Phentolamine

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Regitine, Oraverse |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| Routes of administration | intravenous, intramuscular, eye drops |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Metabolism | Liver |

| Elimination half-life | 19 minutes |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.049 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C17H19N3O |

| Molar mass | 281.359 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Phentolamine, sold under the brand name Regitine among others, is a reversible[1] nonselective α-adrenergic antagonist.[2]

Mechanism

[edit]Its primary action is vasodilation due to α1 blockade.[3]

Non-selective α-blockers can cause a much more pronounced reflex tachycardia than the selective α1 blockers. Like the selective α1 blockers, phentolamine causes a relaxation of systemic vasculature, leading to hypotension. This hypotension is sensed by the baroreceptor reflex, which results in increased sympathetic nerve firing on the heart, releasing norepinephrine. In response, the β1 adrenergic receptors on the heart increase their rate, contractility, and dromotropy, which help to offset the decrease in systemic blood pressure. Unlike the α1 selective blockers, phentolamine also inhibits the α2 receptors, which function predominantly as presynaptic negative feedback for norepinephrine release. By abolishing this negative feedback phentolamine leads to even less regulated norepinephrine release, which results in a more drastic increase in heart rate.[4]

Uses

[edit]The primary application for phentolamine is for the control of hypertensive emergencies, most notably due to pheochromocytoma.[5]

It also has usefulness in the treatment of cocaine-induced cardiovascular complications, where one would generally avoid β-blockers (e.g. metoprolol), as they can cause unopposed α-adrenergic mediated coronary vasoconstriction, worsening myocardial ischemia and hypertension.[6][7] Phentolamine is not a first-line agent for this indication. Phentolamine should only be given to patients who do not fully respond to benzodiazepines, nitroglycerin, and calcium channel blockers.[8][9]

When given by injection it causes blood vessels to dilate, thereby increasing blood flow. When injected into the penis (intracavernosal), it increases blood flow to the penis, which results in an erection.[10]

It may be stored in crash carts to counteract severe peripheral vasoconstriction secondary to extravasation of peripherally placed vasopressor infusions, typically of norepinephrine. Epinephrine infusions are less vasoconstrictive than norepinephrine as they primarily stimulate β receptor more than α receptors, but the effect remains dose-dependent.

Phentolamine also has diagnostic and therapeutic roles in complex regional pain syndrome (reflex sympathetic dystrophy).[11]

Phentolamine is marketed in the dental field as a local anesthetic reversal agent. Branded as OraVerse, it is a phentolamine mesylate injection designed to reverse the local vasoconstrictor properties used in many local anesthetics to prolong anesthesia.[12]

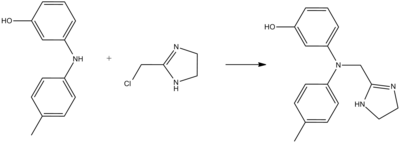

Chemistry

[edit]Phentolamine can be synthesized by alkylation of 3-(4-methylanilino)phenol using 2-chloromethylimidazoline:[13][14]

Adverse effects

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Jewell JR, Longworth DL, Stoller JK, Casey D (2003). The Cleveland Clinic internal medicine case reviews. Hagerstown, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 32. ISBN 0-7817-4266-8.

- ^ Phentolamine at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- ^ Brock G (2000). "Oral phentolamine (Vasomax)". Drugs of Today. 36 (2–3). Barcelona, Spain: 121–4. doi:10.1358/dot.2000.36.2-3.568785. PMID 12879109.

- ^ Shen H (2008). Illustrated Pharmacology Memory Cards: PharMnemonics. Minireview. p. 14. ISBN 978-1-59541-101-3.

- ^ Tuncel M, Ram VC (2003). "Hypertensive emergencies. Etiology and management". American Journal of Cardiovascular Drugs: Drugs, Devices, and Other Interventions. 3 (1): 21–31. doi:10.2165/00129784-200303010-00003. PMID 14727943. S2CID 1993954.

- ^ Schurr JW, Gitman B, Belchikov Y (December 2014). "Controversial therapeutics: the β-adrenergic antagonist and cocaine-associated cardiovascular complications dilemma". Pharmacotherapy. 34 (12): 1269–1281. doi:10.1002/phar.1486. PMID 25224512. S2CID 5282953.

- ^ Freeman K, Feldman JA (February 2008). "Cocaine, myocardial infarction, and beta-blockers: time to rethink the equation?". Annals of Emergency Medicine. 51 (2): 130–134. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.08.020. PMID 17933425.

- ^ Hollander JE, Henry TD (February 2006). "Evaluation and management of the patient who has cocaine-associated chest pain". Cardiology Clinics. 24 (1): 103–114. doi:10.1016/j.ccl.2005.09.003. PMID 16326260.

- ^ Chan GM, Sharma R, Price D, Hoffman RS, Nelson LS (September 2006). "Phentolamine therapy for cocaine-association acute coronary syndrome (CAACS)". Journal of Medical Toxicology. 2 (3): 108–111. doi:10.1007/BF03161019. PMC 3550159. PMID 18072128.

- ^ Bella AJ, Brock GB (2004). "Intracavernous pharmacotherapy for erectile dysfunction". Endocrine. 23 (2–3): 149–55. doi:10.1385/ENDO:23:2-3:149. PMID 15146094. S2CID 13056029.

- ^ Rowbotham MC (June 2006). "Pharmacologic management of complex regional pain syndrome". The Clinical Journal of Pain. 22 (5): 425–9. doi:10.1097/01.ajp.0000194281.74379.01. PMID 16772796. S2CID 17837280.

- ^ Malamed S (January 2009). "What's new in local anaesthesia?". SAAD Digest. 25: 4–14. PMID 19267135.

- ^ US 2503059, Miescher K, Marxer A, Urech E, "2-(N:N-diphenyl-aminomethyl) imidazolines", issued 1950, assigned to Ciba Pharmaceuticals Products, Inc.

- ^ Urech E, Marxer A, Miescher K (1950). "2-Aminoalkylimidazoline". Helv. Chim. Acta. 33 (5): 1386–407. doi:10.1002/hlca.19500330539.

- ^ "Common Side Effects of Phentolamine Mesylate for Injection (Phentolamine Mesylate)". Drug Center - RxList.