Latin: Difference between revisions

No edit summary Tag: Reverted |

ClueBot NG (talk | contribs) m Reverting possible vandalism by 62.172.127.69 to version by KLITE789. Report False Positive? Thanks, ClueBot NG. (4276600) (Bot) Tags: Rollback Disambiguation links added |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description| |

{{Short description|Indo-European language of the Italic branch}} |

||

{{other uses}} |

|||

{{more citations needed|date=February 2016}} |

|||

{{Distinguish|Ladin (disambiguation){{!}}Ladin}} |

|||

{{Infobox sport |

|||

{{pp-move}} |

|||

| image = MtnBiking SedonaMag.jpg |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=September 2022}} |

|||

| imagesize = 250px |

|||

{{Infobox language |

|||

| caption = Mountain biker riding in the [[Arizona]] desert |

|||

| states = {{ublist|[[Latium]]|[[Ancient Rome]]}} |

|||

| union = [[Union Cycliste Internationale|UCI]] |

|||

| ethnicity = {{ublist|[[Latins (Italic tribe)|Latins]]|[[Roman people|Romans]]}} |

|||

| nickname = |

|||

| era = 7th century BC <!-- [[Praeneste fibula]] --> {{endash}} 18th century AD <!-- seems to be around when regular people stopped using Latin-the-language, as opposed to Latin-as-a-source-for-names-for-things --> |

|||

| first = Open to debate. Modern era began in the late 1970s |

|||

| familycolor = Indo-European |

|||

| registered = |

|||

| |

| fam2 = [[Italic languages|Italic]] |

||

| fam3 = [[Latino-Faliscan languages|Latino-Faliscan]] |

|||

| contact = |

|||

| |

| ancestor = [[Old Latin]] |

||

| script = [[Latin alphabet]] ([[Latin script]]) |

|||

| mgender = Separate men's & women's championship although no restrictions on women competing against men. |

|||

| agency = [[Pontifical Academy for Latin]] |

|||

| category = |

|||

| |

| iso1 = la |

||

| iso2 = lat |

|||

| olympic = [[Cycling at the Summer Olympics#Mountain bike, men|Since 1996]] |

|||

| iso3 = lat |

|||

| glotto = impe1234 |

|||

| glottorefname = Imperial Latin |

|||

| glotto2 = lati1261 |

|||

| glottorefname2 = Latin |

|||

| lingua = 51-AAB-aa to 51-AAB-ac |

|||

| image = Rome Colosseum inscription 2.jpg |

|||

| imagecaption = Latin inscription, in the [[Colosseum]] of [[Rome]], Italy |

|||

| map = Roman_Empire_Trajan_117AD.png |

|||

| mapcaption = {{legend|#b23938|Greatest extent of the Roman Empire under Emperor [[Trajan]] ({{circa|117 AD}}) and the area governed by Latin speakers.}} Many languages other than Latin were spoken within the empire. |

|||

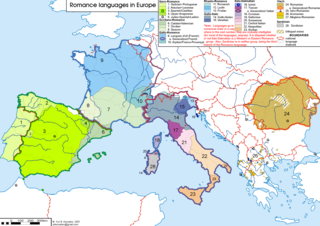

| map2 = Romance_20c_en.png |

|||

| mapcaption2 = Range of the Romance languages, the modern descendants of Latin, in Europe. |

|||

| notice = IPA |

|||

| nation = {{Flag|Vatican City}} |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

'''Latin''' ({{lang|la|lingua Latīna}} {{IPA-la|ˈlɪŋɡʷa ɫaˈtiːna|}} or {{lang|la|Latīnum}} {{IPA-la|ɫaˈtiːnʊ̃|}}) is a [[classical language]] belonging to the [[Italic languages|Italic branch]] of the [[Indo-European languages]]. Latin was originally a [[dialect]] spoken in [[Latium]] (also known as [[Lazio]]), the lower [[Tiber]] area around present-day [[Rome]],<ref>{{cite book |title=A companion to Latin studies |first=John Edwin |last=Sandys |location=Chicago |publisher=[[University of Chicago Press]] |year=1910 |pages=811–812}}</ref> but through the power of the [[Roman Republic]] it became the dominant language in the [[Italian Peninsula|Italic Peninsula]] and subsequently throughout the [[Roman Empire]]. Even after the [[Fall of the Western Roman Empire|fall of Western Rome]], Latin remained the [[common language]] of [[international communication]], science, scholarship and [[academia]] in Europe until well into the 18th century, when other regional vernaculars (including its own descendants, the [[Romance languages]]) supplanted it in common academic and political usage. For most of the time it was used, it would be considered a "[[dead language]]" in the modern linguistic definition; that is, it lacked native speakers, despite being used extensively and actively. |

|||

'''Mountain biking''' is a sport of riding [[bicycle]]s off-road, often over rough terrain, usually using specially designed [[mountain bikes]]. Mountain bikes share similarities with other bikes but incorporate features designed to enhance durability and performance in rough terrain, such as air or coil-sprung shocks used as suspension, larger and wider wheels and tires, stronger frame materials, and mechanically or hydraulically actuated disc brakes. Mountain biking can generally be broken down into five distinct categories: [[Cross-country cycling|cross country]], [[trail riding#Mountain biking|trail riding]], [[Enduro (mountain biking)|all mountain]] (also referred to as "Enduro"), [[Downhill cycling|downhill]], and [[freeride (mountain biking)|freeride]].<ref>{{Cite book|last=Huddart, Stott|first=David, Tim|title=Outdoor Recreation: Environmental Impacts and Management|publisher=Palgrave Macmillan|date=October 25, 2019|isbn=9783319977577|pages=7}}</ref> |

|||

Latin is a [[fusional language|highly inflected language]], with three distinct [[grammatical gender|genders]] (masculine, feminine, and neuter), six or seven [[grammatical case|noun cases]] (nominative, accusative, genitive, dative, ablative, vocative, and vestigial locative), five [[declensions]], four [[grammatical conjugation|verb conjugations]], six [[latin tenses|tenses]] (present, imperfect, future, perfect, pluperfect, and future perfect), three [[grammatical person|persons]], three [[grammatical mood|moods]], two [[voice (grammar)|voices]] (passive and active), two or three [[grammatical aspect|aspects]], and two [[grammatical number|numbers]] (singular and plural). The [[Latin alphabet]] is directly derived from the [[Etruscan alphabet|Etruscan]] and [[Greek alphabet]]s. |

|||

== About == |

|||

This sport requires endurance, core and back strength, balance, bike handling skills, and self-reliance. Advanced riders pursue both steep technical descents and high-incline climbs. In the case of freeride, downhill, and dirt jumping, aerial maneuvers are performed off both natural features and specially constructed jumps and ramps.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Barfe|first=Marion B|title=Mountain Biking: The Ultimate Guide to Mountain Biking For Beginners MTB|year=2019|isbn=978-1982747824}}</ref> |

|||

By the late [[Roman Republic]] (75 BC), [[Old Latin]] had been standardized into [[Classical Latin]]. [[Vulgar Latin]] was the [[colloquial language|colloquial form]] with less prestigious variations attested in inscriptions and the works of comic playwrights [[Plautus]] and [[Terence]]<ref>{{harvnb|Clark|1900|pp=1–3}}</ref> and author [[Petronius]]. [[Late Latin]] is the written language from the 3rd century, and its various Vulgar Latin dialects developed in the 6th to 9th centuries into the modern [[Romance languages]]. |

|||

Mountain bikers ride on off-road trails such as [[Single track (mountain biking)|singletrack]], back-country roads, wider bike park trails, [[Firebreak|fire roads]], and some advanced trails are designed with jumps, berms, and drop-offs to add excitement to the trail. Riders with enduro and downhill bikes will often visit ski resorts that stay open in the summer to ride downhill-specific trails, using the ski lifts to return to the top with their bikes. Because riders are often far from civilization, there is a strong element of self-reliance in the sport. Riders learn to repair broken bikes and flat tires to avoid being stranded. Many riders carry a backpack, including water, food, tools for trailside repairs, and a first aid kit in case of injury. Group rides are common, especially on longer treks. [[Mountain bike orienteering]] adds the skill of map navigation to mountain biking. |

|||

In Latin's usage beyond the early medieval period, it lacked native speakers. [[Medieval Latin]] was used across Western and Catholic Europe during the [[Middle Ages]] as a working and literary language from the 9th century to the [[Renaissance]], which then developed a Classifying and purified form, called [[Renaissance Latin]]. This was the basis for [[Neo-Latin]] which evolved during the [[Early modern period|early modern era]]. In these periods, while Latin was used productively, it was generally taught to be written and spoken, at least until the late seventeenth century, when spoken skills began to erode. Later, it became increasingly taught only to be read. |

|||

One form of Latin, [[Ecclesiastical Latin]], remains the [[official language]] of the [[Holy See]] and the [[Roman Rite]] of the [[Catholic Church]] at [[Vatican City]]. The church continues to adapt concepts from modern languages, contributing to the continued development of the Latin language. [[Contemporary Latin]], however—Neo-Latin in its most recent form—is rarely spoken, and has limited productive use. |

|||

Latin has also [[Latin influence on English|greatly influenced]] the English language and historically contributed [[list of Latin words with English derivatives|many words]] to the English [[lexicon]] after the [[Christianity in Anglo-Saxon England|Christianization of Anglo-Saxons]] and the [[Norman conquest]]. In particular, Latin (and [[Ancient Greek]]) [[root (linguistics)|root]]s are still used in English descriptions of [[theology]], [[list of Latin and Greek words commonly used in systematic names|science disciplines]] (especially [[anatomy]] and [[taxonomy (biology)|taxonomy]]), [[list of medical roots, suffixes and prefixes|medicine]], and [[list of Latin legal terms|law]]. |

|||

{{TOC limit}} |

|||

==History== |

==History== |

||

{{Main|History of Latin}} |

|||

[[Image:25thregiment bicycles.jpg|thumb|US 25th Infantry Bicycle Corps, 1897]] |

|||

[[Image:Mountain-biker-climbs.jpg|thumb|A cross-country mountain biker climbs on an unpaved track]] |

|||

<br /> |

|||

[[File:New mountain bike skills track in Bwlch Nant yr Arian, Powys, Wales.webm|thumb|A mountain bike skills track in [[Wales]]]] |

|||

[[Image:Mountain biking.jpg|thumb|Mountain bike touring in high Alps]] |

|||

[[Image:MountainBiking MtHoodNF.jpg|thumb|right|Mountain biker gets air in [[Mount Hood National Forest]].]] |

|||

===Late 1800s=== |

|||

One of the first examples of bicycles modified specifically for off-road use is the expedition of [[Buffalo Soldiers]] from [[Missoula, Montana]], to [[Yellowstone]] in August 1896.<ref>{{cite web|title=1896 excursion from Fort Missoula, Mont., to Yellowstone National Park, riders of the 25th Infantry Bicycle Corps.|date=30 November 2012 |url=https://www.historynet.com/the-buffalo-soldiers-who-rode-bikes.htm|access-date=2020-04-21}}</ref><ref name=":1">{{Cite web |last=Vendetti |first=Marc |date=2014-01-07 |title=HISTORY {{!}} Marin Museum of Bicycling and Mountain Bike Hall of Fame |url=https://mmbhof.org/mtn-bike-hall-of-fame/history/ |access-date=2023-05-01 |language=en-US}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:Linguistic Landscape of Central Italy.png|thumb|left|upright=1.5|The linguistic landscape of Central Italy at the beginning of Roman expansion]] |

|||

===1900s–1960s=== |

|||

Bicycles were ridden off-road by road racing cyclists who used [[cyclocross]] as a means of keeping fit during the winter.<ref name=":1" /> Cyclo-cross eventually became a sport in its own right in the 1940s, with the first world championship taking place in 1950.<ref name=":1" /> |

|||

A number of phases of the language have been recognized, each distinguished by subtle differences in vocabulary, usage, spelling, and syntax. There are no hard and fast rules of classification; different scholars emphasize different features. As a result, the list has variants, as well as alternative names. |

|||

The Rough Stuff Fellowship was established in 1955 by off-road cyclists in the United Kingdom.<ref>{{cite web |

|||

|url = http://www.rsf.org.uk/history.htm |

|||

|title = Off Road Origins |

|||

|author = Steve Griffith |

|||

|publisher = Rough Stuff Fellowship |

|||

|access-date = 2010-06-18 |

|||

|url-status = dead |

|||

|archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20100721163500/http://www.rsf.org.uk/history.htm |

|||

|archive-date = 2010-07-21 |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

In addition to the historical phases, [[Ecclesiastical Latin]] refers to the styles used by the writers of the [[Roman Catholic Church]] from [[Late Antiquity|late antiquity]] onward, as well as by Protestant scholars. |

|||

In [[Oregon]] in 1966, one Chemeketan club member, D. Gwynn, built a rough terrain trail bicycle. He named it a "mountain bicycle" for its intended place of use. This may be the first use of that name.<ref>{{cite journal |

|||

| title = The Chemeketan |

|||

| volume = 38 |

|||

| date = September 1966 |

|||

| issue = 9 |

|||

| page = 4}}</ref> |

|||

After the [[Western Roman Empire]] fell in 476 and [[Barbarian kingdoms|Germanic kingdoms]] took its place, the [[Germanic people]] adopted Latin as a language more suitable for legal and other, more formal uses.<ref>{{Cite web|title=History of Europe – Barbarian migrations and invasions|url=https://www.britannica.com/topic/history-of-Europe|access-date=2021-02-06|website=Encyclopedia Britannica|language=en}}</ref> |

|||

In England in 1968, [[Geoff Apps]], a motorbike trials rider, began experimenting with off-road bicycle designs. By 1979 he had developed a custom-built lightweight bicycle which was uniquely suited to the wet and muddy off-road conditions found in the south-east of England. They were designed around 2 inch × 650b Nokian snow tires though a 700x47c (28 in.) version was also produced. These were sold under the Cleland Cycles brand until late 1984. Bikes based on the Cleland design were also sold by English Cycles and Highpath Engineering until the early 1990s.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Hadland llast2=Lessing|first=Tony {{!}}first2=Hans-Erhard|title=Bicycle Design : An Illustrated History|publisher=The MIT Press.|year=2014|isbn=9780262026758|location=Cambridge, Massachusetts}}</ref> |

|||

{{Clear}} |

|||

=== |

===Old Latin=== |

||

{{Main|Old Latin}} |

|||

There were several groups of riders in different areas of the U.S.A. who can make valid claims to playing a part in the birth of the sport. Riders in [[Crested Butte, Colorado]], and [[Mill Valley, California]], tinkered with bikes and adapted them to the rigors of off-road riding. Modified heavy [[cruiser bicycle]]s, old 1930s and '40s [[Schwinn]] bicycles retrofitted with better brakes and fat tires, were used for freewheeling down mountain trails in [[Marin County]], [[California]], in the mid-to-late 1970s. At the time, there were no mountain bikes. The earliest ancestors of modern mountain bikes were based around frames from cruiser bicycles such as those made by [[Schwinn]]. The Schwinn Excelsior was the frame of choice due to its geometry. Riders used [[Bicycle tire#Balloon|balloon-tired]] cruisers and modified them with gears and [[motocross]] or BMX-style handlebars, creating "klunkers". The term would also be used as a verb since the term "mountain biking" was not yet in use. The first person known to fit multiple speeds and drum brakes to a klunker is [[Russ Mahon]] of [[Cupertino, California]], who used the resulting bike in [[cyclo-cross]] racing.<ref>{{Cite web |title=From the Mag: Roots - The Cupertino Riders |url=https://dirtmountainbike.com/news/mag-roots-cupertino-riders |access-date=2022-05-22 |website=Dirt |language=en-US}}</ref> Riders would race down mountain [[fire road]]s, causing the hub brake to burn the grease inside, requiring the riders to repack the bearings. These were called "Repack Races" and triggered the first innovations in mountain bike technology as well as the initial interest of the public (on Mt. Tamalpais in Marin CA, there is still a trail titled "Repack"—in reference to these early competitions). The sport originated in California on [[Marin County, California|Marin County]]'s [[Mount Tamalpais]].<ref>{{cite book |

|||

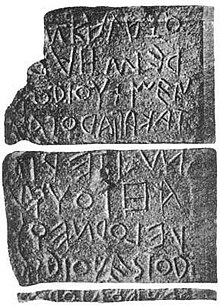

[[Image:Lapis-niger.jpg|thumb|right|The [[Lapis Niger]], probably the oldest extant Latin inscription, from Rome, {{Circa|600 BC|lk=no}} during the semi-legendary [[Roman Kingdom]]]] |

|||

|publisher=Cycle Publishing/Van der Plas Publications |

|||

|url=http://www.cyclepublishing.com/cyclingbooks/ |

|||

|date=January 1, 2008 |

|||

|title=The Birth of Dirt, 2nd Edition |

|||

|isbn=978-1-892495-61-7 |

|||

|access-date=May 29, 2017 |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

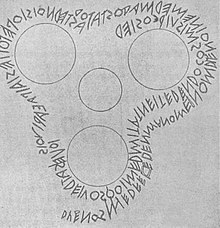

The earliest known form of Latin is Old Latin, also called Archaic or Early Latin, which was spoken from the [[Roman Kingdom]], traditionally founded in 753 BC, through the later part of the [[Roman Republic]], up to 75 BC, i.e. before the age of [[Classical Latin]].<ref>{{cite encyclopedia|title=Archaic Latin|encyclopedia=The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language: Fourth Edition}}</ref> It is attested both in inscriptions and in some of the earliest extant Latin literary works, such as the comedies of [[Plautus]] and [[Terence]]. The [[Latin alphabet]] was devised from the [[Etruscan alphabet]]. The writing later changed from what was initially either a [[Right-to-left script|right-to-left]] or a [[boustrophedon]]<ref>{{harvnb|Diringer|1996|pp=533–4}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book|title = Collier's Encyclopedia: With Bibliography and Index|url = https://books.google.com/books?id=H9xLAQAAMAAJ|publisher = Collier|date = 1 January 1958|language = en|page = 412|quote = In Italy, all alphabets were originally written from right to left; the oldest Latin inscription, which appears on the lapis niger of the seventh century BC, is in boustrophedon, but all other early Latin inscriptions run from right to left.|access-date = 15 February 2016|archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20160421225204/https://books.google.com/books?id=H9xLAQAAMAAJ|archive-date = 21 April 2016|url-status = live}}</ref> script to what ultimately became a strictly left-to-right script.<ref>{{cite book |first=David |last=Sacks |year=2003 |title=Language Visible: Unraveling the Mystery of the Alphabet from A to Z |location=London |publisher=Broadway Books |page=[https://archive.org/details/languagevisibleu00sack/page/80 80] |isbn=978-0-7679-1172-6 |url=https://archive.org/details/languagevisibleu00sack/page/80 }}</ref> |

|||

It was not until the late 1970s and early 1980s that [[road bicycle]] companies started to manufacture mountain bicycles using high-tech lightweight materials. [[Joe Breeze]] is normally credited with introducing the first purpose-built mountain bike in 1978.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Feletti|first=Francesco|title=Extreme Sports Medicine|publisher=Springer International Publishing|date=September 19, 2016|isbn=9783319282657|location=Germany}}</ref> Tom Ritchey then went on to make frames for a company called MountainBikes, a partnership between [[Gary Fisher]], [[Charlie Kelly (businessman)|Charlie Kelly]] and [[Tom Ritchey]]. Tom Ritchey, a welder with skills in frame building, also built the original bikes. The company's three partners eventually dissolved their partnership, and the company became Fisher Mountain Bikes, while Tom Ritchey started his own frame shop. |

|||

===Classical Latin=== |

|||

The first mountain bikes were basically road bicycle frames (with heavier tubing and different geometry) with a wider frame and fork to allow for a wider tire. The handlebars were also different in that they were a straight, transverse-mounted handlebar, rather than the dropped, curved handlebars that are typically installed on road racing bicycles. Also, some of the parts on early production mountain bicycles were taken from the [[BMX]] bicycle. Other contributors were Otis Guy and [[Keith Bontrager]].<ref>Crown, Judith, and Glenn Coleman. ''No Hands : The Rise and Fall of the Schwinn Bicycle Company : An American Institution''. 1st ed., H. Holt, 1996.</ref> |

|||

{{Main|Classical Latin}} |

|||

During the late republic and into the first years of the empire, from about 75 BC to 200 AD, a new [[Classical Latin]] arose, a conscious creation of the orators, poets, historians and other [[literate]] men, who wrote the great works of [[classical literature]], which were taught in [[grammar]] and [[rhetoric]] schools. Today's instructional grammars trace their roots to such [[Roman school|schools]], which served as a sort of informal language academy dedicated to maintaining and perpetuating educated speech.<ref>{{cite book|page=3|title=From Latin to modern French with especial consideration of Anglo-Norman; phonology and morphology|first=Mildred K |last=Pope|author-link=Mildred Pope|location=Manchester|publisher=Manchester university press|series=Publications of the University of Manchester, no. 229. French series, no. 6| year=1966}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|title=Source book of the history of education for the Greek and Roman period|first=Paul|last=Monroe|location=London, New York|publisher=[[Macmillan & Co.]]|year=1902|pages=346–352}}</ref> |

|||

===Vulgar Latin=== |

|||

[[Tom Ritchey]] built the first regularly available mountain bike frame, which was accessorized by Gary Fisher and [[Charlie Kelly (businessman)|Charlie Kelly]] and sold by their company called MountainBikes (later changed to Fisher Mountain Bikes, then bought by [[Trek Bicycle Corporation|Trek]], still under the name Gary Fisher, currently sold as Trek's "Gary Fisher Collection"). The first two mass-produced mountain bikes were sold in the early 1980s: the [[Specialized Stumpjumper]] and Univega Alpina Pro. In 1988, ''[[The Great Mountain Biking Video]]'' was released, soon followed by others. In 2007, ''[[Klunkerz: A Film About Mountain Bikes]]'' was released, documenting mountain bike history during the formative period in Northern California. Additionally, a group of mountain bikers called the Laguna Rads formed a club during the mid eighties and began a weekly ride, exploring the uncharted coastal hillsides of Laguna Beach, California.<ref>{{Cite web|title=The Laguna Rads {{!}} Marin Museum of Bicycling and Mountain Bike Hall of Fame|url=https://mmbhof.org/the-laguna-rads/|website=mmbhof.org|date=26 March 2014 |access-date=2020-05-04}}</ref> Industry insiders suggest that this was the birth of the freeride movement, as they were cycling up and down hills and mountains where no cycling specific trail network prexisted. The Laguna Rads have also held the longest running downhill race once a year since 1986. |

|||

{{Main|Vulgar Latin}} |

|||

Philological analysis of Archaic Latin works, such as those of [[Plautus]], which contain fragments of everyday speech, gives evidence of a spoken register of the language, Vulgar Latin (termed {{lang|la|sermo vulgi}}, "the speech of the masses", by [[Cicero]]). Some linguists, particularly in the nineteenth century, believed this to be a separate language, existing more or less in parallel with the literary or educated Latin, but this is now widely dismissed.<ref>{{harvnb|Herman|2000|p=5}} "Comparative scholars, especially in the nineteenth century … tended to see Vulgar Latin and literary Latin as two very different kinds of language, or even two different languages altogether … but [this] is now out of date"</ref> |

|||

At the time, the bicycle industry was not impressed with the mountain bike, regarding mountain biking to be short-term fad. In particular, large manufacturers such as Schwinn and [[Fuji Advanced Sports|Fuji]] failed to see the significance of an all-terrain bicycle and the coming boom in 'adventure sports'. Instead, the first mass-produced mountain bikes were pioneered by new companies such as MountainBikes (later, Fisher Mountain Bikes), Ritchey, and [[Specialized Bicycles|Specialized]]. Specialized was an American startup company that arranged for production of mountain bike frames from factories in Japan and Taiwan. First marketed in 1981,<ref name="Rogers">{{cite news|url=http://www.bikeradar.com/news/article/interview-specialized-founder-mike-sinyard-28233|title=Interview: Specialized founder Mike Sinyard|last=Rogers|first=Seb|publisher=BikeRadar|date=23 October 2010|access-date=2 December 2010}}</ref> Specialized's mountain bike largely followed Tom Ritchey's frame geometry, but used TiG welding to join the frame tubes instead of fillet-brazing, a process better suited to mass production, and which helped to reduce labor and manufacturing cost.<ref>Ballantine, Richard, ''Richard's 21st Century Bicycle Book'', New York: Overlook Press (2001), {{ISBN|1-58567-112-6}}, pp. 25, 50</ref> The bikes were configured with 15 gears using [[derailleur gears|derailleurs]], a triple [[sprocket|chainring]], and a [[cogset]] with five sprockets. |

|||

The term 'Vulgar Latin' remains difficult to define, referring both to informal speech at any time within the history of Latin, and the kind of informal Latin that had begun to move away from the written language significantly in the post Imperial period, that led to [[Proto-Romance language|Proto-Romance]]. |

|||

===1990s–2000s=== |

|||

During the Classical period, the informal language was rarely written, so philologists have been left with only individual words and phrases cited by classical authors, inscriptions such as [[Curse tablets]] and those found as [[Roman graffiti|graffiti]]. In the [[Late Latin]] period, language reflecting spoken norms tend to be found in greater quantities in texts.<ref>{{harvnb|Herman|2000|pp=17–18}}</ref> |

|||

Throughout the 1990s and first decade of the 21st century, mountain biking moved from a little-known sport to a mainstream activity. Mountain bikes and mountain bike gear, once only available at specialty shops or via mail order, became available at standard bike stores. By the mid-first decade of the 21st century, even some department stores began selling inexpensive mountain bikes with full-suspension and disc brakes. In the first decade of the 21st century, trends in mountain bikes included the "all-mountain bike", the [[29er (bicycle)|29er]] and the one by drivetrain (though the first mass-produced 1x drivetrain was Sram's XX1 in 2012). "All-mountain bikes" were designed to descend and handle well in rough conditions, while still pedaling efficiently for climbing, and were intended to bridge the gap between cross-country bikes and those built specifically for downhill riding. They are characterized by {{convert|4|–|6|in|mm|abbr=off}} of fork travel. 29er bikes are those using 700c sized rims (as do most road bikes), but wider and suited for tires of two inches (50 mm) width or more; the increased diameter wheel is able to roll over obstacles better and offers a greater tire [[contact patch]], but also results in a longer wheelbase, making the bike less agile, and in less travel space for the suspension. The single-speed is considered a return to simplicity with no drivetrain components or shifters but thus requires a stronger rider. |

|||

As it was free to develop on its own, there is no reason to suppose that the speech was uniform either diachronically or geographically. On the contrary, Romanised European populations developed their own dialects of the language, which eventually led to the differentiation of [[Romance languages]].<ref>{{harvnb|Herman|2000|p=8}}</ref> |

|||

=== |

===Late Latin=== |

||

{{Main|Late Latin}} |

|||

Following the growing trend in 29-inch wheels, there have been other trends in the mountain biking community involving tire size. Some riders prefer to have a larger wheel in the front than on the rear, such as on a motorcycle, to increase maneuverability. This is called a mullet bicycle, most common with a 29-inch wheel in the front and a 27.5-inch wheel in the back. Another interesting trend in mountain bikes is outfitting dirt jump or urban bikes with rigid forks. These bikes normally use 4–5″ travel suspension forks. The resulting product is used for the same purposes as the original bike. A commonly cited reason for making the change to a rigid fork is the enhancement of the rider's ability to transmit force to the ground, which is important for performing tricks. In the mid-first decade of the 21st century, an increasing number of mountain bike-oriented resorts opened. Often, they are similar to or in the same complex as a [[ski resort]] or they retrofit the concrete steps and platforms of an abandoned factory as an obstacle course, as with [[Ray's MTB Indoor Park]]. Mountain bike parks which are operated as summer season activities at ski hills usually include chairlifts that are adapted to bikes, a number of trails of varying difficulty, and bicycle rental facilities.<ref>{{Cite web|title=mountain biking|url=http://waicol.digi.school.nz/year09/2017/Connor%27s%20website/mountainBiking.html|website=waicol.digi.school.nz|access-date=2020-05-04}}</ref> |

|||

Late Latin is the kind of written Latin used in the 3rd to 6th centuries. This began to diverge from Classical forms at a faster pace. It is characterised by greater use of prepositions, and word order that is closer to modern Romance languages, for example, while grammatically retaining more or less the same formal rules as Classical Latin. |

|||

In 2020, due to [[COVID-19]], mountain bikes saw a surge in popularity in the US, with some vendors reporting that they were sold out of bikes under US$1000.<ref>{{Cite web|title=Mountain Biking Experiencing a Surge in Popularity|url=https://thelaker.com/2020/mountain-biking-experiencing-a-surge-in-popularity|access-date=2021-01-12|website=The Laker|date=24 June 2020 |language=en-US}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|last=Newcomb|first=Tim|title=Amid Cycling Surge, Sport Of Mountain Biking Is Seeing Increased Sales And Trail Usage|url=https://www.forbes.com/sites/timnewcomb/2020/07/13/amidst-cycling-surge-sport-of-mountain-biking-seeing-increased-sales-trail-usage/|access-date=2021-01-12|website=Forbes|language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|last=Stephenson|first=Brayden|date=2020-09-15|title=Mountain biking gains popularity during Covid-19 lockdown|url=https://snceagleseye.com/11808/outdoor/mountain-biking-gains-popularity-during-covid-19-lockdown/|access-date=2021-01-12|website=Eagle's Eye}}</ref> |

|||

Ultimately, Latin diverged into a distinct written form, where the commonly spoken form was perceived as a separate language, for instance early French or Italian dialects, that could be transcribed differently. It took some time for these to be viewed as wholly different from Latin however. |

|||

==Equipment== |

|||

=== |

===Romance languages=== |

||

{{Main|Romance languages}} |

|||

[[File:HardtailMountainBike 2010 Specialized Rockhopper.jpg|thumb|A hardtail mountain bike]] |

|||

{{See also|Lexical changes from Classical Latin to Proto-Romance}} |

|||

[[File:Example all-mountain MTB.jpg|thumb|A dual suspension or full suspension mountain bike, 'all-mountain' mountain bike]] |

|||

While the written form of Latin began to evolve into a fixed form, the spoken forms began to diverge more greatly. Currently, the five most widely spoken [[Romance languages]] by number of native speakers are [[Spanish language|Spanish]], [[Portuguese language|Portuguese]], [[French language|French]], [[Italian language|Italian]], and [[Romanian language|Romanian]]. Despite dialectal variation, which is found in any widespread language, the languages of Spain, France, Portugal, and Italy have retained a remarkable unity in phonological forms and developments, bolstered by the stabilising influence of their common [[Christians|Christian]] (Roman Catholic) culture. |

|||

[[Image:All Mountain Mountain Bike.jpg|thumb|Typical more stout all-mountain bike on rough terrain]] |

|||

{{Main|Mountain bike}} |

|||

*'''[[Mountain bike]]s''' differ from other bikes primarily in that they incorporate features aimed at increasing durability and improving performance in rough terrain. Most modern mountain bikes have some kind of [[Bicycle suspension|suspension]], 26, 27.5 or 29-inch diameter tires, usually between 1.7 and 2.5 inches in width, and a wider, flat or upwardly-rising [[Bicycle handlebar|handlebar]] that allows a more upright riding position, giving the rider more control. They have a smaller, reinforced [[bicycle frame|frame]], usually made of wide tubing. Tires usually have a pronounced [[tire tread|tread]], and are mounted on rims which are stronger than those used on most non-mountain bicycles. Compared to other bikes, mountain bikes also use [[hydraulic disc brakes]]. They also tend to have lower ratio [[bicycle gearing|gears]] to facilitate climbing steep hills and traversing obstacles. [[Bicycle pedal|Pedals]] vary from simple ''[[Bicycle pedal#Flat and platform|platform]]'' pedals, where the rider simply places the shoes on top of the pedals, to ''[[Clipless pedals|clipless]]'', where the rider uses a specially equipped shoe with a cleat that engages mechanically into the pedal. |

|||

It was not until the [[Umayyad conquest of Hispania|Muslim conquest of Spain]] in 711, cutting off communications between the major Romance regions, that the languages began to diverge seriously.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Pei |first1=Mario |last2=Gaeng |first2=Paul A. |title=The story of Latin and the Romance languages |edition=1st |year=1976 |pages=[https://archive.org/details/storyoflatinroma0000peim/page/76 76–81] |location=New York |publisher=Harper & Row |isbn=978-0-06-013312-2 |url=https://archive.org/details/storyoflatinroma0000peim/page/76 }}</ref> The spoken Latin form (often called Vulgar Latin, or at other times [[Proto-Romance]]) that would later become [[Romanian language|Romanian]] diverged somewhat more from the other varieties, as it was largely separated from the unifying influences in the western part of the Empire. |

|||

===Accessories=== |

|||

*'''Glasses''' with little or no difference from those used in other cycling sports, help protect against [[road debris|debris]] while on the trail. Filtered lenses, whether yellow for cloudy days or shaded for sunny days, protect the eyes from strain. Downhill, freeride, and enduro mountain bikers often use goggles similar to motocross or snowboard goggles in unison with their full face helmets. |

|||

*'''[[Bicycle shoe|Shoes]]''' generally have gripping soles similar to those of hiking boots for scrambling over un-ridable obstacles, unlike the smooth-bottomed shoes used in road cycling. The [[shank (footwear)|shank]] of mountain bike shoes is generally more flexible than road cycling shoes. Shoes compatible with clipless pedal systems are also frequently used. |

|||

*'''Clothing''' is chosen for comfort during physical exertion in the backcountry, and its ability to withstand falls. Road touring clothes are often inappropriate due to their delicate fabrics and construction. Depending on the type of mountain biking, different types of clothes and styles are commonly worn. Cross-country mountain bikers tend to wear lycra shorts and tight road style jerseys due to the need for comfort and efficiency. Downhill riders tend to wear heavier fabric baggy shorts or moto-cross style trousers to protect themselves from falls. All mountain/enduro riders tend to wear light fabric baggy shorts and jerseys as they can be in the saddle for long periods of time. |

|||

*'''[[Hydration system]]s''' are important for mountain bikers in the backcountry, ranging from simple water bottles to water bags with drinking tubes in lightweight backpacks known as a hydration pack. (e.g.[[CamelBak]]s). |

|||

*'''[[GPS navigation devices|GPS systems]]''' are sometimes added to the handlebars and are used to monitor progress on trails. |

|||

*'''[[Bicycle pump|Pump]]''' to inflate tires. |

|||

*'''[[Carbon dioxide|{{CO2}} Inflator with Cartridge]]''' to inflate a tube or [[Tubeless tire#Bicycle tires|tubeless tire]]. |

|||

*'''[[Bicycle tools|Bike tools]]''' and extra bike tubes are important, as mountain bikers frequently find themselves miles from help, with flat tires or other mechanical problems that must be handled by the rider. |

|||

*'''[[Bicycle lighting#LEDs|High-power lights]]''' based on LED technology, used for mountain biking at night. |

|||

*Some sort of '''protective case''' |

|||

Spoken Latin began to diverge into distinct languages by the 9th century at the latest, when the earliest extant Romance writings begin to appear. They were, throughout the period, confined to everyday speech, as Medieval Latin was used for writing.<ref name=":0">{{Cite web|url=https://www.ruf.rice.edu/~kemmer/Words04/structure/latin.html|title=History of Latin|last=Pulju|first=Timothy|website=Rice University|access-date=3 December 2019}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.britannica.com/topic/Romance-languages/Latin-and-the-development-of-the-Romance-languages#ref74713|title=Romance Languages|last1=Posner|first1=Rebecca|last2=Sala|first2=Marius|date=1 August 2019|website=Encyclopædia Britannica|access-date=3 December 2019}}</ref> |

|||

===Protective gear=== |

|||

{{manual|section|date=February 2016}} |

|||

[[File:Worsleys Track 248.webm|thumb|Mountain bikers in the [[Port Hills]], New Zealand, wearing a variety of protective gear]] |

|||

The level of protection worn by individual riders varies greatly and is affected by speed, trail conditions, the weather, and numerous other factors, including personal choice. Protection becomes more important where these factors may be considered to increase the possibility or severity of a crash. |

|||

It should also be noted, however, that for many Italians using Latin, there was no complete separation between Italian and Latin, even into the beginning of the [[Renaissance]]. [[Petrarch]] for example saw Latin as an artificial and literary version of the spoken language.<ref>See Introduction, {{harvnb|Deneire|2014|pp=10–11}}</ref> |

|||

A helmet and gloves are usually regarded as sufficient for the majority of non-technical riding. Full-face helmets, goggles and armored suits or jackets are frequently used in downhill mountain biking, where the extra bulk and weight may help mitigate the risks of bigger and more frequent crashes.<ref>{{cite book|title=Complete Mountain Biking Manual|first=Tim|last=Brink|year=2007|location=London|publisher=New HollandPublishers|pages=40–61|isbn=978-1845372941}}</ref> |

|||

===Medieval Latin=== |

|||

*'''[[Bicycle helmet|Helmet]]'''. The use of helmets, in one form or another, is almost universal amongst mountain bikers. The three main types are; cross-country, rounded skateboarder style (nicknamed "half shells" or "skate style"), and full-face. Cross-country helmets tend to be light and well ventilated, and more comfortable to wear for long periods, especially while perspiring in hot weather. In XC competitions, most bikers tend to use the usual road-racing style helmets, for their lightweight and aerodynamic qualities. Skateboard helmets are simpler and usually more affordable than other helmet types; provide great coverage of the head and resist minor scrapes and knocks. Unlike road-biking helmets, skateboard helmets typically have a thicker, hard plastic shell which can take multiple impacts before it needs to be replaced. The trade-off for this is that they tend to be much heavier and less ventilated (sweatier), therefore not suitable for endurance-based riding. Full-face helmets (BMX-style) provide the highest level of protection and tend to be stronger than skateboarding style and includes a jaw guard to protect the face. The weight is the main issue with this type, but today they are often reasonably well-ventilated and made of lightweight materials such as carbon fiber. (Full-face helmets with detachable chin-guards are available in some locations, but there are compromises to keep in mind with these designs.) As all helmets should meet minimum standards, SNELL B.95 (American Standard) BS EN 1078:1997 (European Standard), DOT, or "motorized ratings" are making their way into the market. The choice of helmet often comes down to rider preference, the likelihood of crashing, and on what features or properties of a helmet they place emphasis. Helmets are mandatory at competitive events and almost without exception at bike parks, most organizations also stipulate when and where full-face helmets must be used.<ref>Grant, Darren, and Stephen M. Rutner. "The Effect of Bicycle Helmet Legislation on Bicycling Fatalities." Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, vol. 23, no. 3, 2004, pp. 595–611. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3326268. Accessed 10 May 2020.</ref> |

|||

{{Main|Medieval Latin}} |

|||

*'''Body armor and pads''', often referred to simply as "armor", are meant to protect limbs and body in the event of a crash. While initially made for and marketed for downhill riders, free-riders, and jump/street riders, body armor has trickled into other areas of mountain biking as trails have become steeper and more technically complex (hence bringing a commensurately higher injury risk). Armor ranges from simple neoprene sleeves for knees, and elbows to complex, articulated combinations of hard plastic shells and padding that cover a whole limb or the entire body. Some companies market body armor jackets and even full-body suits designed to provide greater protection through greater coverage of the body and more secure pad retention. Most upper-body protectors also include a spine protector that comprises plastic or metal reinforced plastic plates, over foam padding, which are joined so that they articulate and move with the back. Some mountain bikers also use BMX-style body armor, such as chest plates, abdomen protectors, and spine plates. New technology has seen an influx of integrated neck protectors that fit securely with full-face helmets, such as the [[Leatt-Brace]]. There is a general correlation between increased protection and increased weight/decreased mobility, although different styles balance these factors differently. Different levels of protection are deemed necessary/desirable by different riders in different circumstances. Backpack hydration systems such as [[Camelbak]]s, where a water-filled bladder is held close to the spine, are used by some riders for their perceived protective value. More recently, with the increase in enduro racing, backpack hydration systems are also being sold with inbuilt spine protection. However, there is only anecdotal evidence of protection. |

|||

[[File:Calligraphy.malmesbury.bible.arp.jpg|thumb|upright=1.13|The Latin Malmesbury Bible from 1407]] |

|||

*'''[[Cycling gloves|Gloves]]''' can offer increased comfort while riding, by alleviating compression and friction, and can protect against superficial hand injuries.<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Kloss|first1=F.R|last2=Tuli|first2=T|last3=Haechl|first3=O|last4=Gassner|first4=R|year=2006|title=Trauma injuries sustained by cyclists|journal=Trauma|volume=8, 2|pages=83|via=Scopus}}</ref> They provide protection in the event of strikes to the back or palm of the hand or when putting the hand out in a fall and can protect the hand, fingers, and knuckles from abrasion on rough surfaces. Many different styles of gloves exist, with various fits, sizes, finger lengths, palm padding, and armor options available. Armoring knuckles and the backs of hands with plastic panels is common in more extreme types of mountain biking. Most of it depends on preference and necessity. |

|||

Medieval Latin is the written Latin in use during that portion of the postclassical period when no corresponding Latin [[vernacular]] existed, that is from 700 to 1500 AD. The spoken language had developed into the various incipient Romance languages; however, in the educated and official world, Latin continued without its natural spoken base. Moreover, this Latin spread into lands that had never spoken Latin, such as the Germanic and Slavic nations. It became useful for international communication between the member states of the [[Holy Roman Empire]] and its allies. |

|||

*'''First aid''' kits are often carried by mountain bikers so that they are able to clean, dress cuts, abrasions, and splint broken limbs. Head, brain, and spinal injuries become more likely as speeds increase. All of these can bring permanent changes in quality of life. Experienced mountain bike guides may be trained in dealing with suspected spinal injuries (e.g., immobilizing the victim and keeping the neck straight). Seriously injured people may need to be removed by [[stretcher]], by a motor vehicle suitable for the terrain, or by helicopter. |

|||

Protective gear cannot provide immunity against injuries. For example, concussions can still occur despite the use of helmets, and spinal injuries can still occur with the use of spinal padding and neck braces.<ref>[http://www.amjorthopedics.com/specialty-focus/trauma/article/extreme-sports-provide-thrills-but-also-increased-incidence-of-head-and-neck-injuries.html Extreme Sports Provide Thrills But Also Increased Incidence of Head and Neck Injuries]{{Dead link|date=April 2020 |bot=InternetArchiveBot |fix-attempted=yes }} AAOS News</ref><ref>{{cite journal | last1 = Sharma | first1 = Vinay K. | last2 = Rango | first2 = Juan | last3 = Connaughton | first3 = Alexander J. | last4 = Lombardo | first4 = Daniel J. | last5 = Sabesan | first5 = Vani J. | title = The Current State of Head and Neck Injuries in Extreme Sports | journal = Orthopedic Journal of Sports Medicine | volume = 3 | issue = 1| pages = 2325967114564358 | year = 2015 | pmc = 4555583 | pmid = 26535369 | doi = 10.1177/2325967114564358 }}</ref> The use of high-tech protective gear can result in a revenge effect, whereupon some cyclists feel safe taking dangerous risks.<ref>Tenner, Edward. [http://www.edwardtenner.com/why_things_bite_back__technology_and_the_revenge_of_unintended_consequences_21108.htm Why Thing Bite Back: Technology and the Revenge of Unintended Consequences.] Retrieved November 26, 2015</ref> |

|||

Without the institutions of the Roman Empire that had supported its uniformity, medieval Latin lost its linguistic cohesion: for example, in classical Latin {{lang|la|sum}} and {{lang|la|eram}} are used as auxiliary verbs in the perfect and pluperfect passive, which are compound tenses. Medieval Latin might use {{lang|la-x-medieval|fui}} and {{lang|la-x-medieval|fueram}} instead.<ref name=thorley13-15>{{cite book|pages=13–15|title=Documents in medieval Latin|first=Moe|last=Elabani|location=Ann Arbor|publisher=University of Michigan Press|year=1998|isbn=978-0-472-08567-5}}</ref> Furthermore, the meanings of many words have been changed and new vocabularies have been introduced from the vernacular. Identifiable individual styles of classically incorrect Latin prevail.<ref name=thorley13-15/> |

|||

Because the key determinant of injury risk is [[kinetic energy]], and because kinetic energy increases with the square of the speed, effectively each doubling of speed can quadruple the injury risk. Similarly, each tripling of speed can be expected to bring a nine-fold increase in risk, and each quadrupling of speed means that a sixteen-fold risk increase must be anticipated. |

|||

Higher speeds of travel also add danger due to [[Mental chronometry|reaction time]]. Because higher speeds mean that the rider travels further during his/her reaction time, this leaves less travel distance within which to react safely.<ref>Adventure and Extreme Sports Injuries: Epidemiology, Treatment, Rehabilitation, and Prevention. By Omer Mei-Dan, Michael Carmont, Ed. Springer-Verlag, London, 2013.</ref> This, in turn, further multiplies the risk of an injurious crash. |

|||

===Renaissance and Neo-Latin=== |

|||

In general, although protective gear cannot always prevent the occurrence of injuries, the use of such equipment is appropriate, as is maintaining it in serviceable condition. Because mountain biking takes place outdoors, ultraviolet radiation from sunlight is present, and UV rays are known to degrade plastic components.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Yousif E, Haddad R | title = Photodegradation and photostabilization of polymers, especially polystyrene: review | journal = SpringerPlus | volume = 2 | issue = 398 | date = 2013 | page = 398 | pmid = 25674392 | doi = 10.1186/2193-1801-2-398 | pmc = 4320144 | doi-access = free }}</ref> Accordingly, and as a rule of thumb, a bicycle helmet should be replaced every five years, or sooner if it appears damaged. Additionally, if the helmet has been involved in an accident or has otherwise incurred impact-type damage, then it should be replaced promptly, even if it does not appear to be visibly damaged.<ref>{{Cite news|title=Bike Helmet Buying Guide|url=https://www.consumerreports.org/cro/bike-helmets/buying-guide/index.htm|website=Consumer Reports|language=en-US|access-date=2020-05-09}}</ref> |

|||

{{Main|Renaissance Latin|Neo-Latin}} |

|||

[[File:Incunabula distribution by language.png|thumb|Most 15th-century printed books ([[incunabula]]) were in Latin, with the [[vernacular language]]s playing only a secondary role.<ref name="ISTC">{{cite web |url=https://www.bl.uk/catalogues/istc/index.html |title=Incunabula Short Title Catalogue |publisher=[[British Library]] |access-date=2 March 2011 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110312185857/https://www.bl.uk/catalogues/istc/index.html |archive-date=12 March 2011 |url-status=live }}</ref>]] |

|||

Renaissance Latin, 1300 to 1500, and the classicised Latin that followed through to the present are often grouped together as ''Neo-Latin'', or New Latin, which have in recent decades become a focus of [[Neo-Latin studies|renewed study]], given their importance for the development of European culture, religion and science.<ref>"When we talk about "Neo-Latin", we refer to the Latin … from the time of the early Italian humanist Petrarch (1304–1374) up to the present day" {{harvnb|Knight|Tilg|2015|p=1}}</ref><ref>"Neo-Latin is the term used for the Latin which developed in Renaissance Italy … Its origins are normally associated with Petrarch" {{Cite web |url=http://www.mml.cam.ac.uk/neo-latin |title=What is Neo-Latin? |access-date=2016-10-09 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161009191707/http://www.mml.cam.ac.uk/neo-latin |archive-date=2016-10-09 |url-status=dead }}</ref> The vast majority of written Latin belongs to this period, but its full extent is unknown.<ref>{{harvnb|Demo|2022|p=3}}</ref> |

|||

==Categories== |

|||

The [[Renaissance]] reinforced the position of Latin as a spoken and written language by the scholarship by the [[Renaissance Humanism|Renaissance Humanists]]. [[Petrarch]] and others began to change their usage of Latin as they explored the texts of the Classical Latin world. Skills of textual criticism evolved to create much more accurate versions of extant texts through the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, and some important texts were rediscovered. Comprehensive versions of author's works were published by [[Isaac Casaubon]], [[Joseph Scaliger]] and others.<ref>''Latin Studies'' in {{harvnb|Bergin|Law|Speake|2004|p=272}}</ref> Nevertheless, despite the careful work of Petrarch, [[Politian]] and others, first the demand for manuscripts, and then the rush to bring works into print, led to the circulation of inaccurate copies for several centuries following.<ref>''Criticism, textual'' in {{harvnb|Bergin|Law|Speake|2004|p=272}}</ref> |

|||

===Cross-country cycling=== |

|||

{{Main|Cross-country cycling}} |

|||

Neo-Latin literature was extensive and prolific, but less well known or understood today. Works covered poetry, prose stories and early novels, occasional pieces and collections of letters, to name a few. Famous and well regarded writers included Petrarch, Erasmus, [[Salutati]], [[Conrad Celtes|Celtis]], [[George Buchanan]] and [[Thomas More]].<ref>''Neo-Latin literature'' in {{harvnb|Bergin|Law|Speake|2004|pp=338–9}}</ref> Non fiction works were long produced in many subjects, including the sciences, law, philosophy, historiography and theology. Famous examples include [[Isaac Newton]]'s ''[[Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica|Principia]]''. Later, Latin was used as a convenient medium for translations of important works, such as those of [[Descartes]]. |

|||

Cross-Country (XC) generally means riding point-to-point or in a loop including climbs and descents on a variety of terrain. A typical XC bike weighs around 9-13 kilos (20-30 lbs), and has {{convert|0|-|125|mm|in|abbr=off|sp=us}} of suspension travel front and sometimes rear. Cross country mountain biking focuses on physical strength and endurance more than the other forms, which require greater technical skill. Cross country mountain biking is the only mountain biking discipline in the [[Summer Olympic Games]]. |

|||

Latin education underwent a process of reform to Classicise written and spoken Latin. Schooling remained largely Latin medium until approximately 1700. Until the end of the 17th century, the majority of books and almost all diplomatic documents were written in Latin.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Helander |first=Hans |date=2012-04-01 |title=The Roles of Latin in Early Modern Europe |url=https://journals.openedition.org/annuaire-cdf/1783 |journal=L'Annuaire du Collège de France. Cours et travaux |language=en |issue=111 |pages=885–887 |doi=10.4000/annuaire-cdf.1783 |s2cid=160298764 |issn=0069-5580}}</ref> Afterwards, most diplomatic documents were written in French (a [[Romance language]]) and later native or other languages.<ref>Laureys, Marc, ''Political Action'' in {{harvnb|Knight|Tilg|2015|p=356}}</ref> Education methods gradually shifted towards written Latin, and eventually concentrating solely on reading skills. The decline of Latin education took several centuries and proceeded much more slowly than the decline in written Latin output. |

|||

===All-mountain/Enduro=== |

|||

{{Main|Enduro (mountain biking)}} |

|||

===Contemporary Latin=== |

|||

All-mountain/Enduro bikes tend to have moderate-travel suspension systems and components which are stronger than XC models, typically 160-180 mm of travel on a full suspension frame, but at a weight that is suitable for both climbing and descending. |

|||

{{Main|Contemporary Latin|Ecclesiastical Latin}} |

|||

Despite having no native speakers, Latin is still used for a variety of purposes in the contemporary world. |

|||

Enduro racing includes elements of DH racing, but Enduro races are much longer, sometimes taking a full day to complete, and incorporate climbing sections to connect the timed downhill descents (often referred to as stages). Typically, there is a maximum time limit for how long a rider takes to reach the top of each climb, while finishers of the downhill portions are ranked by fastest times. |

|||

==== Religious use ==== |

|||

Historically, many long-distance XC races would use the descriptor "enduro" in their race names to indicate their endurance aspect. Some long-standing race events have maintained this custom, sometimes leading to confusion with the modern Enduro format, that has been adopted to the Enduro World Series. |

|||

[[File:Wallsend platfom 2 02.jpg|thumb|The signs at [[Wallsend Metro station]] are in English and Latin, as a tribute to [[Wallsend]]'s role as one of the outposts of the [[Roman Empire]], as the eastern end of [[Hadrian's Wall]] (hence the name) at [[Segedunum]].]] |

|||

The largest organisation that retains Latin in official and quasi-official contexts is the [[Catholic Church]]. The Catholic Church required that Mass be carried out in Latin until the Second Vatican Council of 1962–1965, which permitted the use of the [[vernacular language|vernacular]]. Latin remains the language of the [[Roman Rite]]. The [[Tridentine Mass]] (also known as the Extraordinary Form or Traditional Latin Mass) is celebrated in Latin. Although the [[Mass of Paul VI]] (also known as the Ordinary Form or the Novus Ordo) is usually celebrated in the local vernacular language, it can be and often is said in Latin, in part or in whole, especially at multilingual gatherings. It is the official language of the [[Holy See]], the primary language of its [[public journal]], the {{lang|la|[[Acta Apostolicae Sedis]]}}, and the working language of the [[Roman Rota]]. [[Vatican City]] is also home to the world's only [[automatic teller machine]] that gives instructions in Latin.<ref>{{cite news |last=Moore |first=Malcolm |title=Pope's Latinist pronounces death of a language |url=https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/1540843/Popes-Latinist-pronounces-death-of-a-language.html |work=[[The Daily Telegraph]] |date=28 January 2007|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090826081734/https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/1540843/Popes-Latinist-pronounces-death-of-a-language.html |archive-date=26 August 2009 |url-status=live }}</ref> In the [[pontifical university|pontifical universities]] postgraduate courses of [[Canon law]] are taught in Latin, and papers are written in the same language. |

|||

Enduro racing was commonly seen as a race for all abilities. While there are many recreational riders that do compete in Enduro races, the sport is increasingly attracting high-level riders such as [[Sam Hill (cyclist)|Sam Hill]] or [[Isabeau Courdurier]]. |

|||

There are a small number of Latin services held in the Anglican church. These include an annual service in Oxford, delivered with a Latin sermon; a relic from the period when Latin was the normal spoken language of the university.<ref>{{cite web |title=University Sermons |url=https://www.universitychurch.ox.ac.uk/content/university-sermons |website=University Church Oxford |access-date=25 March 2023}}</ref> |

|||

===Downhill=== |

|||

{{Main|Downhill mountain biking}} |

|||

[[Image:MTB downhill.jpg|thumb|[[Downhill mountain biking]]]] |

|||

Downhill (DH) is, in the most general sense, riding mountain bikes downhill. Courses include large jumps (up to and including {{convert|12|m|ft|abbr=off|sp=us}}), drops of 3+ meters (10+ feet), and are generally rough and steep from top to bottom. The rider commonly travels to the point of descent by other means than cycling, such as a ski lift or automobile, as the weight of the downhill mountain bike often precludes any serious climbing. |

|||

Because of the extremely steep terrain (often located in summer at ski resorts), downhill mountain biking is one of the most extreme and dangerous cycling disciplines. Minimum body protection in a true downhill setting entails wearing knee pads and a full-face helmet with goggles, albeit riders and racers commonly wear various forms of full-body suits that include padding at selected locations. |

|||

[[File:Former logo of the European Council and Council of the European Union (2009).svg|thumb|right|The polyglot [[European Union]] has adopted Latin names in the logos of some of its institutions for the sake of linguistic compromise, an "ecumenical nationalism" common to most of the continent and as a sign of the continent's heritage (such as the [[Council of the European Union|EU Council]]: {{lang|la|Consilium}}).]] |

|||

Downhill-specific bikes are universally equipped with front and rear suspension, large disc brakes, and use heavier frame tubing than other mountain bikes. Downhill bicycles now weigh around {{convert|16|-|20|kg|lb|abbr=on}}, while the most expensive professional downhill mountain bikes can weigh as little as {{convert|15|kg|lb|abbr=off}}, fully equipped with custom carbon fiber parts, air suspension, tubeless tires and more. Downhill frames have anywhere from {{convert|170|-|250|mm|in|abbr=off|sp=us}} of travel and are usually equipped with a {{convert|200|mm|in|abbr=off|sp=us}} travel dual-crown fork. |

|||

==== Use of Latin for mottos ==== |

|||

===Four-cross/Dual Slalom=== |

|||

In the Western world, many organizations, governments and schools use Latin for their mottos due to its association with formality, tradition, and the roots of [[Western culture]].<ref>{{Cite web|title="Does Anybody Know What 'Veritas' Is?" {{!}} Gene Fant|url=https://www.firstthings.com/blogs/firstthoughts/2011/08/e2809cdoes-anybody-know-what-veritas-ise2809d|access-date=2021-02-19|website=First Things|date=August 2011 |language=en}}</ref> |

|||

{{Main|Four-cross}} |

|||

[[File:4cross.JPG|thumb|Four-cross race]] |

|||

Canada's motto {{lang|la|[[A mari usque ad mare]]}} ("from sea to sea") and most [[list of Canadian provincial and territorial symbols|provincial mottos]] are also in Latin. The [[Victoria Cross (Canada)|Canadian Victoria Cross]] is modelled after the British [[Victoria Cross]] which has the inscription "For Valour". Because Canada is officially bilingual, the Canadian medal has replaced the English inscription with the Latin {{lang|la|Pro Valore}}. |

|||

Four-cross/Dual Slalom (4X) is a discipline in which riders compete either on separate tracks, as in Dual Slalom, or on a short slalom track, as in 4X. Most bikes used are light hard-tails, although the last World Cup was actually won on a full-suspension bike. The track is downhill and has dirt jumps, berms, and gaps. |

|||

Spain's motto {{Lang|la|[[Plus ultra]]}}, meaning "even further", or figuratively "Further!", is also Latin in origin.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.lamoncloa.gob.es/espana/simbolosdelestado/Paginas/index.aspx|title=La Moncloa. Símbolos del Estado|website=www.lamoncloa.gob.es|language=es|access-date=2019-09-30}}</ref> It is taken from the personal motto of [[Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor|Charles V]], Holy Roman Emperor and King of Spain (as Charles I), and is a reversal of the original phrase {{lang|la|Non terrae plus ultra}} ("No land further beyond", "No further!"). According to [[legend]], this phrase was inscribed as a warning on the [[Pillars of Hercules]], the rocks on both sides of the [[Strait of Gibraltar]] and the western end of the known, Mediterranean world. Charles adopted the motto following the discovery of the New World by Columbus, and it also has metaphorical suggestions of taking risks and striving for excellence. |

|||

Professionals in ''{{vanchor|gravity mountain biking}}'' tend to concentrate either on downhill mountain biking or 4X/dual slalom because they are very different. However, some riders, such as [[Cedric Gracia]], used to compete in both 4X and DH, although that is becoming more rare as 4X takes on its own identity. |

|||

In the United States the unofficial national motto until 1956 was ''[[E pluribus unum]]'' meaning "Out of many, one". The motto continues to be featured on the [[Great Seal of the United States|Great Seal]], it also appears on the flags and seals of both houses of congress and the flags of the states of Michigan, North Dakota, New York, and Wisconsin. The mottos 13 letters symbolically represent the original Thirteen Colonies which revolted from the British Crown. The motto is featured on all presently minted coinage and has been featured in most coinage throughout the nation's history. |

|||

===Freeride=== |

|||

{{Main|Freeride (mountain biking)}} |

|||

[[File:Free-ride.jpg|thumb|Freeride]] |

|||

Freeride / Big Hit / Hucking, as the name suggests, is a 'do anything' discipline that encompasses everything from downhill racing without the clock to jumping, riding 'North Shore' style (elevated trails made of interconnecting bridges and logs), and generally riding trails and/or stunts that require more skill and aggressive techniques than XC. |

|||

Several states of the United States [[list of U.S. state and territory mottos|have Latin mottos]], such as: |

|||

"Slopestyle" type riding is an increasingly popular genre that combines big-air, stunt-ridden freeride with BMX style tricks. Slopestyle courses are usually constructed at already established mountain bike parks and include jumps, large drops, quarter-pipes, and other wooden obstacles. There are always multiple lines through a course and riders compete for judges' points by choosing lines that highlight their particular skills. |

|||

* [[Arizona]]'s {{lang|la|Ditat deus}} ("God enriches"); |

|||

A "typical" freeride bike is hard to define, but typical specifications are 13-18 kilos (30-40 lbs) with {{convert|150|-|250|mm|in|abbr=off|sp=us}} of suspension front and rear. Freeride bikes are generally heavier and more amply suspended than their XC counterparts, but usually, retain much of their climbing ability. It is up to the rider to build his or her bike to lean more toward a preferred level of aggressiveness. |

|||

* [[Connecticut]]'s {{lang|la|Qui transtulit sustinet}} ("He who transplanted sustains"); |

|||

* [[Kansas]]'s {{lang|la|[[Per aspera ad astra|Ad astra per aspera]]}} ("Through hardships, to the stars"); |

|||

* [[Colorado]]'s {{lang|la|Nil sine numine}} ("Nothing without providence"); |

|||

* [[Michigan]]'s {{lang|la|Si quaeris peninsulam amoenam, circumspice}} ("If you seek a pleasant peninsula, look about you"), is based on that of Sir [[Christopher Wren]], in [[St. Paul's Cathedral]]; |

|||

* [[Missouri]]'s {{lang|la|[[Salus populi suprema lex esto]]}} ("The health of the people should be the highest law"); |

|||

* [[New York (state)]]'s {{lang|la|[[Coat of arms of New York|Excelsior]]}} ("Ever upward"); |

|||

* [[North Carolina]]'s {{lang|la|[[Esse Quam Videri]]}} ("To be rather than to seem"); |

|||

* [[South Carolina]]'s {{lang|la|[[Dum spiro spero]]}} ("While [still] breathing, I hope"); |

|||

* [[Virginia]]'s {{lang|la|[[Sic semper tyrannis]]}} ("Thus always to [[tyrant]]s"); and |

|||

* [[West Virginia]]'s {{lang|la|[[Montani Semper Liberi]]}} ("Mountaineers [are] always free"). |

|||

Many military organizations today have Latin mottos, such as: |

|||

===Dirt Jumping=== |

|||

{{Main|Dirt jumping}} |

|||

* {{lang|la|[[Semper Paratus]]}} ("always ready"), the motto of the [[United States Coast Guard]]; |

|||

Dirt Jumping (DJ) is the practice of riding bikes over shaped mounds of dirt or soil and becoming airborne. The goal is that after riding over the 'lip' the rider will become airborne, and aim to land on the 'knuckle'. Dirt jumping can be done on almost any bicycle, but the bikes chosen are generally smaller and more maneuverable hardtails so that tricks such as backflips, whips, and tabletops, are easier to complete. The bikes are simpler so that when a crash occurs there are fewer components to break or cause the rider injury. Bikes are typically built from sturdier materials such as steel to handle repeated heavy impacts of crashes and bails. |

|||

* {{lang|la|[[Semper Fidelis]]}} ("always faithful"), the motto of the [[United States Marine Corps]]; |

|||

* [[Semper supra]] ("always above"), the motto of the [[United States Space Force]]; |

|||

* {{lang|la|[[Per ardua ad astra]]}} ("Through adversity/struggle to the stars"), the motto of the [[Royal Air Force]] (RAF); and |

|||

* {{Lang|la|Vigilamus pro te}} ("We stand on guard for thee"), the motto of the [[Canadian Armed Forces]]. |

|||

A law governing body in the Philippines have a Latin motto, such as: |

|||

===Trials=== |

|||

{{Main|Mountain bike trials}} |

|||

* {{lang|la|Justitiae Pax Opus}} ("Justice, peace, work"), the motto of the [[Department of Justice (Philippines)]]; |

|||

Trials riding consists of hopping and jumping bikes over obstacles, without touching a foot onto the ground. It can be performed either off-road or in an urban environment. This requires an excellent sense of balance. The emphasis is placed on techniques of effectively overcoming the obstacles, although street-trials (as opposed to competition-oriented trials) is much like Street and DJ, where doing tricks with style is the essence. Trials bikes look almost nothing like mountain bikes. They use either 20″, 24″ or 26″ wheels and have very small, low frames, some types without a saddle. |

|||

Some colleges and universities have adopted Latin mottos, for example [[Harvard University]]'s motto is {{lang|la|[[Veritas]]}} ("truth"). Veritas was the goddess of truth, a daughter of Saturn, and the mother of Virtue. |

|||

===Urban/Street=== |

|||

{{Main|Freestyle BMX}} |

|||

==== Other modern uses ==== |

|||

Urban/Street is essentially the same as urban [[BMX]] (or Freestyle BMX), in which riders perform tricks by riding on/over man-made objects. The bikes are the same as those used for Dirt Jumping, having 24″ or 26″ wheels. Also, they are very light, many in the range of {{convert|25|-|30|lb|kg|abbr=on}}, and are typically hardtails with between 0-100 millimeters of the front suspension. As with Dirt Jumping and Trials, style and execution are emphasized. |

|||

Switzerland has adopted the country's Latin short name {{lang|la|[[Helvetia]]}} on coins and stamps, since there is no room to use all of the nation's [[Languages of Switzerland|four official languages]]. For a similar reason, it adopted the international vehicle and internet code ''CH'', which stands for {{lang|la|Confœderatio Helvetica}}, the country's full Latin name. |

|||

[[File:Rando VTT.jpg|thumb|Mountain bike trail riding (trail biking)]] |

|||

Some film and television in ancient settings, such as ''[[Sebastiane]]'', ''[[The Passion of the Christ]]'' and ''[[Barbarians (2020 TV series)]]'', have been made with dialogue in Latin for the sake of realism.<ref>In ''The Passion of the Christ'', arguably Romans would have spoke Greek especially in public settings in ancient Palestine, and certainly would not have had an Ecclesiastical, post Classical pronunciation of Latin</ref> Occasionally, Latin dialogue is used because of its association with religion or philosophy, in such film/television series as ''[[The Exorcist (film)|The Exorcist]]'' and ''[[Lost (2004 TV series)|Lost]]'' ("[[Jughead (Lost)|Jughead]]"). Subtitles are usually shown for the benefit of those who do not understand Latin. There are also [[list of songs with Latin lyrics|songs written with Latin lyrics]]. The libretto for the opera-oratorio {{lang|la|[[Oedipus rex (opera)|Oedipus rex]]}} by [[Igor Stravinsky]] is in Latin. |

|||

===Trail riding=== |

|||

{{Main|Trail riding#Mountain bike trails|l1=Trail riding: Mountain bike trails}} |

|||

The continued instruction of Latin is often seen as a highly valuable component of a liberal arts education. Latin is taught at many high schools, especially in Europe and the Americas. It is most common in British [[public school (United Kingdom)|public schools]] and grammar schools, the Italian {{lang|it|[[liceo classico]]}} and {{lang|it|[[liceo scientifico]]}}, the German {{lang|de|Humanistisches [[Gymnasium (Germany)|Gymnasium]]}} and the Dutch {{lang|nl|[[gymnasium (school)|gymnasium]]}}. |

|||

Trail riding or trail biking is a varied and popular non-competitive form of mountain biking on recognized, and often waymarked and graded, [[trail]]s; unpaved tracks, forest paths, etc. Trails may take the form of single routes or part of a larger complex, known as trail centers. Trail difficulty typically varies from gentle 'family' trails (green) through routes with increasingly technical features (blue and red) to those requiring high levels of fitness and skill (black) incorporating demanding ascents with steep technical descents comparable to less extreme downhill routes. As difficulty increases trails incorporate more technical trail features such as berms, rock gardens, uneven surfaces, drop offs and jumps. The most basic of bike designs can be used for less severe trails, but there are [[Mountain bike#Designs|"trail bike" designs]] which balance climbing ability with good downhill performance, almost always having 120-150 mm of travel on a suspension fork, with either a hard tail or a similar travel rear suspension. Many more technical trails are also used as routes for cross country, enduro, and even downhill racing. |

|||

[[File:QDP Ep 84 - De Ludo "Mysterium".webm|thumb|QDP Ep 84 – De Ludo "Mysterium": A Latin-language podcast from the US]] Occasionally, some media outlets, targeting enthusiasts, broadcast in Latin. Notable examples include [[Radio Bremen]] in Germany, [[YLE]] radio in Finland (the [[Nuntii Latini]] broadcast from 1989 until it was shut down in June 2019),<ref name=RTE2019-06-24a>{{cite news|url=https://www.rte.ie/news/world/2019/0624/1057298-latin/|title=Finnish broadcaster ends Latin news bulletins|publisher=[[RTÉ News]]|date=24 June 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190625001655/https://www.rte.ie/news/world/2019/0624/1057298-latin/|archive-date=25 June 2019|url-status=live}}</ref> and Vatican Radio & Television, all of which broadcast news segments and other material in Latin.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.radiobremen.de/nachrichten/latein/ |title=Latein: Nuntii Latini mensis lunii 2010: Lateinischer Monats rückblick |publisher=Radio Bremen |language=la |access-date=16 July 2010 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100618130408/https://www.radiobremen.de/nachrichten/latein/ |archive-date=18 June 2010}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|url=https://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/6079852.stm|title=Finland makes Latin the King|last=Dymond|first=Jonny|date=24 October 2006|work=[[BBC Online]]|access-date=29 January 2011|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110103171037/https://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/6079852.stm|archive-date=3 January 2011|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.yle.fi/radio1/tiede/nuntii_latini/ |title=Nuntii Latini |publisher=YLE Radio 1 |language=la |access-date=17 July 2010 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100718065851/https://www.yle.fi/radio1/tiede/nuntii_latini/ |archive-date=18 July 2010 |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

===Marathon=== |

|||

Mountain Bike Touring or Marathon is long-distance touring on dirt roads and single track with a mountain bike. |

|||

A variety of organisations, as well as informal Latin 'circuli' ('circles'), have been founded in more recent times to support the use of spoken Latin.<ref>{{Cite web|date=13 September 2015|title=About us (English)|url=https://www.circuluslatinuslondiniensis.co.uk/in-english/|access-date=2021-06-29|website=Circulus Latínus Londiniénsis|language=la|archive-date=10 February 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230210114430/https://www.circuluslatinuslondiniensis.co.uk/in-english/|url-status=dead}}</ref> Moreover, a number of university classics departments have begun incorporating communicative pedagogies in their Latin courses. These include the University of Kentucky, the University of Oxford and also Princeton University.<ref>{{Cite web|title=Active Latin at Jesus College – Oxford Latinitas Project|url=https://oxfordlatinitas.org/2020/12/01/active-latin-at-jesus-college/|access-date=2021-06-29|language=en-GB}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|title=Graduate Certificate in Latin Studies – Institute for Latin Studies {{!}} Modern & Classical Languages, Literatures & Cultures|url=https://mcl.as.uky.edu/latin-institute|access-date=2021-06-29|website=mcl.as.uky.edu}}</ref> |

|||

With the popularity of the [[Great Divide Trail]], the [[Colorado Trail]] and other long-distance off-road biking trails, specially outfitted mountain bikes are increasingly being used for touring. Bike manufacturers like Salsa have even developed MTB touring bikes like the Fargo model. |

|||

There are many websites and forums maintained in Latin by enthusiasts. The [[Latin Wikipedia]] has more than 130,000 articles. |

|||

[[Mixed Terrain Cycle-Touring]] or rough riding is a form of mountain-bike touring but involves cycling over a variety of surfaces and topography on a single route, with a single bicycle that is expected to be satisfactory for all segments. The recent surge in popularity of mixed-terrain touring is in part a reaction against the increasing specialization of the bicycle industry. Mixed-terrain bicycle travel has a storied history of focusing on efficiency, cost-effectiveness, and freedom of travel over varied surfaces.<ref>[https://www.adventurecycling.org/resources/blog/10-things-you-might-think-you-need-for-a-long-distance-tour-but-dont/ Ten Things You Might Think You Need for a Long-Distance Tour, but Don't.] Blog of Adventure Cycling Association, April 10, 2012.</ref> |

|||

[[Urdaneta, Pangasinan|Urdaneta City]]'s motto {{lang|la|Deo servire populo sufficere}} ("It is enough for the people to serve God") the Latin motto can be read in the old seal of this Philippine city. |

|||

=== Bikepacking === |

|||

Bikepacking is a self-supported style of lightly loaded single or multiple night mountain biking.<ref name=":0">{{Cite news|url=https://www.rei.com/learn/expert-advice/bikepacking.html|title=How to Get Started Bikepacking|website=REI|language=en-US|access-date=2018-03-22}}</ref> Bikepacking is similar to bike touring, however the two sports generally use different bikes and the main difference is the method of carrying gear. Bikepacking generally involves carrying less gear and using smaller frame bags while bike touring will use [[pannier]]s.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.cyclinguk.org/article/whats-difference-between-cycle-touring-and-bikepacking|title=What's the difference between cycle touring and bikepacking? {{!}} Cycling UK|website=www.cyclinguk.org|language=en|access-date=2018-03-22}}</ref> |

|||

==Legacy== |

|||