Air France Flight 447: Difference between revisions

Reverted good faith edits by Michael Frind (talk): Please see talkpage about this "minor" clarification. Thank you. (TW★TW) |

Improved clarity |

||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

| caption = F-GZCP, the aircraft involved in the incident, at [[Paris-Charles de Gaulle Airport|Charles de Gaulle Airport]] in 2007 |

| caption = F-GZCP, the aircraft involved in the incident, at [[Paris-Charles de Gaulle Airport|Charles de Gaulle Airport]] in 2007 |

||

| Date = 1 June 2009 |

| Date = 1 June 2009 |

||

| Type = Incorrect speed readings likely caused by obstruction of the [[pitot tube]]s by ice crystals, followed by inappropriate control inputs that destabilized the flight path<ref name="Final">{{cite web |title=Final report on the accident on 1st June 2009 to the Airbus A330-203 registered F-GZCP operated by Air France flight AF 447 Rio de Janeiro – Paris |url=http://www.bea.aero/docspa/2009/f-cp090601.en/pdf/f-cp090601.en.pdf |publisher=[[Bureau d'Enquêtes et d'Analyses pour la Sécurité de l'Aviation Civile|BEA]] |date=July 2012|format=English edition |page=202}}</ref> |

| Type = Incorrect speed readings likely caused by obstruction of the [[pitot tube]]s by ice crystals, followed by inappropriate control inputs (pilot error) that destabilized the flight path<ref name="Final">{{cite web |title=Final report on the accident on 1st June 2009 to the Airbus A330-203 registered F-GZCP operated by Air France flight AF 447 Rio de Janeiro – Paris |url=http://www.bea.aero/docspa/2009/f-cp090601.en/pdf/f-cp090601.en.pdf |publisher=[[Bureau d'Enquêtes et d'Analyses pour la Sécurité de l'Aviation Civile|BEA]] |date=July 2012|format=English edition |page=202}}</ref> |

||

| Site = {{nowrap|Near [[Waypoint#Waypoints and aviation|waypoint]] TASIL, Atlantic Ocean<ref name="07-02-2009 BEA Report"/>}} |

| Site = {{nowrap|Near [[Waypoint#Waypoints and aviation|waypoint]] TASIL, Atlantic Ocean<ref name="07-02-2009 BEA Report"/>}} |

||

| Coordinates = {{coord|3|03|57|N|30|33|42|W|type:event|display=inline,title}} |

| Coordinates = {{coord|3|03|57|N|30|33|42|W|type:event|display=inline,title}} |

||

Revision as of 23:38, 21 January 2013

F-GZCP, the aircraft involved in the incident, at Charles de Gaulle Airport in 2007 | |

| Accident | |

|---|---|

| Date | 1 June 2009 |

| Summary | Incorrect speed readings likely caused by obstruction of the pitot tubes by ice crystals, followed by inappropriate control inputs (pilot error) that destabilized the flight path[1] |

| Site | Near waypoint TASIL, Atlantic Ocean[2] 3°03′57″N 30°33′42″W / 3.06583°N 30.56167°W |

| Aircraft type | Airbus A330-203 |

| Operator | Air France |

| Registration | F-GZCP[3] |

| Flight origin | Rio de Janeiro-Galeão Int'l Airport |

| Destination | Paris-Charles de Gaulle Airport |

| Passengers | 216[3] |

| Crew | 12[3] |

| Fatalities | 228[2] (all) |

| Survivors | 0 |

Air France Flight 447 (abbreviated AF447) was a scheduled commercial flight from Galeão International Airport in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil to Charles de Gaulle International Airport in Paris, France. On 1 June 2009, the Airbus A330-200 airliner serving the flight crashed into the Atlantic Ocean, killing all 216 passengers and 12 aircrew.[4] The accident was the deadliest in the history of Air France,[5][6] and has been described as the worst accident in both French and Brazilian aviation history.[citation needed] It was the second fatal accident involving an Airbus A330, the first while in commercial passenger service and, to date, the accident with the highest death toll of any involving the aircraft type anywhere in the world.

The aircraft crashed following an aerodynamic stall caused by inconsistent airspeed sensor readings, the disengagement of the autopilot, and the pilot making nose-up inputs despite stall warnings, causing a fatal loss of airspeed and a sharp descent. The pilots had not received specific training in "manual airplane handling of approach to stall and stall recovery at high altitude"; this was not a standard training requirement at the time of the accident.[7][1][8]

The reason for the faulty airspeed readings is unknown, but it is assumed by the accident investigators to have been caused by the formation of ice inside the pitot tubes, thereby depriving them of forward-facing air pressure.[9][10][11] Pitot tube blockage has contributed to airliner crashes in the past – such as Northwest Airlines Flight 6231 in 1974 and Birgenair Flight 301 in 1996.[12]

The investigation into the accident, which continued for three years after the disaster, was initially hampered by the lack of eyewitness evidence and radar tracks, as well as by difficulty in finding the aircraft's black boxes, which were finally located and recovered from the ocean floor in May 2011, nearly two years after the accident.[2][13] The final report was released at a news conference on 5 July 2012.[14][15] It states that the accident resulted from a succession of events: temporary inconsistency between the airspeed measurements, probably following obstruction of the pitot tubes by ice crystals, that caused the autopilot to disconnect; inappropriate control inputs that destabilized the flight path and led to a stall; and pilot misunderstanding of the situation leading to a lack of control inputs that would have made it possible to recover from it.[1]

Aircraft

The aircraft involved in the accident was an Airbus A330-203, with manufacturer serial number 660, registered as F-GZCP. This airliner first flew on 25 February 2005.[16][17] The aircraft was powered by two General Electric CF6-80E1 engines with a maximum thrust of 72,000 lb giving it a cruise speed range of Mach 0.82–0.86 (871–913 km/h, 470–493 KTAS, 540 – 566 mph), at 35,000 ft (10.7 km altitude) and a range of 12,500 km (6750 nmi).[16] On 17 August 2006, the A330 was involved in a ground collision with Airbus A321-211 F-GTAM, at Charles de Gaulle Airport, Paris. F-GTAM was substantially damaged while F-GZCP suffered only minor damage.[18] The aircraft underwent a major overhaul on 16 April 2009,[19] and at the time of the accident had accumulated 18,870 flying hours.[16][19] The aircraft made 24 flights from Paris, to and from 13 different destinations worldwide, between 5 and 31 May 2009.[citation needed]

Accident

Template:Air France Flight 447/flight path

The aircraft departed from Rio de Janeiro-Galeão International Airport on 31 May 2009 at 19:03 local time (22:03 UTC), with a scheduled arrival at Paris-Charles de Gaulle Airport approximately 11 hours later.[2] The last verbal contact with the aircraft was at 01:35 UTC, when it reported that it had passed waypoint INTOL (1°21′39″S 32°49′53″W / 1.36083°S 32.83139°W), located 565 km (351 mi) off Natal, on Brazil's north-eastern coast.[2] The aircraft left Brazil Atlantic radar surveillance at 01:48 UTC.[citation needed]

The Airbus 330 is designed to be flown by a crew of two pilots. But because the thirteen hours "duty time" (flight duration, plus pre-flight preparation) for the Rio - Paris route exceeds the maximum ten hours permitted by Air France's procedures, flight 447 was crewed by three pilots, a captain and two co-pilots.[20] With three pilots on board, each of them can take a rest during the flight, and for this purpose the A330 has a rest cabin, situated just behind the cockpit.[21]

In accordance with common practice, the captain had sent one of the co-pilots for the first rest period with the intention of taking the second break himself.[22] At 01:55 UTC, he woke the second pilot and said: "... he's going to take my place". After having attended the briefing between the two co-pilots, the captain left the cockpit to rest at 02:01:46 UTC. At 02:06 UTC, the pilot warned the cabin crew that they were about to enter an area of turbulence. Two minutes later, the pilots turned the aircraft slightly to the left and decreased its speed from Mach 0.82 to Mach 0.8 because of the increased turbulence.

At 02:10:05 UTC the autopilot disengaged as did the engines' auto-thrust systems three seconds later. The aircraft started to roll to the right due to turbulence, and the pilot corrected this by deflecting his side-stick to the left. At the same time he made an abrupt nose-up input on the side-stick, an action that was unnecessary and excessive under the circumstances.[23] The aircraft's stall warning sounded briefly twice due to the angle of attack tolerance being exceeded. Ten seconds later, the aircraft's recorded airspeed dropped sharply from 275 knots to 60 knots. The aircraft's angle of attack increased, and the aircraft started to climb. The left-side instruments then recorded a sharp rise in airspeed to 215 knots. This change was not displayed by the Integrated Standby Instrument System (ISIS) until a minute later (the right-side instruments are not recorded by the recorder). The pilot continued making nose-up inputs. The trimmable horizontal stabilizer (THS) moved from three to thirteen degrees nose-up in about one minute, and remained in that latter position until the end of the flight.

At around 02:11 UTC, the aircraft had climbed to its maximum altitude of around 38,000 feet. There, its angle of attack was 16 degrees, and the thrust levers were in the TO/GA detent (fully forward), and at 02:11:15 UTC the pitch attitude was slightly over 16 degrees and falling, but the angle of attack rapidly increased towards 30 degrees. The wings lost lift and the aircraft stalled.[24] At 02:11:40 UTC, the captain re-entered the cockpit. The angle of attack had then reached 40 degrees, and the aircraft had descended to 35,000 feet with the engines running at almost 100% N1 (the rotational speed of the front intake fan, which delivers most of a turbofan engine's thrust). The stall warnings stopped, as all airspeed indications were now considered invalid by the aircraft's computer due to the high angle of attack and/or the airspeed was less than 60 knots. In other words, the aircraft was oriented nose-up but descending steeply.

Roughly 20 seconds later, at 02:12 UTC, the pilot decreased the aircraft's pitch slightly, air speed indications became valid and the stall warning sounded again and sounded intermittently for the remaining duration of the flight, but stopped when the pilot increased the aircraft's nose-up pitch. From there until the end of the flight, the angle of attack never dropped below 35 degrees. From the time the aircraft stalled until it impacted with the ocean, the engines were primarily developing either N1 100% or TOGA thrust, though they were briefly spooled down to about N1 50% on two occasions. The engines always responded to commands and were developing in excess of N1 100% when the flight ended.

The flight data recordings stopped at 02:14:28 UTC, or 3 hours 45 minutes after takeoff. At that point, the aircraft's ground speed was 107 knots, and it was descending at 10,912 feet per minute. Its pitch was 16.2 degrees (nose up), with a roll angle of 5.3 degrees left. During its descent, the aircraft had turned more than 180 degrees to the right to a compass heading of 270 degrees. The aircraft remained stalled during its entire 3 minute 30 second descent from 38,000 feet[11] before it hit the ocean surface at a speed of 151 knots (280 km/h) , comprising vertical and horizontal components of both 107 knots. The aircraft broke up on impact, killing everyone on board.[25]

Automated messages

An Air France spokesperson stated on 3 June that "the aircraft sent a series of electronic messages over a three-minute period, which represented about a minute of information. "[26][27][Note 1] These messages, sent from an onboard monitoring system via the Aircraft Communication Addressing and Reporting System (ACARS), were made public on 4 June 2009.[28] The transcripts indicate that between 02:10 UTC and 02:14 UTC, 6 failure reports (FLR) and 19 warnings (WRN) were transmitted.[29] The messages resulted from equipment failure data, captured by a built-in system for testing and reporting, and cockpit warnings also posted to ACARS.[30] The failures and warnings in the 4 minutes of transmission concerned navigation, auto-flight, flight controls and cabin air-conditioning (codes beginning with 34, 22, 27 and 21, respectively).[31]

Among the ACARS transmissions in the first minute is one message that indicates a fault in the pitot-static system (code 34111506).[28][31] Bruno Sinatti, president of Alter, Air France's third-biggest pilots' union, stated that "Piloting becomes very difficult, near impossible, without reliable speed data".[32] The twelve warning messages with the same time code indicate that the autopilot and auto-thrust system had disengaged, that the TCAS was in fault mode, and flight mode went from 'normal law' to 'alternate law'.[33][34] The 02:10 transmission contained a set of coordinates which indicated that the aircraft was at 2°59′N 30°35′W / 2.98°N 30.59°W.[Note 2]

The remainder of the messages occurred from 02:11 UTC to 02:14 UTC, containing a fault message for an Air Data Inertial Reference Unit (ADIRU) and the Integrated Standby Instrument System (ISIS).[34][35] At 02:12 UTC, a warning message NAV ADR DISAGREE indicated that there was a disagreement between the three independent air data systems.[Note 3] At 02:13 UTC, a fault message for the flight management guidance and envelope computer was sent.[36] One of the two final messages transmitted at 02:14 UTC was a warning referring to the air data reference system, the other ADVISORY (Code 213100206) was a "cabin vertical speed warning", indicating that the aircraft was descending at a high rate.[37][38][39]

Weather conditions

Weather conditions in the mid-Atlantic were normal for the time of year, and included a broad band of thunderstorms along the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ).[40] A meteorological analysis of the area surrounding the flight path showed a mesoscale convective system extending to an altitude of around 50,000 feet (15,000 m) above the Atlantic Ocean before Flight 447 disappeared.[41][42][43][44] During its final hour, flight 447 encountered areas of light turbulence.[45]

Commercial air transport crews routinely encounter this type of storm in this area.[46] With the aircraft under the control of its automated systems, one of the main tasks occupying the cockpit crew was that of monitoring the progress of the flight through the ITCZ, using the on-board weather radar to avoid areas of significant turbulence.[47] Twelve other flights shared more or less the same route that Flight 447 was using at the time of the accident.[48][49]

Search and recovery

Surface search

Flight 447 was due to pass from Brazilian airspace into Senegalese airspace at approximately 02:20 (UTC), and then into Cape Verde airspace at approximately 03:45. Shortly after 04:00, when the flight had failed to contact air traffic control in either Senegal or Cape Verde, the controller in Senegal attempted to contact the aircraft. When he received no response, he asked the crew of another Air France flight (AF459) to try to contact AF447; this also met with no success.[50]

After further attempts to contact flight 447 were unsuccessful, an aerial search for the missing Airbus commenced from both sides of the Atlantic. Brazilian Air Force aircraft from the archipelago of Fernando de Noronha and French reconnaissance aircraft based in Dakar, Senegal led the search.[51] They were assisted by aircraft from Spain[52] and the United States.[53]

By early afternoon on 1 June, officials with Air France and the French government had already presumed that the aircraft had been lost with no survivors. An Air France spokesperson told L'Express that there was "no hope for survivors,"[54][55][56] and French President Nicolas Sarkozy told relatives of the passengers that there was only a minimal chance that anyone survived.[57]

On 2 June at 15:20 (UTC), a Brazilian Air Force Embraer R-99A spotted wreckage and signs of oil, possibly jet fuel, strewn along a 5 km (3 mi) band 650 km (400 mi) north-east of Fernando de Noronha Island, near the Saint Peter and Saint Paul Archipelago. The sighted wreckage included an aircraft seat, an orange buoy, a barrel, and "white pieces and electrical conductors".[58][59] Later that day, after meeting with relatives of the Brazilians on the aircraft, Brazilian Defence Minister Nelson Jobim announced that the Air Force believed the wreckage was from Flight 447.[60][61] Brazilian vice-president José Alencar (acting as president since Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva was out of the country) declared three days of official mourning.[61][62]

Also on 2 June, two French Navy vessels, the frigate Ventôse and helicopter-carrier Mistral, were en route to the suspected crash site. Other ships sent to the site included the French research vessel Pourquoi Pas?, equipped with two mini-submarines able to descend to 6,000 m (20,000 ft),[63][64] since the area of the Atlantic in which the aircraft went down may be as deep as 4,700 m (15,400 ft).[65][66] A U.S. Navy Lockheed Martin P-3 Orion anti-submarine warfare and maritime patrol aircraft was deployed in the search.[67]

On 3 June, the first Brazilian Navy ship, the patrol boat Grajaú, reached the area in which the first debris was spotted. The Brazilian Navy sent a total of five ships to the debris site; the frigate Constituição and the corvette Caboclo were scheduled to reach the area on 4 June, the frigate Bosísio on 6 June and the replenishment oiler Almirante Gastão Motta on 7 June.[68][69]

On 5 June 2009, the nuclear submarine Émeraude was dispatched to the crash zone, arriving in the area on the 10th. Its mission was to assist in the search for the missing flight recorders or "black-boxes" which might be located at great depth.[70] The submarine would use its sonar to listen for the ultrasonic signal emitted by the black boxes' "pingers",[71] covering 13 sq mi (34 km2) a day. The Émeraude was to work with the mini-sub Nautile, which can descend to the ocean floor. The French submarines would be aided by two U.S. underwater audio devices capable of picking up signals at a depth of 20,000 ft (6,100 m).[72]

On 4 June 2009, the Brazilian Air Force claimed they had recovered the first debris from the Air France crash site, 340 miles (550 km) northeast of the Fernando de Noronha archipelago,[73] but on 5 June, around 13:00 UTC, Brazilian officials announced that they had not yet recovered anything from Flight 447, as the oil slick and debris field found on 2 June could not have come from the aircraft.[citation needed] Ramon Borges Cardoso, director of the Air Space Control Department, said that the fuel slicks were not caused by aviation fuel but were believed to have been from a passing ship.[74] Even so, a Brazilian Air Force official maintained that some of the material that had been spotted (but not picked up) was in fact from Flight 447.[citation needed] Poor visibility had prevented search teams from re-locating the material.[75]

On 6 June 2009, five days after Flight 447 disappeared, it was reported that the Brazilian Air Force had located "bodies and debris" from the missing aircraft, after they had been spotted by a special search radar-equipped aircraft near the Saint Peter and Saint Paul Archipelago.[citation needed] The bodies and objects were reportedly found at 08:14 Brazilian time (11:14 UTC), and experts on human remains were sent to investigate. Brazilian Air Force Colonel Jorge Amaral stated that "We confirm the recovery from the water of debris and bodies from the Air France aircraft. Air France boarding passes for Flight 447 were also found. We can't give more information without confirming what we have."[76] Two male bodies were later found along with a seat, a nylon backpack containing a computer and vaccination card and a leather briefcase containing a boarding pass for the Air France flight.[77]

Authorities also corrected the misunderstanding about the earlier debris findings: except for the wooden pallet, the debris did come from Flight 447, but rescue aircraft and ships had made the search for possible survivors and bodies a priority, delaying the verification of the origins of the other recovered debris.[78]

On 7 June, search crews recovered the Airbus's vertical stabilizer, the first major piece of wreckage to be discovered.[2][79]

By 17 June 2009, a total of 50 bodies had been recovered in two distinct groups more than 50 miles (80 km) apart,[80][81] and more than 400 pieces of debris from the aircraft had been recovered.[82] 49 of the 50 bodies had been transported to shore, first by the frigates Constituição and Bosísio to the islands of Fernando de Noronha and thereafter by air to Recife for identification.[81][83][84][85] As of 23 June 2009, officials had identified 11 of the 50 bodies recovered from the crash site off the coast of Brazil, by using dental records and fingerprints. Of those identified, ten were Brazilian, although no names had been released.[86] On 25 June, Le Figaro reported that the bodies of the pilot, Marc Dubois, and a flight attendant had been retrieved and identified.[87] On 26 June, the Brazilian Military announced it had ended the search for bodies and debris, having recovered 50[88] bodies with the help of French vessels and French, Spanish and U.S. aircraft.

Underwater search

Following the end of the search for bodies, the search continued for the flight data recorder and the cockpit voice recorder, the so-called "black boxes". BEA chief Paul-Louis Arslanian said that he was not optimistic about finding them since they might be under as much as 3,000 m (9,800 ft) of water and the terrain under this portion of the ocean was very rugged.[89] Investigators were hoping to find the aircraft's lower aft section, since that was where the recorders were located.[90] Although France had never recovered a flight recorder from such depths,[89] there was precedent for such an operation: in 1988, an independent contractor was able to recover the cockpit voice recorder of South African Airways Flight 295 from a depth of 4,900 m (16,100 ft) in a search area of between 80 and 250 square nautical miles (270 and 860 km2).[91][92] The Air France flight recorders were fitted with water-activated acoustic underwater locator beacons or "pingers", which should have remained active for at least 30 days, giving searchers that much time to locate the origin of the signals.[93]

France requested two "towed pinger locator hydrophones" from the United States Navy to help find the aircraft.[63] The French nuclear submarine and two French-contracted ships (the Fairmount Expedition and the Fairmount Glacier, towing the U.S. Navy listening devices) trawled a search area with a radius of 80 kilometres (50 mi), centred on the airplane's last known position.[94][95] By mid July, recovery of the black boxes had still not been announced. French search teams denied an earlier report that a "very weak" signal had been picked up from the black box locator beacon. The finite beacon battery life meant that, as the time since the crash elapsed, the likelihood of location diminished.[96] In late July, the search for the black boxes entered its second phase, with a French research vessel resuming the search using a towed sonar array.[97] Airbus demonstrated its commitment to finding the root cause of the accident by agreeing to help fund the extended search.[98] The second phase of the search ended on 20 August without finding wreckage within a 75 km radius of the last position, as reported at 02:10.[99]

On 13 December 2009, the BEA announced that a search for the recorders for three months more would be conducted using "robot submarines" beginning in February 2010.[100] The BEA announced that they expected the search to resume in mid-March, depending on the weather. The third phase of the search was planned to take four weeks. Air France, Airbus, the U.S. Navy and the U.S. National Transportation Safety Board were to aid in the search.[101] The new search plan covered an area of 770 square miles (2,000 km2) and was to utilize four sonar devices and two underwater robots.[102] Oceanographers from France, Russia, Britain, and the United States each separately analysed the search area, to select a smaller area for closer survey.[103][104]

The third phase of the search lasted from 2 April until 24 May 2010.[105][106][107]

On 6 May 2010, the French Minister of Defense reported[108] that the cockpit voice recorders had been localized to a zone 5 km by 5 km, following analysis of the data recorded by the French submarine during the initial search conducted in mid-2009. On 12 May 2010, it was reported[109] that the search following the 6 May report of the possible location of the voice recorders had not led to any findings and that the search had resumed in a different area from the one identified by the French submarine. The third phase of the search ended on 24 May 2010 without any success, though the French Bureau d'Enquetes et d'Analyses (BEA) says that the search 'nearly' covered the whole area drawn up by investigators.

In November 2010, French officials announced that a fourth search would start in February 2011, using the best equipment available.[110]

2011 search and recovery

In July 2010, the US-based search consultancy Metron had been engaged to draw up a probability map of where to focus the search, based on prior probabilities from flight data and local condition reports, combined with the results from the previous searches. The Metron team used what it described as "classic" Bayesian search methods, an approach that had previously been successful in the search for the submarine USS Scorpion. Phase 4 of the search operation started in the area identified by the Metron study as being the most likely resting place of flight 447.[111]

Within a week of resuming of the search operation, on 3 April 2011, a team led by the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution operating full ocean depth autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) owned by the Waitt Institute discovered, by means of sidescan sonar, a large portion of debris field from flight AF447.[111] Further debris and bodies, still trapped in the partly intact remains of the aircraft's fuselage, were located in water depths of between 3,800 to 4,000 metres (2,100 to 2,200 fathoms; 12,500 to 13,100 ft). The debris was found to be lying in a relatively flat and silty area of the ocean floor (as opposed to the extremely mountainous topography that was originally believed to be AF447's final resting place).[citation needed] Other items found were engines, wing parts and the landing gear.[112]

The debris field was described as "quite compact", measuring some 200 by 600 metres (660 by 1,970 ft) and located a short distance to the north of where pieces of wreckage had been recovered previously, suggesting that the aircraft hit the water largely intact.[113] The French Ecology and Transportation Minister Nathalie Kosciusko-Morizet stated the bodies and wreckage would be brought to the surface and taken to France for examination and identification.[114] The French government chartered the Île de Sein to recover the flight recorders from the wreckage.[115][116] An American Remora 6000 remotely operated vehicle (ROV) and operations crew experienced in the recovery of aircraft for the United States Navy were on board the Île de Sein.[117][118][119]

Île de Sein arrived at the crash site on 26 April and, during its first dive, the Remora 6000 found the flight data recorder chassis, although without the crash-survivable memory unit.[120][121] On 1 May the memory unit was found and lifted on board the Île de Sein by the ROV.[122] The aircraft's cockpit voice recorder was found late on 2 May 2011, and was raised and brought on board the Île de Sein the following day.[123]

On 7 May the flight recorders, under judicial seal, were taken aboard the French Navy patrol boat La Capricieuse for transfer to the port of Cayenne. From there they were transported by air to the BEA's office in Le Bourget near Paris for data download and analysis. One engine and the avionics bay, containing onboard computers, had also been raised.[124]

By 16 May all the data from both the flight data recorder and the cockpit voice recorder had been downloaded.[125] The data were subjected to detailed in-depth analysis over the next several weeks, and the findings published in the third interim report at the end of July.[126] The download was completed in the presence of two Brazilian investigators of the Aeronautical Accidents Investigation and Prevention Center (CENIPA), two British investigators of the Air Accidents Investigation Branch (AAIB), two German investigators of the German Federal Bureau of Aircraft Accidents Investigation (BFU), one American investigator of the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB), an officer of the French judicial police, and a court expert. The entire download was filmed and recorded.[126]

Between 5 May and 3 June 2011, 104 bodies were recovered from the wreckage, bringing the total number of bodies found to 154. 50 bodies had been previously recovered from the sea.[88][127][128][129] The remaining 74 bodies from the flight have not been found.[130]

Investigation

The French authorities opened two investigations:

- A criminal investigation for manslaughter began 5 June 2009, under the supervision of Investigating Magistrate Sylvie Zimmerman from the Paris Tribunal de Grande Instance. This is standard procedure for any accident involving a loss of life and implies no presumption of foul play.[131] The judge gave the investigation to the Gendarmerie nationale, which would conduct it through its aerial transportation division (Gendarmerie des transports aériens or GTA) and its forensic research institute (the "Institut de Recherche Criminelle de la Gendarmerie Nationale", FR).[132]

- In March 2011, a French judge filed preliminary manslaughter charges against Air France and Airbus over the crash.[134]

- A technical investigation, the goal of which is to enhance the safety of future flights. As the aircraft was of French registration and crashed over international waters, this is the responsibility of the French government, under the ICAO convention. The Bureau d'Enquêtes et d'Analyses pour la Sécurité de l'Aviation Civile (BEA) is in charge of the investigation.[135] Representatives from Brazil, Germany, the United Kingdom, and the United States became involved under the provisions of ICAO Annex 13; representatives of the United States were involved since the engines of the aircraft were manufactured there, and the other representatives could supply important information. The People's Republic of China, Croatia, Hungary, Republic of Ireland, Italy, Lebanon, Morocco, Norway, South Korea, Russia, South Africa, and Switzerland appointed observers, since citizens of those countries were on board.[136] The BEA issued a press release on 5 June 2009, that stated: [137]

A large quantity of more or less accurate information and attempts at explanations concerning the accident are currently being circulated. The BEA reminds those concerned that in such circumstances, it is advisable to avoid all hasty interpretations and speculation on the basis of partial or non-validated information.

At this stage of the investigation, the only established facts are:

- the presence near the airplane's planned route over the Atlantic of significant convective cells typical of the equatorial regions;

- based on the analysis of the automatic messages broadcast by the plane, there are inconsistencies between the various speeds measured.

On 2 July 2009, the BEA released an intermediate report, which described all known facts, and a summary of the visual examination of the rudder and the other parts of the aircraft that had been recovered at that time.[2] According to the BEA, this examination showed that:

- the airliner was likely to have struck the surface of the sea in a normal flight attitude, with a high rate of descent;[Note 5][2][138]

- There were no signs of any fires or explosions.

- The airliner did not break up in flight. The report also stresses that the BEA had not had access to the post-mortem reports at the time of its writing. Some of these might have suggested otherwise.[2][139]

In May 2010 the French newspaper Le Figaro suggested that the aircraft had been heading back to Brazil when it had crashed.[140]

On 16 May 2011, Le Figaro reported that the BEA investigators had ruled out an aircraft malfunction as the cause of the crash, according to preliminary information extracted from the Flight Data Recorder.[141] The following day, the BEA issued a press release explicitly describing the Le Figaro report as a "sensationalist publication of non-validated information". They stated that no conclusions had yet been made, that investigations were continuing, and that no interim report was expected before the summer.[142] On 18 May the head of the investigation clarified this contradictory information, stating that no major malfunction of the aircraft had been found so far in the data from the flight data recorder, but that minor malfunctions had not yet been ruled out.[143]

On 27 May 2011, the BEA released a short factual report of the findings from the data recorders without any conclusions.

Airspeed inconsistency

In the minutes before its disappearance, the aircraft's onboard systems had sent a number of messages, via ACARS, indicating disagreement in the indicated airspeed (IAS) readings. A spokesperson for the BEA claimed that "the air speed of the aircraft was unclear" to the pilots[70] and, on 4 June, Airbus issued an Accident Information Telex to operators of all its aircraft reminding pilots of the recommended Abnormal and Emergency Procedures to be taken in the case of unreliable airspeed indication.[144] French Transport Minister Dominique Bussreau said "Obviously the pilots [of Flight 447] did not have the [correct] speed showing, which can lead to two bad consequences for the life of the aircraft: under-speed, which can lead to a stall, and over-speed, which can lead to the aircraft breaking up because it is approaching the speed of sound and the structure of the plane is not made for resisting such speeds".[145]

Paul-Louis Arslanian, of France's air accident investigation agency, confirmed that there had been previous problems affecting the speed readings on other A330 aircraft stating, "We have seen a certain number of these types of faults on the A330 ... There is a programme of replacement, of improvement".[146] The problems primarily occurred on the Airbus A320, but, awaiting a recommendation from Airbus, Air France delayed installing new pitots on A330/A340, yet increased inspection frequencies.[147]

On 6 June 2009, Arslanian said that Air France had not replaced pitot probes as Airbus recommended on F-GZCP, saying that "it does not mean that without replacing the probes that the A330 was dangerous."[147] Air France issued a further clarification of the situation:

Malfunctions in the pitot probes on the A320 led the manufacturer to issue a recommendation in September 2007 to change the probes. This recommendation also applies to long-haul aircraft using the same probes and on which a very few incidents of a similar nature had occurred.

— [148]

When it was introduced in 1994, the Airbus 330 had been equipped with pitot tubes, part number 0851GR, manufactured by Goodrich Sensors and Integrated Systems. A 2001 Airworthiness Directive required these to be replaced with either a later Goodrich design, part number 0851HL, or with pitots made by Thales, part number C16195AA. Air France chose to equip its fleet with the Thales pitots. In September 2007, Airbus recommended that Thales C16195AA pitot tubes should be replaced by Thales model C16195BA, to address the problem of water ingress which had been observed.[149] Since it was not an Airworthiness Directive, the guidelines allow the operator to apply the recommendations at its discretion. Air France implemented the change on its A320 fleet where the incidents of water ingress were observed, and decided to do so in its A330/340 fleet only when failures occurred.[150]

Starting in May 2008 Air France experienced incidents involving a loss of airspeed data in flight ... in cruise phase on A340s and A330s. These incidents were analysed with Airbus as resulting from pitot probe icing for a few minutes, after which the phenomenon disappeared.

— [148]

After discussing these issues with the manufacturer, Air France sought a means of reducing these incidents, and Airbus indicated that the new pitot probe designed for the A320 was not designed to prevent cruise level ice-over. In 2009, tests suggested that the new probe could improve its reliability, prompting Air France to accelerate the replacement program,[151] but this work had not been carried out on F-GZCP.[19] By 17 June 2009, Air France had replaced all pitot probes on its A330 type aircraft.[150]

On 11 June 2009, a spokesman from the BEA reminded that there was no conclusive evidence at the moment linking pitot probe malfunction to the AF447 crash, and this was reiterated on 17 June 2009 by the BEA chief, Paul-Louis Arslanian.[152][153][154]

In July 2009, Airbus issued new advice to A330 and A340 operators to exchange Thales pitot tubes for tubes from Goodrich Sensors and Integrated Systems.[155][156][157]

On 12 August 2009, Airbus issued three Mandatory Service Bulletins, requiring that all A330 and A340 aircraft be fitted with two Goodrich 0851HL pitot tubes and one Thales model C16195BA pitot (or alternatively three of the Goodrich pitots); Thales model C16195AA pitot tubes were no longer to be used.[158] This requirement was incorporated into Airworthiness Directives issued by the European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) on 31 August[158] and by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) on 3 September.[159] The replacement was to be completed by 7 January 2010. According to the FAA, in its Federal Register publication, use of the Thales model has resulted in "reports of airspeed indication discrepancies while flying at high altitudes in inclement weather conditions", that "could result in reduced control of the airplane." The FAA further stated that the Thales model probe "has not yet demonstrated the same level of robustness to withstand high-altitude ice crystals as Goodrich pitot probes P/N 0851HL,".

On 20 December 2010, Airbus issued a warning to roughly 100 operators of A330, A340-200 and A340-300 aircraft, regarding pitot tubes, advising pilots not to re-engage the autopilot following failure of the airspeed indicators.[160][161][162]

Findings from the flight data recorder

On 27 May 2011, the BEA released an update on its investigation describing the history of the flight as recorded by the flight data recorder. This confirmed what had previously been concluded from post-mortem examination of the bodies and debris recovered from the ocean surface: the aircraft had not broken up at altitude but had fallen into the ocean intact.[2][139] The flight recorders also revealed that the aircraft's descent into the sea was not due to mechanical failure or the aircraft being overwhelmed by the weather, but because the flight crew had raised the aircraft's nose, reducing its speed until it entered an aerodynamic stall.[11][163]

While the inconsistent airspeed data caused the disengagement of the autopilot, the reason the pilots lost control of the aircraft remains something of a mystery, in particular because pilots would normally try to lower the nose in case of a stall.[164][165][166] Multiple sensors provide the pitch (attitude) information and there was no indication that any of them were malfunctioning.[167] One factor may be that since the A330 does not normally accept control inputs that would cause a stall, the pilots were unaware that a stall could happen when the aircraft switched to an alternate mode due to failure of the air speed indication.[163] [Note 6]

In October 2011, a transcript of the voice recorder was leaked and published in the book Erreurs de Pilotage (Pilot Error) by Jean Pierre Otelli,[163][172] The BEA and Air France both condemned the release of this information, with Air France calling it "sensationalized and unverifiable information" that "impairs the memory of the crew and passengers who lost their lives."[173] The BEA would subsequently release its final report on the incident and Appendix 1 contained an official cockpit voice recorder transcript which did not include groups of words deemed to have no bearing on flight.[174]

Third interim report

On 29 July 2011, the BEA released a third interim report on safety issues it found in the wake of the crash.[7] It was accompanied by two shorter documents summarizing the interim report[175] and addressing safety recommendations.[176]

The third interim report stated that some new facts had been established. In particular:

- The pilots had not applied the unreliable airspeed procedure.

- The pilot-in-control pulled back on the stick, thus increasing the angle of attack and causing the aircraft to climb rapidly.

- The pilots apparently did not notice that the aircraft had reached its maximum permissible altitude.

- The pilots did not read out the available data (vertical velocity, altitude, etc.).

- The stall warning sounded continuously for 54 seconds.

- The pilots did not comment on the stall warnings and apparently did not realize that the aircraft was stalled.

- There was some buffeting associated with the stall.

- The stall warning deactivates by design when the angle of attack measurements are considered invalid and this is the case when the airspeed drops below a certain limit.

- In consequence, the stall warning stopped and came back on several times during the stall; in particular, it came on whenever the pilot pushed forward on the stick and then stopped when he pulled back; this may have confused the pilots.

- Despite the fact that they were aware that altitude was declining rapidly, the pilots were unable to determine which instruments to trust: it may have appeared to them that all values were incoherent.[7]

The BEA assembled a human factors working group to analyze the crew's actions and reactions during the final stages of the flight.[177]

A brief bulletin by Air France indicated that "the misleading stopping and starting of the stall warning alarm, contradicting the actual state of the aircraft, greatly contributed to the crew's difficulty in analyzing the situation."[178][179]

Final report

On 5 July 2012, the BEA released its final report on the accident. This confirmed the findings of the preliminary reports and provided additional details and recommendations to improve safety.[1] According to this report the accident resulted from the following succession of events:

- Temporary inconsistency between the airspeed measurements, likely following the obstruction of the pitot probes by ice crystals that, in particular, caused the autopilot disconnection and the reconfiguration to alternate law;

- Inappropriate control inputs that destabilized the flight path;

- The lack of any link by the crew between the loss of indicated speeds called out and the appropriate procedure;

- The late identification by the PNF (Pilot Not Flying) of the deviation from the flight path and the insufficient correction applied by the PF (Pilot Flying);

- The crew not identifying the approach to stall, their lack of immediate response and the exit from the flight envelope;

- The crew's failure to diagnose the stall situation and consequently a lack of inputs that would have made it possible to recover from it.

These events can be explained by a combination of the following factors:

- The feedback mechanisms on the part of all those involved that made it impossible:

- To identify the repeated non-application of the loss of airspeed information procedure and to remedy this,

- To ensure that the risk model for crews in cruise included icing of the Pitot probes and its consequences;

- The absence of any training, at high altitude, in manual aircraft handling and in the procedure for "Vol avec IAS douteuse" (Flight with questionable Indicated Airspeed);

- Task-sharing that was weakened by:

- Incomprehension of the situation when the autopilot disconnection occurred,

- Low-quality management of the startle effect that generated a highly charged emotional factor for the two copilots;

- The lack of a clear display in the cockpit of the airspeed inconsistencies identified by the computers;

- The crew not taking into account the stall warning, which could have been due to:

- A failure to identify the aural warning, due to low exposure time in training to stall phenomena, stall warnings and buffet,

- The appearance at the beginning of the event of transient warnings that could be considered as spurious,

- The absence of any visual information to confirm the approach-to-stall after the loss of the limit speeds,

- The possible confusion with an overspeed situation in which buffet is also considered as a symptom,

- Flight Director indications that may have led the crew to believe that their actions were appropriate, even though they were not,

- The difficulty in recognizing and understanding the implications of a reconfiguration in alternate law with no angle of attack protection.

Passengers and crew

| Nationality | Passengers | Crew | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 0 | 2 | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 58 | 1 | 59 | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 9 | 0 | 9 | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 61 | 11 | 72 | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 26 | 0 | 26 | |

| 4 | 0 | 4 | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 3 | 0 | 3 | |

| 9 | 0 | 9 | |

| 3 | 0 | 3 | |

| 3 | 0 | 3 | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 3 | 0 | 3 | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 2 | 0 | 2 | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 3 | 0 | 3 | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 1 (3) | 0 | 1 (3) | |

| 6 | 0 | 6 | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 5 | 0 | 5 | |

| 2 | 0 | 2 | |

| Total (33 nationalities) | 216 | 12 | 228 |

The aircraft was carrying 216 passengers and 12 aircrew in two cabins of service.[3][187][188] Among the 216 passengers were one infant, seven children, 82 women, and 126 men.[51] There were three pilots: 58-year-old flight captain Marc Dubois had joined Air France in 1988 and had approximately 11,000 flight hours, including 1,700 hours on the Airbus A330; the two first officers, 37-year-old David Robert and 32-year-old Pierre-Cédric Bonin, had over 9,000 flight hours between them. Of the 12 crew members, 11 were French and one Brazilian.[189]

According to an official list released by Air France on 1 June 2009,[190] the majority of passengers were French, Brazilian, or German citizens.[191][192] Attributing nationality was complicated by the holding of multiple citizenship by several passengers. The nationalities as released by Air France are shown in the table to the right. The passengers included business and holiday travelers.[193]

Air France had gathered approximately 60–70 relatives and friends to pick up arriving passengers at Charles de Gaulle Airport. Many of the passengers on Flight 447 were connecting to other destinations worldwide, so other parties anticipating the arrival of passengers were at various connecting airports.[194]

On 20 June 2009, Air France announced that each victim's family would be paid roughly €17,500 in initial compensation.[195] Wrongful death lawsuits maintaining that design and manufacturing defects supplied pilots with incorrect information, rendering them incapable of maintaining altitude and air speed, have been filed in US Courts.[196]

Notable passengers

- Prince Pedro Luís of Orléans-Bragança, third in succession to the abolished throne of Brazil.[197][198] He had dual Brazilian-Belgian citizenship. He was returning home to Luxembourg from a visit to his relatives in Rio de Janeiro.[199][200]

- Silvio Barbato, composer and former conductor of the symphony orchestras of the Cláudio Santoro National Theater in Brasilia and the Rio de Janeiro Municipal Theatre; he was en route to Kiev for engagements there.[201][202]

- Fatma Ceren Necipoğlu, Turkish classical harpist and academic of Anadolu University in Eskişehir; she was returning home via Paris after performing at the fourth Rio Harp Festival.[203]

- Pablo Dreyfus from Argentina, a campaigner for controlling illegal arms and the illegal drugs trade.[204]

Other incidents

Shortly after the crash, Air France changed the number of the regular Rio de Janeiro-Paris flight from AF447 to AF445.[205]

Some six months later, on 30 November 2009, Air France Flight 445 (F-GZCK) made a mayday call because of severe turbulence around the same area and at a similar time to when Flight 447 had crashed. Because the pilots could not obtain immediate permission from air traffic controllers to descend to a less turbulent altitude, the mayday was to alert other aircraft in the vicinity that the flight had deviated from its normal flight level. This is standard contingency procedure when changing altitude without direct ATC authorization. After 30 minutes of moderate to severe turbulence the flight continued normally. The flight landed safely in Paris six hours and 40 minutes after the mayday call.[206][207]

On 6 September 2011, the French media reported that the BEA was investigating a similar incident on an Air France flight from Caracas to Paris.[clarification needed] The aircraft in question was an Airbus A340.[208]

There have been several cases where inaccurate airspeed information led to flight incidents on the A330 and A340. Two of those incidents involved pitot probes.[Note 7] In the first incident, an Air France A340-300 (F-GLZL), en route from Tokyo, Japan, to Paris, France, experienced an event at 31,000 feet (9,400 m) in which the airspeed was incorrectly reported and the autopilot automatically disengaged. Bad weather, together with obstructed drainage holes in all three pitot probes, were subsequently found to be the cause.[209] In the second incident, an Air France A340-300 (F-GLZN), en route from Paris to New York, encountered turbulence followed by the autoflight systems going offline, warnings over the accuracy of the reported airspeed and two minutes of stall alerts.[209]

Another incident on TAM Flight 8091, from Miami to Rio de Janeiro on 21 May 2009, involving an A330-200, showed a sudden drop of outside air temperature, then loss of air data, the ADIRS, autopilot and autothrust.[210] The aircraft fell 1,000 metres (3,300 ft) before being manually recovered using backup instruments. The NTSB also examined a similar 23 June 2009 incident on a Northwest Airlines flight from Hong Kong to Tokyo,[210] concluding in both cases that the aircraft operating manual was sufficient to prevent a dangerous situation from occurring.[211]

Media speculation and independent analysis

Prior to the publication of the final report by the BEA in July 2012, there was considerable public speculation and expert opinion published about the cause of the accident.

New York Times

In May 2011, Wil S. Hylton of The New York Times commented that the crash "was easy to bend into myth" because "no other passenger jet in modern history had disappeared so completely – without a Mayday call or a witness or even a trace on radar." Hylton explained that the A330 "was considered to be among the safest" of the passenger aircraft. Hylton added that when the aircraft disappeared, "Flight 447 seemed to disappear from the sky, it was tempting to deliver a tidy narrative about the hubris of building a self-flying aircraft, Icarus falling from the sky. Or maybe Flight 447 was the Titanic, an uncrashable ship at the bottom of the sea."[127] Dr. Guy Gratton, an aviation expert from the Flight Safety Laboratory at Brunel University, said "This is an air accident the like of which we haven't seen before. Half the accident investigators in the Western world – and in Russia too – are waiting for these results. This has been the biggest investigation since Lockerbie. Put bluntly, big passenger planes do not just fall out of the sky."[212]

Sullenberger

In a July 2011 article in Aviation Week, C. B. "Sully" Sullenberger was quoted as saying the crash was a "seminal accident."

"We need to look at it from a systems approach, a human/technology system that has to work together. This involves aircraft design and certification, training and human factors. If you look at the human factors alone, then you're missing half or two-thirds of the total system failure ..."

Sullenberger suggested that pilots would be able to better handle upsets of this type if they had an indication of the wing's angle of attack (AoA). "We have to infer angle of attack indirectly by referencing speed. That makes stall recognition and recovery that much more difficult. For more than half a century, we've had the capability to display AoA (in the cockpits of most jet transports), one of the most critical parameters, yet we choose not to do it."[213]

The BEA recommended that EASA and the FAA should consider making it compulsory for passenger aircraft to be equipped with an angle of attack display.[214]

BBC / Nova

A one hour documentary titled "Lost: The Mystery of Flight 447" detailing an independent investigation into the crash was produced by Darlow Smithson in 2010 for Nova and the BBC. It employed the skills of an expert pilot, an expert accident investigator, an aviation meteorologist and an aircraft structural engineer. Using the publicly available evidence and information, without the black boxes, a critical chain of events was postulated.[215][216][217][218]

Erreurs de Pilotage

On 6 December 2011 Popular Mechanics magazine published an English translation of the analysis of the transcript of the cockpit voice recorder controversially leaked in the book Erreurs de Pilotage.[163][219] It blames one of the co-pilots for stalling the aircraft while the flight computer was under alternate law at high altitude. A series of human errors or failings were listed as the most direct cause of this incident.[163]

Daily Telegraph

On 28 April 2012 in The Daily Telegraph, the British journalist Nick Ross published a comparison of Airbus and Boeing flight controls; unlike the control yoke used on Boeing flight decks, the Airbus side stick controls give no sensory or tactile and little visual feedback to the second pilot. Ross reasoned this might have been a factor in the failure of Robert and Dubois to countermand the manual input by pilot Bonin that some independent analysts suspect proved fatal for the aircraft.[Note 8][220] Nick Ross's thesis was also broadcast in the US.[221]

Mayday program

In March 2012 it was announced that the accident would be the subject of the last episode of the 12th season of the Mayday Canadian documentary television series.

See also

- AeroPeru Flight 603 - Crashed due to a similar static port blockage.

- Yemenia Flight 626 - Another crash at sea in the same month in 2009.

- Adam Air Flight 574

Notes

- ^ The first interim report, released on 2 July 2009, shows that the series were sent over a four-minute period.

- ^ On the map, page 13 the coordinates in the Interim report f-cp090601ae on the accident on 1 June 2009 to the Airbus A330-203 registered F-GZCP operated by Air France flight AF 447 Rio de Janeiro – Paris (Original French version: Rapport d'étape f-cp090601e Accident survenu le 1er juin 2009 à l'Airbus A330-203 immatriculé F-GZCP exploité par Air France vol AF 447 Rio de Janeiro – Paris, with the information on page 13) is referenced as the "last known position" (French: Dernière position connue, "last known position").

- ^ More precisely: that after one of the three independent systems had been diagnosed as faulty and excluded from consideration, the two remaining systems disagreed.

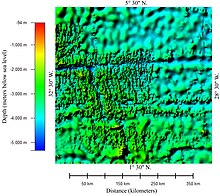

- ^ The areas showing detailed bathymetry were mapped using multibeam bathymetric sonar. The areas showing very generalized bathymetry were mapped using high-density satellite altimetry.

- ^ The airliner was considered to be in a nearly level attitude, but with a high rate of descent when it collided with the surface of the ocean. That impact caused high deceleration and compression forces on the airliner, as shown by the deformations that were found in the recovered wreckage.

- ^ Some reports have described this as a deep stall,[168] but this was a steady state conventional stall.[169] A deep stall is associated with an aircraft with a T-tail, but this aircraft does not have a T-tail.[170] The BEA described it as a "sustained stall"[171]

- ^ For an explanation of how airspeed is measured, see Air Data Reference.

- ^ From The Telegraph article: "It seems surprising that Airbus has conceived a system preventing one pilot from easily assessing the actions of the colleague beside him. And yet that is how their latest generations of aircraft are designed. The reason is that, for the vast majority of the time, side sticks are superb. ... Boeing has always begged to differ, persisting with conventional controls on its fly-by-wire aircraft, including the new 787 Dreamliner, introduced into service this year. Boeing's cluttering and old-fashioned levers still have to be pushed and turned like the old mechanical ones, even though they only send electronic impulses to computers. They need to be held in place for a climb or a turn to be accomplished, which some pilots think is archaic and distracting. ... Whatever the cultural differences, there is a perceived safety issue, too. The American manufacturer was concerned about side sticks' lack of visual and physical feedback. Indeed, it is hard to believe AF447 would have fallen from the sky if it had been a Boeing. Had a traditional yoke been installed on Flight AF447, Robert would surely have realised that his junior colleague had the lever pulled back and mostly kept it there. When Dubois returned to the cockpit he would have seen that Bonin was pulling up the nose. ... It is extremely unlikely that there will ever be another disaster quite like AF447. Crews have already had the lessons drummed into them and routine refresher courses on simulators have been upgraded to replicate AF447 high-level stalls. Airbus has an excellent safety record, at least as good as Boeing, and the A330 is an extremely trustworthy aircraft. Flying is easily the least dangerous way to travel, far safer than a car. But while more of us take to the air each year, a single crash is enough to damage confidence."

References

- ^ a b c d "Final report on the accident on 1st June 2009 to the Airbus A330-203 registered F-GZCP operated by Air France flight AF 447 Rio de Janeiro – Paris" (English edition). BEA. July 2012. p. 202.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Interim report on the accident on 1 June 2009 to the Airbus A330-203 registered F-GZCP operated by Air France flight AF 447 Rio de Janeiro – Paris" (PDF). Paris: Bureau d'Enquêtes et d'Analyses pour la sécurité de l'aviation civile (BEA). 2 July 2009. Retrieved 4 July 2009. (Original French version here [1]).

- ^ a b c d "Accident description F-GZCP". Flight Safety Foundation. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ^ Ubalde, Joseph Holandes (2 June 2009). "Pinoy seaman in Atlantic plane crash was supposed to go home". GMA Network. Retrieved 2 June 2011.

- ^ "Plane Crash Info". Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ^ "Search intensifies for vanished Air France flight". ABS–CBN Corporation. Agence France-Presse. 2 June 2009. Archived from the original on 14 June 2011. Retrieved 2 June 2011.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c "Interim report no. 3: on the accident on 1 June 2009 to the Airbus A330-203 registered F-GZCP operated by Air France flight AF 447 Rio de Janeiro – Paris" (PDF). Bureau d'Enquêtes et d'Analyses pour la sécurité de l'aviation civile. 29 July 2011. Retrieved 17 December 2011."Original version" (PDF) (in French). 29 July 2011.

- ^ Nicola Clark (29 July 2011). "Report on Air France Crash Points to Pilot Training Issues". The New York Times.

- ^ Third interim report, section 3, page 77

- ^ Shaikh, Thair (27 May 2011). "Speed sensor failure caused Air France crash – report". CNN. Retrieved 27 May 2011.

- ^ a b c "Flight AF 447 on 1st June 2009, A330-203, registered F-GZCP, 27 May 2011 briefing". BEA.

- ^ Accident description at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 3 May 2012.

- ^ "Flight AF 447 on 1st June 2009". BEA. 2011. Retrieved 2 June 2011.

- ^ http://www.bea.aero/docspa/2009/f-cp090601.en/pdf/f-cp090601.en.pdf

- ^ Press release, 30 May 2012

- ^ a b c "Air France Flight AF 447" (Press release). Airbus. 1 June 2009. Archived from the original on 22 April 2009. Retrieved 5 June 2009.

- ^ French registration data for F-GZCP

- ^ "All Accident + Incidents 2006". Jet Airliner Crash Data Evaluation Centre. Archived from the original on 7 June 2009. Retrieved 4 June 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c "JACDEC Special accident report Air France Flight 447". Jet Airliner Crash Data Evaluation Centre. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ^ BEA first interim report, section 1.17.2.3 "Air France procedures"

- ^ BEA first interim report, section 1.17.2.2

- ^ BEA final report, section 2.1.1.3.1 "Choice of time period"

- ^ BEA final report, section 2.1.2.3 "The excessive amplitude of these [nose-up] inputs made them unsuitable and incompatible with the recommended aeroplane handling practices for high altitude flight."

- ^ "Interim Report n°3, On the accident on 1 June 2009 to the Airbus A330-203 registered F-GZCP" (PDF). BEA. 29 July 2011.

- ^ "Recording Indicates Pilot Wasn't In Cockpit During Critical Phase". 23 May 2011.

- ^ "Concerns over recovering AF447 recorders". Aviation Week. Aviation Week. 3 June 2009. Retrieved 7 June 2009.

- ^ "Data Link Messages Hold Clues to Air France Crash". Aviation Week. Aviation Week. 7 June 2009. Retrieved 8 June 2009.

- ^ a b "France2 newscast". France2 Online. France Televisions. 4 June 2009, 20h. Archived from the original on 20 June 2009. Retrieved 7 June 2009.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)[dead link] - ^ "France 2" (video) (in French).[dead link]

- ^ "Airbus 330 – Systems – Maintenance System" (PDF). Flight crew operating manual. Retrieved 7 June 2009.

- ^ a b "Joint aircraft system/component code table and definitions" (PDF). Federal Aviation Administration, USA. Retrieved 6 June 2009.

- ^ "Air France Captain Dubois Let Down by 1-Pound Part, Pilots Say". Bloomberg. 11 June 2009. Retrieved 11 June 2009.

- ^ "Airbus 330 – Systems – Flight Controls". Flight crew operating manual. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 June 2009. Retrieved 7 June 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Crash: Air France A332 over Atlantic on 1 June 2009, aircraft impacted ocean". Retrieved 6 June 2009.

- ^ "Airbus ISIS". Flight crew operating manual. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 June 2009. Retrieved 8 June 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Airbus 330 – Systems – Communications" (PDF). Flight crew operating manual. Retrieved 7 June 2009.

- ^ "Crash: Air France A332 over Atlantic on 1 June 2009, aircraft lost". Aviation Herald. 2 June 2009.

- ^ "Airbus Flight Control Laws". Airbus. Retrieved 3 June 2009.

- ^ "Avionics Product Range". Airbus. Retrieved 21 August 2011.

- ^ BEA final report, section 1.7.1, page 46

- ^ Vasquez, Tim (3 June 2009). "Air France Flight 447: A detailed meteorological analysis".

- ^ "Air France Flight #447: did weather play a role in the accident?". Cooperative Institute for Meteorological Satellite Studies. 1 June 2009.

- ^ "A Meteosat-9 infrared satellite image". BBC News. Retrieved 1 January 2010.

- ^ "Plane Vanished in Region Known for Huge Storms". Fox News. 3 June 2009.

- ^ BEA final report, section 1.11.2, page 58

- ^ Woods, Richard; Campbell, Matthew (7 June 2009). "Air France 447: The computer crash". The Times. UK. para 16[dead link]

- ^ BEA final report, section 2.1.1.1, page 167

- ^ "12 similar flights deepen Air France 447 mystery". CNN. 9 June 2009. Archived from the original on 21 April 2010. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Reuters Two Lufthansa jets to give clues on AirFrance

- ^ BEA first interim report, section 1.9.2 "Coordination between the control centres"

- ^ a b "French plane lost in ocean storm". BBC News. 1 June 2009. Archived from the original on 3 June 2009. Retrieved 1 June 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) "At 0530 GMT, Brazil's air force launched a search-and-rescue mission, sending out a coast guard patrol aircraft and a specialised air force rescue aircraft." "France is despatching three search planes based in Dakar" - ^ "Un avión de la Guardia Civil contra la inmigración también busca el avión desaparecido". El Mundo (in Spanish). 1 June 2009. Archived from the original on 5 June 2009. Retrieved 1 June 2009.

El avión Casa 235 de la Guardia Civil utilizado ... ha sido enviado a primera hora de la tarde a participar en las tareas de búsqueda del aparato de Air France desaparecido en las últimas horas cuando cubría el trayecto Río de Janeiro y París, informaron fuentes del Ministerio del Interior.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Premières précisions sur l'Airbus d'Air France disparu". L'Express (in French). 1 June 2009. Archived from the original on 5 June 2009. Retrieved 1 June 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ ""Aucun espoir" pour le vol Rio-Paris d'Air France". L'Express (in French). 1 June 2009. Archived from the original on 5 June 2009. Retrieved 1 June 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Williams, David (1 June 2009). "Air France 'loses hope' after plane drops off the radar en route from Brazil to Paris with 228 people on board". Daily Mail. UK. Archived from the original on 8 June 2009. Retrieved 1 June 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Chrisafis, Angelique (1 June 2009). "French plane crashed over Atlantic". The Guardian. UK. Archived from the original on 11 June 2009. Retrieved 1 June 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Prospect slim of finding plane survivors". KKTV-TV. Associated Press. 1 June 2009. Retrieved 16 February 2011.

- ^ "Brazilian Air Force Bulletin Number 6" (in Portuguese). 2 June 2009.

- ^ Negroni, Christine (2 June 2009). "France and Brazil Press Search for Missing Plane". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 6 June 2009. Retrieved 2 June 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "No survivors found in wreckage of Air France jet, official says". CNN. 2 June 2009. Archived from the original on 6 June 2009. Retrieved 2 June 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Ocean search finds plane debris". BBC. 2 June 2009. Archived from the original on 3 June 2009. Retrieved 2 June 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "José Alencar decreta três dias de luto oficial por vítimas do Airbus" (in Portuguese). Globo. 2 June 2009. Archived from the original on 12 June 2009. Retrieved 2 June 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b BEA first interim report, section 1.16.1.3 "Resources deployed by France"

- ^ Evaristo Sa (3 June 2009). "Navy ships seek to recover Air France crash debris". Agence France-Presse.

- ^ "Mini-subs sent to look for jet". News24. 2 June 2009. Archived from the original on 17 January 2010. Retrieved 2 June 2009.

- ^ BEA first interim report, section 1.16.1.1 "Context of the searches"

- ^ "AF 447 may have come apart before crash: experts". Associated Press. 3 June 2009. Archived from the original on 6 June 2009. Retrieved 3 June 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Brazilian Air Force Finds More Debris from Flight 447". CRI English. 3 June 2009. Archived from the original on 11 June 2009. Retrieved 3 June 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Buscas à aeronave do voo AF 447 da Air France". Brazilian Navy. 4 June 2009. Retrieved 4 June 2009. (Archive)

- ^ a b "France sends nuclear sub to hunt for jet wreckage". CBC News. 5 June 2009. Archived from the original on 8 June 2009. Retrieved 9 June 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "More bodies found near Air France crash site". Reuters. 7 June 2009. Archived from the original on 8 June 2009. Retrieved 8 June 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Sibaja, Marco and Vandore, Emma (10 June 2009). "Sub helps in hunt for black boxes at Air France crash site". The News Tribune. Associated Press. Retrieved 11 June 2009.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) [dead link] - ^ "First debris recovered from Air France Flight 447 crash". USA Today. 4 June 2009. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- ^ "Air France plane: debris 'is not from lost aircraft'". The Daily Telegraph. London. 5 June 2009. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- ^ Sibaja, Marco; Keller, Greg (6 June 2009). "No wreckage found from doomed Air France plane". The Guardian. London. Associated Press. Retrieved 31 May 2011.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Bodies 'found' from missing plane". BBC News. 6 June 2009. Archived from the original on 8 June 2009. Retrieved 6 June 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Brazil: Bodies found near Air France crash site". MSNBC. 6 June 2009. Archived from the original on 7 June 2009. Retrieved 6 June 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "DECEA reinforces that the debris identified in the first days of the search are part of the Air France craft". Brazilian Ministry of Defense. 5 June 2009. Retrieved 6 June 2009.[dead link]

- ^ "Air France tail section recovered". BBC News. 8 June 2009. Retrieved 1 January 2010.

- ^ Campbell, Matthew (14 June 2009). "Crash jet 'split in two at high altitude'". The Times. UK. Retrieved 14 June 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Information on Searches of the Air France Flight 447". Brazilian Ministry of Defense. 16 June 2009. Archived from the original on 20 June 2009. Retrieved 17 June 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Autopsies suggest Air France jet broke up in sky". Yahoo! News. 17 June 2009. Archived from the original on 19 June 2009. Retrieved 17 June 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) [dead link] - ^ "Information on Searches of the Air France Flight 447". Brazilian Ministry of Defense. 14 June 2009. Archived from the original on 20 June 2009. Retrieved 15 June 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Information on Searches of the Air France Flight 447". Brazilian Ministry of Defense. 9 June 2009. Archived from the original on 12 June 2009. Retrieved 12 June 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Information on Searches of the Air France Flight 447". Brazilian Ministry of Defense. 11 June 2009. Archived from the original on 15 June 2009. Retrieved 12 June 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Bremner, Charles; Tedmanson, Sophie (23 June 2009). "Hopes of finding Air France Airbus black boxes dashed". The Times. London. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- ^ "INFO FIGARO – AF 447 : le corps du pilote identifié". Le Figaro (in French). France. 25 June 2009.

- ^ a b BEA second interim report, section 1.13

- ^ a b "Lost jet data 'may not be found'". BBC. 3 June 2009. Archived from the original on 4 June 2009. Retrieved 3 June 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Negroni, Christine (3 June 2009). "Wreckage of Air France Jet is Found, Brazil says". New York Times. Archived from the original on 5 June 2009. Retrieved 4 June 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Johan Strümpfer (16 October 2006). "Deep Ocean Search Planning: A Case Study of problem Solving". Archived from the original on 6 June 2009. Retrieved 4 June 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Finding the black box of Air France Flight 447 will be challenging: French probe team". International Business Times. 4 June 2009. Archived from the original on 7 June 2009. Retrieved 4 June 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)[dead link] - ^ "Black Box: Locating Flight Recorder of Air France Flight 447 in Atlantic Ocean". 8 June 2009. Archived from the original on 13 June 2009. Retrieved 15 June 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Brazil ends search for Air France bodies". Sydney Morning Herald. 27 June 2009. Archived from the original on 27 June 2009. Retrieved 27 June 2009.

Brazil's military said it had ended its search for more bodies and debris ... The operation, which also had the help of French vessels and French, Spanish and US aircraft, recovered 51 bodies of the 228 people who were on board ... air force spokesman Lieutenant Colonel Henry Munoz told reporters in Recife late Friday.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ BEA first interim report, page 46

- ^ "Investigators say they have no confirmed black-box signals". France 24.com. 27 June 2009. Archived from the original on 26 June 2009. Retrieved 23 June 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Air France 447's black boxes: search to resume". csmonitor.com. 17 July 2009.

- ^ Clark, Nicola (30 July 2009). "Airbus Offers to Pay for Extended Crash Search". The New York Times. Retrieved 1 August 2009.

- ^ "Press release 20 August 2009" (Press release). BEA. 20 August 2009. Retrieved 31 August 2009.

- ^ "Search for Flight 447 data recorders to resume". CNN. 13 December 2009.

- ^ Keller, Greg (11 March 2010). "Search for Air France black boxes delayed". The Seattle Times. Associated Press. Retrieved 16 February 2011.

- ^ Charlton, Angela (17 February 2010). "Victims' families cheer new search for Flight 447". AllBusiness.com. Associated Press. Retrieved 8 January 2011.[dead link]

- ^ Laurence Frost; Andrea Rothman (4 February 2010). "Air France 447 Black Box May Be Found by End of March, BEA Says". Business Week. Bloomberg.[dead link]

- ^ Laurence Frost; Andrea Rothman (4 February 2010). "Air France Black-Box Search Narrowed by Fresh Data (Update1)". Business Week. Bloomberg.[dead link]

- ^ "Sea Search Operations, Phase 3". BEA. Retrieved 19 July 2012.

- ^ "Search ships head to new AF447 search zone". airfrance447.com. 30 March 2010. Archived from the original on 21 April 2010. Retrieved 2 April 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Undersea Search Resumes for France Flight 447". Discovery News. 30 March 2010. Archived from the original on 2 April 2010. Retrieved 2 April 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ La zone des boîtes noires du vol Rio-Paris localisée

- ^ Redirected AF447 search fails to locate A330 wreck

- ^ "Air France to resume Atlantic flight recorder search". BBC News. 25 November 2010. Archived from the original on 26 November 2010. Retrieved 25 November 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b In search of Air France Flight 447 Lawrence D. Stone Institute of Operations Research and the Management Sciences 2011

- ^ "Images of Flight 447 Engines, Wing, Fuselage, Landing Gear". BEA. Retrieved 8 April 2011.

- ^ Willsher, Kim (4 April 2011). "Air France plane crash victims found after two-year search". The Guardian. London.

- ^ . Reuters. 4 April 2011 http://www.abc.net.au/news/stories/2011/04/05/3182215.htm.

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "Press release, 19 April 2011". BEA. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- ^ "Bits of Air France Flight 447 found in Atlantic". CBS. 3 April 2011. Archived from the original on 4 April 2011. Retrieved 3 May 2011.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Remora 6000 ROV Specifications" (PDF). Retrieved 28 April 2011.

- ^ The Remora 6000 remotely operated vehicle was designed and constructed by Phoenix International Holdings, Inc. of Largo, Maryland, United States.

- ^ Press release, 19 April 2011 Retrieved 23 April 2011

- ^ "Solid-State FDR System including Crash Survivable Memory Unit (CSMU)" (PDF). Retrieved 27 April 2011.

- ^ Press release, 27 April 2011 Retrieved 27 April 2011

- ^ "Memory unit from the Flight Data Recorder (FDR) – Photos". Retrieved 1 May 2011.

- ^ "Investigators recover second Air France black box". Yahoo! News. 2 May 2011. Retrieved 1 May 2011.[dead link]