Libyan civil war (2011): Difference between revisions

→No-fly zone: clarify time frame and involved nations a tad |

→No-fly zone: Add ref and correct other ref |

||

| Line 433: | Line 433: | ||

On 12 March, the foreign ministers of the [[Arab League]] agreed to ask the UN to impose a no-fly zone over Libya. That brought a joint NATO/Arab-enforced fly-zone closer to establishment.<ref name = LibyanAF /> The rebels have stated that a no-fly zone alone would not be enough, because the majority of the bombardment is coming from things other than aircraft – particularly tanks and rockets. <ref>{{cite news | author=[[Chris McGreal|McGreal, Chris]] | title = Libyan Rebels Urge West To Assassinate Gaddafi as His Forces Near Benghazi – Appeal To Be Made as G8 Foreign Ministers Consider Whether To Back French and British Calls for a No-Fly Zone over Libya | url = http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2011/mar/14/libyan-rebel-leaders-gaddafi-benghazi | work = [[The Guardian]]| date = 14 March 2011|accessdate=15 March 2011}}</ref> |

On 12 March, the foreign ministers of the [[Arab League]] agreed to ask the UN to impose a no-fly zone over Libya. That brought a joint NATO/Arab-enforced fly-zone closer to establishment.<ref name = LibyanAF /> The rebels have stated that a no-fly zone alone would not be enough, because the majority of the bombardment is coming from things other than aircraft – particularly tanks and rockets. <ref>{{cite news | author=[[Chris McGreal|McGreal, Chris]] | title = Libyan Rebels Urge West To Assassinate Gaddafi as His Forces Near Benghazi – Appeal To Be Made as G8 Foreign Ministers Consider Whether To Back French and British Calls for a No-Fly Zone over Libya | url = http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2011/mar/14/libyan-rebel-leaders-gaddafi-benghazi | work = [[The Guardian]]| date = 14 March 2011|accessdate=15 March 2011}}</ref> |

||

On March 17, 2011, the United Nations Security Council approved a no-fly zone, amongst other measures, by a vote of 10 in favor, zero against, and five abstentions. The [[United Nations Security Council Resolution 1973|resolution]] authorizes member states 'to take all necessary measures… to protect civilians and civilian populated areas under threat of attack in the Libyan Arab Jamhariya, including Benghazi, while excluding an occupation force'.<ref name=UN News Centre>{{cite web |url=http://www.un.org/apps/news/story.asp?NewsID= |

On March 17, 2011, the United Nations Security Council approved a no-fly zone, amongst other measures, by a vote of 10 in favor, zero against, and five abstentions. The [[United Nations Security Council Resolution 1973|resolution]] authorizes member states 'to take all necessary measures… to protect civilians and civilian populated areas under threat of attack in the Libyan Arab Jamhariya, including Benghazi, while excluding an occupation force'.<ref name=UN News Centre>{{cite web |url=http://www.un.org/apps/news/story.asp?NewsID=37808&Cr=libya&Cr1= |title=Security Council authorizes ‘all necessary measures’ to protect civilians in Libya |author=UN |date=17 March 2011 |work=UN News Centre |publisher= |accessdate=17 March 2011}}</ref><ref> {{cite web|url=http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2011/mar/17/un-security-council-resolution|publisher=Guardian.co.uk|title=UN security council resolution on Libya – full text}}</ref> |

||

Although the no fly zone is immediately enforcable, and several countries have prepared to take immediate action, it is unclear how long the operation will take to enforce the measures. Some reports state this could be 'within hours', wheras previous repports hinted at several days. Which nations and their roles in applying these measures thave not yet been specified, although France and the UK have stated their intention to uphold them as a matter of urgency, and Lebanon and the US heavily backed the resolution.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-12770467 |title=BBC News - Libya: UK forces prepare after UN no-fly zone vote |date=18 March 2011 |work=BBC News |publisher=BBC |accessdate=18 March 2011}}</ref> |

Although the no fly zone is immediately enforcable, and several countries have prepared to take immediate action, it is unclear how long the operation will take to enforce the measures. Some reports state this could be 'within hours', wheras previous repports hinted at several days. Which nations and their roles in applying these measures thave not yet been specified, although France and the UK have stated their intention to uphold them as a matter of urgency, and Lebanon and the US heavily backed the resolution.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-12770467 |title=BBC News - Libya: UK forces prepare after UN no-fly zone vote |date=18 March 2011 |work=BBC News |publisher=BBC |accessdate=18 March 2011}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 00:46, 18 March 2011

A request that this article title be changed to Libyan Civil War is under discussion. Please do not move this article until the discussion is closed. |

This article documents a current event. Information may change rapidly as the event progresses, and initial news reports may be unreliable. The latest updates to this article may not reflect the most current information. (February 2011) |

| 2011 Libyan uprising | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of 2010–11 Middle East and North Africa protests | |||||||

(situation as of 15 March) | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

Limited/alleged: Supported by: |

Limited/alleged: | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

8,000 defected soldiers (in Benghazi)[14] Saaiqa 36 Battalion (on the front)[15] 5,000 volunteers (3 March; anti-Gaddafi claim)[16] | 10,000–12,000 (Al Jazeera estimate)[17] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 1,148-1,422 opposition fighters killed (see here) | 412-443 government fighters killed (see here) | ||||||

|

Total number of people killed on both sides, includes protesters, rebel fighters, captives executed, and government forces: 1,000 killed (United Nations) (by 7 March)[18] 2,000 killed (WHO) (by 2 March)[19] 3,000 killed (IFHR) (by 5 March)[20] 6,000 killed (LHRL) (by 5 March)[21] 10,000 killed (ICC) (by 7 March)[22] | |||||||

The 2011 Libyan uprising began as a series of protests and confrontations occurring in the North African state of Libya against Muammar Gaddafi's 42-year rule. The protesters are calling for his ousting and democratic elections.

The protests began on 15 February 2011 and escalated into a widespread uprising by the end of February, with fighting verging at the brink of civil war as of 6 March 2011[update]. Slogans from the uprisings in Tunisia and Egypt have been used, connecting the Libyan uprising with the wider 2010–11 Middle East and North Africa protests.[23] By the end of February, Gaddafi had lost control of a significant part of the country, including the major cities of Misurata and Benghazi.[24][25] The Libyan opposition had formed a National Transitional Council and free press had begun to operate in Cyrenaica.[26] Social media had played an important role in organizing the opposition.[27]

Gaddafi has remained in continuous control of Tripoli,[28] Sirt,[29] Zliten,[30] and Sabha,[31] as well as several other towns. Gaddafi controls the well-armed Khamis Brigade, among other loyalist military and police units, and some believe a small number of foreign mercenaries.[32] Some of Gaddafi's officials, as well as a number of current and retired military personnel, have sided with the protesters and requested outside help in bringing an end to massacres of non-combatants.

Most nations have strongly condemned Gaddafi's use of force against civilians.[33] Canada, the United States, Japan, Australia, the United Kingdom, France, Jordan, and Russia have all imposed sanctions on Gaddafi, many including travel bans on the longtime leader, members of his family, and top officials in his government. The United Nations Security Council passed an initial resolution freezing the assets of Gaddafi and 10 members of his inner circle and restricting their travel. The resolution also referred the regime in Tripoli to the International Criminal Court for investigation.[34] On March 17 a further resolution was announced which authorized member states 'to take all necessary measures… to protect civilians and civilian populated areas under threat of attack in the Libyan Arab Jamhariya, including Benghazi, while excluding an occupation force'.Cite error: The <ref> tag has too many names (see the help page). However, a few state leaders in Latin America have expressed support for Gaddafi's government[33] for which they were criticized by other world leaders.[35][36][37][38] The European Union's arms trafficking watchdog has stated that during the crisis Gaddafi has received military shipments from Belarus.[39][40]

On 10 March, France recognized the National Transitional Council as the official government of Libya.[41] Gaddafi has attributed the protests against him on "rats" and "cockroaches" who have been influenced by "hallucinogenic drugs" put in drinks and pills, "Al-Qaeda",[42] as well as alcohol.[43][44][45] He also has variously claimed that the protests against his rule are "a colonialist plot" by foreign countries to "control oil" and "enslave" Libyan people. Gaddafi has asserted that he will chase down the protesters "house by house" and they will be executed.[46][47][48][49][50]

To see the day by day progression the 2011 Libyan uprising, please see Timeline of the 2011 Libyan uprising.

Background

History

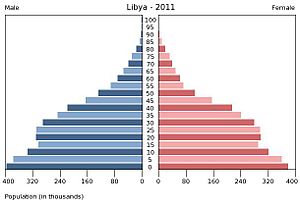

Gaddafi has ruled Libya as de facto autocrat since overthrowing the monarchy in 1969.[51] Following the retirement of Fidel Castro in 2008 and the death of Omar Bongo in 2009, Gaddafi is the world's longest-ruling non-royal head of state.[52] WikiLeaks' disclosure of confidential US diplomatic cables has revealed US diplomats there speaking of Gaddafi's "mastery of tactical maneuvering".[53] While placing relatives and loyal members of his tribe in central military and government positions, he has skilfully marginalized supporters and rivals, thus maintaining a delicate balance of powers, stability and economic developments. This extends even to his own children, as he changes affections to avoid the rise of a clear successor and rival.[53] Petroleum revenues contribute up to 58% of Libya's GDP.[54] Governments with "resource curse" revenue have a lower need for taxes from other industries and consequently are less willing to develop their middle class. To calm down opposition, such governments can use the income from natural resources to offer services to the population, or to specific government supporters.[55] The government of Libya can utilize these techniques by using the national oil resources.[56] Libya's oil wealth was spread over a relatively small population of six million,[57] with 21% general unemployment, the highest in the region, according to the latest census figures.[58]

Libya's purchasing power parity (PPP) GDP per capita in 2010 was US $14,878; its human development index in 2010 was 0.755; and its literacy rate in 2009 was 87%. These numbers were lower in Egypt and Tunisia.[59] Indeed, Libyan citizens are considered to be well educated and to have a high standard of living.[60] Its corruption perception index in 2010 was 2.2, which was worse than that of Egypt and Tunisia, two neighboring countries who faced uprising before Libya.[61] This specific situation creates a wider contrast between good education, high demand for democracy, and the government's practices (perceived corruption, political system, supply of democracy).[59]

Much of the country's income from oil, which soared in the 1970s, was spent on arms purchases and on sponsoring militancy and terror around the world.[62][63]

Once a breadbasket of the ancient world, the eastern parts of the country became impoverished under Gaddafi's economic theories.[64][65]

Repressive system

Libya is the most censored country in the Middle East and North Africa, according to the Freedom of the Press Index.[66]

Gaddafi's Revolutionary committees resemble the systems of historical and current regimes and reportedly 10 to 20 percent of Libyans work in surveillance for these committees, a proportion of informants on par with Saddam Hussein's Iraq or Kim Jong-il's North Korea. The surveillance takes place in government, in factories, and in the education sector.[67]

Engaging in political conversations with foreigners is a crime punishable by three years of prison in most cases. Gaddafi removed foreign languages from school curriculum for a decade. One protester in 2011 described the situation as: "None of us can speak English or French. He kept us ignorant and blindfolded".[68][69]

Gaddafi has paid for murders of his critics around the world.[67][70] As of 2004, Libya still provides bounties for critics, including 1 million dollars for Ashur Shamis, a Libyan-British journalist.[71]

The regime has often executed opposition activists publicly and the executions are rebroadcast on state television channels.[67][72]

Early developments

Abu Salim prison is a high-security prison in Tripoli which human rights activists and other observers often describe as "notorious".[73][74][75] Amnesty International has called for an independent inquiry into deaths that occurred there in 1996,[76] an incident which Amnesty International and other news media refer to as the Abu Salim prison massacre.[77] Human Rights Watch believes that 1,270 prisoners were killed,[78][79] and calls it a "site of egregious human rights violations."[79]

On 24 January 2011, Libya blocked access to YouTube after it featured videos of demonstrations in the Libyan city of Benghazi by families of detainees who were killed in Abu Salim prison in 1996, and videos of family members of Gaddafi at parties. The blocking was criticized by Human Rights Watch.[80]

Between 13 and 16 January, upset at delays in the building of housing units and over political corruption, protesters in Darnah, Benghazi, Bani Walid and other cities broke into and occupied housing that the government was building.[81][82] By 27 January, the government had responded to the housing unrest with a US $24 billion investment fund to provide housing and development.[83]

In late January, Jamal al-Hajji, a writer, political commentator and accountant, "call[ed] on the internet for demonstrations to be held in support of greater freedoms in Libya" inspired by the Tunisian and Egyptian uprisings. He was arrested on 1 February by plain-clothes police officers, and charged on 3 February with injuring someone with his car. Amnesty International claimed that because al-Hajji had previously been imprisoned for his non-violent political opinions, the real reason for the present arrest appeared to be his call for demonstrations.[87]

In early February, Gaddafi had met with "political activists, journalists, and media figures" and "warned" them that they would be "held responsible" if they participated "in any way in disturbing the peace or creating chaos in Libya".[88]

Timeline of events

On 17 February, a "Day of Revolt" was called by Libyans.[89][90]

By the end of 23 February, headlines in online news services were reporting a range of themes underlining the precarious state of the regime – former justice minister Mustafa Mohamed Abud Al Jeleil alleged that Gaddafi personally ordered the 1988 Lockerbie bombing,[91] resignations and "defections" of close allies,[92] the loss of Benghazi, the second largest city in Libya, reported to be "alive with celebration"[93] and other cities including Tobruk and Misurata reportedly falling[94] with some believing that government had retained control of "just a few pockets",[92] mounting international isolation and pressure,[92][95] and reports that Middle East media consider the end of his "disintegrating"[96] regime all but inevitable.[96]

On 10 March, Zawiyah and Ra's Lanuf were retaken by loyalist forces.[97][98] Later on the 17th March the UN Security Council voted to imposed a no-fly zone in Libyan airspace[99], with British, French and Arab aircraft potentially launching airstrikes within hours of its imposition.

Protest movement's situation

Social activism

In Tobruk, volunteers turned a former headquarters of the regime into a center for helping protesters. Volunteers guard the port, local banks and oil terminals to keep the oil flowing. Teachers and engineers have set up a committee to collect weapons.[65] For many Libyans, the revolution was a watershed moment in their lives.[100]

After years of censorship, free speech is practiced for the first time. An opposition-controlled newspaper called Libya has appeared in Benghazi, as well as opposition-controlled radio stations.[101]

The movement opposes tribalism and defected soldiers wear vests bearing slogans such as "No to tribalism, no to factionalism".[65]

Libyans have entered abandoned torture chambers and found devices that have been used against opposition members in the past.[102]

Official organization

Many protest movement leaders have called for return to the 1952 constitution and transition to multiparty democracy. Military units who have joined the rebellion and many volunteers have formed an army to defend against Gaddafi's attacks and help liberate the capital Tripoli from his rule.[103]

The National Transitional Council (Arabic: المجلس الوطني الانتقالي) was a body established by opposition forces on 27 February in an effort to consolidate the anti-Gaddafi forces.[104] The main objectives of the group do not include forming an interim government, but instead to coordinate resistance efforts between the different towns held in rebel control, and to give a political "face" to the opposition to present to the world.[105] The council refers to the Libyan state as the Libyan Republic and it now has a website.[106] Traian Basescu, the president of Romania, said this Council is run by Kaddafi and its maximum role should be the one of interlocutor.

Gaddafi's former Justice Minister said in February that the new government will prepare for elections and they could be held in three months.[107]

Calls for international intervention

The Benghazi-based opposition government has called for a no-fly zone and airstrikes against the Gaddafi regime.[108]

A doctor at the general hospital in the city of Ajdabiyal said "we need medicine, we need food supplies and we need the international powers to stop his bombings so every day we do not face this".[108]

Gaddafi's situation

Gaddafi has attributed the protests against his rule to people who are "rats" and "cockroaches", those who have been influenced by hallucinogenic drugs put in drinks and pills. He specifically refers to substances in milk, coffee and Nescafe. He claims that Bin Laden and Al-Qaeda are distributing these hallucinogenic drugs. He also blames alcohol.[109][110][111][112]

Deaths and injuries

Independent numbers of dead and injured in the conflict have still not been made available. However, some conservative estimates have put the death toll at 1,000. Still, the International Federation for Human Rights have stated that the death toll could be as high as 3,000 by March 2. At the same time the opposition claimed that 6,500 people had died.[39] Among the dead, there have also been hundreds of members of both the rebel and government military forces. The numbers of injured have ranged from around 4,000[113] to 5,000.

Other humanitarian concerns

Medical supplies, fuel and food are running dangerously low in the country.[114] On 25 February, the International Committee of the Red Cross has launched an emergency appeal for US$6,400,000 to meet the emergency needs of people affected by the violent unrest in the country.[115] The Director General of the International Committee of the Red Cross reminded everyone taking part in the violence that health workers must be allowed to do their jobs safely.[116]

Fleeing the violence of Tripoli by road, as many as 4,000 people have been crossing the Libya-Tunisia border daily during the first days of the uprising. Among those escaping the violence are foreign nationals including Egyptians, Tunisians, and Turks, as well as Libyans.[117] Officials from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees confirmed allegations of discrimination against sub-Saharan Africans who were held in dangerous conditions in the no-man's-land between Tunisia and Libya.[118] By 3 March, an estimated 200,000 refugees had fled Libya to either Tunisia or Egypt. A provisional refugee camp was set up at Ras Ajdir with a capacity for 10,000 was overflowing with an estimated 20,000 to 30,000 refugees. Many tens of thousands are still trapped on the Libyan side of the frontier. The situation is described as a logistical nightmare, with the World Health Organization warning of the risk of epidemics.[119]

With a migrant population of about two million, countries that border Libya, especially Egypt and Tunisia, have been receiving a flow of migrants and nationals escaping the violence. Migrants workers as well as Libyan nationals have been finding their way to the border cities of Sallum in Egypt and Ras Ajdir in Tunisia creating a humanitarian crisis. According to the International Organization for Migration (IOM) as of 7 March 2011, 115,399 migrants arrived in Tunisia (19,184 of them Tunisians, 47,631 Egyptians and the rest from various nationalities), 101,609 in Egypt (of which 65,509 were Egyptian), 2,205 in Niger (1,865 Nigeriens) and 5,448 in Algeria[120].

Domestic responses

Several officials resigned from their positions after 20 February in large part due to protests against the army's "excessive use of force", including justice minister Mustafa Mohamed Abud Al Jeleil as well as Interior Minister and Major General Abdul Fatah Younis,[121] whereas Oil Minister Shukri Ghanem was reported to have fled the country.[122] Citing "grave violations of human rights", Gaddafi's cousin and close aid, Ahmad Qadhaf al-Dam, announced his defection from the government when he arrived in Egypt on 24 February.[123]

Several members of the diplomatic corps also resigned. Amongst these were the ambassadors to the Arab League,[124] Bangladesh, the People's Republic of China,[125] the European Union and Belgium,[126] India,[127] Indonesia,[122] Nigeria, Sweden and the United States. The deputy ambassador to the United Nations Ibrahim Omar Al Dabashi did not resign but distanced himself from the Libyan government's actions.[128][129] The ambassador to the United States Ali Aujali together with the embassy staff also distanced himself from the government, "condemned" the violence and urged the international community (QTO STOP THE KILLINGS.) The ambassador to the United Kingdom denied reports that he had resigned.[122]

The Arabian Gulf Oil Company, the second largest state-owned oil company in Libya, announced plans to use oil funds to support anti-Gaddafi forces.[130] This will prove a major boost for the embattled rebel forces highly low on funds.

Two Libyan Air Force pilots[citation needed] and a naval vessel fled to Malta, reportedly claiming to have refused orders to bomb protesters in Benghazi.[131][132]

Islamic leaders and clerics in Libya, notably the Network of Free Ulema – Libya urged all Muslims to rebel against Gaddafi.[122][133] The Warfalla, Tuareg and Magarha tribes have announced their support of the protesters.[24][134] The Zuwayya tribe, based in eastern Libya, have threatened to cut off oil exports from fields in their part of the country if Libyan security forces continued attacking demonstrators.[135]

Youssef Sawani, a senior aide to Muammer Gaddafi's son Saif al-Islam Gaddafi, resigned from his post "to express dismay against violence".[24]

On 28 February, Gaddafi reportedly appointed the head of Libya's foreign intelligence service to speak to the leadership of the anti-government protesters in the east of the country.[136]

Libyan-throne claimant, Muhammad as-Senussi, sent his condolences "for the heroes who have laid down their lives, killed by the brutal forces of Gaddafi" and called on the international community "to halt all support for the dictator with immediate effect."[138] as-Senussi said that the protesters would be "victorious in the end" and calls for international support to end the violence.[139] On 24 February, as-Senussi gave an interview to Al Jazeera English where he called upon the international community to help remove Gaddafi from power and stop the ongoing "massacre".[140] He has dismissed talk of a civil war saying "The Libyan people and the tribes have proven they are united". He later stated that international community needs "less talk and more action" to stop the violence.[141] He has asked for a no-fly zone over Libya but does not support foreign ground troops.[142] In an interview with Adnkronos, Idris al-Senussi, a pretender to the Libyan throne, announced he was ready to return to the country once change had been initiated.[143] On 21 February 2011, Idris made an appearance on Piers Morgan Tonight to discuss the uprising.[144] On 3 March, it was reported that Prince Al Senussi Zouber Al Senussi had fled Libya with his family and was seeking asylum in Totebo, Sweden.[145]

International reactions

Condemnation and sanctions

Many[who?] states and supranational bodies condemned Gaddafi's use of military and mercenaries against Libyan civilians. However, Nicaraguan President Daniel Ortega, Cuban political leader Fidel Castro and Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez all expressed support for Gaddafi.[146][147][148] Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi initially said he did not want to disturb Gaddafi, but two days later the called the attacks on protesters unacceptable.[149][150]

After an emergency meeting on 22 February, the Arab League suspended Libya from taking part in council meetings and issued a statement condemning the "crimes against the current peaceful popular protests and demonstrations in several Libyan cities".[151][152] Libya was suspended from the United Nations Human Rights Council by a unanimous vote of the UN General Assembly, citing the Gaddafi government's use of violence against protesters.[153]

On 26 February, the UN Security Council voted unanimously to impose strict sanctions, including targeted travel bans, against Gaddafi's government, as well as to refer Gaddafi and other members of his regime to the International Criminal Court for investigation into allegations of brutality against civilians, which could constitute crimes against humanity in violation of international law.[154] Interpol issued a security alert concerning the "possible movement of dangerous individuals and assets" based on the UN Security Council Resolution 1970, listing Gaddafi himself and fifteen members of his clan or his regime.[155] A number of governments, including Britain, Canada, Switzerland, the United States, Germany and Australia took action to freeze assets of Gaddafi and his associates.[156]

The Gulf Cooperation Council issued a joint statement on 8 March, calling on the UN Security Council to impose an air embargo on Libya to protect civilians.[157] The Arab League did the same on 12 March, with only Algeria and Syria voting against the measure.[158]

Evacuations

During the uprising, many countries evacuated their citizens.[159][160][161] A number of international oil companies decided to withdraw their employees from Libya to ensure their safety, including Gazprom, Royal Dutch Shell, Sinopec, Suncor Energy, Pertamina and BP. Other companies that decided to evacuate their employees included Siemens and Russian Railways.[162][163]

China set up its largest evacuation operation ever with over 30,000 Chinese nationals evacuated within a nine-day emergency operation.[164] China also managed to evacuate an additional group of 2,100 citizens from twelve other countries.[165][166]

On 25 February, 500 passengers, mostly Americans, sailed into Malta after a rough eight-hour journey from Tripoli following a two-day wait for the seas to calm.[167]

The United Kingdom deployed aircrafts and the frigate HMS Cumberland to assist in the evacuation of its citizens and other nationals.[168][169][170]

China's frigate Xuzhou of the People's Liberation Army Navy was ordered to guard the Chinese evacuation efforts.[165][171]

Ireland dispatched two Irish Air Corps planes to evacuate Irish citizens from Libya, but these returned on 24 February without passengers after Libyan security officials prevented them from evacuating passengers. The Irish Department of Foreign Affairs assisted over 115 Irish nationals in leaving Libya.[172] An Irish Air Corps Learjet later flew seven Irish evacuees from Malta to Casement Aerodrome, a military airbase in Ireland.[173]

On the evening of 25 February, the United Kingdom and Germany launched a joint evacuation operation, involving two Royal Air Force transport planes with British Special Forces on board and two Luftwaffe Transall C-160 transport planes, with elite Fallschirmjäger on board. The planes evacuated 22 Germans and about 100 other Europeans, mostly British oil workers from the airport at Nafurah to Crete.[174][175][176]

On 26 February, the Indian government launched Operation Safe Homecoming to evacuate its citizens out of Libya. It involved ships of the Indian Navy, two charted ships, aircraft of the Indian Air Force,[177] Air India, Jet Airways and Kingfisher Airlines. These operations were expected to continue until 12 March.[178][179]

On 27 February, two Royal Air Force C-130 Hercules aircraft with British Special Forces onboard evacuated approximately 100 foreign nationals, mainly oil workers, to Malta from the desert south of Benghazi,[180][181] one of which was shot at and suffered some damage, but no one was injured.[182]

On the afternoon of 27 February, a Lynx helicopter from the Royal Netherlands Navy frigate HNLMS Tromp attempted to evacuate a Dutch civilian and another European from the coastal city of Sirt. The attempt failed and the helicopter and its crew of three Dutch navy soldiers were apprehended by Libyan forces loyal to Gaddafi, while the two civilians were handed over to the Dutch embassy in Tripoli. The Libyan state television showed a video of the Dutch soldiers and the helicopter and announced that the soldiers are accused of "breaching international law" since they had infiltrated Libyan airspace without clearance. After negotiations with the Gaddafi regime, the crew was released on 11 March and flown to Athens, Greece, by the Greek military. However, the regime held on to the crew's helicopter.[183][184][185][186][187]

On 1 March, the South Korean Navy destroyer ROKS Choi Young arrived off the coast of Tripoli to evacuate South Korean citizens from Libya.[188] By this point, 12,000[clarification needed] had been evacuated from Libya to Malta, 3,000 of them by airplane to Malta International Airport, near Luqa, and the rest by ferries to Floriana, Valletta, Marsa and Pietà, Malta.[189][190]

On 2 March, the UK Royal Navy destroyer HMS York docked in the port of Benghazi, evacuated 43 nationals, and delivered medical supplies and other humanitarian aid donated by the Swedish government.[191][192] On the same day, the Canadian Navy frigate HMCS Charlottetown left its home port of Halifax, Nova Scotia, to aid in the evacuation of Canadian citizens and to provide humanitarian relief operations in conjunction with an US Navy carrier strike group, led by the nuclear-powered aircraft carrier USS Enterprise.[193]

Mediation proposals

There have been several peace mediation prospects during the crisis.

There was some speculation that Tony Blair, a former British Prime Minister who had dealings with Gaddafi in the last few years, would mediate the crisis. Blair instead tried to downplay his dealings with Libyan regime and turned his back on Gaddafi.[194]

The South African government proposed an African Union-led mediation effort to prevent "civil war".[195]

Another initiative came from Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez. Although Gaddafi accepted in principle a proposal by Chávez to negotiate a settlement between the opposition and the Libyan government, Saif al-Islam Gaddafi, Gaddafi's son, later voiced some skepticism to the proposal.[citation needed] On news of Gaddafi in principle accepting the Chávez's proposal for international mediation, there was a worldwide decrease in oil and gold prices.[196] The proposal has also been under consideration by the Arab League, according to its Secretary-General Amr Moussa.[197] The Libyan opposition was cold to the proposal, saying that while they are willing to save lives, any deal would have to involve Gaddafi stepping down, while the US and French governments dismissed any initiative that would allow Gaddafi to remain in power.[198]

British abortive mission

A group of eight British people, six Special Air Service soldiers escorting two junior diplomats, who came to establish contacts with the opposition, were captured by opposition forces near Benghazi, and after intervention of British government, released on March 6.[199] The team was reportedly carrying weapons, explosives and a number of different passports. [200]

No-fly zone

On February 28, the UK Prime Minister David Cameron proposed the idea of a no-fly zone to prevent Gaddafi from airlifting mercenaries and using his military aeroplanes and armoured helicopters against civilians.[201] Italy said it would support a no-fly zone if it was backed by the United Nations.[202] US Secretary of Defense Robert Gates has been skeptical of this option, warning the US Congress that a no-fly zone would have to begin with an attack on Libya's air defenses.[203] This proposal was rejected by Russia and China.[204][205][206][207] Romania is utterly against the initiation of a no fly zone. "Among the arguments I want to bring in order to support our position is that this mission of initiating a no fly zone is a mission that only NATO can have and not the EU. We also consider it is not the moment for a military solution in Libya," said Romanian President Traian Băsescu at the EU summit on 11 March.

On 7 March, US Permanent Representative to NATO Ivo Daalder announced that NATO decided to step up surveillance missions to twenty-four hours a day. On the same day, it was reported that one UN diplomat confirmed to Agence France-Presse on condition of anonymity that France and Britain were drawing up a resolution on the no-fly zone and it go before the UN Security Council as early as this week.[177][208][209]

On 12 March, the foreign ministers of the Arab League agreed to ask the UN to impose a no-fly zone over Libya. That brought a joint NATO/Arab-enforced fly-zone closer to establishment.[177] The rebels have stated that a no-fly zone alone would not be enough, because the majority of the bombardment is coming from things other than aircraft – particularly tanks and rockets. [210]

On March 17, 2011, the United Nations Security Council approved a no-fly zone, amongst other measures, by a vote of 10 in favor, zero against, and five abstentions. The resolution authorizes member states 'to take all necessary measures… to protect civilians and civilian populated areas under threat of attack in the Libyan Arab Jamhariya, including Benghazi, while excluding an occupation force'.Cite error: The <ref> tag has too many names (see the help page).[211]

Although the no fly zone is immediately enforcable, and several countries have prepared to take immediate action, it is unclear how long the operation will take to enforce the measures. Some reports state this could be 'within hours', wheras previous repports hinted at several days. Which nations and their roles in applying these measures thave not yet been specified, although France and the UK have stated their intention to uphold them as a matter of urgency, and Lebanon and the US heavily backed the resolution.[212]

See also

- 2011 Egyptian revolution

- International reactions to the 2011 Libyan uprising

- Jasmine Revolution

- List of conflicts in the Maghreb

References

- ^ "Ferocious Battles in Libya as National Council Meets for First Time". News. 6 March 2011.

- ^ "Libya's Tribal Revolt May Mean Last Nail in Coffin for Qaddafi". BusinessWeek. Retrieved 25 February 2011.

- ^ a b c "Libya crisis: Britain, France and US prepare for air strikes against Gaddafi". The Guardian. 17 March 2011. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- ^ Dewitte, Lieven (16 March 2011). "Danish F-16s readied to enforce a Libyan no-fly zone". F-16.net. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- ^ a b c "UN Security Council approves no-fly zone resolution for Libya". Herald Sun. 18 March 2011. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- ^ "Egyptian Special Forces Secretly Storm Libya". Daily Mirror. 3 March 2011.

- ^ WSJ Article]

- ^ "Rebels Fear Other Regimes Are Throwing Support Behind Gadhafi's Forces". The Globe and Mail. 14 March 2011. Retrieved 15 March 2011.

- ^ Richard Norton-Taylor (22 october2011). "Libya Received Military Shipment from Belarus, Claims EU Arms Watchdog". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 March 2011.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Syrian Pilots Said To Be Flying Libyan Fighter Jets". Press TV. 10 March 2011. Retrieved 11 March 2011.

- ^ "Mugabe manda a mercenarios en apoyo del régimen de Gadafi, según un rotativo" (in Castillian). ABC. 27 February 2011. Retrieved 11 March 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "Rebels Forced from Libyan Oil Port". BBC News. 10 March 2011.

- ^ "Libya's Opposition Leadership Comes into Focus". Business Insider. Stratfor. 8 March 2011. Retrieved 9 March 2011.

- ^ http://english.aljazeera.net/news/africa/2011/03/201131542757285681.html#

- ^ "Gadhafi showers strategic oil port with rockets". 10 March 2011. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- ^ "Battle Rages over Libyan Oil Port". Al Jazeera English. Retrieved 3 March 2011.

- ^ "Gaddafi's Military Capabilities". Al Jazeera English. Retrieved 4 March 2011.

- ^ "Libya: UN Appoints Envoy and Agrees to Humanitarian Visit". BBC News. 7 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (2 March 2011). "RT News Line, March 2". RT. Retrieved 15 March 2011.

- ^ http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/blog/2011/mar/10/libya-uprising-gaddafi-live#block-15

- ^ http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/blog/2011/mar/10/libya-uprising-gaddafi-live#block-15

- ^ "Death Toll in Libyan Popular Uprising at 10000". Irib. Retrieved 7 March 2011.

- ^ Shadid, Anthony (18 February 2011). "Libya Protests Build, Showing Revolts' Limits". The New York Times. Retrieved 22 February 2011.

- ^ a b c "Gaddafi Defiant as State Teeters". Africa. Al Jazeera English. 23 February 2011. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ^ "Middle East and North Africa Unrest". BBC News. 24 February 2011. Retrieved 24 February 2011.

- ^ "Free Press Debuts in Benghazi". Magharebia. 28 February 2011. Retrieved 3 March 2011.

- ^ Timpane, John (28 February 2011). "Twitter and Other Services Create Cracks in Gadhafi's Media Fortress". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved 3 March 2011.

- ^ "Libya Protests: Gaddafi Embattled by Opposition Gains". BBC News. 24 February 2011.

- ^ "Libya's Bloody Rebellion Turns into Civil War". Irish Independent. 6 March 2011. Retrieved 6 March 2011.

- ^ "World Powers Edge Closer to Gadhafi Solution". The Vancouver Sun. 28 February 2011. Retrieved 3 March 2011.

- ^ "Ghaddafi's Control Reduced to Part of Tripoli". afrol News. 27 February 2011.

- ^ "Experts Disagree on African Mercenaries in Libya". Voice of America. 1 March 2011. Retrieved 3 March 2011.

- ^ a b Casey, Nicholas; de Córdoba, José (26 February 2011). "Where Gadhafi's Name Is Still Gold". The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ Wyatt, Edward (26 February 2011). "Security Council Calls for War Crimes Inquiry in Libya". The New York Times. Retrieved 27 February 2011.

- ^ "Chinchilla Blasts Ortega for Gadhafi Support". The Tico Times.

- ^ "Humala Criticizes Chavez for Supporting Gaddafi". Living in Peru. Retrieved 28 February 2011.

- ^ "Jewish Group Slams 'Solidarity' with Gadhafi". Fox News. 1 February 2010. Retrieved 28 February 2011.

- ^ Brown, Cameron S. "Wiesenthal Center Slams 'Solidarity' with Gaddafi". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 28 February 2011.

- ^ a b "Libya Received Military Shipment from Belarus, Claims EU Arms Watchdog". The Guardian. 1 March 2011. Cite error: The named reference "autogenerated3" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ "Belarus Sends Arms to Libya". The Daily Telegraph. 1 March 2011.

- ^ "France Supports Libya Rebel Council". Al Jazeera English. 10 March 2011.

- ^ "Al Qaeda Fighting with Rebels in Libya?". The World Reporter. 13 March 2011.

- ^ "Now Gaddafi Blames Hallucinogenic Pills Mixed with Nescafe and bin Laden for Uprisings... Before Ordering Bloody Hit on a Mosque". Daily Mail. 25 February 2011.

- ^ "Gaddafi Says Protesters Are on Hallucinogenic Drugs". Reuters. 24 February 2011.

- ^ "Gaddafi Blames Uprising on al-Qaeda". Al Jazeera English. 24 February 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (9 March 2011). "Gadhafi: US, Britain, France Conspiring To Control Libya Oil – Spokesman for Rebel National Libyan Council Says Victory Against Libya's Longtime Leader Will Only Come When Rebels Get a No-Fly Zone, an Issue That Western Nations Are Seriously Debating". Haaretz. Retrieved 11 March 2011.

- ^ "Gadhafi: 'People Who Don't Love Me Don't Deserve To Live'". The News Journal. 26 February 2011.

- ^ "Gaddafi: 'I Will Not Give Up', 'We Will Chase the Cockroaches'". The Times. 22 February 2010.

- ^ "Three Scenarios for End of Gaddafi: Psychologist". Al Arabiya. 26 February 2011.

- ^ "Gaddafi Warns of al-Qaeda Spread 'Up to Israel'". Al Arabiya.

- ^ Viscusi, Gregory (23 February 2011). "Qaddafi Is No Mubarak as Regime Overthrow May Trigger a 'Descent to Chaos'". Bloomberg. Retrieved 12 March 2011.

- ^ Mills, Robin (22 February 2011). "Qaddafi Remains One of Few Constants for Troubled Libya". The National. Retrieved 12 March 2011.

The one constant is Qaddafi himself, the world's longest-serving non-royal head of state, having outlasted another oil potentate, Gabon's Omar Bongo, who died in 2009

- ^ a b Whitlock, Craig (22 February 2011). "Gaddafi Is Eccentric But the Firm Master of His Regime, Wikileaks Cables Say". The Washington Post. Retrieved 12 March 2011.

- ^ Silver, Nate (31 January 2011). "Egypt, Oil and Democracy". FiveThirtyEight: Nate Silver's Political Calculus. (blog of The New York Times). Retrieved 12 March 2011.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Ali Alayli, Mohammed (4 December 2005). "Resource Rich Countries and Weak Institutions: The Resource Curse Effect" (PDF). Berkeley University. Retrieved 22 February 2011.

- ^ More Killed in Libya Crackdown (Television news production). ITN News via YouTube. 15 February 2011. Retrieved 25 February 2011.

- ^ Solomon, Andrew (21 February 2011). "How Qaddafi Lost Libya". News Desk (blog of The New Yorker). Retrieved 12 March 2011.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Staff writer (2 March 2009). "Libya's Jobless Rate at 20.7 Percent: Report". Reuters. Retrieved 12 March 2011.

- ^ a b Maleki, Ammar (9 February 2011). "Uprisings in the Region and Ignored Indicators". Payvand.

- ^ Kanbolat, Hasan (22 February 2011). "Educated and Rich Libyans Want Democracy". Today's Zaman. Retrieved 12 March 2011.

- ^ "Corruption Perceptions Index 2010 Results". Corruption Perceptions Index. Transparency International. Retrieved 22 February 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (24 February 2011). "Endgame in Tripoli – The Bloodiest of the North African Rebellions So Far Leaves Hundreds Dead". The Economist. Retrieved 12 March 2011.

- ^ Simons, Geoffrey Leslie (1993). Libya – The Struggle for Survival. St. Martin's Press (New York City). p. 281. ISBN 978-0-312-08997-9.

- ^ Staff writer (3 March 2011). "A Civil War Beckons – As Muammar Qaddafi Fights Back, Fissures in the Opposition Start To Emerge". The Economist. Retrieved 12 March 2011.

- ^ a b c Staff writer (24 February 2011). "The Liberated East – Building a New Libya – Around Benghazi, Muammar Qaddafi's Enemies Have Triumphed". The Economist. Retrieved 12 March 2011.

- ^ "Freedom of the Press 2009" (PDF). Freedom House. Retrieved 7 May 2009.

- ^ a b c Eljahmi, Mohamed (2006). "Libya and the U.S.: Qadhafi Unrepentant". Middle East Quarterly.

- ^ "Building a new Libya". The Economist. 24 February 2011.

- ^ Black, Ian (10 April 2007). "Libyans Are Queuing Up To Learn English". The Guardian. Retrieved 6 March 2011.

- ^ The Middle East and North Africa 2003 (2002). Eur. p. 758

- ^ "Gadaffi Still Hunts 'Stray Dogs' in UK". The Guardian. 28 March 2004.

- ^ Davis, Brian Lee. Qaddafi, Terrorism, and the Origins of the U.S. Attack on Libya.

- ^ "Libya's Notorious Abu Salim Prison To Be Emptied" (Archived material, restricted to regulars and members). Rantburg. 24 March 2010. Retrieved 25 February 2011. in "Libya's Notorious Abu Salim Prison To Be Emptied". daylife.com. 24 March 2010. Retrieved 25 February 2011.

- ^ "Libya's Notorious Abu Salim Prison". geneva lunch.

- ^ Robertson, Nic; Cruickshank, Paul (28 November 2009). "Jihadist Death Threatened Libyan Peace Deal". CNN. Retrieved 11 March 2011.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Investigation Needed into Prison Deaths". Amnesty International.

- ^ "Libyan Legal Court Celebrates Abu Salim Prison Massacre". Arabic News. 24 June 2005.

- ^ "Site News Bilal bin Rabah (the city of Al Bayda, Libya), a Meeting with the Libyan Minister of Justice". Binrabah.com. Retrieved 25 February 2011.

- ^ a b "Libya: Free All Unjustly Detained Prisoners". Human Rights Watch.

- ^ "Watchdog Urges Libya To Stop Blocking Websites". Agence France-Presse. Retrieved 7 February 2010.

- ^ "Libyans Protest over Delayed Subsidized Housing Units". 16 January 2011.

- ^ Mohamed, Abdel-Baky (16 January 2011). "Libya Protest over Housing Enters Its Third Day".

- ^ Karam, Souhail (27 January 2011). "Libya Sets Up $24 Bln Fund for Housing". Reuters. Retrieved 6 March 2011.

- ^ Landay, Janathan S.; Strobel, Warren P.; Ibrahim, Arwa (18 February 2011). "Violent Repression of Protests Rocks Libya, Bahrain, Yemen". McClatchy Newspapers. Retrieved 15 March 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Tran, Mark (17 February 2011). "Bahrain in Crisis and Middle East Protests – Live Blog". The Guardian. Retrieved 19 February 2011.

- ^ SignalFire (23 February 2011). "Clampdown in Libyan Capital as Protests Close In". SignalFire. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ^ "Libyan Writer Detained Following Protest Call". Amnesty International. 8 February 2011. Archived from the original on 8 February 2011. Retrieved 8 February 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Mahmoud, Khaled (9 February 2011). "Gaddafi Ready for Libya's 'Day of Rage'". Asharq al-Awsat. Archived from the original on 10 February 2011. Retrieved 10 February 2011.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Staff writer (4 February 2011). "Calls for Weekend Protests in Syria – Social Media Used in Bid To Mobilise Syrians for Rallies Demanding Freedom, Human Rights and the End to Emergency Law". Al Jazeera English. Archived from the original on 8 February 2011. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Debono, James (9 February 2011). "Libyan Opposition Declares 'Day of Rage' Against Gaddafi". Malta Today. Archived from the original on 10 February 2011. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Staff writer (24 February 2011). "Muammar Gaddafi Ordered Lockerbie Bombing, Says Libyan Minister". News Limited. Retrieved 17 March 2011. – citing an original interview with Expressen in Sweden: Julander, Oscar; Hamadé, Kassem (23 February 2011). "Khadaffi gav order om Lockerbie-attentatet". Expressen (in Swedish). Retrieved 17 March 2011.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) English translation - ^ a b c "Pressure mounts on isolated Gaddafi". BBC News. 23 February 2011. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ^ Dziadosz, Alexander (23 February 2011). "Benghazi, Cradle of Revolt, Condemns Gaddafi". Reuters (via The Star). Retrieved 17 March 2011.

The eastern city of Benghazi... was alive with celebration on Wednesday with thousands out on the streets, setting off fireworks

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Staff writer (24 February 2011). "Gaddafi Loses More Libyan Cities – Protesters Wrest Control of More Cities as Unrest Sweeps African Nation Despite Muammar Gaddafi's Threat of Crackdown". Al-Jazeera. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (23 February 2011). "Protesters Defy Gaddafi as International Pressure Mounts (1st Lead)". Deutsche Presse-Agentur (via Monsters and Critics). Retrieved 17 March 2011.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b Staff writer (23 February 2011). "Middle Eastern Media See End of Gaddafi". BBC News. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (10 March 20110). "Libya's Zawiyah Back under Kadhafi Control: Witness". Agence France-Presse (via Google News). Retrieved 17 March 2011.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help). - ^ Staff writer (11 March 2011). "Gaddafi Loyalists Launch Offensive – Rebel Fighters Hold Only Isolated Pockets of Oil Town after Forces Loyal to Libyan Leader Attack by Air, Land and Sea". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-12781009

- ^ Staff writer (3 March 2011). "Libya: A State of Terror – As Gaddafi Wages War Against a Popular Uprising, Libyan Exiles Explain How Terror Has Long Been a Tool of the Regime". Al Jazeera English. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (25 February 2011). "New Media Emerge in 'Liberated' Libya". BBC News. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (1 March 2011). "Evidence of Libya Torture Emerges – As the Opposition Roots Through Prisons, Fresh Evidence Emerges of the Government's Use of Torture". Al Jazeera English. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- ^ Gillis, Clare Morgana (4 March 2011). "In Eastern Libya, Defectors and Volunteers Build Rebel Army". The Atlantic. Retrieved 12 March 2011.

- ^ Golovnina, Maria (28 February 2011). "World Raises Pressure on Gaddafi". National Post. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (27 February 2011). "Libya Opposition Launches Council – Protesters in Benghazi Form a National Council 'To Give the Revolution a Face'". Al Jazeera English. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (undated). "The Council's Statement". National Transitional Council. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Staff writer (27 February 2011). "Libyan Ex-Minister Wants Election". Sky News Business Channel. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- ^ a b Sengupta, Kim (11 March 2011). "Why Won't You Help, Libyan Rebels Ask West". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- ^ "Now Gaddafi Blames Hallucinogenic Pills Mixed with Nescafe and bin Laden for Uprisings... Before Ordering Bloody Hit on a Mosque". Daily Mail. 25 February 2011.

- ^ "Gaddafi Says Protesters Are on Hallucinogenic Drugs". Reuters. 24 February 2011.

- ^ "Kadhafi Says Al-Qaeda Behind Insurrection". Yahoo! News. 24 February 2011.

- ^ "Yemen Blames Israel and US; Qaddafi Accuses US – and al-Qaeda". Arutz Sheva. 2 March 2011.

- ^ "Live Blog – Libya". Blogs. Al Jazeera. 22 February 2 011. Retrieved 22 February 2 011.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ "Libya's Humanitarian Crisis". Al Jazeera English. 28 February 2011.

- ^ "Libya: ICRC Launches Emergency Appeal as Humanitarian Situation Deteriorates" (Press release). International Committee of the Red Cross. 25 February 2011. Retrieved 3 March 2011.

- ^ "Libya: Poor Access Still Hampers Medical Aid to West" (Press release). International Committee of the Red Cross. 3 March 2011. Retrieved 3 March 2011.

- ^ "Live Update: Thousands Flee Across Libya-Tunisia Border". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 24 February 2011.

- ^ Saunders, Doug (1 March 2011). "At a Tense Border Crossing, a Systematic Effort To Keep Black Africans Out". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 3 March 2011.

- ^ Sayar, Scott; Cowell, Alan (3 March 2011). Libyan Refugee Crisis Called a 'Logistical Nightmare'". The New York Times.

- ^ "Statistics of IOM Operations in Egypt – 8 March 2011". UN Egypt. 8 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (21 February 2011). "Libya Justice Minister Resigns To Protest 'Excessive Use of Force' Against Protesters – Ambassadors to the Arab League, India and China Have Also Stepped Down To Voice Dissent with the Government, as Violent Clashes Spill into Seventh Day". Reuters (via Haaretz). Retrieved 17 March 2011.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b c d Staff writer (17 February 2011). "Live Blog – Libya". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (24 February 2011). "Libya: Obama Seeks Consensus on Response to Violence". BBC News. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (21 February 2011). "Libya's Ambassadors to India, Arab League Resign in Protest Against Government". RIA Novosti. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (21 February 2011). "Libyan Diplomat in China Resigns over Unrest: Report". Agence France-Presse (via Google News). Retrieved 17 March 2011.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Almasri, Mohammed (21 February 2011). "Libyan Ambassador to Belgium, Head of Mission to EU Resigns". Global Arab Network. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ "Libya's Ambassador to India Resigns in Protest Against Violence: BBC". Diligent Media Corporation Ltd. 21 February 2011. Retrieved 21 February 2011.

- ^ Lederer, Edith M. (2011). "The Canadian Press: Libya's UN diplomats Are Calling for Leader Col. Moammar Gadhafi To Step Down". Google. Retrieved 21 February 2011.

- ^ "Libya: UN Diplomats Resign in Protest". Babylon & Beyond (blog of the Los Angeles Times). 21 February 2011 9h26 am. Retrieved 21 February 2011.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Libya's Arabian Gulf Oil Co Hopes To Fund Rebels Via Crude Sales-FT". Reuters.

- ^ "N. Africa, Mideast protests — Gadhafi: I'm Still Here". CNN. 21 February 2011. Retrieved 22 February 2011.

- ^ "Libya: Warship Defects to Malta". Babylon & Beyond (blog of the Los Angeles Times). 22 February 2011. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Update 1-Libyan Islamic Leaders Urge Muslims To Rebel". Reuters. 9 February 2011. Retrieved 21 February 2011.

- ^ "Libya Crisis: What Role Do Tribal Loyalties Play?". BBC News.

- ^ Hussein, Mohammed (22 February 2011). "Libya Crisis: What Role Do Tribal Loyalties Play?". BBC News.

- ^ "Gaddafi Aide 'To Talk to Rivals'". Al Jazeera English. 28 February 2011. Retrieved 28 February 2011.

- ^ "The Liberated East: Building a New Libya". The Economist. 24 February 2011. Retrieved 26 February 2011.

- ^ Salama, Vivian (22 February 2011). "Libya's Crown Prince Says Protesters Will Defy 'Brutal Forces'". Bloomberg. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ [dead link] "Gaddafi Nears His End, Exiled Libyan Prince Says". Yahoo! News. Retrieved 24 February 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (24 February 2011). "Libya's 'Crown Prince' Makes Appeal – Muhammad al-Senussi Calls for the International Community To Help Remove Muammar Gaddafi from Power". Al Jazeera English. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (9 March 2011). "Libya's 'Exiled Prince' Urges World Action". Agence France-Presse (via Khaleej Times). Retrieved 17 March 2011.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Johnston, Cynthia (9 March 2011). "Libyan Crown Prince Urges No-Fly Zone, Air Strikes". Reuters. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ [clarification needed] Staff writer (16 February 2011). "Libia, principe Idris: "Gheddafi assecondi popolo o il Paese finirà in fiamme"". Adnkronos (in Italian). Retrieved 17 March 2011.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|trans_title=(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Krakauer, Steve (21 February 2011). "Who Is Moammer Gadhafi? Piers Morgan Explores the Man at the Center of Libya's Uprising". Piers Morgan Tonight (blog of Piers Morgan Tonight via CNN). Retrieved 17 March 2011.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Staff writer (3 March 2011). "Libyan Royal Family Seeking Swedish Asylum". Tidningarnas Telegrambyrå (via Stockholm News). Retrieved 17 March 2011.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Staff writer (22 February 2011). "Libya Live Report". Agence France-Presse (via Yahoo! News). Retrieved 17 March 2011.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Varas, Arturo (25 February 2011). "Chavez Joins Ortega and Castro To Support Gaddafi". Ecuador Times. Retrieved 15 March 2011.

- ^ Cárdenas, José R. (24 February 2011). "Libya's Relationship Folly with Latin America". Shadow Government (blog of Foreign Policy). Retrieved 17 March 2011.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Babington, Deepa (20 February 2011). "Berlusconi Under Fire for Not 'Disturbing' Gaddafi". Reuters. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (21 February 2011). "As It Happened: Mid-East and North Africa Protests". BBC News. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ Perry, Tom (21 February 2011). "Arab League 'Deeply Concerned' by Libya Violence". Reuters. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ Galal, Ola (22 February 2011). "Arab League Bars Libya From Meetings, Citing Forces' 'Crimes'". Bloomberg. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (2 March 2011). "Libya Suspended from Rights Body – United Nations General Assembly Unanimously Suspends Country from UN Human Rights Council, Citing 'Rights Violations'". Al Jazeera English. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (26 February 2011). "U.N. Security Council Slaps Sanctions on Libya – Resolution Also Calls for War Crimes Inquiry Over Deadly Crackdown on Protesters". MSNBC. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ Press release (4 March 2011). "File No.: 2011/108/OS/CCC" (PDF format (183 KB); requires Adobe Reader). Interpol. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (28 February 2011). "Gaddafi Sees Global Assets Frozen – Nations Around the World Move To Block Billions of Dollars Worth of Assets Belonging to Libyan Leader and His Family". Al Jazeera English. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ Press release (8 March 2011). "Joint Statement of the Joint Ministerial Meeting of the Strategic Dialogue Between the Countries of the Cooperation Council for the Arab Gulf States and Australia" (in Arabic; Google Translate translation). Gulf Cooperation Council. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (12 March 2011). "Arab League Backs Libya No-Fly Zone". BBC News. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (25 February 2011). "Libya Protests: Evacuation of Foreigners Continues". BBC News. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (24 February 2011). "Grounded Flight Leaves Canadians Stranded in Libya". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (undated). "Greeks Evacuated from Libya Return Safely". ANA-MPA. Retrieved 15 March 2011.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Staff writer (22 February 2011). "Foreigners in Libya". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (27 February 2011). "Libya: Maltese Wishing To Stay Urged To Change Their Mind". The Times. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (3 March 2011). "China's Libya Evacuation Highlights People-First Nature of Government". Xinhua News Agency. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- ^ a b Staff writer (3 March 2011). "35,860 Chinese Nationals in Libya Evacuated: FM". Xinhua News Agency. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- ^ Krishnan, Ananth (28 February 2011). "Libya Evacuation, a Reflection of China's Growing Military Strength". The Hindu. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (25 February 2011). "Evacuees Arrive in Grand Harbour, Speak of Their Experiences – Smooth Welcoming Operation". The Times. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (22 February 2011). "Libya Unrest: UK Plans To Charter Plane for Britons". BBC News. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (24 February 2011). "Britons Flee Libya on Navy Frigate Bound for Malta". BBC News. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (26 February 2011). "RAF Hercules Planes Rescue 150 from Libya Desert". BBC News. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (3 March 2011). "35,860 Chinese Nationals Evacuated from Unrest-Torned Libya". Xinhua News Agency. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (1 March 2011). "Department Defends Libyan Evacuation". The Irish Times. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (26 February 2011). "Air Corps Flies Irish Evacuees From Libya to Baldonnel". Merrion Street (news service of Government of Ireland). Retrieved 16 March 2011.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ Helm, Toby; Townsend, Mark; Harris, Paul (26 February 2011). "Libya: Daring SAS Mission Rescues Britons and Others from Desert – RAF Hercules Fly More Than 150 Oil Workers to Malta – But Up to 500 Still Stranded in Compounds". The Guardian. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ [clarification needed] Gebauer, Matthias (28 February 2011). "Riskante Rettungsmission hinter feindlichen Linien". Der Spiegel (in German). Retrieved 16 March 2011.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|trans_title=(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ [clarification needed] Baldauf, Angi (27 February 2011). "So verlief die spektakuläre Rettungs-Aktion in Libyen – 133 EU-Bürger durch Luftwaffe gerettet – Fallschirmjäger sicherten die Aktion – UN beschliessen Sanktionen gegen Gaddafi". Bild (in German). Retrieved 16 March 2011.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|trans_title=(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ a b c [unreliable source?] Staff writer (5 March 2011). "Libyan Air Force During the Revolt". Zurf Military Aircraft. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (1 March 2011). "3600 Indians Out of Libya, Evacuation Time Extended to March 12". Press Trust of India (via The Times of India). Retrieved 17 March 2011.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ [unreliable source?] Soman, Ebey (27 February 2011). "Indians To Be Evacuated from Libya". NewsFlavor. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (26 February 2011). "RAF Hercules Planes Rescue 150 from Libya Desert". BBC News. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ Staff writer (27 February 2011). "Libya: British Special Forces Rescue More Civilians from Desert". Daily Mirror. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (27 February 2011). "Update 4: RAF Hercules Shot At in Second Libya Rescue Mission". The Times. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (11 March 2011). "Libya: Dutch Helicopter Crew Freed". BBC News. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ (registration required) "Qaddafi Forces Capture 3 Dutch Airmen". The New York Times. Retrieved 3 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (3 March 2011). "Three Dutch Marines Captured During Rescue in Libya". BBC News. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (3 March 2011). "3 Dutch Soldiers Captured in Libya". South African Press Association (via News24). Retrieved 17 March 2011.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Staff writer (4 March 2011). "Libya: Dutch Troops Remain Detained". South African Press Association (via News24). Retrieved 17 March 2011.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Staff writer (2 March 2011). "S. Korean Warship Changes Libyan Destination to Tripoli". Yonhap. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (28 February 2011). "Greek Ferry Brings More Libya Workers to Malta". The Times. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (28 February 2011). "Another Ferry, Frigate Arrive with More Workers". The Times. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (2 March 2011). "HMS York Delivers Humanitarian Aid to Benghazi". The Times. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ Powell, Michael (4 March 2011). "HMS Westminster To Take Over Libyan Duties from HMS York". The News. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (2 March 2011). "Government Announces $5M in Humanitarian Aid to Libya". CTV News Channel. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ Ramdani, Nabila; Shipman, Tim; Leonard, Tom (25 February 2011). "Please Help Us, My Good Friend Tony Blair: Gaddafi's Son Asks for Former PM's Help To 'Crush Enemies'". Daily Mail. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Davis, Gaye (2 March 2011). "Libya Heading for Civil War – Dangor". Independent Online. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ [unreliable source?] Staff writer (3 March 2008). "Gaddafi Accepts Peace Plan To End Crisis; Markets Recover". moneycontrol.com. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (3 March 2011). "Gadaffi Accepts Chavez's Mediation Offer". Indo-Asian News Service (via The Hindustan Times). Retrieved 17 March 2011.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Staff writer (3 March 2011). "Chavez Libya Talks Offer Rejected – United States, France and Opposition Activists Dismiss Venezuelan Proposal To Form a Commission To Mediate Crisis". Al Jazeera English. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (7 March 2011). "British SAS Team 'Released from Libya'". Agence France-Presse (via World News Australia/Special Broadcasting Service). Retrieved 17 March 2011.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Brown, Rachael (8 March 2011). "Hague Red-Faced over SAS Bungle". ABC News. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ Macdonald, Alistair (1 March 2011). "Cameron Doesn't Rule Out Military Force for Libya" (Abstract; (subscription required) for full article). The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- ^ Pullella, Philip (7 March 2011). "Italy Tiptoes on Libya Due to Energy, Trade, Migrants". Reuters (via MSNBC). Retrieved 16 March 2011.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ (registration required) Singer, David E.; Shanker, Thom (2 March 2011). "Gates Warns of Risks of a No-Flight Zone". The New York Times. Retrieved 7 March 2011.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ [dead link] "Russian FM Knocks Down No-Fly Zone for Libya". Yahoo! News. Retrieved 3 March 2011.

- ^ Usborne, David (2 March 2011). "Russia Slams 'No-Fly Zone' Plan as Cracks Appear in Libya Strategy". The Independent. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (1 March 2011). "China Voices Misgivings About Libya 'No-Fly' Zone Plan". Reuters (via AlertNet). Retrieved 16 March 2011.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Johnson, Craig (3 March 2011). "Libyan No-Fly Zone Would Be Risky, Provocative". CNN. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- ^ Rogin, Josh (7 March 2011). "US Ambassador to NATO: No-Fly Zone Wouldn't Help Much". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 15 March 2011.

- ^ Donnet, Pierre-Antoine (7 March 2011). "Britain, France Ready Libya No-Fly Zone Resolution". Agence France-Presse (via Google News). Retrieved 15 March 2011.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ McGreal, Chris (14 March 2011). "Libyan Rebels Urge West To Assassinate Gaddafi as His Forces Near Benghazi – Appeal To Be Made as G8 Foreign Ministers Consider Whether To Back French and British Calls for a No-Fly Zone over Libya". The Guardian. Retrieved 15 March 2011.

- ^ "UN security council resolution on Libya – full text". Guardian.co.uk.

- ^ "BBC News - Libya: UK forces prepare after UN no-fly zone vote". BBC News. BBC. 18 March 2011. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

Further reading

- Pargeter, Alison (2006). "Libya: Reforming the impossible?". Review of African Political Economy. 33 (108): 219–35. doi:10.1080/03056240600842685.

- Sadikia, Larbi (2010). "Wither Arab 'Republicanism'? The Rise of Family Rule and the 'End of Democratization' in Egypt, Libya and Yemen". Mediterranean Politics. 15 (1): 99–107. doi:10.1080/13629391003644827.

External links

- Collected news coverage

- "Libya Uprising". Al Jazeera English.

- "Live Blog". Al Jazeera English.

- "Libya Revolt". BBC News.

- "Libya in Crisis". The Guardian.

- "Libya –The Protests (2011)". The New York Times.

- "Libya". Reuters.

- "Libya 2011". RIA Novosti.

- "Libya". Der Spiegel.

- Articles

- "A Call To Defend Libya's Unity, Sovereignty, and Independence from Imperialist Aggression". Free Arab Voice.

- "Libya 2007–2010 Data, 23 Indicators Related to Peace, Democracy and Other Aspects". Vision of Humanity.

- Clark, Campbell; Chase, Steven (1 March 2011). "Canada Girds for Substantial Military Role in North Africa". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 3 March 2011.