Elf: Difference between revisions

Alarichall (talk | contribs) →Elves in names: picture of Alden Valley added |

Alarichall (talk | contribs) new section added on the place of elves in Christian thought. This deserves prominence because almost all evidence about elves comes from Christian cultures. I know it makes the entry longer, but I'll save space in the following edits! |

||

| Line 18: | Line 18: | ||

In medieval Germanic-speaking cultures, elves seem generally to have been thought of as a group of beings with magical powers and supernatural beauty, ambivalent towards everyday people and capable of either helping or hindering them. However, the precise character of beliefs in elves across the Germanic-speaking world has varied considerably across time, space, and different cultures. |

In medieval Germanic-speaking cultures, elves seem generally to have been thought of as a group of beings with magical powers and supernatural beauty, ambivalent towards everyday people and capable of either helping or hindering them. However, the precise character of beliefs in elves across the Germanic-speaking world has varied considerably across time, space, and different cultures. |

||

In medieval Christian cultures, elves were sometimes integrated into Christian mythology by being identified as [[demons]].<ref>{{Harvnb|Jolly|1992|p=172}} (in Neusner ed.); Hall 2007, 69-74 on English evidence and 98 fn 10 on German evidence; Haukur Þorgeirsson 2011, 54-58 on Icelandic evidence.</ref> However, from our earliest evidence for elves onwards to the present day, it is clear that the idea of elves as demons has in most Germanic-speaking cultures existed in parallel to a view of elves as being supernatural beings outside Christian mythology.<ref>Hall 2007, 172-75.</ref> |

|||

In Old Norse mythological texts, elves seem at least at times to be among the pagan gods. In [[Anglo-Saxon England]], elves are most often attested in [[Old English language|Old English]] [[Gloss (annotation)|glosses]] on Latin words for [[nymph|nymphs]] and in medical texts, which attest to elves afflicting humans and [[livestock]] with illnesses (these illnesses have widely been referred to in both scholarly and popular texts as 'elfshot', but this word is not attested in Old English, nor very widely in other primary sources).<ref>Hall 2007, 96-118.</ref> This does not necessarily mean that these elves were seen as demonic, however.<ref>Hall 2007, 172-75.</ref> |

In Old Norse mythological texts, elves seem at least at times to be among the pagan gods. In [[Anglo-Saxon England]], elves are most often attested in [[Old English language|Old English]] [[Gloss (annotation)|glosses]] on Latin words for [[nymph|nymphs]] and in medical texts, which attest to elves afflicting humans and [[livestock]] with illnesses (these illnesses have widely been referred to in both scholarly and popular texts as 'elfshot', but this word is not attested in Old English, nor very widely in other primary sources).<ref>Hall 2007, 96-118.</ref> This does not necessarily mean that these elves were seen as demonic, however.<ref>Hall 2007, 172-75.</ref> |

||

| Line 47: | Line 45: | ||

Elves appear in some place-names, though it is hard to be sure how many as a variety of other words, and personal names, can appear similar to ''elf'' in early medieval and especially later evidence. The clearest English example is ''[[Elveden]]'' ('elves' hill', Suffolk); other examples may be ''[[Eldon Hill]]'' ('Elves' hill', Derbyshire); and ''[[Alden Valley]]'' ('elves' valley', Lancashire). These seem to associate elves fairly consistently with woods and valleys.<ref>Hall 2007, 64-66</ref> |

Elves appear in some place-names, though it is hard to be sure how many as a variety of other words, and personal names, can appear similar to ''elf'' in early medieval and especially later evidence. The clearest English example is ''[[Elveden]]'' ('elves' hill', Suffolk); other examples may be ''[[Eldon Hill]]'' ('Elves' hill', Derbyshire); and ''[[Alden Valley]]'' ('elves' valley', Lancashire). These seem to associate elves fairly consistently with woods and valleys.<ref>Hall 2007, 64-66</ref> |

||

== Relationship of elves to Christian cosmologies == |

|||

Almost all of our textual sources about elves were written by Christians—whether Anglo-Saxon monks, medieval Icelandic poets, early modern ballad-singers, or nineteenth-century folklore collectors. Elves have, therefore, been a part of Christian societies throughout their recorded history and they have a complex relationship between elves and mainstream Christian thought. This point was brought to the fore by [[Karen Jolly]] and subsequently [[Tom Shippey]].<ref>Jolly 1996; Shippey 2005.</ref> (Previously, neither scholars wishing to recover lost pre-Christian traditions nor Christians wishing to think of their religion as orthodox and Bible-based had focused on these complexities.) |

|||

Across recorded history, people have taken three main approaches to integrating elves into Christian cosmology (though of course there are no rigid distinctions between these): |

|||

# '''Identifying elves with the [[demon|demons]] of Judaeo-Christian-Mediterranean tradition.'''<ref>e.g. {{Harvnb|Jolly|1992|p=172}}</ref> |

|||

## Thus in English material, the Old English poem ''[[Beowulf]]'' lists elves among the monstrous races springing from Cain’s murder of Abel;<ref>Hall 2007, 69-74.</ref> in the late fourteenth-century ''Wife of Bath’s Tale'', Geoffrey Chaucer equates male elves with [[incubus|incubi]];<ref>Hall 2007, 162.</ref> andn the [[Witch trials in early modern Scotland|early moden Scottish witchcraft trials]], confessions by people accused of witchcraft to encounters with elves were often interpreted by prosecutors as evidence of encounters with the [[Devil]].<ref>Hall 2005, 30-32.</ref> |

|||

## In medieval Scandinavia, [[Snorri Sturluson]] wrote in his ''[[Prose Edda]]'' of [[Dökkálfar and Ljósálfar|''ljósálfar'' and ''døkkálfar'']] ('light-elves and dark-elves'), the ''ljósálfar'' living in the heavens and the ''døkkálfar'' under the earth. The concensus of modern scholarship is that Snorri’s elves are based on angels and demons of Christian cosmology.<ref>Hall 2007, 23-26; Gunnell 2007, 127-28; Shippey 2005, 180-81.</ref> |

|||

## Elves turn up as demonic forces in prayers in English, German, and Scandinavian traditions.<ref>Hall 2007, 69-74 on English evidence and 98 fn 10 on German evidence; Haukur Þorgeirsson 2011, 54-58 on Icelandic evidence.</ref> |

|||

# '''Viewing elves as being more or less like (supernaturally powerful) people, and more or less outside Christian cosmology.'''<ref>e.g. Hall 2007, 172-75.</ref> For example, the early modern Scottish people who, when prosecuted as witches, confessed to encountering elves seem not to have thought of themselves as having dealings with the [[Devil]]. Nineteenth-century Icelandic (and to some extent Scandinavian) folklore about [[Huldufólk|elves]] mostly presents them as a human agricultural community parallel to the visible human community, that may or may not be Christian.<ref>Shippey 2005, 161-68; Alver and Selberg 1987.</ref> |

|||

# '''Attempting to integrate elves into Christian cosmology without demonising them.'''<ref>e.g. Shippey 2005.</ref> The most impressive such attempts are serious (if unusual) theological treatises, as in the Icelandic ''[[Tíðfordrif]]'' (1644) by [[Jón Guðmundsson lærði]] or, in Scotland, [[Robert Kirk (folklorist)|Robert Kirk]]’s ''Secret Commonwealth of Elves, Fauns and Fairies'' (1691). Other such thought appears in passing, as in the late thirteenth-century ''[[South English Legendary]]'' or some Icelandic folktales, which explain elves as angels that sided neither with [[Lucifer]] nor with God, and were banished by God to earth rather than hell, or the Icelandic folktale in which elves are the lost children of Eve.<ref>Hall 2007, 75; Shippey 2005, 174, 185-86.</ref> |

|||

== Norse Eddas == |

== Norse Eddas == |

||

| Line 272: | Line 285: | ||

==References== |

==References== |

||

{{Refbegin}} |

{{Refbegin}} |

||

* Alver, Bente Gullveig and Torunn Selberg, ‘Folk Medicine as Part of a Larger Concept Complex’, Arv, 43 (1987), 21–44. |

|||

* *{{cite book|last=Coghlan|first=Ronan|title=Handbook of Fairies|place=Milverton|publisher=Capall Bann|year=2002|url=|isbn=1898307911}} |

* *{{cite book|last=Coghlan|first=Ronan|title=Handbook of Fairies|place=Milverton|publisher=Capall Bann|year=2002|url=|isbn=1898307911}} |

||

* [[Jacob Grimm|Grimm, Jacob]], ''[[Deutsche Mythologie]]'' (1835). |

* [[Jacob Grimm|Grimm, Jacob]], ''[[Deutsche Mythologie]]'' (1835). |

||

| Line 277: | Line 291: | ||

**{{cite book|last=Grimm|others=Stallybrass (tr.)|title=Teutonic mythology|volume=3|year=1883|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=c8AoAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA1246|pages=1246ff.}} |

**{{cite book|last=Grimm|others=Stallybrass (tr.)|title=Teutonic mythology|volume=3|year=1883|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=c8AoAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA1246|pages=1246ff.}} |

||

**{{cite book|last=Grimm|others=Stallybrass (tr.)|title=Teutonic mythology|volume=4|year=1888|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=uy1LAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA1419|chapter=Supplement|pages=1407–1435}} |

**{{cite book|last=Grimm|others=Stallybrass (tr.)|title=Teutonic mythology|volume=4|year=1888|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=uy1LAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA1419|chapter=Supplement|pages=1407–1435}} |

||

* Gunnell, Terry, ‘How Elvish were the Álfar?’, in ''Constructing Nations, Reconstructing Myth: Essays in Honour of T. A. Shippey'', ed. by Andrew Wawn with Graham Johnson and John Walter, Making the Middle Ages, 9 (Turnhout: Brepols, 2007), pp. 111–30. |

|||

*{{citation|last=Hall|first=Alaric Timothy Peter|title=The Meanings of Elf and Elves in Medieval England|year=2004|url=http://www.alarichall.org.uk/ahphdful.pdf}} (Ph.D. thesis, University of Glasgow) |

*{{citation|last=Hall|first=Alaric Timothy Peter|title=The Meanings of Elf and Elves in Medieval England|year=2004|url=http://www.alarichall.org.uk/ahphdful.pdf}} (Ph.D. thesis, University of Glasgow) |

||

*Hall, Alaric, 'Getting Shot of Elves: Healing, Witchcraft and Fairies in the Scottish Witchcraft Trials', ''Folklore'', 116 (2005), 19-36 (http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0015587052000337699), http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/5597. |

|||

*{{cite book|last=Hall|first=Alaric|title=Elves in Anglo-saxon England: Matters of Belief, Health, Gender and Identity|publisher= Boydell Press|year=2007|url=http://www.libgen.net/view.php?id=383363|isbn=1843832941}} |

*{{cite book|last=Hall|first=Alaric|title=Elves in Anglo-saxon England: Matters of Belief, Health, Gender and Identity|publisher= Boydell Press|year=2007|url=http://www.libgen.net/view.php?id=383363|isbn=1843832941}} |

||

*Haukur Þorgeirsson, 'Álfar í gömlum kveðskap', ''Són'', 9 (2011), 49-61, http://hi.is/~haukurth/Haukur_2011_Alfar_Son.pdf. |

*Haukur Þorgeirsson, 'Álfar í gömlum kveðskap', ''Són'', 9 (2011), 49-61, http://hi.is/~haukurth/Haukur_2011_Alfar_Son.pdf. |

||

| Line 290: | Line 306: | ||

*{{cite book|last=Scott|first=Walter|title=Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border|publisher=James Ballantyne|volume=2|year=1803|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=gQwUAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA266}} |

*{{cite book|last=Scott|first=Walter|title=Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border|publisher=James Ballantyne|volume=2|year=1803|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=gQwUAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA266}} |

||

*{{cite journal|last=Shippey|first=TA|authorlink=Tom Shippey|title=Light-elves, Dark-elves, and Others: Tolkien's Elvish Problem|journal=Tolkien Studies volume=1|year=2004|url=http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/tks/summary/v001/1.1shippey.html|pages=1–15|doi=10.1353/tks.2004.0015}} |

*{{cite journal|last=Shippey|first=TA|authorlink=Tom Shippey|title=Light-elves, Dark-elves, and Others: Tolkien's Elvish Problem|journal=Tolkien Studies volume=1|year=2004|url=http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/tks/summary/v001/1.1shippey.html|pages=1–15|doi=10.1353/tks.2004.0015}} |

||

* Shippey, Tom, ‘Alias oves habeo: The Elves as a Category Problem’, in ''The Shadow-Walkers: Jacob Grimm’s Mythology of the Monstrous'', ed. by Tom Shippey, Medieval and Renaissance Texts and Studies, 291/Arizona Studies in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, 14 (Tempe, AZ: Arizon Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, 2005), pp. 157–87. |

|||

*{{cite book|last=Syndergaard|first=Larry E.|title=English Translations of the Scandinavian Medieval Ballads: An Analytical Guide and Bibliography|publisher=Nordic Institute of Folklore|year=1995|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=Nax3tgAACAAJ|isbn=9529724160}} |

*{{cite book|last=Syndergaard|first=Larry E.|title=English Translations of the Scandinavian Medieval Ballads: An Analytical Guide and Bibliography|publisher=Nordic Institute of Folklore|year=1995|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=Nax3tgAACAAJ|isbn=9529724160}} |

||

{{Refend}} |

{{Refend}} |

||

Revision as of 12:14, 2 May 2014

| |

| Grouping | Legendary creature |

|---|---|

| Region | Europe |

An elf (plural: elves) is a type of supernatural being in Germanic mythology and folklore.[1] Reconstructing the early concept of an elf depends almost entirely on texts in Old English or relating to Norse mythology.[2] Later evidence for elves appears in diverse sources such as medical texts, prayers, ballads, and folktales.

In medieval Germanic-speaking cultures, elves seem generally to have been thought of as a group of beings with magical powers and supernatural beauty, ambivalent towards everyday people and capable of either helping or hindering them. However, the precise character of beliefs in elves across the Germanic-speaking world has varied considerably across time, space, and different cultures.

In Old Norse mythological texts, elves seem at least at times to be among the pagan gods. In Anglo-Saxon England, elves are most often attested in Old English glosses on Latin words for nymphs and in medical texts, which attest to elves afflicting humans and livestock with illnesses (these illnesses have widely been referred to in both scholarly and popular texts as 'elfshot', but this word is not attested in Old English, nor very widely in other primary sources).[3] This does not necessarily mean that these elves were seen as demonic, however.[4]

Elves are also prominently associated with sexual threats, seducing people and causing them harm. A number of ballads in the British Isles and Scandinavia, perhaps stemming from the medieval period, describe human encounters with elves, elf-maids, etc. Related ballads on these themes are often attested over several countries. Some common motifs, which may also be seen in English, Scottish and Scandinavian folklore, are elves enticing men with their dance, and causing death.[5]

In English literature of the Elizabethan era, elves became conflated with the fairies of Romance culture, so that the two terms began to be used interchangeably. German romanticist writers were influenced by this (particularly Shakespearean) notion of the "elf," and reimported the word Elf in that context into the German language. In Scandinavia, probably through a process of euphemism, elves often came to be known as (or were conflated with) the beings called the huldra or huldufólk. Meanwhile, German folklore has tended to see the conflation of elves with dwarves.[6]

The "Christmas elves" of contemporary popular culture are of relatively recent tradition, popularized during the late 19th century in the United States, in publications such as Godey's Lady's Book. Elves entered the 20th-century high fantasy genre in the wake of works published by authors such as J. R. R. Tolkien, for which, see Elf (Middle-earth).

Etymology

The English word elf is from the Old English word most often attested as ælf (whose plural would have been *ælfe). Although this word took a variety of forms in different Old English dialects, these converged on the form elf during the Middle English period.[7] During the Old English period, separate forms were used for female elves (such as ælfen, putatively from common Germanic *ɑlβ(i)innjō), but during the Middle English period the word elf came routinely to include female beings.[8]

The main medieval Germanic cognates of elf are Old Norse alfr, plural álfar and Old High German alp, plural alpî, elpî (alongside the feminine elbe).[9] These words must come from Common Germanic, the ancestor-language of English, German, and the Scandinavian languages: the Common Germanic forms must have been *ɑlβi-z and ɑlβɑ-z.[10]

Germanic *ɑlβi-z~*ɑlβɑ-z is generally agreed to be cognate with the Latin albus ('(matt) white'), Old Irish ailbhín (‘flock’); Albanian elb (‘barley’); and Germanic words for ‘swan’ such as Old English ylfetu and Modern Icelandic álpt. These all come from an Indo-European base *albh-, and seem to be connected by whiteness. The Germanic word presumably originally meant 'white person', perhaps as a euphemism. Jakob Grimm thought that whiteness implied positive moral connotations, and noting Snorri Sturluson's ljósálfar suggested that elves were divinities of light. Alaric Hall, noting that the cognates suggest matt white, has instead tentatively suggested that later evidence associating both elves and whiteness with feminine beauty may indicate that it was this beauty that gave elves their name.[11] A connection to the Rbhus, semi-divine craftsmen in Indian mythology, was also suggested by Kuhn, in 1855.[12][13] While still sometimes repeated, however, this idea is not widely accepted.[14]

Elves in names

Throughout the medieval Germanic languages, elf was one of the nouns that was used in personal names, almost invariably as a first element. These names may have been influenced by Celtic names beginning in Albio- such as Albiorix.

Personal names provide the only evidence for elf in Gothic, which must have had the word *albs (plural *albeis). The most famous such name is Alboin. Old English names in elf- include the cogname of Alboin Ælfwine ('elf-friend', m.), Ælfric ('elf-powerful', m.), and Ælfweard (m.) and Ælfwaru (f.) ('elf-guardian). The only widespread survivor of these in modern English is Alfred (Old English Ælfrēd). German examples are Alberich, Alphart and Alphere (father of Walter of Aquitaine)[15][16] and Icelandic examples include Álfhildur. It is generally agreed that these names indicate that elves were positively regarded in early Germanic culture. Other words for supernatural beings in personal names almost all denote pagan gods, suggesting that elves were in a similar category of beings.[17]

Elves appear in some place-names, though it is hard to be sure how many as a variety of other words, and personal names, can appear similar to elf in early medieval and especially later evidence. The clearest English example is Elveden ('elves' hill', Suffolk); other examples may be Eldon Hill ('Elves' hill', Derbyshire); and Alden Valley ('elves' valley', Lancashire). These seem to associate elves fairly consistently with woods and valleys.[18]

Relationship of elves to Christian cosmologies

Almost all of our textual sources about elves were written by Christians—whether Anglo-Saxon monks, medieval Icelandic poets, early modern ballad-singers, or nineteenth-century folklore collectors. Elves have, therefore, been a part of Christian societies throughout their recorded history and they have a complex relationship between elves and mainstream Christian thought. This point was brought to the fore by Karen Jolly and subsequently Tom Shippey.[19] (Previously, neither scholars wishing to recover lost pre-Christian traditions nor Christians wishing to think of their religion as orthodox and Bible-based had focused on these complexities.)

Across recorded history, people have taken three main approaches to integrating elves into Christian cosmology (though of course there are no rigid distinctions between these):

- Identifying elves with the demons of Judaeo-Christian-Mediterranean tradition.[20]

- Thus in English material, the Old English poem Beowulf lists elves among the monstrous races springing from Cain’s murder of Abel;[21] in the late fourteenth-century Wife of Bath’s Tale, Geoffrey Chaucer equates male elves with incubi;[22] andn the early moden Scottish witchcraft trials, confessions by people accused of witchcraft to encounters with elves were often interpreted by prosecutors as evidence of encounters with the Devil.[23]

- In medieval Scandinavia, Snorri Sturluson wrote in his Prose Edda of ljósálfar and døkkálfar ('light-elves and dark-elves'), the ljósálfar living in the heavens and the døkkálfar under the earth. The concensus of modern scholarship is that Snorri’s elves are based on angels and demons of Christian cosmology.[24]

- Elves turn up as demonic forces in prayers in English, German, and Scandinavian traditions.[25]

- Viewing elves as being more or less like (supernaturally powerful) people, and more or less outside Christian cosmology.[26] For example, the early modern Scottish people who, when prosecuted as witches, confessed to encountering elves seem not to have thought of themselves as having dealings with the Devil. Nineteenth-century Icelandic (and to some extent Scandinavian) folklore about elves mostly presents them as a human agricultural community parallel to the visible human community, that may or may not be Christian.[27]

- Attempting to integrate elves into Christian cosmology without demonising them.[28] The most impressive such attempts are serious (if unusual) theological treatises, as in the Icelandic Tíðfordrif (1644) by Jón Guðmundsson lærði or, in Scotland, Robert Kirk’s Secret Commonwealth of Elves, Fauns and Fairies (1691). Other such thought appears in passing, as in the late thirteenth-century South English Legendary or some Icelandic folktales, which explain elves as angels that sided neither with Lucifer nor with God, and were banished by God to earth rather than hell, or the Icelandic folktale in which elves are the lost children of Eve.[29]

Norse Eddas

The Eddas describe the aboriginal spiritual traditions of the Norse culture, especially Iceland and Norway.

Creation

The Elder Edda couples the Æsir race of gods and álfar race of elves, mentioning the two classes side-by-side in a number of instances.[30] (This juxtaposition also recurs in Old English ês and ylfe). The association sometimes extends to a third class, the Vanir gods, as in the poem För Skírnis (or Skirnir's Journey).[32][33]

Elves are mentioned as a distinct race, separate from other races such as the Æsir gods, Vanir gods, giants (jǫtnar), dwarves, and mankind (męnn); and the elves evidently do not count among the "gods" (goð) or the "higher powers" (ginn-regin) — in Alvíssmál ("The Sayings of All-Wise").[a] The poem also mentions as a race the denizens of Hel, which may be marginally relevant, insofar as Grimm identifies them with the "dark elves" as distinct from "black elves" in his attempt to rationally explain that there may originally have been three sub-classes of elves. (See #Light-elves and dark-elves below).

Lokasenna relates that a large group of Æsir and elves had assembled at Ægir's court for a banquet, and from the many names named here, veritably "most of the Scandinavian pantheon," scholars have attempted to find a name of the elf here in vain.[34] It has been remarked that no individual elf with a known name has passed down to our knowledge,[35] though some suggest exceptions to this, such as the smith hero Völundr being called "Ruler of Elves" (vísi álfa)[36][b] Völundr also referred to as 'One among the Elven Folk' (álfa ljóði), in the poem Völundarkviða, whose later prose introduction also identifies him as the son of a king of 'Finnar', an Arctic people respected for their shamanic magic (most likely, the Sami).

Just as elves are one of several races of beings, the elf's home Alfheim is assumed to be one of the Nine Worlds of Norse cosmology.[37]

The eddic poem Völuspá contains a lengthy list of dwarf names that include Gandálfr "Wand-elf", Vindálfr "Wind-elf", and Álfr "Elf".[38] Elsewhere, personages in the Yngling royal house carry names such as Álfr and Gandálfr.

Abode

In the Elder Edda, Álfheimr (literally "elf-world") is mentioned as being given to Frey as a tooth-gift—in Grímnismál. This may mean that Frey was given lordship over the dominion of elves. However, Larrington for example glosses Álfheim merely as the name of a "palace"[39]

For additional concrete description of Álfheimr, Snorri's Prose Edda must be consulted:

- "There is one place there that is called the Elf Home (Álfheimr which is the elven city). People live there that are named the light elves (Ljósálfar). But the dark elves (Dökkálfar) live below in earth, in caves and the dark forest and they are unlike them in appearance – and more unlike them in reality. The Light Elves are brighter than the sun in appearance, but the Dark Elves are blacker than pitch." (Snorri, Gylfaginning 17, Prose Edda)

- "Sá er einn staðr þar, er kallaðr er Álfheimr. Þar byggvir fólk þat, er Ljósálfar heita, en Dökkálfar búa niðri í jörðu, ok eru þeir ólíkir þeim sýnum ok miklu ólíkari reyndum. Ljósálfar eru fegri en sól sýnum, en Dökkálfar eru svartari en bik."[40]

For a description of the more real-life geographical region of Álfheimr, see mentions in the §Sagas, below.

Light-elves and dark-elves

The Icelandic mythographer and historian Snorri Sturluson referred to dwarves (dvergar) as "dark-elves" (dökkálfar) or "black-elves" (svartálfar). He referred to other elves as "light-elves" (ljósálfar), which has often been associated with elves' connection with Freyr, the god of fertility (according to Grímnismál, Poetic Edda). Snorri describes the elf differences.

Snorri in the Prose Edda states that the light elves dwell in Álfheim while the dark elves dwell underground.

Black elves

Confusion arises from the introduction of the additional term svartálfar "black elves", which at first appears synonymous to the "dark elves"; Snorri identifies with the dvergar and has them reside in Svartálfaheim. This prompts Grimm to assume a tripartite division of light elves, dark elves and black elves, of which only the latter are identical with dwarves, while the dark elves are an intermediate class, "not so much downright black, as dim, dingy". In support of such an intermediate class between light elves, or "elves proper", on one hand, and black elves or dwarves on the other, Grimm adduces the evidence of the Scottish brownies and other traditions of dwarves wearing grey or brown clothing.

Kennings

In Skaldic poetry, the álfr word stem is used nearly always in a kenning for a warrior or a full-fledged man[41][42](e.g. Jörmunrekr is periphrased by the kenning sóknar alfr ("álfr of attack").)[43]

Also much discussed is the kenning for the sun, álfroðull, literally "glory of the elves"[44] or "ray or rod of the elves."[45] The kenning is suggestive of the elves' close link to the sun to some,[46] although others have been dismissive of such link, since roðull by itself denotes the sun.[47]

Norse Sagas

The sagas preserve the stories about prominent families, especially in Iceland and Norway during the Viking Era. The stories tend to be naturalistic and realistic, but sometimes mention strange encounters with elves, dwarves, giants, and magic, which convey indigenous folkbelief.

In the Thidrek's Saga a human queen is surprised to learn that the lover who has made her pregnant is an elf and not a man. In the saga of Hrolf Kraki a king named Helgi rapes and impregnates an elf-woman clad in silk who is the most beautiful woman he has ever seen.

Rituals

Men after death could be venerated and sacrificed to, such as the petty king Olaf Geirstad-Elf.

In addition to this, Kormáks saga accounts for how a sacrifice to elves (álfablót) was apparently believed able to heal a severe battle wound:

- Þorvarð healed but slowly; and when he could get on his feet he went to see Þorðís, and asked her what was best to help his healing.

- "A hill there is," answered she, "not far away from here, where elves have their haunt. Now get you the bull that Kormák killed, and redden the outer side of the hill with its blood, and make a feast for the elves with its flesh. Then thou wilt be healed."[48]

Sigvat Thordarson, a missionary for St. Olaf wrote a poem around 1020, the Austrfaravísur ('Eastern-journey verses') describing his journey to the border areas. While in Sweden, being a Christian was refused board in a heathen household, because an álfablót ("elves' sacrifice") was being conducted there.

From the time of year (close to the autumnal equinox) and the elves' association with fertility and the ancestors, it might be assumed that it had to do with the ancestor cult and the life force of the family. The legendary sagas and more fantastical portions of the bibliographical sagas of the kings contain reference to elves. The fays foreign tales also appear as elves in saga adaptations.

Crossbreeding

Several sources suggest that elves and men could procreate.

According to Hrólfs saga kraka, Hrolf Kraki's half-sister Skuld was the half-elven child of King Helgi and an elf-woman (álfkona). Skuld was skilled in witchcraft (seiðr) and could cause fallen warriors, including other elves,[49] to rise again. Accounts of Skuld in earlier sources, however, do not include this material.

The Thidrekssaga version of the Nibelungen (Niflungr) describes Högni as the son of a human queen and an elf, but no such lineage is reported in the Eddas, the Volsunga saga, or the Nibelungenlied.

In the saga of Hrolf Kraki a king named Helgi rapes and impregnates an elf-woman who is the most beautiful woman he has ever seen.

Elf as a kind of spirit

At the beginning of Norna-Gests þáttr, which is a portion of the Greatest Saga of Olaf Tryggvason, the king (Olaf Tryggvasson) sees the presence of something which could have been either an ‘elf’ or an ‘andi’ (spirit) slipping into a locked mansion. The elf, as it turns out, moved to the bed where Norna-Gest was sleeping, and prophesied about him. The elf said the ‘lock is strong’, but the king was not so wise to allow Norna-Gest inside to sleep with them. The elf was referring to the fact the King assumed Norna-Gest was a Christian. Norna-Gest had been christened with oil but was never baptized in water: ‘The elf had spoken so about the lock, because Gest had crossed himself in the evening like other [Christians], even though he was actually heathen.’ The elf exits the king’s room by dematerializing thru the locked door.

Alfr line of kings

Mention of the land of Álfheimr, somewhat conflated with the view of the elven home Álfheimr is found in the Heimskringla and in The Saga of Thorstein, Viking's Son accounts of a line of local kings who ruled over Álfheim, and since they had elven blood they were said to be more beautiful than most men.

- The land governed by King Alf was called Alfheim, and all his offspring are related to the elves. They were fairer than any other people...[50]

Elves in medieval and early modern German texts

The Middle High German alp[52] had the primary sense of "ghostly being" or "specter, spirit".[53][54][55] And already in the Medieval Period, it had developed a narrower sense of "nightmare" (German: Alpdrück),[56] and eventually this became the more prevailing use of the term.[51][31] (See Alp; cf. also mare (in folklore), drude and incubus). Old High German alve meaning "tapeworm" shares proto-Germanic stems *alƀa-z → Old Norse álfr, *alƀi-z → Old English elf.[57]

The Modern German Elf (m) (Elfe (f), Elfen) was introduced as a loan from English in the 1740s.[51][31][c] Jacob Grimm, Deutsches Wörterbuch (1830s), rejected Elfe as a recent Anglicism, and came up with the reconstructed form Elb (m, plural Elbe or Elben), though the form Elbe (f) is attested in Middle High German writings.[60] Jacob Grimm in his Deutsches Wörterbuch deplored the "unhochdeutsch" form Elf, borrowed "unthinkingly" from the English, and Tolkien was inspired by Grimm to recommend reviving the genuinely German form in his Guide to the Names in The Lord of the Rings (1967) and Elb, Elben was consequently reintroduced in the 1972 German translation of The Lord of the Rings.

Although the mythological elf is all but absent in Middle High German texts (except as transformed into the sense of "ghostly beings" etc., cf. §Etymology above),[61] some dwarfs (Middle High German: getwerc) that appear in German heroic poetry have been seen as relating to elves, especially when the dwarf's name is Alberich, construed as "Elf-king".[62][d] Of Alberich, Grimm thinks this name echoes the notion of the king of the nation of elves or dwarfs.[64] The Alberich in the epic Ortnit is a dwarf of childlike-stature who turns out to be the real father of the titular character, having ravished his mother. There is an incubus motif here,[65] that recurs in the Thidrekssaga version of the parentage of Hagen (ON Högni), who was the product of his mother Oda being impregnated by an elf (ON álfr) while she lay in bed.[66]

The Alberich who aids Ortnit is paralleled by the French Auberon, who aids Huon de Bordeaux. Both figures occur in 13th-century works, but commentators typically regard Auberon as the derivative form.[67] Auberon entered English literature through Lord Berner's translation of the chanson de geste around 1540, then as Oberon, the king of elves and fairies in Shakespeare's A Midsummer Night's Dream (see below). In early modern sources, the German alp would be described as "cheating" or "deceiving" (Middle High German: trieben, German: trüben) its victims.[68][69] In particular, Germans of the medieval age ascribed incidents of nightmare to the alp,[56] and the idea stuck so that by the early modern age, the alp became known primarily as a spirit causing nightmares. (Hence the word for "nightmare" in German is Alptraum "elf dream", archaic form Alpdruck "elf pressure.") It was believed that nightmares are a result of an elf sitting on the dreamer's chest (incubi). This aspect of German elf-belief largely corresponds to the Scandinavian belief in the mara.

Old English elven race

Although Old English writings about the ælf as a supernatural race as described in Norse (Eddic) sources are scarce, some scholars have attempted to reconstruct the lost picture of the benevolent elf in Anglo-Saxon culture.[70]

There is a well-known example from Beowulf (Fitt I, vv. 111–14), where elves are included among "misbegotten creatures" condemned by God, and named alongside Germanic giants (ettins) and hell-devils (orcs).[71][72]

Another example is a fragment of the lost Tale of Wade, which begins "Summe sende ylves ..", and translated by Gollancz as: "..[all creatures who fell] became elves or adders or nickors who live in pools; not one became a man except Hildebrand."[73][74][e] Hildebrand mentioned here is an established character from the Cycle of Dietrich von Berne, and this scene may well have involved them as well as Wate's grandson Widia in a den of monsters, as in the Old English Waldere fragment, a speculation that Rickert advanced.[76] More recently, Alaric Hall suggested "some hostile force sent ylues to beset Wade", though cautioning that the remnant was too short to contextualize it with certainty.[77]

Female elf as gloss for nymph

In Old-English there are some eight compound words with the -ælf (female -ælfen) stem, but these are generally considered coined terms used by glossators to conjure Old English names for types of nymphs in Greco-Roman classical literature,[78][79] and the female form -ælfen itself may be a coinage as well.[80][f]

The nymph types glossed are as follows: landælf (Ruricoras Musas[81] or "country muses") dún- ("hill-"; castalides), feld- ("field-"; moides), munt- ("mountain-"; oreades), sæ- ("sea-"; naiades), wæter- ("water-"; nymphae), and wudu- ("wood-nymph"; dryades).[78]

Folklore

Middle ages

- The elf as a spirit playing tricks

In Christianized societies, the elves began to be viewed as spirit that could afflict cattle and people with various conditions, and the mythological notions began to be lost. The loss happened early in Anglo-Saxon England which was an early convert; in Old English, compound as ælfadl "nightmare", ælfsogoða "hiccup", afflictions apparently thought to be caused by elves.

Elf shot

The "elf-shot," recorded since the Anglo-Saxon period refers to a large number of affliction produced in humans and beasts purportedly caused by elves firing shots, .[82] A projectile from an elves or ése (pagan deities) or witches (gif hit wære esa gescot oððe hit wære ylfa gescot oððe hit wære hægtessan gescot) was responsible for sudden pain (such as rheumatism), whose remedy was offered in the Metrical Charm "Against A Sudden Stitch" (Wið færstice) from the late 10th-century medical text Lacnunga. The related Bald's Leechbook from the mid-10th century prescribes for the case "If a horse be ofscoten" the remedy of inscribing Christ's mark on the horse. The operative word ofscoten here, conventionally construed as "elf-shot" has been challenged by A. Hall who proposes "badly pained". Still, the fact remains the medieval formula concludes by saying the cure should be effective should it be the work of elves (Old English: Sy þæt ylfa þe him).[83]

Also, sudden paralysis was sometimes attributed to elf-stroke.

The modern form Elf-shot (or elf-bolt or elf-arrow) from Scotland and Northern England was first attested in a manuscript of about the last quarter of the 16th century, and originally was used in the sense of a 'sharp pain caused by elves'. Later, the word also denoted Neolithic flint arrow-heads, which by the 17th century seem to have been attributed in the region to elvish folk, and which were used in healing rituals, and alleged to be used by witches (and perhaps elves) to injure people and cattle.[84] Compare with the following excerpt from an 1750 ode by Willam Collins:

- There every herd, by sad experience, knows

- How, winged with fate, their elf-shot arrows fly,

- When the sick ewe her summer food forgoes,

- Or, stretched on earth, the heart-smit heifers lie.[85]

Late Middle Ages to Elizabethan era

- Elf as fairy

From around the Late Middle Ages, the word elf began to be used as a term loosely synonymous with fairy and other beings.[g] This mingling is found already in Geoffrey Chaucer's satirical Sir Thopas (1387 or later) where the title character sets out in quest of the "elf-queen", who dwells in the "countree of the Faerie".[86][87] Edmund Spenser in his Faerie Queene (1590-) uses "fairy" and "elf" interchangeably,[88] though his conceptions of the elf must be treated with caution, since they are "imaginary or allegorical characters" that populate his Utopian world,[89] and Spenser's origins of the "Elfe" and "Elfin kynd" as being made and quickened by Prometheus is entirely his invention.[90]

Significant for the distancing of the concept of elves from its mythological origins was the influence from literature. In Elizabethan England, William Shakespeare imagined elves as little people. He apparently considered elves and fairies to be the same race. In his A Midsummer Night's Dream, his elves are almost as small as insects.[dubious – discuss][h] The influence of Shakespeare and Michael Drayton made the use of elf and fairy for very small beings the norm, and had a lasting effect seen in fairy tales about elves collected in the modern period. But not all traditional tales were contaminated by Shakespearean era notions of elves as the wee people, notably the #Ballads such as The Queen of Elfan's Nourice.

Elf-lock

The elf-lock, or a tangle in the hair purportedly caused by the mischief of the elves, can be traced to the Shakespearean period.[91] In a speech in Romeo and Juliet (1592) the "elf-lock" is not caused by an "elf" as such, but Queen Mab who is referred to as "the fairies' midwife", and who travels over people's face unnoticed and matting up their hair.[91][92]

German counterparts of the "elf-lock" are alpzopf, drutenzopf, wichtelzopf, weichelzopf, mahrenlocke, elfklatte, etc. (where alp, drude, mare, and wight are given as the beings responsible). Grimm who compiled the list, also remarked on the similarity to Frau Holle, who entangled people's hair and herself had matted hair.[93]

Ballads

References to the elf, elfland, or people of elfin nature can be found in a number of ballads of English and Scottish origin, surviving mostly in early modern redactions, though often rooted in Medieval tradition.

In a late version of the ballad of Thomas the Rhymer[94] taken down around 1800, Thomas's abductor is called the "queen of fair Elfland",[95] and commentators have taken license to refer to her variously as "elfin queen,"[96] "queen of Faëry,"[97][98] or "Queen of Elphame",[99] etc., though these do not occur in the ballad text itself. And her original identity is more obscure, since in the ancient verse dating perhaps to c. 1400,[100] she is only referred to as "lady gaye" or "quene" in another "cuntre".[101][i]

In Thomas the Rhymer, the Queen of Elfland is portrayed in a positive light. But in additional ballad examples, elves exhibit sinister character, bent on rape and murder, as in the Childe Rowland, or Lady Isabel and the Elf-Knight, in which the Elf-Knight bears away Isabel to murder her. In The Queen of Elfland's Nourice, a woman is abducted to be a wet-nurse to the queen's baby, but promised that she may return home once the child is weaned. In none of these cases is the elf a spritely character with pixie-like qualities.

Scandinavian ballads

Sir Olaf/Oluf and the elf is a ballad type widely disseminated, with seventy Scandinavian ballads (counting variants) according to Child's tally.[102] The common premise is that Olaf on his wedding day is invited to dance by elves, he refuses and as a consequence he lies dead the next day, and his would-be bride dies of grief. The ballad group was later been assigned motif number TSB No. "A 63: Elveskud — Elf maid causes man's sickness and death,"[103] encompassing a number of Scandinavian variants (Danish: Elverskud[104] tr. "Elfin Shaft"[105] or "Sir Oluf and the Elf-king's daughter"[106][107][108] Norwegian: Olaf Liljekrans; Swedish: Elf-Qvinnan och Herr Olof,[109][j] tr. "Sir Olof in Elve-Dance" and "The Elf-Woman and Sir Olof" (two versions);[110] Icelandic: Kvæði af Ólafi Liljurós;[111] Faroese: Ólavur Riddarrós og álvarmoy.[112] The Danish version, as its title suggests, features the "elf-shot" as a means for the Elf-king's daughter robbing the hero of his life.[113][114]

In contrast, the hero survives his elfin encounter in the ballad type represented by the Danish Elvehøj[115] (tr. "Elfer Hill").[116] Type TSB A65. Swedish:Ungersven och Elfvorna,[117][k] tr. "The Young Swain and the Elves"[118]

Modern period

Scandinavian folklore

In Scandinavian folklore, which is a later blend of Norse mythology and elements of Christian mythology, an elf is called elver in Danish, alv in Norwegian, and alv or älva in Swedish (the first is masculine, the second feminine). The Norwegian expressions seldom appear in genuine folklore, and when they do, they are always used synonymous to huldrefolk or vetter, a category of earth-dwelling beings generally held to be more related to Norse dwarves than elves which is comparable to the Icelandic huldufólk (hidden people).

In Denmark and Sweden, the elves appear as beings distinct from the vetter, even though the border between them is diffuse. The insect-winged fairies in British folklore are often called "älvor" in modern Swedish or "alfer" in Danish, although the correct translation is "feer". In a similar vein, the alf found in the fairy tale The Elf of the Rose by Danish author H. C. Andersen is so tiny that he can have a rose blossom for home, and has "wings that reached from his shoulders to his feet". Yet, Andersen also wrote about elvere in The Elfin Hill. The elves in this story are more alike those of traditional Danish folklore, who were beautiful females, living in hills and boulders, capable of dancing a man to death. Like the huldra in Norway and Sweden, they are hollow when seen from the back.

The elves of Norse mythology have survived into folklore mainly as females, living in hills and mounds of stones.[120] The Swedish älvor.[121][122] (sing. älva) were stunningly beautiful girls who lived in the forest with an elven king. They were long-lived and light-hearted in nature. The elves are typically pictured as fair-haired, white-clad, and (like most creatures in the Scandinavian folklore) nasty when offended. In the stories, they often play the role of disease-spirits. The most common, though also most harmless case was various irritating skin rashes, which were called älvablåst (elven blow) and could be cured by a forceful counter-blow (a handy pair of bellows was most useful for this purpose). Skålgropar, a particular kind of petroglyph found in Scandinavia, were known in older times as älvkvarnar (elven mills), pointing to their believed usage. One could appease the elves by offering them a treat (preferably butter) placed into an elven mill – perhaps a custom with roots in the Old Norse álfablót.

In order to protect themselves against malevolent elves, Scandinavians could use a so-called Elf cross (Alfkors, Älvkors or Ellakors), which was carved into buildings or other objects.[119] It existed in two shapes, one was a pentagram and it was still frequently used in early 20th-century Sweden as painted or carved onto doors, walls and household utensils in order to protect against elves.[119] As the name suggests, the elves were perceived as a potential danger against people and livestock.[119] The second form was an ordinary cross carved onto a round or oblong silver plate.[119] This second kind of elf cross one was worn as a pendant in a necklace and in order to have sufficient magic it had to be forged during three evenings with silver from nine different sources of inherited silver.[119] In some locations it also had to be on the altar of a church during three consecutive Sundays.[119]

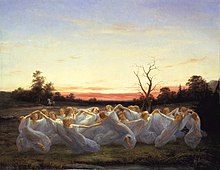

The elves could be seen dancing over meadows, particularly at night and on misty mornings. They left a kind of circle where they had danced, which were called älvdanser (elf dances) or älvringar (elf circles), and to urinate in one was thought to cause venereal diseases. Typically, elf circles were fairy rings consisting of a ring of small mushrooms, but there was also another kind of elf circle:

- On lake shores, where the forest met the lake, you could find elf circles. They were round places where the grass had been flattened like a floor. Elves had danced there. By Lake Tisaren,[123] I have seen one of those. It could be dangerous and one could become ill if one had trodden over such a place or if one destroyed anything there.[120]

If a human watched the dance of the elves, he would discover that even though only a few hours seemed to have passed, many years had passed in the real world. Human being invited or lured to the elf dance is a common motif carried over from older Scandinavian ballads (as seen in the §Ballads section).

Elves were not exclusively young and beautiful. In the Swedish folktale Little Rosa and Long Leda, an elvish woman (älvakvinna) arrives in the end and saves the heroine, Little Rose, on condition that the king's cattle no longer graze on her hill. She is described as a beautiful old woman and by her aspect people saw that she belonged to the subterraneans.[124]

Huldra and huldufólk

In Norwegian folklore are huldra or huldrafolk, which Keightley said were the regional names for elves.[125] In Iceland, expression of belief in the cognate huldufólk or "hidden folk", the elves that dwell in rock formations, is still common. If the natives do not explicitly express their belief, they are often reluctant to express disbelief.[126] A 2006 and 2007 study on superstition by the University of Iceland’s Faculty of Social Sciences supervised by Terry Gunnell (associate folklore professor), reveal that natives would not rule out the existence of elves and ghosts (similar results of a 1974 survey by Professor Erlendur Haraldsson, Fréttabladid reports). Gunnell stated: "Icelanders seem much more open to phenomena like dreaming the future, forebodings, ghosts and elves than other nations." His results were consistent with a similar study conducted in 1974.[127]

German lore

The notion of the alp (and alias mare, drude) that caused nighmares continued into the early modern age. Meanwhile, Shakespearean and later English notions of elves were introduced into Germany, as discussed above under the #German cognates chapter of etymology. Then legends about the "Erl-king", evidently an import from Scandinavia, but often construed as a form of elf, were German Romanticist writers in the 18th century.

Erl-king

An elven king occasionally appears among the predominantly female elves as in Denmark and Sweden. The legend of Der Erlkönig appears to have originated in fairly recent times in Denmark and Goethe based his poem on "Erlkönigs Tochter" ("Erlkönig's Daughter"), a Danish work translated into German by Johann Gottfried Herder.

The Erlkönig's nature has been the subject of some debate. The name translates literally from the German as "Alder King" rather than its common English translation, "Elf King" (which would be rendered as Elfenkönig in German). It has often been suggested that Erlkönig is a mistranslation from the original Danish ellerkonge or elverkonge, which does mean "elf king".

According to German and Danish folklore, the Erlkönig appears as an omen of death, much like the banshee in Irish mythology. Unlike the banshee, however, the Erlkönig will appear only to the person about to die. His form and expression also tell the person what sort of death they will have: a pained expression means a painful death, a peaceful expression means a peaceful death. This aspect of the legend was immortalised by Goethe in his poem Der Erlkönig, later set to music by Schubert.

Elves and the cobbler

In the first story of the Brothers Grimm fairy tale Die Wichtelmänner, the title protagonists are two naked mannequins, which help a shoemaker in his work. When he rewards their work with little clothes, they are so delighted, that they run away and are never seen again. Even though Wichtelmänner are akin to beings such as kobolds, dwarves and brownies, the tale has been translated into English as The Elves and the Shoemaker, and is echoed in J. K. Rowling's Harry Potter stories (see House-elf).

Variations of the German elf in folklore include the moss people[128] and the weisse frauen ("white women"). On the latter Jacob Grimm does not make a direct association to the elves, but other researchers see a possible connection to the shining light elves of Old Norse.[129]

English fairy tales

In the Victorian period stereotype of the elf, appearing in illustrations as tiny men and women with pointed ears and stocking caps. An example is Andrew Lang's fairy tale Princess Nobody (1884), illustrated by Richard Doyle, where fairies are tiny people with butterfly wings, whereas elves are tiny people with red stocking caps.

Christmas elf

In the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, and Ireland the modern children's folklore of Santa Claus typically includes green-clad elves with pointy ears, long noses, and pointy hats as Santa's helpers or hired workers. They make the toys in a workshop located in the North Pole. In this portrayal, elves slightly resemble nimble and delicate versions of the elves in English folktakes in the Victorian period from which they derived. The role of elves as Santa's helpers has continued to be popular, as evidenced by the success of the popular Christmas movie Elf.

Fantasy fiction

The fantasy genre in the 20th century grows out of 19th-century Romanticism. 19th-century scholars such as Andrew Lang and the Grimm brothers collected "fairy-stories" from popular folklore and in some cases retold them freely. A pioneering work of the genre was The King of Elfland's Daughter, a 1924 novel by Lord Dunsany. The Hobbit by J. R. R. Tolkien (1937) is seminal, predating the lecture On Fairy-Stories by the same author by a few years. In the 1939 lecture, Tolkien introduced the term "fantasy" in a sense of "higher form of Art, indeed the most nearly pure form, and so (when achieved) the most potent". Elves played a central role in Tolkien's legendarium, notably The Silmarillion. Tolkien's writing has such popularity that in the 1960s and afterwards, elves speaking an elvish language similar to those in Tolkien's novels (like Quenya, and Sindarin) became staple non-human characters in high fantasy works and in fantasy role-playing games.

Post-Tolkien fantasy elves (popularized by the Dungeons & Dragons role-playing game) tend to be more beautiful and wiser than humans, with sharper senses and perceptions. They are said to be gifted in magic, mentally sharp and lovers of nature, art, and song. They are often skilled archers. A hallmark of many fantasy elves is their pointed ears.

Footnotes

Explanatory notes

- ^ Cf. "A Study of the Old Norse word Regin". Journal of English and Germanic Philology. 15: 251-. 1916.

- ^ Völundr is often regarded as human; he is called the "most skilled of men" in the prose preface to the poem. In German tradition his family is of mermaid lineage: in the Thidrekssaga (aka Vilkina saga), Velundr's father Vadi is given birth by a mermaid (sjákona), and in the German heroic poem Rabenschlacht, his son Witige is rescued by a mermaid kinswoman.

- ^ Although J. R. R. Tolkien attributed the loan of Elf into German to Wieland's 1764 translation of A Midsummer Night's Dream. The same claim was also given in Kluge's dictionary in the 19th century[58][59]

- ^ MHG alp 'elf', rîche "powerful", cf. Goth. reiks 'ruler' can be appropirately interpreted as "ruler of supernatural beings"[63]

- ^ Alternatively translated "Some are elves, some are adders, / and some are nickers that (dwell near water?). /There is no man except Hildebrand alone." by Wentersdorf[75]

- ^ Shippey elsewhere does concede that hypothetically "There may indeed have been a native notion of 'wood-elves' or 'water-elves'..", Shippey, TA (2005). The shadow-walkers: Jacob Grimm's mythology of the monstrous. Brepols. p. 169. ISBN 9782503520940.

- ^ it evolved to a general denotation of various nature spirits like Puck, hobgoblins, Robin Goodfellow, the English and Scots brownie, the Northumbrian English hob and so forth.

- ^ Although Spenser applies elf to full-sized beings in The Faerie Queene.

- ^ Thomas ventures to address her as "qwene of heune" (late ballad:"Queen of Heaven") and she corrects him, saying "I took never so high degree / I am a lady of another country" (late ballad: I am queen of fair Elfland)

- ^ Modern normalized title:Herr Olof och älvorna (Jonsson, Bengt R. (1981). Svenska medeltidsballader.)

- ^ Modern normalized title:Älvefärd (Jonsson, Bengt R. (1981). Svenska medeltidsballader.)

Citations

- ^ Lass 1994, p. 205; Lindow 2002, p. 110; Hall 2007.

- ^ Hall 2007.

- ^ Hall 2007, 96-118.

- ^ Hall 2007, 172-75.

- ^ Hall 2007, 75-76.

- ^ Hall 2007, 32-33.

- ^ Hall 2007, 176-81.

- ^ Hall 2007, 75-88, 157-66.

- ^ Hall 2007, 5

- ^ Hall 2007, 5, 176-77.

- ^ Hall 2007, 54-55.

- ^ a b Kuhn, Adalbert (1855). Die sprachvergleichung und die urgeschichte der indogermanischen völker. Vol. 4.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help), "Zu diesen ṛbhu, alba.. stellt sich nun aber entschieden das ahd. alp, ags. älf, altn . âlfr" - ^ in K. Z., p.110, Schrader, Otto (1890). Prehistoric Antiquities of the Aryan Peoples. Frank Byron Jevons (tr.). Charles Griffin & Company,. p. 163.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link). - ^ Hall 2007, 54-55 fn. 1.

- ^ Paul, Hermann (1900). Grundriss der germanischen philologie unter mitwirkung. K. J. Trübner. p. 268.

- ^ Althof, Hermann, ed. (1902). Das Waltharilied. Dieterich. p. 114.

- ^ Hall 2007, 55-62.

- ^ Hall 2007, 64-66

- ^ Jolly 1996; Shippey 2005.

- ^ e.g. Jolly 1992, p. 172

- ^ Hall 2007, 69-74.

- ^ Hall 2007, 162.

- ^ Hall 2005, 30-32.

- ^ Hall 2007, 23-26; Gunnell 2007, 127-28; Shippey 2005, 180-81.

- ^ Hall 2007, 69-74 on English evidence and 98 fn 10 on German evidence; Haukur Þorgeirsson 2011, 54-58 on Icelandic evidence.

- ^ e.g. Hall 2007, 172-75.

- ^ Shippey 2005, 161-68; Alver and Selberg 1987.

- ^ e.g. Shippey 2005.

- ^ Hall 2007, 75; Shippey 2005, 174, 185-86.

- ^ (Stallybrass tr.) Grimm 1880, vol. 1, p. 25 lists examples citing Saem. (=Rask, Rasmus Kristian; Afzelius, Arvid August, eds. (1818). Edda Saemundar. Stockholm: Typis Elmenianis.), p. 8b (Völuspá 53); p. 71a (Þrymskviða 7)

- ^ a b c d (Stallybrass tr.) Grimm 1883, vol. 2, p. 443 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFGrimm1883 (help)

- ^ Grimm,[31] citing Afzelius 1818, Saem. 83b, i.e., the stanzas in Skírnismál where Skírnir is interrogated whether he is one of the Æsir, Vanir, or elves.

- ^ Larrington 1996, Skirnir's Journey, stanzas 17-18, p.64

- ^ Hall 2004, p. 43. Not finding the elf is underlying argument for Hall saying Vanir and elves may be assimilated.

- ^ "other divine types are mentioned such as the Elves (ON alfar)..but no important or even specifically named gods are found.." Dumézil, Georges (1973). Gods of the Ancient Northmen. University of California Press. p. 3. ISBN 0520020448.

- ^ Hall 2004, pp. 46-

- ^ Hahn, Werner. Saemunds Edda: Lieder germanischer Göttersage. p. 270. points out that the dwarf Alvis's poem only names 6 worlds, but worlds of 11 beings are named by various poems.

- ^ Larrington, Caroline (1996). The Poetic Edda. Oxford University Press. pp. 5–6. has "Staff-elf", "Wind-elf", "Elf"による

- ^ a palace, like Valaskjálf mentioned in the adjacent stanza. See Grimnir's sayings 5.3 (Larrington 1996, p. 52), and "Annotated Index of Names".

- ^ Sturluson, Snorri. The Younger (or Prose) Edda, Rasmus B. Anderson translation (1897). Chapter 7.

- ^ Hall 2004, p. 37. Citing Sveinbjörn Egilsson (1931) [1860]. Lexicon poeticum., entry under "álfr," which reads "hinc in appellationibus virorum poeticis usurpatur sec. Skaldam". The entry gives as an example the kenning álfr lindar, lit. "elf of the linden tree" that siginified a man or warrior (Latin: vir), which is from Sturla Þórðarson's fragment (preserved in the late Laufás-Edda).

- ^ Motz & 1973-74, pp. 98–99

- ^ Ragnarsdrápa 4 (Hall 2004, p. 37)

- ^ Davidson 1943, p. 115

- ^ Motz 1973, p. 95

- ^ Motz 1973, p. 99

- ^ Hall 2004, p. 40

- ^ The Life and Death of Cormac the Skald (Old Norse original: Kormáks saga). Chapter 22.

- ^ Setr Skuld hér til inn mesta seið at vinna Hrólf konung, bróður sinn, svá at í fylgd er með henni álfar ok nornir ok annat ótöluligt illþýði, svá at mannlig náttúra má eigi slíkt standast.[1]

- ^ The Saga of Thorstein, Viking's Son[dead link] (Old Norse original: Þorsteins saga Víkingssonar). Chapter 1.

- ^ a b c Thun, Nils (1969). "The malignant Elves:Notes on Anglo‐Saxon Magic and Germanic Myth". Studia Neophilologica. 41 (2): 378–396. doi:10.1080/00393276908587447. (p.378) "Elves and cognate words in Old Germanic languages are used for supernatural beings of widely different kinds..the corresponding German Alb (Alp), Alf, Olf, in most cases a nightmare, sometimes a spirit of disease or even a devil. (The plural Elben, Elber is not common.) Our knowledge of these creatures is largely derived from folk tales and similar sources., citing M. Hofler, Deutsches Krankhaitsnamenbuch (1899)

- ^ Kuhn,[12] Thun[51] and numerous references.

- ^ Lexer, Matthias von (1872). Mittelhochdeutsches handwörterbuch: bd. A-M. S. Hirzel. p. 28.; online query (German: gespenstisches wesen)

- ^ Schrader, Otto (2003). Primitive Rituals Of The Aryan People. Global Vision Publishing House. p. 13. ISBN 8187746505.

- ^ Kluge, Friedrich (1891). An Etymological Dictionary of the German Language. G. Bell & sons. p. 7.

- ^ a b as illustrated in the 14th-century incantation, the Münchener nachtsegen. Hall 2004, pp. 125, Hall 2007, pp. 125–6

- ^ Mäklelakäinen's suggestion that this sense of "tapeworm" is borrowed from how folk belief envisioned the appearance of an "elf or earth-spirit". (Blažek, Václav (2010). The Indo-european "Smith" (snippet). Institute for the Study Of Man. pp. 5–6.)

- ^ p.99, note 3, in: Tolkien, J.R.R. (2002), A Tolkien Miscellany, SFBC, pp. 97–145, ISBN 0739427369

{{citation}}:|contribution=ignored (help); Missing or empty|title=(help) (orig. pub. Dublin Review 1947) - ^ "Die aufnahme des Wortes knüpft an Wielands Übersetzung von Shakespeares Sommernachtstraum 1764 und and Herders Voklslieder 1774 (Werke 25, 42) an;Kluge, Friedrich (1899). Etymologisches Wörterbuch der deutschen Sprache (6th improved and expanded ed.). Strassbourg: K. J. Trübner. p. 93.

- ^ "With us the word alp still survives in the sense of the night-hag, night-mare, in addition to which our writers of the last century introduced the Engl. elf, a form untrue to our dialect; before that.. the correct pl. elbe or elben. Followed by comparison of elf to aesir gods and dwarfs.[31]

- ^ Croker, Thomas Crofton (1828). of the South of Ireland: The elves in Ireland. The elves in Scotland. On the nature of the elves. The Mabinogion and fairy legends of Wales. J. Murray. p. 56., "The form Alp.. not.. met with in any document previous to the thirteenth century; without doubt, merely because there was no occasion ot make mention of a heathen nothion despised by the learned"; "The middle high German poets sometimes use this expression, though in general very rarely."

- ^ Weston, Jessie Laidlay (1903). "The legends of the Wagner drama: studies in mythology and romance". C. Scribner's sons: 144.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Gillespie, George T. (1973). A Catalog of persons named in German heroic literartue. Clarendon Press. pp. 3–4.

- ^ (Stallybrass tr.) Grimm 1883, Vol. 2, p.453 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFGrimm1883 (help)

- ^ Gillespie 1973, p.3, note3, citing Hempel, Heinrich- (1926). Nibelungenstudien: Nibelungenlied, Thidrikssaga und Balladen (snippet). C. Winters universitätsbuchhandlung. pp. 150-.

- ^ Thidrekksaga. Unger, Carl Rikard (1853). Saga Điðriks konungs af Bern. Feilberg & Landmarks Forlag. p. 172.; Hayme's tr., ch. 169

- ^ Keightley 1850, p. 208, citing Grimm says Auberon derives from Alberich by a usual l→u change.

- ^ (Stallybrass tr.) Grimm 1883, p. 463 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFGrimm1883 (help)

- ^ In Lexer's Middle High German dictionary under alp, alb is an example: Pf. arzb. 2 14b= Pfeiffer 1863, p. 44 (Pfeiffer, F. (1863). "Arzenîbuch 2= Bartholomäus" (Mitte 13. Jh.)". Zwei deutsche Arzneibücher aus dem 12. und 13. Jh. Wien.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)): "Swen der alp triuget, rouchet er sich mit der verbena, ime enwirret als pald niht;" meaning: 'When an alp deceives you, fumigate yourself with verbena and the confusion will soon be gone'. The editor glosses alp here as "malicious, teasing spirit" (German: boshafter neckende geist) - ^ (Hall 2004) These attempts are based on onomastics and phraseology, e.g., the compound ælfsciene ("elf-beautiful"), used of seductively beautiful Biblical women in the Old English poems Judith and Genesis A, is cited as an echo of the Norse description of elves as beings as beautiful as the sun.

- ^ Klaeber, Friedrich (1950). Beowulf and the Finnesburg Fragment (snippet). John R. Clark Hall tr. (3 ed.). Allen & Unwin. p. 5., "þanon untydras ealle onwocon / eotenas ond ylfe ond orcneas / swylce gigantas þa wið gode wunnon / lange þrage he him ðæs lean forgeald"

- ^ Hall 2007, pp. 69–70

- ^ MS. 255 in the Library of Peterhouse, Cambridge. Israel Gollancz read a paper to the Philological Society in 1896, summarized in: Jannaris, A. N. (15 February 1896). "The Tale of Wade". Academy (1241): 137.

- ^ Gollancz, Israel (1906). "Gringolet, Gawain's horse". Saga Book of the Viking Society for Northern Research. 5. London: 108.

- ^ Wentersdrop, Karl P. (1966). "Chaucer and the Lost Tale of Wade". Journal of English and Germanic Philology. 65: 73.

- ^ Rickert, Edith (1904). "The Old English Offa Saga". MP. 2: 73., cited in McConnell, Winder (1978). The Wate Figure in Medieval Tradition. P. Lang. p. 80.

- ^ Hall 2007, p. 104

- ^ a b Shippey 2004, pp. 2–4

- ^ Grimm brothers felt "that these are compounds formed to render the Greek.. and not expressive of a belief in analogous classes of spirits". Keightley 1850, p. 57

- ^ "I have shown that the various compounds combining ælfen with topographical terms are almost certainly ad hoc formations, and that this is probably the case for ælfen itself (§5:3.2)." (Hall 2004, p. 116)

- ^ Cleopatra Glossaries, Wright, Thomas (1873). A second volume of vocabularies. privately printed.

- ^ Singer, British Academy lecture of 1919, ‘Early English Magic and Medicine’ (1919–20, 357) quoted in Hall 2005a, p. 195

- ^ Hall, Alaric (2005a). "Calling the shots: the Old English remedy gif hors ofscoten sie and Anglo-Saxon "elf-shot"" (pdf). Neuphilologische Mitteilungen: Bulletin of the Modern Language Society. 106 (2): 195–209.

- ^ Hall, Alaric (2005b). "Getting Shot of Elves: Healing, Witchcraft and Fairies in the Scottish Witchcraft Trials". Folklore. 116 (1): 19–36. doi:10.1080/0015587052000337699.

- ^ Collins, Willam. 1775. An Ode On The Popular Superstitions Of The Highlands Of Scotland, Considered As The Subject Of Poetry.

- ^ Keightley 1850, p. 53

- ^ Scott 1803, vol.2, p.210

- ^ "The names given by Spenser to those beings are Fayes (Fées), Farys or Fairies, Elfes and Elfins.. " (Keightley 1850, p. 57)

- ^ Scott 1803, vol.2, p.223n

- ^ Keightley 1850, p. 57

- ^ a b "elf-lock", OED Online (2 ed.), Oxford University Press, 1989, retrieved 26 November 2009; "Rom. & Jul. I, iv, 90 Elf-locks" is the oldest example of the use of the phrase given by the OED.

- ^ Mercutio's speech in Romeo and Juliet quoted in: Keightley 1850, pp. 331–2

- ^ (Stallybrass tr.) Grimm 1883, vol. 2, p. 464 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFGrimm1883 (help)

- ^ a b (Child, Francis James (1884), "37. Thomas Rymer", The English and Scottish Popular Ballads, vol. I, Houghton Mifflin, pp. 317-)

- ^ Child's Ballad # 37A, Brown's recited version in Tytler's MS[94]

- ^ Scott 1803, vol.2, p.280, while commenting on the ancient MS. Cotton version

- ^ Scott 1803, vol.2, p.280

- ^ Laing, David; Small, John, eds. (1885), "Thomas off Ersseldoune", Select remains of the ancient popular poetry of Scotland, W. Blackwood and Sons, p. n/a, while commenting on the ancient Thornton MS. version

- ^ "Queen of Elphame, who initiated Thomas the Rimer into her mysteries." Graves, Robert (1955). The crowning privilege: the Clark lectures, 1954-1955. Cassell. p. 196., and in his Watch the north wind rise (1949), p. 170

- ^ "shortly after 1400, or about a hundred years after Thomas's death," (Murray 1875, p. xxiii), but "MS. to be.. older, probably not much later period than the middle of the fourteenth century." (Wright, Thomas; Thoms, William J. (1879). "Thomas and the Elf Queen". The Folk-Lore Record. 2: 165–173.JSTOR 1252468)

- ^ Murray 1875, p. xxiii

- ^ Child, Francis James (1884), "42. Clerk Colvill", The English and Scottish Popular Ballads, vol. I, Houghton Mifflin, p. 374

- ^ Syndergaard 1995; TSB (1978) p.42, 'A63: '

- ^ DgF No. 47; Vol. I, pp. 109-

- ^ Smith-Dampier, E.M. (1920). Danish Ballads. University press. pp. 116–119.

- ^ Jamieson, Robert (1806). Popular ballads and songs (snippet). Edinburgh: Archibald Constable & Co. p. 223.

- ^ Keightley 1850, p. 86n (Keightley notes the Swedish ballad he translated was cognate to Jamieson's Danish ballad)

- ^ These and other available translations by Borrow, Prior, etc., are listed in: Syndergaard 1995, pp. 89–91.

- ^ Geijer, Erik Gustav; Afzelius, Arvid August (1816). Svenska folk-visor. Vol. 3. Häggströ. p. 162.

- ^ Keightley 1850, pp. 82–86)

- ^ Danish Royal Library online (link to PDF)

- ^ CCF #154; Danmarks gamle Folkeviser Vol.4, pp.849-52. Summarized in Child 1884, pp. 374–5 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFChild1884 (help)

- ^ Jamieson 1806, p. 224, "Sir Oluf is here ill handled and elf-shot (elleskudt)"

- ^ Smith-Dampier 1920, pp. 114–115 "To the Elfin Shaft or Elfin Bolt was attributed sudden death or seizure of pain, either in man or beast, among Scandinavians."

- ^ DgF No. 46; Vol. I, pp. 105-

- ^ Jamieson 1806, pp. 225-

- ^ Geijer & Afzelius 1816, 3, pp.170-

- ^ Keightley 1850, pp. 86–7

- ^ a b c d e f g The article Alfkors in Nordisk familjebok (1904).

- ^ a b An account given in 1926, Hellström (1990). En Krönika om Åsbro. p. 36. ISBN 91-7194-726-4.

- ^ For the Swedish belief in älvor see mainly Schön, Ebbe (1986). "De fagra flickorna på ängen". Älvor, vättar och andra väsen. ISBN 91-29-57688-1.

- ^ Cf. Keightely's chapter on Scandinavia: Elves (Keightley 1833, pp. 135-Keightley 1850, pp. 78-, Keightley 1870, pp. 78-)

- ^ "Google Maps". Maps.google.com. 1 January 1970. Retrieved 14 June 2012.

- ^ "Lilla Rosa och Långa Leda". Svenska folksagor. Stockholm: Almquist & Wiksell Förlag AB. 1984. p. 158.

- ^ "The Norwegians call the Elves Huldrafolk, and their music Huldraslaat" (Keightley 1850, p. 79)

- ^ "Novatoadvance.com, Chasing waterfalls ... and elves". Novatoadvance.com. Retrieved 14 June 2012.

- ^ "Icelandreview.com, Iceland Still Believes in Elves and Ghosts". Icelandreview.com. Retrieved 14 June 2012.

- ^ Thistelton-Dyer, T.F. The Folk-lore of Plants, 1889. Available online by Project Gutenberg. File retrieved 3-05-07.

- ^ Grimm, Jacob (1835). Deutsche Mythologie (German Mythology); From English released version Grimm's Teutonic Mythology (1888); Available online by Northvegr 2004-2007, Chapter 32, pages 2,3; Marshall Jones Company (1930). Mythology of All Races Series, Volume 2 Eddic, Great Britain: Marshall Jones Company, 1930, pp. 221-222.

References

- Alver, Bente Gullveig and Torunn Selberg, ‘Folk Medicine as Part of a Larger Concept Complex’, Arv, 43 (1987), 21–44.

- *Coghlan, Ronan (2002). Handbook of Fairies. Milverton: Capall Bann. ISBN 1898307911.

- Grimm, Jacob, Deutsche Mythologie (1835).

- Grimm, Jacob (1883). "XVII. Wights and Elves". Teutonic mythology. Vol. 2. James Steven Stallybrass (tr.). W. Swan Sonnenschein & Allen. pp. 439–517.

- Grimm (1883). Teutonic mythology. Vol. 3. Stallybrass (tr.). pp. 1246ff.

- Grimm (1888). "Supplement". Teutonic mythology. Vol. 4. Stallybrass (tr.). pp. 1407–1435.

- Gunnell, Terry, ‘How Elvish were the Álfar?’, in Constructing Nations, Reconstructing Myth: Essays in Honour of T. A. Shippey, ed. by Andrew Wawn with Graham Johnson and John Walter, Making the Middle Ages, 9 (Turnhout: Brepols, 2007), pp. 111–30.

- Hall, Alaric Timothy Peter (2004), The Meanings of Elf and Elves in Medieval England (PDF) (Ph.D. thesis, University of Glasgow)

- Hall, Alaric, 'Getting Shot of Elves: Healing, Witchcraft and Fairies in the Scottish Witchcraft Trials', Folklore, 116 (2005), 19-36 (http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0015587052000337699), http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/5597.

- Hall, Alaric (2007). Elves in Anglo-saxon England: Matters of Belief, Health, Gender and Identity. Boydell Press. ISBN 1843832941.

- Haukur Þorgeirsson, 'Álfar í gömlum kveðskap', Són, 9 (2011), 49-61, http://hi.is/~haukurth/Haukur_2011_Alfar_Son.pdf.

- Höfler, M., Deutsches Krankheitsnamen-Buch (Munich: Piloty & Loehele, 1899)

- Jolly, Karen Louise (1992), Neusner, Jacob; Frerichs, Ernest S.; Flesher, Paul Virgil McCracken (eds.), Religion, Science, and Magic: In Concert and in Conflict, Oxford University Press, p. 172, ISBN 978-0-19-507911-1 http://books.google.com/books?id=66FpnVdFlBMC&pg=PA172

{{citation}}:|contribution=ignored (help); Missing or empty|title=(help) - Jolly, Karen Louise (1996). Popular Religion in Late Saxon England: Elf Charms in Context. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0807822620.

- Keightley, Thomas (1850) [1828]. The Fairy Mythology. Vol. 1. H. G. Bohn. Vol.2

- 1870 edition at Sacred Texts site

- Lass, Roger (1994). Old English: A Historical Linguistic Companion. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-45848-1.

- Lindow, John (2002). Norse Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Heroes, Rituals, and Beliefs. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-515382-8.

- Marshall Jones Company (1930). Mythology of All Races Series, Volume 2 Eddic, Great Britain: Marshall Jones Company, 1930, 220-221.

- Scott, Walter (1803). Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border. Vol. 2. James Ballantyne.

- Shippey, TA (2004). "Light-elves, Dark-elves, and Others: Tolkien's Elvish Problem". Tolkien Studies volume=1: 1–15. doi:10.1353/tks.2004.0015.

{{cite journal}}: Missing pipe in:|journal=(help) - Shippey, Tom, ‘Alias oves habeo: The Elves as a Category Problem’, in The Shadow-Walkers: Jacob Grimm’s Mythology of the Monstrous, ed. by Tom Shippey, Medieval and Renaissance Texts and Studies, 291/Arizona Studies in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, 14 (Tempe, AZ: Arizon Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, 2005), pp. 157–87.

- Syndergaard, Larry E. (1995). English Translations of the Scandinavian Medieval Ballads: An Analytical Guide and Bibliography. Nordic Institute of Folklore. ISBN 9529724160.

External links

- Wikisource:Prose Edda/Gylfaginning (The Fooling Of Gylfe) by Sturluson, Snorri, 13th century, Edda, in English. Accessed 16 April 2007

- Anderson, H. C.. 1842. The Elf of the Rose (Danish original: Rosen-Alfen).

- Anderson, H. C. 1845. The Elfin Hill (Danish original: Elverhøi).