Tour de France: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 40: | Line 40: | ||

|- |

|- |

||

|'''Latest winner''' |

|'''Latest winner''' |

||

|valign="top"|{{flagicon| |

|valign="top"|{{flagicon|USA}} [[Floyd Landis]] <br>([[2006 Tour de France|2006 edition]]) |

||

|- |

|- |

||

|'''Most career Yellow Jerseys''' |

|'''Most career Yellow Jerseys''' |

||

Revision as of 23:58, 1 August 2006

Le Tour de France (Tour of France), often referred to as La Grande Boucle, Le Tour or The Tour, is the most famous and prestigious road bicycle race in the world. With the exception of interruptions for World War I and World War II, it has been held annually since 1903. It is a long-distance stage race competition for professional cycling teams, travelling through France and its nearby countries over the course of three weeks each July. The winner is the individual rider who finishes the course of the race in the least accumulated time.

Other major stage races include the Giro d'Italia (Tour of Italy) and the Vuelta a España (Tour of Spain). The Giro d'Italia, Tour de France, and World Cycling Championship constitute the Triple Crown of Cycling. While the other two European Grand Tours are well-known in Europe and attract many professional cyclists, they are relatively unknown outside the continent, and even the UCI World Cycling Championship is only familiar to cycling enthusiasts. The Tour de France, in contrast, has long been a household name around the globe, even among people who are not generally interested in professional cycling; it is for cycling what the FIFA World Cup is to football (soccer) in global popularity.

Since 2005, the race has been a part of the UCI ProTour race series. The most recent Tour was the 2006 Tour de France.

| File:Logo Tour de France 2005 .JPG Tour de France logo, arranged on the asphalt at Mulhouse. | |

|---|---|

| Tour de France | |

| Local name | Le Tour de France |

| Region | France and nearby countries |

| Date | July 1st to 23rd |

| Type | Stage Race (Grand Tour) |

| General Director | Christian Prudhomme |

| History | |

| First edition | 1903 |

| Number of editions | 93 (2006) |

| First winner | |

| Most wins | |

| Most Consecutive wins | |

| Latest winner | (2006 edition) |

| Most career Yellow Jerseys | |

| Most career stage wins | |

History

Template:Timeline Tour de France WinnersNote: Timeline out of date indefinitely

due to software issues.

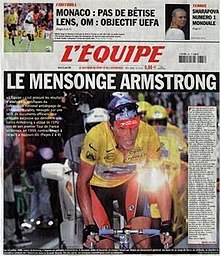

The Tour was founded as a publicity event for the newspaper L'Auto (predecessor to the present l'Équipe) by its editor and co-founder, Henri Desgrange, to rival the Paris-Brest et retour ride (sponsored by Le Petit Journal), and Bordeaux-Paris. The idea for a round-France stage race is also credited to one of his journalists, Géorges Lefèvre, with whom Desgrange had lunch at the Café de Madrid in Paris on 20 November 1902. L'Auto announced the race on January 19, 1903. Promotion of the Tour de France certainly proved a great success for the newspaper; circulation leapt from 25,000 before the 1903 Tour to 65,000 after it; in 1908 the race boosted circulation past a quarter of a million, and during the 1923 Tour it was selling 500,000 copies a day. The record circulation claimed by Desgrange was 854,000, achieved during the 1933 Tour. Today, the Tour is organised by the Société du Tour de France, a subsidiary of Amaury Sport Organisation (ASO), which is part of the media group that owns l'Équipe.

The Tour is a "stage race", divided into a number of stages, each being a race held over one day. The time it takes each rider to complete each stage is noted, recorded, and accumulated. Riders who finish in the same group are awarded the same time, with possible subtractions due to time bonuses. Two riders are said to have finished in the same group if the gap between them is less than one bike-length. A crash within the final 3 kilometres of a normal stage means that all riders in the same group entering the final 3 kilometres are given the same time. The ranking of the riders according to accumulated time is known as the General Classification, or GC. The overall winner is the one who is ranked first on GC at the end of the final stage. It is possible to win the overall race without winning any individual stages (which Greg LeMond did in 1990). Winning a Tour de France stage is considered a great pro cycling achievement, more prestigious than winning most single day races, regardless of one's overall standing in the GC. Although the number of stages has varied in the past, recently the Tour has consisted of about 20 stages, with a total length of between 3,000 and 4,000 km (1800 to 2500 mi). In addition to the race for the overall win, there are several additional competitions. The leaders of these competitions are represented by certain coloured jerseys; see below for more information.

The Tour is nowadays contested by professional teams backed by commercial sponsors, but the event began as a race for individuals; slipstreaming and other team tactics were initially savagely condemned by Desgrange, and he only accepted their inevitability during the 1920s. Even when commercial cycling teams had become commonplace in other events, the Tour was contested by national teams for several years during the 1950s and early 1960s.

Most stages take place in France though it is very common to have a few stages in nearby countries, such as Italy, Spain, Switzerland, Belgium, Luxembourg, and Germany as well as non-neighbouring countries such as the Republic of Ireland, United Kingdom (visited in 1974 and 1994, and will start the 2007 tour) and the Netherlands. The three weeks usually includes two rest days, which are sometimes used to transport the riders long distances between stages.

In recent years, the first stage had been preceded by a short individual time trial (1 to 15 km), called the prologue. This was scrapped in 2005, but was reinstated again in 2006. Since 1975, the traditional finish is in Paris on the Champs-Élysées. During the Tour, various stages occur, including a number of mountain stages, individual time trials and a team time trial (scrapped in 2006). The remaining stages are held over relatively flat terrain. With the variety of stages, sprinters may win stages, but the overall winner is almost always a master of the mountain stages and time trials.

The itinerary of the race changes each year and alternates between clockwise and anti-clockwise direction around France. (For example, 2005 was a clockwise direction Tour — visiting the Alpes first and then the Pyrenees — while the 2006 race visits those two mountain ranges in the reverse order.) Some of the visited places, especially mountains and passes, recur almost annually and are famous on their own. The most famous mountains are those in the hors-categorie (peaks where the difficulty in climbing is beyond categorization), including the Col du Tourmalet, Mont Ventoux, Col du Galibier, the Hautacam, and Alpe d'Huez. Although the tour is often won in the mountain stages, the length and variety of terrain ensures that only an all-round rider can win the race. (A notable exception in recent years being the late Marco Pantani, the winner in 1998, who was a mountain climbing specialist.)

From 1984 to 2003 there was a race called La Grande Boucle Féminine Internationale, which was unofficially considered Tour de France for women.

Tour directors

- 1903 to 1939 Henri Desgrange

- 1947 to 1961 Jacques Goddet

- 1962 to 1986 Jacques Goddet and Felix Levitan

- 1987 to 1988 Jean-François Naquet-Radiguet

- 1988 to 1989 Jean-Pierre Courcol

- 1989 to 2005 Jean-Marie Leblanc

- 2005 to present Christian Prudhomme

Famous stages

Since 1975, the final stage always finishes on the Champs-Élysées in Paris, which is cobbled, making it a difficult surface to cycle on, though not as hard as the famous Paris-Roubaix. The race takes multiple turns over the avenue, which is lined with enormous spectator crowds. This stage is not usually competitive in terms of the overall lead since it is a flat sprinters' stage, and the leader is likely to have a sufficiently large margin to be unchallengeable. There have been exceptions, however. In 1987, with Stephen Roche leading Pedro Delgado by only 40 seconds after the final time trial, Delgado broke away from the peloton on the Champs-Elysées, threatening to snatch victory at the last minute. (In fact he was caught, he and Roche both finished in the peloton, and Roche thereby won the Tour.)

In recent years the Tour organisers have experimented with holding the final time trial as the final, rather than as the penultimate, stage. Most famously, the final stage of the 1989 Tour saw Greg LeMond overtake Laurent Fignon's 50 second overall lead to win by just 8 seconds, the closest winning margin in the Tour's history. It is unlikely that this would be repeated in the future.

The particularly tough climb of Alpe d'Huez is a favourite, providing a stage finish in most Tours. In 2004, in another experiment, the mountain time trial ended at Alpe d'Huez. This seems less likely to be repeated, following complaints of abusive spectator behavior from the riders. Another famous mountain stage is the climb of the Mont Ventoux, often claimed to be the hardest climb in the Tour due to the harsh conditions there. The Tour usually features only one of these two climbs in a year.

To host a stage start or finish brings prestige, and a lot of business, to a town. Whereas formerly each stage would start at the preceding stage's finish line, making a continuous course for the race, nowadays each stage can often start some distance from the previous day's finish, to allow more towns to share in the glory. Sometimes the Tour will jump very long distances between stages, requiring a rest day to allow riders to be transported.

The prologue and first stage of the Tour are particularly prestigious to host. Usually one town will host the prologue (which is too short to go between towns) and also the start of stage 1. In some years, like 2005, there is no prologue. The Tour alternates between starting inside and outside France; traditionally, the first few stages are in a neighbouring country.

Physical rigor

You must add a |reason= parameter to this Cleanup template – replace it with {{Cleanup|July 2006|reason=<Fill reason here>}}, or remove the Cleanup template.

Regarding the level of athleticism and endurance required to complete the Tour de France, the following excerpt from a New York Times article states: "The Tour de France’s status as the world’s most physiologically demanding event is largely unquestioned. The riders cover 2,272 miles (3656 km) at an average speed of 25 miles per hour (40 km/h), roughly the equivalent of running a marathon almost every day for almost three weeks. In the Pyrenees and the Alps, they climb a vertical distance equal to three Mount Everests. They take in up to 10,000 calories per day, the equivalent of 17 Big Macs, elevating their metabolic rates to a level that, according to a Dutch study, is exceeded by only four species on earth."[1]

Classification jerseys

Apart from the overall competition of winning the Tour, each edition of the race has two further classifications: the points and the mountain competitions. Tallied at the end of each stage, the current leaders of the three competitions are required to wear a corresponding, distinctly coloured, jersey during the next stage. Jerseys are awarded in a ceremony immediately following each stage, sometimes before trailing riders have finished the stage. Where a single rider leads in the competition for more than one jersey, they wear the most prestigious jersey to which they are entitled, and the second-placed rider in each of the other classifications becomes entitled to wear the corresponding jersey. For example, in the first week it is common for the overall classification (yellow jersey) and points (sprint) competition (green jersey) to be led by the same rider. In this case the leading rider will wear the yellow jersey and the rider placed second in the points competition will wear the green jersey.

A rider who leads a classification for a stage of the Tour gets three copies of the coloured jersey. The jersey bears their team logo, and the copy that they are awarded immediately after the stage end must have the logo attached in a matter of minutes, so this is done by a rapid process that can be done in the field but which yields an inferior jersey. Overnight, a high-quality jersey is printed to be worn the next day. They also get a high-quality jersey to keep as a souvenir: the ones that are worn get dirty and are sometimes damaged by the day's cycling.

The Tour's jersey colours have been adopted by other cycling stage races, and have thus come to have meaning within cycling generally, rather than solely in the Tour. For example, the Tour of Britain has yellow, green, and polka-dot jerseys with the same meaning as in the Tour de France. The Giro d’Italia notably differs in awarding the overall leader a pink jersey, having been organized and sponsored by La Gazzetta dello Sport, an Italian sports daily newspaper with pink pages.

Overall leader

The maillot jaune (yellow jersey), which is worn by the overall time leader, is the most prized. It is awarded by calculating the total combined race time up to that point for each rider. The rider with the lowest total time is the leader, and at the end of the event is declared the overall winner of the Tour. Desgrange added the yellow jersey in 1919 because he wanted the race leader to wear something distinctive and because the pages of his magazine, L'Auto, were yellow. Additional time bonuses, in the form of a number of seconds to be deducted from the rider's overall time, are available to the first 3 riders to finish the stage or cross an intermediate sprint (see below). As of 2005, the first 3 places to finish are awarded bonuses of 20, 12, and 8 seconds respectively, while the first 3 places at intermediate sprints are awarded 6, 4, and 2 seconds. However, these bonuses are rarely significant enough to cause major upset in the classement géneral (General Classification).

Sometimes a rider takes the overall lead during a stage and gets sufficiently far ahead of the yellow jersey wearer such that his current time lead is greater than his time deficit to the yellow jersey in the general classification; when this happens, this rider may be referred to as being "the yellow jersey on the road". No jerseys can be exchanged in this situation, which is why in other languages it is often called, riding in the "virtual yellow".

Points competition

The maillot vert (green jersey) is awarded for sprint points. At the end of each stage, points for this jersey are earned by the riders who finish first, second, etc. The number of points for each place and the number of riders rewarded varies depending on the type of stage - flat stages give the winner 35 points down to 1 point for the 25th rider; medium mountain stages give the winner 25 points down to 1 point for the 20th rider; high mountain stages give the winner 20 points down to 1 point for the 15th rider. This is because, generally speaking, the more mountainous a stage is, the less likely a sprint finish between many riders is. Points are also awarded for individual time trial stages: 15 for the winner down to 1 for the 10th rider. Additional points are available at intermediate sprint contests, usually occurring 2 or 3 times in each stage at pre-determined locations; currently 6, 4 and 2 points are available to the first 3 riders at each sprint.

King of the Mountains

The "King of the Mountains" wears a white jersey with red dots (maillot à pois rouges), referred to as the "polka dot jersey". At the top of each climb in the Tour, there are points for the riders who are first over the top. The climbs are divided into categories from 1 (most difficult) to 4 (least difficult) based on their difficulty, measured as a function of their steepness and length. A fifth category, called Hors categorie (outside category), is formed by mountains even more difficult than those of the first category.

Although the best climber was first recognised in 1933, the distinctive jersey was not introduced until 1975. The colours were decided by the then sponsor, Poulain Chocolate, to match a popular product. In 2004, the scoring system was changed such that the first rider over a fourth category climb was awarded 3 points while the first to complete a hors category climb would win 20 points. Further points over a fourth category climb are only for the top three places while on a hors category climb the top ten riders are rewarded. Additionally, beginning in 2004, points scored on the final climb of the day were doubled if said climb was at least a second category climb.

Other classifications

There are three lesser classifications, though only one of them awards the leader with a jersey. The maillot blanc (white jersey) is like the yellow jersey, but only open for young riders who are under 25 years old on January 1 of the year the Tour is ridden.

The "fighting spirit" award goes to the most combative rider of the previous stage. Each day, a group of judges awards points to riders who made particularly attacking moves the day before, and the rider with most points in total gets a white-on-red (instead of a black-on-white) identification number. While this is usually given to the winner of the previous stage, it is not always so, especially during flat stages where aggressive riders might be caught by the peloton before a mass sprint. At the end of the tour, an award is given to the rider who was thought to be the most aggressive bike racer throughout the entire three week tour.

There is also a team classification calculated by adding together the times of the top three riders of a team after each stage. The team classification is not associated with a particular jersey design, but beginning in 2006, all members of the leading team receive a black-on-yellow (as opposed to a black-on-white) identification number. Currently, the 20 teams licensed by the UCI ProTour participate in the Tour de France, along with any additional wildcard teams invited by the Tour organizers. Each team consists of 9 riders each (when starting), each sponsored by one or more companies - although at some stages of its history, the teams have been divided instead by nationality.

As in all road races, current national road race champions can wear their national jerseys in "ordinary stages"; the current world champion can wear the rainbow jersey. National time-trial champions are allowed to wear their national jerseys in time-trial stages only. National championships are held the weekend before the tour starts, and many of the tour favourites and team leaders do not compete in them. Often, therefore, national championship titles are held by domestiques or young, "up-and-coming" riders.

Historical jerseys

Historically, there was a red jersey for the standings in non-stage-finish sprints: points were awarded to the first three riders to pass two or three intermediate points during the stage. These sprints also scored points towards the green jersey and bonus seconds towards the overall classification, as well as cash prizes offered by the residents of the area where the sprint took place. The sprints remain, with all these additional effects, the most significant now being the points for the green jersey. The red jersey was abolished in 1989.

There also used to be a combination jersey, scored on a points system based on standings for the yellow, green, red, and polka-dot jerseys. The jersey design was a patchwork, with areas resembling each individual jersey design. This was abolished in the same year as the red jersey.

Stages

Mass-start stages

In an ordinary stage, all riders start simultaneously and share the road. The real start (départ réel) usually is some 2 to 5 km away from the starting point, and is announced by the Tour director in the officials' car waving a white flag.

Riders are permitted to touch (but not push or nudge) and to shelter behind each other, in slipstream. The latter is called drafting and is an essential technique. The one who crosses the finish line first wins. In the first week of the Tour, this usually leads to spectacular mass sprints.

While only finishers are awarded sprint points, all riders finishing in an identifiable group (with no significant gap to the rider in front, as determined by race officials) are deemed to have finished the stage in the same time as the lead rider of that group for overall classification purposes. This avoids what would otherwise be dangerous mass sprints. It is not unusual for the entire field to finish in a single group, taking some time to cross the line, but being credited with the same time as the stage winner.

Time bonuses are awarded at some intermediate sprints and stage finishes to the first three riders who reach the specified point. These bonuses generally are a maximum of 20 seconds, and can allow a good sprinter to qualify for the yellow jersey early in the Tour.

Riders who crash within the last 3 kilometres of the stage are credited with the finishing time of the group that they were with when they crashed. This prevents riders from being penalised for accidents that do not accurately reflect their performance on the stage as a whole given that crashes in the final kilometre can be huge pileups that are hard to avoid for a rider farther back in the peloton. A crashed sprinter inside the final kilometre will not win the sprint, but avoids being penalised in the overall classification. The final kilometre is indicated in the race course by a red triangular pennant - known as the flamme rouge - raised above the road.

Some ordinary stages take place in the mountains, almost always causing major shifts in the General Classification. On ordinary stages that do not have extended mountain climbs, most riders can manage to stay together in the peloton all the way to the finish; during mountain stages, however, it is not uncommon for some riders to lose 40 minutes to the winner of the stage. The so called mountain stages are often the deciding factor in determining the winner of the Tour de France. With the exception of the now traditional finish at the Champs-Elysées all famous stages, like Alpe d'Huez and Mont Ventoux, are mountain stages, and these often bring out the most spectators who line up the roads by the thousands to cheer and encourage the cyclists and support their favorites.

Individual time trials

In an individual time trial each rider rides individually. The first stage of the tour is often a very short time trial, known as a prologue. Here, riders start in reverse order of race number, meaning the weakest rider on the lowest ranked team will be first off, with the final rider being the defending champion, wearing Number 1. If the champion of the last year does not take part, number 1 will be given to the first rider of the team of the former champion.The purpose of the prologue is to decide who gets to wear yellow on the opening day, and provide a large and prestigious spectacle for one lucky city.

There are usually three or four time trials during the Tour. One of these may be a team time trial (see below). Traditionally the final time trial has been the penultimate stage, and effectively determines the winner before the final ordinary stage which is not ridden competitively. On a few occasions, the race organisers made the final stage into Paris a time trial. The most recent occasion on which this was done, in 1989, yielded the closest ever finish in Tour history, when Greg LeMond beat Laurent Fignon by eight seconds overall. Fignon wore the yellow jersey for the final stage, with a narrow lead of 50 seconds, and was beaten by LeMond's superior time trial performance. Although other riders had used aerodynamic aids in previous tours, LeMond's aero handlebars and helmet were considered a major factor in his victory.

Team time trial

Often in the first week of the Tour there is a team time trial (TTT), in which each team rides together without interference from competing teams. The team time is determined by the fifth rider to cross the line; all riders ahead of the fifth rider, and those finishing within one bike length of each other, are awarded this same time. Riders who finish more than one bike-length behind their respective teams are awarded their own individual times.

| 2nd: 20" | 12th: 2' 00" |

| 3rd: 30" | 13th: 2' 10" |

| 4th: 40" | 14th: 2' 20" |

| 5th: 50" | 15th: 2' 30" |

| 6th: 1' | 16th: 2' 35" |

| 7th: 1' 10" | 17th: 2' 40" |

| 8th: 1' 20" | 18th: 2' 45" |

| 9th: 1' 30" | 19th: 2' 50" |

| 10th: 1' 40" | 20th: 2' 55" |

| 11th: 1' 50" | 21st: 3' 00" |

The TTT has been criticized for strongly favoring the strong teams and handicapping strong riders from weaker teams. To address this criticism, the 2004 and 2005 editions of the Tour limited the maximum team time difference relative to the fastest team, according to the team rankings on the stage. The following table indicates the maximum time penalty added to the winning team's time that a team will receive, according to its team time placing. However, this does not apply to riders finishing behind their own teams, and does not protect riders in case of crashing in the last kilometre, unlike during normal stages.

For example, a team that finishes in 14th place, six minutes behind the winning team, would lose only two minutes and 20 seconds in the General Classification relative to the winners of the TTT. If the team time had been 2:13 behind the winning team, then the team time will be 2:13 assuming that this were still the 14th place.

In 2006 there was no TTT in the Tour.

Culture

The Tour is immensely popular and important in France, not only as a sporting event but also as a matter of national identity and pride. Any Frenchman who has won the Tour becomes an object of public adoration in his native land. It is said that any French rider who has worn the yellow jersey, even for a day, will never go hungry or thirsty again in France. Millions of spectators line the route every year to see the Tour first-hand, some of them having encamped a week in advance to get the best views. A recognizable part of the crowd each day is Didi Senft who, dressed in a red devil costume, has been known as the Tour de France devil or El Diablo since 1993. The inspiration for the costume is attributed to the final kilometre of each Tour stage, called the Red Devil's Lap.

In the hours before the riders pass, a carnival atmosphere prevails. Any amateur cyclist is free to attempt the course on his bicycle in the morning, and after which begins a garish cavalcade of advertising vehicles blaring music and tossing hats, souvenirs, sweets and free samples of all sorts. As word passes that the riders are approaching, the fans begin to encroach on the road until they are often just an arm’s length from the riders.

Customs

The riders, unlike some of their fans, have traditionally tempered their competitiveness and enthusiasm with an elaborate but unwritten code of conduct. Whenever reasonably possible, one allows a rider to lead the peloton when the race passes through his home village or on his birthday, and it often happens that the winner of the stage held on Bastille Day is French. One does not attack a leading rider who has suffered a mechanical breakdown or other misfortune, one who is eating in the feed zone or one who is enjoying un besoin naturel (roughly translated to "a natural need", referring to urinating, for which sometimes the entire peloton will stop simultaneously on slow stages where the riders are hyperhydrated). Some riders do not always adhere to these customs, this often leads to animosity in the peloton. Unless the final stage is a time trial, riders generally do not launch attacks on the leader of the Tour on the final stage, giving the leader one final day to bask in the glory of winning the yellow jersey.

The rider ranked last in the general classification, who may wind up in Paris with an overall time five or more hours slower than that of the winner, is called the lanterne rouge. The rider may just be a lowly domestique, but such is the sympathy of the French public that finishing last is actually very prestigious. The money a rider can generate through publicity is much greater if he finishes last than second from last. Thus, in the past many riders have attempted to engineer themselves into last place by artificial means. Other riders may just be ill or slightly injured and unwillingly end up as the lanterne rouge.

Terminology

Much of the terminology used to describe the Tour de France is frequently used in bicycle racing across the world. Terms specific to the Tour de France include:

- flamme rouge, or red kite - the red pennant hanging from an archway at the start of the final kilometre (it may not always be exactly one kilometre from the finish; it is roughly 1000 metres from the finish, sometimes before where a crash may be likely, and/or where the erection of a large, tent-like inflatable arch is easiest)

- lanterne rouge - meaning "red lantern" (as found at the end of a rail train), the name for the overall last-place rider.

- voiture balai - the "broom wagon" is the Tour's van that follows the end of the stage scooping up riders who have abandoned the race due to exhaustion or injury. Some retiring riders, however, prefer to avoid embarrassment and choose to be picked up by the team's support car instead. Riders are generally expected to finish the race within 10–12 percent of the winner’s time or risk being dropped from the tour.

Films

A casual fan, Scott Coady attended the 2000 Tour de France with the aim to make a film. By chance, he got a press accreditation and went on to make The Tour Baby!. His aim has been to raise $100,000 for the benefit of the Lance Armstrong Foundation.[2]

In 2005, two films were released, each chronicling the efforts of a single team competing in the Tour de France. The German film Höllentour, translated as "Hell on Wheels" in English, records the 90th Tour de France in 2003, the centenary year, from the perspective of Team Telekom. The film is directed by Pepe Danquart who won an Academy Award for Live Action Short Film in 1993 for Black Rider (Schwarzfahrer).[3] Also released was Danish film Overcoming by Tómas Gislason, which records the 2004 Tour de France from the perspective of Team CSC.

Perhaps the most famous film about the Tour is Vive Le Tour by Louis Malle. This 18 minute short takes a humourous look at the 1962 edition of La Grande Boucle.

- Höllentour at IMDb

- Overcoming at IMDb

- Vive Le Tour at IMDb

In fiction, the plot of the 2003 cartoon "Les Triplettes de Belleville" (The Triplettes of Belleville) ties into the Tour De France.

Music

The Tour de France also inspired Freddie Mercury, the lead singer of Queen, to write the song "Bicycle Race" in 1978.

In 1983, the German music group Kraftwerk released the single Tour de France which was described as a minimalistic "melding of man and machine".[4] The single was later included on an entire Kraftwerk record dedicated to the race, the Tour de France Soundtracks album from 2003.

The German band Sweetbox wrote a song titled Tour De France dedicated for the race which was supposed to be on the European edition of the Adagio album in 2004. It didn't make the album cut, but was later released on the Raw Treasures Volume 1 album in 2005, a special album with some of the demos and songs that were unreleased.

Doping

Allegations of doping have plagued the Tour almost since its beginning in 1903. Early Tour riders were said to have consumed alcohol and used ether, among other substances, as a means of dulling the pain of competing in endurance cycling. As time went by, riders began using substances as a means of increasing performance rather than dulling the senses, and organizing bodies such as the Tour and the International Cycling Union (UCI), as well as government bodies, enacted policies to combat the practice.

On July 13, 1967, British cyclist Tom Simpson died climbing Mont Ventoux following usage of amphetamines, probably complicated by the now defunct practice of limiting daily water intake to only four bidons, circa 2 litres. His now-famous last words were said to have been "put me back on my bike", although this is disputed.[5]

At the 1998 Tour de France, dubbed the "Tour of Shame", a major doping scandal erupted when Willy Voet, one of the soigneurs for the Festina cycling team, was arrested for the possession of erythropoietin (EPO), growth hormones, testosterone and amphetamines. French police raided several teams in their hotels and found doping products in the possession of the TVM team. The riders staged a "sit-down strike" on stage 17 and refused to continue. After mediation by Jean-Marie Leblanc, the Director of the Tour, police agreed to limit the most heavy-handed tactics and the riders agreed to continue. Many riders and teams had already abandoned, and only 96 riders rode the competition to its end. In a 2000 criminal trial, it became clear that the management and health officials of the Festina team had organised the doping.

In the years following the Festina scandal, anti-doping measures were put into effect by race organizers and the UCI, including more frequent testing of riders and new tests for blood doping (transfusions and EPO use). A new, independent organization, the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA), was also created. Evidence of doping has however persisted. In 2002, the wife of Raimondas Rumsas, third-place finisher in the 2002 Tour de France, was arrested by French police after EPO and anabolic steroids were found in her car. Rumsas, who had not failed any doping test, was not sanctioned. In 2004, Philippe Gaumont, a rider with the Cofidis team, told investigators and the press that doping with various substances was endemic to the team. Fellow Cofidis rider David Millar also confessed to EPO use. In the same year, Jesus Manzano, a rider with the Kelme team, described in bitter tones and lurid detail how he had allegedly been forced by his team to use banned substances.[6]

Doping controversy has surrounded seven-time Tour champion Lance Armstrong for some time, although there has never been evidence sufficient for him to be sanctioned by any sports authority. In late August 2005, one month after Lance Armstrong's seventh consecutive Tour victory, the French sports newspaper l'Équipe claimed to have uncovered evidence that Armstrong had used EPO in the 1999 Tour de France.[7] Armstrong denied using EPO and the UCI did not sanction him. In response to the L'Equipe allegations, an "independent" investigation was begun by the International Cycling Union in October of 2005. The investigation has reported that Armstrong did not engage in doping and that the World Anti-Doping Agency had acted "completely inconsistent" with testing rules.[1] At the same 1999 Tour, Armstrong's urine showed traces of a glucocorticosteroid hormone, although the amount detected was well below the “positive” threshold. However, by the UCI's own rules at the time, Armstrong should in fact have been sanctioned. The cream was not listed on Armstrong's TUE for the tour that year, where all medicines used by the athlete should have been listed. Armstrong explained that he had used the skin cream Cemalyt containing triamcinolone for treatment of saddle sores.[8].

The 2006 Tour had been plagued by the Operación Puerto doping case before its beginning. Many of the riders considered to be favorites, such as Jan Ullrich and Ivan Basso, were banned from competing by their respective teams one day prior to the prologue due to doping allegations. In total, 17 riders have been implicated in the scandal. Four days after winning the 2006 Tour de France, Floyd Landis was announced as having given a positive test result, in his 'A' sample, for a testosterone imbalance, after his Stage 17 win.

Deaths

- 1910: French racer Adolphe Helière drowned at the French Riviera during a rest day.

- 1935: Spanish racer Francisco Cepeda died after plunging down a ravine on the Col du Galibier.[9]

- 1967: July 13, Stage 13: English rider Tom Simpson died of heart failure on the ascent of Mont Ventoux. Amphetamines and alcohol were found on Simpson's jersey and in his bloodstream. His death prompted tour officials to begin a program of drug testing.[9]

- 1995: July 18, stage 15: Italian racer Fabio Casartelli crashed at approximately 88 km/h descending the Col de Portet d'Aspet. Casartelli received massive trauma to the top of his head from a concrete block and died on the scene[9]. He did not have a helmet, although it is unlikely wearing one could have saved him at that speed.

Apart from the deaths of riders, another two fatal accidents have also occurred.

- 1957, July 14, motorcycle rider Rene Wagter and his passenger journalist for Radio Radio-Luxembourg Alex Virot slipping on road metal (gravel) off a road without railing in the mountains near Ax-les-Thermes.[9]

- 1958, Official Constant Wouters died after an accident with sprinter Andre Darrigade in the 6th stage of the tour.

Statistics

Competition winners

One rider has won the Tour a record seven times:

- Lance Armstrong (USA) in 1999, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, and 2005 (seven consecutive years). [10]

Four other riders have won the Tour five times:

- Jacques Anquetil (France) in 1957, 1961, 1962, 1963 and 1964;

- Eddy Merckx (Belgium) in 1969, 1970, 1971, 1972 and 1974;

- Bernard Hinault (France) in 1978, 1979, 1981, 1982 and 1985;

- Miguel Induráin (Spain) in 1991, 1992, 1993, 1994 and 1995 (the first to do so in five consecutive years).

Three other riders have won the Tour three times:

- Philippe Thys (Belgium) in 1913, 1914, and 1920;

- Louison Bobet (France) in 1953, 1954, and 1955;

- Greg LeMond (USA) in 1986, 1989, and 1990.

Gino Bartali holds the record of longest time span between titles, having earned his first and last Tour victories 10 years apart (in 1938 and 1948).

Riders from France have won most Tours (36), followed by Belgium (18), United States (11), Italy (9), Spain (8), Luxembourg (4), Switzerland and the Netherlands (2 each) and Ireland, Denmark and Germany (1 each).

One rider has won the points competition a record six times:

- Erik Zabel (Germany) 1996, 1997, 1998, 1999, 2000 and 2001 (six consecutive years)

One rider has won the "King of the Mountains" a record seven times:

- Richard Virenque (France) in 1994, 1995, 1996, 1997, 1999, 2003 and 2004.

Two riders have won the "King of the Mountains" six times:

- Federico Bahamontes (Spain) in 1954, 1958, 1959, 1962, 1963, 1964

- Lucien Van Impe (Belgium) in 1971, 1972, 1975, 1977, 1981, 1983

Physical statistics

To finish the Tour de France, a cyclist must be in a very good physical state. That said, even a rider who is chosen to ride but does not finish the race will have had to have been very fit to be selected. Analysis of the 2005 competitors shows that:

- The tallest rider was Johan Van Summeren at 1.98 metres (6 ft 5.5 in).

- The shortest was Samuel Dumoulin at 1.58 metres (5 ft 2 in).

- The heaviest rider was Magnus Backstedt at 95 kg (209 lb or 14 stone 13 lb).

- The lightest was Leonardo Piepoli at 57 kg (126 lb or 9 stone).

- Chris Horner and Laurent Lefevre shared the lowest resting heart rate, 35 beats per minute.

- The average rider in 2005 was 1.79 metres (5 ft 10 in) tall, weighed 71 kg (157 lb, 11 stone 3 lb), and had a resting heart rate of 50 beats per minute.

See also

External links

References

- ^ “What He’s Been Pedaling” The New York Times, July 16, 2006.

- ^ Ian Melvin, The Tour Baby!, Cycling News, October 8, 2004

- ^ Blood, sweat and gears, The Sydney Morning Herald, May 27, 2005

- ^ Chris Jones, Kraftwerk, Tour De France Soundtracks, BBC, August 4, 2003

- ^ Memorial section of Tour de France

- ^ “Ex-Kelme rider promises doping revelations” Velo News, March 20, 2004.

- ^ “L’Equipe alleges Armstrong samples show EPO use in 99 Tour” Velo News, August 23, 2005.

- ^ “Armstrong's journey” CNNSI

- ^ a b c d The KOM Fabio Casartelli Memorial Page

- ^ Lance Armstong has retired after last 7th win

External links

- Tour de France Official Website

- Tour de France Official 2005 Regulations (PDF)

- Tour de France race news from Bicycling Magazine

- Tour weblog & directory

- Tour de France on Roadcycling.com

- Cycling Forums - Tour de France forum

- Le Tour de France on France2

- Le Tour de France 2005 in Mulhouse

- Detailed placemarks of the 2005 stages for use in Google Earth

- Tour de France historical statistics (in French)

- TourdeFrance.net - Tour de France Photos, Route & Statistics

Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA