Marie Curie: Difference between revisions

m r2.7.1) (Robot: Adding sa:मेरी क्युरी |

→Legacy: fixed spelling error |

||

| (160 intermediate revisions by 15 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{other uses}} |

|||

{{Redirect|Madame Curie|the 1943 biographical film about her|Madame Curie (film)}} |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=August 2012}} |

|||

{{About|the chemist and physicist|the schools named after her|École élémentaire Marie-Curie|and|Marie Curie High School|the European research fellowships program| Marie Curie Actions}} |

|||

{{Use |

{{Use British English|date=August 2012}} |

||

{{sprotected2}} |

{{sprotected2}} |

||

<!--Note:Please do not change the nationality from Polish to French without consulting the discussion page. This formulation has been found to be the best way to reflect Curie's strong connections to both of these countries--> |

|||

{{Infobox scientist |

{{Infobox scientist |

||

| name = Marie Skłodowska-Curie |

| name = Marie Skłodowska-Curie |

||

| image = Marie Curie c1920.png |

| image = Marie Curie c1920.png |

||

| image_size=200px |

| image_size=200px |

||

| caption = Marie Curie, ca. 1920 |

| caption = Marie Curie, ca. 1920 |

||

| birth_date = {{birth date|1867|11|7|df=y}} |

| birth_date = {{birth date|1867|11|7|df=y}} |

||

| birth_place = [[Warsaw]], [[Congress Poland|Kingdom of Poland]], then part of [[Russian Empire]]<ref |

| birth_place = [[Warsaw]], [[Congress Poland|Kingdom of Poland]], then part of [[Russian Empire]]<ref name="nobelprize"/> |

||

| death_date = {{death date and age|df=yes|1934|7|4|1867|11|7}} |

| death_date = {{death date and age|df=yes|1934|7|4|1867|11|7}} |

||

| death_place = [[Passy, Haute-Savoie]], France |

| death_place = [[Passy, Haute-Savoie]], France |

||

| residence = [[Poland]] and [[France]] |

| residence = [[Poland]] and [[France]] |

||

| citizenship = Poland<br />France |

| citizenship = Poland<br />France |

||

| field = [[Physics]], [[Chemistry]] |

| field = [[Physics]], [[Chemistry]] |

||

| work_institutions = [[University of Paris]] |

| work_institutions = [[University of Paris]] |

||

| alma_mater = University of Paris <br />[[ESPCI]] |

| alma_mater = University of Paris <br />[[ESPCI]] |

||

| Line 28: | Line 27: | ||

}} |

}} |

||

'''Marie Skłodowska-Curie''' (7 November 1867 – 4 July 1934) was a French-Polish [[physicist]] and [[chemist]], famous for her pioneering research on [[radioactivity]]. She was the first |

'''Marie Skłodowska-Curie''' (7 November 1867 – 4 July 1934) was a French-Polish<!--Note:Please do not change the nationality from Polish to French without consulting the discussion page. This formulation has been found to be the best way to reflect Curie's strong connections to both of these countries--> [[physicist]] and [[chemist]], famous for her pioneering research on [[radioactivity]]. She was the first woman to win a Nobel Prize, the only woman to date to win in two fields, and the only person to win in [[Nobel Prize#Multiple laureates|multiple sciences]]. She was also the first female professor at the [[University of Paris]] (''La Sorbonne''), and in 1995 became the first woman to be entombed on her own merits in the [[Panthéon, Paris|Panthéon]] in Paris. |

||

She was born '''Maria Salomea Skłodowska''' ({{IPA-pl|ˈmarja salɔˈmɛa skwɔˈdɔfska|}}) in [[Warsaw]], in what was then the [[Congress Poland|Kingdom of Poland]]. She studied at Warsaw's clandestine [[Flying University|Floating University]] and began her practical scientific training in Warsaw. In 1891, aged 24, she followed her older sister Bronisława to study in Paris, where she earned her higher degrees and conducted her subsequent scientific work. She shared her 1903 [[Nobel Prize in Physics]] with her husband [[Pierre Curie]] and with the physicist [[Henri Becquerel]]. Her daughter [[Irène Joliot-Curie]] and son-in-law, [[Frédéric Joliot-Curie]], would similarly share a Nobel Prize. She was the sole winner of the 1911 [[Nobel Prize in Chemistry |

She was born '''Maria Salomea Skłodowska''' ({{IPA-pl|ˈmarja salɔˈmɛa skwɔˈdɔfska|pron}}) in [[Warsaw]], in what was then the [[Congress Poland|Kingdom of Poland]]. She studied at Warsaw's clandestine [[Flying University|Floating University]] and began her practical scientific training in Warsaw. In 1891, aged 24, she followed her older sister [[Bronisława Dłuska|Bronisława]] to study in Paris, where she earned her higher degrees and conducted her subsequent scientific work. She shared her 1903 [[Nobel Prize in Physics]] with her husband [[Pierre Curie]] and with the physicist [[Henri Becquerel]]. Her daughter [[Irène Joliot-Curie]] and son-in-law, [[Frédéric Joliot-Curie]], would similarly share a Nobel Prize. She was the sole winner of the 1911 [[Nobel Prize in Chemistry]]. |

||

Her achievements included a theory of ''[[radioactivity]]'' (a term that she coined |

Her achievements included a theory of ''[[radioactivity]]'' (a term that she coined), techniques for isolating radioactive [[isotope]]s, and the discovery of two elements, [[polonium]] and [[radium]]. Under her direction, the world's first studies were conducted into the treatment of [[neoplasm]]s, using radioactive isotopes. She founded the [[Curie Institute (Paris)|Curie Institutes in Paris]] and [[Curie Institute (Warsaw)|in Warsaw]], which remain major centres of medical research today. |

||

While an actively loyal French citizen, Skłodowska-Curie (she used both surnames) never lost her sense of Polish identity. She taught her daughters the [[Polish language]] and took them on visits to Poland. She named the first [[chemical element]] that she discovered – polonium, which she first isolated in 1898 – after her native country. |

While an actively loyal French citizen, Marie Skłodowska-Curie (she used both surnames) never lost her sense of Polish identity. She taught her daughters the [[Polish language]] and took them on visits to Poland. She named the first [[chemical element]] that she discovered – polonium, which she first isolated in 1898 – after her native country.{{Ref_label|a|a|none}} |

||

Curie died in 1934 of [[aplastic anemia]] brought on by her years of exposure to radiation. |

|||

==Biography== |

|||

===Early life=== |

|||

[[File:Sklodowski Family Wladyslaw and his daughters Maria Bronislawa Helena.jpg|thumb|125px||left|Władysław Skłodowski with daughters ''(from left)'' Maria, Bronisława, Helena, 1890]] |

|||

[[File:Marie Curie birthplace.jpg|thumb|125px||Birthplace on ''ulica Freta'' in Warsaw's "[[Warsaw New Town|New Town]]" – now home to the [[Maria Skłodowska-Curie Museum]]]] |

|||

Maria Skłodowska was born in [[Warsaw]], in the [[Russian partition]] of Poland, on 7 November 1867, the fifth and youngest child of well-known teachers Bronisława and Władysław Skłodowski. Maria's older siblings were Zofia (born 1862), Józef (1863), Bronisława (1865) and Helena (1866). |

|||

==Biography== |

|||

Maria's paternal grandfather Józef Skłodowski had been a respected teacher in [[Lublin]], where he taught the young [[Bolesław Prus#Early years|Bolesław Prus]].<ref name="robert1"/> Her father Władysław Skłodowski taught mathematics and physics, subjects that Maria was to pursue, and was also director of two Warsaw ''[[gymnasium (school)|gymnasia]]'' for boys, in addition to lodging boys in the family home. Maria's mother Bronisława operated a prestigious Warsaw [[boarding school]] for girls; she suffered from [[tuberculosis]] and died when Maria was twelve. |

|||

===Early years=== |

|||

[[File:Sklodowski Family Wladyslaw and his daughters Maria Bronislawa Helena.jpg|thumb|upright|left|Władysław Skłodowski with daughters ''(from left)'' Maria, Bronisława, Helena, 1890]] |

|||

[[File:Marie Curie birthplace.jpg|thumb|upright|Birthplace on ''ulica Freta'' in Warsaw's "[[Warsaw New Town|New Town]]" – now home to the [[Maria Skłodowska-Curie Museum]]]] |

|||

Maria Skłodowska was born in [[Warsaw]], in the [[Russian partition]] of Poland, on 7 November 1867, the fifth and youngest child of well-known teachers Bronisława and Władysław Skłodowski.<ref name="psb111"/> Maria's older siblings were Zofia (born 1862), [[Józef Skłodowski (doctor)|Józef]] (1863), [[Bronisława Dłuska|Bronisława]] (1865) and [[Helena Skłodowska-Szaley|Helena]] (1866).<ref name="Marie Curie — Polish Girlhood (1867–1891)"/> |

|||

On both the paternal and maternal sides, the family had lost their property and fortunes through patriotic involvements in Polish national uprisings aiming at the restoration of Poland's independence (most recent of which was the [[January Uprising]]).<ref name="gwiazdapolarna"/> This condemned each subsequent generation, including that of Maria, her elder sisters and her brother, to a difficult struggle to get ahead in life.<ref name="gwiazdapolarna"/> |

|||

Maria's father was an [[atheist]]; her mother—a devout Catholic.<ref name="Eve Curie, Marie Curie"/> Two years earlier Maria's oldest sibling, Zofia, had died of [[typhus]]. The deaths of her mother and sister, according to Robert William Reid, caused Maria to give up Catholicism and become [[agnostic]].<ref name="Marie Curie"/> |

|||

Maria's paternal grandfather [[Józef Skłodowski (teacher)|Józef Skłodowski]] had been a respected teacher in [[Lublin]], where he taught the young [[Bolesław Prus#Early years|Bolesław Prus]].<ref name="robert1"/> Her father Władysław Skłodowski taught mathematics and physics, subjects that Maria was to pursue, and was also director of two Warsaw ''[[gymnasium (school)|gymnasia]]'' for boys.<ref name="Marie Curie — Polish Girlhood (1867–1891)"/> After Russian authorities eliminated laboratory instruction from the Polish schools, he brought much of the lab equipment home, and instructed his children in its use.<ref name="Marie Curie — Polish Girlhood (1867–1891)"/> He was eventually fired by the Russian supervisors for pro-Polish sentiments, and forced to take lower paying posts; the family also lost money on a bad investment, and eventually chose to supplement the income by lodging boys in their house.<ref name="Marie Curie — Polish Girlhood (1867–1891)"/> Maria's mother Bronisława operated a prestigious Warsaw [[boarding school]] for girls; she resigned from the position after Maria was born.<ref name="Marie Curie — Polish Girlhood (1867–1891)"/> She also suffered from [[tuberculosis]] and died when Maria was twelve.<ref name="Marie Curie — Polish Girlhood (1867–1891)"/> Maria's father was an [[atheist]]; her mother—a devout Catholic.<ref name="Barker2011"/> Two years before the death of her mother, Maria's oldest sibling, Zofia, had died of [[typhus]].<ref name="Marie Curie — Polish Girlhood (1867–1891)"/> The deaths of her mother and sister caused Maria to give up Catholicism and become [[agnostic]].<ref name="Marie Curie"/> |

|||

When she was ten years old, Maria began attending the boarding school that her mother had operated while she was well; next Maria attended a ''[[gymnasium (school)|gymnasium]]'' for girls, from which she graduated on 12 June 1883. She spent the following year in the countryside with relatives of her father's, and the next with her father in Warsaw, where she did some [[tutor]]ing. |

|||

When she was ten years old, Maria began attending the boarding school that her mother had operated while she was well; next Maria attended a ''[[gymnasium (school)|gymnasium]]'' for girls, from which she graduated on 12 June 1883 with a gold medal.<ref name="psb111"/> Due to possible [[depression]],<ref name="Marie Curie — Polish Girlhood (1867–1891)"/> she spent the following year in the countryside with relatives of her father's, and the next with her father in Warsaw, where she did some [[tutor]]ing.<ref name="psb111"/> Unable to enrol in a [[higher education]] institution due to being a female, she and her sister Bronisława became involved with the [[Flying University]], a clandestine teaching institution, teaching a pro-Polish curriculum in defiance of the Russian authorities, and also willing to admit female students.<ref name="psb111"/><ref name="Marie Curie — Polish Girlhood (1867–1891)"/> |

|||

On both the paternal and maternal sides, the family had lost their property and fortunes through patriotic involvements in Polish national uprisings aiming at the restoration of Poland's independence (most recent of which was the [[January Uprising]]). This condemned each subsequent generation, including that of Maria, her elder sisters and her brother, to a difficult struggle to get ahead in life.<ref name="gwiazdapolarna"/> |

|||

[[File:Kazm.JPG|thumb|left|125px||Elderly [[Kazimierz Żorawski|Żorawski]]]] |

|||

[[File:Krakowskie Przedmiescie, Warsaw.JPG|thumb|125px||At a Warsaw lab here, in 1890–91, Skłodowska did her first scientific work.]] |

|||

Maria made an agreement with her sister, Bronisława, that she would give her financial assistance during Bronisława's medical studies in Paris, in exchange for similar assistance two years later.<ref name="autobiography"/> In connection with this, Maria took a position as [[governess]]: first with a lawyer's family in [[Kraków]]; then for two years in [[Ciechanów]] with a landed family, the Żorawskis, who were relatives of her father. While working for the latter family, she fell in love with their son, [[Kazimierz Żorawski]], which was reciprocated by this future eminent mathematician. His parents, however, rejected the idea of his marrying the penniless relative, and Kazimierz was unable to oppose them. Maria lost her position as governess.<ref name="susan"/> She found another with the Fuchs family in [[Sopot]], on the [[Baltic Sea]] coast, where she spent the next year, all the while financially assisting her sister. |

|||

Maria made an agreement with her sister, Bronisława, that she would give her financial assistance during Bronisława's medical studies in Paris, in exchange for similar assistance two years later.<ref name="psb111"/><ref name="Marie Curie — Polish Girlhood (1867–1891)1"/> In connection with this, Maria took a position as [[governess]]: first at a home tutor in Warsaw; then for two years as a [[governess]] in [[Szczuki, Masovian Voivodeship|Szczuki]] with a landed family, the Żorawskis, who were relatives of her father.<ref name="psb111"/><ref name="Marie Curie — Polish Girlhood (1867–1891)1"/> While working for the latter family, she fell in love with their son, [[Kazimierz Żorawski]], which was reciprocated by this future eminent mathematician.<ref name="Marie Curie — Polish Girlhood (1867–1891)1"/> His parents rejected the idea of his marrying the penniless relative, and Kazimierz was unable to oppose them.<ref name="Marie Curie — Polish Girlhood (1867–1891)1"/> Maria lost her position as governess. She found another with the Fuchs family in [[Sopot]], on the [[Baltic Sea]] coast, where she spent the next year, all the while financially assisting her sister. |

|||

At the beginning of 1890, Bronisława, a few months after she married Kazimierz Dłuski, invited Maria to join them in Paris. Maria declined because she could not afford the university [[tuition]] and was still counting on marrying [[Kazimierz Żorawski]]. |

|||

She returned home to her father in Warsaw, where she remained till the fall of 1891. She tutored, studied at the clandestine [[Flying University|Floating University]],<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.aip.org/history/curie/polgirl1.htm |title=Marie Curie — Polish Girlhood (1867–1891) |publisher=Aip.org |accessdate=7 November 2011}}</ref> and began her practical scientific training (1890–91) in a laboratory at the [[Museum of Industry and Agriculture]] at ''[[Krakowskie Przedmieście]] 66'', near [[Warsaw Old Town|Warsaw's Old Town]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.aip.org/history/curie/polgirl2.htm |title=Marie Curie — Polish Girlhood (1867–1891) |publisher=Aip.org |accessdate=7 November 2011}}</ref> The laboratory was run by her cousin [[Józef Boguski]], who had been assistant in [[Saint Petersburg]] to the great Russian chemist [[Dmitri Mendeleev]].<ref name="teachers"/> |

|||

At the beginning of 1890, Bronisława, a few months after she married [[Kazimierz Dłuski]], a physician and social and political activist, invited Maria to join them in Paris.<ref name="psb111"/> Maria declined because she could not afford the university [[tuition]]; it would take year a year and a half longer to gather the necessary funds.<ref name="psb111"/> She would be helped by her father, who was able to secure a more lucrative position again.<ref name="Marie Curie — Polish Girlhood (1867–1891)1"/> All that time she continued to educate herself, reading books, exchanging letters, and being tutored herself.<ref name="Marie Curie — Polish Girlhood (1867–1891)1"/> In early 1889 she returned home to her father in Warsaw.<ref name="psb111"/> She continued working as a governess, and remained there till late 1891.<ref name="Marie Curie — Polish Girlhood (1867–1891)1"/> She tutored, studied at the Flying University, and began her practical scientific training (1890–91) in a chemical laboratory at the [[Museum of Industry and Agriculture]] at ''[[Krakowskie Przedmieście]] 66'', near [[Warsaw Old Town|Warsaw's Old Town]].<ref name="psb111"/><ref name="Marie Curie — Polish Girlhood (1867–1891)"/><ref name="Marie Curie — Polish Girlhood (1867–1891)1"/> The laboratory was run by her cousin [[Józef Boguski]], who had been assistant in [[Saint Petersburg]] to the Russian chemist [[Dmitri Mendeleev]].<ref name="psb111"/><ref name="Marie Curie — Polish Girlhood (1867–1891)1"/><ref name="teachers"/> In October 1891, at her sister's insistence and after receiving a letter from Żorawski, in which he definitively broke his relationship with her, she decided to go to France after all. |

|||

In October 1891, at her sister's insistence and after receiving a letter from Żorawski, in which he definitively broke his relationship with her, she decided to go to France after all.<ref name="Eve Curie, Marie Curie"/> |

|||

Maria's loss of the relationship with Żorawski was tragic for both. He soon earned a doctorate and pursued an academic career as a mathematician, becoming a professor and [[Rector (academia)|rector]] of [[Jagiellonian University|Kraków University]] |

Maria's loss of the relationship with Żorawski was tragic for both. He soon earned a doctorate and pursued an academic career as a mathematician, becoming a professor and [[Rector (academia)|rector]] of [[Jagiellonian University|Kraków University]].<ref name="gwiazdapolarna"/> Still, as an old man and a mathematics professor at the [[Warsaw Polytechnic]], he would sit contemplatively before the statue of Maria Skłodowska which had been erected in 1935 before the [[Radium Institute]] that she had founded in 1932.<ref name="gwiazdapolarna"/><ref name="robert2"/> |

||

===New life in Paris=== |

|||

In Paris, Maria briefly found shelter with her sister and brother-in-law before renting a primitive garret<ref name="robert3"/> and proceeding with her studies of physics, chemistry, and mathematics at the [[Sorbonne]] (the University of Paris). |

|||

[[File:Krakowskie Przedmiescie, Warsaw.JPG|thumb|upright|At a Warsaw lab here, in 1890–91, Skłodowska did her first scientific work.]] |

|||

In Paris, Maria briefly found shelter with her sister and brother-in-law before renting a garret closer to the university, in the [[Latin Quarter]], and proceeding with her studies of physics, chemistry, and mathematics at the [[Sorbonne]] (the University of Paris), where she enrolled in the fall of 1891.<ref name="robert3"/><ref name="Marie Curie — Student in Paris"/> She subsided on her meagre resources, suffering from cold winters and occasionally fainting from hunger.<ref name="Marie Curie — Student in Paris"/> |

|||

Skłodowska studied during the day and tutored in the evenings, barely earning her keep. In 1893, she was awarded a degree in physics and began work in an industrial laboratory of professor [[Gabriel Lippmann]].<ref name="psb111"/> Meanwhile she continued studying at the Sorbonne, and with an aid of a fellowship, she was able to earn a second degree in 1894.<ref name="psb111"/><ref name="Marie Curie — Student in Paris"/>{{Ref label|b|b|none}} |

|||

===Pierre Curie=== |

|||

[[File:Pierrecurie.jpg|thumb|left|80px|[[Pierre Curie]]]] |

|||

Skłodowska studied during the day and tutored evenings, barely earning her keep. In 1893, she was awarded a degree in physics and began work in an industrial laboratory at Lippman's. Meanwhile she continued studying at the Sorbonne, and in 1894, earned a degree in mathematics. |

|||

That same year, [[Pierre Curie]] entered her life. |

Skłodowska had begun her scientific career in Paris with an investigation of the magnetic properties of various steels, commissioned by [[Society for the Encouragement of National Industry]] (''Société d'encouragement pour l'industrie nationale'').<ref name="Marie Curie — Student in Paris"/> That same year, [[Pierre Curie]] entered her life; it was their mutual interest in natural sciences that drew them together.<ref name="Williams331"/> Pierre was an instructor at the School of Physics and Chemistry, the ''[[École supérieure de physique et de chimie industrielles de la ville de Paris]]'' (ESPCI).<ref name="psb111"/> They were introduced to one another by professor [[Józef Wierusz-Kowalski]], who learned that Skłodowska was looking for a larger laboratory space, something that Wierusz-Kowalski thought Pierre had access to.<ref name="psb111"/><ref name="Marie Curie — Student in Paris"/> Although Pierre did not have a large laboratory, he was able to find some space for Marie, where she was able to begin her work.<ref name="Marie Curie — Student in Paris"/> |

||

Their mutual passion for science brought them increasingly closer.<ref name="Marie Curie — Student in Paris"/> The two begun to develop feelings for one another, although at first Skłodowska did not accept his marriage proposal, not wishing to stay in France; Pierre however declared that he was ready to move with her to Poland, even if he was to be reduced to a [[French language]] teacher.<ref name="psb111"/> Marie departed for the summer of 1894 to Warsaw.<ref name="Marie Curie — Student in Paris"/> She was still labouring under the illusion that she would be able to return to Poland and work in her chosen field of study, but she was denied a place at [[Jagiellonian University|Kraków University]] because she was a woman.<ref name="gwiazdapolarna"/> A letter from Pierre convinced her to return to Paris to pursue a [[PhD]].<ref name="Marie Curie — Student in Paris"/> Upon Marie's insistence, Pierre has written up his research on [[magnetism]], and received his own doctorate in March 1895; he was also promoted to a [[professorship]] position in the School.<ref name="Marie Curie — Student in Paris"/> A contemporary anecdote would call Marie "the biggest discovery's in Pierre's life."<ref name="gwiazdapolarna"/> On 26 July that year, she and Pierre married in a [[civil union]]; neither wanted a religious service.<ref name="psb111"/><ref name="Marie Curie — Student in Paris"/> Marie's dark blue outfit, worn instead of a bridal grown, would serve her for many years as a lab outfit.<ref name="Marie Curie — Student in Paris"/> They shared two hobbies, long bicycle trips and journeys abroad, which brought them even closer.<ref name="gwiazdapolarna"/> In Pierre, Maria had found a new love, a partner, and a scientific collaborator upon whom she could depend.<ref name="gwiazdapolarna"/> |

|||

===New elements=== |

===New elements=== |

||

[[File:Pierre and Marie Curie.jpg|thumb|[[Pierre Curie|Pierre]] and Marie Curie in the laboratory]] |

|||

In 1896 [[Henri Becquerel]] discovered that [[uranium]] salts emitted rays that resembled [[X-ray]]s in their penetrating power. He demonstrated that this radiation, unlike [[phosphorescence]], did not depend on an external source of energy, but seemed to arise spontaneously from uranium itself. Becquerel had, in fact, discovered radioactivity. |

|||

In 1895 [[Wilhelm Roentgen]] discovered the existence of [[X-ray]]s, through the mechanism behind their existence was not yet understood.<ref name="Marie Curie and the Science of Radioactivity"/> In 1896 [[Henri Becquerel]] discovered that [[uranium]] salts emitted rays that resembled [[X-ray]]s in their penetrating power.<ref name="Marie Curie and the Science of Radioactivity"/> He demonstrated that this radiation, unlike [[phosphorescence]], did not depend on an external source of energy, but seemed to arise spontaneously from uranium itself.<ref name="psb111"/> Marie decided to look into uranium rays as a possible field of research for a [[thesis]].<ref name="psb111"/> She used an innovative technique to investigate samples. Fifteen years earlier, her husband and his brother had invented the [[electrometer]], a sensitive device for measuring electrical charge.<ref name="Marie Curie and the Science of Radioactivity"/> Using Pierre's electrometer, she discovered that uranium rays caused the air around a sample to conduct electricity.<ref name="Marie Curie and the Science of Radioactivity"/> Using this technique, her first result was the finding that the activity of the uranium compounds depended only on the quantity of uranium present.<ref name="Marie Curie and the Science of Radioactivity"/> She had [[hypothesis|hypothesized]] that the radiation was not the outcome of some interaction of [[molecule]]s, but must come from the [[atom]] itself.<ref name="Marie Curie and the Science of Radioactivity"/> Beginning to question the claim that atoms are not indivisible was among her most important contributions to science.<ref name="Marie Curie and the Science of Radioactivity"/><ref name="robert4"/> |

|||

In 1897 her daughter [[Irène Joliot-Curie|Irène]] was born.<ref name="psb112"/> To support the family, Marie begun teaching at the [[École Normale Supérieure]].<ref name="psb112"/> The Curies did not have a dedicated laboratory; most of their research was carried in a converted shed next to the School of Physics and Chemistry.<ref name="psb112"/> The shed, formerly a medical school dissecting room, was poorly ventilated and not even waterproof.<ref name="Marie Curie and the Science of Radioactivity 2"/> As they were unaware of the deleterious effects of [[Radioactive contamination|radiation exposure]] attendant on their chronic unprotected work with radioactive substances, Marie and her husband had no idea what price they would pay for the effect of their research upon their health.<ref name="gwiazdapolarna"/> The School would not sponsor her research, she would receive some subsidies from metallurgical and mining companies, and various organizations and governments.<ref name="psb112"/><ref name="Marie Curie and the Science of Radioactivity 2"/><ref name="Marie Curie — Student in Paris 2"/> |

|||

Curie decided to look into uranium rays as a possible field of research for a [[thesis]]. She used a clever technique to investigate samples. Fifteen years earlier, her husband and his brother had invented the [[electrometer]], a sensitive device for measuring electrical charge. Using the Curie electrometer, she discovered that uranium rays caused the air around a sample to conduct electricity.<ref name="Marie Curie and the Science of Radioactivity"/> Using this technique, her first result was the finding that the activity of the uranium compounds depended only on the quantity of uranium present. She had shown that the radiation was not the outcome of some interaction of [[molecule]]s, but must come from the [[atom]] itself. In scientific terms, this was the most important single piece of work that she conducted.<ref name="robert4"/> |

|||

Marie's systematic studies had included two uranium minerals, [[pitchblende]] and [[torbernite]] (also known as chalcolite).<ref name="Marie Curie and the Science of Radioactivity 2"/> Her electrometer showed that pitchblende was four times as active as uranium itself, and chalcolite twice as active. She concluded that, if her earlier results relating the quantity of uranium to its activity were correct, then these two minerals must contain small quantities of some other substance that was far more active than uranium itself.<ref name="Marie Curie and the Science of Radioactivity 2"/><ref name="robert5"/> In her systematic search for other substances beside uranium salts that emitted radiation, by 1898, Marie had found that the element [[thorium]] likewise, was radioactive.<ref name="Marie Curie and the Science of Radioactivity"/> |

|||

Pierre was increasingly intrigued by her work. By mid-1898 he was so invested in it that he decided to drop his work on crystals and to join her.<ref name="psb112"/><ref name="Marie Curie and the Science of Radioactivity 2"/> |

|||

{{blockquote|The idea [writes Reid] was her own; no one helped her formulate it, and although she took it to her husband for his opinion she clearly established her ownership of it. She later recorded the fact twice in her biography of her husband to ensure there was no chance whatever of any ambiguity. It [is] likely that already at this early stage of her career [she] realized that... many scientists would find it difficult to believe that a woman could be capable of the original work in which she was involved.<ref name="robert6"/>}} |

|||

{{blockquote|The [research] idea [writes Reid] was her own; no one helped her formulate it, and although she took it to her husband for his opinion she clearly established her ownership of it. She later recorded the fact twice in her biography of her husband to ensure there was no chance whatever of any ambiguity. It [is] likely that already at this early stage of her career [she] realized that... many scientists would find it difficult to believe that a woman could be capable of the original work in which she was involved.<ref name="robert6"/>}} |

|||

In her systematic search for other substances beside uranium salts that emitted radiation, Curie had found that the element [[thorium]] likewise, was radioactive. |

|||

[[File:Marie et Pierre Curie .jpg|thumb|150px|left|[[Pierre Curie|Pierre]] and Marie Curie in the laboratory]] |

|||

[[File:Pierre and Marie Curie.jpg|thumb|200px|[[Pierre Curie|Pierre]] and Marie Curie in the laboratory]] |

|||

She was acutely aware of the importance of promptly publishing her discoveries and thus establishing her [[scientific priority|priority]]. Had not Becquerel, two years earlier, presented his discovery to the ''[[Académie des Sciences]]'' the day after he made it, credit for the discovery of radioactivity, and even a Nobel Prize, would have gone to [[Silvanus Thompson]] instead. Curie chose the same rapid means of publication. Her paper, giving a brief and simple account of her work, was presented for her to the ''Académie'' on 12 April 1898 by her former professor, [[Gabriel Lippmann]].<ref name="robert7"/> |

|||

[[File:Marie Pierre Irene Curie.jpg|thumb|[[Pierre Curie|Pierre]], [[Irène Joliot-Curie|Irène]], Marie Curie]] |

|||

Even so, just as Thompson had been beaten by Becquerel, so Curie was beaten in the race to tell of her discovery that thorium gives off rays in the same way as uranium. Two months earlier, Gerhard Schmidt had published his own finding in Berlin.<ref name="independent"/> |

|||

She was acutely aware of the importance of promptly publishing her discoveries and thus establishing her [[scientific priority|priority]]. Had not Becquerel, two years earlier, presented his discovery to the ''[[Académie des Sciences]]'' the day after he made it, credit for the discovery of radioactivity, and even a Nobel Prize, would have gone to [[Silvanus Thompson]] instead. Marie chose the same rapid means of publication. Her paper, giving a brief and simple account of her work, was presented for her to the ''Académie'' on 12 April 1898 by her former professor, [[Gabriel Lippmann]].<ref name="robert7"/> Even so, just as Thompson had been beaten by Becquerel, so Marie was beaten in the race to tell of her discovery that thorium gives off rays in the same way as uranium. Two months earlier, [[Gerhard Schmidt]] had published his own finding in Berlin.<ref name="independent"/> |

|||

At that time |

At that time no one else in the world of physics had noticed what Marie recorded in a sentence of her paper, describing how much greater were the activities of pitchblende and chalcolite than uranium itself: "The fact is very remarkable, and leads to the belief that these minerals may contain an element which is much more active than uranium." She later would recall how she felt "a passionate desire to verify this hypothesis as rapidly as possible."<ref name="Robert Reid p. 65"/> On 14 April 1898, the Curies optimistically weighed out a 100-gram sample of pitchblende and ground it with a pestle and mortar. They did not realize at the time that what they were searching for was present in such minute quantities that they would eventually have to process tons of the ore.<ref name="Robert Reid p. 65"/> |

||

In July 1898, Marie and her husband published a paper together, announcing the existence of an element which they named "[[polonium]]", in honour of her native Poland, which would for another twenty years remain partitioned among three empires that [[partitions of Poland|claimed it a century before]].<ref name="psb111"/> On 26 December 1898, the Curies announced the existence of a second element, which they named "[[radium]]" for its intense ''[[radioactivity]]'' – a word that they coined.<ref name="psb111"/><ref name="Marie Curie and the Science of Radioactivity"/><ref name="psb112"/><ref name="The Discovery of Radioactivity"/> |

|||

Pierre Curie was sure that what she had discovered was not a spurious effect. He was so intrigued that he decided to drop his work on crystals temporarily and to join her. On 14 April 1898, they optimistically weighed out a 100-gram sample of pitchblende and ground it with a pestle and mortar. They did not realize at the time that what they were searching for was present in such minute quantities that they eventually would have to process tons of the ore.<ref name="Robert Reid p. 65"/> |

|||

To prove their discoveries beyond any doubt, the Curies had set up to isolate polonium and radium into its pure components.<ref name="Marie Curie and the Science of Radioactivity 2"/> Pitchblende is a complex mineral. The chemical separation of its constituents was an arduous task. The discovery of polonium had been relatively easy; chemically it resembles the element [[bismuth]], and polonium was the only bismuth-like substance in the ore. Radium, however, was more elusive. It is closely related, chemically, to [[barium]], and pitchblende contains both elements. By 1898, the Curies had obtained traces of radium, but appreciable quantities, uncontaminated with barium, were still beyond reach.<ref name="williams"/> The Curies undertook the arduous task of separating out radium salt by differential [[crystallization]]. From a ton of pitchblende, one-tenth of a gram of [[radium chloride]] was separated in 1902. In 1910 Marie isolated pure [[radium]] metal.<ref name="Marie Curie and the Science of Radioactivity 2"/><ref name="Williams332"/> She never succeeded in isolating polonium, which has a [[half-life]] of only 138 days.<ref name="Marie Curie and the Science of Radioactivity 2"/> |

|||

As they were unaware of the deleterious effects of [[Radioactive contamination|radiation exposure]] attendant on their chronic unprotected work with radioactive substances, Curie and her husband had no idea what price they would pay for the effect of their research upon their health.<ref name="Wierzewski, p. 17"/> |

|||

In 1900, Marie became the first women faculty member at [[École Normale Supérieure]], and Pierre joined the Sorbonne's faculty.<ref name="Marie Curie and the Science of Radioactivity 3"/><ref name="Quinn1996"/> In 1902 she visited Poland, on the occasion of her father's death.<ref name="psb112"/> In June 1903, under the supervision of Henri Becquerel, Marie was awarded her [[DSc]] from the [[University of Paris]].<ref name="psb112"/><ref name="The discovery of radium in 1898 by Maria Sklodowska-Curie (1867–1934) and Pierre Curie (1859–1906) with commentary on their life and times"/> That month she and Pierre were invited to the [[Royal Institution]] in London to give a speech on radioactivity; Marie was prevented from speaking at the forum, being female, and Pierre alone was allowed to speak.<ref name="Marie Curie Rec and Dis"/> In the meantime, a new industry begun developing based on the radon discovered by the Curies.<ref name="Marie Curie and the Science of Radioactivity 3"/> The Curies did not [[patent]] their discovery, and benefited little from this increasingly profitable venture.<ref name="Marie Curie and the Science of Radioactivity 2"/><ref name="Marie Curie and the Science of Radioactivity 3"/> |

|||

[[File:Marie Pierre Irene Curie.jpg|thumb|165px|[[Pierre Curie|Pierre]], [[Irène Joliot-Curie|Irène]], Marie Curie]] |

|||

In July 1898, Curie and her husband published a paper together, announcing the existence of an element which they named "[[polonium]]", in honor of her native Poland, which would for another twenty years remain partitioned among three empires. On 26 December 1898, the Curies announced the existence of a second element, which they named "[[radium]]" for its intense ''[[radioactivity]]'' — a word that they coined. |

|||

===Nobel Prize=== |

|||

Pitchblende is a complex mineral. The chemical separation of its constituents was an arduous task. The discovery of polonium had been relatively easy; chemically it resembles the element [[bismuth]], and polonium was the only bismuth-like substance in the ore. Radium, however, was more elusive. It is closely related, chemically, to [[barium]], and pitchblende contains ''both'' elements. By 1898, the Curies had obtained traces of radium, but appreciable quantities, uncontaminated with barium, still were beyond reach.<ref name="williams"/> |

|||

[[File:Marie Curie 1903.jpg|thumb|upright|right|1903]] |

|||

In December 1903 the [[Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences]] awarded Pierre Curie, Marie Curie and Henri Becquerel the [[Nobel Prize in Physics]], "in recognition of the extraordinary services they have rendered by their joint researches on the [[ionizing radiation|radiation]] phenomena discovered by Professor Henri Becquerel."<ref name="psb112"/> At first, the Committee intended to honour only Pierre and Henri, but one of the committee members and an advocate of woman scientists, Swedish mathematician [[Magnus Goesta Mittag-Leffler]], alerted Pierre to the situation, and after his complaint, Marie's name was added to the nomination.<ref name="Marie Curie Rec and Dis2"/> Marie was the first woman to be awarded a Nobel Prize.<ref name="psb112"/> |

|||

Marie and her husband declined to go to [[Stockholm]] to receive the prize in person; they were too busy with their work, and Pierre, who disliked public ceremonies, was feeling increasingly ill.<ref name="Marie Curie Rec and Dis"/><ref name="Marie Curie Rec and Dis2"/> As Nobel laureates were required to deliver a lecture, the Curies finally undertook the trip in 1905.<ref name="Marie Curie Rec and Dis2"/> The award money allowed the Curies to hire their first lab assistant.<ref name="Marie Curie Rec and Dis2"/> Following the award of the Nobel Prize, galvanized by the offer from the [[University of Geneva]], the Sorbonne gave Pierre a professorship and a chair of physics, although the Curies still did not have a proper laboratory.<ref name="psb112"/><ref name="Marie Curie and the Science of Radioactivity 3"/><ref name="Quinn1996"/> Upon Pierre's complaint, the Sorbonne relented and agreed to furbish a new laboratory, but it would not be ready until 1906.<ref name="Marie Curie Rec and Dis2"/> |

|||

The Curies undertook the arduous task of separating out radium salt by differential [[crystallization]]. From a ton of pitchblende, one-tenth of a gram of [[radium chloride]] was separated in 1902. By 1910, Curie, working on without her husband, who had been killed accidentally by a horse drawn vehicle<ref name="obit"/> in 1906, had isolated the pure [[radium]] metal.<ref name="L. Pearce Williams, p. 332"/> |

|||

In December 1904 Marie gave birth to their second daughter, [[Ève Curie]].<ref name="Marie Curie Rec and Dis2"/> She later hired Polish [[governess]]es to teach her daughters her native language, and sent or took them on visits to Poland.<ref name="goldsmith"/> |

|||

In an unusual decision, Marie Curie intentionally refrained from patenting the radium-isolation process, so that the scientific community could do research unhindered.<ref name="robert8"/> |

|||

On 19 April 1906 Pierre was killed in a street accident. Walking across the [[Rue Dauphine]] in heavy rain, he was struck by a horse-drawn vehicle and fell under its wheels; his skull was fractured.<ref name=obit/><ref name="psb112"/> Marie was devastated by the death of her husband.<ref name="Marie Curie Tr and Ad"/> On 13 May 1906, the Sorbonne physics department decided to retain the chair that had been created for Pierre and they offered it to Marie.<ref name="Marie Curie Tr and Ad"/> She accepted it, hoping to create a world class laboratory as a tribute to Pierre.<ref name="Marie Curie Tr and Ad"/><ref name="Marie Curie Tr and Ad2"/> She became the first woman to become a professor at the Sorbonne.<ref name="psb112"/> |

|||

In 1903, under the supervision of [[Henri Becquerel]],<ref name="The discovery of radium in 1898 by Maria Sklodowska-Curie (1867–1934) and Pierre Curie (1859–1906) with commentary on their life and times"/> Marie was awarded her [[DSc]] from the [[University of Paris]]. |

|||

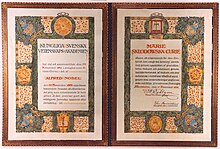

[[File:Dyplom Sklodowska-Curie.jpg|thumb|left|1911 Nobel Prize]] |

|||

Marie's quest to create a new laboratory did not end with Sorbonne. In her later years Marie headed the Radium Institute (''Institut du radium'', now [[Curie Institute (Paris)|Curie Institute]], ''Institut Curie''), a radioactivity laboratory created for her by the [[Pasteur Institute]] and the [[University of Paris]].<ref name="Marie Curie Tr and Ad2"/> This initiative came in 1909 from [[Pierre Paul Émile Roux]], director of the Pasteur Institute, who became disappointed that the Sorbonne was not giving Marie a proper laboratory and suggested that she move to the Institute.<ref name="psb112"/><ref name="psb113"/> Only then, with the threat of Marie leaving, Sorbonne relented, and eventually the Curie Pavilion became a joint initiative of the Sorbonne and the Pasteur Institute.<ref name="psb113"/> |

|||

===Nobel Prizes=== |

|||

[[File:Marie Curie 1903.jpg|thumb|100px|left|1903]] |

|||

[[File:Marie Curie (Nobel-Chem).png|thumb|100px|1911, awarded second Nobel Prize]] |

|||

In 1903 the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences awarded Pierre Curie, Marie Curie and Henri Becquerel the [[Nobel Prize in Physics]], "in recognition of the extraordinary services they have rendered by their joint researches on the [[ionizing radiation|radiation]] phenomena discovered by Professor Henri Becquerel." |

|||

In 1910 Marie succeeded in isolating radium; she also defined an international standard for radioactive emissions that would be eventually named after her and Pierre: the [[curie]].<ref name="Marie Curie Tr and Ad2"/> Nevertheless, in 1911 the [[French Academy of Sciences]] did not elect her to be a member by one<ref name="psb112"/> or two votes<ref name="Marie Curie Sc and Rec"/> Elected instead was [[Édouard Branly]], an inventor who had helped [[Guglielmo Marconi]] develop the [[wireless telegraph]].<ref name="goldsmith9"/> It would be a doctoral student of Curie, [[Marguerite Perey]], who would become the first woman elected to membership in the Academy – over half a century later, in 1962. Despite her fame as a scientist working for France, the public's attitude tended toward [[xenophobia]]—the same that had led to the [[Dreyfus affair]]–which also fuelled false speculation that Marie was Jewish.<ref name="psb112"/><ref name="Marie Curie Sc and Rec"/> During the French Academy of Sciences elections, she was vilified by the right wing press, who criticized her for being a foreigner and an atheist.<ref name="Marie Curie Sc and Rec"/> Her daughter would later remark on the public [[hypocrisy]]; as the French press often portrayed Marie as an unworthy foreigner when she was nominated for a French honour, but would portray her as a French hero when she received a foreign one, such as her Nobel Prizes.<ref name="psb112"/> |

|||

Curie and her husband were unable to go to [[Stockholm]] to receive the prize in person, but they shared its financial proceeds with needy acquaintances, including students.<ref name="Wierzewski, p. 17"/> |

|||

[[File:1911 Solvay conference.jpg|thumb|right|At First [[Solvay Conference]] (1911), Curie (seated, 2nd from right) confers with [[Henri Poincaré]]. Standing, 4th from right, is [[Ernest Rutherford|Rutherford]]; 2nd from right, [[Albert Einstein|Einstein]]; far right, [[Paul Langevin]]]] |

|||

On receiving the Nobel Prize, Marie and Pierre Curie suddenly became very famous. The Sorbonne gave Pierre a professorship and permitted him to establish his own laboratory, in which Curie became the director of research. |

|||

In 1911 it was revealed that in 1910–11 Marie had conducted an affair of about a year's duration with physicist [[Paul Langevin]], a former student of Pierre's.<ref name="robert10"/> He was a married man who was estranged from his wife.<ref name="Marie Curie Sc and Rec"/> This resulted in a press scandal that was exploited by her academic opponents. Marie was five years older than Langevin and was portrayed in the tabloids as a foreign Jewish home-wrecker.<ref name="goldsmith11"/> Curie was away for a conference in Belgium when the scandal broke, upon her return, she found an angry mob in front of her house, and had to seek a refuge with her daughters at a house of a friend.<ref name="Marie Curie Sc and Rec"/> Later, Curie's granddaughter, [[Hélène Langevin-Joliot|Hélène Joliot]], married Langevin's grandson, Michel Langevin.<ref name="Marie Curie Sc and Rec2"/> |

|||

Despite that, international recognition for her work grew to new heights, and in 1911 the [[Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences]] awarded her a second Nobel Prize, this time [[Nobel Prize in Chemistry|for Chemistry]].<ref name="gwiazdapolarna"/> This award was "in recognition of her services to the advancement of chemistry by the discovery of the elements radium and polonium, by the isolation of radium and the study of the nature and compounds of this remarkable element."<ref name="Marie Curie Sc and Rec2"/> Marie was the first person to win or share two Nobel Prizes. She is one of only two people who have been awarded a Nobel Prize in two different fields, the other person being [[Linus Pauling]] (for chemistry and for peace). A delegation of celebrated Polish men of learning, headed by novelist [[Henryk Sienkiewicz]], encouraged her to return to Poland and continue her research in her native country.<ref name="gwiazdapolarna"/> Marie's second Nobel Prize enabled her to talk the French government into supporting the Radium Institute, which was built in 1914 and at which research was conducted in chemistry, physics, and medicine.<ref name="psb113"/> A month after accepting her 1911 Nobel Prize, she was hospitalized with depression and a kidney ailment.<ref name="Marie Curie Sc and Rec2"/> For most of 1912 she avoided public life, and spend some time in England with her friend and fellow physicist, [[Hertha Ayrton]].<ref name="Marie Curie Sc and Rec2"/> She returned to her lab only in December, after a break of about 14 months.<ref name="Marie Curie Sc and Rec2"/> |

|||

In 1897 and 1904, respectively, Curie gave birth to their daughters, [[Irène Joliot-Curie|Irène]] and [[Ève Curie]]. She later hired Polish [[governess]]es to teach her daughters her native language, and sent or took them on visits to Poland.<ref name="goldsmith"/> |

|||

In 1912 the [[Warsaw Scientific Society]] offered her the directorship of a new laboratory in Warsaw, but she declined, focusing on the developing Radium Institute, to be completed in August 1914 and a newly street named Rue Pierre-Curie.<ref name="psb113"/><ref name="Marie Curie Sc and Rec2"/> She visited Poland in 1913, welcomed in Warsaw, but with the visit being mostly ignored by the Russian authorities.<ref name="psb113"/> The Institute's development was interrupted by the coming war, as most researchers were drafted for into the [[French Army]], and it would fully resume its activities in 1919.<ref name="psb113"/><ref name="Marie Curie Sc and Rec2"/><ref name="Marie Curie War"/> |

|||

Curie was the first woman to be awarded a Nobel Prize. Eight years later, in 1911, she received the [[Nobel Prize in Chemistry]], "in recognition of her services to the advancement of chemistry by the discovery of the elements radium and polonium, by the isolation of radium and the study of the nature and compounds of this remarkable element." |

|||

[[File:Dyplom Sklodowska-Curie.jpg|thumb|170px|1911 Nobel Prize]] |

|||

A month after accepting her 1911 Nobel Prize, she was hospitalized with depression and a kidney ailment. |

|||

Curie was the first person to win or share two Nobel Prizes. She is one of only two people who have been awarded a Nobel Prize in two different fields, the other person being [[Linus Pauling]] (for chemistry and for peace). Nevertheless, in 1911 the [[French Academy of Sciences]] did not elect her to be a member by two votes. Elected instead was [[Édouard Branly]], an inventor who had helped [[Guglielmo Marconi]] develop the [[wireless telegraph]].<ref name="goldsmith9"/> It would be a doctoral student of Curie, [[Marguerite Perey]], who would become the first woman elected to membership in the Academy – over half a century later, in 1962. |

|||

===Pierre's death=== |

|||

On 19 April 1906 Pierre was killed in a street accident. Walking across the [[Rue Dauphine]] in heavy rain, he was struck by a horse-drawn vehicle and fell under its wheels; his skull was fractured.<ref name=obit/> While it has been speculated that previously he may have been weakened by prolonged radiation exposure, there are no indications that this contributed to the accident. |

|||

Curie was devastated by the death of her husband. She noted that, as of that moment she suddenly had become "an incurably and wretchedly lonely person". On {{nowrap|13 May}} 1906, the Sorbonne physics department decided to retain the chair that had been created for Pierre Curie and they entrusted it to Marie Curie together with full authority over the laboratory. This allowed her to emerge from Pierre's shadow. She became the first woman to become a professor at the Sorbonne, and in her exhausting work regime she sought a meaning for her life. |

|||

[[File:1911 Solvay conference.jpg|thumb|300px|At First [[Solvay Conference]] (1911), Curie (seated, 2nd from right) confers with [[Henri Poincaré]]. Standing, 4th from right, is [[Ernest Rutherford|Rutherford]]; 2nd from right, [[Albert Einstein|Einstein]]; far right, [[Paul Langevin]]]] |

|||

Recognition for her work grew to new heights, and in 1911 the [[Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences]] awarded her a second Nobel Prize, this time for Chemistry. A delegation of celebrated Polish men of learning, headed by world-famous novelist [[Henryk Sienkiewicz]], encouraged her to return to Poland and continue her research in her native country.<ref name="Wierzewski, p. 17"/> |

|||

In 1911 it was revealed that in 1910–11 Curie had conducted an affair of about a year's duration with physicist [[Paul Langevin]], a former student of Pierre Curie's.<ref name="robert10"/> He was a married man who was estranged from his wife. This resulted in a press scandal that was exploited by her academic opponents. Despite her fame as a scientist working for France, the public's attitude tended toward [[xenophobia]]—the same that had led to the [[Dreyfus affair]]–which also fueled false speculation that Curie was Jewish. She was five years older than Langevin and was portrayed in the tabloids as a home-wrecker.<ref name="goldsmith11"/> Later, Curie's granddaughter, [[Hélène Langevin-Joliot|Hélène Joliot]], married Langevin's grandson, Michel Langevin. |

|||

Curie's second Nobel Prize, in 1911, enabled her to talk the French government into funding the building of a private Radium Institute (''Institut du radium'', now the ''Institut Curie''), which was built in 1914 and at which research was conducted in chemistry, physics, and medicine. The Institute became a crucible of Nobel Prize winners, producing four more, including her daughter [[Irène Joliot-Curie]] and her son-in-law, [[Frédéric Joliot-Curie]]. |

|||

===World War I=== |

===World War I=== |

||

[[File:Marie Curie - Mobile X-Ray-Unit.jpg|thumb |

[[File:Marie Curie - Mobile X-Ray-Unit.jpg|thumb|Curie in a mobile x-ray vehicle]] |

||

During World War I, Marie saw a need for field radiological |

During World War I, Marie saw a need for field radiological centres near the front lines to assist battlefield surgeons.<ref name="Marie Curie War"/> After a quick study of radiology, anatomy and automotive mechanics she procured x-ray equipment, vehicles, auxiliary generators and developed mobile [[radiography]] units, which came to be popularly known as ''petites Curies'' ("Little Curies").<ref name="Marie Curie War"/> She became the Director of the [[Red Cross]] Radiology Service set up France's first military radiology centre, operational by late 1914.<ref name="Marie Curie War"/> Assisted at first by a military doctor and her 17-year old daughter Irene, she directed the installation of twenty mobile radiological vehicles and another 200 radiological units at field hospitals in the first year of the war.<ref name="psb113"/><ref name="Marie Curie War"/> Later, she began training other women as aides.<ref name="Marie Curie War2"/> |

||

In 1915 Marie produced hollow needles containing 'radium emanation', a colourless, radioactive gas given off by radium, later identified as [[radon]] to be used for sterilizing infected tissue.<ref name="Marie Curie War2"/> Marie provided the radium, from her own one gram supply.<ref name="Marie Curie War2"/> It is estimated that over one million wounded soldiers were treated with her x-ray units.<ref name="Marie Curie"/><ref name="psb113"/> Busy with this work, she carried out next to no scientific research during that period.<ref name="psb113"/> Despite all her efforts, Curie never received any formal recognition from the French government for her contribution during wartime.<ref name="Marie Curie War"/> |

|||

Also, promptly after the war started, she attempted to donate her gold Nobel Prize [[medal]]s to the war effort but the |

Also, promptly after the war started, she attempted to donate her gold Nobel Prize [[medal]]s to the war effort but the [[Banque de France|French National Bank]] refused to accept them.<ref name="Marie Curie War2"/> She did buy [[war bonds]], using her Nobel Prize money.<ref name="Marie Curie War2"/> She was also active member in committees of [[Poles in France|Polish Polonia in France]] dedicated to the Polish cause.<ref name="emigracja"/> During [[World War I]] she became a member of the Committee for a Free Poland (''Komitet Wolnej Polski'').<ref name="ossolineum"/> After the war she summarized her war time experiences in a book ''Radiology in War'' (1919).<ref name="Marie Curie War2"/> |

||

===Post-war years=== |

===Post-war years=== |

||

In 1921 |

In 1920, for the 25th anniversary of the discovery of radium, the French government established a stipend for her; the previous person to receive it was Pasteur.<ref name="psb113"/> In 1921 Marie was welcomed triumphantly when she toured the United States to raise funds for research on radium. [[Marie Mattingly Meloney|Mrs. William Brown Meloney]], after interviewing Marie, created a ''Marie Curie Radum Fund'' and raised money to buy 1 gram of radium, publicized her trip.<ref name="psb113"/><ref name="Marie Sklodowska Curie in America, 1921"/> In 1921 [[US President]] [[Warren G. Harding]] received her at the White House.<ref name="Madame Curie's Passion"/><ref name="The Radium Institute"/> The French government attempted to award her a [[Legion of Honour]], but she refused.<ref name="The Radium Institute"/> In 1922 she became a fellow of the [[French Academy of Medicine]].<ref name="psb113"/> She also travelled to other countries, appearing publicly and giving lectures in places such as Belgium, Brazil, Spain, and Czechoslovakia.<ref name=amudeu/> |

||

Led by Curie, the Institute became a crucible of Nobel Prize winners, producing four more, including her daughter [[Irène Joliot-Curie]] and her son-in-law, [[Frédéric Joliot-Curie]].<ref name="The Radium Institute 2"/> Eventually it became one of four major radioactivity-research laboratories, the others being the [[Cavendish Laboratory]], with [[Ernest Rutherford]]; the [[Institute for Radium Research, Vienna]], with [[Stefan Meyer (physicist)|Stefan Meyer]]; and the [[Max Planck Institute for Chemistry|Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Chemistry]], with [[Otto Hahn]] and [[Lise Meitner]].<ref name="The Radium Institute 2"/><ref name="Chemistry International — Newsmagazine for IUPAC"/> |

|||

Her second American tour, in 1929, succeeded in equipping the Warsaw [[Curie Institute, Warsaw|Radium Institute]], founded in 1925 with her sister Bronisława as director.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.aip.org/history/curie/radinst1.htm |title=Marie Curie — The Radium Institute (1919–1934) |publisher=Aip.org |accessdate=7 November 2011}}</ref> |

|||

In August 1922, Marie Curie became a member of the newly created [[International Commission for Intellectual Cooperation]] of the [[League of Nations]].<ref name="nytimes"/> In 1923 she wrote a biography of Pierre, entitled simply ''Pierre Curie''.<ref name="leg"/> In 1925 she visited Poland, to participate in the ceremony that laid foundations for the [[Curie Institute, Warsaw|Radium Institute]] in Warsaw.<ref name="psb113"/> Her second American tour, in 1929, succeeded in equipping the Warsaw Radium Institute with radium; it was opened in 1932 and her sister Bronisława became its director.<ref name="psb113"/><ref name="The Radium Institute"/> |

|||

These distractions from her scientific labors and the attendant publicity caused her much discomfort but provided resources needed for her work. |

|||

These distractions from her scientific labours and the attendant publicity caused her much discomfort but provided resources needed for her work.<ref name="The Radium Institute"/> |

|||

In her later years Curie headed the Curie Pavilion, a radioactivity laboratory created for her by the [[Pasteur Institute]] and the [[University of Paris]]. |

|||

It was one of four major radioactivity-research laboratories, the others being the [[Cavendish Laboratory]], with [[Ernest Rutherford]]; the [[Institute for Radium Research, Vienna]], with [[Stefan Meyer (physicist)|Stefan Meyer]]; and the [[Max Planck Institute for Chemistry|Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Chemistry]], with [[Otto Hahn]] and [[Lise Meitner]]. |

|||

<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.iupac.org/publications/ci/2011/3301/3_boudia.html |title=Chemistry International — Newsmagazine for IUPAC |publisher=Iupac.org |date=5 January 2011 |accessdate=7 November 2011}}</ref> |

|||

In 1933, when Russian physicists [[George Gamow]] and his wife — who had together been trying for two years to defect from the [[Soviet Union]] — attended the 7th [[Solvay Conference]] on physics, in [[Brussels]], Marie Curie and other physicists helped them extend their stay, and Gamow obtained temporary work at the [[Curie Institute (Paris)|Curie Institute]]. |

|||

===Death=== |

===Death=== |

||

[[File:Sklodowska-Curie statue, Warsaw.JPG|thumb| |

[[File:Sklodowska-Curie statue, Warsaw.JPG|thumb|upright|1935 statue, facing the Radium Institute, Warsaw]] |

||

Marie visited Poland for the last time in early 1934.<ref name="gwiazdapolarna"/><ref name="The Radium Institute 3"/> Only a few months later, on 4 July 1934, Marie died at the [[Sancellemoz]] [[Sanatorium]] in [[Passy, Haute-Savoie|Passy]], in [[Haute-Savoie]], eastern France, from [[aplastic anemia]] contracted from her long-term exposure to radiation.<ref name="psb113"/><ref name="iuniverse"/> The damaging effects of [[ionizing radiation]] were not then known, and much of her work had been carried out in a shed, without the safety measures that were later developed.<ref name="The Radium Institute 3"/> She had carried test tubes containing radioactive isotopes in her pocket<ref name="ShipmanWilson2012"/> and stored them in her desk drawer, remarking on the [[Radioluminescence|faint light]] that the substances gave off in the dark.<ref name="The Vertigo Years: Europe, 1900–1914"/> Marie was also exposed to x-rays from unshielded equipment while serving as a radiologist in field hospitals during the war.<ref name="Marie Curie War2"/> |

|||

She was interred at the cemetery in [[Sceaux, Hauts-de-Seine|Sceaux]], alongside her husband Pierre. Sixty years later, in 1995, in |

She was interred at the cemetery in [[Sceaux, Hauts-de-Seine|Sceaux]], alongside her husband Pierre.<ref name="psb113"/> Sixty years later, in 1995, in honour of their achievements, the remains of both were transferred to the [[Panthéon, Paris]]. She became the first – and so far the only – woman to be honoured with interment in the Panthéon on her own merits. |

||

Because of their levels of radioactivity, her papers from the 1890s are considered too dangerous to handle.<ref name="everything"/> Even her cookbook is highly radioactive.<ref name="everything"/> Her papers are kept in lead-lined boxes, and those who wish to consult them must wear protective clothing.<ref name="everything"/> |

|||

Her laboratory is preserved at the [[Musée Curie]]. |

|||

In her last year she worked on a book ''Radioactivity'', which was eventually published posthumously, in 1935.<ref name="The Radium Institute 3"/> |

|||

Because of their levels of radioactivity, her papers from the 1890s are considered too dangerous to handle. Even her cookbook is highly radioactive. They are kept in lead-lined boxes, and those who wish to consult them must wear protective clothing.<ref name="everything"/> |

|||

==Legacy== |

==Legacy== |

||

[[File:Lublin UMCS Pomnik Marii Curie-Skłodowskiej.jpg|thumb| |

[[File:Lublin UMCS Pomnik Marii Curie-Skłodowskiej.jpg|thumb|upright|Statue, [[Maria Curie-Skłodowska University]], [[Lublin]], Poland]] |

||

The physical and societal aspects of the work of the Curies contributed substantially to shaping the world of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Cornell University professor [[L. Pearce Williams|{{nowrap|L. Pearce}} Williams]] observes: |

The physical and societal aspects of the work of the Curies contributed substantially to shaping the world of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.<ref name="psb114"/> Cornell University professor [[L. Pearce Williams|{{nowrap|L. Pearce}} Williams]] observes: |

||

{{blockquote|The result of the Curies' work was epoch-making. Radium's radioactivity was so great that it could not be ignored. It seemed to contradict the principle of the conservation of energy and therefore forced a reconsideration of the foundations of physics. On the experimental level the discovery of radium provided men like Ernest Rutherford with sources of radioactivity with which they could probe the structure of the atom. As a result of Rutherford's experiments with alpha radiation, the nuclear atom was first postulated. In medicine, the radioactivity of radium appeared to offer a means by which cancer could be successfully attacked.<ref name=" |

{{blockquote|The result of the Curies' work was epoch-making. Radium's radioactivity was so great that it could not be ignored. It seemed to contradict the principle of the conservation of energy and therefore forced a reconsideration of the foundations of physics. On the experimental level the discovery of radium provided men like Ernest Rutherford with sources of radioactivity with which they could probe the structure of the atom. As a result of Rutherford's experiments with alpha radiation, the nuclear atom was first postulated. In medicine, the radioactivity of radium appeared to offer a means by which cancer could be successfully attacked.<ref name="Williams332"/>}} |

||

If the work of Marie Curie helped overturn established ideas in physics and chemistry, it has had an equally profound effect in the societal sphere. To attain her scientific achievements, she had to overcome barriers that were placed in her way because she was a woman, in both her native and her adoptive country. This aspect of her life and career is highlighted in [[Françoise Giroud]]'s ''Marie Curie: A Life'', which emphasizes Marie's role as a feminist precursor.<ref name="gwiazdapolarna"/> She was ahead of her time, emancipated and independent. |

|||

(See [[physics]], [[conservation of energy]], [[Ernest Rutherford]], [[atom]], [[alpha decay]], [[atomic nucleus]].) |

|||

She was also known for her honesty and moderate life style.<ref name="psb112"/><ref name="psb114"/> Having received a small scholarship in 1893, she returned it in 1897 as soon as she begun earning her keep.<ref name="psb111"/><ref name="Marie Curie — Student in Paris 2"/> Much of her first Noble Prize money was given away to friends, family, students and research associates.<ref name="gwiazdapolarna"/> In an unusual decision, Marie intentionally refrained from patenting the radium-isolation process, so that the scientific community could do research unhindered.<ref name="robert8"/> She insisted that monetary gifts and awards are given to the scientific institutions she was affiliated with, rather than herself.<ref name="psb114"/> She and her husband often refused awards and medals.<ref name="psb112"/> [[Albert Einstein]] is reported to have remarked that she was probably the only person who was not corrupted by the fame that she had won.<ref name="gwiazdapolarna"/> |

|||

==Awards== |

==Awards, honours and tributes== |

||

[[File:Panthéon Pierre et Marie Curie.JPG|thumb|upright|Tomb of Pierre and Marie Curie]] |

|||

Marie Curie was the first woman to win a Nobel prize and the first person to win two Nobel Prizes. |

|||

As one of the most famous female scientists to date, Marie Curie has become an icon in the scientific world and has received tributes from across the globe, even in the realm of [[pop culture]].<ref name="Borzendowski2009-36"/> In a 2009 poll carried out by ''[[New Scientist]]'', Marie Curie was voted the "most inspirational woman in science". Curie received 25.1 per cent of all votes cast, nearly twice as many as second-place [[Rosalind Franklin]] (14.2 per cent).<ref name="Most inspirational woman scientist revealed"/><ref name="Marie Curie voted greatest female scientist"/> |

|||

Poland and France declared 2011 the Year of Marie Curie, and the [[United Nations]] declared that this would be the International Year of Chemistry.<ref name=cosm/> An artistic installation celebrating "Madame Curie" filled the [[Jacobs Gallery]] at [[San Diego]]'s [[Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego|Museum of Contemporary Art]].<ref name="Madame Curie art"/> On 7 November, [[Google]] celebrated her birthday with a special [[Google Doodle]].<ref name="Marie Curie’s 144th Birthday Google Doodle"/> On 10 December, the [[New York Academy of Sciences]] celebrated the centenary of Marie Curie's second [[Nobel prize]] in the presence of [[Princess Madeleine, Duchess of Hälsingland and Gästrikland|Princess Madeleine of Sweden]].<ref name="Princess Madeleine attends celebrations to mark anniversary of Marie Curie's second Nobel Prize"/> |

|||

*[[Nobel Prize in Physics]] (1903) |

|||

*[[Davy Medal]] (1903) |

|||

*[[Matteucci Medal]] (1904) |

|||

*[[Elliott Cresson Medal]] (1909) |

|||

*[[Nobel Prize in Chemistry]] (1911) |

|||

*[[Benjamin Franklin Medal (American Philosophical Society)|Franklin Medal]] of the [[American Philosophical Society]] (1921)<ref>{{cite journal|url=http://www.jstor.org/stable/pdfplus/984523.pdf |title=Minutes |journal=[[Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society]] |volume=60 |issue=4 |year=1921 |page=p.xxii |id={{JSTOR|984523}} |publisher=American Philosophical Society |accessdate=26 November 2011}}</ref> |

|||

Marie Curie was the first woman to win a Nobel prize and the first person to win two Nobel Prizes. Some of the awards she accepted during her life include: |

|||

The Curies reportedly used part of their award money to replace wallpaper in their Parisian home and install modern plumbing into a bathroom.<ref name="wallechinsky"/> |

|||

* [[Nobel Prize in Physics]] (1903)<ref name="psb112"/> |

|||

* [[Davy Medal]] (1903, with Pierre)<ref name="amudeu"/><ref name="CurieSheean1999"/> |

|||

* [[Matteucci Medal]] (1904; with Pierre)<ref name="CurieSheean1999"/> |

|||

* [[Elliott Cresson Medal]] (1909)<ref name="winners"/> |

|||

* [[Nobel Prize in Chemistry]] (1911)<ref name="gwiazdapolarna"/> |

|||

* [[Benjamin Franklin Medal (American Philosophical Society)|Franklin Medal]] of the [[American Philosophical Society]] (1921)<ref name="Minutes"/> |

|||

In 1995, she became the first woman to be entombed on her own merits in the [[Panthéon, Paris]].<ref name="nytimes"/> |

|||

The [[curie]] (symbol '''Ci'''), a unit of radioactivity, is named in honour of her and Pierre (although the commission which agreed on the name never clearly stated whether the standard was named after Pierre, Marie or both of them).<ref name="How the Curie Came to Be"/> The element with atomic number 96 was named [[curium]].<ref name="Curium"/> Three radioactive minerals are also named after the Curies: [[curite]], [[sklodowskite]], and [[cuprosklodowskite]].<ref name="Borzendowski2009-37"/> She received numerous honorary degrees from universities across the world.<ref name="The Radium Institute"/> In Poland, she had received honorary doctorates from the [[Lwów Polytechnic]] (1912), [[Poznań University]] (1922), [[Kraków]]'s [[Jagiellonian University]] (1924), and the [[Warsaw Polytechnic]] (1926).<ref name="cosm"/> |

|||

==Honors== |

|||

[[File:Soviet Union stamp 1987 CPA 5875.jpg|thumb|[[Soviet Union|Soviet]] postage stamp]] |

|||

* Madame Curie was decorated with the French [[Legion of Honor]]. In Poland, she had received honorary doctorates from the [[Lwów Polytechnic]] (1912), [[Poznań University]] (1922), [[Kraków]]'s [[Jagiellonian University]] (1924), and the [[Warsaw Polytechnic]] (1926). |

|||

Numerous locations around the world are named after her.<ref name="Borzendowski2009-37"/> In 2007 [[Pierre et Marie Curie (Paris Métro)|a metro station in Paris]] was renamed to honour both of the Curies.<ref name="Borzendowski2009-37"/> Polish nuclear research [[Maria reactor|reactor Maria]] is named after her.<ref name="IEA - reaktor Maria"/> Outside Earth, the [[7000 Curie]] asteroid is also named after her.<ref name="Borzendowski2009-37"/> A [[KLM]] [[McDonnell Douglas MD-11]] (registration PH-KCC) is named in her honour.<ref name="Picture of the McDonnell Douglas MD-11 aircraft"/> |

|||

* Their elder daughter, [[Irène Joliot-Curie]], won a Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1935 for discovering that aluminum could be made radioactive and emit neutrons when bombarded with alpha rays. Their younger daughter, [[Ève Curie]], later wrote a biography of her mother. |

|||

Similarly, a number of institutions bear her name, starting with the two Curie institutes - the [[Curie Institute, Warsaw|Maria Skłodowska–Curie Institute of Oncology]], in Warsaw and the [[Curie Institute (Paris)|Institut Curie]] in Paris. She is the patron of the [[Maria Curie-Skłodowska University]], in [[Lublin]], founded in 1944; and [[Pierre and Marie Curie University]], in Paris, established in 1971. There are two museums dedicated to Marie Curie. In 1967 [[Maria Skłodowska-Curie Museum|a museum devoted to Curie]] was established in Warsaw's "[[Warsaw New Town|New Town]]", at her birthplace on ''ulica Freta'' (Freta Street).<ref name="gwiazdapolarna"/> Her laboratory is preserved at the [[Musée Curie]] in Paris, and has been open to public since 1992..<ref name="curie"/> |

|||

* Michalina Mościcka, wife of Polish President [[Ignacy Mościcki]], unveiled a 1935 statue of Marie Curie before Warsaw's Radium Institute, which had been founded by Marie Curie. Within a decade, during the 1944 [[Warsaw Uprising]], the monument suffered damage from gunfire. After the war, when maintenance was done, it was decided to leave the bullet marks on the statue and its pedestal.<ref name="Wierzewski, p. 17"/> |

|||

Several works of art bear her likeness, or are dedicated to her. Michalina Mościcka, wife of Polish President [[Ignacy Mościcki]], unveiled a 1935 statue of Marie Curie before Warsaw's Radium Institute.<ref name="gwiazdapolarna"/> Within a decade, during the 1944 [[Warsaw Uprising]], the monument suffered damage from gunfire. After the war, when maintenance was done, it was decided to leave the bullet marks on the statue and its pedestal.<ref name="gwiazdapolarna"/> In 1955 [[Jozef Mazur]] created a stained glass panel of her, the [[Maria Skłodowska-Curie Medallion]], featured in the [[University at Buffalo]] Polish Room.<ref name="buffalo"/> |

|||

* In 1967 a museum devoted to Curie was established in Warsaw's "[[Warsaw New Town|New Town]]", at her birthplace on ''ulica Freta'' (Freta Street).<ref name="Wierzewski, p. 17"/> |

|||

Books dedicated to her include ''Madame Curie'' (1938), written by her daughter, Ève.<ref name=cosm/> In 1987 [[Françoise Giroud]] wrote a biography, ''Marie Curie: A Life''.<ref name=cosm/> In 2005, [[Barbara Goldsmith]] wrote ''Obsessive Genius: The Inner World of Marie Curie''.<ref name=cosm/> In 2011, another book appeared, the ''Radioactive: Marie and Pierre Curie, a Tale of Love and Fallout '', by [[Lauren Redniss]].<ref name="Radioactive: Marie and Pierre Curie, a Tale of Love and Fallout"/> |

|||

* The year 2011 was declared the Year of Marie Curie by [[Poland]] and [[France]]. An artistic installation celebrating "Madame Curie" filled the [[Jacobs Gallery]] at [[San Diego]]'s [[Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego|Museum of Contemporary Art]].<ref name="Madame Curie art"/> |

|||

[[Greer Garson]] and [[Walter Pidgeon]] starred in the 1943 U.S. Oscar-nominated film, ''[[Madame Curie (film)|Madame Curie]]'', based on her life.<ref name="leg"/> More recently, in 1997, a French film about Pierre and Marie Curie was released, ''[[Les Palmes de M. Schutz]]''. It was adapted from a play of the same name. In the film, Marie Curie was played by [[Isabelle Huppert]].<ref name="Les-Palmes-de-M-Schutz - Trailer - Cast - Showtimes - NYTimes.com"/> |

|||

* [[Rue Madame Curie]], a street in [[Beirut]], [[Lebanon]], is named in her honor. |

|||

Curie's likeness also has appeared on bills, stamps and coins around the world.<ref name="Borzendowski2009-37"/> She was featured on the Polish late-1980s 20,000-''[[złoty]]'' [[banknote]]<ref name="Council1997"/> as well as on the last French 500-[[₣|franc]] note, before the franc was replaced by the euro.<ref name="Letcher2003"/> |

|||

* On 7 November 2011, [[Google]] celebrated her birthday with a special [[Google Doodle]].<ref name="Marie Curie’s 144th Birthday Google Doodle"/> |

|||

==Notes== |

|||

* On 10 December 2011, the [[New York Academy of Sciences]] celebrated the centenary of Marie Curie's second [[Nobel prize]] in the presence of [[Princess Madeleine, Duchess of Hälsingland and Gästrikland|Princess Madeleine of Sweden]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.kungahuset.se/royalcourt/royalfamily/latestnews/news/princessmadeleineattendscelebrationstomarkanniversaryofmariecuriessecondnobelprize.5.70e7de59130bc8da54e800013910.html|title=Princess Madeleine attends celebrations to mark anniversary of Marie Curie's second Nobel Prize|publisher=Sveriges Kungahus|accessdate=23 February 2012}}</ref> |

|||

'''a.''' {{Note label|a|a|none}} Poland had been partitioned in the 18th century among Russia, Prussia and Austria, and it was Skłodowska–Curie's hope that naming the element after her native country would bring world attention to its lack of independence. [[Polonium]] may have been the first [[chemical element]] named to highlight a political question.<ref name="independence"/> |

|||

'''b.''' {{Note label|b|b|none}} Sources tend to vary with regards to the field of her second degree. [[Tadeusz Estreicher]] in his 1938 entry in the [[Polish Biographical Dictionary]] writes that while many sources state she earned a degree in mathematics, this is incorrect, and her second degree was in chemistry.<ref name="psb111"/> |

|||

==Tributes== |

|||

[[File:Panthéon de Paris - 02.jpg|thumb|150px|[[Panthéon, Paris]]]] |

|||

[[File:Panthéon Pierre et Marie Curie.JPG|thumb|150px|Tomb of Pierre and Marie Curie]] |

|||