Turkish language

| Turkish | |

|---|---|

| Türkçe | |

| Pronunciation | [tyɾktʃe] |

| Native to | Turkey, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Greece, Republic of Macedonia, Kosovo, Romania, Azerbaijan, and by immigrant communities in Germany, France, The Netherlands, Austria, Uzbekistan, United States, Belgium, Switzerland, and other countries of the Turkish diaspora |

| Region | Turkey, Cyprus, Balkans, Caucasus |

Native speakers | approx. 50[1]–65[2] million native |

| Latin alphabet (Turkish variant) | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | Turkey, Cyprus, Northern Cyprus, Kosovo, Republic of Macedonia* *In municipalities inhabited by a set minimum percentage of speakers. |

| Regulated by | Turkish Language Association |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | tr |

| ISO 639-2 | tur |

| ISO 639-3 | tur |

(Click on image for the legend) | |

Turkish ([Türkçe] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)) is a language belonging to the Turkic language family, spoken predominantly in Turkey, with smaller communities of speakers in Bulgaria, Cyprus, Greece, the Republic of Macedonia, and Romania, as well as by several million emigrants in Western Europe[1][4]. Turkish is the largest member of the Turkic language family in terms of the number of speakers, with some 50[1]–65[2] million native speakers. There is a high degree of mutual intelligibility between Turkish and other Oghuz languages, including Azeri, Turkmen, and Qashqai, and if these are counted together as "Turkish", the number of native speakers is close to 90 million.

Turkish is characterized by vowel harmony, agglutination, lack of grammatical gender, and a highly phonetic spelling.

Classification

Turkish is a member of the Turkish, or Western, subgroup of the Oghuz languages, which also includes Gagauz and Azeri. The Oghuz languages form a subgroup of the Turkic languages, which some linguists believe to be a part of a larger Altaic language family[3].

The most distinguishing characteristics of Turkish in comparison to most other languages are vowel harmony and extensive agglutination. The basic word order of Turkish is Subject Object Verb. Turkish has a T-V distinction: second-person plural forms can be used for individuals as a sign of respect. Turkish also has no noun classes or grammatical gender.

Geographic distribution

Turkish is natively spoken by the Turkish people in Turkey and by the Turkish diaspora in some 30 other countries. In particular, Turkish speaking minorities exist in countries that formerly (in whole or part) belonged to the Ottoman Empire, such as Bulgaria, Cyprus, Greece (primarily in Western Thrace), the Republic of Macedonia, Romania, and Serbia[1]. More than two million Turkish speaking people live in Germany, and there are significant Turkish speaking communities in France, the Netherlands, Austria, Belgium, Switzerland and the United Kingdom[4]. But due to the desegregation of the Turkish immigrants into the country where they immigrated to, not every ethnic Turkish immigrant speaks the language as well as a native Turk would speak it.

The exact number of native speakers in Turkey is uncertain, primarily due to a lack of minority language data. Turkish is spoken as a first or second language by almost all of Turkey's residents, with Kurdish making up most of the remainder (about 3,950,000 as estimated in 1980)[5]. However, the vast majority of the linguistic minorities in Turkey are bilingual, speaking Turkish as a second language to levels of native fluency.

Official status

Turkish is the official language of Turkey, and is one of the official languages of Cyprus. It also has official (but not primary) status in several municipalities of Republic of Macedonia, depending on the concentration of Turkish-speaking local population as well as the Prizren District of Kosovo.

In Turkey, the regulatory body for Turkish is the Turkish Language Association (Turkish: Türk Dil Kurumu - TDK), which was founded in 1932 under the name Türk Dili Tetkik Cemiyeti ("Society for Research on the Turkish Language"). The Turkish Language Association was influenced by the linguistic purism ideology and one of its primary acts was the replacement of loanwords and foreign grammatical constructs in the language with their Turkish equivalents, which, together with the adoption of the new Turkish alphabet in 1928, shaped the modern Turkish language as it is in use today (details covered in the section on language reform, further below). TDK became an independent body in 1951, with the lifting of the requirement that it should be presided over by the Minister of Education. This status continued until August, 1983, when it was again tied to the government with the constitution of 1982 following the military coup d'état of 1980.[6]

Dialects

The Istanbul dialect of Turkish (İstanbul Türkçesi) is established as the official standard language within Turkey. In spite of the levelling influence of the standard used in mass media and Turkish education system since the 1930s, a considerably rich dialectal variation persists[7]. Academically, researchers from Turkey often refer to Turkish dialects as ağız or şive, leading to an ambiguity with the linguistic concept of accent, which is also covered with these same words. Projects investigating Turkish dialects are being carried out by several universities, as well as a dedicated work group of the Turkish Language Association and work is currently in progress for the compilation and publication of the research as a comprehensive dialect atlas of the Turkish language.[8][9]

Main dialects of Turkish include:

- İstanbul, the standard dialect

- Rumelice, spoken by immigrants from Rumelia, including the peculiar dialects of Dinler and Adakale

- Kıbrıs, Cypriot Turkish, spoken on the island of Cyprus

- Edirne, spoken in Edirne

- Doğu, spoken in Eastern Anatolia, has a dialect continuum with Azerbaijani in some areas

- Karadeniz, spoken in the Eastern Black Sea Region and is represented primarily by the Trabzon dialect, which exhibits some substratum influence from Greek in phonology and syntax[10]

- Ege, spoken in the Aegean region and extending to Antalya

- Güneydoğu, spoken in the south, to the east of Mersin

- Orta Anadolu, spoken in the Central Anatolia region

- Kastamonu, spoken in Kastamonu and vicinity

- Karamanlıca, spoken in Greece, where it is also named Kαραμανλήδικα (Karamanlidika), and is also the literary standard for Karamanlides

Sounds

One characteristic feature of Turkish is vowel harmony, meaning that a word will have either front or back vowels, but not both. For example, in vişne ("sour cherry"), i is a closed unround front vowel and e is an open unround front vowel. Stress is usually on the last syllable, with the exception of some suffix combinations, and words like masa ('masa). Also, in the use of proper names, the stress is transferred to the syllable before the last (e.g. İstánbul), although there are exceptions to this (e.g. Ánkara).

Consonants

| Bilabial | Labio- dental |

Dental | Alveolar | Post- alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | Glottal | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plosives | p | b | t | d | c | ɟ | k | ɡ | ||||||||

| Nasals | m | n | ||||||||||||||

| Fricatives | f | v | s | z | ʃ | ʒ | ɣ | h | ||||||||

| Affricates | tʃ | dʒ | ||||||||||||||

| Tap | ɾ | |||||||||||||||

| Approximant | j | |||||||||||||||

| Lateral approximants |

ɫ | l | ||||||||||||||

The phoneme /ɣ/ usually referred to as "soft g"(yumuşak g), ğ in Turkish orthography, actually represents a rather weak front-velar or palatal approximant between front vowels. It never occurs at the beginning of a word, but always follows a vowel. When word-final or preceding another consonant, it lengthens the preceding vowel.

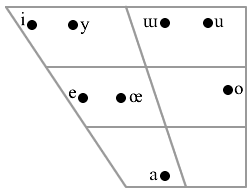

Vowels

| IPA chart for Turkish monophthongs |

|---|

|

The vowels of the Turkish language are, in their alphabetical order, a, e, ı, i, o, ö, u, ü. There are no diphthongs in Turkish and when two vowels come together, which occurs rarely and only with loanwords, each vowel retains its individual sound.

| Vowel sound | Example | |||

| IPA | Description | IPA | Orthography | English translation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| monophthongs | ||||

| i | Close front unrounded vowel | dil | dil | 'tongue', 'language' |

| y | Close front rounded vowel | gy'neʃ | güneş | 'sun' |

| ɯ | Close back unrounded vowel | ɯˈɫɯk | ılık | 'mild' |

| e | Close-mid front unrounded vowel | jel | yel | 'wind' |

| œ | Open-mid front rounded vowel | gœɾ | gör- | 'to see' |

| a | Open front unrounded vowel | dal | dal | 'branch' |

| o | Close-mid back rounded vowel | jol | yol | 'way' |

| u | Close back rounded vowel | utʃak | uçak | 'airplane' |

Grammar

Turkish is an agglutinative language and as such has an abundance of suffixes, but no native prefixes, apart from the reduplicating intensifier prefix as in beyaz ("white"), bembeyaz ("very white"), sıcak ("hot"), sımsıcak ("very hot"). One word can have many suffixes and these can also be used to create new words (like creating a verb from a noun, or a noun from a verbal root, see Vocabulary section further below) or to indicate the grammatical function of the word.

Nouns and adjectives

Turkish nouns can take endings indicating the person of a possessor. They are declined by taking case-endings, as in Latin. There are six noun cases in the Turkish declension system:

- Nominative

- Genitive, formed by adding -ın, -in, -un or -ün, according to the vowel harmony

- Dative, formed by adding -a or -e, according to the vowel harmony

- Accusative, formed by adding -ı, -i, -u or -ü, according to the vowel harmony

- Ablative, formed by adding -den or -dan, according to the vowel harmony

- Locative, formed by adding -de or -da, according to the vowel harmony

- Instrumental. There is also a very common practice of adding the postposition ile, meaning with, as a suffix to the end of nouns (-le or -la, again according to the vowel harmony) which could be treated as an instrumental case.

Taking gün ("day") as an example:

| Turkish | English | Noun case |

|---|---|---|

| gün | (the) day | Nominative |

| günün | a day's the day's of the day |

Genitive |

| güne | to the day | Dative |

| günü | the day | Accusative |

| günden | of/from the day | Ablative |

| günde | in the day | Locative |

| günle | with the day | Instrumental |

The series of case-endings is the same for every noun, selecting the suffix complying with the vowel harmony. The initial consonant of the suffixes for the ablative and locative cases can also vary depending on the last consonant of the noun being voiced or unvoiced, such as having hava ("air") + -da (locative suffix) = havada ("in the air"), but, ağaç ("tree") + -da (locative suffix) = ağaçta ("on the tree"), instead of ağaçda.

Additionally, nouns can take suffixes that give them a person and make them into sentences:

|

|

It is often cited, humorously, that the longest Turkish word ever formed was "Çekoslovakyalılaştıramadıklarımızdan mıydınız?" which literally means "Were you one of the people we couldn't turn into (or: pass off as) a Czechoslovakian?", although it is always possible to form words longer than any given length via repetitive usage of some derivative suffix. The shortest word in Turkish is "o", the third person singular personal pronoun (corresponding to he, she, and it in English).

Turkish adjectives as such are not declined, though they can generally be used as nouns, in which case they are declined. Used attributively, adjectives precede the nouns they modify. The adjectives var ("existent") and yok ("non-existent") are used in many cases where English would use "there is" or "have", e.g. süt yok ("there is no milk", lit. "(the) milk (is) non-existent"); the construction "noun 1-GEN noun 2-POSS var/yok" can be translated "noun 1 has/doesn't have noun 2"; imparatorun elbisesi yok "the emperor has no clothes" ("(the) emperor-of clothes-his non-existent"); kedimin ayakkabıları yoktu ("my cat had no shoes", lit. "cat-my-of shoe-plur.-its non-existent-past tense").

Personal pronouns

| Turkish | English |

|---|---|

| Ben | I |

| Sen | You (singular) |

| O | He, she, it |

| Biz | We |

| Siz | You (plural, also singular formal) |

| Onlar | They |

Verbs

Turkish verbs exhibit person. Again with the use of suffixes, they can be made negative or impotential; they can also be made potential. Finally, Turkish verbs exhibit various distinctions of tense (present, past, inferential, future, and aorist), mood (conditional, imperative, necessitative, and optative), and aspect.

| Turkish | English |

|---|---|

| gel- | (to) come |

| gelme- | not (to) come |

| geleme- | not (to) be able to come |

| gelebil- | (to) be able to come |

| Gelememiş | She (or he) was apparently unable to come. |

| Gelememişti | She had not been able to come. |

| Gelememiştiniz | You (plural) had not been able to come. |

| Gelememiş miydiniz? | Have you (plural) not been able to come? |

All Turkish verbs are conjugated the same way, except for the irregular and defective verb i-, the Turkish copula, which can be used in compound forms (the shortened form is called an enclitic): Gelememişti = Gelememiş idi = Gelememiş + i- + -di

Vowel harmony

"Vowel harmony" is the principle by which a native Turkish word generally incorporates either exclusively back vowels (a, ı, o, u) or exclusively front vowels (e, i, ö, ü). As such, a notation for a Turkish suffix such as -den means either -dan or -den, whichever promotes vowel harmony; a notation such as -iniz means either -ınız, -iniz, -unuz, or -ünüz, again with vowel harmony constituting the deciding factor.

The Turkish vowel harmony system can be considered as being 2-dimensional, where vowels are characterised by two features: front/back and rounded/unrounded (see the table).

| Front | Back | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unrounded | Rounded | Unrounded | Rounded | |

| High | i | ü | ı | u |

| Low | e | ö | a | o |

Front/back harmony

Vowel harmony states that a word may not contain both front and back vowels. Therefore, most grammatical suffixes come in front and back forms, e.g. yüzeyde ("on the surface") but kapıda ("on/at the door").

Rounding harmony

In addition, there is a secondary rule that i and ı tend to become ü and u respectively after rounded vowels, so certain suffixes have additional forms. This gives constructions such as Türkiye'dir ("it is Turkey"), kapıdır ("it is the door"), but gündür ("it is the day"), paltodur ("it is the coat").

Exceptions

Compound words are considered separate words with regards to vowel harmony: vowels do not have to harmonize between the constituent words of the compound (thus forms like bu|gün ("today") or baş|kent ("capital") are permissible). In addition, vowel harmony does not apply for loanwords and some invariant suffixes, such as -iyor, the conjugation suffix for the present tense; there are also a few native Turkish words that do not follow the rule, such as anne ("mother"). In such words suffixes harmonize with the final vowel; thus İstanbul'dur ("it is İstanbul").

Word order

Word order in Turkish is generally Subject Object Verb, as in Japanese and Latin, but not English. However, it is possible to alter the word-order according to which word or phrase is to carry the stress. The main rule is that "the word before the verb has the stress" without exception. For example, if we want to say "Hakan went to school" with a stress on the word "school" (okul, the indirect object) we shall say "Hakan okula gitti". If we want the stress occur to the word "Hakan" (the subject), we shall say "Okula Hakan gitti" which means "it's Hakan who went to school".

The relative clauses are easily reproduced by a construction so-called "eylemsi" or "fiilimsi" ("verbals"). A demonstration of this can be seen in the following sentence from a newspaper (Cumhuriyet, August 16, 2005, p. 1). The sentence incorporates all available noun cases except the genitive:

- Türkiye'de modayı gazete sayfalarına taşıyan,

- gazetemiz yazarlarından N. S. yaşamını yitirdi:

| Turkish | English | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| Türkiye'de | in Turkey | locative |

| modayı | fashion | accusative of moda ("fashion") |

| gazete | newspaper | nominative |

| sayfalarına | to its pages | dative; sayfa ("page"), sayfalar ("pages"), sayfaları ("its pages") |

| taşıyan, | carrying | present participle of taşı- |

| gazetemiz(in) | (of) our newspaper | nominative; gazete ("newspaper") |

| yazarlarından | from its writers | plural ablative; yazar ("writer") |

| N. S. | [person's name] | nominative |

| yaşamını | her life | accusative; yaşam ("life") |

| yitirdi. | lost | past tense of yitir- ("lose") from yit- ("be lost") |

Which ultimately translates to:

- "One of the writers of our newspaper, N. S.,

- who brought fashion to newspaper pages in Turkey, lost her life."

where "taşıyan" is the "verbal" corresponding to "who brought" in the English translation.

Vocabulary

Number of words

The 2005 edition of Güncel Türkçe Sözlük, the official dictionary of the Turkish language published by Turkish Language Association, contains 104,481 entries, of which about 14% are of foreign origin[11]. Among the most significant foreign contributors to Turkish vocabulary are Arabic, French, Persian, Italian, English, and Greek[12].

Word derivation

Turkish extensively utilizes its agglutinative nature to form new words from former nouns and verbal roots. The majority of the Turkish words originate from the application of derivative suffixes to a relatively small set of core vocabulary.

An example set of words derived agglutinatively from a substantive root:

| Turkish | Parts | English | Word class |

|---|---|---|---|

| göz | göz | eye | Noun |

| gözlük | göz + -lük | eyeglasses | Noun |

| gözlükçü | göz + -lük + -çü | someone who sells eyeglasses | Noun |

| gözlükçülük | göz + -lük + -çü + -lük | the business of selling eyeglasses | Noun |

| gözlüklenmek | göz + -lük + -len + -mek | becoming an eyeglasses owner | Verb |

| gözlem | göz + -lem | observation | Noun |

| gözlemek | göz + -le + -mek | to observe | Verb |

| gözlemci | göz + -lem + -ci | observer | Noun |

Another example starting from a verbal root:

| Turkish | Parts | English | Word class |

|---|---|---|---|

| yat- | yat- | to lie down | Verb |

| yatık | yat- + -(ı)k | laid, leaned | Adjective |

| yatak | yat- + -ak | bed, place to sleep | Noun |

| yatay | yat- + -ay | horizontal | Noun |

| yatkın | yat- + -gın | who is inclined to, who favors | Noun |

| yatır- | yat- + -(ı)r- | to lay down (that is, to cause to lie down) | Verb |

| yatırım | yat- + -(ı)r- + -(ı)m | instance of laying down: deposit, investment | Noun |

| yatırımsız | yat- + -(ı)r- + -(ı)m + -sız | without an investment | Adjective |

| yatırımcı | yat- + -(ı)r- + -(ı)m + -cı | depositor, investor | Noun |

New words are also frequently formed by compounding two existing words into a new one, very much like in German. A few examples of compound words are given below:

| Turkish | English | Constituent words | Literal meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pazartesi | Monday | Pazar ("Sunday") and ertesi ("after") | After Sunday |

| bilgisayar | computer | bilgi ("information") and say- ("to count") | Information counter |

| gökdelen | skyscraper | gök ("sky") and del- ("to pierce") | Sky piercer |

| başparmak | thumb | baş ("prime") and parmak ("finger") | Primary finger |

| katsayı | multiplier | kat ("level") and sayı ("number") | Level number(ing) |

History

Early history

The first records of the Turkic languages currently attested date back to the 8th century C.E., when two monumental inscriptions were erected in the Orkhon Valley in honour of the Göktürk prince Kul Tigin and his brother Emperor Bilge Khan, between 732 and 735. After the discovery and excavation of the monuments and associated stone slabs in the wider area by Russian archaeologists between 1889-93, it became established that the language on the inscriptions was the Old Turkic language written using the Orkhon script, which has also been referred to as Turkic runes or runiform due to an external similarity to the runic alphabets[13].

With the Turkic expansion during Early Middle Ages (c. 6th - 11th centuries), peoples speaking Turkic languages spread across Central Asia, covering a very broad geographical region stretching from Siberia to Europe and the Mediterranean. The Seljuqs of the Oghuz Turks, in particular, brought their language (Oghuz Turkic), the direct ancestor of today's Turkish language, into Anatolia during 11th century[14].

Also during the 11th century, an early linguist of the Turkic languages, Kaşgarlı Mahmud from the Kara-Khanid Khanate, published the first comprehensive dictionary of Turkic languages, the Compendium of the Turkic Dialects (Ottoman Turkish: Divânü Lügati't-Türk), which also included the first known map of the geographical distribution of Turkic speakers[15].

Ottoman Turkish

Following the adoption of Islam c. 950 C.E. by the Kara-Khanid Khanate and the Seljuq Turks, regarded as the cultural ancestors of the Ottomans, the administrative language of these states acquired a rather large collection of loanwords from Arabic and Persian, consecutively influencing Turkish. Turkish literature during the Ottoman period, in particular Ottoman Divan poetry, was heavily influenced by Persian forms, including the adoption of Persian poetic meters and ultimately the bringing of Persian words into the language in great numbers. During the course of over six hundred years of the Ottoman Empire (c. 1299-1922), the literary and official language of the empire was a mixture of Turkish, Persian and Arabic, which differed considerably from everyday spoken Turkish of the time, and is now given the name Ottoman Turkish.

Language reform and Modern Turkish

After the foundation of the Republic of Turkey, the Turkish Language Association (Turkish: Türk Dil Kurumu - TDK) was established under the patronage of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk in 1932, with the aim of conducting research on Turkish language. One of the tasks of the newly established association was to initiate a language reform replacing loanwords of Arabic and Persian origin in the language with Turkish equivalents. The language reform was a part of the ongoing cultural reforms of the time, which were in turn a part in the broader framework of Atatürk's Reforms. In 1928, the Ottoman Turkish alphabet, derived from the Arabic script, was abolished in favor of the new Latin-based Turkish alphabet, greatly helping to increase the literacy rate of the population. By banning the usage of replaced loanwords in the press, the association succeeded in removing several hundred foreign words from the language. While most of the words introduced to the language by the TDK were newly derived from Turkic roots, TDK also opted for reviving Old Turkish words which had not been used in the language for centuries[6].

Due to this sudden change in the language, older and younger people in Turkey tend to express themselves with a different vocabulary. While the generations born before the 1940s tend to use the old Arabic origin words, the younger generations favor using new expressions. Some new words are not used as often as their old counterparts or have failed to convey the intrinsic meanings of their old equivalents. There is also a political significance to the old versus new debate in the Turkish language and conservative divisions of the society also tend to use older words in the press or daily language. Therefore, the preferred vocabulary, to some degree, is also indicative of the adoption of or resistance to Atatürk's Reforms which took place more than 70 years ago. The last few decades saw the continuing work of the TDK to coin new Turkish words to account for new concepts / technologies as they enter the language as new loanwords (mostly from English). A great many of these new words, particularly IT terms, received widespread acceptance, but the association is occasionally criticized for coining words that obviously seem or sound like "invented".

It is also worthy of note that a non-negligible amount of the words derived by TDK live together with their old counterparts. The different words —some originating from Old Turkic or derived by TDK, and some borrowed from Arabic, Persian, or one of the European languages, especially French— having exactly the same literal meaning are used to express slightly different meanings, especially when speaking about abstract subjects, giving rise to a situation quite like the coexistence of Germanic words and words originating from Romance languages in English.

Among some of the old words that were replaced are terms in geometry, cardinal directions, some months' names and many nouns and adjectives. Some examples of modern Turkish words and the old loanwords are:

| Ottoman Turkish word | Modern Turkish word | English meaning | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| müselles | üçgen | triangle | compound of the noun üç ("three") and the very old Turkic noun gen ("tension", "side") |

| tayyare | uçak | airplane | derived from the verb uçmak ("to fly") |

| nispet | oran | ratio | the old word is still used in the language today together with the new one |

| şimal | kuzey | north | derived from the Old Turkic noun kuz ("cold and dark place") |

| Teşrini-evvel | Ekim | October | the noun ekim means "the action of planting", referring to the planting of cereal seeds in autumn, which is widespread in Turkey |

See the list of replaced loanwords in Turkish for an extensive collection of replaced and current loanwords in Turkish.

Writing system

Turkish is written using the Turkish alphabet, a modified version of the Latin alphabet, which was introduced in 1928 by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk as an important step in the cultural reforms of the period, replacing the Ottoman Turkish alphabet previously in use. The work of preparing the new alphabet and selecting the necessary modifications to account for sounds specific to Turkish language, was appointed to the Dil Encümeni (Language Commission) including Falih Rıfkı Atay, Yakup Kadri Karaosmanoğlu, Ruşen Eşref Ünaydın, Ahmet Cevat Emre, Ragıp Hulûsi Özdem, Fazıl Ahmet Aykaç, Mehmet Emin Erişirgil and İhsan Sungu. The introduction of the new Turkish alphabet was supported by Public Education Centers opened throughout the country, cooperation with publishing companies, and encouragement by Atatürk himself in trips to the countryside teaching the new letters to the public[16].

The Turkish spelling is highly phonetic, and the sounds of the individual letters exhibit few surprises for English speakers. Following International Phonetic Alphabet conventions on phonetic transcription, angle brackets < > here are used to enclose written letters, and brackets [ ] are used to enclose symbols that represent the sounds. Most writing-sound correspondences can be predicted by English speakers, with the following exceptions. The <c> denotes /dʒ/, like <j> in English jail. The <ç> denotes /tʃ/ like the <ch> in English church. The <j> represents /ʒ/ like the <g> in rouge, it is identical to French <j> and is almost entirely used in loanwords of French origin. The <ş> represents /ʃ/ like the <sh> in sheet. The <ı> represents /ɨ/, a sound which does not exist in English. The <ğ> denotes /ɣ/ which may be manifested by lengthening the precedent vowel and assimilating any subsequent vowel (e.g., soğuk ("cold") is pronounced [souk])—except for the two highly irregularly spelled verbs döğmek ("to hit") and öğmek ("to praise"), where <ğ> denotes [v].

The effect of Atatürk's introduction of the adapted Roman alphabet was a dramatic increase in literacy from Third World levels to nearly one hundred percent. It is critical to note that, for the first time, Turkish had an alphabet that was actually suited to the sounds of the language; the Arabic alphabet, which was hitherto in use, commonly shows only three different values for vowels (the consonants waw and yud, atop which the long 'u' and 'i' sounds, respectively, are occasionally multiplexed, and the alif, which can carry long medial 'a' or any initial vowel). It lacked several vital consonants, and on the other hand had redundancies with several other consonant sounds such as /z/ (these letters were pronounced differently in Arabic but were conflated in Turkish). The lack of discrimination among vowels is serviceable in Arabic (which sports few vowel sounds to begin with) but intolerable in Turkish, which features eight fundamental vowel sounds.

Example

Dostlar Beni Hatırlasın by Aşık Veysel Şatıroğlu (1894-1973), a minstrel and highly regarded poet of the Turkish literature.

| Original | IPA | Translation |

|---|---|---|

| Ben giderim adım kalır | ben gideɾim adɯm kalɯɾ | After I pass, my name remains |

| Dostlar beni hatırlasın | dostlaɾ beni hatɯɾlasɯn | May the friends remember me |

| Düğün olur bayram gelir | dy:ʰyn oluɾ bajɾam geliɾ | Weddings happen, holidays come |

| Dostlar beni hatırlasın | dostlaɾ beni hatɯɾlasɯn | May the friends remember me |

| Can kafeste durmaz uçar | dʒan kafeste duɾmaz utʃaɾ | Soul flies from the cage |

| Dünya bir han konan göçer | dynja biɾ han konan gœtʃeɾ | World is an inn, settlers depart |

| Ay dolanır yıllar geçer | aj dolanɯɾ jɯllaɾ getʃeɾ | The moon wanders, years go by |

| Dostlar beni hatırlasın | dostlaɾ beni hatɯɾlasɯn | May the friends remember me |

| Can bedenden ayrılacak | dʒan bedenden ajɾɯladʒak | Body will be deprived of life |

| Tütmez baca yanmaz ocak | tytmez badʒa janmaz odʒak | Hearth won't burn, smoke won't rise |

| Selam olsun kucak kucak | selam olsun kʋdʒak kʋdʒak | By armfuls, salutes I pass |

| Dostlar beni hatırlasın | dostlaɾ beni hatɯɾlasɯn | May the friends remember me |

| Açar solar türlü çiçek | atʃaɾ solaɾ tyɾly tʃitʃek | Many blooms thrive and fade |

| Kimler gülmüş kim gülecek | kimleɾ gylmyʃ kim gyledʒek | Who had laughed, who'll be glad |

| Murat yalan ölüm gerçek | muɾat jalan œlym geɾtʃek | Desire's lie, real is death |

| Dostlar beni hatırlasın | dostlaɾ beni hatɯɾlasɯn | May the friends remember me |

| Gün ikindi akşam olur | gyn ikindi akʃam oluɾ | Into evening will turn the days |

| Gör ki başa neler gelir | gœɾ ki baʃa neleɾ geliɾ | Behold what soon will take place |

| Veysel gider adı kalır | vejsel gideɾ adɯ kalɯɾ | Veysel departs, his name remains |

| Dostlar beni hatırlasın | dostlaɾ beni hatɯɾlasɯn | May the friends remember me |

References

Specific

- ^ a b c d Gordon, Raymond G., Jr. (ed.) (2005). "Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Fifteenth edition. Report for language code:tur (Turkish)" (HTML). Retrieved 2007-03-18.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Republic of Turkey Ministry of Culture and Tourism (2005). "Turkish Language" (HTML). Retrieved 2007-03-18.

{{cite web}}: External link in|author= - ^ a b Gordon, Raymond G., Jr. (ed.) (2005). "Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Fifteenth edition. Language Family Trees - Altaic" (HTML). Retrieved 2007-03-18.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Center for Studies on Turkey, University of Essen (2003). "The European Turks: Gross Domestic Product, Working Population, Entrepreneurs and Household Data" (PDF). Turkish Industrialists' and Businessmen's Association. Retrieved 2007-01-06.

{{cite web}}: External link in|author= - ^ Gordon, Raymond G., Jr. (ed.) (2005). "Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Fifteenth edition. Report for language code:kmr (Kurdish)" (HTML). Retrieved 2007-03-18.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Turkish Language Association. "Türk Dil Kurumu - Tarihçe (History of the Turkish Language Association)" (HTML). Retrieved 2007-03-18.

- ^ Johanson, Lars (2001). "Discoveries on the Turkic linguistic map" (PDF). Swedish Research Institute in Istanbul. Retrieved 2007-03-18.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Özsoy, A. Sumru & Taylan, Eser E. (eds.) (2000). "Türkçenin ağızları çalıştayı bildirileri (Workshop on the dialects of Turkish)". Boğaziçi University.

{{cite journal}}:|author=has generic name (help); C1 control character in|title=at position 7 (help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Akalın, Şükrü Haluk (2003). "Türk Dil Kurumu'nun 2002 yılı çalışmaları (Turkish Language Association progress report for 2002)" (PDF). Türk Dili. 85 (613). Retrieved 2007-03-18.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Brendemoen, B. (1996), "Phonological Aspects of Greek-Turkish Language Contact in Trabzon", Conference on Turkish in Contact, Netherlands Institute for Advanced Study (NIAS) in the Humanities and Social Sciences, Wassenaar, 5-6 February, 1996

- ^ "Güncel Türkçe Sözlük" (HTML) (in Turkish). Turkish Language Association. 2005. Retrieved 2007-03-21.

- ^ "Türkçe Sözlük (2005)'teki Sözlerin Kökenlerine Ait Sayısal Döküm (Numerical list on the origin of words in Türkçe Sözlük (2005))" (HTML) (in Turkish). Turkish Language Association. 2005. Retrieved 2007-03-21.

- ^ Ishjatms, N. (1996), "Nomads In Eastern Central Asia", History of civilizations of Central Asia, vol. 2, UNESCO Publishing, ISBN 92-3-102846-4

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Findley, Carter V. (2004). The Turks in World History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-517726-6.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Soucek, Svat (2000). A History of Inner Asia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521651691.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Dilaçar, Agop (1977). "Atatürk ve Yazım" (HTML). Türk Dili. 35 (307). Retrieved 2007-03-19.

General

- Püsküllüoğlu, Ali (2004). Arkadaş Türkçe Sözlük (Arkadaş Turkish Dictionary). Arkadaş Yayınevi, Ankara. ISBN 975-509-053-3.

- Lewis, Geoffrey (2002). The Turkish Language Reform: A Catastrophic Success. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-925669-1.

- Lewis, Geoffrey (2001). Turkish Grammar. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-870036-9.

- Eyüboğlu, İsmet Zeki (1991). Türk Dilinin Etimoloji Sözlüğü (Etymological Dictionary of the Turkish Language). Sosyal Yayınları, İstanbul. ISBN 975-7384-72-2.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: checksum (help) - Sevgi Özel, Haldun Özel, and Ali Püsküllüoğlu, (eds.) (1986). Atatürk'ün Türk Dil Kurumu ve Sonrası (Atatürk's Turkish Language Association and After). Bilgi Yayınevi, Ankara.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

See also

- Turkish alphabet

- Turkish literature

- Turkish folk literature

- List of replaced loanwords in Turkish

- List of English words of Turkic origin

- Turkish Sign Language

- Sun Language Theory

External links

Linguistics

- Ethnologue: Languages of the World (unknown ed.). SIL International.[This citation is dated, and should be substituted with a specific edition of Ethnologue]

- Turkish language at the Rosetta Project archive

- Turkish language at Language Museum

Language regulator

Online dictionaries

Courses

- Turkish language courses free for EU citizens

- Ankara University Turkish language courses

- Turkish lessons at the University of Arizona

- Turkish Language Class free online Turkish course

- United States Foreign Service Institute free online Turkish Basic Course

Media