Japanese invasions of Korea (1592–1598): Difference between revisions

rv banned user's edits |

|||

| Line 1,052: | Line 1,052: | ||

=== Cruelty and war crimes === |

=== Cruelty and war crimes === |

||

Participants from the all three countries committed war crimes during the conflict. |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | According to [[Stephen Turnbull (historian)|Stephen Turnbull]], a historian specializing in |

||

| ⚫ | According to [[Stephen Turnbull (historian)|Stephen Turnbull]], a historian specializing in Japanese history, Japanese troops committed crimes against civilians in battles and killed indiscriminately, including farm animals.<ref name="turnbull50-1"/> Outside of the main battles, Japanese raided Korean habitations to “kill, rape and steal in a… cruel manner…”<ref name="turnbull169">Turnbull, Stephen. 2002, p. 169.</ref> Japanese soldiers treated their own peasants no better than the captured Koreans and worked many to death by starvation and [[flogging]].<ref name="turnbull206-7">Turnbull, Stephen. 2002, pp. 206-7.</ref> The Japanese collected enough ears and noses<ref name="mimi">{{Citation |

||

| last = KRISTOF |

| last = KRISTOF |

||

| Line 1,068: | Line 1,067: | ||

| pages = |

| pages = |

||

| year = 1997 |

| year = 1997 |

||

| date |

| date= 1997-09-14 |

||

| url = http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9C03EED71E39F937A2575AC0A961958260&sec=&spon=&pagewanted=print}}</ref> (cutting ears off of enemy bodies for making casualty counts was an accepted practice) to build a large mound near |

| url = http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9C03EED71E39F937A2575AC0A961958260&sec=&spon=&pagewanted=print}}</ref> (cutting ears off of enemy bodies for making casualty counts was an accepted practice) to build a large mound near Hideyoshi’s Great Buddha, called the [[Mimizuka]], or “the Mound of Ears”.<ref name="turnbull195">Turnbull, Stephen. 2002, p. 195.</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | The Chinese were said to be no better than the Japanese in the amount of destruction they caused and the degree of the crimes they committed.<ref name="turnbull235" /> They even attacked Korean forces,<ref name="turnbull231"/> and they did not distinguish between Korean civilians and the Japanese.<ref name="turnbull236-7">Turnbull, Stephen. 2002, p. 236-7.</ref> Military competition resulted between the Chinese generals and the Koreans, and by the end of the war led to the indiscriminate killing of Korean civilians in [[Namhae]], whom the Chinese General [[Chen Lin (Ming)|Chen Lin]] labelled as Japanese collaborators in order to gain a larger head count.<ref name="turnbull236-7"/> |

||

Korean [[bandits]] and [[highwaymen]] took advantage of the chaos during the war to form raiding parties and rob other Koreans.<ref name="turnbull170">Turnbull, Stephen. 2002, p. 170.</ref> The inhabitants of Hamgyong Province (in the northern part of the Korean peninsula) surrendered their fortresses, turning in their generals and governing officials to the Japanese invaders, as they felt oppressed by the Joseon government.<ref name="turnbull77-8"/> Many Korean generals and government officials deserted their posts whenever danger seemed imminent.<ref name="turnbull53-4" /> |

|||

=== Legacy === |

=== Legacy === |

||

Revision as of 22:47, 15 March 2008

| Japanese invasions of Korea | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

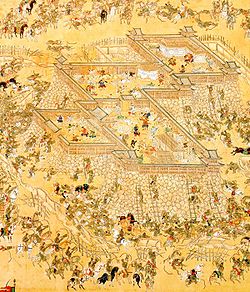

The Japanese landing on Busan. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Korea under the Joseon Dynasty, China under the Ming Dynasty, Jianzhou Jurchens | Japan under Toyotomi Hideyoshi | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Korea China |

Japan | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Korea China |

Japan | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

Korea

military total 300,000[3]

China |

Japan military total 130,000 | ||||||

| civilian + military total 1,000,000[6] | |||||||

| Japanese invasions of Korea | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Korean name | |||||||

| Hangul | 임진왜란 / 정유재란 | ||||||

| Hanja | 壬辰倭亂 / 丁酉再亂 | ||||||

| |||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||

| Kanji | 文禄の役 / 慶長の役 | ||||||

Two Japanese invasions of Korea and subsequent battles on the Korean peninsula took place during the years 1592–1598. Toyotomi Hideyoshi led the newly unified Japan into the first invasion (1592-1593) with the professed goal of conquering Korea, the Jurchens, Ming Dynasty China, and India.[7] The second invasion (1594-1596) had no lofty goal of world conquest and was aimed rather solely as a retaliatory offensive against the Koreans.[7] The invasions are also known as Hideyoshi's invasions of Korea, the Seven Year War (in reference to its span) and the Imjin War (in reference to the "Imjin" year of the sexagenary cycle in Korean).[8] The Japanese name of the war means, "Joseon Campaign"; and the Chinese, "the Eastern Pacification".[9]

Name

The first invasion (1592–1593) is literally called the "Japanese (= 倭 |wae|) War (= 亂 |ran|) of Imjin" (1592 being an imjin year in the sexagenary cycle) in Korean and Bunroku no eki in Japanese (Bunroku referring to the Japanese era under the Emperor Go-Yōzei, spanning the period from 1592 to 1596). The second invasion (1597–1598) is called the "Second War of Jeong-yu" and "Keichō no eki", respectively. In Chinese, the wars are referred to as the "Renchen (the information about the Imjin year also applies here) War to Defend the Nation" or the "Wanli Korean Campaign", after then reigning Chinese emperor.

Invasion

Initially, the Japanese forces saw successes on land and consistent failures at sea. The Japanese forces came to suffer heavily as their communication and supply lines were thinned. The Korean navy starved the Japanese forces by successfully intercepting the Japanese supply fleets on the western waters of the peninsula, to which most major rivers of the Korean peninsula flow. Ming China under Emperor Wanli brought about a military and diplomatic intervention to the conflict, which China understood as a challenge to its tributary system.[10] The war stalled for five years during which the three countries tried to negotiate a peaceful compromise; however, Japan invaded Korea a second time in 1597. The war concluded with the naval battle at Noryang. All of the Japanese forces in Korea had retreated by the 12th lunar month of 1598 and returned to Japan after the devastating defeat dealt by the Korean navy.

Effects

| History of Korea |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

|

|

In addition to the human losses, Korea suffered tremendous cultural, economic, and infrastructural damage, including a large reduction in the amount of arable land,[8] destruction and confiscation of significant artworks, artifacts, and historical documents, and abductions of artisans and technicians.[11] The heavy financial burden placed on China by the war adversely affected its military capabilities and contributed to the fall of the Ming Dynasty and the rise of the Qing Dynasty.[12] However, the sinocentric tributary system that Ming had defended was restored by Qing, and the normal trade relations between Korea and Japan continued.[13]

Background

Korea and China before the war

In 1392, the Korean General Yi Seong-gye led a successful coup against King U of the Goryeo Dynasty, and founded Joseon.[14] In search of a justification for its rule given the lack of a royal bloodline, the new regime received recognition from China and integration into its tributary system within the context of the Mandate of Heaven.[15] Under Ashikaga Yoshimitsu's reign during the late 15th century, Japan, too, gained a seat in the tributary system (lost by 1547, see hai jin).[16][17] Within this tributary system, China assumed the role of a big brother, Korea the middle brother, and Japan the younger brother.[18]

Unlike the situation over one thousand years earlier when Chinese dynasties had an antagonistic relationship with the largest of the Korean polities (Goguryeo), Ming China had close trading and diplomatic relations with the Joseon Dynasty, which also enjoyed continuous trade relations with Japan.[19]

The two dynasties, Ming and Joseon, shared much in common: both emerged during the fourteenth century at the fall of Mongolian rule, embraced Confucian ideals in society, and faced similar external threats (the Jurchen raiders and the Wokou pirates).[20] Internally, both China and Korea were troubled with fights among competing political factions, which would significantly influence decisions made by the Koreans prior to the war, and those made during the war by the Chinese.[21][22] Dependence on each other for trade and also having common enemies resulted in Korea and Ming China having a friendly relationship.

Toyotomi Hideyoshi and his preparations

By the last decade of the 16th century, Toyotomi Hideyoshi as daimyō had unified all of Japan in a brief period of peace. Since Hideyoshi came to hold power in the presence of a legitimate Japanese imperial line, he sought for military power to legitimize his rule and to decrease his dependence on the imperial authority.[23] It is said that Hideyoshi planned for an invasion of China to fulfill the dreams of his late leader Oda Nobunaga,[24] and to mitigate the possible threat of civil disorder or rebellion posed by the excess number of samurai and soldiers.[25] But it is quite possible that Hideyoshi might have set a more realistic goal of subjugating the smaller neighbouring states (i.e. Ryukyus, Luzon, Taiwan, and Korea), and treating the larger or more distant countries as trading partners, as [23] all throughout the invasion of Korea, Hideyoshi sought for legal tally trade with China[23] Hideyoshi's need for military supremacy as a justification for his rule which lacked royal background could, on an international level, translate into a Japanocentric order with Japan's neighbouring countries below Japan.[23] Historian Kenneth M. Swope identifies a rumor circulating at the time that Hideyoshi could have been a Chinese who fled to Japan from the law, and therefore sought revenge against China.[26]

The defeat of the Odawara-based Hōjō clan in 1590[27] finally brought about the second unification of Japan,[28] and Hideyoshi began preparing for the next war. Beginning in March 1591, the Kyūshū daimyō and their labor forces constructed a castle at Nagoya (in modern-day Karatsu) as the center for the mobilization of the invasion forces.[29]

Hideyoshi planned for a possible war with Korea long before completing the unification of Japan, and made preparations on many fronts. As early 1578, Hideyoshi, then battling under Nobunaga against Mōri Terumoto for control of the Chūgoku region of Japan, informed Terumoto of Nobunaga's plan to conquer China.[30] In 1592 Hideyoshi sent a letter to the Philippines demanding tribute from the governor general and stating that Japan had already received tribute from Korea (which was a misunderstanding, as explained below) and the Ryukyus.[31]

As for the military preparations, the construction of as many as 2,000 ships may have begun as early as 1586.[32] To estimate the strength of the Korean military, Hideyoshi sent an assault force of 26 ships to the southern coast of Korea in 1587, and he concluded that the Koreans were incompetent.[33] On the diplomatic front, Hideyoshi began to establish friendly relations with China long before completing the unification of Japan and helped to police the trade routes against the wakō.[34]

Diplomatic dealings between Japan and Korea

In 1587, Hideyoshi sent his first envoy Tachibana Yasuhiro,[35] to Korea, which was at the time ruled under King Seonjo[36] to re-establish diplomatic relations between Korea and Japan (broken since a devastating pirate raid in 1555)[37], which Hideyoshi hoped to use as a foundation to induce the Yi Court to join Japan in a war against China.[38] Yasuhiro, with his warrior background and an attitude disdainful of the Korean officials and their customs, which he considered effeminate, failed to receive the promise of future ambassadorial missions from Korea.[39] Around May 1589, Hideyoshi's second embassy, consisting of Sō Yoshitoshi (or Yoshitomo),[40] Gensho and Tsuginobu reached Korea and secured the promise of a Korean embassy to Japan in exchange for the Korean rebels which had taken refuge in Japan.[39] In fact, in 1587 Hideyoshi had ordered Sō Yoshinori, the father of Yoshitoshi and the daimyō of Tsushima, to offer Joseon the ultimatum of submitting to Japan and participating in the conquest of China, or war with Japan.However, as Tsushima enjoyed a special trading position as the single checkpoint to Korea for all Japanese ships and had permission from Korea to trade with as many as 50 of its own vessels,[41] the Sō family delayed the talks for nearly two years.[40] Even when Hideyoshi renewed his order, Sō Yoshitoshi reduced the visit to the Yi Court to a campaign to better relations between the two countries. Near the end of the ambassadorial mission, Yoshitoshi presented King Seonjo a brace of peafowl and matchlock guns - the first advanced fire-arms to come to Korea.[42] Yu Seong-ryong, a high-ranking scholar official, suggested that the military put the arquebus into production and use, but the Yi Court failed to cooperate.[43] This lack of interest and underestimation of the power of the arquebus eventually led to the decimation of the Korean army early in the war.

On April 1590, the Korean ambassadors including Hwang Yun-gil, Kim Saung-il and others[44] left for Kyoto, where they waited for two months while Hideyoshi was finishing his campaign against the Odawara and the Hōjō clans.[45] Upon his return, they exchanged ceremonial gifts with and delivered King Seonjo's letter to Hideyoshi.[45] As Hideyoshi assumed that the Koreans had come to pay homage as a tributary to Japan, the ambassadors were not given the formal treatment that was due in handling diplomatic matters; at last, the Korean ambassadors asked that Hideyoshi write a reply to the Korean king, for which they waited 20 days at the port of Sakai.[46] The letter, redrafted as requested by the ambassadors on the ground that it was too discourteous, invited Korea to submit to Japan and join the war against China.[42] Upon the ambassadors' return, the Yi Court held serious discussions concerning Japan's invitation;[47] the ambassadors reported to the Yi Court conflicting estimates of Japanese military strength and intentions, all of which were lost in the quarrels of competing political factions and ranks. Some, including King Seonjo, argued that Ming should be informed about the dealings with Japan, as failure to do so could make Ming suspect Korea's allegiance, but the Yi Court finally concluded to wait further until the appropriate course of action became definite.[48]

Hideyoshi initiated his diplomacy with Korea under the impression that Korea was a vassal of Tsushima Island, which the Koreans considered theirs; the Yi Court approached Japan as a country inferior to Korea accordingly within the Chinese tributary system, and it expected Hideyoshi's invasions to be no better than the common Wako pirate raids.[49] The Yi Court handed to Gensho and Tairano, Hideyoshi's third embassy, King Seonjo's letter rebuking Hideyoshi for challenging the Chinese tributary system; Hideyoshi replied with a disrespectful letter, but, since it was not presented in person as expected by custom, the Yi Court ignored it.[50] After the denial of his second request, Hideyoshi launched his armies against Korea in 1592. There were internal oppositions to the invasion within Japan's government; among them, Tokugawa Ieyasu, Konishi Yukinaga and Sō Yoshitoshi who tried to arbitrate between Hideyoshi and the Joseon court.[citation needed]

Military Capabilities

The two major security threats to Korea and China at the time were the Jurchens, who raided along the northern borders, and the wakō (Japanese pirates), who pillaged the coastal villages and trade ships.[51][52] In response to the Jurchens, the Koreans constructed a thorough defense line of fortresses along the Tumen River; in response to the Japanese, the Koreans developed a powerful navy and even took control of the island of Tsushima.[53] This defensive environment of relative peace pushed the Koreans to depend on the heavy artillery of fortresses and warships. With the introduction of gunpowder during the Goryeo Dynasty, Korea developed advanced cannons, which were used with great effect at sea. China was the main source of new military technologies in Asia, and excelled in both cannon manufacturing and shipbuilding.[54] Japan, on the other hand, had been in a state of civil war for over a century, so the military had come to favor the muskets adopted from Portugal over such other weapons. This strategic difference in weapons development and implementation contributed to the in-war Japanese dominance on land, and the Korean dominance at sea[55].

As Japan had been at war since the mid-15th century, Hideyoshi had half a million battle-hardened soldiers at his disposal[56] to form the most professional army in Asia.[57] While Japan's chaotic state had left the Koreans with a very low estimate of Japan as a military threat,[58] a new sense of unity among the different political factions in Japan, and the "Sword Hunt" in 1588, (the confiscation of all weapons from the peasant) indicated otherwise.[59] Along with the hunt came “The Separation Edict” in 1591, which effectively put an end to all Japanese wakō piracy by prohibiting the daimyōs from supporting the pirates within their fiefs.[59] Ironically enough, the Koreans believed that Hideyoshi’s invasion would be just an extension of the previous pirate raids that had been repelled before.[60] As for the military situation in Joseon, the Korean scholar official Yu Seong-ryong observed, "not one in a hundred [Korean generals] knew the methods of drilling soldiers":[61] rise in ranks depended far more on social connections than military knowledge.[62] Korean soldiers were disorganized, ill-trained and ill-equipped,[63] and they were used mostly in construction projects such as building castle walls.[64]

Problems with the Korean defense policies

There were several defects with the organization of the Korean military.[65] An example was a defense policy that local officers could not individually respond to a foreign invasion outside of their jurisdiction until a higher ranking general, appointed by the king's court, arrived with a newly mobilized army.[65] This arrangement was highly inefficient in that the nearby forces would remain stationary until the mobile border commander arrived on the scene and took control.[65] Secondly, as the appointed general often came from an outside region, he was likely to be unfamiliar with the natural environment, the available technology and manpower of the invaded region.[65] Finally, as a main army was never maintained, new and ill-trained recruits conscripted during war constituted a significant part of the army.[65] The Yi Court managed to carry out some reforms, but even they were problematic. For example, the military training center established in 1589 in the Gyeongsang province recruited mostly only too young or too old soldiers (as able men targeted by the policy had higher priorities such as farming and other economic activities), augmented by some adventure-seeking aristocrats and slaves buying their freedom.[65]

The dominant form of the Korean fortresses was the "Sanseong", or the mountain fortress,[66] which consisted of a stone wall that continued around a mountain in a serpentine fashion.[57] These walls were poorly designed with little use of towers and cross-fire positions (usually seen in European fortifications) and were mostly low in height.[57] It was a wartime policy for everyone to evacuate to one of these nearby fortresses and for those who failed to do so to be assumed as collaborators with the enemy; however, the policy never gained any effect because the fortresses were out of reach for most refugees.[57]

Troop strength

Hideyoshi mobilized his army at the Nagoya Castle on Kyūshū, newly built just for the purpose of housing the invasion forces and the reserves.[67] The first invasion consisted of nine divisions totaling 158,800 men, of which the last two of 21,500 were stationed as reserves in Tsushima and Iki respectively.[68]

On the other hand, Joseon maintained only a few military units and no field army, and its defense depended heavily on the mobilization of the citizen soldiers in case of emergency.[64] During the first invasion, Joseon deployed a total of 84,500 regular troops throughout, assisted by 22,000 irregular volunteers.[69] The Chinese aid during the war could not have made up for the difference in numbers since they never maintained more than 60,000 troops in Korea at any point of the war,[70] while the Japanese used a total of 500,000 troops throughout the entire war.[56]

As early as 1582, the renowned Korean scholar Lee Yul-gok recommended that the Yi Court implement a nationwide expansion of troops up to 100,000, including a conscription of slaves and sons of concubines, after the northern troops performed miserably against a Jurchen attack.[61] However, as Lee was of the Western Faction, the dominant and competing Eastern Faction (led by Yu Seong-ryong) rejected the proposal.[61] The same result applied to a 1588 proposal from a provincial governor to arm the twenty islands of the southern coast of the peninsula and a proposal in 1590 to fortify the islands around the port city of Busan.[61] Even when the Japanese invasion seemed increasingly likely and even when Yu Seong-ryong switched sides on this issue, counter arguments brought purely out of political competition neutralized any gains for those advocating for the expansion of the military.[61] By 1592, the Koreans were poorly undermanned in regards to troop strength.

Weapons

Since its introduction by the Portuguese traders on the island of Tanegashima in 1543,[71] the arquebus became widely used in Japan.[72] Both Korea and China had already been using firearms similar to the Portuguese arquebus, but were older models. These old firearms eventually fell into disuse in Korea and the focus for gunpowder weapons in Korea rested primarily in artillery and archery.[73] When the Japanese diplomats presented the Yi Court arquebuses as gifts, the Korean scholar official Yu Seong-ryong advocated for the use of the new weapon unsuccessfully and the Yi Court failed to realize the potency of the new weapon.[45]

The Japanese saw a very infrequent use of their katana (curved long sword),[74] and relied mostly on the muskets (in combination with their bows) instead.[75]

The Korean infantry was equipped with one or more of the following personal weapons: swords, spears, tridents and bow-and-arrows.[54] The Koreans used one of the most advanced bows in Asia[55] - the composite reflex bow that had different materials laminated together (composite, the application of different characteristics of the materials for specific designs) with an inward curve (reflex) for maximum effectiveness.

The Korean bow's maximum range was 500 yards, compared to the 350 yards for the Japanese bows.[76] However, training a soldier to effectively use the bow was long and arduous, unlike the arquebus. The Chinese infantry used a variety of weapons, as they had to deal with many different environments throughout their empire, including bows (mainly crossbows),[76] swords (also for its cavalry),[77][78] muskets, smoke bombs and hand grenades.[55]

In the early part of the war, the Japanese gained a significant advantage with its large concentration of guns, which had a greater range of 600 yards[74] and penetrating power than the arrows,[79] and which could be fired in concentrated volleys to make up for its lack of accuracy (at both close and long ranges; the bow and arrow, at long range). However, later into the war, the Koreans and Chinese adopted and increased the use of the Japanese muskets.[45][80] It has also been claimed that the Chinese developed bullet-proof suits for use during the second invasion.[81]

Korea actively deployed their cavalry divisions in action, however the outcome was highly negative. The mountainous environment in Korea, which lacked both the flat plains suitable for cavalry charges and the grass essential in feeding the horses, and the Japanese use of muskets at long range put cavalry units at a disadvantage.[78]

Korean cavalrymen were equipped with flails and spears (longer than the Japanese swords) for melee combat and bows and arrows for ranged engagement.[82] Most of the cavalry action for the Koreans took place in the Battle of Chungju at the beginning of the war where they were outnumbered and wiped out by the Japanese infantry.[82] The Japanese divisions included cavalry as well, sometimes equipped with guns designed smaller specifically for use on horseback (though most cavalry men would use the yari, the Japanese spear.).[74] The Japanese use of cavalry was reduced by their previous civil war experiences with the use of guns in concentrated volleys.[83]

Armor

While even the common foot soldier in Japan wore chainmail, silk and bamboo armor, Korean foot soldiers had almost no armor at all.[citation needed]

Korean foot soldiers simply wore a heavy leather black vest over their common white clothes and a strictly ceremonial felt hat that offered some protection.[citation needed] Other than this, only the elite soldiers stationed at Seoul (the capital) had armor. Korean captains and generals wore chainmail and scale armor, with shoulder, leg and chest plates. The Korean military believed that the soldiers did not need armor because emphasis was placed on ranged weapons and agility/maneuverability, instead of hand-to-hand combat.[citation needed]

Naval power

The navy was a branch of the military in which Korea excelled.[citation needed] Korea's lead in the artillery and shipbuilding technology gave their navies a tremendous advantage. With a history of dependence at sea and the need to fight Japanese pirates, the Korean navy was heavily developed throughout the Goryeo period and was highly advanced by the Chosun Dynasty. By the time of the Japanese invasion, Korea used the panokseon, which was the backbone of the Korean navy.

Especially with the complete lack of cannons on the Japanese ships in the first phase of the war,[54] the Korean fleets could bombard the Japanese ships while remaining outside of the retaliatory range of the Japanese muskets, arrows, and catapults.[54] Even when the Japanese attempted to add more cannons to their fleet,[84] their lightweight ship design prevented them from placing as many cannons or as heavy ones on board as the allies.[85]

There were fundamental design flaws with the Japanese ships: first of all, most of the Japanese ships were merchant ships modified for the transportation of troops;[54] (it should be also noted that fishing vessels made up much of the Korean navy)[86] second, the Japanese ships each contained a single square sail (effective only in favorable winds) while Korean ships could be powered by both sails and oars. Also, Japanese ships had V-shaped bottoms (also the Chinese ships as well) that were ideal for speed but were less maneuverable than the flat-bottomed panokseons; and fourth, the Japanese ships relied on nails to hold their planks together while the Korean panokseons used wooden pegs, and this difference added to the Korean advantage, because in water, nails corroded and loosened while wooden pegs expanded and strengthened the joints.

Also, the brilliance of Admiral Yi's leadership and strategic fighting helped him win all of his battles, negatively impacting the Japanese navies.[citation needed]

It should be noted that Hideyoshi tried but failed to hire two Portuguese galleons to join the invasion.[87]

First invasion (1592–1593)

The initial attacks

Busan and Tadaejin

On May 23, 1592, the First Division of 7,000 men led by Konishi Yukinaga[90] left Tsushima in the morning, and arrived at the port city of Busan in the evening.[91] The Korean naval intelligence had already detected the Japanese fleet, but Won Gyun, the Right Naval Commander of Gyeongsang, mistook the fleet as consisting of trading vessels on a mission.[92] A later report of the arrival of an additional 100 Japanese vessels raised his suspicions, but the general did nothing about it.[92] Sō Yoshitoshi landed alone on the Busan shore to ask the Koreans for a safe passage to China for the last time; the Koreans refused, and Sō Yoshitoshi besieged the city while Konishi Yukinaga attacked the nearby fort of Tadaejin the next morning.[91] Japanese accounts claim that the battles dealt the Koreans complete annihilation (one claims 8,500 deaths, and another, 30,000 heads), while a Korean account claims that the Japanese themselves took significant losses before sacking the city.[93]

Tongnae

On the morning of May 25, 1592, the First Division arrived at Dongnae eupseong. [93] The fight lasted twelve hours, killed 3,000, and resulted in a Japanese victory.[94] A popular legend describes the governor in charge of the fortress, Song Sang-hyeon. When Konishi Yukinaga again demanded, before the battle, that the Koreans allow the Japanese to travel through the peninsula, the governor replied, "It is easy for me to die, but difficult to let you pass."[94] Even when the Japanese troops during the battle neared his commanding post, Song remained seated with cool dignity.[94] And when a Japanese cut off Song's right arm holding his staff of command, Song picked up the staff with his left arm, which was then cut off; again Song picked it up, this time with his mouth, but was killed by a third blow.[94] The Japanese, impressed by Song's defiance, treated his body with proper burial ceremony.[94]

The occupation of the Gyeongsang Province

Katō Kiyomasa's Second Division landed in Busan on May 27, and Kuroda Nagamasa's Third Division, west of Nakdong, on May 28.[95] The Second Division took the abandoned city of Tongdo on May 28, and captured Kyongju on May 30.[95] The Third Division, upon landing, captured the nearby Kimhae castle by keeping the defenders under pressure with gunfire while building ramps up to the walls with bundles of crops.[96] By June 3, the Third Division captured Unsan, Changnyong, Hyonpung, and Songju.[96] Meanwhile, Konishi Yukinaga's First Division passed the Yangsan mountain fortress (captured on the night of the Battle of Dongnae, when its defenders fled when the Japanese scouting party's fired their arquebuses), and captured the Miryang castle on the afternoon of May 26.[97] The First Division secured the Chongdo fortress in the next few days, and destroyed the city of Daegu.[97] By June 3, the First Division crossed the Nakdong River, and stopped at the Sonsan mountain.[97]

Joseon response

Upon receiving the news of the Japanese attacks, the Joseon government appointed General Yi Il as the mobile border commander, as was the established policy.[98] General Yi headed to Myongyong near the beginning of the strategically important Choryong pass to gather troops, but he had to travel further south to meet the troops assembled at the city of Daegu.[97] There, General Yi moved all troops back to Sangju, except for the survivors of the Battle of Dongnae who were to be stationed as a rearguard at the Choryong pass.[97]

Battle of Sangju

On April 25,[99] General Yi deployed a force of less than 1,000 men on two small hills to face the nearing First Division.[100] Assuming that rising smoke was from the burning of buildings by a nearby Japanese force, General Yi sent an officer to scout horseback; however, as he neared a bridge, the officer was ambushed Japanese musket fire from below the bridge, and beheaded.[100] The Korean troops, watching him fall were greatly demoralized.[100] Soon the Japanese began the battle with their arquebuses; the Koreans replied with their arrows, which fell short of their targets.[100] The Japanese forces, having been divided into three, attacked the Korean lines from both the front and the two flanks; the battle ended with General Yi Il’s retreat and 700 Korean casualties.[100]

Battle of Chungju

General Yi Il then planned to use the Choryong pass, the only path through the western end of the Sobaek mountain range, to check the Japanese advance.[100] However, another commander, Sin Rip, appointed by the Joseon government had arrived in the area with a cavalry division, and moved 8,000 combined troops to the Chungju fortress, located above the Choryong pass.[101] General Sin Rip then wanted to fight a battle on an open field, which he felt ideal for the deployment of his cavalry unit, and placed his units on the open fields of Tangeumdae.[101] As the general feared that, since the cavalry consisted mostly of new recruits, his troops would flee in battle easily,[102] he felt the need to trap his forces in the triangular area formed by the convergence of the Talchon and Han rivers in the shape of a “Y”.[101] However, the field was dotted with flooded rice paddies, and was not suitable for cavalry action.[101]

On June 5, 1592 the First Division of 18,000 men[102] led by Konishi Yukinaga left Sangju, and reached an abandoned fortress at Mungyong by night.[103] The next day, the First Division arrived at Tangumdae in the early afternoon, where they faced the Korean cavalry unit at the Battle of Chungju. Konishi divided his forces into three, and attacked with arquebuses from both flanks and the front.[103] The Korean arrows fell short of the Japanese troops, which were outside their range, and General Sin led two charges that failed against the Japanese lines. General Sin then killed himself in the river, and the Koreans that tried to escape by the river either drowned, or were decapitated by the pursuing Japanese.[103]

Capture of Hanyang (Seoul)

The Second Division led by Katō Kiyomasa arrived at Chungju, with the Third Division not far behind.[104] There, Katō expressed his anger against Konishi for not waiting at Busan as planned, and attempting to take all of the glory for himself; then Nabeshima Naoshige proposed a compromise of dividing the Japanese troops into two separate groups to follow two different routes to Hanseong (the capital and the present-day Seoul), and allowing Katō Kiyomasa to choose the route that the Second Division would take to reach Seoul.[104] The two divisions began the race to capture Hanseong on June 8, and Katō took the shorter route across the Han River while Konishi went further upstream where smaller waters posed a lesser barrier.[104] Konishi arrived at Hanseong first on June 10 while the Second Division was halted at the river with no boats to with which to cross.[104] The First Division found the castle undefended with its gates tightly locked, as King Seonjo had fled the day before.[105] The Japanese broke into a small floodgate, located in the castle wall, and opened the capital city's gate from within.[105] Katō’s Second Division arrived at the capital the next day (having taking the same route as the First Division), and the Third and Fourth Divisions the day after.[105] Meanwhile, the Fifth, Sixth, Seventh, and Eighth Divisions had landed on Busan, with the Ninth Division kept in reserve on the island of Iki.[105]

Parts of Hanseong had already been looted, burnt (i.e. bureaus holding the slave records and the weapons), and abandoned by its inhabitants.[105] General Kim Myong-won, in charge of the defenses along the Han River, had retreated.[106] The King’s subjects stole the animals in the royal stables and fled before him, leaving the King to rely on farm animals.[106] In every village, the King’s party was met by inhabitants, lined up by the road, grieving that their King was abandoning them, and neglecting their duty of paying homage.[106] Parts of the southern shore of the Imjin River was burnt to deprive the Japanese troops of materials with which to make their crossing, and General Kim Myong-won deployed 12,000 troops at five points along the river.[106]

Japanese campaigns in the north

The crossing of the Imjin River

While the First Division rested in Hanseong, the Second Division began heading north, only to be delayed by the Imjin River for two weeks.[106] The Japanese sent a familiar message to the Koreans on the other shore requesting them to open way to China, but the Koreans rejected this.[106] Then the Japanese commanders withdrew their main forces to the safety of the Paju fortress; the Koreans saw this as a retreat, and launched an attack at dawn against the remaining Japanese troops on the southern shore of the Imjin River.[106] The main Japanese body retaliated against the isolated Korean troops, and acquired their boats; at this, the Korean General Kim Myong-won retreated with his forces to the Kaesong fortress.[107]

The distribution of the Japanese forces in 1592

With the Kaesong castle having been sacked shortly after General Kim Myong-won retreated to Pyeongyang,[107] the Japanese troops divided their objectives thusly: the First Division would pursue the Korean king in Pyongan Province in the north (where Pyongyang is located); the Second Division would attack Hamgyong Province in the northeastern part of Korea; the Sixth Division would attack Jeolla Province at the southwestern tip of the peninsula; the Fourth Division would secure Gangwon Province in the midwestern part of the peninsula; and the Third, Fifth, Seventh, and Eighth Divisions would stabilize the following provinces respectively: Hwanghae Province (below Pyongan Province), Chungchon Province (below Kyonggi Province); Gyeongsang Province (in the southeast where the Japanese first had landed); and Gyeonggi Province (where the capital city is located).[108]

Capture of Pyeongyang

The First Division under Konishi Yukinaga proceeded northward, and sacked Pyongsan, Sohung, Pungsan, Hwangju, and Chunghwa on the way.[109] At Chunghwa, the Third Division under Kuroda Nagamasa joined the First, and continued to the city of Pyeongyang located behind the Taedong River.[109] 10,000 Korean troops guarded the city against 30,000 Japanese [110] under various commanders including the Generals Yi Il and Kim Myong-won, and their defense preparations had assured that no boats were available for Japanese use.[109]

On the night of July 22, 1592, the Koreans silently crossed the river and launched a successful surprise attack against the Japanese encampment.[109] However, this stirred up the rest of the Japanese army, which attacked the rear of the Korean positions and destroyed the reinforcements crossing the river.[111] Then the rest of the Korean troops retreated back to Pyeongyang, and the Japanese troops gave up their pursuit of the Koreans to observe the way the Koreans crossed the river.[111]

The next day, using what they had learned from observing the retreating Korean troops, the Japanese began sending troops to the other shore over the shallow points in the river, in a systematic manner, and at this the Koreans abandoned the city over night.[112] On July 24, the First and Third Divisions entered the deserted city of Pyeongyang.[112]

Campaigns in the Gangwon Province

The Fourth Division under the command of Mōri Yoshinari set out eastward from the capital city of Hanseong in July, and captured the fortresses down the eastern coast from Anbyon to Samchok.[112] The division then turned inward to capture Chongson, Yongwol, and Pyongchang, and settled down at the provincial capital of Wonju.[112] There Mōri Yoshinari established a civil administration, systematized social ranks according to the Japanese model, and conducted land surveys.[112] Shimazu Yoshihiro, one of the generals in the Fourth Division, arrived at Gangwon late, due to the Umekita Rebellion, and finished the campaign by securing Chunchon.[113]

Campaigns in the Hamgyong Province and Manchuria

Katō Kiyomasa leading the Second Division of more than 20,000 men, crossed the peninsula to Anbyon with a ten day march, and swept north along the eastern coast.[113] Among the castles captured was Hamhung, the provincial capital of the Hamgyong Province, and here a part of the Second Division was allocated for defense and civil administration.[114]

The rest of the division of 10,000 men[110] continued north, and fought a battle on August 23 against the southern and northern Hamgyong armies under the commands of Yi Yong and Han Kuk-ham at Songjin (present-day Kimchaek).[114] A Korean cavalry division took advantage of the open field at Songjin, and pushed the Japanese forces into a grain storehouse.[114] There the Japanese barricaded themselves with bales of rice, and successfully repelled a formation charge from the Korean forces with their arquebuses.[114] While the Koreans planned to renew the battle in the morning, Katō Kiyomasa ambushed them at night; the Second Division completely surrounded the Korean forces with the exception of an opening leading to a swamp.[114] Here, those that fled were trapped and slaughtered.[114]

Koreans who fled gave alarms to the other garrisons, allowing the Japanese troops easily to capture Kilchu, Myongchon, and Kyongson.[114] The Second Division then turned inland through Puryong toward Hoeryong where two Korean princes had taken refuge.[114] On August 30, 1592, the Second Division entered into Hoeryong where Katō Kiyomasa received the Korean princes and the provincial governor Yu Yong-rip, these having already been captured by the local inhabitants.[114] Shortly afterward, a Korean warrior band handed over the head of an anonymous Korean general, and the General Han Kuk-ham tied up in ropes.[114]

Katō Kiyomasa then decided to attack a nearby Jurchen castle across the Tumen River in Manchuria to test his troops against the “barbarians”, as the Koreans called the Jurchens (“oranke” in Korean and “orangai” in Japanese – the Japanese derived both the word and the concept of the Jurchens as barbarians from the Koreans).[115] The Koreans with 3,000 men at Hamgyong joined in (with Kato’s army of 8,000), as the Jurchens periodically raided them across the border.[115] Soon the combined force sacked the castle, and camped near the border; after the Koreans left for home, the Japanese troops suffered a retaliatory assault from the Jurchens.[115] Despite having the advantage, Katō Kiyomasa retreated with his forces to avoid heavy losses.[115]

The Second Division continued east, capturing the fortresses of Chongsong, Onsong, Kyongwon, and Kyonghung, and finally arrived at Sosupo on the estuary of the Tumen River.[115] There the Japanese rested on the beach, and watched a nearby volcanic island rising on the horizon that they mistook as Mount Fuji.[115] After the tour, the Japanese continued their previous efforts to bureaucratize and administrate the province, and allowed several garrisons to be handled by the Koreans themselves.[116]

The naval battles of Admiral Yi

Having secured Pyeongyang, the Japanese planned to cross the Yalu River into Jurchen territory, and use the waters west of the Korean peninsula to supply the invasion.[117] However, Yi Sun-sin, who held the post of the Left Naval Commander (equivalent of "Admiral” in English) of the Jeolla Province (which covers the western waters of Korea), successfully destroyed the Japanese ships transporting troops and supplies.[117] Thus the Japanese, now lacking enough arms and troops to carry on the invasion of the Jurchens, changed the objective of the war to the occupation of Korea.[117]

When the Japanese troops landed at the port of Busan, Bak (also spelled Park) Hong, the Left Naval Commander of the Gyeongsang Province, destroyed his entire fleet, his base, and all armaments and provisions, and fled.[92] Won Gyun, the Right Naval Commander, also destroyed and abandoned his own base, and fled to Konyang with only four ships.[92] Therefore, there was no Korean naval activity around the Gyeongsang Province, and the surviving two, out of the four total navies, were active only on the other (east) side of the peninsula.[92] Admiral Won later sent a message to Admiral Yi that he had fled to Konyang after being overwhelmed by the Japanese in a fight.[118] A messenger was sent by Admiral Yi to the nearby island of Namhae to give Yi’s order for war preparations, only to find it pillaged and abandoned by its own inhabitants.[118] As soldiers began to flee secretly, Admiral Yi ordered “to arrest the escapees" and had two of the fugitives brought back, beheaded them and had their heads exposed.[118]

Admiral Yi's battles greatly affected the war and put significant strain on Japanese supply routes.[119]

Battle of Okpo

Admiral Yi relied on a network of local fishermen and scouting boats to receive intelligence of the enemy movements.[119] On the dawn of June 13, 1592, Admiral Yi and Admiral Yi Ok-gi set sail with 24 Panokseons, 15 small warships, and 46 boats (i.e. fishing boats), and arrived at the waters of the Gyeongsang Province by sunset.[119] Next day, the Jeolla fleet sailed to the arranged location where Admiral Won was supposed to meet them, and met the admiral on June 15. The augmented flotilla of 91 ships[120] then began circumnavigating the Gojae Island, bound for the island of Gadok, but scouting vessels detected 50 Japanese vessels at the Okpo harbor.[119] Upon sighting the approaching Korean fleet, some of the Japanese who had been busying themselves with plundering got back to their ships, and began to flee.[119] At this, the Korean fleet encircled the Japanese ships and finished them with artillery bombardments.[121] The Koreans spotted five more Japanese vessels that night, and managed to destroy four.[121] The next day, the Koreans approached 13 Japanese ships at Chokjinpo as reported by the intelligence.[121] In the same manner as the previous success at Okpo, the Korean fleet destroyed 11 Japanese ships – completing the Battle of Okpo without a loss of a single ship.[121]

Battle of Sacheon and the Turtle Ship

About three weeks after the Battle of Okpo[122], Admirals Yi and Won sailed with a total of 26 ships (23 under Admiral Yi) toward the Bay of Sacheon upon receiving an intelligence report of the Japanese presence.[123] Admiral Yi had left behind his fishing vessels that used to make up most of his fleet in favor of his newly completed Turtle ship.[122]

The turtle ship was a vessel of a Panokseon design with the removal of the elevated command post, the modification of the gunwales into curved walls, and the addition of a roof covered in iron spikes (and hexagonal iron plates, which is disputed).[124] Its walls contained a total of 36 cannon ports, and also openings, above the cannons, through which the ship’s crew members could look out and fire their personal arms.[123] This design also prevented the outsiders from boarding the ship and aiming at the personnel inside.[124] The ship was the fastest existing warship in the East Asian theater, as it was powered by two sails and 80 oarsmen taking turns to handle the ship’s 16 oars.[86] No more than six Turtle Ships served throughout the entire war, and their primary role was to cut deep into the enemy lines, cause havoc with its cannons, and destroy the enemy flag ship.[86]

On July 8, 1592, the fleet arrived at the Bay of Sacheon, where the outgoing tide prevented the Korean fleet from entering.[122] Therefore, Admiral Yi ordered the fleet to feign withdrawal, which the Japanese commander observed from his tent on a rock.[124] Then the Japanese hurriedly embarked their 12 ships and pursued the Korean fleet.[122] The Korean navy counterattacked, with the Turtle Ship in the front, and successfully destroyed all 12 ships.[122] Admiral Yi was shot by a bullet in his left shoulder, but survived.[122]

Battle of Dangpo

On July 10, 1592, the Korean fleet again found and destroyed 21 Japanese ships, which were anchored at Dangpo while the Japanese raided a coastal town.[125]

Battle of Danghangpo

Admiral Yi Ok-gi with his fleet joined Admirals Yi Sun-sin and Won Gyun, and participated in a search for enemy vessels in the Gyonsang waters.[125] On July 13, the generals received intelligence that a group of Japanese ships including those that escaped from the Battle of Dangpo was resting in the Bay of Danghangpo.[125] Having traveled through a narrow gulf, the Koreans sighted a total of 26 enemy vessels in the bay.[125] The turtle ship was used to penetrate the enemy formation and rammed the flagship, while the rest of the Korean fleet held back.[126] Then Admiral Yi ordered a fake retreat, as the Japanese could escape to land while in the bay.[126] When the Japanese pursued the Koreans far enough, the Korean fleet turned and surrounded the Japanese fleet, with the Turtle Ship again ramming against the enemy flag ship. The Japanese were unable to counter the Korean cannons. Only 1 Japanese ship managed to escape from this route, and that too was caught and destroyed by a Korean ship the next morning.

Battle of Yulpo

On July 15, the Korean fleet was sailing east to return to the island of Gadok, and successfully intercepted and destroyed seven Japanese ships coming out from the Yulpo harbor.[126]

Battle of Hansando

In response to the Korean navy's success, Toyotomi Hideyoshi recalled three admirals from land-based activities: Wakizaka Yasuharu, Kato Yoshiaki, and Kuki Yoshitaka.[126] They were the only ones with naval responsibilities in the entirety of the Japanese invasion forces.[126] However, the admirals arrived in Busan nine days before Hideyoshi's order was actually issued, and assembled a squadron to counter the Korean navy.[126] Eventually Admiral Wakizaka completed his preparations, and his eagerness to win military honor pushed him to launch an attack against the Koreans without waiting for the other admirals to finish.[126]

The combined Korean navy of 70 ships[127] under the commands of Admirals Yi Sun-sin and Yi Ok-gi was carrying out a search-and-destroy operation because the Japanese troops on land were advancing into the Jeolla Province.[126] The Jeolla Province was the only Korean territory to be untouched by a major military action, and served as home for the three admirals and the only active Korean naval force.[126] The admirals considered it best to destroy naval support for the Japanese to reduce the effectiveness of the enemy ground troops.[126]

On August 13, 1592, the Korean fleet sailing from the Miruk Island at Tangpo received local intelligence that a large Japanese fleet was nearby.[126] The following morning, the Korean fleet spotted the Japanese fleet of 82 vessels anchored in the straits of Gyeonnaeryang.[126] Because of the narrowness of the strait and the hazard posed by the underwater rocks, Admiral Yi sent six ships to lure out 63 Japanese vessels into the wider sea,[127] and the Japanese fleet followed.[126] There the Japanese fleet was surrounded by the Korean fleet in a semicircular formation called “crane wing” by Admiral Yi.[126] With at least three turtle ships (two of which were newly-completed) spearheading the clash against the Japanese fleet, the Korean vessels fired volleys of cannonballs into the Japanese formation.[126] Then the Korean ships engaged in a free-for-all battle with the Japanese ships, maintaining enough distance to prevent the Japanese from boarding; Admiral Yi permitted melee combats only against severely damaged Japanese ships.[126] The battle ended in a Korean victory, with Japanese losses of 59 ships – 47 destroyed and 12 captured.[128] Several Korean prisoners of war were rescued by the Korean soldiers throughout the fight. Admiral Wakisaka escaped due to the speed of his flag ship.[128] When the news of the defeat at the Battle of Hansando reached Toyotomi Hideyoshi, he ordered that the Japanese invasion forces cease all naval operations.[126]

Battle of Angolpo

On August 16, 1592, Yi Sun-sin led their fleet to the harbor of Angolpo where 42 Japanese vessels were docked.[126] When Admiral Yi tried to fake a retreat, the Japanese ships did not follow; in response, Admiral Yi ordered the Korean ships to take turns bombarding the Japanese vessels.[126] In fear that the Japanese troops would take revenge for their losses against the local inhabitants, Admiral Yi ordered the Korean ships to cease fire against the few remaining enemy vessels.[126]

Korean Militias

From the beginning of the war, the Koreans organized militias called the "Righteous Army" (의병) to resist the Japanese invasion.[129] These fighting bands were raised throughout the country, and participated in battles, guerilla raids, sieges, and the transportation and construction of wartime necessities.[130]

There were three main types of Korean militias during the war: first, the surviving and leaderless Korean regular soldiers; second, the “Righteous Armies” (Uibyong in Korean) consisting of patriotic yangbans (aristocrats) and commoners; and third, the Buddhist monks.[130]

During the first invasion, the Cholla Province remained the only untouched area on the Korean peninsula.[130] In addition to the successful patrols of the sea by Admiral Yi, volunteer activism pressured the Japanese troops to avoid the province for other priorities.[130]

Gwak Jae-u's Campaigns along the Nakdong River

Gwak Jae-u was a famous leader in the Korean militia movement, and it is widely accepted that he was the first to form a resistance group against the Japanese invaders.[131] He was a land-owner in the town of Uiryong situated by the Nam River in the Gyeongsang Province. As the Korean regulars abandoned the town[130] and an attack seemed imminent, Gwak organized fifty townsmen; however the Third Division went from Changwon straight toward Songju.[131] When Gwak used abandoned government stores to supply his army, the Gyeongsang Province Governor Kim Su branded Gwak's group as rebels, and ordered that it be disbanded.[131] When the general asked for help from other landowners, and sent a direct appeal to the King, the governor sent troops against Gwak, in spite of having enough troubles already with the Japanese.[131] However, an official from the capital city then arrived to raise troops in the province, and, since the official lived nearby and actually knew him, he saved Gwak from troubles with the governor.[131]

Gwak Jae-u deployed his troops in guerilla warfare under the cover of the tall reeds on the union of the Nakdong and the Nam Rivers.[131] This strategy prevented easy access for the Japanese troops to the Jeolla Province where Admiral Yi and his fleet were stationed.[131]

Battle of Uiryong/Chongjin

The Sixth Division under the command of Kobayakawa Takakage was in charge of conquering the Jeolla Province.[131] The Sixth Division marched to Songju through the established Japanese route (i.e. the Third Division, above), and cut left to Kumsan in Chungchong, which Kobayakawa secured as his starting base for his invasion of the province.[131]

Ankokuji Ekei, a former Buddhist monk made into a general due to his role in the negotiations between Mōri Terumoto and Toyotomi Hideyoshi, led the units of the Sixth Division charged with the invasion of the Jeolla Province. The units began their march to Uiryong at Changwon, and arrived at the Narm River.[131] Ankokuji’s scouts planted meters measuring the river’s depths so that the entire squadron could cross the river; over the night, the Korean militiamen moved the meters into the deeper parts of the river.[131] As the Japanese troops began to cross, Gwak’s militia ambushed them, and caused heavy losses for the Japanese.[131] In the end, to advance into the Jeolla Province, Ankokuji’s men had to try going north around the insecure grounds and within the security of the Japanese-garrisoned fortresses.[131] At Kaenyong, Ankokuji’s target was changed to Gochang, to be taken with the aid of Kobayakawa Takakage.[131] However, the entire Jeolla campaign was then abandoned when Kim Myon and his guerillas successfully ambushed Ankokuji’s troops by firing arrows from hidden positions within the mountains.[131]

The Jeolla coalition & the Battle of Yong-in

When the Japanese troops were advancing to Hanseong (present-day Seoul),Yi Kwang, the governor of the Jeolla Province, attempted to check the Japanese progress by launching his army toward the capital city.[132] Upon hearing the news that the capital had already been sacked, the governor withdrew his army.[132] However, as the army grew in size to 50,000 men with the accumulation of several volunteer forces, Yi Kwang and the irregular commanders reconsidered their aim to reclaim Hanseong, and led the combined forces north to Suwon, 26 miles (42 km) south of Hanseong.[133][132] On June 4, an advance guard of 1,900 men attempted to take the nearby fortress at Yong-in, but the 600 Japanese defenders under Admiral Wakizaka Yasuharu avoided engagement with the Koreans until June 5, when the main Japanese troops came to relieve the fortress.[134][132] The Japanese troops counterattacked successfully against the Jeolla coalition, forcing the Koreans to abandon arms and retreat.[132]

The First Geumsan Campaign

Around the time of General Kwak's mobilization of his volunteer army in the Gyeongsang Province, Go Gyung-myeong in Jeolla Province formed a volunteer force of 6,000 men.[132] Go then tried to combine his forces with another militia in the Chungchong Province, but upon crossing the provincial border he heard that Kobayakawa Takakage of the Sixth Division had launched an attack on Jeonju (the capital of Jeolla Province) from the mountain fortress at Geumsan. Go returned to his own territory. province.[132] Having joined forces with General Gwak Yong, Go then led his soldiers to Geumsan.[132] There, on July 10, the volunteer forces fought with a Japanese army retreating to Geumsan after a defeat at the Battle of Ichi two days earlier on July 8[135]

Battle of Haengju

The Japanese invasion into Jeolla province was broken down and pushed back by General Gwon Yul at the hills of Ichiryeong, where outnumbered Koreans fought overwhelming Japanese troops and gained victory. Gwon Yul quickly advanced northwards, re-taking Suwon and then swung south toward Haengju where he would wait for the Chinese reinforcements. After he got the message that the Koreans were annihilated at Byeokje, Gwon Yul decided to fortify Haengju.

Bolstered by the victory at Byeokje, Katō and his army of 30,000 men advanced to the south of Hanseong to attack Haengju Fortress, an impressive mountain fortress that overlooked the surrounding area. An army of a few thousand led by Gwon Yul was garrisoned at the fortress waiting for the Japanese. Katō believed his overwhelming army would destroy the Koreans and therefore ordered the Japanese soldiers to simply advance upon the steep slopes of Haengju with little planning. Gwon Yul answered the Japanese with fierce fire from the fortification using Hwachas, rocks, handguns, and bows. After nine massive assaults and 10,000 casualties, Katō burned his dead and finally pulled his troops back.

The Battle of Haengju was an important victory for the Koreans, as it greatly improved the morale of the Korean army. The battle is celebrated today as one of the three most decisive Korean victories; Battle of Haengju, Siege of Jinju (1592), and Battle of Hansando.

Today, the site of Haengju fortress has a memorial built to honor Gwon Yul.

Siege of Jinju

Jinju (진주) was a large castle that defended Jeolla Province. The Japanese commanders knew that control of Jinju would mean the fall of Jeolla. Therefore, a large army under Hosokawa Tadaoki gleefully approached Jinju. Jinju was defended by Kim Si-min (김시민), one of the better generals in Korea, commanding a Korean garrison of 3,000 men. Kim had recently acquired about 200 new arquebuses that were equal in strength to the Japanese guns. With the help of arquebuses, cannon, and mortars, Kim and the Koreans were able to drive back the Japanese from Jeolla Province. Hosokawa lost over 30,000 men. The battle at Jinju is considered one of the greatest victories of Korea because it prevented the Japanese from entering Jeolla.

In 1593, Jinju fell to the Japanese in a second attack.[136]

Intervention of Ming China

China sent land and naval forces to Korea in both the first and second invasions to assist in defeating the Japanese.[citation needed]

After the fall of Pyongyang, King Seonjo retreated to Uiju, a small city near the border of China. With the First and Second Divisions rapidly approaching, King Seonjo made another desperate retreat into China.[citation needed] At the Chinese court, King Seonjo informed the Ming Emperor of the Japanese invasion.

The Ming Dynasty Emperor Wanli and his advisers responded to King Seonjo's request for aid by sending an inadequately small force of 5,000 soldiers.[137] These troops provided almost no help whatsoever.[citation needed]

As a result, the Ming Emperor sent a large force in January 1593 under two generals, Song Yingchang and Li Rusong, the latter being of Korean/Jurchen ancestry. The salvage army had a prescribed strength of 100,000, made up of 42,000 from five northern military districts and a contingent of 3,000 soldiers proficient in the use of firearms from South China. The Ming army was also well armed with artillery pieces.[citation needed]

In January 1593, a large force of Chinese soldiers meet up outside of Pyongyang with a group of Korean militias. By King Seonjo's decree, Ming general Li Rusong was appointed the supreme commander of armies in Korea. Li then led the allied troops to victory in the bloody siege of Pyongyang and drove the Japanese into eastward retreat. Overconfident with his recent success, Li Rusong personally led a pursuit with 5,000 mounted troops, along with a small force of Koreans, but was ambushed near Pyokje by a large Japanese formation of nearly 40,000. Li escaped when relief force of 5,000 arrived. Japanese casualties (especially officers) were believed to be more than those of Chinese due to the better close fighting abilities of the Chinese elite Liaodong cavalry.[citation needed] However, Li became less aggressive since then due to the heavy losses suffered by his most reliable mounted troops in this battle.[citation needed]

In late February, Li ordered a raid into the Japanese rear and burned several hundred thousand koku[138] of military rice stores, forcing the Japanese invading armies to retreat from Seoul due to the prospect of food shortage.[citation needed]

These engagements ended the first phase of the war, and peace negotiations followed.[citation needed] Some Japanese soldiers abandoned the army and settled down in Korea.[citation needed] The Japanese evacuated Hanseong in May and retreated to fortifications around Busan. An uneasy truce was put in place which lasted about four years.[citation needed]

Negotiations and truce between China and Japan (1594–1596)

Under pressure from the Chinese army and local guerrillas, with food supplies cut off and his forces now reduced by nearly one third from desertion, disease and death, Konishi was compelled to sue for peace. General Li Rusong offered General Konishi a chance to negotiate an end to the hostilities. When negotiations got underway in the spring of 1593, China and Korea agreed to cease hostilities if the Japanese would withdraw from Korea altogether. General Konishi had no option but to accept the terms, but he would have a hard time convincing Hideyoshi that he had no other choice.

Hideyoshi proposed to China the division of Korea: the north as a self-governing Chinese satellite, and the south to remain in Japanese hands. The peace talks were mostly carried out by Konishi Yukinaga, who did most of the fighting against the Chinese. The offer was taken into consideration until Hideyoshi also demanded one of the Chinese princesses to be sent as his concubine. Then the offer was promptly rejected. These negotiations were kept secret from the Korean Royal Court, which had no say in them.

By May 18, 1593, all the Japanese soldiers had retreated back to Japan. In the summer of 1593, a Chinese delegation visited Japan and stayed at the court of Hideyoshi for more than a month. The Ming government withdrew most of its expeditionary force, but kept 16,000 men on the Korean peninsula to guard the truce.

An envoy from Hideyoshi reached Beijing in 1594. Most of the Japanese army had left Korea by the autumn of 1596; a small garrison nevertheless remained in Busan. Satisfied with the Japanese overtures, the imperial court in Beijing dispatched an embassy to allow Hideyoshi to have the title of "King of Japan" on condition of complete withdrawal of Japanese forces from Korea.

The Ming ambassador met Hideyoshi in October 1596 but there was a great deal of misunderstanding about the context of the meeting. Hideyoshi was enraged to learn that China insulted the Emperor of Japan by presuming to cancel the Emperor's divine right to the throne, offering to recognize Hideyoshi instead. To insult the Chinese, he demanded among other things, a royal marriage with the Wanli Emperor's daughter, the delivery of a Korean prince as hostage, and four of Korea's southern provinces.

Peace negotiations soon broke down and the war entered its second phase when Hideyoshi sent another invasion force. Early in 1597, both sides resumed hostilities.

Korean military reorganization

Proposal for military reforms

During the period between the First and Second invasions, the Korean government had a chance to examine the reasons why they had been easily overrun by the Japanese. Yu Seong-ryong, the Prime Minister, spoke out about the Korean disadvantage.

Yu pointed out that Korean castle defenses were extremely weak, a fact which he had already pointed out before the war. He noted how Korean castles had incomplete fortifications and walls that were too easy to scale. He also wanted cannons set up in the walls, since they were highly effective. Yu proposed building strong towers with gun turrets for cannons. Besides castles, Yu wanted to form a line of defenses in Korea. He proposed to create a series of all enveloping walls and forts, with Seoul in the center.[citation needed] In this kind of defense, the enemy would have to scale many walls in order to reach Seoul.

Yu also pointed out how efficient the Japanese army was, in that it took them only one month to reach Seoul, and how well trained they were. The organized military units the Japanese generals deployed were a large part of the Japanese success.[citation needed] Yu noted how the Japanese moved their units in complex maneuvers, often weakening the enemy with arquebuses, then attacking with melee weapons. Korean armies often moved forward as one body without any organization at all.[citation needed]

Military Training Agency

King Seonjo and the Korean court finally began to reform the military. In September 1593, the Military Training Agency was established. The agency carefully divided the army into units and companies. Within the companies were squads of archers, arquebusers, and edged-weapon users. The agency set up divisional units in each region of Korea and garrisoned battalions at castles. The agency, which originally had less than 80 members, soon grew to about 10,000.

One of the most important changes was that both upper class citizens and slaves were subject to the draft. All males had to enter military service be trained and familiarized with weapons.

Second invasion (1597–1598)

| Japanese second invasion wave[139] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Army of the Right | ||||

| Mori Hidemoto | 30,000 | |||

| Katō Kiyomasa | 10,000 | |||

| Kuroda Nagamasa | 5,000 | |||

| Nabeshima Naoshige | 12,000 | |||

| Ikeda Hideuji | 2,800 | |||

| Chosokabe Motochika | 3,000 | |||

| Nakagawa Hidenari | 2,500 | |||

| Total | 65,300 | |||

| Army of the Left | ||||

| Ukita Hideie | 10,000 | |||

| Konishi Yukinaga | 7,000 | |||

| Sō Yoshitoshi | 1,000 | |||

| Matsuura Shigenobu | 3,000 | |||

| Arima Harunobu | 2,000 | |||

| Omura Yoshiaki | 1,000 | |||

| Goto Sumiharu | 700 | |||

| Hachisuka Iemasa | 7,200 | |||

| Mōri Yoshinari | 2,000 | |||

| Ikoma Kazumasa | 2,700 | |||

| Shimazu Yoshihiro | 10,000 | |||

| Shimazu Tadatsune | 800 | |||

| Akizuki Tanenaga | 300 | |||

| Takahashi Mototane | 600 | |||

| Ito Suketaka | 500 | |||

| Sagara Yorifusa | 800 | |||

| Total | 49,600 | |||

| Naval Command | ||||

| Todo Takatora | 2,800 | |||

| Katō Yoshiaki | 2,400 | |||

| Wakizaka Yasuharu | 1,200 | |||

| Kurushima Michifusa | 600 | |||

| Mitaira Saemon | 200 | |||

| Total | 7,200 | |||

Hideyoshi was dissatisfied with the first campaign and decided to attack Korea again. One of the main differences between the first and second invasions was that conquering China was no longer a goal for the Japanese. Failing to gain a foothold during Katō Kiyomasa's Chinese campaign and the full retreat of the Japanese during the first invasion affected Japanese morale. Hideyoshi and his generals instead planned to conquer Korea.

Instead of the nine divisions during the earlier invasion, the armies invading Korea were divided into the Army of the Left and the Army of the Right, consisting of about 49,600 men and 30,000 respectively.

Soon after the Chinese ambassadors returned safely to China in 1597, Hideyoshi sent 200 ships with approximately 141,100 men[140] under the overall command of Kobayakawa Hideaki.[141] Japan's second force arrived unopposed on the southern coast of Gyeongsang Province in 1596. However, the Japanese found that Korea was both better equipped and ready to deal with an invasion this time.[142] In addition, upon hearing this news in China, the imperial court in Beijing appointed Yang Hao (楊鎬) as the supreme commander of an initial mobilization of 55,000 troops[140] from various (and sometimes remote) provinces across China, such as Sichuan, Zhejiang, Huguang, Fujian, and Guangdong.[143] A naval force of 21,000 was included in the effort.[144] Rei Huang, a Chinese historian, estimated that the combined strength of the Chinese army and navy at the height of the second campaign was around 75,000.[145] Korean forces totaled 30,000 with General Gwon Yul's army in Gong Mountain (공산; 公山) in Daegu, General Gwon Eung's (권응) troops in Gyeongju, Gwak Jae-u's soldiers in Changnyeong (창녕), Yi Bok-nam’s (이복남) army in Naju, and Yi Si-yun's troops in Chungpungnyeong.[140]

Initial offensive

Initially the Japanese found little success, being confined mainly to Gyeongsang Province and only managing numerous short-range attacks to keep the much larger Korean and Chinese forces off balance.[142] All throughout the second invasion Japan would mainly be on the defensive and locked in at Gyeongsang province.[142] The Japanese planned to attack Jeolla Province in the southwestern part of the peninsula and eventually occupy Jeonju, the provincial capital. Korean success in the Siege of Jinju in 1592 had saved this area from further devastation during the first invasion. Two Japanese armies, under Mōri Hidemoto and Ukita Hideie, began the assault in Busan and marched towards Jeonju, taking Sacheon and Changpyong along the way.

Siege of Namwon

Namwon was located 30 miles southeast of Jeonju. Correctly predicting a Japanese attack, a coalition force of 6,000 soldiers (including 3,000 Chinese and civilian volunteers) were readied to fight the approaching Japanese forces.[146] The Japanese laid siege to the walls of the fortress with ladders and siege towers.[147] The two sides exchanged volleys of arquebuses and bows. Eventually the Japanese forces scaled the walls and sacked the fortress. According to Japanese commander Okochi Hidemoto, author of the Chosen Ki, the Siege of Namwon resulted in 3,726 casualties[148] on the Korean and Chinese forces' side.[149] The entire Jeolla Province fell under Japanese control, but as the battle raged on the Japanese found themselves hemmed in on all sides in a retreat and again positioned in a defensive perimeter only around Gyeongsang Province.[142]

Battle of Hwangseoksan

Hwangseoksan Fortress consisted of extensive walls that circumscribed the Hwangseok mountain and garrisoned thousands of soldiers led by the general Jo Jong-do and Gwak Jun. When Katō Kiyomasa laid siege to the mountain with a large army, the Koreans lost morale and retreated with 350 casualties. Even with this incident the Japanese were still unable to break free from Gyeongsang Province and were reduced to holding a defensive position only, with constant attacks from the Chinese and Korean forces.[142]

Korean naval operations (1597–1598)

The Korean navy played a crucial part in the second invasion, as in the first. The Japanese advances were halted due to the lack of reinforcements and supplies as the naval victories of the Korean navy prevented the Japanese from accessing the south-western side of the Korean peninsula.[150] Also, during the second invasion, China sent a large number of Chinese ships to aid the Koreans. This made the Korean navy an even bigger threat to the Japanese, since they had to fight a larger enemy fleet.

Plot against Admiral Yi

The war at sea had a bad start when Won Gyun took Admiral Yi's place as commander.

Because Admiral Yi, the commander of the Korean navy, was so able in naval warfare, the Japanese plotted to demote him by making use of the laws that governed the Korean military. A Japanese double agent working for the Koreans falsely reported that Japanese General Katō Kiyomasa would be coming on a certain date with a great Japanese fleet in another attack on Korean shores, and insisted that Admiral Yi be sent to lay an ambush.[151]

Knowing that the area had sunken rocks detrimental to the ships, Admiral Yi refused, and he was demoted and jailed by King Seonjo for refusing orders. On top of this, Admiral Won Gyun accused Admiral Yi of drinking and idling. Won Gyun was quickly put in Admiral Yi's place.

Battle of Chilchonryang

After Won Gyun replaced Admiral Yi, Won Gyun gathered the entire Korean fleet, which now had more than 100 ships carefully accumulated by Admiral Yi, outside of Yosu to search for the Japanese. Without any previous preparations or planning, Won Gyun had his fleet sail towards Busan.

After one day, Won Gyun was informed of a large Japanese fleet near Busan. He decided to attack immediately, although captains complained of their exhausted soldiers.

At the Battle of Chilchonryang, Won Gyun was completely outmaneuvered by the Japanese in a surprise attack. His ships were overwhelmed by arquebus fire and the Japanese traditional boarding attacks. Eventually, the battle destroyed the entire Korean fleet. However, before the battle, Bae Soel, an officer, ran away with 13 Panokseons, the entire fighting force of the Korean navy for many months.

The Battle of Chilchonryang was Japan's only naval victory of the war. Won Gyun died after he struggled ashore and was subsequently killed by a Japanese garrison.

Battle of Myeongnyang

After the debacle in Chilcheollyang, King Seonjo immediately reinstated Admiral Yi. Admiral Yi quickly returned to Yeosu only to find his entire navy destroyed. Yi re-organized the navy, now reduced to 12 ships and 200 men from the previous battle.[152] Nonetheless, Admiral Yi's strategies did not waver, and on September 16, 1597, he led the small Korean fleet against a Japanese fleet of 300 war vessels[153] in the Myeongnyang Strait. The Battle of Myeongnyang resulted in a Korean victory with at least 133 Japanese vessels sunk, and the Japanese were forced to return to Busan,[154] under the orders of Mōri Hidemoto. Admiral Yi won back the control of the Korean shores. The Battle of Myeongnyang is considered Admiral Yi's greatest battle because of the disparity of numbers.

Siege of Ulsan

By late 1597, the Joseon and Ming allied forces achieved victory in Jiksan and pushed the Japanese further south. After the news of the loss at Myeongnyang, Katō Kiyomasa and his retreating army decided to destroy Gyeongju, the former capital of Unified Silla.

Eventually, Japanese forces sacked the city and many artifacts and temples were destroyed, most prominently, the Bulguksa, a Buddhist temple. However, Joseon and Ming allied forces repulsed the Japanese forces who retreated south to Ulsan,[155] a harbor that had been an important Japanese trading post a century before, and which Katō had chosen as a strategic stronghold.

Yet Admiral Yi's control of the areas over the Korea Strait permitted no supply ships to reach the western side of the Korean peninsula, into which many extensive tributaries merge. Without provisions and reinforcements, the Japanese forces had to remain in the coastal fortresses known as wajō that they still controlled. To gain advantage of the situation, the Chinese and Korean coalition forces attacked Ulsan. This siege was the first major offensive from the Chinese and Korean forces in the second phase of the war.

The effort of the Japanese garrison (about 7,000 men) of Ulsan was largely dedicated to its fortification in preparation for the expected attack. Katō Kiyomasa assigned command and defense of the base to Katō Yasumasa, Kuki Hirotaka, Asano Nagayoshi, and others before proceeding to Sosaengpo.[156] The Chinese Ming and Korean army first assault on January 29, 1598, caught the Japanese army unawares and still encamped, for the large part, outside Ulsan's unfinished walls.[157]

A total of around 36,000 troops with the help of singijeons and hwachas nearly succeeded in sacking the fortress, but reinforcements under the overall command of Mōri Hidemoto came across the river to aid the besieged fortress[158] and prolonged the hostilities. Later, the Japanese troops were running out of food and victory was imminent for the allied forces, but Japanese reinforcements arrived from the rear of the Chinese and Korean troops and forced them to a stalemate. After several losses, however, Japan's position in Korea had significantly weakened.

Battle of Sacheon