Sabah

Sabah | |

|---|---|

| Negeri Di Bawah Bayu (Land Below The Wind) | |

| Motto(s): Sabah Maju Jaya Sabah Prosper | |

| Anthem: Sabah Tanah Airku Sabah My Homeland | |

| |

| Capital | Kota Kinabalu |

| Divisions | |

| Government | |

| • Yang di-Pertua Negeri | Juhar Mahiruddin |

| • Chief Minister | Musa Aman (BN) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 73,631 km2 (28,429 sq mi) |

| Population (2015)[2] | |

| • Total | 3,543,500 |

| • Density | 48/km2 (120/sq mi) |

| Demonym | Sabahan |

| Human Development Index | |

| • HDI (2010) | 0.643 (medium) (14th) |

| Time zone | UTC+8 (MST) |

| Postal code | 88xxx to 91xxx |

| Calling code | 087 (Inner District) 088 (Kota Kinabalu & Kudat) 089 (Lahad Datu, Sandakan & Tawau) |

| Vehicle registration | SA, SAA, SAB, SAC (Kota Kinabalu & Kota Belud) SB (Beaufort) SD (Lahad Datu) SK (Kudat) SS (Sandakan) ST (Tawau) SU (Keningau) |

| Former name | North Borneo |

| Brunei Sultanate | 15th century–1882[3] |

| Sulu Sultanate (North-eastern part) | 1658–1882 |

| British North Borneo | 1882–1941 |

| Japanese occupation | 1941–1945 |

| British Crown Colony | 1946–1963 |

| Self-government | 31 August 1963[4][5][6][7] |

| Malaysia Agreement[8] | 16 September 1963a[9] |

| Website | www |

| a Despite the fact that the Federation of Malaysia only came into existence on 16 September 1963, 31 August is celebrated as the Independence day of Malaysia. Since 2010, 16 September is recognised as Malaysia Day, a patriotic national-level public holiday to commemorate the foundation of Federation of Malaysia that joints North Borneo, Malaya, Sarawak and (previously) Singapore as states of equal partners in the federation.[10] | |

Sabah (Malay pronunciation: [saˈbah]) is Malaysia's easternmost state, one of two Malaysian states on the island of Borneo. It is also one of the founding members of the Malaysian federation alongside Sarawak, Singapore (expelled in 1965) and the Federation of Malaya. Like Sarawak, this territory has an autonomous law especially in immigration which differentiates it from the rest of the Malaysian Peninsula states. It is located on the northern portion of the island of Borneo and known as the second largest state in the country after Sarawak, which it borders on its southwest. It shares a maritime border with the Federal Territory of Labuan on the west and with the Philippines to the north and northeast. The state's only international border is with the province of North Kalimantan of Indonesia in the south. The capital of Sabah is Kota Kinabalu, formerly known as Jesselton. Sabah is often referred to as the "Land Below The Wind", a phrase used by seafarers in the past to describe lands south of the typhoon belt.

Etymology

The origin of the name Sabah is uncertain, and there are many theories that have arisen. One theory is that during the time it was part of the Bruneian Sultanate, it was referred to as Saba because of the presence of pisang saba, a type of banana, found on the coasts of the region. Due to the location of Sabah in relation to Brunei, it has been suggested that Sabah was a Bruneian Malay word meaning upstream[11] or "in a Northerly direction".[12] Another theory suggests that it came from the Malay word sabak which means a place where palm sugar is extracted. Sabah ('صباح') is also an Arabic word which means sunrise. The presence of multiple theories makes it difficult to pinpoint the true origin of the name.[13][14]

History

Early history

Earliest human migration and settlement into the region is believed to have dated back about 20,000–30,000 years ago. These early humans are believed to be Australoid or Negrito people. The next wave of human migration, believed to be Austronesian Mongoloids, occurred around 3000 BC.

Bruneian Empire and the Sulu Sultanate

During the 7th century CE, a settled community known as Vijayapura, a tributary to the Srivijaya empire, was thought to have existed in northwest Borneo.[16] Another kingdom which suspected to have existed beginning the 9th century was P'o-ni. It was believed that Po-ni existed at the mouth of Brunei River and was the predecessor to the Sultanate of Brunei.[17] The Sultanate of Brunei began after the ruler of Brunei embraced Islam. During the reign of the fifth sultan known as Bolkiah between 1485–1524, the Sultanate's thalassocracy extended over Sabah and the Sulu Archipelago, and had trading ports in Borneo and the Philippines.[18] In 1658, the Sultan of Brunei promised to cede the northern and eastern portion of Borneo to the Sultan of Sulu in compensation for the latter's help in settling a civil war in the Brunei Sultanate. It seems to never have been ceded in practice, but the Sultanate of Sulu claimed Sabah as theirs as late as 1877.[19] Many Brunei Malays migrated to this region during this period, although the migration has begun as early as the 15th century after the Brunei conquest of the territory.[20] In the same time, the seafaring Bajau-Suluk people arrived from the Sulu Archipelago and started to settling in the coasts of north and eastern Borneo. It is believed that they were fleeing from the oppression of the Spanish colonist in their region.[21] While the thalassocratic Brunei and Sulu sultanates controlled the western and eastern coasts of Sabah respectively, the interior region remained largely independent from either kingdoms.[22]

British North Borneo

Right: Sultan Jamalalulazam of Sulu signed the second concession treaty on 22 January 1878.[19]

In 1761, Alexander Dalrymple, an officer of the British East India Company, concluded an agreement with the Sultan of Sulu to allow him to set up a trading post in the Sulu area, although it proved to be a failure.[23] In 1846, the island of Labuan on the west coast of Sabah was ceded to Britain by the Sultan of Brunei, and in 1848 it became a British Crown Colony while the territory of Sabah ceded through an agreement on 1877, the territory on the eastern part were ceded by the Sultanate of Sulu in 1878.[24][25][26] Following a series of transfers, the rights to North Borneo were transferred to Alfred Dent, whom in 1881 formed the British North Borneo Company (BNBC).[27] In the following year, Kudat was made its capital. In 1883, the capital was moved to Sandakan and in 1885, the United Kingdom, Spain, and Germany signed the Madrid Protocol, which recognised the sovereignty of Spain over the Sulu Archipelago in return for the relinquishment of all Spanish claims over North Borneo.[28] North Borneo became a protectorate of the United Kingdom in 1888.

Japanese occupation and Allied liberation

As part of the Second World War, Japanese forces landed in Labuan on 1 January 1942, and continued to invade the rest of North Borneo. From 1942 to 1945, Japanese forces occupied North Borneo, along with most of the island. Bombings by the allied forces devastated most of the towns including Sandakan, which was razed to the ground. In Sandakan, there was once a brutal POW camp run by the Japanese for British and Australian POWs from North Borneo. The prisoners suffered under notoriously inhuman conditions, and Allied bombardments caused the Japanese to relocate the POW camp to inland Ranau, 260 km away. All the prisoners, then were reduced to 2,504 in number, were forced to march the infamous Sandakan Death March. Except for six Australians, all of the prisoners died. The war ended on 10 September 1945. After the surrender, North Borneo was administered by the British Military Administration and in 1946 it became a British Crown Colony. Due to massive destruction in the town of Sandakan since the war, Jesselton was chosen to replace the capital with the Crown continued to rule North Borneo until 1963.[30] Upon Philippine independence in 1946, seven of the British-controlled Turtle Islands off the northeast of Borneo were ceded to the Philippines.[31]

Self-government and the Federation of Malaysia

On 31 August 1963, North Borneo attained self-government.[4][5][7] The Cobbold Commission was set up on 1962 to determine whether the people of Sabah and Sarawak favoured the proposed union of the Federation of Malaysia, and found that the union was generally favoured by the people. Most ethnic community leaders of Sabah, namely, Tun Mustapha representing the native Muslims, Tun Fuad Stephens representing the non-Muslim natives, and Khoo Siak Chew representing the Chinese, would eventually support the union. After discussion culminating in the Malaysia Agreement and 20-point agreement, on 16 September 1963 North Borneo, as Sabah, was united with Malaya, Sarawak and Singapore, to form the independent Federation of Malaysia.[32][33][34]

From before the formation of Malaysia till 1966, Indonesia adopted a hostile policy towards the British backed Malaya, and after union to Malaysia. This undeclared war stems from what Indonesian President Sukarno perceive as an expansion of British influence in the region and his intention to wrest control over the whole of Borneo under the Indonesian republic. Tun Fuad Stephens became the first chief minister of Sabah. The first Governor (Yang di-Pertuan Negeri) was Tun Mustapha. Sabah held its first state election in 1967. A total of 12 state elections have been held, the latest in 2013. Sabah has had 14 different chief ministers and 10 different Yang di-Pertua Negeri. On 14 June 1976, the government of Sabah signed an agreement with Petronas, the federal government-owned oil and gas company, granting it the right to extract and earn revenue from petroleum found in the territorial waters of Sabah in exchange for 5% in annual revenue as royalties.[35]

The state government of Sabah ceded Labuan to the Malaysian federal government, and Labuan became a federal territory on 16 April 1984.[36] In 2000, the state capital Kota Kinabalu was granted city status, making it the 6th city in Malaysia and the first city in the state. Also in the same year, Kinabalu National Park was officially designated by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site, making it the first site in the country to be given such designation. In 2002, the International Court of Justice ruled that the islands of Ligitan and Sipadan, claimed by Indonesia, are part of Sabah and Malaysia.[37]

Geography

The western part of Sabah is generally mountainous, containing the three highest mountains in Malaysia. The most prominent range is the Crocker Range which houses several mountains of varying height from about 1,000 metres to 4,000 metres. At the height of 4,095 metres, Mount Kinabalu is the highest mountain in the Malay Archipelago (excluding New Guinea) and the 10th highest mountain in political Southeast Asia. The jungles of Sabah are classified as tropical rainforests and host a diverse array of plant and animal species. Kinabalu National Park was inscribed as a World Heritage Site in 2000 because of its richness in plant diversity combined with its unique geological, topographical, and climatic conditions.[38]

Lying nearby Mount Kinabalu is Mount Tambuyukon. With a height of 2,579 metres, it is the third highest peak in the country. Adjacent to the Crocker Range is the Trus Madi Range which houses the second highest peak in the country, Mount Trus Madi, with a height of 2,642 metres. There are lower ranges of hills extending towards the western coasts, southern plains, and the interior or central part of Sabah. These mountains and hills are traversed by an extensive network of river valleys and are in most cases covered with dense rainforest.

The central and eastern portion of Sabah are generally lower mountain ranges and plains with occasional hills. Kinabatangan River begins from the western ranges and snakes its way through the central region towards the east coast out into the Sulu Sea. It is the second longest river in Malaysia after Rajang River at a length of 560 kilometres. The forests surrounding the river valley also contains an array of wildlife habitats, and is the largest forest-covered floodplain in Malaysia.[39]

Other important wildlife regions in Sabah include Maliau Basin, Danum Valley, Tabin, Imbak Canyon and Sepilok. These places are either designated as national parks, wildlife reserves, virgin jungle reserves, or protection forest reserve.

Over three-quarters of the human population inhabit the coastal plains. Major towns and urban centres have sprouted along the coasts of Sabah. The interior region remains sparsely populated with only villages, and the occasional small towns or townships.

Beyond the coasts of Sabah lie a number of islands and coral reefs, including the largest island in Malaysia, Pulau Banggi. Other large islands include, Pulau Jambongan, Pulau Balambangan, Pulau Timbun Mata, Pulau Bumbun, and Pulau Sebatik. Other popular islands mainly for tourism are, Pulau Sipadan, Pulau Selingan, Pulau Gaya, Pulau Tiga, and Pulau Layang-Layang.

Territorial disputes

Sabah has seen several territorial disputes with Malaysia's neighbours Indonesia and the Philippines. In 2002, both Malaysia and Indonesia submitted to arbitration by the International Court of Justice on a territorial dispute over the Ligitan and Sipadan islands which were later won by Malaysia.[41] There are also several overlapping claims over the Ambalat continental shelf in the Celebes (Sulawesi) Sea. Malaysia's claim over a portion of the Spratly Islands is also based on sharing a continental shelf with Sabah.[42]

The Philippines has a territorial claim over much of the eastern part of Sabah, the former North Borneo. It claims that the territory, via the heritage of the Sultanate of Sulu, was only leased to the North Borneo Chartered Company in 1878 with the Sultanate's sovereignty never being relinquished. Malaysia however, considers this dispute as a "non-issue," as it interprets the 1878 agreement as that of cession and that it deems that the residents of Sabah had exercised their right to self-determination when they joined to form the Malaysian federation in 1963.[43][44]

Demographics

Population

Sabah’s population numbered 651,304 in 1970 and grew to 929,299 a decade later. But in the two decades following 1980, the state’s population rose significantly by a staggering 1.5 million people, reaching 2,468,246 by 2000. As of 2010[update], this number had grown further to 3,117,405, with foreigners making up 27% of the total [46] The population of Sabah is 3,117,405 as of the last census in 2010 which showed more than a 400 percent increase from the census of 1970 (from 651,304 in 1970 to 3,117,405 in 2010).[47] and is the third most populous state in Malaysia after Selangor and Johor. In 2015, the population was reported to be 3,543,500, while non-Malaysian citizens was reported to be 870,400, the highest in all Malaysian states.[2]

Sabah has one of the highest population growth rates in the country as a result of legal and purportedly state-sponsored illegal immigration and naturalisation from elsewhere in Malaysia, Indonesia and particularly from the Muslim-dominated southern provinces of the Philippines who were awarded Malay stock and granted citizenship.[48][49] As a result, the Bornean Sabahan, most of whom are non-Muslim, have become minorities in their own homeland and this problem has become the main cause of ethnic tension in Sabah.[45][50] Therefore, on 1 June 2012, Prime Minister Najib Razak of the Malaysia announced that the federal government has agreed to set up the Royal Commission of Inquiry on illegal immigrants in Sabah to investigate.[51] The report findings has stated that Project IC have existed.[52]

- Kadazan-Dusun: 17.82% (555,647)

- Bajau: 14% (436,672)

- Malay (Bruneian Malays, Kedayan, Banjar, Cocos and also include Peninsular Malays): 5.71% (178,029)

- Murut: 3.22% (100,631)

- Other bumiputra:[53] 20.56% (640,964) – which consists of Rungus, Iranun, Bisaya, Tatana, Lun Bawang/Lun Dayeh, Tindal, Tobilung, Kimaragang, Suluk, Tagal, Timogun, Nabay, Orang Sungai, Makiang, Minokok, Mangka’ak, Lobu, Bonggi, Tidong, Bugis, Ida’an (Idahan), Begahak, Kagayan, Talantang, Tinagas, Banjar, Gana, Kuijau, Tombonuo, Dumpas, Peluan, Baukan, Sino, Jawa

- Chinese (majority Hakka): 9.11% (284,049)

- Other non-bumiputra: 1.5% (47,052)

- Non-Malaysian citizens (Filipino, Indonesian): 27.81% (867,190)

Language and ethnicity

Malay language is the national language spoken across ethnicities, although Sabahan creole is different from the Standard West Malaysian dialect of Johor-Riau.[54] Sabah also has its own slang for many words in Malay, mostly originated from indigenous words, and to an extent, Indonesian and Bruneian Malay. In addition, indigenous languages such as Kadazan, Dusun, Bajau, Brunei, Murut and Suluk have their own segments on state radio broadcast as well as English.

English remains an active second language, with its use allowed for some official purposes under the National Language Act of 1967. As there are quite significant population of ethnic Chinese Sabahans, and with many Bumiputera Sabahans sending their children to Chinese vernacular schools,[55] Mandarin is also widely used in Sabah. Spanish based creole, Zamboangueño, a dialect of Chavacano, has spread into one village in Semporna from the southern Philippines.[56]

The people of Sabah are divided into 32 officially recognised ethnic groups, in which 28 are recognised as Bumiputra, or indigenous people.[6] The largest non-bumiputra ethnic group is the Chinese (13.2%). The predominant Chinese dialect group in Sabah is Hakka, followed by Cantonese and Hokkien. Most Chinese people in Sabah are concentrated in the major cities and towns, namely Kota Kinabalu, Sandakan and Tawau. The largest indigenous ethnic group is Kadazan-Dusun, followed by Bajau, and Murut. There is a much smaller proportion of Indians and other South Asians in Sabah compared to other parts of Malaysia. Collectively, all persons coming from Sabah are known as Sabahans and identify themselves as such.

Sabah demography consists of many ethnic groups, for example:

Other inhabitants:

- West Malaysian – Malay, Chinese, Indian

- Chinese Sabahan – Hakka, Cantonese, Teochew, Hainanese

- Filipino – Chavacano, Visayan, Ilocano, Badjao, Iranun, Tausug/Suluk, Tagalog

- Indonesian – Bugis, Javanese, Ambonese, Banjarese, Torajan, Chinese Indonesian

- Indian – Punjabi, Tamil

- Sarawakian – Iban, Penan, Dayak, Orang Ulu, Sarawakian Malay, Sarawakian Chinese

- Pakistani – Pashtun

- Arab people – Hadhrami

- Eurasian

- Timorese

- Japanese

- Koreans

Religion

Since independence in 1963, Sabah has undergone a significant change in its religious composition, particularly in the percentage of its population professing Islam. In 1960, the percentage of Muslims was 37.9%, Christians - 16.6%, while about one-third remained animist.[58] In 2010, the percentage of Muslims had increased to 65.4%, while people professing Christianity grew to 26.6% and Buddhism at 6.1%.

In 1973, USNO amended the Sabah Constitution to make Islam the religion of State of Sabah. USIA vigorously promote conversion of Sabahans natives to Islam by offering rewards and office position, and also through migration of Muslim immigrants from the Philippines and Indonesia. Expulsion of Christian missionaries from the state were also performed to reduce Christian proselytisation of Sabahan natives.[59] Filipino Muslims and other Muslim immigrants from Indonesia and even Pakistan were brought into the state with instruction from the USNO chief at the time Tun Mustapha and been giving identity cards in the early 1990s to help topple the PBS state government and to make him appointed as the state governor, however his plan to become the state governor were unsuccessful but many illegal immigrants has changed the demography of Sabah.[60]

These policies were continued when Sabah was under the BERJAYA's administration headed by Datuk Harris, in which he openly exhorted to Muslims of the need to have a Muslim majority, to control the Christian Kadazans (without the help of the Chinese minority).[61]

As of 2010[update] the population of Sabah follows:

- 2,096,153 Muslim

- 853,726 Christian

- 194,428 Buddhist

- 3,037 Hindu

- 2,495 Confucianism/Taoism

- 3,467 followers of other religions

- 9,850 non-religious

- 43,586 unknown religion

Meanwhile, population distribution by religion in Sabah for Malaysian citizens only are as follows:[62]-

- 1,343,210 Muslim - 58%

- 730,202 Christian - 32%

- 192,881 Buddhist - 8%

- 2,479 Hindu - 0.1%

- 2,426 Confucianism/Taoism - 0.1%

- 2,320 followers of other religions - 0.1%

- 8,559 non-religious - 0.3%

- 34,886 unknown religion - 1.4%

The huge number of non-Malaysian Muslim citizens residing in Sabah, and also based on some of the findings from Royal Commission of Inquiry on illegal immigrants in Sabah, has led to the conclusion that Sabah has gone through a systematic granting of citizenship to foreigners to ensure favourable demographic pattern to the ruling government, in an operation named Project IC.

Economy

Sabah economy relies on three key development sectors; agriculture, tourism and manufacturing. Petroleum and palm oil remained the two most exported commodities. Sabah imports mainly automobiles and machinery, petroleum products and fertilisers, food and manufactured goods.[63] In the 1970s, Sabah was ranked second behind Selangor including Kuala Lumpur as the richest state in Malaysia.[64] As of 2010[update], Sabah is the poorest state in Malaysia. GDP growth was 2.4%, the lowest in Malaysia behind Kelantan.[65] Proportion of population living below US$1 per day declined from 30% in 1990 to 20% in 2009 but still lag behind other states that have lowered poverty rate significantly from 17% in 1990 to 4% in 2009.[66] Slum is nonexistent in Malaysia but the highest number of squatter settlements is in Sabah with households between 20,000 and 40,000. After Kuala Lumpur, most low-cost public housing units under the People's Housing Program were built in Sabah. Cabotage policy imposed on Sabah and Sarawak is one of the reason behind the higher price of goods. The rules set in the early 1980s made sure that all domestic transport of foreign goods between peninsula and Sabah ports are only for Malaysian company vessels. This leads to shipping cartel charging excessive costs and ultimately a higher cost of living in East Malaysia.[67] Cabotage rules also affected the industry sector. Tan Chong Motor is planning to build a Nissan 4WD factory in KKIP but higher cost of shipping stalled the plan that could provide new jobs.[68] Lack of industry providing jobs for professional and highly skilled workers forced large numbers of Sabahans to seek opportunities in Peninsular Malaysia, Singapore, Australia and United States.

The 5% fixed oil royalty Sabah currently receives from Petronas according to Petroleum Development Act 1974 is also an issue of contention.[69] The three oil producing states namely Sabah, Sarawak and Terengganu demanded Petronas to review the agreement and increase royalty to no avail.

Agriculture

Sabah was traditionally heavily dependent on lumber based on export of tropical timber, but with increasing depletion at an alarming rate of the natural forests, ecological efforts to save the remaining natural rainforest areas were made in early 1982 through forest conservation methods by collecting seeds of different species particularly acacia mangium and planting it to pilot project areas pioneered by the Sandakan Forest Research Institute researchers. Other important agricultural activities for the Sabah economy include rubber and cocoa. The palm oil now has become the largest agricultural source for Sabah, however the activities has results on the largest deforestation which destroys the habitat of borneo pygmy elephant, proboscis monkey, orangutan and rhinoceros.[70][71][72] America's lobster breeding company Darden will start a huge investment to breed lobsters in Sabah waters for export to the United States in the coming years. Agriculture sector is supported by Department of Agriculture, Ministry of Agriculture & Food Industry and Palm Oil Industrial Cluster.

Tourism

Tourism, particularly eco-tourism, is a major contributor to the economy of Sabah. In 2006, 2,000,000 tourists visited Sabah[73] and it is estimated that the number will continue to rise following vigorous promotional activities by the state and national tourism boards and also increased stability and security in the region. Sabah currently has six national parks. One of these, the Kinabalu National Park, was designated as a World Heritage Site in 2000. It is the first[74] of two sites in Malaysia to obtain this status, the other being the Gunung Mulu National Park in Sarawak. These parks are maintained and controlled by Sabah Parks under the Parks Enactment 1984. The Sabah Wildlife Department also has conservation, utilisation, and management responsibilities.[75] Tourism sector is supported by Ministry of Tourism, Culture & Environment and Sabah Tourism Board. Sri Pelancongan Sabah, a wholly owned subsidiary of Sabah Tourism Board, organises the annual Sunset Music Fest at the Tip of Borneo, which is Sabah's largest outdoor concert. The venue is in Tanjung Simpang Mengayau, Kudat, and has been held annually since 2009, attracting both local and international acts.[76]

Manufacturing

There are hundreds of small and medium enterprises (SMEs) and industries (SMIs) in Sabah[77] and some companies have become a household name such as Gardenia. Sabah government is seriously pursuing industrialisation with the Sabah Development Corridor plan specifically in Sepanggar area where KKIP Industrial Park and Sepanggar Container Port Terminal located. Sabah manufacturing are supported by Ministry of Industrial Development and Department of Industrial Development & Research.

Urban centres and ports

There are currently 7 ports in Sabah: Kota Kinabalu Port, Sepanggar Bay Container Port, Sandakan Port, Tawau Port, Kudat Port, Kunak Port, and Lahad Datu Port. These ports are operated and maintained by Sabah Ports Authority.[78] The main city and towns are:

| Rank | City and main towns | Population (2010) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Kota Kinabalu | 628,725 |

| 2 | Sandakan | 396,290 |

| 3 | Tawau | 397,673 |

| 4 | Lahad Datu | 298,584 |

| 5 | Keningau | 200,495 |

Government

Sabah is a representative democracy with universal suffrage for all citizens above 21 years of age. However, legislation regarding state elections are within the powers of the federal government and not the state.

Executive

The Yang di-Pertua Negeri sits at the top of the hierarchy followed by the state legislative assembly and the state cabinet. The Yang di-Pertuan Negeri is officially the head of state however its functions are largely ceremonial. The chief minister is the head of government and is also the leader of the state cabinet. The legislature is based on the Westminster system and therefore the chief minister is appointed based on his or her ability to command the majority of the state assembly. A general election representatives in the state assembly must be held every five years. This is the only elected government body in the state, with local authorities being fully appointed by the state government owing to the suspension of local elections by the federal government. The assembly meets at the state capital, Kota Kinabalu.

| # | Chief Minister | Took office | Left office | Party |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tun Fuad Stephens (1st term) | 16 September 1963 | 31 December 1964 | Alliance (UNKO) |

| 2 | Peter Lo Sui Yin | 1 January 1965 | 12 May 1967 | Alliance (SCA) |

| 3 | Mustapha Harun | 12 May 1967 | 1 November 1975 | Alliance (USNO) |

| 4 | Mohamad Said Keruak | 1 November 1975 | 18 April 1976 | Barisan Nasional (USNO) |

| 5 | Tun Fuad Stephens (2nd term) | 18 April 1976 | 6 June 1976 | Barisan Nasional (BERJAYA) |

| 6 | Harris Salleh | 6 June 1976 | 22 April 1985 | Barisan Nasional (BERJAYA) |

| 7 | Joseph Pairin Kitingan | 22 April 1985 | 17 March 1994 | Parti Bersatu Sabah (1985–1986) |

| Barisan Nasional (PBS) (1986–1990) | ||||

| Parti Bersatu Sabah (1990–1994) | ||||

| 8 | Sakaran Dandai | 17 March 1994 | 27 December 1994 | Barisan Nasional (UMNO) |

| 9 | Salleh Said Keruak | 27 December 1994 | 28 May 1996 | Barisan Nasional (UMNO) |

| 10 | Yong Teck Lee | 28 May 1996 | 28 May 1998 | Barisan Nasional (SAPP) |

| 11 | Bernard Dompok | 28 May 1998 | 14 March 1999 | Barisan Nasional (UPKO) |

| 12 | Osu Sukam | 14 March 1999 | 27 March 2001 | Barisan Nasional (UMNO) |

| 13 | Chong Kah Kiat | 27 March 2001 | 27 March 2003 | Barisan Nasional (LDP) |

| 14 | Musa Aman | 27 March 2003 | present | Barisan Nasional (UMNO) |

Legislature

| Composition of Sabah State Legislative | ||

|---|---|---|

| Political party |

Legislative Assembly |

Parliament Members |

| UMNO | 32 | 13 |

| PBS | 12 | 3 |

| UPKO | 4 | 4 |

| LDP | 2 | 1 |

| MCA | 1 | 0 |

| PBRS | 1 | 1 |

| SAPP | 2 | 2 |

| DAP | 1 | 1 |

| Source: Suruhanjaya Pilihanraya | ||

Members of the state assembly are elected from 60 constituencies which are delineated by the Election Commission of Malaysia and may not necessarily result in constituencies of same voter population sizes. Sabah is also represented in the federal parliament by 25 members elected from the same number of constituencies.

The present elected state and federal government posts are held by Barisan Nasional (BN), a coalition of parties which includes United Malays National Organisation (UMNO), Sabah Progressive Party (SAPP), United Pasokmomogun Kadazandusun Murut Organisation (UPKO), Parti Bersatu Rakyat Sabah (PBRS), Parti Bersatu Sabah (PBS), Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), and Malaysian Chinese Association (MCA).[79]

Politics of Sabah

Prior to the formation of Malaysia in 1963, the then North Borneo interim government submitted a 20-point agreement to the Malayan government as conditions before Sabah would join the Federation. Subsequently, North Borneo legislative assembly agreed on the formation of Malaysia on the conditions that these state rights were safeguarded. Sabah hence entered Malaysia as an autonomous state. However, there is a prevailing view amongst Sabahan that beginning from the second tenure of BERJAYA's administration under Datuk Harris, this autonomy has been gradually eroded under the federal influence and hegemony.[80] Amongst political contention often raised by Sabahans are the cession of Labuan island to Federal government and unequal sharing and exploitation of Sabah's resources of petroleum. This has resulted in strong anti-federal sentiments and even occasional call for secession from the Federation amongst the people of Sabah.

Until the Malaysian general election, 2008, Sabah, along with the states of Kelantan and Terengganu, are the only three states in Malaysia that had ever been ruled by opposition parties not part of the ruling BN coalition. Led by Datuk Seri Joseph Pairin Kitingan, PBS formed government after winning the 1985 elections and ruled Sabah until 1994. In 1994 Sabah state election, despite PBS winning the elections, subsequent cross-overs of PBS assembly members to the BN component party resulted in BN having majority of seats and hence took over the helm of the state government.[81]

A unique feature of Sabah politics was a policy initiated by then Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad in 1994 whereby the chief minister's post is rotated among the coalition parties every 2 years regardless of the party in power at the time, thus theoretically giving an equal amount of time for each major ethnic group to rule the state. However, in practice this system was problematic as it is too short for any leader to carry-out long term plan.[82] This practice has since stopped with power now held by majority in the state assembly by the UMNO party, which also holds a majority in the national parliament.

Direct political intervention by the federal, for example, introduction and later convenient [for UMNO] abolition of the chief minister's post and earlier PBS-BERJAYA conflict in 1985, along with co-opting rival factions in East Malaysia, is sometimes seen as a political tactic by the UMNO-led federal government to control and manage the autonomous power of the Borneo states.[83] The federal government however tend to view that these actions are justifiable as the display of parochialism amongst East Malaysians is not in harmony with nation building. This complicated Federal-State relations hence become a source of major contention in Sabah politics.

Administrative districts

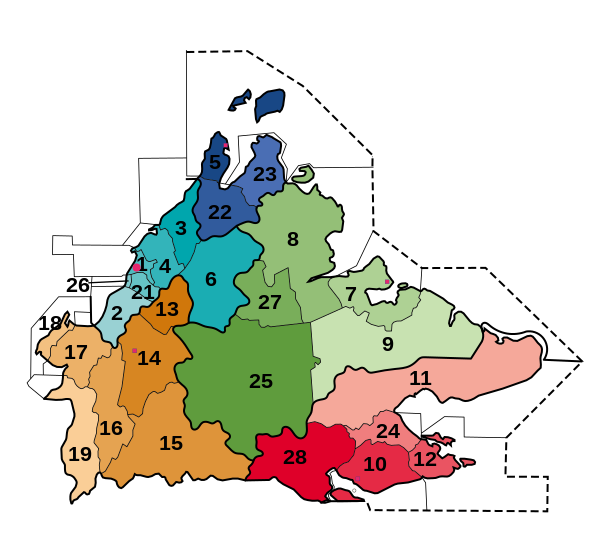

Sabah consists of five administrative divisions, which are in turn divided into 25 districts.

These administrative divisions are, for all purposes, just for reference. During the British rule until the transition period when Malaysia was formed, a Resident was appointed to govern each division and provided with a palace (Istana). This means that the British considered each of these divisions equivalent to a Malayan state. The post of the Resident was abolished in favour of district officers for each of the district.

| Division Name | Districts | Area (km²) | Population (2010)[50] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | West Coast Division | Kota Belud, Kota Kinabalu, Papar, Penampang, Putatan, Ranau, Tuaran | 7,588 | 1,067,589 |

| 2 | Interior Division | Beaufort, Nabawan, Keningau, Kuala Penyu, Sipitang, Tambunan, Tenom | 18,298 | 424,534 |

| 3 | Kudat Division | Kota Marudu, Kudat, Pitas | 4,623 | 192,457 |

| 4 | Sandakan Division | Beluran, Kinabatangan, Sandakan, Tongod | 28,205 | 702,207 |

| 5 | Tawau Division | Kunak, Lahad Datu, Semporna, Tawau | 14,905 | 819,955 |

As in the rest of Malaysia, local government comes under the purview of state governments.[84] However, ever since the suspension of local government elections in the midst of the Malayan Emergency, which was much less intense in Sabah than it was in the rest of the country, there have been no local elections. Local authorities have their officials appointed by the executive council of the state government.[85][86]

Education and culture

Universities

| Official Name in Malay | Name in English | Acronym |

|---|---|---|

| Kolej Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman | Tunku Abdul Rahman University College | TARC |

| Universiti Malaysia Sabah | Malaysia Sabah University | UMS |

| Universiti Teknologi MARA | MARA Technology University | UiTM |

| Universiti Terbuka Malaysia | Open University Malaysia | OUM |

Colleges

| Official Name in Malay | Name in English | Acronym | Website |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kolej Kinabalu | Kinabalu College | [1] | |

| Institut Seni Sabah | Sabah Institute of Art | SIA | [2] |

| Kolej Yayasan Sabah | Sabah Foundation College | KYS | [3] |

| Kolej SIDMA Sabah | SIDMA College Sabah | SIDMA | [4] |

| Kolej Pelancongan Asia Antarabangsa | Asian Tourism International College | ATIC | [5] |

| Sekolah Perniagaan AMC | Advanced Management College | AMC | [6] |

| Politeknik Kota Kinabalu | Kota Kinabalu Polytechnic | POLITEKNIK | [7] |

| Kolej Pentadbiran Dinamik Antarabangsa Sabah | Sabah International Dynamic Management College | SIDMA | [8] |

| Institut Sinaran | Sinaran Institute | SINARAN | [9] |

| Kolej Antarabangsa AlmaCrest | AlmaCrest International College | ACIC | [10] |

| Kolej Eastern | Eastern College | EASTERN | [11] |

| Institut Prima Bestari | Prima Bestari Institute | IPB | [12] |

| Kolej Informatics | Informatics College | INFORMATICS | |

| Kolej INTI | INTI College | INTI | [13] |

| Pusat Teknologi dan Pengurusan Lanjutan | Advanced Management and Technology Centre | PTPL | [14] |

| Kolej Teknologi Cosmopoint | Cosmopoint Kota Kinabalu | COSMOPOINT | [15] |

| Kolej Multimedia | Multimedia College | MMC | |

| Institut Teknologi Sabah | Sabah Institute of Technology | SIT | [16] |

| Institut Perguruan Kampus Gaya | Gaya Teachers Training Institute | IPGKG | [17] |

| Institut Perguruan Kampus Keningau | Keningau Teachers Training Institute | IPGKK | [18] |

| Institut Perguruan Kampus Tawau | Tawau Teachers Training Institute | IPGKT | [19] |

| Institut Perguruan Kampus Kent | Kent Teachers Training Institute | [20] | |

| Kolej Masterskill | Masterskill College | MASTERSKILL | [21] |

| Kolej MAHSA | MAHSA College | MAHSA | |

| Institut Latihan Perindustrian (ILP) Kota Kinabalu | Kota Kinabalu Industrial Training Institute | ILPKK | [22] |

| Institut Latihan Perindustrian (ILP) Sandakan | Sandakan Industrial Training Institute | ILPSDK | [23] |

| Kolej Sains & Kesihatan Aseana | Aseana School of Health | ASEANA | |

| Kolej Cosmopoint | Cosmopoint College | ||

| Universiti Kolej Yayasan Sabah | University College Sabah Foundation | UCSF |

Communication

Radio Televisyen Malaysia operates 2 statewide free-to-air terrestrial radio channels, Sabah FM and Sabah VFM as well as district specific channels such as Keningau FM, Sandakan FM and Tawau FM. KK FM is run by Universiti Malaysia Sabah. Bayu FM is only available through Astro satellite feed. While an independent radio station called the Kupi-Kupi FM was recently launched in 2016. KL based AMP Radio Networks and Suria FM also had set up their base to tap the emerging market. Sabahan DJs were hired and the content caters to Sabahan listeners.

Sabah's first established newspaper was the New Sabah Times. The newspaper was founded by Tun Fuad Stephens, who later became the first Chief Minister of Sabah. Today the main newspapers are the New Sabah Times, Daily Express and Borneo Post.

Movies and TV

The earliest known footage of Sabah is from two movies by Martin and Osa Johnson titled Jungle Depths of Borneo and Borneo filmed at Abai, Kinabatangan.[87] Three Came Home was a 1950 Hollywood movie based on the memoir of the same name by Agnes Newton Keith depicting the Second World War in Sandakan.

Bat*21, a 1988 Vietnam War film directed by Peter Markle, was shot at various locations in the suburbs north of Kota Kinabalu, including Menggatal, Telipok, Kayu Madang and Lapasan.

At The Fall Of Malaysian Film Industries In Early 1970s, Dedie M Borhan Founded "Sabah Film Production' And Ultimately Revive The Malaysian Film Industries As It Stands Today. First film produce by the his founded production is "Keluarga Si Comat" Starred Aziz Sattar And Ibrahim Pendek. Another memorable film is 1976 "Hapuslah Air Matamu" one of the film collaboration between Sabah Film Production and Indonesian Film Production Starred Broery Marantika and Sharifah Aini. "Azura" is the most memorable film which is the first highest grossed box-office ever in the Malaysian film history. 17 film been produced by Sabah Film Production and Dedie M Borhan retired in middle of 90s. The Malaysian film today is a legacy from the Renaissance from late 70s and 80s film industries.

Sabah's first homegrown film was Orang Kita, starring Abu Bakar Ellah. Sabah-produced TV programs such as dramas or documentaries are usually aired on TV1 while musicals aired through special Sabah slots in Muzik Aktif.

Foreign films and TV shows filmed in Sabah include the reality show Survivor: Borneo, The Amazing Race, Eco-Challenge Borneo as well as a number of Hong Kong production films such as Born Rich. Sabah was featured in Sacred Planet, a documentary hosted by Robert Redford.

Sabah was also featured in Law of the Jungle, a reality show produced by Seoul Broadcasting System(SBS) that features a cast of celebrities as they travel to primitive and natural places. Out in the wild, cast members have to survive on their own and experience life with local tribes.

Sports

Sabah FA won the Malaysia FA Cup in 1995 then become the Malaysian Premier League champion in 1996.

Matlan Marjan is a former football player for Malaysia. He scored two goals against England in an international friendly on 12 June 1991. The English team included Stuart Pearce, David Batty, David Platt, Nigel Clough, Gary Lineker, was captained by Bryan Robson and coached by Bobby Robson.[88] He again made history for Sabah when he was named the captain of the national team in the 1995 match against Brazilian football club, Flamengo XI, in which the team famously held their opponent to a 1-1 draw.[89] In 1995, he along with six other Sabah players, were arrested on suspicion of match-fixing. Although the charges were dropped, he was prevented from playing professional football and was banished to another district.[90][91] He was banished under the Restricted Residence Act.[92]

Martin Guntali was a weightlifter who won the Commonwealth Games bronze medal. Lim Keng Liat was a swimmer who won the Asian Games gold medal in 2006. Arrico Jumiti is a weightlifter who won the Asian Games gold medal at Guangzhou in 2010.

Literature

Australian author Wendy Law Suart lived in Jesselton between 1949–1953 and wrote The Lingering Eye – Recollections of North Borneo about her experiences.[93]

American author Agnes Newton Keith lived in Sandakan between 1934–1952 and wrote four books about Sabah, Land Below the Wind, Three Came Home, White Man Returns and Beloved Exiles. The second book was made into a Hollywood motion picture.

In the Earl Mac Rauch novelisation of Buckaroo Banzai (Pocket Books, 1984; repr. 2001), and in the DVD commentary, Buckaroo's archenemy Hanoi Xan is said to have his secret base in Sabah, in a "relic city of caves."

Ethnic dances

There are many types of traditional dances in Sabah, most notably:

- Sumazau: Kadazandusun traditional dance which performed during weddings and Kaamatan festival. The dance form is akin to a couple of birds flying together.

- Magunatip: Famously known as the Bamboo dance, requires highly skilled dancers to perform. Native dance of the Muruts, but can also be found in different forms and names in South East Asia.

- Daling-daling: Danced by Bajaus and Suluks. In its original form, it was a dance which combined Arabic belly dancing and the Indian dances common in this region, complete with long artificial finger nails and golden head gear accompanied by a Bajau and Suluk song called daling-daling which is a love story. Its main characteristic is the large hip and breast swings but nowadays it is danced with a faster tempo but less swings, called Igal-igal by the Bajau from Semporna District.

Notable residents

Mat Salleh was a Bajau leader who led a rebellion against British North Borneo Company administration in North Borneo. Under his leadership, the rebellion which lasted from 1894 to 1900 razed the British Administration Centre on Pulau Gaya and exercised control over Menggatal, Inanam, Ranau and Tambunan. The rebellion was by Bajaus, Dusuns and Muruts.[94]

Antanum or Antanom (full name Ontoros Antonom) (1885–1915) was a famous and influential Murut warrior who led the chiefs and villagers from Keningau, Tenom, Pensiangan and Rundum to start the Rundum uprising against the British North Borneo Company but was killed during fighting with the Company's army in Sungai Selangit, near Pensiangan.

Another notable Sabahan is Donald Stephens who helped form the state of Sabah under the UN appointed Cobbold commission. He was an initial opponent of Malaysia but later converted to the support of it.[95] He was also the first Huguan Siou or paramount leader of the Kadazan-dusun and Murut people.

Tun Datu Mustapha was a Bajau-Kagayan-Suluk Muslim political leader in Sabah through the United Sabah National Organisation (USNO) party.[96] He was a vocal supporter of Malaysia but fell out of favour with Malayan leaders despite forming UMNO branches in Sabah and deregistering USNO. Efforts to re-register USNO have not been allowed, unlike UMNO that was allowed to be re-registered under the same name.[97]

Former Chief Minister Joseph Pairin Kitingan is the current Huguan Siou and the President of Parti Bersatu Sabah (PBS). Pairin, the longest serving chief minister of the state and one of the first Kadazandusun lawyers, was known for his defiance of the federal government in the 1980s and 1990s in promoting the rights of Sabah and speaking out against the illegal immigration problems. Sabah was at the time one of only two states with opposition governments in power, the other being Kelantan. PBS has since rejoined BN and Datuk Pairin is currently the Deputy Chief Minister of Sabah.

Another former Chief Minister of Sabah is Yong Teck Lee, who held the post from 1996 to 1998. He is one of three ethnic Chinese persons to have become Chief Minister of Sabah, the others being Peter Lo Sui Yin from 1965 to 1967 and Chong Kah Kiat from 2001 to 2003. Yong is also President of the Sabah Progressive Party, a political party which seeks greater autonomy for the Sabah state government.

The 8th and current Attorney General of Malaysia, Abdul Gani Patail, comes from Sabah.

In 2006, Penampang-born Richard Malanjum was appointed Chief Judge of Sabah and Sarawak and became the first Kadazandusun to hold such a post.

Penny Wong, born in Kota Kinabalu in 1968, moved to Australia at age 5. She became the first Minister for Climate Change and Energy Efficiency and the Minister for Finance and Deregulation in Australia.[98][99] She was the first Asian-born member of the Australian cabinet.[100] She is currently the Leader of the Opposition in the Senate in Australia.[101][102]

Philip Lee Tau Sang (died 1959) was one of the most prominent Sabahan Chinese politicians in the colonial era. Of Hakka descent, he was greatly favoured by the British colonists. He was a Member of the Advisory Council of North Borneo (1947–1950), Legislative Council of North Borneo (1950–1958) and Executive Council of North Borneo (1950–1953, 1956–1957).[103] He was posthumously honoured with a road named after him in the town of Tanjung Aru, near the Kota Kinabalu International Airport.

Che'Nelle (real name Cheryline Lim) is a Sabahan-born Australian recording artist most famous for her single I Fell in Love with the DJ. She was born in Kota Kinabalu on 10 March 1983 to an ethnic Chinese father and a mother of mixed Indian and Dutch heritage. The family emigrated to Perth, Australia when she was 10 years old.

Places of interest

The Kinabalu Park is the entrance to Mount Kinabalu, standing at 1,585 metres above sea level, covering an area of 754sq km which is made up of Mount Kinabalu, Mount Tambayukon and the foothills. The park has a fascinating geological history, taking millions of years to form.[104]

Sipadan Island is Malaysia's sole oceanic island, rising 700m from the sea floor and only 12 hectares in size. Surrounded by crystal clear waters, the island is a treasure trove of some of the most amazing species such as sea eagles, kingfishers, sunbirds, starlings, wood pigeons, coconut crab, turtles, bumphead parrotfish and barracudas.[105]

The Rainforest Discovery Centre is part of the Kabili-Sepilok Forest Reserve. Enjoy spectacular views of the beautiful rainforest from 28 metres above ground on the 147- metre long canopy walkway, and catch a glimpse of wildlife such as cunning mousedeer, wily civet cats, cute tarsiers and various insects and birds, as well as flora such as 250 species of native orchids in bloom in the Plant Discovery Garden.[106]

Sepilok Orang Utan Sanctuary is as a rehabilitation centre for orangutans where one can visit and observe the primates. Aside from orang utans, over 200 species of birds and a variety of wild plants can be found within the 5.666ha. forest reserve.[107]

The Tunku Abdul Rahman Marine Park comprises a cluster of five idyllic islands, Pulau Manukan, Pulau Mamutik, Pulau Sulug, Pulau Gaya and Pulau Sapi, spread over 4,929 hectares, of which two-thirds is sea. The islands have soft white beaches that are teeming with fish and coral, and is home to a variety of exotic flora and fauna such as the intriguing Megapode or Burung Tambun, a chicken look-alike bird with large feet that makes a meowing sound like a cat.[108]

Danum Valley is blessed with a startling diversity of tropical flora and fauna such as the rare Sumatran Rhinoceros, orang utans, gibbons, mousedeer, clouded leopard and some 270 species of birds. Activities offered are jungle treks, river swimming, bird watching, night jungle tours and excursions to nearby logging sites and timber mills.[109]

Mabul Island is located in the clear waters of the Celebes Sea off the mainland of Sabah, surrounded by gentle sloping reefs two to 40m deep and home to the Pala'u (Bajau Laut) tribe. The main activity on the island is diving, with over eight popular dive spots. Marine life that can be seen in the surrounding waters include sea horses, exotic starfish, fire gobies, crocodile fish, pipefish and snake eels.[110]

Conservation

Other reserves or protected areas include;

- Tabin Wildlife Reserve – Stronghold for rare large mammals like Bornean elephant, Sumatran rhinoceros, Bornean banteng and Bornean clouded leopard

- Turtle Islands Park – Conservation efforts for endangered sea turtles

- Pulau Tiga Park

- Crocker Range Park

- Tawau Hills Park

See also

References

- ^ "Preliminary Count Report". Department of Statistics, Malaysia. 2010. Archived from the original on 27 December 2010. Retrieved 24 January 2011.

- ^ a b "Population by States and Ethnic Group". Department of Information, Ministry of Communications and Multimedia, Malaysia. 2015. Archived from the original on 12 February 2015. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 12 February 2016 suggested (help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Rozan Yunos (21 September 2008). "How Brunei lost its northern province". The Brunei Times. Archived from the original on 17 June 2014. Retrieved 28 October 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "The National Archives DO 169/254 (Constitutional issues in respect of North Borneo and Sarawak on joining the federation)". The National Archives. 1961–1963. Retrieved 23 April 2015.

- ^ a b Philip Mathews (28 February 2014). Chronicle of Malaysia: Fifty Years of Headline News, 1963-2013. Editions Didier Millet. pp. 15–. ISBN 978-967-10617-4-9.

- ^ a b Oxford Business Group. The Report: Sabah 2011. Oxford Business Group. pp. 13–. ISBN 978-1-907065-36-1. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ a b Frans Welman. Borneo Trilogy Volume 1: Sabah. Booksmango. pp. 159–. ISBN 978-616-245-078-5. Retrieved 28 May 2013.

- ^ "Malaysia Act 1963 (Chapter 35)" (PDF). The National Archives. United Kingdom legislation. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 November 2012. Retrieved 12 August 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Agreement relating to Malaysia between United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, Federation of Malaya, North Borneo, Sarawak and Singapore

- ^ Yeng, Ai Chun (19 October 2009). "Malaysia Day now a public holiday, says PM". Archived from the original on 13 February 2015. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- ^ Allen R. Maxwell (1981–1982). "The Origin of the name 'Sabah'". Sabah Society Journal. Vol. VII (No. 2)Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ W. H. Treacher (1891). "British Borneo: Sketches of Brunai, Sarawak, Labuan, and North Borneo". The Project Gutenberg eBook: 95. Retrieved 15 October 2009Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ Jaswinder Kaur (16 September 2008). "Getting to root of the name Sabah". New Straits Times – via HighBeam (subscription required) . Retrieved 25 February 2016.

- ^ Danny Wong Tze Ken (2015). "The Name of Sabah and the Sustaining of a New Identity in a New Nation" (PDF). University of Malaya Repository. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 February 2016. Retrieved 25 February 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Why 'Sultan' is dreaming". Daily Express. 27 March 2013. Archived from the original on 10 June 2015. Retrieved 28 March 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Wendy Hutton (November 2000). Adventure Guides: East Malaysia. Tuttle Publishing. pp. 31–. ISBN 978-962-593-180-7. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- ^ Barbara Watson Andaya; Leonard Y. Andaya (15 September 1984). A History of Malaysia. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 57–. ISBN 978-0-312-38121-9. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- ^ Graham Saunders (2002). A history of Brunei. Routledge. pp. 40–. ISBN 978-0-7007-1698-2. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- ^ a b Rozan Yunos (7 March 2013). "Sabah and the Sulu claims". The Brunei Times. Archived from the original on 17 June 2014. Retrieved 20 September 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Rozan Yunos (24 October 2011). "In search of Brunei Malays outside Brunei". The Brunei Times. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- ^ Mencari Indonesia: demografi-politik pasca-Soeharto (in Indonesian). Yayasan Obor Indonesia. 2007. pp. 123–. ISBN 978-979-799-083-1.

- ^ Ranjit Singh (2000). The Making of Sabah, 1865-1941: The Dynamics of Indigenous Society. University of Malaya Press. ISBN 978-983-100-095-3.

- ^ Howard T. Fry (1970). Alexander Dalrymple (1737-1808) and the Expansion of British Trade. Routledge. pp. 68–. ISBN 978-0-7146-2594-2. Retrieved 25 May 2013.

- ^ Charles ALfred Fisher (1966). South-East Asia: A Social, Economic and Political Geography. Taylor & Francis. pp. 147–. GGKEY:NTL3Y9S0ACC. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- ^ Ooi Keat Gin (2004). Southeast Asia: A Historical Encyclopedia, from Angkor Wat to Timor. R-Z. volume three. ABC-CLIO. pp. 251–. ISBN 978-1-57607-770-2. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- ^ Keat Gin Ooi (1 January 2004). Southeast Asia: A Historical Encyclopedia, from Angkor Wat to East Timor. ABC-CLIO. pp. 265–. ISBN 978-1-57607-770-2.

- ^ J. M. Gullick (1967). Malaysia and Its Neighbours, The World studies series. Taylor & Francis. pp. 148–149. ISBN 9780710041418. Retrieved 17 November 2012.

- ^ British Government (1885). "British North Borneo Treaties. (British North Borneo, 1885)" (PDF). Sabah State Government (State Attorney-General's Chambers). Retrieved 24 February 2013.

- ^ "Daily life (Info of the Sandakan Memorial Park)". Government of Australia. Department of Veterans' Affairs. 15 April 2011. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- ^ Ismail Ali. "The Role and Contribution of the British Administration and the Capitalist in the North Borneo Fishing Industry, 1945–63" (PDF). Pascasarjana Unipa Surabaya. pp. 1–3. Retrieved 22 April 2015.

The Crown Colony administration chose Jesselton, now known as Kota Kinabalu, as its new centre of administration and the new capital. This decision was made owing to the devastating damage suffered by Sandakan as mentioned previously and the ever growing development of the rubber industry along the Western residential coast of North Borneo. Although Sandakan is no longer the capital city, it remained as the "economic capital of the state" for North Borneo, specifically as a port which handles activities pertaining to the export of timber and other agricultural products from the eastern coast of North Borneo. While, the fishing industry at the final stages of the British administration era saw a great involvement by the Hong Kong "towkays" to the prawn commodity around the coasts of Kudat, Sandakan and up Tambisan. For example, in 1951 the British administration granted an Hong Kong-based Chun-Li Company to operate prawn industry in the North Borneo waters.

- ^ Peter C. Richards (6 December 1947). "New Flag Over Pacific Paradise". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 22 October 2015.

- ^ "UNITED NATIONS MEMBER STATES". Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- ^ "Sabah's Heritage: A Brief Introduction to Sabah's History", Muzium Sabah, Kota Kinabalu. 1992

- ^ Ramlah binti Adam, Abdul Hakim bin Samuri, Muslimin bin Fadzil: "Sejarah Tingkatan 3, Buku teks", published by Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka (2005)

- ^ "More revenue from oil". Daily Express. 19 June 2004. Retrieved 19 September 2009.

- ^ "Laws of Malaysia A585 Constitution (Amendment) (No.2) Act 1984". Government of Malaysia. Department of Veterinary Services. Retrieved 28 April 2014.

- ^ Summaries of Judgments, Advisory Opinions and Orders of the International Court of Justice: 1997-2002. United Nations Publications. 2003. pp. 263–. ISBN 978-92-1-133541-5. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- ^ Kinabalu Park – Justification for inscription, UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Accessed 24 June 2007.

- ^ About the Kinabatangan area, WWF. Accessed 4 August 2007.

- ^ Mohamad, Kadir (2009). "Malaysia's territorial disputes – two cases at the ICJ : Batu Puteh, Middle Rocks and South Ledge (Malaysia/Singapore), Ligitan and Sipadan [and the Sabah claim] (Malaysia/Indonesia/Philippines)" (PDF). Institute of Diplomacy and Foreign Relations (IDFR) Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Malaysia: 46. Retrieved 16 May 2014.

Map of British North Borneo, highlighting in yellow colour the area covered by the Philippine claim, presented to the Court by the Philippines during the Oral Hearings at the ICJ on 25 June 2001

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "The Court finds that sovereignty over the islands of Ligitan and Sipadan belongs to Malaysia". International Court of Justice. 17 December 2002. Archived from the original on 9 April 2014. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Chandran Jeshurun (1993). China, India, Japan, and the Security of Southeast Asia. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. pp. 196–. ISBN 978-981-3016-61-3.

- ^ Ruben Sario; Julie S. Alipala; Ed General (17 September 2008). "Sulu sultan's 'heirs' drop Sabah claim". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on 3 July 2013. Retrieved 26 October 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Jerome Aning (22 April 2009). "Sabah legislature refuses to tackle RP claim". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on 3 July 2013. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Sadiq, Kamal (2005). "When States Prefer Non-Citizens Over Citizens: Conflict Over Illegal Immigration into Malaysia" (PDF). International Studies Quarterly. 49: 101–122. doi:10.1111/j.0020-8833.2005.00336.x. Retrieved 23 April 2008.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Mahathir rejects Sabah RCI plan". Free Malaysia Today. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- ^ "Total population by ethnic group, administrative district and state, Malaysia" (PDF). Department of Statistics, Malaysia. 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 February 2016. Retrieved 25 February 2016.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 27 February 2012 suggested (help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "SPECIAL REPORT: Sabah's Project M" (fee required). Malaysiakini. 27 June 2006. Retrieved 23 April 2008. - where "M" stood for Mahathir Mohamad

- ^ Mutalib M.D. "IC Projek Agenda Tersembunyi Mahathir?" (2006)

- ^ a b c d "Population Distribution and Basic Demographic Characteristics" (PDF). Department of Statistics, Malaysia. 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 October 2012. Retrieved 19 April 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Najib announces setting up of RCI to probe issue of illegal immigrants in Sabah". Borneo Post Online. 2 June 2012. Retrieved 12 August 2012.

- ^ "Corrupt officials, syndicates behind Sabah's Project IC, no names revealed". The Malaysian Insider. 3 December 2014. Retrieved 4 December 2014.

- ^ a b Bumiputra in Sabah mean if one of the parents is a Muslim Malay or indigenous native of Sabah as stated in Article 160A (6)(a) Constitution of Malaysia; thus his child is considered as a Bumiputra

- ^ "Language And Social Context". Streetdirectory.com. 13 May 1969. Retrieved 14 November 2012.

- ^ "55,975 bumiputera pupils in Chinese schools". Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- ^ Susanne Michaelis (2008). Roots of Creole Structures: Weighing the Contribution of Substrates and Superstrates. John Benjamins Publishing. ISBN 90-272-5255-6.

- ^ Languages of Malaysia (Sabah). Ethnologue. Retrieved on 4 May 2007

- ^ a b Caldarola, Carlo (ed.) (1982). Religion and Societies: Asia and the Middle East. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-082353-0.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - ^ Regina Lim (2008). Federal-State Relations in Sabah, Malaysia: The Berjaya Administration, 1976-85. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. pp. 48–. ISBN 978-981-230-812-2. Retrieved 14 December 2012.

- ^ "'I processed thousands of ICs for Sabah illegals'". Malaysiakini. 28 February 2013. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- ^ "Asean Forecast Vol 5 No. 8: August 1985: Sabah - A New Story Elections And Its Aftermath" (PDF). Asiandialogue.com. Retrieved 14 November 2012.

- ^ "Census Atlas". Department of Statistics, Malaysia. 8 August 2015. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- ^ SABAH SELECTED FACTS AND FIGURES, Institute for Development Studies

- ^ "Outline Perspective of Sabah", Institute for Development Studies (Sabah). URL accessed 7 May 2006

- ^ "Gross Domestic Product (GDP) by State, 2010 (Updated: 17/10/2011)". Statistics.gov.my. 17 October 2011. Retrieved 14 November 2012.

- ^ "Malaysia: The Millennium Development Goals at 2010" (PDF). Undp.org.my. Retrieved 14 November 2012.

- ^ Mat, Nordin (26 July 2010). "No hidden agenda, says Masa". Btimes.com.my. Retrieved 14 November 2012.

- ^ "Sabah: Of cars and cabotage | Industry | Sabah". Oxford Business Group. Retrieved 14 November 2012.

- ^ "Sabah: Year in Review 2011 | Economy | Sabah". Oxford Business Group. Retrieved 14 November 2012.

- ^ Queville To (30 January 2013). "Sabah authorities stunned by dead elephants". Free Malaysia Today. Retrieved 31 May 2014.

- ^ John Grafila (6 March 2014). "Nasenaffen verlieren Lebensraum" (in German). Frankfurter Rundschau. Retrieved 31 May 2014.

- ^ "Das Sabah Nashorn - Forschung für den Artenschutz (DER EINSATZ FÜR DAS SABAH-NASHORN ZEIGT BEISPIELHAFT, WIE WIR DIE BIODIVERSITÄT UNSERER ERDE SCHÜTZEN KÖNNEN UND MÜSSEN)" (in German). Federal Ministry of Education Research, Germany. Retrieved 31 May 2014.

- ^ Sabah: Visitors Arrival by Nationality 2006, Sabah Tourism Board. Accessed 4 August 2007.

- ^ "Kinabalu Park". Retrieved 11 August 2009.

- ^ "About Sabah Wildlife Department". Retrieved 12 November 2007.

- ^ "Sunset Music Fest on the Tip of Borneo". TTGmice. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

- ^ "Federation of Sabah Manufacturers (FSM)". Fsm.my. 11 September 1984. Retrieved 14 November 2012.

- ^ Sabah Ports Authority

- ^ Senarai ahli Dewan Undangan Negeri Sabah, sabah.gov.my. Accessed 4 October 2008.

- ^ Regina Lim (2008). Federal-state Relations in Sabah, Malaysia: The Berjaya Administration, 1976-85. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. pp. 68–. ISBN 978-981-230-812-2. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- ^ Boon Kheng Cheah (2002). Malaysia: the making of a nation. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. pp. 63–. ISBN 978-981-230-175-8. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- ^ Daljit Singh; Kin Wah Chin; Institute of Southeast Asian Studies (2004). Southeast Asian Affairs. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. pp. 157–. ISBN 978-981-230-238-0. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- ^ Frederik Holst (23 April 2012). Ethnicization and Identity Construction in Malaysia. CRC Press. pp. 48–. ISBN 978-1-136-33059-9. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- ^ Oxford Business Group. The Report: Sabah 2011. Oxford Business Group. pp. 15–. ISBN 978-1-907065-36-1. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ Agreement concerning certain overseas officers serving in Sabah and Sarawak (1965)

- ^ RELATING TO PENSIONS AND COMPENSATION FOR OFFICERS DESIGNATED BY THE GOVERNMENT OF THE UNITED KINGDOM IN THE SERVICE OF THE STATE GOVERNMENT OF SABAH OR OF SARAWAK (1973)

- ^ "exhibition_details.htm". Safarimuseum.com. Retrieved 14 November 2012.

- ^ EnglandFC Match Data

- ^ Raymer, Robert (November 2011). "The Magic Rise and Tragic Fall of Matlan Marjan". Esquire Malaysia. Nov 2011 (The Against All Odds Issue): 127–130Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ "No charges against Sabah six". Bernama. 14 July 1995.

- ^ "Four Sabah soccer players banished to remote area". Bernama. 4 October 1995.

- ^

"Malaysian Business, Issues 1-6". University of California: New Straits Times Press (Malaysia). 1996. Retrieved 15 November 2012Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ "Dingo Media The Lingering Eye". Dingomedia.co.uk. Retrieved 14 November 2012.

- ^ C.Buckley: A School History of Sabah, London, Macmillan & Co. Ltd., 1968

- ^

Robert Oliver Tilman (1976). "In Quest of Unity: The Centralization Theme in Malaysian Federal-State Relations, 1957-75". Issue 39 of Occasional paper. Institute of Southeast Asia: 46. Retrieved 17 November 2012Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite journal}}:|volume=has extra text (help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help)CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ Johan M. Padasian: Sabah History in pictures (1881–1981), Sabah State Government, 1981

- ^ "M.G.G. Pillai". URL last accessed on 13 January 2008

- ^ White, Cassie (11 September 2010). "Gillard unveils major frontbench shake-up". ABC News. Australia. Retrieved 30 September 2010.

- ^ Gillard, Julia MP (11 September 2010). "Prime Minister announces new Ministry" (Press release). Retrieved 12 September 2010.

- ^ Panellist: Penny Wong | Q&A | ABC TV. Abc.net.au. Retrieved on 12 April 2014.

- ^ Penny Wong - Australian Labor Party. Alp.org.au. Retrieved on 12 April 2014.

- ^ Tanya Plibersek elected deputy Labor leader, Penny Wong re-elected to lead Labor in Senate - ABC News (Australian Broadcasting Corporation). Abc.net.au (14 October 2013). Retrieved on 12 April 2014.

- ^ Tet Loi, Chong (2002), 'The Hakkas of Sabah: A Survey on Their Impact on the Modernization of the Bornean Malaysian State', Sabah Theological Seminary, pg. 237-pg.241, ISBN 983-40840-0-5

- ^ "Kinabalu Park". Tourism Malaysia. Retrieved 23 May 2014.

- ^ "Sipadan Island". Tourism Malaysia. Retrieved 23 May 2014.

- ^ "Rainforest Discovery Centre". Tourism Malaysia. Retrieved 23 May 2014.

- ^ "Sepilok Orang Utan Sanctuary". Tourism Malaysia. Retrieved 23 May 2014.

- ^ "Tunku Abdul Rahman Marine Park". Tourism Malaysia. Retrieved 23 May 2014.

- ^ "Danum Valley". Tourism Malaysia. Retrieved 23 May 2014.

- ^ "Mabul Island". Tourism Malaysia. Retrieved 23 May 2014.

- Notes

- ^

Logging during the British period.

Further reading

- James Chin, (2014) Federal-East Malaysia Relations: Primus-Inter-Pares?, in Andrew Harding and James Chin (2014) 50 Years of Malaysia: Federalism Revisited (Singapore: Marshall Cavendish) pp. 152–185

- Urmenyhazi, Attila - DISCOVERING NORTH BORNEO a short travelogue on Sarawak & Sabah by the author (2007). National Library of Australia, Canberra, record ID: 4272798. Call Number: NLp 915 953 U77.