Internationalism (politics)

| Part of the Politics series |

| Basic forms of government |

|---|

| List of countries by system of government |

|

|

| Part of the Politics series |

| Party politics |

|---|

|

|

Internationalism is a political principle that advocates greater political or economic cooperation among states and nations.[1] It is associated with other political movements and ideologies, but can also reflect a doctrine, belief system, or movement in itself.[2]

Supporters of internationalism are known as internationalists and generally believe that humans should unite across national, political, cultural, racial, or class boundaries to advance their common interests, or that governments should cooperate because their mutual long-term interests are of greater importance than their short-term disputes.[3]

Internationalism has several interpretations and meanings, but is usually characterized by opposition to nationalism and isolationism; support for international institutions, such as the United Nations; and a cosmopolitan outlook that promotes and respects other cultures and customs.[2]

The term is similar to, but distinct from, globalism and cosmopolitanism.

Origins

| Part of a series on |

| Liberalism |

|---|

|

In 19th-century Great Britain, there was a liberal internationalist strand of political thought epitomized by Richard Cobden and John Bright. Cobden and Bright were against the protectionist Corn Laws and in a speech at Covent Garden on September 28, 1843, Cobden outlined his utopian brand of internationalism:

Free Trade! What is it? Why, breaking down the barriers that separate nations; those barriers behind which nestle the feelings of pride, revenge, hatred and jealously, which every now and then burst their bounds and deluge whole countries with blood.[4]

Cobden believed that Free Trade would pacify the world by interdependence, an idea also expressed by Adam Smith in his The Wealth of Nations and common to many liberals of the time. A belief in the idea of the moral law and an inherent goodness in human nature also inspired their faith in internationalism.

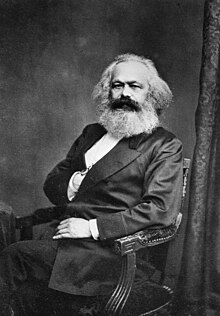

Those liberal conceptions of internationalism were harshly criticized by socialists and radicals at the time, who pointed out the links between global economic competition and imperialism, and would identify this competition as being a root cause of world conflict. One of the first international organisations in the world was the International Workingmen's Association, formed in London in 1864 by working class socialist and communist political activists (including Karl Marx). Referred to as the First International, the organization was dedicated to the advancement of working class political interests across national boundaries, and was in direct ideological opposition to strains of liberal internationalism which advocated free trade and capitalism as means of achieving world peace and interdependence.

Other international organizations included the Inter-Parliamentary Union, established in 1889 by Frédéric Passy from France and William Randal Cremer from the United Kingdom, and the League of Nations, which was formed after World War I. The former was envisioned as a permanent forum for political multilateral negotiations, while the latter was an attempt to solve the world's security problems through international arbitration and dialogue.

J. A. Hobson, a Gladstonian liberal who became a socialist after the Great War, anticipated in his book Imperialism (1902) the growth of international courts and congresses which would hopefully settle international disputes between nations in a peaceful way. Sir Norman Angell in his work The Great Illusion (1910) claimed that the world was united by trade, finance, industry and communications and that therefore nationalism was an anachronism and that war would not profit anyone involved but would only result in destruction.

Lord Lothian was an internationalist and an imperialist who in December 1914 looked forward to "the voluntary federation of the free civilised nations which will eventually exorcise the spectre of competitive armaments and give lasting peace to mankind."[5]

In September 1915, he thought the British Empire was "the perfect example of the eventual world Commonwealth."[6]

Internationalism expressed itself in Britain through the endorsement of the League of Nations by such people as Gilbert Murray. The Liberal Party and the Labour Party had prominent internationalist members, like the Labour Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald who believed that 'our true nationality is mankind'[7]

Socialism

| Part of a series on |

| Socialism |

|---|

|

Internationalism is an important component of socialist political theory,[8][9] based on the principle that working-class people of all countries must unite across national boundaries and actively oppose nationalism and war in order to overthrow capitalism[10] (see entry on proletarian internationalism). In this sense, the socialist understanding of internationalism is closely related to the concept of international solidarity.

Socialist thinkers such as Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, and Vladimir Lenin argue that economic class, rather than (or interrelated with) nationality, race, or culture, is the main force which divides people in society, and that nationalist ideology is a propaganda tool of a society's dominant economic class. From this perspective, it is in the ruling class' interest to promote nationalism in order to hide the inherent class conflicts at play within a given society (such as the exploitation of workers by capitalists for profit). Therefore, socialists see nationalism as a form of ideological control arising from a society's given mode of economic production (see dominant ideology).

Since the 19th century, socialist political organizations and radical trade unions such as the Industrial Workers of the World have promoted internationalist ideologies and sought to organize workers across national boundaries to achieve improvements in the conditions of labor and advance various forms of industrial democracy. The First, Second, Third, and Fourth Internationals were socialist political groupings which sought to advance worker's revolution across the globe and achieve international socialism (see world revolution).

Socialist internationalism is anti-imperialist, and therefore supports the liberation of peoples from all forms of colonialism and foreign domination, and the right of nations to self-determination. Therefore, socialists have often aligned themselves politically with anti-colonial independence movements, and actively opposed the exploitation of one country by another.[11]

Since war is understood in socialist theory to be a general product of the laws of economic competition inherent to capitalism (i.e., competition between capitalists and their respective national governments for natural resources and economic dominance), liberal ideologies which promote international capitalism and "free trade", even if they sometimes speak in positive terms of international cooperation, are, from the socialist standpoint, rooted in the very economic forces which drive world conflict. In socialist theory, world peace can only come once economic competition has been ended and class divisions within society have ceased to exist. This idea was expressed in 1848 by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels in The Communist Manifesto:

In proportion as the exploitation of one individual by another will also be put an end to, the exploitation of one nation by another will also be put an end to. In proportion as the antagonism between classes within the nation vanishes, the hostility of one nation to another will come to an end.[12]

The idea was reiterated later by Lenin and advanced as the official policy of the Bolshevik party during World War I:

Socialists have always condemned war between nations as barbarous and brutal. But our attitude towards war is fundamentally different from that of the bourgeois pacifists (supporters and advocates of peace) and of the Anarchists. We differ from the former in that we understand the inevitable connection between wars and the class struggle within the country; we understand that war cannot be abolished unless classes are abolished and Socialism is created.[13]

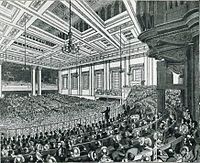

International Workingmen's Association

The International Workingmen's Association, or First International, was an organization founded in 1864, composed of various working class radicals and trade unionists who promoted an ideology of internationalist socialism and anti-imperialism. Figures such as Karl Marx and anarchist revolutionary Mikhail Bakunin would play prominent roles in the First International. The Inaugural Address of the First International, written by Marx in October 1864 and distributed as a pamphlet, contained calls for international cooperation between working people, and condemnations of the imperialist policies of national aggression undertaken by the governments of Europe:

If the emancipation of the working classes requires their fraternal concurrence, how are they to fulfill that great mission with a foreign policy in pursuit of criminal designs, playing upon national prejudices, and squandering in piratical wars the people’s blood and treasure?[14]

By the mid-1870s, splits within the International over tactical and ideological questions would lead to the organization's demise and pave the way for the formation of the Second International in 1889. One faction, with Marx as the figurehead, argued that workers and radicals must work within parliaments in order to win political supremacy and create a worker's government. The other major faction were the anarchists, led by Bakunin, who saw all state institutions as inherently oppressive, and thus opposed any parliamentary activity and believed that workers action should be aimed at the total destruction of the state.

Socialist International

The Socialist International, known as the Second International, was founded in 1889 after the disintegration of the International Workingmen's Association. Unlike the First International, it was a federation of socialist political parties from various countries, including both reformist and revolutionary groupings. The parties of the Second International were the first socialist parties to win mass support among the working class and have representatives elected to parliaments. These parties, such as the German Social-Democratic Labor Party, were the first socialist parties in history to emerge as serious political players on the parliamentary stage, often gaining millions of members.

Ostensibly committed to peace and anti-imperialism, the International Socialist Congress held its final meeting in Basel, Switzerland in 1912, in anticipation of the outbreak of World War I. The manifesto adopted at the Congress outlined the Second International's opposition to the war and its commitment to a speedy and peaceful resolution:

If a war threatens to break out, it is the duty of the working classes and their parliamentary representatives in the countries involved supported by the coordinating activity of the International Socialist Bureau to exert every effort in order to prevent the outbreak of war by the means they consider most effective, which naturally vary according to the sharpening of the class struggle and the sharpening of the general political situation. In case war should break out anyway it is their duty to intervene in favor of its speedy termination and with all their powers to utilize the economic and political crisis created by the war to arouse the people and thereby to hasten the downfall of capitalist class rule.[15]

Despite this, when the war began in 1914, the majority of the Socialist parties of the International turned on each other and sided with their respective governments in the war effort, betraying their internationalist values and leading to the dissolution of the Second International. This betrayal led the few anti-war delegates left within the Second International to organize the International Socialist Conference at Zimmerwald, Switzerland in 1915. Known as the Zimmerwald Conference, its purpose was to formulate a platform of opposition to the war. The conference was unable to reach agreement on all points, but ultimately was able to publish the Zimmerwald Manifesto, which was drafted by Leon Trotsky. The most left-wing and stringently internationalist delegates at the conference were organized around Lenin and the Russian Social Democrats, and known as the Zimmerwald Left. They bitterly condemned the war and what they described as the hypocritical "social-chauvinists" of the Second International, who so quickly abandoned their internationalist principles and refused to oppose the war. The Zimmerwald Left resolutions urged all socialists who were committed to the internationalist principles of socialism to struggle against the war and commit to international workers' revolution.[16]

The perceived betrayal of the social-democrats and the organization of the Zimmerwald Left would ultimately set the stage for the emergence of the world's first modern communist parties and the formation of the Third International in 1919.[17]

Communist International

The Communist International, also known as the Comintern or the Third International, was formed in 1919 in the wake of the Russian Revolution, the end of the first World War, and the dissolution of the Second International. It was an association of communist political parties from throughout the world dedicated to proletarian internationalism and the revolutionary overthrow of the world bourgeoisie. The Manifesto of the Communist International, written by Leon Trotsky, describes the political orientation of the Comintern as "against imperialist barbarism, against monarchy, against the privileged estates, against the bourgeois state and bourgeois property, against all kinds and forms of class or national oppression".[18]

Fourth International

The fourth and last socialist international was founded by Leon Trotsky and his followers in 1938 in opposition to the Third International and the direction taken by the USSR under the leadership of Joseph Stalin. The Fourth International declared itself to be the true ideological successor of the original Comintern under Lenin, carrying on the banner of proletarian internationalism which had been abandoned by Stalin's Comintern. A variety of still active left-wing political organizations claim to be the contemporary successors of Trotsky's original Fourth International.

Internationalism in practise

The 4th World Congress of the Communist International established the legal framework for internationalist collaboration and the foundation of agricultural and industrial communes within the USSR. Up until World War II, between seventy to eighty thousand internationalist-minded workers moved to the Soviet Union from abroad.[19] The call for internationalist solidarity attracted settlers from countries such as Austria, Czechoslovakia, Denmark, Estonia, Germany, Italy, Sweden, Uruguay and the United States.[20] One of first communes was formed by 123 workers of the Ford Motor Company’s Highland Park factory.[21] Led by the Detroit-based engineer Arthur Adams (1885–1969) the cooperative arrived in 1921 to set up the first automobile plant of the USSR (Likhachev Plant) in the vicinity of Moscow.[22] While most communes were short-lived and disbanded by 1927, others such as Interhelpo, an internationalist commune founded 1923 by Ido-speakers in Czechoslovakia, played an important role in the industrialization and urbanization of Soviet Central Asia.[23] By 1932, the Frunze-based cooperative comprised members from 14 different ethnicities who had developed an organic pathwork working language referred to as "spontánne esperanto".[24] Being a product of the New Economic Policy, after Stalin's Great Break most internationalist communes operating in the USSR were either shut down or collectivized.[25]

Modern expression

Internationalism is most commonly expressed as an appreciation for the diverse cultures in the world, and a desire for world peace. People who express this view believe in not only being a citizen of their respective countries, but of being a citizen of the world. Internationalists feel obliged to assist the world through leadership and charity.

Internationalists also advocate the presence of international organizations, such as the United Nations, and often support a stronger form of a world government.

Contributors to the current version of internationalism include Albert Einstein, who was a socialist and believed in a world government, and classified the follies of nationalism as "an infantile sickness".[26] Conversely, other internationalists such as Christian Lange[27] and Rebecca West[28] saw little conflict between holding nationalist and internationalist positions.

International organizations and internationalism

For both intergovernmental organizations and international non-governmental organizations to emerge, nations and peoples had to be strongly aware that they shared certain interests and objectives across national boundaries and they could best solve their many problems by pooling their resources and effecting transnational cooperation, rather than through individual countries' unilateral efforts. Such a view, such global consciousness, may be termed internationalism, the idea that nations and peoples should cooperate instead of preoccupying themselves with their respective national interests or pursuing uncoordinated approaches to promote them.[29]

Sovereign states vs. supranational powers balance

In the strict meaning of the word, internationalism is still based on the existence of sovereign state. Its aims are to encourage multilateralism (world leadership not held by any single country) and create some formal and informal interdependence between countries, with some limited supranational powers given to international organisations controlled by those nations via intergovernmental treaties and institutions.

The ideal of many internationalists, among them world citizens, is to go a step further towards democratic globalization by creating a world government. However, this idea is opposed and/or thwarted by other internationalists, who believe any world government body would be inherently too powerful to be trusted, or because they dislike the path taken by supranational entities such as the United Nations or a union of states such as the European Union and fear that a world government inclined towards fascism would emerge from the former. These internationalists are more likely to support a loose world federation in which most power resides with national governments or sub-national governments.

Literature and criticism

In Jacques Derrida's 1993 work, Specters of Marx: The State of the Debt, the Work of Mourning and the New International, he uses Shakespeare's Hamlet to frame a discussion of the history of the International, ultimately proposing his own vision for a "New International" that is less reliant on large-scale international organizations.[30] As he puts it, the New International should be "without status ... without coordination, without party, without country, without national community, without co-citizenship, without common belonging to a class."

Through Derrida's use of Hamlet, he shows the influence that Shakespeare had on Marx and Engel's work on internationalism. In his essay, "Big Leagues: Specters of Milton and Republican International Justice between Shakespeare and Marx", Christopher N. Warren makes the case that English poet John Milton also had a substantial influence on Marx and Engel's work.[31] Paradise Lost, in particular, shows “the possibility of political actions oriented toward international justice founded outside the aristocratic order.”[32] Marx and Engels, Warren claims, understood the empowering potential of Miltonic republican traditions for forging international coalitions—a lesson, perhaps, for “The New International.”

Other uses

- In a less restricted sense, internationalism is a word describing the impetus and motivation for the creation of any international organizations. The earliest such example of broad internationalism would be the drive to replace feudal systems of measurement with the metric system, long before the creation of international organizations like the World Court, the League of Nations and the United Nations.

- In linguistics, an internationalism is a loanword that, originating in one language, has been borrowed by most other languages. Examples of such borrowings include OK, microscope and tokamak.

See also

- Anti-globalization movement

- Anti-imperialism

- Bahá'í International Community

- Communist International

- Cosmopolitanism

- Cross-culturalism

- Democratic globalization

- Fourth International

- Global Citizens Movement

- Global justice

- Global village

- Globalisation

- International community

- International Workingmen's Association

- "Yank" Levy

- Multilateralism

- Neoconservatism

- New Internationalist

- Pan-Islamism

- Second International

- Transnationalism

- World communism

- World community

References

- ^ "Internationalism is... described as the theory and practice of transnational or global cooperation. As a political ideal, it is based on the belief that nationalism should be transcended because the ties that bind people of different nations are stronger than those that separate them." N. D. Arora, Political Science, McGraw-Hill Education. ISBN 0-07-107478-3, (p.2).

- ^ a b Warren F. Kuehl, Concepts of Internationalism in History, July 1986.

- ^ Fred Halliday, Three concepts of internationalism, International Affairs, Volume 64, Issue 2, Spring 1988, Pages 187–198.

- ^ "Peace and Free Trade".

- ^ J.R.M. Butler, Lord Lothian 1882-1940 (Macmillan, 1960), p. 56.

- ^ J.R.M. Butler, Lord Lothian 1882-1940 (Macmillan, 1960), p. 57.

- ^ Lord Vansittart, The Mist Procession, p. 373

- ^ "Internationalism is the bedrock of socialism, not simply or mainly for sentimental reasons but because capitalism has created a world economy that can be transformed only on a world scale." - Duncan Hallas. The Comintern: "Introduction to the 1985 Edition". Bookmarks. 1985.

- ^ "The international character of the socialist revolution [...] flows from the present state of the economy and the social structure of humanity. Internationalism is no abstract principle but a theoretical and political reflection of the character of world economy, of the world development of productive forces, and of the world scale of the class struggle." - Leon Trotsky.The Permanent Revolution. 1931.

- ^ "The Communists are further reproached with desiring to abolish countries and nationality. The working men have no country. We cannot take from them what they have not got.... United [worker's] action, of the leading civilized countries at least, is one of the first conditions for the emancipation of the proletariat." - Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. The Communist Manifesto. Chapter 2: Proletarians and Communists

- ^ "National self-determination is the same as the struggle for complete national liberation, for complete independence, against annexation, and socialists cannot—without ceasing to be socialists—reject such a struggle in whatever form, right down to an uprising or war." - V.I. Lenin. A Caricature of Marxism and Imperialist Economism. 1916. Marxists Internet Archive.

- ^ Marx, Karl; Engels, Friedrich. "The Communist Manifesto: Proletarians and Communists". Marxists Internet Archive.

- ^ Lenin, V.I. (1915). "Socialism and War". Marxists Internet Archive.

- ^ "If the emancipation of the working classes requires their fraternal concurrence, how are they to fulfill that great mission with a foreign policy in pursuit of criminal designs, playing upon national prejudices, and squandering in piratical wars the people’s blood and treasure? It was not the wisdom of the ruling classes, but the heroic resistance to their criminal folly by the working classes of England, that saved the west of Europe from plunging headlong into an infamous crusade for the perpetuation and propagation of slavery on the other side of the Atlantic. The shameless approval, mock sympathy, or idiotic indifference with which the upper classes of Europe have witnessed the mountain fortress of the Caucasus falling a prey to, and heroic Poland being assassinated by, Russia: the immense and unresisted encroachments of that barbarous power, whose head is in St. Petersburg, and whose hands are in every cabinet of Europe, have taught the working classes the duty to master themselves the mysteries of international politics; to watch the diplomatic acts of their respective governments; to counteract them, if necessary, by all means in their power; when unable to prevent, to combine in simultaneous denunciations, and to vindicate the simple laws or morals and justice, which ought to govern the relations of private individuals, as the rules paramount of the intercourse of nations. The fight for such a foreign policy forms part of the general struggle for the emancipation of the working classes." - Karl Marx. Inaugural Address of the International Workingmen's Association. 1864

- ^ Manifesto of the International Socialist Congress at Basel. 1912. https://www.marxists.org/history/international/social-democracy/1912/basel-manifesto.htm

- ^ International Socialist Conference at Zimmerwald. https://www.marxists.org/history/international/social-democracy/zimmerwald/index.htm

- ^ The Zimmerwald Left. https://www.marxists.org/glossary/orgs/z/i.htm#zimmerwald-left

- ^ "Leon Trotsky: First 5 Years of the Comintern: Vol.1 (Manifesto of the Communist International)".

- ^ Graziosi, Andrea (2000). A new, peculiar state : explorations in Soviet history, 1917-1937. Westport, CT: Praeger. pp. 223–256. ISBN 0-275-96650-X. OCLC 42708002.

- ^ Pollák, Pavel (1969). ""Die Auswanderung in Die Sowjetunion in Den Zwanziger Jahren"". Bohemia. 10: 298–300.

- ^ Siegelbaum, Lewis H. (2008). Cars for comrades : the life of the Soviet automobile. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-8014-6100-2. OCLC 732957072.

- ^ Siegelbaum, Lewis H. (2008). Cars for comrades : the life of the Soviet automobile. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-8014-6100-2. OCLC 732957072.

- ^ Leupold, David (2021). "'Building the Internationalist City from Below': The Role of the Czechoslovak Industrial Cooperative "Interhelpo" in Forging Urbanity in early-Soviet Bishkek". International Labor and Working-Class History. 100: 27. doi:10.1017/S0147547920000228. ISSN 0147-5479.

- ^ Pollák, Pavel (1961). Internacionálná pomoc československého proletariátu národom SSSR : dejiny československého robotníckeho družstva Interhelpo v sovietskej Kirgízii. Bratislava: Slovenská Akadémia Vied. p. 206.

- ^ Bernstein, Seth; Cherny, Robert (2014). "Searching for the Soviet Dream: Prosperity and Disillusionment on the Soviet Seattle Agricultural Commune, 1922–1927". Agricultural History. 88 (1): 25. doi:10.3098/ah.2014.88.1.22. ISSN 0002-1482. JSTOR 10.3098/ah.2014.88.1.22.

- ^ Albert Einstein, The World as I See It, 1934

- ^ "Internationalism . . . recognizes, by its very name, that nations do exist. It simply limits their scope more than one-sided nationalism does." Lange quoted in Jay Nordlinger, Peace They Say: A History of the Nobel Peace Prize, the Most Famous and Controversial Prize in the World. Encounter Books, 2013. ISBN 1-59403-599-7 (p. 111).

- ^ "The European tradition...from the very beginning has recognised the nationalism and internationalism are not irreconcible opposities but counterbalances that can keep the nations in equilibrium". Rebecca West, "The Necessity and Grandeur of the International Ideal", 1935. Reprinted in Patrick Deane, History in Our Hands: a critical anthology of writings on literature, culture, and politics from the 1930s. London ; Leicester University Press, 1998. ISBN 978-0-7185-0143-3, p. 76.

- ^ Iriye, Akira (2002). Global Community. London: University of California Press. pp. 9, 10.

- ^ Derrida, Jacques. Specters of Marx, the state of the debt, the Work of Mourning, & the New International, translated by Peggy Kamuf, Routledge, 1994.

- ^ Warren, Christopher N (2016). “Big Leagues: Specters of Milton and Republican International Justice between Shakespeare and Marx.” Humanity: An International Journal of Human Rights, Humanitarianism, and Development, Vol. 7.

- ^ Warren, Christopher N (2016). “Big Leagues: Specters of Milton and Republican International Justice between Shakespeare and Marx.” Humanity: An International Journal of Human Rights, Humanitarianism, and Development, Vol. 7. Pg. 380.

Further reading

- Ankerl, Guy (2000). Global communication without universal civilization. INU societal research. Vol. 1: Coexisting contemporary civilizations : Arabo-Muslim, Bharati, Chinese, and Western. Geneva: INU Press. ISBN 978-2-88155-004-1.

- Derrida, Jacque (1993). Specters of Marx: The State of the Debt, the Work of Mourning and the New International. ISBN 978-0415389570.

- Hallas, Duncan (2008). The Comintern: A History of the Third International. Chicago, IL: Haymarket Books. ISBN 978-1-931859-51-6.

- Warren, Christopher (2016). “Big Leagues: Specters of Milton and Republican International Justice between Shakespeare and Marx.” Humanity: An International Journal of Human Rights, Humanitarianism, and Development, Vol. 7.