Stefan the First-Crowned

This article includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. (February 2015) |

| Stefan the First-Crowned | |

|---|---|

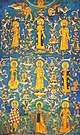

Fresco from Mileševa, dated before 1228 | |

| Grand Prince/King of Serbia | |

| Reign | 1196–1228 |

| Coronation | 1217 (as king) |

| Predecessor | Stefan Nemanja |

| Successor | Stefan Radoslav |

| Born | around 1165 |

| Died | 24 September 1228 |

| Burial | |

| Spouse | Eudokia Angelina Anna Dandolo |

| Issue | Stefan Radoslav Stefan Vladislav Stefan Uroš I Sava II |

| House | Nemanjić dynasty |

| Father | Stefan Nemanja |

| Mother | Anastasija |

| Religion | Serbian Orthodox |

Stefan Nemanjić (Serbian: Стефан Немањић, pronounced [stêfaːn němaɲitɕ]) or Stefan the First-Crowned (Стефан Првовенчани/Stefan Prvovenčani, IPA: [stêfaːn prʋoʋěntʃaːniː]; around 1165 – 24 September 1228) was Grand Prince of Serbia from 1196, and the King of Serbia from 1217 until his death in 1228. He was the first Rascian king, and through his promotion of the Serbian Grand Principality into a kingdom and helping his brother Saint Sava in establishing the Serbian Church, he is regarded one of the most important of the long lasting Nemanjić dynasty.

Stefan's literary opus is modest but of high quality. He wrote The Life of Stefan Nemanja a biography of his father.

Early life

Stefan Nemanjić was the second eldest son of Grand Prince Stefan Nemanja and Anastasija. His older brother and heir apparent, Vukan, ruled over Zeta and the neighbouring provinces (the highest appanage) while his younger brother Rastko (later known as Saint Sava) ruled over Hum.

The Byzantines attacked Serbia in 1191, raiding the banks of South Morava. Nemanja had a tactical advantage, and began to raid the Byzantine armies. Isaac II Angelus summoned a peace treaty, and the marriage of Nemanja's son Stefan to Eudokia Angelina, the niece of Isaac II, was confirmed. Stefan Nemanjić received the title of sebastokrator.

Heir apparent conflict

In an inscription dated 1195 in the church of St. Luke in Kotor, Vukan is titled as King of Duklja, Dalmatia, Travunia, Toplica and Hvosno.[1]

Although Vukan was Nemanja's eldest son, Nemanja preferred to see Stefan II on the Serbian throne mostly because Stefan was married to Byzantine princess Eudokia. It seems that Vukan reacted on this change in succession by declaring himself King of Duklja. Although he assumed a "sovereign" royal title, Vukan remained under his father's authority. On 25 March 1196, Stefan Nemanja summoned a Council in Ras, where he officially abdicated in favour of his second son, Stefan, to whom he bequeathed all his earthly possessions. This decision was not in accordance with the traditional right of primogeniture, according to which Vukan should inherited the throne. This was not accepted lightly by Vukan. Nemanja took monastic vows in the Church of Saints Peter and Paul and adopted the monastic name of Simeon. Simeon subsequently retired to his Studenica monastery and Anastasia retired to the Monastery of the Mother of Christ in Kuršumlija. After numerous pleas by Sava (originally Rastko), Simeon left to the Mount Athos, and joined Sava in 1197 in the Vatopedi monastery. In 1199, the two together rebuilt the ruined Eastern Orthodox Monastery of Hilandar given to the Serbian people by the Byzantine Emperor, which became the heart of Serbian spiritual culture. Simeon died on 13 February 1199.

While Nemanja was alive Vukan didn't oppose Stefan's rule but as soon as Nemanja died, he started to plot against him in order to become Grand Prince. He found aid in Hungarian king Emeric (1196–1204) who at the time fought against the Second Bulgarian Empire and wanted assistance. With the help of Hungarian troops in 1202, Vukan managed to overthrow Stefan, who fled into Bulgaria. Vukan was left to rule Serbia.[1] In an inscription dating to 1202–1203, Vukan is titled as "Grand Župan Vukan, Ruler of all Serbian land, Zeta, maritime towns and land of Nišava".[2]

In return for Hungarian help, Vukan became a Hungarian vassal and promised that he would convert to Catholicism if the Pope would give him the title of King. However, as a Hungarian vassal, Vukan soon got involved in the conflict with Bulgaria. In 1203 the Bulgarian army attacked Vukan, annexing Niš. In the chaos that followed, and using Vukans's sympaties for Catholicism against him, Stefan managed to return to Serbia and overthrow Vukan in 1204 becoming ruler again. Vukan was pushed into his holdings of Zeta.

In the meantime, Bishop Sava (the youngest brother), had success on Mount Athos, founding the cradle of Serbian Christianity. Sava returned to Serbia in the winter of 1205–06 or 1206–07,[3] and intervened and reconciled his two brothers, taking the remains of his father with him, which he relocated to the Studenica monastery. Stefan II asked him to remain in Serbia with his clergy, which he did, starting a widespread pastoral and educational duty to the people of Serbia. He and Sava founded several churches and monasteries, among them the Žiča monastery.[4]

Vukan continues to rule as titular King in Zeta, and abdicated in ca 1208, when his son Đorđe is mentioned as titular King of Zeta, although in edicts from Studenica dated 1209, he is mentioned only as Great Prince.[5] Vukan seems to have died in 1209 or shortly thereafter.[6]

Later rule

After the death of Kaloyan, there was a succession war in Bulgaria. Tsar Boril, the most ambitious of the nobles, took the throne and exiled Alexius Slav, Ivan Asen II and Strez (of the Asen family). Strez, the first cousin or brother of Boril, took refuge in Serbia, and was warmly welcomed at the court of Stefan II.[7][8] Even though Boril requested the extradition of Strez to Bulgaria with gifts and bribes, Stefan II refused.[7] Kaloyan had conquered Belgrade, Braničevo, Niš and Prizren, all of which were claimed by Serbia.[7] At the same time, Boril was unable to take military action against Strez and his Serbian patron, as he had suffered a major defeat at the hands of the Latins at Plovdiv.[8][9][10] Stefan went as far as to become a blood brother with Strez, in order to assure him of his continued favor.[7]

Andrija Mirosavljević was entitled the governance of Hum, as the heir of Miroslav of Hum, the uncle of Stefan II, but the Hum nobles chose his brother Petar as Prince of Hum.[11] Petar exiled Andrija and Miroslav's widow (the sister of Ban Kulin of Bosnia), Andrija fled to Rascia, to the court of Stefan II.[11] In the meantime, Petar fought successfully with neighbouring Bosnia and Croatia.[11] Stefan II sided with Andrija and went to war and secured Hum and Popovo field for Andrija sometime after his accession.[11] Petar was defeated and crossed the Neretva, continuing to rule the west and north of the Neretva, which had in 1203 been briefly occupied by Andrew II of Hungary.[11] Stefan II gave the titular and supreme rule of Hum to his son Radoslav, Andrija held the district of Popovo with the coastal lands of Hum, including Ston.[11] By agreement, when Radoslav died, the lands were bound to Andrija.[11]

Đorđe of Zeta, in order to secure his lands from Stefan, accepted Venetian suzerainty, possibly in 1208.[6] Đorđe may have done this due to tensions between the two, although this must not be the case.[6] Venice, after the Fourth Crusade, tried to exert control of the Dalmatian ports, and managed in 1205 to submit Ragusa – Đorđe submitted to prevent that Venice claimed his ports of southern Dalmatia.[6]

Đorđe promised Venice military aid in case of a revolt by another theoretical Venetian vassal, Dimitri, an Albanian Lord of Kruja.[6] This was likely related to the Rascia-Zeta conflict.[6] Stefan II married off his daughter,[6] Komnena, to Dimitri in 1208.[12] The marriage resulted in close ties and an alliance between Stefan and Dimitri amidst these conflicts.[6][12] Kruja is conquered by Epirote Despot Michael I Komnenos Doukas, and Dimitri is not heard of in any surviving sources.[12][13] After Dimitri's death, the lands are left to Komnena,[14] who soon married Greek-Albanian Gregorios Kamonas, who took power of Kruja,[15] strengthening relations with Serbia, which had after a Serbian assault on Scutari been weakened.[12][15] Đorđe disappears from sources, and Stefan II controls Zeta by 1216, probably through military action.[6] Stefan either put Zeta under his personal rule, or assigned it to his son Stefan Radoslav.[6] Zeta would from now on have no special status, and would be given to the heir apparent.[6]

Despot Michael I of Epirus conquered Skadar, and tried to press beyond, but was stopped by the Serbs and his murder by one of his servants in 1214 or 1215.[13] He was succeeded by his half-brother Theodore Komnenos Doukas.[13] Theodore took on a policy of aggressive expansion, and allied himself with Stefan II. Stefan Radoslav married Anna Doukaina Angelina, the daughter of Theodore.

Coronation and Autocephaly

Sava brings the regal crown from Rome, crowning his older brother "King of All Serbia" in the Žiča monastery in 1217, during the rule of Pope Honorius III, owing to skillful diplomacy.[16]

Sava returns to the Holy Mountain in 1217/18, marking the beginning of the real formation of the Serbian Church. He is consecrated in 1219 as the first Archbishop of the Serbian church, given autocephaly by Patriarch Manuel I of Constantinople, who was then in exile at Nicaea. In the same year Sava published Zakonopravilo (St. Sava's Nomocanon). Thus the Serbs acquired both forms of independence: political and religious.[4]

In 1219, Sava published the first constitution in Serbia – St. Sava's Nomocanon (Zakonopravilo in Serbian).[17][18] It was a compilation of civil law based on Roman law,[19][20] and canon law based on Ecumenical Councils. Its purpose was to establish a codified legal system in the young Serbian Kingdom, and to regulate the government of the Serbian Church.

Sava stays in Serbia, and continues his education of faith to the Serbian people, later he calls for a council outlawing the heretical Bogomils.[4] Sava appoints protobishops, sending them over all of Serbia to baptize the unbaptized, marry the unmarried etc. To maintain his duty as the religious and social leader, he continued to travel among the monasteries and lands to educate the people.[4]

Marriage, monastic vows and death

Stefan was married, around 1186, to Eudokia Angelina, the youngest daughter of Alexius Angelus and Euphrosyne Doukaina Kamaterina. Eudokia was the niece of the current Byzantine Emperor Isaac II Angelus. Isaac II arranged the marriage. According to the Greek historian Nicetas Choniates, Stefan and Eudocia quarrelled and separated, accusing one another of adultery, after June 1198. They had three sons and two daughters:

- King Stefan Radoslav, ruled 1228–1233

- King Stefan Vladislav I, ruled 1233–1243

- Archbishop Sava II (born Predislav, proclaimed Saint)

- Countess Komnena Nemanjić of Kruja

Stefan remarried in 1207/1208, his second wife was Anna Dandolo, granddaughter of Venetian doge Enrico Dandolo. They had one son and one daughter:

- King Stefan Uroš I, ruled 1243–1276

He built many fortresses including Maglič. At the end of his life Stefan took the monastic vow under the name Symeon, and died soon after. He was canonised as his father was.

Legacy

According to the legend there was a guest house on the road between Budva and Petrovac and a column in front of it with a wine vessel for thirsty passengers. According to this legend Stefan drank from this wine vessel during his visit to his cousin, Venetian Doge Dandolo.[21] Later, in 1223 or 1226, he allegedly built the Church of the Assumption of Mary (Serbian: Црква Успења Пресвете Богородице), thereby founding the Reževići Monastery.

See also

References

- ^ a b Ćirković 2004, p. 38

- ^ Konstantin Jirecek, Geschichte der Serben 1, Gotha 1911,p.289

- ^ Fine 1994, p. 79

- ^ a b c d Đuro Šurmin (1808). Povjest književnosti hrvatske i srpske. Tisak i naklada knjižare L. Hartmana, Kugli i Deutsch. pp. 229–.

- ^ Fine 1994, p. 49

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Fine 1994, p. 50

- ^ a b c d Fine 1994, p. 94

- ^ a b Curta, p. 385

- ^ Velimirović, p. 61

- ^ Андреев 2004, p. 180

- ^ a b c d e f g Fine 1994, p. 53

- ^ a b c d Rosamond McKitterick; David Abulafia (21 October 1999). The New Cambridge Medieval History: Volume 5, C.1198-c.1300. Cambridge University Press. p. 786. ISBN 978-0-521-36289-4.

- ^ a b c Fine 1994, p. 68

- ^ The despotate of Epiros, p. 48

- ^ a b The despotate of Epiros, p. 156

- ^ Silvio Ferrari, W. Cole Durham, Elizabeth A. Sewell, Law and religion in post-communist Europe, 2003, p. 295. ISBN 978-90-429-1262-5

- ^ Petarzoric (PDF), Alan Watson.

- ^ p. 118

- ^ Constitution.org

- ^ Web.upmf-grenoble.fr

- ^ Draško Šćekić (1987). Putujući Crnom Gorom. NIO "UR". p. 40. Retrieved 31 July 2013.

I ovdje nas čeka predanje. Ono kaže da je tu u doba Nemanjića postojala gostionica, ispred koje...

Sources

- Fajfrić, Željko (2000) [1998], Sveta loza Stefana Nemanje, Belgrade: Tehnologije, izdavastvo, agencija Janus

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Fine, John Van Antwerp (1994), The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest, University of Michigan Press, ISBN 978-0-472-08260-5

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

External links

- Use dmy dates from August 2013

- 13th-century Serbian monarchs

- 12th-century Serbian monarchs

- Medieval Serbian writers

- Orthodox monarchs

- Medieval Serbian Orthodox clergy

- 1228 deaths

- 13th-century writers

- Sebastokrators

- Ktetors

- Founders of Christian monasteries

- Nemanjić dynasty

- Burials at Serbian Orthodox monasteries