Naples: Difference between revisions

Theirrulez (talk | contribs) image added |

Revert to revision 428176062 dated 2011-05-09 01:54:42 by 130.156.132.79 using popups |

||

| Line 129: | Line 129: | ||

==Main sights== |

==Main sights== |

||

{{wide image|NapoliDaPosillipo.jpg|1100px|alt=Panorama of Naples from Posillipo|Panorama of city from [[Posillipo]].}} |

|||

:''See also, [[:Category:Buildings and structures in Naples|Buildings and structures in Naples]]'' |

:''See also, [[:Category:Buildings and structures in Naples|Buildings and structures in Naples]]'' |

||

Naples has one of the greatest density of cultural resources and monuments that include 2800 years of history (castles, fountains, churches, ancient architecture, etc.): the most prominent forms of architecture in Naples are from the [[Medieval architecture|Medieval]], [[Renaissance architecture|Renaissance]] and [[Baroque architecture|Baroque]] periods.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.inaples.it/eng/pianta_stratificata.htm|publisher=INaples.it|title= historical centre |date=7 October 2007}}</ref> The historic centre of Naples is typically the most fruitful for architecture and is in fact listed by [[UNESCO]] as a [[World Heritage Site]].<ref name = "unesco"/> A striking feature of Naples is the fact that it has 448 historical churches, making it one of the most [[Roman Catholic Church|Catholic]] cities in the world.<ref name = "churches"/> |

Naples has one of the greatest density of cultural resources and monuments that include 2800 years of history (castles, fountains, churches, ancient architecture, etc.): the most prominent forms of architecture in Naples are from the [[Medieval architecture|Medieval]], [[Renaissance architecture|Renaissance]] and [[Baroque architecture|Baroque]] periods.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.inaples.it/eng/pianta_stratificata.htm|publisher=INaples.it|title= historical centre |date=7 October 2007}}</ref> The historic centre of Naples is typically the most fruitful for architecture and is in fact listed by [[UNESCO]] as a [[World Heritage Site]].<ref name = "unesco"/> A striking feature of Naples is the fact that it has 448 historical churches, making it one of the most [[Roman Catholic Church|Catholic]] cities in the world.<ref name = "churches"/> |

||

Revision as of 17:27, 11 May 2011

Naples

Napoli | |

|---|---|

| Comune di Napoli | |

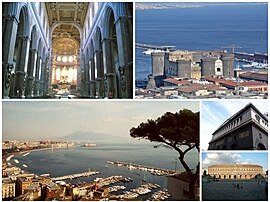

A collage of Naples: in the top left is the interior of Naples Cathedral, followed by the Castello Nuovo, a view of the city harbour and the Teatro San Carlo. | |

| Country | Italy |

| Region | Campania |

| Province | Naples (NA) |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Rosa Russo Iervolino (Democratic Party) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 117.27 km2 (45.28 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 17 m (56 ft) |

| Population (30 September 2009)[2] | |

| • Total | 963,357 |

| • Density | 8,200/km2 (21,000/sq mi) |

| Demonym | Napoletani |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 80100, 80121-80147 |

| Dialing code | 081 |

| Patron saint | Januarius |

| Saint day | September 19 |

| Website | Official website |

Naples (Italian: Napoli , pronounced [ˈnaːpoli], Neapolitan: Napule) is a city in Southern Italy; it is the capital of the region of Campania and of the province of Naples. Known for its rich history, art, culture, architecture, music, and gastronomy, Naples has played an important role in the Italian peninsula and beyond[3] for much of its existence, which began more than 2,800 years ago. Situated on the west coast of Italy by the Gulf of Naples, the city is located halfway between two volcanic areas, Mount Vesuvius and the Phlegraean Fields.

Founded in the 9th-8th century BC[4][5] as a Greek colony, which was originally named Παρθενόπη Parthenope and later Νεάπολις Neápolis (Greek for New City), Naples is one of the oldest cities in the world. It was among the foremost cities of Magna Graecia, playing a key role in the transmission of Greek culture to Roman society. Naples eventually became part of the Roman Republic as a major cultural center; the premiere Latin poet, Virgil, received part of his education there and later resided in its environs.[6] As a microcosm of European history, Naples has seen several civilizations come and go, each leaving traces in its art and architecture. The most prominent forms of architecture now visible derive from the Medieval, Renaissance, and Baroque periods.

The historic city centre of Naples is the largest in Europe[7] (1,700 hectares),[8] and is listed by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site. Over its rich history Naples has been the capital of duchies, kingdoms, and one Empire, as well as a major cultural center (especially during the period of Renaissance humanism and in the 17th through 19th centuries). The city has profoundly influenced many areas of Europe and beyond.[9] In the immediate vicinity of Naples are various sites (e.g., the Palace of Caserta, Pompeii, and Herculaneum) that are strongly related to the city for historical, artistic, architectural reasons.

Naples was preeminently the capital city of a kingdom that bore its name from 1282 until 1816: the Kingdom of Naples. Then, in union with Sicily, it became the capital of the Two Sicilies until the unification of Italy in 1861. Through the Neapolitan War, Naples strongly promoted Italian unification.

Within its administrative limits, Naples has a population of around 1 million people, but according to different sources its metropolitan area is either the second (after the Milan metropolitan area, with 4,434,136 inhabitants according to Svimez Data[10] or 4,996,084 according to Censis institute)[11] or third (3.1 million inhabitants according to OECD)[12] most populated metropolitan area in Italy. In addition, it is the most densely populated major city in Italy.

For economic strength, Naples is ranked fourth in Italy, after Milan, Rome and Turin. It is the world's 91st richest city by purchasing power, with a GDP of $43 billion, surpassing the economies of Budapest and Zurich.[13] The port of Naples is one of the most important in Europe (the second in the world after the port of Hong Kong for passenger flow).[14] Even though the city has experienced remarkable economic growth in recent times, and unemployment levels in the city and surrounding Campania have decreased since 1999,[15] Naples is still characterized by political and economic corruption[16] and a thriving black market empire. Italian mega-companies, such as MSC, are headquartered in the city. Since 1958, the city hosts the Center Rai of Naples (media), while in the Bagnoli district there is a big NATO base. The city hosts the SRM institution for economic research and the OPE company and study center.[17][18][19] Naples is a full member of the Eurocities network of European cities.[20] The city was selected to become the headquarters of the European institution Acp/Ue [21] and as a City of Literature by UNESCO's Creative Cities Network.[22] In the Posillipo district there is Villa Rosebery, one of three official residences of the President of Italy.

Naples was the most bombed Italian city of World War II.[23] In the 20th century, first under Fascism and reconstruction following the Second World War built much of the periphery. In recent decades, Naples has adopted a business district (the Centro Direzionale) with skyscrapers and infrastructure such as the TGV in Rome or in a subway expansion: it will include half of the region. The metropolis will host the IAC 2012[24] and the Universal Forum of Cultures 2013.

The city is also synonymous with pizza, which originated in the city, with the first pizzas originally fried and later baked in the oven. A strong part of Neapolitan culture which has had wide reaching effects is music, including the invention of the romantic guitar and the mandolin as well as strong contributions to opera and folk standards. There are popular characters and figures who have come to symbolise Naples; these include the patron saint of the city Januarius, Pulcinella, and the Sirens from the epic Greek poem the Odyssey.

History

Greek birth, Roman acquisition

Founded in the 6th century BC, somewhat late in the scheme of Magna Graecia,[26][27], which was originally named Παρθενόπη Parthenope and later Νεάπολις Neápolis (Greek for New City), Naples is one of the oldest cities in the world. It was among the foremost cities of Magna Graecia, playing a key role in the transmission of Greek culture to Roman society. Naples eventually became part of the Roman Republic as a major cultural center; the premiere Latin poet, Virgil, received part of his education there and later resided in its environs.[28] As a microcosm of European history, Naples has seen several civilizations come and go, each leaving traces in its art and architecture. The most prominent forms of architecture now visible derive from the Medieval, Renaissance, and Baroque periods.

The new city grew thanks to the influence of powerful Greek city-state Siracusa and at some point the new and old cities on the Gulf of Naples merged together to become one.[29] The city became an ally of the Roman Republic against Carthage; the strong walls surrounding Neapolis stopped invader Hannibal from entering.[30] During the Samnite Wars, the city, now a bustling centre of trade, was captured by the Samnites[31]; however, the Romans soon took it from them and made Neapolis a Roman colony.[30]

The city was greatly respected by the Romans as a place of Hellenistic culture: the people maintained their Greek language and customs; elegant villas, aqueducts, public baths, an odeon, a theatre and the Temple of Dioscures were built, and many powerful emperors chose to holiday in the city including Claudius and Tiberius.[30]

It was during this period that Christianity came to Naples; apostles St. Peter and St. Paul are said to have preached in the city. Also, St. Januarius, who would become Naples' patron saint, was martyred there.[32] Last emperor of Western Roman Empire, Romulus Augustulus, was sent in exile in Naples by king Odoacer.

Duchy of Naples

Following the decline of the Western Roman Empire, Naples was captured by the Ostrogoths, a Germanic people, and incorporated into the Ostrogothic Kingdom.[33] However, Belisarius of the Byzantine Empire (also known as the Eastern Roman Empire) took the city back in 536, after famously entering the city via the aqueduct.[34]

The Gothic Wars waged on, and Totila briefly took the city for the Ostrogoths in 543, before, finally, the Battle of Mons Lactarius on the slopes of Vesuvius decided Byzantine rule.[33] Naples was expected to keep in contact with the Exarchate of Ravenna, which was the centre of Byzantine power on the Italian peninsula.[35]

After the exarchate fell a Duchy of Naples was created; though Naples continued with its Greco-Roman culture, it eventually switched allegiance under Duke Stephen II to Rome rather than Constantinople, putting it under papal suzerainty by 763.[35]

The years between 818 and 832 were a particularly confusing period in regard to Naples' relation with the Byzantine Emperor, with feuding between local pretenders to the ducal throne.[36] Theoctistus was appointed without imperial approval; this was later revoked and Theodore II took his place. However, the general populance chased him from the city and instead elected Stephen III, a man who minted coins with his own initials not that of the Byzantine Emperor. Naples gained complete independence by 840.[36]

The duchy was under direct control of Lombards for a brief period, after the capture by Pandulf IV of the Principality of Capua, long term rival of Naples; however this only lasted three years before the culturally Greco-Roman influenced dukes were reinstated.[36] By the 11th century, like many territories in the area, Naples hired Norman merecenaries, the Christian descendants of the Vikings, to battle their rivals; Duke Sergius IV hired Rainulf Drengot to battle Capua for him.[37]

By 1137, the Normans had grown hugely in influence, controlling previous independent principalities and duchies such as Capua, Benevento, Salerno, Amalfi, Sorrento and Gaeta; it was in this year that Naples, the last independent duchy in the southern part of the peninsula, came under Norman control. The last ruling duke of the duchy Sergius VII was forced to surrender to Roger II, who had proclaimed himself King of Sicily seven years earlier; this saw Naples joining the Kingdom of Sicily, where Palermo was the capital.[38]

The Kingdom

Norman to Angevin

After a period as a Norman kingdom, the Kingdom of Sicily was passed on to the Hohenstaufens who were a highly powerful Germanic royal house of Swabian origins.[39] The University of Naples Federico II was founded by Frederick II in the city, the oldest state university in the world, making Naples the intellectual centre of the kingdom.[40] Conflict between the Hohenstaufen house and the Papacy, led in 1266 to Pope Innocent IV crowning Angevin Dynasty duke Charles I as the king of the kingdom:[41] Charles officially moved the capital from Palermo to Naples where he resided at the Castel Nuovo.[42] During this period much Gothic architecture sprang up around Naples, including the Naples Cathedral, which is the main church of the city.[43]

In 1282, after the Sicilian Vespers, the kingdom split in half. The Angevin Kingdom of Naples included the southern part of the Italian peninsula, while the island of Sicily became the Aragonese Kingdom of Sicily.[41] The wars continued until the peace of Caltabellotta in 1302, which saw Frederick III recognised as king of the Isle of Sicily, while Charles II was recognised as the king of Naples by Pope Boniface VIII.[41] Despite the split, Naples grew in importance, attracting Pisan and Genoese merchants,[44] Tuscan bankers, and with them some of the most championed Renaissance artists of the time, such as Boccaccio, Petrarch and Giotto.[45] In the midst of the 14th century, The Hungarian Angevin king , Louis the Great captured the city several times. Alfonso I conquered Naples after his victory against the last Angevin king, René, Naples was unified for a brief period with Sicily again.[46]

Aragonese to Bourbon

Sicily and Naples were separated in 1458 but remained as dependencies of Aragon under Ferrante.[47] The new dynasty enhanced Naples' commerce by establishing relations with the Iberian peninsula. Naples also became a centre of the Renaissance, with artists such as Laurana, da Messina, Sannazzaro and Poliziano arriving in the city.[48] During 1501 Naples became under direct rule from France at the time of Louis XII, as Neapolitan king Frederick was taken as a prisoner to France; this lasted only four years.[49]

Spain won Naples at the Battle of Garigliano and, as a result, Naples became under direct rule as part of the Spanish Empire throughout the entire Habsburg Spain period.[49] The Spanish sent viceroys to Naples to directly deal with local issues: the most important of which was Pedro Álvarez de Toledo, who was responsible for considerable social, economic and urban progress in the city; he also supported the Inquisition.[50]

During this period Naples became Europe's second largest city after only Paris.[51] It was a cultural powerhouse during the Baroque era as home to artists including Caravaggio, Salvator Rosa and Bernini, philosophers such as Bernardino Telesio, Giordano Bruno, Tommaso Campanella and Giambattista Vico, and writers such as Giambattista Marino. A revolution led by local fisherman Masaniello saw the creation of a brief independent Neapolitan Republic, though this lasted only a few months before Spanish rule was regained.[49] In 1656 the plague killed about half of Naples' 300,000 inhabitants.[52]

Finally, by 1714, the Spanish ceased to rule Naples as a result of the War of the Spanish Succession; it was the Austrian Charles VI who ruled from Vienna, similarly with viceroys.[53] However, the War of the Polish Succession saw the Spanish regain Sicily and Naples as part of a personal union, which in the Treaty of Vienna were recognised as independent under a cadet branch of the Spanish Bourbons in 1738 under Charles VII.[54]

During the time of Ferdinand IV, the French Revolution made its way to Naples: Horatio Nelson, an ally of the Bourbons, even arrived in the city in 1798 to warn against it. However, Ferdinand was forced to retreat and fled to Palermo, where he was protected by a British fleet.[55] Naples' lower classes the lazzaroni were strongly pious and Royalist, favouring the Bourbons; in the mêlée that followed, they fought the Neapolitan pro-Republican aristocracy, causing a civil war.[55]

The Republicans conquered Castel Sant'Elmo and proclaimed a Parthenopaean Republic, secured by the French Army.[55] A counter-revolutionary religious army of lazzaroni known as the sanfedisti under Fabrizio Ruffo was raised; they had great success and the French surrendered the Neapolitan castles and were allowed to sail back to Toulon.[55]

Ferdinand IV was restored as king; however, after only seven years Napoleon conquered the kingdom and instated Bonapartist kings including his brother Joseph Bonaparte.[56] With the help of the Austrian Empire and allies, the Bonapartists were defeated in the Neapolitan War and Bourbon Ferdinand IV once again regained the throne and the kingdom.[56] The Congress of Vienna in 1815 saw the kingdoms of Naples and Sicily combined to form the Two Sicilies,[56] with Naples as the capital city. Naples became the first city on the Italian peninsula to have a railway in 1839 with the construction of the Naples–Portici line,[57] there were many factories throughout the kingdom making it a highly important trade centre.[58]

Italian unification, present day

After the Expedition of the Thousand led by Giuseppe Garibaldi, culminating in the controversial Siege of Gaeta, Naples became part of the Kingdom of Italy in 1861 as part of the Italian unification, ending Bourbon rule. The kingdom of the Two Sicilies had been wealthy and 80 million ducats were taken from the banks as a contribution to the new Italian treasury, while other former states in the Italian unification were forced to pay far less.[58] The economy of the area formerly known as Two Sicilies collapsed, leading to an unprecedented wave of emigration,[59] with estimates claiming at least 4 million of those who left from 1876–1913 were from Naples or near Naples.[60]

Naples was the most bombed Italian city of World War II.[23] Though Neapolitans did not rebel under Italian fascism, Naples was the first Italian city to rise up against German military occupation; the people rose up and freed their own city completely by October 1, 1943.[61] The symbol of the rebirth of Naples was the rebuilding of Santa Chiara which had been destroyed in a United States Army Air corps raid.[23]

Special funding from the Italian government's Fund for the South from 1950 to 1984 helped the economy to improve somewhat, including the rejuvenation of the Piazza del Plebiscito and other city landmarks.[62] Naples still has some issues, however: high unemployment and the Naples waste management issue, the latter of which the media has attributed to the Camorra organised crime network.[63] Recently, the Italian Government under Silvio Berlusconi has held senior meetings in Naples to demonstrate that they intend to tackle these problems once and for all.[64]

Main sights

- See also, Buildings and structures in Naples

Naples has one of the greatest density of cultural resources and monuments that include 2800 years of history (castles, fountains, churches, ancient architecture, etc.): the most prominent forms of architecture in Naples are from the Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque periods.[65] The historic centre of Naples is typically the most fruitful for architecture and is in fact listed by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site.[66] A striking feature of Naples is the fact that it has 448 historical churches, making it one of the most Catholic cities in the world.[67]

Main piazza, palaces and castles

- See also, List of palaces in Naples

The central and main open city square or piazza of the city is the Piazza del Plebiscito. It was started by Bonapartist king Joachim Murat and finished by Bourbon king Ferdinand IV. It is bounded on the east by the Royal Palace and on the west by the church of San Francesco di Paola with the colonnades extending to both sides. Nearby is the Teatro di San Carlo, which is the oldest and largest opera house on the Italian peninsula.[68] Directly across from San Carlo is Galleria Umberto, a shopping centre and active centre of Neapolitan social life in general. Naples is well-known for its historic castles: the ancient Castel Nuovo is one of the most notable architectural representatives on the city, also known as Maschio Angioino; it was built during the time of Charles I, the first ever king of Naples. Castel Nuovo has hosted some historical religious events: for example, in 1294, Pope Celestine V resigned as pope in a hall of the castle, and following this Pope Boniface VIII was elected pope here by the cardinal collegium, and immediately moved to Rome.

The castle which Nuovo replaced in importance was the Norman founded Castel dell'Ovo. Its name means Egg Castle and it is built on the tiny islet Megarides, where the Cumaean colonists founded the city. The third castle of note is Sant'Elmo which was completed in 1329 and is built in the shape of a star. During the uprising of Masaniello, the Spanish took refuge in Sant'Elmo to escape the revolutionaries.

Museums

Naples hosts a wealth of historical museums and some of the most important in the country. The Naples National Archaeological Museum is one of the main museums, considered one of the most important for artifacts of the Roman Empire in the world.[69] It also hosts many of the antiques unearthed at Pompeii and Herculaneum, as well as some artifacts from the Greek and Renaissance periods.[69]

Previously a Bourbon palace, now a museum and art gallery, the Museo di Capodimonte is probably the most important in Naples. The art gallery features paintings from the 13th to the 18th century including major works by Simone Martini, Raphael, Titian, Caravaggio, El Greco and many others, including Neapolitan School painters Jusepe de Ribera and Luca Giordano. The royal apartments are furnished with antique 18th century furniture and a collection of porcelain and majolica from the various royal residences: the famous Capodimonte Porcelain Factory was just adjacent to the palace. In front of Royal Palace of Naples there is the Galleria Umberto I in this building there is the Coral jewellery Museum

The Certosa di San Martino was formerly a monastery complex but is now a museum and remains one of the most visible landmarks of Naples. Displayed within the museum are Spanish and Bourbon-era artifacts, as well as displays of the nativity scene, considered to be among the finest in the world. Pietrarsa railway museum is located in the city: Naples has a proud railway history and the museum features, amongst many other things, the Bayard, the first locomotive in the Italian peninsula.[57] Other museums include the Villa Pignatelli and Palazzo Como, and one of Italy's national libraries (the Biblioteca Nazionale Vittorio Emanuele III) is also located in the city.

Churches, religious buildings and structures

- See also: Churches in Naples and Archdiocese of Naples

Hosting the Archdiocese of Naples, the Catholic faith is highly important to the people of Naples and there are hundreds of churches in the city.[67] The Cathedral of Naples is the most important place of worship in the city, each year on September 19 it hosts the Miracle of Saint Januarius, the city's patron saint.[70] In the miracle which thousands of Neapolitans flock to witness, the dried blood of Januarius is said to turn to liquid when brought close to relics said to be of his body: this is one of the most important traditions for Neapolitans.[70] Below is a selective list of some of the best-known churches, chapels, monastery complexes and religious structures in Naples;

Other features

Aside from the main piazza there are two more in the form of Piazza Dante and Piazza dei Martiri. The latter is somewhat controversial: it originally just had a memorial to martyrs but in 1866, after the Italian unification, four lions were added, representing the four rebellions against the Bourbons.[71]

Founded in 1667 by the Spanish, the San Gennaro dei Poveri is a hospital for the poor which is still in existence today. It was a forerunner of a much more ambitious project, the gigantic Bourbon Hospice for the Poor started by Charles III. This was for the destitute and ill of the city; it also provided a self-sufficient community where the poor would live and work: today it is no longer a hospital.[72]

Beneath Naples

Underneath Naples there is a series of caves and structures created by centuries of mining, which is in part of an underground geothermal zone. Subterranean Naples consists of old Greco-Roman reservoirs dug out from the soft tufo stone on which, and from which, the city is built. Approximately one kilometer of the many kilometers of tunnels under the city can be visited from the well known "Napoli Sotteranea" situated in the historic centre of the city in Via dei Tribunali. There are also large catacombs in and around the city and other visits such as Piscina Mirabilis, the main cistern serving the Bay of Naples during Roman times. This system of tunnels and cisterns covers most of the city and lies approximately thirty meters below ground level. Moisture levels are around 70%. During World War II, these tunnels were used as air raid shelters and there are inscriptions in the walls which depict the suffering endured during that time.

Parks, gardens and villas

Of the public parks in Naples, the most prominent is the Villa Comunale, previously known as the Royal Garden as its building was ordered by Bourbon king Ferdinand IV in the 1780s.[73] The second most important park is Parco Virgiliano which is very green and has views towards the tiny volcanic islet of Nisida; beyond that in the distance are Procida and Ischia.[74] It was named after Virgil the classical Roman poet who is thought to be entombed nearby.[74] There was also a tomb of greatness in Naples that Villa Comunale found in 1832. There are also many attractive villas in Naples, such as the Neoclassical Villa Floridiana, built in 1816.

Around Naples

The islands of Procida, (famously used as the set for much of the film Il Postino), Capri and Ischia can all be reached quickly by hydrofoils and ferries. Sorrento and the Amalfi Coast are situated south of Naples. The Roman ruins of Pompeii, Herculaneum and Stabiae (destroyed in the 79 AD eruption of Vesuvius) are also nearby. As well, Naples is near the volcanic area known as the Campi Flegrei and the port towns of Pozzuoli and Baia, which were part of the vast Roman naval facility, Portus Julius.

Geography

In the area surrounding Naples are the islands of Procida, Capri and Ischia, which are reached by hydrofoils and ferries. Sorrento and the Amalfi Coast are situated south of Naples. The Roman ruins of Pompeii, Herculaneum and Stabiae, which were destroyed in the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 AD, are also nearby. Naples is also near the volcanic area known as the Campi Flegrei and the port towns of Pozzuoli and Baia, which were part of the vast Roman naval facility, Portus Julius.

Quarters

|

1. Pianura |

11. Montecalvario |

21. Piscinola-Marianella |

Shown above are the thirty quarters of Naples: these thirty neighbourhoods or "quartieri" as they are known, are grouped together into ten governmental community boards.[75]

Climate

Naples enjoys a typical Mediterranean climate with mild, wet winters and warm to hot, dry summers. The mild climate and the geographical richness of the bay of Naples made it famous during Roman times, when emperors chose the city as a favourite holiday location.

| Climate data for Naples | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 12.5 (54.5) |

13.2 (55.8) |

15.2 (59.4) |

18.2 (64.8) |

22.6 (72.7) |

26.2 (79.2) |

29.3 (84.7) |

29.5 (85.1) |

26.3 (79.3) |

21.8 (71.2) |

17.0 (62.6) |

13.6 (56.5) |

20.4 (68.7) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 8.1 (46.6) |

8.7 (47.7) |

10.5 (50.9) |

13.2 (55.8) |

17.3 (63.1) |

20.9 (69.6) |

23.6 (74.5) |

23.7 (74.7) |

20.8 (69.4) |

16.7 (62.1) |

12.3 (54.1) |

9.3 (48.7) |

15.4 (59.7) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 3.8 (38.8) |

4.3 (39.7) |

5.9 (42.6) |

8.3 (46.9) |

12.1 (53.8) |

15.6 (60.1) |

18.0 (64.4) |

17.9 (64.2) |

15.3 (59.5) |

11.6 (52.9) |

7.7 (45.9) |

5.1 (41.2) |

10.4 (50.7) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 104.4 (4.11) |

97.9 (3.85) |

85.7 (3.37) |

75.5 (2.97) |

49.6 (1.95) |

34.1 (1.34) |

24.3 (0.96) |

41.6 (1.64) |

80.3 (3.16) |

129.7 (5.11) |

162.1 (6.38) |

121.4 (4.78) |

1,006.6 (39.63) |

| Average precipitation days | 9.9 | 9.8 | 9.5 | 8.8 | 5.7 | 4.0 | 2.3 | 3.8 | 5.8 | 8.1 | 10.8 | 10.7 | 89.2 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 114.7 | 127.6 | 158.1 | 189.0 | 244.9 | 279.0 | 313.1 | 294.5 | 234.0 | 189.1 | 126.0 | 105.4 | 2,375.4 |

| Source: World Meteorological Organization (UN),[76] Italiano della Meteorologia[77] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1861 | 484,026 | — |

| 1871 | 489,008 | +1.0% |

| 1881 | 535,206 | +9.4% |

| 1901 | 621,213 | +16.1% |

| 1911 | 751,290 | +20.9% |

| 1921 | 859,629 | +14.4% |

| 1931 | 831,781 | −3.2% |

| 1936 | 865,913 | +4.1% |

| 1951 | 1,010,550 | +16.7% |

| 1961 | 1,182,815 | +17.0% |

| 1971 | 1,226,594 | +3.7% |

| 1981 | 1,212,387 | −1.2% |

| 1991 | 1,067,365 | −12.0% |

| 2001 | 1,004,500 | −5.9% |

| 2009 | 962,638 | −4.2% |

| Source: ISTAT 2001 | ||

The population of the centre area (municipality – comune di Napoli) is around one million people. Its greater metropolitan area, sometimes known as Greater Naples has an additional population of 4.4 million and include all the province and over; the towns which are usually included within this area are Arzano, Casandrino, Casavatore, Casoria, Cercola, Marano di Napoli, Melito di Napoli, Mugnano di Napoli, Portici, Pozzuoli, Quarto, San Giorgio a Cremano, San Sebastiano al Vesuvio, Volla.[78] The demographic profile for the Neapolitan province in general is quite young: 19% are under age 14, while 13% are over 65, compared to the national average of 14% and 19%, respectively.[78] There is a higher percentage of females (52.4%) than males (47.6%).[citation needed] Naples currently has a higher birth rate than other parts of Italy with 10.46 births per 1,000 inhabitants compared to the Italian average of 9.45 births.[79]

Unlike many northern Italian cities there are far fewer immigrants in Naples. 98.5% of the people are Italians. In 2006, there were a total of 19,188 foreigners in the actual city of Naples; the majority of foreigners are Eastern European, coming particularly from Ukraine, Poland and the Balkans.[80] Non-Europeans in general are very low in number, however there are some small Sri Lankan and East Asian immigrant communities. Statistics show that the vast majority of immigrants are female; this is because male workers tend to head North.[78][80]

Education

There are many public and private institutions of higher education in Naples, as well as numerous institutes and research centres. Naples hosts what is thought to be the oldest state university in the world in the form of the University of Naples Federico II, which was founded by Frederick II during 1224.[40] It is by far the most important university in southern Italy, with around 100,000 students and over 3000 professors.[81] Part of the university is the important Botanical Garden of Naples which was opened in 1807 by Giuseppe Bonaparte (using Bourbon king Ferdinand IV's plans). Its 15 hectares feature around 25,000 samples of vegetation, covering about 10,000 plant species.[82]

People from the city are also served by the Seconda Università degli Studi di Napoli, the second most important university of the city, opened far more recently in 1989, which, despite its name, has strong links to the nearby province of Caserta.[83] A unique centre of education in the city is the Istituto Universitario Orientale which specialises in Eastern culture, founded by Jesuit missionary Matteo Ripa in 1732 after he returned from work in the court of Kangxi Emperor of the Manchu Qing Dynasty in China.[84] There are other prominent universities in Naples too, such as the Parthenope University of Naples, the private Istituto Universitario Suor Orsola Benincasa and the Jesuit-run Theological Seminary of Southern Italy.[85][86] In keeping with its strong musical legacy, Naples has a place to study music in the form of the San Pietro a Maiella music conservatory. The earliest music conservatories of Naples go back to the 16th century under the Spanish rule.[87]

Governance

Politics

Each of the 8,101 comune in Italy is today represented locally by an elected mayor and a city council, known as a sindaco and informally called the first citizen. This system or one very similar to it, has been in place since 1808 with the invasion of the Napoleonic forces. When the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies was restored, the system was kept in place with members of the nobility such as Dukes and Marquesses filling the role. By the end of the 19th century as part of Italy, party politics had begun to emerge; during the fascist era each commune was represented by a podestà. During the post-war period, the political landscape of Naples has been neither strongly right nor left — both Christian democracts and democratic socialists have filled the position at different times with roughly equal frequency. Currently the mayor of Naples is Rosa Russo Iervolino of The Olive Tree, she has held the position since 2001.[88]

Administrative subdivisions

| Map | Municipality | Population | President | Quarters |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| I | 84,067 | Fabio Chiosi | Chiaia, Posillipo, San Ferdinando | |

| II | 91,536 | Alberto Patruno | Montecalvario, San Giuseppe, Avvocata, Porto, Pendino, Mercato | |

| III | 103,633 | Alfonso Principe | Stella, San Carlo all'Arena | |

| IV | 96,078 | David Lebro | San Lorenzo, Vicaria, Poggioreale, Zona Industriale | |

| V | 119,978 | Mario Coppeto | Arenella, Vomero | |

| VI | 84,067 | Anna Cozzino | San Giovanni a Teduccio, Barra, Ponticelli | |

| VII | 91,460 | Giuseppe Esposito | Miano, Secondigliano, S.Pietro a Patierno | |

| VIII | 92,616 | Carmine Malinconico | Chiaiano, Piscinola-Marianella, Scampìa | |

| IX | 106,299 | Fabio Tirelli | Pianura, Soccavo | |

| X | 101,192 | Giuseppe Balzamo | Bagnoli, Fuorigrotta |

Economy

Naples is Italy's fourth most important city for economic strength, coming after Milan, Rome and Turin. It is the world's 91st richest city by purchasing power, with a GDP of $43 billion.[13] Were Naples a country, it would have the world's 68th biggest economy, near the size of that of Qatar. The economy of Naples and its closest surrounding area is based largely in tourism, commerce, industry and agriculture; Naples also acts as a busy cargo terminal, and the port of Naples is one of the Mediterranean's biggest and most important. The city has had a remarkable economic growth since the war, and unemployment in the region has gone down dramatically since 1999.[15] Naples used to be a busy industrial city, though many of the factories are no longer there, and Naples is still characterized by high levels of corruption and organized crime.

Naples is also a major international and national tourist destination. The city is, and has always been, one of Italy and Europe's top tourist city destinations, with the first tourists coming in the 18th century during the Grand Tour. In terms of international arrivals, Naples came 166th in the world in 2008, with 381,000 visitors (a −1.6% decrease from the previous year), coming after Lille, but overtaking York, Stuttgart, Belgrade and Dallas.[89]

In recent times, there has been a move away from traditional agriculture-based economy in the province to one based on service industries.[90] In early 2002 there were over 249,590 enterprises operating in the province of Naples registered in the Chamber of Commerce Public Register.[90] This sector employs the majority of the people, though more than half of these are small enterprises with fewer than 20 workers; 70 companies are medium-sized with more than 200 workers; and 15 have more than 500 workers.[90] Employment in the province of Naples in different sectors breaks down as follows:[90]

| Public services | Manufacturing | Commerce | Construction | Transportation | Financial services | Agriculture | Hotel trade | Other activities | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage | 30.7% | 18% | 14% | 9.5% | 8.2% | 7.4% | 5.1% | 3.7% | 3.4% |

Transport

Naples is well connected in regards to major motorways, known in Italy as autostrada. From Naples all the way north to Milan is the A1 known as autostrada del Sole (motorway of the sun), the longest transalpine motorway on the peninsula.[91] There are other motorways from Naples too, such as the A3 which goes southwards to Salerno where the motorway to Reggio Calabria begins, as well as the A16 which goes across east to Canosa.[92] The latter is called the autostrada dei Due Mari (motorway of the Two Seas) because it connects the Tyrrhenian Sea to the Adriatic Sea.[93]

Within the actual city itself there are many public transport services, including trams, buses, funiculars and trolleybuses.[94] Three public elevators are active within the bridge of Chiaia, in via Acton and nearby the Sanità Bridge.[95] Naples also has its own Naples Metro, the underground rapid transit railway system of the city which has integrated into one single service system the several railways lines of Naples and its metro stations.[94] Suburban rail services are provided by Trenitalia, Circumvesuviana, Ferrovia Cumana and Metronapoli.

The main general train station of the city is Napoli Centrale, which is located in Piazza Garibaldi; the next most significant stations are Napoli Campi Flegri[96] and Napoli Mergellina, respectively. Naples has lots of narrow streets (it was the first town in the world to set up a pedestrian one-way[97]), so the general public commonly use compact hatchback cars and scooters are especially common.[98] Naples is now connected to Rome by a high-speed railway with trains running at almost 300 km/h (186 mph), reducing journey time to under an hour; the system was introduced in 2007.[99]

The port of Naples has several ferry, hydrofoil and SWATH catamarans services open to the general public, most of which are to places within the Neapolitan province such as Capri, Ischia and Sorrento, or the Salernitan province, such as Salerno, Positano and Amalfi.[100] There are however some which go to destinations further afield, such as Sicily, Sardinia, Ponza and the Aeolian Islands.[100] There are many enterprises at the port, which is important for transferring cargo and is a growing centre of commerce in general. Within the scope of suburb San Pietro a Patierno is the Naples International Airport, the most important airport in southern Italy, which serves millions of people each year with around 140 flights arriving or departing daily.[101]

Culture

Art

Naples has always played a central role in Italian art and more generally in the art and architecture of Europe. This is demonstrated by the several works of art in Medieval, Renaissance and especially Baroque churches, castles and palaces. In the 18th century, Naples went through a period of neoclassicism, with the caving expeditions involving the discovery of Herculaneum and then Pompeii being promoted, and many of these archaeological discoveries were exposed to Naples in a period where several artists and students visited it from around the continent.

The Neapolitan Academy of Fine Arts, founded by Charles III of Bourbon in 1752 as the "Real Accademia di Disegno (Royal Academy of Design)" was the centre of the School of Posillipo in the 19th century and was led by figures such as Domenico Morelli, Giacomo Di Chirico, Francesco Saverio Altamura, Gioacchino Toma. Many of their works are exhibited in art collection housed by the Academy. Courses are held today in painting, decorating, sculpture, design, restoration, and urban planning.

There is also the historic tradition of the San Pietro a Majella music conservatory, in the heart of the city, founded in 1826 by Francesco I of Bourbon as "Royal Conservatory music", and where lessons are held today for all musical instruments and has hosted a remarkable music museum. Finally, to report the offer of theaters, a tradition among the oldest in Europe (the St. Charles dates back to the 18th century), which today includes twelve main theaters.

Also important the artistic tradition of the Capodimonte porcelain. In 1743, Charles of Bourbon founded the Royal Factory of Capodimonte beginning the production of artistic works kept in the Museum of Capodimonte, in the more hilly area of Naples. This tradition is still kept alive through the efforts of several Neapolitan factories founded in the mid-19th century and still operating today.

Cuisine

The city has a long history of producing a variety of famous dishes and wines; it draws its influence from different civilisations which have ruled the city at various times such as the Greeks, Spanish and French.[102] Neapolitan cuisine emerged completely as its own distinct form in the 18th century.[102] The ingredients are typically rich in taste while remaining affordable to the general populace.[103]

Perhaps the best-known aspect of Neapolitan cooking is its rich savoury dishes. Naples is traditionally held as the home of pizza.[104] This originated as a meal of the poor, but under Ferdinand IV it became better known: famously, the Margherita was named after Queen Margherita after a visit to the city.[104] Cooked traditionally in a wood-burning oven, ingredients are strictly regulated by a law dating from 2004, and must be composed of wheat flour type "00" with the addition of flour type "0" yeast, natural water, peeled tomatoes or fresh cherry tomatoes, marine salt, and extra virgin olive oil.[104] Spaghetti is associated with the city and is commonly eaten with the sauce ragù: a Neapolitan symbol is folklore figure Pulcinella eating a plate of spaghetti.[105] Others include parmigiana di melanzane, mozzarella, spaghetti alle vongole and casatiello.[106]

Naples also has some famous sweet dishes, including colourful gelato, similar though more fruit-based than ice cream.[107] Some of the pastry dishes include: zeppole, babà, sfogliatelle and pastiera, the latter of which is prepared especially for Easter.[108] Another seasonal sweet is struffoli, a sweet tasting honey dough decorated and eaten around Christmas.[109]

Naples is also famous worldwide for its Neapolitan coffee, made with historical Neapolitan flip coffee pot called "cuccuma" or cuccumella, which then led to the invention of the espresso machine and inspired the Moka pot. Many small businesses for roasting and grounding coffee beans mixed from the best coffee qualities produced worldwide are present in the territory of Naples.

There are also some beverages from Naples: it produces wines from the Vesuvius area such as Lacryma Christi ("tear of Christ") and Terzigno. Also from Naples is limoncello the highly popular lemon liqueur.[110][111]

Film

Naples has been the setting in literature and in film. Comedies set in Naples include It Started in Naples, L'oro di Napoli by Vittorio De Sica and Dino Risi's Scent of a Woman. The 2008 award-winning film "Gomorrah" based on the book by Roberto Saviano, explores the dark underbelly of the city of Naples and its economy through 5 separate intertwining stories about Naples crime syndicate the "Camorra". The 1954 Tom and Jerry cartoon Neapolitan Mouse was based in Naples where Tom and Jerry visited Naples on a cruise.

Language

The city of Naples has developed its own language, the Naples dialect, which is mainly spoken in the city, and the region of Campania, has also been diffused in other areas of Southern Italy. On October 14, 2008 a law by the Region of Campania stated that the Neapolitan language had to be protected.[112]

The name is often given to the varied Italo-Western group of dialects of Southern Italy; for example Ethnologue groups the dialects as a separate Romance language called Napoletano-Calabrese.[113] This linguistic group is spoken throughout most of southern continental Italy, including the Gaeta and Sora districts of southern Lazio, the southern part of Marche and Abruzzo, Molise, Basilicata, northern Calabria, and northern and central Puglia. As of 1976, there were 7,047,399 theoretical native speakers of this group of dialects.[113]

Music

Naples has played an important and vibrant role over the centuries in the general history of western European musical traditions.[114] The history of Naples as a strong musical power can be traced back to the time of Spanish rule where organised music conservatories of Naples were first introduced. It was during the late Baroque period that Alessandro Scarlatti (father of Domenico Scarlatti) established the Neapolitan school of opera; this was in the form of opera seria which was a new development for its time.[115] Another form of opera originating in Naples is opera buffa, a comic opera strongly linked to Battista Pergolesi and Piccinni; later Rossini and Mozart would use the genre.[116] The grandiose Teatro di San Carlo built in 1737, the oldest working theatre in Europe, was the operatic centre of the city and remains so to this day.[117]

The earliest six-string guitar was created by a Neapolitan named Gaetano Vinaccia in 1779 (known as the romantic guitar); the Vinaccia family had also developed the mandolin.[118][119] Along with the Spanish, Neapolitans became pioneers of classical guitar music with Ferdinando Carulli and Mauro Giuliani being prominent exponents.[120] Giuliani was actually from further south in the Kingdom of Naples – Apulia – but had moved to Naples; Giuliani is considered to be one of the greatest guitar players and composers of the 19th century, along with his great Catalan contemporary Fernando Sor.[121][122] Another Neapolitan musical artist who had an impact on the world stage is opera singer Enrico Caruso, one of the most famous and respected tenors of all time:[123] he was considered a man of the people in Naples and came from a working class background.[124]

Perhaps the most well known part of Neapolitan music is the Canzone Napoletana style, essentially the traditional music of the city with a repertoire of hundreds of folk songs, some of which can be traced back to the 13th century.[125] The songs O sole mio and Funiculì Funiculà are part of this style and are known far and wide outside of Naples. The genre became a formal institution in 1835 thanks to the introduction of the annual Festival of Piedigrotta songwriting competition.[125] Some of the best-known recording artists in this field includes Roberto Murolo, Sergio Bruni and Renato Carosone.[126] There are other forms of music played in Naples which are not well known outside the area but hugely popular within it, such as cantautore (singer-songwriter) and sceneggiata, which has been described as a musical soap opera; the most well known artist of this style is Mario Merola.[127]

There is also the historic tradition of the San Pietro a Majella music conservatory, in the heart of the city, founded in 1826 by Francesco I de Bourbon as "Royal Conservatory music", and where lessons are held today for all musical instruments and has hosted a remarkable music museum. There are also several theaters, which is a tradition amongst the oldest in Europe (the Teatro di San Carlo dates back to eighteenth century), which today includes twelve main theaters.

Sports

Football is by far the most popular sport in Naples. Brought to the city by the English during the early 20th century,[128] it is deeply embedded in local culture: it is played by a large part of the youth, from the scugnizzi (street children of Naples) to professional level. The best-known club from the city is SSC Napoli, that plays its home games at the Stadio San Paolo in Fuorigrotta. The team plays in the Serie A league and has won the Scudetto twice during the time when Diego Maradona was a Napoli player. They have also won the UEFA Cup , also during the Maradona era.[129]

The city has produced numerous professional players, the most famous of whom are Ciro Ferrara, and Fabio Cannavaro. Cannavaro was Italy's captain until 2010 and led the national team to the 2006 World Cup as captain. He was consequently World Player of the Year. Some of the smaller clubs from the city include Sporting Neapolis and Internapoli that play at the Stadio Arturo Collana. The city has also participants in other sports: Eldo Napoli represents the city in basketball's Serie A and plays in the city of Bagnoli. Partenope Rugby are the best-known rugby union side: the team has won the rugby version of Serie A twice. Other sports include water polo, horse racing, sailing, fencing, boxing, taekwondo and martial arts. The "Accademia Nazionale di Scherma" (National Academy and Fence School of Naples) is the only place in Italy where the titles "Master of Sword" and "Master of Kendo" can be obtained.[130]

Notable people

- Statius (45–96), poet

- Pope Boniface V (died 625), pope

- Pope Urban VI (1318–1389), pope

- Joan I of Naples (1328–1382), queen

- Pope Boniface IX (1356–1404), pope

- Alfonso II of Naples (1448–1495), king

- Jacopo Sannazaro (1458–1530), poet

- Pirro Ligorio (1510–1583), architect

- Giordano Bruno (1548–1600), philosopher

- Luca Valerio (1552–1618), mathematician

- Giambattista Marino (1569–1625), poet

- Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598–1680), sculptor, painter, architect

- Salvator Rosa (1615–1673), poet, satirist, painter

- Francesco Antonio Picchiati (1619–1694), architect

- Masaniello (1622–1647), revolutionary

- Gennaro Annese (1604–1648), revolutionary

- Luca Giordano (1634–1705), painter

- Ludovico Sabbatini (1650–1724), religious teacher, priest

- Giambattista Vico (1668–1744), philosopher

- Ferdinando Sanfelice (1675–1748), painter

- Domenico Antonio Vaccaro (1678–1745) architect, painter

- Domenico Scarlatti (1685–1757), composer

- Nicola Porpora (1686–1768), composer

- Alphonsus Liguori (1696–1787), saint, writer

- Ferdinand I of the Two Sicilies (1751–1825), king

- Gaetano Filangieri (1752–1788), jurist

- Raffaele Sacco (1787–1872), poet, inventor, lyricist

- Salvadore Cammarano (1801–1852), librettist, poet, playwright

| class="col-break " |

- Domenico Morelli (1823–1901), painter

- Lord Acton (1834–1902), historian

- Peppino Turco (1846–1907), songwriter, journalist

- Lamont Young (1851–1929), architect

- Vincenzo Gemito (1852–1929), sculptor

- Ruggero Leoncavallo (1857–1919), composer

- Salvatore Di Giacomo (1860–1934), poet

- Ferdinando Russo (1866–1927), poet, journalist, writer

- Victor Emmanuel III of Italy (1869–1947), king

- Enrico Caruso (1873–1921), opera singer

- Enrico De Nicola (1877–1959), president, jurist, journalist

- Totò (1898–1967), actor

- Eduardo De Filippo (1900–1984), actor, writer

- Renato Caccioppoli (1904–1959), mathematician

- Renato Carosone (1920–2001), singer-songwriter, musician

- Giorgio Napolitano (1925 – ), politician, president

- Fausto Sarli (1927–2010), fashion designer

- Mario Merola (1934–2005), singer

- Riccardo Muti (1941 - ), conductor

- Michele Campanella (1947 – ), pianist and conductor

- Gianni Nazzaro (1948) singer,actor

- Massimo Troisi (1953–1994), actor

- Pino Daniele (1955 – ), singer-songwriter, musician

- Fabio Cannavaro (1973 – ), World Cup-winning footballer

- Antonio Di Natale (1977 – ), national footballer

- Massimiliano Rosolino (1978 – ), swimmer, olympian

- Roberto Saviano (1979 – ), journalist, writer

- Ambra Vallo, principal dancer

Twin towns — sister cities

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

| |

| Criteria | Cultural: ii, iv |

| Reference | 726 |

| Inscription | 1995 (19th Session) |

Naples is involved in town twinning (known as gemellaggio in Italian), a mutual partnership with several cities. Below are partner cities listed on the official website of the city of Naples;[131]

Kagoshima, Japan[132]

Kagoshima, Japan[132] London, United Kingdom

London, United Kingdom Miami, United States

Miami, United States Baku, Azerbaijan

Baku, Azerbaijan Athens, Greece

Athens, Greece Budapest, Hungary[133][134]

Budapest, Hungary[133][134] Călăraşi, Romania

Călăraşi, Romania Gafsa, Tunisia

Gafsa, Tunisia Kolkata, India

Kolkata, India Nablus, Palestinian Authority

Nablus, Palestinian Authority Nosy Be, Madagascar

Nosy Be, Madagascar Palma, Spain

Palma, Spain Santiago de Cuba, Cuba

Santiago de Cuba, Cuba Santiago de Cuba Province, Cuba

Santiago de Cuba Province, Cuba Valencia, Carabobo, Venezuela

Valencia, Carabobo, Venezuela İzmir, Turkey

İzmir, Turkey Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, since 1964[135]

Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, since 1964[135]

UNESCO site

Since 1995, the historic centre of Naples has been listed as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO, a programme which aims to catalogue, name, and conserve sites of outstanding cultural or natural importance to the common heritage of mankind. The deciding committee who evaluate potential candidates described Naples' centre as being "of exceptional value", and went on to say that Naples' "setting on the Bay of Naples gives it an outstanding universal value which has had a profound influence".[66]

See also

- Camorra

- List of radio stations in Naples

- Neapolitan language

- Neapolitan Mastiff

- Diego Armando Maradona

- Sirenuse

- University of Naples Federico II

References

Bibliography

- Harold Acton, The Bourbons of Naples (1734-1825), London, Methuen, 1956.

- Harold Acton, The Last Bourbons of Naples (1825-1861), London, Methuen, 1961.

- Buttler, Michael; Harling, Kate (March 2008). Paul Mitchell (ed.). Naples (Third ed.). Basingstoke, Hampshire, United Kingdom: Automobile Association Developments Limited 2007. ISBN 9780749552480. Retrieved 11 March 2010.

- Edward Chaney, 'Inigo Jones in Naples', The Evolution of the Grand Tour, London, Routledge 2000.

Notes

- ^ "Superficie di Comuni Province e Regioni italiane al 9 ottobre 2011". Italian National Institute of Statistics. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- ^ ‘City’ population (i.e. that of the comune or municipality) from demographic balance: January–April 2009, ISTAT.

- ^ Gleijeses, Vittorio (1977). The History of Naples, since Origins to Modern Times. Naples.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Chronology of the history of Naples". Danpiz.net. Retrieved 2011-03-13.

- ^ "Greek Naples". Faculty.ed.umuc.edu. Retrieved 2010-01-25.

- ^ "Napoli, La Storia della Città Napoli Musei – Napoli chiese – Napoli museo archeologico – Napoli monumenti – Napoli teatri – Napoli Italia". Pintostorey.it. Retrieved 2010-03-28.

- ^ Nome (2008-05-27). "The historic city center of Naples". Vicolostorto.wordpress.com. Retrieved 2011-03-13.

- ^ "1.700 hectares". Comune.napoli.it. Retrieved 2011-03-13.

- ^ "Centro Storico di Napoli". Unesco.it. Retrieved 2010-01-25.

- ^ "Seminario-aprile2001.PDF" (PDF). Retrieved 2009-07-19.

- ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ OECD. "Competitive Cities in the Global Economy" (PDF). Retrieved 2009-04-30.

- ^ a b "City Mayors reviews the richest cities in the world in 2005". Citymayors.com. 2007-03-11. Retrieved 2010-01-25.

- ^ "The port of Naples". Ilmediterraneo.it. 2010-03-19. Retrieved 2011-03-13.

- ^ a b "Site3-TGM table". Epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 2010-01-25.

- ^ "Cordova: 'Visto? La corruzione a Napoli non si è mai fermata' – Repubblica.it » Ricerca". Ricerca.repubblica.it. Retrieved 2010-03-14.

- ^ "SRM Studi e Ricerche per il Mezzogiorno – Ricerche". Srmezzogiorno.it. 2006-05-01. Archived from the original on April 6, 2008. Retrieved 2010-03-14.

- ^ "OPE impresa (sede in Napoli - Centro direzionale)". Casertanews.it. 2010-06-09. Retrieved 2011-03-13.

- ^ "Centro studi OPE (sede in Napoli dal 1 febbraio 2009)". Happystudent.it. Retrieved 2011-03-13.

- ^ Eurocities. "EUROCITIES – the network of major European cities". Eurocities.eu. Retrieved 2010-02-03.

- ^ "Dipartimento politiche comunitarie: Napoli sede dell'ACP-UE. Ronchi: "Pieno sostegno dei nostri europarlamentari"". Politichecomunitarie.it. Retrieved 2010-03-14.

- ^ da claudio calveri. "Naples city of Unesco's literature". Napolicittadellaletteratura.wordpress.com. Retrieved 2011-03-13.

- ^ a b c "Bombing of Naples". Faculty.ed.umuc.edu. 7 October 2007.

- ^ Manuela Proietti. "Expo 2012, Napoli capitale dello spazio| Iniziative | DIREGIOVANI". Diregiovani.it. Retrieved 2010-01-25.

- ^ "Center of Naples, Italy". Chadab Napoli. 2007-06-24.

- ^ "Chronology of the history of Naples". Danpiz.net. Retrieved 2011-03-13.

- ^ "Greek Naples". Faculty.ed.umuc.edu. Retrieved 2010-01-25.

- ^ "Napoli, La Storia della Città Napoli Musei – Napoli chiese – Napoli museo archeologico – Napoli monumenti – Napoli teatri – Napoli Italia". Pintostorey.it. Retrieved 2010-03-28.

- ^ "Greek Naples". Faculty.ed.umuc.edu. 8 January 2008.

- ^ a b c "Antic Naples". Naples.Rome-in-Italy.com. 8 January 2008.

- ^ {{cite news |url| publisher= Touring Club of Italy| title =Touring Club of Italy, Naples: The City and Its Famous Bay, Capri, Sorrento, Ischia, and the Amalfi, Milano | url =http://books.google.com/books?id=u23MlfA8pcoC&printsec=frontcover&dq=Touring+Club+of+Italy,+Naples:+The+City+and+Its+Famous+Bay,+Capri,+Sorrento,+Ischia,+and+the+Amalfi&hl=en&ei=jD_HTaW2H6Th0gHlp7TxBw&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CGgQ6AEwAA#v=snippet&q=campanian%20people&f=false | isbn =88-365-2836-8 |page=11 |year=2003}

- ^

"Naples" in the 1913 Catholic Encyclopedia.

"Naples" in the 1913 Catholic Encyclopedia.

- ^ a b Wolfram, Herwig. The Roman Empire and Its Germanic Peoples. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520085114.

- ^ "Belisarius – Famous Byzantine General". About.com. 8 January 2008.

- ^ a b Kleinhenz, Christopher. Medieval Italy: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415221269. Cite error: The named reference "byz" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b c McKitterick, Rosamond. The New Cambridge Medieval History. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521853606.

- ^ Bradbury, Jim. The Routledge Companion to Medieval Warfare. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415221269.

- ^ "Kingdom of Sicily, or Trinacria". Britannica.com. 8 January 2008.

- ^ "Swabian Naples". Faculty.ed.umuc.edu. 7 October 2007.

- ^ a b "Italy: PhD Scholarships in Various Fields at University of Naples-Federico II". ScholarshipNet.info. 7 October 2007.

- ^ a b c "Sicilian History". Dieli.net. 7 October 2007.

- ^ "Naples – Castel Nuovo". PlanetWare.com. 7 October 2007.

- ^ Bruzelius, Caroline. "ad modum franciae": Charles of Anjou and Gothic Architecture in the Kingdom of Sicily. The Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians.

- ^ Constable, Olivia Remie. Housing the Stranger in the Mediterranean World: Lodging, Trade, and Travel. Humana Press. ISBN 1588291715.

- ^ "Angioino Castle, Naples". Naples-City.info. 7 October 2007.

- ^ "Aragonese Overseas Expansion, 1282–1479". Zum.de. 7 October 2007.

- ^ "Ferrante of Naples: the statecraft of a Renaissance prince". Questia.com. 7 October 2007.

- ^ "Naples Middle-Ages". Naples.Rome-in-Italy.com. 7 October 2007.

- ^ a b c "Spanish acquisition of Naples". Britannica.com. 7 October 2007.

- ^ "Don Pedro de Toledo". Faculty.ed.umuc.edu. 7 October 2007.

- ^ "Naples Through the Ages". Fodors.com. 7 October 2007.

- ^ "Naples in the 1600s". Faculty.ed.umuc.edu. Retrieved 2008-11-03.

- ^ "Charles VI, Holy Roman emperor". Bartleby.com. 7 October 2007.

- ^ "Charles of Bourbon – the restorer of the Kingdom of Naples". RealCasaDiBorbone.it. 7 October 2007.

- ^ a b c d "The Parthenopean Republic". Faculty.ed.umuc.edu. 7 October 2007.

- ^ a b c "Austria Naples – Neapolitan War 1815". Onwar.com. 7 October 2007.

- ^ a b "La dolce vita? Italy by rail, 1839–1914". Questia.com. 7 October 2007.

- ^ a b "Why Neo-Bourbons". NeoBorbonici.it. 7 October 2007.

- ^ "Italians around the World: Teaching Italian Migration from a Transnational Perspective". OAH.org. 7 October 2007.

- ^ "Social Networks and Migrations: Italy 1876–1913". Enrico Moretti. 7 October 2007.

- ^ "Contemporary Time". Naples.Rome-in-Italy.com. 7 October 2007.

- ^ "North and South: The Tragedy of Equalization in Italy" (PDF). Frontier Center for Public Policy. 7 October 2007.

- ^ "Naples at the mercy of the mob". BBC.co.uk. 7 October 2007.

- ^ "Berlusconi Takes Cabinet to Naples, Plans Tax Cuts, Crime Bill". Bloomberg.com. 7 October 2007.

- ^ "historical centre". INaples.it. 7 October 2007.

- ^ a b "Historic Centre of Naples". UNESCO. 8 January 2008.

- ^ a b "Naples". Red Travel. 8 January 2008.

- ^ "Naples: View across the Piazza del Plebiscito". London: Telegraph.co.uk. 8 January 2008. [dead link]

- ^ a b "Napoli". Best.unina.it. 8 January 2008.

- ^ a b "Saint Gennaro". SplendorofTruth.com. 8 January 2008.

- ^ "Piazza Dei Martiri". INaples.it. 8 January 2008.

- ^ Ceva Grimaldi, Francesco. Della città di Napoli dal tempo della sua fondazione sino al presente. Original from Harvard University.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|origdate=ignored (|orig-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "Villa Comunale". Faculty.ed.umuc.edu. 8 January 2008.

- ^ a b "Parco Virgiliano". SkyTeam.com. 8 January 2008.

- ^ "Quartieri". Palapa.it. 8 January 2008.

- ^ "Weather Information for Naples".

- ^ "Visualizzazione tabella CLINO della stazione / CLINO Averages Listed for the station Napoli Capodichino".

- ^ a b c "Demographics of Naples". Faculty.ed.umuc.edu. 8 January 2008.

- ^ "Demographics". ISTAT.it. 8 January 2008.

- ^ a b "Commune Napoli". ISTAT. 8 January 2008.

- ^ "University of Naples "Federico II"". UNINA.it. 7 October 2007.

- ^ "Orto Botanico di Napoli". OrtoBotanico.UNINA.it. 7 October 2007.

- ^ "Scuola: Le Università". NapoliAffari.com. 7 October 2007.

- ^ Ripa, Matteo. Memoirs of Father Ripa: During Thirteen Years Residence at the Court of Peking in the Service of the Emperor of China. New York Public Library.

- ^ "Pontificia Facoltà Teologica dell'Italia Meridionale". PFTIM.it. 7 October 2007.

- ^ "Università degli Studi Suor Orsola Benincasa – Napoli". UNISOB.na.it. 7 October 2007.

- ^ "History". SanPietroaMajella.it. 7 October 2007.

- ^ "Amministrazione Napoli". Comuni-Italiani.it. 8 January 2008.

- ^ "Euromonitor Internationals Top City Destinations Ranking > Euromonitor archive". Euromonitor.com. 2008-12-12. Retrieved 2010-03-28.

- ^ a b c d "Rapporto sullo stato dell'economia della Provincia di Napoli". Istituto ISSM. 2008-01-08.

- ^ "Driving around Italy". OneStopItaly.com. 2007-06-26.

- ^ "A3". AISCAT.it. 2007-06-26.

- ^ "A16 – Autostrada dei due Mari". AISCAT.it. 2007-06-26.

- ^ a b "Naples Italy Transportation Options". GoEurope.com. 2007-06-26.

- ^ "Easy Access Transport options for persons with motion problems". Turismoaccessibile.it. 2009-06-18.

- ^ "The Naples Train Station-Napoli Centrale". RailEurope.com. 2007-06-26.

- ^ http://www.comune.napoli.it/flex/cm/pages/ServeBLOB.php/L/IT/IDPagina/8505.

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "Naples – City Insider". Marriott.co.uk. 2007-06-26.

- ^ "High Speed Rail Operations, Italy". Railway-Technology.com. 2007-06-26.

- ^ a b "Ferries from Naples". ItalyHeaven.co.uk. 2007-06-26.

- ^ "Naples International Airport" (PDF). Gesac.it. 2007-06-26.

- ^ a b "La cucina tradizionale napoletana". eat-oline.net. 24 June 2007.

- ^ "The Foods Of Sicily – A Culinary Journey". ItalianFoodForever.com. 24 June 2007.

- ^ a b c "Pizza – The Pride of Naples". HolidayCityFlash.com. 8 January 2008. Cite error: The named reference "pizza" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ "La cucina napoletana". PortaNapoli.com. 8 January 2008.

- ^ "Campania". CuciNet.com. 8 January 2008.

- ^ "Healthy treat: Napoli's Gelato serves up an Italian dessert". Topeka Capital-Journal. 8 January 2008.

- ^ "Campania – Cakes and Desserts". Emmeti.it. 8 January 2008.

- ^ "Struffoli – Neapolitan Christmas Treats". About.com. 8 January 2008.

- ^ "Lacryma Christi – A Legendary Wine". BellaOnline.com. 8 January 2008.

- ^ "Limoncello". PizzaToday.com. 8 January 2008.

- ^ "Article in Italian language of Il Denaro". Denaro.it. 2008-10-15. Retrieved 2011-03-13.

- ^ a b "Ethnologue Napoletano-Calabrese". Ethnologue.com. Retrieved 2011-03-13.

- ^ "Naples". AgendaOnline.it. 8 January 2008.

- ^ "Timeline: Opera". TimelineIndex.com. 8 January 2008.

- ^ "What is opera buffa?". ClassicalMusic.About.com. 8 January 2008.

- ^ "Teatro San Carlo". WhatsOnWhen.com. 8 January 2008.

- ^ "Vinaccia 1779". EarlyRomanticGuiar.com. 8 January 2008.

- ^ Tyler, James. The Guitar and Its Music: From the Renaissance to the Classical Era. Routledge. ISBN 019816713X.

- ^ "Cyclopaedia of Classical Guitar Composers". Cyclopaedia of Classical Guitar Composers. 8 January 2008.

- ^ "The Masters of Classical Guitar". LagunaGuitars.com. 8 January 2008.

- ^ "Starobin Plays Sor and Giuliani". FineFretted.com. 8 January 2008.

- ^ "Enrico Caruso". Encyclopædia Britannica. 8 January 2008.

- ^ "Enrico Caruso". Grandi-Tenori.com. 8 January 2008.

- ^ a b "History". FestaDiPiedigrotta.it. 8 January 2008.

- ^ "Artisti classici napoletani". NaplesMyLove.com. 8 January 2008.

- ^ "Mario Merola". Guardian.co.uk. 8 January 2008.

- ^ "Storia Del Club, by Pietro Gentile and Valerio Rossano". Napoli2000.com. 23 June 2007.

- ^ "Storia". CalcioNapoliNet.com. 26 June 2007.

- ^ "Fencing". 12 June 2008.

- ^ "Gemellaggi". Comune di Napoli. 8 January 2008.

- ^ Kagoshimais the main sister-twin city of Naples. Naples has entitled one of its streets to the Japanese city.

- ^ "Sister City – Budapest". Official website of New York City. Retrieved 2008-05-14.

- ^ "Sister cities of Budapest" (in Hungarian). Official Website of Budapest. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ^ {{cite web|url=http://www.sarajevo.ba/en/stream.php?kat=147%7Ctitle=Fraternity cities on Sarajevo Official Web Site|publisher=© City of Sarajevo 2001–2008|accessdate=2008-11-09}}