Lorazepam: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by 99.145.17.206 (talk) to last version by Casliber |

What's your objection to using the correct medical term? |

||

| Line 90: | Line 90: | ||

* '''[[Myasthenia gravis]].''' This condition is characterised by muscle weakness and a muscle relaxant such as lorazepam may exacerbate symptoms. |

* '''[[Myasthenia gravis]].''' This condition is characterised by muscle weakness and a muscle relaxant such as lorazepam may exacerbate symptoms. |

||

* '''[[Pregnancy]] and [[breast feeding]].''' Lorazepam belongs to the [[Food and Drug Administration]] (FDA) pregnancy category D which means that it is likely to cause harm to the |

* '''[[Pregnancy]] and [[breast feeding]].''' Lorazepam belongs to the [[Food and Drug Administration]] (FDA) pregnancy category D which means that it is likely to cause harm to the fetus if taken during the first trimester of pregnancy. There is inconclusive evidence that lorazepam if taken early in pregnancy may result in reduced IQ, neurodevelopmental problems, physical malformations in cardiac or facial structure as well as other malformations in some newborns. Lorazepam given to pregnant women antenatally may cause [[hypotonia|floppy infant syndrome]]<ref>{{cite journal | author = Kanto JH. | coauthors = | year = 1982 | month = May | title = Use of benzodiazepines during pregnancy, labour and lactation, with particular reference to pharmacokinetic considerations | journal = Drugs. | volume = 23 | issue = 5 | pages = 354–80 | pmid = 6124415 | doi = 10.2165/00003495-198223050-00002}}</ref> in the neonate, or respiratory depression necessitating ventilation. Regular lorazepam use during late pregnancy (the [[third trimester]]), carries a definite risk of [[benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome]] in the neonate. Neonatal benzodiazepine withdrawal may include [[hypotonia]], reluctance to suck, [[apneic]] spells, [[cyanosis]], and impaired [[metabolic]] responses to cold stress. Symptoms of floppy infant syndrome and the neonatal benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome have been reported to persist from hours to months after birth.<ref>{{cite journal | author = McElhatton PR. | coauthors = | year = 1994 | month = Nov-Dec | title = The effects of benzodiazepine use during pregnancy and lactation | journal = Reprod Toxicol. | volume = 8 | issue = 6 | pages = 461–75 | pmid = 7881198 | doi = 10.1016/0890-6238(94)90029-9}}</ref> Lorazepam may also inhibit foetal liver bilirubin glucuronidation, leading to neonatal jaundice. Lorazepam is present in breast milk; so caution must be exercised about breast feeding. |

||

==== Special groups and situations ==== |

==== Special groups and situations ==== |

||

Revision as of 17:55, 28 March 2009

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Routes of administration | Oral, I.M., I.V. and transdermal |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 85% of oral dose |

| Metabolism | Hepatic glucuronidation |

| Elimination half-life | 9–16 hours[2][3][4] |

| Excretion | Renal |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.011.534 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

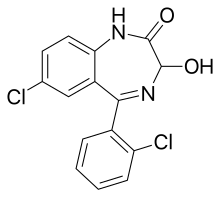

| Formula | C15H10Cl2N2O2 |

| Molar mass | 321.2 g/mol g·mol−1 |

Lorazepam, initially marketed under the brand names Ativan and Temesta, is a benzodiazepine drug with short to medium duration of action. It has all five intrinsic benzodiazepine effects: anxiolytic, amnesic, sedative/hypnotic, anticonvulsant and muscle relaxant.[5] It is a powerful anxiolytic and since its introduction in 1971, lorazepam's principal use has been in treating the symptom of anxiety. It is a unique benzodiazepine insofar as it has also found use as an adjunct antiemetic in chemotherapy. Among benzodiazepines, lorazepam has a relatively high addictive potential.[6]

Uses

Lorazepam has relatively potent anxiolytic effects and its best known indication is the short-term management of severe anxiety. It is less useful in panic disorder.[7]

Lorazepam has strong sedative/hypnotic effects, and the duration of clinical effects from a single dose makes it an appropriate choice for the short term treatment of insomnia, particularly in the presence of severe anxiety. Withdrawal symptoms, including rebound insomnia and rebound anxiety, may occur after only 7 days' administration of lorazepam.[8]

Its relatively potent amnesic effect,[5] with its anxiolytic and sedative effects, makes lorazepam useful as premedication. It is given before a general anaesthetic to reduce the amount of anaesthetic agent required, or before unpleasant awake procedures, such as dentistry or endoscopies, to reduce anxiety, increase compliance and induce amnesia for the procedure. Oral lorazepam is given 90- to 120 minutes before procedures and intravenous lorazepam as late as 10 minutes before procedures.[9][10][11]

The marked anticonvulsant properties of lorazepam, and its pharmacokinetic profile, makes intravenous lorazepam a reliable agent for terminating acute seizures, but it has relatively prolonged sedation aftereffects. Oral lorazepam, and other benzodiazepines, have a role in long-term prophylactic treatment of resistant forms of petit mal epilepsy but not as first-line therapies, mainly because of the development of resistance to their effects.[12]

Lorazepam's anticonvulsant, or CNS depressant, properties are useful for the prevention and treatment of alcohol withdrawal syndrome. In this setting it is relevant that impaired liver function is not a hazard with lorazepam since lorazepam does not require oxidation, hepatic or otherwise, for its metabolism.[13][14]

Where there is need for rapid sedation of violent or agitated patients,[15][16] including acute delirium, lorazepam may be used, but as it can cause paradoxical effects, it is preferably given together with haloperidol.[17] Lorazepam is absorbed relatively slowly if given intramuscularly, a common route in restraint situations.

Catatonia with inability to speak is responsive and sometimes controlled with a single 2 mg oral, or slow intravenous, dose of lorazepam. Symptoms may recur and treatment for some days may be necessary. Catatonia due to abrupt or too rapid withdrawal from benzodiazepines, as part of the benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome, should also respond to lorazepam treatment.[18] As lorazepam can have paradoxical effects, haloperidol is sometimes given concomitantly.[17][19]

Lorazepam is unique among benzodiazepines in having potent antiemetic properties. It is used as an adjunct antiemetic for treating the nausea and vomiting frequently associated with cancer chemotherapy, usually together with first-line antiemetics such as 5-HT3 antagonists.[20] It is also used as adjunct therapy for cyclic vomiting syndrome.

Formulation and administration

Pure lorazepam is an almost white powder that is nearly insoluble in water and oil. In medicinal form, lorazepam is mainly available as tablets and a solution for injection but in some locations it is also available as a skin patch, an oral solution and a sublingual tablet.

Lorazepam tablets and syrups are administered by mouth only. The tablets contain 0.5 mg, 1 mg, or 2 mg lorazepam, with some differences between countries. Lorazepam tablets of the Ativan brand also contain lactose, microcrystalline cellulose, polacrilin potassium, magnesium stearate and colouring agents (Blue tablets: indigo carmine, E132; Yellow tablets: tartrazine, E102).

Lorazepam injectable solution is administered either by deep intramuscular injection or by intravenous injection. The injectable solution comes in 1 mL ampoules containing 2 mg or 4 mg lorazepam. The solvents used are polyethylene glycol 400 and propylene glycol. As a preservative, the injectable solution contains benzyl alcohol.[21] Toxicity from propylene glycol has been reported in the case of a patient receiving a continuous lorazepam infusion.[22] Intravenous injections should be given slowly and patients closely monitored for side-effects, such as respiratory depression, hypotension or loss of airway control.

Peak effects roughly coincide with peak serum levels,[23] which occur 10 minutes after intravenous injection, up to 60 minutes after intramuscular injection and 90 to 120 minutes after oral administration,[23][24] but initial effects will be noted before this. A clinically relevant lorazepam dose will normally be effective for 6 to 12 hours, making it unsuitable for regular once-daily administration, so it is usually prescribed as two to four daily doses when taken regularly.

Pharmacology

Lorazepam is high potency and an intermediate acting benzodiazepine and its uniqueness,[25][26] advantages and disadvantages are largely explained by its pharmacokinetic properties (poor water and lipid solubility, high protein binding and non-oxidative metabolism to a pharmacologically inactive glucuronide form) and by its high relative potency (lorazepam 1 mg is equal in effect to diazepam 10 mg).[27][28] The half life of lorazepam is 10–20 hours.[29]

Pharmacokinetics

Because of its poor lipid solubility lorazepam is absorbed relatively slowly by mouth and is unsuitable for rectal administration. But its poor lipid solubility and high degree of protein binding (85-90%[24]) mean that lorazepam's volume of distribution is mainly the vascular compartment, causing relatively prolonged peak effects. This contrasts with the highly lipid soluble diazepam which, although rapidly absorbed orally or rectally, soon redistributes from the serum to other parts of the body, particularly body fat. This explains why one lorazepam dose, despite lorazepam's shorter serum half-life, has more prolonged peak effects than an equivalent diazepam dose.[30] On regular administration diazepam will however accumulate more, since it has a longer half-life and active metabolites with even longer half-lives.

- Clinical Example: Diazepam has long been a drug of choice for status epilepticus: its high lipid solubility means it gets absorbed with equal speed whether given intravenously, orally or rectally (non-intravenous routes are convenient in non-hospital settings). But diazepam's high lipid solubility also means it does not remain in the vascular space but soon redistributes into other body tissues. So it may be necessary to repeat diazepam doses to maintain peak anticonvulsant effects, resulting in excess body accumulation. Lorazepam is the opposite case: its low lipid solubility makes it relatively slowly absorbed by any route other than intravenously, but once injected will not get significantly redistributed beyond the vascular space. Therefore, lorazepam's anticonvulsant effects are more durable, thus reducing the need for repeated doses. If a patient is known to usually stop convulsing after only one or two diazepam doses, diazepam may be preferable because sedative after-effects will be less than if a single dose of lorazepam is given (diazepam anticonvulsant/sedative effects wear off after 15–30 minutes, but lorazepam effects last 12–24 hours).[31] The prolonged sedation from lorazepam may however be an acceptable trade-off for its reliable duration of effects, particularly if the patient needs to be transferred to another facility. Although lorazepam is not necessarily better than diazepam at initially terminating seizures,[32] lorazepam is nevertheless replacing diazepam as the intravenous agent of choice in status epilepticus.[33][34]

Lorazepam serum levels are proportional to the dose administered. Giving 2 mg oral lorazepam will result in a peak total serum lorazepam level of around 20 nanograms/ml around two hours later,[23][24] half of which is lorazepam, half its inactive metabolite, lorazepam-glucuronide.[35] A similar lorazepam dose given intravenously will result in an earlier and higher peak serum level, with a higher relative proportion of unmetabolised (active) lorazepam.[36] On regular administration, maximum lorazepam serum levels are attained after three days. Longer term use, up to six months, does not result in further accumulation.[24] On discontinuation, lorazepam serum levels become negligible after 3 days and undetectable after about a week. Lorazepam is metabolised in the liver by conjugation into inactive lorazepam-glucuronide. This metabolism does not involve hepatic oxidation and therefore is relatively unaffected by reduced liver function. Lorazepam-glucuronide is more water-soluble than its precursor and therefore gets more widely distributed in the body leading to a longer half-life than lorazepam. Lorazepam-glucuronide is eventually excreted by the kidneys[24] and because of its tissue accummulation it remains detectable - particularly in the urine - for substantially longer than lorazepam.

Pharmacodynamics

Relative to other benzodiazepines, lorazepam is thought to have high affinity for GABA receptors,[37] which may also explain its marked[5] amnesic effects. The main pharmacological effects of lorazepam are the enhancement of GABA at the GABAA receptor.[38] Benzodiazepine drugs including lorazepam increase the inhibitory processes in the cerebral cortex.[39]

The magnitude and duration of lorazepam effects are dose related, meaning that larger doses have stronger and longer-lasting effects. This is because the brain has spare benzodiazepine drug receptor capacity, with single, clinical doses leading only to an occupancy of some 3% of the available receptors.[40]

The anticonvulsant properties of lorazepam and other benzodiazepines may be, in part or entirely, due to binding to voltage-dependent sodium channels rather than benzodiazepine receptors. Sustained repetitive firing seems to get limited, by the benzodiazepine effect of slowing recovery of sodium channels from inactivation in mouse spinal cord cell cultures.[41]

Contraindications and special considerations

Contraindications

Lorazepam must be avoided in patients with the following conditions:

- Allergy or hypersensitivity. Past hypersensitivity or allergy to lorazepam, to any benzodiazepine or to any of the ingredients in lorazepam tablets or injections.

- Severe respiratory failure. Benzodiazepines, including lorazepam, may depress central nervous system respiratory drive and are contraindicated in severe respiratory failure. An example would be the inappropriate use to relieve anxiety associated with acute severe asthma. The anxiolytic effects may also be detrimental to a patient's willingness and ability to fight for breath. However, if mechanical ventilation becomes necessary, lorazepam may be used to facilitate deep sedation.

- Acute intoxication. Lorazepam may interact synergistically with the effects of alcohol, narcotics, or other psychoactive substances. It should therefore not be administered to a drunk or intoxicated person.

- Ataxia. This is a neurological clinical sign, consisting of unsteady and clumsy motion of the limbs and torso, due to failure of gross muscle movement coordination, most evident on standing and walking: it is the classic way in which acute alcohol intoxication may affect a person. Benzodiazepines should not be administered to already ataxic patients.

- Acute narrow-angle glaucoma. Lorazepam has pupil-dilating effects which may further interfere with the drainage of aqueous humour from the anterior chamber of the eye, thus worsening narrow-angle glaucoma.

- Sleep apnea. Sleep apnea may be worsened by lorazepam's central nervous system depressant effects. It may further reduce the patient's ability to protect his or her airway during sleep.

- Myasthenia gravis. This condition is characterised by muscle weakness and a muscle relaxant such as lorazepam may exacerbate symptoms.

- Pregnancy and breast feeding. Lorazepam belongs to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) pregnancy category D which means that it is likely to cause harm to the fetus if taken during the first trimester of pregnancy. There is inconclusive evidence that lorazepam if taken early in pregnancy may result in reduced IQ, neurodevelopmental problems, physical malformations in cardiac or facial structure as well as other malformations in some newborns. Lorazepam given to pregnant women antenatally may cause floppy infant syndrome[42] in the neonate, or respiratory depression necessitating ventilation. Regular lorazepam use during late pregnancy (the third trimester), carries a definite risk of benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome in the neonate. Neonatal benzodiazepine withdrawal may include hypotonia, reluctance to suck, apneic spells, cyanosis, and impaired metabolic responses to cold stress. Symptoms of floppy infant syndrome and the neonatal benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome have been reported to persist from hours to months after birth.[43] Lorazepam may also inhibit foetal liver bilirubin glucuronidation, leading to neonatal jaundice. Lorazepam is present in breast milk; so caution must be exercised about breast feeding.

Special groups and situations

- Children and the elderly. The safety and effectiveness of lorazepam is not well determined in children under 16 years of age, but it is used to treat serial seizures. Dose requirements have to be individualized, especially in the elderly and debilitated patients in whom the risk of oversedation is greater. Long-term therapy may lead to cognitive deficits, especially in the elderly, but this is reversible after a period of discontinuation. Benzodiazepines, including lorazepam, have been found to increase the risk of falls and fractures in the elderly.[44]

- Liver or Kidney failure. Lorazepam may be safer than most benzodiazepines in patients with impaired liver function. Like oxazepam it does not require hepatic oxidation, but only hepatic glucuronidation into lorazepam-glucuronide. Therefore, impaired liver function is unlikely to result in lorazepam accumulation to an extent causing adverse reactions.[13] Lorazepam-glucuronide and a small amount of unchanged lorazepam are excreted by the kidneys, so in renal failure small increases in lorazepam levels may theoretically occur.

- Surgical Premedication. Informed consent which was given only after receiving lorazepam premedication could have its validity challenged later. Staff must use chaperones to guard against allegations of abuse during treatment. Such allegations may arise because of incomplete amnesia, disinhibition, and impaired ability to process cues. Because of its relative long duration of residual effects (sedation, ataxia, hypotension and amnesia) lorazepam premedication is best suited for hospital inpatient use. Patients should not be discharged from hospital within 24 hours of receiving lorazepam premedication, unless accompanied by a caregiver. They should also not drive, operate machinery or use alcohol within this period.

Tolerance and dependence

Tolerance to benzodiazepine effects develops with regular use. This is desirable with amnesic and sedative effects, undesirable with anxiolytic, hypnotic and anticonvulsant effects. Patients at first experience drastic relief from anxiety and sleeplessness, but symptoms gradually return, relatively soon in the case of insomnia but more slowly in the case of anxiety symptoms. After four to six months of regular benzodiazepine use, there is little evidence of continued efficacy. If regular treatment is continued for longer than this, dose increases may be necessary to maintain effects, but treatment resistant symptoms may in fact be benzodiazepine withdrawal symptoms.[45]

On abrupt, or overly rapid discontinuation of lorazepam, anxiety and signs of physical withdrawal have been observed, similar to those seen on withdrawal from alcohol and barbiturates. Lorazepam as with other benzodiazepine drugs can cause physical dependence, addiction and what is known as the benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome. The higher the dose and the longer the drug is taken for the greater the risk of experiencing unpleasant withdrawal symptoms. Withdrawal symptoms can however occur from standard dosages and also after short term use. Benzodiazepine treatment should be discontinued as soon as possible via a slow and gradual dose reduction regime.[46]

The likelihood of dependence is relatively high with lorazepam compared to other benzodiazepines. Lorazepam's relatively short serum half-life, its confinement mainly to the vascular space and its inactive metabolite results in interdose withdrawal phenomena and next dose cravings. This may reinforce psychological dependence. Because of its high potency, the smallest lorazepam tablet strength of 0.5 mg is also a significant dose reduction (in the UK, the smallest tablet strength is 1.0 mg, which further accentuates this difficulty). To minimise the risk of physical/psychological dependence, lorazepam is best used only short-term, at the smallest effective dose. If any benzodiazepine has been used long-term, the recommendation is a gradual dose taper over a period of weeks, months or longer, according to dose and duration of use, degree of dependence and the individual. Coming off long-term lorazepam may be more realistically achieved by a gradual switch to an equivalent dose of diazepam, a period of stabilization on this and only then initiating dose reductions. The advantage of switching to diazepam is that dose reductions are felt less acutely, because of the longer half lives (20-200 hours) of diazepam and its active metabolites.[47]

Withdrawal

Withdrawal symptoms can occur after taking therapeutic doses of Ativan for as little as one week. Withdrawal symptoms include headaches, anxiety, tension, depression, insomnia, restlessness, confusion, irritability, sweating, dysphoria, dizziness, derealization, depersonalization, numbness/tingling of extremities, hypersensitivity to light, sound, and smell, perceptual distortions, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, appetite loss, hallucinations, delirium, seizures, tremor, stomach cramps, myalgia, agitation, palpitations, tachycardia, panic attacks, short-term memory loss, and hyperthermia. It takes approximately 18–36 hours for the benzodiazepine to remove itself from your body.[48] The ease of addiction to Lorazepam, (the Ativan brand was particularly cited), and its withdrawal were brought to the attention of the British public during the early 1980s in Esther Rantzen's BBC TV series "That's Life", in a feature on the drug over a number of episodes.

Abuse and misuse

Lorazepam is a drug with the potential for misuse. Two types of drug misuse can occur either recreational misuse is where the drug is taken to achieve a high or when the drug is continued long term against medical advice.[49] Prescribers of lorazepam must be alert to the possibility of abuse or diversion for illegitimate use when prescribing for unsupervised outpatients. This applies particularly to patients with past or present substance abuse disorders, as persons with addictive personalities are more likely to abuse medications such as lorazepam. In addition to recreational use, benzodiazepines may be diverted and used to facilitate crime: criminals may take them to deliberately seek disinhibition before committing crimes[50] (which increases their potential for violence) or they may give them to unwitting victims as date rape drugs, notably with alcohol.

In Northern Ireland in cases where drivers had low or no alcohol readings but were thought to be impaired through drugs, benzodiazepines were found to be present in 87% of cases.[51]

A large-scale, nationwide, U.S. government study of pharmaceutical-related ED visits by SAMHSA found that sedative-hypnotics in the United States are the most frequently abused pharmaceuticals, with 35% of drug-related emergency room visits involving sedative-hypnotics. In this category benzodiazepines are most commonly abused. Males abuse benzodiazepines as commonly as women. Of drugs used in attempted suicide, benzodiazepines are the most commonly used pharmaceutical drug, with 26% of attempted suicides involving benzodiazepines. Lorazepam was the third most commonly abused benzodiazepine in these ED visit statistics.[52]

Adverse effects

Any of the five intrinsic benzodiazepine effects possessed by lorazepam (sedative/hypnotic, muscle relaxant, anxiolytic, amnesic and anticonvulsant) may be considered as "adverse effects", or "side effects", if unwanted.[5] Lorazepam's effects are dose-dependent, meaning that the higher the dose, the stronger the effects (and side effects) will be. Using the smallest dose needed to achieve desired effects lessens the risk of adverse effects.

Sedation is the most complained-of side effect. In a group of around 3500 patients treated for anxiety, the most common side-effects complained of from lorazepam were sedation (15.9%), dizziness (6.9%), weakness (4.2%), and unsteadiness (3.4%). Side-effects such as sedation and unsteadiness increased with age.[53]

- Paradoxical effects. In some cases there can be paradoxical effects with benzodiazepines, such as increased hostility, aggression, angry outbursts and Psychomotor agitation.[54] Paradoxical effects are more likely to occur with higher doses, in patients with pre-existing personality disorders and those with a psychiatric illness. It is worth noting that frustrating stimuli may trigger such reactions, even though the drug may have been prescribed to help the patient cope with such stress and frustration in the first place. As paradoxical effects appear to be dose-related, they usually subside on dose reduction or on complete withdrawal of lorazepam.[55][56][57][50][58][59]

- Suicidality. Benzodiazepines may sometimes unmask suicidal ideation in depressed patients, possibly through disinhibition or fear-reduction. Though relatively non-toxic in themselves, the concern is that benzodiazepines may inadvertently become facilitators of suicidal behaviour.[60] Lorazepam should therefore not be prescribed in high doses or as the sole treatment in depression but only together with an appropriate antidepressant.

- Amnesic effects. Among benzodiazepines, lorazepam has relatively strong amnesic effects,[5][61] but patients soon develop tolerance to this with regular use. To avoid amnesia (or excess sedation) being a problem, the initial total daily lorazepam dose should not exceed 2 mg. This also applies to use for night sedation. Five participants in a sleep study were prescribed lorazepam 4 mg at night and the next evening three subjects unexpectedly volunteered memory gaps for parts of that day, an effect which subsided completely after 2–3 days use.[62] Amnesic effects cannot be estimated from the degree of sedation present, since the two effects are unrelated.

Full lists of Lorazepam side effects:

For lists of lorazepam side-effects, refer to the manufacturers' data sheets. Please note that some may list side-effects for the entire benzodiazepine class, not the specific side-effect profile for lorazepam.

Interactions

- Alcohol. Lorazepam is not usually fatal in overdose, but may cause fatal respiratory depression if taken in overdose with alcohol. The combination also causes synergistic enhancement of the disinhibitory and amnesic effects of both drugs, with potentially embarrassing or forensic consequences. Some experts advise patients should be warned against taking alcohol while on lorazepam treatment,[5][63] but such clear warnings are not universal.[64]

Overdose

In cases of a suspected lorazepam overdose, it is important to establish if the patient is a regular user of lorazepam or other benzodiazepines, since regular use causes tolerance to develop. Also, one must ascertain if other drugs were also ingested.

Signs of overdose range through mental confusion, dysarthria, paradoxical reactions, drowsiness, hypotonia, ataxia, hypotension, hypnotic state, coma, cardiovascular depression, respiratory depression and death.

Early management of alert patients includes emetics, gastric lavage and activated charcoal. Otherwise, management is by observation, including of vital signs, support and — only if necessary, considering the hazards of doing so — giving intravenous flumazenil.

Patients are ideally nursed in a kind, non-frustrating environment since, when given or taken in high doses, benzodiazepines are more likely to cause paradoxical reactions. If shown sympathy, even quite crudely feigned, patients may respond solicitously, but they may respond with disproportionate aggression to frustrating cues.[65] Opportunistic counseling has limited value here, as the patient is unlikely to recall this later, owing to drug-induced anterograde amnesia.

History and legal status

Historically, lorazepam is one of the "classical" benzodiazepines. Other classical benzodiazepines include diazepam, clonazepam, oxazepam, nitrazepam, flurazepam, bromazepam and clorazepate.[66] Lorazepam was first introduced by Wyeth Pharmaceuticals in 1971 under the brand names of Ativan and Temesta.[67] The drug was developed by President of Research, D.J. Richards. Wyeth's original patent on lorazepam is expired in the United States but the drug continues to be commercially viable. As a measure of its ongoing success, it has been marketed under more than seventy generic brands since then:

Almazine, Alzapam, Anxiedin, Anxira, Anzepam, Aplacasse, Aplacassee, Apo-Lorazepam, Aripax, Azurogen, Bonatranquan, Bonton, Control, Donix, Duralozam, Efasedan, Emotion, Emotival, Idalprem, Kalmalin, Larpose, Laubeel, Lopam, Lorabenz, Loram, Lorans, Lorapam, Lorat, Lorax, Lorazene, Lorazep, Lorazepam, Lorazin, Lorafen (PL), Lorazon, Lorenin, Loridem, Lorivan, Lorsedal, Lorzem, Lozepam, Merlit, Nervistop L, Nervistopl, NIC, Novhepar, Novolorazem, Orfidal, Piralone, Placidia, Placinoral, Punktyl, Quait, Renaquil, Rocosgen, Securit, Sedarkey, Sedatival, Sedizepan, Sidenar, Silence, Sinestron, Somnium, Stapam, Tavor, Titus, Tolid, Tranqil, Tranqipam, Trapax, Trapaxm, Trapex, Upan, Wintin and Wypax.

In 2000, the U.S. drug company Mylan agreed to pay $147 million to settle accusations by the F.T.C. that they had raised the price of generic lorazepam by 2600 percent and generic clorazepate by 3200 percent in 1998 after having obtained exclusive licensing agreements for certain ingredients.[68]

Lorazepam is a Schedule IV drug under the Controlled Substances Act in the U.S. and internationally under the United Nations Convention on Psychotropic Substances.[69] Lorazepam is a Schedule IV drug under the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act in Canada. In the United Kingdom, lorazepam is a Class 4 Controlled Drug under the Misuse of Drugs Regulations 2001.

In popular culture

Lorazepam has been mentioned in several contemporary media in recent years, with various clinical aspects highlighted. It is seen in medical situations, such as the TV series House, MD as the drug of choice for the cessation of seizures. Usage for seizures is also depicted in the movie Saw III where "Jigsaw" is being operated on and begins to convulse: the character performing the surgery yells many times for Ativan, but discovers that none is available in the limited operating area. Blue October mentions Lorazepam in their song "HRSA", where it is being prescribed in a psychiatric ward for a similar use. The dependency problem is portrayed in William Gibson's 2007 book Spook Country, in which the character Milgrim is addicted to Ativan and the character Brown exploits Milgrim's addiction, in order to control him, through a steady supply of Ativan and Rize (a brand of the benzodiazepine clotiazepam). In Martin Scorsese's recent film, The Departed, Billy Costigan--an edgy, bitter, intelligent undercover cop for the Massachusetts State Police--suffers from frequent anxiety, claims to have panic attacks, and is prescribed lorazepam by a police psychologist. Blair Waldorf, of the CW's TV show Gossip Girl, mentioned Lorazepam and some other drugs in the fifth episode of the first season. In 2005, Fall Out Boy member Pete Wentz attempted to overdose on lorazepam when attempting suicide; he included references to the episode in the songs "I've Got a Dark Alley and a Bad Idea That Says You Should Shut Your Mouth (Summer Song)" and "7 Minutes in Heaven (Atavan Halen)",[70] on the album From Under the Cork Tree. In Season 6, Episode 2 of The Sopranos, Tony Soprano is also given Ativan for the seizure when he first awakes from his coma, and is subsequently kept in an induced coma using Ativan.

See also

- Benzodiazepine

- Benzodiazepine dependence

- Benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome

- Long term effects of benzodiazepines

References

- ^ "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved 22 Oct 2023.

- ^ Greenblatt DJ, Shader RI, Franke K, Maclaughlin DS, Harmatz JS, Allen MD, Werner A, Woo E (1991). "Pharmacokinetics and bioavailability of intravenous, intramuscular, and oral lorazepam in humans". J Pharm Sci. 68 (1): 57–63. doi:10.1002/jps.2600680119. PMID 31453.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Greenblatt DJ, von Moltke LL, Ehrenberg BL, Harmatz JS, Corbett KE, Wallace DW, Shader RI (2000). "Kinetics and dynamics of lorazepam during and after continuous intravenous infusion". Crit Care Med. 28 (8): 2750–2757. doi:10.1097/00003246-200008000-00011. PMID 10966246.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Papini O, da Cunha SP, da Silva Mathes Ado C, Bertucci C, Moisés EC, de Barros Duarte L, de Carvalho Cavalli R, Lanchote VL (2006). "Kinetic disposition of lorazepam with a focus on the glucuronidation capacity, transplacental transfer in parturients and racemization in biological samples" (PDF). J Pharm Biomed Anal. 40 (2): 397–403. doi:10.1016/j.jpba.2005.07.021. PMID 16143486.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f Hindmarch, Ian (January 30, 1997). "Benzodiazepines and their effects". benzo.org.uk. Retrieved 2007-05-13.

- ^ Kemper N (December 5, 1980). "[Benzodiazepine dependence: addiction potential of the benzodiazepines is greater than previously assumed (author's transl)]". Deutsche medizinische Wochenschrift (1980). 105 (49): 1707–12. PMID 7439058.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Lader M (1984). "Short-term versus long-term benzodiazepine therapy". Current Med Res Opin. 8 Suppl 4: 120–6. PMID 6144459.

- ^ Scharf MB (1982). "Lorazepam-efficacy, side effects, and rebound phenomena". Clin Pharmacol Ther. 31 (2): 175–9. PMID 6120058.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Maltais F, Laberge F, Laviolette M (1996). Template:PDFlink Chest 109 (5): 1195–8. PMID 8625666.

- ^ Heisterkamp DV, Cohen PJ (1975). "The effect of intravenous premedication with lorazepam (Ativan), pentobarbitone or diazepam on recall". Br J Anaesth. 47 (1): 79–81. doi:10.1093/bja/47.1.79. PMID 238548.

- ^ Milligan DW, Howard MR, Judd A (1987). "Premedication with lorazepam before bone marrow biopsy". J Clin Pathol. 40 (6): 696–8. doi:10.1136/jcp.40.6.696. PMID 3611398.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) PMC 1141067 - ^ Isojärvi, JI (1998). "Benzodiazepines in the treatment of epilepsy in people with intellectual disability". J Intellect Disabil Res. 42 (1): 80–92. PMID 10030438.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Peppers MP (1996). "Benzodiazepines for alcohol withdrawal in the elderly and in patients with liver disease". Pharmacotherapy. 16 (1): 49–57. PMID 8700792.

- ^ Bird RD, Makela EH (1994). "Alcohol withdrawal: what is the benzodiazepine of choice?". Ann Pharmacother. 28 (1): 67–71. PMID 8123967.

- ^ Alexander J, Tharyan P, Adams C, John T, Mol C, Philip J (2004). Template:PDFlink Br J Psychiatry 185 (1): 63–9. PMID 15231557.

- ^ McAllister-Williams RH (2005). "Intramuscular haloperidol-promethazine sedates violent or agitated patients more quickly than intramuscular lorazepam". Evidence-Based Mental Health. 8 (1): 7. PMID 15671498.

- ^ a b Bieniek SA, Ownby RL, Penalver A, Dominguez RA (1998). "A double-blind study of lorazepam versus the combination of haloperidol and lorazepam in managing agitation". Pharmacotherapy. 18 (1): 57–62. PMID 9469682.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Rosebush PI, Mazurek MF (1996). "Catatonia after benzodiazepine withdrawal". Journal of clinical psychopharmacology. 16 (4): 315–9. doi:10.1097/00004714-199608000-00007. PMID 8835707.

- ^ Van Dalfsen AN, Van Den Eede F, Van Den Bossche B, Sabbe BG (2006). "[Benzodiazepines in the treatment of catatonia]". Tijdschrift voor psychiatrie (in Dutch; Flemish). 48 (3): 235–9. PMID 16956088.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Herrstedt J, Aapro MS, Roila F, Kataja VV (2005). Template:PDFlink Ann Oncol 16 Suppl 1: i77–9. PMID 15888767. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdi805

- ^ baxter.com - Lorazepam Injection Data Sheet

- ^ Yaucher NE, Fish JT, Smith HW, Wells JA (2003). "Propylene glycol-associated renal toxicity from lorazepam infusion". Pharmacotherapy. 23 (9): 1094–9. doi:10.1592/phco.23.10.1094.32762. PMID 14524641.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Greenblatt DJ, Schillings RT, Kyriakopoulos AA, Shader RI, Sisenwine SF, Knowles JA, Ruelius HW (1976). "Clinical pharmacokinetics of lorazepam. I. Absorption and disposition of oral 14C-lorazepam". Clin Pharmacol Ther. 20 (3): 329–41. PMID 8232.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e "Lorzem Data Sheet". New Zealand Medicines and Medical Devices Safety Authority. June 4, 1999. Retrieved 2007-05-13.

- ^ Pompéia S, Manzano GM, Tufik S, Bueno OF (2005). Template:PDFlink J Physiol 569 (2): 709. PMID 16322061. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2005.569005. Letter.

- ^ Chouinard G (2004). "Issues in the clinical use of benzodiazepines: potency, withdrawal, and rebound". J Clin Psychiatry. 65 Suppl 5: 7–12. PMID 15078112.

- ^ British Medical Association and Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain (2007). British National Formulary (v53 ed.). ISBN 0-85369-731-0.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Nimmo, Ray (2007). "Benzodiazepine Equivalence Table". benzo.org.uk. Retrieved 2007-05-13.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Professor heather Ashton (2007). "Benzodiazepine equivalency table". Retrieved September 23 2007.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Funderburk FR, Griffiths RR, McLeod DR, Bigelow GE, Mackenzie A, Liebson IA, Nemeth-Coslett R (1988). "Relative abuse liability of lorazepam and diazepam: an evaluation in 'recreational' drug users". Drug and alcohol dependence. 22 (3): 215–22. doi:10.1016/0376-8716(88)90021-X. PMID 3234245.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lackner TE (2002). "Strategies for optimizing antiepileptic drug therapy in elderly people". Pharmacotherapy. 22 (3): 329–64. doi:10.1592/phco.22.5.329.33192. PMID 11898891. Free full text with registration at Medscape

- ^ Choudhery V, Townend W (2006). "Best evidence topic reports. Lorazepam or diazepam in paediatric status epilepticus". Emergency Medicine Journal. 23 (6): 472–3. doi:10.1136/emj.2006.037606. PMID 16714516.

- ^ Henry JC, Holloway R (2006). Template:PDFlink Evid Based Med 11 (2): 54. PMID 17213084. doi:10.1136/ebm.11.2.54

- ^ Cock HR, Schapira AH (2002). "A comparison of lorazepam and diazepam as initial therapy in convulsive status epilepticus". QJM. 95 (4): 225–31. doi:10.1093/qjmed/95.4.225. PMID 11937649.

- ^ Papini O, Bertucci C, da Cunha SP, dos Santos NA, Lanchote VL (2006). "Quantitative assay of lorazepam and its metabolite glucuronide by reverse-phase liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry in human plasma and urine samples". Journal of pharmaceutical and biomedical analysis. 40 (2): 389–96. doi:10.1016/j.jpba.2005.07.033. PMID 16243469.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Herman RJ, Van Pham JD, Szakacs CB (1989). "Disposition of lorazepam in human beings: enterohepatic recirculation and first-pass effect". Clin Pharmacol Ther. 46 (1): 18–25. PMID 2743706.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Matthew E, Andreason P, Pettigrew K; et al. (1995). "Benzodiazepine receptors mediate regional blood flow changes in the living human brain". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92 (7): 2775–9. doi:10.1073/pnas.92.7.2775. PMID 7708722.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) PMC 42301 - ^ Oelschläger H. (July 4, 1989). "[Chemical and pharmacologic aspects of benzodiazepines]". Schweiz Rundsch Med Prax. 78 (27–28): 766–72. PMID 2570451.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Zakusov VV (1977). "Further evidence for GABA-ergic mechanisms in the action of benzodiazepines". Archives internationales de pharmacodynamie et de thérapie. 229 (2): 313–26. PMID 23084.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Sybirska E, Seibyl JP, Bremner JD; et al. (1993). "[123I]iomazenil SPECT imaging demonstrates significant benzodiazepine receptor reserve in human and nonhuman primate brain". Neuropharmacology. 32 (7): 671–80. doi:10.1016/0028-3908(93)90080-M. PMID 8395663.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ McLean MJ (1988). "Benzodiazepines, but not beta carbolines, limit high frequency repetitive firing of action potentials of spinal cord neurons in cell culture". J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 244 (2): 789–95. PMID 2450203.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Kanto JH. (1982). "Use of benzodiazepines during pregnancy, labour and lactation, with particular reference to pharmacokinetic considerations". Drugs. 23 (5): 354–80. doi:10.2165/00003495-198223050-00002. PMID 6124415.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ McElhatton PR. (1994). "The effects of benzodiazepine use during pregnancy and lactation". Reprod Toxicol. 8 (6): 461–75. doi:10.1016/0890-6238(94)90029-9. PMID 7881198.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Trewin VF (1992). "An investigation of the association of benzodiazepines and other hypnotics with the incidence of falls in the elderly". J Clin Pharm Ther. 17 (2): 129–33. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2710.1992.tb00750.x. PMID 1349894.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Longo LP, Johnson B (2000). "Addiction: Part I. Benzodiazepines--side effects, abuse risk and alternatives". American Family Physician. 61 (7): 2121–8. PMID 10779253. Free full text

- ^ MacKinnon GL (1982). "Benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome: a literature review and evaluation". The American journal of drug and alcohol abuse. 9 (1): 19–33. doi:10.3109/00952998209002608. PMID 6133446.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Heather Ashton, C (2001). "Reasons for a diazepam (Valium) taper". benzo.org.uk. Retrieved 2007-06-01.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ FDA (2007). "Labeling Revision" (PDF). fda.gov. Retrieved 2007-10-03.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Griffiths RR, Johnson MW (2005). "Relative abuse liability of hypnotic drugs: a conceptual framework and algorithm for differentiating among compounds". J Clin Psychiatry. 66 Suppl 9: 31–41. PMID 16336040.

- ^ a b Michel L, Lang JP (2003). "[Benzodiazepines and forensic aspects]". L'Encéphale (in French). 29 (6): 479–85. PMID 15029082.

- ^ Cosbey SH. (1986). "Drugs and the impaired driver in Northern Ireland: an analytical survey". Forensic Sci Int. 32 (4): 245–58. doi:10.1016/0379-0738(86)90201-X. PMID 3804143.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ United States Government (2004). "Drug Abuse Warning Network, 2004: National Estimates of Drug-Related Emergency Department Visits". Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Retrieved 9 May 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ "Ativan side effects". RxList. 2007. Retrieved 2007-08-10.

- ^ Sorel L (1981). "Comparative trial of intravenous lorazepam and clonazepam im status epilepticus". Clin Ther. 4 (4): 326–36. PMID 6120763.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Bond A, Lader M (1988). "Differential effects of oxazepam and lorazepam on aggressive responding". Psychopharmacology (Berl.). 95 (3): 369–73. doi:10.1007/BF00181949. PMID 3137624.

- ^ Pietras CJ, Lieving LM, Cherek DR, Lane SD, Tcheremissine OV, Nouvion S (2005). "Acute effects of lorazepam on laboratory measures of aggressive and escape responses of adult male parolees". Behav Pharmacol. 16 (4): 243–51. doi:10.1097/01.fbp.0000170910.53415.77. PMID 15961964.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kalachnik JE, Hanzel TE, Sevenich R, Harder SR (2002). "Benzodiazepine behavioral side effects: review and implications for individuals with mental retardation". Am J Ment Retard. 107 (5): 376–410. doi:10.1352/0895-8017(2002)107<0376:BBSERA>2.0.CO;2. PMID 12186578.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mancuso CE, Tanzi MG, Gabay M (2004). "Paradoxical reactions to benzodiazepines: literature review and treatment options". Pharmacotherapy. 24 (9): 1177–85. doi:10.1592/phco.24.13.1177.38089. PMID 15460178.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Free full text with registration - ^ Goldney RD (1977). "Paradoxical reaction to a new minor tranquilizer". Med. J. Aust. 1 (5): 139–40. PMID 15198.

- ^ Edwards RA, Medlicott RW (1980). "Advantages and disadvantages of benzodiazepine prescription". N Z Med J. 92 (671): 357–9. PMID 6109269.

- ^ Izaute M, Bacon E (2005). "Specific effects of an amnesic drug: effect of lorazepam on study time allocation and on judgment of learning". Neuropsychopharmacology. 30 (1): 196–204. doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1300564. PMID 15483562. Free full text

- ^ Scharf MB, Kales A, Bixler EO, Jacoby JA, Schweitzer PK (1982). "Lorazepam-efficacy, side effects, and rebound phenomena". Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 31 (2): 175–9. PMID 6120058.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Genus Pharmaceuticals (January 21, 1998). "Lorazepam: Patient Information Leaflet, UK, 1998". benzo.org.uk. Retrieved 2007-05-14.

- ^ "Lorazepam". Patient UK. October 25, 2006. Retrieved 2007-05-14.

- ^ Coundil of Europe, Pompidou Group (Strassbourg, 2002) Contribution to the sensible use of benzodiazepines. ISBN 9789287147516.

- ^ Braestrup C (1978). "Pharmacological characterization of benzodiazepine receptors in the brain". Eur J Pharmacol. 48 (3): 263–70. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(78)90085-7. PMID 639854.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|day=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Benzodiazepine Names". non-benzodiazepines.org.uk. Retrieved 2008-12-29.

- ^ Labaton, Stephen (July 13, 2000). "Generic-Drug Maker Agrees to Settlement In Price-Fixing Case". The New York Times. Retrieved 2007-05-14.

- ^ International Narcotics Control Board (August 2003). Template:PDFlink, 23rd ed., Vienna: International Narcotics Control Board, p.7.

- ^ Derogatis, Jim (April 8, 2007). "Falling in: North Shore heroes Fall Out Boy are as surprised as you are by their success". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 2007-05-14.

External links

- inchem.org - Lorazepam data sheet

- rxlist.com - Lorazepam data sheet

- drugs.com - Lorazepam data sheet

- baxter.com - Lorazepam Injection Data Sheet

- NZ medsafe.govt.nz - Lorzem Data Sheet

- benzo.org.uk - Genus/Wyeth 1998 UK Lorazepam Data Sheet

- benzo.org.uk - Ashton H. Benzodiazepines: How They Work And How to Withdraw. August 2002 (The "Ashton Manual").

- ndaa.org - Drummer, OH. 'Benzodiazepines: Effects on Human Performance and Behavior'(Central Police University Press, 2002).