Augustine of Hippo: Difference between revisions

Undid revision 270260919 by 74.94.205.105 (talk)rv vandalism |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 219: | Line 219: | ||

=== Statements on Jews === |

=== Statements on Jews === |

||

Against certain Christian movements rejecting the use of Hebrew Scriptures, Augustine countered that God had chosen the Jews as a |

Against certain Christian movements rejecting the use of Hebrew Scriptures, Augustine countered that God had chosen the Jews as a his people, though he also considered the scattering of Jews by the Roman empire to be a fulfillment of prophecy.<ref>[[Diarmaid MacCulloch]]. ''The Reformation'' (Penguin Group, 2005) p8.</ref><ref>''City of God'', book 18, chapter 46.</ref> |

||

Augustine also quotes part of the same prophecy that says "Slay them not, lest they should at last forget Thy law" (Psalm 59:11). Augustine argued that God had allowed the Jews to survive this dispersion as a warning to Christians, thus they were to be permitted to dwell in Christian lands. Augustine further argued that the Jews would be converted at the end of time.<ref>J. Edwards, ''The Spanish Inquisition'' (Stroud, 1999), pp33-5.</ref> |

Augustine also quotes part of the same prophecy that says "Slay them not, lest they should at last forget Thy law" (Psalm 59:11). Augustine argued that God had allowed the Jews to survive this dispersion as a warning to Christians, thus they were to be permitted to dwell in Christian lands. Augustine further argued that the Jews would be converted at the end of time.<ref>J. Edwards, ''The Spanish Inquisition'' (Stroud, 1999), pp33-5.</ref> |

||

Revision as of 09:36, 16 February 2009

Augustine of Hippo (Saint Augustine) | |

|---|---|

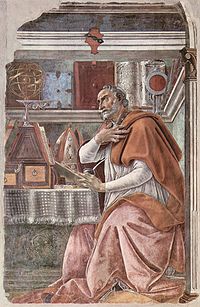

Augustine as depicted by Sandro Botticelli, c. 1480 | |

| Bishop, Confessor, Doctor of the Church | |

| Born | November 13, 354 Thagaste, Numidia (now Souk Ahras, Algeria) |

| Died | August 28, 430 (aged 75) Hippo Regius, Numidia (now modern-day Annaba, Algeria) |

| Venerated in | Roman Catholic Church Eastern Orthodox Churches Oriental Orthodoxy Anglican Communion Lutheranism |

| Major shrine | San Pietro in Ciel d'Oro, Pavia, Italy |

| Feast | August 28 (Western Christianity) June 15 (Eastern Christianity) |

| Attributes | child; dove; pen; shell, pierced heart |

| Patronage | brewers; printers; theologians Bridgeport, Connecticut; Cagayan de Oro, Philippines; Ida, Philippines; Kalamazoo Michigan; Saint Augustine, Florida; Superior, Wisconsin; Tucson, Arizona; Avilés, Spain |

Augustine of Hippo (/ɔ:ˈɡʌstɪn/ or //ˈɔɡəsti:n//)[1] (Template:Lang-la;[2]) (November 13, 354 – August 28, 430), Bishop of Hippo Regius, also known as St. Augustine or St. Austin [3], was a philosopher and theologian. Augustine, a Latin church father, is one of the most important figures in the development of Western Christianity. Augustine was heavily influenced by the Neo-Platonism of Plotinus.[4] He framed the concepts of original sin and just war. When the Roman Empire in the West was starting to disintegrate, Augustine developed the concept of the Church as a spiritual City of God (in a book of the same name) distinct from the material City of Man.[5] His thought profoundly influenced the medieval worldview. Augustine's City of God was closely identified with the church, and was the community which worshiped God.[6]

Augustine was born in the city of Thagaste[7], the present day Souk Ahras, Algeria, to a Catholic mother named Monica. He was educated in North Africa and resisted his mother's pleas to become Christian. Living as a pagan intellectual, he took a concubine and became a Manichean. Later he converted to the Catholic Church, became a bishop, and opposed heresies, such as the belief that people can have the ability to choose to be good to such a degree as to merit salvation without divine aid (Pelagianism). His works—including The Confessions, which is often called the first Western autobiography—are still read around the world.

In Roman Catholic Church and the Anglican Communion, he is a saint and pre-eminent Doctor of the Church, and the patron of the Augustinian religious order; his memorial is celebrated 28 August. Many Protestants, especially Calvinists, consider him to be one of the theological fathers of Reformation teaching on salvation and divine grace. In the Eastern Orthodox Church he is blessed, and his feast day is celebrated on 15 June, though a minority are of the opinion that he is a heretic, primarily because of his statements concerning what became known as the filioque clause.[8] Among the Orthodox he is called Blessed Augustine, or St. Augustine the Blessed.[9]

Life

Early childhood

Augustine was of Berber descent.[10] He was born in A.D. 354 in Thagaste (present-day Souk Ahras, Algeria), a provincial Roman city in North Africa.[11] At the age of 11, Augustine was sent to school at Madaurus, a small Numidian city about 19 miles south of Thagaste noted for its pagan climate. There he became familiar with Latin literature, as well as pagan beliefs and practices.[12] In 369 and 370, he remained at home. During this period he read Cicero's dialogue Hortensius (now lost), which he described as leaving a lasting impression on him and sparking his interest in philosophy. [11]

Studying at Carthage

At age 17, through the generosity of a fellow citizen Romanianus,[11] he went to Carthage to continue his education in rhetoric. His mother, Monica,[13] was a Berber and a devout Catholic, and his father, Patricius, a pagan. Although raised as a Catholic, Augustine left the Church to follow the Manichaean religion, much to the despair of his mother. As a youth Augustine lived a hedonistic lifestyle for a time and, in Carthage, he developed a relationship with a woman who would be his concubine for over thirteen years and who gave birth to his son, Adeodatus.[14] (Augustine does not name the woman. "Floria Aemilia" is the name supplied by novelist Jostein Gaarder in That Same Flower.)

Rhetoric

During the years 373 and 374, Augustine taught grammar at Tagaste. The following year, he moved to Carthage to conduct a school of rhetoric, and would remain there for the next nine years.[11] Disturbed by the unruly behaviour of the students in Carthage, in 383 he moved to establish a school in Rome, where he believed the best and brightest rhetoricians practiced. However, Augustine was disappointed with the Roman schools, which he found apathetic. Once the time came for his students to pay their fees they simply fled. Manichaean friends introduced him to the prefect of the City of Rome, Symmachus, who had been asked to provide a professor of rhetoric for the imperial court at Milan.

The young provincial won the job and headed north to take up his position in late 384. At age thirty, Augustine had won the most visible academic chair in the Latin world, at a time when such posts gave ready access to political careers. During this time, Augustine was a devout follower of Manichaeism.

While he was in Milan, Augustine's life changed. While still at Carthage, he had begun to move away from Manichaeism, in part because of a disappointing meeting with a key exponent of Manichaean theology. In Rome, he is reported to have completely turned away from Manichaeanism, and instead embraced the skepticism of the New Academy movement. At Milan, his mother Monica pressured him to become a Catholic. Augustine's own studies in Neoplatonism were also leading him in this direction, and his friend Simplicianus urged him that way as well.[11] But it was the bishop of Milan, Ambrose, who had most influence over Augustine. Ambrose was a master of rhetoric like Augustine himself, but older and more experienced.

Augustine's mother had followed him to Milan and he allowed her to arrange a society marriage, for which he abandoned his concubine. It is believed that Augustine truly loved the woman he had lived with for so long. In his "Confessions," he expressed how deeply he was hurt by ending this relationship, and also admitted that the experience eventually produced a decreased sensitivity to pain over time. However, he had to wait two years until his fiancee came of age, so despite the grief he felt over leaving "The One" as he called her, he soon took another concubine. Augustine eventually broke off his engagement to his eleven-year-old fiancee, but never renewed his relationship with "The One" and soon left his second concubine. It was during this period that he uttered his famous prayer, "Grant me chastity and continence, but not yet" (da mihi castitatem et continentiam, sed noli modo).[15]

Conversion to Christianity

In the summer of 386, after having read an account of the life of Saint Anthony of the Desert which greatly inspired him, Augustine underwent a profound personal crisis and decided to convert to Catholic Christianity, abandon his career in rhetoric, quit his teaching position in Milan, give up any ideas of marriage, and devote himself entirely to serving God and to the practices of priesthood, which included celibacy. Key to this conversion was the voice of an unseen child he heard while in his garden in Milan telling him in a sing-song voice, tolle, lege ("take up and read"). He grabbed the nearest text to him, which was Paul's Epistle to the Romans, and opened it at random at 13:13-14, which read: "Let us walk honestly, as in the day; not in rioting and drunkenness, not in chambering and wantonness, not in strife and envying; but put on the Lord Jesus Christ, and make no provision for the flesh, to gratify its desires."[16] He would detail his spiritual journey in his famous Confessions, which became a classic of both Christian theology and world literature. Ambrose baptized Augustine, along with his son, Adeodatus, on Easter Vigil in 387 in Milan, and soon thereafter in 388 he returned to Africa.[11] On his way back to Africa his mother died, as did his son soon after, leaving him alone in the world without family.

Priesthood

Upon his return to north Africa he sold his patrimony and gave the money to the poor. The only thing he kept was the family house, which he converted into a monastic foundation for himself and a group of friends.[11] In 391 he was ordained a priest in Hippo Regius (now Annaba, in Algeria). He became a famous preacher (more than 350 preserved sermons are believed to be authentic), and was noted for combating the Manichaean religion, to which he had formerly adhered.

In 396 he was made coadjutor bishop of Hippo (assistant with the right of succession on the death of the current bishop), and became full bishop shortly thereafter. He remained in this position at Hippo until his death in 430. Augustine worked tirelessly in trying to convince the people of Hippo, who were a diverse racial and religious group, to convert to the Catholic faith. He left his monastery, but continued to lead a monastic life in the episcopal residence. He left a rule (Latin, regula) for his monastery that has led him to be designated the "patron saint of regular clergy", that is, clergy who live by a monastic rule.

Much of Augustine's later life was recorded by his friend Possidius, bishop of Calama, in his Sancti Augustini Vita. Possidius admired Augustine as a man of powerful intellect and a stirring orator who took every opportunity to defend the Catholic faith against all detractors. Possidius also described Augustine's personal traits in detail, drawing a portrait of a man who ate sparingly, worked tirelessly, despised gossip, shunned the temptations of the flesh, and exercised prudence in the financial stewardship of his see.[17]

Teaching philosophy

Along with being a prominent figure in the religious spectrum, Augustine was also very influential in the history of education. He introduced the theory of three different types of students, and instructed teachers to adapt their teaching styles to each student's individual learning style. The three different kinds of students are: the student who has been well-educated by knowledgeable teachers; the student who has had no education; and the student who has had a poor education, but believes himself to be well-educated. If a student has been well educated in a wide variety of subjects, the teacher must be careful not to repeat what they have already learned, but to challenge the student with material which they do not yet know thoroughly. With the student who has had no education, the teacher must be patient, willing to repeat things until the student understands, and sympathetic. Perhaps the most difficult student, however, is the one with an inferior education who believes he understands something when he does not. Augustine stressed the importance of showing this type of student the difference between "having words and having understanding," and of helping the student to remain humble with his acquisition of knowledge.

Another radical idea which Augustine introduced is the idea of teachers responding positively to the questions they may receive from their students, no matter if the student interrupted his teacher.

Augustine also founded the restrained style of teaching. This teaching style ensures the students' full understanding of a concept because the teacher does not bombard the student with too much material; focuses on one topic at a time; helps them discover what they don't understand, rather than moving on too quickly; anticipates questions; and helps them learn to solve difficulties and find solutions to problem.

Yet another of Augustine's major contributions to education is his study on the styles of teaching. He claimed there are two basic styles a teacher uses when speaking to the students. The mixed style includes complex and sometimes showy language to help students see the beautiful artistry of the subject they are studying. The grand style is not quite as elegant as the mixed style, but is exciting and heartfelt, with the purpose of igniting the same passion in the students' hearts.[18]

Augustine balanced his teaching philosophy with the traditional Bible-based practice of strict discipline. For example, he agreed with using punishment as an incentive for children to learn. He believed all people tend toward evil, and students must therefore be physically punished when they allow their evil desires to direct their actions.[19]

Death

Shortly before Augustine's death, Roman Africa was overrun by the Vandals, a warlike tribe with Arian sympathies. They had entered Africa at the instigation of Count Boniface, but soon turned to lawlessness, plundering private citizens and churches and killing many of the inhabitants.[20] The Vandals arrived in the spring of 430 to besiege Hippo and during that time, Augustine endured his final illness.

Possidius records that one of the few miracles attributed to Augustine took place during the siege. While Augustine was confined to his sick bed, a man petitioned him that he might lay his hands upon a relative who was ill. Augustine replied that if he had any power to cure the sick, he would surely have applied it on himself first. The visitor declared that he was told in a dream to go to Augustine so that his relative would be made whole. When Augustine heard this, he no longer hesitated, but laid his hands upon the sick man, who departed from Augustine's presence healed.[21]

Possidius also gives a first-hand account of Augustine's death, which occurred on August 28, 430, during the siege of Hippo by the Vandals. Augustine spent his final days in prayer and repentance, requesting that the penitential Psalms of David be hung on his walls so that he could read them. He directed that the library of the church in Hippo and all the books therein should be carefully preserved.[22] Shortly after his death, the Vandals raised the siege of Hippo, but they returned not long thereafter and burned the city. They destroyed all of it but Augustine's cathedral and library, which they left untouched.

Tradition indicates that Augustine's body was later moved to Pavia, where it is said to remain to this day.[11] Another tradition, however, claims that his remains were moved to Cagliari (Karalis) in a small chapel at the base of a hill, on the summit of which lies the sanctuary of Bonaria. The chapel bears an ancient, weathered stone plaque with an inscription leading to St.Augustine's remains.

Works

Aurelius Augustinus | |

|---|---|

| Era | Ancient philosophy/Medieval philosophy |

| Region | Western Philosophers |

| School | Platonism, Neoplatonism, Christian philosophy, Stoicism |

Augustine was one of the most prolific Latin authors in terms of surviving works, and the list of his works consists of more than a hundred separate titles.[23] They include apologetic works against the heresies of the Arians, Donatists, Manichaeans and Pelagians, texts on Christian doctrine, notably De doctrina Christiana (On Christian Doctrine), exegetical works such as commentaries on Book of Genesis, the Psalms and Paul's Letter to the Romans, many sermons and letters, and the Retractationes (Retractions), a review of his earlier works which he wrote near the end of his life. Apart from those, Augustine is probably best known for his Confessiones (Confessions), which is a personal account of his earlier life, and for De civitate dei (The City of God, consisting of 22 books), which he wrote to restore the confidence of his fellow Christians, which was badly shaken by the sack of Rome by the Visigoths in 410. His De trinitate (On the Trinity), in which he developed what has become known as the 'psychological analogy' of the Trinity, is also among his masterpieces, and arguably one of the greatest theological works of all time.

Influence as a theologian and thinker

Augustine was a bishop, priest, and father who remains a central figure, both within Christianity and in the history of Western thought, and is considered by modern historian Thomas Cahill to be the first medieval man and the last classical man.[24] In both his philosophical and theological reasoning, he was greatly influenced by Stoicism, Platonism and Neo-platonism, particularly by the work of Plotinus, author of the Enneads, probably through the mediation of Porphyry and Victorinus (as Pierre Hadot has argued). Although he later abandoned Neo-Platonism some ideas are still visible in his early writings[25]. His generally favorable view of Neoplatonic thought contributed to the "baptism" of Greek thought and its entrance into the Christian and subsequently the European intellectual tradition. His early and influential writing on the human will, a central topic in ethics, would become a focus for later philosophers such as Schopenhauer and Nietzsche. In addition, Augustine was influenced by the works of Virgil (known for his teaching on language), Cicero (known for his teaching on argument), and Aristotle (particularly his Rhetoric and Poetics).

Augustine's concept of original sin was expounded in his works against the Pelagians. However, St. Thomas Aquinas took much of Augustine's theology while creating his own unique synthesis of Greek and Christian thought after the widespread rediscovery of the work of Aristotle. While Augustine's doctrine of divine predestination and efficacious grace would never be wholly forgotten within the Roman Catholic Church, finding eloquent expression in the works of Bernard of Clairvaux, Reformation theologians such as Martin Luther and John Calvin would look back to him as the inspiration for their avowed capturing of the Biblical Gospel.

Augustine was canonized by popular acclaim, and later recognized as a Doctor of the Church in 1298 by Pope Boniface VIII[citation needed]. His feast day is August 28, the day on which he died. He is considered the patron saint of brewers, printers, theologians, sore eyes, and a number of cities and dioceses.

The latter part of Augustine's Confessions consists of an extended meditation on the nature of time. Even the agnostic philosopher Bertrand Russell was impressed by this. He wrote, "a very admirable relativistic theory of time. ... It contains a better and clearer statement than Kant's of the subjective theory of time - a theory which, since Kant, has been widely accepted among philosophers."[26] Catholic theologians generally subscribe to Augustine's belief that God exists outside of time in the "eternal present"; that time only exists within the created universe because only in space is time discernible through motion and change. His meditations on the nature of time are closely linked to his consideration of the human ability of memory. Frances Yates in her 1966 study The Art of Memory argues that a brief passage of the Confessions, 10.8.12, in which Augustine writes of walking up a flight of stairs and entering the vast fields of memory [27] clearly indicates that the ancient Romans were aware of how to use explicit spatial and architectural metaphors as a mnemonic technique for organizing large amounts of information.

Augustine's philosophical method, especially demonstrated in his Confessions, has had continuing influence on Continental philosophy throughout the 20th century. His descriptive approach to intentionality, memory, and language as these phenomena are experienced within consciousness and time anticipated and inspired the insights of modern phenomenology and hermeneutics. Edmund Husserl writes: "The analysis of time-consciousness is an age-old crux of descriptive psychology and theory of knowledge. The first thinker to be deeply sensitive to the immense difficulties to be found here was Augustine, who laboured almost to despair over this problem."[28] Martin Heidegger refers to Augustine's descriptive philosophy at several junctures in his influential work, Being and Time.[29] Hannah Arendt, the much appreciated phenomenologist of social and political life, began her philosophical writing with a dissertation on Augustine's concept of love, Der Liebesbegriff bei Augustin (1929): "The young Arendt attempted to show that the philosophical basis for vita socialis in Augustine can be understood as residing in neighbourly love, grounded in his understanding of the common origin of humanity."[30] Jean Bethke Elshtain in Augustine and the Limits of Politics finds likeness between Augustine and Arendt in their concepts of evil: "Augustine did not see evil as glamorously demonic but rather as absence of good, something which paradoxically is really nothing. Arendt ... envisioned even the extreme evil which produced the Holocaust as merely banal [in Eichmann in Jerusalem]."[31] Augustine's philosophical legacy continues to influence contemporary critical theory through the contributions and inheritors of these 20th century figures.

According to Leo Ruickbie, Augustine's arguments against magic, differentiating it from miracle, were crucial in the early Church's fight against paganism and became a central thesis in the later denunciation of witches and witchcraft. According to Professor Deepak Lal, Augustine's vision of the heavenly city has influenced the secular projects and traditions of the Enlightenment, Marxism, Freudianism and Eco-fundamentalism.[32]

Influence on St. Thomas Aquinas

For quotations of St. Augustine by St. Thomas Aquinas see Aquinas and the Sacraments and Thought of Thomas Aquinas.

On the topic of original sin, Aquinas proposed a more optimistic view of man than that of Augustine in that his conception leaves to the reason, will, and passions of fallen man their natural powers even after the Fall.[33]

Influence on Protestant reformers

While in his pre-Pelagian writings Augustine taught that Adam's guilt as transmitted to his descendants much enfeebles, though does not destroy, the freedom of their will, Protestant reformers Martin Luther and John Calvin affirmed that Original Sin completely destroyed liberty(see total depravity).[33]

Theology

Natural knowledge and biblical interpretation

Augustine took the view that the Biblical text should not be interpreted literally if it contradicts what we know from science and our God-given reason. In "The Literal Interpretation of Genesis" (early 5th century, AD), St. Augustine wrote:

It not infrequently happens that something about the earth, about the sky, about other elements of this world, about the motion and rotation or even the magnitude and distances of the stars, about definite eclipses of the sun and moon, about the passage of years and seasons, about the nature of animals, of fruits, of stones, and of other such things, may be known with the greatest certainty by reasoning or by experience, even by one who is not a Christian. It is too disgraceful and ruinous, though, and greatly to be avoided, that he [the non-Christian] should hear a Christian speaking so idiotically on these matters, and as if in accord with Christian writings, that he might say that he could scarcely keep from laughing when he saw how totally in error they are. In view of this and in keeping it in mind constantly while dealing with the book of Genesis, I have, insofar as I was able, explained in detail and set forth for consideration the meanings of obscure passages, taking care not to affirm rashly some one meaning to the prejudice of another and perhaps better explanation.

— De Genesi ad literam 1:19–20, Chapt. 19 [AD 408]

With the scriptures it is a matter of treating about the faith. For that reason, as I have noted repeatedly, if anyone, not understanding the mode of divine eloquence, should find something about these matters [about the physical universe] in our books, or hear of the same from those books, of such a kind that it seems to be at variance with the perceptions of his own rational faculties, let him believe that these other things are in no way necessary to the admonitions or accounts or predictions of the scriptures. In short, it must be said that our authors knew the truth about the nature of the skies, but it was not the intention of the Spirit of God, who spoke through them, to teach men anything that would not be of use to them for their salvation.

— De Genesi ad literam, 2:9

A more clear distinction between "metaphorical" and "literal" in literary texts arose with the rise of the Scientific Revolution, although its source could be found in earlier writings, such as those of Herodotus (5th century BC). It was even considered heretical to interpret the Bible literally at times.[34]

Creation

In "The Literal Interpretation of Genesis" Augustine took the view that everything in the universe was created simultaneously by God, and not in seven calendar days like a plain account of Genesis would require. He argued that the six-day structure of creation presented in the book of Genesis represents a logical framework, rather than the passage of time in a physical way - it would bear a spiritual, rather than physical, meaning, which is no less literal. Augustine also does not envision original sin as originating structural changes in the universe, and even suggests that the bodies of Adam and Eve were already created mortal before the Fall. Apart from his specific views, Augustine recognizes that the interpretation of the creation story is difficult, and remarks that we should be willing to change our mind about it as new information comes up. [2]

In "City of God", Augustine rejected both the immortality of the human race proposed by pagans, and contemporary ideas of ages (such as those of certain Greeks and Egyptians) that differed from the Church's sacred writings:

Let us, then, omit the conjectures of men who know not what they say, when they speak of the nature and origin of the human race. For some hold the same opinion regarding men that they hold regarding the world itself, that they have always been... They are deceived, too, by those highly mendacious documents which profess to give the history of many thousand years, though, reckoning by the sacred writings, we find that not 6000 years have yet passed.

— Augustine, Of the Falseness of the History Which Allots Many Thousand Years to the World’s Past, The City of God, Book 12: Chapt. 10 [AD 419].

Original sin

Augustine viewed that a major result of original sin was disobedience of the flesh to the spirit as a punishment of their disobedience to God:

For it was not fit that His creature should blush at the work of his Creator; but by a just punishment the disobedience of the members was the retribution to the disobedience of the first man, for which disobedience they blushed when they covered with fig-leaves those shameful parts which previously were not shameful.

Although, if those members by which sin was committed were to be covered after the sin, men ought not indeed to have been clothed in tunics, but to have covered their hand and mouth, because they sinned by taking and eating. What, then, is the meaning, when the prohibited food was taken, and the transgression of the precept had been committed, of the look turned towards those members? What unknown novelty is felt there, and compels itself to be noticed? And this is signified by the opening of the eyes... As, therefore, they were so suddenly ashamed of their nakedness, which they were daily in the habit of looking upon and were not confused, that they could now no longer bear those members naked, but immediately took care to cover them; did not they--he in the open, she in the hidden impulse--perceive those members to be disobedient to the choice of their will, which certainly they ought to have ruled like the rest by their voluntary command? And this they deservedly suffered, because they themselves also were not obedient to their Lord. Therefore they blushed that they in such wise had not manifested service to their Creator, that they should deserve to lose dominion over those members by which children were to be procreated.— Against Two Letters of the Pel agians 1.31-32

The view that sex was an evil was prevalent in Augustine's time. Plotinus, a neo-Platonist that Augustine praises in his Confessions,[35] taught that only through disdain for fleshly desire could one reach the ultimate state of mankind.[36] Augustine, likewise, had served as a "Hearer" for the Manicheans for about nine years,[37] and they also taught that the original sin was carnal knowledge.[38]

In his pre-Pelagian writings, Augustine taught that Original Sin was transmitted by concupiscence (roughly, lust), making humanity a massa damnata (mass of perdition, condemned crowd) and much enfeebling, though not destroying, the freedom of the will. In the struggle against Pelagianism, the principles of Augustine's teaching were confirmed by many councils, especially the Second Council of Orange (529). Anselm of Canterbury established the definition that was followed by the great Schoolmen, namely that Original Sin is the "privation of the righteousness which every man ought to possess", thus separating it from concupiscence, with which Augustine's disciples had often defined it, as later did Luther and Calvin, who instead of seeing concupiscence, like Augustine, as a vehicle of transmission of Original Sin actually equated the two, a doctrine condemned in 1567 by Pope Pius V.[33]

Augustine's formulation of the doctrine of original sin has substantially influenced both Catholic and Reformed (that is, Calvinist) theology. His understanding of sin and grace was developed against that of Pelagius.[39] Expositions on the topics are found in his works On Original Sin, On the Predestination of the Saints, On the Gift of Perseverance and On Nature and Grace.

Original sin, according to Augustine, consists of the guilt of Adam which all human beings inherit. As sinners, human beings are utterly depraved in nature, lack the freedom to do good, and cannot respond to the will of God without divine grace. Grace is irresistible, results in conversion, and leads to perseverance.[39] Augustine's idea of predestination rests on the assertion that God has foreordained, from eternity, those who will be saved. The number of the elect is fixed.[39] God has chosen the elect certainly and gratuitously, without any previous merit (ante merita) on their part.

The Roman Catholic Church considers Augustine's teaching to be consistent with free will.[40] He often said that any can be saved if they wish.[40] While God knows who will be saved and who will not, with no possibility that one destined to be lost will be saved, this knowledge represents God's perfect knowledge of how humans will freely choose their destinies.[40]

Ecclesiology

Augustine developed his doctrine of the church principally in reaction to the Donatist sect. He taught a distinction between the "church visible" and "church invisible". The former is the institutional body on earth which proclaims salvation and administers the sacraments while the latter is the invisible body of the elect, made up of genuine believers from all ages, and who are known only to God. The visible church will be made up of "wheat" and "tares", that is, good and wicked people (as per Mat. 13:30), until the end of time. This concept countered the Donatist claim that they were the only "true" or "pure" church on earth.[39]

Augustine's ecclesiology was more fully developed in City of God. There he conceives of the church as a heavenly city or kingdom, ruled by love, which will ultimately triumph over all earthly empires which are self-indulgent and ruled by pride. Augustine followed Cyprian in teaching that the bishops of the church are the successors of the apostles.[39]

In addition, he believed in papal supremacy.[41]

Sacramental theology

Also in reaction against the Donatists, Augustine developed a distinction between the "regularity" and "validity" of the sacraments. Regular sacraments are performed by clergy of the Catholic church while sacraments performed by schismatics are considered irregular. Nevertheless, the validity of the sacraments do not depend upon the holiness of the priests who perform them; therefore, irregular sacraments are still accepted as valid provided they are done in the name of Christ and in the manner prescribed by the church. On this point Augustine departs from the earlier teaching of Cyprian, who taught that converts from schismatic movements must be re-baptised.[39]

Against the Pelagians Augustine strongly stressed the importance of infant baptism. He believed that no one would be saved unless he or she had received baptism in order to be cleansed from original sin. He also maintained that unbaptized children would go to hell. It was not until the 12th century that pope Innocent III accepted the doctrine of limbo as promulgated by Peter Abelard. It was the place where the unbaptized went and suffered no pain but, as the Church maintained, being still in a state of original sin, they did not deserve Paradise, therefore they did not know happiness either. Non-conformist religions such as the Unitarians and the Quakers never held to the concept. The Eastern Orthdox position is that Original Sin does not carry over the guilt of Original Sin (which only Adam himself is guilty of) but only the consequences of Original Sin. For this reason, they disagree with Augustine's belief that unbaptized infants will go to hell or to even a state of limbo as advocated by Anselm.[citation needed]

Mariology

Augustine did not develop an independent mariology, but his statements on Mary surpass in number and depths those of other early writers. [42] The Virgin Mary “conceived as virgin, gave birth as virgin and stayed virgin forever [43] Even before the Council of Ephesus, he defended the ever Virgin Mary as the mother of God, who, because of her virginity, is full of grace [44] She was free of any temporal sin, [45] Because of a woman, the whole human race was saved. [46]

Eschatology

Augustine originally believed that Christ would establish a literal 1,000-year kingdom prior to the general resurrection (premillennialism or chiliasm) but rejected the system as carnal. He was the first theologian to systematically expound a doctrine of amillennialism, although some theologians and Christian historians believe his position was closer to that of modern postmillennialists. The mediaeval Catholic church built its system of eschatology on Augustinian amillennialism, where the Christ rules the earth spiritually through his triumphant church.[47] At the Reformation, theologians such as John Calvin accepted amillennialism while rejecting aspects of mediaeval ecclesiology which had been built on Augustine's teaching.

Augustine taught that the eternal fate of the soul is determined at death,[48][49] and that purgatorial fires of the intermediate state purify only those that died in communion with the Church. His teaching provided fuel for later theology.[48]

Just war

Augustine developed a theology of just war, that is, war that is acceptable under certain conditions. Firstly, war must occur for a good and just purpose rather than for self-gain or as an exercise of power. Secondly, just war must be waged by a properly instituted authority such as the state. Thirdly, love must be a central motive even in the midst of violence.[50]

Views on lust

Augustine struggled with lust throughout his life. He associated sexual desire with the sin of Adam, and believed that it was still sinful, even though the Fall has made it part of human nature.

In the Confessions, Augustine describes his personal struggle in vivid terms: "But I, wretched, most wretched, in the very commencement of my early youth, had begged chastity of Thee, and said, 'Grant me chastity and continence, only not yet.'"[51] At sixteen Augustine moved to Carthage where again he was plagued by this "wretched sin":

There seethed all around me a cauldron of lawless loves. I loved not yet, yet I loved to love, and out of a deep-seated want, I hated myself for wanting not. I sought what I might love, in love with loving, and I hated safety... To love then, and to be beloved, was sweet to me; but more, when I obtained to enjoy the person I loved. I defiled, therefore, the spring of friendship with the filth of concupiscence, and I beclouded its brightness with the hell of lustfulness.

— Confessions 3.1.1

For Augustine, the evil was not in the sexual act itself, but rather in the emotions that typically accompany it. To the pious virgins raped during the sack of Rome, he writes, "Truth, another's lust cannot pollute thee." Chastity is "a virtue of the mind, and is not lost by rape, but is lost by the intention of sin, even if unperformed."[40]

In short, Augustine's life experience led him to consider lust to be one of the most grievous sins, and a serious obstacle to the virtuous life.

Statements on Jews

Against certain Christian movements rejecting the use of Hebrew Scriptures, Augustine countered that God had chosen the Jews as a his people, though he also considered the scattering of Jews by the Roman empire to be a fulfillment of prophecy.[52][53]

Augustine also quotes part of the same prophecy that says "Slay them not, lest they should at last forget Thy law" (Psalm 59:11). Augustine argued that God had allowed the Jews to survive this dispersion as a warning to Christians, thus they were to be permitted to dwell in Christian lands. Augustine further argued that the Jews would be converted at the end of time.[54]

Abortion and ensoulment

Like other Church Fathers, St Augustine "vigorously condemned the practice of induced abortion".[55] In his works, Augustine did consider that the gravity of participation in an abortion depended whether or not the fetus had yet received a soul at the time of abortion.[56] He held that this ensoulment occurred at 40 days for males, and 90 for females.[55]

In the summer of 2008, this aspect of Augustine's thought (i.e., the gravity of abortion vis-a-vis the ensoulment of the fetus) was used by the Speaker of the US House of Representatives, Nancy Pelosi, in defence of her pro-choice political stance. She quoted one of his works, in which he wrote:

"The law does not provide that the act [abortion] pertains to homicide, for there cannot yet be said to be a live soul in a body that lacks sensation.'[57]

In the week following her comments, she was corrected by numerous American bishops, such as Archbishop Charles J. Chaput of Denver, who wrote: "In the absence of modern medical knowledge, some of the Early Fathers held that abortion was homicide; others that it was tantamount to homicide; and various scholars theorized about when and how the unborn child might be animated or "ensouled." But none diminished the unique evil of abortion as an attack on life itself..."[58]

Works (books, letters and sermons)

- On Christian Doctrine (Template:Lang-la, 397-426)

- Confessions (Confessiones, 397-398)

- City of God (De civitate Dei, begun ca. 413, finished 426)

- On the Trinity (De trinitate, 400-416)

- Enchiridion (Enchiridion de fide, spe et caritate)

- Retractions (Retractationes): At the end of his life (ca. 426-428) Augustine revisited his previous works in chronological order in a work titled the Retractions (in Latin, "Retractationes"). The English translation of the title has led some to assume that at the end of his career, Augustine retreated from his earlier theological positions. In fact, the Latin title literally means 're-treatments" (not "Retractions") and though in this work Augustine suggested what he would have said differently, it provides little in the way of actual "retraction." It does, however, give the reader a rare picture of the development of a writer and his final thoughts.

- The Literal Meaning of Genesis (De Genesi ad litteram)

- On Free Choice of the Will (De libero arbitrio)

- On the Catechising of the Uninstructed (De catechizandis rudibus)

- On Faith and the Creed (De fide et symbolo)

- Concerning Faith of Things Not Seen (De fide rerum invisibilium)

- On the Profit of Believing (De utilitate credendi)

- On the Creed: A Sermon to Catechumens (De symbolo ad catechumenos)

- On Continence (De continentia)

- On the Good of Marriage (De bono coniugali)

- On Holy Virginity (De sancta virginitate)

- On the Good of Widowhood (De bono viduitatis)

- On Lying (De mendacio)

- To Consentius: Against Lying (Contra mendacium [ad Consentium])

- On the Work of Monks (De opere monachorum)

- On Patience (De patientia)

- On Care to be Had For the Dead (De cura pro mortuis gerenda)

- On the Morals of the Catholic Church and on the Morals of the Manichaeans (De moribus ecclesiae catholicae et de moribus Manichaeorum)

- On Two Souls, Against the Manichaeans (De duabus animabus [contra Manichaeos])

- Acts or Disputation Against Fortunatus the Manichaean ([Acta] contra Fortunatum [Manichaeum])

- Against the Epistle of Manichaeus Called Fundamental (Contra epistulam Manichaei quam vocant fundamenti)

- Reply to Faustus the Manichaean (Contra Faustum [Manichaeum])

- Concerning the Nature of Good, Against the Manichaeans (De natura boni contra Manichaeos)

- On Baptism, Against the Donatists (De baptismo [contra Donatistas])

- The Correction of the Donatists (De correctione Donatistarum)

- On Merits and Remission of Sin, and Infant Baptism (De peccatorum meritis et remissione et de baptismo parvulorum)

- On the Spirit and the Letter (De spiritu et littera)

- On Nature and Grace (De natura et gratia)

- On Man's Perfection in Righteousness (De perfectione iustitiae hominis)

- On the Proceedings of Pelagius (De gestis Pelagii)

- On the Grace of Christ, and on Original Sin (De gratia Christi et de peccato originali)

- On Marriage and Concupiscence (De nuptiis et concupiscientia)

- On the Nature of the Soul and its Origin (De natura et origine animae)

- Against Two Letters of the Pelagians (Contra duas epistulas Pelagianorum)

- On Grace and Free Will (De gratia et libero arbitrio)

- On Rebuke and Grace (De correptione et gratia)

- On the Predestination of the Saints (De praedestinatione sanctorum)

- On the Gift of Perseverance (De dono perseverantiae)

- Our Lord's Sermon on the Mount (De sermone Domini in monte)

- On the Harmony of the Evangelists (De consensu evangelistarum)

- Treatises on the Gospel of John (In Iohannis evangelium tractatus)

- Soliloquies (Soliloquiorum libri duo)

- Enarrations, or Expositions, on the Psalms (Enarrationes in Psalmos)

- On the Immortality of the Soul (De immortalitate animae)

- Answer to the Letters of Petilian, Bishop of Cirta (Contra litteras Petiliani)

- Sermons, among which a series on selected lessons of the New Testament

- Homilies, among which a series on the First Epistle of John

Quotes

Of all the fathers of the church, St. Augustine was the most admired and the most influential during the Middle Ages... Augustine was an outsider - a native North African whose family was not Roman but Berber... He was a genius - an intellectual giant.[59]

References

- ^ Wells, J. (2000). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (2 ed.). New York: Longman. ISBN 0582364671.

- ^ The nomen Aurelius is virtually meaningless, signifying little more than Roman citizenship (see: Salway, Benet (1994). "What's in a Name? A Survey of Roman Onomastic Practice from c. 700 B.C. to A.D. 700". The Journal of Roman Studies. 84. Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies: 124–45. ISSN 0075-4358.).

- ^ The American Heritage College Dictionary. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. 1997. p. 91. ISBN 0395669170.

- ^

Cross, Frank L. and Livingstone, Elizabeth, ed. (2005). "Platonism". The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. Oxford Oxfordshire: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0192802909.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ Durant, Will (1992). Caesar and Christ: a History of Roman Civilization and of Christianity from Their Beginnings to A.D. 325. New York: MJF Books. ISBN 1567310141.

- ^ Wilken, Robert L. (2003). The Spirit of Early Christian Thought. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 291. ISBN 0300105983.

- ^ Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Archimandrite [now Archbishop] Chrysostomos. "Book Review: The Place of Blessed Augustine in the Orthodox Church". Orthodox Tradition. II (3&4): 40–43. Retrieved 2007-06-28.

- ^ "Blessed" here does not mean that he is less than a saint, but is a title bestowed upon him as a sign of respect. "Blessed Augustine of Hippo: His Place in the Orthodox Church: A Corrective Compilation". Orthodox Tradition. XIV (4): 33–35. Retrieved 2007-06-28.

- ^ (a) Encyclopedia Americana, Scholastic Library Publishing, 2005, v.3, p.569 (b) Norman Cantor. The Civilization of the Middle Ages, A Completely Revised and Expanded Edition of Medieval History, Harper Perennial, 1994, p.74. ISBN 0060925531 (c) Étienne Gilson, Le philosophe et la théologie (1960), Vrin, 2005, p.175 (d) Gilbert Meynier, L'Algérie des origines, La Découverte, 2007, p.73, ISBN 2707150886 (e) Grand Larousse encyclopédique, Librairie Larousse, 1960, t.1, p.144 (f) American University, Area Handbook for Algeria, Government printing office, 1965, p.10 (g) Fernand Braudel, Grammaire des civilisations (1963), Flammarion, 2008, p.453, etc

- ^ a b c d e f g h Encyclopedia Americana, v.2, p. 685. Danbury, CT: Grolier Incorporated, 1997. ISBN 0-717-20129-5.

- ^ Andrew Knowles and Pachomios Penkett, Augustine and his World Ch.2.

- ^ Monica was a Berber name derived from the Libyan deity Mon worshiped in the neighbouring town of Thibilis. However, no information is available on the ethnicity of her husband.

- ^ According to J.Fersuson and Garry Wills, Adeodatus, the name of Augustine's son is a Latinization of the Berber name Iatanbaal (given by God).

- ^ Conf. 8.7.17

- ^ "...et legi in silentio capitulum quo primum coniecti sunt oculi mei: non in comessationibus et ebrietatibus, non in cubilibus et impudicitiis, non in contentione et aemulatione, sed induite dominum Iesum Christum et carnis providentiam ne feceritis in concupiscentiis." Confessiones 8.12.29

- ^ Weiskotten, Herbert T. The Life of Saint Augustine: A Translation of the Sancti Augustini Vita by Possidius, Bishop of Calama . Merchantville, NJ: Evolution Publishing, 2008. ISBN 1-889758-90-6

- ^ Encyclopedia of Education

- ^ http://www.cals.ncsu.edu/agexed/aee501/augustine.html

- ^ Weiskotten, 40

- ^ Weiskotten, 43

- ^ Weiskotten, 57

- ^ Passage based on F.A. Wright and T.A. Sinclair, A History of Later Latin Literature (London 1931), pp. 56 ff.

- ^ Thomas Cahill, How the Irish Saved Civilization Ch.2.

- ^ Bertrand Russell History of western Philosophy Book II Chapter IV

- ^ History of Western Philosophy, 1946, reprinted Unwin Paperbacks 1979, pp 352-3

- ^ Confessiones Liber X: commentary on 10.8.12 (in Latin)

- ^ Husserl, Edmund. Phenomenology of Internal Time-Consciousness. Tr. James S. Churchill. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 1964, 21.

- ^ For example, Heidegger's articulations of how "Being-in-the-world" is described through thinking about seeing: "The remarkable priority of 'seeing' was noticed particularly by Augustine, in connection with his Interpretation of concupiscentia." Heidegger then quotes the Confessions: "Seeing belongs properly to the eyes. But we even use this word 'seeing' for the other senses when we devote them to cognizing... We not only say, 'See how that shines', ... 'but we even say, 'See how that sounds'". Being and Time Trs. Macquarrie & Robinson. New York: Harpers, 1964. 171

- ^ Chiba, Shin. Hannah Arendt on Love and the Political: Love, Friendship, and Citizenship.The Review of Politics, Vol. 57, No. 3 (Summer, 1995), 507.

- ^ Tinder, Glenn. The American Political Science Review, Vol. 91, No. 2 (Jun., 1997), pp. 432-433

- ^ Lal, D. Morality and Capitalism: Learning from the Past. Working Paper Number 812, Department of Economics, University of California, Los Angeles. March 2002

- ^ a b c Cross, F. L., ed. The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005, article Original Sin Cite error: The named reference "Oxford:Original" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Origen, St. Jerome: "On First Principles", Book III, Chapter III, Verse 1. Translated by K. Froehlich. Biblical Interpretation in the Early Church. Fortress Press, 1985

- ^ Conf. 8.2

- ^ Gerson, Lloyd P. Plotinus. New York, NY: Routledge, 1994. 203

- ^ Brown, Peter. Augustine of Hippo. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1967. ISBN 0-520-00186-9, 35

- ^ Manichaean Version of Genesis 2-4, the. Translated from the Arabic text of Ibn al-Nadīm, Fihrist, as reproduced by G. Flügel, Mani: Seine Lehre und seine Schriften (Leipzig, 1862; reprinted, Osnabrück: Biblio Verlag, 1969) 58.11-61.13. 10 December 2006 (http://www.religiousstudies.uncc.edu/jcreeves/manichaean_version_of_genesis_2-4.htm).

- ^ a b c d e f Justo L. Gonzalez (1970–1975). A History of Christian Thought: Volume 2 (From Augustine to the eve of the Reformation). Abingdon Press.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - ^ a b c d Catholic Encyclopedia (1914) Cite error: The named reference "multiple" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ "Carthage was also near the countries over the sea, and distinguished by illustrious renown,so that it had a bishop of more than ordinary influence, who could afford to disregard a number of conspiring enemies because he saw himself joined by letters of communion to the Roman Church, in which the supremacy of an apostolic chair has always flourished" Letter 43 Chapter 9

- ^ O Stegmüller, in Marienkunde, 455

- ^ De Saca virginitate 18

- ^ De Sacra Virginitate, 6,6, 191.

- ^ but theologians disagree as to whether Augustine considered Mary free of original sin as well. Thomas Aquinas and Bonaventura Hugo Rahner against Henry Newman and others

- ^ Per feminam mors, per feminam vita De Sacra Virginitate,289

- ^ Craig L. Blomberg (2006). From Pentecost to Patmos. Apollos. p. 519.

- ^ a b Cross, F. L., ed. The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005, unspecified article

- ^ Enchiridion 110

- ^ Justo L. Gonzalez (1984). The Story of Christianity. HarperSanFrancisco.

- ^ Conf. 8.7.17

- ^ Diarmaid MacCulloch. The Reformation (Penguin Group, 2005) p8.

- ^ City of God, book 18, chapter 46.

- ^ J. Edwards, The Spanish Inquisition (Stroud, 1999), pp33-5.

- ^ a b Fitzgerald, 1

- ^ http://news.yahoo.com/s/ap/20080828/ap_on_el_pr/cvn_pelosi_theology

- ^ [1] 'Pelosi camp responds to archbishop's critique'

- ^ http://www.archden.org/images/ArchbishopCorner/ByTopic/onseparationofsense&state_openlettercjc8.25.08.pdf

- ^ Cantor, Norman (1993). The Civilization of the Middle Ages: A completely revised and expanded edition of Medieval history, the life and death of a civilization. London: HarperCollins. p. 74. ISBN 0060170336.

Bibliography

- Magee, Bryan (1998). The Story of Thought. London: The Quality Paperback Bookclub. ISBN 0789444550.

- Magee, Bryan (1998). The Story of Philosophy: The Essential Guide to the History of Western Philosophy. New York: DK Pub. ISBN 078947994X.

- g Saint Augustine, pages 30, 144; City of God 51, 52, 53 and The Confessions 50, 51, 52

- Wiener, Philip (1973). "Platonism in the Renaissance". Dictionary of the History of Ideas. Vol. 5. New York: Scribner. pp. 510-15 (vol. 3). ISBN 0684132931.

(...) Saint Augustine asserted that Neo-Platonism possessed all spiritual truths except that of the Incarnation. (...)

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - Brown, Peter (1967). Augustine of Hippo. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-00186-9.

- Matthews, Gareth B. (2005). Augustine. Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-23348-2.

- O'donnell, James (2005). Augustine: A New Biography. New York: ECCO. ISBN 0060535377.

- Ruickbie, Leo (2004). Witchcraft out of the Shadows. London: Robert Hale. pp. 57–8. ISBN 0709075677.

- Tanquerey, Adolphe (2001). The Spiritual Life: A Treatise on Ascetical and Mystical Theology. Rockford, IL: Tan Books & Publishers. pp. 37). ISBN 0895556596.

- von Heyking, John (2001). Augustine and Politics as Longing in the World. Columbia: University of Missouri Press. ISBN 0826213499.

- Lubin, Augustino (1659). Orbis Augustinianus sive conventuum ordinis eremitarum Sancti Augustini - chorographica et topographica descriptio. Paris.

- Pollman, Karla (2007). Saint Augustine the Algerian. Göttingen: Edition Ruprecht. ISBN 3897442094.

- Règle de St. Augustin pour les religieuses de son ordre; et Constitutions de la Congrégation des Religieuses du Verbe-Incarné et du Saint-Sacrament (Lyon: Chez Pierre Guillimin, 1662), pp. 28-29. Cf. later edition published at Lyon (Chez Briday, Libraire,1962), pp. 22-24. English edition, (New York: Schwartz, Kirwin, and Fauss, 1893), pp. 33-35.

- Zumkeller O.S.A., Adolar (1986). Augustine's Ideal of the Religious Life. New York: Fordham University Press. ISBN 0823211053.

- Zumkeller O.S.A., Adolar (1987). Augustine's Rule. Villanova: Augustinian Press. ISBN 0941491064.

- Pottier, René (2006). Saint Augustin le Berbère (in French). Fernand Lanore. ISBN 2851572822.

- Fitzgerald, Allan D., O.S.A., General Editor (1999). Augustine through the Ages: An Encyclopedia. Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. ISBN 0-8028-3843-X.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Plumer, Eric Antone, (2003). Augustine's Commentary on Galatians. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-199-24439-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Weiskotten, Herbert T. (2008). The Life of Saint Augustine: A Translation of the Sancti Augustini Vita by Possidius, Bishop of Calama. Merchantville, NJ: Evolution Publishing. ISBN 1-889-75890-6.

Translations

- Augustine of Hippo (2002). Henry William Griffen (ed.). Sermons to the People: Advent, Christmas, New year, Epiphany. New York: Image Books/Doubleday. ISBN 9780385503112.

See also

External links

- General:

- Augustine of Hippo edited by James J. O'Donnell – texts, translations, introductions, commentaries, etc.

- Augustine of Hippo at EarlyChurch.org.uk – extensive bibliography and on-line articles

- Works by Augustine:

- St. Augustine at the Christian Classics Ethereal Library

- Aurelius Augustinus at "IntraText Digital Library" – texts in several languages, with concordance and frequency list

- Augustinus.it – Latin and Italian texts

- Sanctus Augustinus at Documenta Catholica Omnia – Latin

- City of God, Confessions, Enchiridion, Doctrine audio books

- Biography and criticism:

- Augustinian Order

- Church Fathers

- Doctors of the Church

- Roman Catholic philosophers

- Roman Catholic theologians

- Roman Catholic bishops

- Roman Catholic writers

- Christian philosophers

- Christian theologians

- Christian vegetarians

- Amillennialism

- Neoplatonists

- Anti-Gnosticism

- Theories of history

- Sociocultural evolution

- Converts to Christianity

- Converts to Roman Catholicism

- Algerian Roman Catholic saints

- Late Antique writers

- Ancient Roman rhetoricians

- Berber

- Algerian people

- Algerian saints

- Latin letter writers

- 354 births

- 430 deaths

- Burials at San Pietro in Ciel d'Oro, Pavia

- Systematic theologians

- Berber people

- Late antique Latin writers

- African saints

- African philosophers

- Autobiographers

- Roman Catholic Mariology

- Theologians

- Romans from Africa

- 5th-century Christian saints