Philosophy

This article may require copy editing for grammar, style, cohesion, tone, or spelling. (April 2016) |

This article may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. (April 2016) |

| Part of a series on |

| Philosophy |

|---|

Philosophy (from Greek φιλοσοφία, philosophia, literally "love of wisdom"[1][2][3][4]) is the study of general and fundamental problems concerning matters such as existence, knowledge, values, reason, mind, and language.[5][6] The term was probably coined by the pre-Socratic thinker Pythagoras. Philosophical methods include questioning, critical discussion, rational argument, and the systematic presentation of big ideas.[7][8]

Philosophy is the general and fundamental study of almost any topic. For example, philosophers might ask highly abstract and theoretical questions: is it possible to know anything and to prove it?[9][10][11] What is most real? However, philosophers might also pose more practical and concrete questions such as: Is there a best way to live? Is it better to be just or unjust (if you can get away with it)?[12] Do humans have free will or not?[13]

Historically, the general term "philosophy" encompassed any body of knowledge.[14] Specific terms like "natural philosophy" encompassed disciplines today associated with sciences like astronomy, medicine, and physics.[15][16] For example, Newton's (1687) "Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy" is now classified as a book of physics.

In the 19th century, the growth of modern research universities lead academic philosophy and other disciplines to professionalize and specialize.[17][18] In the modern era, some investigations that were traditionally seen as part of philosophy split off to become new academic disciplines, including psychology, sociology, linguistics, and economics. Other investigations that are closely related to art, science, politics, or other pursuits remained part of philosophy. For example, is beauty objective or subjective?[19][20] Are there many scientific methods or just one?[21] Is political utopia a hopeful dream or hopeless fantasy?[22][23][24] Major sub-fields of academic philosophy include metaphysics, epistemology, ethics, aesthetics, political philosophy, logic, philosophy of science, and history of western philosophy.

Contemporary philosophers contribute to society primarily as professors, researchers, and writers. However, many of those who study philosophy in undergraduate universities or graduate school contribute to law, journalism, entertainment, politics, religion, science, business, and various arts.[25]

Introduction

Philosophy and culture

In the broadest sense, philosophy is synonymous with wisdom or learning. In in this sense, all cultures -- whether prehistoric, medieval, or modern; Eastern, Western, religious or secular — have a wisdom tradition.

- Western philosophy

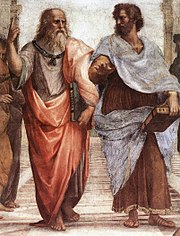

Western philosophy is typically dated to the pre-Socratic Greek philosophers. Pre-Socratic Greek philosopher Pythagoras distinguished himself from other "wise ones" by calling himself a mere lover of wisdom, suggesting that he was not wise.[26] Socrates used this title and insisted that he possessed no wisdom but was a pursuer of wisdom.[27] Socrate's student Plato is often credited as the founder of Western philosophy. The philosopher Alfred North Whitehead said of Plato: "The safest general characterization of the European philosophical tradition is that it consists of a series of footnotes to Plato. I do not mean the systematic scheme of thought which scholars have doubtfully extracted from his writings. I allude to the wealth of general ideas scattered through them."[28]

- Non-western philosophy

Strictly speaking, there is no such thing as a single, monolithic "eastern philosophy". But the term is used in the the West to denote a variety of traditions in China and India, as well as in Japan, Persia, and other regions. Various Eastern philosophies have their own timelines, regions, and philosophers. Major traditions include:

- African philosophy and Ethiopian philosophy

- Ancient Egyptian philosophy and Babylonian literature#Philosophy

- Indian philosophy, Jain philosophy, and Hindu philosophy

- Iranian philosophy

- East Asian Neo-Confucianism and Buddhist philosophy#Chinese Buddhism, Japanese philosophy, and Korean philosophy

- Persian Zoroastrianism

- Middle Eastern Islamic philosophy

- European Jewish philosophy and Christian philosophy

- Mesoamerican Aztec philosophy

Philosophical progress

Many philosophical debates began in ancient times and are still debated today. Some (such as Colin McGinn) think that there has been no philosophical progress.[29] David Chalmers and others, by contrast, see progress in philosophy similar to that in science,[30] while Talbot Brewer argues that "progress" is the wrong standard by which to judge philosophical activity.[31]

Sub-fields

Academic philosophy has been subdivided in various ways. One widely used traditional division included three major branches:[2]

- Natural philosophy ("physics") was the study of the physical world (physis, lit: nature);

- Moral philosophy ("ethics") was the study of goodness, right and wrong, justice, and virtue (ethos, lit: custom);

- Metaphysical philosophy ("logos") was the study of existence, causation, God, logic, forms, and other abstract objects ("meta-physika" lit: "what comes after physics").[32]

These traditional branches, while not obsolete, are no longer used by most professional academics. Rather, contemporary academics tend divide the branches of philosophy by research topic, by historical period, or by philosophical tradition and thinker:

- Major topical branches include epistemology, logic, metaphysics, ethics, and aesthetics, etc.[33][34]

- Historical periods include ancient, medieval, early modern, modern, and contemporary, etc.[35]

- Philosophical traditions or schools of thought include analytic philosophy, phenomenology, Platonism, Confucianism, Taoism, etc.

These divisions are neither exhaustive, nor mutually exclusive. (A philosopher might specialize in Kantian epistemology, or Platonic aesthetics, or modern political philosophy.) Furthermore, these philosophical inquiries sometimes overlap with other inquiries such as science, religion, or mathematics.[36]

Some of the major sub-fields of philosophy are considered individually below.

Epistemology

Epistemology is the study of knowledge (Greek: episteme).[37] Epistemologists also ask: What is truth? Is knowledge justified true belief? Are any beliefs justified? Various kinds of putative knowledge include propositional knowledge (knowledge that something is the case), know-how (knowledge of how to do something), and acquaintance (familiarity with someone or something). Epistemologists examine some or all of these and ask whether knowledge is really possible.

Skepticism is the view that all or much of our putative knowledge is not really knowledge, but mere belief or falsehood. Skeptics argue that genuine, reliable knowledge about reality is completely impossible, or that such knowledge is to some degree difficult and rare. Important skeptics include Gorgias and (arguably) Friedrich Nietzsche.

If knowledge is possible, how is it best acquired? Are beliefs justified on the basis of perception, reason, or something else? Major epistemological positions include rationalism, empiricism, idealism, and mysticism.

- Rationalists, argue that reliable knowledge can come from reason and rational reflection, even apart from sensory experience or divine revelation. Important rationalists include Plato and Descartes.

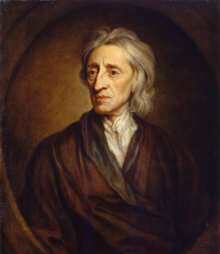

- Empiricists by contrast, argue that knowledge comes only or primarily or initially from sense-perception and ordinary experience. Examples include Aristotle, John Locke andDavid Hume.

- Idealists argue that knowledge is not merely the discovery of reality as it is "in itself"; rather that knowledge is partly or wholly a construction of the knower. Important idealists include Immanuel Kant.

- Mystics argue that some knowledge comes directly from altered states of consciousness (such as those produced by psychedelic drugs) or from mysterious planes of existence, such as supernatural or religious experiences. Examples include Teresa of Avila, and William James.

Logic

Logic is the study of reasoning and argument. An argument is "a connected series of statements intended to establish a proposition." The connected series of statements are called "premises", and the proposition being established is called the conclusion. For example:

- All humans are mortal. (premise)

- Socrates is a human. (premise)

- Therefore, Socrates is mortal. (conclusion)

In ordinary discourse, the conclusion of an argument may be signified by words like 'therefore', 'hence', 'ergo' and so on. Most people can successful infer that Socrates is mortal if they know that all humans are mortal and that Socrates is a human.

Good arguments are called "sound", which means the premises are true and the inference is "valid". An argument is valid if its conclusion necessarily follows from its premises. So, an argument is sound if its conclusion necessarily follows from its premises and its premises are true. Bad arguments are called "unsound". But correct reasoning only occurs when the premises of an argument are true, and the terms unambiguous, and the inference valid. Incorrect reasoning occurs when either the premises of an argument are false, or the terms are unclear, or the inference invalid, or any combination of these. Various types of faulty reasoning are called fallacies.

In classical Aristotelian logic, arguments are expressed in a natural language and may be classified as either deductive or inductive (or possibly abductive). Inductive reasoning makes conclusions or generalizations based on probabilistic reasoning. For example, if "90% of humans are right-handed" and "Joe is human" then "Joe is probably right-handed". In modern logics, arguments can be expressed in symbols. Propositional logic uses premises that are propositions, which are declarations that are either true or false, while predicate logic uses more complex premises called formulae that contain variables. Fields in logic include mathematical logic, philosophical logic, Modal logic, computational logic, and non-classical logics.

Because sound reasoning is an essential element of all sciences,[38] social sciences, and humanities disciplines, logic is classified as a formal science.

Metaphysics

Metaphysics is the study of the most general features of reality, such as existence, time, the relationship between mind and body, objects and their properties, wholes and their parts, events, processes, and causation. Traditional branches of metaphysics include cosmology, the study of the world in its entirety, and ontology, the study of being. Within metaphysics itself there are a wide range of differing philosophical theories. Idealism, for example, is the belief that reality is mentally constructed or otherwise immaterial while realism holds that reality, or at least some part of it, exists independently of the mind. Subjective idealism describes objects as no more than collections or "bundles" of sense data in the perceiver. The 18th-century philosopher George Berkeley contended that existence is fundamentally tied to perception with the phrase Esse est aut percipi aut percipere or "To be is to be perceived or to perceive".[39] In addition to the aforementioned views, however, there is also an ontological dichotomy within metaphysics between the concepts of particulars and universals. Particulars are those objects that are said to exist in space and time, as opposed to abstract objects, such as numbers. Universals are properties held by multiple particulars, such as redness or a gender. The type of existence, if any, of universals and abstract objects is an issue of serious debate within metaphysical philosophy. Realism is the philosophical position that universals do in fact exist, while nominalism is the negation, or denial of universals, abstract objects, or both.[40] Conceptualism holds that universals exist, but only within the mind's perception.[41] The question of whether or not existence is a predicate has been discussed since the Early Modern period. Essence is the set of attributes that make an object what it fundamentally is and without which it loses its identity. Essence is contrasted with accident: a property that the substance has contingently, without which the substance can still retain its identity.

Ethics

Ethics, or "moral philosophy," is the branch of axiology that studies good and bad, right and wrong.

The primary investigation of ethics or morality is the best way to live. The main branches of ethics are normative ethics, meta-ethics, and applied ethics.

- Normative ethics is about the principles of right and wrong. Major normative theories include deontology, consequentialism, virtue ethics, hedonism, anarchism, postmodernism, among others.

- Meta-ethics concerns the nature of ethical thought, such as the origins of the evaluative terms like 'good', whether there are any true evaluative judgments, and how such truths could be known. Major meta-ethical positions include moral anti-realism, moral realism, and constructivism.

- Applied ethics is about the application of principles to particular situations or acts, such as whether abortion, or nuclear proliferation, or theft are wrong. Applied ethical subdisciplines include bioethics, business ethics, machine ethics, and others.

A secondary investigation within ethics is whether any ethical questions can be answered. Moral nihilism, for example, is the denial that anything is moral or immoral. Moral relativism is a family of views that right and wrong are not universal but relative, either to cultures, ideologies, individuals, or something else.

Political Philosophy

This section should include only a brief summary of another article. |

Political philosophy is the study of government and the relationship of individuals (or families and clans) to communities including the state. It includes questions about justice, law, property, and the rights and obligations of the citizen. Politics and ethics are traditionally inter-linked subjects, as both discuss the question of what is good and how people should live.

From ancient times, and well beyond them, the roots of justification for political authority were inescapably tied to outlooks on human nature. In The Republic, Plato presented the argument that the ideal society would be run by a council of philosopher-kings, since those best at philosophy are best able to realize the good. Even Plato, however, required philosophers to make their way in the world for many years before beginning their rule at the age of fifty. For Aristotle, humans are political animals (i.e. social animals), and governments are set up to pursue good for the community. Aristotle reasoned that, since the state (polis) was the highest form of community, it has the purpose of pursuing the highest good. Aristotle viewed political power as the result of natural inequalities in skill and virtue. Because of these differences, he favored an aristocracy of the able and virtuous. For Aristotle, the person cannot be complete unless he or she lives in a community. His The Nicomachean Ethics and The Politics are meant to be read in that order. The first book addresses virtues (or "excellences") in the person as a citizen; the second addresses the proper form of government to ensure that citizens will be virtuous, and therefore complete. Both books deal with the essential role of justice in civic life.

Nicolas of Cusa rekindled Platonic thought in the early 15th century. He promoted democracy in Medieval Europe, both in his writings and in his organization of the Council of Florence. Unlike Aristotle and the Hobbesian tradition to follow, Cusa saw human beings as equal and divine (that is, made in God's image), so democracy would be the only just form of government. Cusa's views are credited by some as sparking the Italian Renaissance, which gave rise to the notion of "Nation-States".

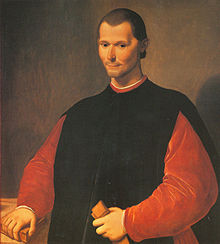

Later, Niccolò Machiavelli rejected the views of Aristotle and Thomas Aquinas as unrealistic. The ideal sovereign is not the embodiment of the moral virtues; rather the sovereign does whatever is successful and necessary, rather than what is morally praiseworthy. Thomas Hobbes also contested many elements of Aristotle's views. For Hobbes, human nature is essentially anti-social: people are essentially egoistic, and this egoism makes life difficult in the natural state of things. Moreover, Hobbes argued, though people may have natural inequalities, these are trivial, since no particular talents or virtues that people may have will make them safe from harm inflicted by others. For these reasons, Hobbes concluded that the state arises from a common agreement to raise the community out of the state of nature. This can only be done by the establishment of a sovereign, in which (or whom) is vested complete control over the community, and is able to inspire awe and terror in its subjects.[42]

Many in the Enlightenment were unsatisfied with existing doctrines in political philosophy, which seemed to marginalize or neglect the possibility of a democratic state. Jean-Jacques Rousseau was among those who attempted to overturn these doctrines: he responded to Hobbes by claiming that a human is by nature a kind of "noble savage", and that society and social contracts corrupt this nature. Another critic was John Locke. In Second Treatise on Government he agreed with Hobbes that the nation-state was an efficient tool for raising humanity out of a deplorable state, but he argued that the sovereign might become an abominable institution compared to the relatively benign unmodulated state of nature.[43] Following the doctrine of the fact-value distinction, due in part to the influence of David Hume and his student Adam Smith, appeals to human nature for political justification were weakened. Nevertheless, many political philosophers, especially moral realists, still make use of some essential human nature as a basis for their arguments.

Marxism is derived from the work of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Their idea that capitalism is based on exploitation of workers and causes alienation of people from their human nature, the historical materialism, their view of social classes, etc., have influenced many fields of study, such as sociology, economics, and politics. Marxism inspired the Marxist school of communism, which brought a huge impact on the history of the 20th century.

Aesthetics

Aesthetics deals with beauty, art, enjoyment, sensory-emotional values, perception, and matters of taste and sentiment. It is a branch of philosophy dealing with the nature of art, beauty, and taste, with the creation and appreciation of beauty.[44][45] It is more scientifically defined as the study of sensory or sensori-emotional values, sometimes called judgments of sentiment and taste.[46] More broadly, scholars in the field define aesthetics as "critical reflection on art, culture and nature."[47][48] More specific aesthetic theory, often with practical implications, relating to a particular branch of the arts is divided into areas of aesthetics such as art theory, literary theory, film theory and music theory. An example from art theory is aesthetic theory as a set of principles underlying the work of a particular artist or artistic movement: such as the Cubist aesthetic.[49]

Specialized branches

When philosophers ask general and fundamental questions about a specific topic (such as history, language, or religion) the resulting inquiry may become a specialized branch of philosophy.

- Philosophy of history refers to the theoretical aspect of history.

- Philosophy of language explores the nature, the origins, and the use of language.

- Philosophy of law (often called jurisprudence) explores the varying theories explaining the nature and the interpretations of law.

- Philosophy of education analyzes the definition and content of education, as well as the goals and challenges of educators.

- Philosophy of mind explores the nature of the mind, and its relationship to the body, and is typified by disputes between dualism and materialism. In recent years there has been increasing similarity between this branch of philosophy and cognitive science.

- Philosophy of religion explores questions that often arise in connection with one or several religions, including the soul, the afterlife, God, religious experiences, analysis of religious vocabulary and texts, and the relationship of religion and science.

- Philosophy of science explores the foundations, methods, history, implications, and purpose of science.

- Philosophy of biology is a subfield of philosophy of science and deals specifically with the metaphysical, epistemological, and ethical issues in the biomedical and life sciences.

- Philosophy of mathematics is the branch of philosophy that studies the philosophical assumptions, foundations, and implications of mathematics.

- Feminist philosophy explores questions surrounding gender, sexuality, and the body including the nature of feminism itself as a social and philosophical movement.

- Philosophy of film analyzes films and filmmakers for their philosophical content and style explores film (images, cinema, etc.) as a medium for philosophical reflection and expression.

- Philosophy of sport analyzes activities such as sports, games, and other forms of play as sociological and uniquely human activities.

- Philosophy of human nature analyzes the unique characteristics of human beings, such as rationality, politics, and culture.

- Metaphilosophy explores the aims of philosophy, its boundaries, and its methods.

Many academic disciplines have also generated philosophical inquiry. The relationship between between "X" and the "philosophy of X" is debated. Richard Feynman argues that the philosophy of a topic is irrelevant to the primary study of a topic, saying that "philosophy of science is as useful to scientists as ornithology is to birds." Curtis White, by contrast, argues that philosophical tools are essential to humanities, sciences, and social sciences.[50]

General history

This article may need to be cleaned up. It has been merged from History of philosophy. |

The history of philosophy is the compilation and study of philosophical ideas and concepts through time. Issues specifically related to history of philosophy might include (but are not limited to): How can changes in philosophy be accounted for historically? What drives the development of thought in its historical context? To what degree can philosophical texts from prior historical eras be understood even today? History of philosophy seeks to catalogue and classify such development. The goal is to understand the development of philosophical ideas through time.

Ancient philosophy

In Western philosophy, the spread of Christianity through the Roman Empire marked the ending of Hellenistic philosophy and ushered in the beginnings of Medieval philosophy, whereas in Eastern philosophy, the spread of Islam through the Arab Empire marked the end of Old Iranian philosophy and ushered in the beginnings of early Islamic philosophy. Genuinely philosophical thought, depending upon original individual insights, arose in many cultures roughly contemporaneously. Karl Jaspers termed the intense period of philosophical development beginning around the 7th century and concluding around the 3rd century BCE an Axial Age in human thought.

- Egypt and Babylon

There are authors who date the philosophical maxims of Ptahhotep before the 25th century. For instance, Pulitzer Prize–winning historian Will Durant dates these writings as early as 2880 BCE within The Story of Civilization: Our Oriental History. Durant claims that Ptahhotep could be considered the very first philosopher in virtue of having the earliest and surviving fragments of moral philosophy (i.e., "The Maxims of Ptah-Hotep").[51] Ptahhotep's grandson, Ptahhotep Tshefi, is traditionally credited with being the author of the collection of wise sayings known as The Maxims of Ptahhotep,[52] whose opening lines attribute authorship to the vizier Ptahhotep: "Instruction of the Mayor of the city, the Vizier Ptahhotep, under the Majesty of King Isesi". The origins of Babylonian philosophy can be traced back to the wisdom of early Mesopotamia, which embodied certain philosophies of life, particularly ethics, in the forms of dialectic, dialogues, epic poetry, folklore, hymns, lyrics, prose, and proverbs. The reasoning and rationality of the Babylonians developed beyond empirical observation.[53] The Babylonian text Dialog of Pessimism contains similarities to the agnostic thought of the sophists, the Heraclitean doctrine of contrasts, and the dialogues of Plato, as well as a precursor to the maieutic Socratic method of Socrates and Plato.[54] The Milesian philosopher Thales is also traditionally said to have studied philosophy in Mesopotamia.

- Ancient Chinese

Philosophy has had a tremendous effect on Chinese civilization, and throughout East Asia. The majority of Chinese philosophy originates in the Spring and Autumn and Warring States era, during a period known as the "Hundred Schools of Thought",[55] which was characterized by significant intellectual and cultural developments.[55] It was during this era that the major philosophies of China, Confucianism, Mohism, Legalism, and Taoism, arose, along with philosophies that later fell into obscurity, like Agriculturalism, Chinese Naturalism, and the Logicians. Of the many philosophical schools of China, only Confucianism and Taoism existed after the Qin Dynasty suppressed any Chinese philosophy that was opposed to Legalism. Confucianism is humanistic,[56] philosophy that believes that human beings are teachable, improvable and perfectible through personal and communal endeavour especially including self-cultivation and self-creation. Confucianism focuses on the cultivation of virtue and maintenance of ethics, the most basic of which are ren, yi, and li.[57] Ren is an obligation of altruism and humaneness for other individuals within a community, yi is the upholding of righteousness and the moral disposition to do good, and li is a system of norms and propriety that determines how a person should properly act within a community.[57]

Taoism focuses on establishing harmony with the Tao, which is origin of and the totality of everything that exists. The word "Tao" (or "Dao", depending on the romanization scheme) is usually translated as "way", "path" or "principle". Taoist propriety and ethics emphasize the Three Jewels of the Tao: compassion, moderation, and humility, while Taoist thought generally focuses on nature, the relationship between humanity and the cosmos (天人相应); health and longevity; and wu wei, action through inaction. Harmony with the Universe, or the origin of it through the Tao, is the intended result of many Taoist rules and practices.

- Ancient Graeco-Roman

Ancient Graeco-Roman philosophy is a period of Western philosophy, starting in the 6th century [c. 585] BC to the 6th century AD. It is usually divided into three periods: the pre-Socratic period, the Ancient Classical Greek period of Plato and Aristotle, and the post-Aristotelian (or Hellenistic) period. A fourth period that is sometimes added includes the Neoplatonic and Christian philosophers of Late Antiquity. The most important of the ancient philosophers (in terms of subsequent influence) are Plato and Aristotle.[58] It was said in Roman Ancient history that Pythagoras was the first man to call himself a philosopher, or lover of wisdom,[59] and Pythagorean ideas exercised a marked influence on Plato, and through him, all of Western philosophy. Plato and Aristotle, the first Classical Greek philosophers, did refer critically to other simple "wise men", which were called in Greek "sophists," and which were common before Pythagoras' time. From their critique it appears that a distinction was then established in their own Classical period between the more elevated and pure "lovers of wisdom" (the true Philosophers), and these other earlier and more common traveling teachers, who often also earned money from their craft.

The main subjects of ancient philosophy are: understanding the fundamental causes and principles of the universe; explaining it in an economical way; the epistemological problem of reconciling the diversity and change of the natural universe, with the possibility of obtaining fixed and certain knowledge about it; questions about things that cannot be perceived by the senses, such as numbers, elements, universals, and gods. Socrates is said to have been the initiator of more focused study upon the human things including the analysis of patterns of reasoning and argument and the nature of the good life and the importance of understanding and knowledge in order to pursue it; the explication of the concept of justice, and its relation to various political systems.[58] In this period the crucial features of the Western philosophical method were established: a critical approach to received or established views, and the appeal to reason and argumentation. This includes Socrates' dialectic method of inquiry, known as the Socratic method or method of "elenchus", which he largely applied to the examination of key moral concepts such as the Good and Justice. To solve a problem, it would be broken down into a series of questions, the answers to which gradually distill the answer a person would seek. The influence of this approach is most strongly felt today in the use of the scientific method, in which hypothesis is the first stage.

- Ancient Indian

The term Indian philosophy (Sanskrit: Darshanas), refers to any of several schools of philosophical thought that originated in the Indian subcontinent, including Hindu philosophy, Buddhist philosophy, and Jain philosophy. Having the same or rather intertwined origins, all of these philosophies have a common underlying themes of Dharma and Karma, and similarly attempt to explain the attainment of Moksha (liberation). They have been formalized and promulgated chiefly between 1000 BC to a few centuries AD.

India's philosophical tradition dates back to the composition of the Upanisads[60] in the later Vedic period (c. 1000-500 BCE). Subsequent schools (Skt: Darshanas) of Indian philosophy were identified as orthodox (Skt: astika) or non-orthodox (Skt: nastika), depending on whether or not they regarded the Vedas as an infallible source of knowledge.[61] In the history of the Indian subcontinent, following the establishment of a Vedic culture, the development of philosophical and religious thought over a period of two millennia gave rise to what came to be called the six schools of astika, or orthodox, Indian or Hindu philosophy. These schools have come to be synonymous with the greater religion of Hinduism, which was a development of the early Vedic religion. Schools of Hindu philosophy are Nyaya, Vaisesika, Samkhya, Yoga, Purva mimamsa and Vedanta. Other classifications also include Pashupata, Saiva, Raseśvara and Pāṇini Darśana with the other orthodox schools.[62] Jain philosophy revolves around the concept of ahimsā (non-violence). The major contribution of the Jain philosophy was the doctrine of Anekantavada (multiplicity of view points). According to the Jain epistemology, knowledge is of five kinds – sensory knowledge, scriptural knowledge, clairvoyance, telepathy, and omniscience.[63]

Buddhist philosophy and materialist (Cārvāka) philosophy rejected the idea of an eternal soul. Competition and integration between the various schools was intense during their formative years, especially between 500 BC to 200 AD. Some like the Jain, Buddhist, Shaiva and Vedanta schools survived, while others like Samkhya and Ajivika did not, either being assimilated or going extinct. The Sanskrit term for "philosopher" is dārśanika, one who is familiar with the systems of philosophy, or darśanas.[64]

- Ancient Persian

Persian philosophy can be traced back as far as Old Iranian philosophical traditions and thoughts, with their ancient Indo-Iranian roots. These were considerably influenced by Zarathustra's teachings. Throughout Iranian history and due to remarkable political and social influences such as the Macedonian, the Arab, and the Mongol invasions of Persia, a wide spectrum of schools of thought arose. These espoused a variety of views on philosophical questions, extending from Old Iranian and mainly Zoroastrianism-influenced traditions to schools appearing in the late pre-Islamic era, such as Manicheism and Mazdakism, as well as various post-Islamic schools. Iranian philosophy after Arab invasion of Persia is characterized by different interactions with the old Iranian philosophy, the Greek philosophy and with the development of Islamic philosophy. Illuminationism and the transcendent theosophy are regarded as two of the main philosophical traditions of that era in Persia. Zoroastrianism has been identified as one of the key early events in the development of philosophy.[65]

5th–16th centuries

- Medieval Europe

Medieval philosophy is the philosophy of Western Europe and the Middle East during the Middle Ages, roughly extending from the Christianization of the Roman Empire until the Renaissance.[66] Medieval philosophy is defined partly by the rediscovery and further development of classical Greek and Hellenistic philosophy, and partly by the need to address theological problems and to integrate the then widespread sacred doctrines of Abrahamic religion (Islam, Judaism, and Christianity) with secular learning. The history of western European medieval philosophy is traditionally divided into two main periods: the period in the Latin West following the Early Middle Ages until the 12th century, when the works of Aristotle and Plato were preserved and cultivated; and the "golden age"[citation needed] of the 12th, 13th and 14th centuries in the Latin West, which witnessed the culmination of the recovery of ancient philosophy, and significant developments in the field of philosophy of religion, logic and metaphysics.

The medieval era was disparagingly treated by the Renaissance humanists, who saw it as a barbaric "middle" period between the classical age of Greek and Roman culture, and the "rebirth" or renaissance of classical culture. Yet this period of nearly a thousand years was the longest period of philosophical development in Europe, and possibly the richest. Jorge Gracia has argued that "in intensity, sophistication, and achievement, the philosophical flowering in the thirteenth century could be rightly said to rival the golden age of Greek philosophy in the fourth century B.C."[67] Some problems discussed throughout this period are the relation of faith to reason, the existence and unity of God, the object of theology and metaphysics, the problems of knowledge, of universals, and of individuation.

Philosophers from the Middle Ages include the Christian philosophers Augustine of Hippo, Boethius, Anselm, Gilbert of Poitiers, Peter Abelard, Roger Bacon, Bonaventure, Thomas Aquinas, Duns Scotus, William of Ockham and Jean Buridan; the Jewish philosophers Maimonides and Gersonides; and the Muslim philosophers Alkindus, Alfarabi, Alhazen, Avicenna, Algazel, Avempace, Abubacer, Ibn Khaldūn, and Averroes. The medieval tradition of Scholasticism continued to flourish as late as the 17th century, in figures such as Francisco Suarez and John of St. Thomas. Aquinas, the father of Thomism, was immensely influential in Catholic Europe; he placed a great emphasis on reason and argumentation, and was one of the first to use the new translation of Aristotle's metaphysical and epistemological writing. His work was a significant departure from the Neoplatonic and Augustinian thinking that had dominated much of early Scholasticism.

- Renaissance

The Renaissance ("rebirth") was a period of transition between the Middle Ages and modern thought,[68] in which the recovery of classical texts helped shift philosophical interests away from technical studies in logic, metaphysics, and theology towards eclectic inquiries into morality, philology, and mysticism.[69][70] The study of the classics and the humane arts generally, such as history and literature, enjoyed a scholarly interest hitherto unknown in Christendom, a tendency referred to as humanism.[71][72] Displacing the medieval interest in metaphysics and logic, the humanists followed Petrarch in making man and his virtues the focus of philosophy.[73][74]

The study of classical philosophy also developed in two new ways. On the one hand, the study of Aristotle was changed through the influence of Averroism. The disagreements between these Averroist Aristotelians, and more orthodox catholic Aristotelians such as Albertus Magnus and Thomas Aquinas eventually contributed to the development of a "humanist Aristotelianism" developed in the Renaissance, as exemplified in the thought of Pietro Pomponazzi and Giacomo Zabarella. Secondly, as an alternative to Aristotle, the study of Plato and the Neoplatonists became common. This was assisted by the rediscovery of works which had not been well known previously in Western Europe. Notable Renaissance Platonists include Nicholas of Cusa, and later Marsilio Ficino and Giovanni Pico della Mirandola.[74]

The Renaissance also renewed interest in anti-Aristotelian theories of nature considered as an organic, living whole comprehensible independently of theology, as in the work of Nicholas of Cusa, Nicholas Copernicus, Giordano Bruno, Telesius, and Tommaso Campanella.[75] Such movements in natural philosophy dovetailed with a revival of interest in occultism, magic, hermeticism, and astrology, which were thought to yield hidden ways of knowing and mastering nature (e.g., in Marsilio Ficino and Giovanni Pico della Mirandola).[76] These new movements in philosophy developed contemporaneously with larger religious and political transformations in Europe: the Reformation and the decline of feudalism. Though the theologians of the Protestant Reformation showed little direct interest in philosophy, their destruction of the traditional foundations of theological and intellectual authority harmonized with a revival of fideism and skepticism in thinkers such as Erasmus, Montaigne, and Francisco Sanches.[77][78][79] Meanwhile, the gradual centralization of political power in nation-states was echoed by the emergence of secular political philosophies, as in the works of Niccolò Machiavelli (often described as the first modern political thinker, or a key turning point towards modern political thinking[80]), Thomas More, Erasmus, Justus Lipsius, Jean Bodin, and Hugo Grotius.[81][82]

- East Asia

Mid-Imperial Chinese philosophy is primarily defined by the development of Neo-Confucianism. During the Tang Dynasty, Buddhism from Nepal also became a prominent philosophical and religious discipline. (It should be noted that philosophy and religion were clearly distinguished in the West, whilst these concepts were more continuous in the East due to, for example, the philosophical concepts of Buddhism.)

Neo-Confucianism is a philosophical movement that advocated a more rationalist and secular form of Confucianism by rejecting superstitious and mystical elements of Daoism and Buddhism that had influenced Confucianism during and after the Han Dynasty.[83] Although the Neo-Confucianists were critical of Daoism and Buddhism,[84] the two did have an influence on the philosophy, and the Neo-Confucianists borrowed terms and concepts from both. However, unlike the Buddhists and Daoists, who saw metaphysics as a catalyst for spiritual development, religious enlightenment, and immortality, the Neo-Confucianists used metaphysics as a guide for developing a rationalist ethical philosophy.[85] Neo-Confucianism has its origins in the Tang Dynasty; the Confucianist scholars Han Yu and Li Ao are seen as forbears of the Neo-Confucianists of the Song Dynasty.[84] The Song Dynasty philosopher Zhou Dunyi is seen as the first true "pioneer" of Neo-Confucianism, using Daoist metaphysics as a framework for his ethical philosophy.[85] Elsewhere in East Asia, Japanese Philosophy began to develop as indigenous Shinto beliefs fused with Buddhism, Confucianism and other schools of Chinese philosophy and Indian philosophy. Similar to Japan, in Korean philosophy the emotional content of Shamanism was integrated into the Neo-Confucianism imported from China. Vietnamese philosophy was also influenced heavily by Confucianism in this period.[citation needed]

- India

The period between 5th and 9th centuries CE was the most brilliant epoch in the development of Indian philosophy as Hindu and Buddhist philosophies flourished side by side.[86] Of these various schools of thought the non-dualistic Advaita Vedanta emerged as the most influential[87] and most dominant school of philosophy.[88] The major philosophers of this school were Gaudapada, Adi Shankara and Vidyaranya. Advaita Vedanta rejects theism and dualism by insisting that "Brahman [ultimate reality] is without parts or attributes...one without a second." Since Brahman has no properties, contains no internal diversity and is identical with the whole reality, it cannot be understood as God.[89] Brahman though being indescribable is at best described as Satchidananda (merging "Sat" + "Chit" + "Ananda", i.e., Existence, Consciousness and Bliss) by Shankara. Advaita ushered a new era in Indian philosophy and as a result, many new schools of thought arose in the medieval period. Some of them were Visishtadvaita (qualified monism), Dvaita (dualism), Dvaitadvaita (dualism-nondualism), Suddhadvaita (pure non-dualism), Achintya Bheda Abheda and Pratyabhijña (the recognitive school).

- Middle East

In early Islamic thought, which refers to philosophy during the "Islamic Golden Age", traditionally dated between the 8th and 12th centuries, two main currents may be distinguished. The first is Kalam, that mainly dealt with Islamic theological questions. These include the Mu'tazili and Ash'ari. The other is Falsafa, that was founded on interpretations of Aristotelianism and Neoplatonism. There were attempts by later philosopher-theologians at harmonizing both trends, notably by Ibn Sina (Avicenna) who founded the school of Avicennism, Ibn Rushd (Averroës) who founded the school of Averroism, and others such as Ibn al-Haytham (Alhacen) and Abū Rayhān al-Bīrūnī. Avicenna argued his "Floating Man" thought experiment concerning Self-awareness, in which a man prevented of sense experience by being blindfolded and free falling would still be aware of his existence.[90] In epistemology, Ibn Tufail wrote the novel Hayy ibn Yaqdhan and in response Ibn al-Nafis wrote the novel Theologus Autodidactus. Both were concerning autodidacticism as illuminated through the life of a feral child spontaneously generated in a cave on a desert island.

- Mesoamerica

Aztec philosophy was the school of philosophy developed by the Aztec Empire. The Aztecs had a well-developed school of philosophy, perhaps the most developed in the Americas and in many ways comparable to Greek philosophy, even amassing more texts than the ancient Greeks.[91] Aztec philosophy focused on dualism, monism, and aesthetics, and Aztec philosophers attempted to answer the main Aztec philosophical question of how to gain stability and balance in an ephemeral world. Aztec philosophy saw the concept of Ometeotl as a unity that underlies the universe. Ometeotl forms, shapes, and is all things. Even things in opposition—light and dark, life and death—were seen as expressions of the same unity, Ometeotl. The belief in a unity with dualistic expressions compares with similar dialectical monist ideas in both Western and Eastern philosophies.[92] Aztec priests had a panentheistic view of religion but the popular Aztec religion maintained polytheism. Priests saw the different gods as aspects of the singular and transcendent unity of teotl but the masses were allowed to practice polytheism without understanding the true, unified nature of the Aztec gods.[92]

- Africa

Ethiopian philosophy is the philosophical corpus of the territories of present-day Ethiopia and Eritrea. Besides via oral tradition, it was preserved early on in written form through Ge'ez manuscripts. This philosophy occupies a unique position within African philosophy. The character of Ethiopian philosophy is determined by the particular conditions of evolution of the Ethiopian culture. Thus, Ethiopian philosophy arises from the confluence of Greek and Patristic philosophy with traditional Ethiopian modes of thought. Because of the early isolation from its sources of Abrahamic spirituality – Byzantium and Alexandria – Ethiopia received some of its philosophical heritage through Arabic versions. The sapiential literature developed under these circumstances is the result of a twofold effort of creative assimilation: on one side, of a tuning of Orthodoxy to traditional modes of thought (never eradicated), and vice versa, and, on the other side, of absorption of Greek pagan and early Patristic thought into this developing Ethiopian-Christian synthesis. As a consequence, the moral reflection of religious inspiration is prevalent, and the use of narrative, parable, apothegm and rich imagery is preferred to the use of abstract argument. This sapiential literature consists in translations and adaptations of some Greek texts, namely of the Physiolog (cca. 5th century A.D.), The Life and Maxims of Skendes (11th century A.D.) and The Book of the Wise Philosophers (1510/22). In the 17th century, the religious beliefs of Ethiopians were challenged by King Suseynos' adoption of Catholicism, and by a subsequent presence of Jesuit missionaries. The attempt to forcefully impose Catholicism upon his constituents during Suseynos' reign inspired further development of Ethiopian philosophy during the 17th century. Zera Yacob (1599–1692) is the most important exponent of this renaissance. His treatise Hatata (1667) is a work often included in the narrow canon of universal philosophy.

Early modern and modern philosophy

Chronologically, the early modern era of Western philosophy is usually identified with the 17th and 18th centuries, with the 18th century often being referred to as the Enlightenment.[93] Modern philosophy is distinguished from its predecessors by its increasing independence from traditional authorities such as the Church, academia, and Aristotelianism;[94][95] a new focus on the foundations of knowledge and metaphysical system-building;[96][97] and the emergence of modern physics out of natural philosophy.[98] Other central topics of philosophy in this period include the nature of the mind and its relation to the body, the implications of the new natural sciences for traditional theological topics such as free will and God, and the emergence of a secular basis for moral and political philosophy.[99] These trends first distinctively coalesce in Francis Bacon's call for a new, empirical program for expanding knowledge, and soon found massively influential form in the mechanical physics and rationalist metaphysics of René Descartes.[100]

Thomas Hobbes was the first to apply this methodology systematically to political philosophy and is the originator of modern political philosophy, including the modern theory of a "social contract".[101][102] The academic canon of early modern philosophy generally includes Descartes, Spinoza, Leibniz, Locke, Berkeley, Hume, and Kant,[103][104][105] though influential contributions to philosophy were made by many thinkers in this period, such as Galileo Galilei, Pierre Gassendi, Blaise Pascal, Nicolas Malebranche, Isaac Newton, Christian Wolff, Montesquieu, Pierre Bayle, Thomas Reid, Jean d'Alembert, and Adam Smith. Jean-Jacques Rousseau was a seminal figure in initiating reaction against the Enlightenment. The approximate end of the early modern period is most often identified with Immanuel Kant's systematic attempt to limit metaphysics, justify scientific knowledge, and reconcile both of these with morality and freedom.[106][107][108]

- 19th-century philosophy

Later modern philosophy is usually considered to begin after the philosophy of Immanuel Kant at the beginning of the 19th century.[109] German philosophy exercised broad influence in this century, owing in part to the dominance of the German university system.[110] German idealists, such as Johann Gottlieb Fichte, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, and Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling, transformed the work of Kant by maintaining that the world is constituted by a rational or mind-like process, and as such is entirely knowable.[111] Arthur Schopenhauer's identification of this world-constituting process as an irrational will to live influenced later 19th- and early 20th-century thinking, such as the work of Friedrich Nietzsche. After Hegel's death in 1831, 19th-century philosophy largely turned against idealism in favor of varieties of philosophical naturalism, such as the positivism of Auguste Comte, the empiricism of John Stuart Mill, and the materialism of Karl Marx. Logic began a period of its most significant advances since the inception of the discipline, as increasing mathematical precision opened entire fields of inference to formalization in the work of George Boole and Gottlob Frege.[112] Other philosophers who initiated lines of thought that would continue to shape philosophy into the 20th century include:

- Gottlob Frege and Henry Sidgwick, whose work in logic and ethics, respectively, provided the tools for early analytic philosophy.

- Charles Sanders Peirce and William James, who founded pragmatism.

- Søren Kierkegaard and Friedrich Nietzsche, who laid the groundwork for existentialism and post-structuralism.

- 20th-century and 21st-century philosophy

Within the last century, philosophy has increasingly become a professional discipline practiced within universities, like other academic disciplines. Accordingly, it has become less general and more specialized. In the view of one prominent recent historian: "Philosophy has become a highly organized discipline, done by specialists primarily for other specialists. The number of philosophers has exploded, the volume of publication has swelled, and the subfields of serious philosophical investigation have multiplied. Not only is the broad field of philosophy today far too vast to be embraced by one mind, something similar is true even of many highly specialized subfields."[113] Some philosophers argue that this professionalization has negatively affected the discipline.[114]

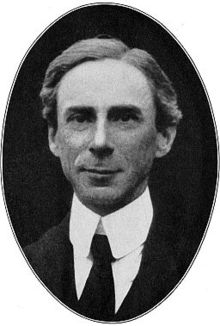

In the English-speaking world, analytic philosophy became the dominant school for much of the 20th century. In the first half of the century, it was a cohesive school, shaped strongly by logical positivism, united by the notion that philosophical problems could and should be solved by attention to logic and language. The pioneering work of Bertrand Russell was a model for the early development of analytic philosophy, moving from a rejection of the idealism dominant in late 19th-century British philosophy to an neo-Humean empiricism, strengthened by the conceptual resources of modern mathematical logic.[115][116][117] In the latter half of the 20th century, analytic philosophy diffused into a wide variety of disparate philosophical views, only loosely united by historical lines of influence and a self-identified commitment to clarity and rigor. The post-war transformation of the analytic program led in two broad directions: on one hand, an interest in ordinary language as a way of avoiding or redescribing traditional philosophical problems, and on the other, a more thoroughgoing naturalism that sought to dissolve the puzzles of modern philosophy via the results of the natural sciences (such as cognitive psychology and evolutionary biology). The shift in the work of Ludwig Wittgenstein, from a view congruent with logical positivism to a therapeutic dissolution of traditional philosophy as a linguistic misunderstanding of normal forms of life, was the most influential version of the first direction in analytic philosophy.[118][119] The later work of Russell and the philosophy of Willard Van Orman Quine are influential exemplars of the naturalist approach dominant in the second half of the 20th century.[120][121][122][123] But the diversity of analytic philosophy from the 1970s onward defies easy generalization: the naturalism of Quine and his epigoni was in some precincts superseded by a "new metaphysics" of possible worlds, as in the influential work of David Lewis.[124][125] Recently, the experimental philosophy movement has sought to reappraise philosophical problems through social science research techniques.

On continental Europe, no single school or temperament enjoyed dominance. The flight of the logical positivists from central Europe during the 1930s and 1940s, however, diminished philosophical interest in natural science, and an emphasis on the humanities, broadly construed, figures prominently in what is usually called "continental philosophy". 20th-century movements such as phenomenology, existentialism, modern hermeneutics, critical theory, structuralism, and poststructuralism are included within this loose category. The founder of phenomenology, Edmund Husserl, sought to study consciousness as experienced from a first-person perspective,[126][127] while Martin Heidegger drew on the ideas of Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, and Husserl to propose an unconventional existential approach to ontology.[128][129] In the Arabic-speaking world, Arab nationalist philosophy became the dominant school of thought, involving philosophers such as Michel Aflaq, Zaki al-Arsuzi, Salah al-Din al-Bitar of Ba'athism and Sati' al-Husri.

Western history

Therefore, the history of philosophy is inseparable from global history. Karl Jaspers termed the intense period of philosophical development beginning around the 7th century and concluding around the 3rd century BCE an Axial Age in human thought. Philosophy or wisdom arises simultaneously with science, mathematics, mythology, art, religion, and political society.

Western philosophy has a long history, conventionally divided into four large eras – the Ancient, Medieval, Modern, and Contemporary. The Ancient era runs through the fall of Rome and includes the Greek philosophers such as Plato and Aristotle. The Medieval period runs until roughly the late 15th century and the Renaissance. The "Modern" is a word with more varied use, which includes everything from Post-Medieval through the specific period up to the 20th century. Contemporary philosophy encompasses the philosophical developments of the 20th century up to the present day.

Ancient philosophy

- Pre-Socratics

Western Philosophy is generally said to begin in the Greek cities of western Asia Minor (Ionia) with Thales of Miletus, who was active around 585 B.C. and left us the opaque dictum, "all is water." His most noted students were respectively Anaximander (all is apeiron (roughly, the unlimited)) and Anaximenes of Miletus ("all is air").

Pythagoras, from the island of Samos off the coast of Ionia, later lived at Croton in southern Italy (Magna Graecia). Pythagoreans hold that "all is number," giving formal accounts in contrast to the previous material of the Ionians. They also believe in metempsychosis, the transmigration of souls, or reincarnation.

- Being and becoming

The first true philosophic dialectic occurs between the "becoming" of Heraclitus ("all is fire", "everything flows," all is chaotic and transitory) of Ephesus in Ionia and the "being" of Parmenides (all is One, change is impossible) of Elea in Magna Graecia. His student Zeno argued against motion with his famous paradoxes. Heraclitus also introduced the concept of logos.

- Pluralism

Other thinkers and schools appeared throughout Greece over the next few centuries. Among the most important was the pluralism of Anaxagoras. In response to Parmenides on the impossibility of change, Anaxagoras described the world as a mixture of primary imperishable ingredients, where material variation was never caused by an absolute presence of a particular ingredient, but rather by its relative preponderance over the other ingredients; in his words, "each one is... most manifestly those things of which there are the most in it".[130] He introduced the concept of Nous (Mind) as an ordering force, which moved and separated out the original mixture, which was homogeneous, or nearly so.

Empedocles also proposed powers called Love and Hate which would act as forces to bring about the mixture and separation of the elements, more discreet than in the mixture of Anaxagoras. Empedocles' philosophy is best known for being the originator of the cosmogenic theory of the four Classical elements. Empedocles is generally considered the last Greek philosopher to record his ideas in verse. Some of his work survives, more than in the case of any other Presocratic philosopher.

- Atomism and Sophistry

There were also the Sophists, who became known, perhaps unjustly, for claiming that truth was no more than opinion and for teaching people to argue fallaciously to prove whatever conclusions they wished. Most famous them of was Protagoras who left us the dictum "man is the measure of all things." Another school was the atomists such as Leucippus and Democritus, wherein the world is a composite of innumerable interacting parts.

- Athens

This whole philosophical movement gradually became more concentrated in Athens, which had become the dominant city-state in Greece. There is considerable discussion about why Athenian culture encouraged philosophy. It is known from Plato's writings that many sophists maintained schools of debate, were respected members of society, and were well paid by their students. Orators influenced Athenian history, possibly even causing its failure (See Battle of Lade). Another theory explains the birth of philosophical debate in Athens with the presence of a slave labor workforce which performed the necessary functions that would otherwise have consumed the time of the free male citizenry. Freed from working in the fields or other manual economic activities, they were able to participate in the assemblies of Athens and spend long periods in discussions on popular philosophical questions. Students of Sophists needed to acquire the skills of oration in order to influence the Athenian Assembly and thereby increase respect and wealth. In response, the subjects and methods of debate became highly developed by the Sophists.

- Socrates

The key figure in transforming Greek philosophy into a unified and continuous project – one still being pursued today – is Socrates, who studied under several Sophists. It is said that following a visit to the Oracle of Delphi he spent much of his life questioning anyone in Athens who would engage him, in order to disprove the oracular prophecy that there would be no man wiser than Socrates. Through these live dialogues, he examined common but critical concepts that lacked clear or concrete definitions, such as beauty and truth, and the virtues of piety, wisdom, temperance, courage, and justice. Socrates' awareness of his own ignorance allowed him to discover his errors as well as the errors of those who claimed knowledge based upon falsifiable or unclear precepts and beliefs. He wrote nothing, but inspired many disciples, including many sons of prominent Athenian citizens (including Plato), which led to his trial and execution in 399 B.C. on the charge that his philosophy and sophistry were undermining the youth, piety, and moral fiber of the city. He was offered a chance to flee from his fate but chose to remain in Athens, abide by his principles, and drink the poison hemlock.

- Plato

Socrates' most important student was Plato, who founded the Academy of Athens and wrote a number of dialogues, which applied the Socratic method of inquiry to examine philosophical problems. Some central ideas of Plato's dialogues are the Theory of Forms, i.e., that the mind is imbued with an innate capacity to understand and contemplate concepts from a higher order preeminent world, concepts more real, permanent, and universal than or representative of the things of this world, which are only changing and temporal; the idea of the immortal soul being superior to the body; the idea of evil as simple ignorance of truth; that true knowledge leads to true virtue; that art is subordinate to moral purpose; and that the society of the city-state should be governed by a merit class of propertyless philosopher kings, with no permanent wives or paternity rights over their children, and be protected by an athletically gifted, honorable, duty bound military class. In the later dialogues Socrates figures less prominently, but Plato had previously woven his own thoughts into some of Socrates' words. Interestingly, in his most famous work, The Republic, Plato critiques democracy, condemns tyranny, and proposes a three tiered merit based structure of society, with workers, guardians and philosophers, in an equal relationship, where no innocents would ever be put to death again, citing the philosophers' relentless love of truth and knowledge of the forms or ideals, concern for general welfare and lack of propertied interest as causes for their being suited to govern.

- Aristotle

Plato's most outstanding student was Aristotle, perhaps the first truly systematic philosopher. Aristotelian logic was the first type of logic to attempt to categorize every valid syllogism. A syllogism is a form of argument that is guaranteed to be accepted, because it is known (by all educated persons) to be valid. A crucial assumption in Aristotelian logic is that it has to be about real objects. Two of Aristotle's syllogisms are invalid to modern eyes. For example, "All A are B. All A are C. Therefore, some B are C." This syllogism fails if set A is empty, but there are real members of set B. In Aristotle's syllogistic logic you could say this, because his logic should only be used for things that really exist ("no empty classes").

The application of Aristotelian logic is preceded by having the student memorize a rather large set of syllogisms. The memorization proceeded from diagrams, or learning a key sentence, with the first letter of each word reminding the student of the names of the syllogisms. Each syllogism had a name, for example: modus ponens had the form of "If A is true, then B is true. A is true, therefore B is true." Most university students of logic memorized Aristotle's 19 syllogisms of two subjects, permitting them to validly connect a subject and object. A few logicians developed systems with three subjects, or described a way of elaborating the rules of three subjects.

- Hellenistic

Other pupils of Socrates aside from Plato founded their own schools, such as Euclid of Megara. The Hellenistic period involves the Cyrenaics of Aristippus and Cynics of Antisthenes resolving themselves in the Epicurean and Stoic schools. Skepticism also belongs to this period.

Medieval philosophy

The history of western medieval philosophy is generally divided into two periods, early medieval philosophy, which started with St. Augustine in the mid 4th century and lasted until the recovery in the 13th century West of a great bulk of Aristotle's works and their subsequent translation into Latin from the Arabic and Greek, and high medieval philosophy, which came about as a result of the recovery of Aristotle. This period, which lasted a mere century and a half compared to the nine centuries of the early period, came to a close around the time of William of Ockham in the middle of the 14th century. Western medieval philosophy was primarily concerned with implementing the Christian faith with philosophical reason, that is, "baptizing" reason. Early medieval philosophy was influenced by the likes of Stoicism, neo-Platonism, but, above all, the philosophy of Plato himself. The prominent figure of this period was St. Augustine who adopted Plato's thought and Christianized it in the 4th century and whose influence dominated medieval philosophy perhaps up to end of the era but was checked with the arrival of Aristotle's texts. Augustinianism was the preferred starting point for most philosophers (including the great St. Anselm of Canterbury) up until the 13th century. During the later years of the early medieval period and throughout the years of the high medieval period, there was a great emphasis on the nature of God and the application of Aristotle's logic and thought to every area of life. Attempts were made to reconcile these three things by means of scholasticism. One continuing interest in this time was to prove the existence of God, through logic alone, if possible. The point of this exercise was not so much to justify belief in God, since in the view of medieval Christianity this was self-evident, but to make classical philosophy, with its extra-biblical pagan origins, respectable in a Christian context.

One monumental effort to overcome mere logical argument at the beginning of the high medieval period was to follow Aristotelian demonstration by starting from effects and reasoning up to their causes. This took the form of the cosmological argument, conventionally attributed to St. Thomas Aquinas. The argument roughly is that everything that exists has a cause. But since there could not be an infinite chain of causes back into the past, there must have been an uncaused "first cause." This is God. Aquinas also adapted this argument to prove the goodness of God. Everything has some goodness, and the cause of each thing is better than the thing caused. Therefore, the first cause is the best possible thing. Similar arguments were used to prove God's power and uniqueness. Another important argument for proof of the existence of God was the ontological argument, advanced by St. Anselm. Basically, it says that God is that than which nothing greater can be thought. There is nothing that simply exists in the mind that can be said to be greater than something that enjoys existence in reality. Hence the greatest thing that the mind can conceive of must exist in reality. Therefore, God exists. This argument has been used in different forms by philosophers from Descartes forward. In addition to St. Thomas Aquinas, St. Augustine and St. Anselm, other important names from the medieval period include Blessed John Duns Scotus, St. Bonaventure, Anicius Manlius Severinus Boëthius, and Pierre Abélard. The definition of the word "philosophy" in English has changed over the centuries. In medieval times, any research outside the fields of theology or medicine was called "philosophy", hence the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society is a scientific journal dating from 1665, the Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) degree covers a wide range of subjects, and the Cambridge Philosophical Society is actually concerned with what would now be called science and not modern philosophy.

- Renaissance philosophy

This section has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Contemporary philosophical historiography emphasizes a great "gap" between Middle Ages and Modern thought. And often this "gap" is used as a mean to characterize the meaning of the word "modern" used in "modern philosophy". As a matter of fact, if in History Middle Ages are said to end symbolically with the Columbus' voyages (1492), periodisation in Philosophy is not necessarily reducible to the broader one. Between the development of High Scholasticism (13th and part of the 14th centuries) and the empiricists-rationalists disputes charactering modern philosophy (starting in the 17th century) several thinkers developed transitional systems of thought. One main focus was on emancipating from the supremacy of theology on the other branches of the humanities, including aesthetics, rhetorics and the beginning of natural observations. Along with the figurative arts, music, vernacular languages and literatures, and the Christian religion, philosophy was greatly renewed in what is usually referred to as the Renaissance. This cultural movement, spreading throughout Europe from Italy, influenced philosophy as much as architecture, the visual arts, and literature. Two circumstancial events promoted an emancipation of philosophy from the Catholic theology (which had dominated European thought throughout the Middle Ages): the concurrent Protestant Reformation, and the use of vernacular languages (Italian, English, French) instead of Latin in treatises and public discussions. If most medieval philosophers were priests and monks, early and late Renaissance philosophers were a more heterogeneous population, including rhetors, magicians and astrologues, early empirical scientists, poets, and philologists. If there was one common theme among these Renaissance thinkers it would have to be a concern for humanity (and the humanities) and the search for human specificity. The study of humanae litterae overcame that of divinae litterae, and opened the way for modern skepticism and science.

Many philosophers from the Renaissance are today read and remembered, even though often they are not often categorized into a single category. In particular, those Renaissance thinkers who were especially oriented towards empiricism and rationalism, are often seen as early (Galileo Galilei) or very early (Machiavelli) modern philosophers. On the other hand, those heavily influenced by esoteric traditions (like Giovanni Pico della Mirandola, Marsilio Ficino and even Nicholas of Cusa and Giordano Bruno) are often seen as (very) late Medieval philosophers. This categorisation may however seem to interpret two centuries of philosophy on the basis of a contemporary discrimination ("esoteric"/"scientific"). A few thinkers who do not clearly fall into either of these categories are usually fully recognized as Renaissance philosophers, including Montaigne, Tommaso Campanella, Telesius, Erasmus, and Thomas More.

Modern philosophy

As with many periodizations, there are multiple current usages for the term "Modern Philosophy" that exist in practice. One – common – usage is to date modern philosophy from the "Age of Reason", where systematic philosophy became common, excluding Erasmus and Machiavelli (writing in the 15th century) as "modern philosophers", and traditionally considering Hobbes (writing in the 17th century) as the first truly "modern" philosopher. The grounding of philosophy in problems of knowledge, rather than problems of metaphysics, dominates the era, exemplified most perhaps in the philosophy of René Descartes[131]

Another is to date it, the way the entire larger modern period is dated, from the Renaissance. There is also the lumpers/splitters problem, namely that some works split philosophy into more periods than others: one author might feel a strong need to differentiate between "The Age of Reason" or "Early Modern Philosophers" and "The Enlightenment"; another author might write from the perspective that 1600–1800 is essentially one continuous evolution, and therefore a single period. Wikipedia's philosophy section therefore hews more closely to centuries as a means of avoiding long discussions over periods, but it is important to note the variety of practice that occurs.

17th-century philosophy is dominated by the need to organize philosophy on rational, skeptical, logical and axiomatic grounds, such as the work of Descartes, Blaise Pascal, and Thomas Hobbes. This type of philosophy attempts to integrate religious belief into philosophical frameworks, and, often to combat atheism or other skeptical beliefs, by adopting the idea of material reality, and the dualism between spirit and material. The extension, and reaction, against this would be the monism of George Berkeley (idealism) and Benedict de Spinoza (dual aspect theory). It was during this time period that the empiricism was developed as an alternative to skepticism by John Locke, George Berkeley and others. It should be mentioned that John Locke and Thomas Hobbes developed their well known political philosophies during this time, as well.

The 18th-century philosophy article deals with the period often called the early part of "The Enlightenment" in the shorter form of the word, and centers on the rise of systematic empiricism, following after Sir Isaac Newton's natural philosophy. Thus the philosophes like Diderot, Voltaire, Rousseau, and Montesquieu and the political philosophies embodied by and influencing the American Revolution and American Enlightenment, such as Beccaria, are part of The Enlightenment. Immanuel Kant perhaps is most prominent in the period, seeking a large, systematic reconciliation of rationalism and empiricism with claim that the mind structured experience. Kant took himself to have anointed a Copernican Revolution in philosophy. Other prominent philosophers of this time period were David Hume and Adam Smith, who, along with Francis Hutcheson and Thomas Reid, were the primary philosophers of the Scottish Enlightenment; and Thomas Paine and Thomas Jefferson, who were philosophers of the American Enlightenment. Edmund Burke was influenced by the Scottish Enlightenment, namely Hume's skepticism and reliance on tradition and the passions, and while supporting the American Revolution based on the established rights of Englishmen, rejected the "natural rights" claims of the Enlightenment and vehemently rejected the Rationalism of the French Revolution (see Reflections on the Revolution in France). The 19th century took the radical notions of self-organization and intrinsic order from Goethe and Kantian metaphysics, and proceeded to produce a long elaboration on the tension between systematization and organic development. Foremost was the work of Hegel, whose Logic and Phenomenology of Spirit produced a "dialectical" framework for ordering of knowledge. The 19th century would also include Schopenhauer's affirmation of the will, drawing parallels to Eastern philosophy. Schopenhauer profoundly influenced Friedrich Nietzsche.

Also in the 19th century, the Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard took philosophy in a new direction by focusing less on abstract concepts and more on what it means to be an existing individual. His work provided impetus for many 20th century philosophical movements, including existentialism. As with the 18th century, it would be developments in science that would arise from, and then challenge, philosophy: most importantly the work of Charles Darwin, which was based on the idea of organic self-regulation found in philosophers such as Smith, but fundamentally challenged established conceptions.

Contemporary approaches

There are at least three major contemporary approaches to academic philosophy:[132] Analytic philosophy, continental philosophy, and pragmatism. These three are not exhaustive, nor necessarily mutually exclusive.

The 20th century deals with the upheavals produced by a series of conflicts within philosophical discourse over the basis of knowledge, with classical certainties overthrown, and new social, economic, scientific and logical problems. 20th century philosophy was set for a series of attempts to reform and preserve, and to alter or abolish, older knowledge systems. Seminal figures include Gottlob Frege, Bertrand Russell, Ludwig Wittgenstein, Martin Heidegger, Jean-Paul Sartre, and Edmund Husserl. Since the Second World War, contemporary philosophy has been divided mostly into analytic and continental traditions; the former carried in the English speaking world and the latter on the continent of Europe. The perceived conflict between continental and analytic schools of philosophy remains prominent, despite increasing skepticism regarding the distinction's usefulness. Knowledge and its basis has been a central concern, as seen from the work of Heidegger, Russell, G. E. Moore, Karl Popper, and Claude Lévi-Strauss.

The philosophy of the present century is difficult to clarify due to its immaturity. A number of surviving 20th century philosophers have established themselves as early voices of influence in the 21st. These include Noam Chomsky, Saul Kripke, and Jürgen Habermas. A variety of new topics have risen to the stage in analytic philosophy, orienting much of contemporary discourse in the field of ethics. New inquiries consider, for example, the ethical implications of new media and information exchange. Such developments have rekindled interest in the philosophy of technology and science. There has been increased enthusiasm for highly specialized areas in philosophy of science, such as in the Bayesian school of epistemology.

Analytic

The term analytic philosophy roughly designates a group of philosophical methods that stress detailed argumentation, attention to semantics, use of classical logic and non-classical logics and clarity of meaning above all other criteria. Some have held that philosophical problems arise through misuse of language or because of misunderstandings of the logic of our language, while some maintain that there are genuine philosophical problems and that philosophy is continuous with science. Michael Dummett in his Origins of Analytical Philosophy makes the case for counting Gottlob Frege's The Foundations of Arithmetic as the first analytic work, on the grounds that in that book Frege took the linguistic turn, analyzing philosophical problems through language. Bertrand Russell and G.E. Moore are also often counted as founders of analytic philosophy, beginning with their rejection of British idealism, their defense of realism and the emphasis they laid on the legitimacy of analysis. Russell's classic works The Principles of Mathematics,[133]