Miles Davis

Miles Davis |

|---|

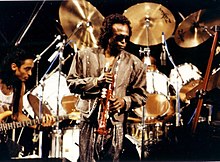

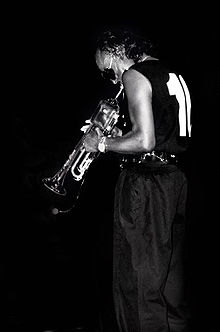

Miles Dewey Davis III (May 26, 1926 – September 28, 1991) was an American jazz trumpeter, bandleader, and composer.

Widely considered one of the most influential musicians of the 20th century, Miles Davis was, with his musical groups, at the forefront of several major developments in jazz music including cool jazz, hard bop, free jazz and fusion. Many well-known jazz musicians made their names as members of Davis' ensembles, including John Coltrane, Herbie Hancock, Bill Evans, Wayne Shorter, Chick Corea, John McLaughlin, Cannonball Adderley, Gerry Mulligan, Tony Williams, George Coleman, J.J. Johnson, Keith Jarrett and Kenny Garrett.

On January 16, 2002, his album Kind of Blue, released in 1959, received its third platinum certification from the RIAA, signifying sales of 3 million copies.[1]

Miles Davis was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2006.[1]

Biography

Early life (1926 to 1944)

Miles Davis was born on May 26, 1926, to a relatively affluent family in Alton, Illinois. His father, Dr. Miles Henry Davis, was a dentist. In 1927, the family moved to East St. Louis. They also owned a substantial ranch in northern Arkansas, where Davis learned to ride horses as a boy.

Davis' mother, Cleota Mae (Henry) Davis, wanted her son to learn the piano; she was a capable blues pianist but kept this fact hidden from her son. His musical studies began at 13, when his father gave him a trumpet and arranged lessons with local musician Elwood Buchanan. Davis later suggested that his father's instrument choice was made largely to irk his wife, who disliked the instrument's sound. Against the fashion of the time, Buchanan stressed the importance of playing without vibrato, and Davis would carry his clear signature tone throughout his career. Buchanan was said to slap Davis' knuckles every time he started using heavy vibrato.[2] Davis once remarked on the importance of this signature sound, saying, "I prefer a round sound with no attitude in it, like a round voice with not too much tremolo and not too much Baseline bass. Just right in the middle. If I can’t get that sound I can’t play anything."[3] Clark Terry was another important early influence.

By the age of 16, Davis was a member of the music society and working professionally when not at school. At 17, he spent a year playing in bandleader Eddie Randle's band, Blue Devils. During this time, Sonny Stitt tried to persuade him to join the Tiny Bradshaw band then passing through town, but Davis's mother insisted that he finish his final year of high school.

In 1944, the Billy Eckstine band visited East St. Louis. Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker were members of the band, and Davis was taken on as third trumpet for a couple of weeks because Buddy Anderson was out sick. When Eckstine's band left Davis behind to complete the tour, the trumpeter's parents were still keen for him to continue formal academic studies.

New York and the bebop years (1945 to 1948)

In the fall of 1944, following graduation from high school, Miles moved to New York City to study at the Juilliard School of Music.

Upon arriving in New York, Davis spent most of his first weeks in town trying to get in contact with Charlie Parker, despite being advised against doing so by several people he met during his quest, including the famous saxophonist Coleman Hawkins.[2]

Having finally succeeded in locating his idol, Davis became part of the milieu of musicians that centered on the jam sessions that were kept nightly in two of Harlem's night clubs, Minton's Playhouse and Monroe's, a group that at the time included many of the future protagonists of the bebop revolution, young musicians such as Fats Navarro, Freddie Webster, J.J. Johnson. Already accredited jazzmen such as Thelonious Monk and Kenny Clarke were also regular attenders of these occasions.

In the same period, he dropped out of Juilliard, having first asked permission from his father. In his autobiography, he criticized the Juilliard classes for centering too much on the classical European and "white" repertoire. He also did partly acknowledge that the Juilliard period contributed to the theoretical background, that he would rely greatly upon in later years.

He began playing professionally in many jazz combos, performing in several 52nd Street clubs with Coleman Hawkins and Eddie "Lockjaw" Davis. In 1945, he entered for the first time in a recording studio as a member of the group of Herbie Fields. This was the first of many recordings to which Davis participated in the following years, most of the time as a sideman. His first studio occasion as a leader came in 1946, with an occasional group called '"Miles Davis Sextet plus Earl Coleman and Ann Hathaway"', one of the rare occasions in which Davis - who was already a member of the Charlie Parker quintet - can be heard accompanying singers.[4] Record dates in which Davis was featured as leader were the exception, rather than the rule, however: the next, isolated, date came around in 1947.

Around 1945, Dizzy Gillespie parted ways with Parker, who hired Davis as Gillespie's replacement in his quintet, which also featured Max Roach at the drums, Al Haig (replaced later by Sir Charles Thompson and Duke Jordan) at the piano, and Curley Russell (later replaced by Tommy Potter and Leonard Gaskin) as bass player.

With Parker's quintet, Davis recorded on several occasions: on an oft-quoted take of Parker's signature song, "Now's the Time", he takes a melodic solo, whose unbop-like quality anticipates the following "cool jazz" period. The group also toured the United States: during a tour in Los Angeles, Parker had a nervous breakdown that landed him in the Camarillo State Mental Hospital for several months, and Davis found himself stranded in L.A. He roomed and collaborated for some time with Charles Mingus, before getting a job with Billy Eckstine on a California tour that brought him back to New York.[5] In 1948, Parker returned from Los Angeles, and Davis joined his group again, resuming recording and public performances as a member of the combo.

The relationships within the group, however, were growing tense. This was in part due to Parker's erratic behavior, attributable to his well known drug addiction) as well as his artistic choices (both Davis and Roach objected to having Duke Jordan as a pianist[2] and would have preferred Bud Powell). In December of that year, economic problems (Davis says he wasn't being paid) began to damage even further his relationship with the band leader, and Davis left the group following a tense confrontation with Parker at the Royal Roost.

For Davis, this marked the beginning of a period in which he worked mainly freelance and as sideman in many of the most important combos of the New York scene.

Birth of the Cool (1948-1949)

In 1948 Davis grew close to the Canadian composer and arranger Gil Evans. Evans' house had become the meeting point of several young musicians and composers (including Davis, Roach, the pianist John Lewis and the baritone sax player Gerry Mulligan) unhappy with the increasingly virtuosic instrumentalism that dominated the bebop scene of the time. Evans had been the arranger for the orchestra of Claude Thornhill and it was the sound of this group, as well as Duke Ellington's example, that suggested the creation of an unusual lineup, a nonet including a french horn and a tuba, which accounts for the "Tuba band" moniker that was to be associated with the combo.

Davis took a very active role in the project,[6] so much so that it soon became "his project". The objective was achieving a sound similar to a human voice, over carefully arranged compositions and giving preeminence to a relaxed and melodic approach in the improvised parts.

The nonet debuted in the summer of 1948, with a two-week appointment at the Royal Roost. The sign announcing the band gave an unusual importance to the role of the arrangers: "Miles Davis Nonet. Arrangements by Gil Evans, John Lewis and Gerry Mulligan". It was, in fact, so unusual that Davis had to persuade the Roost's manager, Ralph Watkins, to hang the sign this way; Davis only prevailed with the help of Monte Kay, the artistic director of the club.

The nonet was active to the end of 1949, undergoing several changes in personnel: Roach and Davis were constantly featured, along with Mulligan, the tuba player Bill Barber, and the altoist Lee Konitz who had been preferred to Sonny Stitt, whose playing was considered too bop oriented. Over the months, John Lewis alternated with Al Haigh at the piano, Mike Zwerin with Kai Winding at the trombone (Johnston was touring at the time), Junior Collins with Sandy Siegelstein and Gunther Schuller at the French Horn and Al McKibbon with Joe Shulman at the bass. The singer Kenny Hagood was added for one track during the recording sessions.

The strong presence of white musicians angered African American jazz players, many of whom were unemployed at the time, but they were angrily dismissed by Davis.[7]

A contract with Capitol Records granted the nonet several recording sessions between January 1949 and April 1950. This material was released in an album whose title - Birth of the Cool - became the namesake of the so called "cool jazz" movement that developed at the same time and partly shared the musical direction championed by Davis' group.

For his part, Davis was fully aware of the importance of his project, which he pursued to the point of turning down a job with Duke Ellington's orchestra.[2]

The importance of the nonet experience was to become clear to the critics and the larger public only in later years but, commercially, the nonet was not a success. The liner notes of the first recordings of the Davis Quintet for Columbia Records call it one of the most spectacular failures of the jazz club scene. This was bitterly noted by Davis, who claimed the invention of the cool style and resented the success that was later attributed by the media to other white "cool jazz" musicians (Mulligan and Dave Brubeck being the front runners).

This experience also marked the beginning of the lifelong friendship between Davis and Gil Evans, an alliance that would bear important results in the following years.

Hard Bop and the "Blue Period" (1950 to 1954)

The first half of the 1950s was, for Davis, a period of great personal difficulty. At the end of 1949, he went on tour in Paris, with a group including - among others - Tadd Dameron, Kenny Clarke (who did not return to the United States after the end of the tour) and James Moody. Davis was fascinated by Paris and its cultural environment, where jazz musicians often felt better respected than in their homeland. He then met the actress Juliette Greco and fell in love with her.

Many of his new and old friends (Davis, in his autobiography, mentions Clarke) tried to persuade him to stay in France, but he decided to return to New York. Back in town, he began to feel deeply depressed. This was due in part to his separation from Greco, in part to his feeling underappreciated by the critics - then hailing some of his former collaborators as heads of the cool jazz movement - and in part to the unravelling of his liaison with one Irene, a former St. Louis schoolmate, who was living with him in New York and with whom he had two children.

These are the factors to which Davis traces his developing a heroin habit that deeply affected him for the next four years. Though Davis denies it in his autobiography, it is likely that the environment in which he was living played a part in this. Most of Davis' associates at the time had - maybe following the example of Charlie Parker - developed drug habits of their own (among them, sax players Sonny Rollins and Dexter Gordon, trumpet players Fats Navarro and Freddie Webster, drummer Art Blakey and many others). For the following four years, Davis supported his habit partly with his musical activity and partly living the life of a hustler.[8] By 1953, his habit was beginning to impair his ability to perform. Heroin had killed some of his friends (Fats Navarro and Freddie Webster). He himself had been arrested for drug possession while on tour in Los Angeles, and his habit had been made public in a devastating interview that Cab Calloway gave to Down Beat.[9]

Realizing his precarious condition, Davis attempted several times to kick the habit, only succeeding in 1954, after returning to his father's home in St. Louis and detaching himself for several months from New York. During this period he played mostly in Detroit and other Midwest towns, where drugs were harder to come by at the time.

In spite of all the personal turmoil the 1950-1954 period was actually quite fruitful from an artistic perspective. Davis had a copious discographic output and had several collaborations with important musicians. He got to know the music of Chicago pianist Ahmad Jamal, whose elegant musical approach and use of space influenced him deeply. He also definitely severed his stylistical ties with bebop.[10]

In 1951, he met Bob Weinstock, owner of Prestige Records, with which he signed a contract. With Prestige, between 1951 and 1954, Davis published many records with several different combos. While the personnel of the recordings varied, the lineup often featured Sonny Rollins and Art Blakey. Davis was particularly fond of Rollins, and tried several times - in the years that preceded his meeting with John Coltrane - to recruit him in a stable group. This never happened, however, mostly due to the fact that Rollins was prone to make himself unavailable for months at a time. In spite of the casual occasions that generated the recordings of these years, their quality is almost always quite high, and they document the artistic path with which Davis was building his style and sound. He began using the Harmon mute, held close to the microphone, in a way that became his signature tone, and his phrasing, especially in ballads, became spacious, melodic and relaxed. This sound was to become so characteristic that the use of the Harmon mute by any jazz trumpet player since immediately brings associations to Davis.

The most important Prestige recordings of this period (Dig, Blue Haze, Bags' Groove, Miles Davis and the Modern Jazz Giants and Walkin') originated mostly from recording sessions in 1951 and 1954, after Davis recovery from his addiction. Also of importance are the five Blue Note recordings, collected in the Miles Davis Volume 1 album.

With this activity, Davis took a center stage position in what is known as the hard bop genre. Hard bop distanced itself from bebop using slower tempos and a less radical approach to harmony and melody, often adopting popular tunes and standards from the American Songbook as starting points for the improvisation. It also distanced itself from cool jazz by virtue of a harder beat and of a constant reference to the blues both traditional form and in the form made popular by rhythm and blues.[11] A few critics[12] go as far as calling "Walkin'" the album that created hard bop, but the point is debated, given the number of musicians that were working along similar lines at the same time (and of course many of them ended up recording or playing with Davis on occasions).

Also in this period Davis gained a reputation for being distant, cold, withdrawn, and for having a quick temper. Among the several factors that contributed to this reputation were his contempt for the critics and specialized press and some well publicized confrontations with the public and with fellow musicians. (One occasion, in which he had a near fight with Thelonious Monk during the recording of Bag's Groove, received wide exposure in the specialized press.[13])

The "nocturnal" quality of his playing and this sombre reputation, along with his whispering voice,[14] earned him the lasting moniker of "Prince of darkness", adding further mystery to his public persona.[15]

First great quintet and sextet (1955 to 1958)

Back in New York and in better health, in 1955 Davis attended the Newport Jazz Festival, where his performance (and especially his solo on 'Round Midnight) was greatly admired and prompted the critics to hail a "return of Miles Davis". At the same time, Davis recruited the players for a formation that became famous as the "First Quintet". The quintet featured Davis at the trumpet, John Coltrane at the tenor saxophone, Red Garland at the piano, Paul Chambers at the bass, and Philly Joe Jones at the drums.

None of these musicians (with the exception of Davis) had received exceptional exposure until that time: Chambers, in particular, was a very young (19 at the time) Detroit player who had been working for about a year in the New York scene, with appearances in the bands of Bennie Green, Paul Quinichette, George Wallington, J. J. Johnson and Kai Winding. Coltrane was little known at the time, in spite of earlier collaborations with Dizzy Gillespie, Earl Bostic and Johnny Hodges: Davis hired him as a replacement for Sonny Rollins, and after having unsuccessfully tried to recruit Cannonball Adderley.

The repertoire included many bebop mainstays, standards from the Great American Songbook and the prebop era, and some traditional tunes.[16] The prevailing style of the group was a prosecution of the Davis experience in the previous years: Davis played long, legato, and essentially melodic lines, while Coltrane (who during these years was revealed as a leading figure of the musical scene) contrasted playing high energy solos.

With the new formation came also a new recording contract. In Newport, Davis had met Columbia Records' producer George Avakian who persuaded him to sign for his label. The quintet made his debut on record with the - extremely well received - Columbia album 'Round About Midnight. Before leaving Prestige, however, Davis had to fulfill his obligations during two days of recording sessions in 1956. Prestige released these recordings in the following years as four albums: Relaxin' with the Miles Davis Quintet. Steamin' with the Miles Davis Quintet, Workin' with the Miles Davis Quintet, and Cookin' with the Miles Davis Quintet. While the recording took place in a studio, each record of this series has the structure and feel of a regular live performance of the quintet, with several first takes on each album; they achieved almost instant classic status and were instrumental in establishing the reputation of Davis' quintet as one of the best formations of the jazz scene.

The quintet was disbanded for the first time in 1957, following a series of personal problems that Davis blames on the drug addiction of the other musicians.[17] Davis played some gigs at the Cafe Bohemia with a short lived formation that included Sonny Rollins and drummer Art Taylor, and then traveled to France, were he recorded the score to Louis Malle's Ascenseur pour l'échafaud. With the aid of French session musicians Barney Wilen, Pierre Michelot and René Urtreger, and American drummer Kenny Clarke, he recorded the entire soundtrack with an innovative procedure, without relying on written material: starting from sparse indication on the harmony and general feel of a given piece, the group played by watching at the movie on a screen in front of them and improvising.

Returning to New York in 1958, Davis recruited altoist Julian "Cannonball" Adderley. Coltrane, who in the meantime had freed himself from drugs, was available after a highly fruitful experience with Thelonious Monk and was hired back, as was Philly Joe Jones. With the quintet reformed as a sextet, Davis recorded Milestones, an album anticipating the new directions he was preparing to give to his music.

Almost immediately after the recording of Milestones, Davis fired Garland and - shortly after - Jones, again for behavioral problems, replacing them with Bill Evans - a young, white piano player with a strong classical background - and drummer Jimmy Cobb. With this revamped formation, Davis entered a year during which the sextet performed and toured extensively and producing a record (1958 Miles, also known as "58 Sessions"). Evans had a unique, impressionistic approach to the piano and his musical ideas had a strong influence on Davis. But, after only eight months on the road with the group, he was burned out and left. He was soon replaced by Wynton Kelly, a player who brought to the sextet a swinging, bluesy approach in substitution to Evans' more delicate playing.

Recordings with Gil Evans (1957 to 1963)

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Davis recorded a series of albums with Gil Evans, often playing flugelhorn as well as trumpet. The first, Miles Ahead (1957), showcased his playing with a jazz big band and a horn section beautifully arranged by Evans. Songs included Dave Brubeck's "The Duke," as well as Léo Delibes' "The Maids Of Cadiz," the first piece of European classical music Davis had recorded. Another distinctive feature of the album were the orchestral passages that Evans had devised as transitions among the different tracks, that were then joined together with the innovative use of editing in the post-production phase, turning each side of the album into a seamless piece of music.[18]

In 1958, Davis and Evans were back in the studio for the recording of Porgy and Bess, an arrangement of pieces from George Gershwin's opera of the same name. The orchestra lineup included three members of the sextet: Paul Chambers, Philly Joe Jones, and Julian "Cannonball" Adderley. Davis named the album one of his own favorites.

Sketches of Spain (1959–1960) featured songs by contemporary Spanish composer Joaquin Rodrigo and also Manuel de Falla, as well as Gil Evans originals with a Spanish theme. Miles Davis at Carnegie Hall (1961) includes Rodrigo's Concierto de Aranjuez, along with other songs recorded at a concert with an orchestra under Evans' direction.

Sessions in 1962 resulted in the album Quiet Nights, a short collection of bossa nova songs that was released against the wishes of both artists. That was the last time that the two created a full album again. In his autobiography, Davis noted that ". . . my best friend is Gil Evans".[19]

Kind of Blue (1959 to 1964)

In March and April 1959, Davis re-entered the studio with his working sextet to record what is widely considered his magnum opus, Kind of Blue. He called back Bill Evans, months away from forming what would become his seminal trio, for the album sessions as the music had been planned around Evans' piano style.[20] Both Davis and Evans had direct familiarity with the ideas of pianist George Russell regarding modal jazz, Davis from discussions with Russell and others before what came to be known as the Birth of the Cool sessions, and Evans from study with Russell in 1956.[21] Miles, however, had neglected to inform current pianist Kelly as to Evans's role in the recordings, Kelly subsequently playing only on the track "Freddie Freeloader", and not being present at all on the April dates for the album.[22] "So What" and "All Blues" had been played by the sextet at performances prior to the recording sessions, but for the other three compositions, Davis and Evans prepared skeletal harmonic frameworks which the other musicians saw for the first time on the day of recording, to generate an improvisational approach. The resulting album has proven to be a huge influence on other musicians. According to the RIAA, Kind of Blue is the best-selling jazz album of all time, having been certified as quadruple platinum (4 million copies sold).

The same year, while taking a break outside the famous Birdland nightclub in New York City, Davis was beaten by the New York police and subsequently arrested. Believing the assault to have been racially motivated (it is said he was beaten by a single policeman who was angered by Davis being with a white woman), he attempted to pursue the case in the courts, before eventually dropping the proceedings in a plea bargain to recover his suspended Cabaret Card.

Davis persuaded Coltrane to play with the group on one final European tour in the spring of 1960. Coltrane then departed to form his classic quartet, although he returned for some of the tracks on the 1961 album Someday My Prince Will Come. Davis tried various replacement saxophonists, including Jimmy Heath, Sonny Stitt and Hank Mobley. The quintet with Hank Mobley was recorded in the studio and on several live engagements at Carnegie Hall and the Black Hawk jazz club in San Francisco. Stitt's playing with the group is found on both a recording made in Olympia, Paris (where Davis and Coltrane had played a few months before) and the Live in Stockholm album.

In 1963, Davis' long-time rhythm section of Kelly, Chambers, and Cobb departed. He quickly got to work putting together a new group, including tenor saxophonist George Coleman and bassist Ron Carter. Davis, Coleman, Carter, and a few other musicians recorded half an album in the spring of 1963. A few weeks later, drummer Tony Williams and pianist Herbie Hancock joined the group, and soon thereafter Davis, Coleman and the rhythm section recorded the rest of Seven Steps to Heaven.

The rhythm section clicked very quickly with each other and the horns; the group's rapid evolution can be traced through the aforementioned studio album, In Europe (July 1963), My Funny Valentine, and Four and More (both February 1964). The group played essentially the same repertoire of bebop and standards that earlier Davis bands did, but tackled them with increasing structural and rhythmic freedom and (in the case of the up-tempo material) breakneck speed.

Coleman left in the spring of 1964, to be replaced by avant-garde saxophonist Sam Rivers, on the suggestion of Tony Williams. Rivers remained in the group only briefly, but was recorded live with the quintet in Japan; the group can be heard on In Tokyo! (July 1964).

By the end of the summer, Davis had convinced Wayne Shorter to quit Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers. Shorter became the principal composer of Davis' quintet, and some of his compositions of this era ("Footprints," "Nefertiti") are now standards. While on tour in Europe, the group quickly made their first official recording, Miles in Berlin (Fall 1964). On return to the United States later that year, Davis (at Jackie DeShannon's urging) was instrumental in getting The Byrds signed to Columbia Records.

Second great quintet (1964 to 1968)

By the time of E.S.P. (1965) Davis' lineup consisted of Wayne Shorter, Herbie Hancock, Ron Carter (bass) and Tony Williams (drums). This lineup, the last of his acoustic bands, is often known as "the second great quintet."

A two-night Chicago gig in late 1965 is captured on The Complete Live at The Plugged Nickel 1965, released in 1995. Unlike the group's studio albums, the live engagement shows the group still playing primarily standards and bebop songs.

This was followed by a series of studio recordings: Miles Smiles (1966), Sorcerer (1967), Nefertiti (1967), Miles in the Sky (1968) and Filles de Kilimanjaro (1968). The quintet's approach to improvisation came to be known as "time no changes" or "freebop," because they abandoned the chord-change-based approach of bebop for a modal approach. Through Nefertiti, the studio recordings consisted primarily of originals composed by Shorter, and to a lesser degree of compositions by the other sidemen. In 1967, the group began to play their live concerts in continuous sets, with each tune flowing into the next and only the melody indicating any sort of demarcation; Davis's bands would continue to perform in this way until his retirement in 1975.

Miles in the Sky and Filles de Kilimanjaro, on which electric bass, electric piano and guitar were tentatively introduced on some tracks, pointed the way to the subsequent fusion phase in Davis' output. Davis also began experimenting with more rock-oriented rhythms on these records. By the time the second half of Filles de Kilimanjaro had been recorded, Dave Holland and Chick Corea had replaced Carter and Hancock in the working band, though both Carter and Hancock would occasionally contribute to future recording sessions. Davis soon began to take over the compositional duties of his sidemen.

Electric Miles (1968 to 1975)

This article may contain improper use of non-free material. |

Davis' influences included late 1960s acid rock and funk artists such as Sly and the Family Stone, James Brown and Jimi Hendrix,[1] many of whom he met through Betty Mabry, a young model and songwriter Davis married in September 1968 and divorced a year later. The musical transition required that Davis and his band adapt to electric instruments in both live performances and the studio.

By the time In a Silent Way had been recorded in February 1969, Davis had augmented his standard quintet with additional players. At various times Hancock or Joe Zawinul were brought in to augment Corea on electric keyboards, and guitarist John McLaughlin made the first of his many appearances. By this point, Shorter was also doubling on soprano saxophone. After recording this album, Williams left to form his group Lifetime and was replaced by Jack DeJohnette.

Six months later an even larger group of musicians, including Jack DeJohnette, Airto Moreira and Bennie Maupin recorded the double LP Bitches Brew, which became a huge seller, hitting gold status by 1976. This album and In a Silent Way were among the first fusions of jazz and rock that were commercially successful, building on the groundwork laid by Charles Lloyd, Larry Coryell, and many others who pioneered a genre that would become known simply as "Jazz-rock fusion."

During this period, Davis toured with Shorter, Corea, Holland and DeJohnette. The group's repertoire included material from Bitches Brew, In a Silent Way, the 1960s quintet albums, and an occasional standard.

In 1972, Davis was introduced to the music of Karlheinz Stockhausen by Paul Buckmaster, leading to a period of new creative exploration for Davis. Biographer J.K. Chambers wrote that "The effect of Davis's study of Stockhausen could not be repressed for long. ... Davis's own 'space music' shows Stockhausen's influence compositionally."[23] His recordings and performances during this period were described as "space music" by fans, by music critic Leonard Feather, and by Buckmaster, who stated: "a lot of mood changes — heavy, dark, intense — definitely space music."[24][25]

Both Bitches Brew and In a Silent Way feature "extended" (more than 20 minutes each) compositions that were never actually "played straight through" by the musicians in the studio.[citation needed] Instead, Davis and producer Teo Macero selected musical motifs of various lengths from recorded extended improvisations and edited them together into a musical whole which only exists in the recorded version. Bitches Brew made use of such electronic effects as multi-tracking, tape loops and other editing techniques.[26] Both records, especially Bitches Brew, proved to be huge sellers.

Starting with Bitches Brew, Davis' albums began to often feature cover art much more in line with psychedelic art or black power movements than that of his earlier albums. He took significant cuts in his usual performing fees in order to open for rock groups like the Steve Miller Band, the Grateful Dead and Santana. Several live albums were recorded during the early 1970s at such performances: Live at the Fillmore East, March 7, 1970: It's About That Time (March 1970), Black Beauty (April 1970) and Miles Davis at Fillmore: Live at the Fillmore East (June 1970).[1]

By the time of Live-Evil in December 1970, Davis' ensemble had transformed into a much more funk-oriented group. Davis began experimenting with wah-wah effects on his horn. The ensemble with Gary Bartz, Keith Jarrett and Michael Henderson, often referred to as the "Cellar Door band" (the live portions of Live-Evil were recorded at a club by that name), never recorded in the studio, but is documented in the six CD Box Set The Cellar Door Sessions, which was recorded over four nights in December 1970. [citation needed]

In 1970, Davis contributed extensively to the soundtrack of a documentary about the African-American boxer heavyweight champion Jack Johnson. Himself a devotee of boxing, Davis drew parallels between Johnson, whose career had been defined by the fruitless search for a Great White Hope to dethrone him, and Davis' own career, in which he felt the musical establishment of the time had prevented him from receiving the acclaim and rewards that were due him.[citation needed] The resulting album, 1971's A Tribute to Jack Johnson, contained two long pieces that utilized musicians (some of whom were not credited on the record) including guitarists John McLaughlin and Sonny Sharrock, Herbie Hancock on a Farfisa organ and drummer Billy Cobham. McLaughlin and Cobham went on to become founding members of the Mahavishnu Orchestra in 1971.

As Davis stated in his autobiography, he wanted to make music for the young African-American audience. On the Corner (1972) blended funk elements with the traditional jazz styles he had played his entire career. The album was highlighted by the appearance of saxophonist Carlos Garnett. Critics were not kind to the album; in his autobiography, Davis stated that critics could not categorize it and complained that the album was not promoted by the "traditional" jazz radio stations. [citation needed]

After recording On the Corner, Davis put together a new band, with only Michael Henderson, Carlos Garnett and percussionist Mtume returning from the previous band. It included guitarist Reggie Lucas, tabla player Badal Roy, sitarist Khalil Balakrishna and drummer Al Foster. It was unusual in that none of the sidemen were major jazz instrumentalists; as a result, the music emphasized rhythmic density and shifting textures instead of individual solos. This group, which recorded in the Philharmonic Hall for the album In Concert (1972), was unsatisfactory to Davis. Through the first half of 1973, he dropped the tabla and sitar, took over keyboard duties, and added guitarist Pete Cosey. The Davis/Cosey/Lucas/Henderson/Mtume/Foster ensemble would remain virtually intact over the next two years. Initially, Dave Liebman played saxophones and flute with the band. In 1974, he was replaced by Sonny Fortune.

Big Fun (1974) was a double album containing four long jams, recorded between 1969 and 1972. Similarly, Get Up With It (1974) collected recordings from the previous five years. Get Up With It included "He Loved Him Madly", a tribute to Duke Ellington, as well as one of Davis' most lauded pieces from this era, "Calypso Frelimo". This was his last studio album of the 1970s.

In 1974 and 1975, Columbia recorded three double-LP live Davis albums: Dark Magus, Agharta and Pangaea. Dark Magus is a 1974 New York concert; the latter two are recordings of consecutive concerts from the same February 1975 day in Osaka. At the time, only Agharta was available in the US; Pangaea and Dark Magus were initially released only by CBS/Sony Japan. All three feature at least two electric guitarists (Reggie Lucas and Pete Cosey, deploying an array of post-Hendrix electronic distortion devices; Dominique Gaumont is a third guitarist on Dark Magus), electric bass, drums, reeds, and Davis on electric trumpet and organ. These albums were the last he was to record for five years. Davis was troubled by osteoarthritis (which led to a hip replacement operation in 1976, the first of several), sickle-cell anemia, depression, bursitis, ulcers and a renewed dependence on alcohol and drugs (primarily cocaine), and his performances were routinely panned throughout late 1974 and early 1975. By the time the group reached Japan in February 1975, Davis was teetering on a physical breakdown and required copious amounts of vodka and narcotics to complete his engagements.

After a Newport Jazz Festival performance at Avery Fisher Hall in New York on July 1, 1975, Davis withdrew almost completely from the public eye for six years. As Gil Evans said, "His organism is tired. And after all the music he's contributed for 35 years, he needs a rest." [citation needed]

Davis characterized this period in his memoirs as a colorful time when wealthy women lavished him with sex and drugs. In reality, he had become completely dependent upon various drugs, spending nearly all of his time propped up on a couch in his apartment watching television, leaving only to score more drugs. In 1976, Rolling Stone reported rumors of his imminent demise. Although he stopped practicing trumpet on a regular basis, Davis continued to compose intermittently and made three attempts at recording during his exile from performing; these sessions (one with the assistance of Paul Buckmaster and Gil Evans, who left after not receiving promised compensation) bore little fruit and remain unreleased.

In 1979, he placed in the yearly Top 10 trumpeter poll of Down Beat magazine. Columbia continued to issue compilation albums and records of unreleased vault material to fulfill contractual obligations.

During his period of inactivity, Davis saw the fusion music that he had spearheaded over the past decade firmly enter into the mainstream. When he emerged from retirement, Davis' musical descendants would be in the realm of New Wave rock, and in particular the stylings of Prince.

Last decade (1981 to 1991)

By 1979, Davis had rekindled his relationship with actress Cicely Tyson. With Tyson, Davis would overcome his cocaine addiction and regain his enthusiasm for music. As he had not played trumpet for the better part of three years, regaining his famed embouchure proved to be particularly arduous. While recording The Man with the Horn (sessions were spread sporadically over 1979–1981), Davis played mostly wah-wah with a younger, larger band.

The initial large band was eventually abandoned in favor of a smaller combo featuring saxophonist Bill Evans and bass player Marcus Miller, both of whom would be among Davis's most regular collaborators throughout the decade. He married Tyson in 1981; they would divorce in 1988. The Man with the Horn was finally released in 1981 and received a poor critical reception despite selling fairly well. In May, the new band played two dates as part of the Newport Jazz Festival. The concerts, as well as the live recording We Want Miles from the ensuing tour, received positive reviews.

By late 1982, Davis's band included French percussionist Mino Cinelu and guitarist John Scofield, with whom he worked closely on the album Star People. In mid-1983, while working on the tracks for Decoy, an album mixing soul music and electronica that was released in 1984, Davis brought in producer, composer and keyboardist Robert Irving III, who had earlier collaborated with Davis on The Man with the Horn. With a seven-piece band, including Scofield, Evans, keyboardist and music director Irving, drummer Al Foster and bassist Darryl Jones (later of The Rolling Stones), Davis played a series of European gigs to positive receptions. While in Europe, he took part in the recording of Aura, an orchestral tribute to Davis composed by Danish trumpeter Palle Mikkelborg.

You're Under Arrest, Davis' next album, was released in 1985 and included another brief stylistic detour. Included on the album were his interpretations of Cyndi Lauper's ballad "Time After Time," and "Human Nature" from Michael Jackson. Davis considered releasing an entire album of pop songs and recorded dozens of them, but the idea was scrapped.[27] Davis noted that many of today's accepted jazz standards were in fact pop songs from Broadway theater, and that he was simply updating the "standards" repertoire with new material.

You're Under Arrest also proved to be Davis' final album for Columbia. Trumpeter Wynton Marsalis publicly dismissed Davis' more recent fusion recordings as not being "'true' jazz," comments Davis initially shrugged off, calling Marsalis "a nice young man, only confused". This changed after Marsalis appeared, unannounced, onstage in the midst of a Davis performance. Marsalis whispered into Davis' ear that "someone" had told him to do so; Davis responded by ordering him off the stage.[28]

Davis grew irritated at Columbia's delay releasing Aura. The breaking point in the label/artist relationship appears to have come when a Columbia jazz producer requested Davis place a good-will birthday call to Marsalis. Davis signed with Warner Brothers shortly thereafter.

Davis collaborated with a number of figures from the British new wave movement during this period, including Scritti Politti.[29] At the invitation of producer Bill Laswell, Davis recorded some trumpet parts during sessions for Public Image Ltd.'s Album, according to Public Image's John Lydon in the liner notes of their Plastic Box box set. In Lydon's words, however, "strangely enough, we didn't use (his contributions)." (Also according to Lydon in the Plastic Box notes, Davis favorably compared Lydon's singing voice to his trumpet sound.)[30]

Having first taken part in the Artists United Against Apartheid recording, Davis signed with Warner Brothers records and reunited with Marcus Miller. The resulting record, Tutu (1986), would be his first to use modern studio tools — programmed synthesizers, samples and drum loops — to create an entirely new setting for Davis' playing. Ecstatically reviewed on its release, the album would frequently be described as the modern counterpart of Sketches of Spain and won a Grammy in 1987.

He followed Tutu with Amandla, another collaboration with Miller and George Duke, plus the soundtracks to four movies: Street Smart, Siesta, The Hot Spot, and Dingo. He continued to tour with a band of constantly rotating personnel and a critical stock at a level higher than it had been for 15 years. His last recordings, both released posthumously, were the hip hop-influenced studio album Doo-Bop and Miles & Quincy Live at Montreux, a collaboration with Quincy Jones for the 1991 Montreux Jazz Festival in which Davis performed the repertoire from his 1940s and 1950s recordings for the first time in decades.

In 1988 he had a small part as a street musician in the film Scrooged, starring Bill Murray. He received the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award in 1990.

In early 1991, he appeared in the Rolf de Heer film Dingo as a jazz musician. In the film's opening sequence, Davis and his band unexpectedly land on a remote airstrip in the Australian outback and proceed to perform for the stunned locals. The performance was one of Davis' last on film.

Miles Davis died on September 28, 1991 from a stroke, pneumonia and respiratory failure in Santa Monica, California at the age of 65.[1] He is buried in Woodlawn Cemetery in The Bronx.

Awards

- Winner; Down Beat Reader's Poll Best Trumpet Player 1955

- Winner; Down Beat Reader's Poll Best Trumpet Player 1957

- Winner; Down Beat Reader's Poll Best Trumpet Player 1961

- Grammy Award for Best Jazz Composition Of More Than Five Minutes Duration for Sketches of Spain (1960)

- Grammy Award for Best Jazz Performance, Large Group Or Soloist With Large Group for Bitches Brew (1970)

- Grammy Award for Best Jazz Instrumental Performance, Soloist for We Want Miles (1982)

- Sonning Award for Lifetime Achievement In Music (1984; Copenhagen, Denmark)

- Doctor of Music, honoris causa (1986; New England Conservatory)

- Grammy Award for Best Jazz Instrumental Performance, Soloist for Tutu (1986)

- Grammy Award for Best Jazz Instrumental Performance, Soloist for Aura (1989)

- Grammy Award for Best Jazz Instrumental Performance, Big Band for Aura (1989)

- Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award (1990)

- Australian Film Institute Award for Best Original Music Score for Dingo, shared with Michel Legrand (1991)

- Knighted into the Legion of Honor (July 16, 1991; Paris)

- Grammy Award for Best R&B Instrumental Performance for Doo-Bop (1992)

- Grammy Award for Best Large Jazz Ensemble Performance for Miles & Quincy Live at Montreux (1993)

- Hollywood Walk of Fame Star (February 19, 1998)

- Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Induction (March 13, 2006)

- Hollywood's Rockwalk Induction (September 28, 2006)

- RIAA Quadruple Platinum for Kind of Blue

- St. Louis Walk of Fame

Discography

Sidemen

Rhythm Section

- 1950: Pianist John Lewis, bassist Al McKibbon, drummer Max Roach

- 1951: Pianist Walter Bishop, Jr., bassist Tommy Potter, drummer Art Blakey

- 1956: Pianist Tommy Flanagan, bassist Paul Chambers, drummer Art Taylor

- 1955-58: Pianist Red Garland, bassist Paul Chambers, drummer Philly Joe Jones

- 1959-63: Pianist Wynton Kelly, bassist Paul Chambers, drummer Jimmy Cobb

- 1963-68: Pianist Herbie Hancock, bassist Ron Carter, drummer Tony Williams

- 1971: Pianist Keith Jarrett, bassist Michael Henderson, drummer Jack DeJohnette, percussionist Airto Moreira

- 1969-72: Pianists Joe Zawinul, Chick Corea, Keith Jarrett, Herbie Hancock, Larry Young, Harold Williams, Hermeto Pascoal, Lonnie Liston Smith, Cedric Lawson

- 1970s: Guitarists Reggie Lucas, Pete Cosey, David Creamer, Dominique Gaumont, Cornell Dupree

Notes

- ^ a b c d e "Miles Davis". The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum, Inc. Retrieved 2009-06-29.

- ^ a b c d Miles Davis and Quincy Troupe, Miles: The Autobiography, Simon and Schuster, 1989, ISBN 0671635042.

- ^ Ashley Kahn Kind of Blue: The Making of the Miles Davis Masterpiece.

- ^ See the Plosin session database [1].

- ^ On this occasion, Mingus criticized bitterly Davis for abandoning his "musical father" (see Autobiography).

- ^ "Miles, the bandleader. He took the initiative and put the theories to work. He called the rehearsals, hired the halls, called the players, and generally cracked the whip." Gerry Mulligan "I hear America singing".

- ^ "So I just told them that if a guy could play as good as Lee Konitz played - that's who they were mad about most, because there were a lot of black alto players around - I would hire him every time, and I wouldn't give a damn if he was green with red breath. I'm hiring a motherfucker to play, not for what color he is." Miles Davis, Autobiography

- ^ In his autobiography Davis recalls exploiting prostitutes and getting money from most of his friends.

- ^ In his autobiography, Davis says he never forgave Calloway for that interview. He also says that African Americans were being unfairly singled out as drug users among the larger community of jazz musicians who used drugs at the time.

- ^ "Back in bebop, everybody used to play real fast. But I didn't ever like playing a bunch of scales and shit. I always tried to play the most important notes in the chord, to break it up. I used to hear all them musicians playing all them scales and notes and never nothing you could remember." - Miles Davis, The Autobiography.

- ^ Open references to the blues in jazz playing were fairly recent. Until the middle of the 1930s, as Coleman Hawkins declared to Alan Lomax (The Land Where The Blues Began. New York: Pantheon, 1993), African american players working in white establishments would avoid references to the blues altogether.

- ^ Ashley Kahn (op. cit.) among them.

- ^ Davis had asked Monk to "lay off" (stop playing) while he was soloing. In the autobiography, Davis says that Monk "Could not play behind a horn". Charles Mingus reported this, and more, in his "Open Letter to Miles Davis".

- ^ Acquired by shouting at a record producer while still ailing after a recent operation to the throat - Autobiography

- ^ Davis began to be referred to as "the Prince of Darkness" in liner notes of the records of this period, and the moniker persists to this day, see for instance his obituary on "The Nation", and countless references in DVD [2], movies [3] and print articles [4].

- ^ Some inspired by Ahmad Jamal: see for instance the performance of "Billy Boy" on Milestones.

- ^ Especially Jones and Coltrane, whom Davis both fired. Davis - Autobiography.

- ^ Cook, op. cit.

- ^ You Can't Steal a Gift: Dizzy, Clark, Milt, and Nat, by Lees, Gene, Yale University Press (2001), p. 24

- ^ Khan, Ashley. Kind of Blue: The Making of the Miles Davis Masterpiece. New York: Da Capo Press, 2000; ISBN 0-306-81067-0, p.95.

- ^ Ibid., pp. 29–30, p. 74.

- ^ Ibid., p. 95.

- ^ Chambers, J. K. (1998). Milestones: The Music and Times of Miles Davis. Da Capo Press. p. 246. ISBN 0306808498.

- ^ Carr, Ian (1998). Miles Davis: The Definitive Biography. Thunder's Mouth Press. pp. 284, 303, 304, 306. ISBN 1560252413.

- ^ Tingen, Paul (Thursday, April 17, 2008 5:02:21 PM). "Miles Beyond: The Making of Bitches Brew". Retrieved 2009-06-29.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Freeman, Philip (November 1, 2005). Running the Voodoo Down: The Electric Music of Miles Davis. San Francisco, CA: Backbeat Books. pp. 83–84. ISBN 978-0879308285.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ The Last Years of Miles Davis Songfacts. Retrieved January 14, 2009.

- ^ Miles: The Autobiography, Picador, page 364.

- ^ Intro.de article (in German).

- ^ Fodderstompf

References

This article includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. (April 2009) |

- Carr, Ian. Miles Davis. ISBN 0-00-653026-5.

- Chambers, Jack. Milestones: The Music and Times of Miles Davis. ISBN 0-306-80849-8.

- Cole, George. The Last Miles: The Music of Miles Davis 1980 – 1991. ISBN 1-904768-18-0.

- Cook, Richard (2007). "It's About That Time: Miles Davis On and Off Record". Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195322668

- Davis, Miles & Troupe, Quincy. Miles: The Autobiography. ISBN 0-671-63504-2.

- Davis, Gregory. Dark Magus: The Jekyll & Hyde Life of Miles Davis. ISBN 978-0-87930-875-9. [5]

- Early, Gerald. Miles Davis and American Culture. ISBN 1-883982-37-5 cloth, ISBN 1-883982-38-3, paper.

- Szwed, John. So What: The Life of Miles Davis. ISBN 0-434-00759-5.

- Tingen, Paul. Miles Beyond: The Electric Explorations of Miles Davis, 1967–1991. ISBN 0-8230-8360-8. [6]

- Mandel, Howard (2007). "Miles, Ornette, Cecil: Jazz Beyond Jazz". Routledge. ISBN 0415967147.

External links

Web sites dedicated to Miles Davis:

- Miles Davis - official website.

- Miles Davis - official Sony Music website.

- Miles Ahead - large site dedicated to Miles Davis, contains an extensive data base of sessions and a Discography.

- The Sound of Miles Davis - site dedicated to Jan Lohmann's pioneering discography of all Davis's recordings.

- Miles Beyond - Paul Tingen's book and web site on the electric music of Miles Davis, 1967–1991.

- The Last Miles - George Cole's book and website on the last decade of Miles Davis's music.

- Milestones: A Miles Davis Collector's Site - collector's site with much material.

Web site pages about Miles Davis:

- Miles Davis discography at Discogs.

- Miles Davis at AllMusic.

- Miles Davis at All About Jazz.

- Miles Davis at IMDb.

- Miles Davis biography at the African American Registry.

- Miles Davis in the Encyclopaedia Britannica.

- Sons of Miles: Interviews and profiles with Miles Davis and musicians influenced by him.

- Miles Davis Multimedia Directory at Kerouac Alley.

- African American musicians

- American jazz bandleaders

- American jazz composers

- American jazz trumpeters

- American songwriters

- Avant-garde trumpeters

- Bebop trumpeters

- Cool jazz trumpeters

- Deaths from stroke

- Deaths from respiratory failure

- People with sickle-cell disease

- Grammy Award winners

- Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award winners

- Columbia Records artists

- Capitol Records artists

- Prestige Records artists

- Savoy Records artists

- Hard bop trumpeters

- Musicians from Illinois

- Juilliard School of Music alumni

- Miles Davis

- Modal jazz trumpeters

- People from Madison County, Illinois

- People from St. Clair County, Illinois

- Rock and Roll Hall of Fame inductees

- Music of St. Louis, Missouri

- Third Stream trumpeters

- Deaths from pneumonia

- Burials at Woodlawn Cemetery (The Bronx)

- Infectious disease deaths in California

- 1926 births

- 1991 deaths