Cossacks: Difference between revisions

removing a protection template from a non-protected page (info) |

DanielLerish (talk | contribs) m Updating the page to correspond with the current consensus as well as removing citations and references to advertisements. |

||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

{{copy edit|date=October 2019}} |

{{copy edit|date=October 2019}} |

||

'''Cossacks'''{{efn|* {{lang-uk|козаки́}} {{IPA-uk|kozɐˈkɪ|}}<br>* {{lang-ru|казаки́}} or {{lang|ru|козаки́}} {{IPA-ru|kəzɐˈkʲi|}}<br>* {{lang-be|казакi}} {{IPA-be|kazaˈkʲi|}}<br>* {{lang-pl|Kozacy}} {{IPA-pl|kɔˈzatsɨ|}}<br>* {{lang-cs|kozáci}} {{IPA-cs|ˈkozaːtsɪ|}}<br>* {{lang-sk|kozáci}} {{IPA-sk|ˈkɔzaːtsi|}}<br>* {{lang-hu|kozákok|cazacii}} {{IPA-hu|ˈkozaːkok|}}<br>* {{lang-fi|Kasakat|cazacii}} {{IPA-fi|ˈkɑsɑkɑt|}}<br>* {{lang-et|Kasakad|cazacii}} {{IPA-et|ˈkɑsɑ.kɑd|}} }} are a group of predominantly [[East Slavic Languages|East Slavic]]-speaking people who became known as members of democratic, self-governing, semi-military communities, |

'''Cossacks'''{{efn|* {{lang-uk|козаки́}} {{IPA-uk|kozɐˈkɪ|}}<br>* {{lang-ru|казаки́}} or {{lang|ru|козаки́}} {{IPA-ru|kəzɐˈkʲi|}}<br>* {{lang-be|казакi}} {{IPA-be|kazaˈkʲi|}}<br>* {{lang-pl|Kozacy}} {{IPA-pl|kɔˈzatsɨ|}}<br>* {{lang-cs|kozáci}} {{IPA-cs|ˈkozaːtsɪ|}}<br>* {{lang-sk|kozáci}} {{IPA-sk|ˈkɔzaːtsi|}}<br>* {{lang-hu|kozákok|cazacii}} {{IPA-hu|ˈkozaːkok|}}<br>* {{lang-fi|Kasakat|cazacii}} {{IPA-fi|ˈkɑsɑkɑt|}}<br>* {{lang-et|Kasakad|cazacii}} {{IPA-et|ˈkɑsɑ.kɑd|}} }} are a group of predominantly [[East Slavic Languages|East Slavic]]-speaking people who became known as members of democratic, self-governing, semi-military communities, originating in the Pontic steppe, north of the Black Sea.<ref>{{Citation|last=Rourke|first=Shane O'|title=Cossacks|date=2011|url=https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/9781444338232.wbeow143|work=The Encyclopedia of War|publisher=American Cancer Society|language=en|doi=10.1002/9781444338232.wbeow143|isbn=978-1-4443-3823-2|access-date=2020-02-11}}</ref> They inhabited sparsely populated areas and islands in the lower [[Dnieper]],<ref>R.P. Magocsi, ''A History of Russia,'' pp. 179–181</ref> [[Don River (Russia)|Don]], [[Terek River|Terek]] and [[Ural River|Ural]] river basins and played an important role in the historical and cultural development of both Ukraine and Russia.<ref name=ORourke_2000>{{Cite book |url=https://books.google.com/?id=L0Zk3tUQ1M4C&pg=PA62&lpg=PA62&dq=cossacks+old+believers |title=Warriors and peasants: The Don Cossacks in late imperial Russia |isbn=978-0-312-22774-6 |last=O'Rourke |first=Shane |year=2000}}</ref><ref>A noted author, Count [[Leo Tolstoy]], wrote "... that all of the Russian history has been made by Cossacks. No wonder Europeans call all of us that ... Our people as a whole wish to be Cossacks." (L. Tosltoy, A Complete Collection of Works, v. 48, page 123, Moscow, 1952; Полн. собр. соч. в 90 т. М., 1952 г., т.48, стр. 123)"</ref> |

||

[[History of the Cossacks|The origins of the Cossacks]] are disputed. Originally the term referred to semi-independent Tatar groups (''qazaq'' or "free men") who inhabited "[[Wild Fields]]" - the steppes north of the Black Sea, near the Dnieper River. Later (by the end of the 15th century) the term was also applied to peasants who had fled to the highly devastated regions along the Dnieper and Don rivers, where they established their self-governing communities. For a long time (at least up to the 1630s) this Cossack groups remained ethnically and religiously open to virtually anybody, but the Slavic element predominated among Cossacks. In the 16th century there were several major Cossack hosts: near the Dnieper, Don, Volga and Ural rivers, the [[Greben Cossacks]] (in Caucasia) and the Zaporozhian Cossacks (mainly west of the Dnieper).<ref name="britannica"/>{{snf|Witzenrath|2007|p=35—36}} |

[[History of the Cossacks|The origins of the Cossacks]] are disputed. Originally the term referred to semi-independent Tatar groups (''qazaq'' or "free men") who inhabited "[[Wild Fields]]" - the steppes north of the Black Sea, near the Dnieper River. Later (by the end of the 15th century) the term was also applied to peasants who had fled to the highly devastated regions along the Dnieper and Don rivers, where they established their self-governing communities. For a long time (at least up to the 1630s) this Cossack groups remained ethnically and religiously open to virtually anybody, but the Slavic element predominated among Cossacks. In the 16th century there were several major Cossack hosts: near the Dnieper, Don, Volga and Ural rivers, the [[Greben Cossacks]] (in Caucasia) and the Zaporozhian Cossacks (mainly west of the Dnieper).<ref name="britannica"/>{{snf|Witzenrath|2007|p=35—36}} |

||

| Line 55: | Line 55: | ||

{{Main|Zaporozhian Cossacks}} |

{{Main|Zaporozhian Cossacks}} |

||

[[File:Запорожский казак. 1884.jpg|thumb|Zaporozhian cossack by [[Konstantin Makovsky]], 1884]] |

[[File:Запорожский казак. 1884.jpg|thumb|Zaporozhian cossack by [[Konstantin Makovsky]], 1884]] |

||

The Zaporozhian Cossacks lived on the [[Pontic–Caspian steppe]] below the [[Dnieper Rapids]] (Ukrainian: ''za porohamy''), also known as the [[Wild Fields]]. They became a well-known group whose numbers increased greatly between the 15th and 17th centuries. Cossacks |

The Zaporozhian Cossacks lived on the [[Pontic–Caspian steppe]] below the [[Dnieper Rapids]] (Ukrainian: ''za porohamy''), also known as the [[Wild Fields]]. They became a well-known group whose numbers increased greatly between the 15th and 17th centuries. The Zaporozhian Cossacks played an important role in European [[geopolitics]], participating in a series of conflicts and alliances with the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, [[Tsardom of Russia|Russia]], and the [[Ottoman Empire]]. |

||

Prior to the formation of the Zaporizhian Sich, Cossacks had been usually organized by [[Ruthenians|Ruthenian]] [[Boyar|boyars]] or princes of the nobility, especially various Lithuanian [[Starosta|starostas]]. Merchants, peasants and runaways from the [[Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth]], Muscovy and Moldavia also joined the Cossacks. |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

The first recorded Zaporizhian Host prototype was formed the nephew of Kostiantyn Ostrozky, [[Dmytro Vyshnevetsky]], built a fortress on the island of Little [[Khortytsia]] on the banks of the Lower [[Dnieper]] in 1552. <ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.encyclopediaofukraine.com/display.asp?linkpath=pages%5CV%5CY%5CVyshnevetskyDmytro.htm|title=Vyshnevetsky, Dmytro|website=www.encyclopediaofukraine.com|access-date=2020-02-11}}</ref>The Zaporizhian Host adopted a lifestyle that combined the ancient Cossack order and habits with those of the [[Knights Hospitaller]]. |

|||

The Cossack structure was created in response to the struggle against Tatar raids, however, another important facet in the growth of the Ukrainian Cossacks was the socio-economic developments occurring in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. During the 16th century because of the favourable conditions of selling grain in Western Europe, serfdom was imposed, subsequently decreasing the locals land allotments and freedom of movement. As well as this, the government of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth attempted to impose Catholicism and Polonise the local Ukrainian population. Hence, the basic form of resistance and opposition by the locals and burghers was flight and settlement in the sparsely populated steppe.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.encyclopediaofukraine.com/display.asp?linkpath=pages%5CC%5CO%5CCossacks.htm|title=Cossacks|website=www.encyclopediaofukraine.com|access-date=2020-02-11}}</ref> |

|||

However, legal ownership of the vast expanses of land on the Dnipro was obtained from the Polish Kings by the nobility who attempted to impose feudal dependency on the locals and utilise them in war by raising the Cossack registry in times of hostility and radically decreasing and forcing the Cossacks back into serfdom in times of peace.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.britannica.com/place/Ukraine|title=Ukraine {{!}} History, Geography, People, & Language|website=Encyclopedia Britannica|language=en|access-date=2020-02-11}}</ref> This institutionalised method of control bred discontent among the Cossacks who by the end of the 16th century began to rise in revolt; the uprisings of Kryshtof Kosynsky (1591-1593), Severyn Nalyvaiko (1594-1596), Hryhorii Loboda (1596), Marko Zhmailo (1625), Taras Fedorovych (1630), Ivan Sulyma (1635), Pavlo Pavliuk and Dmytro Hunia (1637), and Yakiv Ostrianyn and Karpo Skydan (1638) were all brutually suppressed and ended by the Polish government. |

|||

Foreign and external pressure on the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth led to the government making concessions to the Zaporizhian Cossacks, in 1578 King Stephen Bathory granted them certain rights and freedoms and they gradually began to create their foreign policy independent of the government and often against its interests, for example their role in Moldavian affairs and the signage of a treaty with Emperor Rudolf II in the 1590s. <ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.encyclopediaofukraine.com/display.asp?linkpath=pages%5CC%5CO%5CCossacks.htm|title=Cossacks|website=www.encyclopediaofukraine.com|access-date=2020-02-11}}</ref> |

|||

The Cossacks became particularly strong in the first quarter of the 17th century under the leadership of Hetman Petro Konashevych-Saihadachny who launched successful campaiangs against the Tatars and Turks and helped the Polish Army occupy Moscow in 1618 during the Time of Troubles and also aided the Polish Army at the Battle of Khotyn.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.encyclopediaofukraine.com/display.asp?linkpath=pages%5CC%5CO%5CCossacks.htm|title=Cossacks|website=www.encyclopediaofukraine.com|access-date=2020-02-11}}</ref> |

|||

After Ottoman-Polish warfare ceased the official Cossack register was again decreased, the registered Cossacks (reiestrovi kozaky) were isolated from the ones who were excluded from the register and those from the Zaporizhian Host. This together with intensified socioeconomic and national-religious oppression of the other classes of Ukrainian society resulted in a number of Cossack Uprisings occurring in the 1630s, eventually culminating in the Khmelnytsky uprising led by the Hetman of the Zaporizhian Sich, Bohdan Khmelnytsky. |

|||

| ⚫ | As a result of the [[Khmelnytsky Uprising]] in the middle of the 17th century, the Zaporozhian Cossacks briefly established an independent state, which later became the autonomous [[Cossack Hetmanate]] (1649–1764). It was a [[suzerainty]] under protection of the Russian Tsar from 1667 but ruled by the local [[Hetmans of Ukrainian Cossacks|Hetmans]] for a century. |

||

The Zaporozhian Sich had its own authorities, its own "Nizovy" Zaporozhsky Host, and its own land. In the latter half of the 18th century, Russian authorities destroyed this Zaporozhian Host and gave its lands to landlords. Some Cossacks moved to the [[Danube]] delta region, where they formed the Danubian Sich under Ottoman rule. To prevent further defection of Cossacks, the Russian government restored the special Cossack status of the majority of Zaporozhian Cossacks. This allowed them to unite in the Host of Loyal Zaporozhians and later to reorganize into other hosts, of which the Black Sea host was most important. They eventually moved to the [[Krasnodar krai|Kuban region]], due to the distribution of Zaporozhian Sich lands among landlords and the resulting scarcity of land. |

The Zaporozhian Sich had its own authorities, its own "Nizovy" Zaporozhsky Host, and its own land. In the latter half of the 18th century, Russian authorities destroyed this Zaporozhian Host and gave its lands to landlords. Some Cossacks moved to the [[Danube]] delta region, where they formed the Danubian Sich under Ottoman rule. To prevent further defection of Cossacks, the Russian government restored the special Cossack status of the majority of Zaporozhian Cossacks. This allowed them to unite in the Host of Loyal Zaporozhians and later to reorganize into other hosts, of which the Black Sea host was most important. They eventually moved to the [[Krasnodar krai|Kuban region]], due to the distribution of Zaporozhian Sich lands among landlords and the resulting scarcity of land. |

||

Revision as of 16:37, 11 February 2020

| Part of a series on |

| Cossacks |

|---|

|

| Cossack hosts |

| Other Cossack groups |

| History |

| Notable Cossacks |

| Cossack terms |

| Cossack folklore |

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2019) |

This article may require copy editing for grammar, style, cohesion, tone, or spelling. (October 2019) |

Cossacks[a] are a group of predominantly East Slavic-speaking people who became known as members of democratic, self-governing, semi-military communities, originating in the Pontic steppe, north of the Black Sea.[1] They inhabited sparsely populated areas and islands in the lower Dnieper,[2] Don, Terek and Ural river basins and played an important role in the historical and cultural development of both Ukraine and Russia.[3][4]

The origins of the Cossacks are disputed. Originally the term referred to semi-independent Tatar groups (qazaq or "free men") who inhabited "Wild Fields" - the steppes north of the Black Sea, near the Dnieper River. Later (by the end of the 15th century) the term was also applied to peasants who had fled to the highly devastated regions along the Dnieper and Don rivers, where they established their self-governing communities. For a long time (at least up to the 1630s) this Cossack groups remained ethnically and religiously open to virtually anybody, but the Slavic element predominated among Cossacks. In the 16th century there were several major Cossack hosts: near the Dnieper, Don, Volga and Ural rivers, the Greben Cossacks (in Caucasia) and the Zaporozhian Cossacks (mainly west of the Dnieper).[5][6]

The Zaporizhian Sich were a vassal polity of Poland–Lithuania during feudal times. Under increasing pressure from the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, in the mid-17th century the Sich declared an independent Cossack Hetmanate, initiated by a rebellion under Bohdan Khmelnytsky. Afterwards, the Treaty of Pereyaslav (1654) brought most of the Cossack state under Russian rule.[7] The Sich with its lands became an autonomous region under the Russian-Polish protectorate.[8]

The Don Cossack Host, which had been established by the 16th century,[9] allied with the Tsardom of Russia. Together, they began a systematic conquest and colonisation of lands in order to secure the borders on the Volga, the whole of Siberia (see Yermak Timofeyevich) and the Yaik (Ural) and the Terek rivers. Cossack communities had developed along the latter two rivers well before the arrival of the Don Cossacks.[10]

By the 18th century, Cossack hosts in the Russian Empire occupied effective buffer zones on its borders. The expansionist ambitions of the Empire relied on ensuring the loyalty of Cossacks, which caused tension given their traditional exercise of freedom, democracy, self-rule, and independence. Cossacks such as Stenka Razin, Kondraty Bulavin, Ivan Mazepa and Yemelyan Pugachev led major anti-imperial wars and revolutions in the Empire in order to abolish slavery, harsh bureaucracy and to maintain independence. The empire responded with ruthless executions and tortures, the destruction of the western part of the Don Cossack Host during the Bulavin Rebellion in 1707–1708, the destruction of Baturyn after Mazepa's rebellion in 1708,[b] and the formal dissolution of the Lower Dnieper Zaporozhian Host in 1775, after Pugachev's Rebellion.[c]

By the end of the 18th century, Cossack nations had been transformed into a special military estate (Sosloviye), "a military class."[d] Similar to the knights of medieval Europe in feudal times or the tribal Roman auxiliaries, the Cossacks came to military service having to obtain charger horses, arms and supplies at their own expense. The government provided only firearms and supplies for them.[e] Cossack service was considered rigorous.

Because of their military tradition, Cossack forces played an important role in Russia's wars of the 18th–20th centuries, such as the Great Northern War, the Seven Years' War, the Crimean War, Napoleonic Wars, the Caucasus War, numerous Russo-Persian Wars, numerous Russo-Turkish Wars and the First World War. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the Tsarist regime used Cossacks extensively to perform police service.[f] They also served as border guards on national and internal ethnic borders (as was the case in the Caucasus War).

During the Russian Civil War, Don and Kuban Cossacks were the first people to declare open war against the Bolsheviks. By 1918 Russian Cossacks declared their complete independence and formed independent states, the Don Republic and the Kuban People's Republic. Also the Ukrainian State emerged. Cossack troops formed the effective core of the anti-Bolshevik White Army, and Cossack republics became centers for the anti-Bolshevik White movement. With the victory of the Red Army, the Cossack lands were subjected to Decossackization and the Holodomor. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the Cossacks made a systematic return to Russia. Many took an active part in post-Soviet conflicts. In Russia's 2002 Population Census, 140,028 people reported their ethnicity as Cossacks.[12] There are Cossack organizations in Russia, Kazakhstan, Ukraine, Belarus and the United States.[13][14][15]

Etymology

Max Vasmer's etymological dictionary traces the name to the Old East Slavic word козакъ, kozak, a loanword from Cuman, in which cosac meant "free man", from Turkic languages.[16] The ethnonym Kazakh is from the same Turkic root.[17][5][18] In modern Turkish it is pronounced as "Kazak".

In written sources the name is first attested in Codex Cumanicus from the 13th century.[19][20] In English, "Cossack" is first attested in 1590.[17]

Early history

It is not clear when Slavic people apart from Brodnici and Berladniki started settling in the lower reaches of major rivers such as the Don and the Dnieper after the demise of the Khazar state. It is unlikely it could have happened before the 13th century, when the Mongols broke the power of the Cumans, who had assimilated the previous population on that territory. It is known that new settlers inherited a lifestyle that persisted there long before, such as those of the Turkic Cumans and the Circassian Kassaks.[21] However, Slavic settlements in southern Ukraine started to appear relatively early during the Cuman rule, with the earliest ones, like Oleshky, dating back to the 11th century.

Early "Proto-Cossack" groups are generally reported to have come into existence within the present-day Ukraine in the 13th century as the influence of Cumans grew weaker, though some have ascribed their origins to as early as the mid-8th century.[22] Some historians suggest that the Cossack people were of mixed ethnic origins, descending from Russians, Ukrainians, Belarusians, Turks, Tatars, and others who settled or passed through the vast Steppe.[23] However some Turkologists argue that Cossacks are descendants of native Cumans of Ukraine, who lived there long ago before the Mongol invasion.[24]

In the midst of the growing Moscow and Lithuanian powers, new political entities had appeared in the region, such as Moldavia and the Crimean Khanate. In 1261, some Slavic people living in the area between the Dniester and the Volga were mentioned in Ruthenian chronicles. Historical records of the Cossacks before the 16th century are scant, as is the history of the Ukrainian lands in that period for various reasons.

As early as the 15th century, a few individuals ventured into the "Wild Fields", the southern frontier regions of Ukraine separating Poland-Lithuania from the Crimean Khanate, which was a naturally rich and fertile region teeming with cattle, wild animals and fish. These ventures went on short-term expeditions to acquire the region's natural wealth and this mode of existing—farming, hunting, then returning home in the winter or perhaps remaining permanently—came to be known as the Cossack way of life.[25] The Crimean–Nogai raids into East Slavic lands brought considerable devastation and depopulation to this area. The Tatar raids also played an important role in the development of the Cossacks.[26][27][28]

In the 15th century, Cossack society was described as a loose federation of independent communities, often forming local armies, entirely independent from the neighboring states (of, for example, Poland, the Grand Duchy of Moscow or the Crimean Khanate).[29] According to Hrushevsky the first mention of Cossacks could be found already in the 14th century; however, they were either of Turkic or undefined origin.[30] Hrushevsky states that Cossacks could have descended from the long-forgotten Antes, or groups from the Berlad territory in present-day Romania, then a part of the Grand Duchy of Halych, Brodniki. There, Cossacks may have served as self-defense formations, organized to defend against raids conducted by neighbors. By 1492 the Crimean Khan complained that Kanev and Cherkasy Cossacks attacked his ship near Tighina (Bender), and the Grand Duke of Lithuania Alexander I promised to find the guilty among the Cossacks. Sometime in the 16th century there appeared the old Ukrainian Ballad of Cossack Holota about a Cossack near Kiliya.[31][32]

By the 16th century, these Cossack societies merged into two independent territorial organisations as well as other smaller, still detached groups:

- The Cossacks of Zaporizhia, centered on the lower bends of Dnieper, inside the territory of modern Ukraine, with the fortified capital of Zaporozhian Sich. They were formally recognised as an independent state, the Zaporozhian Host, by a treaty with Poland in 1649.

- The Don Cossack State, on the River Don. The capital of the Don Cossack State was initially Razdory, then it was moved to Cherkassk, and later to Novocherkassk.

In addition to these two, one finds mention of the less well-known Tatar Cossacks such as Nağaybäklär and Meschera (mishari) Cossacks, of whom Sary Azman was the first Don ataman and which not only were assimilated by Don Cossacks but had their own irregular Bashkir and Meschera Host up to the end of the 19th century.[33] Kalmyk and Buryat Cossacks should be mentioned as well.[34]

Zaporozhian Cossacks

The Zaporozhian Cossacks lived on the Pontic–Caspian steppe below the Dnieper Rapids (Ukrainian: za porohamy), also known as the Wild Fields. They became a well-known group whose numbers increased greatly between the 15th and 17th centuries. The Zaporozhian Cossacks played an important role in European geopolitics, participating in a series of conflicts and alliances with the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, Russia, and the Ottoman Empire.

Prior to the formation of the Zaporizhian Sich, Cossacks had been usually organized by Ruthenian boyars or princes of the nobility, especially various Lithuanian starostas. Merchants, peasants and runaways from the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, Muscovy and Moldavia also joined the Cossacks.

The first recorded Zaporizhian Host prototype was formed the nephew of Kostiantyn Ostrozky, Dmytro Vyshnevetsky, built a fortress on the island of Little Khortytsia on the banks of the Lower Dnieper in 1552. [35]The Zaporizhian Host adopted a lifestyle that combined the ancient Cossack order and habits with those of the Knights Hospitaller.

The Cossack structure was created in response to the struggle against Tatar raids, however, another important facet in the growth of the Ukrainian Cossacks was the socio-economic developments occurring in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. During the 16th century because of the favourable conditions of selling grain in Western Europe, serfdom was imposed, subsequently decreasing the locals land allotments and freedom of movement. As well as this, the government of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth attempted to impose Catholicism and Polonise the local Ukrainian population. Hence, the basic form of resistance and opposition by the locals and burghers was flight and settlement in the sparsely populated steppe.[36]

However, legal ownership of the vast expanses of land on the Dnipro was obtained from the Polish Kings by the nobility who attempted to impose feudal dependency on the locals and utilise them in war by raising the Cossack registry in times of hostility and radically decreasing and forcing the Cossacks back into serfdom in times of peace.[37] This institutionalised method of control bred discontent among the Cossacks who by the end of the 16th century began to rise in revolt; the uprisings of Kryshtof Kosynsky (1591-1593), Severyn Nalyvaiko (1594-1596), Hryhorii Loboda (1596), Marko Zhmailo (1625), Taras Fedorovych (1630), Ivan Sulyma (1635), Pavlo Pavliuk and Dmytro Hunia (1637), and Yakiv Ostrianyn and Karpo Skydan (1638) were all brutually suppressed and ended by the Polish government.

Foreign and external pressure on the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth led to the government making concessions to the Zaporizhian Cossacks, in 1578 King Stephen Bathory granted them certain rights and freedoms and they gradually began to create their foreign policy independent of the government and often against its interests, for example their role in Moldavian affairs and the signage of a treaty with Emperor Rudolf II in the 1590s. [38]

The Cossacks became particularly strong in the first quarter of the 17th century under the leadership of Hetman Petro Konashevych-Saihadachny who launched successful campaiangs against the Tatars and Turks and helped the Polish Army occupy Moscow in 1618 during the Time of Troubles and also aided the Polish Army at the Battle of Khotyn.[39]

After Ottoman-Polish warfare ceased the official Cossack register was again decreased, the registered Cossacks (reiestrovi kozaky) were isolated from the ones who were excluded from the register and those from the Zaporizhian Host. This together with intensified socioeconomic and national-religious oppression of the other classes of Ukrainian society resulted in a number of Cossack Uprisings occurring in the 1630s, eventually culminating in the Khmelnytsky uprising led by the Hetman of the Zaporizhian Sich, Bohdan Khmelnytsky.

As a result of the Khmelnytsky Uprising in the middle of the 17th century, the Zaporozhian Cossacks briefly established an independent state, which later became the autonomous Cossack Hetmanate (1649–1764). It was a suzerainty under protection of the Russian Tsar from 1667 but ruled by the local Hetmans for a century.

The Zaporozhian Sich had its own authorities, its own "Nizovy" Zaporozhsky Host, and its own land. In the latter half of the 18th century, Russian authorities destroyed this Zaporozhian Host and gave its lands to landlords. Some Cossacks moved to the Danube delta region, where they formed the Danubian Sich under Ottoman rule. To prevent further defection of Cossacks, the Russian government restored the special Cossack status of the majority of Zaporozhian Cossacks. This allowed them to unite in the Host of Loyal Zaporozhians and later to reorganize into other hosts, of which the Black Sea host was most important. They eventually moved to the Kuban region, due to the distribution of Zaporozhian Sich lands among landlords and the resulting scarcity of land.

The majority of Danubian Sich Cossacks had moved first to the Azov region in 1828, and later joined other former Zaporozhian Cossacks in the Kuban region. Groups were generally identified by faith rather than language in that period,[citation needed] and most descendants of Zaporozhian Cossacks in the Kuban region are bilingual, speaking both Russian and the local Kuban dialect of central Ukrainian. Their folklore is largely Ukrainian.[g] The predominant view of ethnologists and historians is considered to be found in the common culture dating back to the Black Sea Cossacks.[40][41][42]

The Zaporozhians gained a reputation for their raids against the Ottoman Empire and its vassals, although they sometimes plundered other neighbors as well. Their actions increased tension along the southern border of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. Low-level warfare took place in those territories for most of the period of the Commonwealth (1569–1795).

In 1539, the Ottoman Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent asked Grand Duke Vasili III of Russia to restrain the Cossacks; the Duke replied: "The Cossacks do not swear allegiance to me, and they live as they themselves please."[citation needed] In 1549, Tsar Ivan the Terrible replied to Suleiman's request that he stop the attacks by the Don Cossacks, saying, "The Cossacks of the Don are not my subjects, and they go to war or live in peace without my knowledge."[citation needed] The major powers tried to exploit Cossack warmongering for their own purposes. In the 16th century, with the power of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth extending south, the Zaporozhian Cossacks were mostly, if tentatively, regarded by the Commonwealth as their subjects.[43] Registered Cossacks formed a part of the Commonwealth army until 1699.

Around the end of the 16th century, relations between the Commonwealth and the Ottoman Empire were strained by increasing Cossack aggression. From the second part of the 16th century, Cossacks started raiding Ottoman territories. The Polish government could not control the Cossacks, but was held responsible as the men were nominally their subjects. In retaliation, Tatars living under Ottoman rule launched raids into the Commonwealth, mostly in the southeast territories. In retaliation, Cossack pirates started raiding wealthy trading port-cities in the heart of the Ottoman Empire, as these were just two days away by boat from the mouth of the Dnieper river. By 1615 and 1625, Cossacks had razed suburbs of Constantinople, forcing the Ottoman Sultan to flee his palace.[46] In 1637 the Zaporozhian Cossacks, joined by the Don Cossacks, captured the strategic Ottoman fortress of Azov, which guarded the Don.[47]

Consecutive treaties between the Ottoman Empire and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth called for the governments to keep the Cossacks and Tatars in check, but neither enforced the treaties strongly. The Polish forced the Cossacks to burn their boats and stop raiding by sea, but they did not give it up entirely. During this time, the Habsburg Monarchy sometimes covertly hired Cossack raiders to go against the Ottomans to ease pressure on their own borders. Many Cossacks and Tatars developed longstanding enmity due to the losses of their raids. The ensuing chaos and cycles of retaliation often turned the entire southeastern Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth border into a low-intensity war zone. It catalyzed escalation of Commonwealth–Ottoman warfare, from the Moldavian Magnate Wars (1593–1617) to the Battle of Cecora (1620) and campaigns in the Polish–Ottoman War of 1633–1634.

Cossack numbers expanded when the warriors were joined by peasants escaping serfdom in Russia and dependence in the Commonwealth. Attempts by the szlachta to turn the Zaporozhian Cossacks into peasants eroded the Cossacks' formerly strong loyalty towards the Commonwealth. The government constantly rebuffed Cossack ambitions for recognition as equal to the szlachta, and plans for transforming the Polish–Lithuanian two-nation Commonwealth into a Polish–Lithuanian–Rus' Commonwealth made little progress due to the idea's unpopularity among the Rus' szlachta of the Rus' Cossacks being equal to Rus' szlachta. The Cossacks' strong historic allegiance to the Eastern Orthodox Church also put them at odds with officials of the Roman Catholic-dominated Commonwealth. Tensions increased when Commonwealth policies turned from relative tolerance to suppression of the Eastern Orthodox church after the Union of Brest. The Cossacks became strongly anti-Roman Catholic, in this case, an attitude that became synonymous with anti-Polish.

Registered Cossacks

The waning loyalty of the Cossacks and the szlachta's arrogance towards them resulted in several Cossack uprisings against the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth in the early 17th century. Finally, the King's adamant refusal to accede to the Cossacks' demand to expand the Cossack Registry was the last straw that prompted the largest and most successful of these: the Khmelnytsky uprising that started in 1648. Some Cossacks, including Polish schlahta, converted to Eastern Orthodoxy, divided the lands of Ruthenian szlachta in Ukraine, and became the Cossack szlachta. The uprising became one of a series of catastrophic events for the Commonwealth known as The Deluge, which greatly weakened the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and set the stage for its disintegration 100 years later.

The influential relatives of Russian and Lithuanian szlachta in Moscow helped to create the Russian–Polish alliance against Khmelnitsky's Cossacks as rebels against any order and the private property of Ruthenian Orthodox schlahta, Don Cossack raids on Crimea leaving Khmelnitsky without the aid of his usual Tatar allies. But in Russian opinion, the rebellion ended with the 1654 Treaty of Pereyaslav in which Khmelnitsky Cossacks so that to destroy the Russian–Polish alliance against them pledged their loyalty to the Russian Tsar with the latter guaranteeing Cossacks his protection, recognition of Cossack starshyna (nobility) and their property and autonomy under his rule, freeing the Cossacks from the Polish sphere of influence and land claims of Ruthenian schlahta.[48]

Only some part of the Ruthenian schlahta of the Chernigov region, being of the Moscow state origin, saved their lands from division among Cossacks and became the part of the Cossack schlachta. After this, Ruthenian schlahta refrained from its plans to have a Moscow tsar the king of the Commonwealth, its own Michał Korybut Wiśniowiecki became the king later. The last, ultimately unsuccessful, attempt to rebuild the Polish–Cossack alliance and create a Polish–Lithuanian–Ruthenian Commonwealth was the 1658 Treaty of Hadiach, which was approved by the Polish King and Sejm as well as by some of the Cossack starshyna, including Hetman Ivan Vyhovsky.[49] The starshyna were, however, divided on the issue and the treaty had even less support among rank-and-file Cossacks; thus it failed.

Under Russian rule, the Cossack nation of the Zaporozhian Host was divided into two autonomous republics of the Moscow Tsardom: the Cossack Hetmanate, and the more independent Zaporizhia. These organisations gradually lost their autonomy, and were abolished by Catherine II by the late 18th century. The Hetmanate became the governorship of Little Russia, and Zaporizhia was absorbed into New Russia.

In 1775, the Lower Dnieper Zaporozhian Host was destroyed. Later, its high-ranking Cossack leaders were exiled to Siberia,[50] the last chief becoming the prisoner of the Solovetsky Islands, for the establishment of a new Sich in the Ottoman Empire by the part of Cossacks without any involvement of the punished Cossack leaders.[51]

Black Sea, Azov and Danubian Sich Cossacks

With the destruction of the Zaporozhian Sich, many Zaporozhian Cossacks, especially the vast majority of Old Believers and other people from the Greater Russia, defected to Turkey and settled in the area of the Danube river, founding a new Sich there. Part of these Cossacks settled on Tisa river in the Austrian Empire and formed a new Sich there as well. Some Ukrainian-speaking Eastern Orthodox Cossacks ran away across the Danube (territory under the control of the Ottoman Empire), together with Cossacks of the Greater Russia origin, to form a new host before rejoining the others in the Kuban. Many Ukrainian peasants and adventurers joined the Danubian Sich afterwards. Ukrainian folklore remembers the Danubian Sich, while new siches of Loyal Zaporozhians on the Bug and Dniester are not famous ones. The majority of Tisa Sich and Danubian Sich Cossacks returned to Russia in 1828 and settled in the area north of the Azov Sea and became known as the Azov Cossacks. But the majority of Zaporozhian Cossacks, especially Ukrainian-speaking Eastern Orthodox, remained loyal to Russia in spite of the Sich destruction and became known as the Black Sea Cossacks. Both Azov and Black Sea Cossacks were resettled to colonise the Kuban steppe, which was a crucial foothold for Russian expansion in the Caucasus.

During the Cossack stay in Turkey, a new host was founded that numbered around 12,000 Cossacks by the end of 1778. Their settlement at the border with Russia was approved by the Ottoman Empire after the Cossacks officially vowed to serve the Sultan. Yet the conflict inside the new host, and the political manoeuvres used by the Russian Empire, led to splits among the Cossacks. After a portion of the runaway Cossacks returned to Russia they were used by the Russian army to form new military bodies that also incorporated Greeks, Albanians, Crimean Tatars and Gypsies. However, after the Russo-Turkish war of 1787–1792, most of them were incorporated into the Black Sea Cossack Host together with Loyal Zaporozhian. The Black Sea Host moved to the Kuban steppes. Most of the remaining Cossacks that stayed in the Danube delta returned to Russia in 1828 and created the Azov Cossack Host between Berdyansk and Mariupol. In 1860, more Cossacks were resettled to the North Caucasus and merged into the Kuban Cossack Host.

Russian Cossacks

The native land of the Cossacks is defined by a line of Russian/Ruthenian town-fortresses located on the border with the steppe and stretching from the middle Volga to Ryazan and Tula, then breaking abruptly to the south and extending to the Dnieper via Pereyaslavl. This area was settled by a population of free people practicing various trades and crafts.

These people, constantly facing the Tatar warriors on the steppe frontier, received the Turkic name Cossacks (Kazaks), which was then extended to other free people in Russia. Many Cumans, who had assimilated Khazars, retreated to the Ryazan Grand principality (Grand Duchy) after the Mongol invasion. The oldest reference in the annals mentions Cossacks of the Russian principality of Ryazan serving the principality in the battle against the Tatars in 1444. In the 16th century, the Cossacks (primarily those of Ryazan) were grouped in military and trading communities on the open steppe and started to migrate into the area of the Don.[52] Other theories suggest that Cossacks are of Iranian origin.

Cossacks served as border guards and protectors of towns, forts, settlements and trading posts, performed policing functions on the frontiers and also came to represent an integral part of the Russian army. In the 16th century, to protect the borderland area from Tatar invasions, Cossacks carried out sentry and patrol duties, guarding from Crimean Tatars and nomads of the Nogai Horde in the steppe region.

The most popular weapons used by Cossack cavalrymen were usually sabres, or shashka, and long spears.

Russian Cossacks played a key role in the expansion of the Russian Empire into Siberia (particularly by Yermak Timofeyevich), the Caucasus and Central Asia in the period from the 16th to 19th centuries. Cossacks also served as guides to most Russian expeditions formed by civil and military geographers and surveyors, traders and explorers. In 1648, the Russian Cossack Semyon Dezhnyov discovered a passage between North America and Asia. Cossack units played a role in many wars in the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries (such as the Russo-Turkish Wars, the Russo-Persian Wars, and the annexation of Central Asia).

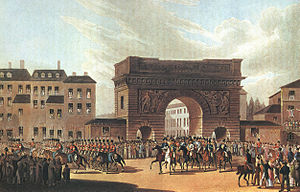

Western Europeans had a lot of contacts with Cossacks during the Seven Years' War and had seen Cossack patrols in Berlin.[53] During Napoleon's Invasion of Russia, Cossacks were the Russian soldiers most feared by the French troops. Napoleon himself stated "Cossacks are the best light troops among all that exist. If I had them in my army, I would go through all the world with them."[54] Cossacks also took part in the partisan war deep inside French-occupied Russian territory, attacking communications and supply lines. These attacks, carried out by Cossacks along with Russian light cavalry and other units, were one of the first developments of guerrilla warfare tactics and, to some extent, special operations as we know them today.

Frenchmen had had few contacts with Cossacks before the Allies occupied Paris in 1814. As the most exotic of the Russian troops seen in France, Cossacks drew a great deal of attention and notoriety for their alleged purity[clarification needed] during Napoleon's wars. Bistrots appeared after the Cossack occupation of Paris.[55] Stendhal had said that "Cossacks were pure as children and great as Gods."

Don Cossacks

The Don Cossack Host (Russian: Всевеликое Войско Донское, Vsevelikoye Voysko Donskoye) was either an independent or an autonomous democratic republic in present-day Southern Russia from the end of the 16th century until the early 20th century. In the year 948, Byzantine Emperor Constantine mentioned of trade of goods, between the Don Cossacks in their home capital. Don Cossacks had a rich military tradition, playing an important part in the historical development of the Russian Empire and successfully participating in all of its major wars.

The exact origins of Don Cossacks are unknown. In modern view, Don Cossacks are descendants of both Slavic people and Khazars, which assimilated Goths, Alans,[h] and possibly of Rugii, Roxolans, Alans and even Goths-Alans of the Black Sea Rus[56] See the works of Evgueni Goloubinski and Vasily Vasilievsky about Relations of Gothoalans (Goths-Tetraxits) and Russian colonists in region of North-East part of Black Sea and Sea of Azov as well. The Goths-Alans came from the Western part of North Caucasus and from Northern Europe, Goths intermixed with Slavs during their trip from Northern Europe. When Alans had moved to Europe, these Goths occupied the part of the former Alania in Crimea and were called Gothoalans, Russian occupying another part were called Roxolans. Later people from the western part of North Caucasus joined Gotho-Alans in their Feodoro principality. It is believed that Crimean Greeks have the Gotho-Alan ancestry, among others. Mikhail Lomonosov was the first to identify Roxolans as Russians similar to Gotho-Alan identification as Goths. New Slavic people have come from Dnepr and Taman, and from Novgorod Republic and Principality of Ryazan, both before and after their violent occupation and subjugation by the Muscovite Tsardom.[i]

The majority of Don Cossacks are either Eastern Orthodox or Christian Old Believers (старообрядцы);[3][57] and prior to the Civil War in Russia, there were numerous religious minorities, including Muslims, Subbotniks, Jews, and others.[j][58]

Kuban Cossacks

Kuban Cossacks are Cossacks who live in the Kuban region of Russia. Although numerous Cossack groups came to inhabit the Western Northern Caucasus most of the Kuban Cossacks are descendants of the Black Sea Cossack Host, (originally the Zaporozhian Cossacks) and the Caucasus Line Cossack Host.

A distinguishing feature from other cossacks is the Chupryna or Oseledets hairstyle, a roach haircut popular among some Kubanians. This is due to their traditional roots, going back to the Zaporizhian Sich.

Terek Cossacks

The Terek Cossack Host was a Cossack host created in 1577 from free Cossacks who resettled from the Volga to the Terek River. Aboriginal Terek Cossacks joined this host later. In 1792 the Host was included in the Caucasus Line Cossack Host and separated from it again in 1860, with the capital of Vladikavkaz. In 1916, the population of the Host was 255,000 within an area of 1.9 million desyatinas.[citation needed]

Yaik Cossacks

The Ural Cossack Host was formed from the Ural Cossacks, who had settled along the Ural River. Their alternative name, Yaik Cossacks, comes from the former name of the river, which was changed by the government after the Pugachev's rebellion. The Ural Cossacks spoke Russian and identified as having primarily Russian ancestry, but they also incorporated many Tatars into their ranks.[59] Twenty years after Moscow had conquered the Volga from Kazan to Astrakhan, in 1577,[60] the government sent troops to disperse pirates and raiders along the Volga (one of their numbers was Ermak). Some escaped to flee southeast to the Ural River, where they joined Yaik Cossacks. In 1580, they captured Saraichik. By 1591 they were fighting on behalf of the government in Moscow. During the next century, they were officially recognized by the imperial government.

Razin and Pugachev Rebellions

The Cossacks, as a largely independent nation, had to defend their liberties and democratic traditions against the ever-expanding Muscovy, succeeded by Russian Empire. The Cossacks tended acted independently of the Tsardom of Muscovy, increasing friction between the two. The Tsardom's power began to grow in 1613 with the ascension of Mikhail Romanov to the throne after the Time of Troubles. The government began attempting to integrate the Cossacks into the Muscovite Tsardom by granting elite status and enforcing military service, thus creating divisions within the Cossacks themselves as they fought to keep their own traditions alive. The government's efforts to alter the traditional nomadic lifestyle of the Cossacks caused them to be involved in nearly all the major disturbances in Russia over a 200 year period, including the rebellions led by Stepan Razin and Emilian Pugachev.[61]: 59

As Muscovy regained stability, discontent steadily grew within the serf and peasant populations. The Code of 1649, under Alexis Romanov, Mikhail's son, divided the Russian population into distinct and fixed hereditary categories.[61]: 52 The Code of 1649 increased tax revenue for the central government and stopped wandering to stabilize the social order by fixing people in the same land with the same occupation of their families. Peasants were tied to the land and townsmen were forced to take on their fathers' occupations. The increased taxes fell mainly on the peasants as a burden and continued to widen the gap between the wealthy and the poor. As the government developed more military expeditions, human and material resources became limited, putting an even harsher strain on the peasants. War with Poland and Sweden in 1662 led to a fiscal crisis and riots across the country.[61]: 58 Taxes, harsh conditions, and the gap between social classes drove peasants and serfs to flee, many of them going to the Cossacks, knowing that the Cossacks would accept refugees and free them.

The Cossacks experienced difficulties under Tsar Alexis as the influx of refugees grew daily. The Cossacks received a subsidy of food, money, and military supplies from the tsar in return for acting as border defense.[61]: 60 These subsidies fluctuated often and provided a source of conflict between the Cossacks and the government. The war with Poland diverted necessary food and military shipments to the Cossacks as the population of the Host, the unit of Cossacks identified by the region in which they resided, grew with the fugitive peasants. The influx of these refugees troubled the Cossacks not only because of the increased demand for food but also because the large number of these fugitives meant the Cossacks could not absorb them into their culture through the traditional apprenticeship way.[62]: 91 Instead of taking these steps of proper assimilation into Cossack society, the runaway peasants spontaneously declared themselves Cossacks and lived beside true Cossacks, laboring or working as barge-haulers to earn food.

As conditions worsened and Mikhail's son Alexis took the throne, divisions among the Cossacks began to emerge. Older Cossacks began to settle and become prosperous, enjoying the privileges they earned through obeying and assisting the Muscovite system.[62]: 90–91 [61]: 62 The old Cossacks started giving up their traditions and liberties that had been worth dying for to obtain the pleasures of an elite life. The lawless and restless runaway peasants that called themselves Cossacks looked for adventure and revenge against the nobility that had caused them suffering. These Cossacks did not receive the government subsidies that the old Cossacks enjoyed and thus had to work harder and longer for food and money. These divisions between the elite and lawless would lead to the formation of a Cossack army beginning in 1667 under Stenka Razin as well as to the ultimate failure of that rebellion.

Stenka Razin was born into an elite Cossack family and had made many diplomatic visits to Moscow before organizing his rebellion.[61]: 66–67 The Cossacks were Razin's main supporters and followed him during his first Persian campaign in 1667, plundering and pillaging Persian cities on the Caspian Sea. They returned ill and hungry, tired from fighting but rich with plundered goods in 1669.[62]: 95–97 Muscovy tried to gain support from the old Cossacks, asking the ataman, or Cossack chieftain, to prevent Razin from following through with his plans. However, the ataman, being Razin's godfather and swayed by Razin's promise of a share of the wealth from Razin's expeditions, replied that the elite Cossacks were powerless against the band of rebels. The elite did not see much threat from Razin and his followers either, although they realized he could cause them problems with the Muscovite system if his following developed into a rebellion against the central government.[62]: 95–96

Razin and his followers began to capture cities at the start of the rebellion in 1669. They seized the towns of Tsaritsyn, Astrakhan, Saratov, and Samara, implementing democratic rule and releasing peasants from slavery as they went.[62]: 100–105 Razin envisioned a united Cossack republic throughout the southern steppe in which the towns and villages of the area would operate under the democratic, Cossack style of government. These sieges often took place in the runaway peasant Cossacks' old towns, leading them to wreak havoc on their old masters and get the revenge for which they were hoping. The rebels' advancement began to be seen as a problem to the elder Cossacks, who, in 1671, decided to comply with the government in order to receive more subsidies.[61]: 112 On April 14, ataman Yakovlev led elders to destroy the rebel camp and captured Razin, taking him soon afterward to Moscow to be executed.

Razin's rebellion marked the beginning of the end to traditional Cossack practices. In August 1671, Muscovite envoys administered the oath of allegiance and the Cossacks swore loyalty to the tsar.[61]: 113 While they still had internal autonomy, the Cossacks became Muscovite subjects, a transition that would prove to be a dividing point yet again in Pugachev's Rebellion.

For the Cossack elite, a noble status within the empire came at the price of their old liberties in the 18th century. Advancement of agricultural settlement began forcing the Cossacks to give up their traditional nomadic ways and to adopt new forms of government. The government steadily changed the entire culture of the Cossacks. Peter the Great increased service obligations for the Cossacks and mobilized their forces to fight in far-off wars. Peter began establishing non-Cossack troops in fortresses along the Iaik River, and in 1734 a government fortress was constructed at Orenburg, giving Cossacks a subordinate role in border defense.[62]: 115 When the Iaik Cossacks sent a delegation to Peter to explain their grievances, Peter stripped the Cossacks of their autonomous status and subordinated them to the War College rather than the College of Foreign Affairs, solidifying the change in the Cossacks from border patrol to military servicemen. Over the next fifty years, the central government responded to Cossack grievances with arrests, floggings, and exiles.[62]: 116–117

Under Catherine the Great, beginning in 1762, the Russian peasants and Cossacks once again faced increased taxation, heavy military conscription, and grain shortages, as had characterized the land before Razin's rebellion. Although Peter III had extended freedom to former church serfs, freeing them from obligations and payments to church authorities, as well as freeing other peasants from serfdom, Catherine did not follow through on these reforms.[63] In 1767, the empress refused to accept grievances directly from the peasantry.[64] Peasants fled once again to the lands of the Cossacks; in particular, the fugitive peasants set their destination for the Iaik Host, whose people were committed to the old Cossack traditions. The changing government burdened the Cossacks as well, extending its reach to reform the Cossack traditions. Among ordinary Cossacks, hatred of the elite and central government boiled, and by 1772 an open state of rebellion ensued for six months between the Iaik Cossacks and the central government.[62]: 116–117

Emelian Pugachev, a low-status Don Cossack, arrived in the Iaik Host in late 1772[62]: 117 and claimed to be Peter III, stemming from the expectations of the Cossacks that Peter would have been an effective ruler had he not been assassinated in a plot by his wife Catherine II.[62]: 120 Many Iaik Cossacks believed Pugachev's claim, though those closest to him knew the truth. Others that may have known the truth but did not support Catherine II, due to her disposal of Peter III, still spread Pugachev's claim to be the late emperor.

The first of the three phases of Pugachev's Rebellion began in September 1773.[62]: 124 Cossacks who supported the elite constituted the majority of the first prisoners taken by the rebels. After a five-month siege of Orenburg, a military college became Pugachev's headquarters.[62]: 126 Pugachev began envisioning a Cossack tsardom, similar to Razin's vision of a united Cossack republic. The peasantry across Russia stirred with rumors and listened to manifestos issued by Pugachev. However, Pugachev's Rebellion soon came to be seen as an inevitable failure. The Don Cossacks refused to help the rebellion in the last phase of the revolt because they knew military troops followed Pugachev closely after lifting the siege of Orenburg and following Pugachev's flight from defeated Kazan.[62]: 127–128 In September 1774, Pugachev's own Cossack lieutenants turned him over to the government troops.[62]: 128

The Cossacks' opposition to centralization of political authority led them to participate in Pugachev's Rebellion.[62]: 129–130 Their defeat led the Cossack elite to accept government reforms in the hope of obtaining status in the nobility. The ordinary Cossacks had to follow and give up their traditions and liberties.

In the Russian Empire

From the start, relations of Cossacks with the Tsardom of Russia were varied; at times they supported Russian military operations, and at others conducted rebellions against the central power. After one of those uprisings at the end of the 18th century, Russian forces destroyed the Zaporozhian Host. Many of the Cossacks who chose to stay loyal to the Russian Monarch and continue their service later moved to the Kuban. Others choosing to continue a mercenary role escaped control by taking advantage of the large Danube delta.

By the 19th century, the Russian Empire had annexed the territory of the hosts and controlled them by providing privileges for their service. At this time the Cossacks served as military forces in many wars conducted by the Russian Empire. Cossacks were considered excellent for scouting and reconnaissance duties, as well as undertaking ambushes. Their tactics in open battles were generally inferior to those of regular soldiers such as the Dragoons. In 1840 the hosts included the Don, Black Sea, Astrakhan, Little Russia, Azov, Danube, Ural, Stavropol, Mesherya, Orenburg, Siberia, Tobolsk, Tomsk, Yeniseisk, Irkutsk, Sabaikal, Yakutsk and Tartar voiskos. By the 1890s the Ussuri, Semirechensk and Amur Cossacks were added; the last had a regiment of elite mounted rifles.[65]

By the end of the 19th century, the Cossack communities enjoyed a privileged tax-free status in the Russian Empire, although they had a 20-year military service commitment (this was reduced to 18 years from 1909). They were on active duty for five years, but could fulfill their remaining obligation with the reserves. At the beginning of the 20th century, the Russian Cossacks counted 4.5 million. They were organized as independent regional hosts, each comprising a number of regiments.

Treated as a separate and elite community by the Tsar, the Cossacks rewarded his government with strong loyalty. His administration frequently used Cossack units to suppress domestic disorder, especially during the Russian Revolution of 1905. The Imperial Government depended heavily on the perceived reliability of the Cossacks. By the early 20th century, their decentralized communities and semi-feudal military service were coming to be seen as obsolete. The Russian Army Command, which had worked to professionalize its forces, considered the Cossacks as less well disciplined, trained and mounted than the hussars, dragoons, and lancers of the regular cavalry.[66] The Cossack qualities of initiative and rough-riding skills were not always fully appreciated. As a result, Cossack units were frequently broken up into small detachments for use as scouts, messengers or picturesque escorts.

Cossacks between 1900 and 1917

In 1905, the Cossack hosts experienced deep mobilization of their menfolk amid the fighting of the Russo-Japanese War in Manchuria and the outbreak of revolution within the Russian Empire. Like other peoples of the empire, some Cossack stanitsas voiced some grievances against the regime by defying mobilization orders or devising relatively liberal political demands. Such infractions, however, were eclipsed by the prominent role played by Cossack detachments in stampeding demonstrators and restoring order in the countryside. Subsequently, the Cossacks were viewed by the wider population as instruments of reaction. Tsar Nicholas II reinforced this concept by issuing to new charters, medals and bonuses to Cossack units in recognition for their performance during the Revolution of 1905.[67][68]: 81–82

After the outbreak of World War I in August 1914, Cossacks became a key component in the cavalry of the Imperial Russian Army. The mounted Cossacks made up 38 regiments, plus some infantry battalions and 52 horse artillery batteries. Initially, each Russian cavalry division included a regiment of Cossacks in addition to regular units of hussars, lancers and dragoons. By 1916 the Cossacks' wartime strength had expanded to 160 regiments plus 176 independent sotnias (squadrons), the latter employed as detached units.[69][70]

After the opening phase of the war settled into a stalemate, the importance of cavalry in the frontlines faded accordingly. During the remainder of the war, Cossack units were dismounted to fight in trenches, held in reserve to exploit a rare breakthrough or assigned various duties in the rear that included rounding up deserters, providing escorts to war prisoners or razing villages and farms in accordance with Russia’s scorched earth policy.[71]

After the February Revolution, 1917

At the outbreak of disorders on 8 March 1917 that led to overthrow of the tsarist regime, approximately 3,200 Cossacks from the Don, Kuban, and Terek Hosts were stationed in Petrograd. Although they comprised only a fraction of the 300,000 troops in the proximity of the Russian capital, their general defection on the second day of unrest (10 March) enthused the raucous crowds and stunned the authorities and remaining loyal units.[3]: 212–215

In the aftermath of the February Revolution, the Cossacks hosts were authorized by the War Ministry of the Russian Provisional Government to overhaul their administrations. Cossack assemblies (known as krugs (or in the case of the Kuban Cossacks a rada) were organized at the regional level to elect atamans and pass resolutions. At the national level, an all-Cossack congress was convened in Petrograd and formed the Union of Cossack Hosts ostensibly to represent the interests of Cossacks across Russia.

During the course of 1917, the nascent Cossack governments formed by the krugs and atamans increasingly challenged the authority of the Provisional Government in the borderlands. The various Cossack governments themselves faced rivals in the form of national councils organized by neighboring minorities as well as soviets and zemstvos formed by non-Cossack Russians, especially the so-called "outlanders" who had immigrated to Cossack lands.[72]

Bolshevik Uprising and Civil War, 1917–1922

Soon after the Bolsheviks seized power in Petrograd on 7–8 November 1917, most Cossack atamans and their government refused to recognize the legitimacy of the new regime. The Don Cossack Ataman, Aleksey Kaledin, went as far as to invite opponents of the Bolsheviks to the Don Host.[73] However, the position of many Cossack governments was far from secure even within the boundaries of their hosts. In some areas soviets formed by outlanders and soldiers rivaled the Cossack government while ethnic minorities also tried to acquire a measure of self-rule. Even the Cossack communities themselves were divided as the atamans tended to represent the interests of prosperous landowners and the officer corps. On the other hand, poorer Cossacks and those serving in the army were susceptible to Bolshevik propaganda promising to spare “toiling Cossacks” from land appropriation.[74]: 50–51 [75]

As a result of the unwillingness of rank-and-file Cossack to vigorously defend the Cossack government, the Red Army was able to occupy the vast majority of Cossack lands by late spring of 1918. However, the Bolsheviks’ policy of requisitioning grain and foodstuffs from the countryside to supply Russia’s starving northern cities quickly fomented revolts among Cossack communities. These Cossack rebels elected new atamans and made common cause with other anticommunist forces, such as the Volunteer Army in South Russia. Subsequently, the Cossack homelands were transformed into bases for the White movement during the Russian Civil War.[74]: 53–63

Throughout the civil war, the Cossacks sometimes fought as an independent ally and other times as an auxiliary of White armies. In South Russia, the Armed Forces of South Russia (AFSR) under General Anton Denikin relied heavily on conscripts from the Don and Kuban Cossack Hosts to fill their ranks. Through the Cossacks, the White armies acquired experienced, skilled horsemen that the Red Army was unable to match until late in the conflict.[76] However, the relationship between the Cossack governments and the White leaders was frequently acrimonious. Cossack units were often ill-disciplined and prone to bouts of looting and violence that caused the peasantry to resent the Whites.[76]: 110–139 In Ukraine, Kuban and Terek Cossack squadrons carried out pogroms against Jews despite orders from Denikin condemning such activity.[74]: 127–128 Kuban Cossack politicians, wanting a semi-independent state of their own, frequently agitated against the AFSR command.[76]: 112–120 In the Russian Far East, anticommunist Transbaikal and Ussuri Cossacks undermined the rear of Siberia’s White armies by disrupting traffic on the Trans-Siberian Railway and engaging in acts of banditry that fueled a potent insurgency in that region.[77]

As the Red Army gained the initiative in the civil war during late 1919 and early 1920, Cossack soldiers, their families and sometimes entire stanitsas retreated with the Whites. Some continued to fight with the Whites in the conflict’s waning stages in the Crimea and Russian Far East. As many as 80,000–100,000 Cossacks eventually joined the defeated Whites in exile.[78]

Although the Cossacks were sometimes portrayed by Bolsheviks and, later, émigré historians as a monolithic counterrevolutionary group during the civil war, there were many Cossacks that fought with the Red Army throughout the conflict. Many poorer Cossack communities also remained susceptible to communist propaganda. In late 1918 and early 1919, widespread desertion and defection among Don, Ural and Orenburg Cossacks fighting with the Whites produced a military crisis that was exploited by the Red Army in those sectors.[74]: 50–51, 113–117 After the main White armies were defeated in early 1920, many Cossack soldiers switched their allegiance to the Bolsheviks and fought with the Red Army against the Poles and in other operations.[79]

Cossacks in the Soviet Union, 1917–1945

On 22 December 1917, the Council of People’s Commissars effectively abolished the Cossack estate by ending their military service requirements and privileges.[3]: 230 After the widespread anticommunist rebellions among Cossacks in 1918, the Soviet regime took a harder approach to Cossacks in early 1919 after the Red Army occupied Cossack districts in the Urals and northern Don. The Bolsheviks embarked on a genocidal policy of “de-Cossackization”. This policy was supposed to end the Cossack threat to the Soviet regime through resettlements, widespread executions of Cossack veterans from the White armies and favoring the outlanders within the Cossack hosts. Ultimately, the de-Cossackization campaign led to a renewed rebellion among Cossacks in Soviet-occupied districts and produced a new round of setbacks for the Red Army in 1919.[3]: 246–251

When the victorious Red Army again occupied Cossack districts in late 1919 and 1920, the Soviet regime did not officially reauthorize the implementation of de-Cossackization. There is, however, disagreement among historians as to the degree the Cossack people were persecuted by the Soviet regime. For example, the Cossack hosts were broken up among new provinces or autonomous republics. Some Cossacks, especially areas of the former Terek host, were resettled so their lands could be turned over to natives displaced from them during the initial Russian and Cossack colonization of the area. At the local level, the stereotype that Cossacks were inherent counterrevolutionaries likely persisted among some Communist officials, causing them to target or discriminate against Cossacks despite orders from Moscow to focus on class enemies among Cossacks rather than the Cossack people in general.[3]: 260–264

Rebellions in the former Cossack territories erupted occasionally during the interwar period. In 1920–1921, disgruntlement with continued Soviet grain requisitioning activities produced a series of revolts among Cossack and outlander communities in South Russia. The former Cossack territories of South Russia and the Urals also experienced a devastating famine in 1921–1922. In 1932–1933, another famine devastated Ukraine and some parts of South Russia. That famine caused a population decline of about 20–30% in these territories (the population decline in the rural areas, populated largely by ethnic Cossacks, was even higher, since urban areas were less affected by the famine); Robert Conquest estimates the number of famine-related deaths in the Northern Caucasus to be about 1 million.[80] Government officials expropriated grain and other produce from rural Cossack families, leaving them to starve and die.[81] Many families were forced from their homes in the severe winter and froze to death[81] — Mikhail Sholokhov's letters to Joseph Stalin document the conditions and widespread deaths, as do eyewitness accounts.[81] Besides starvation, the collectivization and dekulakization campaigns of the early 1930s threatened Cossacks with the risks of deportation to labor camps or outright execution by Soviet security organs.[74]: 206–219

In April 1936, the Soviet regime began to relax its restrictions on Cossacks by allowing Cossacks to serve openly in the Red Army. Two existing cavalry divisions were renamed as Cossack ones while three new Cossack cavalry divisions were established. Under the new Soviet designation, anyone from the former Cossack territories of the North Caucasus—as long as they did not belong to the Circassians or other ethnic minorities—could claim Cossack status.

During the German invasion of the Soviet Union during World War II, many Cossacks continued to serve in the Red Army. Some fought as cavalry in the Cossack divisions, such as the 17th Kuban Cossack Cavalry Corps, which later given the honorific “guard” designation in recognition of its overall stellar performance.[3]: 276–277 Other Cossacks fought as partisans though it must be pointed out that the partisan movement did not acquire significant traction during the German occupation of the traditional Cossack homelands in the North Caucasus.[82]

Anticommunist Cossacks in Exile and World War II, 1920–1945

The Cossack emigration consisted largely of relatively young men who had served and retreated with the White armies. Although they were hostile to communism, the Cossack émigrés remained broadly divided over whether their people should pursue a separatist course to acquire independence or retain their close ties with a future post-Soviet Russia. Many quickly became disillusioned with life abroad. Subsequently, throughout the 1920s thousands of exiled Cossacks voluntarily returned to Russia through repatriation efforts sponsored by France, the League of Nations and even the Soviet Union.[83]

The Cossacks who remained abroad settled primarily in Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia, France, Xinjiang and Manchuria. Some Cossacks managed to create farming communities in Yugoslavia and Manchuria, but most eventually took up employment as laborers in construction, agriculture or industry. A few showcased their lost culture to foreigners by performing stunts in circuses or serenading audiences in choirs.

Cossacks who were determined to carry on the fight against communism frequently found employment with foreign powers hostile to Soviet Russia. In Manchuria, thousands of Cossacks and White émigrés enlisted in the army of that region’s warlord, Zhang Zoulin. After Japan’s Kwantung Army occupied Manchuria in 1932, the Ataman of the Transbaikal Cossacks, Grigory Semyonov, led collaboration efforts between Cossack émigrés and the Japanese military.[84]

In the initial phase of Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union, Cossack émigrés were initially barred from political activity or travelling into the occupied Eastern territories. Hitler also had no intention of entertaining the political aspirations of the Cossacks or any minority group in the USSR. As a result, collaboration between Cossacks and the Wehrmacht began in ad hoc manner through localized agreements between German field commanders and Cossack defectors from the Red Army. It was not until the second year of the Nazi-Soviet conflict when Hitler officially sanctioned the recruitment of Cossacks and lifted the restrictions imposed on émigrés. During their brief occupation of the North Caucasus region, the Germans actively recruited Cossacks into detachments and local self-defense militias. The Germans even experimented with a self-governing district formed from Cossack communities in the Kuban region. When the Wehrmacht withdrew from the North Caucasus region in early 1943, tens of thousands of Cossacks retreated with them either out of conviction or to avoid Soviet reprisals.[74]: 229–239, 243–244

In 1943, the Germans formed the 1st Cossack Cavalry Division under the command of General Helmuth von Pannwitz. Most of its ranks were comprised of deserters from the Red Army though many of its officers and NCO’s were Cossack émigrés who received training at one of the cadet schools established by the White Army in Yugoslavia. The division was deployed to occupied Croatia to fight Tito’s Partisans where it generally acquitted itself effectively though at times brutally. In late 1944, the 1st Cossack Cavalry Division was admitted into the Waffen-SS and enlarged into the XV SS Cossack Cavalry Corps.[85]: 110–126, 150–169

In late 1943, the Reich Ministry for the Occupied Eastern Territories and Wehrmacht headquarters issued a joint proclamation promising the Cossacks independence once their homelands were “liberated” from the Red Army.[85]: 140 The Germans followed up that proclamation by setting up the Cossack Central Administration under the leadership of the former Ataman of the Don Cossacks, Pyotr Krasnov. Though it contained many attributes of a government-in-exile, the Cossack Central Administration lacked any control over foreign policy or deployment of Cossack troops in the Wehrmacht. In early 1945, Krasnov and his staff joined a group of 20,000–25,000 Cossack refugees and irregulars known as “Cossachi Stan”. This group, which was then led by Timofey Domanov, had fled the North Caucasus alongside the Germans in 1943 and was moved between Kamenets-Podolsk in Ukraine, Navahrudek in Belarus and Tolmezzo, Italy.[74]: 252–254

In the closing days of WWII in early May 1945, both Domanov’s Cossack Stan and Pannwitz’s XV SS Cossack Cavalry Corps retreated into Austria, where they surrendered to the British. Many Cossack's accounts allege that they or their leaders had been given a guarantee from British officers that they would not be forcibly repatriated to the Soviet Union,[86] but there is no hard evidence of that such a promise was made. At the end of the month and in early June 1945, the majority of Cossacks from both groups were transferred to the Red Army and SMERSH custody at the Soviet demarcation line in Judenburg, Austria. This episode is known as the Betrayal of the Cossacks and resulted in sentences of hard labor or execution for the majority of the repatriated Cossacks.[74]: 263–289

Modern times

Following the war, Cossack units, along with cavalry in general, were rendered obsolete and released from the Soviet Army. In the post-war years, many Cossack descendants were thought of as simple peasants, and those who lived inside an autonomous republic usually gave way to the particular minority and migrated elsewhere (particularly, to the Baltic region).[citation needed]

During the Perestroika era of the Soviet Union of the late 1980s, many descendants of the Cossacks became enthusiastic about reviving their national traditions. In 1988, the Soviet Union passed a law which allowed formation of former hosts and the creation of new ones. The ataman of the largest, the All-Mighty Don Host, was granted Marshal rank and the right to form a new host. Simultaneously, many attempts were made to increase the Cossack impact on Russian society, and throughout the 1990s many regional authorities agreed to hand over some local administration and policing duties to the Cossacks.

According to 2002 Russia's population census, there are 140,028 people who currently self-identify as ethnic Cossacks,[87] while at the same time, between 3.5 and 5 million people associate themselves with the Cossack identity in post-Soviet Russia and around the world.[88][89]

Cossacks have taken an active part in many of the conflicts that have taken place since the disintegration of the Soviet Union: the War of Transnistria,[90] the Georgian–Abkhazian conflict, the Georgian–Ossetian conflict, the First Chechen War and the Second Chechen War, as well as the 2014 pro-Russian unrest in Ukraine and subsequent War in Donbass.[91][92]

Culture and organization

In early times an ataman (later called hetman) commanded a Cossack band. He was elected by the tribe members at a Cossack rada, as were the other important band officials: the judge, the scribe, the lesser officials, and the clergy. The ataman's symbol of power was a ceremonial mace, a bulava. Today, Russian Cossacks are led by Atamans, and Ukrainian Cossacks by Hetmans.

After the split of Ukraine along the Dnieper River by the Polish–Russian Treaty of Andrusovo in 1667, Ukrainian Cossacks were known as Left-bank and Right-bank Cossacks. The ataman had executive powers, and at time of war, he was the supreme commander in the field. Legislative power was given to the Band Assembly (Rada). The senior officers were called starshyna. In the absence of written laws, the Cossacks were governed by the "Cossack Traditions" – the common, unwritten law.

Cossack society and government were heavily militarized. The nation was called a host (vois’ko, or viys’ko, translated as 'army'). The people and territories were subdivided into regimental and company districts, and village posts (polky, sotni, and stanytsi). A unit of a Cossack troop could be called a kuren. Each Cossack settlement, alone or in conjunction with neighbouring settlements, formed military units and regiments of light cavalry (or mounted infantry in the case of Siberian Cossacks). They could respond to a threat on very short notice.

A high regard for education was a tradition among the Cossacks of Ukraine. In 1654, when the Patriarch of Antioch, Makarios, traveled to Moscow through Ukraine, his son, Deacon Paul Allepscius, wrote the following report:

All over the land of Rus', i.e., among the Cossacks, we have noticed a remarkable feature which made us marvel; all of them, with the exception of only a few among them, even the majority of their wives and daughters, can read and know the order of the church-services as well as the church melodies. Besides that, their priests take care and educate the orphans, not allowing them to wander in the streets ignorant and unattended.[93]

Settlements

Russian Cossacks founded numerous settlements (called stanitsas) and fortresses along troublesome borders. These included forts Verny (Almaty, Kazakhstan) in south Central Asia; Grozny in North Caucasus; Fort Alexandrovsk (Fort Shevchenko, Kazakhstan); Krasnovodsk (Turkmenbashi, Turkmenistan); Novonikolayevskaya stanitsa (Bautino, Kazakhstan); Blagoveshchensk; and towns and settlements along the Ural, Ishim, Irtysh, Ob, Yenisei, Lena, Amur, Anadyr (Chukotka), and Ussuri Rivers. A group of Albazin Cossacks settled in China as early as 1685.