synthesis inhibitors – Compounds that inhibit cell production of DNA or RNA.

- Enzyme inhibitors – Compounds or agents that combine with an enzyme in such a manner as to prevent the normal substrate-enzyme combination and the catalytic reaction.

- Cytochrome P-450 CYP2D6 inhibitors – Agents that inhibit one of the most important enzymes involved in the metabolism of xenobiotics in the body, CYP2D6, a member of the cytochrome P450 mixed oxidase system.

Society and culture

[edit]Brand names

[edit]Brand names include: Hydrea, Litalir, Droxia, and Siklos.[citation needed]

References

[edit]- ^ "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- ^ "Xromi- hydroxyurea solution". DailyMed. 8 April 2024. Retrieved 18 May 2024.

- ^ "Siklos EPAR". European Medicines Agency. 9 July 2003. Retrieved 24 July 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Hydroxyurea". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ^ a b "Hydrea 500 mg Hard Capsules – Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC) – (eMC)". www.medicines.org.uk. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- ^ World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ^ Harrison CN, Campbell PJ, Buck G, Wheatley K, East CL, Bareford D, et al. (July 2005). "Hydroxyurea compared with anagrelide in high-risk essential thrombocythemia". The New England Journal of Medicine. 353 (1): 33–45. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa043800. PMID 16000354.

- ^ Lanzkron S, Strouse JJ, Wilson R, Beach MC, Haywood C, Park H, et al. (June 2008). "Systematic review: Hydroxyurea for the treatment of adults with sickle cell disease". Annals of Internal Medicine. 148 (12): 939–955. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-148-12-200806170-00221. PMC 3256736. PMID 18458272.

- ^ Sharma VK, Dutta B, Ramam M (2004). "Hydroxyurea as an alternative therapy for psoriasis". Indian Journal of Dermatology, Venereology and Leprology. 70 (1): 13–17. PMID 17642550. Archived from the original on 3 July 2009.

- ^ Lim KH, Pardanani A, Butterfield JH, Li CY, Tefferi A (December 2009). "Cytoreductive therapy in 108 adults with systemic mastocytosis: Outcome analysis and response prediction during treatment with interferon-alpha, hydroxyurea, imatinib mesylate or 2-chlorodeoxyadenosine". American Journal of Hematology. 84 (12): 790–794. doi:10.1002/ajh.21561. PMID 19890907.

- ^ Dalziel K, Round A, Stein K, Garside R, Price A (July 2004). "Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of imatinib for first-line treatment of chronic myeloid leukaemia in chronic phase: a systematic review and economic analysis". Health Technology Assessment. 8 (28): iii, 1-iii120. doi:10.3310/hta8280. PMID 15245690.

- ^ Liebelt EL, Balk SJ, Faber W, Fisher JW, Hughes CL, Lanzkron SM, et al. (August 2007). "NTP-CERHR expert panel report on the reproductive and developmental toxicity of hydroxyurea". Birth Defects Research. Part B, Developmental and Reproductive Toxicology. 80 (4): 259–366. doi:10.1002/bdrb.20123. PMID 17712860.

- ^ Longe JL (2002). Gale Encyclopedia Of Cancer: A Guide To Cancer And Its Treatments. Detroit: Thomson Gale. pp. 514–516. ISBN 978-1-4144-0362-5.

- ^ "HYDREA" (PDF). Accessdata.fda.gov. US Food and Drug Administration.

- ^ a b c Platt OS (March 2008). "Hydroxyurea for the treatment of sickle cell anemia". The New England Journal of Medicine. 358 (13): 1362–1369. doi:10.1056/NEJMct0708272. PMID 18367739.

- ^ "hydroxyurea" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- ^ Shaw A (October 2024). "Revised mechanism of hydroxyurea-induced cell cycle arrest and an improved alternative". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (USA). 121 (42): e2404470121. Bibcode:2024PNAS..12104470S. doi:10.1073/pnas.2404470121. PMC 11494364. PMID 39374399.

- ^ Cokic VP, Smith RD, Beleslin-Cokic BB, Njoroge JM, Miller JL, Gladwin MT, et al. (January 2003). "Hydroxyurea induces fetal hemoglobin by the nitric oxide-dependent activation of soluble guanylyl cyclase". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 111 (2): 231–239. doi:10.1172/JCI16672. PMC 151872. PMID 12531879.

- ^ Kettani T, Cotton F, Gulbis B, Ferster A, Kumps A (February 2009). "Plasma hydroxyurea determined by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry". Journal of Chromatography. B, Analytical Technologies in the Biomedical and Life Sciences. 877 (4): 446–450. doi:10.1016/j.jchromb.2008.12.048. PMID 19144580.

- ^ a b Dresler WF, Stein R (1869). "Ueber den Hydroxylharnstoff". Justus Liebigs Ann. Chem. 150 (2): 1317–22. doi:10.1002/jlac.18691500212.

- ^ Rees DC (April 2011). "The rationale for using hydroxycarbamide in the treatment of sickle cell disease". Haematologica. 96 (4): 488–491. doi:10.3324/haematol.2011.041988. PMC 3069221. PMID 21454878.

- ^ US 2705727, Graham PJ, "Synthesis of Ureas", assigned to E.I. du Pont de Nemours & Co., Wilmington, DE

- ^ Hussain KA, Abid DS, Adam GA (2016). "New Method for Synthesis of Hydroxyurea and Some of its Polymer Supported Derivatives As New Controlled Release Drugs". Journal of Basrah Research. 41 (1). doi:10.13140/RG.2.1.3607.2720.

- ^ a b "Hydroxyurea". PubChem. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 18 May 2017.

- ^ Koç A, Wheeler LJ, Mathews CK, Merrill GF (January 2004). "Hydroxyurea arrests DNA replication by a mechanism that preserves basal dNTP pools". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 279 (1): 223–230. doi:10.1074/jbc.M303952200. PMID 14573610. S2CID 2675195.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Yarbro JW (June 1992). "Mechanism of action of hydroxyurea". Seminars in Oncology. 19 (3 Suppl 9): 1–10. PMID 1641648.