Sallekhana: Difference between revisions

restoring content removed without consensus |

|||

| Line 44: | Line 44: | ||

== Misconceptions == |

== Misconceptions == |

||

Jain texts make a clear distinction between the ''sallekhanā'' vow and suicide.<ref>{{citation|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=qsGXnA8RfgwC&pg=PA102|title=Nonviolence to Animals, Earth, and Self in Asian Traditions|author=Christopher Chapple|publisher=|p=102|isbn=0791498778|date=1993-01-01}}</ref> According to Jain text, Puruṣārthasiddhyupāya: {{quote|"When death is imminent, the vow of ''sallekhanā'' is observed by progressively slenderizing the body and the passions. Since the person observing ''sallekhanā'' is devoid of all passions like attachment, it is not suicide.|''[[Puruşārthasiddhyupāya]]'' (117){{sfn|Vijay K. Jain|2012|p=115}}}} |

Jain texts make a clear distinction between the ''sallekhanā'' vow and other forms of suicide.<ref>{{citation|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=qsGXnA8RfgwC&pg=PA102|title=Nonviolence to Animals, Earth, and Self in Asian Traditions|author=Christopher Chapple|publisher=|p=102|isbn=0791498778|date=1993-01-01}}</ref> According to Jain text, Puruṣārthasiddhyupāya: {{quote|"When death is imminent, the vow of ''sallekhanā'' is observed by progressively slenderizing the body and the passions. Since the person observing ''sallekhanā'' is devoid of all passions like attachment, it is not suicide.|''[[Puruşārthasiddhyupāya]]'' (117){{sfn|Vijay K. Jain|2012|p=115}}}} |

||

In the practice of Sallekhanā, it is viewed that death is "welcomed" through a peaceful, tranquil process that provides peace of mind and sufficient closure for the adherent, their family and/or community.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.omc.ca/omni/archives/000036.html |title=Sallekhanā versus Suicide |publisher=Omni Journal of Spiritual and Religious Care |accessdate=2007-02-18 |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/20120507140804/http://www.omc.ca:80/omni/archives/000036.html |archivedate=7 May 2012 }}</ref> |

In the practice of Sallekhanā, it is viewed that death is "welcomed" through a peaceful, tranquil process that provides peace of mind and sufficient closure for the adherent, their family and/or community.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.omc.ca/omni/archives/000036.html |title=Sallekhanā versus Suicide |publisher=Omni Journal of Spiritual and Religious Care |accessdate=2007-02-18 |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/20120507140804/http://www.omc.ca:80/omni/archives/000036.html |archivedate=7 May 2012 }}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 11:00, 12 February 2016

| Part of a series on |

| Jainism |

|---|

|

| Suicide |

|---|

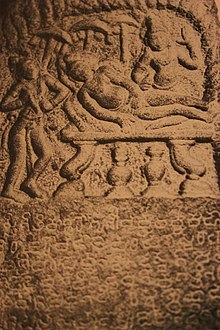

In Jainism, Sallekhanā (also Santhara, Samadhi-marana, Sanyasana-marana) is a vow (vrata) observed by the Jain ascetics and lay votaries at the end of their life.[note 1] The vow is observed by gradually reducing the intake of food and liquids.[1][2][3] Sallekhanā is allowed when normal life according to religion is not possible due to old age, incurable disease or when a person is nearing his end.[3][4] It is a highly respected practice among the members of the Jain community.[5] According to Jain texts, sallekhanā leads to ahimsā (non-violence or non-injury), as a person observing sallekhanā subjugates the passions, which are the root cause of hiṃsā (injury or violence).[6] In 2015, Rajasthan High Court banned the practice calling it suicide. On 31 August 2015, Supreme Court of India stayed the decision of Rajasthan High Court and lifted the ban on sallekhana.[7]

Overview

Sallekhanā is made up from two words sal (meaning 'properly') and lekhana, which means to thin out. Properly thinning out of the passions and the body is sallekhanā.[8] Sallekhanā is prescribed both for the householders (śrāvakas) and the ascetics.[9] In Jainism, both ascetics and householders have to follow five fundamental vows (vratas). Ascetics must observe complete abstinence and their vows are thus called Mahavratas (major vows). The vows of the laity (who observe partial abstinence) are called anuvratas (minor vows).[10] Jain ethical code also prescribe seven supplementary vows, which include three guņa vratas and four śikşā vratas.[11]

An ascetic or householder who has observed all the vows prescribed to shed the karmas, takes the vow of Sallekhanā at the end of his life.[12] According to the Jain text, Purushartha Siddhyupaya, "sallekhanā enable a householder to carry with him his wealth of piety".[13] Sallekhanā is treated as a supplementary to the twelve vows taken by Jains. However, some Jain Acharyas such as Kundakunda, Devasena, Padmanandin and Vasunandin have included it under the last vow, śikşā-vrata.[14]

The vow of sallekhanā is often explained with a famous analogy:[15]

A merchant stores commodities for sale and stores them. He does not welcome the destruction of his storehouse. The destruction of the storehouse is against his wish and when some danger threatens the storehouse, he tries to safeguard it. But if he cannot stop the danger, he tries to save the commodities at least from ruin. Similarly, a householder is engaged in acquiring the commodity of vows and supplementary vows. And he does not desire the ruin of the receptacle of these virtues, namely the body. But when serious danger threatens the body, he tries to avert it in a righteous manner without violating his vows. In case it is not possible to avert danger to the body, he tries to safeguard his vows at least.[16]

Sallekhanā is divided into two:[17]

- Kashaya sallekhanā (slenderising of passions) or abhayantra (internal)

- Kaya sallekhanā (slenderising the body) or bāhya (external)

Procedure

According to Tattvartha Sutra (a compendium of Jain principles): "A householder willingly or voluntary adopts Sallekhanā when death is very near."[18][19] Observance of the vow of sallekhanā starts much before the approach of death. A householder persistently meditate on the verse: "I shall certainly, at the approach of death, observe sallekhanā in the proper manner."[20] The duration of the practice could be up to twelve years or more.[21] Sixth part of the Jain text, Ratnakaranda śrāvakācāra is on sallekhanā and its procedure.[22]

Jain texts mention five transgressions of the vow of sallekhanā:[19][23]-

- desire to live

- desire to die

- recollection of affection for friends

- recollection of the pleasures enjoyed

- longing for the enjoyment of pleasures in future

The person observing sallekhanā does not wish to die nor he is aspiring to live in a state of inability where he/ she can't undertake his/ her own chores. Due to the prolonged nature of sallekhanā, the individual is given ample time to reflect on his or her life. The purpose is to purge old karmas and prevent the creation of new ones.[24] The vow of Sallekhana can not be taken by a lay person on his own without being permitted by a monk.[25]

In Practice

According to a survey conducted in 2006, on an average 200 Jains practice sallekhanā until death each year in India.[26] Statistically, Sallekhanā is undertaken both by men and women of all economic classes and among the educationally forward Jains. In 1999, Acharya Vidyanand, a prominent Digambara monk took a twelve year long vow of sallekhanā.[27]

Historical examples

In around 300 BC, Chandragupta Maurya (founder of the Maurya Empire) undertook Sallekhanā atop Chandragiri Hill, Śravaṇa Beḷgoḷa, Karnataka.[28][29][30] Chandragupta basadi at Shravanabelagola (a chief seat of the Jains) marks the place where the saint Chandragupta died.[31] Acharya Shantisagar, a highly revered Digambara monk of the modern India took Sallekana on 18 August 1955 because of inability to walk without help and weak eye-sight.[32][33] He died on 18 September 1955.[34]

Misconceptions

Jain texts make a clear distinction between the sallekhanā vow and other forms of suicide.[35] According to Jain text, Puruṣārthasiddhyupāya:

"When death is imminent, the vow of sallekhanā is observed by progressively slenderizing the body and the passions. Since the person observing sallekhanā is devoid of all passions like attachment, it is not suicide.

— Puruşārthasiddhyupāya (117)[20]

In the practice of Sallekhanā, it is viewed that death is "welcomed" through a peaceful, tranquil process that provides peace of mind and sufficient closure for the adherent, their family and/or community.[36]

In both the writings of Jain Agamas and the general views of many followers of Jainism, due to the degree of self-actualisation and spiritual strength required by those who undertake the ritual, Sallekhanā is considered to be a display of utmost piety, purification and expiation.[37]

In his book, Sallekhanā is Not Suicide, Justice T. K. Tukol wrote:[38]

My studies of Jurisprudence, the Indian Penal Code and of criminal cases decided by me had convinced that the vow of Sallekhanā as propounded in the Jaina scriptures is not suicide.

According to Champat Rai Jain, "The true idea of sallekhanā is only this that when death does appear at last, one should know how to die, that is, one should die like a monk, not like a beast, bellowing and panting and making vain efforts to avoid, the unavoidable."[39][40]

According to advocate, Suhrith parthasarathy, "Sallekhanā is not an exercise in trying to achieve an unnatural death, but is rather a practice intrinsic to a person’s ethical choice to live with dignity until death".[41]

Legality

In 2006, human rights activist Nikhil Soni and his lawyer Madhav Mishra filed a Public Interest Litigation with the Rajasthan High Court. The PIL claimed that Sallekhanā should be considered to be suicide under the Indian legal statute. They argued that Article 21 of the Indian constitution only guarantees the right to life, but not to death.[42] The petition extends to those who facilitate individuals taking the vow of with aiding and abetting an act of suicide. In response, the Jain community argued that it is a violation of the Indian Constitution’s guarantee of religious freedom.[43] It was argued that Sallekhanā serves as a means of coercing widows and elderly relatives into taking their own lives.[44]

This landmark case sparked debate in India, where national bioethical guidelines have been in place since 1980.[45]

In August 2015, the Rajasthan High Court stated that the practice is not an essential tenet of Jainism and banned the practice making it punishable under section 306 and 309 (Abetment of Suicide) of the Indian Penal Code.[46]

On 24 August 2015, members of the Jain community held a peaceful nationwide protest against the ban on Santhara.[47] Protests were held in various states like Rajasthan, Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Delhi etc.[48] Silent march were carried out in various cities.[49]

On 31 August 2015, Supreme Court of India stayed the decision of Rajasthan High Court and lifted the ban on santhara.[7] The Special Leave Petition brought before the Supreme Court of India was filed by Akhil Bharat Varshiya Digambar Jain Parishad.[50][51] Supreme court considered Santhara as a component of non-violence ('ahimsa').[52]

See also

Notes

- ^ Vrata means performance of any ritual voluntarily over a particular period of time.

Citations

- ^ Wiley 2009, p. 181.

- ^ Battin 2015, p. 47.

- ^ a b Tukol 1976, p. 7.

- ^ Jaini 2000, p. 16.

- ^ Kakar 2014, p. 173.

- ^ Vijay K. Jain 2012, p. 116.

- ^ a b Ghatwai, Milind (2 September 2015), "The Jain religion and the right to die by Santhara", The Indian Express

- ^ Kakar 2014, p. 174.

- ^ Tukol 1976, p. 8.

- ^ Tukol 1976, p. 4.

- ^ Vijay K. Jain 2012, p. 87.

- ^ Tukol 1976, p. 5.

- ^ Vijay K. Jain 2012, p. 114.

- ^ Williams, Robert (1991), Jaina Yoga: A Survey of the Mediaeval Śrāvakācāras, Motilal Banarsidass, p. 166, ISBN 978-81-208-0775-4

- ^ S.A. Jain 1992, p. 242-243.

- ^ Vijay K. Jain 2012, p. 117.

- ^ Settar 1989, p. 113.

- ^ Vijay K. Jain 2011, p. 102.

- ^ a b Tukol 1976, p. 10.

- ^ a b Vijay K. Jain 2012, p. 115.

- ^ "Doc firm on Santhara despite HC ban: I too want a beautiful death". The Indian Express.

- ^ Jain, Champat Rai (1917), "The Ratna Karanda Sravakachara", Internet Archive, The Central Jaina Publishing House, pp. 58–64

- ^ Vijay K. Jain 2011, p. 111.

- ^ Sallekhanā, jainworld.com

- ^ Jaini 1998, p. 231.

- ^ "'Over 200 Jains embrace death every year'", Express India, 30 September 2006

- ^ Gel, Peter Fl; Flügel, Peter (1 February 2006). Studies in Jaina History and Culture. ISBN 9781134235520.

- ^ Tukol 1976, p. 19-20.

- ^ Sebastian, Pradeep, "The nun's tale", The Hindu

- ^ "On a spiritual quest", Deccan Herald, 29 March 2015

- ^ Rice 1889, p. 17-18.

- ^ Tukol 1976, p. 98.

- ^ Tukol 1976, p. 100.

- ^ Tukol 1976, p. 104.

- ^ Christopher Chapple (1 January 1993), Nonviolence to Animals, Earth, and Self in Asian Traditions, p. 102, ISBN 0791498778

- ^ "Sallekhanā versus Suicide". Omni Journal of Spiritual and Religious Care. Archived from the original on 7 May 2012. Retrieved 18 February 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Is the Jain practice of Santhara about Right to Life or Death? - Latest News & Updates at Daily News & Analysis". dna. 12 July 2015. Retrieved 10 August 2015.

- ^ Tukol 1976, p. Preface.

- ^ Champat Rai Jain 1934, p. 179.

- ^ Tukol 1976, p. 90.

- ^ PARTHASARATHY, SUHRITH (24 August 2015). "The flawed reasoning in the Santhara ban". THE HINDU. Retrieved 25 August 2015.

- ^ "Religions: Jainism: Fasting". BBC. 10 September 2009. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- ^ See Nikhil Soni v. Union of India and Ors. AIR (2006) Raj 7414.

- ^ Braun, W (2008). "Sallekhanā: The ethicality and legality of religious suicide by starvation in the Jain religious community". Medicine and law. 27 (4): 913–24. PMID 19202863.

- ^ Kumar, Nandini K. (2006). "Bioethics activities in India". Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal. 12 (Suppl 1): S56–65. PMID 17037690.

- ^ "Rajasthan HC bans starvation ritual 'Santhara', says fasting unto death not essential tenet of Jainism". IBNlive. 10 August 2015. Retrieved 10 August 2015.

- ^ "Jain community protests ban on religious fast to death". Yahoo News India. 24 August 2015.

- ^ "Jains protest against Santhara order". The Indian EXPRESS. 25 August 2015. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- ^ "Silent march by Jains against Rajasthan High Court order on 'Santhara'". timesofindia-economictimes.

- ^ "Supreme Court stays Rajasthan High Court order declaring 'Santhara' illegal". The Indian EXPRESS.

- ^ SC allows Jains to fast unto death, Deccan Herald, 31 August 2015

- ^ Rajagopal, Krishnadas (1 September 2015). "Supreme Court lifts stay on Santhara ritual of Jains". THE HINDU. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

References

- Battin, Margaret Pabst (11 September 2015), The Ethics of Suicide: Historical Sources, ISBN 9780199385829

- Kakar, Sudhir (2014), "A Jain Tradition of Liberating the Soul by Fasting Oneself", Death and Dying, Penguin UK, ISBN 9789351187974

- Jain, Vijay K. (2012), Acharya Amritchandra's Purushartha Siddhyupaya, Vikalp Printers, ISBN 81-903639-4-8,

Non-Copyright

- Jain, Vijay K. (2011), Acharya Umasvami's Tattvārthsūtra, Vikalp Printers, ISBN 978-81-903639-2-1,

Non-Copyright

- Wiley, Kristi L (16 July 2009), The a to Z of Jainism, ISBN 9780810868212

- Jaini, Padmanabh S. (2000), Collected Papers on Jaina Studies, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 81-208-1691-9

- S.A. Jain (1992), Reality (Second ed.), Jwalamalini Trust,

Non-Copyright

- Settar, S (1989), Inviting Death, ISBN 9004087907

- Jaini, Padmanabh S. (1998) [1979], The Jaina Path of Purification, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 81-208-1578-5

- Tukol, Justice T. K. (1976), Sallekhanā is Not Suicide (1st ed.), Ahmedabad: L.D. Institute of Indology

- Jain, Champat (1934), Jainism and World Problems: Essays and Addresses, Jaina Parishad

- Rice, B. Lewis (1889), Inscriptions at Sravana Belgola: a chief seat of the Jains, (Archaeological Survey of Mysore), Bangalore : Mysore Govt. Central Press