Melbourne

| Melbourne Victoria | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

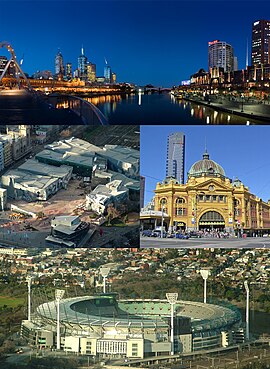

Top: City of Melbourne skyline and Southbank, Middle left: Federation Square, Middle right: Flinders Street Station, Bottom: Melbourne Cricket Ground. | |||||||||

| Coordinates | 37°48′49″S 144°57′47″E / 37.81361°S 144.96306°E | ||||||||

| Population | 3,806,092[1] (2nd) | ||||||||

| • Density | 1,566/km2 (4,060/sq mi) (2006)[2] | ||||||||

| Established | 30 August 1835 | ||||||||

| Area | 8,806 km2 (3,400.0 sq mi) | ||||||||

| Time zone | AEST (UTC+10) | ||||||||

| • Summer (DST) | AEDT (UTC+11) | ||||||||

| Location | |||||||||

| LGA(s) | 31 Municipalities across Greater Melbourne | ||||||||

| County | Bourke | ||||||||

| State electorate(s) | 54 electoral districts and regions | ||||||||

| Federal division(s) | 23 Divisions | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Melbourne (Template:Pron-en-au) is the more common name for the geographic region and statistical division of the Greater Melbourne[3] metropolitan area. It is the second most populous city in Australia, with a population of approximately 3.8 million (2007 estimate) and serves as the state capital of Victoria.[1] Melbourne is located on the lower reaches of the Yarra River and on the northern and eastern shorelines of Port Phillip and their hinterland.

A tiny pastoral town established by settlers from Van Diemen's Land around the estuary of the Yarra (47 years after the first European settlement of Australia)[4] was rapidly transformed into a wealthy metropolis by the Victorian gold rush and immigration. By 1865, Melbourne had become Australia's largest and most important city, and one of the largest and richest in the world.[5][6][7]

Many international and national conferences and events have been held in Melbourne, including the 1956 Summer Olympics and the 2006 Commonwealth Games, the 1981 Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting[8] the World Economic Forum in 2000, and the 2006 G20 summit.[9]

The city is a major centre of commerce, education, tourism, the arts and cultural activities, and also industry. It is consistently ranked one of the most liveable cities in the world.[10][11][12] The city is recognised as Australia's 'sporting and cultural capital'[13] and it is home to many of the nation's most significant cultural and sporting events and institutions. It has been recognised as a gamma world city by the Loughborough University group's 1999 inventory.[14] Melbourne is notable for its mix of Victorian and contemporary architecture, its extensive tram network and Victorian parks and gardens, as well as its diverse, multicultural society.[15]

History

Early history and foundation

Before the arrival of European settlers, the area was occupied for an estimated 31,000 to 40,000 years[16] by under 20,000[17] hunter-gatherers from three indigenous regional tribes: the Wurundjeri, Boonwurrung and Wathaurong, for at least 31,000 years.[18] The area was an important meeting place for clans and territories of the Kulin nation alliance as well as a vital source of food and water.[4][19] The first European settlement in Victoria was established in 1803 on Sullivan Bay, near present-day Sorrento, but this settlement was abandoned due to a perceived lack of resources. It would be 30 years before another settlement was attempted.[20]

In May and June 1835, the area that is now central and northern Melbourne was explored by John Batman, a leading member of the Port Phillip Association, who negotiated a transaction for 600,000 acres (2,400 km2; 940 sq mi) of land from eight Wurundjeri elders.[4][19] Batman selected a site on the northern bank of the Yarra River, declaring that "this will be the place for a village", and returned to Launceston in Tasmania (then known as Van Diemen's Land). However, by the time a settlement party from the Association arrived to establish the new village, a separate group led by John Pascoe Fawkner had already arrived aboard the Enterprize and established a settlement at the same location, on 30 August 1835. The two groups ultimately agreed to share the settlement.

Batman's Treaty with the Aborigines was annulled by the New South Wales government (then governing all of eastern mainland Australia), which compensated the Association.[4] Although this meant the settlers were now trespassing on Crown land, the government reluctantly accepted the settlers' fait accompli and allowed the town (known at first by various names, including 'Bearbrass'[4]) to remain.

In 1836, Governor Bourke declared the city the administrative capital of the Port Phillip District of New South Wales, and commissioned the first plan for the Hoddle Grid in 1837.[21] Later that year, the settlement was named Melbourne after the British prime minister William Lamb, 2nd Viscount Melbourne, who resided in the village of Melbourne in Derbyshire. Melbourne was declared a city by letters patent of Queen Victoria, issued on 25 June 1847.[22] The Port Phillip District became a separate colony of Victoria in 1851 with Melbourne as its capital.

Before the arrival of white settlers, the indigenous population in the district was estimated at 15,000, but following settlement the number had fallen to less than 800,[23] and continued to decline with an estimated 80% decrease by 1863, due primarily to introduced diseases, particularly smallpox.[24]

Victorian gold rush

The discovery of gold in Victoria in the 1850s led to the Victorian gold rush, and the rapid growth of the city, which provided most service industries and served as the major port for the region. During the optimistic 1850s and 1860s, the construction of many of Melbourne's institutional buildings began, including Parliament House, the Treasury Buildings, the State Library, Supreme Court, University, General Post Office, and Government House, as well as St Paul's and St Patrick's cathedrals. The city's inner suburbs were planned, to be linked by boulevards and gardens. Melbourne had become a major finance centre, home to several banks and to Australia's first stock exchange in 1861.[25]

The Land Boom and Bust

By the 1880s, Melbourne's boom was peaking. The city had become the second largest in the British Empire (after London)[26], and the richest in the world.[27] During this prosperous decade, Melbourne hosted five international exhibitions in the large purpose-built Exhibition Building. Melbourne served as the seat of the federal government from the time of the new nation's federation in 1901.[28] Federal government was gradually migrated to Canberra and Melbourne's size and importance was overtaken by Sydney early in the 20th Century.

During an 1885 visit, English journalist George Augustus Henry Sala coined the phrase "Marvellous Melbourne", which stuck long into the twentieth century. Growing building activity culminated in the "Land Boom" which in 1888 reached a peak of speculative development fuelled by optimism and escalating property prices. As a result of the boom, high-rise offices, commercial buildings, coffee palaces, terrace housing and palatial mansions proliferated in the city.[29] Subsequent development (assisted by council fire regulations) has seen most of the taller CBD buildings and larger mansions from this era demolished, though Victorian architecture still abounds in Melbourne. This period also saw the expansion of a major radial rail-based transport network.[30]

The brash boosterism which typified Melbourne during this time came to a halt in 1891 when the start of a severe depression hit the city's economy, sending the local finance and property industries into chaos[29][31] during which 16 small banks and building societies collapsed and 133 limited companies went into liquidation. The Melbourne financial crisis helped trigger the Australian economic depression of 1890s and the Australian banking crisis of 1893. The effects of the depression on the city were profound, although it did continue to grow slowly during the early twentieth century.[32][33]

Federation of Australia

At the time of Australia's federation on 1 January 1901, Melbourne became the temporary seat of government of the federation. The first federal parliament was convened on 9 May 1901 in the Royal Exhibition Building, where it was located until 1927, when it was moved to Canberra. The governor-general remained at Government House until 1930 and many major national institutions remained in Melbourne well into the twentieth century.[34] While Sydney had overtaken Melbourne in size, Melbourne's transport networks were more extensive. Flinders Street Station was the world's busiest passenger station in 1927 and Melbourne's tram network overtook Sydney's to become the worlds largest in the 1940s. During World War II, Melbourne industries thrived on wartime production and the city became Australia's leading manufacturing centre.[citation needed]

Post-war period

After the war, Melbourne expanded rapidly, its growth boosted by an influx of immigrants and the prestige of hosting the Olympic Games in 1956. The post-war period saw a major urban renewal of the CBD and St Kilda Road which significantly modernised the city.[35] To counter the trend towards low-density suburban residential growth, the government began a series of controversial "slum reclamation" public housing projects in the inner city which resulted in demolition of many neighbourhoods and a proliferation of high-rise housing-commission towers.[36] In later years, increasing motor traffic led to major freeway development, causing the city to sprawl outwards. Under premier Henry Bolte, road projects including the Eastern Freeway, Monash Freeway, Tullamarine Freeway and the remodelling of St Kilda Junction changed the face of the city.

Australia's financial and mining booms between 1969 and 1970 resulted in establishment of the headquarters of many major companies (BHP Billiton and Rio Tinto, among others) in the city. Nauru's then booming economy fuelled several ambitious investments in Melbourne, such as Nauru House. Melbourne remained Australia's business and financial capital until the late 1970s, when it began to lose this primacy to Sydney.[37]

As the centre of Australia's "rust belt", Melbourne experienced the worst of Victoria's economic slump between 1989 to 1992, following the collapse of several of its financial institutions. In 1992 the newly elected Kennett Coalition government began a campaign to revive the economy with an aggressive development campaign of public works centred on Melbourne and the promotion of the city as a tourist destination with a focus on major events and sports tourism, attracting the Australian Grand Prix to the city. Major projects included the Melbourne Museum, Federation Square, the Melbourne Exhibition and Convention Centre, Crown Casino and CityLink tollway. Other strategies included the privatisation of some of Melbourne's services, including power and public transport, but also a reduction in funding to public services such as health and education.[38]

Contemporary Melbourne

Since 1997, Melbourne has maintained significant population and employment growth. There has been substantial international investment in the city's industries and property market. Major inner-city urban renewal has occurred in areas such as Southbank, Port Melbourne, Melbourne Docklands and, more recently, South Wharf.

Figures from the Australian Bureau of Statistics showed that Melbourne sustained the highest population increase and economic growth rate of any Australian capital city in the three years ended June 2004.[39]

Geography

Topography

Melbourne is located in the south-eastern part of mainland Australia, within the state of Victoria.[40][41] Geologically, it is built on the confluence of Quaternary lava flows to the west, Silurian mudstones to the east,[42] and Holocene sand accumulation to the southeast along Port Phillip.

Melbourne extends along the Yarra through the Yarra Valley[43] toward the Dandenong Ranges and Yarra Ranges to the east. It extends northward through the undulating bushland valleys of the Yarra's tributaries - Moonee Ponds Creek (toward Tullamarine Airport), Merri Creek and Plenty River to the outer suburban growth corridors of Craigieburn and Whittlesea. The city sprawls south-east through Dandenong to the growth corridor of Pakenham towards West Gippsland, and southward through the Dandenong Creek valley, the Mornington Peninsula and the city of Frankston taking in the peaks of Olivers Hill, Mount Martha and Arthurs Seat, extending along the shores of Port Phillip[44][45] as a single conurbation to reach the exclusive suburb of Portsea and Point Nepean. In the west, it extends along the Maribyrnong River and its tributaries north towards the foothills of the Macedon Ranges, and along the flat volcanic plain country towards Melton in the west, Werribee at the foothills of the You Yangs volcanic peaks and Geelong as part of the greater metropolitan area to the south-west.

Melbourne's major bayside beaches are located in the south-eastern suburbs along the shores of Port Phillip Bay, in areas like Port Melbourne, Albert Park, St Kilda, Elwood, Brighton, Sandringham, Mentone and Frankston although there are beaches in the western suburbs of Altona and Williamstown. The nearest surf beaches are located 85 kilometres (53 mi) south-east of the Melbourne CBD in the back-beaches of Rye, Sorrento and Portsea.[46][47]

Climate

Melbourne has a moderate oceanic climate (Köppen climate classification Cfb).[48] and is well known for its changeable weather conditions. This is due in part to the city's flat topography, its situation on Port Phillip, and the presence of the Dandenong Ranges to the east, a combination that creates weather systems that often circle the bay.[49] The phrase "four seasons in one day" is part of popular culture and observed by many visitors to the city.[50]

| Melbourne | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Melbourne is colder than other mainland Australian state capital cities in the winter. The lowest maximum on record is 4.4 °C (39.9 °F), on 4 July 1901.[52] However, snowfalls are extremely rare: the most recent occurrence of sleet in the CBD was on 25 July 1986 and the most recent snowfalls in the outer eastern suburbs and Mount Dandenong were on 10 August 2005,[53] 15 November 2006, 25 December 2006[54] and 10 August 2008.[55] More commonly, Melbourne experiences frosts and fog in winter.

During the spring, Melbourne commonly enjoys extended periods of mild weather and clear skies. On average, Melbourne is not as hot as more northern cities such as Sydney or Brisbane in summer, but occasionally experiences hotter and drier summer days, with maximum temperatures above 40 °C (104 °F) when northerly winds blow dry air from the arid Mallee region.[56]

In recorded history, Melbourne has experienced a number of highly unusual weather events and extremes of weather as well as the rare natural disaster.[57] In 1891, the great flood caused the Yarra to swell to 305 metres (1,001 ft) in width. In 1897, a great fire destroyed an entire city block between Flinders Street and Flinders Lane, Swanston Street and Elizabeth Street as well as gutting a 43-metre (141 ft) office building which was the city's tallest building of the time. In 1908, a heatwave struck Melbourne. On 2 February 1918, the Brighton tornado, an F3 class and the most intense tornado to hit a major Australian city struck the bayside suburb of Brighton. In 1934, storms caused widespread damage. On 13 January 1939 Melbourne had its second hottest temperature on record, 45.6 °C (114.1 °F), during a four-day nationwide heat wave[58] in which the Black Friday bushfires destroyed townships that are now Melbourne suburbs. In 1951 it snowed in both the CBD and suburbs with moderate cover recorded.[52] In February 1972, the CBD was flooded as the natural watercourse of Elizabeth Street became a raging torrent.[59] On 8 February 1983, the city was enveloped by a massive dust storm, which turned day to night. On 16 February in 1983, Melbourne was encircled by an arc of fire as the Ash Wednesday fires encroached on the city. In 1997, Melbourne was hit by a heatwave with a minimum temperature of 28.8 °C (83.8 °F) over a 24-hour period. Freak storms struck in December 2003, January 2004 and February 2005. On 9 December 2006 some of the thickest bushfire smoke in recorded history blanketed the city sky.[60] A heatwave struck in 2008 and bushfires threatened the suburbs.[49][61] 2008 was Melbourne's 12th consecutive year of below-average rainfall.[62] A heatwave struck in January 2009 which resulted in a record three successive days over 43 degrees celsius.[63] This was closely followed by Melbourne's hottest day on record on 7 February, when the temperature reached 46.4 °C (115.5 °F) in the CBD[64], triggering the 2009 Victorian bushfires, the worst in Australian history.

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Yearly | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean number of rain days | 8.3 | 7.4 | 9.3 | 11.5 | 14.0 | 14.2 | 15.1 | 15.6 | 14.8 | 14.3 | 11.8 | 10.5 | 146.7 | |

| Mean number of clear days | 6.3 | 6.3 | 5.7 | 4.4 | 3.0 | 2.5 | 2.7 | 2.9 | 3.4 | 3.6 | 3.5 | 4.4 | 48.5 | |

| Mean number of cloudy days | 11.2 | 9.7 | 13.4 | 14.9 | 18.0 | 16.8 | 17.2 | 16.8 | 15.7 | 16.4 | 15.1 | 14.2 | 179.5 | |

| Source: Bureau of Meteorology | ||||||||||||||

Environmental sustainability

Like many urban environments, Melbourne faces some significant environmental issues. One such issue is water usage, drought and low rainfall. Drought in Victoria, low rainfalls and high temperatures deplete Melbourne water supplies and climate change will have a long-term impact on the water supplies of Melbourne.[65]Melbourne is in its tenth consecutive year of drought.[66] In response to low water supply's and low rainfall due to drought, the government implemented water restrictions and a range of other options including: water recycling schemes for the city, incentives for household water tanks, greywater systems, water consumption awareness initiatives, and other water saving and reuse initiatives; also, in June 2007, the Bracks Government announced that a $3.1 billion Wonthaggi desalination plant would be built on Victoria's south-east coast, capable of treating 150 billion litres of water per year,[67] as well as a 70 km (43 mi) pipeline from the Goulburn area in Victoria's north to Melbourne and a new water pipeline linking Melbourne and Geelong.[68]

The City of Melbourne, in 2002, set a target to reduce carbon emissions to net zero by 2020.[69] Melbourne has one of the highest urban footprints in the world due to its low density housing, suburban sprawl, and car dependence due to minimal public transport outside of the inner city.[70] Much of the vegetation within the city are non-native species, most of European origin, and in many cases plays host to invasive species and noxious weeds.[71] Significant introduced urban pests include the Common Myna,[72] Feral Pigeon,[73] Common Starling, Brown Rat, European Wasp,[74] and Red Fox.[75] Many outlying suburbs, particularly those in the Yarra Valley and the hills to the north-east and east, have gone for extended periods without regenerative fires leading to a lack of saplings and undergrowth in urbanised native bushland, the Department of Sustainability and Environment partially addresses this problem by regularly burning off.[76][77] Several national parks have been designated around the urban area of Melbourne, including the Mornington Peninsula National Park, Port Phillip Heads Marine National Park and Point Nepean National Park in the south east, Organ Pipes National Park to the north and Dandenong Ranges National Park to the east. There are also a number of significant state parks just outside Melbourne.[78][79]

Responsibility for regulating pollution falls under the jurisdiction of the EPA Victoria and several local councils. Air pollution, by world standards, is classified as being good, however summer and autumn are the worst times of year for atmospheric haze in the urban area.[80][81]

Another current environmental issue in Melbourne is the Victorian government project of channel deepening Melbourne Ports by dredging Port Phillip Bay - the Port Phillip Channel Deepening Project. It is subject to controversy and strict regulations among fears that beaches and marine wildlife could be affected by the disturbance of heavy metals and other industrial sediments.[47][82] Other major pollution problems in Melbourne include levels of bacteria including E-coli in the Yarra River and its tributaries caused by septic systems,[83] as well as up to 350,000 cigarette butts entering the storm water runoff every day.[84] Several programs are being implemented to minimise beach and river pollution.[47][85]

Urban structure

The original city (known today as the central business district or CBD) is laid out in the Hoddle Grid (dimensions of 1 by 0.5 miles (1.61 by 0.80 km)), its southern edge fronting onto the Yarra. The city centre is well known for its historic and attractive lanes and arcades (the most notable of which are Block Place and Royal Arcade) which contain a variety of shops and cafes.[86] The Melbourne CBD, compared with other Australian cities has comparatively unrestrictive height limits and as the result of waves of post war development contains five of the six tallest buildings in Australia, the tallest of these being the Eureka Tower.[87] Prior to the Eureka tower, the Rialto tower was the tallest building in the CBD, which still has an observation deck which is open for the visitors. The CBD and surrounds also contain many significant historic buildings such as the Royal Exhibition Building, the Melbourne Town Hall and Parliament House.[88][89] Although the area is described as the centre, it is not actually the demographic centre of Melbourne at all, due to an urban sprawl to the south east, the demographic centre being located at Bourne St, Glen Iris.[90]

Melbourne is typical of Australian capital cities in that after the turn of the 20th century, it expanded with the underlying notion of a 'quarter acre home and garden' for every family, often referred to locally as the Australian Dream. Much of metropolitan Melbourne is accordingly characterised by low density sprawl. The provision of an extensive passenger railway and tram service in the earlier years of development encouraged this low density development, mostly in radial lines along the transport corridors.

Melbourne is often referred to as Australia's garden city, and the state of Victoria was once known as the garden state.[81][91][92] There is an abundance of parks and gardens in Melbourne,[93] many close to the CBD with a variety of common and rare plant species amid landscaped vistas, pedestrian pathways and tree-lined avenues. There are also many parks in the surrounding suburbs of Melbourne, such as in the municipalities of Stonnington, Boroondara and Port Phillip, south east of the CBD.

The extensive area covered by urban Melbourne is formally divided into hundreds of suburbs (for addressing and postal purposes), and administered as local government areas.[94]

Culture

Melbourne is widely regarded as the cultural and sport capital of Australia.[95][96] It has thrice shared top position[97] in a survey by The Economist of the World's Most Livable Cities on the basis of its cultural attributes, climate, cost of living, and social conditions such as crime rates and health care, in 2002,[98] 2004 and 2005.[99] In recent years rising property prices have led to Melbourne being named the 36th least affordable city in the world and the second least affordable in Australia.[100]

The city celebrates a wide variety of annual cultural events, performing arts and architecture. Melbourne is also considered to be Australia's live music capital with a large proportion of successful Australian artists emerging from the Melbourne live music scene. Street Art in Melbourne is becoming increasingly popular with the Lonely Planet guides listing it as a major attraction. The city is also admired as one of the great cities of the Victorian Age (1837-1901) and a vigorous city life intersects with an impressive range of nineteenth- and early twentieth-century buildings.[101]

Sport

Melbourne is a notable sporting location as the host city for the 1956 Summer Olympics games, the first Olympic Games ever held in Australia[102] along with the 2006 Commonwealth Games.[103][104]

In recent years, the city has claimed the SportsBusiness title "World's Ultimate Sports City".[105] The city is home to the National Sports Museum, which until 2006 was located outside the members pavilion at the Melbourne Cricket Ground and reopened in 2008 in the Great Northern Stand.[106]

Australian rules football and cricket are the most popular sports in Melbourne and also the spiritual home of these two sports in Australia and both are mostly played in the same stadia in the city and its suburbs. The first ever official cricket Test match was played at the Melbourne Cricket Ground in March 1877 and the Melbourne Cricket Ground is the largest cricket ground in the world. The first Australian rules football matches were played in Melbourne in 1859 and the Australian Football League is headquartered at the Telstra Dome. Nine of its teams are based in the Melbourne metropolitan area and the five Melbourne AFL matches per week attract an average 40,000 people per game.[107] Additionally, the city annually hosts the AFL Grand Final.

The city is also home to several professional franchises in national competitions including the Melbourne Storm (rugby league),[108] who play in the NRL competition, Melbourne Victory (Association football (soccer)) who play in the A-league, netball team Melbourne Vixens who play in the trans-Tasman trophy ANZ Championship and basketball teams Melbourne Tigers and South Dragons who play in the National Basketball League.

Melbourne is home to the three major annual international sporting events in the Australian Open (tennis),[109] Melbourne Cup (horse racing),[110] and the Australian Grand Prix (Formula 1).[111]

Cuisine

Within the metropolitan area there are more than 3,000 restaurants.[citation needed] Several restaurants have won prestigious awards. Due to such a diverse population, cuisines from all over the world are available. The bulk of the cafes, eateries, and restaurants in Melbourne are located in the inner city districts, south east Melbourne and the bayside area: Southbank, CDB, Carlton, Docklands, Fitzroy, Brunswick, Port Melbourne, Toorak, Prahran, Malvern, Richmond, South Yarra, Albert Park, and St Kilda.

Festivals

- Melbourne International Comedy Festival

- Melbourne International Film Festival

- Melbourne Food and Wine Festival

- Melbourne Fringe Festival

- Melbourne International Arts Festival

- Melbourne International Flower and Garden Show

- Melbourne Jazz Festival

- Melbourne Spring Racing Carnival (and Melbourne Cup)

- Moomba

- Melbourne International Animation Festival

Cultural institutions

There are more than 100 galleries in Melbourne.[112]

- NGV International

- Ian Potter Centre

- Ian Potter Museum of Art

- Australian Centre for Contemporary Art

- Heide Museum of Modern Art

- Flinders Lane Gallery

- Gertrude Contemporary Art Spaces

- Centre for Contemporary Photography

- The Arts Centre - Hamer Hall, State Theatre and Sidney Myer Music Bowl

- Melbourne Recital Centre

- State Library of Victoria

- Princess Theatre, Melbourne

- Scienceworks Museum

- Melbourne Convention and Exhibition Centre

- Australian Centre for the Moving Image

- Melbourne Museum

- Immigration Museum, Melbourne

- Her Majesty's Theatre

- Melbourne Aquarium

- Regent Theatre, Melbourne

- Malthouse Theatre

- Forum Theatre

- Centre for Education and Research in Environmental Strategies

- National Theatre, Melbourne

Economy

Melbourne is home to Australia's busiest seaport and much of Australia's automotive industry, which include Ford and Toyota manufacturing facilities, and the engine manufacturing facility of Holden. It is home to many other manufacturing industries, along with being a major business and financial centre.[113] International freight is an important industry. The city's port, Australia's largest, handles more than $75 billion in trade every year and 39% of the nation's container trade.[92][114][115] Melbourne Airport provides an entry point for national and international visitors.

Melbourne is also a major technology hub, with an ICT industry that employs over 60,000 people (one third of Australia's ICT workforce), has a turnover of $19.8 billion and export revenues of $615 million. Melbourne retains a significant presence of being a financial centre for Asia-Pacific. Two of the big four banks, NAB and ANZ, are headquartered in Melbourne. The city has carved out a niche as Australia’s leading centre for superannuation (pension) funds, with 40% of the total, and 65% of industry super-funds. Melbourne is also home to the $40 billion-dollar Federal Government Future Fund, and could potentially be home to the world's largest company should the proposed merger between BHP Billiton and Rio Tinto Group be carried out.[116] Tourism also plays an important role in Melbourne's economy, with approximately 7.6 million domestic visitors and 1.88 million international visitors in 2004.[117] In 2008, Melbourne overtook Sydney with the amount of money that domestic tourists spent in the city.[118]

The city is headquarters for many of Australia's largest corporations, including five of the ten largest in the country (based on revenue)[119] (ANZ, BHP Billiton, the National Australia Bank, Rio Tinto and Telstra); as well as such representative bodies and thinktanks as the Business Council of Australia and the Australian Council of Trade Unions. Melbourne rated 34th within the top 50 financial cities as surveyed by the Mastercard Worldwide Centers of Commerce Index (2007),[120] between Barcelona and Geneva, and second only to Sydney (14th) in Australia. Most recent major infrastructure projects, such as the redevelopment of Southern Cross Station (formerly Spencer Street Station),[121] have been centred around the 2006 Commonwealth Games, which were held in the city from 15 March to 26 March 2006. The centrepiece of the Commonwealth Games projects was the redevelopment of the Melbourne Cricket Ground, the stadium used for the opening and closing ceremonies of the Games. The project involved rebuilding the northern half of the stadium and laying a temporary athletics track at a cost of $434 million.[122] Melbourne has also been attracting an increasing share of domestic and international conference markets. Construction began in February 2006 of a $1 billion 5000-seat international convention centre, Hilton Hotel and commercial precinct adjacent to the Melbourne Exhibition and Convention Centre to link development along the Yarra River with the Southbank precinct and multi-billion dollar Docklands redevelopment.[123]

Demographics

| Significant overseas born populations[124] | |

| Place of Birth | Population (2006) |

|---|---|

| United Kingdom | 156,457 |

| Italy | 73,801 |

| Vietnam | 57,926 |

| People's Republic of China | 54,726 |

| New Zealand | 52,453 |

| Greece | 52,279 |

| India | 50,686 |

| Sri Lanka | 30,594 |

| Malaysia | 29,174 |

| Croatia | 24,568 |

| Germany | 21,182 |

| Malta | 18,951 |

| South Africa | 17,317 |

| Rep. Macedonia | 17,287 |

| Hong Kong | 16,917 |

| Poland | 16,439 |

| Philippines | 15,367 |

| Lebanon | 14,645 |

| Netherlands | 14,581 |

| Turkey | 14,124 |

| Melbourne population by year | ||

|---|---|---|

| 1836 | 177 | |

| 1854 | 123,000 | (gold rush) |

| 1880 | 280,000 | (property boom) |

| 1956 | 1,500,000 | |

| 1981 | 2,806,000 | |

| 1991 | 3,156,700 | (economic slump) |

| 2001 | 3,366,542 | |

| 2006 | 3,744,373 | |

Melbourne is a diverse and multicultural city and melting pot.[125] This is reflected by the fact that the city is home to restaurants serving over 70 national cuisines.

Almost a quarter of Victoria's population was born overseas, and the city is home to residents from 233 countries, who speak over 180 languages and dialects and follow 116 religious faiths. Melbourne has the second largest Asian population in Australia, which includes the largest Vietnamese, Indian and Sri Lankan communities in the country.[126][127][128]

The first European settlers in Melbourne were British and Irish. These two groups accounted for nearly all arrivals before the gold rush, and supplied the predominant number of immigrants to the city until the Second World War. Melbourne was transformed by the 1850s gold rush; within months of the discovery of gold in August 1852, the city's population had increased by nearly three-quarters, from 25,000 to 40,000 inhabitants.[129] Thereafter, growth was exponential and by 1865, Melbourne had overtaken Sydney as Australia's most populous city.[130] Large numbers of Chinese, German and United States nationals were to be found on the goldfields and subsequently in Melbourne. The various nationalities involved in the Eureka Stockade revolt nearby give some indication of the migration flows in the second half of the nineteenth century.[131]

In the aftermath of the Second World War, Melbourne experienced unprecedented inflows from southern Europe, primarily Greece, Italy and Cyprus and West Asia mostly from Turkey, and Lebanon. According to the 2001 Census, there were 151,785 ethnic Greeks in the metropolitan area.[132] 47% of all Greek Australians live in Melbourne.[133] Ethnic Chinese and Vietnamese also maintain significant presences.

Melbourne exceeds the national average in terms of proportion of residents born overseas: 34.8% compared to a national average of 23.1%. In concordance with national data, Britain is the most commonly reported overseas country of birth, with 4.7 %, followed by Italy (2.4%), Greece (1.9 %) and then China (1.3 %). Melbourne also features substantial Vietnamese, Indian and Sri Lankan-born communities, in addition to recent South African and Sudanese influxes.

Over two-thirds of people in Melbourne speak only English at home (68.8 %). Italian is the second most common home language (4.0 %), with Greek third and Chinese fourth, each with over 100,000 speakers.[134]

Melbourne is also home to a wide range of religious faiths. The largest of which is Christian (64%) with a large Catholic population (28.3%).[135] However Melbourne and indeed Australia are highly secularised, with the proportion of people identifying themselves as Christian declining from 96% in 1901 to 64% in 2006 and those who did not state their religion or declared no religion rising from 2% to over 30% over the same period.[136] Nevertheless, the large Christian population is signified by the city's two large cathedrals - St Patrick's (Roman Catholic),[137] and St Paul's (Anglican).[138] Both were built in the Victorian era and are of considerable heritage significance as major landmarks of the city.[139]

The next highest response was No Religion (20.0%, 717,717), Anglican (12.1%, 433,546), Eastern Orthodox (5.9%, 212,887) and the Uniting Church (4.0%, 143,552).[135] Buddhists, Muslims, Jews and Hindus collectively account for 7.5% of the population.

The Jewish population in Melbourne is significant as four out of ten Australian Jews call Melbourne home. The city is also residence to the largest number of Holocaust survivors of any Australian city,[140] indeed the highest per capita concentration outside Israel itself.[141] To service the needs of the vibrant Jewish community, Melbourne's Jewry have established multiple synagogues, which today number over 30,[142] along with a local Jewish newspaper.[143] Melbourne's largest university - Monash University is named after prominent Jewish general and statesman, John Monash.[144]

Although Victoria's net interstate migration has fluctuated, the Melbourne statistical division has grown by approximately 50,000 people a year since 2003. Melbourne has now attracted the largest proportion of international overseas immigrants (48,000) finding it outpacing Sydney's international migrant intake, along with having strong interstate migration from Sydney and other capitals due to more affordable housing and cost of living, which have been two recent key factors driving Melbourne's growth.[145] In recent years, Melton, Wyndham and Casey, part of the Melbourne statistical division, have recorded the highest growth rate of all local government areas in Australia. Despite a demographic study stating that Melbourne could overtake Sydney in population by 2028,[146] the ABS has projected in two scenarios that Sydney will remain larger than Melbourne beyond 2056, albeit by a margin of less than 3% compared to a margin of 12% today. However, the first scenario projects that Melbourne's population overtakes Sydney in 2039, primarily due to larger levels of internal migration losses assumed for Sydney.[147]

After a trend of declining population density since Second World War, the city has seen increased density in the inner and western suburbs aided in part by Victorian Government planning blueprints, such as Postcode 3000 and Melbourne 2030 which have aimed to curtail the urban sprawl.[148] [149]

Media

Melbourne is served by three daily newspapers, the Herald Sun (a tabloid),[150] The Age (broadsheet)[151] and The Australian (national broadsheet).[152] The free mX is also distributed every weekday afternoon at railway stations and on the streets of central Melbourne.[153]

Melbourne is served by six television stations: HSV-7, which broadcasts from the Melbourne Docklands precinct; GTV-9, which broadcasts from their Richmond studios; and ATV-10, which broadcasts from the Como Complex in South Yarra. National stations that broadcast into Melbourne include the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC), which has two studios, one at Ripponlea and another at Southbank; and Special Broadcasting Service (SBS), which broadcasts from their studios at Federation Square in central Melbourne. C31 Melbourne is the only local community television station in Melbourne, and its broadcast range also branches out to Geelong. Melbourne also receives Pay TV, largely through cable services. Foxtel and Optus are the main Pay TV providers.

A number of radio stations service the areas of Melbourne and beyond on the AM and FM band. Popular stations on the FM band include DMG Radio channels Nova 100 and Vega 91.5 as well as Australian Radio Network's Gold 104.3 and Mix 101.1, both in Richmond, and Austereo channels Fox FM and Triple M, which share studios in South Melbourne and Triple J. Stations that are popular on the AM band include 774 ABC Melbourne, 3AW, a prominently talkback radio station, and its affiliate, Magic 1278, which plays a selection of music from the 1930s-60s. Community radio is also strong in Melbourne, with a number of community and subscription based radio stations on both the AM and FM bands. The best known of these stations are Triple R, SynFM, 3JOY, PBS & 3CR. There are also a number of community stations based around the greater Melbourne area.[154]

Governance

The Melbourne City Council governs the City of Melbourne, which takes in the CBD and a few adjoining inner suburbs. However the head of the Melbourne City Council, the Lord Mayor of Melbourne, is frequently treated as a representative of greater Melbourne (the entire metropolitan area),[155] particularly when interstate or overseas. Robert Doyle, elected in 2008, is current Lord Mayor. The rest of the metropolitan area is divided into 31 local government areas. All these are designated as Cities, except for five on the city's outer fringes which have the title of Shire. The local government authorities have elected councils and are responsible for a range of functions (delegated to them from the State Government of Victoria under the Local Government Act of 1989[156]), such as urban planning and waste management.

Most city-wide government activities are controlled by the Victorian state government, which governs from Parliament House in Spring Street. These include public transport, main roads, traffic control, policing, education above preschool level, and planning of major infrastructure projects. Because three quarters of Victoria's population lives in Melbourne, state governments have traditionally been reluctant to allow the development of citywide governmental bodies, which would tend to rival the state government. The semi-autonomous Melbourne and Metropolitan Board of Works was abolished in 1992 for this reason.[157] This is not dissimilar to other Australian states where State Governments have similar powers in greater metropolitan areas.

Education

Education is overseen statewide by the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development (DEECD), whose role is to 'provide policy and planning advice for the delivery of education'.[158] It acts as advisor to two state ministers, that for Education and for Children and Early Childhood Development.

Preschool, primary and secondary

Primary and secondary assessment, curriculum development and educational research initiatives throughout Melbourne and Victoria is undertaken by the Victorian Curriculum and Assessment Authority (VCAA),[159] which offers the Victorian Essential Learning Standards (VELS) and Achievement Improvement Monitor (AIM) certificates from years Prep through Year 10, and the Victorian Certificate of Education (VCE) and Victorian Certificate of Applied Learning (VCAL) as part of senior secondary programs (Years 11 to 12).

Many high schools in Australia are called 'Secondary Colleges', a legacy of the Kirner Labor government.[citation needed] There are two selective public schools in Melbourne (mentioned above), but all public schools may restrict entry to students living in their regional 'zone'.[160][161]

Although non-tertiary public education is free, 35% of students attend a private primary or secondary school.[162] The most numerous private schools are Catholic, and the rest are independent (see Public and Private Education in Australia).

Tertiary, vocational and research

Name and year established

- Victorian College of the Arts - now a part of The University of Melbourne.

- Melba Memorial Conservatorium of Music - now considered part of Victoria University.

- Deakin University - two major campuses in Melbourne and Geelong, the third largest university in Victoria.

- Australian Catholic University - St Patrick's campus.

Melbourne's two largest universities are the University of Melbourne and Monash University, the largest university in Australia. Both are members of the Group of Eight. Melbourne University ranked second among Australian universities in the 2006 THES international rankings.[163] While The Times Higher Education Supplement ranked the University of Melbourne as the 22nd best university in the world, Monash University was ranked the 38th best university in the world. Melbourne was ranked the world's fourth top university city in 2008 after London, Boston and Tokyo.[164]

Some of the nation's oldest educational institutions and faculities are located in Melbourne, including the oldest Engineering (1860), Medical (1862), Dental (1897) and Music (1891) schools and the oldest law course in Australia (1857), all at the University of Melbourne. The University of Melbourne is also the oldest university in Victoria and the second oldest university in Australia.

In recent years, the number of international students at Melbourne's universities has risen rapidly, a result of an increasing number of places being made available to full fee paying students.[165]

Infrastructure

Health

The Government of Victoria's Department of Human Services oversees approximately 30 public hospitals in the Melbourne metropolitan region, and 13 health services organisations.[166]

Public

- Royal Melbourne Hospital

- The Alfred Hospital

- Monash Medical Centre

- Austin Hospital

- St Vincent's

- Royal Children's Hospital

Private

- Epworth Hospital

- St Francis Xavier Cabrini Private Hospital

- St Vincent's Private.

There are many major medical, neuroscience and biotechnology research institutions located in Melbourne: St. Vincent's Institute of Medical Research, Australian Stem Cell Centre, the Burnet Institute, Australian Regenerative Medicine Institute, Victorian Institute of Chemical Sciences, Brain Research Institute, Peter MacCallum Cancer Institute, the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research, Melbourne Neuropsychiatry Centre, Howard Florey Institute, the Murdoch Childrens Research Institute, Baker IDI Heart and Diabetes Institute and the Australian Synchrotron.[167] Many of these institutions are associated with and are located near universities.

Transport

Melbourne has an integrated public transport system promoted under the Metlink brand. Originally laid out late in the 19th century when trains and trams were the primary methods of travelling to the suburbs, the 1950s saw an increase in private vehicles and freeway construction.[168] This trend has continued with successive governments despite relentless traffic congestion,[169] with a resulting drop in public transport modeshare from the 1940s level of around 25% to the current level of around 9%[170] Melbourne's public transport system was privatised in 1999.[171] Between 1999 and 2008, funding for road expansion was five times greater than public transport extension.[172] Melbourne's tram network is the largest tram network in the world.[173][174][175] Melbourne's is Australia's only tram network to comprise more than a single line. Sections of the tram network are on road, others are separated or light rail routes. The iconic trams are also recognised as a cultural asset and tourist attraction. Heritage trams operate on the free City Circle route, intended for visitors to Melbourne, and heritage restaurant trams travel through the city during the evening.[176]

The Melbourne rail network consists of 19 suburban lines which radiate from the City Loop, a partially underground metro section of the network beneath the Central Business District (Hoddle Grid). Flinders Street Station is Melbourne's busiest railway station, and was the world's busiest passenger station in 1926. It remains a prominent Melbourne landmark and meeting place.[177] The city has rail connections with regional Victorian cities, as well as interstate rail services to Sydney and Adelaide, which depart from Melbourne's other major rail terminus, Southern Cross Station in Spencer Street. Melbourne's bus network consists of almost 300 routes which mainly service the outer suburbs fill the gaps in the network between rail and light rail services.[176][178] Melbourne has a high dependency on private cars for transport, with 7.1% of trips made by public transport.[179] However there has been a significant rise in patronage in the last two years mostly due to higher fuel prices,[180] since 2006, public transport patronage has grown by over 20%.[181] The largest number of cars are bought in the outer suburban area, while the inner suburbs with greater access to train and tram services enjoy higher public transport patronage. Melbourne has a total of 3.6 million private vehicles using 22,320 km (13,870 mi) of road, and one of the highest lengths of road per capita.[179] Major highways feeding into the city include the Eastern Freeway, Monash Freeway and West Gate Freeway (which spans the large Westgate Bridge), whilst other freeways circumnavigate the city or lead to other major cities, including CityLink, Eastlink, the Western Ring Road, Calder Freeway, Tullamarine Freeway (main airport link) and the Hume Freeway which links Melbourne and Sydney.[182]

The Port of Melbourne is Australia's largest container and general cargo port and also its busiest. In 2007, the port handled two million shipping containers in a 12 month period, making it one of the top five ports in the Southern Hemisphere.[114] Station Pier in Port Phillip Bay handles cruise ships and the Spirit of Tasmania ferries which cross Bass Strait to Tasmania.[183] Melbourne has four airports. Melbourne Airport located at Tullamarine is the city's main international and domestic gateway. The airport is home base for passenger airlines Jetstar and Tiger Airways Australia and cargo airlines Australian air Express and Toll Priority and is a major hub for Qantas and Virgin Blue. Avalon Airport, located between Melbourne and Geelong, is a secondary hub of Jetstar. It is also used as a freight and maintenance facility. This makes Melbourne the only city in Australia to have a second commercial airport. Moorabbin Airport is a significant general aviation airport in the city's south east as well as handling a limited number of passenger flights. Essendon Airport, which was once the city's main airport before the construction of the airport at Tullamarine, handles passenger flights, general aviation and some cargo flights.[184]

Utilities

Gas is provided by private companies, as is electricity, which is sourced mostly from coal-fired power stations.

Water storage and supply for Melbourne is managed by Melbourne Water, which is owned by the Victorian Government. The organisation is also responsible for management of sewerage and the major water catchments in the region and will be responsible for the Wonthaggi desalination plant and the North-South Pipeline. Water is mainly stored in the largest dam, the Thomson River Dam which is capable of holding around 60% of Melbourne's water capacity,[185] while smaller dams such as the Upper Yarra Dam and the Cardinia Reservoir carry secondary supplies.

Numerous telecommunications companies provide Melbourne with terrestrial and mobile telecommunications services and wireless internet services.

International relations

Template:Melb sister cities map The City of Melbourne has six sister cities.[186] They are:

|

Some other local councils in the Melbourne metropolitan area have sister city relationships; see Local Government Areas of Victoria.

Melbourne is a member of the C40: Large Cities Climate Leadership Group and the United Nations Global Compact - Cities Programme.

See also

|

|

Further reading

|

Notes

[a]

The variant spelling 'Melbournian' is sometimes found but is considered grammatically incorrect. The term 'Melbournite' is also sometimes used. See:[187]

[b]

Legislation passed in December 1920 resulted in the formation of the SECV from the Electricity Commission. (State Electricity Commission Act 1920 (No.3104))

References

- ^ a b "Regional Population Growth, Australia, 2006-07". Australian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 2008-03-31.

- ^ Australian Bureau of Statistics (25 October 2007). "Community Profile Series: Melbourne (Urban Centre/Locality)". 2006 Census of Population and Housing. Retrieved 2008-05-19.

- ^ http://www.investvictoria.com/GreaterMelbourne

- ^ a b c d e "City of Melbourne — History and heritage — Settlement – foundation and surveying". City of Melbourne. Retrieved 2006-10-07.

- ^ Dr Robert Lee (2003). "Chapter 6: Transport and the Making of Cities, 1850-1970". Linking a Nation: Australia's transport and communications 1788-1970. Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- ^ Robert B. Cervero, The Transit Metropolis: A Global Inquiry, 1998, Island Press, ISBN 1559635916, p.320

- ^ Statesmen's Year Book 1889

- ^ "Commonwealth Secretariat — List of Meetings". thecommonwealth.org. Retrieved 2008-10-13.

- ^ "Melbourne Prepares for G-20 Summit". ohmynews.com. Retrieved 2008-09-28.

- ^ "Vancouver and Melbourne top city league". BBC News. 4 October 2002. Retrieved 2008-12-127.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Vancouver is 'best place to live'". BBC News. 4 October 2005. Retrieved 2008-12-27.

- ^ "Lagos, worst city to live". Online Nigeria. Retrieved 2009-02-07. (password required)

- ^ "Committee for Melbourne- The Sporting Capital". The Committee for Melbourne. Retrieved 2008-09-28.

- ^ Beaverstock, J.V. "Research Bulletin 5: A Roster of World Cities". Globalization and World Cities.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "The Age 150th". Fairfax Media. Retrieved 2008-09-28.

- ^ Gary Presland, The First Residents of Melbourne's Western Region, (revised edition), Harriland Press, 1997. ISBN 0646331507. Presland says on page 1: "There is some evidence to show that people were living in the Maribyrnong River valley, near present day Keilor, about 40,000 years ago."

- ^ http://www.rbg.vic.gov.au/__data/page/1062/Indig.pdf

- ^ Gary Presland, Aboriginal Melbourne: The Lost Land of the Kulin People, Harriland Press (1985), Second edition 1994, ISBN 0957700423. This book describes in some detail the archeological evidence regarding aboriginal life, culture, food gathering and land management, particularly the period from the flooding of Bass strait and Port Phillip from about 7-10,000 years ago up to the European colonisation in the nineteenth century.

- ^ a b Isabel Ellender and Peter Christiansen, People of the Merri Merri. The Wurundjeri in Colonial Days, Merri Creek Management Committee, 2001 ISBN 0957772807

- ^ Button, James (2003-10-04). "Secrets of a forgotten settlement". The Age. Retrieved 2008-10-19.

- ^ "City of Melbourne — Roads — Introduction". City of Melbourne. Retrieved 2008-09-29.

- ^ Lewis, Miles (1995). 2nd (ed.). Melbourne the city's history and development. p. 220.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: editors list (link)p25 - ^ http://www.ccmaindig.info/culture/Timeline.html

- ^ http://www.rbg.vic.gov.au/__data/page/1062/Indig.pdf

- ^ "Media Business Communication time line since 1861". Caslon. Retrieved 2008-09-29.

- ^ Statesmen's Year Book 1889

- ^ Robert B. Cervero, The Transit Metropolis: A Global Inquiry, 1998, Island Press, ISBN 1559635916, p.320

- ^ University of Melbourne. "When Melbourne was Australia's capital city". University of Melbourne. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- ^ a b The Land Boomers. By Michael Cannon. Melbourne University Press; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1966

- ^ Lewis, Miles (Melbourne the city's history and development) p47

- ^ Lambert, Time. "A BRIEF HISTORY OF MELBOURNE". localhistories.org. Retrieved 2008-09-29.

- ^ "Melbourne (victoria) - growth of the city". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2008-09-29.

- ^ "Fast Facts on Melbourne History". we-love-melbourne.net. Retrieved 2008-09-29.

- ^ Lewis, Miles (Melbourne the city's history and development) p. 113-114

- ^ Judith Raphael Buckrich (1996) Melbourne's Grand Boulevard: the Story of St Kilda Road. Published State Library of Victoria

- ^ William, Logan (1985). The Gentrification of inner Melbourne - a political geography of inner city housing. Brisbane, Queensland: University of Queensland Press. pp. 148–160. ISBN 0-7022-1729-8.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Tell Melbourne it's over, we won". Sydney Morning Herald. Sydney Morning Herald. 31 December 2003. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- ^ Lewis, Miles (Melbourne the city's history and development) p203,205-206

- ^ "Melbourne's population booms". The Age. Fairfax Digital, The Age. 24 March 2005. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- ^ "Melbourne, Victoria, Australia — visitmelbourne.com/". Tourism Victoria. Retrieved 2008-09-28.

- ^ "Melbourne, Victoria, - About Australia". About Australia Online Pty. Ltd. ('about-australia.com'. Retrieved 2008-09-28.

- ^ City of Monash. "Detailed History: 1900-1945". www.monash.vic.gov.au. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- ^ "Yarra River, Melbourne Australia". Yarra River Precinct Association, Yarra Tourism Association. Retrieved 2008-09-28.

- ^ "Port Phillip". Parks Victoria 2008. Retrieved 2008-09-28.

- ^ "Port Phillip Bay — Victoria". austtravel.com.au/ - Austtravel. Retrieved 2008-09-28.

- ^ Russell, Mark (2 January 2006). "Life's a beach in Melbourne". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 2008-09-29.

- ^ a b c "BEACH REPORT 2007–08" (PDF). epa.vic.gov.au. Retrieved 2008-09-29.

- ^ Peel, M. C. (1 March 2007). "Updated world map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification". HESSD - Hydrology and Earth system sciences (4): 439–473.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Melbourne Climate statistics". Australian Government — Bureau of Meteorology. Retrieved 2008-09-29.

- ^ City of Melbourne. "Welcome to Melbourne — Welcome to Melbourne — Introduction". www.melbourne.vic.gov.au. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- ^ "Climate statistics for Australian locations". Retrieved 2007-09-05.

- ^ a b "Snow misses CBD lunch appointment — National — theage.com.au". The Age. 2005-08-10. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|wokr=ignored (help) - ^ Snow falls in Melbourne Sydney Morning Herald, 10 August 2005 accessed online 7 November 2006

- ^ "Santa brings snow to Melbourne". Herald Sun. News Limited. 2006-12-25. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- ^ "Snow in Victoria - 10 August 2005". Bom.gov.au. Retrieved 2008-10-10.

- ^ "Melbourne Weather (climate)". Melbourne travel guide. Retrieved 2008-10-27.

- ^ "Melbourne: City of woes". The Age. The Age. 2003-09-02. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- ^ "Record heat and stupidity as Melbourne swelters". The Age. The Age. 25 January 2003. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- ^ "Melbourne flood — Elizabeth Street, February 1972". Bureau of Meteorology. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- ^ "Smoke triggers alarm in city — National — theage.com.au". The Age. theage.com.au. 9 December 2006. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- ^ "Melbourne sizzles in heatwave". ABC News. www.abc.net.au. 10 January 2008. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- ^ Water plan may not go far enough. Ben Doherty. The Age. October 23, 2008

- ^ Melbourne records three days in a row of 43C for first time. Sarah Wotherspoon. Herald Sun. January 30, 2009

- ^ City Swelters, records tumble in heat Hamish Townsend. The Age. February 7, 2009

- ^ http://www.melbournewater.com.au/content/water/water_storages/water_storages.asp?bhcp=1

- ^ http://www.melbournewater.com.au/content/publications/fact_sheets/water/living_with_drought.asp

- ^ "Desal plant to be public-private deal". The Age. theage.com.au. 20 September 2007. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- ^ Melbourne Water. "Water Supply: Seawater Desalination Plant". www.melbournewater.com.au. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- ^ http://www.melbourne.vic.gov.au/info.cfm?top=218&pa=4025&pa2=1612&pg=1618

- ^ R, Cardew (1998). Urban Footprints and Stormwater Management: A Council Survey p16-25. J George,.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ "Target Species for Biological Control". weeds.org.au. Retrieved 2008-09-29.

- ^ "Scientists declare war on Indian mynah". 7.30 Report. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 2002-07-01:. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Bradbury, Garth (7 September 2004). "UPDATE ON PIGEON MANAGEMENT ISSUE" (PDF). City of Melbourne. Retrieved 2008-10-22.

- ^ "The picnickers nightmare: European wasp". CSIRO. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- ^ Marks, C.A. & Bloomfield, T.E. (1999) Distribution and density estimates for urban foxes (Vulpes vulpes) in Melbourne: implications for rabies control

- ^ "Fire and Biodiversity: The Effects and Effectiveness of Fire Management". Australian government — Department of environment. Retrieved 2008-09-29.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Murray, Robert (1995). State of Fire: A History of Volunteer Firefighting and the Country Fire Authority in Victoria. Hargreen Publishing. pp. 339 pages. ISBN 0949905631.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "About Parks Victoria". parkweb.vic.gov.au. Retrieved 2008-09-29.

- ^ Wild Places of Greater Melbourne. R Taylor, 9780957747104, CSIRO Publishing, January 1999, 224pp, PB

- ^ CSIRO: Marine and atmospheric research. "Urban and regional air pollution". CSIRO. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- ^ a b "Victoria: the garden state or greenhouse capital?". The Age — Fairfax Media. Retrieved 2008-09-29.

- ^ "Garrett approves Port Phillip Bay dredging". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 2008-02-05. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- ^ "E coli running riot in Yarra River". Herald Sun. News Limited. 31 May 2008. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- ^ Australian Institute of Urban Studies and City of Melbourne. "AIUS Indicators". Environmental indicators for Metropolitan Melbourne. Australian Institute of Urban Studies. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- ^ "Victoria's Litter reduction Strategy" (PDF). litter.vic.gov.au. Retrieved 2008-09-29.

- ^ Suzy Freeman-Greene (10 August 2005). "Melbourne's love affair with lanes — Opinion — www.theage.com.au". The Age. theage.com.au. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- ^ "Eureka Tower". Eureka Tower Official. Retrieved 2008-09-29.

- ^ "Walking Melbourne, Heritage, Architecture, Skyscraper and Buildings Database". Walking Melbourne. Retrieved 2008-09-28.

- ^ "Melbourne Architecture". Melbourne Travel Guide. Retrieved 2008-09-28.

- ^ "Glen Iris still the heart of city's sprawl". The Age. www.theage.com.au. 5 August 2002. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- ^ ""Victoria"". wilmap.com.au. Retrieved 2008-09-29.

- ^ a b "Victoria Australia, aka "The Garden State"". goway.com. Retrieved 2008-09-29.

- ^ "City of Melbourne — Parks and Gardens". City of Melbourne. Retrieved 2008-09-28.

- ^ "Vicnet Directory — Local Government". Vicnet. Retrieved 2008-09-29.

- ^ "About Melbourne". Tourism Victoria — visitvictoria.com. Retrieved 2008-09-28.

- ^ "Melbourne is the 'world sports capital'". ioltravel.co.za. 26 June 2008. Retrieved 2008-09-28.

- ^ "Melbourne 'world's top city'". The Age. theage.com.au. 6 February 2004. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- ^ "Melbourne, Vancouver top city list". archives.cnn.com. 4 October 2002. Retrieved 2008-07-18. (Economist Intelligence Unit 2002)

- ^ "City Mayors: Best cities in the world (EIU)". www.citymayors.com. Retrieved 2008-07-18. (Economist Intelligence Unit 2005)

- ^ "Cost of living — The world's most expensive cities". City Mayors.

- ^ Peter Fischer and Susan Marsden, Vintage Melbourne: beautiful buildings from Melbourne city centre, East Street Publications, Bowden South Australia 2007

- ^ "International Olympic Committee - 1956 Olympics". IOC — International Olympic Committee. Retrieved 2008-09-28.

- ^ "M2006 - Home". Melbourne 2006 Commonwealth Games Corporation. Retrieved 2008-09-28.

- ^ "Commonwealth Games Melbourne 2006". www.cultureandrecreation.gov.au. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- ^ "Melbourne victorious again". Herald Sun. www.news.com.au. 1 April 2008. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- ^ Geoff Strong (5 March 2008). "Australian sports museum opens at MCG". The Age. theage.com.au. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- ^ Smith, Patrick (August 1, 2008). "AFL blueprint for third stadium" (in news.com.au). The Australian. Retrieved 2008-10-22.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "Melbourne Storm — The Beginning". www.melbournestorm.com.au. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- ^ "Australian Open Tennis Championships". Tennis Australia. Retrieved 2008-09-29.

- ^ "Melbourne Cup Carnival". The Victoria Racing Club Ltd (VRC). Retrieved 2008-09-29.

- ^ "Formula 1 Australia Gran Prix". The Australian Grand Prix Corporation (AGPC). Retrieved 2008-09-29.

- ^ http://www.visitvictoria.com/displayobject.cfm/objectid.000E578C-41C9-1A7A-92E980C476A90000/

- ^ "Business Victoria - Manufacturing". State of Victoria, Australia. 26 May 2008. Retrieved 2008-10-22.

- ^ a b "Port Of Melbourne Sets Shipping Record". Malaysian National News Agency. www.bernama.com.my. 13 June 2007. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- ^ "Growth of Australia's largest port essential". The Age. theage.com.au. 18 December 2004. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- ^ BHP chief spruiks up bid to take over Rio Tinto, The Age, 13 November 2007

- ^ "MELBOURNE AIRPORT PASSENGER FIGURES STRONGEST ON RECORD". Media Release: MINISTER FOR TOURISM. www.dpc.vic.gov.au. 21 July 2004. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- ^ "Now Sydney loses its tourism ascendancy". The Age. theage.com.au. 19 May 2008. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- ^ BRW 1000

- ^ "MW-IndexRpt-CoComm FA.indd" (PDF). Retrieved 2008-10-10.

- ^ "Southern Cross Station project". doi.vic.gov.au/. Retrieved 2008-09-29.

- ^ "»Melbourne Cricket Ground »Redevelopment". AustralianStadiums.com. Retrieved 2008-09-29.

- ^ Councillors furious about convention centre deal, The Age, 1 May 2006

- ^ "2006 Census Tables : Country of Birth of Person by Year of Arrival in Australia — Melbourne". Australian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 2008-04-16.

- ^ "Melburnians turn to 'Soul Food' for nourishment". Baha'i World News Service, Israel. 28 September 2008. Retrieved 2008-10-02.

- ^ "Vicnet Directory Indian Community". Vicnet. Retrieved 2008-10-02.

- ^ "Vicnet Directory Sri Lankan Community". Vicnet. Retrieved 2008-10-02.

- ^ "Vietnamese Community Directory". yarranet.net.au. Retrieved 2008-10-02.

- ^ Victorian Cultural Collaboration. "Gold!". sbs.com.au. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- ^ The Snowy Mountains Scheme and Multicultural Australia

- ^ Annear, Robyn (1999). Nothing But Gold. The Text Publishing Company.

- ^ L a z z a r o, V i n c e (1 1 : 3 0 A M ( C A N B E R R A T I M E ) T U E S 1 1 F E B 2 0 0 3). "Melbourne 2001 Census" (PDF). 2001 Australian Census. 1 (2030.2). Canbera, ACT, Australia: Australian Beureau of Statistics: 92.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ City of Melbourne. "Multicultural communities — Greeks". www.melbourne.vic.gov.au. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- ^ "Demographic Profiling of Victorian Government Website Visitors 2007". egov.vic.gov.au. Retrieved 2008-10-02.

- ^ a b "QuickStats : Melbourne (Statistical Division)". 2006 Census. www.censusdata.abs.gov.au. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- ^ "Cultural diversity". 1301.0 - Year Book Australia, 2008. Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2008-02-07. Retrieved 2008-07-15.

- ^ "St Patrick's Cathedral". Catholic Communication, Melbourne. Retrieved 2008-10-05.

- ^ "St. Paul's Cathedral, Melbourne". anglican.com.au. Retrieved 2008-10-05.

- ^ "Victorian Architectural Period — Melbourne". walkingmelbourne.com. Retrieved 2008-10-05.

- ^ Freiberg, Freda (2001). "Judith Berman, Holocaust Remembrance in Australian Jewish Communities, 1945-2000". UWA Press. Retrieved 2008-10-22.

- ^ "The Kadimah & Yiddish Melbourne in the 20th Century". Jewish Cultural Centre and National Library: "Kadima".

{{cite web}}: Text "accessdate 9 January" ignored (help) - ^ "Jewish Community of Melbourne, Australia". Beth Hatefutsoth — The Nahum Goldmann Museum of the Jewish Diaspora. Retrieved 2008-10-05.

- ^ "Welcome to the AJN!". The Australian Jewish News. Retrieved 2008-10-05.

- ^ Perry, Roland (2004). Monash: The Outsider who Won A War. Random House.

- ^ O'Leary, John. "Resurgance of Marvellous Melbourne" (PDF). People and Place. 7, 1. Monash University: 38.

- ^ "Population pushing Melbourne to top". The Australian. www.theaustralian.news.com.au. 12 November 2007. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- ^ "Population Projections, Australia, 2006 to 2101". Australian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 2008-09-04.

- ^ "Melbourne 2030 - in summary". Victorian Government, Department of Sustainability and Environment (DSE). Retrieved 2008-10-05.

- ^ "City of Melbourne — Strategic Planning — Postcode 3000". City of Melbourne. Retrieved 2008-10-05.

- ^ "Herald Sun Homepage". Herals Sun — News.com.au. Retrieved 2008-10-02.

{{cite web}}: Text "Victorian, National and International news" ignored (help) - ^ "The Age — Homepage". Fairfax Digital. Retrieved 2008-10-02.

- ^ "The Australian, News from Australia's national newspaper". The Australian — news.com.au. Retrieved 2008-10-02.

- ^ "MX". Herald and Weekly Times (HWT). Retrieved 2008-10-02.

- ^ "Melbourne Radio Stations Australia > Melbourne". Yahoo — geocities. Retrieved 2008-10-02.

- ^ Dunstan, David The evolution of 'Clown Hall', The Age, 12 November 2004, accessed online 7 November 2006

- ^ Local Government Act 1989

- ^ T, Dingle (1991). Vital Connections: Melbourne and its Board of Works. Ringwood, Australia: McPhee Gribble (Penguin).

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Department of Education and Early Childhood Development. "About the Department". www.education.vic.gov.au. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- ^ "Function of the VCAA". VCAA. www.vcaa.vic.edu.au. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- ^ "Schools inequality calls for bold reform". The Age. www.theage.com.au. 17 October 2003. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- ^ How Much Do Public Schools Really Cost? Estimating the Relationship Between House Prices and School Quality, ANU, 6 August 2006

- ^ "SCHOOLS AU S T R A L I A" (PDF). Australian Bureau of Statistics. 11.30 AM (CANBERRA TIME) THURS 23 February 2006. Retrieved 2008-10-24.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "ANU up there with the best". Sydney Morning Herald. 6 October 2005. Retrieved 2006-10-12.

- ^ RMIT. "World's top university cities revealed". www.rmit.net.au. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- ^ "University of Melbourne's international student offers rise — as its demand leaps". University of Melbourne Media Release. uninews.unimelb.edu.au. 12 January 2007. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- ^ Melbourne public hospitals and Metropolitan Health Services Victorian Department of Health

- ^ "Victorian Government Health Information Web site". health services, Victoria. Retrieved 2008-10-05.

- ^ "The cars that ate Melbourne". The Age. theage.com.au. 14 February 2004. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- ^ "Bid to end traffic chaos". The Age. www.theage.com.au. 8 September 2003. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- ^ Trial by public transport: why the system is failing article from The Age

- ^ "$1.2bn sting in the rail". The Age. theage.com.au. 9 April 2006. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- ^ Dowling, Jason (May 5, 2008). "New road cash five times funding of rail" (in The Age). Fairfax Digital. Retrieved 2008-10-22.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "Investing in Transport" (PDF). Victorian Department of Transport. pp. p.69. Retrieved 2008-12-22.

{{cite web}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ "Metlink — Your guide to Public transport in Meloburne and Victoria". Metlink. Retrieved 2008-09-28.

- ^ "Melbourne's Tram History". railpage.org.au. Retrieved 2008-09-28.

- ^ a b "Metlink — Your guide to public transport in Melbourne and Victoria". Metlink-Melbourne. Retrieved 2008-10-05.

- ^ Melbourne and scenes in Victoria 1925–1926 from Victorian Government Railways From the National Library of Australia

- ^ "Melbourne Buses". getting-around-melbourne.com.au. Retrieved 2008-10-05.

- ^ a b Most Liveable and Best Connected? The Economic Benefits of Investing in Public Transport in Melbourne, by Jan Scheurer, Jeff Kenworthy, and Peter Newman

- ^ "Still addicted to cars". Herald Sun. www.news.com.au. 10 October 2007. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- ^ "Public transport makes inroads, but not beyond the fringe". The Age. theage.com.au. 14 January 2008. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- ^ "Victoria's Road Network". VicRoads. Retrieved 2008-10-05.

- ^ "Spirit of Tasmania — One of Australia's great journeys". TT-Line Company Pty Ltd. Retrieved 2008-10-05.

- ^ "Essendon Airport". Essendon Airport Pty Ltd. Retrieved 2008-10-05.

- ^ Melbourne Water. "Dam Water Storage Levels". www.melbournewater.com.au. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- ^ "City of Melbourne — International relations — Sister cities". City of Melbourne. Retrieved 2008-04-04.

- ^ Murray-Smith, Stephen (1989). Right Words: A Guide to English Usage in Australia (2nd ed. ed.). Ringwood, Vic: Viking.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help)