Arab Christians

This article may require copy editing for grammar, style, cohesion, tone, or spelling. (July 2010) |

File:Michel Aflaq.jpg File:Michel Aflaq.jpg     File:Suleiman1.jpg File:Suleiman1.jpg    File:TariqAziz.jpg File:TariqAziz.jpg | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| approx. 14,000,000 [1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 15,000,000-18,000,000 (do not self-identify as Arabs)[2] | |

| 8,000,000 | |

| 1,350,000-1,600,000 | |

| 1,200,000 | |

| 1,100,000 | |

| 970,000-1,700,000[3] | |

| 750.000[3] | |

| 636,000[3] | |

| 350,000 | |

| 350,000 | |

| 163,000-220,000[3] | |

| 154,000[4] | |

| 140,000 | |

| 75,500 | |

| 18,000[5] | |

| Languages | |

| Arabic, Armenian, Aramaic, Hebrew, Greek, English, French, Portuguese, Spanish, other European languages | |

| Religion | |

| Melkite Greek Catholic Church, Greek Orthodox Church, Maronite Catholic Church, Chaldean Catholic Church, Syriac Catholic Church, Syriac Orthodox Church, Nestorian Church, Roman Catholic Church, Protestant Church | |

Christian Arabs or Arabic-speaking Christians are Christians who may or may not identify themselves with the panethnicity term Arab.

This grouping of Christian peoples may be of various ancestral origins whose members identify as such on one or more of the grounds of language, culture, or genealogy. The main difference is that some Christian groups are of non-Arab ethnicity, such as Assyrians, Phoenicians and Chaldeans, who are of Aramaic descent, and who originate from Southwest Asia. They often have their own native dialects of Aramaic, in addition to speaking the local and national Arabic dialects. This also applies to the Copts who are of Egyptian non-Arab descent, and who do not self-identify as Arabs.

Large numbers of self-identified Arab Christians are found in Southwest Asia, particularly in Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, Iraq, Israel, West Bank and Gaza Strip, while large numbers of Arabic-speaking Christians who do not self-identify as Arabs can be found in Egypt, Lebanon and Iraq. Emigrants from these Christian communities make up a significant portion of the Middle Eastern diaspora, with high population concentrations in the Americas, particularly in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Mexico, Peru, Trinidad and Tobago, the United States and Venezuela.

History

The New Testament has a biblical account of Arab conversion to Christianity in the book of Acts in Jerusalem in the witness of St. Peter, Chapter 2: Verse 11: "(both Jews and converts to Judaism); Cretans and Arabs-we hear them declaring the wonders of God in our own tongues!"[6][7] Arab Christians are thus one of the oldest Christian communities.

The first mention of Christianity in Arab lands occurs in the New Testament as the Apostle Paul refers to his journey in Arabia following his conversion (Galatians 1: 15-17). Later, Eusebius of Caesarea discusses a bishop named Beryllus in the see of Bostra, the site of a synod c. 240 and two Councils of Arabia. Christians existed in Arab lands from the 3rd century onward.[8]

Some modern scholars suggest that Philip the Arab was the first Christian emperor of Rome.[8] By the 4th century a significant number of Christians occupied the Sinai peninsula, Mesopotamia and Arabia. Others say that the first Christian ruler in history was an Arab called Abgar VIII of Edessa, who converted to Christianity.

Throughout many eras of history, Arab Christians have co-existed fairly peacefully with their fellow non-Christian Arab neighbours, principally Muslims and Jews. Even after the rapid expansion of Islam from the 7th century onwards through the Islamic conquests, many Christians chose not to convert to Islam and instead still maintain their pre-existing beliefs.

As "People of the Book", Christians in the region are accorded certain rights by Islamic law (Shari'ah) to practice their religion, strictly conditioned, however, on paying a tax required from non-Muslims called 'Jizyah' (pronounced Jiz-ya), in form of either cash or goods. The tax was not levied on slaves, women, children, monks, the old, the sick,[9][10] hermits, or the poor.[11]

Dr Walid Phares writes about Arab Christians persecuted by Pan Arabists' forced Arabization [12]

Arab Christians, and Arabic-speaking Jews for that matter, predate Arab Muslims, as there were many Arab tribes which adhered to Christianity since the 1st century, including the Nabateans and the Ghassanids. The latter were of Qahtani origin and spoke Yemeni-Arabic as well as Greek who protected the south-eastern frontiers of the Roman and Byzantine Empires in north Arabia.[citation needed]

The tribes of Tayy, Abd Al-Qais, and Taghlib are also known to have included a large number of Christians prior to Islam. The Yemenite city of Najran was also a center of Arabian Christianity, made famous by the persecution by one of the kings of Yemen, Dhu Nawas, who was himself an enthusiastic convert to Judaism. The leader of the Arabs of Najran during the period of persecution, Al-Harith, was canonized by the Roman Catholic Church as St. Aretas.

Christians today

Syria

In Syria, Christians formed just under 15% of the population (about 1.2 million people) under the 1960 census, but no newer census has been taken. Current estimates put them at about 10% of the population (2,000,000), due to lower rates of birth and higher rates of emigration than their Muslim compatriots. Most Christians are Greek Orthodox , Greek Catholic and Maronite, with some Roman Catholics.

Iraq

The Christians of Iraq are one of the oldest Christian communities of the Middle East. In Iraq, Christians numbered about 636,000 in 2005, representing 3% of the population of the country. They had numbered over 1 million in 1980, or 7% of the population. Almost 400,000 have fled to other countries, especially after the Invasion of Iraq in 2003. Apart from emigration, the Iraqi Christians are also declining due to lower rates of birth and higher death rates than their Muslim compatriots. Today, the Christians are suffering from lack of security since the invasion in 2003. The vast majority of them live in the capital Baghdad and in Mosul,[13] The majority of the Iraqi Christians belong to the Chaldean Catholic Church - (which represents 350,000 persons), Assyrian Church of the East, Ancient Church of the East, Syriac Catholic Church and Syriac Orthodox Church. The Iraqi former foreign minister and deputy prime minister Tariq Aziz is probably one of the most famous Iraqi Christians.

Lebanon

The earliest indisputable tradition of Christianity in Lebanon can be traced back to Saint Maron in the 4th century, the founder of national and ecclesiastical Maronitism. Saint Maron adopted an ascetic recluse life on the banks of the Orontes river in the vicinity of Homs–Syria and founded a community of monks which began to preach the gospel in the surrounding areas. The Saint Maron Monastery was too close to Antioch, making the monks vulnerable to emperor Justinian II’s persecution. To escape persecution, Saint John Maron, the first Maronite patriarch-elect, lead his monks into the Lebanese mountains; the Maronite monks finally settled in the Qadisha valley. During the Muslim conquest, Muslims persecuted the Christians, particularly the Maronites, with the persecution reaching a peak during the Umayyad caliphate; nevertheless the influence of the Maronite establishment spread throughout the Lebanese mountains and became a considerable feudal force[citation needed]. After the Muslim Conquest, the Maronite Church had become isolated and did not reestablish contact with the Church of Rome until the 12th century.[14] According to Kamal Salibi some Maronites may have been descended from an Arabian tribe, who immigrated thousands of years ago from the Southern Arabian peninsula. Salibi maintains "It is very possible that the Maronites, as a community of Arabian origin, were among the last Arabian Christian tribes to arrive in Syria before Islam".[14]

Lebanon holds the largest number of Christians in the Arab world in proportion to its total population and overall, falling just behind Egypt. It is known that they made up between 65%-85% of Lebanon's population before the Lebanese Civil War, if not more, and their percentage today still remains at around 48%-50% today (if excluding all refugee's and immigrant's of the Muslim faith); if counting the estimated 10-15 million strong diaspora, they form more than the majority. Lebanese Christians belong mostly to the Maronite Catholic Church and Greek Orthodox, with sizable minorities of the Melkite Greek Catholics. There is, however, uncertainty about the exact numbers because no official census has been made in Lebanon since 1932. Lebanese Christians are the only Christians in the Middle East with a sizeable political role in the country where the Lebanese president, half of the cabinet, and half of the parliament are of the various Lebanese Christian rites.

Jordan

In Jordan, Christians constitute about 7% of the population (about 400,000 people), though the percentage dropped sharply from 18% in the early beginning of the 20th century. This drop is largely due to influx of Muslim Arabs from Hijaz after the First World War, the low birth rates in comparison with Muslims and the large numbers of Palestinians (85-90% Muslim) who fled to Jordan after 1948. Nearly 70-75% of Jordanian Christians belong to the Eastern Orthodox Church, while the rest adhere to Catholicism with a small minority adhering to Protestantism. Christians are well integrated in the Jordanian society and have a high level of freedom. Nearly all Christians belong to the middle or upper classes. Moreover, Christians enjoy more economic and social opportunity in the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan than elsewhere in Southwest Asia. Although they constitute less than ten per cent of the total population, they have disproportionately large representation in the Jordanian parliament (10% of the Parliament) and hold important government portfolios, ambassadorial appointments abroad, and positions of high military rank.

Jordanian Christians are allowed by the public and private sectors to leave their work to attend Divine Liturgy or Mass on Sundays. All Christian religious ceremonies are publicly celebrated in Jordan. Christians have established good relations with the royal family and the various Jordanian government officials and they have their own ecclesiastic courts for matters of personal status.

Palestinian Territories

About 75,500 Palestinian Christians live in the Palestinian territories of the West Bank and Gaza Strip,[13] with about 122,000 living in Israel (as Arab citizens of Israel), and an estimated 400,000 Palestinian Christians living in the Palestinian diaspora. Both the founder of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, George Habash, and the founder if its offshoot, the DFLP, Nayif Hawatmeh, were Christians, as is prominent Palestinian activist and former Palestinian Authority minister Hanan Ashrawi.

Egypt

Egyptian Christians, known as Copts, are mainly members of the Coptic Orthodox Church. Although Copts in Egypt speak Masri, they are not Arabs, and do not consider themselves to be ethnically Arabs (see Coptic identity). The Copts constitute the largest number of Christians in the Middle East, numbering between 15,000,000 and 18,000,000.[15][16] The liturgical language of the Copts, the Coptic language, is the direct descendant of the Ancient Egyptian language. Copts outside of Egypt do not speak Arabic, and rather speak the languages of their respective countries. However, Coptic remains the liturgical language in all Coptic churches inside and outside of Egypt.

Egyptian Christians reject the "Arab' label, and continuously assert their Egyptian roots that date thousands of years prior to the Arab invasion of Egypt. This sentiment can be summarized in the words of Bishop Thomas, the Coptic Orthodox bishop of Cusae and Meir, during a lecture at the Hudson Institute:

If you come to a Coptic person and tell him that he’s an Arab, that’s offensive. We are not Arabs, we are Egyptians[17]

North Africa

There are tiny communities of Roman Catholics in Tunisia, Algeria, Libya, and Morocco because of French rule for Algeria, Tunisia, and Morocco, Spanish rule for Morocco, and Italian rule for Libya. Most of the members in North Africa, however, are foreign missionaries or immigrant workers and people of French, Spanish, and Italian colonial descent, while only a minority among them are converted Arabs (or their descendants) or descendants of converted Berbers, often brought to Christian (Catholic) belief during the modern era or under French colonialism. Charles de Foucauld was renowned for his missions in North Africa among Muslims, including African Arabs.

Diaspora

Many millions of Arab Christians also live in a diaspora elsewhere in the world. These include such countries as Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Mexico, the United States and Venezuela among them. The majority of self-identifying Arab Americans are Eastern Rite Catholic or Orthodox, according to the Arab American Institute. On the other hand, most American Muslims are black or of South Asian (Indian or Pakistani) origin. There are also many Arab Christians in Europe, especially in the United Kingdom, France (due to its historical connections with Lebanon and North Africa), and Spain (due to its historical connections with northern Morocco), and to a lesser extent, Ireland, Germany, Italy, Greece and the Netherlands.

Religion

The Arabic-speaking Christians belong to different churches: Melkite Greek Catholic Church, Greek Orthodox Church, Maronite Catholic Church, Chaldean Catholic Church, Syriac Catholic Church, Syriac Orthodox Church, Nestorian Church, Roman Catholic Church and Protestant Churches.

Doctrine

Like Arab Muslims and Arab Jews, Arab Christians refer to God as Allah, since this is the word in Arabic for "God".[18][19] The use of the term Allah in Arab Christian churches predates Islam by several centuries.[18] In more recent times (especially since the mid-19th century), some Arabs from the Levant region have been converted from these native, traditional churches to more recent Protestant ones, most notably Baptist and Methodist churches[citation needed]. This is mostly due to an influx of Western, predominantly American Evangelical, missionaries.

Identity: What is an Arab Christian?

Arab Christians are Christians in certain countries in the Arab world. Arab Christians are indigenous to the Middle East, with a presence there predating the 7th century Islamic expansion in Western Asia. Many Arab Muslims today were originally Arab Christians who converted to Islam for various reasons. Most of the Levantine Christians are ethnic Arabic, descendants from Arabian tribes such as the Kahlani Qahtani tribes of ancient Yemen (i.e. Ghassanids, Lakhmids, Banu Judham and Hamadan) and maybe descendants of the Canaanites which also came from the Arabian Peninsula.

Question of Identity

In Lebanon many Maronites and other Lebanese Christians sects, feel a stronger link and cultural identification with Phoenicians and show pride in the belief that their ancestry is linked to the Phoenicians.[12][20][21][22][23][24] According to Al Jazeera, in the creation of the state of Lebanon (out of Syria) by the French a myth was created in which the inhabitants were promoted as being distinct, unique, or even that they were of another ancestry or ethnicity compared to their neighbors (i.e. Phoenician instead of Arab).[25] According to the CIA World Factbook, many Christian Lebanese do not identify as Arab but believe they are descendants of the ancient Caananites and prefer to identify as Phoenicians.[20]

Phoenicianism never developed into an integrated ideology led by key thinkers, but there are a few who stood out more than others: Charles Corm, Michel Chiha, and Said Aql in their promotion of Phoenicianism.[26]

In post civil-war Lebanon since the Taif agreement, politically Phoenicianism as an alternate to Arabism is restricted to small group.[27] At the March 1936 Congress of the Coast and Four Districts, the Muslim leadership at this conference made the declaration that Lebanon was an Arab country, indistinguishable from its Arab neighbors. In the April 1936 Beirut municipal elections, Christian and Muslim Politicians were divided along Phoenician and Arab lines in concern of whether the Lebanese coast should be claimed by Syria or given to Lebanon. Increasing the already mounting tensions between the two communities.[28] Phoeniciansm is deeply disputed by many Arabist scholars who have on occasion tried to convince them these claims are false and to embrace and accept the Arab identity instead.[29] This conflict of ideas of an identity is believed to be one of the main pivotal disputes between the Muslim and Christian populations of Lebanon and what mainly divides the country from national unity.[30][31] It's generalized that Muslims focus more on the Arab identity of Lebanese history and culture whereas Christians focus on the pre-arabized & non-Arab spectrum of the Lebanese identity and rather refrain from the Arab specification.[24][30][31]

Lebanese Christians are known to be specifically linked to the root of Lebanese Nationalism and opposition to Pan-Arabism in Lebanon, this being the case during 1958 Lebanon crisis. When Muslim Arab nationalists backed by Gamel Abdel Nasser tried to overthrow the then Christian dominated government in power, due to the displeasure of the government's pro-western policies and their lack of commitment and duty to so called "Arab brotherhood" by preferring keep Lebanon away from the Arab League and the political confrontations of the Middle East. A more hard-nosed nationalism among some Christian leaders, who saw Lebanese nationalism more in terms of its confessional roots and failed to be carried away by Chiha's vision, clung to a more security-minded view of Lebanon. They regarded the national project as mainly a program for the security of Christians and a bulwark against threats from Muslims and their hinterland.[32]

Also this is seen with its movement members and leaders. With Etienne Saqr, Said Akl, Charles Malik, Camille Chamoun and Bachir Gemayel being notable names. Some being noted go as far as having Anti-Arab views, in his book the Israeli writer Mordechai Nisan who at times met with some of them during the war quoted Said Akl a famous Lebanese poet and philosopher as saying;

"I would cut off my right hand just not to be an Arab."[33]

Akl believes in emphasis of the Phoenician legacy of the Lebanese people and promoted the use of the Lebanese dialect written in a modified Latin alphabet, that had been influenced by the Phoenician alphabet, rather than the Arabic one.[29]

With the exiled Leader and founder of the right-wing yet secular Guardians of the Cedars Etienne Saqr also the father of singers Karol Sakr and Pascale Sakr that took no sectarian stance and even had Muslim members who joined in their radical stance against Arabism and Palestinian forces in Lebanon.[34] Saqr summarized his party's view on the Arab Identity on their official ideological manifesto by stating;

Lebanon will remain, as always, Lebanese without any labels. The French passed through it yet it remained Lebanese. The Ottomans ruled it and it remained Lebanese. The stinky winds of Arabism blows through it, but the wind will wither away and Lebanon will remain Lebanese. I do not know what will become of those wretched people who claim that Lebanon is Arabic when Arabism disappears from the map of the Middle East and a new Middle East would emerge, which is clean from Arabs and Arabism.[35]

On an Al Jazeera special dedicated to the political Christian clans of Lebanon and their struggle for power in the 2009 election entitled, Lebanon: The Family Business the issue of identity was brought up on several occasions, by various politicians including Druze leader Walid Jumblatt, who claimed that all Lebanese lack somewhat of a real identity and the country is yet to discover one everybody could agree on. Sami Gemayel, of the Gemayel clan and son of former president Amin Gemayel, stated he did not considered himself an Arab but instead identified himself as a Syriac, going on to explain that to him and many Lebanese the "acceptance" of Lebanon's "Arab identity" according to the Taef Agreement wasn't something that they "accepted" but instead were forced into signing through pressure.

The official declared "Arab Identity" of Lebanon was created in 1990 based on the Taif Agreement. Without any free discussion or debate among Lebanese people and while Lebanon was under Syrian custody and in the presence of armed Syrian military inside then Lebanese parliament when voting on constitutional amendments were taking place.[36]

In a speech in 2009 to a crowd of Christian Kataeb supporters which he stated to him he felt there was importance in Christians finding an identity and went on to state what he finds identification with as a Lebanese Christian concluding with a purposely exclusion of Arab in the segment. The speech met with an applause afterward from the audience;[36]

What we are missing today, is an important element of our life and our honor. Which is our identity. I will tell you today, that I as a Lebanese citizen, my Identity is Maronite, Syriac, Christian, and Lebanese(مارونية سريانية مسيحية لبنانية : Maroniya, Syryaniya, Masïhiya, Lubnaniya).[36]

Etienne Sakr (of the Guardians of the Cedars Lebanese party) in an interview responded "We are not Arabs" in response to an interview question about the Guardians of the Cedars' ideology of Lebanon being Lebanese. He continues by talking about describing Lebanon as being not Arab as a crime in present day Lebanon, the Lebanese civil war, about Arabism as being first step towards Islamism, that "the Arabs want to annex Lebanon" and in order to do this "to push the Christians out (out of Lebanon)" and it being "the plan since 1975", among other issues.[37]

Another infamous Lebanese politician who rejected Arabism was the politically secular Greek Orthodox Antun Saadeh founder of the SSNP, who was executed for advocating the abolition of the Lebanese state, by the Kataeb led government in the 1940s for allegedly trying to orchestrate a failed coup attempt against the government in power and declare a regime change. he rejected Arab Nationalism (the idea that the speakers of the Arabic language form a single, unified nation), and argued instead for the creation of the state of United Syrian Nation or Natural Syria encompassing the Fertile Crescent. Saadeh rejected both language and religion as defining characteristics of a nation, and instead argued that nations develop through the common development of a people inhabiting a specific geographical region. He was thus a strong opponent of both Arab nationalism and Pan-Islamism. He argued that Syria was historically, culturally, and geographically distinct from the rest of the Arab world, which he divided into four parts. He traced Syrian history as a distinct entity back to the Phoenicians, Canaanites, Arameans, Babylonians etc.[38]

Embrace of Arab identity

Many scholars and intellects like Edward Said believed Christians in the Arab world have made significant contributions to the Arab civilization and still do. Some of the top poets at certain times were Arab Christians, and many Arab Christians were physicians, writers, government officials, and people of literature.[39]

Some of the most influential Arab nationalists were Palestinian Christians like George Habash, founder of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, and Syrian intellect Constantin Zureiq.

During a final session of the Lebanese Parliament, a Marada Maronite MP states his identity as an Arab: "I, the Maronite Christian Lebanese Arab, grandson of Patriarch Estefan Doueihy, declare my pride to be a part of our people’s resistance in the South. Can one renounce what guarantees his rights?” [40]

Lebanese historian Kamal Salibi (a Protestant Christian) in his 'A House of Many Mansions' [1988] states (ch. 6): "It is very possible that the Maronites, as a community of Arabian origin, were among the last Arabian Christian tribes to arrive in Syria before Islam. Certainly, since the 14th century, their language has been Arabic. Syriac, which is the Christian literary form of Aramaic, was originally the liturgical language of all the Semitic Christian sects, in Arabia as well as in the Levant and Mesapotamia."[citation needed]

Genetic Studies

A study in the genetic marker of the Phoenicians led by Pierre Zalloua, showed that the Phoenician genetic marker was found in 1 out of 17 males in the region surrounding the Mediterranean and Phoenician trading centers such as the Levant, Tunisia, Morocco, Cyprus, and Malta. The study focused on the male Y-chromosome of a sample of 1,330 males from the Mediterranean. Colin Groves, biological anthropologist of the Australia National University in Canberra says that the study does not suggest that the Phoenicians were restricted to a certain place, but that their DNA still lingers 3,000 years later.[41][42]

In Lebanon, almost 1 in 3 of Lebanese carry the Phoenician gene in their DNA. This Phoenician signature is distributed equally among different groups (both Christians and Muslims) in Lebanon and that the overall genetic makeup of the Lebanese was found to be similar across various backgrounds.[43] The Phoenician gene in this study refers to haplogroup J2 plus the haplotypes PCS1+ to PCS6+, however the study also states that the Phoenicians also likely had other haplogroups.[44]

In addition the study found that the J2 ("old levantine haplogroup") was found in an "unusually high proportion" (about 20-30%) among Levantine people such as the Lebanese, Palestinians, and Syrians. The ancestor haplogroup J is common to about 50% of the Arabic-speaking people of the Southwest Asian portion of the Middle East. A Lebanese Christian who was tested as having the J2 haplogroup stated that "It carries no big meaning," and added he views himself as "Lebanese, Arab and Christian -- in that order."[45]

Another Lebanese citizen tested stated he would be "very proud" to discover he had Phoenician roots."I will be more than happy to have Phoenician roots," said Nabil. Phoenicians started the civilization, they are the ones who invented the alphabet [46]), I would be very proud to be a Phoenician," he adds. Dr Pierre Zalloua says the project's discovery is a "truly unifying message".[22]

He explained,"I think it's a truly unifying message, and for me its very gratifying. Lebanon has been hammered by so many divides, and now a piece of heritage has been unravelled in this project which reminds us that maybe we should forget about differences and pay attention to our common heritage," stated Dr Pierre Zalloua.[22]

Prominent Christians from the Arab World

This article possibly contains original research. (July 2010) |

- Fairuz, Lebanese singer.

- Elias Chacour Archbishop, prominent reconciliation and peace activist (Palestinian, Melkite Greek Catholic Christian)

- Michel Aflaq, founder of pan-Arabist Baath party, (Syrian, Greek Orthodox Christian).

- Tariq Aziz, former Iraqi (Baath party) foreign minister and deputy prime minister, (Iraqi Chaldean Catholic Christian).

- Suleiman Mousa, prominent historian and author of T.E. Lawrence: An Arab View, (Jordanian, Catholic Christian).

- George Wassouf, Syrian singer, (Syrian Christian).

- Edward Said, prominent intellectual and writer (Palestinian, Protestant Christian).

- Constantin Zureiq, prominent intellectual and academic, (Syrian, Greek Orthodox Christian).

- George Habash, founder of PFLP, (Palestinian, Greek Orthodox Christian).

- Nayef Hawatmeh, founder of DFLP, (Jordanian, Greek Orthodox Christian).

- Said Khoury, entrepreneur, co-founder of the Consolidated Contractors International Company, (Palestinian, Greek Orthodox Christian).

- Yousef Beidas, prominent Financier, (Palestinian, Greek Orthodox Christian).

- John Sununu, US political leader, (Palestinian-Lebanese, Greek Catholic Christian).

- Hanan Ashrawi, Palestinian scholar and politic activist, (Palestinian, Anglican Christian).

- Steve Bracks (from the Barakat family) Australian State MP, Premier of Victoria, Australia, (Lebanese, Catholic Christian).

- René Angélil, Canadian producer and husband of Céline Dion, (Lebanese-Syrian, Greek Catholic Christian).[47]

- Carlos Menem, president of Argentina from 1988 to 1999, (Syrian, converted to Roman Catholic from Sunni Islam)

- Emile Habibi, writer, (Arab citizens of Israel, Protestant Christian)

- Azmi Bishara, former Knesset member, (Arab citizen of Israel, Greek Orthodox Christian)

- Azmi Nassar, manager of the Palestinian national football team, (Arab citizen of Israel, Greek Orthodox Christian)

- Salim Tuama, Hapoel Tel Aviv middlefielder, (Arab citizen of Israel, Greek Orthodox Christian)

- Simon Shaheen, oud and violin virtuoso and composer, (Arab citizen of Israel, Greek Catholic Christian)

- Salim Jubran, member of the Israeli Supreme Court, Arab citizen of Israel, Maronite (Christian)

- Ralph Nader, US Presidential candidate and consumers' rights activist (son of Lebanese Greek Orthodox Christian immigrants, but declines to comment on personal religion)

- Hani Naser, musician,producer (son of Jordanian Christian Immigrants)

- Shakira, international superstar daughter of Lebanese father from Zahle and Colombian mother of Catalan descent, Greek Orthodox Christian

- Tony Shalhoub, three-time Emmy Award and Golden Globe-winning American television and film actor. (Lebanese, Maronite Christian)

- Marie Keyrouz, chanter of Eastern Church music, Melchite Greek Catholic nun. Founder of L'Ensemble de la Paix (Ensemble of Peace) and Founder-President of L'Instituit International de Chant Sacré (International Institute of Sacred Chant) in Paris.

- Julio César Turbay, president of Colombia from 1978 to 1982, (Lebanese Maronite Christian)

- Carlos Slim Helú, Mexican businessman, (Lebanese Maronite Christian)

- Bruno Bichir and Demián Bichir, Mexican actors, (Lebanese Maronite Christians

- Elias Farah, Syrian philosopher , Greek Orthodox Christian

- Amin al-Rihani, writer and intellectual, (Lebanese, Maronite Christian).

- Afif Safieh, diplomat, (Palestinian, Greek Catholic Christian).

- Bobby Rahal, race car driver, team owner, and businessman, (Lebanese, Maronite Christian

- Doug Flutie, Heisman Trophy winner, NFL quarterback, (Lebanese, Maronite Christian)

- Jacques Nasser, past CEO Ford Motor Company, French-American of Lebanese descent, Greek Orthodox Christian

- Helen Thomas, Whitehouse Journalist, American of Lebanese descent, Greek Orthodox Christian

- George Mitchell, former Senator and Politician, Lebanese, Maronite Christian)

- John Mack, former Chairman & CEO of Morgan Stanley, American of Lebanese descent, Greek Orthodox Christian

- Mosab Hassan Yousef, author of Son of Hamas

See also

- Christianity in the Middle East

- Assyrian/Chaldean/Syriac people

- List of Christian terms in Arabic

- Bible translations (Arabic)

- Ghassanids

- Lakhmids

- Taghlib

- Arab Orthodox

- Sophronius

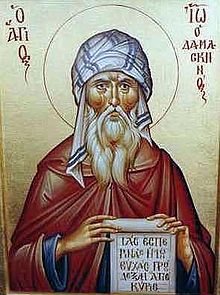

- John of Damascus

- Palestinian Christians

References

- ^ Ethnicity and family therapy By Monica McGoldrick, Joseph Giordano, Nydia Garcia-Preto

- ^ Official population counts put the number of Copts at around 16–18% of the population, while some Coptic voices claim figures as high as 23%. While some scholars defend the soundness of the official population census (cf. E.J.Chitham, The Coptic Community in Egypt. Spatial and Social Change, Durham 1986), most scholars and international observers assume that the Christian share of Egypt's population is higher than stated by the Egyptian government. Most independent estimates fall within range between 10% and 20%"Egyptian Coptic protesters freed". BBC. 22 December 2004. for example the CIA World Factbook "Egypt". The World Factbook. CIA. Retrieved 27 August 2010., Khairi Abaza and Mark Nakhla (25 October 2005). "The Copts and Their Political Implications in Egypt". The Washington Institute. Retrieved 27 August 2010., Encyclopædia Britannica (1985), or Macropædia (15th ed., Chicago). For a projected 83,000,000+ Egyptians in 2009, this assumption yields the above figures.

In 2008, Pope Shenouda III and Bishop Morkos, bishop of Shubra, declared that the number of Copts in Egypt is more than 12 million. In the same year, father Morkos Aziz the prominent priest in Cairo declared that the number of Copts (inside Egypt) exceeds 16 million. "?". United Copts of Great Britain. 29 October 2008. Retrieved 27 August 2010. and "?". العربية.نت. Retrieved 27 August 2010.{{cite web}}: Text "الصفحة الرئيسية" ignored (help) Furthermore, the Washington Institute for Near East Policy Khairi Abaza and Mark Nakhla (25 October 2005). "The Copts and Their Political Implications in Egypt". Retrieved 27 August 2010. Encyclopædia Britannica (1985), and Macropædia (15th ed., Chicago) estimate the percentage of Copts in Egypt to be up to 20% of the Egyptian population. - ^ a b c d Guide: Christians in the Middle East

- ^ "Report: 154,000 Christians live in Israel - Israel News, Ynetnews". Ynet.co.il. 1995-06-20. Retrieved 2010-07-26.

- ^ Christen in der islamischen Welt – Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte (APuZ 26/2008)

- ^ "Daoud Kuttab: Christian Arabs Like the Pope Want Peace with Justice". Huffingtonpost.com. Retrieved 2010-07-26.

- ^ "Arab Christians: An Endangered Species". Jerusalemites.org. 1999-03-18. Retrieved 2010-07-26.

- ^ a b Parry, Ken (1999). The Blackwell Dictionary of Eastern Christianity. Malden, MA.: Blackwell Publishing. p. 37. ISBN 0-631-23203-6.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Shahid Alam, Articulating Group Differences: A Variety of Autocentrisms, Journal of Science and Society, 2003

- ^ Seed, Patricia. Ceremonies of Possession in Europe's Conquest of the New World, 1492-1640, Cambridge University Press, Oct 27, 1995, pp. 79-80.

- ^ Ali, Abdullah Yusuf (1991). The Holy Quran. Medina: King Fahd Holy Qur-an Printing Complex.

- ^ a b "Arab Christians - Who are they?". Arabicbible.com. Retrieved 2010-07-26.

- ^ a b "Arab Christians — National Geographic Magazine". Ngm.nationalgeographic.com. Retrieved 2010-07-26.

- ^ a b Salibi, Kamal., A house of Many Mansions: The History of Lebanon Reconsidered., University of California Press., Berkeley, 1988. p. 89

- ^ Official population counts put the number of Copts at around 16–18% of the population, while some Coptic voices claim figures as high as 23%. While some scholars defend the soundness of the official population census (cf. E.J.Chitham, The Coptic Community in Egypt. Spatial and Social Change, Durham 1986), most scholars and international observers assume that the Christian share of Egypt's population is higher than stated by the Egyptian government. Most independent estimates fall within range between 10% and 20%,

- ^ "Egyptian Coptic protesters freed". BBC. 22 December 2004. for example the CIA World Factbook "Egypt". The World Factbook. CIA. Retrieved 27 August 2010., Khairi Abaza and Mark Nakhla (25 October 2005). "The Copts and Their Political Implications in Egypt". The Washington Institute. Retrieved 27 August 2010., Encyclopædia Britannica (1985), or Macropædia (15th ed., Chicago). For a projected 83,000,000+ Egyptians in 2009, this assumption yields the above figures.

In 2008, Pope Shenouda III and Bishop Morkos, bishop of Shubra, declared that the number of Copts in Egypt is more than 12 million. In the same year, father Morkos Aziz the prominent priest in Cairo declared that the number of Copts (inside Egypt) exceeds 16 million. "?". United Copts of Great Britain. 29 October 2008. Retrieved 27 August 2010. and "?". العربية.نت. Retrieved 27 August 2010.{{cite web}}: Text "الصفحة الرئيسية" ignored (help) Furthermore, the Washington Institute for Near East Policy Khairi Abaza and Mark Nakhla (25 October 2005). "The Copts and Their Political Implications in Egypt". Retrieved 27 August 2010. Encyclopædia Britannica (1985), and Macropædia (15th ed., Chicago) estimate the percentage of Copts in Egypt to be up to 20% of the Egyptian population.}}}} - ^ Bishop Thomas of Cusae and Meir. Egypt’s Coptic Christians: The Experience of the Middle East’s largest Christian community during a time of rising Islamization. July 18, 2008

- ^ a b Timothy George (2002). Is the Father of Jesus the God of Muhammad?: understanding the differences between Christianity and Islam. Zondervan. ISBN 0310247489, 9780310247487.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - ^ Melanie Kaye/Kantrowitz (2007). The colors of Jews: racial politics and radical diasporism (Illustrated, annotated ed.). Indiana University Press. ISBN 0253219272, 9780253219275.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - ^ a b https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/le.html

- ^ "Lebanon news - NOW Lebanon -Phoenicia from the ashes". NOW Lebanon. 2008-12-05. Retrieved 2010-07-26.

- ^ a b c "Divided Lebanon's common genes". BBC News. December 20, 2008. Retrieved April 25, 2010.

- ^ "Lebanon Home Page". LebanonHomePage.com. Retrieved 2010-07-26.

- ^ a b "History lessons stymied in Lebanon". BBC News. April 8, 2009. Retrieved April 25, 2010.

- ^ By Ahmad Ibrahim, Al Jazeera (2009-06-08). "Lebanon 2009 - Lebanese politics: Family affair". Al Jazeera English. Retrieved 2010-07-26.

- ^ Reviving Phoenicia: in search of ... - Google Books. Books.google.co.uk. Retrieved 2010-07-26.

- ^ Reviving Phoenicia: in search of ... - Google Books. Books.google.co.uk. Retrieved 2010-07-26.

- ^ Reviving Phoenicia: in search of ... - Google Books. Books.google.co.uk. Retrieved 2010-07-26.

- ^ a b The Middle East: From Transition to Development By Sami G. Hajjar

- ^ a b "The Identity of Lebanon". Mountlebanon.org. Retrieved 2010-07-26.

- ^ a b "Lebanon: The Arab Village Idiot". American Chronicle. Retrieved 2010-07-26.

- ^ "Notes on the Question of Lebanese Nationalism". Lcps-lebanon.org. Retrieved 2010-07-26.

- ^ (Page 21)

- ^ The conscience of Lebanon: a ... - Google Books. Books.google.com. Retrieved 2010-07-26.

- ^ "The Guardians of the Cedars". Gotc.org. Retrieved 2010-07-26.

- ^ a b c “”. "Lebanon: The family business - 31 May 09 - Part 4". YouTube. Retrieved 2010-07-26.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Interview with Etienne Saqr (Abu Arz)". Global Politician. 2008-01-22. Retrieved 2010-07-26.

- ^ "المكتبة السورية القومية الاجتماعية". Ssnp.Com. Retrieved 2010-07-26.

- ^ http://thechristianarabs.com

- ^ "The vote of confidence debate – final session | Ya Libnan | World News Live from Lebanon". LB: Ya Libnan. 2009-12-11. Retrieved 2010-07-26.

- ^ "Photo: Phoenician Blood Endures 3,000 Years, DNA Study Shows". News.nationalgeographic.com. Retrieved 2010-07-26.

- ^ "DNA legacy of ancient seafarers". BBC News. October 31, 2008. Retrieved April 25, 2010.

- ^ "Divided Lebanon's common genes". BBC News. December 20, 2008. Retrieved April 25, 2010.

- ^ "Haplogroup J2, in general, and haplotypes PCS1+ through PCS6+ therefore represent lineages that might have been spread by the Phoenicians... We do not suggest that the Phoenicians spread only or predominantly J2 and PCS1+ through PCS6+ lineages. They are likely to have spread many lineages from multiple haplogroups" [1]

- ^ "In Lebanon DNA may yet heal rifts | Reuters". Uk.reuters.com. Retrieved 2010-07-26.

- ^ "Phoenicians did not invent the alphabet"

- ^ "À voir à la télévision le samedi 24 mars - Carré d'as". Le Devoir. Retrieved 2010-07-26.